University of North Dakota University of North Dakota

UND Scholarly Commons UND Scholarly Commons

Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects

January 2021

An Exploration Of Sexual Consent, Sexual Non-Consent, And An Exploration Of Sexual Consent, Sexual Non-Consent, And

Nonverbal Sexual Consent Communication Behaviors, Amongst Nonverbal Sexual Consent Communication Behaviors, Amongst

Community Stakeholders. Community Stakeholders.

Brent Stewart

How does access to this work bene;t you? Let us know!

Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Stewart, Brent, "An Exploration Of Sexual Consent, Sexual Non-Consent, And Nonverbal Sexual Consent

Communication Behaviors, Amongst Community Stakeholders." (2021).

Theses and Dissertations

. 4104.

https://commons.und.edu/theses/4104

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at

UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized

administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact und.commons@library.und.edu.

An Exploration of Sexual Consent, Sexual Non-Consent, and Nonverbal Sexual Consent

Communication Behaviors, amongst Community Stakeholders.

by

Brent Stewart

Bachelor of Arts, University of Washington, 2011

Master of Arts, University of North Dakota, 2018

A Dissertation

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty

of the

University of North Dakota

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Grand Forks, North Dakota

August, 2021

ii

Name: Brent A Stewart

This document, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

degree from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory

Committee under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved.

__________________________

__________

Kara Wettersten Ph.D.

__________________________

__________

Tamba-Kuii Bailey Ph.D.

__________________________

__________

Rae Ann Anderson Ph.D.

__________________________

__________

Cheryl Hunter Ph.D.

This document is being submitted by the appointed advisory committee as

having met all the requirements of the School of Graduate Studies at the University of

North Dakota and is hereby approved.

____________________________________

Chris Nelson

Dean of the School of Graduate Studies

7/26/2021

iii

PERMISSION

Title An Exploration of Sexual Consent, Sexual Non-Consent, and Nonverbal Sexual

Consent Communication Behaviors, amongst Community Stakeholders.

Department Counseling Psychology and Community Services

Degree Doctor of Philosophy

In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirement for a

graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree the library of this University shall

make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying or

scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my dissertation work or, in

her absence, by the Chairperson of the department or the Dean of the School of Graduate

Studies. It is understood that any copying or publication or other use of this dissertation or part

thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also

understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of North Dakota in

any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my dissertation.

Brent Stewart

May 3

rd

, 2021

iv

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 9

Script Theory and Sexual Consent ................................................................................ 12

Sexual Consent.............................................................................................................. 14

Sexual Non-Consent ..................................................................................................... 17

Consent and Violence Prevention ................................................................................. 18

Nonverbal Consent........................................................................................................ 20

Consent Practices in Underrepresented Communities .................................................. 23

Delphi ............................................................................................................................ 25

Purpose of the Study ..................................................................................................... 26

METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 28

Participants .................................................................................................................... 28

Procedure ...................................................................................................................... 33

Data Analysis ................................................................................................................ 36

Data Analysis Round One ............................................................................................. 37

Data Analysis Round Two ............................................................................................ 37

Data Analysis Round Three .......................................................................................... 38

RESULTS ......................................................................................................................... 40

Sexual Consent Results ................................................................................................. 40

Sexual Non-Consent Results......................................................................................... 44

v

Nonverbal Sexual Consent Communication Behaviors Results ................................... 66

DISCUSSION ................................................................................................................... 77

Sexual Consent.............................................................................................................. 77

Sexual Non-Consent ..................................................................................................... 82

Nonverbal Sexual Consent Communication Behaviors ................................................ 85

Strengths and Limitations ............................................................................................. 88

Implications for Violence Prevention and Practice ...................................................... 89

Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 91

References ......................................................................................................................... 93

vi

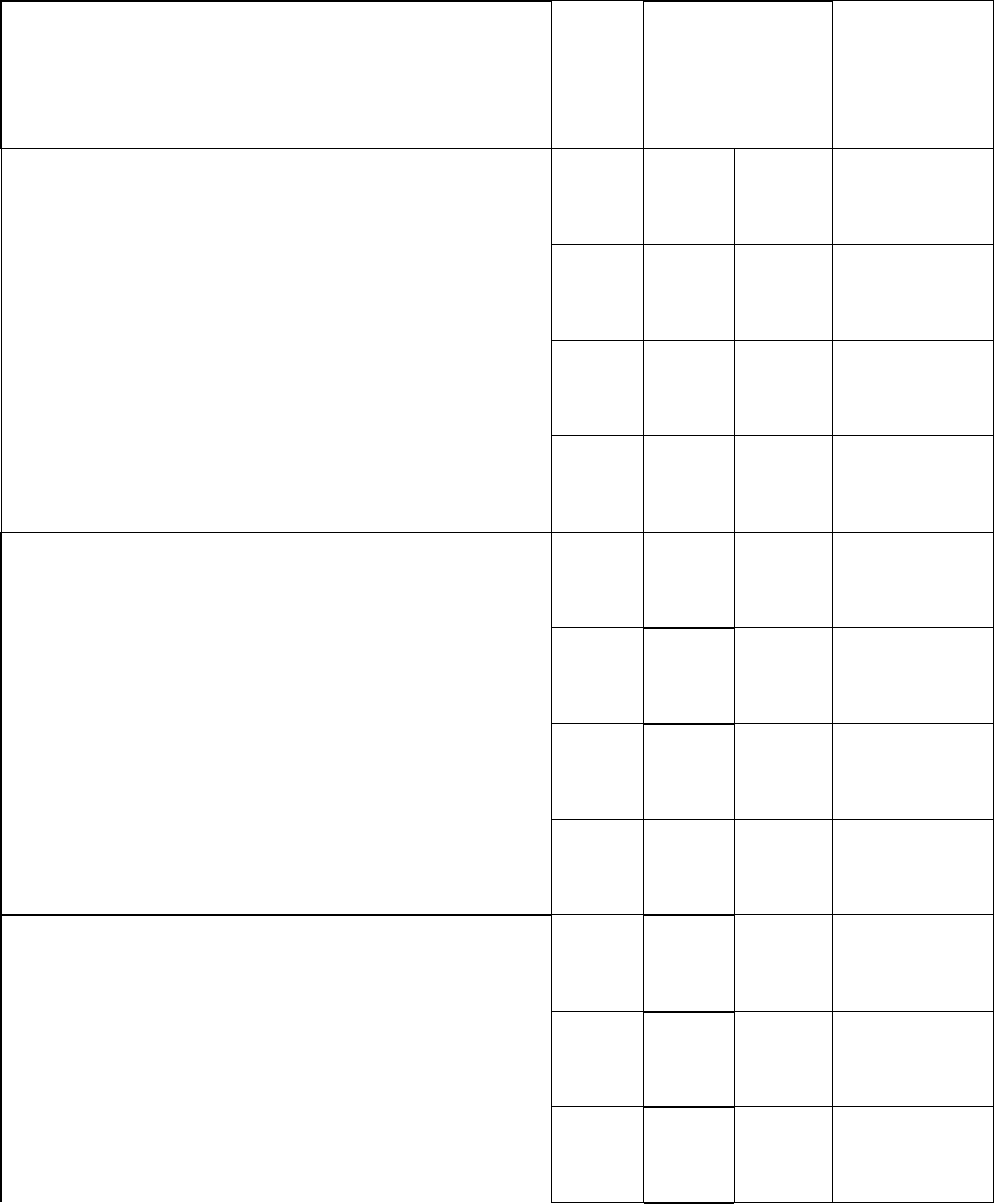

List of Tables

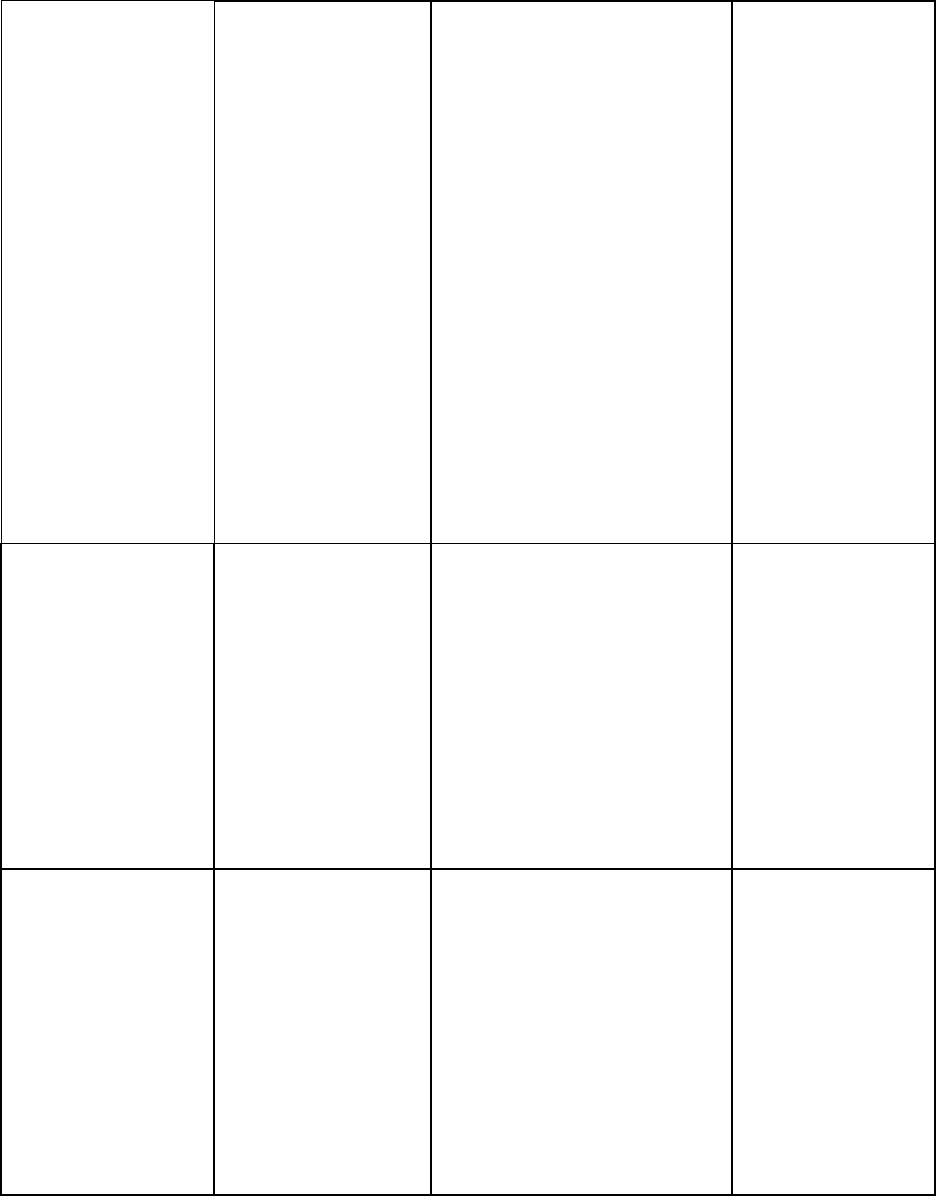

Table 1 Delphi Rounds 1,2,3, Panelist Demographics

........................................................................................................................................... 30

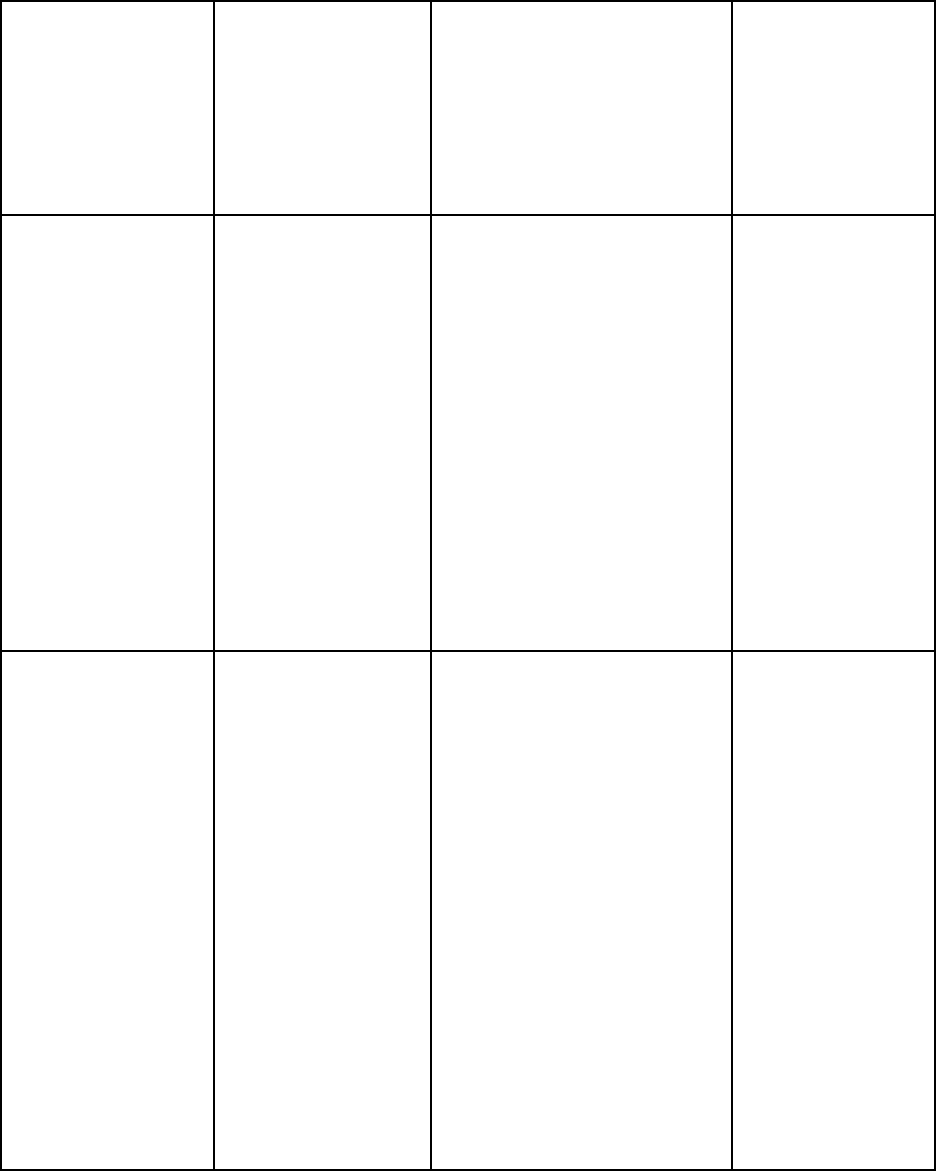

Table 2 Round 2, Level of Agreement to Descriptions of Consent 1(This does not adequately

describe consent) to 5 (This very much describes consent) with Mean, Standard Deviation, and

Variance

.......................................................................................................................................... 43

Table 3 Round 2, Task 1, Qualitative Feedback to participants descriptions of Sexual Consent

........................................................................................................................................... 17

Table 4 Round 2, Sexual Consent Qualities Rank Order Position

........................................................................................................................................... 33

Table 5 Round 3, Sexual Consent Qualities Rank Order Position

........................................................................................................................................... 36

Table 6 Sexual Consent Qualities First Rank Order Position Comparison between Round Two

Ranking and Round Three Ranking,

........................................................................................................................................... 39

Table 7 Sexual Consent Qualities Sixth Rank Order Position Comparison between Round Two

Ranking and Round Three Ranking,

vii

........................................................................................................................................... 42

Table 8 Round 3, Task 1, Level of Agreement to Descriptions of Sexual non -consent 1(Strongly

Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree) with Mean, Standard Deviation, and Variance ............ 48

Table 9 Round 3, Task 1 Qualitative Feedback to participants descriptions

.......................................................................................................................................... 56

Table 10 Elements of Sexual Non-Consent Rank Order Position Round 3

........................................................................................................................................... 64

Table 11 Round One, Qualitative descriptions of missing nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors.

........................................................................................................................................... 67

Table 12 Round Three, Nonverbal Sexual Consent Communication Behavior Usage

........................................................................................................................................... 70

viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is a result of a labor of love and is a testament to the support and unwavering faith of

the community which surrounded me as its’ author during the height of the dual pandemics of

COVID-19 and Racism. I would like to take a moment to acknowledge my parents (Brent and

Monica Stewart) for their faith, my grandmother (Margaret Hill) for her optimism, and my

siblings (Paula, Desmond, and Monique) for their cheers during this process. Additionally, I

would like to thank my midwestern family (Candice Farnham and the Motors) and my chosen

family in Seattle Washington (Peter Englund, Oliver Jones, Lauren Menor, Adam Panebianco,

Sam McQueen, Kate Gruver, Max Gray, Larissa Miller, Dr. Caroline Titan, Andrea Cerna, Jay

Miller). Next, I would like to acknowledge the deep support from my adviser (Dr. Kara

Wettersten), the UND faculty (including Drs. Tamba-Kuii Bailey; RaeAnn Anderson, Thomas

Motl, Ashley Hutchison and Cheryl Hunter) and the UND Housing Department (especially

Stuart Lickteig) all of whom helped make my dream of becoming a psychologist a reality.

Lastly, I would like to thank my colleagues Drs. Marisa Mango, Megan K. Smith, Natalie

Remanier, and Lauren Chapple-Love with whom I have the honor of sharing this journey with

and also share the privilege of calling UND their alma mater.

ix

ABSTRACT

Sexual Consent is a central concept in the field sexual violence and sexual violence

prevention (Beres, 2007). However, despite disproportional rates of sexual violence amongst

LGBT+ community, currently our understanding sexual consent and its practice is primarily

focused on heterosexual encounters of traditional college aged students (CDC, 2017,

Muehlenhard, Humphreys, Jozkowski & Peterson, 2016). The current study utilized the Delphi

method to develop a better understanding of sexual consent, sexual non-consent, and nonverbal

sexual consent communication behaviors among two distinct groups: sexual researchers and men

who have sex with men (MSM). Thirty-five panelists (13 researchers 22 MSM) completed one-

three rounds of an interactive study in which they provided 31 initial descriptions of sexual

consent and 20 descriptions of sexual non-consent. Through grounded theory analysis, these

descriptions were collapsed into 6 qualities of sexual consent and 5 elements of sexual non-

consent and ranked for importance. Panelists reviewed, critiqued, and sorted Beres et al. (2007)’s

list of nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors. Implications of the perception of

these behaviors and implications for future research and practice are discussed.

ix

INTRODUCTION

In 2011, the nation focused its attention on sexual assault. Specifically, the Title IX Act

drew attention to sexual assault on college campuses through (Ali, 2011). The origins of title IX

stem from looking at equity amongst genders in terms of sports, but the Obama administration

was broadened to look at issues of identity-based harassment and sexual assault. This formal

adoption of sexual violence prevention as a governmental priority has provided a platform for

activists and advocates to bring sexual violence prevention to the forefront of the lives of many

Americans. This platform has included on campus trainings, documentary films regarding sexual

violence on college campuses, and most recently the #metoo movement (Airey, 2018;

Muehlenhard, Humphreys, Jozkowski, & Peterson, 2016).

Researchers of sexual violence have defined sexual violence broadly as “sexual contact

achieved without consent” (Beres, 2007; Halley, 2016, p. 262). Thus, the definition of sexual

violence depends heavily on the definition and conceptualization of sexual consent and how it is

communicated. Unfortunately, there is limited research on what constitutes sexual consent, and

an overall lack of consensus on what exactly sexual consent is or how it is communicated

between parties (Beres, 2007; Beres, 2014; Muehlenhard et al., 2016; Pugh & Becker, 2018).

Furthermore, when examining sexual consent, current research on consent and its

communications practices are centered around the experiences of white, heterosexual, cisgender,

individuals with varying levels of experience in sexual interactions (Beres et al., 2004;

Jozkowski, et al., 2014; Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010; Humphreys & Herold, 2007; Ward et

10

al., 2012). Thus, when considering sexual consent and its practice, and its relation to sexual

violence prevention it is paramount we broaden the scope of our understanding. This is

especially relevant given the documented disparities regarding the experience of sexual violence

within sexual minority and gender minority communities such as men who have sex with men

(MSM; Kosciw et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2018).

Further complicating this picture is the way we conceptualize the communication of

sexual consent between parties. Amongst sexual researchers, sexual consent communication has

been depicted with two clear sets of behaviors utilized by partners to convey and seek sexual

consent; verbal and nonverbal behaviors (Beres et al. 2004; Jozkowski et al., 2014). Verbal

behaviors largely fall within the realm of verbal communication and can include direct

communication, indirect communication, and “dirty talk” (Beres, et al. 2004; Hall, 1998;

Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999; Jozkowski, et al. 2014). Broadly, nonverbal behaviors have

been labeled as “body language” and is considered to include behaviors such as hugging, kissing,

massaging, undressing, eyeing, self-stimulation of genitals, stimulation of partners’ genitals, and

non-resistance to sexual advances (Beres et al., 2004; Camilleri, et al., 2007). While both verbal

and nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors are depicted across multiple studies,

current literature has depicted a clear preference amongst subjects for using nonverbal behaviors

rather than utilizing verbal communication behaviors (Beres et al., 2004; Hall, 1998; Humphreys,

2007; Jozkowski, et al., 2013 King, et al. 2020). Given this preference, it is important to consider

the impact these nonverbal communication behaviors have on the expression of sexual consent

especially within models of violence prevention such as affirmative consent.

11

Thus, it is scope of the current project to examine sexual consent communication

behaviors, specifically to examine the use of nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors

amongst underrepresented populations in current literature. Utilizing the consensus-oriented

Delphi research methodology (Linstone & Turoff, 1975), the current study seeks to compare the

perceptions of sexual consent and sexual consent communication behaviors between sexual

researchers of any gender or sexual identity (SR) and men who have sex with men community

members (MSM). Specifically, the current study seeks to better understand how these two

groups conceptualize sexual consent, sexual non-consent, and nonverbal communication

behaviors of sexual consent.

Lastly, as part of this work, it is important to acknowledge the role that sexual consent,

most importantly the lack of sexual consent, plays in sexual violence. Within the scope of the

current study, it is the aim of the researcher to better understand nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors and their utilization within the process of sexual consent

communication. The current study is not designed to definitively define sexual consent, sexual

non-consent, or advocate for the replacement of verbal sexual consent communication behaviors

with nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors. Rather, the current study seeks to build

a fuller picture of the sexual consent communication process specifically the use and

understanding of nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors. Furthermore, because of

its intimate connections with sexual violence, it is also paramount to note the current study of

sexual consent communication behaviors is not designed to account for mal intent to cause harm.

Rather, this study seeks to create a fuller picture of sexual consent communication practices and

12

aide in the creation of even more effective sexual violence interventions and consent

communication practices that reflect the diversity of practices currently in use.

Script Theory and Sexual Consent

When discussing the concept of sexual consent and sexual consent communication

behaviors, it is important to acknowledge the role of cultural expectations and the perception of

“norms” in the communication process. Script Theory is an academic paradigm employed in the

fields of sociology and cognitive psychology as an explanation for human behavior (McCormick,

1987; Simon and Gagnon, 1986; Schank & Abelson 1977). Within the field of cognitive and

social psychology, script theory is considered analogous to computer programming and places an

emphasis on prior learning dictating future outcomes for an individual’s behavior (McCormick,

1987). In contrast, within sociology, scripts are a set of flexible guidelines, with larger cultural

messages (cultural beliefs) influencing an individuals’ actions (interpersonal scripts) and beliefs

about their actions (intrapsychic scripts; Simon & Gagnon, 2003; McCormick, 1987).

First appearing in the early 1970’s, Sexual Script Theory (SXST) was developed as

response to and rejection of the bio-medical and psychological explanations for sexual behavior

and sought to include contextual factors impact on sexual behavior (Gagnon & Simon, 2003).

Sexual script theory rests on the sociological notion of scripting, where sexually active

individuals have beliefs about the range of behaviors, they can engage in sexually based on

preceding behaviors of their partners (Fantasia, 2011; Rose & Frieze, 1989). Within the SXST

lens, widespread beliefs (i.e., cultural scenarios) around sexuality affect an individual’s actions

(i.e., interpersonal script) and more importantly their fantasies, beliefs, and internal experience

around their sexuality and sexual interactions (i.e., intrapsychic beliefs, Simon & Gagnon. 1986;

13

Widerman, 2015). Contextual factors such as race, age, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation,

have all been shown to affect sexual behavior, suggesting nuance and flexibility regarding sexual

scripts is important (Dworkin & O’Sullivan, 2005; Parsons et al., 2012; Simms & Byers, 2013).

In the context of sexual consent research, this framework is used often to explore and

explain behaviors of sexually active individuals. For instance, several studies have examined the

cultural belief of ‘men must initiate sexual activity’ and found that this belief impacts

individuals’ sexual initiation behaviors despite their personal preference or personal beliefs

(Dworkin & O’Sullivan 2005; Hirsch et al., 2019; Jozkowski & Peterson 2013; Jozkowski,

2015). Such findings are used to legitimize a key point of SXST: cultural beliefs affect one’s

sexual behavior (interpersonal scripts) and can override personal desires or beliefs when it comes

to sex practices (intrapsychic scripts). Additional research has gone on to explore and validate

the notion of a gendered (male and female) experience of intrapsychic scripts and subsequent

sexual practices and beliefs (Rosenthal et al., 1998; Ortiz Torres et al. 2003; Peplau 2003).

When considering sexual consent miscommunication violence prevention, SXST and the

notion of gendered intrapsychic scripts have large implications for best practice. For instance,

research into sexual violence prevention, sexual consent communication, and sexual consent

often cite the cultural belief women are expected to act as “gatekeepers” and men as “pleasure

seekers” framing their interactions in relatively set roles (Hirsch et al., 2019; Jozkowski, 2013;

2015; Peplau 2003). However, rather than viewing these as rigid internalized roles, much

research into sexual consent and sexual consent communication notes variation in intrapsychic

scripts of individuals based on gender identity, age, relationship status, race, and sexual interest

[e.g., kink] community membership (Beres & McDonald, 2016; Simms & Byers, 2013).

14

Furthermore, even within the narrow scope of heterosexual interactions, several studies provide

evidence to suggest limitations of generalizability SXST when considering the lived experience

of sexual behaviors and sexual consent communication behaviors of all sexually active people

(Beckmann, 2003; Dworkin & O’Sullivan, 2005; Beres & McDonald, 2016; Simms & Byers,

2013)

Within MSM population, variations in sexual script are apparent and may include the

behaviors of consensual non-monogamy, substance use in during sexual initiation, and sexual

involvement on the first date (Candelas de la Ossa, 2016; Edgar & Fitzpatrick, 1993; Javaid,

2018; Klinkenberg & Rose 1994; Parsons, Starks, Gamarel, & Grov, 2012). Furthermore, when

considering how these script differences may play out in the role of sexual consent

communication, researchers specifically looking into same sex partners note when responding

sexual initiation behaviors MSM report a higher use of nonverbal sexual consent communication

behaviors to indicate their consent when compared to women who have sex with women (WSW;

Beres et al., 2004, Peplau 2003). Additionally, amongst MSM couples, male intrapsychic scripts

(e.g., pleasure-driven scripts) appear to affect the interpersonal scripts and scenarios of MSM

community members regarding sexual and romantic behavior (Parsons, Starks, Gamarel, Grov,

2012). Thus, when thinking about sexual consent and sexual consent communication behaviors

in the MSM community, it is important to understand how cultural scenarios, interpersonal

scripts, and intrapsychic scripts interact in a dynamic fashion to affect consent behavior

communication practices amongst members of this group.

Sexual Consent

15

Further complicating our understanding of sexual consent communication behaviors and

their practice is that there is no clear agreed upon definition of sexual consent (Beres, 2014;

Muehlenhard et al., 2016; Pugh & Becker, 2018). Beres (2007) has put forth that current

literature often engages in “spontaneous consent” a process where definitions of sexual consent

are not established by the author, but rather it is assumed the reader shares a common

understanding of consent. Beres then goes on to make the case that, despite its’ central role in

our understanding of sexual violence, within the literature, sexual consent is not defined,

inadequately defined, or defined in ways contradictory to previous definitions (Beres, 2007).

Additionally, while a singular definition of sexual consent and its meaning remains opaque,

equally important is a lack of clarity around the concept of sexual non-consent. Within the scope

of literature some have defined sexual consent as merely the “absence of consent” (Halley,

2016). Within this context, defining sexual consent merely as the absence of consent, engenders

the question of what sexual non-consent and the role sexual non-consent and the communication

of non-consent is plays in our understanding of sexual violence prevention. Muehlenhard et al.’s

(2016) meta-analysis of empirical research on sexual consent notes three main

conceptualizations: sexual consent as an internal state of willingness, sexual consent as an act of

explicitly agreeing to something, and sexual consent as behavior that some else interprets as

willingness.

When considering sexual situations, each of the three conceptualizations put forth by

Muehlenhard et al. (2016) boast strengths and weaknesses as potential basis for the definition of

sexual consent, sexual consent communication behaviors, and the prevention of sexual

miscommunication. For instance, when considering sexual consent as an internal state

16

willingness, this definition notes that sexual consent cannot be objectively defined by solely one

member of the interaction. Therefore, under this premise, sexual consent must clearly involve

both the internal agreement and willingness of one member to do something and the enacting of

behaviors to express that willingness to others successfully (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999;

Muehlenhard et al., 2016). Sexual consent as an internal state of willingness places large

emphasis on individual party members demonstrating correct behaviors to communicate their

willingness to engage in sexual activity. This places emphasis on communication behaviors and

lends itself to popular theories of sexual violence and unwanted experiences (at least in some

cases) being due in part to miscommunication of sexual consent (Abbey, 1982, 1987; Fantasia,

2011).

The second broad understanding of sexual consent is an act of explicitly agreeing to

something (Muehlenhard et al. 2016). In sexual situations, this model of sexual consent involves

an explicit verbal agreement between an initiator and respondent to engage in sexual activity.

This perspective of sexual consent most closely aligns with aspirational notions of sexual

consent which seek to have sexual consent explicitly communicated such as affirmative consent

(de La Ossa, 2016; Soble, 2002). As a model of sexual consent, the explicit nature of agreement

employed by these conceptualizations are preferred as they speak to the notion that a lack of

sexual consent (i.e., sexual assault) occurs due to a lack of clear verbal communication between

parties resulting in a miscommunication (Abbey, 1982, 1987; de La Ossa, 2016; Fantasia, 2011).

However, several research findings suggest limitations of conceptualizing sexual consent in this

way, which include the well-documented fact that verbal sexual consent communication

behaviors during sexual consent negotiation is less common than nonverbal sexual consent

17

communication behaviors (Beres et al. 2004; Hall, 1998; Humphreys, 2007; Jozkowski et al.,

2013). Additionally, some have postulated due to the inherent nature of some sexual

relationships (especially heterosexual interactions) that women especially should be able to

convey non-consent with a multitude of means outside of simply saying “no” (Kitzinger & Frith,

1999).

The third and final grouping of sexual consent definitions reviewed by Muehlenhard et al.

(2016) is considering sexual consent as a behavior that someone else interprets as willingness.

When considering sexual consent in this way, the legal notion of “implied consent” is most

applicable to this group. Implied consent suggests that consent is given via a sign or action that

creates a reasonable presumption of acquiescence (Block, 2004). In the context of sexual consent

communication, implied consent relies heavily on the notion of a shared sexual script in which

both actors are familiar with and well-rehearsed in said script. There are several limitations

conceptualizing sexual consent in this way, including the fact subscription to cultural beliefs

(i.e., Cultural scenarios) regarding sexual initiation behaviors and actual sexual behavior (i.e.

interpersonal scripts) can differ among individuals (Beres & McDonald, 2016; Dworkin, &

O'Sullivan, 2005; Simms & Byers, 2013). In summary all three conceptualizations of sexual

consent as outlined by Muehlenhard et al. (2016) provide a unique framework for understanding

sexual consent and thus helping inform policies around effective sexual violence prevention

practices. All three models of sexual consent underscore the importance of effective

communication between parties as being integral to the process of establishing sexual consent.

Sexual Non-Consent

18

When considering the impact of sexual violence on communities, and the role sexual

consent plays in defining instances of sexual violence, it also becomes integral to consider the

role of and our understanding of sexual non-consent. Analysis of sexual consent definitions in

literature have noted that much of the current literature merely refers to sexual violence as

intercourse with a of consent present or “sexual contact achieved without consent” (Beres, 2007;

Halley, p. 262, 2016). Similarly, within the US legal system, there is a long history of examining

the role of force, sexual consent, and sexual non-consent when considering the definition of the

crime of rape (Decker and Boaroni, 2011). Historically many states have included an unfair

burden on those who have experienced an unwanted sexual experience to “prove” an incident

was indeed non-consensual especially in the absence of overt force or violence (Decker and

Baroni 2011). This standard has been used in other crimes within the legal system, with the

presence of “force” being used to delineate between crimes involving similar offenses (e.g.,

larceny vs. robbery, manslaughter vs. murder; Peeler, 2021). However, when considering cases

and instances of sexual violence, intent of the perpetrator is generally outweighed by the impact

of experiences on survivors. Furthermore, as noted by many scholars, the complex nature of

sexual interactions and the “use of force” is not the only indication of an unwanted sexual

experience (Kitzinger & Frith, 1999; Pugh & Becker, 2018). Therefore, when exploring sexual

violence and it’s prevention, its also important for researchers and the public to better understand

the concept of sexual non-consent and the ways in which sexual non-consent is communicated

between parties.

Consent and Violence Prevention

19

As noted above, sexual consent and the communication of sexual consent are important

components of sexual violence prevention. Thus, a large goal of violence prevention programing

is addressing the notion known as implied consent and miscommunications that may result of

that implication. To correct for the ambiguity and miscommunication associated with implied

consent, much attention has been focused on the adoption of laws and education programs that

focus on direct, clear, consistent, communication between parties as exemplified in the practice

of affirmative consent (Curtis & Burnett 2017; Jozkowski & Humphreys, 2014; De León, 2014).

The practice of affirmative consent, which focuses on training individuals to utilize direct,

consistent, and clear verbal communication during sexual activity in order to establish

enthusiastic participation by all parties, has become the primary means of teaching consent

practices--especially on college campuses (Antioch College, 2016; Ali, 2011; De León, 2014).

Affirmative consent is hallmarked by the seven key tenants in its practice which include:

1. Consent must be obtained verbally before there is any sexual contact or conduct.

2. Obtaining consent is an ongoing process in any sexual interaction.

3. If the level of sexual intimacy increases during an interaction… the people

involved need to express their clear verbal consent before moving to that new

level

4. The request for consent must be specific to each act.

5. If you had a particular level of sexual intimacy before with someone, you must

still ask each and every time.

20

6. If someone has initially consented but then stops consenting during a sexual

interaction, she/he should communicate withdrawal verbally and/or through

physical resistance. The other individual(s) must stop immediately.

7. Don’t ever make any assumptions about consent (p.327, Soble 2002).

However, several research findings suggest limitations of such an intervention. In

particular explicit verbal communication behaviors during sexual consent communication is less

common than nonverbal communication behaviors (Beres et al. 2004; Hall, 1998, Jozkowski et

al., 2013; King et al. 2020; Shumlich, & Fisher, 2018). Additionally, some factors such as the

length and duration of a relationship and gender identity of an individual, has been shown to

impact sexual consent communication practices, specifically use of and reliance on verbal

communication behaviors (Humphreys, 2007; Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013; King et. al, 2020;

Willis & Jozkowski, 2019). As outlined above in the seven key tenants, while affirmative

consent acknowledges the role of nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors it is

decidedly vague on what constitutes these behaviors, especially in comparison to its focus on

verbal sexual consent communication behaviors.

Nonverbal Consent

In addition to observed gender differences in communication behavior patterns, research

has shown that amongst sexual consent communication behaviors, nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors are more commonly utilized by all individuals when compared with

verbal communication behaviors (Beres et al. 2004; Hall, 1998; Humphreys, 2007; Jozkowski et

al., 2013). Additionally, despite adoptions by many college campuses, verbal sexual consent

communication behaviors outlined in affirmative consent models rarely reflect the lived

21

experience of students (Curtis & Burnett, 2017; Hall, 1998; Johnson & Hoover, 2015; Jozkowski

& Humphreys, 2014). For example, Curtis and Burnett (2017) found some participants indicated

little to no experience with affirmative consent as a verbal behavior. One female respondent

noted “…But when I come to think of it in the real-world perspective, I think if you’re going

along with the motions and you’re not showing resistance to it and you’re into it, then that’s

consent” (p. 209 Curtis & Burnett, 2017). This statement corroborates with research on sexual

consent communication behaviors amongst college students which notes preference by

participants in the use of non-resistance as a means conveying consent, and a tendency of some

males to continue with a sexual behavior until they encounter a verbal communication behavior

of non-consent (Beres et al., 2004; Camilleri, et al., 2007; Hall, 1998; Humphreys, 2007;

Jozkowski et al., 2013; King et al., 2020).

Many studies (mostly set amongst the college-aged population) have noted the use of and

preference for nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors, as a part of the sexual

consent practice (Curtis & Burnett, 2017; Hall, 1998; Humphreys, 2007; Jozkowski & Peterson,

2014; King et al. 2020; Kitzinger & Frith, 1999; McCormick, 1979; Shumlich, & Fisher, 2018).

Nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors such as smiling, nodding, accepting

alcoholic drinks, following a partner to their residence, and genital stimulation, have all been

evaluated to have a range of meanings when conveying sexual consent to partner (Beres et al.

2004, Humphreys & Herold, 2007; Jozkowski & Peterson, 2014; Orchowski et al. 2018).

Additionally, several studies have documented that gender differences in the perception of

communication behaviors of sexual consent exist in heterosexual interactions, with men utilizing

and watching for more nonverbal sexual communication behaviors (i.e., body language) and

22

women utilizing more verbal sexual communication behaviors (Abbey, 1982; Hickman &

Muehlenhard, 1999, Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013; King et. al, 2020; Peplau, 2003). In response

to critiques of the limitations of nonverbal sexual consent communication behavior studies

examining one behavior at a time, King et al. (2020) examined college students’ perceptions of

concurrent/ successive nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors. Again, results of this

study showed differences in the perception of nonverbal sexual consent communication

behaviors with male participants consistently interpreting successive nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors as more indicative of sexual consent then their female peers (King et

al., 2020).

As noted above, there is a significant portion of research which documents the existence

of nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors. These studies share common themes and

outcomes, including a clear preference for nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors

amongst participants and male participants utilizing nonverbal sexual consent communication

more ardently than their female counterparts (Beres et al. 2004; Curtis & Burnett, 2017).

Additionally, as many young adults lack access to standardized experiences with sexual

education and education centered sexual consent education, many learn concepts of sexual

consent communication from mainstream depictions of consent in films and pornography (Willis

et al., 2019; 2020). A 2019 study of sexual communication and refusal behaviors depiction in the

media, revealed through the analysis of fifty (50) 2013 films’ depictions of sexual consent

communication behaviors between partners were overwhelmingly nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors (Jozkowski et al., 2019). Furthermore, a content analysis of popular

pornographic films done by Willis et al. (2020), reveal similar depictions of nonverbal sexual

23

consent communication behaviors are utilized. Taken together, findings such as these suggest a

mechanism which may lead to the documented preference of college and high school youth

(especially male-identified youth) to rely on and utilize nonverbal sexual consent communication

behaviors (Righi et al. 2019; Nichols Curtis, 2017; King et al. 2020). When taken together, these

findings lend support to the notion of larger societal expectations (cultural scripts) impacting and

influencing individual behaviors (interpersonal scripts) and beliefs/ expectations (intrapsychic

scripts) around nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors.

Noting the support within the current literature for the existence, preference teaching, of

nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors- there remains a dearth in our understanding

of these consent communication behaviors. Overwhelmingly, current studies of sexual consent

and sexual consent communication behaviors have been conducted on cisgender, white,

heterosexual, traditionally college-aged students (Beres, 2007; Muehlenhard et al. 2016).

However, several studies have noted the impact of life experiences, especially length of a sexual

partnership and gender socialization, to impact perceptions of sexual consent and sexual consent

communication behaviors (Humphreys, 2007; Willis & Jozkowski, 2019). The concept of sexual

script theory and the heteronormative notion of men being pleasure seekers and women being

gatekeepers play out in many of these majority population studies (Jozkowski, 2017). Taken all

into context, it is important to consider the question of how gender-identity and sexual

orientation may interact and affect conceptions of sexual consent and subscription to and use of

nonverbal sexual consent communication behaviors.

Consent Practices in Underrepresented Communities

24

Overwhelmingly, the North American understanding of sexual consent and sexual

consent communication behaviors have been derived from the experiences of white, college-

educated, and often heterosexual participants (Beres et al., 2004; Jozkowski, et al., 2014;

Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010; Humphreys & Herold, 2007; Ward et al., 2012). This becomes

incredibly significant when we consider the ample documentation for gender specific patterns of

sexual consent communication behaviors, as well as the different patterns of sexual consent

communication behaviors observed specifically within sub-communities (e.g., MSM, S&M, and

WSM; Frankis & Flowers, 2009; Bullock, 2004;).

Specifically, within the MSM community, an historic emphasis by some members of this

community has been placed on nonverbal communication behaviors in order to avoid detection

and persecution by non-community members (Tewksbury, 1996). Historically MSM members

have engaged in nonverbal communication behaviors such as displaying and wearing specific

items of clothing and accessories, physical demonstrations (e.g., tapping of the foot beneath a

stall) and attending designated public spaces (e.g., parks, rest stops, public restrooms) during

designated hours as a means of conveying to other parties their community membership and

potential sexual interest (Tewksbury, 1996). This behavior among MSM community members

has been titled “cruising” and relies heavily on the use of nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors including eye contact, pursuit, display, and body contact (Frankis &

Flowers 2009).

As noted in literature on cruising, the specific set of nonverbal communication behaviors

employed in these areas by community members are designed to communicate sexual interest

and sexual consent to community members, but to hold no meaning for non-community

25

members. With this purpose in mind, nonverbal communication behaviors utilized in cruising are

an example of communication behaviors that differ from the overarching sexual script for non-

community members (ie. heterosexuals) as is described in much of the current sexual consent

communication research. More contemporarily, research has also been conducted into the use of

and understanding of “gaydar”, a mechanism by which community members employ a “sixth

sense” to assess and utilize nonverbal and verbal behaviors as a means of identifying potential

sexual community membership and potential sexual/romantic partners (Rule & Alaei, 2016).

Our understanding of sexual consent communication behaviors remains at the heart of

sexual miscommunication and thus some sexual violence prevention efforts. Therefore, it is

crucial to better understand sexual consent communication behaviors within non-majority

populations. For instance, when considering sexual violence within the MSM community,

literature notes a disproportionate experience of sexual violence within this population when

compared to their heterosexual peers (Association of American Universities, 2015; CDC, 2017;

Kosciwet al., 2016). Taken together, the disproportionate amount of violence and community

specific behaviors, underscores the need for a more complete understanding of sexual consent

communication behaviors and concepts of sexual consent within this community.

Delphi

The Delphi method is a multi-round approach to consensus building among experts in a

given field. Historically the Delphi has been termed as a means of refining a groups’ judgement

and has been a way of formalizing the power of group wisdom (Dalkey, 1969). The Delphi

methodology allows for individuals with diverse experiences and expertise to independently

share their knowledge and arrive at a consensus regarding a larger idea (Hasson, Keeney, &

26

McKenna, 2000; Hsu & Sandford, 2007). Additionally, the Delphi method has been successfully

utilized in mental health research regarding best practice and competency, as well as a means of

comparing the knowledge of experts (e.g., researchers, clinicians) and consumers (e.g.,

community stakeholders, patients; Forbes, Hutchison, 2020; Ross, Kelly, Jorm, 2015). As noted

in the exploration of affirmative sexual consent and sexual violence prevention efforts above,

there is a gap between academic best practice (verbal sexual consent communication behaviors)

and the lived experiences of community stake holders regarding their communication of sexual

consent (Curtis & Burnett, 2017). Thus, the Delphi methodology provides an ideal opportunity to

compare and arrive at a group consensus between both researchers and community members

regarding this important topic. Furthermore, considering the Covid-19 pandemic, the Delphi

methodology is an increasingly attractive means of conducting research due to its ability to

collect information and facilitate engagement amongst participants in a socially distant manner

(Khazie, Khan, 2020). Lastly, when working specifically within the sexual minority communities

such as the MSM community, several studies have documented the effectiveness of utilizing

online/ distance methods to engage with this population regarding sexual behaviors and practices

(Bowen, 2005; Ross et al. 2000).

Purpose of the Study

The current study seeks to expand our understanding of sexual consent and nonverbal

sexual consent communication behaviors. Specifically, the current study seeks to address a

dearth in the literature by examining these concepts within the context of two specific

communities--the MSM community and sexuality researchers--by utilizing the Delphi Method

(Dalkey, 1969). Due to the exploratory nature of this study and methodology, there are no

27

expected results or stated hypotheses for this study. Instead, we seek to determine if consensus

between our two groups can be reached on each of the following primary research questions:

1. What are the qualities of sexual consent?

2. What are the elements of sexual non-consent?

3. What are the behaviors associated with sexual consent communication?

4. What are the ways the group interprets and utilizes nonverbal sexual consent

communication behaviors?

28

METHODS

In this study, the Delphi method (Dalkey, 1969) was utilized in order to collect and

analyze data through a multifaceted approach. The Delphi method is a group facilitation method

that is performed in stages, with the ultimate goal being the expert panelists arriving at a

consensus opinion regarding the topic at hand (Jorm, 2015; Linstone & Turoff, 1975). The

current study sought to better understand conceptualizations and experience of panelists

regarding sexual consent and sexual consent communication behaviors.

Participants

In line with the establishment of a community-driven and community-consistent

conceptualization of sexual consent and the behaviors utilized in its communication, participants

for this study were recruited through a snowballing campaign. Eligibility for the current study

included participants identifying with one or more of the following criteria:

1. Identifying as a researcher of human sexuality, sexual violence, or sexual violence

prevention (of any gender identity or sexual orientation).

2. Identifying as a member of the MSM community, who acknowledges having a history of

a sexual experience with another male-identified person.

In addition to the above inclusionary criteria participants were also included based of their

willingness to participate in a multiple-round study, having adequate time and internet access, as

well as their ability to read and write effectively in the English language (Skulmoski et al.,

2007).

29

Our initial panel (Round One) consisted of a total of 35 unique participants who

completed the survey; a complete list of their demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Participants Round One ranged in age from 18 to 55, with a little over 50% of participants

identifying as members of the MSM community. Participants also presented with racial ethnic

diversity with 34% of participants identifying as a member of a racial or ethnic minority group

and 66% identifying as white. Similarly, participants in Round One also presented with various

relationship statuses with 66% indicating they were in a relationship and 34% indicating they

were single. Participants in Round one also presented with a long history of experiences in

higher education with 92% or participants indicating they were a college graduate or had post-

graduate training.

Proceeding to Round Two, 20 respondents completed the second-round survey making

up our panel in this round, a complete list of their demographic information can also be found in

Table 1. Despite some attrition, Round Two’s participants presented with similar representation

of diverse experiences and identities as seen in Round One. Despite attrition of 15 participants,

proportionally demographics of Round Two participants remained largely the same with a

majority of participants identifying as male, and as members of the MSM community.

In the final round, Round Three, a total of 18 participants completed the survey making

up our third-round panel. With an attrition of two, demographics between Round Two and

Round Three largely remain the same. Fifty-one percent of participants (n=18) completed all

three rounds of this Delphi study, the complete list of participants demographics can be found in

Table 1 . A majority of participants in all three rounds identified as MSM community members,

ranging in age (23-55). When compared to Round One, the participants in the final survey are

30

less diverse in their educational experiences with 100% of the final sample having college and

post graduate experience.

Table 1

Delphi Rounds 1,2,3, Panelist Demographics

Table 1

Round 1

Round 2

Round 3

Demographic

N (35)

%

N (20)

%

N (18)

%

Age

18- 22

1

3%

1

5%

-

23-30

11

32%

8

40%

8

44%

31-40

17

48%

8

40%

8

44%

41- 55

5

14%

2

10%

1

6%

Prefer not to answer

1

3%

1

5%

1

6%

Stakeholder Status

Sexual Researcher (SR)*

13

37%

7

35%

6

33%

MSM Community

member (MSM)

22

63%

13

65%

12

67%

31

Gender identity

Male

27

77%

15

75%

13

72%

Female

8

23%

5

25%

5

28%

Sexual Orientation

Gay

24

70%

14

70%

12

67%

Lesbian

1

3%

1

5%

1

6%

Bisexual

3

8%

2

10%

2

12%

Queer

3

8%

1

5%

1

6%

Heterosexual

4

11%

2

10%

2

10%

Relationship Status

In a relationship

23

66%

12

60%

11

61%

Single and Actively

Seeking a committed

relationship

6

17%

4

20%

4

22%

Single and Casually

Dating

1

3%

-

-

32

Single and not dating

5

14%

4

20%

3

17%

Nature of relationship

N (23)

N (12)

N (11)

Monogamous

19

83%

10

83%

9

81%

Monogamish (mostly

monogamous)

4

17%

2

17%

2

19%

Open

-

-

-

-

-

-

Race

European American

23

66%

16

80%

15

83%

African American

4

11%

2

10%

1

6%

Asian American

3

9%

1

5%

1

6%

Hispanic

1

3%

-

-

Mena

1

3%

-

-

Native Hawaiian

1

3%

-

-

Asian

2

5%

1

5%

1

6%

33

Education

Postgraduate

23

66%

14

70%

13

72%

College Graduate

9

26%

5

25%

5

28%

Some College

2

5%

1

5%

-

Completed 12 years or

HS equivalent

1

3%

-

-

Note. *Two Sexual researchers identify as MSM community members and are noted as (MSR)

Procedure

As noted, the Delphi method is an ideal methodology for gathering consensus amongst

community stakeholders and experts to define a large broad concept such as consent (Forbes,

2020; Jorm, 2015). Following institutional review board approval (UND IRB-201811-094), in

line with the Delphi methodology, participants are recruited and asked to engage in a multi-

round study coordinated by a researcher (Jorm, 2015). In the current study, participants were

identified and recruited through a snowballing methodology by both reviewing current literature

and authorship in sexual violence, sexual violence prevention, and human sexuality, as well as

outreach to MSM specific groups and listservs. Once identified, participants were also invited to

nominate parties who may fit the criteria for the population to also join the study.

Participation in this study was done exclusively online through Qualtrics, which is in line

with both methodological best practice and health board best practice (Ross, 2000). In Round

34

One, participants were provided with either a personalized link or anonymous link which

outlined risks and benefits and were asked to complete a 33-item questionnaire which consisted

of three distinct tasks. Task one of this questionnaire collected participants’ demographic

information. During task two of Round One, participants were asked to provide broad opinions

on the topic of sexual consent via open-ended questions. Finally, task three of Round One asked

participants to review a list of communicative behaviors associated with consent and provide

feedback on that list (Beres 2010). Following the completion of Round One, the open-ended data

collected from the 35 unique participants was qualitatively analyzed and used to construct the

Round Two survey.

In line with the Delphi methodology, data from Round One was collected, analyzed, and

collated to create the Round Two survey (Jorm,2015). During Round Two the first task asked

participants to review and provide feedback regarding their level of agreement with their peers'

qualitative responses (31 in all) to the question “How would you describe sexual consent (Q48)”.

More specifically, after reviewing an individual Round One qualitative response, participants

were asked to note their level of agreement with their peers’ statement on a 5-point Likert scale 1

(This does not adequately describe sexual consent) to 5 (This very much describes sexual

consent).

The second task of Round Two invited participants to provide narrative feedback on the

six broad qualities of consent that were derived (by the researcher) from participant responses to

Q48 in Round One. The third task of Round Two asked respondents to rank order the six broad

qualities of consent in order from importance (ranking 1-6, with 1 as most important). In the

fourth and final task of Round Two, participants were asked to provide their thoughts on sexual

35

non-consent through a response to a set of open-ended questions which included “How would

you describe sexual non-consent?” 20 participants from Round One (57%) completed Round

Two of this three-round study.

Round Three of this three-round study consisted of four distinct tasks that participants

were asked to complete. The first task consisted of asking participants to review their peers’

responses to the Q72 of Round Two and provide feedback regarding their level of agreement

with their peers’ conceptualization of sexual non-consent. Specifically, participants were asked

to note their level of agreement with peers’ statements on a 5-point Likert scale 1 (This does not

adequately describe sexual non-consent) to 5 (This very much describes sexual non-consent).

The second task of Round Three asked participants to review five elements of sexual

non-consent which were derived (by the researcher) from the groups’ open-ended responses to

Q72 in Round Two Following their review of these five elements of sexual non-consent,

participants were again asked to provide feedback and to rank order the elements of sexual non-

consent in terms of impact (ranking 1-5, with one as the most impactful). In the third task of

Round Three, participants were provided with their personal rank ordering of consent qualities

collected in Round Two and asked to compare their personal positioning with the groups’

collective rankings of consent qualities. After comparing these rankings, participants were asked

to confirm their personal rankings.

The final task of Round Three asked participants to review qualities of sexual consent

and elements of sexual non-consent as determined by the group. Following their review of these

items, participants were asked to review and sort a list of nonverbal behaviors of sexual consent

36

communication derived from the group’s responses in round one and sort them into groups based

on their perceived function (i.e., do the individual items represent Consent Giving Behavior,

Consent Seeking Behavior, Interchangeable Consent Behavior, Ambiguous consent Behavior, or

Consent Refusal Behavior). For Round Three, 18 of the 20 respondents to Round Two (90%)

completed all four tasks.

Data Analysis

In line with the Delphi methodology, a mixed method approach was used to assess the

qualitative and quantitative data collected as part of this study (Skulmoski, Hartman, & Krahn,

2007). A key element of Delphi studies is the reaching of consensus on an issue by a panel of

experts (Jorm, 2015). Formally there are no guidelines for establishing consensus within a given

delphi study, therefore, in the current study a novel and new three-tiered system of group

agreement was established in order to better determine the level of and reveal the nuances of

agreement amongst participants (Jorm 2015; Nair et al. 2011; Waggoner, Carline, Durning,

2016). The top tier of this three-tier system was termed Major Consensus, which was met when

90% of participants of the study were in agreement on an issue as demonstrated by their

responses on the Likert scale. The second tier was termed Consensus and was reached when 70%

of participants indicating agreement on a singular issue as demonstrated by their responses on the

Likert scale. The final tier was termed Endorsement and consists of 50 % of participants

indicating agreement on an issue as demonstrated by their responses on the Likert scale.

Similarly, when examining qualitative data in Delphi studies there are few guidelines in

place for data analysis, thus for this study a grounded constructivist framework was applied for

the data analysis with the adoption of an outside reader to increase trustworthiness (Chamaz,

2008; Skulmoski, et al. 2007; Krippendorff, 2015). The grounded constructivist framework was

37

selected for its usefulness in analyzing data for major themes, as well as its emphasis on the role

of the researcher and the lens by which they view and interpret the data (Chamaz, 2008). In the

current study, the author thoroughly read the data before attempting to code responses (with both

open coding and axial coding), kept a journal (“memoing”) to utilize the reflective process,

utilized a reader to provide an additional point of view, and provided participants with

opportunities to provide feedback regarding the coding process (Chamaz, 2008).

Data Analysis Round One

During Round One, qualitative responses to question 48 were collected and analyzed

using a grounded constructivist framework. Responses were initially de-identified by the first

author and reviewed for key elements in the responses. Key elements included overall ideas or

statements indicated by a participant as being central to their notion of sexual consent (Chamaz,

2008). Following the highlighting of key elements, seven overarching codes were developed, and

responses were sorted along those codes for subsequent analysis. Utilizing the constructivist

grounded framework (Chamaz, 2008), responses were analyzed for content to derive six overall

qualities.

Data Analysis Round Two

Following the collection of qualitative data in round one, the group was asked to establish

consensus regarding the descriptions of sexual consent provided by the group, utilizing a five-

point Likert scale. The mean and standard deviation was used as a mechanism to indicate

participants' overall level of agreeance to the sexual consent descriptions and help inform

whether consensus was reached. In the current study, consensus was defined according to the

percentage of participants who fell in agreement regarding a description. Major Consensus was

defined as at least 90% of participants selecting a 4 or 5 on the Likert scale, Consensus was

38

defined as at least 70% of respondents selecting a 4 or 5 on the Likert scale, and an Endorsement

was at least 50% of participants selecting a 4 or 5 on the Likert scale (Bono, 2017; Jorm 2015;

Nair, Aggarwal, Khanna, 2011; Waggoner, Carline, Durning, 2016).

Finally, data was collected from Round Two to help construct the Round 3 survey.

Participant’s initial rank order positions of six qualities of sexual consent were collected and

averaged to construct an initial ranking. Additionally, during the second round, 20 qualitative

responses were gathered to question 72 regarding elements of sexual non-consent. Again,

utilizing a grounded constructivist framework, responses were analyzed and coded into five

elements of sexual non-consent (Table 10).

Data Analysis Round Three

Participants in Round Three were asked to review their peers’ response to question 72 regarding

descriptions of sexual non-consent via a Likert scale. Means and standard deviation were used to

help determine which tier of group agreement was met (e.g., Major Consensus ≥90%, Consensus

≥70%, Endorsement ≥ 50%). Additionally, participants in round three were asked to review their

initial individual rank order positions of sexual consent qualities and re-rank these qualities after

comparing them to the group aggregate. Again, results from these rankings were collected and

analyzed by the percentage of group agreement. Next, participants were also asked to review and

rank a list of elements of non-consent during this task which was analyzed for consensus based

on the three-tiered group agreement system.

The final task of Round Three asked participants to sort a list of nonverbal consent

behaviors among six categories of usage (Consent Giving Behavior, Consent Seeking Behavior,

Interchangeable Consent Behavior, Ambiguous consent Behavior, Consent Refusal Behavior,

Unused behavior). The tiered system of agreement was utilized sorted a given behavior into a

39

usage category. Additionally, a chi-square analysis was run to examine for significant differences

in sorting of behavior usage by group membership (SR vs. MSM).

40

RESULTS

Across three rounds, the current study gathered data from participants regarding their

conceptualization of sexual consent and consent communication behaviors. Participants

consisted of researchers of human sexuality, sexual violence, and sexual violence prevention, as

well as MSM community members. Throughout each round both qualitative and quantitative

data was gathered in order to better understand sexual consent and its’ nonverbal communication

practices. The current study sought to explore three topics, including sexual consent, sexual non-

consent, and nonverbal communication behaviors associated with sexual consent. In the

following results section, each of the subjects is discussed in depth covering each subject and its

exploration through all three rounds of the study.

Sexual Consent Results

In Round One, participants were asked to respond to the open-ended prompt of “How

would you describe sexual consent?” participants provided 34 unique qualitative descriptions of

sexual consent. These responses were analyzed with three responses being consolidated due to

similar content for a total of 31 descriptions (Charmaz, 2008, see left panel of Table 2).The 31

descriptions of sexual consent formed the central data for open and axial coding. Six broad

categories emerged from the coding of the 31 descriptions and these were used to construct six

broad qualities of sexual consent shown below:

1. Sexual consent should be mutual between all parties.

2. Sexual consent should be permission granting/ affirming.

41

3. Sexual consent should be confirmed via verbal and non-verbal behaviors.

4. Sexual consent should be freely/given without influence.

5. Sexual consent should be ongoing.

6. Sexual consent should be reversible/ revocable.

Sexual Consent quality one, was derived from Broad category (1) Mutual Agreement.

Descriptions coded with Mutual Agreement noted the need for a mutuality of agreement or

consent between parties. Seventeen responses were coded with Mutual Agreement, a sample

response coded with Mutual Agreement was: “Sexual consent is mutual agreement to engage in a

sexual activity while setting specific boundaries”.

Broad category (2) Permission Granting/ Affirming was utilized when a description noted

an element of permission granting or affirmation behaviors as part of the consent process. This

code was utilized a total of 15 times and is best exemplified by the description “Sexual consent is

the active and ongoing affirmation that sexual activity is desired or welcomed. Affirmation

includes verbal and nonverbal communication.”

Broad category (3) is Confirmed via verbal and non-verbal behaviors, which was used

when Response notes an explicit need for verbal or nonverbal confirmation among parties. A

total of six descriptions utilized this code and it is best exemplified by the description:

“Consistent with muehlenhard et als review paper, an explicit agreement to do something. can be

communicated verbally or nonverbally”.

42

The next broad category (4) Freely Given/ Without Influence was used when a

description noted that lack of coercion, substance induced influence is necessary when giving

consent. A total of six descriptions were coded with Freely Given/ Without influence and this

category is best exemplified by the description: “Sexual consent is a mutual agreement between

2 or more people to engage in sexual activity - without coercion or compensation. All people

must be capable of consenting and agreeing.”

Broad Category (5) Ongoing was utilized with descriptions which noted consent is a

continuous process and must be present for the duration of activity. Ongoing was used for a total

of six descriptions and is best exemplified by the statement: “When adult confirms…This

confirmation must be present for the duration of the sexual activity…”.

Broad Category (6) Reversible, was used with descriptions that noted that consent has

elements that are reversible or revocable. This code was used a total of four times and is best

exemplified by the description: “Permission to engage sexual activity from the other person(s).

This permission can be rescinded at any time before, during, or after.”

In Round Two, participants reviewed the 31 original descriptions of sexual consent

collected in Round One, as well as the six qualities of sexual consent. In the first part of Round

Two, participants rated the 31 original descriptions of sexual consent on a five-point Likert scale

with 1 being “This does not adequately describe consent” and 5 “This very much describes

consent”. Table 2 records the mean, standard deviation, and variation of the groups’ responses to

each description of sexual consent. Additionally, Table 2 notes the consensus percentage for

each response, specifically the number of participants who indicate a four or five on the Likert

43

scale. Of the 31 descriptions rated in round two, 24 descriptions (77%) met some form of group

agreement. Descriptions number ten and seven also met group consensus with majority rating

these statements negatively with a 1 or 2 on the Likert scale and thus were not included in the

analysis of table 2. Of those 22 descriptions with a positive level of agreement, 7 descriptions

(31%) reached a Major Consensus with 90% of participants indicating a four or five on the

Likert scale; 5 descriptions (22%) reached Consensus with 70% of participants indicating a four

or five on the Likert scale; and 10 descriptions (45%) reached an endorsement of the group with

50% of the group indicating a four or five on the Likert scale. Finally, Table 2 also records

limited demographic information of the participants who make up the consensus response.

Specifically, means, SD and consensus percentage of stakeholder groups are recorded in Table

Two denoted by their abbreviation.

Table 2,

Round 2, Level of Agreement to Descriptions of Consent 1(This does not adequately describe

consent) to 5 (This very much describes consent) with Mean, Standard Deviation, and Variance

Table 2

Description

M

SD

Conse

nsus

%

1. I imagine 2 formal variations in

consent:1) Responding in the affirmative to

a suggestion for sexual activity (responding

by saying “yes” to a verbal, physical, or

otherwise suggestive (look, gesture, body or

body-part positioning or repositioning)

request to engage in sexual activity); or2)

Panel

4.0

1.07

80%

(n=16)

SR

4.0

.70

80%

44

Initiating the above expressed suggestion to

engage in sexual activity. However, a

caveat I would like to mention is that

perceived consent from one party may not

be the actual expression of consent by the

other. **

(n = 4)

MSM

4.0

1.2

77%

(n=

10)

MSR

4.0

0

100%

(n = 2)

2. Two adults confirming they are

comfortable with engaging in sexual

activity.**

Panel

4.1

.78

75%

(n=15)

SR

4.0

0

100%

(n = 5)

MSM

4.3

.85

77%

(n=

10)

MSR

3.0

0

-

3. Having permission and agreement from a

partner(s) to engage in a sexual act that is

not coerced or influenced in any one.***

Panel

4.3

.74

90%

(n=

18)

SR

4.4

.89

80%

(n = 4)

MSM

4.38

.76

80%

(n =

45

12)

MSR

4.0

0

100%

(n = 2)

4. I would describe sexual consent as the

effective communication of ongoing,

affirming, equitable, relational decisions

regarding sexual choice among partners of

free-will. ***

Panel

4.55

.82

90%

(n=

18)

SR

5

0

100%

(n = 5)

MSM

4.30

.94

84%

(n =

11)

MSR

5.0

0

100%

(n = 2)

5. Sexual consent is an ongoing process to

engage in sexual activities with another

person. Sexual consent can be withdrawn at

any time and for any reason. Some

individuals are unable to give sexual consent

due to the undue influence of power to obtain

that consent (e.g. children, individuals in

police custody, people with advanced

dementia). ***

Panel

4.6

.81

90%

(n=

18)

SR

5.0

0

100%

(n = 5)

MSM

4.69

.63

92%

(n =

12)

46

MSR

3.5

2.12

50%

(n = 1)

6. Mutual and unambiguous understanding

between all parties that a sexual activity is

desired and being entered into and

participated in without coercion,

exploitation, or abuse. ***

Panel

4.5

.75

95%

(n=19)

SR

4.4

.54

100%

(n = 5)

MSM

4.61

.63

92%

(n =

12)

MSR

4.5

..5

100%

(n = 2)

ix

7. consistent with muehlenhard et als review

paper, an explicit agreement to do

something. can be communicated verbally

or nonverbally

Panel

3.1

1.2

35%

(n= 7)

SR

3

1.58

40%

(n = 2)

MSM

3.15

1.34

38%

(n = 5)

MSR

3.0

0

-

8. All parties being of sound mind to give

verbal permission to engage in any activity

believed to be, or identified as, sexual

Panel

3.5

1.1

45%

(n=9)

SR

2.4

.8

-

MSM

3.92

1.03

61%

(n = 8)

MSR

3.5

.5

50%

(n = 1)

9. Sexual consent is when both people agree

on a specific act when intimate with each

other.

*

Panel

3.3

.87

40%

(n=8)

SR

2.8

.75

20%

(n =1)

10

MSM

3.92

1.34

46%

(n = 6)

MSR

3.5

.5

50%

(n = 1)

10. A verbal agreement between two

consenting adults

Panel

2.5

1.2

25%

(n=5)

SR

1.6

.75

60%

(n = 3)

MSM

2.92

1.32

15%

(n = 2)

MSR

2.5

.5

-

11. Permission to engage sexual activity

from the other person(s). This permission

can be rescinded at any time before, during,

or after. **

Panel

4.05

.88

75%

(n

=15)

SR

3.6

.24

60%

(n = 3)

MSM

4.46

.66

92%

(n =

12)

11

MSR

2.5

.5

-

12. Sexual consent is mutual agreement to

engage in a sexual activity while setting

specific boundaries *

Panel

3.9

.78

65%

(n=13)

SR

3.8

.83

80%

(n = 4)

MSM