{222A0E69-13A2-4 985-84AE-73 CC3DFF4D02}- R-008032105221 177189069140 163240174026 137243109106 085049077141 004149130129 188203094057 074101083247 146168153139 200124182177 222251152205 059027058130 234162224095 078110005195 194254015010 215024003224 2180962430 72073120206039 198220006210 048221125141

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Randy Alison Aussenberg

Specialist in Nutrition Assistance Policy

Updated September 28, 2018

Congressional Research Service

7-5700

www.crs.gov

R45147

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service

Summary

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the nation’s largest domestic food

assistance program, serving over 42.1 million recipients in an average month at a federal cost of

over $68 billion in FY2017. SNAP is jointly administered by state agencies, which handle most

recipient functions, and the federal government—specifically, the U.S. Department of

Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS)—which supports and oversees the states

and handles most retailer functions. In a program with diverse stakeholders, detecting, preventing,

and addressing errors and fraud is complex. SNAP has typically been reauthorized in a farm bill

approximately every five years; this occurred most recently in 2014 (P.L. 113-79). Policymakers

have long been interested in reducing fraud and improving payment accuracy in the program.

Provisions related to these goals have been included in past farm bill reauthorizations and may be

considered for the next farm bill, expected in 2018.

There are four main types of inaccuracy and misconduct in SNAP:

Trafficking SNAP benefits is the illicit sale of SNAP benefits, which can involve

both retailers and recipients.

Retailer application fraud generally involves an illicit attempt by a store owner

to participate in SNAP when the store or owner is not eligible.

Errors and fraud by households applying for SNAP benefits can result in

improper payments. Errors are unintentional, while fraud is the intentional

violation of program rules.

Errors and fraud by state agencies—agency errors can result in inadvertent

improper payments; the discussion of agency fraud largely focuses on certain

states’ Quality Control (QC) misconduct.

Certain key ideas are fundamental to any discussion of SNAP errors and fraud:

Errors are not the same as fraud. Fraud is intentional activity that breaks federal

and/or state laws, while errors can be the result of unintentional mistakes. Certain

acts, such as trafficking SNAP benefits, are always considered fraud; other acts,

such as duplicate enrollment, may be the result of either error or fraud depending

on the circumstances of the case.

SNAP fraud is relatively rare, according to available data and reports.

There is no single measure that reflects all the forms of fraud in SNAP. There are

some frequently cited measures that capture some parts of the issue, and there are

relevant data from federal and state agencies’ enforcement efforts.

The most frequently cited measure of fraud is the national retailer trafficking rate, which,

estimated that 1.5% of SNAP benefits redeemed from FY2012-FY2014 were trafficked. While

the national retailer trafficking rate (which is issued roughly every three years) estimates the

extent of retailer trafficking, there is not a standard recipient trafficking rate, nor is there an

overall recipient fraud rate.

USDA-FNS is responsible for identifying stores engaged in retailer trafficking—using transaction

data analysis, undercover investigations, and other tools—and imposing penalties on store owners

who commit violations. Retailers found to have trafficked may be subject to permanent

disqualification from participation in SNAP, fines, and other penalties. USDA-FNS also works to

identify fraud by retailers applying to accept SNAP benefits. Retailers found to have falsified

their applications may be subject to denial, permanent disqualification, and other penalties.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service

While retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud are primarily pursued by a single federal

entity (USDA-FNS), recipient violations (i.e., recipient trafficking and recipient application

fraud) are pursued by 53 different state agencies. Recipients found to have trafficked may be

required to repay the amount trafficked and may be subject to disqualification from receiving

SNAP benefits and other penalties. State agencies’ efforts to reduce and punish recipient fraud

vary, which is evident, for instance, in state-submitted data on recipient disqualification activities.

The national payment error rate (NPER) is the most-cited measure of nationwide payment

accuracy. Using USDA-FNS’s Quality Control (QC) system, the NPER estimates states’ accuracy

in determining eligibility and benefit amounts. The NPER has limitations, though; for instance, it

only reflects errors above a threshold amount ($38 in FY2017). After publishing a FY2014

NPER, USDA Office of the Inspector General (OIG ) and USDA-FNS identified data quality

issues that prevented the publication of an NPER in FY2015 and FY2016, but USDA-FNS

published a NPER for FY2017 in June 2018. For FY2017, it was estimated that 6.30% of SNAP

benefit issuance was improper—including a 5.19% overpayment rate and a 1.11% underpayment

rate. Regardless of the cause of an overpayment, SNAP agencies are required to work toward

recovering excess benefits from households that were overpaid (this is referred to as “establishing

a claim against a household”). Applying these rates to benefits issued in FY2017 (over $63.6

billion), an estimated $3.30 billion in benefits were overpaid, and about $710 million in benefits

were underpaid.

Overpayments and underpayments to households can be the result of recipient errors, recipient

fraud, or agency errors during the certification process. State agencies rely on household-provided

information in applications, but also employ a range of data matches—some required by federal

law, some optional that vary by state—to promote accuracy and double-check information.

According to the USDA-FNS FY2016 State Activity Report, of states’ established claims for

overpayment, approximately 62% of overpayment claim dollars were for recipient errors, about

28% were for agency errors, and about 11% were due to recipient fraud.

In addition to inadvertent agency errors, state agencies and their agents have been involved in

isolated instances of fraud. Beyond cases of fraud conducted by state agency employees for

personal gain, in FY2017 the Department of Justice obtained False Claim Act settlements from

three state agencies accused of falsifying their Quality Control data and unlawfully obtaining

federal bonuses. Investigations into this matter, conducted by the USDA-OIG, are ongoing.

Across all types of fraud, oversight entities such as the Government Accountability Office and

USDA-OIG have identified issues and strategies relevant to combating errors and fraud in SNAP.

USDA-FNS has also proposed related regulatory changes that were not finalized. On the retailer

side, issues identified focus on opportunities to prevent and more promptly punish trafficking. On

the recipient side, issues identified include the nonexistence of a recipient fraud rate, states’varied

levels of anti-fraud efforts (which may be better incentivized), and improvements to data

matching in the application process. During the 115

th

Congress, Members voted on farm bill

proposals that contained some changes to SNAP program integrity policy; these proposals are

summarized in CRS Report R45275, The House and Senate 2018 Farm Bills (H.R. 2): A Side-by-

Side Comparison with Current Law.

Changes that might strengthen payment accuracy and punishments against fraud can be in tension

with other policy objectives such as preserving recipient access to the program, and may have

unintended consequences such as incurring costs greater than their savings. Balancing program

objectives such as these are considerations for policymakers in this area.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Types of Errors and Fraud ............................................................................................................... 2

Trafficking: Retailer and Recipient ........................................................................................... 3

Retailer Application Fraud ........................................................................................................ 3

Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households ................................................................ 4

Recipient Errors .................................................................................................................. 4

Recipient Application Fraud ............................................................................................... 4

Agency Errors ..................................................................................................................... 5

Fraud Conducted by State Agencies or Their Agents ................................................................ 5

State Agency Employee Fraud ............................................................................................ 5

State Agency Fraud ............................................................................................................. 5

Extent of Errors and Fraud .............................................................................................................. 5

Extent of Retailer Trafficking ................................................................................................... 5

Extent of Retailer Application Fraud ........................................................................................ 7

Extent of Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households ................................................ 8

National Payment Error Rate .............................................................................................. 8

Differentiating Between Recipient Fraud, Recipient Errors, and Agency Errors ............. 10

Detection and Correction of Errors and Fraud .............................................................................. 13

Retailer Fraud .......................................................................................................................... 14

Detection of Retailer Trafficking ...................................................................................... 14

Correction of Retailer Trafficking ..................................................................................... 15

Detection of Retailer Application Fraud ........................................................................... 17

Correction of Retailer Application Fraud.......................................................................... 17

Errors in Benefit Issuance to Households ............................................................................... 17

Detection of Recipient Errors—Data Matching ................................................................ 17

Detection of Agency Errors .............................................................................................. 21

Correction of Recipient and Agency Errors—Claims ....................................................... 21

Recipient Fraud ....................................................................................................................... 22

Detection of Recipient Fraud ............................................................................................ 22

Correction of Recipient Fraud .......................................................................................... 23

State Agency Employee Fraud Detection and Correction ....................................................... 25

State Agency Fraud: SNAP Quality Control ................................................................................. 25

Quality Control: Incentives and Penalties Overview .............................................................. 25

State Agency Misreporting and Falsification of Quality Control Data ................................... 27

Combating Errors and Fraud: Issues and Strategies ...................................................................... 29

Retailer Trafficking ................................................................................................................. 29

Certain Store Owners Remain Active in SNAP Despite Permanent

Disqualification for Trafficking ..................................................................................... 29

Strengthening Monetary Penalties against Trafficking Retailers ...................................... 30

Changes in EBT Transaction Processing since 2014 ........................................................ 31

Enhancing Retailer Stocking Standards ............................................................................ 32

Suspending “Flagrant” Retailer Traffickers ...................................................................... 33

Increasing Requirements for High-Risk Stores ................................................................ 33

Recipient Trafficking............................................................................................................... 34

Requiring Recipient Photographs on EBT Cards.............................................................. 34

State Agency Reporting on Recipient Fraud ..................................................................... 35

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service

Enhancing Federal Financial Incentives for State Agencies to Fight Fraud ..................... 36

Federal Oversight of State Agencies—Management Evaluations (MEs) ......................... 36

Delayed State Agency Notification of Retailer Trafficking Cases .................................... 37

Difference in Burden of Proof for Retailer Trafficking versus

Recipient Trafficking ..................................................................................................... 37

Best Practices for Fighting Recipient Fraud—the SNAP Fraud Framework .................... 38

Retailer Application Fraud ...................................................................................................... 38

Verification and Use of Retailer Submitted Social Security Numbers (SSNs) ................. 38

Other Verification of Retailer Submitted Information ...................................................... 39

Mandating Background Checks on High-Risk Retailer Applications ............................... 39

Additional Retailer Application Vulnerabilities Identified in 2012 and 2013

USDA-FNS Proposed Rules .......................................................................................... 40

Recipient Application Errors and Fraud .................................................................................. 41

Establish Federal Incentives to Conduct Pre-certification Investigations ......................... 41

Difficulties in Collecting Amounts Overpaid to or Trafficked by Recipients ................... 41

Duplicate Enrollment and the National Accuracy Clearinghouse (NAC) ........................ 42

Considerations for Data Matching .................................................................................... 44

State Agency Errors and Fraud................................................................................................ 45

Modifying State Involvement in the Quality Control System .......................................... 45

Figures

Figure 1. Authorization and Trafficking at Convenience Stores, 2006-2014 .................................. 7

Figure 2. Claims Establishment by Type, FY2007-FY2016 ......................................................... 13

Figure 3. Data Matching in SNAP Certification ........................................................................... 18

Figure 4. Per Capita Recipient Disqualifications in States ............................................................ 24

Figure 5. Claims Established and Claims Collected as Shares of Estimated Dollars

Overissued, FY2005-FY2014 .................................................................................................... 42

Tables

Table 1. National Payment Error Rate, FY2011-FY2014, FY2017 .............................................. 10

Table 2. Bonuses Awarded to States for High Payment Accuracy, FY2014 .................................. 26

Table 3. Penalties Repaid by States for Low Payment Accuracy, FY2005-FY2014 ..................... 27

Table B-1. Inactive USDA-FNS Rulemaking Actions Related to SNAP Integrity ....................... 48

Table D-1. Convenience Stores as a Percentage of All Stores in SNAP ....................................... 52

Table D-2. Trafficking Rates in Convenience Stores Compared to the

National Trafficking Rates ......................................................................................................... 52

Table D-3. Convenience Store Redemptions and Trafficking as a Percentage of

All Redemptions and Trafficking ............................................................................................... 53

Table E-1. State Payment Error Rates, FY2010 to FY2014 .......................................................... 54

Table E-2. State Bonuses and Liabilities, FY2010 to FY2014 ...................................................... 56

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service

Appendixes

Appendix A. Glossary of Abbreviations ........................................................................................ 46

Appendix B. “Inactive” USDA-FNS Rules ................................................................................... 48

Appendix C. Optional Income Data Matches ................................................................................ 50

Appendix D. Trends in Retailer Trafficking and Convenience Store Participation in

SNAP .......................................................................................................................................... 52

Appendix E. Payment Error Rate Information .............................................................................. 54

Contacts

Author Contact Information .......................................................................................................... 58

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 1

Introduction

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the nation’s largest domestic food

assistance program, serving about 42.2 million recipients in an average month at a federal cost of

over $68 billion in FY2017.

1

It is jointly administered by the federal government and the states

and provides means-tested benefits to recipients who are deemed eligible. These benefits may be

used only for eligible foods at any of the approximately 260,000 authorized retailers, which range

from independent corner stores to national chain supermarkets.

2

In a program that operates with

so many different stakeholders, detecting, preventing, and addressing errors and fraud is a

complex undertaking. Among the complexities are the monitoring of retailer acceptance and

recipient use of benefits, the accuracy of information provided by applicant households, and

states’ performance administering the program. Many governmental entities—federal and state

agencies, including both human services and law enforcement—play a role in efforts to detect,

prevent, and punish fraudulent SNAP activities and to reduce inadvertent errors.

SNAP has typically been reauthorized in a farm bill approximately every five years; this occurred

most recently in 2014 (P.L. 113-79).

3

Policymakers have long been interested in reducing fraud

and improving accuracy in the program, and provisions related to these goals are frequently

included in farm bills. In preparation for the next farm bill, up for reauthorization in September

2018, policymakers have again begun to discuss error and fraud in the program.

4

The Trump

Administration has also announced related policy changes.

5

At the same time, some policymakers

defend the program against criticism of its integrity.

6

To help policymakers navigate this complex set of policy issues, this report seeks to define terms

related to errors and fraud; identify problems and describe what is known of their extent;

summarize current policy and practice; and share recommendations, proposals, and pilots that

have come up in recent years. The report answers several questions around four main types of

inaccuracy and misconduct: (1) trafficking SNAP benefits (by retailers and by recipients); (2)

retailer application fraud; (3) errors and fraud in SNAP household applications; and (4) errors and

fraud committed by state agencies (including a discussion of states’ recent Quality Control (QC)

misconduct). The report then discusses challenges to combating errors and fraud—across the four

areas—and potential strategies for addressing those challenges.

1

Average monthly participation data and total program cost for FY2017 are from the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) administrative data.

2

For basic information on SNAP eligibility rules, benefit calculation, and benefit redemption, see CRS Report R42505,

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A Primer on Eligibility and Benefits, by Randy Alison

Aussenberg.

3

For background, see CRS In Focus IF10663, Farm Bill Primer: SNAP and Other Nutrition Title Programs, by Randy

Alison Aussenberg.

4

See Chairman K. Michael Conaway, Past, Present, and Future of SNAP: Hearing Series Findings: 114

th

Congress,

House Committee on Agriculture, December 7, 2016, pp. 38-48, https://agriculture.house.gov/UploadedFiles/

SNAP_Report_2016.pdf.

5

For information regarding these policy changes, see, for example: December 5, 2017, USDA press release,

https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2017/12/05/usda-promises-new-snap-flexibilities-promote-self-sufficiency;

and December 8, 2017, USDA press release: https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2017/12/08/usda-clears-

arizona-test-snap-fraud-prevention-improvement.

6

See, for example, Representative Jim McGovern, “U.S. Rep. McGovern’s 18

th

End Hunger Now Speech: Fraud,

Waste, Abuse,” press release, July 17, 2013, https://mcgovern.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=

396547.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 2

Certain key ideas that are fundamental to discussion of SNAP errors and fraud are explored

further in the report:

Errors are not the same as fraud. Fraud is intentional activity that breaks federal

and/or state laws, but there are also ways that program stakeholders—particularly

recipients and states—may inadvertently err, which could affect benefit amounts.

Certain acts, such as trafficking, are always considered fraud, but other acts, such

as duplicate enrollment, may be the result of either error or fraud depending on

the circumstances of the case.

SNAP fraud is relatively rare, according to available data and reports. While this

report discusses illegal or inaccurate activities in SNAP, they represent a

relatively small fraction of SNAP activity overall.

There is no single data point that reflects all the forms of fraud in SNAP. The

most frequently cited measure of fraud is a national estimate of retailer

trafficking, which is a significant, but not the only, type of fraud in the program.

While retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud are pursued primarily by a

single federal entity, recipient violations are pursued by 53 different state

agencies. This leads to disparate approaches and disparate reporting.

7

The national payment error rate (NPER) is the most-often cited measure of

nationwide SNAP payment accuracy, but it has limitations. For example, it only

reflects errors above an error tolerance threshold.

Policies to reduce fraud and increase accuracy can be in tension with other policy objectives, and

may have unintended consequences. Policies that make retailer authorization more onerous, for

instance, have the potential to decrease participants’ access to SNAP-authorized stores. Making

eligibility determinations more complex for recipients can impede recipients’ access to the

program and could strain states’ eligibility determination operations. Implementing better data

collection and accountability systems could require more staff and could incur more costs than it

reduces.

This report provides a foundation for discussing error and fraud in SNAP and for evaluating

policy proposals. It does not make independent CRS findings, but rather synthesizes the many

available resources on error and fraud in SNAP. It relies, in particular, on reports and data from

the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) as well

as the published audits of the USDA’s Office of the Inspector General (USDA-OIG) and the

Government Accountability Office (GAO). For a list of abbreviations used in this report, see

Appendix A.

Types of Errors and Fraud

This section defines each of the types of intentional fraud and unintentional errors committed by

recipients, retailers, and state agencies, including retailer trafficking (fraud), recipient trafficking

(fraud), retailer application fraud, recipient application fraud, recipient errors, agency errors, state

agency employee fraud, and state agency fraud.

7

50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands administer SNAP.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 3

Trafficking: Retailer and Recipient

USDA-FNS is responsible for administering the retailer side of SNAP and for pursuing retailer

fraud; while states are responsible for administering the recipient side of SNAP (with federal

oversight) and for pursuing recipient fraud.

8

“Trafficking” usually means the direct exchange of

SNAP benefits (formerly known as food stamps) for cash, which is illegal, and both retailers and

recipients can engage in this form of fraud.

9

Although SNAP benefits have a dollar value, they are

not the same as cash because they can only be spent on eligible food for household consumption

at authorized stores equipped with Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) point of sale (POS)

machines.

10

Trafficking can also include the exchange of SNAP benefits for controlled

substances, firearms, ammunition, or explosives.

11

Additionally, trafficking includes indirect

exchanges, such as obtaining cash refunds for products purchased with SNAP benefits or

reselling products purchased with SNAP benefits. Trafficking SNAP benefits includes recipient

trafficking and retailer trafficking. Retailer trafficking of SNAP benefits usually occurs when a

SNAP recipient sells their benefits for cash, often at a loss, to an owner or employee of a store

participating in SNAP.

12

Recipient trafficking usually coincides with retailer trafficking, but it

may take other forms (e.g., if a recipient were to sell their benefits, or food purchased with

benefits, to another individual). Trafficking is one of the most serious forms of SNAP fraud, and

although it does not increase costs to the federal government (as overpayments do), it does divert

federal funds from their intended purpose.

Retailer Application Fraud

Retailers misrepresenting themselves or circumventing disqualification in the application process

can be a source of fraud. To obtain SNAP authorization, applicant retailers must meet certain

requirements, including stocking

13

and business integrity standards.

14

When a retailer initially

applies to receive authorization to participate in SNAP or applies for reauthorization to continue

SNAP participation,

15

the store owner must submit personal and business information and

documentation to USDA-FNS in order to verify eligibility for SNAP participation. If a retailer

8

Sections 9, 12, and 15 of the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008 (FNA) outline the requirement that USDA-FNS

administer SNAP on the retailer side; Section 11 outlines the requirement that states administer SNAP on the recipient

side.

9

For the full definition of trafficking, see 7 C.F.R. §271.2.

10

Stores authorized to participate in SNAP are required to ensure that SNAP benefits are accepted as payment only for

eligible food. Many, but not all, stores ensure compliance by programming their point of sale systems to recognize the

SNAP eligibility of products at the checkout counter, thereby preventing the use of SNAP benefits to pay for ineligible

products.

11

Controlled substances as defined at 21 U.S.C. §802.

12

For example, a recipient swipes their SNAP EBT card for a $20 purchase transaction, but rather than receiving $20

of eligible food, the recipient obtains $10 in cash from the store owner. The total amount of the transaction ($20) is

deposited into the store owner’s bank account. In this example, both the recipient and retailer are engaged in trafficking

SNAP benefits.

13

SNAP stocking standards may be met with either a range of different staple foods on hand or documentation

reflecting more than 50% of store sales in staple foods. For more information, see CRS Report R42505, Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A Primer on Eligibility and Benefits, by Randy Alison Aussenberg.

14

SNAP business integrity standards require that store owners do not have a history of certain convictions, civil

judgments, and violations. Section 9(a)(1)(D) of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2018(a)(1)(D) and implemented at 7

C.F.R §278.1(b)(3)).

15

Stores participating in SNAP must apply for reauthorization on a regular basis. Depending on risk level and other

factors, stores are reconsidered on reauthorization cycles that vary from one to five years.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 4

deliberately submits false or misleading information of a substantive nature in order to receive

SNAP authorization despite their ineligibility, then they have committed falsification—retailer

application fraud.

16

Another kind of retailer application fraud involves a store owner attempting to

circumvent disqualification from SNAP by engaging in a purported sale or transfer of ownership

of their store to a spouse or relative; after which the new purported owner applies to participate in

SNAP, claiming that the former disqualified owners are no longer associated with the store. This

practice is often referred to as “straw ownership,” and USDA-FNS does not consider such sales

or transfers of ownership to be bona fide.

17

Such actions by the disqualified retailer are

considered circumvention—retailer application fraud.

18

Retailer application fraud does not

increase costs to the federal government (as overpayments can), but it does enable retailers who

may be more likely to engage in trafficking to enter the program.

Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households

In addition to retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud, errors and fraud can arise in

determining eligibility and benefit amounts for recipients.

Recipient Errors

When a household initially applies to receive or recertifies to continue receiving SNAP benefits,

the applicant household must submit personal information and documentation to their state

agency for eligibility determination, and for benefit calculation if found to be eligible. During this

application process, an applicant may misunderstand SNAP rules, make a miscalculation,

otherwise unintentionally provide incorrect information, or accidentally omit certain information.

If this error results in an overpayment to the household and there is no proof that this error was

intentional, then this error is designated as an inadvertent household error (IHE).

19

Recipient Application Fraud

If an applicant is found to have intentionally submitted false or misleading information during the

initial application or recertification process that leads to an incorrect eligibility or allotment

determination (resulting in an overpayment), then that applicant has committed an intentional

program violation (IPV)—recipient application fraud.

20

16

Examples of falsification include providing USDA-FNS with a fake Social Security Number (SSN) for a store

owner, untruthfully attesting that a store owner had never been convicted of a crime, or providing forged records

indicating an inventory of foodstuffs not stocked at the store.

17

A “straw owner” is an individual who legally owns property, or has the legal appearance of owning property, on

behalf of another individual, sometimes for a fee. Typically, such arrangements are conducted solely to hide the

identity of the effective owner.

18

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Inspector General, FNS: Controls for Authorizing Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program Retailers, Audit Report 27601-0001-31, July 2013, pp. 3-4, https://www.usda.gov/oig/

webdocs/27601-0001-31.pdf (hereinafter cited as “July 2013 USDA-OIG report”).

19

Inadvertent household errors are sometimes referred to as unintentional program violations (UPVs).

20

This is also referred to as “eligibility fraud” although recipient application fraud can involve recipients falsifying

information pertaining to eligibility as well as income. See Section 6(b) of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2015(b) and

implemented at 7 C.F.R. §273.16).

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 5

Agency Errors

SNAP overpayments or underpayments that are not the result of recipient actions (i.e., not the

result of recipient errors or recipient fraud) are generally the result of agency errors (AEs).

21

Agency errors include overpayments or underpayments caused by the action of, or failure to take

action by, any representative of a state agency.

Fraud Conducted by State Agencies or Their Agents

“State agency employee fraud” and “state agency fraud” are not terms defined in statute,

regulation, or agency guidance. As used in this report, “state agency employee fraud” and “state

agency fraud” include forms of fraud often referred to as “insider threats”—a threat to SNAP

integrity that comes from within entities that administer SNAP (i.e., state agencies).

State Agency Employee Fraud

State agency employee fraud is any intentional effort by state employees to illegally generate and

benefit from SNAP overpayments. State agency employee fraud usually involves eligibility

workers who abuse their positions and access to the SNAP certification process in order to

unlawfully generate SNAP accounts that materially benefit individuals not entitled to such

benefits.

State Agency Fraud

State agency fraud is any intentional effort by state officials to mislead USDA-FNS or other

federal authorities in order to illegally obtain federal funds or avoid federal monetary penalties.

State agency fraud cases are very infrequent and generally center on a state’s falsification of

program-related data. Of interest to policymakers, the state agency fraud case examined in this

report, first identified in 2017, deals with multiple states’ falsification of Quality Control (QC)

data in order to obtain monetary bonuses and avoid monetary penalties, with some actions dating

back to 2008.

22

(For more information, see “State Agency Fraud: SNAP Quality Control.”)

Extent of Errors and Fraud

Extent of Retailer Trafficking

USDA-FNS publishes an annual report that summarizes their annual administrative activities

pertaining to retailers participating in SNAP,

23

including detailed retailer data on participation and

redemptions, retailer applications and authorizations, investigations and sanctions, and

administrative review. According to this Retailer Management Report, in FY2016 there were

260,115 retailers participating in SNAP, and USDA-FNS permanently disqualified 1,842 stores

for retailer trafficking (less than 1% of all

stores).

24

Roughly every three years, USDA-FNS

publishes a study estimating the extent of

retailer trafficking in SNAP over about three

years of SNAP redemption data. The retailer

trafficking studies referenced in this report were

issued in 2017 (covering 2012-2014), 2013

National Retailer Trafficking Rate

25

The most recent trafficking study (analyzing 2012-

2014 data) estimated that 1.50% of all SNAP benefits

redeemed were trafficked (sold for cash or

exchanged illegally) at stores. This is up from an

estimated 1.34% in the 2009-2011 study. This only

reflects one type of fraud—retailer trafficking.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 6

(covering 2009-2011), and 2011 (covering 2006-2008).

26

By examining a representative sample,

these studies determined two national rates that reflect the prevalence of retailer trafficking. The

national retailer trafficking rate represents the proportion of SNAP redemptions at stores that

were estimated to have been trafficked. The national store violation rate represents the proportion

of authorized stores that were estimated to have engaged in trafficking.

The national retailer trafficking rate is the most-cited measure of fraud in SNAP, although it does

not capture all types of fraud (i.e., it represents only retailer trafficking). According to the

September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, the national retailer trafficking rate for

2012-2014 was 1.50%, up from 1.34% in the 2009-2011 study.

27

This means that, during this

period, USDA-FNS estimates that 1.50% of all SNAP benefits redeemed were trafficked at

participating stores. This constitutes about $1.1 billion in estimated benefits trafficked each year

at stores during this period.

28

Additionally, this study estimated that the national store violation

rate for this period was 11.82%, up from 10.47% in the 2009-2011 study.

29

This means that,

during this period, USDA-FNS estimates that 11.82% of all SNAP-authorized retailers engaged

in retailer trafficking at least once.

The September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study found that the increase in retailer

trafficking was due to increased program participation by smaller stores, which have a higher rate

of retailer trafficking. While stores enter and leave the program from year to year, the overall

growth in SNAP-authorized stores over the last 10 years (FY2007-FY2016) was about 93,000,

and about 63% of this growth came from convenience stores in the program (see Table D-1 in

Appendix D).

30

As of FY2016, convenience stores constitute about 46% of all stores in the

program, up from 36% in FY2007.

31

According to the September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer

Trafficking Study, covering 2012-2014, convenience stores account for about 5% of total SNAP

redemptions, but about 57% of retailer trafficking (see Table D-3 in Appendix D).

32

Also

21

Agency errors are sometimes called “administrative errors.”

22

U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), “Wisconsin Department of Health Services Agrees to Pay Nearly $7 Million to

Resolve Alleged False Claims for SNAP Funds,” press release, April 12, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/

wisconsin-department-health-services-agrees-pay-nearly-7-million-resolve-alleged-false-claims.

23

Retailer Management Reports are available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap-retailer-data.

24

This comes to about 0.71% of total stores participating in the program in FY2016. This CRS calculation is based on

data provided in an email from SNAP, USDA-FNS, October 25, 2017.

25

Joseph Willey, Nicole B. Fettig, and Malcolm Hale, The Extent of Trafficking in the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program: 2012–2014, prepared by WRMA, Inc. for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition

Service, September 2017, pp. ii-9, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/extent-trafficking-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-

program-2012%E2%80%932014 (hereinafter cited as “September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study”).

26

These three studies can be found online at https://www.fns.usda.gov/report-finder.

27

September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, pp. ii-9.

28

SNAP benefit redemptions in FY2012, FY2013, and FY2014 were about $75 billion, $76 billion, and $70 billion,

respectively.

29

September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, p. 17.

30

This CRS calculation is based on data provided in an email from SNAP, USDA-FNS, January 5, 2018. USDA-FNS

categorizes retailers into “store types” (e.g., “convenience store”) according to definitions in an internal agency

document. Store types are largely defined by volumes of sales, size, and other business characteristics.

31

This CRS calculation based on data provided in an email from SNAP, USDA-FNS, January 5, 2018, and from U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, 2016 Retailer Management Year End Summary Report,

December 2016, p. 1, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/snap/2016-SNAP-Retailer-Management-Year-

End-Summary.pdf (hereinafter cited as “December 2016 USDA-FNS Retailer Management Report”).

32

This CRS calculation based on data from September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, p. 9.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 7

according to this study, about 18% of all SNAP benefits used at authorized convenience stores are

trafficked by these stores (i.e., the convenience store trafficking rate), and about 19% of all

authorized convenience stores are engaged in trafficking (i.e., the convenience store violation

rate).

33

These rates are significantly higher than the national rates for all stores (see Table D-2 in

Appendix D). The increase in SNAP participation by smaller stores appears to correlate to an

overall increase in retailer trafficking, according to USDA-FNS.

34

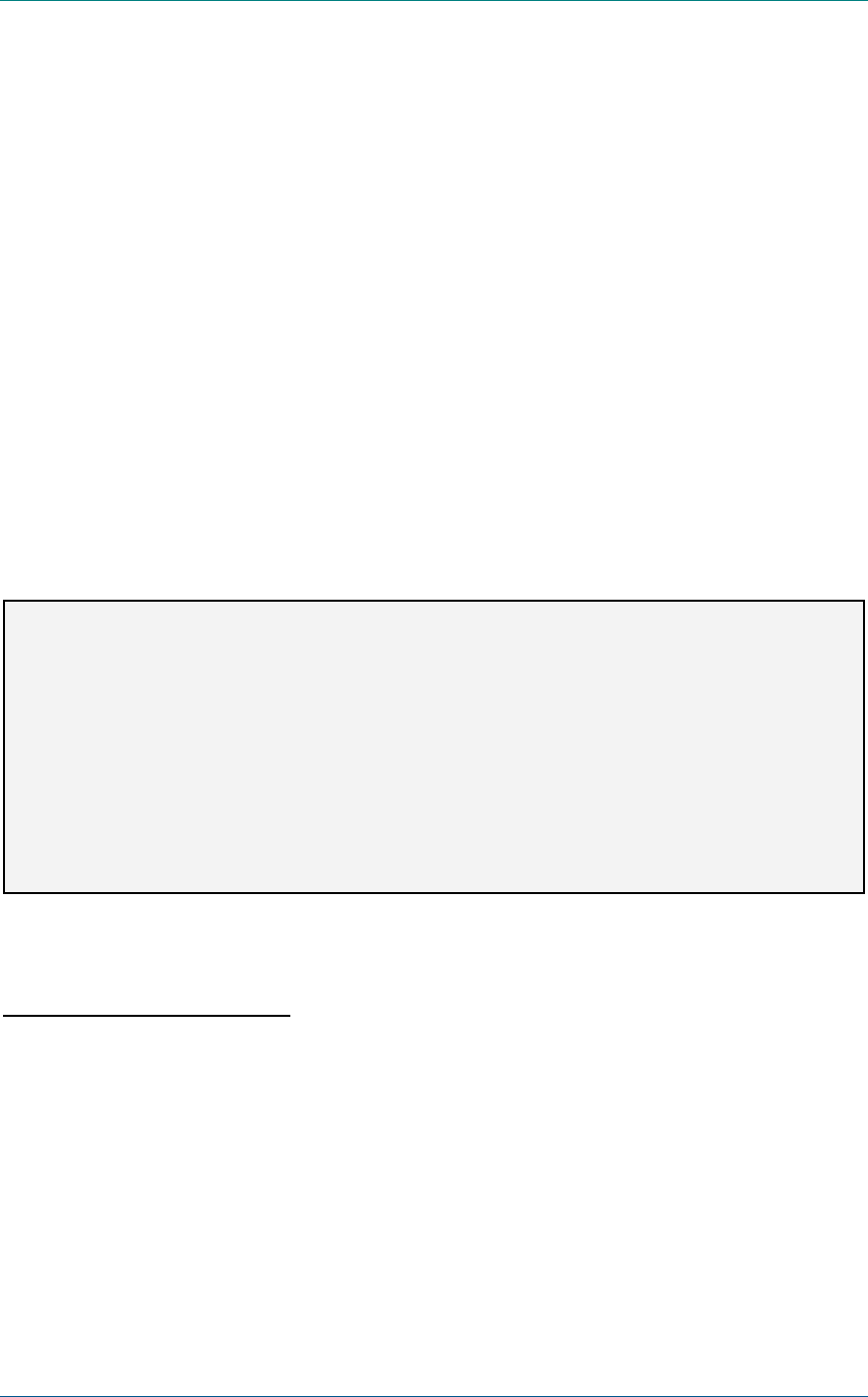

Figure 1 displays some of

these data from the three most recent trafficking studies.

Figure 1. Authorization and Trafficking at Convenience Stores, 2006-2014

Source: The three USDA-FNS retailer trafficking studies referenced can be found online using

https://www.fns.usda.gov/report-finder.

Extent of Retailer Application Fraud

There is no standard measure of retailer application fraud. However, USDA-FNS does report

annually on actions taken against business integrity violations, and a retailer engaged in

application fraud (including falsification and circumvention) is generally considered to be in

violation of business integrity standards.

In FY2016, USDA-FNS sanctioned 126 stores for business integrity violations. This number

includes sanctions not related to retailer application fraud and amounts to less than 1 store

sanctioned for every 2,064 stores participating in the program.

35

During the same period, USDA-

FNS permanently disqualified about 15 times as many stores for retailer trafficking.

36

33

September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, p. 9.

34

September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, pp. iii-14.

35

This business integrity sanction total includes stores sanctioned for past convictions as well as retailer application

fraud (i.e., circumvention and falsification). Total FY2016 business integrity sanctions include 25 time-limited denials,

5 time-limited withdrawals, 56 permanent denials, 37 permanent withdrawals, and 3 permanent disqualifications;

December 2016 USDA-FNS Retailer Management Report, p. 5, and email from SNAP, USDA-FNS, October 25, 2017.

36

Total FY2016 permanent disqualifications for retailer trafficking were 1,842. CRS calculations in this paragraph use

data from the December 2016 USDA-FNS Retailer Management Report, pp. 1-8, and email from SNAP, USDA-FNS,

October 25, 2017.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 8

Extent of Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households

National Payment Error Rate

The SNAP Quality Control (QC) system measures improper payments in SNAP. This system was

first established by the Food Stamp Act of 1977.

37

Under the QC system, every state agency

conducts a monthly review of a sample of its households, comparing the amounts of

overpayments and underpayments to total issuance.

38

From this review, state agencies calculate

their state payment error rate (SPER). USDA-FNS conducts annual reviews of a sample of each

state’s reviews to validate state findings and determine national rates—developing the national

payment error rate (NPER).

The NPER is the most-often cited measure of payment accuracy in SNAP.

39

Unlike the national

retailer trafficking rate, the NPER is not a measure of fraud. The NPER reflects improper

payments, but not the cause of these overpayments and underpayments. The NPER estimates all

overpayments and underpayments resulting from recipient errors, recipient application fraud, and

agency error.

40

Per current federal law, only overpayments and underpayments of $38 or more

(inflation-adjusted annually) in the sample month are counted when calculating the payment error

rate—this is called the Quality Control threshold.

41

Additionally, the NPER combines both the

overpayment rate and the underpayment rate, so it does not reflect only excess expenditures. For

example, in FY2017, the NPER was 6.30%—which included a 5.19% overpayment rate and a

1.11% underpayment rate.

42

In discussions regarding SNAP payment accuracy, the NPER is sometimes misunderstood to be a

measure of the federal dollars lost to fraud and waste in the program. The NPER instead reflects

the extent of inaccurate payments that exceed the Quality Control threshold in a given year.

Regardless of the cause of an overpayment, SNAP agencies are required to work towards

recovering excess benefits from households that were overpaid. Recovery of overpayments

involves, first, the establishment (or determination) of a claim against a household, and, second,

the actual collection of that claim. Applying the FY2017 NPER to total benefit issuance, in

FY2017 an estimated $3.3 billion in benefits were overpaid, an estimated $710 million in benefits

37

Section 16 of the 1977 FSA originally established the SNAP QC system; Section 4418-4420 of the Farm Security

and Rural Investment Act of 2002 (the 2002 Farm Bill) and Sections 4019-4021 of the 2014 Farm Bill modified

Section 16 of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2025 and implemented at 7 C.F.R. §275).

38

This statistical sample includes households receiving benefits, as well as households denied, suspended, or

terminated from receiving benefits in the sample month.

39

USDA uses the NPER to measure the payment accuracy of SNAP issuance per the requirements of the Improper

Payments and Elimination and Recovery Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-204); see https://paymentaccuracy.gov/program/

supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program/. Also see CRS Report R43694, Improper Payments in High Priority

Programs: In Brief, by Garrett Hatch.

40

For information regarding the determination of payment error rates, see 7 C.F.R. §275.23(b) & (c).

41

When SNAP agencies detect overpayments and underpayments of less than $38 (inflation adjusted annually), they

still must follow SNAP rules and correct these errors. The Quality Control threshold, also known as the error tolerance

threshold, is only important in the calculation of the payment error rate. The current Quality Control threshold was

most recently set by Section 4019 of the 2014 Farm Bill which modified Section 16(c)(1)(A) of the FNA (codified at 7

U.S.C. §2025(c)(1)(A) and implemented at 7 C.F.R. §275.12(f)(2)). This threshold has been adjusted by statute and

regulation over the years (set at $5 in FY1980, $25 in FY2000, $50 in FY2009, $25 in FY2010, $50 in FY2012, $37 in

FY2014, and most recently $38 in FY2015).

42

The NPER is sometimes called the “combined payment error rate” or the “national performance measure”, and the

NPER is sometimes called the “national payment accuracy rate” when inverted (i.e., 93.70% in FY2017).

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 9

were underpaid.

43

In FY2016, the most recent year available, states established over $684 million

in claims to recover overpayments.

44

Context for Comparing FY2017 NPER to Prior Years

Recent years’ NPERs are listed in Table 1, showing rates from FY2011-FY2014 and then

skipping to FY2017. SNAP national payment error rates were not released by USDA-FNS in

FY2015 or FY2016, due to data quality concerns.

In 2014, USDA found data quality issues in 42 of 53 state agencies’ Quality Control data

reporting. These data quality issues are not, in and of themselves, proof of wrongdoing. In some

cases, states had not followed protocol, while in other cases states had been found to have

deliberately covered up errors (fraudulent actions). (A more detailed discussion of Quality

Control as well as these audits and investigations can be found in “State Agency Fraud: SNAP

Quality Control”). USDA-FNS suspended error reporting for FY2015 and FY2016, and also used

this time to examine and improve state quality control procedures.

45

In June 2018, USDA-FNS published FY2017 state and national error rates (NPER). USDA-

FNS’s accompanying materials describe that this NPER was determined “under new controls to

prevent any recurrence of statistical bias in the QC system,” which includes “a new management

evaluation process to examine state quality control procedures on a regular basis.”

46

The agency

also described that the FY2017 rate stems from “a modernized review process, which includes

updated guidance, revisions to [the relevant FNS handbook], extensive training for State and

Federal staff, and modifications to State procedures to ensure consistency with Federal

guidelines.”

47

As displayed (Table 1) and discussed earlier, the FY2017 NPER of 6.30% is a substantial

increase from the FY2014 of 3.66%. USDA-FNS states the FY2017 rate “is higher than the

previous rate ... but it is more accurate.”

48

However, changes to data collection and related

oversight since FY2014 make it difficult to reliably compare FY2017 rates to earlier years, as it is

possible that earlier years include systemic under-reporting.

43

CRS calculation using USDA-FNS SNAP summary data for FY2017. This data is typically published in USDA-FNS

QC annual reports; the FY2017 report has not been published as of the date of this report.

44

In FY2016, 884,301 claims were established with a total value of $684,187,891, and $402,007,206 in claims were

collected. Claims are established only when an overpayment is detected by the state agency. Claims are not always

established or collected in the year that the overpayment occurred, and there exists large variability between levels of

state claim establishment and collection activity. FY2016 SAR, pp. 32, 34.

45

See, e.g., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service , Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Payment Error Rate, June 29, 2017, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/

files/snap/FY2016-Payment-Error-Rate-Memo.pdf.

46

USDA-FNS, “Fact Sheet: SNAP Payment Error Rate,” June 2018, https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/snap/

QC-FactSheet-2018.pdf.

47

USDA-FNS, “Quality Control,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/quality-control, accessed September 24, 2018.

48

USDA-FNS, “Fact Sheet: SNAP Payment Error Rate,” June 2018, https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/snap/

QC-FactSheet-2018.pdf.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 10

Table 1. National Payment Error Rate, FY2011-FY2014, FY2017

FY2011

FY2012

FY2013

FY2014

FY2017

a

Overpayment

2.99%

2.77%

2.61%

2.96%

5.19%

Underpayment

0.81%

0.65%

0.60%

0.69%

1.11%

NPER

3.80%

3.42%

3.20%

3.66%

6.30%

Source: USDA-FNS QC Annual Reports from the respective fiscal years.

Note: Overpayment and underpayment rates may not total to listed NPER due to rounding.

a. Per USDA-FNS, the agency developed new controls for FY2017 data collection that were not in place in

FY2014.

Differentiating Between Recipient Fraud, Recipient Errors, and Agency Errors

The SNAP overpayment rate (component of the national payment error rate) estimates the extent

of all SNAP overpayments, including overpayments resulting from recipient errors, recipient

fraud, and agency errors (estimated to total about $3.3 billion overpaid in FY2017). The NPER

does not, however, differentiate between the relative extents of each of these types of errors and

fraud (i.e., the NPER cannot tell us what percentage of this $3.3 billion is due to, for example,

agency errors). There is currently no single standard measurement that individually quantifies the

extent of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors. State agencies are, however,

responsible for administering the recipient side of SNAP, and every year states report data on

these activities which USDA-FNS publishes in the SNAP State Activity Report (SAR).

49

This

report includes detailed data on state-level program operations including benefit issuance,

participation, administrative (i.e., non-benefits) costs, recipient disqualification, and claims.

When a recipient error, an act of recipient fraud, or an agency error results in an overpayment to a

household (and that overpayment is detected by the state agency), the household is generally

required by the state agency to repay the overpaid amount (i.e., a claim is established). Data on

the establishment of claims resulting from recipient errors, recipient fraud, and agency errors is

provided in the state report (subdivided by type). The extent of claims establishment, therefore,

can serve as a proxy for the extent of these types of errors and fraud. In addition, when a recipient

commits fraud (and that act of fraud is detected and proven by the state agency), that recipient is

generally punished with disqualification from SNAP. The extent of recipient disqualifications,

therefore, can serve as a proxy for the extent of recipient fraud.

Before examining these claims and disqualification data, however, it is important to understand

the limitations of this approach. Claims are not established in all instances of overpayments

resulting from recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors. For example, claims may not be

established when overpayment amounts fall below state agencies’ claims thresholds

50

or when

overpayments are not detected by state agencies. Likewise, not all acts of recipient fraud are

detected, proven, and punished with disqualification. Also, these claims establishment and

disqualifications data are not based on representative samples and, therefore, these data may not

fully reflect the prevalence of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors in the SNAP

49

State Activity Reports are available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/snap-state-activity-reports.

50

Per SNAP regulation at 7 C.F.R. §273.18(e)(2), the “claims threshold” is the minimum dollar value of overpayments

that must be collected by states. States may establish claims on amounts below this threshold. The claims threshold

applies to overpayments regardless of cause (i.e., recipient error, recipient fraud, or agency error). Since 2000 the

claims threshold has been set at $125.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 11

caseload. Despite these shortcomings, these claims and disqualification data are the only available

measures which reflect, albeit imperfectly, the extent of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or

agency errors in SNAP. The following calculations of the extent of these types of errors and fraud

are based on SNAP State Activity Report FY2016 data including the following: total issuance of

$66,539,351,219; average monthly participation of 21,777,938 households; an average monthly

participation of 44,219,363 persons; total claims established of 884,301; and total claims dollars

established of $684,197,891.

51

Recipient Fraud

Unlike retailer trafficking, which is handled by one federal entity (USDA-FNS), recipient fraud is

detected and punished by 53 different SNAP agencies (50 states, DC, Guam and the U.S. Virgin

Islands) and, as noted in the September 2012 USDA-OIG report, “FNS cannot estimate a

recipient fraud rate because it has not established how States should compile, track, and report

fraud in a uniform manner.”

52

This lack of standardization is a reason why a national recipient

fraud rate does not exist.

53

Both recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud are included

in these figures.

According to the FY2016 SNAP State Activity Report

for every 10,000 households participating in SNAP, about 14 contained a

recipient who was investigated and determined to have committed fraud that

resulted in an overpayment that the state agency required the household to repay

(30,274 claims established);

for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about

$11 were determined by state agencies to have been overpaid due to recipient

fraud and were required to be repaid by the overpaid household ($73,403,758 in

fraud claims established);

about 3% of the total number of claims established were established due to

recipient fraud;

about 11% of the total claims dollars established were established due to

recipient fraud;

for every 10,000 recipients participating in SNAP, about 13 were disqualified

from the program for violating SNAP rules (e.g., committing fraud; 55,930

disqualified);

51

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, State Activity Report Fiscal Year 2016, September

2016, pp. 5-36, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/snap/FY16-State-Activity-Report.pdf (hereinafter cited

as “FY2016 SAR”).

52

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Inspector General, Analysis of FNS’ Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program Fraud Prevention and Detection Efforts, Audit Report 27002-001-13, September 2012, p. 2,

https://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/27002-0011-13.pdf (hereinafter cited as “September 2012 USDA-OIG report”).

53

USDA-FNS has considered developing a level of standardization sufficient to calculate a recipient fraud rate, but in

May 2014 the agency determined that it was not possible without significant investment and oversight. Email from

SNAP, USDA-FNS, November 24, 2017.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 12

about 1.5% of disqualification entries made into the USDA-FNS electronic

Disqualified Recipient System (eDRS)

54

in FY2016 were permanent

disqualifications;

55

and

for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about

$21 were determined by state agencies to have been lost (overpaid due to

recipient application fraud or trafficked) to recipient fraud associated with

disqualified recipients ($136,475,242 in program loss associated with

disqualified recipients).

56

Recipient Errors

According to the FY2016 SNAP State Activity Report

for every 10,000 households participating in SNAP, about 181 were overpaid due

to a recipient error and the state agency required the household to repay the

overpaid amount (394,883 recipient error claims established);

for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about

$63 were determined by state agencies to have been overpaid due to recipient

errors and were required to be repaid by the overpaid household ($421,934,288 in

recipient error claims established);

about 45% of the total number of claims established were established due to

recipient errors;

about 62% of the total claims dollars established were established due to

recipient errors;

about 65% of FY2016 claims were established by four states;

57

about 55% of FY2016 claims amounts were established by these four states; and

these four states accounted for about 30% of SNAP participants.

Agency Errors

According to the FY2016 SNAP State Activity Report

for every 10,000 households participating in SNAP, about 47 were overpaid due

to agency errors, and the state agency required the household to repay the

overpaid amount (459,144 agency error claims established);

for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about

$28 were determined by state agencies to have been overpaid due to agency

errors and were required to be repaid by the overpaid household ($188,859,846 in

agency error claims established);

54

The USDA-FNS-eDRS compiles information regarding recipients disqualified by SNAP state agencies.

55

Email from SNAP, USDA-FNS, January 3, 2018.

56

Per the FY2016 SAR, p. 32, “Some states establish all non-agency error claims as household error claims initially

and then transfer the claim from household error to fraud after the prosecution or [administrative disqualification

hearing] ADH. Therefore, the sum of the fraud associated with disqualifications is a better measure of the ultimate

amount of fraud claims than the newly established amount.”

57

These states are California, Illinois, Texas, and Florida.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 13

about 52% of the total number of claims established were established due to

agency errors;

about 28% of the total claims dollars established were established due to agency

errors;

about 80% of the total number of agency error claims established were

established by California;

58

about 64% of the total agency error claims dollars established were established

by California; and

California accounted for about 10% of SNAP participants.

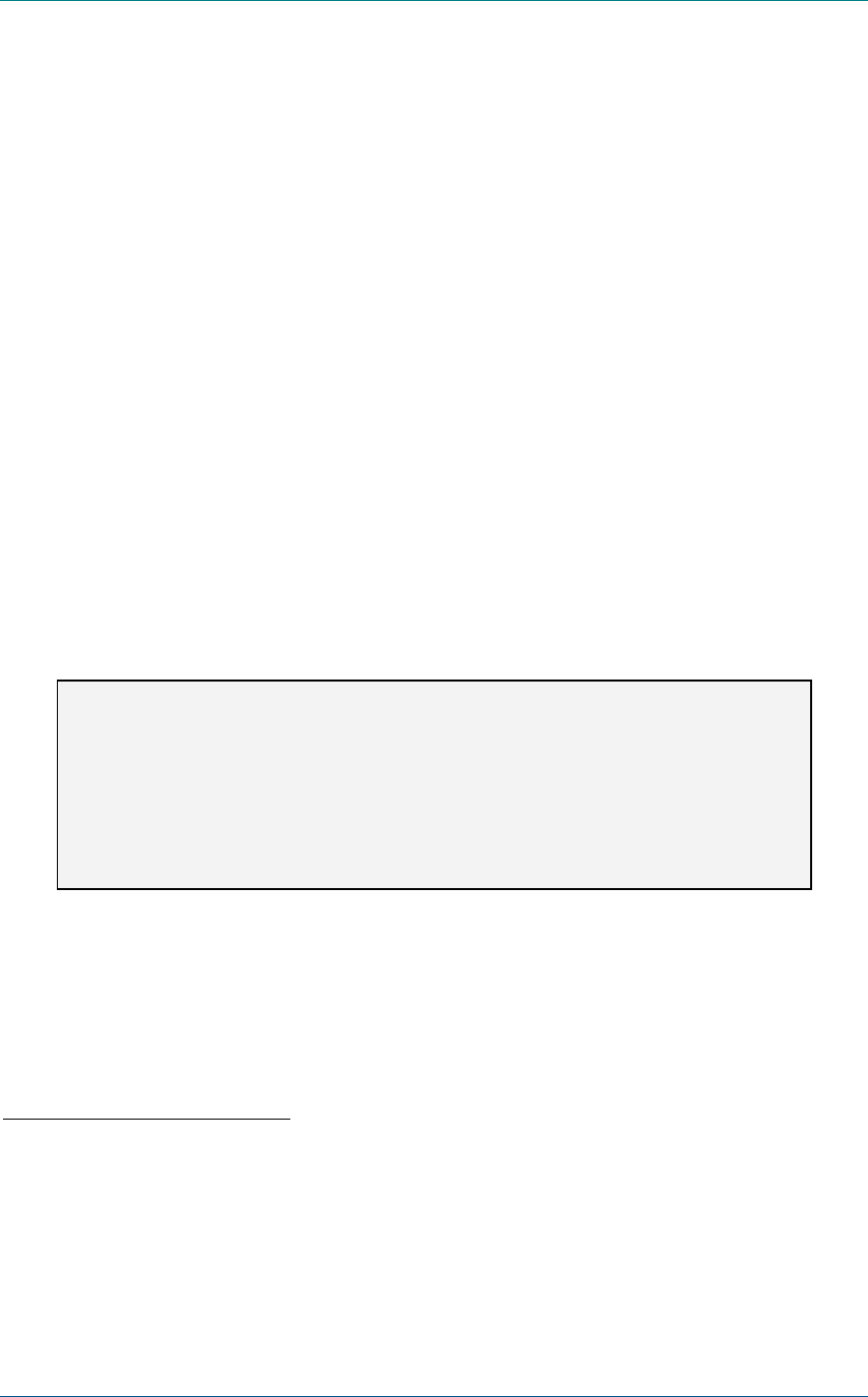

Although the total volume of claims established has increased over time, the majority of claims

established have been the result of recipient errors, with agency errors being second most

common, and recipient fraud claims being least common—as illustrated by Figure 2.

Figure 2. Claims Establishment by Type, FY2007-FY2016

Source: Created by CRS using data from SNAP State Activity Reports FY2007-FY2016.

Detection and Correction of Errors and Fraud

State and federal efforts to detect and correct errors, as well as efforts to detect and deter fraud,

are detailed in this section.

58

The claim threshold for agency errors in California is $35 for current households and $125 for inactive households.

See http://www.cdss.ca.gov/shd/res/htm/FoodStampIndex.htm.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 14

Retailer Fraud

USDA-FNS is responsible for administering the retailer side of SNAP and for pursuing retailer

fraud.

59

USDA-OIG, in collaboration with the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), U.S. Secret

Service, and other federal, state, and local law enforcement entities, is responsible for pursuing

criminal charges against retailers found to be engaging in retailer trafficking.

Detection of Retailer Trafficking

Retailer trafficking can be detected through a variety of means, including the following:

Analysis of EBT Transaction Data—Whenever a SNAP EBT card is swiped, the transaction

data is captured and analyzed by USDA-FNS for suspicious patterns. USDA-FNS use these data

to develop a case against a retailer when the transactions indicate retailer trafficking is occurring

at their store. In FY2016, USDA-FNS reviewed the transactions of nearly 9% of participating

stores.

60

Over 80% of retailer trafficking detected by USDA-FNS are found primarily through

EBT transaction analysis.

61

Undercover Investigations—USDA-FNS performs undercover investigation of stores suspected

of violating SNAP rules (e.g., trafficking), and in FY2016, USDA-FNS investigated over 1% of

participating stores.

62

State Law Enforcement Bureau (SLEB) Agreements—Some state agencies enter into state law

enforcement bureau (SLEB) agreements with law enforcement entities in their jurisdictions in

order to further their efforts to detect trafficking. These agreements are typically focused on

recipient trafficking, but they can have implications for retailer trafficking.

Tips and Referrals—USDA-FNS receives tips, complaints, and referrals, which can lead to

cases of retailer trafficking. These referrals come from SNAP retailers, SNAP recipients,

members of the public, state agencies, SLEBs, USDA-OIG, or other law enforcement entities.

USDA-OIG operates a website and hotline for members of the public to report instances of

fraud.

63

In FY2016, USDA-OIG referred 4,320 complaints to USDA-FNS.

64

59

Sections 9, 12, and 15 of the FNA outline the requirement that USDA-FNS administer SNAP on the retailer side.

60

This CRS calculation is based on data from the December 2016 USDA-FNS Retailer Management Report, p. 1.

61

This CRS calculation is based on data from the December 2016 USDA-FNS Retailer Management Report, p. 8 and

an email from SNAP, USDA-FNS, October 25, 2017. In FY2016 1,842 stores were permanently disqualified for

trafficking SNAP benefits, and USDA-FNS undercover investigations identified retailer trafficking in 288 instances.

The remaining stores were EBT cases, sometimes referred to as paper cases.

62

About 20% of these investigations resulted in findings of trafficking. This CRS calculation is based on data from the

December 2016 USDA-FNS Retailer Management Report, p. 8.

63

USDA-OIG hotline information available at https://www.usda.gov/oig/hotline.php.

64

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Inspector General, Semiannual Report to Congress: Second Half, April

1, 2016-September 30, 2016, Number 76, November 2016, p. 54, https://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/

sarc2016_2nd_half_508.pdf (hereinafter cited as “USDA-OIG SARC 2

nd

Half FY2016”); U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Office of the Inspector General, Semiannual Report to Congress: First Half, October 1, 2015-March 31,

2016, Number 75, May 2016, p. 57, https://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/sarc2016_1st_half.pdf (hereinafter cited as

“USDA-OIG SARC 1

st

Half FY2016”).

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 15

Correction of Retailer Trafficking

If a store is found to have committed trafficking, then all of the owners of the store may be

subject to penalties.

65

Major penalties associated with retailer trafficking include the following:

Disqualification—If USDA-FNS finds that a SNAP-authorized retailer violated any SNAP rules,

then that retailer may be subject to a period of disqualification from program participation.

66

Trafficking SNAP benefits is considered one of the most severe violations of SNAP rules, and a

retailer found by USDA-FNS to have trafficked SNAP benefits (regardless of the amount) is

generally subject to a permanent disqualification (PDQ) from program participation.

67

Reciprocal WIC Disqualification—Stores that are disqualified for violations of the rules of

SNAP are disqualified for an equal (but not necessarily concurrent) period of time from

participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

(WIC).

68

Likewise, stores disqualified from WIC are disqualified from SNAP for an equal (but

not necessarily concurrent) period of time. PDQs, such as PDQs for trafficking, are also

reciprocal between the programs.

Restitution of Benefits Trafficked

(Claims)—When a retailer accepts or

redeems SNAP benefits in violation of

the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008

(FNA), such as engaging in retailer

trafficking of SNAP benefits, that retailer

may be compelled to repay the amount

that they illegally redeemed. This is

called a claim and is considered a federal

debt. USDA-FNS has the authority to

collect such claims by offsetting against a

store’s SNAP redemptions as well as a

store’s bond or letter of credit (LOC),

69

where applicable.

70

Public Disclosure of Disqualified Retailers—USDA-FNS has the authority to publicly disclose

the store and owner name for disqualified retailers.

71

A December 2016 USDA-FNS Final Rule

asserted USDA-FNS’s intent to disclose this information in order to deter retailer trafficking.

72

65

In community property states, the spouses of owners are automatically considered owners themselves and are also

subject to all applicable penalties. As of March 2018, Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico,

Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin are community property states.

66

Disqualifications can be for a term or permanent. Term disqualification can vary in length from 6 months to 10 years,

depending on the nature of the violation. Disqualification for trafficking is generally permanent. Section 12 of the FNA

(codified at 7 U.S.C. §2021 and implemented at 7 C.F.R. §278.6).

67

Section 12(b)(3)(B) of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2021(b)(3)(B) and implemented at 7 C.F.R. §278.6(e)(1)(i)).

68

Section 12(g) of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2021(g) and implemented at 7 C.F.R §278.6(e)(8)). For more

information on WIC, see CRS Report R44115, A Primer on WIC: The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for

Women, Infants, and Children, by Randy Alison Aussenberg.

69

In certain circumstances USDA-FNS may require a retailer to provide a form of financial collateral (i.e., a collateral

bond or an irrevocable letter of credit) as a condition of SNAP authorization.

70

Section 15(e) of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2024(e) and clarified at 7 C.F.R. §278.7).

71

Section 9(c) of the FNA (codified at 7 U.S.C. §2018(c) and implemented at 7 C.F.R. §278.1(q)(5).

72

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Enhancing Retailer Standards in the Supplemental

Rights of Retailers Accused of Fraud

Following a completed trafficking investigation, the agency

sends a retailer a “charge letter” detailing the charges, and

explaining the retailer’s right to request administrative

review. If requested, an independent subdivision of USDA-

FNS considers the validity of the charges anew and issues a

Final Agency Determination that sustains, reverses, or

modifies the charges and explains the retailer’s right to

request judicial review. The retailer may choose to file a

complaint against USDA-FNS in the court of jurisdiction after

receiving a Final Agency Determination.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Congressional Research Service R45147 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED 16

Transfer of Ownership Civil Money Penalty (TOCMP)—If a retailer under a period of

disqualification sells or transfers ownership of their store, then USDA-FNS is to assess that

disqualified retailer a “transfer of ownership civil money penalty” (TOCMP).

73

This means that

retailers permanently disqualified from SNAP for committing retailer trafficking are to be

assessed this penalty whenever they sell or transfer ownership of their stores (regardless of how

much time has passed since the disqualification occurred). In FY2016, USDA-FNS assessed 257

such penalties with a mean value of $29,284.

74

Exclusion from the General Service Administration’s System for Award Management

(GSA-SAM)—This GSA system tracks individuals and entities that do business with the federal

government. An individual or entity excluded from this system is prohibited from doing business

with the federal government for the duration of the exclusion.

75

All of the owners of a store

permanently disqualified from SNAP participation for trafficking benefits are permanently listed

as exclusions in GSA-SAM. As of September 2017, 10,307 permanently disqualified retailers

have been listed by USDA-FNS in GSA-SAM as exclusions due to SNAP and WIC violations.

76

This type of exclusion can have collateral consequences for the excluded party.

77

Criminal Charges and Penalties—Retailers engaged in trafficking may be criminally charged

and penalized with fines up to $250,000 and imprisonment up to 20 years.

78

In addition, other

adverse monetary penalties (e.g., asset forfeitures, recoveries, collections, and restitutions) may

be assessed against those convicted. USDA-OIG, in collaboration with federal, state, and local

law enforcement entities, pursues charges against retailers who traffic SNAP benefits. USDA-

OIG usually criminally pursues only retailers who traffic in high dollar amounts of benefits

and/or retailers who also engaged in other criminal activity. In some cases, state law enforcement