Proceedin

g

.: R.22-07-005

Exhibit No.: Joint IOUs-01

Witnesses: See Table of Contents

Joint Testimony of Southern California Edison

Company, Pacific Gas and Electric Company, and

San Diego Gas & Electric Company (the Joint IOUs)

Describing Income-Graduated Fixed Charge

Proposals

Joint IOUs’ Exhibit 1, addressing:

- Policy

- Rate Design

- Income Verification

- Implementation

- Marketing

- Cost Recovery

Before the

Public Utilities Commission of the State of California

April 7, 2023

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

Table Of Contents

Section Page Witness

-i-

I. POLICY .......................................................................................................1 M. Backstrom

A. Introduction ......................................................................................1

B. The Joint IOUs’ Residential Rate Proposals Comply with

Assembly Bill 205............................................................................2

1. Benefits of the Joint IOUs’ Proposals Compared

to Current Residential Rates ................................................6

a) Improving Equity by Bringing Rates Closer to

Cost of Service. ............................................................... 6

b) Addressing Affordability and Protecting Low-

Income Customers. ......................................................... 8

c) Encouraging Beneficial Electrification. ........................ 10

d) Promoting Bill Stability and Maintaining

Strong TOU Price Signals. ............................................ 14

2. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Will Apply to All

Residential Rate Schedules ................................................15

3. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Are Consistent with

Rate Design Principles. ......................................................16

C. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Should be Adopted as Soon as

Possible. .........................................................................................18

D. Income Verification Should Be Performed By State

Agencies and Not The IOUs ..........................................................18

E. Robust Marketing, Education, and Outreach Will be

Required .........................................................................................20

F. Conclusion .....................................................................................21

II. RATE DESIGN .........................................................................................22 G. Morien

R. Thomas

C. Kerrigan

A. Introduction ....................................................................................22

1. Summary of Proposals .......................................................22

B. Background ....................................................................................24

1. Recent Rate Design Policy Issues ......................................24

2. Next 10 Research on Potential Fixed Charges ...................28

3. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Align with

Modernized Rate Design Principles ...................................32

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

Table Of Contents

Section Page Witness

-ii-

C. Basis for the Average IGFC Level .................................................34

1. Methodology for Determining Average Fixed

Charge Level ......................................................................34

D. Income Graduated Fixed Charge Discount Levels ........................42

1. Summary ............................................................................42

a) Lower Average Monthly Bills for Low-

Income Customers ........................................................ 43

E. Impact of the IGFC on Rates and Other Rate Design

Issues ..............................................................................................44

1. Impact of the IGFC on Volumetric Rates ..........................44

2. Adjusting the IGFC Over Time for Revenue

Requirement Changes ........................................................45

3. IGFC Review and Assessment Over Time ........................46

4. CARE Discount Structure Changes ...................................47

5. FERA Interaction with IGFC .............................................49

6. Implementation of the IGFC on Non-Default

Residential Rates ................................................................50

7. Size Differentiation ............................................................51

8. Elimination of Minimum Bills ...........................................53

B. Calibration Mechanism for Structure Revisit ................................53

C. Public Tool Results ........................................................................54

III. INCOME VERIFICATION .......................................................................55 R. Alvarez

C. Coughlan

M.Fischlein

A. Introduction ....................................................................................55

1. Income Assignment and Verification - Objectives

and Evaluation Criteria ......................................................55

D. Stakeholder Input ...........................................................................58

1. Key Stakeholder Input .......................................................58

E. Income Definition ..........................................................................58

F. Household Income Brackets ..........................................................59

G. Income Verification Options Evaluated by the Joint IOUs ...........60

1. Introduction ........................................................................60

2. Using Current Program Information ..................................61

3. Using Available State Processes ........................................62

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

Table Of Contents

Section Page Witness

-iii-

a) DSS’s “CalFresh Confirm” Data .................................. 62

b) CPUC/ Third Party LifeLine Low Income

Program for Telecom Utilities ...................................... 64

4. Using Credit Agency Data .................................................65

5. Using Customer Stated or Verified Income Data ..............68

6. IOU Developed Data Model ..............................................73

7. Key Findings on Evaluated Options ..................................74

8. Recommendation ...............................................................76

H. Income Verification and Appeals Process .....................................78

1. Income Verification Ownership and

Implementation ..................................................................78

2. High Level Utility Process Overview ................................82

a) Initial Income Bracket Assignment .............................. 82

b) Appeals Process and Customer-Initiated

Income Updates ............................................................ 85

c) Periodic Refresh ............................................................ 89

I. Currently Projected Costs of Joint IOUs’ Proposal .......................89

J. Anticipated Costs for CPUC-Supervised Third Party

Income Verification .......................................................................90

1. High-Level Cost Estimates for the Other Major

Scenarios Evaluated but not Recommended – In-

House IOU Income Verification ........................................93

K. Timeline for Implementation of Third-Party Income

Verification ....................................................................................94

IV. IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................................96 N. Kane

M.McCutchan

E.Molnar

A. Introduction ....................................................................................96

B. Implementation Objectives and Plan Overview ............................97

C. Billing Information Technology System Changes .........................98

1. Implementation Timing ...................................................100

2. Approach to Transitioning Customers .............................102

3. Updates to Current Customer-Facing Tools ....................103

4. New Tools ........................................................................103

D. Coordination with Community Choice Aggregators ...................104

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

Table Of Contents

Section Page Witness

-iv-

E. Customer Support Resources - Contact Centers ..........................104

F. Costs .............................................................................................105

1. Implementation Costs ......................................................105

2. Measurement and Evaluation ...........................................107

G. High-Level Estimates of Timing and Cost for Other

Anticipated Proposals ..................................................................107

V. MARKETING EDUCATION & OUTREACH ......................................109 A. Bernhardt

B. Kopec

E. Wasmund

A. Introduction ..................................................................................109

B. Research Insights .........................................................................109

1. PG&E ...............................................................................109

a) Stimuli ..............................................................................110

b) Key Findings ....................................................................111

2. SDG&E ............................................................................113

3. SCE ..................................................................................113

C. Joint IOU ME&O Proposal’s Objectives .....................................114

D. Lessons Learned from Residential Time-of-Use

Transition Inform IGFC Outreach Strategies ..............................115

E. Plans to Refine Outreach Plans Based on Findings from

Additional Research .....................................................................117

F. Target Audiences .........................................................................117

G. Rollout and Implementation ........................................................118

H. Messaging Phases and Customer Journey ...................................120

I. Integrated Campaign Tactics .......................................................122

J. Community Outreach Tactics ......................................................125

1. Community Based Outreach (CBO) ................................125

2. Joint IOU Employee Outreach .........................................126

3. External Stakeholders: .....................................................126

K. Metrics and Tracking ...................................................................126

L. Budget ..........................................................................................126

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

Table Of Contents

Section Page Witness

-v-

VI. COST RECOVERY .................................................................................128 R. Madsen

G. Morien

E. Pulgar

A. Introduction ..................................................................................128

B. Cost Recovery and Rate Making Proposal ..................................130

1. Cost Recovery Advice Letters Filings .............................130

2. Income Graduated Fixed Charge Balancing

Account (IGFCBA) ..........................................................131

1. Recovery of the IGFCBA Via the PPP Rate

Component .......................................................................134

2. Recovery of Income Verification Costs through

State Funding ...................................................................134

C. Recovery of Authorized Costs via the IGFC ...............................135

D. IGFC Calibration Mechanism ......................................................136

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Respective Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

List Of Tables

Table Page

-vi-

Table I-1 Illustrative Proposed IGFCs ..............................................................................................5

Table II-2 Illustrative Proposed IGFCs ............................................................................................24

Table II-3 Illustrative Summary of Impacts to Default Rates ..........................................................24

Table II-4 PG&E Default Rates Compared to Marginal Cost Metrics ............................................35

Table II-5 Illustrative Fixed Cost Revenue Requirement Categories in the

Public Tool ($/month charge) – Residential Non-CARE Customers ............................37

Table II-6 Revenue Requirement Categories Underlying the Joint IOUs’

Proposed Fixed Charges and Resulting Reductions in the Volumetric Rate Component

........................................................................................................................................38

Table II-7 IOUs’ Volumetric Rate Adjustment Methodology by Rate Schedule ............................44

Table II-8 SDG&E Illustrative CARE Bill Comparison .................................................................48

Table II-9 SCE Illustrative CARE Bill Comparison ........................................................................48

Table II-10 PG&E Illustrative CARE Bill Comparison ..................................................................48

Table III-11 Joint IOUs Percentage of Residential Customers by Income Brackets .......................60

Table III-12 Summary of Each Joint IOU’s Internal Costs to Support our

Recommended CPUC-Supervised Third-Party Approach to IGFC Income Verification

........................................................................................................................................90

Table III-13 Comparison of Third Party Income Verification Implementation Costs ....................92

Table IV-14 Joint IOU Residential Rates Impacted by IGFCs ........................................................99

Table IV-15 Implementation Milestones ........................................................................................102

Table IV-16 Estimated Implementation Costs by IOU ...................................................................106

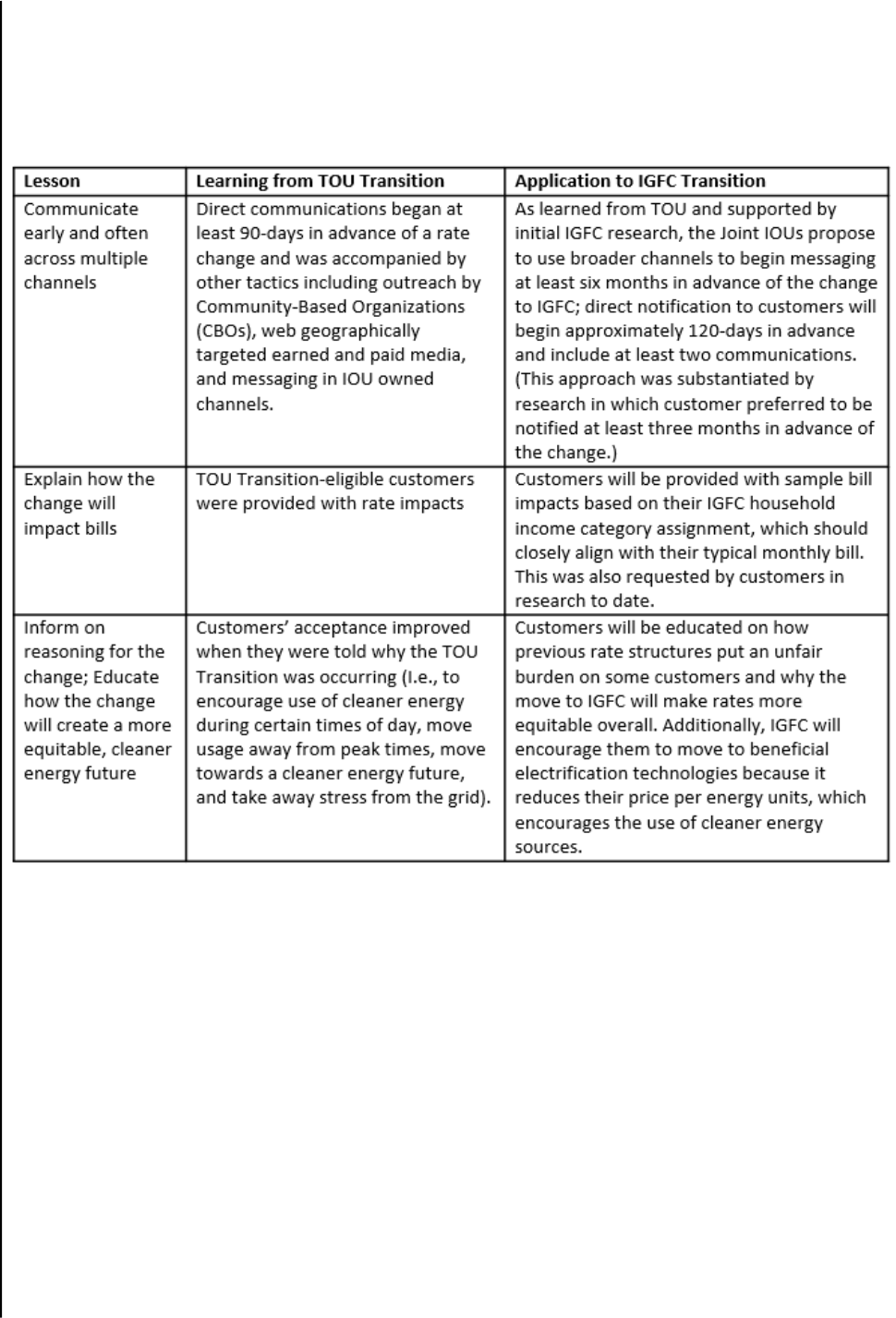

Table V-17 Useful Lessons from Residential Default TOU Transition to Inform IGFC ...............116

Table V-18 Joint IOUs’ Proposed Phased IGFC Communication Sample ....................................120

Table V-19 Initial Estimates of ME&O Costs, by IOU ..................................................................127

Testimony Describing Joint IOUs’ Respective Income-Graduated

Fixed Charge Proposals

List Of Figures

Table Page

-vii-

Figure I-1 Residential Rate Design Across the U.S. .........................................................................8

Figure I-2 Average Annual Percent Difference by Income Bracket ................................................10

Figure I-3 California’s Decarbonization Accomplishments and Future Goals ...............................11

Figure I-4 Current California GHG Emissions Inventory Data .......................................................12

Figure I-5 SCE Example: Non-CARE Inland Income Bracket 3 Customer Energy

Burden Comparison .......................................................................................................14

Figure II-6 2021 Next 10 Report Theoretical Fixed Charges - PG&E ............................................30

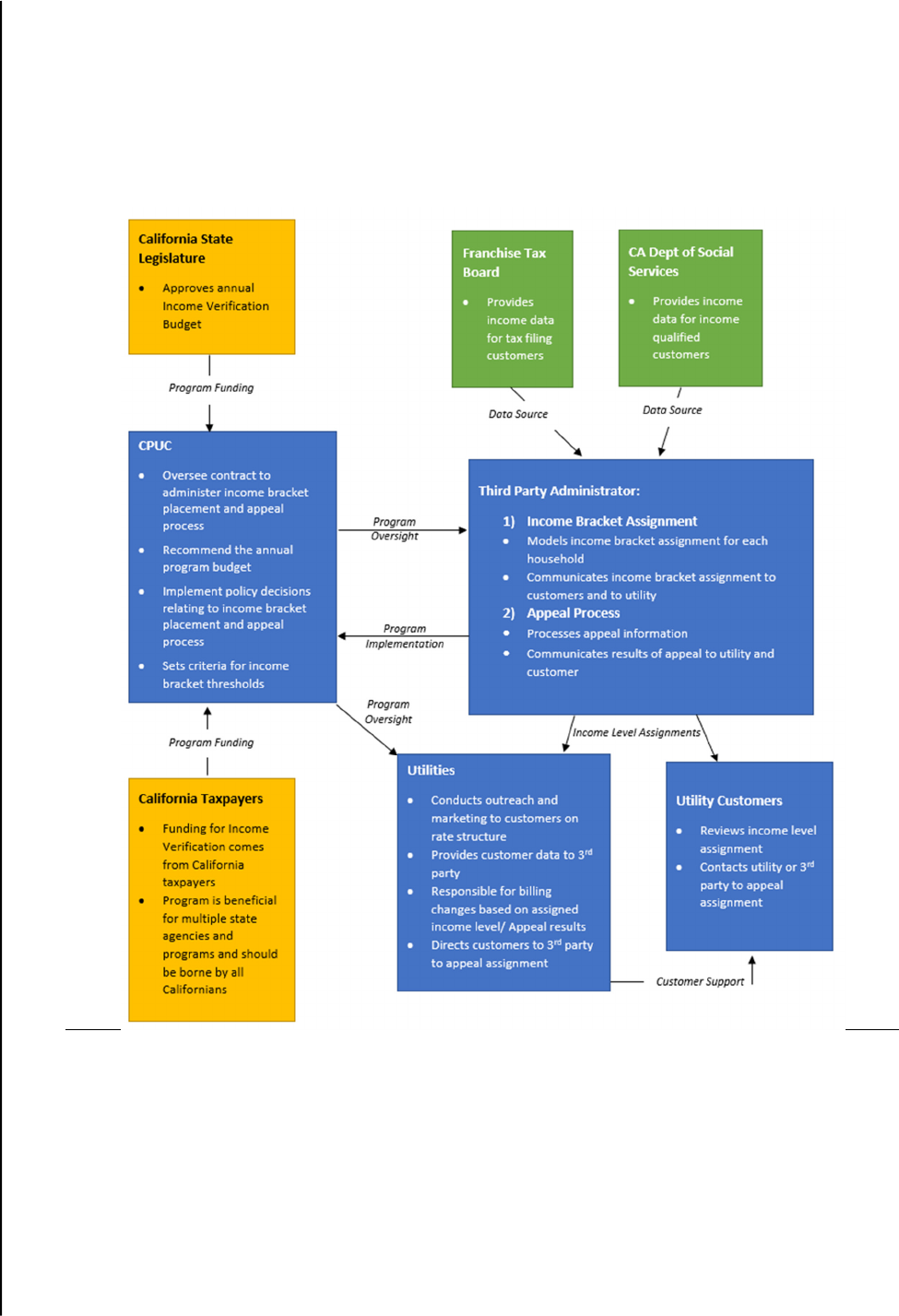

Figure III-7 Proposed High Level Chart of Entities Involved In Administration

and Implementation of Income Bracket Assignment and Appeal Process ...................81

1

I. 1

POLICY 2

A. Introduction 3

Current residential rate structures based primarily on volumetric rates do not reflect cost 4

of service, are not equitable, and do not send appropriate price signals to encourage broader 5

adoption of greenhouse gas (GHG) reducing technologies. The artificially high volumetric rates 6

in existing residential rate structures pose affordability challenges for many lower- and 7

moderate-income customers, very high bills for larger users, and monthly bill volatility. 8

In contrast, the Joint IOUs’ proposals to combine an Income Graduated Fixed Charge 9

(IGFC) with lower volumetric rates on all residential rate schedules will improve equity. Our 10

proposals will bring customers’ rates closer to the cost to serve them, result in greater month-to-11

month bill stability, and provide low-income customers with bill reductions, on average, relative 12

to the current rate structure. The lower volumetric rates will also encourage decarbonization by 13

making transportation and building electrification more affordable. More cost-based electricity 14

prices will compare more favorably to prices of gasoline and natural gas. As detailed in the 15

remainder of this chapter, these reformed residential rate structures are urgently needed to 16

support achievement of the state’s decarbonization goals. 17

The Joint IOUs’ proposals are designed to support the policy goals discussed, and since 18

customer acceptance of rate reform is key, continued customer research and marketing, 19

education, and outreach (ME&O) is needed to ensure customers have a positive experience. The 20

Joint IOUs’ proposed outreach and communication will make the reformed rate structures 21

transparent and understandable to customers and explain the expected overall benefits. 22

An important part of the Joint IOUs’ proposal is the recommendation that income 23

verification for purposes of assigning customer households to the appropriate IGFC level be 24

administered by a Third Party contractor supervised by the California Public Utilities 25

2

Commission (CPUC or Commission), as is done for the LifeLine program for 1

telecommunication companies.

1

The Joint IOUs today perform a limited form of income 2

verification in the narrow context of opt-in discount programs such as the California Alternate 3

Rates for Energy (CARE) program (where customers agree in their application to provide 4

requested income information, in order to qualify). However, the process of assigning all of 5

California’s residential electric customers to income categories is unprecedented, and requires 6

capabilities and processes that are best administered by a state agency – and are far beyond prior 7

utility experience and capabilities. Adding the resources and systems necessary for the energy 8

utilities to perform such income validation would not be cost effective. Doing so also raises 9

sensitive issues of consumer privacy, cybersecurity, and utility-customer relations. For these 10

reasons, as described in Chapter 3 of this Exhibit, income verification should be overseen by a 11

state agency, such as the CPUC, and likely conducted by a qualified third party that would apply 12

the necessary protocols to ensure a fair and positive customer experience. 13

B. The Joint IOUs’ Residential Rate Proposals Comply with Assembly Bill 205 14

In mid-2022, the California legislature, through Assembly Bill (AB) 205, removed the 15

statutory language requiring default residential rates to be almost exclusively charged on a 16

volumetric basis and provided a framework to make the residential electricity rate structure more 17

equitable. That bill’s amendments to Public Utilities Code § 739.9 now allow the CPUC to take 18

the next step in needed residential electric rate reforms, by collecting through a set IGFC costs 19

that do not vary volumetrically or are more equitability collected in a fixed charge. A fixed 20

charge alone results in volumetric rates more in line with cost of service, which help to control 21

high bills and bill volatility associated with event-driven higher usage, and greatly enhance the 22

widespread electrification efforts needed to achieve our state’s GHG reduction goals. AB 205 23

aims to offer all customers better price signals while also providing additional affordability 24

1

See R.22-07-005, Phase 1 Track A: Income-Graduated Fixed Charge Guidance Memo at p. 9.

3

protections for low-income customers through the IGFC. The Joint IOUs and other parties have 1

already briefed the CPUC on statutory interpretation issues relating to AB 205. Because the 2

CPUC has not yet ruled on those AB 205 legal issues, each party was directed to assume that its 3

own brief’s recommended interpretation of the statute is adopted. That directive was followed 4

herein as well as in each of the Joint IOUs’ individual rate calculations. 5

The Joint IOUs have developed a common, modernized rate design structure that 6

balances several key objectives, including supporting increased affordability for lower- and 7

moderate-income customers while also helping the state achieve its decarbonization goals in a 8

more equitable and affordable manner relative to the status quo. 9

The Joint IOUs have worked together, in collaborative discussion with a wide range of 10

other parties (including through Energy Division workshops) to carefully consider a range of 11

potential IGFC approaches. While each IOU is separately providing individual Rate Design 12

Exhibits based on its unique revenue requirements, customer distributions, and service options, 13

all proposals are guided by the following key principles: 14

Provide a better aligned cost-based residential rate structure that collects costs in a 15

more equitable manner from all customers through an IGFC; 16

Support a more progressive residential rate structure for customers that matches 17

income ranges with the level of monthly fixed charge each customer pays, providing 18

affordability and bill relief for vulnerable lower income customers through lower 19

volumetric rates and the IGFC; 20

Encourage electrification by reducing volumetric rates for all customers, providing a 21

stronger economic basis in electric rates for customers to adopt cleaner electrification 22

technologies; 23

Provide increased bill stability for customers because a portion of a customer’s bill 24

will remain flat and predictable from month to month; and 25

4

Maintain strong price signals during critical energy and grid hours through time-of-1

use (TOU) rate differentials that encourage customers to save by shifting use out of 2

these high-cost hours. 3

Today, lower- and moderate-income customers, on average, pay a greater percentage of 4

their income towards their electricity bill relative to higher income customers.

2

The Joint IOUs’ 5

proposals result in meaningful bill savings for these customers, with no change in usage. (See 6

Figure I-2 below.) As customers adopt environmentally-beneficial electrification technologies in 7

accordance with state policy, the Joint IOUs’ proposals significantly reduce volumetric rates and 8

make these new technologies more financially attractive.

3

Importantly, these rates would be 9

technology-agnostic, making them more flexible and available for all customers. The Joint 10

IOUs’ proposals also consider how best to balance competing considerations to make income 11

verification as accurate as possible, while also aiming for a cost-effective implementation of a 12

major structural change for all residential customers. 13

As described in the previously submitted briefs, the Joint IOUs interpret AB 205’s “no 14

fewer than three income thresholds” language to mean there must be at least three Income 15

Brackets. The Joint IOUs are proposing four household Income Brackets to achieve greater 16

progressivity by offering further relief to the most economically vulnerable households with the 17

highest energy burdens – those with incomes less than or equal to 100% of the Federal Poverty 18

Level (FPL). This strikes an appropriate balance, implementing a progressive IGFC structure 19

while minimizing the operational challenges inherent in having too many income brackets. 20

Specifically, the Joint IOUs propose the following four household Income Brackets: 21

Bracket 1 – CARE customers with incomes less than 100% of FPL; 22

2

Next 10 and Energy Institute at Haas, University of California, Paying for Electricity in California:

How Residential Rate Design Impacts Equity and Electrification (hereinafter Next 10, Paying for

Electricity in California) (Sept. 2022), available at https://www.next10.org/sites/default/files/2022-

09/Next10-paying-for-electricity-final-comp.pdf.

3

See Chapter 2 (Rate Design) for impact to volumetric rates.

5

Bracket 2 – Remaining CARE and Family Electric Rate Assistance (FERA) enrolled 1

customers; 2

Bracket 3 – Non-CARE or FERA customers with incomes up to or equivalent to 3

650% of FPL; and 4

Bracket 4 – Non-CARE customers with incomes above 650% of FPL. 5

While it is important to maintain affordability for the most vulnerable low-income 6

customers, it is also imperative that the overall average fixed charge across all four income 7

categories be sufficient to enable meaningful reductions in volumetric rates that incentivize 8

customer electrification efforts. Because each of the Joint IOUs has its own, CPUC-adopted, 9

marginal costs of service, the application of the proposed basic rate design structure described 10

here results in differing calculations of each Joint IOU’s specific fixed charges by household 11

Income Bracket. The illustrative proposed IGFCs for each of the Joint IOUs are shown in Table 12

I-1 below and the appendices to this Joint Testimony present the individual rate designs for each 13

IOU’s residential rate schedules. 14

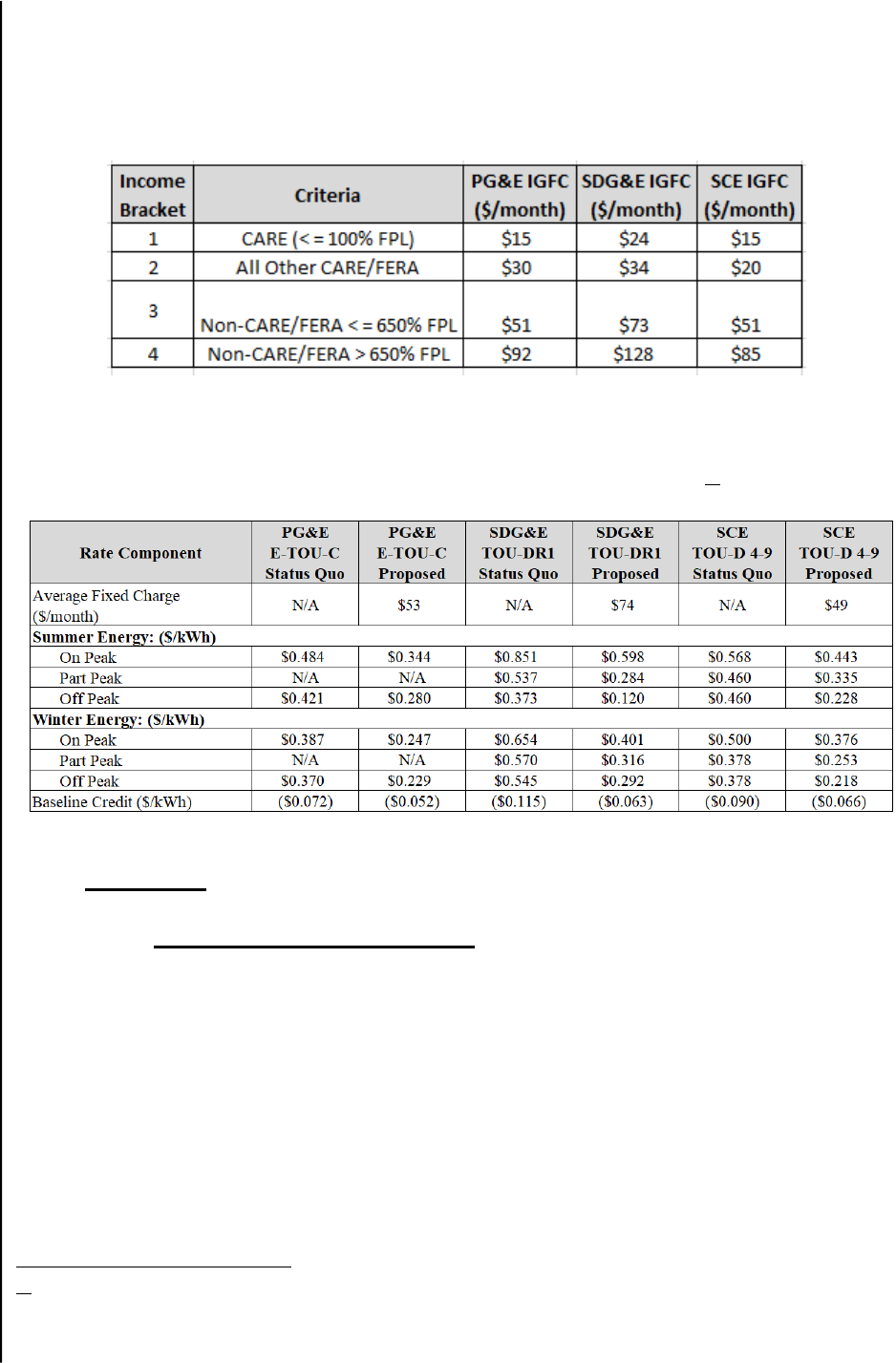

Table I-1

Illustrative Proposed IGFCs

Income

Bracket

Criteria PG&E

IGFC

($/month)

SDG&E

IGFC

($/month)

SCE

IGFC

($/month)

Average Fixed Charge $53 $74 $49

1 CARE (<= 100% FPL) $15 $24 $15

2 All Other CARE/FERA $30 $34 $20

3 Non-CARE/FERA <= 650%

FPL

$51 $73 $51

4 Non-CARE/FERA >650% FPL $92 $128 $85

6

1. Benefits of the Joint IOUs’ Proposals Compared to Current Residential 1

Rates 2

The Joint IOUs’ proposals provide several benefits compared to the current, primarily 3

volumetric, rate structures for the IOUs’ residential electric customers. These are described in 4

the sections below. 5

a) Improving Equity by Bringing Rates Closer to Cost of Service. 6

While the energy environment in California continues to evolve rapidly, the residential 7

rate structure for investor-owned, regulated utilities has become outdated and misaligned with 8

the new energy landscape. Unlike many utilities nationwide, and publicly-owned utilities within 9

California,

4

nearly all of the Joint IOUs’ costs to serve their residential customers are collected 10

through cent-per-kilowatt hour (kWh) volumetric rates, even though approximately two-thirds of 11

these residential costs are either fixed or do not fluctuate as customer usage increases or 12

decreases.

5

CPUC-approved residential rates also differ markedly from the rate schedules that 13

the Commission has approved for the Joint IOUs’ non-residential customers, which almost 14

universally include a separate fixed charge component to recover fixed costs on a non-volumetric 15

basis. 16

Existing residential rate design policies are under review in this proceeding, as they were 17

based on priorities that do not sufficiently align with a focus on improving the affordability of 18

electric service and more equitably recovering fixed costs, as the state seeks to expand beneficial 19

electrification. Whereas in the past, state law encouraged the CPUC to land on the side of rate 20

design resulting in higher volumetric rates, now the CPUC is required to balance, providing 21

appropriate price signals, both energy use reduction and energy use increases where such 22

4

For example, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) charges a $23.50 monthly fixed

charge on both Rate Schedule R (Fixed Rate) and Rate Schedule R-TOD (Residential Time-of-Day

Service). See https://www.smud.org/en/Rate-Information/Residential-rates.

5

Fixed revenue requirements as a portion of total residential revenue requirement, averaged across

IOUs.

7

increases would support GHG emissions reductions. This statutory change endorses the end of 1

the longstanding presumption that costs should be predominantly recovered through volumetric 2

rates for most residential customers. Instead, the priority is that volumetric price signals should 3

enable customers to make decisions that are better aligned with the State’s climate goals. 4

As the Joint IOUs continue to build and maintain necessary critical infrastructure to help 5

enable California’s energy transition, collecting residential customers’ fixed costs through 6

volumetric rates unfairly shifts fixed costs from lower to higher-use customers and 7

disincentivizes beneficial uses of electricity. Because nearly all the Joint IOUs’ fixed costs are 8

recovered through such volumetric prices, the price customers pay when they turn on their lights 9

is substantially higher than the marginal cost of providing that electricity. A recent paper from 10

the Energy Institute at Haas, UC Berkeley and Next 10 highlights that volumetric electricity rates 11

in California are two to three times the marginal cost of providing electricity.

6

Indeed, this 12

heavily volumetric residential rate design is a significant outlier when looking at residential rate 13

design across the U.S. as shown in Figure I-1 below. 14

6

Next 10 and Energy Institute at Haas, Designing Electricity Rates for an Equitable Energy Transition

(Feb. 2021), available at https://haas.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/WP314.pdf.

8

Figure I-1

Residential Rate Design Across the U.S.

7

Fixed and mandated public policy costs should be collected in fixed charges. The Joint 1

IOUs’ proposals address the inequity currently embedded in a primarily volumetric residential 2

rate structure, through the introduction of the IGFC. The proposed fixed charge levels in each 3

household Income Bracket have been set to yield an overall average fixed charge across all 4

household income levels that provides meaningful volumetric rate reductions while including an 5

appropriate portion of fixed system costs in the charge. The resulting IGFC revenues bring 6

volumetric rates closer to the actual cost of providing service to customers

8

– and provide relief 7

from high summer bills for high-usage households living in hotter climates. As described below, 8

lower volumetric rates also will be vital to enabling electric appliances/equipment/vehicles to 9

better support the transition to a decarbonized economy. 10

b) Addressing Affordability and Protecting Low-Income Customers. 11

Introducing even a traditional non-income-graduated fixed charge coupled with lower 12

volumetric rates would support California’s GHG policy goals and recover costs more equitably 13

7

Borenstein and Bushnell, National Bureau of Economic Research, Do Two Electricity Pricing

Wrongs Make a Right? Cost Recovery, Externalities, and Efficiency (Rev. Sept. 2018), available at

https://www.nber.org/papers/w24756.

8

See Chapter 2 Joint Rate Design Chapter.

9

than today’s rate structure, including producing lower bills for high users and higher bills for low 1

users, independent of their household income levels. However, the progressive nature of the 2

IGFC, mandated by AB 205 – with higher-income customers paying higher monthly fixed 3

charges than lower-income customers – also mitigates the adverse bill impacts that a traditional 4

fixed charge might have on lower-usage low-income customers. In particular, creating four 5

household Income Brackets, as opposed to three, allows the Joint IOUs to create an Income 6

Bracket available to our most economically vulnerable customers (those who fall under 100% of 7

the FPL), who will pay very modest monthly fixed charges while further benefitting from 8

significantly lower volumetric charges. 9

While the Joint IOUs have proposed to substantially reduce volumetric electricity rates 10

for all residential customers, the proposals also recognize many customers may not be able to 11

electrify in the near term. A key priority of the Joint IOUs’ proposals is to provide bill savings 12

for customers in Income Brackets 1-3 today. The IGFC proposals provide annual bill savings for 13

these customers, on average, without changing their energy consumption. 14

As shown in Figure I-2, on average, the Joint IOUs’ customers in Income Brackets 1-3 15

(lowest to moderate household income) are estimated to save between 4% to 21% per year, or 16

$89-$300 respectively, based the results of the E3 Public Tool (Public Tool) provided by the 17

Energy Division as part of this proceeding. 18

10

Figure I-2

Average Annual Percent Difference by Income Bracket

The Joint IOU proposals can achieve these savings for customers in Income Brackets 1-3 1

through the difference in the IGFC paid by Income Bracket 4 customers relative to Income 2

Bracket 1-3 customers. All customers can benefit from the lower volumetric rates but Bracket 1-3

3 customers pay a lower IGFC, allowing them to see immediate savings, on average, versus the 4

current status quo. In Income Bracket 4, customers with higher usage, such as that resulting 5

from electrification adoption, will also have lower bills than they would under today’s rate 6

structure, on average. 7

c) Encouraging Beneficial Electrification. 8

While California has made great strides in reducing GHG emissions in recent years, the 9

state must decarbonize twice as fast over the next two decades to meet its 2045 goals, as shown 10

in Figure I-3. 11

11

Figure I-3

California’s Decarbonization Accomplishments and Future Goals

9

Widespread electrification of customer homes and vehicles will be critical in accelerating 1

the pace of decarbonization. As shown in Figure I-4 below, based on 2020 emissions data, these 2

two sectors –-- transportation and buildings (residential and commercial) – represent nearly 50% 3

of California’s GHG inventory as reported. Customer adoption of beneficial electrification 4

technologies is essential to effectively reduce the greenhouse gas emissions currently associated 5

with these two sectors. 6

9

See California Air Resources Board (CARB) 2000 – 2020 GHG Inventory (2022 edition, by

economic sector), MMTCO

2

e = Million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Historical rate of reduction calculated from 2010 – 2020.

12

Figure I-4

Current California GHG Emissions Inventory Data

10

1

Powered by increasingly clean electricity, electrification will help replace traditional 2

fossil fuel technologies and their emissions with more climate-friendly, decarbonized 3

alternatives. Electric technologies produce fewer emissions than alternatives powered by fossil-4

fuels such as petroleum and natural gas; this environmental advantage of electricity will continue 5

to grow as greater amounts of carbon-neutral electric generation resources are added to the grid, 6

in compliance with state law. 7

As California looks to encourage customers to efficiently use more electricity, volumetric 8

rates that are significantly higher than the actual cost of providing that electricity create an 9

economic disincentive for the adoption of electrification technologies.

11

A fully electrified 10

10

See CARB, Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory - 2022 Edition. Building represents both

Commercial and Residential sectors. Other includes High Global Warming Potential Gases and

Recycling & Waste, available at https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/ghg-inventory-data.

11

Inclining-block tiered rates are especially problematic in this regard, charging artificially inflated

rates for usage in the upper tiers – precisely the tiers that customers who substitute electric appliances

for those powered by fossil fuels are likely to end up in.

13

home

12

is estimated to increase a customer’s electricity usage by at least 70% per month relative 1

to their prior usage.

13

While such increased usage reduces net greenhouse gas emissions, when 2

coupled with some of the highest volumetric rates in the U.S., a customer’s monthly electric bill 3

under current default residential rate designs would dramatically increase. Without reform, the 4

current volumetric rate design will jeopardize the state’s ability to decarbonize rapidly and could 5

put the achievement of our GHG reduction goals at risk. 6

In contrast, by significantly reducing volumetric electric rates – and thus the incremental 7

electric costs to customers due to installing clean electric appliances – the Joint IOUs’ proposals 8

will spur electrification adoption by making such appliances and electric vehicles (EVs) more 9

affordable versus the status quo rate structure. For example, when purchasing an EV, a critical 10

consideration is the electric rate the consumer would pay to charge it. Lower per-kWh rates have 11

been found to increase electric vehicle adoption.

14

Specifically, a 1 cent per kilowatt-hour 12

decrease in electric rates has been found to lead to about a 2 percent increase in electric vehicles 13

sales.

15

Similarly, lower electric rates have been correlated with higher electric heating adoption. 14

In fact, by lowering the volumetric rate to the marginal cost of energy, home heating 15

electrification was predicted to increase by one-third in California.

16

16

The Joint IOUs’ proposals make electrification more attractive than the status quo by 17

helping incentivize adoption through lower volumetric rates, while also avoiding cross subsidies 18

for those unable to adopt new technologies. As illustrated in Figure I-5, a Bracket 3 customer 19

12

A fully electrified home is assumed to have heat pump water heater, heat pump for space heating and

cooling, fully electrified appliances, and one EV.

13

The increase in electricity usage for a fully electrified home is calculated from the Public Tool

comparing a fully electrified home with one EV to a mixed-used fuel home with one gasoline

powered vehicle for a SCE Inland customer.

14

A. Soltani-Sobh, K. Heaslip, A. Stevanovic, R. Boswarth , D. Radivojevic, Analysis of the Electric

Vehicles Adoption over the United States, (2017), available at

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235214651730162X.

15

J. Bushnell, E. Muehlegger, D. Rapson, Do Electricity Prices Affect Electric Vehicle Adoption?,

(May 2021), available at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5f80503b.

16

Next 10 Paying for Electricity in California, at p. 21.

14

can expect to have a $1,614 annual savings relative to adoption of the same electrification 1

technologies under the current rate structure. For PG&E and SDG&E these savings would be 2

$1,771 and $1,929, respectively. 3

4

Figure I-5

SCE Example: Non-CARE Inland Income Bracket 3 Customer Energy Burden

Comparison

5

d) Promoting Bill Stability and Maintaining Strong TOU Price Signals. 6

With their reliance almost entirely on volumetric rates for recovering the costs of 7

providing service to residential customers, the Joint IOUs’ current residential rate structures have 8

an inherent challenge of causing month-to-month bill volatility.

17

But the Joint IOUs’ proposal, 9

17

This is particularly true if those rate schedules include tiered rates. With an inclining-block tiered rate

structure, an increase in a customer’s summer usage from June to July due to hotter July temperatures

15

by collecting a significant portion of residential revenue in fixed charges that do not vary by 1

month, will reduce this volatility. With lower volumetric rates, a customer’s bill increases from 2

one month to another due to a significant increase in usage (e.g., home cooling due to an extreme 3

weather event) will be much smaller. Similarly, the customer’s bill decreases from one month to 4

another due to a decrease in usage will be smaller as well. Thus, the Joint IOUs’ proposals will 5

lead to more stable bills as a result of collecting a greater portion of fixed costs in fixed charges 6

unaffected by usage swings. 7

The Joint IOUs’ proposals are designed to implement IGFCs in some way on all of their 8

residential rate schedules, including their TOU rates. While under the Joint IOU proposals, as 9

detailed in each IOU’s individual Rate Design Exhibits, average volumetric rates are 10

dramatically reduced over their current levels, robust differentials will remain between TOU 11

periods. This will continue to incentivize customers to shift load out of critical, higher-price 12

hours of the day through demand response, technology adoption such as battery storage, or other 13

energy efficiency efforts. 14

2. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Will Apply to All Residential Rate Schedules 15

If the IGFC is applied unevenly, where default rate schedules have an IGFC while 16

existing electrification rates do not, it would likely lead to rate self-selection that would 17

compromise the benefits achieved by the IGFC. Specifically, it would set up an arbitrage 18

opportunity through which customers who would be adversely impacted on schedules with 19

IGFCs could, instead, switch to one of the optional rates without an IGFC to avoid paying their 20

share of fixed costs. This would undercut the IGFC’s goals of equity and rate affordability, 21

especially for the most economically disadvantaged customers. 22

It is still permissible under AB 205 for the Commission to adopt different sets of income-23

graduated fixed charges for different residential rates. For example, the Commission might 24

can easily lead to disproportionately larger increases in the customer’s bill due to usage moving from

a lower-price tier to a higher-priced one.

16

approve somewhat higher IGFCs for the current electrification rates that already have some level 1

of fixed charge, than it adopts for other more standard rates because doing so would better 2

support the state’s decarbonization efforts. Therefore, the Joint IOUs’ proposals recommend that 3

all of their residential rates, including TOU rates, must have at least the same IGFC as the default 4

rates. The IGFCs will not adversely affect the price signals customers see, to inform them of the 5

varying costs during different periods of the day – they merely reduce the total revenue collected 6

from volumetric charges but can still be designed to maintain cent per kWh price differentials 7

between peak and off-peak periods that appropriately reflect underlying marginal costs and 8

continue to incentivize load shifting. 9

3. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Are Consistent with Rate Design Principles. 10

While the revisions to the CPUC’s rate design principles (RDPs) had not been finalized at 11

the time this testimony was written,

18

the draft of such revisions (with which the Joint IOUs 12

largely agree) affirm that significant changes in residential rate design are necessary, including to 13

reflect the addition of decarbonization through electrification as a major state policy goal for 14

achieving GHG reductions. The Joint IOUs intend to provide a full assessment of all proposals, 15

according to the final rate design principles, in Reply Testimony, but some changes to the RDPs 16

appear to already be certain enough to warrant comment now. 17

In particular, the change in RDP 4 to “Rates should encourage economically efficient (i) 18

use of energy, (ii) reduction of GHG emissions, and (iii) electrification”

19

reflects a major shift in 19

rate design priorities. In prior rate designs, the reduction of electricity use through conservation 20

and energy efficiency was prioritized regardless of whether that was environmentally 21

responsible. The percentage of non-GHG emitting resources in the current statewide generation 22

18 On March 17, 2023, the assigned ALJ issued the Proposed Decision Adopting Electric Rate Design

Principles and Demand Flexibility Design Principles (RDP Proposed Decision). The Proposed

Decision included Attachment A, the Electric Rate Design Principles, Demand Flexibility Design

Principles, and explanations for each.

19

RDP Proposed Decision, Attachment A, p. 2.Q

.

17

mix is much higher now, over 52%

20

non-GHG emitting (i.e., carbon free) resources, compared 1

to 2011 when the current rate design principles were adopted. The state’s renewables policies 2

ensure that this trend will only continue. The driving force of state policy now points to 3

increased electric use through beneficial electric technologies (like EVs, heat pump space 4

cooling and heating, heat pump water heaters, induction ranges, and battery storage). This shift 5

has major ramifications for rate design by shifting its emphasis from the efficient use and 6

conservation of electricity to the efficient increased use of electricity in order to facilitate the 7

energy transition, while improving affordability of household energy consumption. The 8

proposed revision to the language in RDP 2, (“Rates should be based on marginal cost”)

21

) and 9

RDP 8 (“Rates should be technology-neutral and avoid cross-subsidies, unless the cross-10

subsidies appropriately support explicit state policy goals”)

22

indicate that rates should provide 11

volumetric price signals as close to marginal costs as possible, while balancing other rate design 12

principles. Today’s rates feature volumetric price signals that are significantly higher than the 13

marginal costs in low-cost hours, as shown in the Rate Design chapter (Table II-4), which can 14

discourage the voluntary adoption of electrification technologies. The shift towards more fixed 15

cost recovery through fixed charges can bring residential rates to a point where technology-16

neutral rates that avoid or minimize cross-subsidization are achievable. 17

Additionally, just as advancements in technology and policy have led the reformed rate 18

design principles expected in this proceeding, updated principles should include the ability to 19

adapt to continuous changes as California’s landscape evolves. 20

20

California Energy Commission, Annual Power Content labels for 2021 available at

https://www.energy.ca.gov/programs-and-topics/programs/power-source-disclosure/power-

content-label/annual-power-content-2.

21

RDP Proposed Decision, Attachment A, p. 1.Q

.

22

RDP Proposed Decision, pp. 2-3.Q

.

18

C. The Joint IOUs’ Proposals Should be Adopted as Soon as Possible. 1

California’s current residential rate design must be updated as soon as possible. This is 2

because the Joint IOUs’ lowest income customers are experiencing affordability challenges 3

today through volumetric electricity rates. Approximately two-thirds of costs serving residential 4

customers that are collected in volumetric rates today do not fluctuate as customer usage 5

increases or decreases, resulting in volumetric rates that are significantly higher than the 6

marginal cost to serve customers. The result is a regressive structure where lower-income 7

households contribute a much larger share of their income than higher income customers. As the 8

Joint IOUs continue to build and maintain the necessary infrastructure to green the grid, 9

collecting these fixed costs through volumetric rates will further exacerbate these affordability 10

and equity issues. 11

Further, high volumetric rates increase the cost of electrifying customer homes and 12

vehicles, a critical change that must occur for the state to meet its aggressive, but necessary, 13

climate mandates. As stated above, the State must decarbonize faster than it has over the past 14

decade, but the current outdated default rate structure is an impediment to achieving these goals. 15

Due to these reasons, the Joint IOU proposals should be implemented as soon as practicable 16

through the Joint IOUs’ implementation plan described in Chapter 4. 17

D. Income Verification Should Be Performed By State Agencies and Not The IOUs 18

The Joint IOUs have long administered programs like CARE and FERA, which provide 19

discounts to low-income customers. However, these are opt-in programs where eligible 20

customers voluntarily give the IOUs information regarding income. This income is not verified 21

but is subject to a potential audit. 22

The IGFC will be fundamentally different. The Joint IOUs are not aware of any other 23

fixed charge that is income differentiated based on all levels of household income and that is 24

mandatory for all. Consequently, millions of households will need to be categorized into fixed 25

charge income brackets based on household income and verified to ensure accuracy and billing 26

19

integrity. Successful implementation will require customer trust and assurance of confidentiality 1

in the process. 2

As discussed more fully in Chapter 3 (Income Verification), a state agency, potentially 3

with the assistance of a Third-Party administrator, would be best situated to take on the complex 4

income verification and bracket assignment work that will be necessary to implement the IGFC. 5

The Joint IOUs believe the Commission is the state agency likely in the best position to take on 6

this role, overseeing a Third Party. The Commission has experience in a somewhat similar role 7

in relation to the California LifeLine program, for which a “TPA” (Third-Party administrator) 8

has performed income verification/eligibility certification under the Commission’s supervision.

23

9

A state agency like the Commission is in a much better position to access the financial data 10

necessary for Income Bracket placement, as well as to manage ongoing updates, customer 11

appeals, and other implementation issues. The Commission is also well-placed to perform this 12

role because it is giving the Joint IOUs direction in this proceeding and AB 205 specifically tasks 13

the Commission with authorizing the residential income-graduated fixed charge. 14

In contrast, the Joint IOUs are not well-situated to perform income verification. 15

Verifying the state’s ~12 million electricity customers served by the Joint IOUs would require a 16

significant and costly business expansion for each IOU to separately build out new capabilities. 17

Building processes and adding resources to perform a wholly new set of functions as well 18

handling any customer appeals relating to income level placement, would impose substantial 19

administrative burden and cost on the Joint IOUs, ultimately paid by our customers. 20

Moreover, income verification also implicates cybersecurity, customer privacy and 21

consumer protection issues. California law includes significant privacy protections,

24

including 22

23

See D.05-04-026, p. 26 (concluding that income certification/verification for Lifeline Program should

be performed by a TPA “under the direction of a state agency, namely the Commission”).

24

See, e.g., Civ. Code 1798.1 (“the right to privacy is a personal and fundamental right protected by

Section 1 of Article I of the Constitution of California and by the United States Constitution and [] all

individuals have a right of privacy in information pertaining to them).”

20

through the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA).

25

The Commission also has 1

endorsed privacy protections in its decisions.

26

Privacy and data protection concerns have 2

increased among the public at large given large data breaches in recent years, among other 3

events. Additionally, processes will need to be established to access various sources of income 4

data among state agencies, to maximize reliable household income data for these purposes. 5

In light of these complexities and challenges for income verification, a state agency 6

(potentially with Third Party support) leveraging and building upon existing capabilities and 7

experience will be best positioned to effectively manage needed income verification for the 8

IGFC. The Joint IOUs thus propose a framework modeled on the structure of the 9

telecommunications LifeLine program’s Third Party administration with CPUC supervision, so 10

that income verification is performed through a state agency, without undermining rate 11

affordability. Additionally, if authorized by legislation, it would be most appropriate for income 12

verification activities to be funded by the state rather than electricity customers, consistent with 13

funding provided for other societally beneficial activities administered by state agencies. 14

E. Robust Marketing, Education, and Outreach Will be Required 15

The IGFC rate structure will substantially shift how residential customers pay for 16

electricity service in the future. A robust ME&O plan will be required to provide customers with 17

early awareness of the change, help customers understand bill impacts, and highlight why reform 18

is needed. The Joint IOUs will use various customer communication channels to form a holistic, 19

integrated education and outreach campaign to support IGFC implementation. Channels 20

envisioned include direct-to-customer messaging, broad customer outreach, IOU-owned and paid 21

25

The CCPA (Civ. Code §§ 1798.100–1798.199.100) provides for various rights, including the rights

to: know about personally identifiable information (PII) a business collects and how it is used and

shared; delete personal information (with some exceptions); opt-out of the sale or sharing of personal

information; correct inaccurate personal information; and limit the use and disclosure of sensitive

personal information.

26

See, e.g., D.11-07-056, at p. 130, Finding of Fact 1 (FOF) (endorsing Fair Information Practices

(FIPs) including “data minimization” principle).

21

channels, and community outreach. The Joint IOUs’ education materials will be informed by 1

customer research. We expect it will focus on how the IGFC will make rates more equitable 2

overall while supporting the State’s goal of making beneficial electrification technologies more 3

affordable, by lowering volumetric rates. The Joint IOUs recognize additional customer input 4

will be needed to properly meet customer education needs. The Joint IOUs plan to conduct 5

additional research in 2023 to continue to learn from customers the preferred and most effective 6

messaging and approach to IGFC education. The Joint IOUs’ detailed ME&O plan is discussed 7

in more detail in Chapter 5 included in this testimony. 8

F. Conclusion 9

While California’s energy environment has changed rapidly in recent decades, its 10

residential rate design continues to collect the majority of fixed and variable utility costs through 11

volumetric rates. As a result, electricity rates are substantially higher than the marginal cost of 12

providing that electricity. The Joint IOUs’ proposals modernize California’s residential rate 13

structure by providing a more affordable and equitable path forward. The chapters that follow 14

explain how the Joint IOUs’ proposals accomplish these goals and we respectfully encourage the 15

Commission to accept these proposals to ensure the transition to income-graduated residential 16

fixed charges is as smooth and successful as possible.17

22

II. 1

RATE DESIGN 2

A. Introduction 3

1. Summary of Proposals 4

The Joint IOUs propose to add Income Graduated Fixed Charges (IGFCs) to all of their 5

residential rate schedules, with limited exceptions.

27

Most of the Joint IOUs’ residential 6

schedules will receive the same, four-bracket fixed charges, with the low-income fixed charges 7

set at the household Income Brackets shown in Table I-2. For policy reasons, the IOUs’ 8

proposed fixed charge Income Brackets do not encompass all of each utility’s respective fixed 9

costs. By carving out an amount of the total fixed costs from the current artificially high 10

volumetric rates, the California Public Utilities Commission (Commission or CPUC) will make 11

significant progress to support affordability and increased bill stability. It also supports 12

decarbonization by removing the disincentive for residential customers to add beneficial electric 13

end-uses needed to meet the state’s greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goals. 14

The Joint IOUs’ IGFC proposals are intended to maintain customer choice and improve 15

equity, while providing greater bill stability and promoting beneficial electrification. The Joint 16

IOUs’ Illustrative IGFC proposed fixed charges and rates are shown below on Tables I-2 and I-3. 17

In this proposal, the Joint IOUs are seeking approval of: 18

Fixed cost categories, which result in class average monthly

28

fixed charges of: 19

o PG&E: $53/month 20

27

All residential whole-home rate schedules should have at least the same level of IGFC in order to

avoid customer rate switching and IGFC avoidance through rate arbitrage. However, non-IGFC fixed

charges for separately metered EV rates may be appropriate and are addressed in IOU specific Rate

Design testimony exhibits.

28

Operationally, these fixed charges would be charged to customers on a dollar-per-day basis.

However, the IOUs are presenting these fixed charges on a per-month basis for reference.

23

o SDG&E: $74/month, including approval of its new proposed rate component, the 1

Electrification Incentive Adjustment (EIA) 2

o SCE: $49/month; 3

IGFCs on the following residential rate schedules: 4

o PG&E rate schedules: E-1, E-TOU-C, E-TOU-D, EV2-A, E-ELEC 5

o SDG&E rate schedules: DR, TOU-DR1, TOU-DR2, EV-TOU-2, DR-SES, EV-6

TOU-5, TOU-DR, and TOU-ELEC 7

o SCE rate schedules: TOU-D 4-9, TOU-D 5-8, Schedule D 8

Considerations for including higher IGFCs for certain residential rate schedules that 9

currently have fixed charges: 10

o PG&E’s Schedule E-ELEC 11

o SDG&E’s Schedules EV-TOU-5 and TOU-ELEC; 12

o SCE’s Schedule TOU-D-PRIME 13

Reduction of non-CARE average volumetric kWh rates as described in individual 14

IOU exhibits: 15

o PG&E: From $0.34/kWh to $0.22/kWh 16

o SCE: From $0.36/kWh to $0.24/kWh 17

o SDG&E: From $0.47/kWh to $0.27/kWh 18

Elimination of the Minimum Bill. 19

24

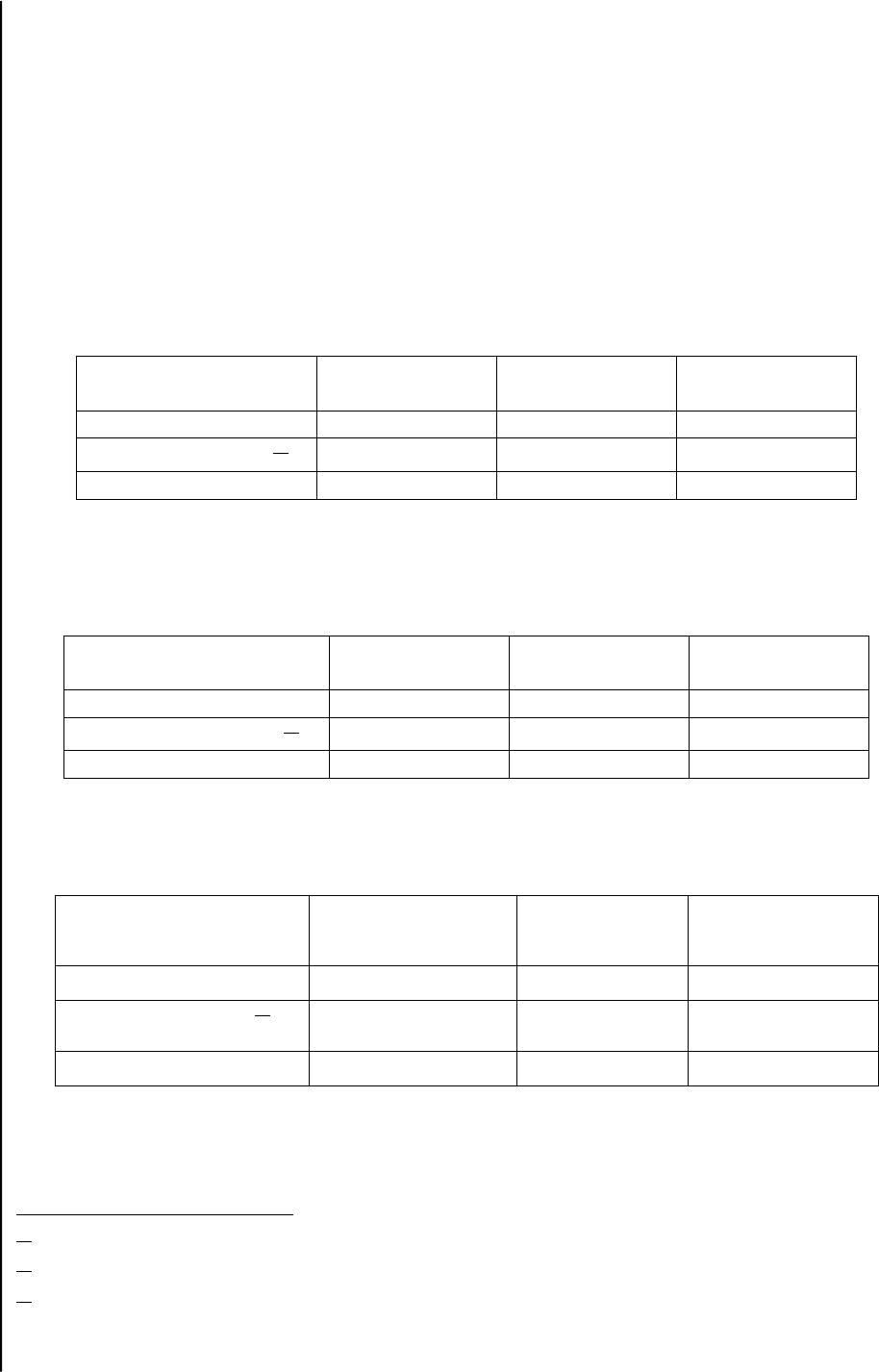

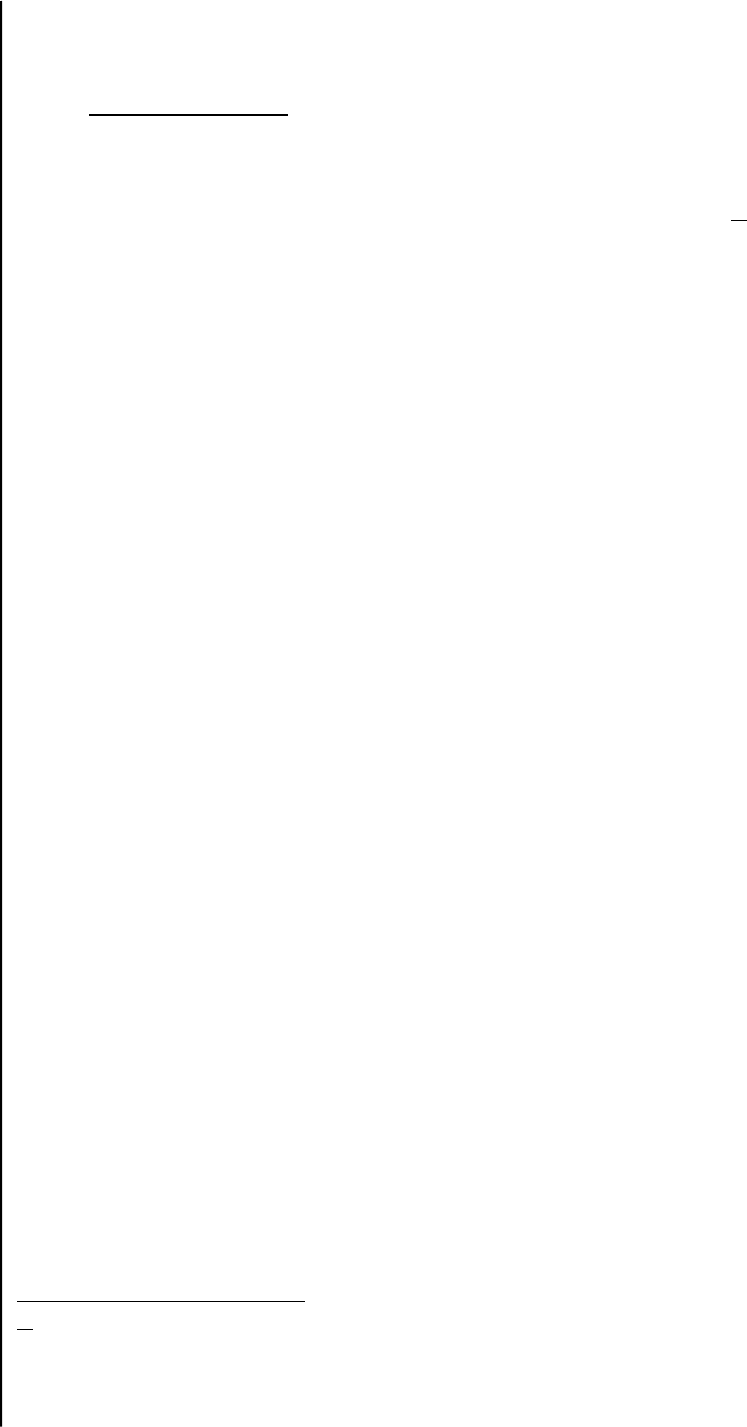

Table II-2

Illustrative Proposed IGFCs

Table II-3

Illustrative Summary of Impacts to Default Rates

29

B. Background 1

1. Recent Rate Design Policy Issues 2

The impetus for Track A (IGFC) of this proceeding stems from Assembly Bill (AB) 205, 3

which was passed on June 29, 2022, and chaptered after being signed into law by Governor 4

Newsom on June 30, 2022. The Commission has previously considered but declined to adopt 5

fixed charges for residential customers, and instead, required the three electric IOUs to 6

implement residential minimum bills. The Joint IOUs provide a brief history of how the 7

Commission’s thinking on residential fixed charges has evolved over time and emphasize the 8

29

Status Quo rates are the model calculated counterfactual rates, not current actual rates.

25

importance of adopting IGFCs that apply equitably to all customers and meaningfully reduce 1

volumetric rates in the instant proceeding. Substantive rate reform is critical for California to 2

reach its GHG reduction and climate goals. 3

From 2013 until AB 205 was passed, the previous statute (Public Utilities Code Section 4

739.9) included a cap that limited residential fixed charges to approximately $10/month for non-5

CARE customers and $5/month for CARE customers.

30

AB 205 removed this cap and required 6

the CPUC to approve a compliant IGFC structure for default residential rates by July 1, 2024.

31

7

The Commission has previously considered default residential fixed charges in various 8

proceedings but the Energy Division IGFC Guidance for this proposal states that parties are not 9

bound by these prior Commission decisions.

32

10

Nonetheless, as a foundation, the Joint IOUs provide a brief background of the history of 11

residential fixed charge proposals in California and the Commission’s current direction regarding 12

historical determinations about residential fixed charges. The Joint IOUs proposed fixed charges 13

approximately ten years ago in the Residential Rate Reform Rulemaking (R.) 12-06-013 14

(RROIR). While Decision (D.) 15-07-001 set a multi-year glidepath to consolidate and narrow 15

the tier differentials in effect at that time, the Commission declined to adopt a default residential 16

fixed charge, stating that it was not appropriate to adopt a fixed charge at the same time as 17

residential customers were being defaulted to time-of-use (TOU) rates.

33

The Joint IOUs were 18

directed to concurrently file rate design window (RDW) applications by January 1, 2018, which 19

could include proposals for default residential fixed charges.

34

D.15-07-001 additionally stated 20

that the Joint IOUs should, separately from the Residential Rate Reform OIR (R.12-06-013, 21

30

AB 327 (Reg. Sess. 2013-2014), Pub. Util. Code § 739.9(f), which also provided for an annual

Consumer Price Index increase to these base capped fixed charge levels, starting in 2015.

31

AB 205 (Reg. Sess. 2021-2022).

32

Administrative Law Judge’s Ruling Providing Guidance for Phase 1 Track A Proposals and

Requesting Comments on a Consulting Services Proposal (Jan. 17, 2023), Attachment 1, R.22-07-

005, Phase 1 Track A: Income-Graduated Fixed Charge Guidance Memo.

33

D.15-07-001, at p. 328, Conclusion of Law (COL) 17.

34

D.15-07-001, at p. 327, Ordering Paragraphs (OP) 9-11.

26

RROIR), “in their individual GRC Phase 2 proceedings, … work to identify customer-related 1

fixed costs for purposes of calculating a fixed charge.”

35

2

Within PG&E’s 2017 GRC Phase 2,

36

the Commission established a separate track 3

(Fixed Charge Track) to adopt categories of fixed costs that could be included in a residential 4

default fixed charge. The final decision in the Fixed Charge Track, D.17-09-035, adopted an 5

extremely narrow definition of what costs could be included in the default residential fixed 6

charges proposed in A.17-12-011.

37

That narrow definition

38

would have limited the Joint IOUs’ 7

non-CARE fixed charges to approximately $7.10/month for PG&E,

39

$8.84/month for 8

SDG&E,

40

and $6.68/month for SCE.

41

Using such a definition today would do little to reduce 9

volumetric rates and incentivize beneficial electrification because volumetric rates would be 10

reduced by less than $0.02/kWh. 11

In 2021, the Commission adopted a final decision in PG&E’s 2020 GRC Phase 2 (A.19-12

11-019) that reversed its stance on categories of costs that may be recovered in default residential 13

fixed charges and wipes the slate clean when considering the appropriate manner for designing 14

residential fixed charges.

42

In D.21-11-016, the CPUC also adopted PG&E’s new optional 15

“electrification” rate (E-ELEC), finding that: (1) “[t]he findings and conclusions in D.17-09-035 16

should be applied only in the context of A.16-06-013”

43

, and (2) “any future proposals for a 17

35

Id., at p. 6.

36

A.16-06-013, Application of Pacific Gas and Electric Company to Revise its Electric Marginal Costs,

Revenue Allocation and Rate Design.

37

Administrative Law Judge’s Ruling Consolidating Proceedings (Jan. 25, 2018), consolidated A.17-

12-011, A.17-12-012, and A.17-12-013.

38

D.17-09-035 would have limited costs recovered in a fixed charge to certain marginal customer

access costs using the “minimum cost approach”, which includes costs for only the “smallest” type

customer. See, D.17-09-035, at p.33.

39

See, PG&E Rate Design Window 2018 Supplemental Testimony, Fixed Charge Proposal in Phase III,

A.17-12-012, at p. 1-4.

40

See, SDG&E Prepared Supplemental Testimony of Jeff P. Stein, A.17-12-013, at p. JS-3.

41

See, SCE Amended Supplemental Testimony on Impact of Federal Tax Legislation on Proposed

Rates and Fixed Charges, A.17-12-011, at p. 2.

42

D.21-11-016, at p. 113.

43

D.21-11-016, at p. 165, COL 32.

27

default residential fixed charge or optional residential fixed charge (as in this case) should be 1

able to proceed without the need to comply with cost category and EPMC [Equal Percent of 2

Marginal Cost] determinations made in a since-closed proceeding that failed to make a 3

determination concerning a residential fixed charge on the merits.”

44

Additionally, it is worth 4

noting that the Commission determined the adopted settlement on PG&E’s new E-ELEC 5

(“Electric Home”) rate, which included a residential fixed charge, was “intended to further state 6

policy goals related to decarbonization and therefore has a particular policy purpose that may 7

justify any dissonance with previous Commission decisions regarding the application of EPMC 8

to residential fixed charges.”

45

9

With these findings in mind, there is no reason to limit fixed charges to a certain level or 10

hold to prior precedent. While parties may look to previous Commission decisions for reference 11

and historical context, party proposals that cite to D.17-09-035 as a reason to limit fixed charges 12

to a certain level should be dismissed, as the Commission has stated that D.17-09-035 does not 13

hold precedential value outside of A.16-06-013.

46

Basing IGFC proposals on D.17-09-035 14

would make little sense in this context anyway, as the average IGFC must be large enough to 15

result in a sufficiently lower volumetric energy rate, and D.17-09-035 would limit volumetric 16

rate reduction to approximately $0.02/kWh. 17

It is important that an IGFC floor apply to all customers. Application of the IGFC to all 18

residential rates, including optional “electrification rates” currently offered by each large IOU, 19

will ensure fair treatment for all customer types and provide equal incentive for all customers to 20

electrify. If the IGFC were instead applied selectively, where some residential rate schedules 21

would have a fixed charge while others did not, this would provide an opportunity for customers 22

who would be adversely impacted on schedules with IGFCs to instead take service on one of the 23

optional rates without an IGFC, to avoid paying the IGFC. 24

44

Id., at p. 114.

45

D.21-11-016, at p. 114.

46

Id.

28

It is still permissible under AB 205 for the Commission to adopt different sets of IGFC’s 1

for different residential rates. For example, the Commission might approve somewhat higher 2

IGFCs for PG&E’s Schedule E-ELEC, SCE’s TOU-D-PRIME, or SDG&E’s EV-TOU-5 and 3

TOU-ELEC rates than it adopts for other more standard rates, because doing so would better 4

support the state’s decarbonization efforts. Therefore, the Joint IOUs’ proposals recommend that 5

all residential rates, including optional rates, must have at least the same minimum IGFC Income 6

Brackets as the default rates. 7

The Commission should adopt appropriate fixed charges for all residential customers, and 8

not delay implementing an IGFC for certain rate schedules, because doing so would result in a 9

loophole that could allow higher income customers to receive a lower fixed charge if they mass 10

migrate to rates with delayed (or no) IGFCs. Although simultaneous implementation across rates 11

might take more up-front time, it avoids the pitfalls of mass voluntary migration to the lowest 12

possible fixed charge. 13

2. Next 10 Research on Potential Fixed Charges 14

Academic research by Next 10 Research and the Energy Institute at the UC Berkeley 15

Haas School of Business (Next 10/Berkeley Haas) played a key role in inspiring the conceptual 16

development of AB 205. Specifically, two Next 10/Berkeley Haas reports released in 2021 and 17

2022, detail concerns about the inequity of the current residential rate structure. These reports 18

suggest several methods of reform that would: (1) improve customer equity by making rates 19

more progressive, and (2) more closely align volumetric rates with marginal costs, which would 20

serve to incent widespread adoption of beneficial electrification technologies needed to achieve 21

decarbonization that meets state climate and GHG reduction goals. The Joint IOUs describe 22

these two reports in detail below. 23

29

On February 23, 2021, Next 10/Berkeley Haas released a report titled “Designing 1

Electricity Rates for An Equitable Energy Transition” (2021 Report).

47

This report used 2

historical data from the Joint IOUs to show that the price of electricity in the Joint IOUs’ service 3

territories is two to three times higher than the actual cost to produce and distribute the electricity 4

provided, and this results in electricity rates that disproportionately harm lower income 5

electricity customers.

48

6

The 2021 Report opines that recovery of fixed costs within the volumetric charge is 7

“quite regressive” and suggested options for reducing the volumetric rate, including non-income 8

differentiated fixed charges or shifting cost recovery of programs and policies to the state budget. 9

It acknowledges that even a non-income differentiated fixed charge would bring significant 10

efficiency benefits.

49

However, given potential concerns with both approaches, the 2021 Report 11

recommends a progressive fixed charge structure for residential customers.

50

The 2021 Report 12

determined that “[a]n economically efficient volumetric price will recover some amount of 13

revenue, but it will be substantially less than the total revenue requirement for the California 14

IOUs.”

51

It also considered what electricity rates might look like if their structure were as 15

progressive as California's income tax and sales taxes, and recommended structures in which 16

low-income customers would not be made worse off by rate reform. It further recommended that 17

the state, not the utilities, be the income verifying entity, as the state already has income tax 18

information. The 2021 Report also acknowledged that the utilities do not have the infrastructure 19

47

Next 10 and Energy Institute at Haas, Designing Electricity Rates for An Equitable Energy Transition

(hereinafter Next 10, 2021 Report), (Feb. 23, 2021), available at

https://www.next10.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Next10-electricity-rates-v2.pdf.

48

Next 10, 2021 Report, at p. 4.

49

Next 10, 2021 Report, at p. 3. While the report also expresses concern that a non-income

differentiated fixed charge would also be regressive, even in a pre-AB 205 context any fixed charge

implemented by the IOUs would at least include income differentiation through the existing CARE

and FERA programs.

50

Next 10, 2021 Report, at pp. 30-34.

51

Next 10, 2021 Report, at p. 35.

30

in place to verify incomes of all residential customers and that any utility-run income-1

verification system without direct cooperation from other state agencies would be problematic.

52

2

The 2021 Report discussed a theoretical structure, stating that the dollar amount of a 3

uniform fixed charge necessary to fully eliminate the cost recovery gap (if all account holders 4

were charged the same monthly fee, based on 2019 rates), would be $74.02 for PG&E, $58.80 5

for SCE, and $70.07 for SDG&E.

53

Rates have increased since 2019, so the Report’s monthly 6

figures would have been higher had they been based on 2023 effective rates. Figure II-6 below 7

shows theoretical 2019 fixed charges for PG&E if the structure were as progressive as income 8

tax or sales tax.

54

Under the 2021 Report's illustrative structure, households making greater than 9

$150,000 annually would be required to pay fixed charges of $150 per month or higher. 10

11

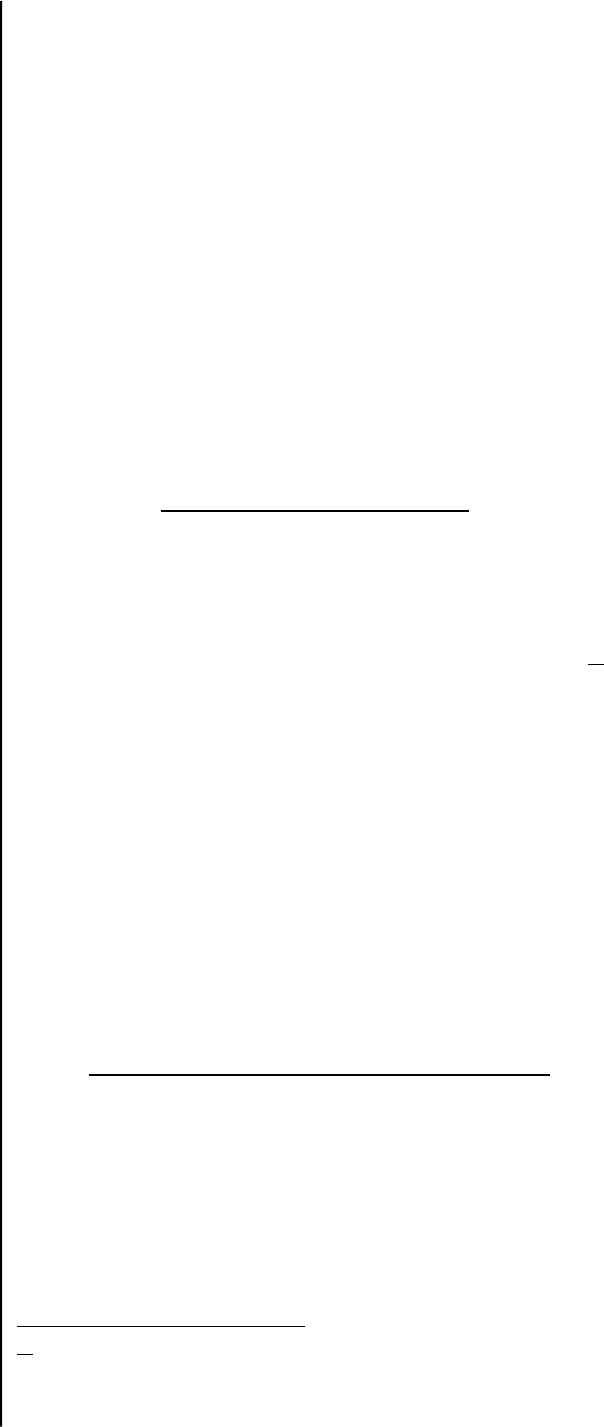

Figure II-6

2021 Next 10 Report Theoretical Fixed Charges - PG&E

12

52

Next 10, 2021 Report., at p. 38.

53

Id., at p. 40.

54

As stated in the Next 10/Berkeley paper, although sales tax applies equally to purchases made by

customers of any income level, wealthier customers typically pay more sales tax because they make

more purchases.

31

On September 22, 2022, Next 10/Berkeley Haas released a follow-on report titled 1

“Paying for Electricity in California: How Residential Rate Design Impacts Equity and 2

Electrification” (2022 Report).

55

This second report, which built on the 2021 Report, and 3

continued to use historical IOU data determined that the costs of programs and policies that go 4

beyond the cost of producing and distributing electricity are now the main driver of retail 5

electricity price increases. These added costs, which drive up the price per unit of volumetric 6

energy, threaten the state’s climate goals by disincentivizing electrification of buildings and 7

vehicles. In other words, separating out fixed costs from the currently combined, artificially high 8

volumetric rate, and instead recovering them in a separate fixed charge line item removes a 9

disincentive to electrification by reducing customers’ volumetric electric rate component. The 10

2022 Report also explored in detail how these higher costs disproportionately affect lower-11

income households, as higher energy bills in a lower-income household are a higher percent of 12

total income. Next 10/Berkeley Haas calculated what they refer to as “residual cost burden,” or 13

the difference between the amount the customer pays on their bill and the incremental cost to the 14

utility of providing that household with power.

56

The 2022 Report concluded that recovering 15

this residual cost burden in volumetric rates raises the annual operating cost of electrification 16

technologies, referred to as the “electrification cost premium.” The current structure of 17