Proceedings of the 48

th

Annual

Macromarketing Conference

With a Little Help from Our Friends:

The Value of Connection and Macromarketing Research in

Addressing Critical Global Issues

2

Photo by Timothy Eberly on Unsplash

Seattle, Washington, U.S.A.

June 19 – June 22, 2023

Conference Co-Chairs*

Claudia Dumitrescu, Central Washington University

Renée Shaw Hughner, Arizona State University

*Listed in alphabetical order; both co-chairs contributed equally to the conference organization

and success.

Copyright Statement

The Macromarketing Society Inc. does not take copyright for papers appearing in the proceedings. The

copyright of all papers or abstracts in the proceedings remains that of the authors’.

Published by the Macromarketing Society, Inc. in 2023

ISSN 2168 - 1481

3

Thank You!

The 2023 Macromarketing Conference Co-Chairs would like to thank the track chairs, authors,

panelists, moderators, reviewers, the support teams of the Macromarketing Society, Central

Washington University, and Arizona State University. Their hard work, contributions, and

professionalism were key to the creation and administration of the first in-person

Macromarketing Conference since 2019, when COVID-19 changed the world.

Track Chairs

Track Name

Chairs/Co-Chairs

Email Addresses

Cultural (Digital)

Phenomena, Markets and

Marketing Systems

Ingrid Becker

Michaela Haase

Ingrid.Becker@unisg.ch

Michaela.Haase@fu-berlin.de

Ethics, Equity, and Social

Justice

Ann-Marie Kennedy Cathy

McGouran

Nicky Santos

Ann-Marie.Kennedy@canterbury.ac.nz

C.Mcgouran@liverpool.ac.uk

NicholasSantos@creighton.edu

Externalities

Shoaib M. Farooq Padela

Shoaib.Sho[email protected].nz

Food Marketing

Claudia Dumitrescu

Renée Shaw Hughner

Claudia.Dumitrescu@cwu.edu

Renee.Hughn[email protected]

Globalisation,

(Neo)Colonialism, and

Marketing

Marcus Wilcox Hemais

Olga Kravets

Marcus.Hemais@iag.puc-rio.br

Olga.Kravets@rhul.ac.uk

Historical Research in

Marketing Track

Francisco Conejo

Jayne Krisjanous

Terrence H. Witkowski

Francisco.Conejo@incae.edu

Jayne.Krisjanous@vuw.ac.nz

Terrence.Witkowski@csulb.edu

Macromarketing

Measurements and Methods

Francisco Conejo

Anthony Samuel

Ben Wooliscroft

Francisco.Conejo@incae.edu

Samuela3@cardiff.ac.uk

Ben.Wooliscroft@aut.ac.nz

Macromarketing Pedagogy

Stanley J. Shapiro

Julie V. Stanton

Stanley_Shapiro@sfu.ca

JVS11@psu.edu

Quality of Life and

Wellbeing

Ahmet Ekici

Alexandra Ganglmair-

Wooliscroft

Ekici@bilkent.edu.tr

A.Ganglmair@massey.ac.nz

Revisiting Government’s

Role in Provisioning:

Observations through a

Macromarketing Lens

Stanley J. Shapiro

Julie V Stanton

Stanley_Shapiro@sfu.ca

JVS11@psu.edu

Social Conflicts and Market

Dynamics

Andrés Barrios

Cliff Shultz

Andr-Bar@uniandes.edu.co

CJS2@luc.edu

Social Marketing for Global

Change: Aligning Social

Marketing with the

UNSDGs

Christine Domegan

Ann-Marie Kennedy

Josephine Previte

Christine.Domegan@universityofgalway.ie

Ann-marie.Kennedy@canterbury.ac.nz

J.Previte@business.uq.edu.au

Sustainability and Climate

Change

Sabrina Helm

Joya Kemper

Victoria J. Little

4

Reviewers

Andrés Barrios Fajardo

Sabrina Helm

Ronan Quintão

Denise Barros

Marcus Wilcox Hemais

Don Rahtz

Ingrid Becker

Sujit Raghunathrao Jagadale

Michelle Renton

Raymond Benton

Wodajo, Kebene Kejela

João Felipe Sauerbronn

Helene Cristini

Joya Kemper

Renée Shaw Hughner

Francisco Conejo

Ann-Marie Kennedy

Anthony Samuel

Nik Dholakia

Florian Krause

Marcos Santos

Christine Domegan

Olga Kravets

Nicky Santos

Claudia Dumitrescu

Jayne Krisjanous

Joao Felipe Sauerbronn

Ahmet Ekici

Vimala Kunchamboo

Stanley J. Shapiro

Karin Ekström

Vicki Little

Clifford J. Shultz

Zeynep Ertekin

Cathy McGouran

Julie V. Stanton

Hossein Eslami Dizeje

Dario Miocevic

Emma Surman

Shoaib M. Farooq Padela

Márcio Müller

Jeff Wang

Míriam Ferreira

Edna Ndichu

Janine Williams

Alexandra Ganglmair-Wooliscroft

Mark Peterson

Terrence H. Witkowski

Stephanie Geiger Oneto

Olavo Manuel Reis Santos Pinto

Ben Wooliscroft

Mario Giraldo

Pia Polsa

Cagri Yalkin

Michaela Haase

Josephine Previte

5

Table of Contents

CULTURAL (DIGITAL) PHENOMENA, MARKETS AND MARKETING SYSTEMS TRACK................. 10

INTRODUCING THE ALGORITHMIC INTERSECTIONAL FEMINIST ACTIVIST MOVEMENT: ................................ 11

MACROMARKETING DISCLOSURES OF THE HETEROGENEOUS INTERDEPENDENCE OF HIDDEN DATA LABOR 11

JONATHAN BOWMAN, UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................................................ 11

ETHICS, EQUITY, AND SOCIAL JUSTICE TRACK .................................................................................... 18

NO PLACE TO HIDE: IN-SCHOOL MARKETING, THE COMMODIFICATION OF CHILDREN AND THE

COMMERCIALISATION OF EDUCATION ............................................................................................................ 19

ROBERT AITKEN, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, NEW ZEALAND ................................................................................. 19

LEAH WATKINS, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, NEW ZEALAND .................................................................................. 19

RYAN GAGE, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND ................................................................. 19

LOUISE SIGNAL, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND............................................................. 19

THE NATURE OF “LEGITIMATE PROFIT” FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING:

IMPLICATIONS FOR MACROMARKETING ......................................................................................................... 25

NICHOLAS J.C. SANTOS, CREIGHTON UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................................................ 25

SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE MARKETING AND ENGAGING IMPOVERISHED POPULATIONS TOWARDS A

SUSTAINABLE FUTURE: LESSONS FROM COVID-19 .......................................................................................... 30

NICHOLAS J.C. SANTOS, CREIGHTON UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................................................ 30

TINA M. FACCA-MIESS, JOHN CARROLL UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................... 30

MARY KATE NAATUS, SETON HALL UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................................................. 30

KAEPERNICK, JAY-Z, AND DU BOIS: ............................................................................................................... 35

RACELIGHTING AS A WICKED PROBLEM AND VIOLATION OF HYPER NORMS OF GLOBAL CONDUCT ............. 35

JONATHAN BOWMAN, UNIV OF ARKANSAS, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .......................................................... 35

EXTERNALITIES TRACK .............................................................................................................................. 54

EXPLORING CONTROVERSY AND EMBLEMATIC EXTERNALITIES THROUGH PSYCHEDELIC MARKETS: WHEN

RULES CHANGE, SO DOES MEANING ............................................................................................................... 55

KERRYN M. LYES, UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND ...................................................................... 55

C. MICHAEL HALL, UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND .................................................................... 55

ANN-MARIE KENNEDY, UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND .............................................................. 55

PAUL BALLANTINE, UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND .................................................................... 55

FOOD MARKETING TRACK.......................................................................................................................... 67

RETAIL SALES PROMOTIONS FOR SUBOPTIMAL FOOD – HOW TO REDUCE FOOD WASTE WITHOUT HARMING

CUSTOMERS’ LOYALTY? ................................................................................................................................. 68

LINDA ANGENENDT, UNIVERSITY OF PADERBORN, GERMANY ............................................................................ 68

EVA BÖHM, UNIVERSITY OF PADERBORN, GERMANY ......................................................................................... 68

INA GARNEFELD, UNIVERSITY OF WUPPERTAL, GERMANY ................................................................................. 68

RESEARCH DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS ................................................................................................................. 70

TRANSITIONING FROM HOME TO UNIVERSITY: NAVIGATING LIMINALITY THROUGH STUDENT FOOD

PRACTICES ...................................................................................................................................................... 74

SHEENA LEEK, UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM, UNITED KINGDOM ....................................................................... 74

EMMA SURMAN, UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM, UNITED KINGDOM .................................................................... 74

TOWARDS THE ACTORS CO-CREATION AND ORGANIC INTIMACY CONTROLLED BY A MARKET MEDIATOR IN A

NASCENT CATEGORY ...................................................................................................................................... 77

JUNG-YIM BAEK, UNIVERSITY OF MARKETING AND DISTRIBUTION SCIENCES, JAPAN .......................................... 77

MARI NINOMIYA, OSAKA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY, JAPAN .......................................................................... 77

TSUKASA KATO, OSAKA UNIVERSITY OF COMMERCE, JAPAN ............................................................................. 77

MITSUHISA HAMA, NAGOYA GAKUIN UNIVERSITY, JAPAN ................................................................................. 77

GENERAL MACROMARKETING TRACK ................................................................................................... 80

6

DEATH AND DIOR: A TERROR MANAGEMENT THEORY PERSPECTIVE ON THE USAGE OF LUXURY GOODS TO

COPE WITH THREATS OF MORTALITY............................................................................................................. 81

STEPHANIE GEIGER-ONETO, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ....................................... 81

OMAR SHEHRYAR, MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ............................................... 81

THE RESILIENCE OF STREET HAWKERS IN A CRISIS: A CAPABILITY-BASED CONCEPTUALIZATION ............... 89

TAMAL SAMANTA, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT, LUCKNOW .................................................................. 89

RAJESH K AITHAL, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT, LUCKNOW.................................................................. 89

CONSUMER WELLBEING: THE INDIRECT IMPACT OF PRIVATE LABEL BRANDS ON QUALITY OF LIFE ........... 91

PETER J. BOYLE, CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................ 91

JUYOUNG KIM, SOGANG UNIVERSITY, SOUTH KOREA ........................................................................................ 91

PUBLIC HEALTH CONCERNS, CANNABIS POLICY, AND CONSUMER CANNABIS BEHAVIOR (RE) SHAPING

CANNABIS MARKETING SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................... 94

CLAUDIA DUMITRESCU, CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.............................. 94

KATHRYN MARTELL, CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .................................. 94

ENTREPRENEURSHIP ORIENTATION AND FIRM PERFORMANCE: THE MEDIATING EFFECT OF DYNAMIC

CAPABILITY AND GOVERNMENT SUPPORT TO SME BUSINESSES IN GHANA ................................................. 101

SADICK ALHAJI HUSSEINI, CORVINUS UNIVERSITY OF BUDAPEST, HUNGARY ................................................... 101

FROM STONES TO ELECTRONS: THE EVOLUTION OF HOMO SAPIENS ........................................................... 105

CHARLES INGENE, UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .................................................. 105

JIE FOWLER, VALDOSTA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ...................................................... 105

POLITICAL MACROMARKETING PERSPECTIVE IN THE CASE OF BRAZIL’S LACK OF DEVELOPMENT GROWTH

...................................................................................................................................................................... 109

MONIQUE MATSUDA DOS SANTOS, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................... 109

MARK PETERSON, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .................................................... 109

GLOBALISATION, (NEO)COLONIALISM, AND MARKETING TRACK ................................................ 115

EXPLORING A DEMOCRATIZED STAKEHOLDER ETHNOCRATIC FRAMEWORK: DU BOIS ON SYSTEMIC RACISM

IN A HISTORY OF NFL SCANSIS PHENOMENA ................................................................................................ 116

JONATHAN BOWMAN, UNIV OF ARKANSAS, LITTLE ROCK, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .................................. 116

FRANK BRAUN, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, OSHKOSH, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ...................................... 116

LEARNING TO TARRY IN DECOLONISING MARKETING EDUCATION .............................................................. 138

CAROLINE CHAPAIN, UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM, UNITED KINGDOM............................................................ 138

EMMA SURMAN, UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM, UNITED KINGDOM .................................................................. 138

A TRANSMODERN PERSPECTIVE OF BRAZILIAN CONSUMERISM: THE CASE OF WOMEN FROM SALGUEIRO 140

MÍRIAM DE SOUZA FERREIRA, PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL ................... 140

MARCUS WILCOX HEMAIS, PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL........................ 140

IN FAVOR OF A TRANSMODERNIST CONSUMERIST EDUCATION: THE ESCOLA NACIONAL FLORESTAN

FERNANDES ................................................................................................................................................... 143

MARCUS WILCOX HEMAIS, PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL........................ 143

RONAN TORRES QUINTÃO, INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE EDUCAÇÃO, CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DE SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL

...................................................................................................................................................................... 143

DENISE FRANCA BARROS, UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE, BRAZIL ....................................................... 143

BEYOND THE BORDERS OF MARKETING SYSTEMS: THE ROLE OF CATALYTIC INSTITUTIONS IN THE

INCLUSION OR EXCLUSION OF PEOPLE IN THE MARKET ............................................................................... 147

MARCIO LEANDRO MÜLLER, UNIVERSIDADE DO GRANDE RIO - UNIGRANRIO - DUQUE DE CAXIAS, BRAZIL .. 147

JOÃO FELIPE R. SAUERBRONN, SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA, AND INFORMATION AT FGV - RIO DE

JANEIRO, BRAZIL ............................................................................................................................................ 147

POWER RELATIONS IN MARKETING SYSTEMS ............................................................................................... 149

MARCIO LEANDRO MÜLLER, UNIVERSIDADE DO GRANDE RIO - UNIGRANRIO - DUQUE DE CAXIAS, BRAZIL .. 149

ELAINE DE SOUZA SILVA, UNIVERSIDADE DO GRANDE RIO - UNIGRANRIO - DUQUE DE CAXIAS, BRAZIL ....... 149

JOÃO FELIPE R. SAUERBRONN, SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA, AND INFORMATION AT FGV - RIO DE

JANEIRO, BRAZIL ............................................................................................................................................ 149

7

AMBIVALENCE AND RESISTANCE TOWARD GLOBAL BRANDS’ PRACTICES: DIGITAL CONSUMER ACTIVISM IN A

DEVELOPING MARKET CONTEXT .................................................................................................................. 154

EDNA G. NDICHU, WHITWORTH UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ..................................................... 154

SHIKHA UPADHYAYA, CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ..................................... 154

HISTORICAL RESEARCH IN MARKETING TRACK ............................................................................... 160

NATIVE AMERICANS IN FIREARMS ADVERTISING: HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND REPRESENTATIONAL ETHICS

...................................................................................................................................................................... 161

TERRENCE H. WITKOWSKI, CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .............................. 161

MACROMARKETING MEASUREMENTS AND METHODS TRACK ...................................................... 171

DETECTING VALUE LOSS, POWER ASYMMETRY AND UNDERPERFORMING PROVISIONING SYSTEMS:

EXTENDING ALDERSON’S TRANSVECTION ANALYSIS TO INCREASE SUSTAINABILITY ................................... 172

BEN WOOLISCROFT, AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, NEW ZEALAND, JAMES WILKES, TROIKA ...... 172

SUPEREROGATION THEORY: TOWARDS A MACROMARKETING UNDERSTANDING ........................................ 173

ANTHONY SAMUEL, CARDIFF UNIVERSITY, UNITED KINGDOM ......................................................................... 173

GARETH WHITE, CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY, UNITED KINGDOM .......................................................................... 173

DISCOVERING MACROMARKETING NETWORKS IN ACADEMIA AND TWITTER............................................... 177

PETTERI REPO - CENTRE FOR CONSUMER SOCIETY RESEARCH, UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, HELSINKI INSTITUTE OF

SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE, HELSINKI INSTITUTE OF URBAN AND REGIONAL STUDIES, FINLAND......................... 177

OBSERVATIONS ON THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS OF THE MACROMARKETING SEMINAR PROCEEDINGS ......... 187

BEN WOOLISCROFT, AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, NEW ZEALAND ............................................... 187

MACROMARKETING PEDAGOGY TRACK .............................................................................................. 188

DEBATE, DISCUSSION, OR DIALOGUE: WHAT'S THE IDEAL FORMAT FOR MACROMARKETING LEARNING? . 189

FORREST WATSON, DICKINSON COLLEGE, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .......................................................... 189

STEFANIE BENINGER, NYENRODE BUSINESS UNIVERSITY, THE NETHERLANDS ................................................. 189

JULIE STANTON, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .................................. 189

A NEW APPROACH TO “BOOK LEARNING”?.................................................................................................. 196

STANLEY J. SHAPIRO, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, CANADA ........................................................................... 196

JULIE V. STANTON, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.............................. 196

AUTOETHNOGRAPHY AS PEDAGOGY TO UNDERSTAND MARGINALIZED PROSUMERS .................................... 204

SUJIT RAGHUNATHRAO JAGADALE, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AMRITSAR, INDIA ............................. 204

CHATGPT IN THE MARKETING CLASSROOM: FRIEND OR FOE? ................................................................... 209

ALEX REPPEL, ROYAL HOLLOWAY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM ............................................. 209

STEFANIE BENINGER, NYENRODE BUSINESS UNIVERSITY, NETHERLANDS......................................................... 209

CHRISTINE DOMEGAN, NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND, IRELAND ............................................................. 209

AUTOMATING THE PRODUCTION OF SLIDES, SHORT-FORM VIDEOS, AND OTHER COURSE MATERIALS: ..... 217

WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIEND, GPT-3 ......................................................................................... 217

ALEX REPPEL, ROYAL HOLLOWAY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM ............................................. 217

DARRYN MITUSSIS, QUEEN MARY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM ............................................... 217

ARCGIS STORYMAPS: AN IDEAL CONNECTION TOOL FOR MACROMARKETER EDUCATORS ....................... 219

FORREST WATSON, DICKINSON COLLEGE, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA .......................................................... 219

QUALITY OF LIFE AND WELLBEING TRACK ........................................................................................ 222

EXAMINING THE DIMENSIONS AND MODERATORS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN VOLUNTARY SIMPLICITY

AND WELLBEING ........................................................................................................................................... 223

LEAH WATKINS, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, NEW ZEALAND ................................................................................ 223

ROB AITKEN, UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO, NEW ZEALAND ..................................................................................... 223

LOIC LI, LA TROBE UNIVERSITY, AUSTRALIA .................................................................................................. 223

CONSUMPTION AND HEDONIC WELLBEING: A TOP-OF-MIND EXPLORATION .............................................. 229

ALEXANDRA GANGLMAIR-WOOLISCROFT, MASSEY UNIVERSITY AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND .......................... 229

8

REVISITING GOVERNMENT’S ROLE IN PROVISIONING: OBSERVATIONS THROUGH A

MACROMARKETING LENS TRACK .......................................................................................................... 237

THE INADEQUACIES OF SOLELY USING A MACROMARKETING LENS – INTRODUCTION TO THE SPECIAL

SESSION ......................................................................................................................................................... 238

A FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF MARKETING IN THE ECONOMY AND SOCIETY ............ 240

RAYMOND BENTON, JR., LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................................... 240

CRITICAL MACROMARKETING AND THE BETTER POST-PANDEMIC WORLD ................................................. 270

A. FUAT FIRAT, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS – RIO GRANDE VALLEY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ......................... 270

EMRE ULUSOY, PACIFIC LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ............................................... 270

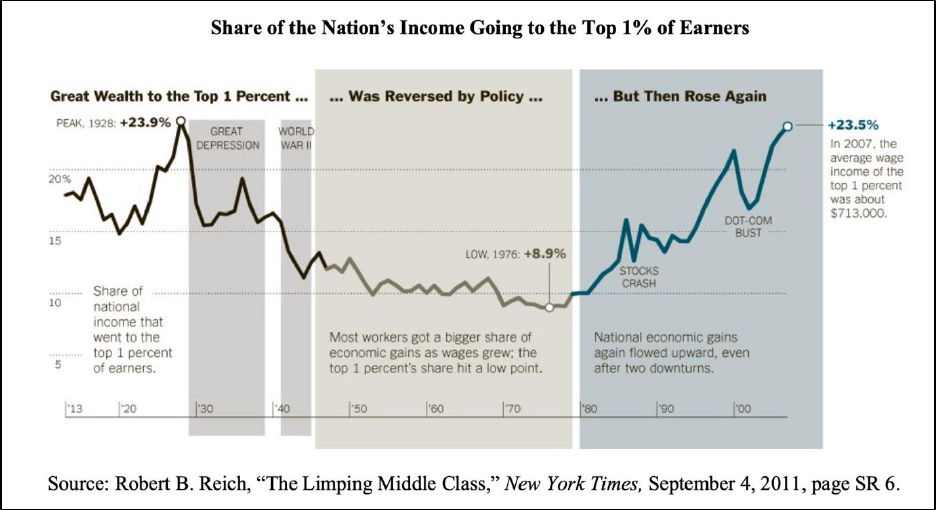

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT’S PROGRAM OF WELFARE FOR THE WEALTHY ...................................................... 277

STANLEY F. STASCH, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................ 277

RAYMOND BENTON, JR., LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................................... 277

SOCIAL CONFLICTS AND MARKET DYNAMICS .................................................................................... 300

SOCIAL CONFLICTS AND MARKET DYNAMICS: AN OVERVIEW ..................................................................... 301

ANDRÉS FAJARDO BARRIOS, UNIVERSIDAD DE LOS ANDES, COLOMBIA ............................................................ 301

CLIFFORD J. SHULTZ, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................ 301

WAR ON UKRAINE AND THE DELIBERATE DESTRUCTION OF A FLOURISHING MARKETING SYSTEM – A VIEW

FROM THE INSIDE .......................................................................................................................................... 303

SOPHIA OPATSKA, UKRAINIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY, UKRAINE .................................................................... 303

CLIFFORD J. SHULTZ, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................ 303

THE REBIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF A MARKETING SYSTEM: UPDATES FROM A LONGITUDINAL STUDY OF

CAMBODIA’S RECOVERY FROM GENOCIDE ................................................................................................... 304

CLIFFORD J. SHULTZ, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................ 304

DON R. RAHTZ, WILLIAM & MARY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.................................................................... 304

THE ETHICAL DIMENSIONS OF “JUST WAR” ................................................................................................. 305

GENE LACZNIAK, MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ...................................................... 305

THE TRANSFORMATIVE ROLE OF LITERACY IN ADDRESSING MARKETPLACE TENSIONS BETWEEN REFUGEES

AND THEIR LOCAL HOSTS ............................................................................................................................. 306

TUGBA OZBEK, YILDIZ TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, TURKEY ............................................................................... 306

EBRU ENGINKAYA ERKENT, YILDIZ TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, TURKEY ............................................................ 306

IBRAHIM KIRCOVA, YILDIZ TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY, TURKEY ......................................................................... 306

STRENGTHENING MARKETING SYSTEMS AND MACRO POLICIES TO ADDRESS SOCIAL CONFLICT AND WELL-

BEING AMONG INDIGENOUS AND PEASANT WOMEN IN PERU ........................................................................ 313

JUNE N. P. FRANCIS, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, CANADA ............................................................................. 313

KRISTINA HENRIKSSON, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, CANADA ........................................................................ 313

THE MARKETPLACE AS INTERCULTURAL DREAMING AND COLLECTIVE DESIRE .......................................... 316

PEKKA SAARIKORPI, HANKEN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS, FINLAND ..................................................................... 316

MARIA HOKKINEN, ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY, FINLAND ............................................................................... 316

PIA POLSA, HANKEN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS, FINLAND................................................................................... 316

SYSTEMIC INTEGRATION OF THE SACRED AND THE SECULAR: TEMPLATE FOR SUSTAINABLE PEACE,

PROSPERITY, HUMANITY AND WELL-BEING ................................................................................................. 322

CLIFFORD J. SHULTZ, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ........................................ 322

NICHOLAS SANTOS, SJ, CREIGHTON UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ............................................... 322

DOMINIC CHAI, SJ, BOSTON COLLEGE, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ............................................................... 322

SUSTAINABILITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE TRACK ............................................................................. 324

PACKAGING SYSTEM TRANSFORMATION FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE: A MACROMARKETING AGENDA? .. 325

JOYA KEMPER, UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND ......................................................................... 325

VICKI JANINE LITTLE, RMIT UNIVERSITY VIETNAM, VIETNAM ........................................................................ 325

SABRINA HELM, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ......................................................... 325

9

THE FOREST AND ITS ROLE IN THE MOVE TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE SOCIETY: SHOULD I STAY OR SHOULD I

GO? ............................................................................................................................................................... 330

KARIN M. EKSTRÖM, UNIVERSITY OF BORÅS, SWEDEN .................................................................................... 330

CONSUMER PREFERENCES AND CIRCULAR ECONOMY: THE CASE OF REUSABLE PACKAGES ....................... 337

HOSSEIN ESLAMI DIZEJE, LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY, LEBANON .......................................................... 337

DIA BANDALY, LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY, LEBANON ......................................................................... 337

NEO-LIBERAL GOVERNMENTALITY AS MARKETING SYSTEM FAILURE: CASE OF STUBBLE BURNING IN INDIA

...................................................................................................................................................................... 344

SUJIT RAGHUNATHRAO JAGADALE, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AMRITSAR, INDIA ............................. 344

JAVED M. SHAIKH, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AMRITSAR, INDIA ...................................................... 344

BUYING UTOPIA: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF SUSTAINABLE FASHION....................................................... 347

XUBEI JIN, DEPARTMENT OF MARKETING, MONASH UNIVERSITY, AUSTRALIA .................................................. 347

JEFF WANG, DEPARTMENT OF MARKETING, MONASH UNIVERSITY, AUSTRALIA ............................................... 347

CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE CLASSROOM: WE’LL GET BY WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM OUR FRIENDS ......... 353

VICKI JANINE LITTLE, RMIT UNIVERSITY VIETNAM, VIETNAM ........................................................................ 353

SABRINA HELM, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ......................................................... 353

CATHERINE FRETHEY-BENTHAM, UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND ................................................. 353

INFORMATIONAL AND EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTIONS AND WASTE SORTING: INSTITUTIONAL RIGIDITY

PERSPECTIVE ................................................................................................................................................ 363

DARIO MIOCEVIC, UNIVERSITY OF SPLIT, REPUBLIC OF CROATIA ..................................................................... 363

SUSTAINABLE MARKETING OF METALS: A CASE STUDY OF STEEL ............................................................... 387

VENKATAPPARAO MUMMALANENI, VIRGINIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ...................... 387

OLAVO PINTO, UNIVERSITY OF MINHO, PORTUGAL .......................................................................................... 392

BEATRIZ CASAIS, UNIVERSITY OF MINHO, PORTUGAL ...................................................................................... 392

FIFA’S GREENEST FOOTBALL CLUB: DELIVERING AND DISSEMINATING SOCIAL INNOVATIONS AT FOREST

GREEN ROVERS ............................................................................................................................................. 404

DR ANTHONY SAMUEL, CARDIFF UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL, UNITED KINGDOM....................................... 404

CATHY MCGOURAN, UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL MANAGEMENT SCHOOL, UNITED KINGDOM .......................... 404

ROBERT THOMAS, CARDIFF UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL, UNITED KINGDOM ............................................... 404

GARETH R.T. WHITE, CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT, UNITED KINGDOM ......................... 404

HOW PROVISIONING SYSTEMS ANALYSIS ADDS TO MARKETING SYSTEMS UNDERSTANDING: EXPLORING THE

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN MACROMARKETING AND PROVISIONING SYSTEMS THINKING .............................. 425

MICHELLE RENTON, TE HERENGA WAKA VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND .................. 425

SOCIAL MARKETING FOR GLOBAL CHANGE: ALIGNING SOCIAL MARKETING WITH THE

UNSDGS TRACK ............................................................................................................................................ 430

DRIVING DELEGITIMATION IN THE MARKETING SYSTEM ............................................................................. 431

ANN-MARIE KENNEDY, UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND ANNA EARL, UNIVERSITY OF

CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND IRINA BALOG, GOTHENBURG UNIVERSITY, SWEDEN .......................................... 431

10

Cultural (Digital) Phenomena, Markets and Marketing

Systems Track

Co-Chairs:

Ingrid Becker

University of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Michaela Haase

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

11

Introducing the Algorithmic Intersectional Feminist Activist Movement:

Macromarketing Disclosures of the Heterogeneous Interdependence of Hidden Data Labor

Jonathan Bowman, University of Arkansas, United States of America

Disclosing the full extent of otherwise hidden artificial intelligence (AI) labor yields a hyper-

complex pattern of willful exploit upon a culturally heterogeneous workforce facing overlapping

power imbalances (Steinfield and Holt 2020). In tracking how a consumer resistance movement

could even exert counter-pressures upon structural domination, we follow (Valor, Diaz, and

Merino 2017) in conceding there are macroprocesses at work that make resistance hard to assign

against any single target oppressor. However, in contrast to their appeal to the works of Foucault

and Arendt, intersectional social justice theory holds that women of color from the developing

world have been both intentionally and unintentionally subjected to unjust domination through

systemic racism not attributable to the conscious will of a single moral agent (Burrell and

Fourcade 2021). As a guiding premise to complement the primacy of race, gender, and class as

strong demographic determinants for participation in hidden data labor, one abiding constant to

disclosing its practice is unveiling the ways in which intersectional tenets can be applied to

marginalized stakeholders that may bring competing voices, collective memories, gendered

experiences, and racial testimonies to the same material experiences (Davis 2007; Saatcioglu and

Corus 2014; Steinfield and Holt 2020).

One macromarketing contribution would be to propose actionable improvements in quality of

life through recognition of laborers that serve as necessary conditions for the possibility of

globalized AI applications. Once the true social, moral, and monetary value of their contributions

is brought to light, intersectional activist networks document and publish warranted distributive

justice aims. These include but are not limited to eliminating unpaid labor, providing more stable

work conditions, and offering access to full time benefits like a salary, healthcare, retirement

savings, and paid leave. Data labor intersectional solidarity emerges through the shared

disclosure of common negative experiences among hidden digital laborers in domains as diverse

as search, facial recognition, audio transcription, image labeling, and geo-mapping. As a

macromarketing objective of this research, we seek to pair up this hidden labor force with a

growing body of consumer market activists concerned with their own moral culpability.

In terms of methodological commitments, we agree with Helma Lutz in positing

“Intersectionality as Method” (2015) when construing intersectionality as ‘a heuristic device or

method that is particularly helpful in detecting the overlapping and co-construction of visible

and, at first sight, invisible strands of inequality’ (39). When wedding intersectional

methodologies to macromarketing aims, we can make ‘meso’ societal connections between

individual acts of micro-consumption and macro systemic institutions. Platform-mediated

marketplaces demonstrate macromarketing institutional traits of high complexity, system

heterogeneity, and species interdependence (Mittelstaedt, Kilbourne, and Mittelstaedt 2006).

Once macromarketing aids intersectional scholars in demystifying the ‘magic of AI’ (Elish and

Boyd 2018), their shared aim to disclose the intersections of race, gender, and class as crucial

demographic indicators for detecting the presence of ‘ghost work’ (Gray and Suri 2019), ‘data

janitors’ (Irani 2015), and ‘fauxtomation’ (Taylor 2018) exposes the dark side of data

12

automation. This is as an actionable first step toward mitigating the unwarranted moral harm of

systemic racism. Teasing out the adverse impacts that tech entrepreneurs otherwise attribute to

workers in a better place, their quality of life is too often cast through neoliberal images of

happy, non-white, female, and global South workers to veil the systematic labor displacement we

are all increasingly complicit in willing through everyday platform-mediated acts (Irani 2015).

In what we will term intersectional 'algoactivism,' figures like Noble, Buolamwini, Payton,

Benjamin, and Burrell not only leverage their status as elite female scholars of color and

privilege disseminating their work in the top journals of their respective disciplines, but they also

wed their scholarly efforts to social activism (see Tables 1 and 2 below for more detail). For

Noble, she began this path toward algoactivism through a testimonial experience of how teenage

female family members of color ran queries on Google (Noble 2018). She observed that even in

circumstances of private information searches concerning intersecting gender and racial

identities, media of algorithmic socialization reflected the virtual public sphere of tying the

search of 'black girls' immediately to pornographic sites as among the top 100 searches when

searches for white girls showed no similar pattern (Noble 2018). Similarly, for Buolamwini (Joy

2018), the activity of a public researcher of emergent technologies that dealt with facial

recognition could not be separated from her testimonial experience that had fueled her algo-

activism into what she has termed the ‘coded bias.’ In her early doctoral studies, she found that

she, as a woman of color, could not be algorithmically identified as the private subject she claims

by name. Through the performative act of critical research on facial recognition, she discovered

that she must wear a white mask for the technology to register her face as human. Shifting

intersectionality to the domain of public health, Professor Payton’s participatory approach to

disclosing the ways in which medical data infrastructures often marginalize the women of color

they are funded to serve (2014), has carried her to leadership prominence with the NSF. Payton

gives community-based participatory models an intersectional spin in calling public health

messaging to run through processes of co-creation among digital designers and those marginal

groups most immediately affected as program co-curators worthy of recognitional input (Kvasny

and Payton 2018).

13

Table 1. Opportunities for Future Macromarketing Systems Research using Intersectionality

Theory

Area

Macromarketing Systems Research Opportunity

Intersectionality

Digital Colonialism

Seek to amend, reconsider, and advance ICT4D research from the theoretical stance

of intersectional theory with the testimonial experience of women of color as the

social scientific evidence for addressing historical colonial injustice.

Criminal Justice

Surveillance

Technologies

Encourage scholars to draw upon the theoretical resources of intersectionality to ask

whether a more equitable balance of demographic representation in datasets will

address more pervasive forms of culturally embedded systemic injustice.

Epistemic Apartheid

Ask which theoretical framings are most missing from macromarketing scholarship

and why. Consider initiatives that would encourage disciplines outside of STEM to

read, cite, and engage with social-scientific bodies of research that might embolden

researchers to forge more eclectic interdisciplinary theoretical framings.

Algorithmic Bias

Consider reframing bias from the standpoint(s) of those experiencing intersecting

forms of gender and racial discrimination and question the efficacy and feasibility of

a neutral unbiased research perspective.

Workplace

Discrimination and ICT

Diversity Initiatives

Encourage the inclusion of interdisciplinary perspectives directly engaging topics of

gender and race in the A-list marketing journals, including special issues, the

composition of the journal editorial teams, and selection of journal reviewer

theoretical competencies.

Biometric Identification

and IoT Technologies

Encourage mixed-method scholarship that pairs together quantitative research on

technological efficiency with a fair measure of qualitative and ethnographic studies

that incorporate the voices and standpoints of persons affected, especially at

intersectional margins.

14

Table 2. Key Scholars in AIFAM – The Algorithmic Intersectional Feminist Activist Movement

Name

Institution

Themes

Literature

Algoactivism

Jenna Burrell

Berkeley

Algorithms constitute a new means of

production owned by the propertied

coding elite as a class differentiator

from the cyberteriat

‘Society of Algorithms’

(Fourcade 2021)

‘How the Machine

Thinks: Understanding

Opacity’ (2016)

Executive Research Director

for Data and Society Institute

Safiya Umoja

Noble

UCLA

Google search algorithms and other

epistemic gatekeeping platforms

evince tremendous bias toward

women, minorities, and persons of

color

Algorithms of

Oppression: How

Search Engines

Reinforce Racism

(2018)

One of the 25 members of the

Real Facebook Oversight

Board; Co-Director of UCLA

Center for Critical Internet

Inquiry

Fay Cobb

Payton

NC State

Calling attention to health care

information technology and

intersectional disparities of race and

gender by designing participatory

models of community health

provisions based on those most

marginalized

Leveraging

Intersectionality:

Seeing and Not Seeing

(2014)

American Council on

Education Fellow; 2016 White

House Summit on the United

States of Women; National

Science Foundation; Essence

Magazine #BlackWomenIn;

SAS Institute Fellow; NPR

Joy Adowaa

Buolamwini

MIT

Algorithmic bias is pervasive in

facial and voice recognition

technologies, financial lending

practices, policing measures,

healthcare services, and many more

domains that disproportionately harm

historically underrepresented groups

‘Gender Shades:

Intersectional Accuracy

Disparities in

Commercial Gender

Classification’ (2018)

Founder of the Algorithmic

Justice League; featured in the

Netflix documentary film

Coded Bias and the mini

documentary The Code Gaze;

heralded by Fortune magazine

as ‘the conscience of the AI

revolution’

15

Ruha Benjamin

Princeton

Research at the interface of

technology, race, and gender with a

focus on how algorithmic code has

institutionalized new forms of

oppression against women,

minorities, and persons of color

Race After Technology:

Abolitionist Tools for

the New Jim Code

(2019);

Founder of the JUST DATA

Lab (2018); Executive Board

for Princeton Center for

Digital Humanities; One of the

25 members of the Real

Facebook Oversight Board

16

Professor Benjamin’s (Ruha 2019) approach takes the macro-societal dynamic to yet another

classification of vulnerable consumers as denizens of virtual spaces algo-governed by what she

terms ‘the new Jim Code.’ Benjamin has made a career of activism in researching the training

data and biases that go into new technologies increasingly utilized by the carceral state in the

form of recidivist (likelihood of repeat criminal offense) algorithms to determine lengths of

incarceration. As an explicit critique of the limited powers of even the most technically astute

data curation, datasets cannot be parsed apart from the structural inequalities that comprise the

society from which the data curation is drawn. Lastly, for Professor Burrell, as the current

research director of Data and Society, she pairs her unique command of AI in tandem with her

encyclopedic command of the history of sociological theory to question whether the

democratizing promise of the information revolution has brought about new forms of digitalized

colonization (Burrell and Fourcade 2021). Burrell adds new meta-categories to our intersectional

framing with three distinct typologies to the opacity that helps keep data curation labor hidden

from public censure (Burrell 2016). First, proprietary opacity protects algorithms under the guise

of state-sanctioned private property protections that ensure for-profit personalization indices

cannot be gamed (or recalibrated or critically assessed) by relevant stakeholders as diverse as

advertisers, influencers, competitors, or even state actors. Second, literacy-based opacity deals

more with the interpretive framing of algorithmic personalization whereby data curation factories

are recast as technological centers to mask modes of crowdsourced divisions of labor as micro-

tasked informational gatekeeping. Thirdly, opacity due to complexity of application scale begins

to parse out the manners in which rule-based algorithmic learning (such as recognizing numbers,

faces, or handwriting) sharply differs from human learning in manners whereby we are often left

with ‘known unknowns’ that emerge through otherwise seemingly spurious correlations that

have yet to find equivalences in human information processing and learning. For Burrell, while

each level of opacity merits its separate conceptual classification, she also warns that the

intersections of proprietary, literacy, and complex application scale opacities, when embedded

within systems of maximizing market performance at the cost of those most vulnerable, show a

decided tendency to accelerate epistemic and material disparities in reinforcing systemic patterns

of racism. Insofar as the most advanced algorithmic models are under the proprietary domain of

GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft), for better or worse, one

contribution of our research is to show that macromarketing takes on arguably the heaviest onus

of responsibility for intersectional systemic injustices since once constant to GAFAM is the

unrivaled sophistication of their personalized algorithms for strategic purposes of targeted

marketing (Gray and Suri 2019).

References

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code.

Cambridge: Polity Press.

Buolamwini, J. (2018). ‘Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial

Gender Classification.’ Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 81: 1-15.

Burrell, J. (2016). How the machine ‘thinks’: Understanding opacity in machine learning

algorithms. Big data & society, 3(1), 1-12.

Burrell, J. and Fourcade, M. (2021). The Society of Algorithms. Annual Review of Sociology

47(1): 213-237.

Davis, J.F. (2007). ‘”Aunt Jemima is Alive and Cookin’?”: An Advertiser’s Dilemma of

17

Competing Collective Memories.” Journal of Macromarketing 27(1): 25-37.

Elish, M.C. and D. Boyd. (2018). “Situating Methods in the Magic of Big Data and Artificial

Intelligence.” Communications Monographs 85(1): 57-80.

Gray, M.L. and S. Suri. (2019). Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New

Global Underclass. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Irani, L. 2015. “The Cultural Work of Microwork.” New Media and Society 17(5): 720-739.

Kvasny, L., & Payton, F. C. (2018). Managing Hypervisibility in the HIV Prevention

Information‐Seeking Practices of Black Female College Students. Journal of the

Association for Information Science and Technology, 69(6), 798-806.

Lutz, H. (2015). “Intersectionality as Method.” Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 2(1-2):

39-44.

Middelstaedt, J.D., W.E. Kilbourne, and R.A. Mittelstaedt. (2006). “Macromarketing as

Agorology: Macromarketing Theory and the Study of the Agora.” Journal of

Macromarketing 26(2): 131-142.

Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York:

NYU Press.

Payton, F.C. (2014). Leveraging Intersectionality: Seeing and Not Seeing. Richer Press: New

York.

Saatcioglu, B. and C. Corus. (2014). “Poverty and Intersectionality: A Multidimensional Look

into the Lives of the Impoverished.” Journal of Macromarketing 34(2): 122-132.

Steinfield, L. and D. Holt. (2020). “Structures, Systems, and Differences that Matter: Casting an

Ecological-Intersectionality Perspective on Female Subsistence Farmers’ Experience of

the Climate Crisis.” Journal of Macromarketing 40(4): 563-582.

Taylor. A. (2018). “The Automation Charade.” Logic Magazine (5) Special Issue—Failure.

Valor, C., E.M. Diaz, and A. Merino. (2017). “The Discourse of the Consumer Resistance

Movement: Adversarial Framings through the Lens of Power.” Journal of

Macromarketing 37(1): 72-84.

18

Ethics, Equity, and Social Justice Track

Co-Chairs:

Ann-Marie Kennedy

University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Cathy McGouran

University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Nicky Santos

Creighton University, United States of America

19

No Place to Hide: In-School Marketing, the Commodification of Children and the

Commercialisation of Education

Robert Aitken, University of Otago, New Zealand

Leah Watkins, University of Otago, New Zealand

Ryan Gage, University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand

Louise Signal, University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand

In-school marketing (ISM) is a widespread global practice that is the focus of much debate and

increasing concern. The tension between commercial imperatives and educational priorities has

been recognised by the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur for Children who has called for

centrally mandated regulation of ISM. In response, a variety of policies have been developed in

different countries to regulate the practice. However, understanding the nature and extent of

commercial activities in schools is difficult and a growing number of academics have called for

more research in this area. Accordingly, this paper explores the nature and extent of ISM in NZ

primary and intermediate schools. Results suggest extensive incidence of ISM in a variety of

forms including product branding, corporate merchandise, sponsorship and curriculum materials.

Introduction

ISM is widespread across all levels of education and is increasingly normalised as new

marketing opportunities arise within and around schools, blurring the boundaries between private

and public, profit and philanthropy (Enright and Macdonald 2020; Marsh 2017). Schools,

struggling with inadequate public funding, are welcoming the perceived benefits of ISM without

necessarily recognising the threats that increased exposure to marketing can bring to children’s

wellbeing or to the integrity of the education they receive (Molnar et al. 2015; Thrupp et al.

2020). Balancing the need to provide the resources necessary for an effective education with the

consequences of reduced budgets, ISM seems to provide a mutually beneficial solution to the

problem. However, there is growing concern with the potentially negative effects on children of

increased exposure to marketing (Opree 2014), and the consequences of increased commercial

influence on educational imperatives (Marsh 2017; Molnar et al. 2010). ISM is also cause for

concern given the susceptibility of children to commercial messages (Oates et al. 2002) and that

they are a captive and credulous audience in an educational environment where marketing

messages are legitimised by their on-going presence in and around the school (De Lulio 2019;

Molnar et al. 2011).

The increasing incidence of ISM and research on the negative impacts of marketing on children’s

social and psychological well-being has resulted in increasing ethical concerns with its

appropriateness and a recent UK report states that “commercialising programmes in schools

bring with them serious threats to children’s education and to their psychological and physical

well-being” (Molnar et al. 2013). One key concern is that ISM contributes unnecessarily to the

already marketing saturated world of children who are vulnerable to its affects (Brent and

Lunden 2009). Concerns about children’s vulnerability to the effects of exposure to marketing

are based on their limited ability to understand its motivations and their susceptibility to

persuasive advertising (Calvert, 2008; Oates et al. 2002).

20

Specifically, literature raises concerns that commercial partnerships can harm children

educationally by displacing other educational activities and messages (Robinson et al. 2016), for

example through the presence of soft drinks and unhealthy foods which contradict nutrition

education. Another important harm is the threat that it poses to critical thinking given the implicit

endorsement of particular brands and products (Farinha 2015). (Molnar et al. 2011) suggest that

the values and goals of education are incompatible with the imperatives of business and that the

need to foster critical thinking, independent (and freedom of) choice and self-determination do

not sit easily with the preferential promotion and endorsement of particular brands and products.

As (Robinson et al. 2016) caution, ISM resources are shaped by corporations’ biased, value-

laden, and ideological views, and ‘the desired knowledge(s) of corporations are necessarily

present, if not influential or foundational, when such resources are conceived, produced, and

distributed.’ (p1). A final concern is the extent to which ISM normalises the relationship between

consumption and education. As complementary sites for the inculcation of social values, schools

have a responsibility to socialise children as citizens rather than consumers.

Summary

Children are exposed to an increasingly wide range of ISM that marketing research and educational

policy have not kept up with. Research is required, therefore, to understand the nature and

incidence of ISM to inform policy development and make recommendations for its management.

Research Question

What is the nature and extent of ISM in NZ schools?

Study 1 provides an objective analysis of children’s total in-school exposure to marketing through

an ancillary study of the NZ Kids’Cam data.

Study 2 offers a qualitative analysis of the nature and types of ISM found in schools.

Study 1 – Kids’Cam Data analysis

Methodology

Kids’Cam was a cross-sectional, observational study that used automated wearable camera

devices to capture the everyday experiences of children in NZ (Signal et al. 2017a). The cameras

captured a 136 degrees image ahead of the wearer every seven seconds (see ISM image

examples in Figure 1 below). Full details of the Kids’Cam methods, sampling and coding are

published elsewhere (Signal et al. 2017a, 2017b). The data used for the Kids’Cam branding

study (Watkins et al. 2019; Watkins et al. 2022) on which this ancillary study is based, analysed

the images of a random sample of 87 participants stratified by sex, ethnicity and deprivation

which were coded for all marketing exposures for two full days. Coding was based on a four-tier

framework, including the marketing brand name, setting, marketing medium and product

category (Watkins et al. 2022).

Analysis

For the present study we analysed the in-school exposure to determine the nature of advertising

children were seeing in this setting. Mean daily exposure rates to commercial marketing were

estimated using negative binomial regression models, represented by the count of individual

exposures divided by the exposure duration.

21

Results

In the school setting children encountered 53.9 messages per day. Significant differences in

product category exposures by demographics were also examined. While few significant

differences were found, Māori children see more brands in total, and more ‘Other’ brands than

NZ European children.

Study 2 – School Audit

To provide a fuller picture of the context within which children were exposed to marketing, we

conducted an observational analysis of ISM in 20 NZ primary schools.

Methodology

Using the Ministry of Education school directory, principals were contacted in three major NZ

cities to provide a range of population sizes and decile ratings. Direct observation was

considered to be the most appropriate method for this study given that it could be undertaken by

the research team and not require additional time from school staff (Velazquez et al. 2017).

Examples of ISM were identified visually and recorded manually on separate spreadsheets in

columns labelled Location, Brand, Medium and Frequency. A column for General comments

was also included.

Results

Initial coding revealed the main marketing mediums to be brand labels, print media (especially

posters), and promotional/merchandising. The majority of exposure was to brand labels for

‘expected brands’ e.g. Office Max, stationary; Nike, sports equipment; Apple, electronics and

Panasonic hardware. Print media in the form of posters and flyers, mostly located in classrooms,

common areas and gymnasiums, were the most prevalent. Specific examples of Brands noted for

their frequent presence in multiple schools were Scholastic Book Clubs and Fonterra.

Discussion

Results from both studies show that children are exposed to a significantly high, and increasingly

varied, amount of marketing in school. Indeed, children’s exposure to marketing in schools is

higher than it is in other settings such as at home and in the community. Some examples of ISM

include social marketing messages that discourage smoking, encourage sunsmart behaviour and

promote the importance of mental wellbeing. Clearly, these examples of socially acceptable

marketing are to be encouraged in an environment where the provision of reliable information,

advice and support are to be expected. Of concern, however, is the level of marketing saturation

within which they compete for attention. One of the most common forms of ISM observed was

sports sponsorship and merchandising. In relation to leading sports teams and competitions, the

names of the major sponsors were prominent on posters, flyers, wallcharts and calendars

advertising their relationship. Apart from leading sports brands, such as Nike, Adidas and

Reebok, none of the other major sponsors had a direct or obvious association with sport, for

example large banks (ANZ, Westpac and ASB). In relation to physical equipment, the same

pattern of associations was evident. Westpac bank, for example, provided sports bags, and Lotto,

NZ’s national gambling organisation, provided cones and Frisbees. Perhaps the most common,

and certainly the most widespread, example of ISM is represented by Scholastic Book Club. In

addition to books and reading materials, Scholastic also offers a wide range of activity products

22

such as puzzles, colouring sets, jewellery, toys, and branded merchandising products such as

Roblox, Minecraft and Pokemon. This integration of educational and non-educational products

in a non-retail setting, positions children as customers and blurs the line between commercial

interests and educational values.

In relation to health and food, the most conspicuous example of ISM was the presence of two of

NZ’s leading food producers, Fonterra and Sanitarium. Following a nationwide initiative to

provide free milk in schools, Fonterra aligned with Sanitarium, a leading producer of breakfast

cereals, to make free breakfasts available to schoolchildren throughout NZ. The merits of such

schemes have been discussed in a number of academic studies and while there is agreement on

the need for a healthy start to the school day, there is concern with the branded nature of the

products being provided. For a captive and impressionable audience, for whom early brand

experiences lead to later brand preferences (Connell et al. 2014; Nairn and Ormrod 2005), the

benefits of a branded breakfast need to be understood in relation to the strategic benefits it brings

to its sponsors (Aitken and Watkins 2017).

Increasingly, concerns with ISM are also focussing on schools’ reliance on privately produced

commercial resources to supplement their work in response to changing curriculum priorities and

reductions in central funding. The increasing availability of commercially produced educational

programmes is part of a global education industry which is redefining how education is

marketised, privatised and commercialised (Enright et al. 2020). In addition to concerns with the

propriety of industry partners and the ideological imperatives of commercially produced

educational materials, are those concerned with equity. In short, the implications of schools’

increasing reliance on commercial sources of funding, is the extent to which inequalities arise as

schools in poorer areas become disproportionately dependent on alternative sources of income

(Valequez et al. 2017; Brent et al. 2009).

Conclusion

Results from the present research show that ISM is a common feature of the school environment

and a normal part of children’s educational experience. It features explicitly in the form of

sponsored programmes and products and implicitly in the provision of equipment and teaching

resources. Increasingly, curriculum needs are being met by commercial contributions as schools

work to balance reduced budgets and increased demands. Uncritically, the relationships between

commercial interests and educational imperatives could be seen as mutually beneficial. Schools

need the resources to achieve their aims and businesses have the resources to enable them. A

more critical analysis, however, would suggest that the implications of this relationship are not

fully understood or adequately addressed. Concerns have been raised about children’s exposure

to ISM and the increasingly branded nature of their educational experience. A key concern is that

ISM contributes unnecessarily to the already marketing saturated world of children who are

vulnerable to its affects (Brent and Lunden 2009). A final concern is the extent to which ISM

normalises the relationship between consumption and education. As complementary sites for the

inculcation of social values, schools have a responsibility to socialise children as citizens rather

than consumers. The tension between commercial interests and educational imperatives has been

recognised by the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur for Children who has called for centrally

mandated regulation of ISM (2014). Identifying the nature and extent of ISM as presented in this

research is an important step to inform such regulation.

23

References

Aitken, R., & Watkins, L. (2017). “Harm or Good? Consumer Perceptions of Corporate Strategic

Giving in Schools.” Journal of Consumer Affairs, 51(2), 406-432.

Brent, B. O., & Lunden, S. (2009). “Much ado about very little: The benefits and costs of school-

based commercial activities”. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8(3), 307-336.

Calvert, S. (2008). Children as Consumers: Advertising and Marketing. The Future of Children,

18(1), 205-234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0001

Connell, P. M., Brucks, M., & Nielsen, J. H. (2014). “How childhood advertising exposure can

create biased product evaluations that persist into adulthood.” Journal of Consumer

Research, 41(1), 119-134.

Enright, E., Kirk, D., & Macdonald, D. (2020). “Expertise, neoliberal governmentality and the

outsourcing of Health and Physical Education.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of

Education, 41(2), 206-222.

Farinha, I. (2015). “Ads and fundraising: a quasi-market school system. International E-Journal

of Advances in Education,” 1(1), 13-17.

Marsh, V. (2017). “The war on childhood: Commercialism in schools and the first amendment.”

Houston Law Review, 55, 511.

Molnar, A., Boninger, F., & Fogarty, J. (2011). “The Educational Cost of Schoolhouse

Commercialism”. Boulder, CO: 2010–2011 National Education Policy Center.

Molnar, A., Boninger, F., Harris, M., Libby, K., and Fogarty, J. (2013). “Promoting

Consumption at School. Health Threats Associated with School House Commercialism.” The

Fifteenth Annual Report on Schoolhouse Commercializing Trends: 2011–2012.National

Education Policy Center.http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/schoolhouse-commercialism-2012.

Molnar, A., Koski, W. S., & Boninger, F. (2010). “Policy and Statutory Responses to

Advertising and Marketing in Schools.” Legislation Policy Brief. Commercialism in Education

Research Unit.

Nairn, A., Ormrod, J. and Bottomley, P. A. (2005), “Watching, Wanting and Wellbeing:

Exploring the Links.” UK: National Consumer Council.

Oates, C., Blades, M., & Gunter, B. (2002). “Children and television advertising: When do they

understand persuasive intent?” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1(3), 238-245.

Opree, S. J. (2014), “Consumed by consumer culture? Advertising’s impact on children’s

materialism and life satisfaction.” PhD Thesis: Amsterdam School of Consumer Research.

http://dare.uva.nl/record/1/410142

24

Robinson, D. B., Gleddie, D., & Schaefer, L. (2016). “Telling and selling: A consideration of the

pedagogical work done by nationally endorsed corporate-sponsored educational resources.”

Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 7(1), 37-54.

Signal, L. N., Smith, M. B., Barr, M., Stanley, J., Chambers, T. J., Zhou, J., & Mhurchu, C. N.

(2017a). “Kids’ Cam: an objective methodology to study the world in which children

live.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(3), e89-e95.

Signal, L. N., Stanley, J., Smith, M., Barr, M. B., Chambers, T. J., Zhou, J., & Ní Mhurchú, C.

(2017b). “Children’s everyday exposure to food marketing: an objective analysis using wearable

cameras.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 1-11.

Thrupp, M., & Lupton, R. (2011). “Variations on a middle class theme: English primary schools

in socially advantaged contexts.” Journal of Education Policy, 26(2), 289-312.

United Nations (UN). 2014. General Assembly Report on Cultural Rights 69

th

Session. (accessed

7 June 2020) https://documents-dds-

ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N14/499/88/PDF/N1449988.pdf?OpenElement

Vanwesenbeeck, I., Opree, S. J., & Smits, T. (2017). “Can disclosures aid children’s recognition

of TV and website advertising?” In Advances in Advertising Research VIII (pp. 45-57). Springer

Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Velazquez, C. E., Black, J. L., & Potvin Kent, M. (2017). “Food and beverage marketing in

schools: a review of the evidence.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 14(9), 1054.

Watkins, L., Aitken, R., Gage, R., Smith, M.B., Chambers, T.J., Barr, M., Stanley, J. and Signal,

L.N. (2019) “Capturing the Commercial World of Children: The Feasibility of Wearable

Cameras to Assess Marketing Exposure.” Journal of Consumer Affairs. Vol 53 (4) pp 1396-1420

https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12234

Watkins, L., Gage, R., Smith, M., McKerchar, C., Aitken, R., & Signal, L. (2022). “A Brand a

Minute–An observational study of children’s exposure to marketing in an era of

overconsumption.” Lancet Planetary Health.

Werbel, J. D., & Wortman, M. S. (2000). Strategic philanthropy: Responding to negative

portrayals of corporate social responsibility. Corporate Reputation Review, 3(2), 124-136.

Wood, B., Thrupp, M., & Barker, M. (2021). “Education policy: Changes and continuities since

1999.”

Wright, N., & Peters, M. (2017). “Sell, sell, sell or learn, learn, learn? The EdTech market in

New Zealand’s education system–privatisation by stealth?” Open Review of Educational

Research, 4(1), 164-176.

25

The Nature of “legitimate profit” from the Perspective of Catholic Social Teaching:

Implications for Macromarketing

Nicholas J.C. Santos, Creighton University, United States of America

No profit is in fact legitimate when it falls short of the objective of the integral promotion of the

human person, the universal destination of goods and the preferential option for the poor, and

we can add, the protection of our common home (Francis 2022)

In early 2023, the well-known home goods chain Bed Bath & Beyond prepared for bankruptcy

following a run of poor sales, a situation faced by other U.S. retailers such as Sears Holdings

Corp, which filed for bankruptcy in October 2018 after not turning a profit since 2011 (Reuters

2023). Profits are essential for the running of the business and businesses that do not make a

profit such as the examples of Bed Bath & Beyond and Sears Holdings and who file for

bankruptcy often face the possibility of being closed. For instance, Bed Bath & Beyond as of

early February 2023 had closed about 400 stores over the past year (Valinsky 2023) and in April

2023 announced that it would close all its stores by June 2023 (Holman and Hirsch 2023). Such

closures affect many thousands of lives of employees, suppliers etc. and create a disruption in the

social fabric and the marketing system. Therefore, one element that bestows legitimacy on profit

is its connection to the very existence and growth of the business enterprise. However, is the

existence of the business a sufficient justification as to the legitimacy of profit?

The Merriam-Webster (2023) dictionary lists several definitions for the word “legitimate.” Some

of these include “lawfully begotten;” “being exactly as intended or presented;” “genuinely good,

impressive, or capable of success;” “accordant with law or with established legal forms and

requirements;” “conforming to recognized principles or accepted rules and standards;” etc. While

the term “legitimate profit” has an element of being in accordant with the law, its usage in

Catholic social teaching is better aligned with conforming to recognized principles of accepted

rules and standards. In this paper, we explore these accepted rules or standards in Catholic social

teaching that lend legitimacy to the “profit” dimension of a business enterprise. First, to be clear,

our usage of the word “profit” relates to the financial bottom line of the business. Our focus here

is on for-profit businesses. It is possible that there might be different conceptualizations of profit

in not-for-profit or social enterprises or even indigenous contexts. However, that discussion is

beyond the scope of this paper. We begin with a quick overview of Catholic social teaching

(CST) and then discuss what in our opinion are four criteria that Pope Francis provides us to

evaluate the legitimacy of profit. We then connect the notion of legitimate profit with

macromarketing, using the concept of socially responsible marketing (Laczniak and Shultz 2021)

as the prism.

Catholic social teaching: A brief overview

Catholic social teaching (CST) comprises of all the official writings of the Catholic church

regarding social issues. While CST is rooted in the Christian scriptures and the teachings of

prominent Catholic theologians over the years, a generally accepted starting point is the

encyclical of Pope Leo XIII (1891) titled Rerum Novarum. This encyclical addressed some of the

abuses of the Industrial Revolution that were an affront to human dignity. Since Rerum

Novarum, over the course of the last 132 years, the church has issued a number of documents

26

that address varied social issues. Prominent among these are Quadragesimo Anno (Pope Pius XI

1931); Mater et Magistra (Pope John XXIII 1961); Pacem in Terris (Pope John XXIII 1963);

Populorum Progressio (Pope Paul VI 1967); Octogesima Adveniens (Pope Paul VI 1971);

Laborem Exercens (Pope John Paul II 1981); Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (Pope John Paul II 1987);

Centesimus Annus (Pope John Paul II 1991); Caritas in Veritate (Pope Benedict XVI 2009); and

Laudato Si’ (Pope Francis 2015). At the heart of the corpus of CST are four foundational

principles also called the permanent principles of CST. These are: the dignity of the human

person; the common good; subsidiarity; and solidarity. The United States Conference of Catholic

Bishops (2023) list seven key themes of CST. These are: (1) Life and dignity of the human

person; (2) Call to Family, Community, and Participation; (3) Rights and Responsibilities; (4)

Option for the Poor and Vulnerable; (5) The Dignity of Work and the Rights of Workers; (6)

Solidarity; and (7) Care for God’s Creation.

An encyclical of special importance is Centesimus Annus (Pope John Paul II 1991) which states

that “the Church acknowledges the legitimate role of profit as an indication that a business is

functioning well” [emphasis in original]. However, the encyclical adds “but profitability is not

the only indicator of a firm’s condition…..In fact, the purpose of the firm is not simply to make a

profit, but is found in its very existence as a community of persons who in various ways are

endeavouring to satisfy their basic needs, and who form a particular group at the service of the

whole of society.” The encyclical calls on businesses to consider other human and moral factors

together with profit which are also important for the life of the business. Here the legitimacy of

profit draws from it being an indicator of a well-functioning business. In the encyclical Caritas

in Veritate Pope Benedict (Benedict 2009) states that “once profit becomes the exclusive goal, it

is produced by improper means and without the common good as its ultimate end, it risks

destroying wealth and creating poverty.” Pope Francis (Francis 2022) goes a step further by

providing us with criteria to evaluate the legitimacy of profit. We elaborate on these in the

section below.

The legitimacy of profit

Pope Francis (Francis 2022) during his address to the participants of the meeting of Deloitte

Global lists four criteria to evaluate the legitimacy of profit: (a) Integral promotion of the human

person; (b) Universal destination of goods; (c) Preferential option for the poor; and (d) care for

our common home. The first three were mentioned in a document published by the Congregation

for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development

(Vatican 2018) to which Pope Francis adds the 4

th

, namely, care for our common home.

Integral promotion of the human person: A foundational principle of CST is that of the dignity

of the human person (Pope John XXIII 1961; Vatican 2004). This dignity is not something that is

merited or acquired by one’s efforts but rather is a given (Santos and Laczniak 2009). In keeping

with such dignity, it becomes imperative to create structures that help the development of the

individual. In fact, “the integral development of every person, of every human community, and

of all people, is the ultimate horizon of the common good that the Church…. seeks to advance”

(Vatican 2018).

Universal destination of goods: The foundation of the universal destination of goods is that “the