Guidebook 'How to develop a

Sustainable Energy and Climate

Action Plan (SECAP)'

Part 1 - The SECAP

process, step-by-step

towards low carbon and

climate resilient cities

by 2030

Bertoldi, P. (editor)

Full list of authors in the

acknowledgements

2018

EUR 29412 EN

This publication is a Science for Policy report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s

science and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European

policymaking process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European

Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is

responsible for the use that might be made of this publication.

Contact information

Name: Paolo Bertoldi (Editor)

Address: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Via Enrico Fermi 2749 - 21027 Ispra (VA), Italy

Email: [email protected]ropa.eu

Tel.: +39 0332789299

EU Science Hub

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc

JRC112986

EUR 29412 EN

PDF

ISBN 978-92-79-96847-1

ISSN 1831-9424

doi:10.2760/223399

Print

ISBN 978-92-79-96848-8

ISSN 1018-5593

doi:10.2760/68327

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018

© European Union, 2018

The reuse policy of the European Commission is implemented by Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12

December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Reuse is authorised,

provided the source of the document is acknowledged and its original meaning or message is not distorted. The

European Commission shall not be liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse. For any use or

reproduction of photos or other material that is not owned by the EU, permission must be sought directly from

the copyright holders.

All content © European Union 2018

How to cite this report: Bertoldi P. (editor), Guidebook 'How to develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate

Action Plan (SECAP) – Part 1 - The SECAP process, step-by-step towards low carbon and climate resilient cities

by 2030, EUR 29412 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018, ISBN 978-92-79-

96847-1, doi:10.2760/223399, JRC112986

i

Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................... 1

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 2

Executive summary ............................................................................................... 3

1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 6

1.1 Policy context .............................................................................................. 6

1.2 About the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy in Europe ....................... 7

1.3 About the Global Covenant of Mayors ........................................................... 10

1.4 About this Guidebook ................................................................................. 11

2 The Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan – a way to go beyond the European

Union targets ...................................................................................................... 13

2.1 Scope of the SECAP ................................................................................... 13

2.2 Time horizon ............................................................................................. 14

2.3 The SECAP process .................................................................................... 16

2.4 Human and financial resources .................................................................... 18

2.5 Joint SECAPs ............................................................................................. 18

2.6 SECAP document, template and submission procedure ................................... 19

2.6.1 Recommended SECAP structure ........................................................... 21

2.7 Key elements of a successful SECAP ............................................................. 24

2.8 Ten key elements to keep in mind when preparing a SECAP ............................ 25

3 Political commitment ........................................................................................ 29

4 Mobilization of all municipal departments involved

() ............................................ 31

4.1 How to adjust administrative structures ........................................................ 31

4.2 Examples from Covenant signatories ............................................................ 33

4.3 External support: Covenant Territorial Coordinators and Local and Regional Energy

Agencies ......................................................................................................... 34

5 Building support from stakeholders .................................................................... 37

5.1 Who are stakeholders? ............................................................................... 37

5.2 How to engage in stakeholder participation ................................................... 41

5.3 Communication ......................................................................................... 44

6 Assessment of the current framework: where are we? .......................................... 46

6.1 Analysis of relevant regulations ................................................................... 46

6.2 Baseline review: Baseline Emission Inventory and Climate Change Risk and

Vulnerability Assessment .................................................................................. 46

6.2.1 Baseline Emission Inventory (BEI) ....................................................... 46

6.2.2 Risk and Vulnerability Assessment ....................................................... 47

6.3 SWOT analysis .......................................................................................... 48

7 Establishment of a long-term vision with clear objectives...................................... 50

ii

7.1 The vision: towards a sustainable future ....................................................... 50

7.2 Setting objectives and targets ..................................................................... 52

8 SECAP elaboration ........................................................................................... 54

9 SECAP implementation ..................................................................................... 58

10 Monitoring and reporting progress ..................................................................... 59

11 Conclusions .................................................................................................... 61

Annex 1. Example of aspects suggested to be covered in the baseline mitigation

reviews 62

Annex 2. Benefits of SECAP ................................................................................ 65

Annex 3. Glossary ............................................................................................. 66

List of abbreviations and definitions ....................................................................... 71

List of Boxes ....................................................................................................... 72

List of Figures ..................................................................................................... 73

List of Tables ...................................................................................................... 74

1

Abstract

The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (CoM) is an ambitious initiative for local

climate and energy actions. This document provides signatories with a set of

methodological principle, procedures and best practices to develop their SECAP. The Part

1 of this document relates to the SECAP process; while Part 2 gives an insight on the

elaboration of municipality assessments (BEI and RVA), finally Part 3 describes technical

issues, measures and policies that can be implemented at local level.

2

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the European Commission Directorate-General for

Energy (DG ENER), colleagues Eero Ailio, Sebastien Occhipenti, John Stuebler, Joanna

Ziecina; the European Commission Directorate-General for Climate Action (DG CLIMA),

colleagues Sandro Nieto Silleras, Dina Silina, Christopher Ahlgren Anders, Alessandra

Sgobbi, for their work and support in giving visibility and effectiveness to the efforts of

cities and local authorities in the CoM initiative. Special thanks to the European

Commission's Joint Research Centre's colleagues including Laura Rappucci for the editing.

Relevant contribution on reviewing this guidebook have also been received from the

Covenant of Mayors Office (CoMO), colleagues including Lucie Blondel, Alessandra

Antonini, Giustino Piccolo, Lea Kleinenkuhnen, Frédéric Boyer, Miguel Morcillo, and

experts form municipalities, regions, agencies and private companies.

Special thanks to local authorities who make public their engagement in climate action

planning through their participation in the Covenant of Mayors.

Authors

Rivas Silvia, Melica Giulia, Palermo Valentina, Dallemand Jean-François (JRC).

3

Executive summary

The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (CoM) is the mainstream European

voluntary movement involving local authorities in the development and implementation

of sustainable energy and climate policies.

Policy context

The European Union is leading the global fight against climate change, and has made it

one of its top priorities. Local authorities have a key role in the climate change challenge.

Over half of greenhouse gas emissions are created in and by cities. 80% of the

population lives and works in cities, where up to 80% of energy is consumed. In addition,

cities are vulnerable to and face growing difficulties in dealing with the effects of climate

change. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events sends a clear signal that

cities and towns must become resilient to the impacts of climate change.

Local authorities play a key role in the achievement of the EU's energy and climate

objectives and are leading actors for implementing local sustainable energy policies.

The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy is intended to complement the national

Climate Change strategies and plans with a specific initiative to support cities. The

initiative aims to convene local authorities voluntary committing to implement

sustainability policies on their territories. Harmonised data compilation, methodological

and reporting framework to translate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction

ambitions into reality are provided to local authorities. CoM includes both climate

mitigation and adaptation aspects and is built around three pillars:

— Mitigation (at least 40% emission reduction target by 2030compared to the baseline)

— Adaptation to Climate Change

— Access to secure, sustainable and affordable energy

Signatory local authorities share a vision for making cities decarbonised and resilient,

where citizens have access to secure, sustainable and affordable energy.

The formal commitment of signatories is translated into concrete measures and projects

by the implementation of a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP). The

SECAP includes the key actions local authorities intend to undertake. The SECAP is based

on the outcomes of the Baseline Emission Inventory – BEI and the Risks and

Vulnerabilities Assessment- RVA on the territory. Signatory cities accept to report and

monitor their implementation of the SECAPs. Cities also commit to allocating sufficient

human resources to the tasks, mobilising society in their geographical areas to take part

in implementation of the action plan, including organisation of local energy days, and

networking with other cities. Moreover, joining the initiative brings several co-benefits:

creating a sustainable environment for citizens and local assets, overall improving of the

quality of life, consolidating the success of measures to reduce CO2 emissions in their

territory, benefitting from the European support, recognition and the best practices.

Main findings

The Covenant of Mayors was launched in 2008 in Europe with the ambition to gather

local governments voluntarily committed to achieving and exceeding the EU climate and

energy targets. The initiative has been growing gathering more than 7,000 local and

regional authorities across 57 countries. In 2016 the 5,403 CoM signatories overall

commitment for 2020 was a reduction of the total GHG emissions of 27%, 7 percentage

point above the minimum requested target of 20 %. Results from the plans monitoring

reported, reveal an already achieved 23% overall reduction in emissions.

Related and future JRC work

The success of the Covenant of Mayors in Europe has attracted more and more

signatories from cities in other parts of the world. To support the international dimension

4

of CoM, the European Commission has launched a number of initiatives to support the

Covenant of Mayors in the Eastern Partnership countries, in the Central Asian countries,

in the South neighbouring countries of Europe and later to sub-Saharan African

countries. In January 2017, the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy was

announced. This is an international alliance of cities and local governments with a shared

long-term vision of promoting and supporting voluntary action to combat Climate Change

and move to a low-emission resilient society. This coalition already represents about 11%

of the world’s population as of May 2018, and 7,755 towns and cities, have joined it

through the Covenant of Mayors framework, while 428 global cities joined via the

Compact of Mayors.

Quick guide

This Guidebook aims at supporting local authorities in the European Union (EU) Member

States joining the Covenant of Mayors for Energy and Climate (2030 target). The present

guidebook provides detailed, step-by-step guidance to local authorities to develop an

effective SECAP, in particular:

— Define the key elements of the initiative

— Elaborate a Baseline Emission inventory (BEI)

— Perform a Risk and Vulnerabilities Assessment (RVA)

— Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP)

— Support the implementation and monitoring of the SECAP.

Step-by-step recommendations are provided for the entire process of elaborating a local

energy and climate strategy, from initial political commitment to implementation and

monitoring of the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan. The guidebook is providing

a set of flexible but coherent principles and recommendations, allowing both local

authority front runners and newcomers to take local level climate action through the

CoM, while considering site specific circumstances and capabilities.

The Guidebook is divided into three Parts:

Part 1: Relates to the overall SECAP process, from the initiation to the monitoring phase.

This part includes: detailed description of the SECAP requirements, options, timelines and

template, the benefits local authorities can obtain when supporting SEAP implementation,

an overview of the role of the key actors involved and suggestions on how to organise

the administrative structures.

Part 2: Relates to municipality assessments, as pre-requisite to the SECAP development.

These provide knowledge on the nature of the emitting entities, risk and vulnerabilities in

the municipality territory. In particular:

Part 2.a focuses on how to elaborate the Baseline Emission Inventory (BEI) and the

Monitoring Emission Inventory (MEI), while

Part 2.b: focuses on how to perform a Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (RVA).

Part 3: Relates to the description of technical issues, measures, policies and financial

mechanisms with examples of good practice that can be implemented at local level by

the local authority per sector of activity. In particular:

Part 3.a: Focuses on Climate Change mitigation,

Part 3.b: Focuses on Climate Change adaptation, and

Part 3.c: Focuses on financing mechanisms for SECAPs.

The number of topics covered by this guidebook is quite large; hence, a number of these

has not been approached thoroughly. However, links to further readings and detailed

information are provided through the text.

The Guidebook has been prepared by the Joint Research Centre Directorate-General

(JRC) of the European Commission, with the support and input of the Directorate-General

for Energy (DG ENER), Directorate-General for Climate Action (DG CLIMA), the Covenant

5

of Mayors Office (CoMO) and experts form municipalities, regions agencies and private

companies.

6

1 Introduction

1.1 Policy context

Climate Change mitigation

Tackling Climate Change is a priority for the European Union who has set targets for

reducing greenhouse gas emissions progressively up to 2050. The Key climate and

energy targets are set in two progressive documents: the "2020 climate and energy

package" included in the "Europe 2020 Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive

growth" and the "2030 Climate and Energy Framework", defined to put the EU on the

way to achieve the transformation towards a low-carbon economy as detailed in the 2050

low-carbon roadmap (

1

). The former, enacted in legislation in 2009, aimed at reducing by

20% greenhouse gas emissions (from 1990 levels), at improving energy efficiency and at

increasing the share of energy from renewables to 20% by 2020. The latter

proposes new targets and measures forwarding the commitments beyond 2020 and it

builds on the 2020 Climate and Energy Package. The "2030 Climate and Energy

Framework" shows an ambitious commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in line

with the 2050 Roadmaps and sets three key targets for the year 2030: at least 40% cuts

in greenhouse gas emissions (from 1990 levels), at least 27% share for renewable

energy and at least 27% improvement in energy efficiency. This framework was adopted

by EU leaders in October 2014 and it is also in line with the longer term perspective set

out in the Roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050, "The

Energy Roadmap 2050". This explores the transition of the energy system in ways that

would be compatible with the 80% domestic greenhouse gas reductions target while also

increasing competitiveness and security of supply. The roadmap requires the reach of the

target of cutting of 40% GHG in comparison to 1990 levels by 2030 already endorsed as

a milestone as part of the "2030 Framework". Moreover, the implementation of the "2030

Energy and Climate Framework" is a priority in follow up to the Paris Agreement, the first

multilateral agreement on Climate Change covering almost the global emissions, which

vindicates the EU's approach. The international climate agreement aims to keep global

warming below 2°C, in accordance with the recommendations of the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

(

2

). The key features of the Paris Agreement include:

GHG reduction with a long-term goal of keeping the increase in global average

temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and limit the increase to

1.5°C; a dynamic and transparent mechanism to take stock of ambition over time, an

ambitious solidarity package with adequate provisions on climate finance. Moreover, the

agreement promotes individual and collective action on adaptation, with the aim to

enhance climate resilience and reduce climate vulnerability. It also recognises the role

of non-Party stakeholders in addressing Climate Change, including cities, other

subnational authorities, civil society, the private sector and others who are invited to

scale up their efforts and support actions to reduce emissions, build resilience and

decrease vulnerability to the adverse effects of Climate Change (

1

,

2

).

Climate change Adaptation

Adaptation means anticipating the adverse effects of climate change and taking

appropriate action to prevent or minimise the damage they can cause, or taking

advantage of opportunities that may arise. It has been shown that well planned, early

adaptation action saves money and lives later.

Adaptation strategies are needed at all levels of administration: at the local, regional,

national, EU and also the international level. Due to the varying severity and nature of

(

1

) https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies_en Accessed in May 2018

(

2

) EUROPEAN COMMISSION, COM(2016) 110 final, Communication from the Commission to the European

Parliament and the Council "The Road from Paris: assessing the implications of the Paris Agreement and

accompanying the proposal for a Council decision on the signing, on behalf of the European Union, of the Paris

agreement adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change", Brussels, 2.3.2016

7

climate impacts between regions in Europe, most adaptation initiatives will be taken at

the regional or local levels. The ability to cope and adapt also differs across populations,

economic sectors and regions within Europe (

3

).

In April 2013 the European Commission adopted a European Union (EU) strategy on

adaptation to Climate Change (

4

). This strategy aims at making Europe more resilient to

Climate Change. The strategy is meant to enhance adaptive capacity of all governance

levels to deal with the impacts of Climate Change. The EU Adaptation Strategy pursues

three main objectives:

1) promote action by Member States (MS) by means of adopting comprehensive

adaptation strategies and provide funding to help MS build up their adaptation

capacities and take action;

2) promote adaptation in relevant vulnerable sectors such as agriculture, fisheries

and cohesion policy, guaranteeing that Europe's infrastructure is made more

resilient, and promote the use of insurance against natural and man-made

disasters;

3) promote better informed decision-making by addressing gaps in knowledge about

Climate Change adaptation and further developing the European climate

adaptation platform (Climate-ADAPT) as the 'one-stop shop' for adaptation

information in Europe.

The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy falls under the first key objective and

includes both climate mitigation and adaptation aspects, and is intended to complement

the national Climate Change strategies and plans with a specific initiative to support

cities. The climate adaptation pillar of the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy is

the follow up of the Mayors Adapt initiative, a voluntary commitment that has been set

up by the European Commission to engage cities in taking action to adapt to Climate

Change. Cities signing up to the initiative commit to contributing to the overall aim of the

EU Adaptation Strategy by developing a comprehensive local adaptation strategy or

integrating adaptation to Climate Change into relevant existing plans. They agree to

submit an adaptation strategy within two years of signing the commitment and report

every second year on their city's achievements. By joining the initiative, participating

local authorities will benefit from support for local activities to tackle Climate Change, a

platform for cooperation and exchange of best practice, and greater public awareness

about adaptation and the measures that need to be taken.

In 2016, the Commission launched an evaluation of the EU Adaptation Strategy to

examine the actual implementation and performance of the strategy. The evaluation is

planned to be completed by the end of 2018.

1.2 About the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy in

Europe

Covenant of Mayors (2020 target)

The Covenant of Mayors (CoM) "2020 target" initiative was launched in 2008 by the

European Commission after the adoption of the 2007 EU Climate and Energy Package, to

endorse and support the efforts deployed by local authorities in the implementation of

sustainable energy policies towards a low carbon future. The initiative aimed to convene

local and regional authorities voluntary committing to implement sustainability policies on

their territories and to provide them with harmonised data compilation, methodological

and reporting framework, to translate their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction

ambitions into reality.

(

3

) https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/adaptation_en

(

4

) https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/docs/eu_strategy_en.pdf

8

The CoM (2020 target) local authorities' commitment was to achieve and exceed by 2020

at least the European 20% reduction of the total emissions objective compared to the

baseline, in the area of influence of the local authority, by the implementation of a

Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP). The SEAP includes energy related actions tackling

the largest emitting activity sectors in the city towards an increasing of energy efficiency

and the use of renewable energy sources (RES). The SEAP is based on the results coming

from an initial emissions evaluation (Baseline Emission Inventory – BEI) on the territory

and an adaptation of city structures. Mobilisation of civil society is needed in order to

ensure an effective implementation of the SEAP. In 2010, the Joint Research Centre

(JRC) published the first Covenant of Mayors Guidebook (

5

) guiding the local authorities

joining the initiative in the BEI calculation and in the development, implementation and

monitoring of their SEAPs.

In parallel, in 2014, in the context of the European Commission’s European Strategy on

adaptation to Climate Change (

6

), the European Commission launched a separate

initiative called Mayors Adapt, based on the same principles as the Covenant of Mayors.

This sister initiative focusing on adaptation to Climate Change invited local authorities to

demonstrate leadership in adaptation, and was supporting them in the development and

implementation of local adaptation strategies.

Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy ("2030 targets")

In October 2015, the Covenant of Mayors and Mayors Adapt initiatives were officially

merged. The Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (2030 targets) was launched

stepping up the initial greenhouse gas emission reduction commitments and integrating

adaptation to Climate Change. The initiative is built around three pillars:

Mitigation (at least 40% emission reduction target by 2030)

Adaptation to Climate Change

Secure, sustainable and affordable energy

Signatory local authorities share a vision for making cities decarbonised and resilient,

where citizens have access to secure, sustainable and affordable energy. To translate

commitments into action, they commit to (Figure 1):

— Setting ambitious mitigation and adaptation goal(s) / target(s);

— Measuring their GHG emission level in a base year, according to a common

methodological approach; Baseline Emission Inventory (BEI)

— Assessing climate risks and vulnerabilities within their cities; Risk and Vulnerability

Assessments (RVAs)

— Defining a comprehensive set of actions that local authorities plan to undertake in

order to reach their climate mitigation and adaptation goals; Sustainable Energy and

Climate Action Plan (SECAP). The plan will be based on the results coming from the

previous assessments (BEI and RVAs)

— Approving and making their action plan publicly available;

— Regularly reporting (both qualitatively and quantitatively) to the EC on the

implementation of their action plan

— Sharing their vision, results, experience and know-how with fellow local and regional

authorities within the EU and beyond through direct cooperation and peer-to-peer

exchange.

(

5

) "How to develop a Sustainable Energy Action Plan" Bertoldi P et al. 2010

(

6

) COM/2013/216

9

With these commitments and actions, local authorities are contributing significantly to

the implementation of the EU 2030 Climate and Energy package (

7

) and of the EU

Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change (

8

). As stated before, the role of sub-national

level actors is becoming increasingly important as we strive to implement the Paris

Agreement and keep global warming well below 2°C.

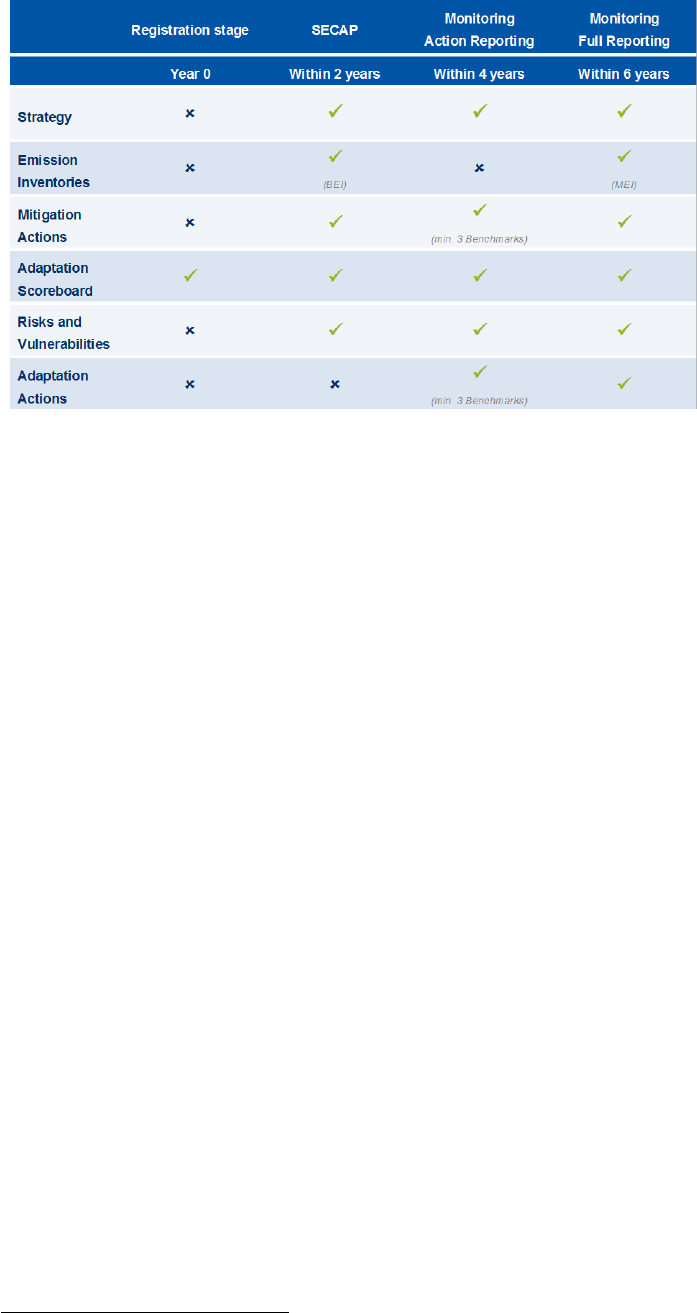

Figure 1. Overview table, showing the differences in terms of commitments and reporting

requirements for the different (past/current) versions of the Covenant initiatives

Source: CoMO

About the European Covenant of Mayors Methodological & Reporting

Frameworks

The Covenant of Mayors helps local authorities to translate their commitments into

reality, while taking into account the immense diversity on the ground. It provides

signatories with a set of methodological principles (defined in the present Guidebook)

and a harmonised data compilation and reporting framework (consisting of a reporting

template (

9

), and complemented by comprehensive reporting guidelines (

10

)) which are

unique in Europe. These reference documents have been developed by the Joint

Research Centre of the European Commission and the Covenant of Mayors Office - in

collaboration with a group of practitioners from local and regional authorities.

Main achievements

In 2016 (

11

,

12

) the 5 403 CoM signatories overall commitment for 2020 was a reduction of

the total GHG emissions of 27 %, 7 % above the minimum requested target of 20 %.

Results from the plans monitoring reported, reveal an already achieved 23 % overall

reduction in emissions. The important role of the Covenant is mentioned and

acknowledged in several European Commission policy documents: the Energy Efficiency

Directive (

13

), the European Commission’s Energy Union Package (

14

), the European

(

7

) https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2030_en

(

8

) https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/adaptation/what_en

(

9

) SECAP template (CoMO, 2016) - available in all EU languages and downloadable from the Covenant website

library: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/index.php?option=com_attachments&task=download&id=142

Commonly referred to as SEAP or SECAP template, it aims to assist signatories in presenting their action plan in

a structured wayas well as tracking their implementation progress.

(

10

) Covenant of Mayors Reporting Guidelines (CoMO, 2016) - available in all EU languages and downloadable

from the Covenant website library:

https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/index.php?option=com_attachments&task=download&id=172. It provides

signatories with practical information on how to fill in the reporting template and includes illustrative examples.

(

11

) "Covenant of Mayors: Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Achievements and Projections" (Kona A. et al 2016)

(

12

) "Covenant of Mayors in figure: 8-years Assessment" (Kona A. et al 2017)

(

13

) EED 2012/27/EU

(

14

) COM/2015/080

10

Commission’s European Energy Security Strategy (

15

), and the European Strategy for a

Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy (

16

).

1.3 About the Global Covenant of Mayors

Since its launch in 2008, the initiative has progressively grown into a worldwide city

movement (

17

), extending first to the East and South neighbouring countries of Europe

(respectively in 2011 and 2012) and later to sub-Saharan African countries.

In January 2017, a merge of the initiatives Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy

(2030 target) and Compact of Mayors (

18

) into the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate

and Energy (GCoM) was announced.

The Global Covenant of Mayors is an international alliance of cities and local governments

with a shared long-term vision of promoting and supporting voluntary action to combat

Climate Change and move to a low-emission resilient society. This new initiative brings

together all the commitments of these local authorities with the support of Regional

offices, city/regional networks and/or national governments to link city contributions to

the Paris Climate Agreement. This coalition already represents about 11% of the world’s

population as of May 2018, and 7,755 towns and cities, have joined it through the

Covenant of Mayors framework, while 428 global cities joined via the Compact of Mayors.

An overview of the evolution of the initiative from 2008 to present days is shown in

Figure 2.

Thus far, the European Commission has been funding nine regional and national

Covenant Offices (including in North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, China

and South-East Asia, India and Japan - in addition to the 3 regions mentioned above:

East and South neighbouring and Sub-Saharan African countries) in order to support the

international dimension of the initiative.

Figure 2. Covenant of Mayors evolution

(

15

) COM/2014/0330 final

(

16

) COM 2016/501final

(

17

)‘Origin & developments’ page of the EU Covenant of Mayors website:

https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/about/covenant-initiative/origins-and-development.html

(

18

) Launched in 2014 by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and former New York City Mayor Michael

Bloomberg (former UN Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change), the Compact of Mayors was a global

coalition of city leaders addressing Climate Change by pledging to cut greenhouse gas emissions and prepare

for the future impacts of Climate Change (Barron-Lopez, Laura. "UN launches global mayors network to fight

climate change". The Hill. Retrieved 2015-12-03.)

11

Towards a Global Covenant Reporting Framework

The current shaping of the Covenant as a global initiative will influence how local level

climate action will be supported, recognised and used in the international (but also

national) processes. The Global Covenant movement indeed showcases the collective

impacts of cities from around the globe. Efforts are underway to streamline measurement

and reporting procedures, and enable meaningful comparison and aggregation with other

cities. To this end, a set of recommendations (to be released in 2019) towards a common

global reporting framework for city i) emissions inventories, ii) targets, iii) risk and

vulnerability assessments and iv) climate action plans have been developed and

submitted for public consultation in the various regions and nations. These

recommendations will be refined based on the outcomes of the consultation to ensure

they best meet local governments’ needs in specific local or regional circumstances.

Note that the resulting Global Covenant framework will in any case allow for the

continuation of the reporting requirements by current European Covenant cities (as

defined in the present document).

1.4 About this Guidebook

This Guidebook aims at supporting local authorities in the European Union (EU) Member

States joining the Covenant of Mayors for Energy and Climate (2030 target). Local

authorities will play a key role in the achievement of EU's energy and climate objectives

(reduce the overall emissions to at least 40% by 2030, enhance the resilience of cities

and assure a sustainable, secure and affordable access to energy).

The concrete purpose of the present guidebook is helping European local authorities in

developing the steps towards the committed targets, in particular:

Define the key elements of the initiative

Elaborate a Baseline Emission inventory (BEI)

Perform a Risk and Vulnerabilities Assessment (RVA)

Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP)

Support the implementation and monitoring of the SECAP.

Step-by-step recommendations are provided for the entire process of elaborating a local

energy and climate strategy, form initial political commitment to implementation and

monitoring of the plan. The guidebook is providing a set of flexible but coherent

principles and recommendations, allowing both local authority front runners and

newcomers to take local level climate action through the CoM (

19

) in the way which best

suits their circumstances and capabilities.

The Guidebook is divided into three Parts:

Part 1: Relates to the overall SECAP process, covering strategic issues.

Part 2: Relates to municipality assessments, as pre-requisite to the SECAP development,

they will provide knowledge on the nature of the emitting entities, risk and vulnerabilities

in the municipality territory.

• Part 2.a: Guidance on how to elaborate the Baseline Emission Inventory

(BEI) and the Monitoring Emission Inventory (MEI)

• Part 2.b: Guidance on how to perform a Risk and Vulnerability Assessment

(RVA)

(

19

) "In –depth analysis of Sustainable Energy Action plans" Rivas S. et al , 2015

12

Part 3: Relates to the description of technical questions, measures and policies that can

be implemented at local level by the local authority per sector of activity

• Part 3.a: Focuses on Climate Change mitigation

• Part 3.b: Focuses on Climate Change adaptation

• Part 3.c: Focuses on financing mechanisms for SECAPs

The Guidebook has been prepared by the Joint Research Centre Directorate-General

(JRC) of the European Commission, with the support and input of the Directorate-General

for Energy (DG ENER), Directorate-General for Climate Action (DG CLIMA), the Covenant

of Mayors Office (CoMO) and experts form municipalities, regions agencies and private

companies.

The terms “cities” and “local authorities (LAs)” are used throughout this

document, understanding that the geo-political institutions of local governments may

vary from country to country and terminology used may differ. In this document, a

city refers to a geographical subnational jurisdiction (“territory”) such as a

community, a town, or a city that is governed by a local authority as the legal entity

of public administration.

13

2 The Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan – a way to

go beyond the European Union targets

The Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) is the key document that shows

how a Covenant signatory will reach its commitments by 2030. The development of the

SECAP primarily draws on the findings from the Baseline Emission Inventory (BEI) and

the Climate Change Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (RVA). Through the development

of the BEI, the signatory is able to develop an overview of its greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions, and set appropriate strategies to reach its reduction target (of at least 40%

by 2030 compared to the baseline). Similarly, the RVA identifies the most relevant

climate hazards and vulnerabilities affecting the local authority, facilitating the process of

addressing such risks through the development of an adaptation strategy and

identification of appropriate adaptation actions. Through the combination of these

aspects, the SECAP defines concrete measures for both climate mitigation and

adaptation, with timeframes and assigned responsibilities, translating the long-term

strategy into action. Signatories commit themselves to submitting their SECAPs within

two years following adhesion.

To ensure that adequate action is taken to mitigate and adapt to Climate Change, the

SECAP should not be regarded as a fixed and rigid document. Since circumstances can

change and the ongoing actions provide results and generate local experience, it may be

useful or necessary to revise the plan on a regular basis.

Opportunities to make cities more climate-resilient arise with every new development

project to be approved by the local authority. The impacts of missing such an opportunity

can be significant and will last for a long time. This means that climate related

considerations should be taken into account for all new developments, even if the SECAP

has not yet been finalised or approved.

If a signatory has already developed a Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP) in the past

with an emission reduction target by 2020 and/or a climate adaptation strategy/plan

(under Mayors Adapt), their previous commitment(s) remain(s) valid. Joining the new

Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy will demand to sign up to the new initiative

to formalise new (post-2020) commitments through a decision by the municipal council,

and to prepare a SECAP as a natural extension of the existing plan.

2.1 Scope of the SECAP

The Covenant of Mayors concerns action at local and regional level within the

competence of the local authority. The SECAP should concentrate on measures aimed at

reducing GHG emissions such as carbon dioxide (CO

2

), and the final energy consumption

by end users, as well as include adaptation actions in response to the impacts of Climate

Change. The Covenant's commitments cover the whole geographical area of the local

authority (town, city, region). Therefore, the SECAP should include actions concerning

both the public and private sectors. However, the local authority is expected to play an

exemplary role and therefore to take outstanding measures related to its own buildings

and facilities, vehicle fleet, etc.

For Climate Change mitigation, the main target sectors are buildings, equipment/facilities

and urban transport (

20

,

21

). The SECAP may also include actions related to local electricity

production (development of solar photovoltaic (PV), wind power, combined heat power

(CHP), improvement of local power generation), and local heating/cooling generation. In

addition, the SECAP should cover areas where local authorities can influence energy

consumption on the long term (as land use planning), encourage markets for energy

efficient products and services (public procurement), as well as changes in consumption

(

20

) “Urban CO2 mitigation strategies under the Covenant of Mayors: An assessment of 124 European cities.

Croci et al, 2017

(

21

)

"Covenant of Mayors in figures: 8 years assessment" Kona et al, 2017

14

patterns (working with stakeholders and citizens) (

22

). On the contrary, the industrial

sector is not a key target of the Covenant of Mayors, so the local authority may choose

to include actions in this sector or not. In any case, plants covered by the EU Emissions

Trading Scheme (EU ETS)

23

shall be excluded, unless they were included in previous

plans of the local authority. A detailed description of the sectors to be covered in the

Baseline Emission Inventory is provided in Section 3.1. of Part 2.a.

For adaptation to the impacts of Climate Change, the SECAP should include actions in the

sectors and areas, which are likely to be most vulnerable to Climate Change in a city

(hotspots). Vulnerable sectors (e.g. buildings, transport, energy, water, waste, land use

planning, environment & biodiversity, agriculture & forestry, health, civil protection &

emergency, tourism) can vary considerably within urban perimeters, from one city to

another, from urban areas to more rural areas: this is why gaining a deep understanding

of the hazards and vulnerabilities of the local authority is of paramount importance.

Finally, as recognised by the Paris Agreement establishing a global goal on mitigation (

24

)

and adaptation (

25

) and putting mitigation and adaptation in parity, SECAPs should seek

and identify complementarities between mitigation and adaptation, and mainstream them

into existing sectorial policies in order to foster synergies and optimize the use of

available resources. Due consideration should be taken during the development of

mitigation and adaptation actions alike to enhance synergies, and to the greatest extent

possible, avoid adverse impacts. This is particularly relevant in the case of

maladaptation, where actions might lead to an increased vulnerability of other systems,

sectors or social groups (

26

).

2.2 Time horizon

The time horizon of the Covenant of Mayors is 2030. Therefore, the SECAP has to contain

a clear outline of the strategic actions that the local authority intends to take in order to

reach its commitments by 2030. The SECAP may cover a longer period, but in this case it

should contain intermediate values and objectives for the year 2030. For local authorities

who joined the Covenant before the 1

st

November 2015, the 2020 target remains an

important milestone towards the 2030 commitments.

As it is not always possible to plan in detail concrete measures and budgets for such a

long time span, the local authority may distinguish between:

A vision, with long-term strategy and goals until 2030 and/or beyond, including firm

commitments in areas like land-use planning, transport and mobility, public

procurement, standards for new/renovated buildings etc.

Detailed measures for the next 3-5 years, which translate the long-term strategy and

goals into real actions.

Both the long-term vision and the detailed measures shall form an integral part of the

SECAP. Example of long-term vision and its translation into real action is provided in the

following box.

(

22

)Effective information measures to promote energy use reduction in EU Member States" Rivas S. et al 2016

(

23

) Consolidated version of the Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13

October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and

amending Council Directive 96/61/EC

(

24

) Article 2 of the Paris Agreement establishes the global temperature goal, i.e. holding the increase in the

global average temperature well below 2 degrees C above preindustrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the

temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

(

25

)

Article 7.1 of the Paris Agreement establishes the global goal on adaptation of enhancing adaptive capacity,

strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change.

(

26

) Barnett, J., & O'Neill, S. (2010). Maladaptation. Global Environmental Change(20), 211-213.

15

Example of long-term strategy on transport: a local authority decides that all the cars

purchased for the municipal fleet should be electric.

Of course, the municipality cannot vote the budget for all the cars that will be purchased

up until 2030, but they could reflect it in its public procurement procedures can include

this measure in the plan and evaluate its impact till 2030.

For the duration of the local authority's political mandate, this measure should be

presented in very practical terms, with budgets, identification of financing sources, etc.

A robust planning of climate action must integrate short-term needs with long-term

threats and consider the full range of interactions between sectors and policies in order

to avoid maladaptation (

27

).

Maladaptation: (see also the glossary) interventions and investments in a specific

location or sector that could increase the vulnerability of another location or sector, or

increase the vulnerability of the target group to future climate change. Maladaptation

arises not only from inadvertent badly planned actions, but also from deliberate decisions

focused on short-term benefits ahead of longer-term threats, or that fail to consider the

full range of interactions, feedbacks and trade-offs between systems and sectors arising

from planned actions. As an example, water desalination technologies that are based on

fossil fuels.

As mentioned, setting an Emission reduction target to 2030 is mandatory for all

signatories of the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. Nevertheless, signatories

are warmly recommended to set and to report on a longer-term target as well, to

demonstrate that they have a vision towards decarbonised and resilient territories,

providing universal access to secure, sustainable and affordable energy services for all.

For this purpose, both the target year (beyond 2030) and the minimum emission

reduction objective can be freely set by the local authority. Nonetheless, the Covenant

recommends that these are in line with the national commitments or with the EU

commitments (80 - 95% overall GHG reduction objective by 2050 as mentioned in the

Roadmap to a low carbon economy (

28

) choosing whichever is higher).

It is also strongly recommended that measures related to the local authority's own

buildings and facilities are implemented first, in order to set an example and motivate the

stakeholders (Table 1).

(

27

) Juhola, S., Glaas, E., Linnér, B.-O., & Neset, T.-S. (2016). Redefining maladaptation. Environmental

Science & Policy(55), 135-140.

(

28

) COM/2011/0112 final - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the

European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a Roadmap for Moving to a

Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050

16

Table 1. Exemplary actions implemented in municipal buildings

Actions in Municipal buildings, equipment and facilities

City

Measure

Barcelona

Installation of solar thermal systems in sports centres.

Monitoring energy systems in every municipal building.

Turin

Energy action plan for municipal building stock: development of a base-

line energy consumption inventory and planning of retrofit of the building

stock.

Ostrava

Energy action applied in 21 public buildings including: additional thermal

insulation of the building shell; replacement of windows; thermal

insulation of ceilings; modernisation of the boiler or the heat exchanger

plant, as appropriate heating control (incl. the use of IRC - Individual

Room Control).

Energy Performance Contracting: yearly mandatory energy audit in all

municipal buildings.

Tallin

Consuming Green: renovation of 48 kindergarten.

Installation of new efficient lights and their control in the public lightning

net.

Larnaka

A wide range of measures which complement themselves in saving

energy and reducing CO2 in the building stock: thermal insulation of

buildings, lamp replacement with high efficiency ones, voltage rectifier,

maintenance of air conditioning systems, installation of solar panels.

Sonderborg

Various programs and concepts for: energy renovation of public

buildings, purchase of energy efficient appliances and equipment, energy

efficient lighting and energy training of employees.

Burgas

Retrofitting and renovation of municipal, social, cultural, administrative

infrastructure and introduction of energy efficiency measures.

Energy monitoring of buildings municipal properties.

2.3 The SECAP process

The chart in Figure 3 details the key steps for elaborating and implementing a successful

SECAP. As shown in the graph, the SECAP process is not a linear one, and some steps

may overlap with others. Besides, it is possible that some actions will have started before

the adhesion to the Covenant (not shown in the graph).

17

Figure 3. The SECAP process

The SECAP process : the main steps

PHASE

STEP

Correspondent

guidebook

chapter

Initiation

Political

commitment

and signing of

the Covenant

Part 1, chapter 3

Mobilize all

municipal

departments

involved

Part 1, chapter 4

Build support

from

stakeholders

Part 1, chapter 5

Planning phase

Assessment of

the current

framework:

Where are we?

Part 1, chapter 6

and Part 3

Establishment

of the vision:

Where do we

want to go?

Part 1, chapter 7

Elaboration of

the plan:

How do we get

there?

Part 1, chapter 8

Plan approval

and

submission

Implementation phase

Implementation

Part 1, chapter 9

Monitoring and reporting

phase

Monitoring

Part 1, chapter

10

Reporting and

submission of

the

implementation

report

Review

Reporting

guidelines

18

2.4 Human and financial resources

SECAP elaboration and implementation requires human and financial resources. Local

authorities may adopt different approaches:

— Using internal (in-house) resources, for example by integrating the tasks in (an)

existing department(s) of the local authority involved in sustainable development/

energy- and climate-related topics (e.g. local Agenda 21 office, environmental and/or

energy department).

— Setting up a new unit within the local administration (approx. 1 person/100,000

inhabitants).

— Outsourcing (e.g., private consultants, city-networks, universities …).

— Sharing one coordinator among several local authorities, particularly in the case of

small local authorities.

— Getting support from local and regional energy agencies (LAREAs) or Covenant

Territorial Coordinators (CTCs)(

29

) (see chapter 4).

— Developing a joint SECAP in coordination and collaboration with neighbouring local

authorities.

Note that the human resources allocated to the SECAP may be highly productive from a

financial point of view, via savings on the energy bills, access to European funding for the

development of projects in the field of Energy Efficiency (EE) and RES.

In addition, extracting as much as possible resources from inside offers the advantages

of a higher ownership, saves costs and supports the very materialisation of a SECAP.

Adequate training should also be offered to officers dealing with SECAP elaboration and

implementation.

2.5 Joint SECAPs

Should a group of adjoining Covenant of Mayors´ signatories want to elaborate a

common SECAP, they are allowed to do so, preferably under the aegis of a Covenant

Territorial Coordinator (CTC) a role officially recognised by the European Commission.

CTCs are decentralised authorities, such as regions, provinces or groupings of local

authorities, or national public bodies. Authorities acting as Covenant Coordinators commit

to providing signatories with the technical, financial, administrative and political support

necessary to fulfil their commitments.

Since Climate Change has a regional scale in many sectors – e.g. water management and

transport – collaboration at regional level between municipalities and with regional

agencies is needed. This network of cities within the same risk zone and with similar

vulnerability factors could facilitate data and good-practice exchange, better use of

available resources (e.g., river basin management), and define common targets and

monitoring systems.

Two options of joint SECAP are allowed:

— Joint SECAP Option 1, recommended for two or more local authorities willing to

implement one or several joint actions, but remaining individually committed to the

2030 target. In this case cities can submit one single SECAP document approved by

the municipal council (or equivalent decision-making body) of each of the

municipalities, but each city has to fill-in its own template. The mitigation objective of

reducing 40% of the CO

2

emissions by 2030 is not shared by the group of cities as it

remains an individual objective of each city participating in the joint SECAP. The

(

29

) Covenant Coordinators (roles, list): https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/about/covenant-

community/coordinators.html

19

emissions´ reductions corresponding to the common measures proposed in the

SECAP will be divided among each city sharing these measures.

As examples, the case of Avola in Italy or Berlaar in Belgium.

— Joint SECAP Option 2, recommended for:

o a group of small- and medium-sized municipalities within the same territorial

area (indicatively with less than 10,000 inhabitants each);

o an urban agglomeration, like a metropolis with its suburbs.

In this case, the group is registered as one signatory and has to submit only one

SECAP document, approved by the municipal council (or equivalent decision-making

body) of each of the local authorities and to fill-in only one template. In the SECAP

document, the specific contribution to the overall plan of each local authority needs to

be defined.

Under this option we can find as example "Associazione Intercomunale Terre Estensi"

in Italy, "Lokaal klimaatbeleid Noord-West-Vlaanderen" in Belgium, "Municipis de la

Serra de l’Estela de l’Alt Empordà" in Spain, "Bacău County" in Romania, or Mezilesí

in Check Republic.

For the adaptation pillar: Signatories can decide to prepare a Risk and Vulnerability

Assessment and its corresponding actions jointly or individually.

More information can be found in the Quick Reference Guide 'Joint Sustainable Energy

Action Plan' by the Covenant of Mayors Office– available in the main EU languages:

https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/index.php?option=com_attachments&task=download

&id=210.

2.6 SECAP document, template and submission procedure

Covenant signatories commit to submitting their SECAPs within two years following

adhesion. They also commit to providing regular implementation reports outlining the

progress of their action plan.

The SECAP official document must be approved by the municipal council (or equivalent

decision-making body) and uploaded in national language via the 'My Covenant' (on-line

password-restricted area: http://mycovenant.eumayors.eu/). Covenant signatories will

be required, at the same time, to fill in an online SECAP template in English. This will

allow them to summarise the results of their Baseline Emission Inventory and of the

Climate Change Risk and Vulnerability Assessment, as well as the key elements of their

SECAP. The timeline and requirements of reporting are shown in Table 2.

20

Table 2. Minimum reporting requirements

Moreover, the template is a valuable tool that provides visibility to the SECAP and

facilitates its assessment, as well as the exchange of experience among the Covenant

signatories. Highlights of the information collected will be shown online in the Covenant

of Mayors website under the signatory profiles.

The SECAP template is available online as an internet-based tool that the Covenant

signatories are required to fill in themselves. A public copy of the SECAP template and

supporting instructions document (

30

) are available in the library of the Covenant of

Mayors website: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/support/library.html (under “type”,

select “technical materials”).

The JRC of the European Commission is in charge of the evaluation of the documentation

and data provided by signatories. The analysis is essentially focusing on the compliance

of the SECAP with the Covenant formal commitments and principles as well as on the

evaluation of the completeness and consistency of the data inserted in the template.

The signatory receives a feedback report serving the purpose of informing the signatory

on whether the SECAP fulfils the eligibility criteria and also provides observations and

suggestions for improvement.

(

30

) The Covenant of Mayors for Energy and Climate Reporting Guidelines. JRC103031

21

2.6.1 Recommended SECAP structure

The Covenant signatories could follow the structure of the SECAP template when

preparing their Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plans. The suggested content of

the SECAP document is (see also Figure 4):

(a) SECAP Executive Summary

(b) Strategy

1. Vision

2. Commitments both for mitigation and for adaptation:

a. For mitigation, the SECAP document should clearly indicate

the emission reduction target by 2030 (and possibly beyond)

clearly stating the BEI year and the reduction target type

(absolute reduction or per capita reduction

31

)

b. For adaptation, the SECAP should include a certain number

of adaptation goals, coherent with the identified

vulnerabilities, risks and hazards.

3. Coordination and organisational structures created/assigned

4. Staff capacity allocated

5. Involvement of stakeholders and citizens

6. Overall budget for implementation and financing sources

7. Implementation and Monitoring process

8. Assessment of the Adaptation Options

9. Strategy in case of extreme climate events

(c) Baseline Emission Inventory (BEI)

1. Inventory year

2. Number of inhabitants in the inventory year

3. Emission factors approach (standard or LCA)

4. Emission reporting unit (CO

2

or CO

2

-equivalent)

5. Responsible body/department (main contact)

6. Detailed BEI results in terms of final energy consumption

and GHG emissions

If relevant, please also specify:

7. Inclusion of optional sectors and sources

8. Assumptions made, references or tools used

9. Reference to the BEI inventory report

(

31

) See Chapter 2 of Part 2.a of the SECAP Guidebook for more advise on the choice of the reduction target

type

22

Figure 4. SECAP template

Source:

Top image: Screenshot of the “strategy” tab of the online reporting template available at: “My Covenant” area

of the website);

Bottom image: Summary table of the template content (Source: Reporting Guidelines, CoMO, 2017)

23

It is in the interest of the local authority to prepare a detailed documentation of the

methodologies and data sources used to develop the BEI. This will facilitate the

compilation of the Monitoring Emission Inventories (MEI) in the following years. Covenant

Signatories are encouraged to compile MEIs on a regular basis. The minimum

requirement in the context of the Covenant of Mayors is to do it every 4 years. In this

way, subsequent inventories may be compared with the Baseline Emission Inventory

(BEI), and progress in terms of emissions reduction can be monitored. A MEI for the

target year should as well be provided once local authorities have the available data in

order to assess the achievement of their CO

2

emissions reduction target. Detailed

information relating to the inventory, including data interpretation, can be provided

either as part of the SECAP document or in separated BEI/MEI inventory reports (see

Part 2.a of this Guidebook, chapter 5 “Documentation and Reporting”).

(d) Climate Change Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (RVA)

1. Expected weather and climate events particularly relevant

for the local authority or region

2. Vulnerabilities of the local authority or region

3. Expected climate impacts in the local authority or region

4. Assets and people at risk from Climate Change impacts

(e) Mitigation actions and measures for the full duration of the plan (2030). For each

measure/action, please specify (whenever possible):

1. Description

2. Responsible department, person or organisation

3. Timing (end-start, major milestones)

4. Cost estimation (Investment and running costs)

5. Estimated energy saving/increased renewable energy

production by target year

6. Estimated GHG reduction by target year

7. Indicators for monitoring

(f) Adaptation actions and measures for the full duration of the plan (2030). The

actions should be coherent with outcomes of the city vulnerability and risk

assessment (RVA). For each measure/action, please specify (whenever possible):

1. Sector

2. Title

3. Description

4. Responsible body/department/ and contact point

5. Timing (end-start, major milestones)

6. Action also affecting mitigation?

7. Stakeholders involved/advisory group

8. Impacts, vulnerabilities and risks tackled

9. Costs (€) (Investment and running costs)

10. Indicators for monitoring

24

Both for mitigation and for adaptation, the level of detail in the description of each

measure/action is to be decided by the local authority according to expected results, data

availability and quality. However, bear in mind that the SECAP is at the same time:

— A working instrument to be used during implementation (at least for the next few

years)

— A communication tool towards the stakeholders

— A document that is agreed at the political level by the various parties in charge within

the local authority: the level of detail should be sufficient to avoid further discussion

at the political level over the meaning and scope of the various measures.

2.7 Key elements of a successful SECAP

Build support from stakeholders and citizen participation: if they support the

SECAP, nothing should stop it!

Secure a long-term political commitment

Ensure adequate financial resources

Do a proper GHG emissions inventory as this is vital

Make a Climate Change RVA, based on an analysis of the local/regional

trends of various climate variables and city socioeconomic and biophysical

specificities

Integrate the SECAP into everyday management processes of the

municipality: it should not be just another nice document, but part of the

corporate culture!

Ensure proper management during implementation

Make sure that staff has adequate skills, and if necessary offer training

Learn to devise and implement projects over the long term

Actively search and take advantage of experiences and lessons learned from

25

2.8 Ten key elements to keep in mind when preparing a SECAP

As a summary of what is presented in this Guidebook, here are the 10 essential

principles that should be kept in mind when elaborating a SECAP (

32

). These principles

are linked to the commitments taken by the Covenant signatories and constitute key

ingredients to success. Failure to meet these principles may prevent SECAP acceptance.

1. Formal adoption of the plan by the municipal council (or equivalent decision-

making body)

Strong political support is essential to ensure the success of the process, from SECAP

design to implementation and monitoring (

33

). This is why the SECAP document must be

approved by the municipal council (or equivalent decision-making body).

2. Definition of clear mitigation and adaptation target(s) / goal(s)

The SECAP document must contain a clear reference to the core emission reduction

commitment taken by the local authority when signing the Covenant of Mayors. The

recommended baseline year is 1990, but if the local authority does not have data to

compile a CO

2

inventory for 1990, then it should choose the closest subsequent year for

which the most comprehensive and reliable data can be collected. The overall CO

2

reduction commitment has to be translated into concrete actions and measures together

with the CO

2

reduction estimates in tons/year by 2030. For the local authorities that have

a longer term CO

2

reduction target (for example by 2050) they should set an

intermediary target by 2030 (40% as a minimum) for the reasons of comparability. In

addition to the mitigation commitment, adaptation goals have to be specified coherently

with the main outcomes of the vulnerability and risk assessment.

3. Sound assessment of the local situation (based on the Baseline Emission

Inventory (BEI) and a Climate Change Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (RVA)

outputs)

The SECAP should be elaborated based on a sound knowledge of the local situation in

terms of energy and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as of climate hazards,

vulnerabilities and impacted policy sectors. Therefore, an assessment of the current

framework should be carried out (

34

). This includes elaborating a Baseline Emission

Inventory (BEI) and preparing a Climate Change Risk and Vulnerability assessment (RVA)

– in line with the CoM commitments. The results of both the BEI and BEI and the RVA

have to be included in the SECAP document.

The BEI and subsequent inventories are essential instruments that allow the local

authority to have a clear vision of the priorities for action, to evaluate the impact of the

measures and determine the progress towards the objective. It allows maintaining the

motivation of all parties involved, as they can see the result of their efforts. Here are

some specific points of attention:

● The BEI has to be relevant to the local situation, i.e., based on energy

consumption/production data, mobility data etc. within the territory of the local authority.

Estimates based on national/regional averages would not be appropriate in most cases,

as they do not allow capturing the efforts made by the local authority to reach its CO

2

targets.

● The methodology and data sources should be consistent through the years.

● The BEI must cover at least the sectors in which the local authority intends to take

action to meet the emission reduction target. The following are considered key Covenant

(

32

)

More practical tips are available in the e-learning tool developed by CoMO and available in the restricted

area of the Covenant website (in particular in the “Getting started” module).

(

33

) See chapter 3 of part 1 of the SEAP guidebook for guidance on political commitment

(

34

) See chapter 6 of part 1 of the SEAP guidebook for guidance on assessment of the current framework

26

sectors as they represent significant CO

2

emission sources in urban environment and can

be influenced by the local authority: residential, municipal and tertiary buildings and

facilities, and transport.

● The BEI should be accurate, or at least represent a reasonable vision of the reality.

● The data collection process, data sources and methodology for calculating the BEI

should be well documented (if not in the SECAP then at least in the local authority's

records).

The RVA enables local authorities to identify their exposure to current and potential

Climate Change impacts, vulnerabilities and risks, as well as understand the main city

specificities that contribute to aggravating the consequences of a specific climate hazard.

Similarly to the BEI, the RVA defines the basis for setting the priorities of investment and

monitoring the effectiveness of implemented adaptation measures for a specific region or

sector. To this end, indicators of climate vulnerability and risk have to be constructed -

on the basis of available data - and regularly monitored and evaluated versus a baseline

scenario.

4. Comprehensive measures addressing the key sectors of activity – as

identified in the signatory’s assessments (BEI & RVA)

The commitment taken by the signatories concerns the reduction of the CO

2

emissions in

their respective territories. Therefore, the SECAP has to contain a coherent set of

mitigation measures covering possibly all the Covenant key sectors of activity: not only

the buildings and facilities that are managed by the local authority, but also the sectors

of activity in the territory of the local authority: residential sector, tertiary sector, public

and private transport (

35

). Before starting the elaboration of actions and measures, the

establishment of a long-term vision with clear objectives is highly recommended

36

.

The adaptation strategy should be part of a stand-alone document (e.g. the so-called

SECAP) and/or mainstreamed in separate documents. Based on recognised local risks

and vulnerabilities, the local authority should identify actions aimed at enhancing local

adaptive capacity to respond to Climate Change impact and/or reducing city sensitivity to

climate extremes. The key actions should be implemented within the prioritized hotspots

of vulnerability and risk in order to reduce the probability of high losses and damages.

Mitigation actions should be looked at through a Climate Change lens, to understand if

they themselves are vulnerable to the impacts of Climate Change and/or they can

influence the vulnerability of natural and human systems to Climate Change. The SECAP

Guidebook contains many suggestions of policies and measures that can be applied at

the local level (

37

).

5. Strategies and actions until 2030

The plan must contain a clear outline of the strategic actions that the local authority

intends to take in order to reach its commitments by 2030. It has to contain:

● The strategy and goals until 2030, including firm commitments in areas like land-use

planning, transport and mobility, public procurement, standards for new/renovated

buildings etc.

● Detailed measures for the coming years, which translate the long-term strategy and

goals into actions. For each measure/action, it is important to provide a general

description, the responsible body, the timing (start-end, major milestones), the cost

estimation and financing/source, the indicators for monitoring. In addition, for mitigation

actions the following should also be indicated: estimated energy saving/increased

renewable energy production and associated estimated CO

2

reduction. For the key

(

35

) See chapter 3 of Part 2.a of the SECAP Guidebook for more advise on the sectors to be covered

(

36

) See chapter 7 of Part 1 of the SECAP Guidebook for guidance on the establishment of a vision and

objectives

(

37

) See part 3 of this SECAP Guidebook

27

adaptation actions, the stakeholders involved, the risk and/or vulnerability tackled and

the outcome reached should also be specified.

6. Mobilization of all municipal departments involved

The SECAP process should not be conceived by the different departments of the local

authority administration as an external issue, but it has to be integrated into everyday

processes

38

. The SECAP should outline which structures are in place or will be organised

in order to implement the actions and follow the results. It should also specify the human

resources made available. A coordinated (inter)action between mitigation and adaptation

through the mobilisation of all departments involved should be ensured. This implies

strong horizontal cooperation among policy sectors that are used to working in separate

silos to comply only with their sectoral agenda.

7 Engagement of citizens and stakeholders

In order to develop successful mitigation and adaptation planning, multiple stakeholder

engagement is required (

39