The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 2

The INSPIRE Journal is a publication of The INSPIRE Project

Inc., a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational scientific corporation

(FEIN 95-4418628). Letters and submissions for The INSPIRE

Journal should be emailed to: Editor@TheINSPIREProject.org

© 2018. The INSPIRE Project Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Contents

From the Managing Editor .............................................. 3

Eva Kloostra

INSPIRE NASA Goddard Summer Interns Report ........ 4

Derek Acosta & Tramia Johnson

INSPIRE Educational STEM Programs .......................... 6

William Taylor STEM Scholarship Recipient ................. 9

Kuishon Brown

56°25’59” N 8°46’35” Ø 52 M OVER HAVET

INSPIRE VLF Kits featured in Danish Arts Foundation

Permanent Installation ................................................. 10

Christian Skjødt

August 21, 2017: A Solar Eclipse

for the United States ...................................................... 11

M. L. Adams

INSPIRE 2017 Solar Eclipse VLF Field Experiment .... 19

Dr. Dennis Gallagher & Field Team

The “ Peay’Clipse” Experience: Scientists from

NASA, INSPIRE and Austin Peay State University

study living organisms during the Great

American Eclipse ........................................................... 23

Dr. Donald Sudbrink Jr.

The Boy Who Noticed the Watermelon Flowers ......... 29

Dr. Amy Wright

INSPIRE Space Academy Alumni Students

Total Solar Eclipse Experience & Observations ......... 31

Eva Kloostra, Karin Edgett, Charis Houston,

Clark Gray, Isadora Germain, Colby Gray,

Michaela Mason, Robert Allsbrooks IV, Nile Brown,

Bryce Stephens, Christian Jenkins, Julian Thomas,

Justice Flora, Joshua Simpson, José Antonio Galicia

Salazar, Maysoon Harunani & Sabrina Hare

INSPIRE 2015 Space Academy Alumni Student

Featured in The Mars Generation ................................. 42

Van Moreau

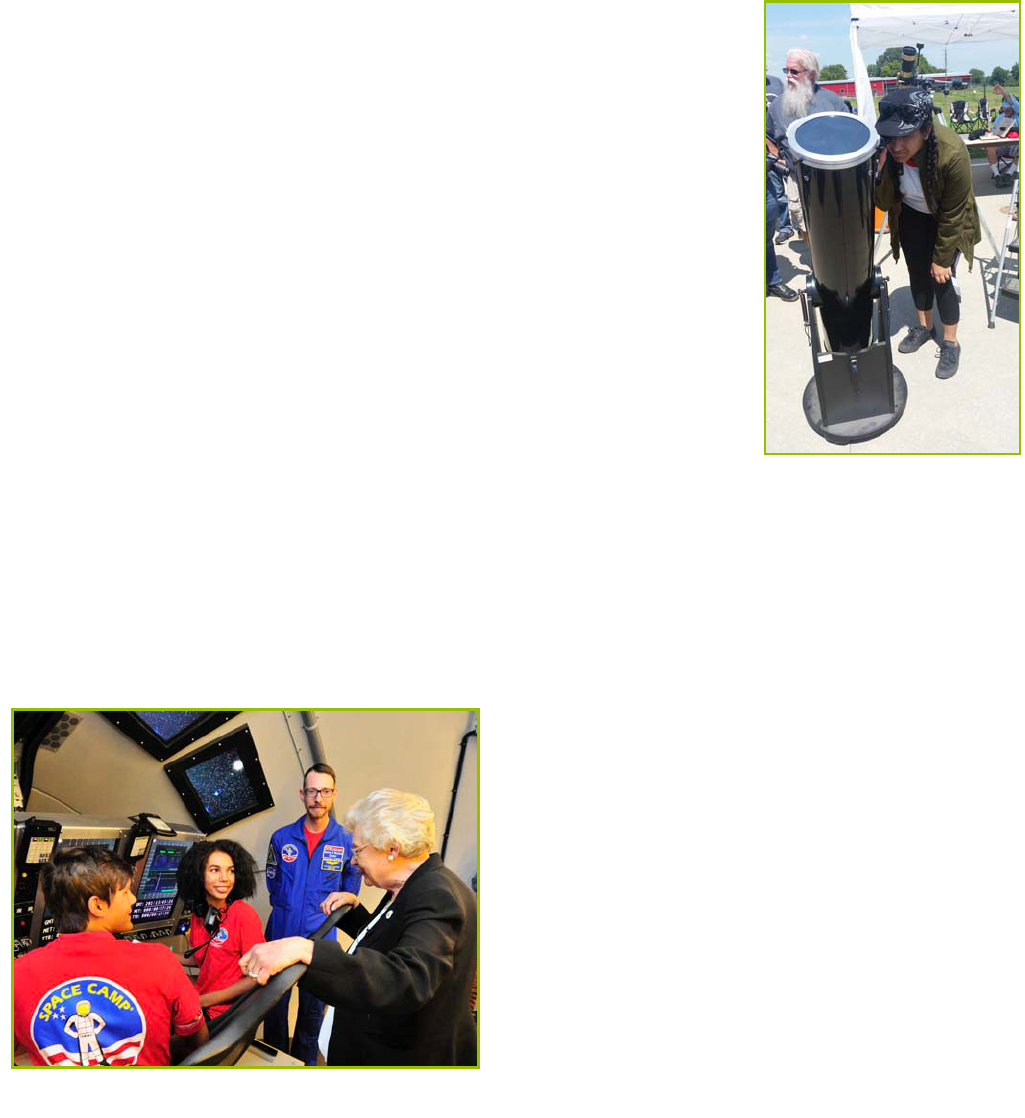

Space Academy – Inspiring Our Next Generation ...... 43

Sasha Varner, Jucain Butler, Carton Drew,

Jeamay Palo and students Kiera, Ava & Evan

Yahoo VLF Discussion Group ...................................... 46

Mark Karney & Shawn Korgan

INSPIRE VLF-3b Receiver Technical Notes ................. 47

Dennis Gallagher & Paul Schou

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Phillip Webb, President

Paul Schou, Vice President

Anne Taylor, Treasurer

Karin Edgett, Secretary

BOARD MEMBERS

Fatima Bocoum, International Telecommunication Union

Rick Chappell, Vanderbilt University

Ellen McLean, Fairfax County Public Schools

Jim Palmer, Space Telescope Science Institute

ADVISORS

Dennis Gallagher, Chief Technical Advisor

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

Leonard Garcia, Space Physics/Goddard Intern Advisor

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Lou Mayo, Goddard Educational Advisor

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Tim Eastman, Goddard Science Advisor

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Mitzi Adams, Educational & Technical Advisor

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

David Piet, STEM Advisor, Datrium

Jacqueline Fernandez-Romero, STEM Educational Advisor

Alma Smith, Grades 6-12 STEM Educational Advisor

Julia Martas, Grades 6-12 STEM Educational Advisor

Eva Kloostra, Space Ad Agency, Educational Program

Manager and Journal Managing Editor

INSPIRE’S LEGACY

Dr. William (Bill) W. L. Taylor was a leader in the field of

space science education and public outreach. He co-founded

and was president of INSPIRE, one of the pioneering

successes in NASA Sun Earth Connection Education. NASA

Goddard Space Flight Center honored the late William W. L.

Taylor with an Excellence in Outreach in Science Award for

his accomplishments.

CO-FOUNDER/EMERITUS

William E. Pine

IN MEMORIAM

Kathleen Franzen, President 2005 - 2010

Jack Reed, INSPIRE Board Member 1992 - 2009

Jim Ericson, INSPIRE 1st Vice President 1981 - 2006

MISSION

The INSPIRE Project Inc. is a non-profit scientific, educational

corporation whose objective is to bring the excitement of observing

natural and manmade radio waves in the audio region to high school

students. Underlying this objective is the conviction that science and

technology are the underpinnings of our modern society, and that

only with an understanding of science and technology can people

make correct decisions in their lives, public, professional, and

private. Stimulating students to learn and understand science and

technology is key to them fulfilling their potential in the best interests

of our society. INSPIRE also is an innovative, unique opportunity for

students to actively gather data that might be used in a basic

research project.

- William W. L. Taylor and William E. Pine, Co-Founders

In 2006, The INSPIRE Project’s mission was expanded to develop

new partnerships with multiple science projects. Links to

magnetospheric physics, astronomy, meteorology, and other

physical sciences are continually being explored.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 11

August 21, 2017:

A Solar Eclipse for the United States

M.L. Adams

1

1

Heliophysics and Planetary Science Branch, ST13, NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC),

Huntsville, AL 35812

mitzi.adams@nasa.gov

ABSTRACT

For the first time in almost 100 years, the narrow path of the Moon’s shadow fell upon the United States, stretching from one

coast to the other; everyone in the U.S. could see at least a partial solar eclipse. For those in the path of totality, in addition to

photographing an awe-inspiring sight, there were opportunities to perform scientific research under relatively unique

conditions. This article will describe the partnerships and projects that were developed for the total solar eclipse of August 21,

2017.

Keywords: Solar eclipses

1. INTRODUCTION

A total solar eclipse is such an unusual and somewhat frightening phenomenon that our ancestors revered their astronomer

priests. In the case of the Inca civilization however, those priests took their power from being able to keep a calendar; but

surprisingly, they could not predict eclipses, which exalted the Spanish conquerors because they could (Bauer & Dearborn

1995). To predict eclipses today, we use the power of the computer and an understanding of orbital mechanics. In addition,

when combined with observations from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (see https://lunar.gsfc.nasa.gov), which provides

details of the lunar-limb profile, the result is the most precise and accurate prediction of an eclipse’s path of totality (e.g., see

https://eclipse2017.nasa.gov/eclipse-maps). Knowing this path accurately allowed millions of people in the United States to

plan travels to view this phenomenon first hand, and hopefully has inspired another generation to study Science, Technology,

Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM).

Since the birth of the United States in 1776, there have been twenty total-solar eclipses, whose paths of totality have touched

some part of the continental United States: June 24, 1778; October 27, 1780; June 16, 1806; November 30, 1834; July 18,

1860; August 7, 1869: July 29, 1878; January 1, 1889; May 28, 1900 (0.99% total in Atlanta, Georgia); June 8, 1918 (bisected

the U.S. like 2017); September 10, 1923 (through a tiny bit of SW California); January 24, 1925 (New York, New Jersey,

Pennsylvania); August 31, 1932 (Vermont, New Hampshire); July 9, 1945 (only Idaho and Montana); June 30, 1954

(Nebraska, Minnesota, Michigan); October 2, 1959 (New Hampshire, Massachusetts); July 20, 1963 (Maine); March 7, 1970;

February 26, 1979, and August 21, 2017 (see the World Atlas of Solar Eclipse Paths, Second and Third Millennia CE

https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEatlas/SEatlas.html#2CE).Thomas Jefferson attempted to observe the first solar eclipse to be

recorded in the new United States in 1778, but there were clouds at his observing site in Virginia

(see https://www.monticello.org/site/visit/events/jefferson-and-solar-eclipses). The first American eclipse expedition was

mounted for the 1780 eclipse, led by Professor Samuel Williams from Cambridge; the observers were located at Penobscot

Bay in Maine, where inaccurate calculations of the path of totality placed them just outside it. Professor Williams did however

observe Baily’s Beads, and wrote:

After viewing the Sun’s limb about a minute, I found almost the whole of it thus broken or separated in drops,

a small part only in the middle remaining connected (Todd 1894).

Vassar College’s first professor, Maria Mitchell, led her students to view the total solar eclipses of 1869 and 1878.

Observations made by the women of the 1869 eclipse were published in the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac

(see http://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/faculty/original-faculty/maria-mitchell1.html). The eclipse expedition to view the July 29,

1878 total solar eclipse included Professor Mitchell, her sister, and four Vassar graduates. Although these women endured lost

luggage, which threatened to prevent them from observing the eclipse (near Denver, Colorado), they were still able to set up

camp with their telescopic equipment in time. This expedition was privately funded by Professor Mitchell, since no outside

funding source would do so, because all participants were female.

Quite a different situation existed for the August 21, 2017 solar eclipse. Many women and young girls, men and young men,

were involved in this event, and were funded to organize, observe, carry out experiments, and report on this eclipse. Plans

began in 2015 between Dr. Allyn Smith of Austin Peay State University (APSU) and myself, with a few simple words by

Dr. Smith, “The path of totality goes through the APSU campus. We should plan something together.” From that humble

beginning, and in addition to the participation of The INSPIRE Project, we were able to involve the U.S. Space and Rocket

Center (USSRC) in Huntsville, Alabama, Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC) TV crew, school systems in Clarksville,

Tennessee and Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and the Space Hardware Club of the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH).

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 12

2. EXPERIMENTS

Austin Peay State University offered the perfect location for science experiments during the eclipse. APSU’s Agriculture

Department, headed by Dr. Donald Sudbrink, operates a working farm and Environmental Center, just ten minutes from the

main campus. The Physics and Astronomy Department has established an observatory there, complete with concrete pads

and power for telescopes. There are also two air-conditioned classrooms, a necessity for us in the middle of August in the

southeast United States.

Figure 1. Totality from Hopkinsville, Kentucky: This image, taken by Joe Matus of NASA/MSFC, shows the state of the corona on this

date, August 21, 2017.

We used the larger of the two classrooms for meals and for discussions of student projects, which included:

observations of the behavior of animals to include cows, crickets, turtles,

balloon launches with payloads that included geiger counters, real-time streaming video, temperature and pressure

measurements,

investigation of conditions of the ionosphere using Ham radio,

investigation of conditions of the ionosphere using Very Low Frequency radio (using an INSPIRE receiver),

observations of the eclipse phenomenon known as shadow bands,

tracking air temperature changes for NASA’s Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE)

project,

general eclipse photography,

language arts practice and journaling the eclipse experience.

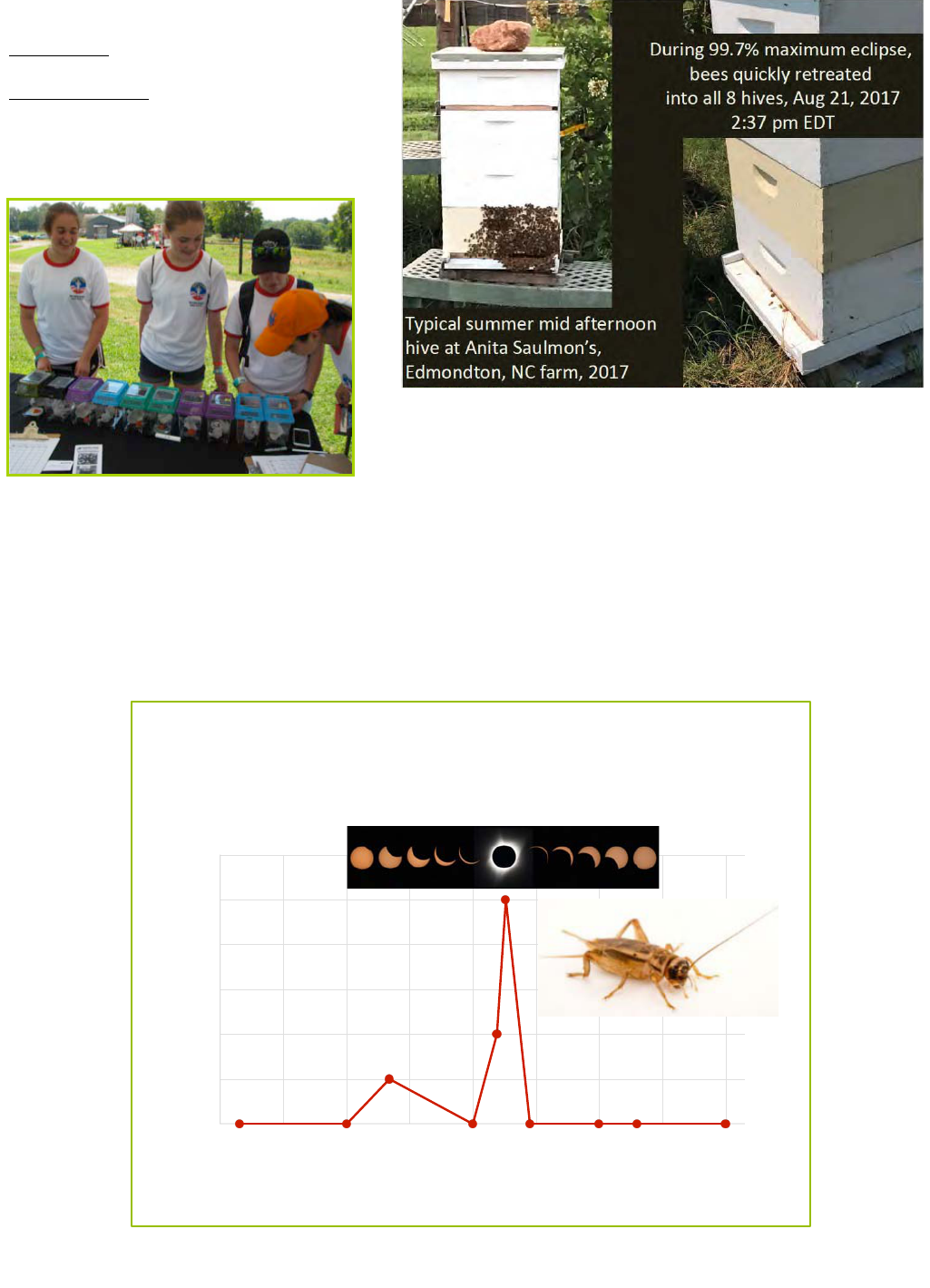

2.1 Animal Behavior

One study in the agricultural literature, reported that the total solar eclipse of August 11, 1999 had no affect on the grazing

behavior of lactating cows (Rutter 2002), even though light intensity is hypothesized to be an important factor. That study

prompted Dr. Rod Mills to lead an investigation of the behavior of APSU cows during the eclipse. To prepare for the

observations, INSPIRE students, used a non-toxic spray paint to paint numbers on the cows (see Figure 2). Before the eclipse

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 13

began, the cows were led to pasture, where the students could see them easily. The plan was to observe ten cows, but only

eight cooperated. All eight placed themselves in the shade of a tree before the eclipse began, and only one of them moved

from the shade during totality.

Figure 2. On the left, an INSPIRE Project student spray paints a cow with a number for easy tracking. On the right, all numbered

cows are moving toward their pasture on eclipse day. Photos courtesy of The INSPIRE Project.

Dr. Sudbrink, an entomologist by trade, proposed using crickets to investigate behavior changes during the eclipse. Students

from the USSRC’s Space Camp assisted in the observations of ten crickets, one cricket per cage, all kept in the shade during

the eclipse, with food and water (see Figure 3). Serendipitously, one of the students noticed that turtles were leaving a nearby

pond as the eclipse proceeded. By the time totality occurred, there were 40 turtles on the bank of the pond. Two hours later,

as light and heat intensity increased, there were only seven.

Figure 3. Ten crickets (Acheta domesticus) are housed in the colorful cages, one per cage. The image on the right shows one

of the turtles (Trachemys scripta, or pond slider) that exited the pond during the eclipse. (Images courtesy Dr. Donald Sudbrink)

2.2 Balloon Experiments

The Montana State Balloon Project, in partnership with NASA’s Space Grant Consortium and NOAA, organized fifty teams

from across the country to fly high-altitude balloons during the total solar eclipse. Each team flew a primary payload consisting

of downward-looking video cameras, which streamed to the NASA website (https://eclipse.stream.live/). Teams could choose

to fly a secondary payload of their choice. The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) team, for example, flew hops for a

local brewery, which then produced an ”eclipse beer”. In addition, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory provided samples of bacteria

to investigate the effects of radiation and reduced atmospheric pressure at 100,000 feet, conditions similar to Mars. Three

teams participated at APSU: APSU itself, Arkansas State, and UAH (see Figure 4).

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 14

Figure 4. Left: INSPIRE Project students hold and fill a balloon. Middle: APSU Physics Department Laboratory Manager Bryan Gaither

holds the APSU balloon, prior to launch. Right: Launch! (Left and right images courtesy of The INSPIRE Project, middle image from

NASA’s video of the eclipse)

2.3 The Ionosphere

It is well known that X-and UV-radiation from the Sun ionizes atoms and molecules in our atmosphere during the day and that

at night electrons recombine with their parents. The net effect is that radio waves can travel farther at night. During the day, a

radio signal (if not of very high frequency) will either be weakened or will “bounce” off the ionized ”D” layer of the ionosphere,

as seen on the left side of the right panel in Figure 5. When the D layer “opens up at night’, the transmitted signal goes higher

before it is reflected back to Earth, thus it travels farther. Because conditions during an eclipse mimic (for a short time,

anyway) night-time conditions, experiments were conducted during the eclipse, with the hope of better understanding the

physical properties of the ionosphere. Based on knowing the locations of high-frequency radio transmitters and distance to

receivers, temperature and density of the layer through which the radio wave travels could be determined. Many ham radio

operators participated in this type of experiment through the Reverse Beacon Network. Dr. Ghee Fry of NASA/MSFC joined

with citizen scientist Linda Rawlins at the APSU farm to set up a radio receiver to participate in this experiment. INSPIRE

students and USSRC Space Campers were also involved. The one-line essential result from the experiment is that the

behavior of the ionosphere during the eclipse was consistent with a day/night transition.

In another part of the electromagnetic spectrum, Dr. Dennis Gallagher set up an INSPIRE Project receiver to listen for Very

Low Frequency radio signals. The time around dusk, either morning or evening, is the optimal time to listen, since “holes” open

up in the ionosphere, and waves produced by lightning, can be ducted by Earth’s magnetic field to locations very far away

from the storm that produced the lightning. If conditions are just right, the wave will bounce back and be stretched out, or

dispersed. Higher frequencies arrive first back at their starting position, lower frequencies arrive later, creating a “whistle”, thus

the phenomenon is called “whistlers”. Other sounds can also be heard, spherics and tweeks. Spherics can be heard all the

time, tweeks, which are slightly dispersed, more infrequently. Figure 6 (right) shows the INSPIRE receiver, connected to a

digital recorder, which also had input from a radio for time stamp. Dr. Gallagher heard a lot of spherics, and a tweek or two, but

no whistlers. He discusses more details of this experiment in this Journal (see page 19).

Figure 5. The image on the left shows how radio waves propagate in the ionosphere (from https://swpc.noaa.gov/phenomena/ionosphere).

Low frequencies reflect at a lower altitude and do not travel long distances, higher frequencies travel higher before reflecting. The highest

frequencies do not reflect at all. The image on the right shows how upward-propagating-radio waves travel farther with no D region.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 15

Figure 6. Left: Dr. Dennis Gallagher relaxes under the canopy after confirming that the INSPIRE receiver (Right) was working properly.

Both images are courtesy of Ms. Karin Edgett of The INSPIRE Project.

2.4 Shadow Bands

A very difficult phenomenon to record, either by video or still imaging, shadow bands have been hypothesized to be the result

of a “slit” of sunlight shining through turbulent layers of Earth’s atmosphere. The perceived effect is similar to the wavy patterns

seen in a pool when sunlight shines through the water. Observers have reported a snake-like appearance of alternating dark

and light bands that move in a particular direction, often in the direction of motion of the umbral shadow. We hoped to gather

more data about this phenomenon, for example, size of the bands and direction of motion. We therefore directed the USSRC

Space Camp students to build shadow-band-boxes, inside of which the students’ cell phone could be placed. With a

translucent top on the box, the eclipse shadow bands should appear. Some shadow bands were seen with this set up, but

because contrast was so low, no

measurements could be made. However, a

Space Camp student, Michaela Mason, at the

VLF site with Dr. Gallagher, positioned her

cell-phone camera above a sheet (see Figure

7). Cardinal directions and the direction of the

approaching shadow were noted on a card

placed on the sheet. Ms. Mason’s video is

being analyzed and may have enough contrast

for quantitative measurements to be made.

Figure 7. These images show our attempt to make a

video record of shadow bands. Top Left: A smart

phone is centered in a “shadow-band box”, camera

side facing upward. Top right: On top of the box is

translucent material, like tracing paper or waxed

paper, onto which fiducial marks can be made,

similar to the ones on the bottom right image.

Bottom Left: At the APSU farm, the USSRC students

placed their shadow-band boxes in the field close to

the wind turbine. Bottom Right: INSPIRE Project

students and USSRC student, Michaela Mason,

position a sheet with fiducials and meter sticks for

scale, in preparation for shadow bands. Image

Source: Dr. Gordon Telepun, top images; Mitzi

Adams, NASA/MSFC, bottom left; Michaela Mason,

bottom right.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 16

2.5 Temperature Changes

When the Sun sets, the temperature goes down. Similarly, when the Sun is blocked by the Moon during a total solar eclipse,

the temperature decreases; but by how much? This was the question asked by NASA’s Global Learning and Observations to

Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) Observer Program (see https://observer.globe.gov/science-connections/eclipse2017).

Citizen scientists across the nation collected more than 80,000 air temperature measurements! The maximum temperature

drop at any particular site depends on a lot of factors that include terrain, elevation, and local weather patterns. Figure 8 shows

data from two different eclipses. On the left is a plot of the temperature decrease during the June 21, 2001 total solar eclipse,

which occurred over Lusaka, Zambia. The observation site was at a hotel; the temperature sensor was set approximately 0.3

m off ground composed of white gravel and concrete. The temperature change from before the eclipse began to the minimum

temperature, was approximately 13◦ F (7◦ C change). For the August 21, 2017 eclipse in Clarksville, Tennessee in an area

with a lot of pasture and very little concrete, the minimum temperature was 27.8◦ C (82◦ F), giving a 9.2◦ C (16.6◦ F) difference

from the maximum prior to the eclipse. The minimum on the plot, is the ”v” on the right side at about 1:30. The Clarksville

Farm’s latitude and longitude are noted on the upper right of the plot, 36.56◦ North and 87.34◦ West. For comparison, Lusaka

is 15.39◦ South and 28.32◦ East. Minimum temperatures taken during total solar eclipses typically lag totality by a few minutes,

because the atmosphere needs time to respond to the drop in solar radiation.

Figure 8. Left: A plot of the temperature decrease in Lusaka, Zambia during the total solar eclipse of June 2001, data taken by Mitzi

Adams, NASA/MSFC. Right: The GLOBE project supplied a kit with which to make temperature measurements, data taken by Dr. Pete

Robertson, NASA/MSFC, and USSRC and INSPIRE Project students.

2.6 Eclipse Photography

The images in this section show several ways that the Sun can be photographed during a total solar eclipse. Figure 9 top left

shows the beginning of the partial phase of the eclipse or, “first contact”, when the Moon begins to cover the Sun. This

particular image was taken at the APSU Farm in Clarksville with a hydrogen-alpha telescope. Hydrogen-alpha, or H-α, is a

specific wavelength of light at 656.28 nm emitted when a hydrogen atom’s electron relaxes from its third lowest to its second

lowest energy state. On the Sun, this light is created in the chromosphere, the middle layer of the Sun’s atmosphere (the

photosphere is the lowest, the corona the highest). The reddish color of H-α was first observed during a total solar eclipse,

when the chromosphere sticks up above the limb (edge) of the Moon. The H-α telescope allows us to observe the full-disk

chromosphere, where we often see flares, filaments (same as prominences when viewed on the limb), and active regions, or

groups of sunspots.

On August 21, there were two active regions, one to the right of the center of the solar disk, the other close to the left limb

(edge). The top right panel of Figure 9 shows the corona of the Sun and the “Diamond Ring” effect close to totality. An eclipse

photographer has two opportunities for the Diamond Ring, before and after totality, as the last bit of sunlight is obscured or

uncovered by the Moon. The image on the bottom left essentially shows what the unaided eye sees, a black hole in the sky,

surrounded by the pearly-white light of the corona. An entire sequence of images is on the bottom right, showing the

progression of the eclipse from first contact (left Sun) through the partial phases to totality, to the Diamond Ring after totality,

through partial phases to fourth contact (right Sun), when the eclipse is over. The arc formed by this sequence of images

shows how the Sun rises to its highest elevation at midday, and moves lower in the sky as it sets toward the west. Totality

occurred at approximately 1:30 p.m. Central Daylight Time, about one-half hour after astronomical midday, when the Sun is

due South.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 17

Figure 9. Top Left: First Contact in Clarksville, Tennessee as seen in the light of H-α (see text for more explanation). Photo by Mitzi Adams,

NASA/MSFC. Top Right: The Diamond Ring effect seconds before totality close to Guthrie, Kentucky. Photo by Dennis Gallagher,

NASA/MSFC. Bottom Left: This image shows APSU’s Observatory dome at the bottom right, as well as USSRC space campers and INSPIRE

Project students. Photo courtesy Sean McCully of APSU. Bottom Right: A full eclipse sequence showing partial phases, totality, and the

Diamond Ring. Photo by Debra Needham, NASA/MSFC.

2.7 Language Arts

Often overlooked by STEAM students, language arts are extremely important for clear and effective communication. Dr. Amy

Wright, professor in APSU’s Languages and Literature Department, discussed the finer points of journaling with the students.

Dr. Wright, whose expertise is non-fiction creative writing, stressed the importance of including memories of events that

include all the senses. As examples, Dr. Wright read a journal entry from Virginia Woolf and a passage from the essay “Total

Eclipse” by Annie Dillard. Writing of this type is intended to evoke images and emotions, and perhaps sound and smell as well,

all the senses. From Barden Fell, north of Ilkley in England, Virginia Woolf, as a science attentive, described totality of the

1927 eclipse in this way:

We saw rays coming through the bottom of the clouds. Then, for a moment we saw the sun, sweeping it

seemed to be sailing at a great pace & clear in a gap; we had out our smoked glass-es; we saw it crescent,

burning red; next moment it had sailed fast into the cloud again; only the red streamers came from it; then

only a golden haze (Diary 3: 143).

This quote is taken from a discussion of accounts of the 1927 eclipse, “Eclipse Madness, 1927” by Holly

Henry, found here: https://academic.oup.com/astrogeo/article/40/4/4.17/259593)

Ms. Woolf’s eclipse was shrouded in clouds with a very short totality, about 23 seconds. The red streamers, of her description

were possibly solar prominences. The account of Annie Dillard reflects a familiarity with technology, and a more technical

description:

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 18

You have seen photographs of the sun taken during a total

eclipse. The corona fills the print. All of those photographs

were taken through telescopes. The lenses of telescopes

and cameras can no more cover the breadth and scale of

the visual array than language can cover the breadth and

simultaneity of internal experience. Lenses enlarge the

sight, omit its context, and make of it a pretty and sensible

picture, like something on a Christmas card. I assure you, if

you send any shepherds a Christmas card on which is

printed a three-by-three photograph of the angel of the

Lord, the glory of the Lord, and a multitude of the heavenly

host, they will not be sore afraid. More fearsome things can

come in envelopes. More moving photographs than those

of the suns corona can appear in magazines. But I pray you

will never see anything more awful in the sky.

You see the wide world swaddled in darkness; you see a

vast breadth of hilly land, and an enormous,

distant, blackened valley; you see towns lights, a

rivers path, and blurred portions of your hat and scarf; you

see your husbands face looking like an early black-and-

white film; and you see a sprawl of black sky and blue sky together, with unfamiliar stars in it, some barely visible

bands of cloud, and over there, a small white ring. The ring is as small as one goose in a flock of migrating geese if

you happen to notice a flock of migrating geese. It is one-360th part of the visible sky. The sun we see is less than

half the diameter of a dime held at arms length. (The quote is from the full essay posted here:

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/08/annie-dillards-total-eclipse/536148/)

In this Journal, are more eclipse essays, written by INSPIRE Project students who were sponsored to travel to Tennessee and

be inspired by viewing their first total solar eclipse.

3. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are so many people without whom this project

would not have been possible, from the APSU staff to

the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, to Marshall

Space Flight Center, the Heliophysics Education

Consortium (now Space Science Education

Consortium), and NASA Headquarters. NASA and

MSFC’s Public Affairs Office worked tirelessly, and

the MSFC-TV crew created an environment that

made us all look good on camera. I will not call out

specific names, because I know I would inadvertently

forget someone. However, I do specifically thank the

folks in Figure 11: Dr. Phillip Webb, Eva Kloostra, and

Karin Edgett.

4. REFERENCES AND CITATIONS

Bauer, B. S. & Dearborn, D. S. P. 1995, Astronomy and Empire in the Ancient Andes (University of Texas Press), 54, 142

Rutter, S. M. 2002, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 79, 273

Todd, M. L. 1894, Total Eclipses of the Sun (Little, Brown, and Company), 114

About Mitzi Adams

Mitzi Adams is a solar scientist for NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), where she

studies the magnetic field of the Sun and how it affects the upper layer of the solar atmosphere,

the corona. Ms. Adams, a daughter of Atlanta, earned a Bachelor of Science degree in physics

with a mathematics minor from Georgia State University. In 1988, the University of Alabama in

Huntsville and NASA made her an “offer she couldn't refuse" and she moved to Alabama,

where she earned a Master of Science degree in physics and began work at NASA/MSFC.

With a professional interest in sunspot magnetic fields and coronal bright points, friends have

labelled her a “solar dermatologist". Frequently involved in educational outreach activities such

as viewing solar eclipses and transits of Mercury and Venus, Ms. Adams sometimes seeks

innovative material in unusual places. While few women travel alone, she has often been seen

alone and in groups in the wilds of Peru, northern Chile, Guatemala, and southern Italy.

Figure 10. Dr. Amy Wright of APSU gives pointers on science journaling

Figure 11. Left: Dr. Webb, INSPIRE Project’s President, with INSPIRE’s

Program Manager Eva Kloostra, after the post-eclipse celebratory meal. Right:

INSPIRE’s Project’s Secretary Karin Edgett poses with her eclipse glasses in

the field belonging to Rudy Hall near Guthrie, Kentucky.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 19

INSPIRE 2017 Solar Eclipse VLF Field Experiment

Dennis Gallagher

1

, Mitzi Adams

1

, Rose Bollerman

4

, Jesse-lee Dimech

1,5

, Karin Edgett

3

,

Clark Gray

3

, Colby Gray

3

, Isadora Germain

3

, Charis Houston

3

, Nick Keesler

2

, Eva Kloostra

3

,

Michaela Mason

4

, Chris McCarthy

4

, Destiny Frink-Morgan

3

, Allyn Smith

2

, Christopher Stephens

3

,

Hector Torregrosa

4

1 NASA Marshall Space Flight Center 4 US Space & Rocket Center Elite Space Camp

2 Austin Peay State University 5 now at Geoscience Australia

3 The INSPIRE Project

Five INSPIRE Students and three US Space & Rocket Center students in an elite Space Camp program along with

chaperones, parents, mentors, and neighbors gathered at a remote location on the morning of August 21, 2017 to experience

a solar eclipse. The plan was to run field experiments that included: recording VLF radio noise, video taping eclipse shadow

bands, testing a partial-solar-eclipse image projection tent, viewing the Sun through a 6-inch Celestron telescope,

photographing the Sun with a Nikon camera and super-telephoto lens attached to the telescope, and recording the horizon

during totality using a rotating camera. To accomplish our first goal of recording VLF radio sounds, our group had to be well

away from alternating current (AC) electrical power, which proved to be a challenge.

The field site is only about 1.37 miles (2.2 km) from the totality centerline, which makes this an amazing find. The Tennessee

Valley area, including this site, was targeted by Federal legislation in 1933 to create the Tennessee Valley Authority with the

charter to develop this area devastated by the Depression. The charter included providing electrical power, so it is quite hard

to find and get to any location away from the power grid. However, thanks to Kentucky farmer, Mr. Rudy Hall, we were able to

make our observations from Mr. Hall's farm near Guthrie, Kentucky (Lat.: 36.743° N, Long.: 87.2124° W). Dr. Jesse-lee

Dimech, a post-doctoral researcher at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, took the picture shown as Figure 1.

Figure 1: Field-site between Mr. Rudy Hall’s farm fields near Guthrie, Kentucky, USA. The picture is by Jesse-lee Dimech.

The field-site was setup as shown in Figure 2. The site elements were arranged with those most visitor friendly nearest the

local access road. The VLF setup and telescope/camera were farthest from the entrance to the area. We were happy to have

Mr. Hall setup a tent near us so that we could easily share what we were doing with him and his family. I leave it to the reader

to figure out KYBO, though it proved useful during the 5 hours or so of our visit. Figure 3 is a photograph of the site during

partial phase of the eclipse. We could listen to the VLF while it was recording and mostly be preoccupied by the Sun and

expectations for seeing the corona during totality.

Figure 2: Eclipse-VLF field-site layout Figure 3: During partial eclipse at the VLF field-site

Photo courtesy of The INSPIRE Project

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 20

A white sheet and tripod mounted cell phone were set up at our site, as shown in Figure 4, for the purpose of capturing

shadow bands if they happen to appear. Shadow bands are thought to be caused by an atmospheric effect during about the

30 seconds just before totality and 30 seconds just after totality ends. Michaela Mason, one of our authors, used her phone to

take 5 minutes of video spanning totality and was rewarded by seeing the light-dark shadow bands moving across the sheet.

Because the bands have low contrast, they are difficult to photograph. Figure 4 is the result of enhanced contrast and

differencing two sequential images from the video taken by Michaela. The bands visible in the difference-image reflect

movement of the bands toward the camera rather than directly showing the bands as seen by an observer next to the sheet.

That can more easily be shown by checking out the diagonal black-white streak in the upper-left portion of the sheet, which is

caused by the blurred image of an insect that was caught flying from left to right. The white streak shows where the insect was

in the second of the differenced video frames and the black streak where it was in the first.

Figure 4: Enhanced shadow bands are shown. The original video was taken by Michaela Mason.

The projection tent was our way to create a substitute for tree leaves during the partial phase eclipse. Sunlight passing through

pinholes in a raised black sheet produced crescent images on a white sheet on the ground. Just like the small gaps between

tree leaves, each hole projected the eclipsing Sun so that many could see it at the same time. A close up of a few of those

projections are shown in Figure 5. A colander can also be used to create this effect.

As noted elsewhere in this issue, the ionosphere was

expected to exhibit reduction in D-layer ionization

within the path of eclipse totality. The objective of

hosting a field-site for VLF observations was to

engage students in testing whether those changes

were enough to change the character of VLF radio

noise that is normally observed at this location and

time of day. Whistlers are not common at this latitude,

but like most places, spherics can be observed most

of the time and tweeks are not uncommon after

sunset and before sunrise. Atmospheric scientists

were contacted to provide lightning discharge rates

within 3000 km of this location and also near the

magnetic conjugate location in the southern

hemisphere. There were quite active lightning storms

going on south and north of our Kentucky location

during the days we observed (I’ll say more about that

shortly). The conjugate hemisphere was not so

supportive; there were only two lightning discharges

during all the time we observed.

Figure 5: Projection-tent images of the partial solar eclipse are shown.

The picture is by Karen Edgett.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 21

While extensive observations were not possible, we did observe at this location on August 19 during sunset. We also observed

a few days later at mid-day, the eclipse time, and after sunset. In all cases, these observations were made at the same

location. Figure 6 summarizes our findings.

The average lightning discharge or flash rates are indicated in the upper right of the figure. Rates are number/sec and are

averaged over the full time interval of observations on each day. While there were somewhat more flashes within 3000 km on

the 19

th

, the rate of spherics that night and two days later during the mid-day eclipse are essentially the same. The red

horizontal bar on the 30 s

-1

grid line indicates the duration of the eclipse at our site, which was 2min 39.9sec. The plots of

these two rates suggest little difference between the two observing times and a possible trend, though more measurements

are needed to substantiate whether the downward trend means anything. The rise in the rate of tweeks after sunset is not

surprising. The suggestion that this rise mostly follows sunset by roughly 7 minutes may be the result of the ionosphere

entering Earth’s shadow later than a location below on the ground and continued rise may relate to the time scale of

ionospheric changes after entering Earth’s shadow.

Figure 6: Spheric and tweek rates are shown as time relative to the time of maximum totality and sunset. Blue is used for sunset

measurements on August 19 and red for mid-day measurements during the eclipse. Green is used to indicate the number of tweeks/min.

In all, it would seem that a longer period of totality might result in a measurable change in VLF noise. The longest totality time

for an eclipse is about 7 minutes. Not addressed by this near-zenith solar eclipse is the possible significance of the eclipse

elevation at the observing site. Some academic thought could be given to that question or… one could just travel to South

America next year to check VLF radio noise during another eclipse.

One final photograph is shown in Figure 7, even if it is not as spectacular as many taken of the Sun during totality. It was a first

totality photograph by Dennis Gallagher, another of our authors, that was taken with a Nikon D3300 camera using an Opteka

650-1300mm telephoto lens (1/125sec, ISO-200, RAW+JPEG). It is clear to Dennis that doing better photography is one of the

cravings that drive people to travel the world to see another and yet another of Nature’s spectacular shows.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 22

Figure 7: The Sun's corona during totality near Guthrie, Kentucky, USA. The picture is by Dennis Gallagher.

About Dr. Dennis Gallagher

Dr. Gallagher has worked for NASA Marshall Space Flight Center since 1984 doing research in space plasma physics. Dr.

Gallagher was the study scientist for the Inner Magnetosphere Imager Mission concept that was realized in the first selected

MIDEX Explorer mission, IMAGE, for which he was a Co-Investigator. He supported IMAGE mission planning and instrument

requirements definition for the Extreme Ultraviolet imager and the Radio Plasma Imager instruments and has participated and

led numerous studies of the measurements obtained by this first-ever magnetospheric

imaging mission. He continues to be involved in the development of thermal plasma

modeling and the study of IMAGE Mission observations.

Through the years at NASA Dr. Gallagher has led and supported a diverse variety of

studies including examination of the feasibility of using electrodynamic tethers at Jupiter

for orbital capture and maneuvering, for the viability of the concept of plasma

propulsion, for measuring the spin of individual dust grains suspended in an

electrodynamic trap in the Dusty Plasma Laboratory at MSFC, and for deriving the

electrostatic charging properties of radioactive dust as it decays and fissions in support

of developing a fission-fragment in-space rocket engine. From 2006 to 2011 Dr.

Gallagher served as Deputy and Acting Manager for the Space Science Office at NASA

Marshall Space Flight Center. Researchers performed research in Heliophysics,

Planetary Sciences, Space Weather, and Astrophysics. He has returned to primarily

scientific research following serving as manager of the Heliophysics and Planetary

Science Office from 2011 to 2013.

Dr. Gallagher serves as INSPIRE’s Chief Technical Advisor. Dennis answers The

INSPIRE Projects’ VLF kit user technical questions and updated INSPIRE’s VLF3-b Kit

Assembly Instructions in June of 2016. He has been actively involved with the

organization since it was founded in 1989.

Dennis at Eclipse-VLF field-site in

Guthrie, Kentucky – August 21, 2017

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 23

The “Peay’Clipse”

Experience: Scientists

from NASA, INSPIRE

and Austin Peay State

University study living

organisms during the

Great American Eclipse

Dr. Donald Sudbrink Jr.

Austin Peay State University’s Farm and Environmental Education

Center in Clarksville, Tennessee had the closest university

observatory to the greatest level of totality during the Great

American Eclipse of 2017. This APSU center hosted approximately

175 scientists, students and observers who participated in a wide

variety of eclipse-related research experiments during this

spectacular event. INSPIRE students were very enthusiastic and

integral in assisting the conduct of several experiments including

some with living organisms like cattle and insects. Several

presentations and abstracts have been generated from these

studies:

1.) Life at the “Peay’Clipse” and Beyond: Observations

on the behavior of several organisms in Tennessee and

adjacent states during the Great American Eclipse of 21

August 2017

Donald Sudbrink, Rodney Mills, Robert L. Moore, Emily Rendleman, John Fussell, Amy Wright, Mitzi Adams, Thomas Payne,

Lynn Faust, Hebron Smith and Stephen Smith. Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, Tennessee (DS, RM, RLM, ER, JF,

AW, HS and SS), NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama (MA), Woodlawn, TN (TP), Knoxville, TN (LF).

(Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Tennessee Academy of Science, Martin, TN Nov. 17, 2017)

Numerous organismal behaviors have been observed and recorded during previous total solar eclipses ranging from no-

effects to significant alteration of diurnal behaviors. To further investigate some of these phenomena during the Great

American Eclipse of 21 August 2017, a series of observations of behaviors of several species of organisms were taken in

Montgomery and Knox Counties in Tennessee, Todd County, Kentucky and Rutherford County, North Carolina. Behaviors of

several species of insects, reptiles, birds, mammals, and plants were observed during this event. While a few organisms

showed no effects near or during the totality of the eclipse, most observations indicated at least a temporary alteration of

typical diurnal behavior for each organism studied. Typical diurnal behaviors of organisms were observed to resume after

totality, albeit somewhat delayed in a number of species studied.

2.) The Sun, the Moon and the insects: Influence of the Great American Eclipse on selected observed

insect behaviors

D.L. Sudbrink, Jr.

1

, R.L. Moore

1

, E.D. Rendleman

1

, C.W. Galben

1

, A.M. Wright

2

, M.L. Adams

3

, T.E. Payne

4

and L.F. Faust

5

,

1

Department of Agriculture, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, TN,

2

Department of Languages and Literature, Austin

Peay State University, Clarksville, TN,

3

NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL,

4

Woodlawn, TN,

5

Knoxville, TN.

(Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Tennessee Entomological Society, Nashville, TN, Oct. 5, 2017)

The behaviors of numerous insect species have been observed and recorded during previous total solar eclipses ranging from

no-effects to significant alteration of diurnal behaviors. To further investigate some of these phenomena during the Great

American Eclipse of 21 August 2017, a series of observations of behaviors of several species of insects were taken in

Montgomery, Knox and Rhea Counties in Tennessee, Todd County, Kentucky and Rutherford County, North Carolina.

Behaviors of several species of insects including crickets, bees, cicadas, mosquitoes, butterflies and moths were observed

during this event. In the time near or during the totality of the eclipse, observations indicated at least a temporary alteration of

typical diurnal behavior for each species studied. Typical diurnal behaviors of species were observed to resume after totality,

albeit somewhat delayed in a number of species studied.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 24

3.) Total Eclipse of the Bees: Effect of Solar Eclipse on Apis mellifera

Emily Rendleman, Robert Moore, Dr. Donald Sudbrink, Dept. of Agriculture, Austin Peay State University.

(Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Tennessee Entomological Society, Nashville, TN Oct. 5, 2017)

Honey bees and other members of the family Apoidea have

been studied for many years, and one such subject area is that

of solar eclipses. Much of the data collected has been

anecdotal reports of honey bee behavior without much

quantified support. This experiment done during the August

21

st

, 2017 total solar eclipse attempted to marry the

quantitative and qualitative. Three hives of Apis mellifera were

observed between the hours of 11 AM and 4 PM, with records

being made of how many bees were present on the landing

boards. Results have shown dramatic differences in behavior

between that of a normal day and the period of totality.

Observed and counted bees at landing boards on hives

As totality approached, bees began rushing back to the hives

Clustered on landing boards and hive faces

Bees formed dark buzzing cloud, as if a hive had been dropped

Almost every bee was back in a hive by 12 min after totality

Didn't resume takeoffs until approximately ½-hour after totality

APSU Peay’Clipse at APSU Farm and Environmental Education Center

Don Sudbrink discussing insect behavior with students. Rod Mills assisting INSPIRE student with spray painting numbers on cows to track

behavior during the solar eclipse, while being filmed by NASA-TV

Overview

Official NASA site, live worldwide on NASA-TV and C-SPAN

Astronomers, Solar Physicists and Atmospheric scientists from APSU, NASA and other institutions ran a battery of physical

science experiments

65 Students from NASA Space Camp and INSPIRE came to Clarksville for a research education experience

Objectives

Help NASA students study animal behaviors before, during and after the eclipse in the eclipse zone

Observe and record male cricket calling and other behaviors

Observe and record honeybee behaviors

Compile observations of behaviors of other insect species from collaborative observers in the zone of the eclipse

!"

#!"

$!!"

$#!"

%!!"

%#!"

&!!"

$!&!" $$&!" $%&!" $&&!" $'&!" $#&!" $(&!"

!"#$%&'(%)*#)*"+,-."/0*1,*2"3)0415"%$"672"%!$8"

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 25

Snout butterfly on INSPIRE Educator

Chris Stephens prior to the eclipse

Materials and Methods Observation Locations in TN, KY & NC

Collaborative Observations

Montgomery Co., TN (totality = 2min. 18 sec.)

Field crickets were observed to chirp at totality

Calling cicada species changed

a) one species called before totality

b) another species called during totality

c) previous species returned to call after totality

Mosquitoes bit NASA researcher at APSU Farm during totality

Four butterfly species recorded on butterfly-bushes before totality

Monarch, Tiger swallowtail, Pipevine swallowtail, Painted lady-disappeared

Honeybees raced back to hive and stayed inside for 1 hour

Barred owls called at totality

Todd Co., KY (totality = 2 min. 30 sec.)

Snout butterflies swarmed and lit on sweaty NASA INPSIRE participants at

field study site before eclipse. Disappeared at totality, but returned

approximately ½ hour later.

Moths flew at totality, but did not fly afterwards.

Chickens returned to their coop and stayed for ½ hour

Knox Co., TN

Male fireflies (Photinus pyralis), flashed near-totality

Lynn Faust et al. will publish a scientific note on firefly study soon in

Entomological News

Calling cicada species changed over

a) one species called before totality

b) another species called during totality

c) previous species returned to call after totality

Field crickets chirped at totality

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 26

Percentage of active/chirping male

Acheta domesticus, 21 AUG 2017

!"

#!"

$!"

%!"

&!"

'!"

(!"

##!!" ##'!" #$!!" #$'!" #%!!" #%'!" #&!!" #&'!" #'!!"

)*+,"

Collaborative Observations continued

Rhea Co., TN

Field crickets were observed to chirp at totality

Rutherford Co., NC

Honeybees raced back to hives at 99.7%

eclipse

Stayed in hives for more than ½ hour

Cricket Study – APSU Farm EEC

Ten fresh male Acheta domesticus were each placed

in cages

Behaviors: chirp, explore, jump, climb, groom, and

resting

Prior to eclipse, A. domesticus observed in resting

mode

Five minutes before totality, 20% started to chirp

At totality, 50% of crickets chirped and/or actively

explored containers

Crickets stopped chirping at totality’s end and

remained in resting mode for duration

Space Academy students observe cricket behavior before, during and after the

total solar eclipse at APSU farm.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 27

Turtle Observations – APSU Farm EEC

Plant Observations – APSU Farm EEC

Number of Trachemys scripta on

pond bank, 21 AUG 2017.

!"

#"

$!"

$#"

%!"

%#"

&!"

&#"

'!"

'#"

$&!!" $&#!" $'!!" $'#!" $#!!"

()*+"

% Cucurbit floral closure

Guthrie, KY. 21-AUG-2017

!"

#!"

$!"

%!"

&!"

'!"

(!"

)!"

*!"

+!"

#!!"

##)'" #$!!" #$$'" #$'!" #$)'" #%!!" #%$'" #%'!"

,-"./01232/3" 4-"56.07383" 4-"539"

:";<623<"4<6.=21"

>/51"?4@>A"

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 28

Cattle Observations – APSU Farm EEC

Dr. Rod Mills reported that one cow went out to graze during totality and returned.

SUMMARY

A series of organismal behaviors was observed during

the Great American Eclipse in TN and adjacent states

including mammals, birds, reptiles, insects and plants

Several species altered their typical diurnal behaviors

Honeybees returned to hives at totality and stayed

inside for at least ½ hour

Crickets - 50% of Acheta domesticus males were

chirping and or active during totality, but returned to

resting shortly after eclipse

Cucurbit flowers had closed by totality and remained

closed

Only one cow went to pasture and grazed at totality

About Dr. Donald Sudbrink Jr.

Dr. Donald L. Sudbrink Jr. is Chair of the Department of Agriculture at Austin Peay State

University and runs their Farm and Environmental Education Center where, each year, he

hosts the Summer Science and Math Academy for high school science students.

He received his B.S. in Entomology-Plant Pathology from The University of Delaware, and

M.S. in Entomology and Plant Pathology from The University of Tennessee. Dr. Sudbrink

received his Ph.D. from Auburn University in Entomology.

Dr. Rod Mills discusses cow behavior with Space Camp and

INSPIRE students in the Environmental Education Center

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 29

The Boy Who Noticed the Watermelon Flowers

Dr. Amy Wright – Austin Peay State University Professor, Writer

The coming shadow pushes a

welcome breeze under the ninety-

six-degree air before it. NASA

researchers, joining others

positioned across the eclipse path

from Oregon to South Carolina,

launch their last two balloons. They

swell before a news crew like Lady

Liberty’s blown bubblegum, with

boxes in tow to gauge air-pressure

and temperature in the Martian-like

atmosphere of the stratosphere.

One also hefts a camera. The other

dangles microbes found living like

barnacles outside the International

Space Station. A balloon released

that morning had failed. When we

see the second parachute open and

a tail of boxes sail down in the

distance, Douglas, a team leader,

says: “Good thing they didn’t catch

that on film,” since the C-Span

reporters have turned their attention

elsewhere.

I am surrounded by twelve- to sixteen-year-olds who use words like “declination” in casual conversation. NASA’s live feed is

being shot from the astronomical observatory on our university’s working farm and environmental center, and I volunteered to

help INSPIRE and NASA Space Camp students journal their experience.

Some of the students are monitoring beef cattle to see if they

leave the shade of the trees when the sky darkens. Others,

which entomologist Don Sudbrink calls “The Cricketeers,” are

marking boxes of male crickets to determine if they call for

females, or chirp, during totality as they normally do at night.

Beekeepers Bob Moore and Emily Rendleman are setting up a

station by the beehives to see how honeybees respond since

they navigate by the Sun.

The ancient Chinese blamed a dragon for devouring the Sun,

so the Chinese word for eclipse is chih, to eat, but I wait my

turn at the telescope in a wheel of chatting people as if feeding

coins in for a peep show. The Sun being taken by this dark

body is public as a mall poster of tantric union, Sparshavajrā’s

head thrown back in abandon. I scrutinize each meeting point,

under magnification.

When the last gleaming crevice between them squeezes shut,

we tear off our shades and fill our eyes. A chorus of shouts

goes up. In one 1,450-m.p.h. wave the Moon’s shadow has

stranded islands of people in a sea of evenfall. “Where in your

body do you feel awe?” I had asked students earlier, “Your

stomach? Toes?” My cheeks stream with tears, exposed

emulsion paper dipped in a silver bath.

Skin tones glow indigo and a kit of rock doves swoops

overhead. The corona flexes and flails, wild haired behind the

curtained spotlight. I turn and scan the horizon, the only

celestial modesty for 360 degrees its downcast lavender lid.

Photo courtesy of The INSPIRE Project

Photo courtesy of Gregory “Slobirdr” Smith

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 30

When the Sun reemerges flushed and

bright-eyed, solar physicist Mitzi Adams

wastes no time assembling observations

from these two minutes and eighteen

seconds none of us alone can

comprehend.

“I had to step back ten feet,” says Emily,

“The bees were jostling each other off the

hives’ landing strips, buzzing in agitation

rather than their usual hum.”

“At least two mosquitoes came out,”

according to Mark pointing to stings.

The Cricketeers report that four boxed

crickets sung and were joined by more in

the wild. They also saw fifteen then

twenty, then forty eastern sliders pop out

of the pond to bathe in the twilight. One

cow began grazing, Rod notes. Masu

saw a crow change flight.

“The plants think it’s a new day,” José says, having

seen the watermelon flowers, which open for one

day only, close when the temperature and light fell.

He was not surprised that they did not reopen,

because he raises his own watermelons as well as

peas, pumpkins, and chilies. The female flowers

had had their morning. They unfurled yellow

petals, beckoned honeybees in ultraviolet radiance

to their swollen stamen, and waited. Grains of

pollen dropped and clung to the lucky ones. For

the others, it was over. The chance had passed by

them like an empty hand. Providing our only plant

observation, José was the first person to document

that phenomenon.

“He’s exceptional,” we agree at dinner.

As is this planet, optical physicist Phil Stahl

explains: “Without the Moon’s sway, Earth’s

distance from our G-class star would not have

been enough to evolve life.” The ebb and flow that

the Moon generates pulls the ocean into rock

shallows, which the Sun warms. It is a recent observation about the importance of tidal pools, he adds, but it makes sense that

marooned until high tide species have long teemed together and schooled each other, leaving each one better for it.

I picture Spring Break hot tubs. For all our mathematical abilities to predict eclipses until this Saros series, or season, ends in

3009, we are testaments first to hot-bloodedness. The animal scientists, whose own circadian rhythms have been jangled by

eclipse fervor, will soon head back to their fields and laboratories to rejoin those creatures who low and call to each other.

Those members of our cohort who will pore tomorrow over footage of solar winds and magnetic fields recognize the

remarkable nature of this conjunction. Those who will commence mapping the universe appreciate the odds not for life but

those against it. In the midst of political discord and ecological turmoil, they wonder at the

billions of years that have led to this alignment. Kind of makes a person want to nuzzle up to

a loved one, the star-studded sky above this habitable zone nothing short of expectant.

About Dr. Amy Wright

Amy Wright is the author of Everything in the Universe, Cracker Sonnets, and five

chapbooks. She also co-authored Creeks of the Upper South, a lyric reflection on

waterways and cultural habitats. Her writing has been awarded two Peter Taylor

Fellowships for the Kenyon Review Writers’ Workshop, a fellowship to the Virginia Center

for the Creative Arts, and an Individual Artist’s Fellowship from the Tennessee Arts

Commission. Amy Wright is a Professor and the CECA Coordinator for Creative Writing

at Austin Peay State University.

Photo courtesy Sean McCully of APSU

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 31

Austin Peay State University – Clarksville, TN

INSPIRE Space Academy Alumni Students’

Total Solar Eclipse Experience & Observations

Eva Kloostra, INSPIRE Program Manager

Since the launch of INSPIRE’s Space Academy for Students program ten years ago, it has been a dream of mine for the

elementary and middle school students who received scholarships to attend the weeklong STEM program to have a similar

opportunity as high school students to further reinforce his or her STEM education and future career path. This dream became

a reality for 12 amazing alumni students in August 2017. Mitzi Adams and Dennis Gallagher of NASA Marshall Space Flight

Center invited INSPIRE’s alumni students to participate in hands-on field research before, during and after the total solar

eclipse at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee. The INSPIRE Project sincerely thanks Mitzi and Dennis for

everything they did to provide the students with this truly once-in-a-lifetime STEM opportunity. INSPIRE would also like to

thank our generous donors, volunteers, dedicated parents, and the countless NASA and Austin Peay State University staff

who helped to make this program possible. A special thanks to Kathrine Bailey at APSU and Jacquie LaPergola for their

endless assistance with INSPIRE’s travel and housing logistics.

After months of anticipation, on Friday, August 19

th

INSPIRE’s students arrived at Reagan National Airport in

Washington, DC to embark on a STEM experience of a

lifetime. Though the team was ready for lift-off unfortunately

the airline was not. They informed our chaperones that the

students’ flight was cancelled and they could not get them

on another flight to Tennessee until Monday due to the

number of cancellations. Fortunately one of the student’s

parents, Beverly and James Thomas, had a personal

contact with a charter bus company and 3 hours later the

INSPIRE team was en route to Clarksville.

The students arrived early Saturday morning at Austin Peay

State University and got settled in their dorm rooms, which

provided them with a college-life experience. After breakfast

at the university dining hall, the group was off to the Austin

Peay Environmental Center and farm.

Students at Reagan National Airport with volunteer Robin Houston

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 32

NASA’s Mitzi Adams developed the total solar eclipse

program agenda with Austin Peay staff that included the

following interactive presentations at the farm on

Saturday and Sunday:

Journaling and Science Writing – Dr. Amy Wright

Overview of Eclipse – Mitzi Adams

Insects Likely to be Affected by the Eclipse –

Dr. Donald Sudbrink Jr.

Animals Likely to be Affected by the Eclipse –

Dr. Rod Mills

Photosensitivity and Behavior of Plants – Dr. Carol

Baskauf and Josh Kraft

Solar Viewing and Citizen CATE – Dr. Allyn Smith,

Mitzi Adams, Dr. Spencer Buckner &

Dr. Dennis Gallagher

INSPIRE and VLF Radio – Dr. Dennis Gallagher

Biological Changes Associated with Rapid Light

Intensity Reduction – Dr. Karen Meisch

Atmospheric Science Experiments – Dr. Pete

Robertson

Shadow Bands – Dr. Phil Stahl

After learning about the various eclipse research

projects via the on-site presentations combined with a

series of interactive online presentations that the

students participated in during the months prior to the

eclipse, students selected which research project they

wanted to join based on his or her interest.

The students returned to campus for dinner and then

were off to the secondary eclipse research site – a

soybean farm in Guthrie, Kentucky 30 minutes away.

Due to its remoteness and distance from power lines,

the soybean farm site was used to conduct very low

frequency (VLF) natural radio observations using the

INSPIRE VLF receiver before, during and after the

eclipse. Dennis Gallagher provided the students with an

overview of the receiver and they participated in hands-

on observations and experienced the sounds of space

firsthand.

On Sunday morning, INSPIRE’s Board President Phillip

Webb arrived with his three oldest children to join the

INSPIRE team. Dr. Rod Mills asked INSPIRE’s students

to assist his research team by spray painting numbers

on the APSU cows at the farm so they could be tracked

during the eclipse. NASA-TV filmed the students and

the footage aired for several days as part of NASA’s

total solar eclipse national coverage.

Later that morning, the students from the U.S. Space &

Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama who were also

invited to participate in the solar eclipse research arrived

at the farm. All of students had the opportunity to view

the sun through the NASA and APSU telescopes and

the remaining presentations were held.

After a full day at the farm, the students returned to

campus for dinner followed by a presentation by NASA

astronaut Rhea Seddon at APSU’s Dunn Center and a

multimedia presentation on the outside of the center

entitled “Launch” which simulated the space shuttle

launching.

NASA/MSFC’s Mitzi Adams presenting an Overview of the Eclipse to

students at APSU’s Environmental Education Center

NASA/MSFC’s Dennis Gallagher at soybean farm in Guthrie, KY

conducting VLF observations with the INSPIRE team Saturday at dusk

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 33

On Monday morning, aka “Eclipse Day”, there was not a

cloud in the sky. Excitement filled the entire town of

Clarksville, Tennessee and the population doubled in a

matter of hours. After breakfast, INSPIRE’s students broke

off into two groups. Five of the students travelled with

Dennis Gallagher and INSPIRE’s chaperone Karin Edgett

to the soybean farm in Guthrie and the other seven

students went with Mitzi Adams to the APSU farm.

When our group arrived at the farm, the students began

working on their research projects after a final review on

safely viewing the eclipse. There were camera crews

everywhere and NASA-TV was broadcasting live. This

serene farm was now full of energy from enthusiastic

spectators. Only a few hours until the big event.

In the first classroom presentation on Saturday on the topic

of Journaling and Science Writing, Dr. Amy Wright

encouraged the students to be aware of all five of their

senses during the eclipse and not just focus on sight. As you

will read in the student observations, the total solar eclipse

touches all of your senses and was truly spectacular.

At the end of the day, the students were reunited for an

INSPIRE celebration dinner to compare their experiences.

The next morning the students arrived at Nashville airport to

learn that once again their flight had been cancelled

(really!). Fortunately, they safely returned home the

following day via another flight and got to spend a fun day in

Nashville. At the airport, they ran into NASA astronaut Mark

Kelly and his wife Gabby Giffords who posed for a photo

with them – a perfect ending to a once-in-a-time experience

for 12 extraordinary DC high school students.

INSPIRE students at the Nashville airport with NASA astronaut

Mark Kelly and his wife Gabby Giffords

(Left) INSPIRE students Nile, Joshua and Robert viewing the eclipse

Eclipse photo courtesy of APSU’s Hunter Abrams

Mitzi Adams (center) with APSU staff at INSPIRE’s total solar eclipse

celebration dinner on Monday night

INSPIRE students at APSU the morning of the total solar eclipse

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 34

INSIPRE Student Observations: Soybean Farm – Guthrie, KY

Total Solar Eclipse 2017 – Charis Houston (11

th

Grade)

Rows of soybeans, stretching miles across the horizon, was the backdrop

for one of the most incredible experiences in the past thirty-eight years. It

has been thirty-eight years since the US has seen a total solar eclipse and

will be seven years before another one crosses the country. The mood of

the handful of expectant researchers and viewers standing knee deep in

bean plants was…jubilant!

The soybean field was the best place to see the eclipse because it was

isolated from where a majority of the people would gather to see the eclipse.

It was also far enough from power lines that the experiment, which dealt with

very low frequencies, could be conducted without electrical interference. The

experiment was important because it was designed to see when lightning

bolts strike, whether or not it would be heard. The best time to normally hear

the lighting is between nighttime and dawn. The experiment focused on a

specific radio channel from Colorado that is typically heard in the evening to

see if it could be picked up during totality. Sadly, that radio channel was not

heard.

The moment the moon first touched the sun was hardly noticed. None of the

animals or people reacted; the scene, still was “daytime.” As the moon

Five INSPIRE’s students participated in hands-on research before, during and after the total eclipse with Dr. Dennis Gallagher of NASA

Marshall Space Flight Center on a local farmer’s soybean farm. This remote location was selected to conduct VLF observations using the

INSPIRE receiver to avoid interference from power lines. Pictured left to right: Isadora Germain, Clark Gray, Destiny Frink-Morgan, Charis

Houston and Colby Gray

On Saturday evening prior to the eclipse, Dennis

Gallagher set up the INSPIRE VLF receiver to conduct

observations at sunset with the INSPIRE team. Charis

and chaperone Chris Stephens pictured with Dennis.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 35

began to displace the sun, some of the insects started to quiet down and go back into the bean fields where they live. When it

was 10 minutes from totality, the scenery outside was almost as if color itself from the plants and trees was draining into this

grayish hue. It was as if color itself was melting away when the moon was getting closer to blocking the sun.

The excitement of watching the eclipse eclipsed the ability to focus on the monitor that picked up the frequencies once the

moon moved into place. It was as if time itself had stopped. The murmurs of the people standing around, watching the eclipse,

becoming at once…silent. The crickets and other insects were no longer making noise. In totality, the area looked like a scene

from the Twilight Zone. With a 360° sunset, it felt unreal as if it were a dream. During this time, the only animals/insects that

were out were butterflies, which was very odd.

There was a period of identifying all the different phases of the eclipse. Someone blurted out “The Diamond Ring” phase and

the group whooped in awe. The six-day trip can be summed up in two minutes and 40 seconds. The experience of a lifetime

that will never be forgotten nor eclipsed by any other events in nature!

2017 Total Solar Eclipse in Kentucky – Clark Gray (11

th

Grade)

We arrived at the soybean field study site in Kentucky and it was

extremely hot, but exciting. Once there, we quickly set up camp. We

then proceeded to make holes in a sheet for the viewing of mini

eclipses. We also set up the communications pole to observe radio

frequencies during the eclipse.

After we set up, we frequently looked up at the moon's progression to

the sun. While we waited, we looked at the sun through telescopes

and took pictures. I found the paper viewing glasses to be ineffective

as they would not fit over or under my regular eyeglasses so, I

fashioned DIY goggles by taping welder's glass to my regular

eyeglasses.

While observing the local insects and animals, we noticed birds flying

in large swarms and the crickets coming out of hiding. The sun

stayed very bright up until about 10 minutes before totality. Right

before totality, all around us the colors began to dull, becoming

greyish. By this time, our camp was being visited by local farmers

and passersby. We struck up conversation and told them why we

were here and what we were doing. They were very impressed and

even took pictures with us NASA scientists. During totality, the view

was an absolutely beautiful 360 degree sunset. During this time,

several people sang the song “Our God is an Awesome God”. People

were taking videos and pictures and walking around in awe. We took

more observations and then about an hour after totality, we packed

up and left.

Isadora Germain (12

th

Grade)

It was an honorable death. The last burst of light escaped

from behind the Moon and the Sun finally closed its massive

eye. My eyes adjusted and I was on an entirely different

planet. An earthquake grew up from my feet, into my hands,

and out through my eyes. The tears formed almost as if

they wanted to witness the event for themselves. It felt like

being underwater, but at the same time taking my first

breath of fresh air. My other senses shut off, opening my

eyes to new colors, sensations, and emotions. Left in place

of the Sun was the deepest shade of black I had ever seen.

The halo of light around it throbbed like my heart was

racing, bringing new life to the solar system around me. I

had found extraterrestrial life, but not in the way most

people would think. For two minutes and 39 seconds, the

moon was more alive than ever. She had a pulse. She had

hands. She was grasping onto our thin atmosphere in a

struggle that left rich shades of orange and red all around

the horizon. I was witnessing a hello. I was witnessing a goodbye. All of a sudden, the bright and familiar warmth was back.

The Sun took back its throne and the Earth began to rotate again.

The INSPIRE Journal | Volume 23 | Winter 2017/Spring 2018 36

Only in America - 2017 Eclipse – Colby Gray (10

th

Grade)

I was really glad to be selected by The INSPIRE Project for this

once-in a-lifetime opportunity to view the solar eclipse in the path

of totality from a Kentucky soybean farm. It was amazing and

something very difficult to put into words.

Austin Peay, the university which hosted the INSPIRE group was

where we had our presentations to decide which group we wanted

to do research in. The options were observing the beef cattle’s

activity, observe the insects and observe totality from a Kentucky

soybean farm. From the 12 of us, 5 of us went to the farm.

There we set up all the equipment for viewing the eclipse, such as

the radio wave station, which was a frequency pole to measure

the sound of lightning and other natural occurrences. We also

created a tent with a tarp on top with holes poked in it so we could

see the shadow bands during the different stages of the eclipse.

Moments before the “Diamond Ring” effect, we could experience

the environment transforming into a quiet dream setting with a

360° sunset. It was like nothing I’ve ever seen.

When I felt the temperature start to drop I knew it was seconds

away, coming and disappearing as quickly as a fiddler on the roof.

During totality we took off our glasses and viewed the monstrosity

that is the moon covering the sun for two and a half minutes. As

our very limited time came to an end, we put our glasses on and