August 2018

Deal or No Deal:

Prospects for Airport Privatization

in the United States

Deal or No Deal:

Prospects for Airport Privatization

in the United States

Authors

Robert Puentes, President and CEO, Eno Center for Transportation

Paul Lewis, Vice President of Policy and Finance, Eno Center for Transportation Extraordinary

Innovation, LA Metro

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Eno’s Aviation Working Group, a standing advisory body on all

aviation issues. The report authors would like to thank So Jung Kim for her contributions to the

editing of this paper. The opinions expressed are those of Eno and do not necessarily reect the

views of our supporters.

About the Eno Center for Transportation

The Eno Center for Transportation is an independent, nonpartisan think tank whose vision is

for an American transportation system that fosters economic vitality and improves the quality of

life for all. The mission of Eno is to cultivate a creative and innovative workforce and to impact

emerging issues for the nation’s multi-modal transportation system.

Cover Photo: Dulles International Airport

CONTACT: Alexander Laska, Communications Officer, Eno Center for Transportation

EMAIL: alaska@enotrans.org

www.enotrans.org | 202-879-4707

Table of Contents

1 Abstract

2 1. Introduction

4 2. Background

9 3. Airport Privatization Experience

10 3.1 Stewart International Airport

12 3.2 San Juan Luis Muñoz Marín Airport, Puerto Rico

14 3.3 Midway International Airport

16 3.4 St. Louis Lambert International Airport

17 3.5 Westchester County Airport

18 3.6 International Examples

20 4. Policy and Practice Implications

23 5. Conclusion

Eno Center for Transportation

1

Deal or No Deal

Abstract

Airport infrastructure investments, such as new runways, modern terminals, and improved

ground access, are a top priority for governments and the traveling public. Robust revenues

from parking, concessions, and landing fees pique the interest of private sector investors

looking for long term, stable returns. Airport privatization proposes to bring the two

together: governments give airport investment and management responsibilities to a

private company that keeps excess returns, and then invests to attract more air service

and passengers. While airports are commonly privatized abroad in places like Europe

and Australia, only one airport is privatized in the United States. This report reviews the

policies that govern airport privatization in the United States, recent history in domestic

case studies, and the implications going forward. In the end, circumstances unique to the

United States greatly limit the usefulness of privatization in solving airport problems.

While privatization may be attractive in some circumstances, policymakers rst need to

clearly understand the problem they are trying to solve, and whether privatization is the

best approach.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

2

1. Introduction

There are more than 3,330 publicly owned airports as part of the national system in the

United States today.

1

These airports move more than 2.5 million passengers each day safely

and effectively, and they contribute $76 billion in total output to the American economy.

2

There is also substantial evidence that airports play a major role in regional economies.

3

But there are also considerable challenges. In 2013, an Eno report showed the runway

and terminal capacity at the nation’s major airports would be unlikely to accommodate

projected growth in passengers over the next 20 years.

4

The head of an airport trade group

recently argued that airports are “at the breaking point” and need $75 billion of capital

investments in the next few years.

5

President Donald Trump and former Vice President

Joseph Biden, who each referred to airports in metropolitan New York as “third-world”,

famously buoyed this perception of major airport infrastructure deciencies.

6

While there

is evidence many airports in the United States clearly benet from competent public

governance, critics disagree. One prominent analysis from 2008 argued that the reason for

excessive ight delays is partly due to the failure of “publicly owned and managed airports”

to improve their efciency.

7

It is no wonder that the call to privatize U.S. commercial airports has recently gotten

louder. Advocates for increased privatization cite it as a means to raise one-time

government revenues, increase airport investment, and remove politics from airport

decision making.

8

Commercial airports also represent an ideal potential private investment

because of their consistent revenue sources from parking, landing, and concession fees.

Unlike most highways and transit systems, airports regularly cover their costs with

revenues from their facilities. Investment in airport infrastructure makes the facility

more attractive to airlines and passengers, increasing revenues for investment return and

meeting the public-sector goal of increasing airport use.

9

1 U.S. Government Accountability Ofce, “Airport Privatization: Limited Interest Despite FAA’s Pilot Program,”

GAO-15-42, 2014.

2 Federal Aviation Administration, “The Economic Impact of Civil Aviation on the U.S. Economy”, U.S. Depart-

ment of Transportation, 2017

3 Richard Florida and others, “Up in the Air: the Role of Airports for Regional Economic Development,” The

Annals of Regional Science, Vol. 54 (1), 2015.

4 Eno Center for Transportation, “Addressing Future Capacity Needs in the U.S. Aviation System,” 2013.

5 Joe Sharkey, “U.S. Airports Are Better, but Not Best,” New York Times, May 6, 2015.

6 “Biden Says NY Airport Like a ‘Third-World Country’,” CNBC Online, February 6, 2014; Sarah Ferris,

“Trump Compares US Airports to ‘Third-World Country’,” The Hill, September 26, 2016.

7 Steven Morrison, Clifford Winston, “Delayed! U.S. Aviation Infrastructure Policy at a Crossroads,” in Aviation

Infrastructure Performance: A Study in Comparative Political Economy, C. Winston and G. de Rus, eds.,

Brookings Institution, 2008.

8 Robert Poole, “Annual Privatization Report: Air Transportation,” Reason Foundation, 2018.

9 Sheri Ernico and others, “Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization,” Transportation Research Board,

Airport Cooperative Research Program Report 66, 2012.

Eno Center for Transportation

3

Deal or No Deal

In addition, examples abroad show that airports often opt for mixed or full privatization.

One comprehensive survey found that 41 percent of all European airports have some share

of private ownership, compared with only one airport in the United States.

10

However,

passengers give these airports mixed reviews. According to a “the best in the world”

passenger survey, 32 European airports rank in the top 100. Of those, 20 are public or run

by a nonprot, and 11 are private or mostly private. Meanwhile, all 15 U.S. top-ranked

airports are fully public, but only ve rank in the top 50 globally.

11

While privatization

is still more prevalent abroad, the U.S. context is starkly different because tax-exempt

municipal debt can provide a cheaper alternative to private investment.

In other words, despite its worldwide attention, calls for airport privatization in the United

States and the problems stakeholders are trying to solve are unproductively disconnected.

Therefore, it is important to investigate the complexities of U.S. airport governance and

lessons learned from past privatization experiences. This discussion is especially timely

because of several major policy moves occurring today.

Renewed discussions about the role of the private sector in infrastructure broadly and

transportation specically are not entirely related to airport privatization. Cities, states,

and metropolitan areas across the country are exploring new kinds of partnerships with

private rms on everything from urban mobility, highways, to public transit.

12

Most

notably, the Trump administration recently proposed spinning off the nation’s air trafc

control system from the federal government into a nonprot entity separate from, but

overseen by, the national government.

13

But the circumstances that qualify privatization

of air trafc control or a highway as sound policy are not necessarily universal to other

projects or types of infrastructure. These disparate debates complicate the discussions

about airport privatization.

Related is the push for airport privatization coming from Washington. In its infrastructure

proposal, the administration recommended privatizing several government assets including

two airports in metropolitan Washington owned by the federal government.

14

It also called

for the expansion of a federal pilot program on private ownership of airports. The proposal

was recently taken up by Congress and incorporated by the House of Representatives into a

proposal to reauthorize the Federal Aviation Administration.

10 Olivier Jankovec, “The Ownership of Europe’s Airports,” Airports Council International – Europe, 2016.

11 Skytrax, “World’s Top 100 Airports 2017,” World Airport Awards, 2017. For one other airport—Düsseldorf—

the public and private shares are equally mixed.

12 Patrick Sabol and Robert Puentes, “Private Capital, Public Good: Drivers of Successful Infrastructure Pub-

lic-Private Partnerships,” Brookings Institution, 2014.

13 Proposals to spin-off air trafc control date back to the Clinton Administration. See: Eno Center for Trans-

portation, “Time for Reform: Delivering Modern Air Trafc Control,” 2017.

14 Michael Laris, “Trump Administration Wants to Sell National and Dulles Airports, Other Assets Across

U.S.,” Washington Post, February 13, 2018.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

4

The purpose of this report is to analyze the outcomes of airport privatization in the United

States, describe different models for the role of private rms in airports, examine the

federal pilot program and its participating airports, and discuss key implications for both

the public and private sectors.

15

We nd that while airport privatization may be attractive

in some circumstances, policymakers rst need to clearly understand the problem they are

trying to solve and determine whether privatization is the best approach.

2. Background

For the purposes of this paper, “privatization” refers to the long-term lease or sale of an

airport. But private sector involvement at U.S. airports is not binary in that they are wholly

owned and operated either by a government or public authority or a for-prot company. All

publicly owned airports in the United States have a high degree of private involvement for

most airport operations. One expert states that, in some respects, U.S. airports are the most

privatized in the world since almost all of the “nance, planning, and operating activities”

are outsourced to private, for-prot companies.

16

Although not directly employed by the airport, federal public sector employees work at

airports as security ofcers or Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) air trafc controllers,

as required by federal law.

17

But the remaining workers almost always employed by the

airlines or private contractors. Airports’ use of private sector workforce is long established:

a 1996 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Ofce (GAO) estimated 90 percent of

the workforce at major U.S. airports is employed by the private sector.

18

A 2017 Congressional Research Service report highlights four broad types of private sector

involvement in airports (Table 1). Most of the potential benets of privatization, such as

market efciencies, outside expertise, and long-term cost control, are already captured

through developer nancing and typical service and management contracts. U.S. airports

are already commercial enterprises run by professional managers. Even proponents of

privatization admit that “U.S. airports are quite competently run,” and there is no crisis

of competence in management.

19

Despite general admonition of their third-world status,

passenger satisfaction with North American airports overall is at an all-time high,

according to a recent survey.

20

15 This analysis focuses on commercial airports, rather than general aviation since the federal pilot program is

directed primarily at the former.

16 Amedeo Odoni, “The International Institutional and Regulatory Environment,” in The Global Airline Indus-

try, Peter Belobaba, Amedeo Odoni, and Cynthia Barnhart, eds., Wiley, 2009.

17 Morrison and Winston, 2010.

18 United States General Accountability Ofce, “Airport Privatization: Issues Related to the Sale or Lease of US

Commercial Airports,” GAO-RCED-97-3, 1996.

19 Greg Principato, “This is Why No Airport Privatization in the U.S.” NewAirport Insider, December 15, 2017.

20 J.D. Power, “North American Airports Effectively Navigating Construction, Capacity Challenges, J.D. Power

Eno Center for Transportation

5

Deal or No Deal

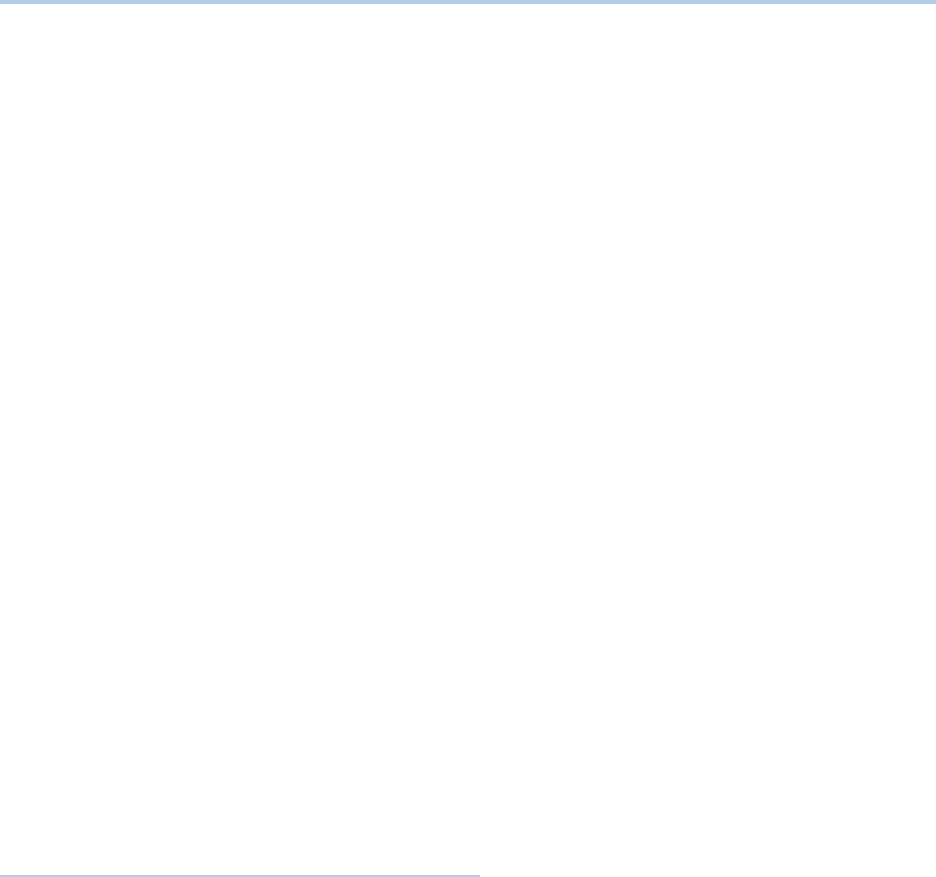

Table 1: Types of Private Sector Involvement at U.S. Airports

Type of

private

involvement

Service contracts

Management

contracts

Developer

nancing for

capital investment

Long-term lease

or sale

Example:

Janitorial services

Landscaping

Shuttle bus

operations

Concessions

Parking

facilities

Airport-wide

management

Terminal

development

Fuel systems

Cargo

Solar

Airport

privatization

pilot program

Specic case:

Pittsburgh

Boston

Washington, D.C.

Albany

Indianapolis

BOSFuel

La Guardia

Austin rental car

San Juan

Stewart

Source: Tang, 2017.

In addition to handing off airport operation and management, privatization may also be

considered an attractive way to inject new funds into capital assets like airport terminals

and runways. It can also provide a one-time payment to local governments for the

privilege of a long-term lease. The United States has used private capital to fund other

transportation investments such as highway, transit, and seaport expansions, with the

private sector selling bonds to cover some of the upfront costs, repaid by future toll, fee,

and/or tax revenues.

21

Backed by future airport revenues, airports that need new terminals

and runways could use the same private debt to improve and expand. However, several

barriers limit the usefulness of private capital for public airports.

First of all, publicly owned airports can take advantage of tax-exempt public bonds,

which the federal government offers to states, localities, and agencies like transportation

departments and school districts. There is no federal cap on the amount of tax-exempt

municipal debt governments can issue, and municipalities have broad discretion to

sell them to individuals and institutions like banks. The interest received by holders of

municipal bonds is exempt from federal income taxation, a perk that frees the issuing

government to pay a lower premium and remain competitive. This makes the cost of

borrowing for infrastructure improvements extremely cost effective for the public sector.

They are generally backed by either general tax revenues or specically the revenue

generated on the airport property (e.g., airline fees, concessions, parking.)

22

States and localities are also allowed to issue debt for projects that have some private

benet often with the same tax privilege as municipal bonds. These private activity bonds

(PABs) issued for airports are not subject to any kind of volume cap and are widely used.

A recent report from the Congressional Research Service found that more than $7.8 billion

Finds,” September 21, 2017.

21 Eno Center for Transportation, “Partnership Financing: Improving Transportation Infrastructure Through

Public Private Partnerships,” 2014.

22 Cindy Nichol, “Innovative Finance and Alternative Sources of Revenue for Airports,” Transportation Re-

search Board, Airport Cooperative Research Program Synthesis 1, 2007.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

6

in PABs was issued for airports in 2015.

23

PABs can only be issued by governmental

authorities and not by the private sector, which must issue debt at taxable market rates

that tend to be much more expensive than public bonding, although in some cases airports

issues PABs in public-private partnerships (P3) for construction or on behalf of airlines for

hangers.

Airports also have robust, diverse revenue streams and usually do not lack the funding or

bonding authority to make improvements to their infrastructure and operations (see Table

2). These sources mean that, on average, airports in North America have net revenues that

exceed their capital and operating expenses.

24

This is naturally attractive to an investor and

also a primary reason why airports are targeted for privatization.

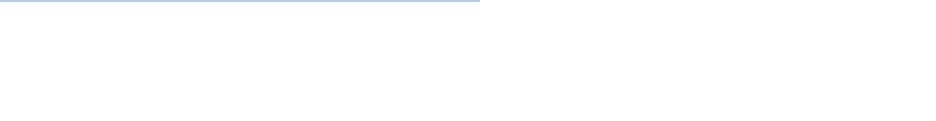

Table 2: Large Hub Airport Revenues, by Source

Revenue Source Percentage

Landing and Arrival Fees 38%

Cargo and Hangar Rentals 2%

Facility Leases 2%

Terminal Concessions 8%

Rental Cars 6%

Parking 14%

Interest 1%

Federal Grants 3%

Passenger Facility Charge 13%

Other 12%

Source: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) CATS Database, 2016, average over all large hub

airports as dened by FAA.

However, federal law requires all revenues generated by a public airport to be reinvested

back into airport assets.

25

This includes local taxes on aviation fuel, landing fees, parking

revenue, and in-airport concessions. While this does not apply to service, management,

and construction contracts, it makes long-term leases unappealing since a private partner

cannot use that revenue to generate nancial return for its investors.

Finally, a private partner might have to repay federal grants that previously went to the

improvement of an airport, such as from the Airport Improvement Program (AIP), subject

to the discretion of U.S Department of Transportation. They might also have to return

23 Includes both new and reissues. Steven Maguire and Joseph S. Hughes, “Private Activity Bonds: An Intro-

duction,” Congressional Research Service, 2018.

24 Airports Council International, “State of Airport Economics,” Infrastructure Management Programme,

ICAO, 2015.

25 49 U.S. Code § 47107(b)

Eno Center for Transportation

7

Deal or No Deal

any federal property or equipment.

26

These grants have long-term restrictions on use, and

repayment might be costly or burdensome for a hypothetical private entity managing the

airport. Since there is very limited experience with airport privatization and the AIP terms

vary by airport, it is unclear exactly how specic airports would be affected. Nevertheless,

this requirement is clearly not conducive to privatization.

In order to address these regulatory hurdles, Congress created the Airport Privatization

Pilot Program (APPP) in 1996 as a way to provide test exemptions for these restrictions.

27

Under the APPP, the Secretary of Transportation can approve the privatization and waive

the requirements for repayment and/or for the restriction of the use of airport revenues

outside of the property. Initially there were ve slots in the APPP program, which was

increased to 10 in 2012. Only general aviation airports can be actually “sold” under the

program; commercial airports can only be leased out.

But, even though the program was created intentionally to foment privatization, the path

is not easy. For one, to be granted an exemption to the use of revenues, the sponsor of the

transaction needs the concurrent approval of 65 percent of all airlines using the airport.

28

The same super-majority of airlines must also approve all fee increases charged to airlines

at a higher rate than ination, which they are not keen to do. In addition, the FAA is also

allowed to audit the operations and nances of the privatized airport in order to determine

if it is collecting reasonable rents, landing fees, and other charges (though the program does

not dene “reasonable”).

Therefore, while the APPP does allow for privatization, the current rules make it very

difcult to approve and not particularly attractive to private sector bidders. In fact, in more

than two decades since the inception of the program, only two airports have actually been

privatized: Stewart International Airport in New Windsor, New York; and Luis Muñoz

Marin airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico. (These cases are discussed later in this report.)

As part of its major infrastructure package, the Trump administration proposed expanding

the existing APPP.

29

The current cap on the number and restriction on the type of airports

that can participate would be removed, and the double-supermajority requirement for

airline approval of an airport’s entry into the APPP would be changed to a simple majority.

Airports would be allowed to offer incentive payments for early completion of AIP projects,

and oversight of AIP grants would be loosened from advance application approval to post-

26 Bart Elias and Rachel Y. Tang, “Reauthorization of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the 115th

Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 2017.

27 Sheri Ernico and others, “Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization,” Transportation Research

Board, Airport Cooperative Research Program Report 66, 2012.

28 The actual provision is 65 percent of all airlines using the airport and airlines representing 65 percent of

the annual landed weight. See: Federal Aviation Administration, “Fact Sheet – Airport Privatization Pilot

Program,” U.S. Department of Transportation, December 20, 2017.

29 Jeff Davis, “Trump Infrastructure Plan Outline,” Eno Transportation Weekly, January 8, 2018.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

8

expenditure audits. Various other provisions would further encourage the use of federal

credit assistance like PABs by making them eligible for browneld projects, rather than

only greeneld projects as is the case today. This change would make long-term P3 leases of

existing airports less costly to nance, perhaps stimulating more private sector interest.

The administration’s plan also calls for divestiture of Dulles International and Reagan

National Airports.

30

While this proposal seems consistent with the focus on airport

privatization, it is actually an anomaly as these are the only commercial airports

authorized and established by Congress and owned by the federal government. FAA began

owning and operating Reagan National in 1959 and then Dulles in 1962. In 1985, both

airports were transferred to a newly created regional authority via a long-term lease.

31

The

authority has been running both airports ever since, but they are still owned by the federal

government, and their operations are still a strong interest of Congress.

32

Like much of the administration’s infrastructure plan, the proposal to rid the federal

government of the Washington area airports was met with resistance.

33

However, several

changes to the APPP were incorporated into the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 that

passed the U.S. House by a wide margin in April 2018.

34

The bill makes several signicant

changes to the APPP including removing the word “privatization” and renaming it

the Airport Investment Partnership Program. It also removes the participant cap (at

10 airports) and makes no distinction between how many or what type of airport can

participate. Importantly, it streamlines the process for obtaining the exemptions for the

restrictions on how revenue is used and the requirement that federal grants are repaid.

It also allows multiple airports to apply under one sponsor, such as the Metropolitan

Washington Airports Authority which overseas Reagan National and Dulles Airports. As of

this publication, the bill awaits action by the U.S. Senate.

30 American Journal of Transportation, “Fitch: U.S. Infrastructure Plan Could Provide Boost for U.S. Airports,”

February 21, 2018.

31 Susan L. Kurland, “DOT’s Role Regarding Operations at the Two Metropolitan Washington Airports Author-

ity Airports, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and Washington Dulles International Airport,”

Statement before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Subcommittee on Avia-

tion Operations, Safety, and Security, September 16, 2010.

32 The Reason Foundation’s Robert Poole also points to the fact that Metropolitan Washington Airport Au-

thority has $4.5 billion in outstanding bonds, making privatizing these airports unlikely. See Robert Poole,

“White House Infrastructure Plan Boosts Airport Privatization,” Airport Policy News #122, Reason Founda-

tion, March 1, 2018.

33 Ben Mutzabaugh, “D.C. Airports Sold to the Highest Bidder? Not So Fast ...” USA Today, February 13, 2018.

34 The nal vote was 393-13. U.S. House of Representatives, “H.R. 4 – FAA Reauthorization Act,” 115th Con-

gress, 2018.

Eno Center for Transportation

9

Deal or No Deal

3. Airport Privatization Experience

While only a very few number of airports have applied to participate in the APPP,

their examples are illustrative and important in order to discern the narrow set of

conditions in which privatization is practical. Overall, the experience in the United

States is decidedly mixed. The ve American case study airports in this section, and

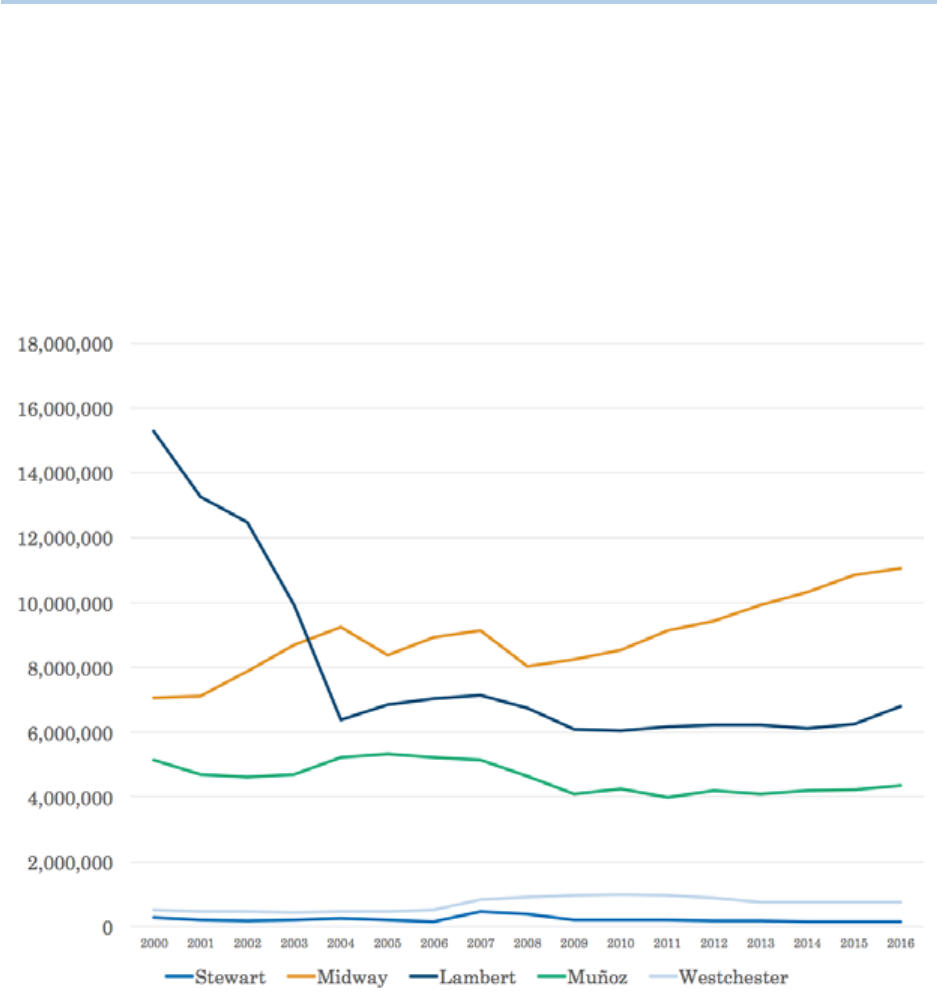

their corresponding trafc levels, can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Enplanements at Select U.S. Airports

Source: Federal Aviation Administration, Passenger Boarding (Enplanement) and All-Cargo Data for

U.S. Airports dataset. “Enplanements” refers to passenger boardings at airports that receive scheduled

passenger service.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

10

3.1 Stewart International Airport

The rst airport in the United States to be privatized under the APPP was Stewart

International, an airport located 67 miles north of New York City in Orange County.

35

The

skies around metropolitan New York are famously congested and among the busiest in the

world. Using Stewart to alleviate some passenger pressures from the other major airports

was a public policy ambition for the region since at least the 1950s, but the airport needed

upgrades.

36

According to the GAO, the state sought the sale or lease of Stewart to a private

partner in order to increase service, provide resources to invest in the airport, and boost tax

revenue.

37

Another analysis cited then-Gov. George Pataki’s interest in being a leader in

“privatization alternatives” for infrastructure assets and operations.

38

In 1997, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) received ve

responses to its request for proposals from potential operators of the airport. The next

year, the National Express Group (NEG), a major British rail, bus, and coach transit

company, inked a deal with the state, which was sent along to the FAA for nal review

and approval.

39

NEG was awarded the right to operate the airport for 99 years and paid

the state $35 million, which was invested back in to airport operations. The state would

also receive 5 percent of gross income each year beginning in the tenth year of the lease.

New York did not request an exemption on the use of revenues because they knew from

preliminary discussions with the air carriers they would be unable to receive their required

approval. However, the state did request and receive an exemption from the requirement to

repay federal grants and return property.

40

In the application, NEG afrmed that it had “extensive experience in owning, managing

and operating airports” due to its acquisition of East Midlands and Bournemouth

International Airports in the United Kingdom earlier in the decade. NEG also highlighted

its management of Philippines’ Subic Bay International Airport in 1997 “during which time

it became familiar with FAA procedures.”

41

Per the parameters of the APPP, New York

retained the right to inspect the airport operations and the nancial records of NEG at any

time. The lease stipulated that the transaction would have no impact on the fee structure

for air carriers whose rates and charges would be unchanged, unless approved by the

35 The airport was recently renamed New York Stewart International Airport in 2018 to enhance its appeal to

travelers in the region. Jack Howland, “Stewart Airport Renamed New York Stewart International Airport,”

Poughkeepsie Journal, February 21, 2018.

36 Joe Mysak, “PATH’s [sic] New Stewart Lease Calls Airport Privatization into Doubt,” Pittsburgh Tribune

Review, February 5, 2007.

37 U.S. GAO, 1996.

38 Sheri Ernico and others, “Considering and Evaluating Airport Privatization,” Transportation Research

Board, Airport Cooperative Research Program Report 66, 2012.

39 The operator was technically SWF Airport Acquisition, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of National Express

Corporation, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of NEG.

40 National Express and New York State Department of Transportation, “Stewart International Airport, Final

Application Under the Airport Privatization Pilot Program,” January 8, 1999.

41 Ibid.

Eno Center for Transportation

11

Deal or No Deal

airlines.

Unfortunately, the deal struggled from the outset, and by 2006, NEG sought to sell the

lease to run the airport. The next year, Stewart returned to public hands when the Port

Authority of New York and New Jersey purchased the remaining 91 years of the lease from

NYSDOT in 2007. The Port Authority continues to run Stewart along with other major

airports in the region.

There are several likely reasons why the deal with NEG collapsed. One is related to the

severe downturn in aviation passengers that followed the terrorist attacks of September

11. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), from 2000 to 2001

national air passenger trafc fell 5.9 percent and another 1.4 percent the next year.

42

Federal data shows that enplanements at Stewart dropped by 27.8 percent and another

11 percent during the same timeframe.

43

For a private business model built on increasing

revenue from non-aeronautical sources, such as new retail and restaurants in the terminal

and car rental and parking concessions, trafc drops are difcult for any private partner to

handle.

Yet in this case, it is clear that NEG was already reconsidering its strategy to expand from

mostly public transit operations into aviation. Just one year after the state approved it,

NEG asked NYSDOT to terminate the lease, which the state declined to do.

44

That was

right around the time NEG had sold off its three U.K. airport operation interests in order

to concentrate on its bus and rail business.

45

It is clear that NEG was concerned about its

ability to generate a satisfactory long-term nancial return and, according to the GAO, “was

not interested in investing in the airport.”

46

They also may not have been able to invest as

the company nearly went bankrupt during this time when it overbid for a U.K. rail line.

47

Stewart represents a clear policy failure to successfully privatize a U.S. airport through

the APPP process. It may not, however, have been a business failure for NEG. Two

different reports cite the “signicant return on investment” for the rm despite its desire

to terminate the lease.

48

The case of Stewart is useful as an example of the challenges

that can arise when a private operator experiences signicant internal transitions and

the unpredictable role that external events can have on the revenues and operations of an

airport.

49

42 International Air Transport Association, “The Impact of September 11 2001 on Aviation,” 2011.

43 Eno analysis of FAA data “Passenger Boarding (Enplanement) and All-Cargo Data for U.S. Airports.”

44 Ernico and others, 2012.

45 BBC News, “Manchester Airport Spreads its Wings,” February 19, 2001.

46 U.S. GAO, 2014.

47 Richard Bowker, “Rail Crisis: London-to-Edinburgh Route to be Nationalised,” The Guardian, July 1, 2009.

48 Ernico and others, 2012; and Rachel Y. Tang, “Airport Privatization: Issues and Options for Congress,” Con-

gressional Research Service, August 16, 2017.

49 Daniel Reimer, “Airport Privatisation in the USA: Recent Legal Developments and Future Outlook,” Journal

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

12

3.2 San Juan Luis Muñoz Marín Airport, Puerto Rico

Today, the only privatized airport in the United States is Luis Muñoz Marín (LMM) Airport

in San Juan, Puerto Rico. It is currently owned by the Puerto Rico Ports Authority (PRPA)

and leased to Aerostar Airport Holdings (Aerostar), owned by ASUR and PSP Investments,

under a 40-year lease that began in 2013. LMM is currently the 43

rd

-busiest U.S. airport

and, by far, the busiest in the Caribbean and the largest air cargo hub serving as an

international gateway for the Americas.

Puerto Rico is a national leader in its efforts to work with private partners on a range of

infrastructure projects. Through 2009 legislation, it established one of the earliest entities

to regulate and facilitate such partnerships, the Puerto Rico Public-Private Partnerships

Authority (P3A).

50

These initiatives were done partly out of necessity accompanying a very

challenging and well-known economic situation characterized by extremely high public debt

loads, among other nancial threats. Notably, the Commonwealth had been running out of

cash since its economy began to contract in 2006. As a result, it failed to invest in important

infrastructure assets like its airports.

51

The PRPA, in particular, had serious nancial difculties, and LMM needed signicant

investment and modernization. One comprehensive commentary noted the airport’s

crumbling ceilings and oors, poorly maintained instrument landing system, and many

inconveniences like unpleasant corridors, balky air conditioning, long delays at baggage

claim, and insufcient retail and catering options.

52

Perhaps most perniciously, it criticized

the PRPA’s “unwieldy bureaucracy,” political patronage, and general lack of responsible

management and oversight.

53

LMM was further battered when, in response to security threats, the U.S. Department

of Homeland Security suspended two programs in 2003 that allowed travelers to transit

through U.S. airports without a visa. The suspension of these programs severely impacted

LMM as many ights eventually shifted to airports in the Dominican Republic and resulted

in a loss of landing fees, maintenance, and repairs for many airlines.

54

Passenger trafc

declined precipitously: enplanements fell by 21.6 percent from a high of 5.3 million in

of Airport Management, Vol. 3 (1), 2008.

50 Heather Gillers, “For Sale: Puerto Rico,” Wall Street Journal, June 26, 2017.

51 U.S. Department of Treasury, “Addressing Puerto Rico’s Economic and Fiscal Crisis and Creating a Path to

Recovery: Roadmap for Congressional Action,” 2015.

52 John Tierney, “Making New York’s Airports Great Again,” City-Journal, Winter 2017.

53 The PRPA also managed Puerto Rico’s 10 other airports and maritime port facilities. One study found that

the institutional model of airports managed by authorities with jurisdiction of multiple air and maritime

ports is almost always the least efcient. Tae H. Oum and others, “Ownership Forms Matter for Airport

Efciency: A Stochastic Frontier Investigation of Worldwide Airports,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 64

(2), 2008.

54 “Report by the President’s Task Force on Puerto Rico’s Status,” 2011.

Eno Center for Transportation

13

Deal or No Deal

2005 to 4.1 million in 2009.

55

The loss of revenue contributed to the PRPA’s two-third debt

increase from 2004 to 2008, and its BBB-bond rating was just above junk bond status by

2009.

56

By 2012, it was $60 million in debt to the electric utility, which threatened to cut off

power to the airport.

57

Saddled with over $800 million in debt and unable to tap into the municipal bond market

to make necessary investments in the LMM—even for basic upkeep and maintenance—

Puerto Rico’s P3A studied whether a privatization model would address the airport’s

massive challenges.

58

In 2009, the PRPA applied to participate in the APPP, and in 2012,

it eventually agreed to lease the airport to Aerostar for $615 million upfront, plus a share

of revenues over the life of the lease.

59

The airlines servicing the airport approved the

privatization plan.

The FAA granted all necessary exemptions in order to apply $500 million of the upfront

payment to PRTA debt relief. The remainder went to an early retirement program for

PRPA employees, an air travel promotion program, and upgrades at regional airports.

Aerostar also received an exemption from having to pay back federal grants that supported

LMM and from restrictions from earning compensation from use of the airport. Aerostar

held the rates charged xed for ve years, after which only increased at the rate of ination.

At no additional cost to the airlines, the company was also responsible for improving and

modernizing the airport through an accelerated capital program.

60

Unlike with Stewart in

New York State, the airlines serving LMM generally supported the privatization efforts,

given the poor management and substandard condition of the airport.

Importantly, the privatization plan made explicit efforts not to disenfranchise workers

at the airport. Existing workers were promised that they would keep their jobs, and the

then-U.S. Transportation Secretary guaranteed the plan would be rejected if the collective

bargaining agreement were violated.

61

Aerostar asserted that the $200 million in upgrades

to the terminals created 3,000 jobs by 2014.

62

55 Eno analysis of FAA data “Passenger Boarding (Enplanement) and All-Cargo Data for U.S. Airports.”

56 Federal Aviation Administration, “FAA response to comments regarding the participation of Luis Muñoz

Marin International Airport,” 2013.

57 Mary Williams Walsh, “How Free Electricity Helped Dig $9 Billion Hole in Puerto Rico,” New York Times,

February 1, 2016.

58 Puerto Rico Public-Private Partnerships Authority, “Study of Desirability and Convenience for Luis Muñoz

Marín International Airport,” 2010.

59 In addition to the $615 upfront payment, the PRPA received $2.5 million for lease years one through ve,

5 percent of gross revenues for years six through 30, and 10 percent of revenues in years 31 through 40.

Moody’s Investors Service, “Privatization of Puerto Rico’s Main Airport Gets Final Approval, a Credit Posi-

tive,” March 2, 2013.

60 U.S. Department of Transportation, “Record of Decision for the Participation of Luis Muñoz International

Airport, San Juan, Puerto Rico, in the Airport Privatization Pilot Program,” Federal Aviation Administration

Docket 2009-1144.

61 Bipartisan Policy Center, “Infrastructure Case Study: San Juan Airport,” 2016.

62 Danica Coto, “Puerto Rico Airport to Unveil $200M in Upgrades,” USA Today, July 2, 2014.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

14

The privatization of LMM is widely considered to be a success. In addition to the debt relief

brought to the PRPA, the LMM is now better managed, and the $260 million that Aerostar

expected to spend in capital investments was critically needed. The private sector was well

suited to address the mounting challenges that the airport faced, and there was widespread

support from stakeholders, including the airlines. Some have asserted the ultimate deal for

LMM was undervalued because the transaction was not negotiated in the public’s interest

and undercut workers.

63

Nevertheless, from 2013 through 2016, enplanements increased

by nearly 6 percent, and average passenger fares decreased from $324 in 2013 to $290 in

2017.

64

Aerostar ofcials testied that the privatization would ultimately create $2.6 billion

in total economic value for Puerto Rico.

65

The devastating effects of Hurricane Maria in September 2017 could upset the apparent

progress at LMM. Normal management and airport operations did not resume until the

end of the year. The damage to the airport is currently being evaluated, but trafc is down

nearly 20 percent over last year, which could have signicant ramications for the private

partner to repay debt and maintain high quality operations.

66

3.3 Midway International Airport

Chicago Midway International Airport is one of the busiest airports in the Midwest and

was briey the busiest in the world shortly after it was acquired by the city in 1927. It

is considered the “rst great airport” in the United States.

67

After O’Hare International

Airport was built 16 miles to the north in 1955, Midway’s passenger trafc declined

precipitously, but has since recovered thanks in large part to the arrival of Southwest

Airlines in 1985 and internal renovations. In fact, 2016 was its busiest year ever with over

11 million passenger enplanements.

68

With this recent success it may seem odd that twice in the last decade, Chicago applied

to the APPP program to privatize Midway. Yet, similar to the support of privatization in

63 Cathy Kunkel and Tom Sanzillo, “Privatization Bill Will Not Solve Puerto Rico’s Electricity Crisis,” Institute

for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, 2018.

64 Eno analysis of FAA data “Average Domestic Airline Itinerary Fares.” Figures are for Ination Adjusted

Average Fares. Hurricane Maria made landfall in September 2017 and certainly has had a major impact on

passenger demand and airfares but the gures from 2017 and 2016 are nearly identical. We also recognize

that since 2005 airlines have begun to unbundle charges for things like checked bags, seat selection, meals,

and drinks from the total ticket price. See: Eno Center for Transportation,” Is Air Travel Becoming Pricier

for Travelers?” 2017.

65 U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, “Roundtable Policy Discussion on Opportunities

for Aviation and Public Private Partnerships,” May 20, 2014.

66 PRNewswire, “ASUR 1Q18 Passenger Trafc Increased 9.3% YoY in Mexico and Declined 19.2% in San

Juan, Puerto Rico and 5.2% in Colombia,” CISION PR Newswire, April 23, 2018.

67 Casey Andrew Burton, “An Analysis of the Proposed Privatization of Chicago’s Midway Airport,” Journal of

Air Law and Commerce, Vol. 72, 2007.

68 Eno analysis of FAA data “Passenger Boarding (Enplanement) and All-Cargo Data for U.S. Airports.”

Eno Center for Transportation

15

Deal or No Deal

Puerto Rico, Chicago is experiencing its own scal challenges and is considered the “most

aggressive instigator of infrastructure asset leases” in recent years.

69

The rst Midway application, in 2006, was strongly supported by then-Mayor Richard M.

Daley who had already overseen the privatization of a range of city services and several

highly visible transportation asset leases. Examples include the Chicago Skyway, an 8-mile

toll road leased to a consortium in 2005 for $1.8 billion and four downtown parking garages

leased in 2006 for $583 million. Both deals were for 99 years and are generally considered

to be successful.

70

However, another deal leasing the city’s 36,000 street parking meters to a

private rm for 75 years at $1.2 billion is an infamous disaster due its lack of transparency,

analysis, and prioritization of short-term payments over long-term taxpayer protections.

Chicago’s Inspector General found the city received nearly $1 billion less than it would have

earned without the deal.

71

The impetus for Midway was consistent with the Chicago’s assertive efforts to transact

with the private sector on infrastructure.

72

The city received approval from the airlines

operating at the airport, led by Southwest, to select a private operator to lease the airport,

and in 2008, the City agreed to a 99-year, $2.5 billion lease with the Midway Investment

and Development Corporation (MIDCo) consortium.

73

The deal would have lowered airline-

landing fees for six years, with increases at no greater than the rate of ination. The entire

payment would be made up front with a little more than $1 billion going for infrastructure

improvements in the city, about another billion for pension contributions, and the

remainder unrestricted.

74

It appeared as if Midway would be the rst privatized major U.S.

airport. However, largely due to the nancial strain brought on by the Great Recession the

deal was cancelled in 2009 when MIDCo was unable to secure the nancing and had to pay

a $126 million penalty to the city.

Chicago renewed the effort to lease Midway in 2013 under Mayor Rahm Emanuel claiming

the airport no longer provided “any direct nancial benet to the taxpayers.”

75

By this time

the city had the experience of the rst application as well as the high-prole parking meter

asco and took a more conservative approach to the transaction. The city limited the lease

to no more than 40 years and intended to ask the FAA for the revenue and repayment

exemptions. However, the second application was abandoned later in the year when one of

69 Philip Ashton and others, “Reconstituting the State: City Powers and Exposures in Chicago’s Infrastructure

Leases,” Urban Studies, Vol. 53 (7), 2016.

70 However, the city recently had to pay $62 million to settle a dispute with the private partner in the parking

garage deal over a provision that it would not allow new garages to be built. Dan Mihalopoulos, “City Hall’s

$62 Million Blunder,” Chicago Sun-Times, May 23, 2015.

71 City of Chicago Inspector General, “Analysis of the Lease of the City’s Parking Meters,” 2009.

72 The Economist, “The Big Sell,” September 16, 2010.

73 Tang, 2017.

74 Airports Council International - North America, “Fact Sheet: Chicago Midway Airport – Long-Term Conces-

sion and Lease,” undated. The exact splits are vague because the deal was never completed.

75 City of Chicago, “Chicago Midway International Airport: Request for Qualications,” 2013.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

16

the two bidders withdrew their proposal. The city then suspended its efforts to privatize the

airport and pulled out of the APPP altogether.

The bids to privatize Midway are clear failures, but for different reasons. On the

rst attempt, despite support from the airlines, the city, and other stakeholders, the

concessionaire was unable to raise the capital needed for the upfront payment. The parties

could not execute the deal, with added difculty from the effects of the recession, and the

transaction was not completed. The second deal was also not executed, but mostly because

the city did not structure its parameters in a way that was palatable for investors. The

rigidity is at least partially attributable to Chicago’s focus on protecting taxpayers and

avoiding a deal like the one on its parking meters.

76

3.4 St. Louis Lambert International Airport

In the late 1990s, the St. Louis Lambert International Airport was the nation’s 15

th

-largest,

with more trafc than Seattle-Tacoma, New York LaGuardia, or Charlotte Douglas.

Lambert was once the home of Trans World Airlines (TWA), but after a 2001 merger with

American Airlines, many ights were moved to other larger airports in Chicago and Dallas.

Daily operations by air carriers averaged about 1,000 takeoffs and landings per day in

1997, compared with just 350 in 2016. The airport now suffers from excess capacity.

Despite the trafc decline, Lambert is generally considered to be a very well-run airport,

and enplanements have steadily risen since the 2009 nadir.

77

Nevertheless, in 2017, the

city applied to include Lambert in the APPP. (As of this writing, the city is still working

to select a private partner and submit a nal application to the FAA.) According to the

application, the reasons for the change are not unlike other applications to the APPP. The

city believes a private partner would help bring in more revenue from non-aeronautical,

cargo and adjacent land which would boost the regional economy.

78

In addition, the city explicitly wants to secure an upfront payment from a private partner

and then use that revenue for projects elsewhere in the city, a process known as asset

recycling. The city’s application stated that it expected to “free up more than one billion

in capital” for non-airport uses. St. Louis Mayor Francis Slay specically mentioned the

North-South MetroLink light-rail expansion as a project that could be funded with proceeds

from the lease.

79

The city still needs to clear several hurdles, including securing support

76 Rahm Emanuel, “Why I Said ‘No’ to the Midway Deal,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 2013.

77 Principato, 2017.

78 City of St. Louis, “Preliminary Application for the Federal Aviation Administration’s Airport Privatization

Pilot Program Under 49 U.S.C. §47134,” March 22, 2017.

79 Mayor Slay retired in 2017, and the new Mayor Lyda Krewson continued to pursue privatization and recent-

ly selected an advisory team for the proposal. Jacob Kirn, “City Picks Advisor Team for Lambert Privatiza-

tion Process,” St. Louis Business Journal, January 26, 2018.

Eno Center for Transportation

17

Deal or No Deal

from the city boards and selecting a private sector deal to lease the airport.

Detractors say that recent bond rating upgrades indicate that the airport is already well

operated, and the city could lose control over how the airport is run under a privatized

lease.

80

The city will have to determine whether the one-time infusion of cash is worth

ceding control, and airlines operating in St. Louis have not yet indicated their support.

81

Critics are also concerned about transparency and a conict of interest since a non-prot

organization—Grow Missouri Inc.—put up over $100,000 for the preliminary application to

the FAA, and local leaders were largely unaware of the application.

82

Grow Missouri was

recently selected as an advisor to the city on the privatization initiative, further rankling

local ofcials since the organization will only be paid if the deal is executed.

83

It is unknown if the city will go forward with a nal application to privatize Lambert or if

the airlines serving it would approve (Southwest carries almost 60 percent of Lambert’s

passengers).

84

However, it does appear that the primary impetus for the effort is to extract

airport value for other city infrastructure projects rather than solving any specic airport-

related problem. While asset recycling has proven effective in Virginia, Illinois, Indiana,

and throughout Australia, it is still relatively untested in the United States. That does

not mean St. Louis should not experiment with such new approaches, but it is unclear if

such an arrangement would address the airport’s problems any better than the current

arrangement.

85

3.5 Westchester County Airport

The Westchester County Airport is located about 60 miles, or a one-hour drive, south of

Stewart Airport in New York. The airport is owned by the county and is served by ve

commercial airlines. While categorized as a “small” hub by the FAA, the airport serves ve

times as many passengers as Stewart and more than comparable small hubs in Fresno,

Akron, or Colorado Springs.

86

Only 16 percent of trafc at Westchester is commercial

aviation. The vast majority of trafc is general aviation, making it one of the busiest

80 Moody’s Investors Service, “Moody’s Assigns A3 with Positive Outlook to St. Louis (MO) Airport’s Sr 2017

Airport Revenue Bonds,” May 27, 2017.

81 “Aldermen, Experts Debate Pros and Cons of Lambert Privatization,” CBS St. Louis, January 18, 2018.

82 Leah Thorsen and Koran Addo, “Slay Wants to Look at Putting Lambert Airport Under Private Manage-

ment,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 23, 2017.

83 Celeste Bott, “Top City Ofcials Vote to Begin Exploration of Privatizing Lambert,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch,

June 14, 2018.

84 Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Airports – St. Louis International,” January-March2018, U.S. Depart-

ment of Transportation, June 23, 2018.

85 For its part, the region has made several attempts to position itself as a hub for air cargo, particularly from

China. One prominent initiative failed in 2013, and ofcials are working to launch another shortly. Leah

Thorsen, “Air-cargo Facility at Lambert Named in Report of Trump-Backed Projects,” St. Louis Post-Dis-

patch, January 24, 2017.

86 Eno analysis of FAA data “Passenger Boarding (Enplanement) and All-Cargo Data for U.S. Airports.”

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

18

business aviation hubs in the United States.

87

A private contractor has run Westchester

since the mid-1940s, specically AvPorts since 1977.

In 2016, the county applied to participate in the APPP. The primary motivation was to

balance the county’s 2017 budget by redirecting resources used to operate the airport

to other county services. Soon after, a $130 million, 50-year deal was announced then

subsequently retracted by the county after concerns about the lack of transparency

were voiced.

88

A formal request for proposals was released in 2017, and later that year,

Macquarie Infrastructure Corporation’s $1.1 billion, 40-year bid was chosen. A little less

than half the money would support airport capital improvements with the remainder

coming in as a payment to the county, of which $300 million would be upfront and applied

directly to the county’s general fund. The county board has yet to approve the deal, and

there are indications that the new county executive will reconsider the initiative.

89

Though not as nationally prominent as the others, the proposal to privatize Westchester’s

airport is highly controversial locally. In addition to concerns about transparency, citizen

groups have formed to protest the feared increases in aircraft trafc and concerns about

damage to an adjacent reservoir. The former county executive who championed the

privatization proposal stated publicly that the goal was to monetize it for budgetary

purposes. He said that AvPorts was “doing a good job” operating the airport and that the

airport was in good condition.

90

The drive to privatize the airport appears to be a difcult

proposition in this case.

3.6 International Examples

There is considerable academic literature from experts who maintain that privatization

will create additional competition and lower prices for travelers.

91

The best examples for

this argument largely lie overseas. While the role of the private sector in infrastructure

is very different in the United States, it is useful to understand some of the key lessons

and experiences with airport privatization in other countries. A recent Reason Foundation

privatization report notes that the outright sale of an airport (or part of it) may be common

in Europe, but the model for the rest of the world is a long-term lease or concession, as

allowed under the APPP.

92

Rules and regulations may differ, but the main motivations for

considering different models of privatization persist: improving management, generating

revenue for governments, securing private capital for infrastructure improvements, and

87 “General Aviation,” WestchesterGov.Com, 2018.

88 Curt Epstein, “Major NYC Bizav Hub to Seek Privatization,” AIN Online, November 14, 2016.

89 Joseph De Avila, “Westchester County Rethinks Plan to Privatize Airport,” Wall Street Journal, May 17,

2018

90 Transcript of Rob Astorino’s Telephone Town Hall, September 27, 2017.

91 See e.g.,: Clifford Winston and Gines de Rus, Aviation Infrastructure Performance: A Study in Comparative

Political Economy, Brookings Institution, 2008.

92 Robert Poole, “Annual Privatization Report: Air Transportation,” Reason Foundation, 2017.

Eno Center for Transportation

19

Deal or No Deal

leveraging airport amenities like catering and parking. Other issues like access to capital

markets are less relevant.

For example, as with San Juan and Chicago, some countries—including Japan, Spain, and

Portugal—are intentionally pursuing airport privatization as an effort to manage very

high levels of sovereign debt.

93

Most prominently, Greece privatized more than a dozen

mostly tourist airports for $1.3 billion in 2015, specically intending to curb their national

economic crisis.

94

Financially strained national and state authorities in Brazil embarked on

a large-scale initiative to privatize many public assets, including airports, in order to cover

costs like payroll and pensions.

95

If the key metric for success is government debt relief,

these experiences were certainly successful. But in Brazil, for example, one concessionaire

recently returned its airport to the government, and overall seat capacity is down.

96

Of course, part of the problem is Brazil’s severe economic downturn, but this outcome

reinforces the limitations of what privatization can accomplish.

Other nations continue to lean heavily on private investors to both build out their

infrastructure and operate certain assets. India is a prime example of a rapidly expanding

country that turned to the private sector to bring in new capital for its airports. In

2009 and 2011, the government allowed the private operators of the Mumbai and Delhi

airports to assess a special development fee on passenger tickets to help cover the cost of

modernization.

97

The result was a sharp increase in passenger fares.

98

The United Kingdom has always been on the forefront of infrastructure privatization and

led the global effort on airports with its $2.5 billion sale of the British Airports Authority

and its seven airports in 1987. In doing so, it allowed the airports to impose market

pricing and to charge airlines higher landing fees during peak travel times at the London

airports. While these charges increased operational efciencies, they also increased costs for

passengers.

99

In many cases, the international experience is not unlike that in the United States in

that a myriad of factors beyond governance—such as location, size, market, regulations,

competition—determine the success of an airport’s operations, the cost of passenger tickets,

93 Bernard Chow and Colin Smith, “Airport Transactions: Taking Off Around the Globe,” in The New Normal

for Airport Investment, PwC, 2013.

94 Niki Kitsantonis, “14 Airports in Greece to Be Privatized in $1.3 Billion Deal,” New York Times, December

14, 2015.

95 Marla Dickerson and Luciana Magalhaes, “Strapped Brazilian Governments Embrace Privatization,” Wall

Street Journal, December 24, 2016.

96 CAPA - Centre for Aviation, “Brazil Airport Privatisation: ‘Steak with Bone’ as the Economy Slowly Recov-

ers,” 2017.

97 Moses George, “Development Fee in India Airports - A Case Study,” Journal of Air Law and Commerce, Vol.

80 (17), 2015.

98 P.R. Sanjai, “As Indian Airports Raise Fees, Others Choose to Cut Them,” Mint, February 12, 2009.

99 Bijan Vasigh and Mehdi Haririan, “An Empirical Investigation of Financial and Operational Efciency of

Private Versus Public Airports,” Journal of Air Transportation, Vol. 8 (1), 2003.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

20

and the quality of non-aeronautical services like catering, parking and other amenities.

For this reason, one analysis of major airports in the United States and Europe found no

signicant relationship between airport productivity and the ownership model.

100

Another

study found that fully or partly privatized airports are among the most productive,

while those operated by multi-purpose port authorities are the least.

101

Whether airports

are natural monopolies is hotly debated over the world. Even less clear is whether the

ownership and governance model have any signicant inuence over that debate.

4. Policy and Practice Implications

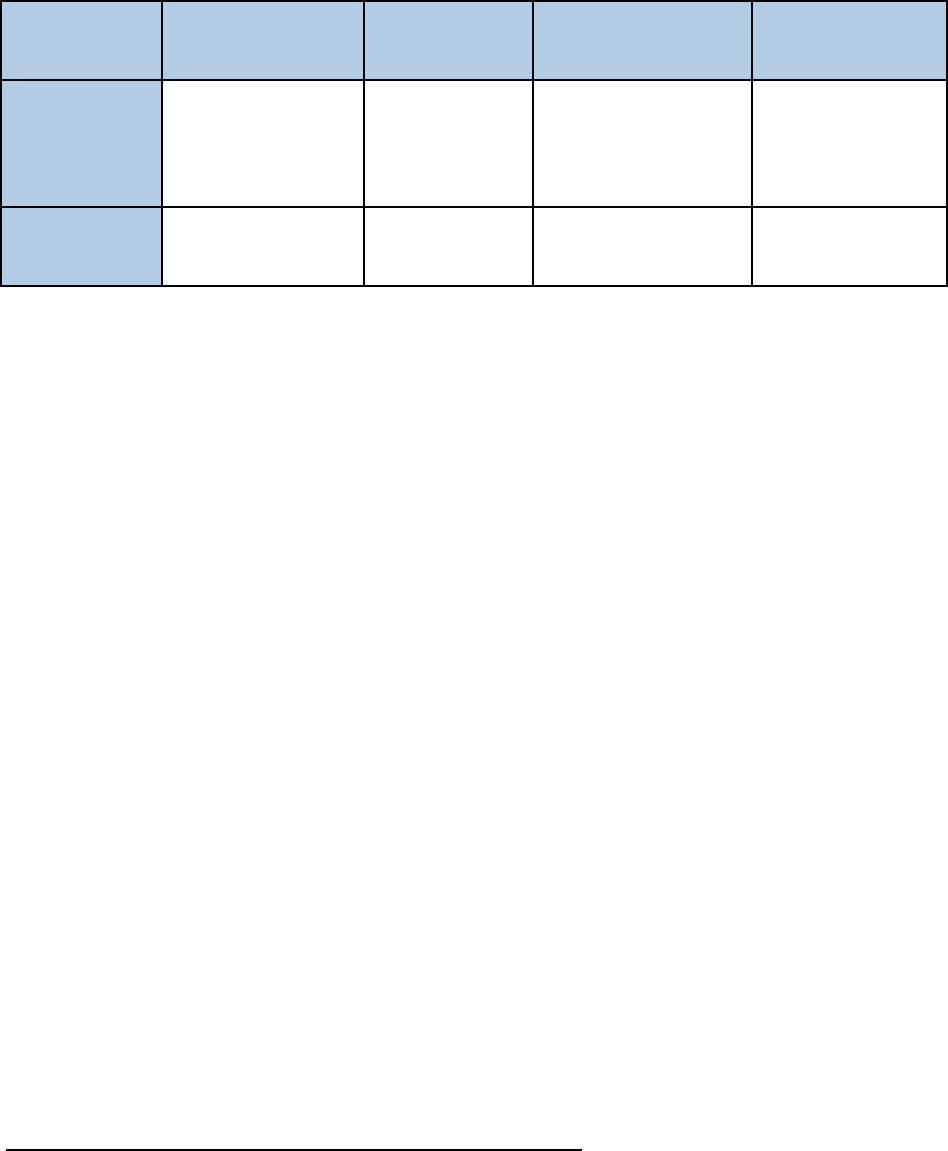

Despite the prevalence of airport privatization around the world, there is only one

successful example in the United States. While there has been stated interest from time to

time, only eight commercial airports have even applied to participate in the APPP and only

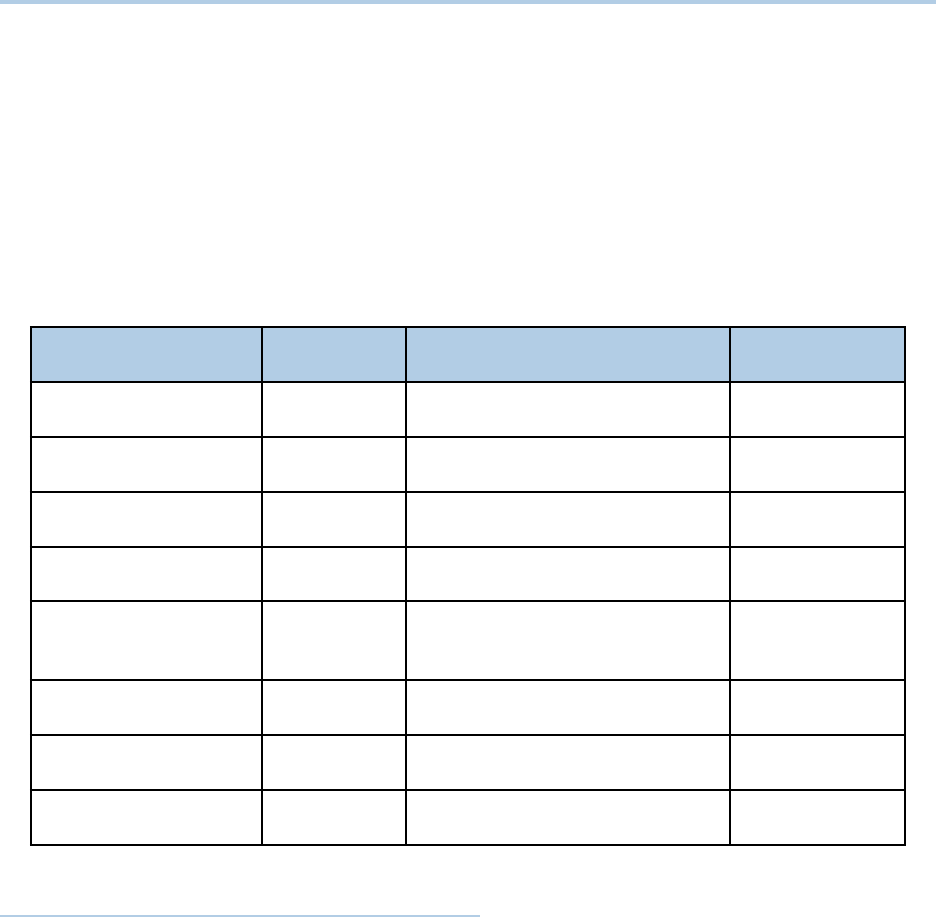

two are large hubs (see Table 3).

102

This analysis demonstrates that there are several likely

reasons for this lack of activity along with key implications for policy and practice.

Table 3: Status of all Commercial Airports APPP Applications

Airport Name

Application

Date

Status Hub Type

St. Louis Lambert

International Airport

2017 Preliminary application accepted Large

Westchester County

Airport

2016 Preliminary application accepted Small

Chicago Midway

International Airport

2006 and

2013

Preliminary application

withdrawn

Large

Luís Muñoz Marín

International Airport

2009 Final application approved Medium

Louis Armstrong New

Orleans International

Airport

2009 Application withdrawn Medium

Stewart International

Airport

2003

Final application approved. No

longer participates.

Nonhub

Rafael Hernández

Airport

2000 Application withdrawn Nonhub

Niagara Falls

International Airport

1999 Application withdrawn Nonhub

Source: FAA, “Airport Privatization Pilot Program,” 2018.

100 Bijan Vasigh and Javad Gorjidooz, “Productivity Analysis of Public and Private Airports: A Causal Investi-

gation,” Journal of Air Transportation, Vol. 11 (3), 2006.

101 Tae Oum, and others, “Ownership Forms Matter for Airport Efciency,” Journal of Urban Economics, 2008.

102 One analysis asserts that private equity rms will be the ones most interested in small airports with one

terminal and less than 5 million passengers that are poised to grow in a short period. Pension funds would

likely seek large, stable assets that produce returns over time. See: Chow and Smith, 2013.

Eno Center for Transportation

21

Deal or No Deal

Regulatory hurdles. As discussed, there are signicant restrictions on the use of airport

revenue and potential concerns about paying back federal money invested in privatizing

airports. The changes to the APPP incorporated in the U.S. House of Representatives’

pending FAA reauthorization may address this somewhat by combining all the possible

exemptions, however the bill’s language does not remove the hurdle completely. The FAA

still has the ultimate authority to approve or deny all applications, and the process is long

and time-consuming. According to the GAO, Midway and LMM airports took 83 and 38

total months, respectively, to navigate the privatization process.

103

While this also includes

time the airports spent negotiating with their airlines, the regulatory path is challenging.

Negotiations with labor. Organized labor monitors many aspects of infrastructure

privatization closely in order to ensure both their public and private sector members

are protected.

104

The potential effects of privatization on airport workers are largely

dependent on the state and local laws for a particular airport. U.S. Code protects any

collective bargaining agreement in place before lease negotiations, and the U.S. House’s

FAA reauthorization proposal does not attempt to change that. But this means private

rms have to navigate different sets of rules for different airports and the political climate

around labor on a case-by-case basis. The GAO references Chicago and San Juan where

airport public ofcials voiced strong support for allowing workers to keep their jobs, or

similar ones, although the APPP does not require it.

105

At the same time, labor has its

hands full monitoring existing private contracts.

106

Financial considerations. Most airports are owned by municipal governments, have robust

revenue streams, and can borrow money at tax-free government rates. Private owners

or concessionaries do not always bring “new” money to the table, would borrow at higher

rates, and would not be able to take advantage of federal grant programs as publicly owned

airports can. Of course, in certain instances where the public authority is saddled by severe

debt loads, private capital is very attractive—especially as an upfront payment that the

government may be able to repurpose through asset recycling. However, asset recycling has

no direct benet for the airport itself, and few cities and states have the expertise to execute

such complex transactions.

Concerns about transparency. Another common element between the United States and

other countries is the call for greater transparency and collaboration in decision-making.

While this is not by itself particularly insightful, it seems to be a particularly acute problem

for airport privatization. In St. Louis and San Juan, local ofcials expressed concern about

103 U.S. GAO, 2014.

104 Ernico and others, 2012.

105 U.S. GAO, 2014.

106 As of last year, many of the workers at Dulles and National airports were making only $7.25/hour. They

received an increase to $11.25, but that does not include a requirement to have health insurance or a labor

peace agreement. Luz Lazo and Lori Aratani, “After a Two Year Fight, Contract Workers at National and

Dulles Airports Win a Pay Increase,” Washington Post, April 19, 2017.

Deal or No Deal Eno Center for Transportation

22

being left out of early deliberations. Chicago was particularly saddled with concerns for how

both the parking meter and rst Midway deals were prearranged. The recommendations

from that city’s Inspector General are a good framework for future deals, including

considering alternatives that solve short-term budget problems.

107

Perceptions of problems. Since most state and local governments in the United States have

access to money and many airports are well run as public assets, it not clear whether the

APPP is relevant to most airports. The biggest problems stem from passenger frustration

with disruptions caused by major construction and expansion projects at large airports such

as Chicago O’Hare, Los Angeles International, and all three major airports in metropolitan

New York City. This suggests that addressing travelers’ concerns is more a question of

working with private partners on aviation infrastructure, rather than operations and

management—the two functions that are often contracted out already. Instead, public-

private partnerships (P3) to build, renovate, and modernize new facilities and operate

terminals are an alternative means for capital investment. New York’s LaGuardia’s $4

billion project is the largest P3 for new transportation infrastructure ever in the United

States and will transform the much-maligned airport.

108

Other P3 projects in Denver,

Austin, and New York’s JFK are also underway.

Limitations on market incentives. Privatization broadly promises to bring greater

competition along with a better product and lower prices for consumers.

109

While this works

in many aspects of transportation, airports are problematic because they are inherent

monopolies in regional markets, limiting the incentives for efciencies.

110

Few cities have

more than one airport, and for those that do, the airports are far apart enough to serve

distinct parts of the region. Studies as to whether international examples of airport

privatization abuse their market power are at best inconclusive and even contradictory in

some cases.

111

107 City of Chicago Inspector General, 2009.

108 Andy Winkler, “Policy Check-In: Status of Airport P3s in the U.S.” Bipartisan Policy Center, 2017.

109 “The Promise and Pitfalls of Privatizing Public Assets,” The Economist, June 22, 2017.

110 Ellis Juan, “Privatizing Airports – Options and Case Studies,” The Word Bank, Note No. 82, June 1996.

111 Steven Morrison, Cliff Winston, “Delayed! U.S. Aviation Infrastructure Policy at a Crossroads,” Brookings,

2016; Stephen King, “A Privatized Monopoly is Still a Monopoly, and Consumers Pay the Price,” The Conversa-

tion, June 23, 2014.

Eno Center for Transportation

23

Deal or No Deal

5. Conclusion

U.S. airports face a host of challenges, yet full privatization and long-term leases are not

likely to solve them. Instead of starting with the question of whether an airport should

be privatized, policymakers and regional leaders need to ascertain the root problem or

problems they are trying to solve and assess all potential solutions. Privatization can make

sense for an airport in dire straits. If an airport has an intractable problem with poor

management or is so heavily debt-laden that it is unable to invest, privatization might

directly address those problems as it did in San Juan.

But if seeking to increase competition, decrease costs, and improve management, airports

already have a host of tools at their disposal that fall short of navigating a complex

regulatory and legal process. Airports regularly engage the private sector through service

and management contracts as well as private nancing and construction of terminals

and runways. Most privatization efforts today are either ideological or are rooted in asset

recycling efforts for one-time government cash infusions for other priorities. The latter

can be a positive net gain, but does not solve any specic airport problem nor does it give

airport owners exibility and control in the long term. Privatization for its own sake is bad

public policy. But airports should have it available as a tool and evaluate it along with all

other options.

Even so, airport privatization in the United States currently faces a number of major

practical, nancial, political, and programmatic hurdles. Even with the recent changes to

the tax code and efforts to make private borrowing for public infrastructure more attractive,

public authorities and governments still have access to tax-exempt revenue bonds. The

restrictions on revenue use repayment may be addressed by amendments to the APPP, but

regulatory barriers inherent in the program remain difcult to overcome. One privatization

expert pointedly referred to the perception that the APPP itself is not so much a pathway,

but is rather an “obstacle course” for privatization due to its limiting and cumbersome

process.

112

Even with Congress’ proposed changes in the FAA reauthorization bill, those

impediments may not be overcome any time soon. In the meantime, the aviation industry

should build on their structural strengths, including robust revenues, access to tax exempt

borrowing, and experience engaging with the private sector, to improve airport conditions

using P3s and other tools.

112 Robert Poole, “Does Airport Privatization Have a Future in the U.S.?” Eno Transportation Weekly, March 6,

2017.

www.enotrans.org

1629 K St. NW

Suite 200

Washington D.C. 20006

CONTACT US:

publicaffairs@enotrans.org / 202-879-4700

Twitter: @EnoTrans / @EnoTranspoWkly