NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

THE INITIAL EFFECTS OF THE EXPANDED CHILD TAX CREDIT

ON MATERIAL HARDSHIP

Zachary Parolin

Elizabeth Ananat

Sophie M. Collyer

Megan Curran

Christopher Wimer

Working Paper 29285

http://www.nber.org/papers/w29285

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

September 2021

The authors wish to thank The JPB Foundation and the Annie E. Casey Foundation for grant

support. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2021 by Zachary Parolin, Elizabeth Ananat, Sophie M. Collyer, Megan Curran, and

Christopher Wimer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may

be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the

source.

The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material Hardship

Zachary Parolin, Elizabeth Ananat, Sophie M. Collyer, Megan Curran, and Christopher Wimer

NBER Working Paper No. 29285

September 2021

JEL No. H53,I3,I38,J13

ABSTRACT

The transformation of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) into a more generous, inclusive monthly

payment marks a historic (temporary) shift in U.S. treatment of low-income families. To

investigate the initial impact of these payments, we apply a series of difference-in-difference

estimates using Census Household Pulse Survey microdata collected from April 14 through

August 16, 2021. Our findings offer three primary conclusions regarding the initial effects of the

monthly CTC. First, payments strongly reduced food insufficiency: the initial payments led to a

7.5 percentage point (25 percent) decline in food insufficiency among low-income households

with children. Second, the effects on food insufficiency are concentrated among families with

2019 pre-tax incomes below $35,000, and the CTC strongly reduces food insufficiency among

low-income Black, Latino, and White families alike. Third, increasing the CTC coverage rate

would be required in order for material hardship to be reduced further. Self-reports suggest the

lowest-income households were less likely than higher-income families to receive the first CTC

payments. As more children receive the benefit in future months, material hardship may decline

further. Even with imperfect coverage, however, our findings suggest that the first CTC payments

were largely effective at reducing food insufficiency among low-income families with children.

Zachary Parolin

Columbia University

and Bocconi University

Elizabeth Ananat

Barnard College

Columbia University

3009 Broadway

Office 1019 Milstein Building

New York, NY 10027

and NBER

Sophie M. Collyer

Columbia University

Megan Curran

Columbia University

School of Social Work

1255 Amsterdam Avenue

7th floor

New York, NY 10027

Christopher Wimer

Columbia University

1255 Amsterdam Avenue

Office 735

New York, NY 10027

A data appendix is available at http://www.nber.org/data-appendix/w29285

2

INTRODUCTION

In March 2021, the United States (U.S.) Congress passed the American Rescue Plan (ARP),

which included a large expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The ARP increased the benefit

values of the CTC, removed the earnings requirement and made the benefit fully refundable, and

shifted the distribution schedule from a once-per-year payment of the CTC to monthly payments.

The first monthly payment was distributed to families of 59.3 million children in July 2021, while

the second payment reached 60.9 million children in August 2021 (U.S. Department of Treasury,

2021a). The CTC expansion marks a notable shift in the American welfare state’s treatment of

low-income families; however, the program is implemented only for one year and, in the absence

of Congressional renewal, will expire in 2022. As such, timely and reliable evidence is critical for

informing policymakers, researchers, and the public of the CTC’s short-term consequences. This

study investigates the effects of the expanded CTC on material hardship among families with

children in the initial weeks after the first CTC payment.

A large body of research shows that children who grow up in families with higher incomes

perform better across a host of measures of both short- and long-term development and well-being

(Brooks-Gunn and Duncan, 1997; Chaudry and Wimer, 2016). And a smaller but growing body

of literature attempts to understand whether these relationships are causal, given the fact that

lower- and higher-income families may differ on numerous fronts besides income alone. Most of

these studies use so-called “natural experiments,” which attempt to identify quasi-random

variation in income to see whether that exogenous change predicts changes in important child

outcomes. This growing literature is so far consistent in finding that enhanced incomes and reduced

poverty causally impact children’s short- and long-term development and well-being (Duncan,

Morris and Rodrigues, 2011; Wimer and Wolf, 2020; Garfinkel et al., 2021).

3

There are two primary channels through which increases in income are thought to impact

children’s outcomes (NAS, 2019). The family stress channel posits that the absence of resources

increases stress, which compromises healthy parenting and other family relationships, resulting in

worse child outcomes. The family resources channel posits that increased income allows parents

to purchase or invest in various things that enhance child development and well-being (e.g., books,

toys, enriching activities, academic supports, safer neighborhoods, etc.). Each channel assumes

that an increase in income would change aspects of the home environment in the shorter term, and

that these effects would accumulate over time into more positive child outcomes.

This study seeks to add to this burgeoning literature by looking at the short-term impacts

of the CTC, which now extends income support to children historically left out of the full benefit

of the credit (Collyer, Harris and Wimer, 2019; Goldin and Michelmore 2020). We apply

difference-in-difference estimates to take advantage of (1) the fact that effects of the policy differ

between households with children and those without, and (2) that households with children benefit

differentially based on the ages of their children, number of children, and pre-reform income

levels.

The Expanded Child Tax Credit

Since the mid-1990s, the American welfare state has relied more on in-kind transfers, such

as benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and work-conditional

transfers, such as benefits from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), relative to cash-based

income support (Bauer et al., 2018; Hoynes, 2019; Pac et al., 2017). As a result, share of children

in families with very little cash income has grown (Shaefer & Edin, 2013). The lack of cash-based

assistance and the comparatively high rate of child poverty sets the U.S. apart from other high-

income countries, most of which have some form of child allowance (Curran, 2015; Garfinkel et

4

al., 2016; Shaefer et al., 2018). The expansion of the CTC thus represents a historic deviation from

the direction of the U.S. welfare state throughout the past three decades.

Prior to the expanded CTC, tax filers could receive a maximum CTC of $2,000 per child

per year, but it was not fully refundable.

1

One in three children did not receive the full benefit

value because their families did not earn enough to qualify. Children with single parents, those in

rural areas, Black and Latino children, and those in larger families were disproportionally

ineligible for the full credit (Curran and Collyer, 2020; Collyer, Harris, and Wimer, 2019).

Following similar parameters to the American Family Act (a bill first introduced in both the Senate

and House of Representatives in 2017 and reintroduced in 2019), the ARP has temporarily

transformed the CTC into a nearly-universal child allowance for 2021.

2

Specifically, the ARP

includes three fundamental changes to the CTC. First, it makes the CTC available to almost all

children, including those in families with the lowest incomes previously excluded, by removing

the earnings requirement and making the credit fully refundable. Second, it raises the maximum

annual credit amounts to $3,000 for children ages 6-17 and $3,600 for children under age 6. Third,

beginning mid-July 2021, it delivers the credit in monthly installments of up to $250 per older

child or up to $300 per younger child, for a period of six months.

3

One challenge facing the introduction of the expanded CTC is that not all eligible children

automatically receive the payments. Families who did not file taxes in the prior year, presumably

due to having an income below the tax-filing threshold, generally must register with the Internal

1

See additional information on the history of the Child Tax Credit, see Crandall-Hollick (2021), Crandall-Hollick (2018), and Garfinkel et al.

(2016).

2

The expansion to the CTC in the ARP mirrors the proposed reforms in the American Family Act (AFA) with one exception: in the AFA, the

credit would begin to phase out for heads of household with earnings above $120,000 or and joint filers with Adjusted Gross Incomes (AGI) over

$180,000. In the ARP, the credit begins to phase out for families with AGIs above $112,500 or $150,000 per year, depending on filing status, but

it only phases out until matching the credit values that a family would receive under prior law. This alteration was made because the Biden

administration committed to not raising taxes for those with incomes below $400,000 per year.

3

Because the payments began halfway through the year, families will receive half of the full amount of their credit in 2021 and the remainder when

they file taxes in 2022.

5

Revenue Service (IRS) in order to receive benefits. Several estimates suggest that the total number

of children in eligible tax units is around 64 to 67 million children (Parolin et al., 2021b), more

than the 60.9 million to whom the IRS distributed CTC payments to in August 2021. Put

differently, the first payments did not reach all eligible families. As we discuss in our Data and

Methods section, we take several steps to account for the imperfect coverage of the initial CTC

payment when evaluating the policy’s effects on hardship.

Despite the challenge in reaching full coverage, early research suggests the expanded CTC

has potential to generate large reductions in child poverty (Center on Poverty and Social Policy,

2021; Marr et al., 2021; Acs and Werner, 2021; Parolin et al., 2021a; Wheaton et al., 2021) and

may contribute to reductions in economic hardship (Perez-Lopez, 2021). Thus far, however, it

remains unclear whether the expanded CTC has plausibly causal effects. This study investigates

that possibility, using household data released in the initial weeks following the first CTC payment,

to assess the policy’s effects on material hardship among families with children.

DATA AND METHODS

Data Source: This study uses data from the Census Household Pulse Survey (Pulse). The

U.S. Census Bureau introduced the Pulse in April 2020 to begin collecting up-to-date and

nationally-representative information on the social and economic wellbeing of households across

the U.S. The Census Bureau randomly selects addresses to participate in the Pulse, then sends

either an email or a text message to the contact information associated with the household. The

message prompts the recipient to participate in a 20-minute online survey asking questions

related to education, employment, food security, housing, and more. The data have been used to

track trends in material hardship, subjective wellbeing, and other social and economic indicators

throughout the pandemic (Bauer et al., 2020; Bitler et al., 2020; Morales et al., 2020;

6

Schanzenbach and Pitts, 2020; Ziliak, 2021; Cai et al., 2020, Twenge and Joiner, 2020). Our

particular focus in this analysis centers on the hardship data, but there is potential to use the

Pulse data to explore the relationship between the CTC monthly payments and subjective

wellbeing (see Appendix E).

We use Pulse data collected between April 14, 2021 (three months before the start of the

monthly CTC) through August 16, 2021 (waves 28-35). The first payment of the expanded CTC

was delivered to recipients on July 15, 2021, which falls prior to the beginning of Wave 34 of the

Pulse (which spans July 21 to August 2, 2021). The second payment was delivered on August

13, 2021. Our total sample size is 411,613 respondents.

One limitation of the Pulse is that is conducted online-only (often sent via text message with

a link to complete a survey online), which may exclude segments of the population who lack

reliable internet connection. We provide descriptive statistics on the respondents in Appendix I.

The descriptive statistics show that the Pulse sample closely mirrors population estimates from

the U.S. Current Population Survey.

Sample Criteria: We exclude all households in the Pulse who have imputed values of

number of children in the household, as error in the imputed values could bias our estimates. In

our sample, 1.3 percent of all responses featured imputed values of the number of children.

Given that the expanded CTC should benefit lower-income households more so than higher-

income households, we restrict our primary estimates to households with a 2019 pre-tax income

of under $35,000 (“low-income families”). In subsequent estimates, however, we also display

results when assessing the effect of the CTC on all households under $25,000 and at different

income bins up to $200,000 in 2019 pre-tax income. We also display subgroup analyses to

estimate the effects of the CTC by race and ethnicity.

7

Receipt of the CTC: As noted, the first two payments of the CTC did not reach all children in

eligible families. Though the Department of Treasury reports that 60.9 million children (around

83 percent of all children) received the second payment, the Pulse includes its own question of

whether the household received a CTC payment (U.S. Department of Treasury, 2021a). We thus

begin our Findings section with a descriptive portrait of coverage rates as reported in the Pulse.

Indicators of Material Hardship: Table 1 presents our primary measures of material

hardship. Our material hardship indicators include household food insufficiency, difficulty with

expenses, and not being caught up on rent or mortgage payments. We operationalize each of

these indicators as a binary variable using the criteria described in the right-most column of

Table 1. In a parallel exercise, we explore early indications of the relationship between the new

CTC monthly payment and three measures of subjective wellbeing, including confidence in

paying the rent/mortgage, frequent anxiety, and frequent worrying. These results are included in

Appendix E; as the monthly CTC payments continue and more data becomes available, this

represents an area for continued investigation. In general, however, we would expect measures of

subjective wellbeing to be more sensitive to continued receipt of monthly payments than to just

the initial payments.

8

Table 1: Overview of primary hardship indicators

Type

Prompt

Qualifying

Responses

Household food

insufficiency

In the last 7 days, which of these statements

best describes the food eaten in your

household?

Sometimes or often

not enough to eat

Difficulty with expenses

In the last 7 days, how difficult has it been for

your household to pay for usual household

expenses, including but not limited to food,

rent or mortgage, car payments, medical

expenses, student loans, and so on?

Somewhat or very

difficult.

Not caught up on rent [or

mortgage]

Is this household currently caught up on rent

[or mortgage] payments?

No.

Methods: We estimate difference-in-difference models to assess the effect of the

expanded CTC on our outcomes of interest, as defined in Equation (1).

=

1

+

2

+

3

(

∗

)

+

4

+

(1)

The outcome variable is one of our hardship indicators (separate models for each).

PostCTC is a binary indicator of whether the time of survey occurred after July 15, 2021, the day

on which the expanded CTC was first administered. We specify our treatment variable,

Treatment, in two separate ways. First, we operationalize a binary treatment indicator measured

as whether the household has children (value set to 1) or is childless (value set to 0). Given that

our sample is limited to households reporting a 2019 pre-tax income of under $35,000, we

assume (but cannot directly test) that the vast majority of households with children in this

subsample are eligible to receive the monthly CTC. Childless households, in contrast, do not

directly benefit from the reform.

For our second treatment definition, we estimate models using a continuous measure of

treatment intensity to capture the fact that the effects of the CTC are likely to vary by age of the

9

children (as families with children under age 6 receive larger monthly benefit values), the

number of children in the home, and the relative value of the new CTC benefits compared to

what the family likely received from the CTC prior to the reform. We cannot consistently

observe the age of each child in a given household in the Pulse, nor do we have information on

pre-reform CTC receipt.

4

Thus, we use data from the 2019 U.S. Current Population Survey to

estimate the mean pre- and post-reform benefit values for bins defined by the number of adults in

the household (ranging from 1 to 10), the number of children in the household (ranging from 0 to

10), and eight categorical pre-tax income bins (from under $25,000 annually scaling up to more

than $200,000 per year). We compute the mean pre-reform refundable CTC benefits as observed

for each family unit in the CPS ASEC. We then simulate the additional post-reform benefits that

each family is eligible for (not yet taking into account imperfect coverage in benefit distribution)

using detailed policy rules from the CTC reform as specified in the 2021 American Rescue Plan.

We subtract the pre-reform benefit value from the post-reform benefit value to create a “net

benefit” indicator for each family unit. We then adjust the net benefit indicator for family size

using the modified OECD equivalence scale.

5

Finally, we calculate the weighted mean of the

size-adjusted net benefit value for each of the bins defined above. We then import this value into

the Pulse, matching on the number of adults, number of children, and 2019 pre-tax income

category of the Pulse respondents. We provide more details and descriptive statistics on the

indicator in Appendix B.

4

Wave 34 of the Pulse does have binary variables of whether children are under 5 or between 5 to 11. Given that the

data are not consistently available throughout the waves included in this analysis, however, we cannot use it in our

estimations or creation of the treatment indicators.

5

The modified OECD scale begins with a value of 1 for a single adult, then adds 0.5 for each child in the home and

0.3 for each additional adult in the home. Alternative family-size adjustments include the square-root equivalence

scale or dividing by a family-size-adjusted poverty-threshold, such as that of the U.S. official poverty measure.

10

In a sensitivity test, we also produce an alternative version of our treatment intensity

indicator that matches the July 2021 coverage rate of the CTC – 59.3 million children – as

reported by the U.S. Department of Treasury. Specifically, we scale down coverage from all

likely-eligible children to match the reported numbers of children receiving the CTC by state,

following the procedure in Parolin, Collyer, Curran, and Wimer (2021b). Within each state, we

adjust coverage so that it is the lowest-income tax units who are removed first, representing the

fact that lower-income tax units are less likely to have filed taxes in the prior year and, thus, are

less likely to receive the benefits automatically (Cox, et al., 2021). In our Findings section, we

also present observed coverage rates from the Pulse among households with children by income

bin; these results corroborate the claim that the lowest-income households with children were

less likely to receive the benefit in July 2021. We present the results from our sensitivity tests in

Appendix B, but we note that they do not vary meaningfully from the results of our primary

analyses.

In Equation (1), we control for the age, sex, and education status of the household head,

and we include state fixed effects (captured in vector X). In each estimate,

3

is our primary

coefficient of interest, as it informs us, when using the binary treatment indicator, of whether

households with children faced a larger (or smaller) difference in the outcome relative to

childless households after the introduction of the CTC.

While Equation (1) provides us the intent-to-treat effect (or the effect of the treatment on

the full treatment group, regardless of whether they report actually receiving the CTC), we also

provide estimates of the treatment effect on the treated (or the local average treatment effect). To

do so, we estimate two-stage least squares models (2SLS) using the treatment group identifier as

an instrumental variable and observed receipt of the treatment as the endogenous variable. When

11

applying our binary treatment, observed receipt of the treatment reflects whether the family

reports in the Pulse that it actually received the monthly CTC payment(s). When applying our

continuous treatment indicator, the observed treatment in the 2SLS model is the family’s

projected net benefit increase from the CTC. Because levels of the benefit receipt of the CTC are

not directly measured in the Pulse, we apply our projected value of the net CTC benefit based on

the family’s income, number of children, and number of adults (as defined above) as the

observed treatment; however, we convert the projected benefit value to zero for families

reporting that they did not receive the CTC payment.

FINDINGS

Our Findings section proceeds in three parts. First, we discuss reported receipt of the

CTC in the Pulse and compare this to administrative reports from the U.S. Department of

Treasury. Second, we present descriptive findings on trends in material hardship. Third, we

present the results of our difference-in-differences estimates.

Reported Receipt of the Child Tax Credit

As noted, the U.S. Department of Treasury reports that 59.3 million children received the

first CTC payment in July 2021, while 60.9 million received the second payment in August 2021

(U.S. Department of Treasury, 2021a). Estimates from the Pulse, however, suggest that 66

percent of children were in households that report receiving the initial CTC payment. This is

equivalent to approximately 48 million children, or 12 million fewer than the IRS reports. The

discrepancy could be due a number of factors: sampling bias in the Pulse, benefit underreporting

in the Pulse, overestimation of children served from the Department of Treasury, or general

measurement error. Regardless of cause, all results should be interpreted with this discrepancy in

12

mind. Moreover, the coverage rate is likely to increase in subsequent months, considering that

1.6 million additional families received the benefit in August relative to July (Department of

Treasury, 2021b).

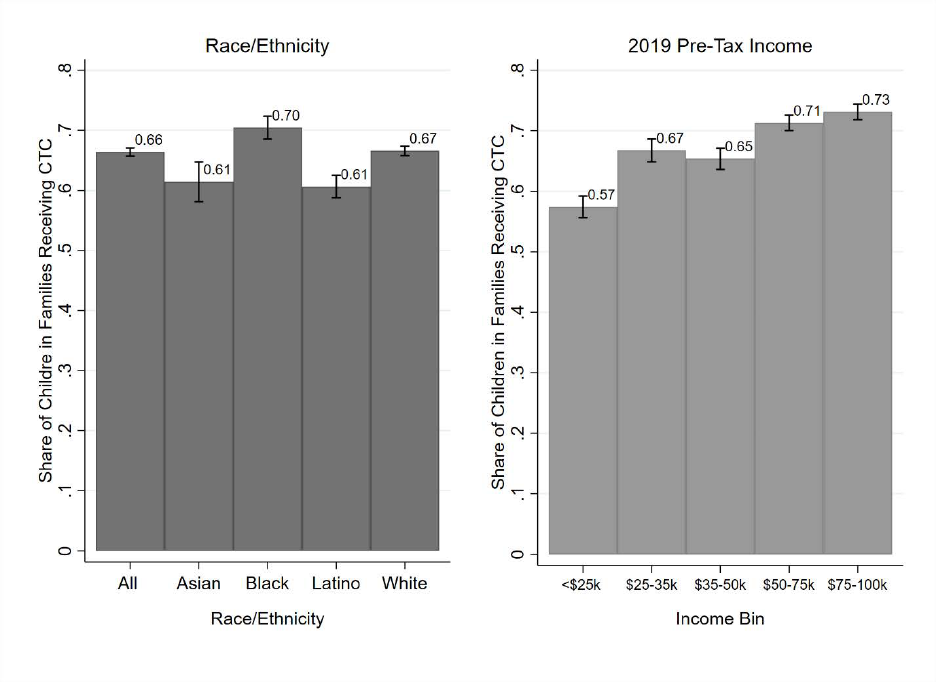

Figure 1: Share of children in families receiving the first or second payment of the Child Tax

Credit (self-reported receipt from responses of Census Household Pulse Survey)

Note: Race and ethnicity refers to that of the household head in which the child lives. Coverage rates are

across the entire sample of households with children and are not limited to eligible households, as

eligibility cannot be inferred with precision in the Pulse.

Figure 1 breaks down reported CTC receipt rates by race and ethnicity (left panel) and

2019 pre-tax income bin (right panel). As noted, 66 percent of all children are in households that

report receipt of the first or second payment of the CTC in the Pulse, including 61 percent of

Asian children, 70 percent of Black children, 61 percent of Latino children, and 67 percent of

White children. Keep in mind that the sample here is not limited to eligible family units, and that

13

not all children in the U.S. are eligible; thus, the reported means should be interpreted as general

coverage rates and not take-up among the eligible.

The results by income bin (right panel) suggest that families with children that had 2019

pre-tax incomes below $25,000 are less likely than higher-income families to have received the

benefit. According to the Pulse data, just over half (57 percent) of children in families with

incomes under $25,000 received the first or second payment. Rates of (self-reported) receipt rise

as incomes rise. Among families with earnings between $25,000 to $35,000, more than two-

thirds (67 percent) of children received the benefit. Among families with incomes between

$75,000 and $100,000, approximately three-quarters (73 percent) of children received the

payment.

Given the comparatively low coverage rates among the lowest-income families, it is

unlikely that the initial effects of the CTC match the potential effects if coverage were greater, or

the future effects assuming that coverage does, indeed, expand. As such, the results below should

be interpreted as the immediate effects with imperfect coverage. Presumably, any effects

observed in the results below will increase as more families receive the benefit in subsequent

months.

Descriptive Findings

Figure 2 presents descriptive trends from April 2021 through August 2021 for each of the

outcomes for childless households (dashed gray line) and households with children (solid black

line) with 2019 pre-tax incomes below $35,000. The red vertical line in each figure marks the

first payment of the expanded CTC.

14

Figure 2: Trends in hardship for low-income households with and without children (April 14 to

August 16, 2021; households with less than $35,000 in 2019 pre-tax income)

Note: Red vertical line represents the date of the first payment of expanded Child Tax Credit. See Table 1

for definition of each outcome. Sample limited to households with 2019 pre-tax income under $35,000.

Food insufficiency (left panel) is consistently higher for low-income households with

children relative to low-income childless households for the entire period considered. From April

through to the end of June 2021, both groups see slight increases in food hardship, with low-

income childless households reaching 19.5 percent in June compared to 29.8 percent for low-

income households with children. After the first payment of the CTC, however, food

insufficiency remains relatively stable for low-income childless households (around 19 percent),

but declines from 29.8 percent to 20.8 percent for households with children in late July 2021. In

mid-August, the point estimate rises slightly to 21.8 percent. The change from late-June to mid-

15

August marks an 8 percentage point, or 27 percent, decline in food insufficiency for low-income

households with children.

The middle panel shows that low-income households with children tend to face much

higher rates of difficulty with expenses relative to childless households (in late June 2021, 59.9

percent to 45.5 percent, respectively). These gaps do not meaningfully change after the first

payments of the CTC.

Households with children are also more likely to have missed rent or mortgage payments

(right panel) over the entire period considered. As with difficulty in meeting expenses, the gaps

in missed rent or mortgage payments do not change notably after the initial CTC payments.

Estimation Results

Table 2 presents the results from our difference-in-differences estimates using our binary

treatment (which, as described in the prior section, is set to a value of one for households with

children) among our subsample of households with pre-tax income of $35,000 or less in 2019.

Our initial analysis, presented in Columns 1-3 of Table 2, assumes that all households

with children under the $35,000 threshold are eligible to receive the CTC (regardless of whether

they actually report receiving the benefit). The secondary analysis, presented in Columns 4-6 of

Table 2, presents the 2SLS estimates of the treatment effect on the treated (those who report

receiving the CTC payments).

16

Table 2: Difference-in-differences estimate of effect of expanded CTC on hardship among households

with 2019 total pre-tax income below $35,000; binary treatment

Intent to Treat Effect

Average Treatment Effect on the Treated

1: Food

Insufficiency

2: Difficulty

w/ Expenses

3: Missed

Rent or

Mortgage

4: Food

Insufficiency

5: Difficulty

w/ Expenses

6: Missed

Rent or

Mortgage

Household with

Children

0.06

***

0.11

***

0.06

***

0.06

***

0.11

***

0.07

***

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

Post-July 15

0.01

0.05

***

0.02

*

0.01

0.05

***

0.02

*

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

Household with

Children X

Post-July 15

-0.075

***

-0.02

0.00

-0.14

***

-0.05

0.01

(0.02)

(0.02)

(0.01)

(0.03)

(0.03)

(0.03)

Pre-Treatment

Mean among HH

w/ Children in

Subsample

0.276 0.594 0.192 0.276 0.594 0.192

Reported CTC

Receipt among HH

w/ Children in

Subsample

52.7% 52.7% 52.9% 52.7% 52.7% 52.9%

Observations

76,523

76,582

76,085

76,523

76,582

76,085

Note: All models include state fixed effects and control for age, education, and sex of household head. Sample

limited to respondents in Pulse reporting 2019 pre-tax income of below $35,000. Treatment effect on the treated

measured using two-staged least squares regression with treated respondents (those reporting receipt of CTC) as the

endogenous variable and treatment group (low-income households with children) as instrumental variable. Robust

standard errors in parentheses. ⵜ p < 0.10,

*

p < 0.05,

**

p < 0.01,

***

p < 0.001.

Consistent with the descriptive trends, our results suggest a significant decline in food

insufficiency for households with children relative to childless households pre- versus post-

rollout of the monthly CTC (see Column 1). Specifically, the results suggest that the intent-to-

treat effect amounts to a 7.5 percentage point decline in food hardship for households with

children relative to childless households after the treatment. This is consistent with the

descriptive statistics observed before. For context, the effect size is around one-fourth the pre-

treatment mean of food insufficiency among households with children in the sample (pre-

17

treatment mean of 27.6 percent). Relative to the rate of food insufficiency in late June (29.8

percent), the effect of the CTC marks a 25 percent decline in this form of hardship.

The effect of the CTC among the treated (families who report receiving the benefit), as

shown in Column 4 of Table 2, is a 14-percentage point decline, or around 50 percent of the pre-

treatment mean of food insufficiency for households with children in the sample. Put simply, the

first two CTC payments are associated with a marked decline in food insufficiency among low-

income households with children.

Households with children also appear to experience a small decline in the difficulty with

expenses relative to childless households (see Columns 2 and 5 of Table 2); however, the effects

are not statistically significant. Moreover, the magnitude of the effect is notably smaller than that

of food insufficiency, consistent with the descriptive trends.

Similarly, our results suggest that the CTC does not have immediate effects on missed

rent or mortgage payments among low-income households with children. This null effect is

perhaps unsurprising given evidence that families receiving the benefit are more likely to have

spent their payments on food items (Perez-Lopez, 2021), and that as of this writing our results

estimate the effects of the initial CTC payments.

18

Table 3: Difference-in-differences estimate of effect of an additional $100 of expanded CTC on hardship

among households with 2019 total pre-tax income below $35,000 (continuous measure of treatment

intensity)

Intent to Treat Effect

Average Treatment Effect on the Treated

1: Food

Insufficiency

2: Difficulty

w/ Expenses

3: Missed

Rent or

Mortgage

4: Food

Insufficiency

5: Difficulty

w/ Expenses

6: Missed

Rent or

Mortgage

Net Gain (in $100s)

from CTC

0.03

***

0.06

***

0.04

***

0.03

***

0.06

***

0.04

***

(0.00)

(0.00)

(0.00)

(0.00)

(0.00)

(0.00)

Post-July 15

0.01

0.05

***

0.02

*

0.01

0.05

***

0.02

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

Net Gain (in $100s)

from CTC X Post-

July 15

-0.04

***

-0.01

0.00

-0.06

***

-0.01

0.00

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

(0.01)

Pre-Treatment

Mean among HH

w/ Children in

Subsample

0.276 0.594 0.192 0.276 0.594 0.192

Reported CTC

Receipt among HH

w/ Children in

Subsample

52.7% 52.7% 52.9% 52.7% 52.7% 52.9%

Observations

75,943

76,004

75,512

75,943

76,004

75,512

Note: Treatment intensity indicators are divided by 100 for easier interpretation of coefficients. All models include

state fixed effects and control for age, education, and sex of household head. Treatment effect on the treated

measured using two-staged least squares regression with estimated received benefit value among families reporting

receipt of the CTC as the endogenous variable and treatment indicator (potential net benefit value of CTC) as

instrumental variable. Sample limited to respondents in Pulse reporting 2019 pre-tax income of below $35,000.

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ⵜ p < 0.10,

*

p < 0.05,

**

p < 0.01,

***

p < 0.001.

Table 3 now applies our continuous indicator of treatment intensity for the CTC

specifically among households with children. Recall that the treatment intensity indicator

captures variation based on pre-tax income and household size (see Appendix B for more

details). The findings are consistent with those from Table 2. Looking at food insufficiency, the

results suggest that a $100 size-adjusted increase in CTC treatment intensity is associated with a

4-percentage point decline in food insufficiency among families with children (Column 1 of

Table 3). The treatment effect on the treated (Column 4 of Table 3) is 6 percentage points. Put

19

differently, a $100 net increase in CTC benefits (adjusted for family size) is associated with a 6-

percentage point, or roughly 22 percent, decline in food insufficiency for low-income families

with children who report receiving the CTC.

To contextualize this finding, note that a standard monthly benefit payment for a single

parent with a 7-year-old child is $250, or $192 after equivalizing for family size. Using the effect

magnitude from the treatment effect on the treated estimates, a standard payment for this single

parent is thus associated with an 11.5 percentage point (192 * 0.06 /100) reduction in the

likelihood of food insufficiency after receiving the initial CTC payments. The estimated

reduction effect is, of course, even stronger for families with higher size-adjusted benefit values.

In contrast to the CTC’s effects on food insufficiency, however, its effects on difficulty

with expenses and missed rent or mortgage payments are again smaller and insignificant (see

Columns 2, 3, 5, and 6 of Table 3).

20

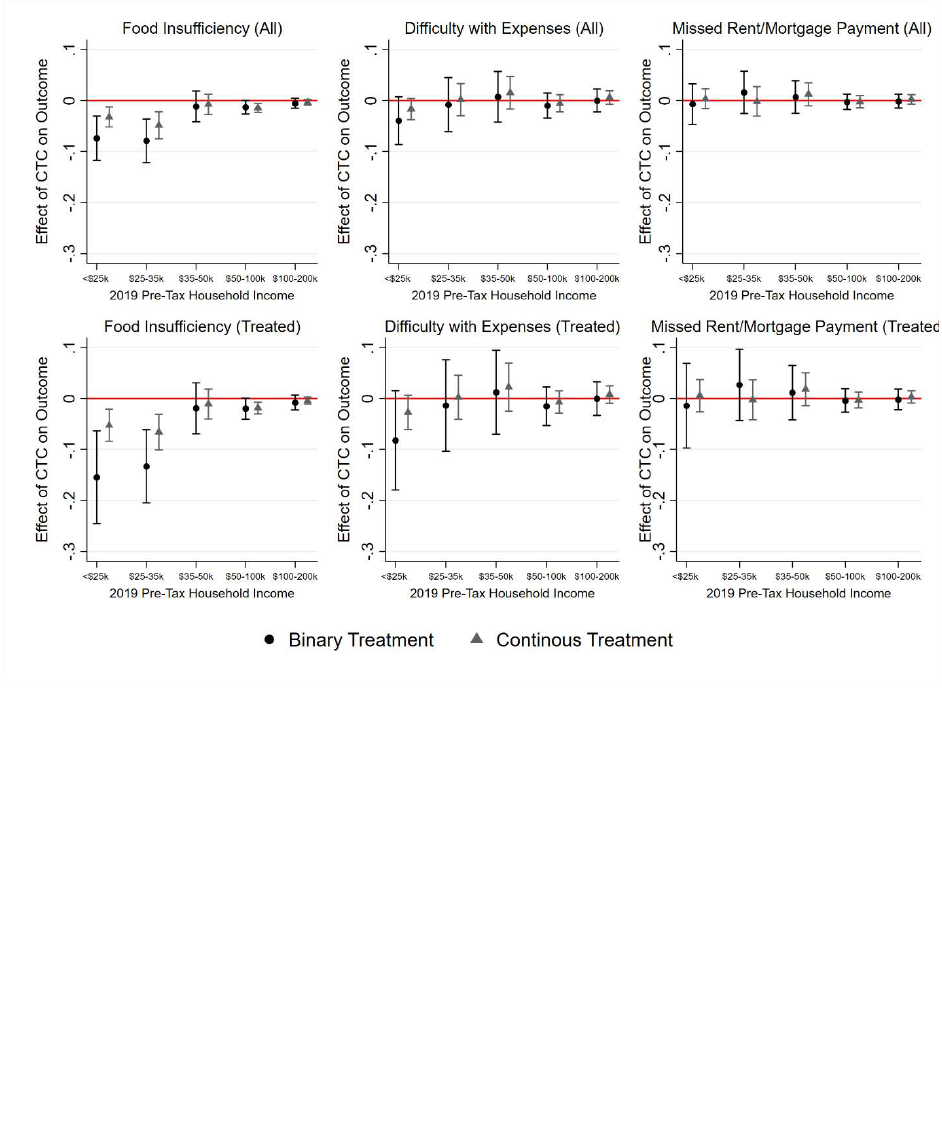

Figure 3: Estimated effect of CTC on outcome by 2019 pre-tax household income cutoff and treatment

specification

Note: Y-axis plots coefficients from interaction of treatment indicator and post-treatment period indicator, similar to

results from Tables 1 and 2. All models include state fixed effect and age, education, and sex controls. Separate

estimates run for each income group displayed on Y-axes.

Recall that the sample in our primary analyses was limited to households with 2019

incomes under $35,000. Figure 3 relaxes that condition and instead visualizes the effect of the

CTC across the income distribution. Each point in Figure 3 represents the coefficient from the

interaction terms for our binary treatment (black circle) and continuous treatment (gray triangle)

when including households with 2019 incomes under $25,000, then between $25,000 to $35,000,

$35,000 to $50,000, $50,000 to $100,000, and $100,000 to $200,000. The upper row presents the

21

intent-to-treat effects, while the lower row presents the effects among families reporting receipt

of the CTC.

The findings, in short, demonstrate that the CTC is particularly effective at reducing food

insufficiency for households with children with 2019 pre-tax incomes below $25,000 and

between $25,000 to $35,000. At higher income bins, the policy has no statistically significant

effect. The results are relatively consistent with examining the effects among the treated. These

patterns emphasize that the CTC is particularly effective at reducing food hardship among lower-

income families.

The middle and right panels of Figure 3 show the null effects across the income

distribution of the initial CTC payments on difficulty with expenses and missed rent or mortgage

payments.

Figure 4 presents the results by race and ethnicity. We again limit the sample the

household heads of the specified race and ethnicity, and then apply the same treatment

conditions as in our primary analysis. The upper-left panel suggests that the intent-to-treat effects

of the CTC on food insufficiency are primarily channeled among Black, Hispanic, and White

families. Similarly, the lower-left panel finds negative and significant reduction effects among

Black, Hispanic, and White families, but not Asian families (though point estimates are negative

for Asian families, though not statistically significant). Put differently, low-income Black,

Hispanic, and White families alike saw decreases in food hardship as a result of the initial

monthly CTC payments.

22

Figure 4: Estimated effect of CTC on outcome by race and ethnicity and treatment specification

Note: Y-axis plots coefficients from interaction of treatment indicator and post-treatment period indicator, similar to

results from Tables 1 and 2. Sample limited to households with 2019 income under $35,000. All models include

state fixed effects and age, education, and sex controls. Separate estimates run for each group displayed on Y-axes.

The middle and right panels of Figure 4 again suggest that the first CTC payments did not

have notable effects on missed difficulty with expenses or missed rent/mortgage payments.

Sensitivity Tests

A potential threat to our analysis is the effect of seasonality on differential hardship and

wellbeing outcomes for households with children relative to childless households. For example,

general conditions in July, such as summer vacation for many school-age children, may shape

hardship in a way that affects our conclusions. Our read of the evidence suggests that this would

bias away from our findings of reduced hardship: prior findings suggest that summer vacations

23

tend to worsen food hardship for households with children, given the absence of school meals

(Huang, Barnidge, and Kim, 2015). Nonetheless, to test for the effects of seasonality and to add a

placebo test to our analysis, we replicate our results using the same months (April through early

August) but using the 2020 version of the Pulse. We designate July 15, 2020, as the timing of our

treatment and otherwise apply the same treatment specifications as in our primary analysis. The

results, presented in Appendix D, show insignificant effects of either treatment for families of

any income level (Figure D1) and for families of any race and ethnicity (Figure D2). These

findings rule out that seasonality is driving our findings and strengthen the likelihood that the

expanded CTC is, indeed, responsible for the improved economic conditions of households with

children after July 15, 2021.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

The transformation of the Child Tax Credit into a more generous and inclusive monthly

payment marks a historic, albeit temporary, shift in the treatment of low-income families with

children within the U.S. welfare state. To identify the early impacts of the monthly payments on

material hardship, this study applied a series of difference-in-differences estimates using microdata

from the Census Household Pulse Survey (Pulse). The findings represent only the initial effects of

the first two CTC payments; thus, they should not be interpreted as the final effects of the CTC,

particularly given that coverage of the program will likely expand in subsequent months.

Nonetheless, our findings from the initial payments lead to three primary conclusions.

First, we find that the initial CTC payments strongly reduced food insufficiency among

low-income families with children. Specifically, we found that the initial CTC payments are

associated with a 7.5 percentage point (25 percent) decline in food insufficiency. The effect size

increases to 14 percentage points (around 50 percent) when evaluating the effect of the CTC on

24

the families who report receiving the payments. Estimates from our treatment intensity indicator

suggest that a $100 increase in size-adjusted CTC benefits is associated with a 6-percentage point,

or roughly 22 percent, decline in food insufficiency among families receiving the benefit. These

changes mark substantial declines in food hardship. As a result, the share of all low-income

families with children (regardless of whether they received the first CTC payments) experiencing

food insufficiency dropped from 29.8 percent just before the first CTC payment to 20.8 percent

after the first payments. For all households with children (regardless of income), the rate of food

insufficiency fell from 13.4 percent to 9.4 percent. The first CTC payments did not appear to

reduce the share of families who missed a rent or mortgage payment. This is perhaps unsurprising:

rent arrears make up a much larger sum than the typical monthly CTC payment (Aurand and

Threet, 2021), and most families receiving the CTC payment report spending the benefits on food

items (Perez-Lopez, 2021).

Second, we find the effects of the CTC on food insufficiency are concentrated among

families with 2019 pre-tax incomes below $35,000; perhaps unsurprisingly, the first payments had

little effect on food insufficiency among higher-income groups, as these income groups are less

likely to face hardship in the first place. Moreover, the effects on food insufficiency are broadly

consistent across low-income White, Black, and Hispanic families with children.

We also find that increasing the coverage rate of the CTC would be necessary for material

hardship to be further reduced. Though the Department of Treasury reports that around 83 percent

of children in the U.S. received the second CTC payment, self-reported receipt from the Pulse is

closer to two-thirds of all children (U.S. Department of Treasury, 2021a). Notably, the lowest-

income families in the Pulse (those reporting 2019 pre-tax incomes of under $25,000) report the

lowest receipt rate of the CTC. This aligns with concerns that children in households who have not

25

filed recent federal taxes – including those in families with very low incomes, disconnected from

work or public supports, and/or other challenges – are at greatest risk of missing out on the initial

rounds of monthly payments (Cox et al., 2021). We acknowledge, however, that the number of

children reached by the monthly payments is likely to increase with time. Consider that between

July and August 2021, the number of children receiving the CTC increased by 1.6 million (US

Department of Treasury, 2021b).

Given the likelihood of rising coverage rates in the future, we anticipate that the results in

the present analysis provide only a preview of the potential consequences of the CTC expansion.

As more children receive the benefit in future months, food hardship, and perhaps other forms of

material hardship, may decline further. From the present analysis, we nonetheless conclude that

the first payments of the CTC were largely effective at reducing food insufficiency among low-

income families with children.

26

References

Acs, G., & Werner, K. (2021). How a Permanent Expansion of the Child Tax Credit Could Affect

Poverty. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Available from

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-permanent-expansion-child-tax-credit-could-

affect-poverty.

Aurand, A., & Threet, D. (2021). The Road Ahead for Low Income Renters. Washington DC: National

Low Income Housing Coalition. Available from

https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/The-Road-

Ahead-for-Low-Income-Renters.pdf.

Bauer, L., Pitts, A., Ruffini, K., Schanzenbach, D.W. (2020). The effect of Pandemic EBT on measures of

food hardship. Brookings Institution. Available from:

https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-

effect-of-pandemic-ebt-on-measures-of-food-hardship.

Bauer, L., Schanzenbach, D.W., & Shambaugh, J. (2018). Work Requirements and Safety Net Programs.

Washington DC: The Hamilton Project, Brookings. Available from

https://www.brookings.edu/research/work-requirements-and-safety-net-programs/

.

Bitler, M., Hoynes, H. W., & Schanzenbach, D. W. (2020). The social safety net in the wake of COVID-

19 (No. w27796). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. (1997). The Effects of Poverty on Children. The Future of Children,

7(2):55-71.

Cai, C., Woolhandler, S., Himmelstein, D. U., & Gaffney, A. (2021). Trends in Anxiety and Depression

Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the US Census Bureau’s Household

Pulse Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(6), 1841-1843.

Center on Poverty and Social Policy. (2021). A Poverty Reduction Analysis of the American Family Act.

Poverty and Social Policy Fact Sheet. New York: Columbia University.

Chaudry, A., & Wimer, C. (2016). Poverty is Not Just an Indicator: The Relationship Between Income,

Poverty,and Child Well-Being. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3):S23-S29.

Collyer, S., Harris, D., & Wimer, C (2019). Left Behind: The One-Third of Children in Families Who

Earn Too Little to Get the Full Child Tax Credit. Poverty & Social Policy Brief, 3(6). New York:

Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Cox, K., Caines, R., Sherman, A., & Rosenbaum, D. (2021). State and Local Child Tax Credit Outreach

Needed to Help Lift Hardest-to-Reach Children Out of Poverty. Washington DC: Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities.

Crandall-Hollick, M.L. (2021). The Child Tax Credit: Proposed Expansion in the American

Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; H.R. 1319). CRS Report IN11613. Washington DC:

Congressional Research Service.

Crandall-Hollick, M.L. (2018). The Child Tax Credit: Current Law. CRS Report R41873.

Washington DC: Congressional Research Service.

27

Curran, M.A. (2015). Catching Up on the Cost of Raising Children: Creating an American Child

Allowance. Big Ideas: Pioneering Change, Innovative Ideas for Children and Families.

Washington DC: First Focus.

Curran, M.A., & Collyer, S. (2020). Children Left Behind in Larger Families: The Uneven Receipt of the

Federal Child Tax Credit by Children’s Family Size. Poverty & Social Policy Brief 4(4). New

York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Duncan, G., Morris, P.A., & Rodrigues, C. (2011). Does Money Really Matter? Estimating Impacts of

Family Income on Young Children’s Achievement With Data From Random-Assignment

Experiments. Dev Psychol, 47(5):1263-1279.

Garfinkel, I., Sariscsany, L., Ananat, E., Collyer, S., & Wimer, C. (2021). The Costs and Benefits of a Child

Allowance. Poverty and Social Policy Discussion Paper (Feb.). New York: Columbia University

Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Garfinkel, I., Harris, D., Waldfogel, J., & Wimer, C. (2016). Doing More for Our Children: Modeling a

Universal Child Allowance or More Generous Child Tax Credit. New York: The Century

Foundation.

Goldin, J., & Michelmore, K. (2020). Who Benefits From the Child Tax Credit? NBER Working Paper

27940. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available from

https://www.nber.org/papers/w27940

.

Hoynes, H. (2019). The earned income tax credit. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and

Social Science, 686(1): 180-203.

Huang, J., Barnidge, E., & Kim, Y. (2015). Children Receiving Free or Reduced-Price School Lunch

Have Higher Food Insufficiency Rates in Summer. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(9):2161–2168,

https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.214486

Marr, C., Cox, K., Hingtgen, S., & Windham, K. (2021). Congress Should Adopt American Families

Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions

Permanent. Washington DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Available from

https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/congress-should-adopt-american-families-

planspermanent-expansions-of-child.

Morales, D. X., Morales, S. A., & Beltran, T. F. (2020). Racial/ethnic disparities in household food

insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative study. Journal of Racial

and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1-15.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS). (2019). A Roadmap to Reducing

Child Poverty. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

Pac, J., Nam, J., Waldfogel, J., & Wimer, C. (2017). Young child poverty in the United States: Analyzing

trends in poverty and the role of anti-poverty programs using the Supplemental Poverty Measure.

Child Youth Serv Rev, 74:35-49.

Parolin, Z., Collyer, S., Curran, M.A., & Wimer, C. (2021a). The Potential Poverty Reduction Effect of

the American Rescue Plan. New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

28

Available from

www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-

internal/2021/presidentialpolicy/bideneconomic-relief-proposal-poverty-impact.

Parolin, Z. Collyer, S., Curran, M.A., & Wimer, C. (2021b). Monthly Poverty Rates among Children after

the Expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Poverty & Social Policy Brief 5(4). New York: Columbia

University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Perez-Lopez, Daniel. (2021). “Economic Hardship Declined in Households With Children as Child Tax

Credit Payments Arrived.” U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed at

https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/economic-hardship-declined-in-households-with-

children-as-child-tax-credit-payments-arrived.html in August 2021.

Schanzenbach, D., & Pitts, A. (2020). Food insecurity in the census household Pulse survey data tables.

Institute for Policy Research, 1-15.

Shaefer, H. L., & Edin, K. (2013). Rising Extreme Poverty in the United States and the Response of

Federal Means-Tested Transfer Programs. Social Service Review, 87(2):250-268.

Shaefer, H.L., Collyer, C., Duncan, G., Edin, K., Garfinkel, I., Harris, D., Smeeding, T.M., Waldfogel, J.,

Wimer, C., Yoshikawa, H. (2018). A Universal Child Allowance: A Plan to Reduce Poverty and

Income Instability Among Children in the United States. RSF: The Russell Sage Journal of the

Social Sciences, 4(2):22-42.

Twenge, J. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). US Census Bureau‐assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive

symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic. Depression and anxiety, 37(10),

954-956.

U.S. Department of Treasury. (2021a). “Treasury and IRS Announce Families of Nearly 60 Million

Children Receive $15 Billion in First Payments of Expanded and Newly Advanceable Child Tax

Credit.” Accessed at

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/Treasury-and-IRS-Announce-

Families-of-Nearly-60-Million-Children-Receive-%2415-Billion-Dollars-in-First-Payments-of-

Expanded-and-Newly-Advanceable-Child-Tax-Credit in August 2021.

U.S. Deptartment of Treasury. (2021b). Treasury and IRS Disburse Second Month of Advance Child Tax

Credit Payments (Press Release). Washington DC. Available from

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0322

.

Wheaton, L., Minton, S., Giannarelli, L., & Dwyer, K. (2021). 2021 Poverty Projections: Assessing Four

American Rescue Plan Policies. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Available from

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/2021-poverty-projections-assessing-four-american-

rescue-plan-policies.

Wimer, C., & Wolf, S. (2020). Family Income and Young Children’s Development. Future of Children,

30(2):191-211.

Ziliak, J. P. (2021). Food hardship during the COVID‐19 pandemic and Great Recession. Applied

Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 132-152.