Running head: COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 1

Color Psychology and Graphic Design Applications

Rose Rider

A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for graduation

in the Honors Program

Liberty University

Spring 2009

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 2

Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis

This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the

Honors Program of Liberty University.

______________________________

Todd Smith, M.F.A.

Thesis Chair

______________________________

Edward Edman, M.A.

Committee Member

______________________________

Edward Martin, Ph.D.

Committee Member

______________________________

Marilyn Gadomski, Ph.D.

Assistant Honors Director

______________________________

Date

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 3

Abstract

Color filters humanity’s perception of the world and alters people’s relationships with

their surroundings. It influences human perception, preference, and psychology

throughout the lifespan. Color preferences appear in infants as young as three months old,

and typically change with age. Some responses to color may be innate, and some may be

learned from nature or culture. Cool hues are relaxants, and are generally preferred over

their more arousing warm counterparts. Color is a subtle but pervasively influential

element in graphic design. It permeates graphic representations in packaging, advertising,

and branding. Slight variations in color can advance or devastate design effectiveness and

have massive economic implications for companies and products. Whether audiences are

conscious or unconscious of color’s impact, its hypnotic potential makes it a worthy asset

for any visual communicator. A study assessed the point, if any, at which the joint effects

of brightness and saturation cause a viewer to prefer a yellow color to a blue color.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 4

Color Psychology and Graphic Design Applications

Color as a Filter

Color is a powerful medium through which man views the world. Unlike most

animals, which see only shades of gray, humans are exposed to this marvelous additional

dimension of vision (Bleicher, 2005). Color influences human perception, preference, and

psychology. The subtle but powerful influence of color is an inviting study for

psychologists. When applied skillfully and intentionally, color is a valuable

communication tool for graphic designers.

Color Perception

What humans perceive as color is actually lightwaves reflected off a surface

(Bleicher, 2005). Surfaces absorb all the spectral hues except for those that bounce off in

the form of visible color. A specific color is composed of three elements: hue (the

common name of a color, e.g., red or blue), value (brightness), and saturation (vividness

or lack of gray; Valdez & Mehrabian, 1994). Faber Birren (1997) described the natural

shape of color as a triangle, with white, black, and any given pure hue making up the

three corners, and a gradient of tints and shades in the middle.

The human retina contains rods and cones, specialized cells that perceive different

aspects of vision (Bleicher, 2005). Rods are long and cylindrical, able to perceive only

value. Cones are wider, conical receptors that perceive color. Humans have 100 million

rods but only 6 million cones in each eye, thus making value easier to perceive than

color. This is why vision in low light appears almost colorless.

There are also cases of responses to color not perceived by the eye. Light and

color therapy have been used to treat jaundice, skin conditions, and sleep disturbances

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 5

successfully. One researcher found that blind subjects reacted to colored rooms just as

seeing subjects did. Theories have also been constructed to explain the phenomenon of

dermo-optic vision, the ability of some humans to feel color. One such theory suggests

that humans have receptors in the skin that sense color wavelengths (Bleicher).

Difficulties in Color Psychology

Color psychology is a young field that is largely unexplored. In a field striving for

establishment, there are two chief difficulties for serious students of color psychology.

First, the student must differentiate between science and the occult. Faber Birren, a well-

known pioneer of color psychology, was heralded for “daring” to learn from occultists

and mystics (Morrow, as cited in Birren, 1997, p. ix). Angela Wright (1998) mentioned

the mystic aura said to surround human beings in one paragraph, and Newton’s theory of

color in the next.

Second, the student of color psychology must take care to recognize valid

scientific conclusions reached through appropriate methodological means. One must also

be wary of vaguely worded results because of the difficulty in measuring emotional

responses to color stimuli objectively and quantitatively (Valdez & Mehrabian, 1994).

The impartiality of researchers, number of subjects analyzed, standardization of colors,

and regulation of variables are key to valid research. Anything else may be more

speculative than factual. McManus, Jones, & Cottrell (1981) called results obtained under

substandard conditions or with faulty methodology “generally worthless” (p. 651).

Many early experimenters studied only hues, which they frequently identified by

name only (Valdez & Mehrabian, 1994). In recent years, color psychologists have taken

greater care also to specify and test the brightness and saturation of precise colors rather

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 6

than broad hues. Most now use colors from standardized systems such as the Munsell

Color System. They also use carefully monitored lighting designed to approximate

daylight. All variables other than the one being tested should be regulated to provide a

consistent testing environment capable of yielding accurate results (Valdez &

Mehrabian).

Color Psychology

Color Preference

Researchers have conducted color preference studies in many age groups and

have found significant results. Infants as young as three months old consistently stared at

some colors longer than others (Crozier, 1999). They stared longest at red, then yellow,

blue, and green. Color preferences appear to shift with age, however. Five-year-olds also

preferred red, but ranked other colors as follows: blue, purple, orange, yellow, and green.

Further shifts in color preference occur with maturity and adulthood. Most significantly,

adults begin to prefer green and blue, while beginning to dislike yellow (Crozier).

Color preference studies have found slight variations in adult hue preference, but

this classic hierarchy that Eysenck (1941) established has been generally correct for sixty

years: blue, red, green, violet, orange, and yellow. It was found to be true across both

genders and ethnic groups. Faber Birren (1997) declared it the “eternal and international

ranking” (p. 176).

This does not imply, however, that traits such as gender and ethnicity have no

bearing on response to color stimuli. Extroverts generally prefer brighter colors, whereas

introverts prefer lighter, more subdued tones (Crozier, 1999). Some cultures prefer red

and/or green to blue (Birren, 1997). Valdez and Mehrabian (1994) discovered that

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 7

although the genders responded very similarly to variations in saturation and value,

women were more sensitive to the variations than men were. Khouw (2002, as cited in

Singh, 2006) found the genders differed in perception of grayscale tones and color

combinations. Women also became more confused and distracted than their male

counterparts.

Color preference research commonly has studied only hues; but the other two

dimensions of color, brightness and saturation, play a large role in the overall appearance

and emotional effects of any given color. Valdez and Mehrabian’s (1994) study

simplified much of the color psychology field by testing the effects of hue, saturation,

and value on emotional response. They discovered relatively simple patterns in which

brightness and saturation had substantially greater effects on emotions than hue. It is

because of such research that the findings of early experiments that studied and specified

only hues must be read with discernment.

Color Response

Nature and nurture. One of the chief questions to arise in color psychology is

the question of behavioral origins. Studies seek to determine if responses to color stimuli

are innate, learned, or some combination of the two. Although research with infants

indicates that innate reactions do exist, variation in color response across demographics

suggests that much of adult color response is learned (Crozier, 1999).

Innate response. As mentioned in the previous section, Choungourian (as cited in

Crozier, 1999) found that three-month-old babies stared longer at long-wavelength colors

such as red and yellow. Many animals with color perception also show innate

preferences, but, ironically, for short-wavelength colors such as blue and green. One-day-

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 8

old northern bobwhites were most inclined to peck pinheads colored blue, then green,

yellow, and finally red (Mastrota & Mench, 1995). This was almost exactly the opposite

of human babies’ rankings of color preference. Moths, bumblebees, and robins also

showed preferences for blue (Crozier). Gorillas and chimpanzees greatly preferred blue

and green to red (Wells, McDonald, & Ringland, 2008). If these animal responses are

innate, humans differ drastically from animals in innate color response.

Learned response. Although some mature human responses to color stimuli may

be innate, many others appear to be learned. These learned responses may result from

either natural or cultural color conditioning (Crozier, 1999).

Natural color conditioning occurs when a positively or negatively perceived

natural element casts its own positive or negative connotation on a related color. It can

operate universally and cross-culturally. For example, Hemphill (1996) speculated that

the world’s favorite color, blue, may owe its popularity to the ocean and sky on sunny

days. If the preference for blue is learned from nature, Hemphill’s theory offers a credible

explanation for why infants and children do not like blue as much as adults do. Consistent

with this theory, Hemphill also found negative responses to gray, which subjects

associated with rainy, overcast days.

Cultural color conditioning plays a significant role in shaping responses to color

stimuli. Different cultures vary in their use of color, affecting individual responses. For

example, the Ndembo of Zambia do not recognize orange as a color, whereas the Hindus

consider it sacred (Singh, 2006).

Traditional and religious symbolism play major roles in culturally-conditioned

color preference (Fehrman & Fehrman, 2004). Early Asian movements such as

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 9

Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism promoted yellow and orange (Birren, 1997;

Singh, 2006). Muslims and Celts shared green as their sacred color (Singh). Christianity,

while not embracing colors as sacred, contributed strong salvation-related meanings to

red, white, and black. Other color associations, such as white in weddings, red ink used to

mark mistakes, and figures of speech such as green with envy influence color evaluation.

Since so much response to color is learned, it is challenging but important for researchers

to differentiate between learned and innate responses (Fehrman & Fehrman).

Responses to hues of different wavelengths.

Hue classes. Colors are paradoxes. They affect emotions, behaviors, preferences,

performance, and physiology in many different, and sometimes contradictory, ways. Two

classes of hues exist, arranged according to wavelength. Each class is distinct, generally

exerting influences opposite to those of the other class.

Warm hues. Although it is difficult to assess the psychological effects of color

objectively, most researchers are in general agreement that long-wavelength colors

(warm hues such as yellow and red) are more arousing than short-wavelength colors

(cool hues such as blue and green; Valdez & Mehrabian, 1994). Warm colors raise the

heart rate and increase hunger (Berman, 2007). This makes them popular choices for fast-

food restaurants. They are also eye-catching and appear as warning signs on fire trucks,

brake lights, stinging insects, stoplights, traffic cones, hazardous substances, and inmate

uniforms.

Red is perhaps the most studied, yet most disputed color. Researchers agree that it

is powerful and generally liked, but it is difficult to study conclusively. A study

conducted by Cimbalo, Beck, and Sendziak (1978) ranked red with black and brown as

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 10

sad colors, but Hemphill (1996) found subjects associated it with happiness. It has

implications of passion and romance in relational contexts. Red is a popular choice for

sports teams. Hill & Barton (2005) found that when all other factors are equal, wearing

red can propel an athletic team to victory.

Despite its energizing qualities, red also has an intimidation factor. It makes

objects seem heavier and time pass slowly (Birren, 1997). Fashion experts warn against

wearing red for job interviews, as it may intimidate prospective employers (Berman,

2007). Elliot and Maier (2007) found the presence of red anagram tests significantly

impaired performance. However, Mehta and Zhu (2009) found that a solid red computer

wallpaper improved performance on detail-oriented computer tasks, likely through

avoidance motivation because of red’s association with danger and mistakes.

Yellow and orange share many of the same properties. Color theorists agree that

yellow is a happy hue (Cimbalo et al., 1978; Hemphill, 1996). It has pleasant

connotations of sun, brightness, and warmth (Cimbalo et al.). Ironically, it is also the

least-preferred hue. Like red, it raises the pulse, but not to the same extent. In soft,

creamy tones, yellow is soothing (Berman, 2007). It often appears brighter than white to

the human eye (Birren, 1997), and is a popular color for attracting attention in everything

from packaging (Berman) to road signs. Orange is another happy but unpopular warm

hue (Cimbalo et al.). It also draws attention and stimulates the appetite (Berman). As the

hybrid of yellow and red, its bright yet powerful properties have made it a popular color

for marketing cleaning products.

Cool hues. Cool hues, on the other hand, are recognized as more relaxing, and are

collectively much better liked (Crozier, 1999). Blue is a foil to red in almost every way,

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 11

lowering blood pressure (Birren, 1997), stimulating creativity (Mehta & Zhu, 2009), and

stifling hunger (Bleicher, 2005). Blue is a popular choice for traditional restaurants

because it relaxes customers and encourages them to linger, making them more likely to

add to their orders. Contrary to red, blue makes objects seem lighter and time pass more

quickly (Birren). Like red, its happiness properties are disputed. In a study conducted by

Cimbalo et al. (1978), children labeled it happy, but college students called it sad. It is a

pervasively popular wardrobe choice, as the major color in half of all clothing

combinations (Hemphill, 1996).

Green’s psychological effects vary widely with its different tones. A happy color

(Cimbalo et al., 1978), it is primarily associated with nature, trees, and vegetation

(Hemphill, 1996), which often gives it a relaxing quality. Dark green connotes wealth and

status (Berman, 2007), but pea green is associated with nausea (Fehrman & Fehrman,

2004). Green also has creepy associations with death, poison, and supernatural or

extraterrestrial phenomena. Birren (1997) described it as a psychologically neutral color,

representing a withdrawal from stimulus.

Importance of context. Color preferences and responses, however, are entirely

subject to context (Elliot & Maier, 2007). Although blue is consistently preferred and

yellow consistently disliked (Crozier, 1999), most people would prefer yellow in the

context of a lemon or a wedding band. This concept of what Taft (1997, as cited in

Crozier, 1999) called “colour-object appropriateness” (p. 48) has significant bearings on

responses to color in different contexts.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 12

Application of Color in Graphic Design

Color Conversations

“…[T]he real value of color is intellectual, not decorative,” Jan White wrote

(1991, as cited in Nelson, 1994, p. 215). “It must not be used to dazzle, but to enlighten”

(White, as cited in Nelson). There is a sort of dignity employed in proper color

application. Color should function as more than a basic tool for blunt impact. Good

design incorporates color in all its subtleties—shade, tint, hue, and chroma. Designers

should use color to relate with their audiences, rather than as a tool for psychological

manipulation. Color may shout, but it must also speak to its viewers in witty, intelligent,

and conversational ways. In the competitive fields of packaging, advertising, and

branding, color’s dialogues are matchless.

Audience Targeting

Personalizing through color. Color is a wonderful, seemingly effortless way to

converse with specific audiences. With careful attention given to gender, age, culture,

social status, personality, and color trends, the designer is able to reach his audience more

effectively through color. Color signals personalization (Lambert, 2004). Any intimacy a

designer can achieve with his audience through color is a valuable asset.

Gender. Gender’s influence on color choices is reportedly diminishing (Paul,

2002). Both sexes prefer the same house and car colors (white and beige; and blue, silver,

and black, respectively). Thanks to a more flexible gender role, women are free to be

more accepting of the entire color spectrum. Social restraints still discourage men from

liking pinks and purples, but more men are wearing these colors than ever before.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 13

Eiseman (as cited in Paul, 2002) attributed this to loosening gender roles and a wide

variety of colors in athletic uniforms.

Age. A general rule of thumb in designing for different age demographics is to

use lighter colors when designing for older audiences. As people age, colors begin to look

darker, making lighter colors more appealing.

Today’s children have been exposed to broad palettes since they received their

first big boxes of Crayola crayons. They are very open to novelty and experimentation

with colors. Color effects such as glitter, translucence, pearlescence, and metallics appeal

to younger audiences (Paul). Secondary colors are also heralded as young (Dettmer,

2003).

Hues are an important consideration, but shades also factor into preference

differences across age demographics. In a study conducted to see which age groups liked

various shades of blue, participants ages 13-20 and especially 21-34 preferred navy

blue/midnight (Paul, 2002). In contrast, audiences 35 and older preferred sky blue and

French/smoky blue (Paul).

Culture, ethnicity, and nationality. A study of international color connotations

revealed that there are virtually no universals. Peterson and Cullen (2000) catalogued

cultures and colors and found tremendous diversity worldwide. For example, green can

hold vastly different connotations for desert and rainforest dwellers; white, for tropical

and polar residents. Natural color occurrences, coupled with local preferences and

centuries of history, produce complex color meanings and associations across the globe.

Learning the color vernacular of the target audience is important, but Peterson and

Cullen (2000) warned against mere mimicry. Cultures worldwide love the exotic.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 14

However, designers should thoroughly research their palette choices to avoid offensive or

confusing colors or combinations.

In the United States, there are slight color preference variations among ethnic

groups. Asians, blacks, Hispanics, and whites all prefer blue (Paul, 2002). Purple is

slightly more popular among blacks and Hispanics, whereas Asians prefer pink and

whites lean towards green. One staggering statistic is blacks’ typical dislike for pink.

Forty percent of blacks listed pink as their least favorite color, compared to 23% of

whites and 17% of Asians and Hispanics (Paul).

Social status. Blue-collar audiences prefer primary colors, while more upscale

audiences prefer softer pastels (Nelson, 1994). Silver, gold (Nelson), and red (“Cheskin

Research,” 1998) convey a sense of quality that appeals to more sophisticated audiences.

Black is also a very formal, chic, serious color used for reaching white-collar

demographics (Peterson & Cullen, 2000).

Personality. Personality affects not only response to different colors, but color

sensitivity in general (Nelson, 1994). Extroverts are highly responsive to color, whereas

introverts are actually more sensitive to shape. Color is more persuasive with its audience

than shape is, however, as extroverts are more responsive to color than introverts are to

shape. Extroverts also prefer brighter colors, whereas introverts prefer lighter, more

subdued tones (Crozier, 1999).

Color trends. Choosing colors is an important decision in any area of design.

Selecting a color that will appear for years to come has far-reaching consequences and

may either bolster or damage sales in the future (Lambert, 2004). Such a choice cannot be

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 15

made on a whim. It must be formulated with a careful understanding of current and future

color trends.

A final consideration in effective audience targeting is targeting tomorrow’s

audience. Faber Birren theorized that popular colors are in for about three years

(Toufexis, 1983). Preferred colors rise and fall in accordance with current events, pop

culture, influential designers, and social movements (Nelson, 1994).

The King Tutankhamen traveling exhibit of 1978 left golds, browns, and autumn

colors in its wake (Nelson, 1994). One writer attributed the widespread soft pastels of the

mid-1980s to the influence of architect Michael Graves (Nelson). Turquoise spiked in

popularity among Italians in October 2009 when supporters of Judge Raimondo Mesiano

adopted the judge’s fashion taste and donned turquoise socks (“Turquoise,” October 26,

2009). Social causes also affect color trends, often employing colored ribbons as cause

symbols. Yellow is now synonymous with military support; pink, with breast cancer

research; red, with HIV/AIDS activism; green, with eco-friendly living.

Color trends can also be embarrassed responses to earlier fads. Sometimes the

color pendulum swings out of repulsion rather than attraction. According to Alva (2006),

this decade’s use of a wide color palette is a reaction against the dominant blues of the

1990s.

Color Use in Graphic Design

Color schemes. After audience research, designers must focus on the

organization, corporation, product, or service to represent to the target audience. Before

designers can select individual colors, they must assess color schemes and printing

budgets (Williams, 2001).

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 16

Strong color schemes are important to effective design. Monochromatic designs,

containing various shades and tints of one hue, are most effective for communicating

simple messages (Fehrman & Fehrman, 2004). Multiple-color combinations can add

depth, complexity, and additional meaning to design. A common two-hue combination

involves complimentary colors, colors directly opposite each other on the color wheel

(e.g., blue and orange, or red and green; Berman, 2007). Three-hue color harmonies often

involve triads, colors located equally far from each other on the color wheel (Bleicher,

2005).

Adding a second color allows the designer to fake a full-color print. Nelson

(1994) recommended adding greens and blues while avoiding yellow. In the direct mail

arena, red has been a longtime leader for the most effective second color.

Four-color schemes in general are more attractive than one- or two-color schemes

(Shank & LaGarce, 1990). One-color schemes, however, were ranked more tasteful than

their two- or four-color counterparts. A simple monochromatic color scheme can lend an

air of sophisticated restraint while cutting costs (Nelson, 1994).

A phenomenon known as vibrating colors occurs when bright colors of equal

intensity are placed beside each other (Berman 2007). This can make text difficult to

read. Color vibration is most often a design faux pas except for rare occasions when the

vibration is an intentional part of the design.

The graphic designer must consider value and saturation as well as hue. Gorn,

Chattopadhyay, Yi, and Dahl (1997) found that greater value in a magazine ad increased

viewer relaxation, and greater saturation increased excitement. Gorn et al. suggested that

these two positive emotions are not mutually exclusive and may in fact be a desirable

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 17

combination in design that appeals to both emotions (such as tourism advertising).

Carefully selected color schemes should appeal to viewers’ emotions based on the

content of the design piece.

Advertising. In the words of the Color Marketing Group, “Colour sells… and the

right colours sell better” (as cited in Lambert, 2004, p. 77). Color is king in advertising. It

attracts viewers (Shank & LaGarce, 1990), holds their attention (Berman, 2007), and aids

their memory (Shank & LaGarce). Consumers remember colors first, then graphics,

numbers, and finally words (Wallace, 2002).

Full-page color ads are noticed twice as much as their black and white

counterparts (Nelson, 1994). Although full-color ads cost a third more than black and

white ads, they are up to fifteen times as effective in measured results. As an ad for the

Eastman Kodak Company testifies, “Black-and-white is for budgets. Color is for results”

(as cited in Nelson, p. 212). Color advertising pays for itself.

Gorn, Chattopadhyay, Yi, and Dahl (1997) suggested that colors in advertising

should be selected on two levels: the “basic, universal level” (p. 1398), which includes

technical aspects such as brightness and saturation, which are assumed to be perceived

universally, as are their physiological means of perception; and the “culture specific

level” (p. 1398), which takes into consideration cultural norms and color connotations.

Packaging. Packaging plays two vital roles. The first is to catch the customer’s

eye as he scans supermarket shelves. According to Eiseman (2006, as cited in Alva,

2006), “a product unseen is unsold” (p. A07). Packaging’s second function is to

communicate wordlessly about the product and establish its placement among

competitors, a role known as positioning (Nelson, 1994). Both of these roles are

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 18

dependent on color choice, which can dramatically improve or decrease the product’s

sales if its eye-catching qualities or positioning is substandard.

Nelson (1994) listed color as packaging design’s “single most important factor”

(p. 353). When consumers scan store shelves, their eyes pass over each product in three-

hundredths of a second (Fehrman & Fehrman, 2004). Furthermore, they scan store aisles

for colors, not for design or text (Nelson). 62-90% of a customer’s assessment of a

product comes from the colors alone (Singh, 2006). Sturgess (2008) wrote, “Color sets

the tone before you can even begin to load the mental software required to read a

product’s label” (p. 15).

Packaging color defines and destines products. According to Davis Masten,

Principle at Cheskin Research, “Even a slight shift in the tint or saturation of a particular

color can impact a product’s sales and success” (“Cheskin Research,” 1998, p. 6494).

In packaging, some colors or color combinations carry different connotations than

they would have in other contexts. On a package, white is far from a passive ingredient.

When white appears on soft drink cans, it implies that the drink is low in calories

(Nelson, 1994). Bright letters on fields of white convey impressions of strength and

purity. The weight loss drug Alli utilizes a white field across which it splashes red, blue,

yellow, and green letters that testify to its slimming powers (Sturgess, 2008).

John Steel of Colgate-Palmolive Co. calls yellow “intimidating in packages” (as

cited in Somasundaram, 1995, p. A9). Red, on the other hand, is “warm and bright”

(Steel, as cited in Somasundaram, p. A9). Red sells for two reasons: (1) It conveys a

sense of quality, and (2) it is “an impulsive color and makes you want to buy” (“Cheskin

Research,” 1998, p. 6494).

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 19

Branding.

Colors as allies. Every year in the days before Valentine’s Day, Saudi Arabia

bans red from gift shops and florist shops (“Saudi Arabia,” 2008). Saudi officials

criticized the romantic red holiday, labeling it “a non-Muslim celebration… that

encourages immoral relations between unmarried men and women” (“Saudi Arabia”).

Colors are entities of vast power. If a color and its connotations are enough to

threaten a nation’s solidarity, colors may also function as tremendous allies to strengthen

and support. For example, the 20% increase in heart rate that Western women experience

at the sight of robin-egg blue has been attributed to Tiffany’s and its little blue box

(Sturgess, 2008). This is why color is a weighty factor in branding logos and palettes.

Logos. Color choice is nowhere more crucial than in logo design, where slight

variations in hue can have enormous economic impact. Color defines a logo’s appearance

and personality (Gernsheimer, 2008). In turn, the logo defines the company and promises

that its own qualities are representative of the company’s (Tyler, 1992). Color choice can

also make a logo memorable or forgettable. Huang, Lin, and Chiang (2008) found that

using a preferred color with an unfamiliar logo significantly increased logo recall.

In survival mode, a low-quality grayscale reproduction such as in a want ad, a

logo must be able to function independently of color or even value. Gernsheimer (2008)

recommends that designers create their logos in black and white to test their grayscale

effectiveness before exploring color possibilities.

For a logo to reach its maximum potential, a signature color is a virtual

requirement (Gernsheimer, 2008). Additional colors are often distracting and can harm

branding consistency. However, neutral colors (e.g., white, black, gray, and silver) can

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 20

function well in the logo as contrasts to the signature color. They can also be added to the

primary color palette.

Restraint is invaluable in color selection. Too many colors can dilute a logo’s

iconic impact. Multiple-color logos (such as NBC’s or Google’s) must have carefully

selected color palettes. The colors should function well both independently and

collectively. Gernsheimer advises selecting “second-tier” colors that can complement the

primary color(s) and supplement the color palette (pp. 44-46).

Successful, established logos can rely on design and color alone, rather than text,

in their representations (Bleicher, 2005). Some companies can even be represented only

by their colors, such as UPS with brown and Coca-Cola with red.

Brand colors. In branding, there is no greater trademark than owning a color

(Alva, 2006). Eiseman (2006, as cited in Alva) called color the “silent salesperson” (p.

A07). The Supreme Court ruled in 1995 that colors alone could serve as legally

defensible trademarks (Fehrman & Fehrman, 2004).

Branding colors make enormous suggestions about the organizations or

corporations they represent. Brown promises that UPS is steady and reliable (Alva,

2006). Purple hints that Nexium is sensual and spiritual (Applebaum, 2005). Orange says

that Tide is cleansing and energetic (Berman, 2007).

Branding designers should consider competitors’ palettes (Nelson, 1994). Brand

confusion is an important factor that can either help or harm. Often competitors within a

given market choose colors that will differentiate them. For example, in the cell phone

arena, AT&T owns blue, Verizon owns red, T-Mobile owns pink, Sprint owns yellow,

and Cingular Wireless owned orange (Alva, 2006).

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 21

The current branding trend is moving away from blues (Alva, 2006). Although

red is passionate and yellow is eye-catching (Alva), secondary colors are enjoying

popularity (Dettmer, 2003). They are nontraditional and more youthful. Orange has

largely replaced blue in this decade. Dettmer calls orange the new “color du jour,” citing

its “connotations of hope, fun and freedom” (p. 55).

Eiseman (2006, as cited in Alva, 2006) condemns taking advantage of brand

confusion. However, Forest (1983, as cited in Nelson, 1994) points out that new brands

can actually enjoy free rides on the backs of established competitors by using similar

colors. The off-brand cereal manufacturer Malt-O-Meal has reinforced the legitimacy of

over a dozen of its cereals by imitating the color palettes of well-known General Mills,

Kellogg’s, Post, and Quaker cereals. For brand independence, however, it is best to

introduce a new color into a given arena.

Color palettes. Color palettes must work in close harmony with the logo and the

signature color (Gernsheimer, 2008). Each color in the palette must also function well

alongside other palette colors.

Colors can lend a hierarchical element to branding design (Gernsheimer, 2008).

They often function in pairs, with a mid-value color defining the logo and a darker shade

used for accents or coloring the tagline.

The medium in which the palette colors will most commonly appear determines

color parameters and possibilities (Gernsheimer, 2008). Color is free onscreen, whereas

printed color is much more expensive. Logos and palettes that appear most commonly

onscreen make for easy and inexpensive full-color reproduction. For logos and palettes

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 22

appearing primarily in print, however, selecting a minimal color palette may save

significantly on printing costs over years of branding.

Conclusion

At its best, color converses. Designers can use color most effectively once they

have studied the color languages of their target audiences, as well as the messages to

convey. The best designs are visual languages in which colors have active voices and

appeal to their audiences on both emotional and intellectual levels. Whether the audience

is conscious or unconscious of this conversation, color’s hypnotic potential makes it a

worthy asset for any visual communicator.

Color application in graphic design is a discipline that builds directly upon the

fundamentals of color psychology. Color choices based on a whim or the designer’s own

preference are generally not as effective as choices that give careful consideration to

message, audience, and context. Understanding the basics dimensions of color and their

influence upon human viewers is invaluable. Towards this end, the researcher conducted

a study on color preference as affected by two basic properties of color: brightness and

saturation.

In color psychology and graphic design, the three-dimensionality of color is often

disregarded, with an overemphasis on hue. Most early studies failed to specify color

stimuli properly or were unable to measure emotional results scientifically (Valdez &

Mehrabian, 1994). Many overlooked the variables of brightness and saturation and

referred only to hues, while others did not present their subjects with color samples but

asked them to rank hue names (such as red, blue, or green; Valdez & Mehrabian).

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 23

Eysenck’s color ranking (1941) failed to account for saturation and brightness,

but its basic findings have been upheld by more methodologically sound studies such as

Guilford and Smith’s (1959, as cited in Valdez & Mehrabian, 1994). Both studies ranked

hues as follows: blue, green, purple/violet, orange, and yellow, with only red moving

from second position in Eysenck’s ranking to before orange in Guilford and Smith’s.

Valdez & Mehrabian’s (1994) study revealed that hue’s relationship to emotion

was surprisingly weak. They constructed an emotion model that included arousal,

dominance, and pleasure. They then conducted three studies to determine how saturation

and brightness affected those emotions. Arousal was primarily affected by saturation;

dominance increased with saturation but decreased with additional brightness; and

pleasure increased with saturation and especially brightness.

The purpose of this study is to determine the point, if any, at which the joint

effects of brightness and saturation cause a viewer to prefer a yellow color to a blue

color. Due to the strong factors reported from brightness and saturation, the following

hypothesis was established: Preferences for the two colors will be roughly equal at the

ninth color pair analyzed in the study, and yellow will surpass blue at the tenth pair.

Methodology

Participants

Participants ranged from 17 to 58 years of age, with a mean age of 21. Two

hundred sixty-four participants were college-aged individuals 22 or under, and 33

participants were 23 or above. One hundred thirteen males and 180 females took part in

the study.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 24

Instrument

Blue and yellow were selected for this study as the most liked and disliked hues,

respectively. Ten increments of blue and yellow color swatches were printed on pieces of

paper measuring 8.125 by 6.5 inches. The increments were evenly distributed on the HSB

color model, ranging from the highly unsaturated and dark to the highly saturated and bright

(see Table 1). Each blue swatch was located at H 195, and each yellow swatch at H 57. The

brightest blue and yellow swatches both contained saturation of 100 and brightness of 95,

the highest printable values possible. For each successive increment, both saturation and

brightness were lowered seven points, with the lowest color swatches containing saturation

of 37 and brightness of 32.

Each blue swatch was paired with a yellow swatch, the blue swatches in descending

order; the yellow swatches, in ascending order. Each color pair was affixed to the inside

panels of a manila folder.

Procedure

Each participant was shown one color pair and asked to circle the hue name of the

swatch he preferred (either blue or yellow). Approximately 30 participants evaluated each

color pair.

The study was conducted over the course of six hours in an inner room away from

any windows that might alter the appearance of the colors with shifting daylight. The area

was illuminated by fluorescent, 25-watt T8 bulbs with a color temperature of 4100° K.

Lighting remained constant throughout the course of the study. All curvilinear edges were

trimmed from the manila folders to make both sides uniform.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 25

Table 1

Color Pairs and the Color Swatches’ Values in Four Different Color Models

Color Pair # Blue Yellow

1

HSB 195, 100, 95

RGB 43, 180, 232

CMYK 67, 9, 0, 0

Lab 68, -23, -37

HSB 57, 37, 32

RGB 82, 81, 53

CMYK 59, 51, 80, 41

Lab 34, -3, 17

2

HSB 195, 93, 88

RGB 21, 172, 224

CMYK 71, 13, 1, 0

Lab 65, -23, -37

HSB 57, 44, 39

RGB 99, 98, 56

CMYK 56, 46, 85, 30

Lab 41, -5, 24

3

HSB 195, 86, 81

RGB 31, 162, 206

CMYK 74, 19, 8, 0

Lab 62, -23, -33

HSB 57, 51, 46

RGB 118, 115, 57

CMYK 51, 41, 90, 21

Lab 48, -5, 32

4

HSB 195, 79, 74

RGB 41, 152, 189

CMYK 76, 25, 16, 0

Lab 58, -22, -28

HSB 57, 58, 53

RGB 135, 132, 56

CMYK 47, 36, 95, 13

Lab 54, -7, 40

5

HSB 195, 72, 67

RGB 51, 141, 171

CMYK 78, 33, 24, 1

Lab 54, -20, -24

HSB 57, 65, 60

RGB 153, 148, 53

CMYK 42, 31, 99, 6

Lab 60, -7, 49

6

HSB 195, 65, 60

RGB 54, 128, 153

CMYK 80, 38, 30, 3

Lab 50, -18, -21

HSB 57, 72, 67

RGB 171, 164, 53

CMYK 36, 26, 100, 2

Lab 67, -8, 56

7

HSB 195, 58, 53

RGB 59, 116, 135

CMYK 80, 44, 37, 8

Lab 46, -15, -17

HSB 57, 79, 74

RGB 187, 181, 50

CMYK 31, 20, 100, 1

Lab 72, -9, 63

8

HSB 195, 51, 46

RGB 59, 103, 117

CMYK 80, 49, 42, 16

Lab 41, -13, -13

HSB 57, 86, 81

RGB 206, 198, 43

CMYK 23, 13, 100, 0

Lab 79, -9, 71

9

HSB 195, 44, 39

RGB 58, 89, 100

CMYK 80, 55, 47, 25

Lab 36, -10, -10

HSB 57, 93, 88

RGB 223, 214, 32

CMYK 16, 7, 100, 0

Lab 84, -10, 79

10

HSB 195, 37, 32

RGB 53, 74, 82

CMYK 79, 58, 53, 36

Lab 30, -7, -7

HSB 57, 100, 95

RGB 241, 230, 7

CMYK 9, 1, 100, 0

Lab 90, -10, 87

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 26

Results

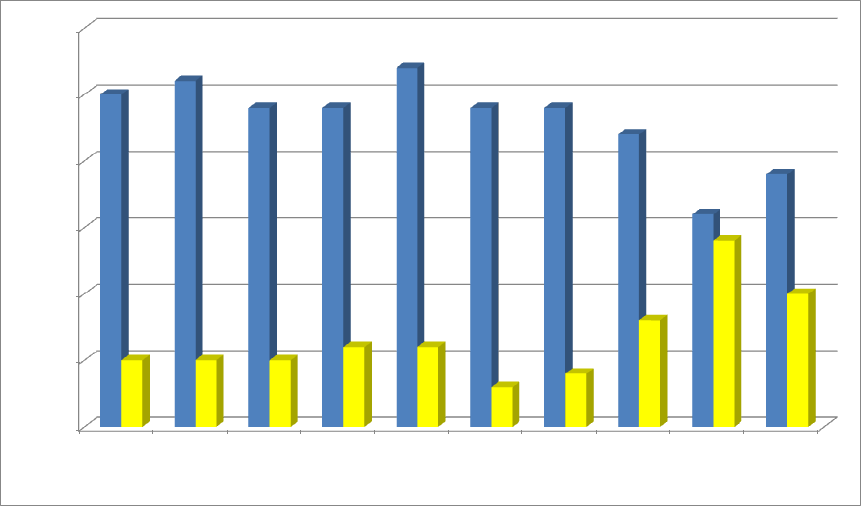

Consistent with previous research and the hypothesis, a chi-square goodness of fit

test confirmed a significant relationship between hue and the participants’ swatch

preferences, X

2

(9, N = 297) = 91.667, p < .001. As expected, color pairs 6-9 showed a

steady decrease in the number of times blue was preferred, while preferences for yellow

increased (see Figure 1). Consistent with the hypothesis, the colors were preferred almost

equally in the ninth pair, where yellow was selected 14 times and blue 16 times.

However, the tenth pair showed an unexpectedly large disparity between the number of

times each color was preferred, in favor of blue. Yellow was never selected more than

blue in any of the color pairs.

Brightness/saturation did have a measurable effect, however. A chi-square test of

independence revealed a significant relationship between color pair shown and color

preference exhibited by the participants, X

2

(9, N = 297) = 18.201, p = .033. Yellow was

chosen twice as often in the tenth pair as it was in the first pair. In both the eighth and

tenth pairs, however, blue was still chosen approximately twice as much as yellow.

Yellow’s worst showings were actually in pairs 6 and 7, where blue was chosen eight and

six times more often, respectively.

Discussion

The study may have been weakenend by the use of hue names to refer to the

swatches. The reason for which the hues were chosen, their extreme standings on the

preference scale, may have carried distracting connotations into participant evaluations,

as each participant was asked to circle either blue or yellow to denote preference.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 27

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Times each color was preferred

Color pairs

Figure 1. Number of preferences according to color in each color pair.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 28

Furthermore, many participants remarked that the darker shades of both colors

appeared black, and many of the intermediate yellow swatches appeared greenish to

observers. Many participants were confused when they were told to refer to certain colors

as blue or yellow when the swatches did not appear to resemble either hue. In such a

circumstance, some of the participants may have resorted to circling blue in an effort to

convey general preferences in relation to their mental concepts of the two hues rather

than choosing between the two color swatches with which they were presented. Crozier

(1999) noted that people may select blue as their favorite color out of convention. The

sudden increase of yellow in pairs 8-10 may be due to the fact that yellow had just

become recognizable to the participants. If the study were to be repeated, the swatches

would not be associated with hue names, and participants would point to designate their

preferred swatches.

The overwhelming preference for blue, even at low brightness and saturation,

may be partially due to the age of the study’s participants. The mean participant age was

21. As Paul (2002) noted, 48% of individuals 21-34 years old listed navy blue/midnight

as their favorite shade of blue, as oppoosed to 32% of 35-54-year-olds and a mere 21% of

individuals 55 and over.

Another complicating factor may have been the quality of the laser output used to

produce the color samples. All the colors printed noticeably darker than they appeared on

screen, even from CMYK documents. If the study were repeated, color swatches would

be printed with ink rather than laser.

This study was ambitious in the sense that it sought a point at which saturation

and brightness could influence participants to choose the least-preferred hue over the

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 29

most-preferred hue. Subsequent studies may find it beneficial to analyze other hue pairs

with less disparity between preference ranking (e.g., green and orange, red and purple).

Furthermore, seeing that blue was overwhelmingly preferred in pairs 1-6, the study could

be repeated with only pairs 7-10 to observe better the points at which

brightness/saturation begins to affect color preference.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 30

References

Alva, M. (2006, December 26). Color me Verizon red, T-Mobile pink and…: Big

telecoms are using hues to create brand identity. Investor’s Business Daily, A07.

Applebaum, M. (2005, May 23). Beware purple people eaters. Brandweek, 46(21), 46.

Berman, M. (2007). Street smart advertising: How to win the battle of the buzz. Lanham,

MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Birren, F. (1997). The power of color: How it can reduce fatigue, relieve monotony,

enhance sexuality, and more. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Pub. Group.

Bleicher, S. (2005). Contemporary color theory and use. Clifton Park, NY:

Thomson/Delmar Learning.

Cheskin research finds that when it comes to packaging, looks count. (1998, September

21). PR Newswire, p. 6494.

Cimbalo, R. S., Beck, K. L., & Sendziak, D. S. (1978). Emotionally toned pictures and

color selection for children and college students. Journal of Genetic Psychology,

133(2), 303-304.

Crozier, W. R. (1999). The meanings of colour: Preferences among hues. Pigment &

Resin Technology, 28(1), 6-14.

Dettmer, J. (2003, September 2). Orange stakes its claim as color du jour. Insight on the

News, 19(19), 55.

Drew, J. T., & Meyer, S. A. (2005). Color management: A comprehensive guide for

graphic designers. Mies, Switzerland: RotoVision.

Elliot, A., & Maier, M. (2007, October). Color and psychological functioning. Current

Directions in Psychological Science, 16(5), 250-254.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 31

Eysenck, H. J. (1941). A critical and experimental study of colour preferences. American

Journal of Psychology, 54(3), 385-394.

Fehrman, C., & Fehrman, K. (2004). Color: The secret influence. Upper Saddle River,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gernsheimer, J. (2008). Designing logos: The process of creating symbols that endure.

New York: Allworth Press.

Gorn, G. J., Chattopadhyay, A., Yi, T., & Dahl, D. W. (1997, October). Effects of color

as an executional cue in advertising: They’re in the shade. Management Science,

43(10), 1387-1400.

Hemphill, M. (1996). A note on adults’ color-emotion associations. The Journal of

Genetic Psychology, 157(3), 275-280.

Hill, R. A., & Barton, R. A. (2005, May 19). Red enhances human performance in

contests. Nature, 435, 293.

Holitzschue, L., & Noriega, E. (1997). Design fundamentals for the digital age. New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

Huang, K., Lin, C., & Chiang, S. (2008, October). Color preference and familiarity in

performance on brand logo recall. Perceptual & Motor Skills, 107(2), 587-596.

Lambert, J. (2004, September 13). Colour schemers. Canadian Business, 77(18), 76-82.

Mastrota, F. N., & Mench, J. A. (1995). Colour avoidance in northern bobwhites: Effects

of age, sex and previous experience. Animal Behavior, 50, 519-526.

McManus, I. C., Jones, A. L., & Cottrell, J. (1981, July). The aesthetics of color.

Perception, 10, 651-666.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 32

Mehta, R., & Zhu, R. (2009, February 27). Blue or red? Exploring the effect of color on

cognitive task performances. Science, 323, 1226-1229.

Nelson, R. P. (1994). The design of advertising. Dubuque, IA: WCB Brown &

Benchmark.

Paul, P. (2002, February 1). Color by numbers. American Demographics, 30.

Peterson, L. K., & Cullen, C. D. (2000). Global graphics: Color: A guide to design with

color for an international market. Gloucester, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Saudi Arabia bans all things red ahead of Valentine's Day. (2008, February 12). [Online

news article]. Retrieved from

http://www.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/meast/02/12/saudi.valentine/index.html

Shank, M. D., & LaGarce, R. (1990). Study: Color makes any message more effective.

Marketing News, 24(16), 12.

Sharp national brand advertising campaign adds color to dynamic HDTV landscape.

(2010, March 18). [Online press release]. Retrieved from

http://www.sharpusa.com/AboutSharp/NewsAndEvents/PressReleases/2010/Marc

h/2010_03_18_QuadPixel.aspx

Singh, S. (2006). Impact of color on marketing. Management Decision, 44(6), 783-789.

Somasundaram, M. (1995, September 18). Red packages lure shoppers like capes

flourished at bulls—Marlboro, Coca-Cola, Colgate wear most popular color on

global market shelves. The Wall Street Journal, 226(54), A9.

Sturgess, D. J. (2008, August 11). A spectrum of missed opportunity. Brandweek, 49(29),

15.

Toufexis, A. (1983, July 18). The bluing of America. Time, 122, 62.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 33

Turquoise: Italy's hottest new color? (2009, October 26). [Web log post]. Retrieved from

http://www.colorassociation.com/blog/2009/11/7/tourquise-hot-new-color-in-

italy.html

Tyler, A. C. (1992). Shaping belief: The role of audience in visual communication.

Design Issues, 9(1), 21-29.

Valdez, P., & Mehrabian, A. (1994). Effects of color on emotions. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: General, 123(4), 394-409.

Wallace, R. (2002). Icons: Your brand’s visual language. Point of Purchase, 8(2), 18.

Wells, D. L., McDonald, C. L., & Ringland, J.E. (2008). Color preference in gorillas

(gorilla gorilla gorilla) and chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). Journal of

Comparative Psychology, 122(2), 213-219.

Williams, T. S. (2001). The graphic designer’s guide to pricing, estimating, & budgeting.

New York: Allworth Press.

Wong, W. (1997). Principles of color design: Designing with electronic color. New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

Wright, A. (1998). A beginner’s guide to color psychology. London: Kyle Cathie

Limited.

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 34

Appendix

Color Models

RGB (Red, Green, Blue)

RGB is an additive color process (Wong, 1997) in which colors are created by

emitted light, as opposed to pigments (Holitzschue & Noriega, 1997). If red, green, and

blue are all set to full intensity, they will combine to form white light. The three colors at

50% form a medium gray; at 0%, they form black. The RGB model corresponds with

three cone systems in the human eye, which sense red, green, and blue (Drew & Meyer,

2005). Screens emit red, green, and blue electron beams (Wong). Combinations of these

beams at varying intensities can produce 256 colors with pixels of 8-bit depth. Projected

light has a greater gamut, or spectrum range (Holitzschue & Noriega), than printed colors

can offer (Drew & Meyer).

In March 2010, Sharp announced its plans to release AQUOS LED LCD TVs that

would incorporate yellow as the fourth subpixel (“Sharp National Brand,” 2010). Their

revolutionary RGBY quad pixel technology produces its own color gamut that better

approximates the range of colors visible to the human eye. Because its display cannot be

replicated on regular RGB screens, the AQUOS slogan is, “You have to see it, to see it”

(“Sharp National Brand,” 2010).

CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black)

CMYK, a subtractive color process, is directly inverse to RGB (Wong, 1997).

Unlike a light source emitting colored light, CMYK print material actually absorbs these

colors from light (Holitzschue & Noriega, 1997). Cyan, magenta, and yellow ink absorb

red, green, and blue light, respectively. Unlike RGB, which emits and reveals, CMYK

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY 35

absorbs and conceals. White appears only in the absence of subtractive pigments, and

true black appears when cyan, magenta, yellow, and black are all set to 100% (Drew &

Meyer, 2005). Based on this model, color printers use cyan, magenta, yellow, and black

ink.

HSB (Hue, Saturation, Brightness)

The HSB mode measures colors in the traditional dimensions of hue, saturation,

and brightness (Wong, 1997). It is also called HLS (hue, lightness, saturation) and HSV

(hue, saturation, value). It is neither additive nor subtractive; rather, HSB is a tool for

color selection in design software (Holitzschue & Noriega, 1997). Its color map is a circle

with no saturation at its center and full saturation of the various hues around its

circumference. A vertical slider bar allows the user to alter the value of the entire map.

CIE

The Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE) has devised a complex color

model that measures not only color production, but human color perception (Drew &

Meyer, 2005). Like RGB, the CIE system uses an additive red, green, and blue model.

However, this three-dimensional model takes into account not only visible color but also

the light source present, and the observer. It includes the tristimulus values X, Y, and Z

that calculate how much red, green, and blue humans with normal vision can perceive.

CIE’s gamut is even larger than the spectral range humans can perceive. Some CIE

colors are theoretical only, as they are beyond the visible gamut.