European Asylum Support Offi ce

SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION

EASO

Prac� cal Guide on

age assessment

Second edi� on

EASO Prac cal Guides Series

© European Asylum Support Office, 2018

Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of

the information contained herein.

Print ISBN 978-92-9494-648-5 doi:10.2847/236187 BZ-01-17-965-EN-C

PDF ISBN 978-92-9494-647-8 doi:10.2847/292263 BZ-01-17-965-EN-N

Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers

to your questions about the European Union.

Freephone number (*):

00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11

(*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you).

More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu).

European Asylum Support Oce

SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION

EASO

praccal guide on

age assessment

Second edion

EASO Praccal Guides Series

The EASO practical guide on age assessment publication builds upon the information and

guidance on the age assessment process and the overview of the age assessment methods

already analysed in the EASO age assessment practice in Europe (2013). It offers practical

guidance, key recommendations and tools on the implementation of the best interests of

the child when assessing the age of a person from a multidisciplinary and holistic approach.

It also brings up-to-date information on the methods conducted by EU+ states and on new

methods still not in use as possible or future alternatives.

EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 5

Abbreviaons ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7

Execuve summary

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 11

I

ntroducon

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

��������������������������������� 13

Chapter 1 Circumstances of age assessment ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16

The age assessment from a fundamental rights perspecve

��������������������������������������������������������������������������18

C

hapter 2 The best interests of the

ch

ild and procedural safeguards

��������������������������������������������������������������������2

0

The best interests of the child

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������2

0

Assessing the best interests of the child for the purpose of the age assessment

�������������������������������������21

A

pplying the principle of the benet of the doubt ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 22

Guardian/representave

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2

6

Right to informaon

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

����� 27

Right to express their views and to be heard ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28

Informed consent and right of refusal

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������29

Condenality principle and data protecon for safety consideraons

���������������������������������������������������30

Q

ualied professionals experienced with children

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 31

T

he least intrusive method ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 31

Accuracy and margin of error

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������34

C

ombining intrusiveness and accuracy �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������36

Right to eecve remedy

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 37

C

hapter 3 The age assessment process: implemenng a muldisciplinary and holisc approach ����������������������38

Implemenng a holisc and muldisciplinary approach to the

ag

e assessment process

�����������������������������3

8

Flow chart of the age assessment process �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 40

Guidance on the age assessment process ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 41

When considering whether age assessment is necessary or not

��������������������������������������������������������������� 41

When conducng age assessment

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 42

Chapter 4 Overview of the age assessment methods

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������44

Flow chart of the methods

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

��44

Guidance on the gradual implementaon of methods ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 45

A.

Non-medical methods ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 47

B. Medical methods (radiaon-free)

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5

2

C. Medical methods (using radiaon)

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 56

C

hapter 5 Final recommendaons

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6

0

Annex 1 Glossary

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������64

Annex 2 The best interests of the child and age assessment: praccal tools

������������������������������������������������������ 71

A. T

he best interests assessment form ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������73

B

. The best interests of the child checklist for the purpose of age assessment

�������������������������������������7

5

Annex 3 Legal and policy framework

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������78

Annex 4 Overview of the methods and procedural safeguards in use in the

ag

e assessment processes

�������10

5

Annex 5 Bibliography

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 111

Contents

EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 7

Abbreviaons

ADCS Association of Directors of Children’s Services Ltd is the national leadership association

in England for statutory directors of children’s services and their senior management

teams

AGFAD German Association of Forensic Medicine

ALARA used in radiation safety, it stands for ‘as low as reasonably achievable’

AMIF Asylum and Migration Integration Fund

APD recast Directive 2013/32/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26

Ju

ne 2013

on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection. It has

also been mentioned as the ‘asylum procedures directive’ recast

APR proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing

a common procedure for international protection in the Union and repealing

Directive

20

13/32/EU

AT Austria

ATD Directive 2011/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5

Apr

il 2011

on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims,

and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA. It has also been cited as

the ‘anti-trafficking directive’

BE Belgium

BG Bulgaria

BIA best interests assessment

BIC best interests of the child

BID best interests determination

CEAS Common European Asylum System

CFR Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

COI country of origin information

CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

CT/CAT computed tomography/computed axial tomography

CY Cyprus

DE Germany

DK Denmark

Dublin III

regulation recast

Regulation (EU) No

60

4/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26

Ju

ne

2013 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State

responsible for examining an application for asylum lodged in one of the Member

States by a third-country national or a stateless person (recast)

EASO European Asylum Support Office

EE Estonia

EMN European Migration Network

ES Spain

8 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion

EU+ states: EU Member States plus Norway and Switzerland

EU European Union

Eurodac European Asylum Dactyloscopy Database

Eurodac regulation

recast

Regulation (EU) No 603/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of

26

Ju

ne 2013 on the establishment of ‘Eurodac’ for the comparison of fingerprints

for the effective application of Regulation (EU) No

60

4/2013 establishing the criteria

and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an

application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a

third-country national or a stateless person and on requests for the comparison with

Eurodac data by Member States’ law enforcement authorities and Europol for law

enforcement purposes, and amending Regulation (EU) No

10

77/2011 establishing a

European agency for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the

area of freedom, security and justice (recast)

FRA European Union Agency for Fundamental Human Rights

FI Finland

FR France

1951 Geneva

Convention

United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees 1951 (and the Protocol

Relating to the Status of Refugees 1967)

HU Hungary

ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross

IE Ireland

Implementing

Regulation

No

11

8/2014

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No

11

8/2014 of 30

Ja

nuary 2014 amending

Regulation (EC) No

156

0/2003 laying down detailed rules for the application of

Council Regulation (EC) No

34

3/2003 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for

determining the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application

lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national

IOM International Organisation for Migration (United Nations Migration Agency)

IP international protection

IT Italy

JRC Joint Research Centre, the European Commission’s science and knowledge service

which employs scientists to carry out research in order to provide independent

scientific advice and support to European Union policy

LT Lithuania

LU Luxembourg

LV Latvia

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

MS EU Member State(s)

MT Malta

NGO non-governmental organisation

NIDOS NIDOS Foundation (guardianship institute for unaccompanied minor applicants for

international protection in the Netherlands)

NL Netherlands

EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 9

NO Norway

OHCHR Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights

PL Poland

PT Portugal

QD recast Directive 2011/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13

De

cember

2011 on standards for the qualification of third-country nationals or stateless persons

as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or for

persons eligible for subsidiary protection and for the content of the protection

granted (recast). It has also been cited as the ‘qualification directive’ (recast)

RCD recast Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013

laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection

(recast). It has also been cited as the ‘reception conditions directive’ recast

RO Romania

SCEP separated children in Europe programme

SE Sweden

SIS a large-scale information system that supports external border control and law

enforcement cooperation in the Schengen area

SI Slovenia

SK Slovakia

SLTD a database that contains records on stolen, lost or revoked travel documents such

as passports, identity cards, UN laissez-passer or visa stamps

THB trafficking in human beings

UAM unaccompanied minor(s)

UK United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Unicef United Nations Children’s Fund

VIS Visa Information System

EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 11

Execuve summary

Age assessment remains a complex process with possible far-reaching consequences for applicants

undergoing the assessment. Age assessment methods and processes differ across Member States and

reliable multidisciplinary and rights-compliant age assessment processes are not always guaranteed. In

view of these challenges, the communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the

Council, ‘The protection of children in migration’ (COM(2017) 211 of 12

Ap

ril 2017), called for the European

Asylum Support Office (EASO) to update its guidance on age assessment in 2017.

The focus of this publication is to provide guidance on the consideration of the best interests of the child

(BIC) when assessing the need for the age examination but also when devising and undertaking an age

assessment using a holistic and multidisciplinary approach, with particular attention to the needs and

circumstances of the person.

To support the authorities on the implementation of the principle of the BIC, this publication:

▪

analyses the impact of age assessment on other rights of the applicant and the motivation for the

assessment;

▪

offers guidance on the application of the necessary principles and safeguards in the assessment

process;

▪

describes how to implement the assessment process using a holistic and multidisciplinary approach;

▪

provides a visual model of the potential process highlighting the gradual use of methods to prevent

unnecessary examinations;

▪

explores new methods used to assess an applicant’s age, the latest developments of the methods

already in use and the impact of each method on the safeguards and rights of the applicant;

▪

provides key recommendations to address practical challenges that might appear prior to, after

and at different stages during the process;

▪

contains a set of tools and reference documents to complement the information provided in this

practical guide:

▪

a glossary with key terms,

▪

international, European and national legal framework and policy-guidance documents relevant

to the topic,

▪

practical tools for ensuring the BIC (a form and a checklist), and

▪

an updated overview of the methods and procedural safeguards in use in the EU+ territory.

A number of challenges faced during the undertaking of the age assessment process, such as the

(in)sufficient motivation for an age assessment, the limitations of the methods in use concerning

intrusiveness and accuracy, fragmented estimations based only on the physical appearance, the primary

use of medical methods (in some cases only ionising ones), repetitive examinations being conducted

on the same applicant in different Member States (MS) or a low implementation of key safeguards in

the process (i.e. the lack of guardian/representative or effective remedy) have been identified and are

addressed in this publication.

In response to these challenges, EASO has devised key recommendations, which will be discussed in depth

in this publication. These can be summarised as follows.

□ The BIC should be observed not only when a child is identified as such but also when there are doubts

as to whether the applicant may be a child.

□ Age assessment should not be a routine practice. The necessity of the assessment should be duly

justified based on substantiated doubts on the stated age.

□ The implementation of the principle of the BIC requires a child-centred age assessment which should

place the child at the centre and be adapted to the specific needs of the applicant (gender, range of

disputed age, cultural background, etc.).

12 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion

□ Benefit of the doubt must be given as soon as doubts on the claimed age appear, during the age

assessment and until conclusive results are provided. The applicant should be considered and treated

as a child until he or she is found to be an adult.

□ The child, or the presumed child, must be appointed a guardian/representative who ensures that

the child can participate in the assessment, has been informed about the age assessment process

in a child-friendly, gender-sensitive and age-appropriate manner in a language that the child can

understand and does, in fact, fully understand the assessment process. This information is essential

to allow the child to express views, wishes and opinions and make an informed decision to participate

in the process.

□ The age assessment process must be conducted using a holistic and multidisciplinary approach which

ensures that all the necessary safeguards and principles explored are in place and the rights of the

applicant are protected.

□ Since no single method currently available can determine the exact age of a person, a combination

of methods assessing not only the physical development but also the maturity and the psychological

development of the applicant can reduce the range of age in question.

□ No method involving nudity or the examination, observation or measurement of genitalia or intimate

parts should be used for age assessment purposes.

EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 13

Introducon

Why was this second edion developed?

As mentioned in the EU action plan on unaccompanied minors (2010-2014), and due to the concerns on

the reliability and intrusiveness of methodologies in place to assess the age of the applicants, EASO was

entrusted with developing a publication which compiles best practices on age assessment. A first edition

was published in December 2013. Similar concerns about the challenges in the age assessment process

were once again raised by national authorities during the third EASO Annual Conference on Children

held in December 2015 in Malta. In practice, age assessment, and in particular some of the methods,

has rapidly evolved since 2013. It is thus considered to be an opportune time for further reflection and

analysis of the latest developments. In line with the conclusions of the conference and the Commission

communication on the protection of children in migration

(

1

), EASO has developed this new edition

including updated information and enhanced recommendations on the age assessment process. For

this purpose, EASO further mapped the age assessment methodologies and procedural safeguards used

in the EU+ territory in 2016. The key findings of this research can be found throughout the publication

in boxes entitled ‘Key findings from EU+ states’ practice’, and examples from practice have been added

where relevant and in Annex 4.

How does this second edion relate to other EASO support tools?

EASO’s mission is to support EU Member States and associated countries (Liechtenstein, Norway and

Switzerland) on the implementation of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). This support is

delivered, in part, through common training, a common level of quality and common country of origin

information (COI). As with all EASO support tools, this publication is based on the common standards of

the CEAS. Furthermore; this publication should be seen as a complement to the other EASO tools that

address child-sensitive asylum processes, in particular the EASO practical guide on family tracing (

2

) and

the EASO training module on interviewing children

(

3

)�

What is the content of this publicaon?

This second edition contains a set of reference and guidance materials on age assessment as well as a

mapping of the current state of play in the EU+ states.

In a nutshell, the edition is structured around five interlinked pillars.

▪

The first chapter, Circumstances of age assessment, is an introduction to the topic, addressing the

preconditions, motivation and objectives of the age assessment process.

▪

The second chapter, Best interests of the child and procedural safeguards, addresses how the

principle of the BIC, as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

and in the EU asylum acquis, can be operationalised and the procedural safeguards implemented

in the age assessment process.

▪

The third chapter, The age assessment process: implementing a multidisciplinary and holistic

approach, analyses how the process should be conducted using a multidisciplinary and holistic

approach and according to the guidance contained in this publication. It also includes a flow chart

to visualise the main steps to be followed when age assessment needs to be undertaken.

(

1

) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council — The protection of children in migration — COM(2017) 211, 12 April 2017,

available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20170412_communication_on_

the_protection_of_children_in_migration_en.pdf

(

2

) Available at EASO’s website: https://www.easo.europa.eu/training-quality/vulnerable-groups

(

3

) Further information available at EASO’s website: https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EASO_TRAINING_BROCHURE_EN-2016.pdf

14 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion

▪

The fourth chapter, Overview of the age assessment methods, covers the latest developments

in methods already explored in the first edition as well as new methods addressing their potential

(positive and negative) impact on the safeguards. Particular attention is given to methods that

were not in use in 2013 or that have evolved substantially since then.

▪

The fifth chapter, Final recommendations, compiles key recommendations that have been

formulated to enhance an efficient age assessment process while guaranteeing children’s rights.

This publication is completed by a series of annexes

�

▪

Annex 1: Glossary

This annex is aimed at facilitating the identification and/or developing a common understanding

of the most relevant terms used in the age assessment process.

▪

Annex 2: Best interests of the child and age assessment: practical tools

This annex consists of a best interests assessment (BIA) form and a BIC checklist to assess whether

the particular age assessment process guarantees that the necessary procedural safeguards that

ensure the adequate protection of the rights of the individual child are in place.

▪

Annex 3: Legal framework and policy guidance

This annex is intended to serve as a reference point for identifying the relevant instruments and

provisions at international, European and national level. In addition, it includes soft-law guidance

instruments and relevant case-law. It also encompasses relevant policy-guidance references on

this topic.

▪

Annex 4: An overview of EU+ states’ practices on age assessment

This annex includes the methodology and procedural safeguards used by the EU+ states when

conducting the process.

▪

Annex 5: Bibliography

A compilation of the sources consulted to develop or inspire the content of this publication.

What is the scope of this second edion?

This publication provides further guidance on the core aspects of the age assessment process such as

the holistic and multidisciplinary approach, the implementation of the principle of the BIC and an update

of the information collected for the first edition of the publication. While this publication addresses age

assessment for the specific purpose of international protection procedures, it may also serve as a useful

reference in other contexts where age assessment is required (migrant children, minimum age of criminal

responsibility, etc.).

As significant aspects, such as the applicable methodologies, evolve rapidly, this guide is not meant to

exhaust the topic of age assessment. Therefore, depending on the needs of the target group, additional

editions of this guide may be required.

How was this second edion developed?

This publication was developed by EASO and reviewed by the European Commission, EU agencies, experts

from EU+ states and international and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Valuable input was further

provided during two ad hoc working group meetings held in September 2016. The diverse composition of

the working groups guaranteed a comprehensive and multidisciplinary contribution from experts. These

included social workers, forensic anthropologists and radiology researchers, as well as policy officers

and reception officers. There were also asylum case officers with expertise on children from EU+ states’

representatives (BE, IE, NL, LT, NO), the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) and the United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as well as from relevant international organisations

and NGOs with expertise in the field, such as the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), the Nidos

Foundation (NIDOS), the UK Red Cross and the separated children in Europe programme (SCEP) within

EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 15

Defence for Children International. This publication is the product of combined expertise, reflecting the

common standards and the shared objective to achieve safe and efficient age assessment processes within

high-quality international protection procedures.

How should this guide be used?

For the purpose of this guide, some of the terms that are commonly used in the content of this publication

(age assessment, biological age, chronological age, child, guardian, EU+ states) with their specific meanings are

defined below for better comprehension. The glossary (Annex

1 t

o the publication) contains further information

on these terms and additional terminology identified as useful for the age assessment stakeholders.

Age assessment is the process by which authorities seek to estimate the chronological age or range of age

of a person in order to establish whether an individual is a child or an adult.

Biological age is defined by an individual’s present position with respect to his or her potential life span,

meaning that an individual may be younger or older than his or her chronological age.

Chronological age is measured in years, months and days from the moment when the person was born.

Child and minor are considered synonyms (any person below the age of 18) and both terms are used in

this publication. EASO’s preferred term is ‘child’; however, the term ‘minor’ is used when it is explicitly

referenced by a legal provision. For the purpose of this publication focusing on asylum-seeking children,

the term used to refer to the person whose age is not established is the applicant�

As

stated above, the expression unaccompanied child is applied as a synonym of unaccompanied minor

and is defined as a child/minor who arrives in the territory of the EU+ states unaccompanied by an adult

responsible for him or her, whether by law or by the practice of the state concerned, and for as long as

he or she is not effectively taken into the care of such a person/adult. It includes a child/minor who is left

unaccompanied after he or she has entered the EU+ territory.

There is no general consensus on the definition of guardian and, in practice, a guardian is often assimilated

to the figure of the representative of the child or social worker. However, for the purpose of this guide, a

guardian is considered to be an independent person appointed by a national authority who safeguards

the child’s best interests and general well-being. In the context of the reform of the CEAS

(

4

), the European

Commission has proposed to replace the reference to the ‘representative’ in the current EU asylum legal

instruments to ‘guardian’. As the CEAS reform was still under discussion at the time of this publication, the

reference to guardian/representative is used throughout the text.

The EU asylum acquis consists of the following set of EU legal instruments: the ‘reception conditions

directive’ recast, the ‘asylum procedures directive’ (APD) recast, the ‘qualification directive’ recast,

the ‘temporary protection directive’, the ‘Dublin regulation III’ and the ‘Eurodac regulation’ recast (

5

)�

A compilation of international, European and national provisions and legal instruments related to age

assessment can be found in Annex

3 ‘L

egal framework and policy guidance’ of this publication.

For the purpose of this guide, the EU Member States plus Norway and Switzerland are referred to as

EU+ states

�

(

4

) Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a common procedure for international protection in the Union and repealing

Directive 2013/32/EU (COM(2016) 467 final, 2016/0224 (COD)), available at https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2016/EN/1-2016-467-EN-F1-1.PDF

�

A

t the time of writing, it cannot be known whether the Commission’s proposal will result in a new regulation or what its precise terms will be. The reader should,

therefore, simply be aware that at some point in the future, there is the possibility that the APD (recast) may be repealed and replaced by a regulation with some

amended provisions.

(

5

) The legal texts and their translations are available at:

‘reception conditions directive’ recast, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32013L0033;

‘asylum procedures directive’ recast at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32013L0032;

‘qualification directive’ recast at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32011L0095;

‘Dublin regulation III’ at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32013R0604;

‘Eurodac regulation’ at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32013R0603�

16 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion Circumstances of age assessment

Chapter 1 Circumstances of age assessment

Age is an essential element of a child’s identity. The EU acquis (

6

) as well as the CRC (Article 1) define

childhood by reference to age:

A child/minor is any person below 18 years of age.

Two main consequences derive from this definition. The first one is that the convention applies to every

person under 18

ye

ars of age. Secondly, as established in the EU acquis, any international protection applicant

under 18

ye

ars of age is entitled to child-sensitive procedural safeguards and special reception conditions.

Despite continuously changing, age is an innate characteristic of one’s identity

� As

part of the personal

status of a person it determines the relationship between the state and the person. As such, changes in

age may trigger specific rights and obligations, for example being considered an adult when someone turns

18. However, the age of 18 is not always the determining factor for acquiring new rights and obligations or

full capacity in some aspects such as military service, the emancipation age and minimum age of criminal

responsibility, the age of consent for marriage or the age for employment or sexual relations. Depending

on national legislation, these thresholds may be reached at an earlier chronological age.

When known, the age of a person rules the relation between the person and the state, and consequently

determines Articles 7 a

nd 8 of the CRC establish the following state parties’ age-related key obligations:

▪

register the child after birth;

▪

respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity; and therefore

▪

re-establish in a speedy manner his or her identity.

According to these provisions, all children should be registered at birth and provided with documental

evidence of their identity. However, statistics from the United Nations (

7

) indicate that over the period 2003-

2007, less than 10

% o

f African countries

(

8

) reported the total number of live births, in contrast to the

European countries’ rate (90

%)

. Low birth registration rates in countries of origin is one of the reasons why

international protection applicants may arrive in the EU without documents or with documents that are

considered to be unreliable. The rate of birth registration is not uniform across the main countries of origin

of international protection applicants; for example, in Somalia only 3

% o

f children under 5

ye

ars of age

were registered at birth, while in Afghanistan this number rises to 37 % (

9

) (these percentages relate to the

current birth rate). According to the UN statistics division, that number drops to under 6-10

% f

or children

who were born 14-18 years ago (ages of the unaccompanied children arriving in Europe). Furthermore,

other factors, such as a rural origin or belonging to a minority or particular social group (castes, tribe, etc.),

may hinder access to birth registration. The lack of awareness of its importance or the lack of knowledge

on how to register the birth also deepens the disparity of birth registration within the same country. The

low birth registration rates result in children having difficulties to prove their identity and age through

documentary evidence, and as a consequence may end up unprotected and deprived of the rights they are

entitled to. In addition to the lack of registration, the issuance of birth certificates may not be possible in

countries experiencing war or armed conflict or where the authorities are unwilling to provide them. The

absence of documents that prove that the child is under 18

ye

ars of age can have a direct effect on their

recognition as child right holders. Consequently, children may end up being treated as adults on matters

such as, among others, army service, marriage and access to the labour market and to justice.

As chronological age does not play an important role in the acquisition of an adult status in all cultures, it is

important to take the cultural factor into consideration. In some cultures, children are treated as adults as

soon as they experience certain physical changes or become part of a separate family (for example through

(

6

) See Article 2(d) RCD, Article 2(l) APD, Article 2(k) QD, Article 2(i) Dublin III regulation and Article 2(6) ATD.

(

7

) http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/CRVS/VS_availability.htm

(

8

) Ibid., based on complete registration systems.

(

9

) http://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Birth_registration_May-2016.xlsx

Circumstances of age assessment EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 17

the practice of child marriage). For these reasons, it is common that they may not know their chronological

age and find it difficult to understand its importance in Western cultures. Since the chronological age may

not be an identifying feature for their position in their community or relationship to others (in some regions

children are always registered as having been born on the first of January of the year they were born in,

irrespective of if they were born in any other month), this cultural difference may result in somewhat

vague statements regarding dates of birth or age.

In the context of international protection, the age of the applicant is a key indicator of special protection

needs (

10

) (children, elderly). Belonging to certain age groups triggers the application of special/additional

procedural guarantees during international protection procedures as well as special reception conditions

(such as the right to be placed in suitable and safe accommodation, the right to education and specific

healthcare, the limitation of administrative detention for migration purposes in exceptional cases and

the obligation to look first for viable alternatives to detention). In the case of children, or while there are

doubts about the applicant’s age, theBIC must be given primary consideration throughout the procedure.

Furthermore, age is also significantly relevant for child-specific types of claims (forced/early marriage,

forced recruitment, female genital mutilation, child trafficking, family and domestic violence, forced labour,

prostitution and child pornography)

(

11

)�

Be

yond the context of international protection, the age of a person has implications when involving the

authorities in other procedures, such as giving consent to marriage, reporting underage sexual relationships,

accepting or refusing healthcare treatments, access to the labour market, ensuring access to other rights (right

to education, etc.) and implications for criminal responsibility (minimum age of criminal responsibility, etc.).

Consequently, when the age is unknown and there are substantiated doubts concerning the age, authorities

may need to assess the age of the person to determine whether the person is an adult or a child. In cases

where the applicant is obviously a child or where in absence of contradicting evidence the applicant’s

physical appearance, demeanour and psychological maturity undoubtedly indicate that the applicant is

significantly over 18

ye

ars old, age assessment may not be necessary. However, if there is contradicting

evidence beyond the physical appearance, for example if the person looks significantly over 18 years of age,

but has documentation that indicates that he or she is a child, an age assessment could still be required.

In fact, the necessity of an age assessment implies the existence of doubt about the age and therefore the

possibility of the applicant being a child.

Doubts may arise not only when the applicant is claiming to be a child but also when he or she claims to

be an adult. Children on the move may pretend to be adults in order to avoid the protective measures of

the authorities. This may be done for different reasons; for example, they may wish to continue migrating

to the intended destination and so want to avoid supervised accommodation with, in some cases, limited

freedom of movement or where they would be separated from accompanying adults. Often, children

may claim to be adults to be allowed to work, to marry or because they consider themselves to be adults

responsible for the well-being of the family left behind. However, in other cases, children could just be

following instructions given by smugglers or traffickers. In such cases, smugglers or traffickers try to keep

children off the radar so that they remain unprotected, making them easy prey for later exploitation.

Awareness of this phenomenon can facilitate early identification

(

12

) of a victim, or a potential victim, of

trafficking in human beings (THB) and break the chain of exploitation.

In conclusion, age assessment is the process by which authorities seek to estimate the chronological age

or range of age of a person in order to establish whether an individual is a child or an adult.

The correct identification of an individual as a child or as an adult is crucial to ensure that children’s rights

are protected and guaranteed as well as to prevent adults from being placed amongst children in order to

take advantage of additional rights or safeguards (such as access to education, appointment of a guardian/

representative) that are not afforded to them.

(

10

) See, for instance, the non-exhaustive list of vulnerable applicants provided by Article 21 RCD recast.

(

11

) UNHCR, Guidelines on international protection: child asylum claims under Articles 1(A)2 and 1(F) of the 1951 convention and/or 1967 protocol relating to the

status of refugees, 22 December 2009, HCR/GIP/09/08, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4b2f4f6d2.html�

(

12

) EASO has developed an online tool to assist national authorities on the timely identification of persons with special procedural and/or reception needs

(IPSN), available at https://ipsn.easo.europa.eu/�

18 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion Circumstances of age assessment

The age assessment from a fundamental rights perspecve

A number of fundamental rights enshrined by the CRC and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the

European Union (CFR)

(

13

) are of particular relevance in the age assessment process.

The best interests of the child (Article 3 CRC and Article 24 CFR)

The BIC must be primarily considered in all actions concerning children. They are therefore to be applicable

from the moment that it is considered that the applicant may be below 18

ye

ars of age, throughout the

assessment of the age if such assessment is necessary and until conclusive results indicate that the applicant

is an adult.

Right to non-discrimination (Article 2 CRC and Article 21 CFR)

Every person should be treated with objectivity and be individually considered. It is crucial to avoid

preconceived ideas about certain nationalities, ethnicities, etc. when assessing age.

Right to identity (Articles 1, 7 and 8 CRC)

Age is as much a part of a person’s identity as their name, nationality, citizenship and family status are.

It determines the rights and obligations of a person as well as the state’s obligations towards the person

(e.g. to provide protection, education, healthcare). One of these obligations is to reinstate the identity of

someone who has been unlawfully deprived of it, effectively obliging the state to provide proof of it and to

guarantee the recognition and respect of these rights by others. An incorrect age assessment may cause

permanent damage if it impedes access to one’s rights and the possibility to exercise them, as well as the

recognition of these rights by others. An incorrectly conducted age assessment can result in children being

placed in vulnerable situations. This could mean that children end up interacting with or being placed among

adults or adults ending up incorrectly placed with children, a scenario which is particularly concerning.

Right to express their views freely and right to be heard (Articles 12 and 14 CRC and Articles 24 and 41 CFR)

This is a fundamental right with far-reaching effects. It encompasses the child’s right to express his or

her own views freely and the right to have his or her views taken into account and given due weight in

accordance with their age and maturity. In cases where the applicant’s age is in doubt, special caution must

be taken to prevent subjective or arbitrary considerations (for example, the age at which a child can form

his or her own views) when taking the views of the child into account according to their level of maturity.

Special consideration should also be given when dealing with persons with disabilities and other special

needs (e.g. illiteracy).

Strictly connected to the right to express their views and the right to effective remedy is the right to be

heard, before any individual measure which would affect him or her adversely is taken in administrative

or judicial proceedings.

Right to information

Information is key in enabling someone to understand the age assessment process as well as the rights

and obligations that the process entails. Furthermore, when consent is required, the person should give

consent based on accurate and comprehensive information and be able to provide it freely without any

kind of pressure or condition.

(

13

) The CFR is available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012P/TXT�

Circumstances of age assessment EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 19

Respect of dignity and right to integrity (Articles 3 and 37 CRC and Articles 1, 3 and 5 CFR)

The age assessment process must respect the applicant’s dignity as well as his or her physical integrity. As

age assessment examinations requiring the exhibition of intimate parts or nudity are highly intrusive and

have no medical purpose, these must be avoided. The exhibition of physical parts is especially traumatic

and difficult to understand for children, adolescents and applicants with different cultural backgrounds.

These examinations are particularly distressing and possibly re-traumatising for children who may have

been exposed to abuse or other risky situations during their migration experience or have had experiences

of persecution or serious harm.

Respect for private life and the protection of personal data (Article

16

CRC and Articles

7 a

nd 8 CFR)

This right protects the private life of children against arbitrary interference by public authorities and private

organisations, such as the media. This protection covers four distinct areas: private life, family life, home

and correspondence. Interference by authorities into personal life needs to be justified, limited to the

maximum extent and ruled by a precise set of norms. Under EU law, personal data can only be gathered

legally under strict conditions, for a legitimate purpose, obtained with the consent of the person or of

his or her representative, or legally justified. Otherwise, this interference becomes arbitrary or unlawful.

Persons or organisations collecting and managing personal information must ensure protection from

misuse and must respect the rights of the data owners guaranteed by EU law. Children and their guardians/

representatives should be informed about the data that is going to be collected under the respective

national legal framework. In the international protection context, caution must be taken when collecting

data to prevent any breach of information that could endanger the applicant or his or her family.

Right to an effective remedy (Articles

12

and 47 CFR)

This right implies that the outcomes of the process can be challenged and that the information and

assistance needed to exercise this right is available to children. Financial costs incurred from challenging

the age assessment decision shall not be borne by the applicant; otherwise the right to effective remedy

would not be effectively exercised.

Most of these fundamental rights are reflected as principles (the BIC) and procedural safeguards by

international and European legislation, in particular in the EU asylum acquis, as shown in the next chapter.

20 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards

Chapter 2 The best interests of the child and

procedural safeguards

The best interests of the child

The principle of the BIC is deeply rooted in the European human rights and asylum legislation and the

international legal framework

(

14

)�

‘In

all actions relating to children, whether taken by public authorities or private institutions, the

ch

ild’s

be

st

interests must be a primary consideration.’ (Article

24

CFR)

The BIC, as an overarching principle, demands continuous consideration from the moment the child is

found until a durable solution is selected for the child.

In the context of international protection any indication that the applicant could be a child should

immediately trigger the consideration of the BIC in all actions affecting him or her and therefore also

throughout the asylum procedure. In this regard, host EU+ states are responsible for observing the BIC

not only in the asylum procedures but also in all other processes and decisions affecting children, such as

in the age assessment process.

As stated by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

(

15

), the BIC is a threefold concept.

(a) A substantive right: the right of the child to have his or her best interests assessed and taken as a

primary consideration when different interests are being considered in order to reach a decision on the

issue at stake, and the guarantee that this right will be implemented whenever a decision is to be made

concerning a child, a group of identified or unidentified children or children in general.

(b) A fundamental, interpretative legal principle: if a legal provision is open to more than one interpretation,

the interpretation which most effectively serves the child’s best interests should be chosen.

(c) A rule of procedure: whenever a decision is to be made that will affect a specific child, an identified

group of children or children in general, the decision-making process must include an evaluation of the

possible impact (positive or negative) of the decision on the child or children concerned.

Assessing and determining the BIC requires procedural guarantees. Furthermore, the justification of a

decision must show that the BIC have been explicitly taken into account. In this regard, authorities shall

explain how the right has been respected in the decision, i.e. what has been considered to be in the child’s

best interests; what criteria it has been based on; and how the child’s interests have been weighed against

other considerations, be they broad issues of policy or individual cases.

Consequently and in compliance with the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s general comment,

the decision to undertake age assessment and the methods selected in order to assess age should also be

subject to primary consideration of the BIC.

(

14

) Article 3 CRC, Article 24 CFR; EU asylum acquis: Article 23 RCD recast, Article 11 RCD recast, Article 25.6 APD recast, Article 20.5 QD and Article 6 Dublin III

regulation recast.

(

15

) General Comment No 14 (2013) on the right of the child to have his or her best interests taken as a primary consideration (Article 3, para. 1), available

at: http://www2.ohchr.org/English/bodies/crc/docs/GC/CRC_C_GC_14_ENG.pdf�

The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 21

Assessing the best interests of the child for the purpose of the age assessment

A BIA verifies that the age assessment process serves the child’s best interests, that the necessary procedural

safeguards are in place, that the rights of the individual child are protected and that the results are expected

to dispel the doubts on the age of the applicant. The BIA should consider the specific circumstances of the

child as well as ensure that the BIC are given primary consideration when deciding whether to have his or

her age assessed and how. For this reason, the age assessment process must be child-centred, taking into

consideration the specific circumstances and needs of the applicant.

In light of this, the BIA should be conducted prior to any decision affecting the child being taken, therefore

before deciding to conduct the age assessment process.

In case further actions are needed, the BIA will require a follow-up to ensure that the best interests are

considered. The decision on undertaking an age assessment should consider the outcome of the BIA

interview and all the information in the child’s file. If the age assessment is not deemed necessary and

useful considering the expected results, it should not be undertaken�

Furthermore, the following factors are of particular importance when considering the BIC for the specific

purpose of age assessment in the context of international protection.

• Security and safety considerations (

16

): upon arrival or at a later stage, children sometimes claim to be

adults in order to avoid the accommodation for children. Such accommodation has more protective

measures such as limitations on the freedom of movement and allocated staff to take care of them.

This may be due to a number of different reasons, for example the wish to remain undetected in

order to continue moving to the intended destination. On other occasions, this alleged adulthood

may be part of the background story that they have been instructed to tell the authorities or other

actors when asked about their age. The sources of these background stories can be quite diverse.

They could be instructed by relatives or accompanying adults who want to prevent separation, or

by smugglers; however, it could also come from a member of the trafficking network who wants to

keep control over and have easy access to the child during his or her stay in the territory. Therefore

it is very important to keep in mind that a doubtful claim of adulthood may be an indicator that the

applicant is a potential victim of THB, and authorities should act accordingly (signposting and referring

to relevant national services, including possible assessment as a victim of THB).

• Child’s well-being (

17

): if the age assessment is justified, the methods used must be the least intrusive

for the child, the most accurate to assess the range of age, transparent and defined in accordance with

validated standards, as well as be auditable and reviewable. In order to ensure that the expectations of

the results of the methods are realistic, the margin of error must be identified and documented. The

doubts and concerns of the child must be attended to and any reasons for a refusal to undergo the

assessment must be explored and alternatives provided, if available. Requests of the child or of his or

her guardian/representative must be attended to to the maximum extent possible in order to preserve

the well-being of the child and to reduce the distress of the examinations (limiting the number of

people in the examination or interview room, with the presence of the guardian/representative if

the child so requires, etc.).

•

Ch

ild’s background

(

18

): it is important to adapt the process to the child’s cultural background

(preferred gender of the examiner and interpreter) as well as to their experiences (the flight and the

migration to Europe that the child has gone through could cause or exacerbate their vulnerability).

• Specific circumstances: authorities shall weigh the applicant’s specific circumstances (range of

disputed age, the gender of the applicant, etc.) and needs, the potential positive and negative effects,

the views of the applicant, and if the particular methods in use are appropriate for the case.

(

16

) Article 23(2) RCD, Article 6 and recital 13 Dublin III regulation and recital 18 QD.

(

17

) As stated in Article 23(2) RCD, Article 6 Dublin III regulation and recitals 18 QD, 33 APD, 13 Dublin III and 20 APR.

(

18

) Article 23(2) RCD and recitals 33 APD, 13 Dublin III and 18 QD.

22 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards

As a reflection of the above, both international and European legal frameworks identify the following

standards and safeguards necessary for age assessment.

The benefit of the doubt shall be applied as broadly as possible in the case of unaccompanied children,

who are less likely to have documentary evidence.

Immediate access to a qualified, independent representative and/or guardian, who acts in the child’s

best interests, safeguards the general well-being and exercises the legal capacity.

The right to receive age-appropriate information in a language that he or she understands.

The right to participate and to have his or her views heard and considered according to his or her age

and maturity.

Informed consent and the right to refuse medical examinations.

Confidentiality, data protection and safety considerations

�

Ch

ild-friendly procedures conducted by qualified professionals who are aware of the cultural and ethnic

particularities.

Least intrusive method, least intrusive process (gradual implementation), gender- and culturally appropiate.

Accuracy and margin of error to be applied in the applicant’s favour.

Right to effective remedy as may be applicable.

When the process and the available resources do not guarantee the cited safeguards, as might occur in

situations of a large influx or disembarkation, the age assessment might be conducted at a later stage

or in two stages (with a preliminary screening upon arrival and a fully fledged age assessment once the

conditions allow it). In this scenario, benefit of the doubt is fully applicable and the claimed age must be

accepted until the conditions ensure that a safe and efficient age assessment can be conducted

(

19

)�

It s

hould be noted that while the guidance and tools provided in this publication only focus on the age

assessment process, the BIA is to be continued until a durable solution is found for the child. Furthermore,

the BIA does not intend to replace a best interests determination (BID), which is required when durable

solutions for the child are under consideration.

Applying the principle of the benet of the doubt

The benefit of the doubt is a key principle and safeguard in the field of age assessment since none of the

current methods of age assessment are able to determine a specific age with certainty.

Owing to the importance of this principle, benefit of the doubt repeatedly appears as a key procedural

safeguard in matters related to children, and also in the age assessment process in the EU asylum acquis

(Article 25(5) APD recast). Furthermore, the anti-trafficking directive (ATD) (

20

) clearly states that benefit

of the doubt should be applied when the age is uncertain, as follows.

(

19

) Further guidance and practical recommendations can be found in Chapter 4 and Annex 2 (the BIC tools).

(

20

) Directive 2011/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and

protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA, available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:

2011:101:0001:0011:EN:PDF�

The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 23

‘Member States shall ensure that, where the age of a person subject to trafficking in human beings is

uncertain and there are reasons to believe that the person is a child, that person is presumed to be a child

in order to receive immediate access to assistance, support and protection.’ (Article

13.

2

AT

D)

The issue becomes more complicated, since doubts about the age of an applicant are often a consequence

of a lack of documentary evidence. This is particularly common in the case of children. However, the age

assessment process might not dispel all doubts (results are often about 1 or 2 years below or above 18 years

old) due to the limitations of the current methods.

Age assessment should not be a routine practice. The need for age assessment should be duly justified based

on the substantiated doubts on the stated age, resorted to only in cases where there is an absence of evidence

and/or in cases where several elements of evidence gathered contradict the applicant’s claimed age. If the

available evidence does not contradict the age or it confirms the claimed age, then it should be accepted.

In cases where there is a lack of documentary evidence (such as passports, ID documents, residence

cards or travel documents such as those issued by the UNHCR, other countries’ certificates or religious or

civil certificates, probing the civil status — marriage, births, family booklet of the applicant or any family

member — with any reference to the age of the applicant), authorities may be uncertain or have simple

doubts about the age of the person.

In other cases, when documentation is missing and the claimed age is not supported or is contradicted

by several elements of evidence gathered by the authorities, doubts are considered to be substantiated

�

W

here harmful consequences may result from an incorrect consideration of the person as an adult or child,

the initiation of age assessment should be deemed necessary provided it is in the BIC.

Simple doubts

In case of a lack of valid documentation, if the claimed age (statements of the applicant) is supported

or confirmed by at least one of the following elements of evidence gathered by the authorities, then

the claimed age can be accepted without the need for age assessment.

▪

Information from other databases.

▪

Statements from other family members, relatives or the child’s guardian.

▪

First estimations of physical appearance.

The elements may be weighted differently according to the reliability of the specific element in

comparison to the others.

Substantiated doubts

In case of a lack of valid documentation, when the claimed age (statements of the applicant) is not

supported or is contradicted by several elements of evidence gathered by the authorities, then the

claimed age cannot be accepted and there will be a need for an age assessment.

▪

Information from other databases.

▪

Statements from other family members, relatives or the child’s guardian.

▪

First estimations of physical appearance (to be considered only in conjunction with the

previous elements, not only on its own).

The elements may be weighted differently according to the reliability of the specific element in

comparison to the others.

After the analysis of the previous elements, authorities may have substantiated doubts on the claimed

age, thus an age assessment process might be needed to estimate the age of the applicant.

24 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards

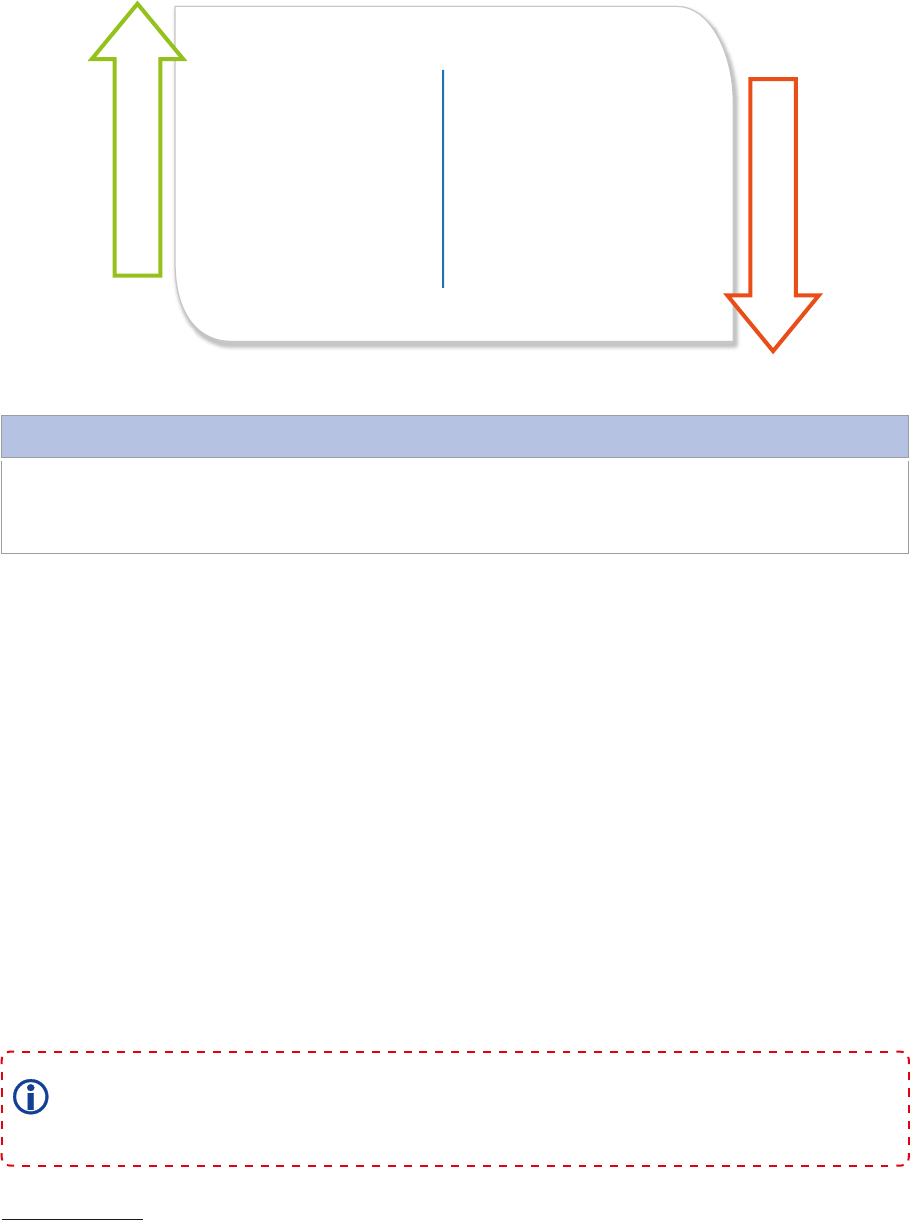

The age of the applicant as a material fact

In some particular cases, such as in the case of child-specific grounds for international protection (forced

marriage, child soldiers, etc.), the age of the applicant constitutes a material fact

(

21

) and is thus relevant

to the examination of the application for international protection. In these cases, even if the applicant’s

statements on age are not supported by documentary or other evidence, the statements will be found

credible and accepted without the need for further (age) assessment if the following conditions are met

(as established in Article

4.

5 QD).

Required conditions to find the applicant’s statements credible even if not supported by evidence

Genuine effort

to substanate

the applicaon

Relevant and

available

elements have

been submied

and a

sasfactory

explanaon

has been given

regarding the

missing elements

Coherent and

pausible

statements

The applicant

has applied as

soon as

possible for

internaonal

protecon

For e.g. physical

appearance

and

psychological

maturity are

consistent

with the

claimed age,

the informaon

is consistent

with COI, etc.

or good

jusficaon

has been

given

otherwise

Generally

credible

This is a particularly important provision for unaccompanied children who may be less likely to have

documentary evidence, and especially so in cases of applicants for international protection.

The information should be assessed by asylum or migration officials and should take into account the

individual and contextual situation of the applicant. In the case of children or presumed children, and

especially when unaccompanied, the level of expectations regarding available evidence and consistency

in explanations should be lower.

The benet of the doubt throughout the age assessment process

Due to the inaccuracy and potential intrusiveness of the current methodologies in use, the systematic

application of benefit of the doubt throughout the whole age assessment process is crucial. It is necessary to

acknowledge and establish the margin of error of the current methods within the process, and its influence

on the results. These shortcomings should not be detrimental to the applicant’s rights or statements; on the

contrary, a proper implementation of benefit of the doubt should lead authorities to interpret inconclusive

results in the applicant’s favour, in dubio pro refugio or in dubio pro minore�

‘Member States may use medical examinations to determine the age of unaccompanied minors within

the framework of the examination of an application for international protection where, following general

statements or other relevant indications, Member States have doubts concerning the applicant’s age. If,

thereafter, Member States are still in doubt concerning the applicant’s age, they shall assume that the

applicant is a minor.’ (Article 25.5 APD)

(

21

) As defined in the EASO practical guide: evidence assessment module, material facts are (alleged) facts that are linked to one or more of the requisites of

the definition of a refugee or person eligible for subsidiary protection.

The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 25

An ultimate benefit of the application of this principle to the identification phase for children is that this

principle provides an immediate answer to any doubts and does not require a costly or lengthy process

to achieve it. Additionally, it might and should be applied before and at any stage of the assessment

where any doubts are raised by the experts involved in the process (the experts conducting the age

assessment or when interpreting the results). This is especially relevant in situations of high influx

where authorities have to make rapid decisions and resources are overstretched. Nevertheless, while

facing the possibility of dealing with a child, he or she must not be considered as an adult and must

therefore not be placed in adult accommodation or in detention facilities, either before or during

the assessment

�

Th

e applicant shall be considered and treated as a child throughout these steps:

Practical implementation of the principle of the benefit of the doubt

Lack of

documentaon but

other informaon is

consistent with the

claimed age

During age

assessment

At any stage

of the process

Aer age

assessment

• Simple doubts,

so no need for

age assessment

• Whilst doubts

remain

• When any of the

results of the age

assessment

indicate

childhood

• Inconclusive

results: always

taking the lowest

age of the range

The benefit of the doubt is therefore applicable in the following cases:

When the claimed age (statements of the applicant) is not supported by documentation but is consistent

with other elements of evidence gathered by the authorities, benefit of the doubt directly applies, meaning

that there would not be any need for age assessment.

• In cases where age assessment is undertaken, the individual should be afforded benefit of the doubt

and treated as a child for the duration of the process and for as long as any doubt remains�

• If

any of the methods applied during age assessment obtain a result indicating childhood, the

assessment shall stop there and the lowest age of the range is to be taken as valid.

• Finally, if after the process has ended the results are still inconclusive, age assessment shall consider

the lowest age of the range as valid

(

22

)�

(

22

) See Article 25.5 APD recast and the UN committee’s General Comment No 6.

26 EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards

Key ndings from EU+ states’ pracce

The applicant is considered a child during age assessment in 17 EU+ states.

One Member State applies a margin of error of 2

ye

ars in the applicant’s favour once the results are

received.

Two EU+ states do not apply benet of the doubt.

Further informaon can be found in Annex 4 to this publicaon.

Guardian/representave

As a key safeguard for unaccompanied children, the presumed child should be appointed an independent

and qualified guardian/representative as soon as possible (see Article

25(

1) APD).

A representative is a person or an organisation appointed by competent bodies in order to assist and

represent an unaccompanied child in procedures. The representative ensures the BIC and exercises legal

capacity for the child where necessary

(

23

). The representative should be appointed as soon as possible

and before the commencement of any age assessment examination. In addition, the representative must

be independent in order to avoid any conflict of interests, thus ensuring that he or she acts in the BIC

as established in Articles

24

(1) and 25(1)(a) APD recast as well as in Article

24

RCD recast. Where, for

practical reasons, a permanent guardian cannot be assigned swiftly to a child, provisions should be made

for the appointment of a person who temporarily carries out the guardian’s tasks. In such cases, temporary

guardians must have the same conditions (qualifications and independency) as non-temporary guardians.

The representative should be informed and consulted about all the aspects of the age assessment process

and should be able to accompany the child during the examinations, if the child so wishes. When age

assessment is considered to be in the child’s best interests, yet the child does not agree to it, the guardian/

representative could potentially still give consent to the assessment. However, this needs to be well

communicated between the child and their representative in order not to jeopardise the relationship of

trust between them.

The guardian/representative should also be present in the BIA interview, if possible. The child’s legal

counsel, if available, should also be contacted and given the opportunity to attend the BIA interview

(

24

)�

The process should continue with the presence of the guardian/representative, unless the child requests

otherwise. Either way, the guardian/representative should closely follow the process in order to be able

to advise the applicant when needed.

Key ndings from EU+ states’ pracce

The presence of an independent person to support the applicant during the examinaons is allowed in

23 EU+ states. In 12 of them, this role is exercised by the guardian or representave.

One EU+ state only allows this independent person for Dublin cases.

One EU+ state allows the presence of a supporve person during forensic examinaon.

One EU+ state does not allow it.

Further informaon can be found in Annex

4 t

o this publicaon.

(

23

) Article 2(n) APD.

(

24

) For that purpose, the BIA checklist included in Annex 2 can be of use.

The best interests of the child and procedural safeguards EASO praccal guide on age assessment: Second edion 27

Additional guidance regarding the role of the guardian in the age assessment process may be found in

the FRA Guardianship for children deprived of parental care handbook

(

25

), which contains the following.

Possible actions by the guardian in relation to age assessment:

▪

check that there is legitimate reason for the age assessment and request that children who are

clearly underage not be subjected to such assessment;

▪

ensure that the child receives all relevant information about the age assessment procedure,

including clear information about its purpose and the process and possible consequences — the

information should be provided in a child-friendly manner and in a language the child understands;

▪

ensure that the age assessment is conducted with the informed consent of the child and of their

guardian;

▪

check that independent professionals with appropriate expertise who are familiar with the child’s

ethnic and cultural background undertake the age assessment and conduct it in a safe, child- and

gender-sensitive manner with due respect for the child’s dignity;

▪

if doubt remains about the child’s age after the age assessment is completed, insist that a person

be considered a child;

▪

ensure that the outcome of the procedure is explained to the child in a child-friendly manner and

in a language he or she understands.

▪

request that the results of the assessment procedure be shared with the guardian and include these

in the child’s file;

▪

review with the child the possibility of an appeal against the age assessment decision, in accordance

with national legislation;

▪

with the child’s agreement, be present during the age assessment procedure.

Examples from pracce

DK — In cases of unaccompanied children, delays in the appointment of the guardian may derive from age

disputes. This can occur when it is necessary to complete age assessment procedures before a guardian

is appointed. To overcome this delay, the Danish Red Cross is the designated organisation to appoint an

observer, called ‘bisidder’.

UK — The Scottish Guardianship Service (set up on a non-statutory basis) works with children and young

people who arrive in Scotland unaccompanied and separated from their families. It supports and works

with young people under 18 years of age who are seeking asylum or have been trafficked from outside

the EU. It also works with anyone who is being treated as a child under 18 but whose age is disputed and is

undergoing age assessment. Children and young people are allocated a guardian to help them understand,