Targeting scams

April 2023

Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

ii

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

Ngunnawal

23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601

© Commonwealth of Australia 2023

This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence, with the exception of:

the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

the ACCC and AER logos

any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold copyright, but

which may be part of or contained within this publication.

The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 4.0 AU licence.

Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Corporate Communications, ACCC, GPOBox 3131,

Canberra ACT 2601.

Important notice

The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied

on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You should obtain

professional advice if you have any specic concern.

The ACCC has made every reasonable effort to provide current and accurate information, but it does not make any guarantees regarding the

accuracy, currency or completeness of that information.

Parties who wish to re-publish or otherwise use the information in this publication must check this information for currency and accuracy prior to

publication. This should be done prior to each publication edition, as ACCC guidance and relevant transitional legislation frequently change. Any

queries parties have should be addressed to the Director, Corporate Communications, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601.

ACCC 04/23_23–18

www.accc.gov.au

Acknowledgment of country

The ACCC acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians of Country throughout

Australia and recognises their continuing connection to the land, sea and community. We pay

our respects tothem and their cultures; and to their Elders past, present and future.

iii

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Foreword

This report is the 14th annual Targeting Scams report. It provides insight into scams that impacted

Australians in 2022 and some of the activities by government, law enforcement, the private sector

and community to disrupt and prevent scams.

Despite these activities, losses to scams have increased signicantly in recent years. The combined

losses reported to Scamwatch; ReportCyber; the Australian Financial Crimes Exchange, IDCARE,

ASIC and other government agencies was at least $3.1 billion in 2022. This is an 80% increase on

total losses recorded in 2021.

There are many statistics in this report. Behind the numbers are everyday Australians who

lost money, sometimes their life savings to scams. Some experience life changing impacts to

relationships and health. By responding to a fraud alert call they thought was their bank; clicking

on a link in a text message they thought was from a government agency; signing up to a promising

scheme to invest their retirement savings or transferring their property settlement funds into a bank

account listed in an email they thought was from their lawyer – these people never expected they

could lose everything.

The losses are increasing because scams are harder to spot, and anyone can be caught. Leveraging

emerging technology, scammers impersonate the phone numbers, email addresses and websites

of legitimate organisations. Their text messages can appear in the same conversation thread as

genuine messages. Fake ads, social media proles and reviews are easily, and cost effectively

deployed. This makes scams incredibly dicult to identify.

In 2022, more people reported losing money and the amount of money they lost increased, with

average losses up 54% to almost $20,000. These can be life-changing losses and for most people,

the process of recovery from a high loss scam is long and dicult. Many don’t report scams or seek

help at all.

More coordinated effort is required across government, the private sector and law enforcement to

combat scams. Businesses need to be vigilant and implement effective monitoring and intervention

processes to prevent scammers using their services and stop them when they do. Identity,

verication and communication processes need constant review as scammers constantly evolve.

We need to arm consumers with the tools to give them the best chance to identify scams, whilst

recognising that humans aren’t going to stop being human any time soon.

Many countries are facing similar challenges with escalating levels of fraud against individuals. There

are solutions in other jurisdictions that could mitigate some of the scam losses in Australia. The UK

bank initiative to match BSB and account number to the intended recipient is one example. The SMS

SenderID registry in Singapore is another. Measures such as these help make systems safer. We are

encouraged to see exploration of opportunities like these but there is more work to be done to ensure

that scammers do not nd the weakest links.

This year there is some reason to be optimistic. The government made a commitment in 2021 to

implement anti-scam measures and provided seed funding to the ACCC to establish a National Anti

Scam Centre. The Centre will bring together government, regulators, industry, and consumer groups

to leverage our collective expertise to share intelligence, disrupt scams, empower consumers, and

nd real solutions to reduce the losses to scams. It will aim to integrate not duplicate existing efforts

and build on them.

iv

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

But it is going to take genuine effort, resources, and collaboration. There is a real opportunity for

business to lead the way by implementing meaningful change that has real and effective outcomes

for Australians. Minimum standards will also be required to ensure that gaps between institutions,

industries or regulators aren’t there to be exploited. Put simply, we need solutions that stop

scammers reaching consumers and makes it harder for them to get access to money from the bank

accounts of ordinary Australians.

I would like to thank all of the organisations that provided data for this report and those that have

collaborated throughout the year on many scam prevention and disruption initiatives. I’d also like to

thank all of the people who work hard to protect Australians from scams. While the gures in this

report are sobering, there are many Australians who have avoided scams or received assistance to

recover because of the perseverance and ongoing work of government, law enforcement, consumer

organisations, support services and the private sector throughout 2022.

Catriona Lowe

Deputy Chair, ACCC

v

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Contents

Foreword iii

The role of Scamwatch 1

Notes on data in this report 2

Targeting scams 2022 3

How to protect yourself from scams 5

1. Scam activity in 2022 6

1.1 Key statistics 2022 6

1.2 The contact methods 6

1.3 The payment methods 6

1.4 The people who lost money 7

1.5 The businesses which lost money 7

1.6 The ght against scams 7

2. Combined data – the bigger picture 10

3. Scamwatch trends in 2022 11

3.1 Australians reported signicant losses to investment scams 11

3.2 Phishing was the most reported scam and caused signicant losses 13

3.3 Young people losing money to employment scams 17

3.4 Older Australians losing money to remote access scams 18

3.5 Reports to Scamwatch decrease 16.5% 19

4. The people reporting scams 20

4.1 The demographics 20

4.2 Scams affecting Indigenous Australians 22

4.3 Scams affecting culturally and linguistically diverse communities 23

4.4 Scams affecting people with disability 24

5. Law enforcement activity to combat scams 27

6. Glossary links 29

6.1 Scam terms and categories 29

1

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

The role of Scamwatch

Scamwatch (www.scamwatch.gov.au) is run by the Australian Competition and Consumer

Commission (ACCC). Established in 2002, its primary goal is to make Australia a harder target for

scammers. To achieve this, we raise awareness about how to recognise, avoid and report scams. We

also share intelligence and work with government, law enforcement and the private sector to disrupt

and prevent scams.

Many people who report to Scamwatch are not victims of scams. The reports of non-victims provide

useful intelligence that helps us warn the public about emerging scams. The 2021 Targeting Scams

Report was viewed 9,371 times and downloaded 4,939 times.

2

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Notes on data in this report

The data in this report is from the calendar year 1 January to 31 December 2022. All case studies are

adjusted to protect the privacy of reporters.

Except where specied, all data is based on phone and web reports made to Scamwatch. Scamwatch

data may be adjusted throughout the year because of quality assurance or changes to categories.

While effort is made to verify high loss reports, reports are unveried.

Reference to combined reports or losses include data from Scamwatch, ReportCyber, IDCARE,

the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC), the Australian Communications and

Media Authority (ACMA), the Australian Taxation Oce (ATO), Services Australia, and the Australian

Financial Crimes Exchange (AFCX). This report was prepared earlier in the year than other years

which made it dicult for some organisations to contribute data. We added data from IDCARE and

used the AFCX data to represent the nancial sector. Combined loss data does not include some

banks and money remitters that were included in 2021. Some government agencies were also unable

to provide data. ReportCyber and ASIC data has been adjusted to remove many high loss reports.

Many people now pay scammers via cryptocurrency but we have not obtained scam loss data from

cryptocurrency exchanges. Given the challenges in attempting to de-duplicate the varied sources of

data, and in recognition of the fact that many losses have not been included, we have not adjusted the

data for duplication. We also note the ACCC’s previous research that shows that only 13% of scam

losses are reported to Scamwatch and over 30% of people do not report scam losses at all. As such

we are of the view that actual scam losses in 2022 are more likely to be well above the combined

losses of $3.1 billion.

We thank all contributing organisations for their participation and cooperation in the production of

this report.

3

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

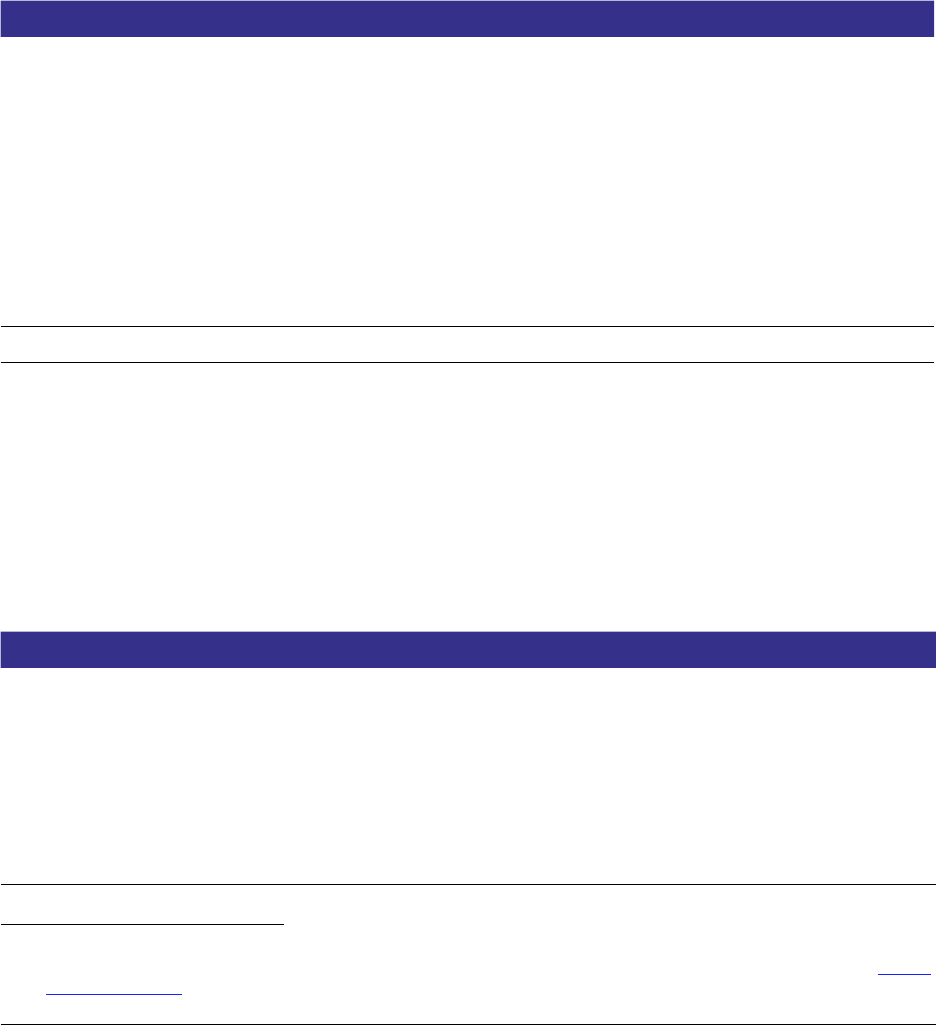

Targeting scams 2022

Losses

239,237

reports to Scamwatch

$569 million

Amount reported lost to

Scamwatch

224% since 2020

76%

16.5%

2020

$176 m

2021

$324 m

2022

$569 m

Top contact methods

Average loss: $19,654

29%

Phone

63,821 reports

$141 million

reported lost

33%

Text message

79,835 reports

$28 million

reported lost

22%

Email

52,159 reports

$77 million

reported lost

6%

Internet

13,692 reports

$74 million

reported lost

6%

Social networking/

online forums

13,428 reports

$80 million

reported lost

268,622 reports in 2021

$3+ billion

Total combined losses reported to Scamwatch, ReportCyber,

IDCARE, Australian Financial Crimes Exchange (AFCX) and

government agencies.

4

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Top scams by loss as reported to Scamwatch

Age

Investment scams

$377 million

1

Dating &

romance scams

$40 million

2

False billing

$24 million

3

Phising

$24 million

4

Remote

access scams

$21 million

5

Threats to life,

arrest or other

$13 million

6

Identity theft

$10 million

7

Jobs &

employment

scams

$9 million

8

Online shopping

scams

$9 million

9

Classified scams

$8 million

10

Reports

Losses

0.8%

5.6%

14.6%

17.6%

17.5%

17.4%

25.5%

0.1%

3.4%

12.1%

19.3%

18.6%

21.0%

26.4%

Under 18

Losses: $360,000

Reports: 1,550

18–24

Losses: $16 m

Reports: 10,508

25–34

Losses: $57 m

Reports: 27,281

35–44

Losses: $91 m

Reports: 32,735

45–54

Losses: $88 m

Reports: 32,639

55-64

Losses: $99 m

Reports: 32,367

65+

Losses: $120 m

Reports: 49,163

5

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

HOW TO PROTECT

YOURSELF FROM

SCAMS

STOP – Don’t give money or personal information to anyone if unsure.

Scammers will offer to help you or ask you to verify who you are. They will pretend to be

from organisations you know and trust like, Services Australia, police, a bank, government

or a fraud service.

THINK – Ask yourself could the message or call be fake?

Never click a link in a message. Only contact businesses or government using contact

information from their ocial website or through their secure apps. If you’re not sure say no,

hang up or delete.

PROTECT – Act quickly if something feels wrong.

Contact your bank if you notice some unusual activity or if a scammer gets your money or

information. Seek help from IDCARE and report to ReportCyber and Scamwatch.

Scamwatch

www.scamwatch.gov.au

IDCARE

1800 595 160

www.idcare.org

ReportCyber

www.cyber.gov.au

1. Beware of anyone offering you easy money through

investment or a job. Visit moneysmart.gov.au to avoid

investment scams.

2. Check invoices and bills before paying, by

independently calling the business on the publicly

listed number.

3. Add steps to show who you are when you log into

your online services. This could be a code sent to

your phone, a token, a secret question or your face

or ngerprint.

4. Never provide information, passwords, or codes over

the phone or via text to anyone. Contact government,

businesses, and banks through ocial channels.

5. Immediately report any suspicious activity to

your bank.

6. If you need crisis services or emotional support,

contact Beyondblue 1300 224 636 or Lifeline on

13 11 14.

What you can do to protect yourself today:

6

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

1. Scam activity in 2022

1.1 Keystatistics2022

Scamwatch, ReportCyber, the Australian Financial Crimes Exchange, IDCARE, the Australian

Securities and Investment Commission, and other government agencies received a combined

total of over 500,000 reports, with reported losses of over $3.1 billion in 2022.

Investment scams caused the most nancial loss, with combined losses of $1.5 billion. This was

followed by remote access scams with $229 million lost, and payment redirection scams

1

with

$224 million lost.

Scamwatch received 239,237 reports, a 16.5% decrease from the 286,622 reports received

in 2021.

Financial losses reported to Scamwatch increased by 75.9% and totalled more than $569 million

in 2022.

28,980 people (12.1%) reported a nancial loss. 64,881 people (27.1%) reported loss of personal

information. Those who reported a loss to Scamwatch suffered an average loss of $19,654. This

was an increase of 54% from the average loss of $12,742 in 2021.

30% of victims do not report scams to anyone, so the actual losses are far higher. Only 13% of

victims report to Scamwatch.

1.2 Thecontactmethods

Text message surpassed phone call as the most reported contact method in 2022.

79,835 people reported receiving scam text messages, an increase of 18.8%.

Reports about scam calls decreased 55.9% to 63,821.

Scam calls resulted in the highest reported losses increasing by 40.6% to $141 million.

Social media was the next highest in terms of reported losses increasing by 43% to $80.2 million.

1.3 Thepaymentmethods

Bank transfer remains the most reported payment method with 13,098 reports totalling

$210.4 million. Losses by bank transfer increased 62.9%.

3,910 people reported cryptocurrency as the payment method, an increase of 162.4% with

$221.3 million

2

reported lost.

People who lost money via bank transfer were more likely to have been contacted by phone

or email.

People who lost money via cryptocurrency were more likely to have been contacted via social

networking or mobile app.

Reported losses where credit card was the payment method increased 40% to $12.1 million.

1 These scams are also known as business email compromise.

2 Removing signicant loss outliers, cryptocurrency losses increased 90.2% to $160.6 million.

7

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

1.4 Thepeoplewholostmoney

Older Australians continue to lose more money than other age groups. People aged 65 and

over made the most reports (49,163) and lost more money than any other age group with

$120.7 million reported lost (an increase of 47.4%).

People aged 35–44 reported the highest increase in reported losses up 90.7% to $91.2 million.

Men reported losses of $273 million (43.5% increase) while women reported losses of

$231.5 million (76.5% increase). Women made 120,418 reports and men made 112,975 reports.

Indigenous Australians made 1.63% of all reports (3,889) and reported $5.1 million in losses (an

increase of 5.3%). The average loss was $8,123 and the median loss was $754.

People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities (CALD) made 11,418 reports and

accounted for 9.94% of total reported losses ($56.6 million). The median loss for CALD reporters

increased 20% to $1,435 and the average loss was $24,330.

People with disability made 16,473 reports with reported losses of $33.7 million (5.9% of all

losses). The median loss was $900 and the average loss was $18,024.

1.5 Thebusinesseswhichlostmoney

Businesses submitted 3,857 scam reports in 2022 with reported losses of $23.2 million.

Small and micro businesses

3

reported losses of $13.7 million across 2,019 reports.

Small and micro businesses were more likely to report losses to phone or email scams and the

payment method ($10.8m) was mostly bank transfer.

Businesses that reported losing the most money were in NSW ($6.5m) and Queensland ($6m).

1.6 Thefightagainstscams

Disruption and law enforcement

In 2022, the ACCC continued its work with other government agencies, law enforcement

(in Australia and overseas) to share intelligence, disrupt scams and raise awareness in

the community.

Scamwatch provided more than 116 disseminations of scam reports and intelligence on

high risk or current scam trends to law enforcement, government, and key private partners.

This intelligence assisted state and federal police to investigate and, in some instances,

prosecute scammers.

Scamwatch continued to share scam reports with the private sector. Reports where consent was

provided were shared with the nancial sector through the AFCX, Meta (Facebook), and Gumtree.

Each week Scamwatch also sent lists of alleged scammer phone numbers to the

telecommunications sector to inform their call and SMS blocking activities. Hundreds of millions

of calls and SMS were blocked by telecommunications providers in 2022.

3 Includes micro (0–4 staff) and small (5–19 staff).

8

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

The ACCC and ASIC engaged in trial of a third party

4

cybercrime disruption service in July 2022.

The ACCC referred 1,757 web addresses which were analysed over the 21 days of the trial.

During this time, 381 were found to be malicious and were removed preventing further harm to

the community.

As a result of collaborative work by banks; law enforcement and regulators, banks were able to

distribute frozen scam account funds. The remediation enabled some of the over 15,000 victims

of the Hope Business scam to receive a portion of their nancial losses.

Section 5 includes examples of law enforcement activity to combat scams.

Scamwatch met regularly with representatives across the nance sector through a range of

forums. These forums are important for information sharing and for exploring initiatives to

prevent scams and often involved law enforcement and other government agencies.

Education and awareness

Scams Awareness Week 2022 took place from 7–11 November. With the support of over

350 partner organisations, the campaign encouraged people to learn ways to identify scams and

take the time to check whether an offer or contact is genuine before acting.

Campaign resources included videos, posters, social media, and web content that supported a

consistent message across all participating organisations. Over 8 days, the Scams Awareness

Week campaign had a potential audience reach of 82 million with 2,586 mentions in print, online,

TV and radio.

By the end of 2022, Scamwatch had 148,421 subscribers to its email alert service and published

13 media releases warning the public about scams.

The Scamwatch website had over 6.36 million page views in 2022, and the ACCC’s Little

Black Book of Scams was viewed 49,247 times and downloaded 28,508 times. We distributed

110,990 hard copies.

In 2022 the Scamwatch Twitter account (@Scamwatch_gov_au) posted 217 tweets and by the

end of 2022 had over 37,000 followers.

In July 2022, the ACCC released its 2021 Targeting Scams Report which was viewed 9,371 times

and downloaded 4,939 times. The report provides meaningful information to support law

enforcement, government, and community organisations to prioritise investigative, disruption and

education activities.

The ACCC’s Indigenous outreach team raised awareness about scams during visits to the

following communities: Belyuen; Nauiyu; Broome region; Knuckey Lagoon; Bagot; Jabiru and

Gunbalanya visits; Daly River; and the Mile community.

Scamwatch staff presented at many forums in 2022 and conducted education activities

and outreach.

Policy, regulation and advocacy

In October 2022, the government announced seed funding for the ACCC to scope and plan a new

National Anti-Scam Centre. Many organisations have contributed to workshops and meetings to

inform the planning of the new Centre.

4 Netcraft provide global cybercrime disruption services including taking down fraudulent or malicious websites. Netcraft

do not exercise any regulatory powers for takedown, they issues requests to webhosts to investigate alleged fraudulent

websites in relying on the terms and conditions of service.

9

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

On 11 November 2022, the ACCC released the fth interim report for the Digital Platforms

Services inquiry. The ACCC has recommended a range of new measures to address harms from

digital platforms to Australian consumers, small business and competition.

– The ACCC recommended targeted measures to protect consumer and business users of

digital platforms against scams, harmful apps and fake reviews and

– Minimum standards for digital platform dispute resolution processes and the ability for users

to escalate complaints to an independent ombuds.

In July 2022, the ACMA registered new rules to require telcos to identify, trace and block SMS

scams. Under the rules, telcos must also publish information to assist their customers to

proactively manage and report SMS scams, share information about scam messages with other

telcos and report identied scams to authorities.

In September and October, the ACCC participated in taskforces to protect consumers from

the consequences of the Optus and Medibank cyber-attacks. These attacks exposed the

personal information and identity credentials of millions of Australians. The ACCC produced

information to assist the public to avoid the scams that followed the events and contributed to the

development of a scheme to provide access to information that could help prevent the misuse of

the information.

– The government implemented data sharing arrangements pursuant to the

Telecommunications Regulations 2021 to enable Optus to share data with nancial services

entities who agreed to certain conditions outlined by the ACCC.

The consequences of the cyber-attack included risk of identity misuse. The data breaches

highlighted the signicance of the earlier work by the ACCC, Department of Home Affairs and

other organisations to improve the document verication service (DVS) and ability for people

to obtain new credentials if they were at risk of misuse by providing unique identiers on driver

licences. As a result of card numbers being provided on licences and new elds becoming

compulsory in the DVS in early September 2022, better protections were in place to protect

consumers from identity misuse.

10

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

2. Combined data – the

bigger picture

To better understand the impact of scam activity in Australia, the ACCC obtained scam data from the

AFCX

5

, ReportCyber, the ATO, ASIC, the ACMA, Services Australia and IDCARE.

The AFCX covered 6 of the 12 nancial institutions covered in previous reports. It does not include

data from superannuation rms or cryptocurrency platforms.

Some outlier high loss or unveriable data has been removed for some organisations

Table 2.1: Combined losses and reports

Organisation Reports Losses

Scamwatch 239,237 $569.5m

ReportCyber 71,092 $1.1b

AFCX (6 nancial institutions) 144,000 $1.1b

ATO 15,773 $78,990

ASIC 1,846 $100.7m

ACMA 6,868 N/A

IDCARE 21,201 $258m

Services Australia 7,267 N/A

Total 507,284 $3.15 billion

The combined losses reported to Scamwatch and these other organisations in 2022 was just over

$3.1 billion across over 500,000 reports. This represents a 79% increase in losses compared

to 2021.

The highest losses were reported for investment scams with $1.5 billion. This was followed by

$229 million reported lost to remote access scams and $224 million to payment redirection

scams. A glossary at the end of this report explains scam categories and other terms.

Table 2.2: Combined losses by category

Scam type Scamwatch ReportCyber AFCX ASIC IDCARE TOTAL

Investment $377.2m $474m $427m $94.1m $184.1m $1.5b

Remote access $21.7m $17.3m $165m $25m $229.2m

Payment redirection $24.8m $147m $53m $224.9m

Romance $40.5m $88.6m $64m $17m $210.2m

Phishing $24.6m $133m $157.6m

Other $80.5m $382.6m $265m $6.6m $32.4m $784m

5 The AFCX includes data for National Australia Bank (NAB), Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ), Commonweath

Bank of Australia (CBA), Westpac, Bendigo Bank, and Macquarie Bank. Information about the AFCX is available here: https://

www.afcx.com.au/

11

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

3. Scamwatch trends in 2022

3.1 Australiansreportedsignificantlossesto

investmentscams

Combined losses to investment scams in 2022 were over $1.5 billion. Scamwatch received over

9,360 reports with reported losses increasing 112.9% to over $377 million.

Investment scams made up more than 66% of all nancial losses reported to Scamwatch compared

to 55% in 2021.

People who had contact with the investment scammer by phone reported the highest losses ($141

million). There was a 32.4% increase in reports about investment scams on social media and a 43%

increase in reported losses ($80.2 million). The most common payment method was cryptocurrency

($137.6 million

6

) followed by bank transfer ($99 million).

According to Scamwatch data, the average investment scam victim is likely to be a man, aged

65 or over and living in NSW. He will meet the scammer on social media or respond to a scam

advertisement and will have contact by phone. He is likely to be in the scam for several months

and pay the scammer via cryptocurrency or bank transfer.

Trend 1 – Imposter bond scams

Imposter bond scams impersonate nancial service companies or banks offering low risk investment

products such as government bonds and xed term loans. These scams have become more

sophisticated and can result in people losing money even when they do their own research. The

scammers will demonstrate specialised nancial knowledge, provide convincing documents, fake

websites, and fake information on review platforms.

6 Adjusted to remove outliers.

12

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

u Case Study: $50,000 lost to imposter bond scam

After making an inquiry on a comparison website about Australian treasury bonds, Aleisha

received a phone call from a ‘Paul’ claiming to work for a well known nancial planning

rm. She conrmed that she was interested in purchasing a treasury bond and asked for a

product disclosure document.

Aleisha spoke with friends and did weeks of background reading on the rm. She did some

background checks on ASIC and other government websites. It all appeared legitimate.

Using the link Paul had sent her, she provided her identity documents and created an

account on the online investment platform. Aleisha wanted to check the BSB and Account

number so she visited the Big4 bank branch and they veried the account was registered

with them and was real.

Not long after Aleisha sent payment for her treasury bonds, she received an email saying

that the platform required maintenance. Within a fortnight Aleisha stopped receiving

communications related to her investment. Two weeks later they ceased to exist and she

saw a news article conrming it was a scam. Paul had scammed her and she had no way

of retrieving her $50,000.

Trend 2 – Initial public offering scams

An initial public offering (IPO) involves a company raising capital by offering shares to the public for

the rst time. Scammers have been impersonating Australian companies including banks to promote

offers that coincide with legitimate company listings such as Porsche, Stripe, and SpaceX. They do

not have any association with the companies.

Documentation provided by the scammers is very detailed and appears real.

u Case study: $26,000 lost to a Porsche IPO scam

Jing noticed an online advertisement for the Porsche IPO and registered his interest using

an online form.

A few days later Jing received a call from ‘Richard’. Richard said he was an advisor from

a well-known Australian investment advisory service. Richard sent Jing a link to his

company’s website and a copy of the Porsche IPO prospectus.

They spoke often and Richard sounded knowledgeable. Jing purchased shares using

the account details Richard provided and the money went to a Big4 bank account. He

received ocial looking documentation as evidence of the purchase and he decided to

make a second purchase. The second payment was to a different Big4 bank account and

this bank blocked the transfer. Jing was told it was a scam account. But he was unable to

recover the initial payment of $26,000.

13

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Trend 3 – Relationship & romance baiting scams

Many investment scams will arise when a new online friend or romantic connection suggests that

they can help the victim invest. They may build the relationship for a long period of time before talking

about their success with investing. Once trust is established, the scammer will coach the victim to

invest their money and assist them to set up an account on a cryptocurrency platform.

In 2022, many high loss investment scams occurred in the context of a long-term friendship or

relationship that commenced on social media or a dating application.

Trend 4 – Money recovery services & scams

Another emerging trend related to investment scams is the increase in money recovery services.

Some of these are follow up scams that target people who have already lost money to a scam.

Others are businesses that often charge large amounts of money on the basis that they will get

money back for victims with most scam victims unable to recover funds.

u Case Study: Elderly woman pressured to pay $70,000 to money recovery service

Matilda alleged that her elderly mother was experiencing standover tactics by a money

recovery service.

Her mum, Silvia, was a self-funded retiree who lost all her retirement money (over

$3 million) in an investment scam. She reported it but couldn’t nd anyone to help her. She

found a business online that said they could recover the money.

She had to agree to a contract and pay a retainer being 5% of the total lost. Silvia then

started selling her assets so she could pay the retainer, but she could only pay $70,000.

The recovery service said she had to pay $80,000 before they would start investigating.

They threatened Silvia with legal action and she became scared they would take

her house.

Silvia asked Matilda to take out a loan against some land that she had so she could pay

the full $80,000. At this stage Matilda intervened and reported the money recovery service.

3.2 Phishingwasthemostreportedscamand

causedsignificantlosses

The most common category of scam reported to Scamwatch in 2022 was phishing. There was a

4.6% increase in reports to Scamwatch with 74,573 phishing scam reports received. Financial losses

increased 469% from the $4.3 million reported in 2021 to $24.6 million in 2022.

Most phishing scams were sent as text messages (38,481 reports). Text based phishing scams

also had the highest reported losses of $8.8 million. Phone based phishing scam reports decreased

by 46% to 16,790 but there was an increase in reported losses to $8.5 million. Email phishing scam

reports also increased 50.8% in 2022.

The payment method for the majority of phishing scam losses was bank transfer with $20.1 million

reported lost.

14

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

According to Scamwatch data, the average phishing scam victim is likely to be a woman, aged

65 or over and living in NSW. She will receive a text message that impersonates her bank, her

child or a road toll company. The message will contain a link that may be malicious or deceives

her to provide personal information or will ask for a direct transfer of money. She will lose

money by bank transfer.

Trend 5 – Highly sophisticated impersonation scams

Most phishing scams impersonate known and trusted brands or government organisations. The

purpose of the scam is to trick the recipient into providing personal information such as banking

details or driver licence, or to transfer money.

Phishing scams have increased in quality and sophistication in recent years. They will be carefully

constructed to mirror the usual communications of the brand they are impersonating and make it

dicult for regular customers of that brand to identify as a scam.

Scamwatch received 14,603 reports about bank impersonations with more than $20 million reported

lost. More than 90 of these reporters individually lost between $40,000 and $800,000. These scams

impersonate well known bank brands and will often pretend to be from the cyber security or fraud

area of the bank. They are convincing when they also use a spoofed phone number of the real

organisation or use the alpha tag (SMS sender ID) of the bank. The message will appear in the same

chain as legitimate messages making it almost impossible for people to detect.

Scammers also regularly impersonated common brands such as Amazon, Gumtree, eBay, Australia

Post or PayPal to scare victims into believing there has been an ‘account hack’.

u Case Study: Bank impersonation scam – over $300,000 lost

Niamh received a text message from a scammer which used the NAB SMS Sender Id

and appeared in her regular NAB messages. It said she had pre-approval for a $6,000

loan – this alarmed her as she had not applied for a loan. She called the number in the

message believing she was speaking with NAB but it was a scammer, and questioned

whether the message was a scam. Lena, a scammer, said it wasn’t a scam and that her

account was compromised. Lena said she would send a text to Niamh via NAB SMS

with a reference number to prove it was NAB. Niamh received the message and was

more convinced that she was talking to her bank. Lena told her that a person was logged

into Niamh’s banking and that she needed to move quickly to transfer money to secure

accounts. Niamh moved $300,000 from her account but became uneasy. The scammers

told her it was a scam and at the end laughed and said to Niamh ‘We are in Brisbane, come

nd me’. She terminated the call and contacted the real NAB fraud department.

15

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

u Case Study – Bank impersonation scam – over $30,000 lost

Mark received an SMS message from a scammer impersonating CBA that said an

irregular payment had been detected. A URL in the SMS had CBA in the address so he

thought it was genuine. He contacted the person who said he was from CBA Security. The

scammer said a payment had been made to JB HiFi for $70. Mark said he didn’t make it.

The scammer said someone was trying to take Mark’s money. He sent Mark a code which

he asked him to repeat several times to ensure reversal of the transactions. Mark noticed

the word ‘CRYPTO’ in the text and questioned whether this was genuine. The scammer

was able to convince Mark by referring to all the recent transactions on Mark’s account.

The scammer also told Mark to check the number he was calling from on the CBA website

and it matched. The scammer was using a spoofed number. But Mark ended the call. He

then discovered over $30,000 was taken from his account.

Impersonation scams have also started impersonating aspects of the PayID system. Scammers

will ask the victim to transfer money to a PayID phone number or email. Scammers will also send

fake text messages about payments made via PayID. For example, Your PayID Payment of $580 to

eBay has been paused subject to further checks. If you do not recognise this please contact us on XX

phone number.

u Case Study – Scammers impersonate bank and seek transfers to PayID

Arjun received a call from a scammer pretending to be Westpac and using the ocial

Westpac number. He was told his online account was compromised and that he needed

to transfer funds to a safe account. He was told to transfer the money to 2 PayID accounts

that used mobile numbers as the PayID. He believed it was real because of the real

Westpac phone number used by the scammer. He transferred almost $60,000.

u Case Study – Convincing bank scam leads to $10,000 loss

A scammer pretending to be ANZ called Sarah and said her account was compromised

by someone in Queensland. She was told to open a new account. The scammer had a

lot of her personal information including the rst 6 digits of her debit card and the type

of account. Sarah was wary about scams but the scammer sent 2 text message each

headed ANZ and appearing in the same chain as her real ANZ message. She also thought

it was real because the scammer had set up an account in her name to transfer her funds

to. She realised it was a scam after transferring $10,000 to the new account.

16

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Trend 6 – ‘Hi mum’ – scams impersonating family members

The emergence of the ‘Hi Mum’ scam in January was a new scam trend in 2022. It escalated in the

middle of 2022, defrauding many vulnerable Australians in a short period.

Scamwatch received 10,160 reports about the ‘Hi Mum’ scam in 2022 with a total of $7.3 million in

losses. The average loss was $5,742.

The scam involves a text message starting with the words, “Hi Mum” from a scammer claiming to

be the victim’s son or daughter. The messages refer to a lost phone or a new phone number and will

quickly ask for money for an urgent purpose. In some instances, victims were also asked to provide

photos of credit cards and identity documents.

While men were also recipients of ‘Hi Dad’ variations to the scam, 73% of victims reported to

Scamwatch were women. Over 90% of losses were reported by people aged 55 and over.

u Case study: Mum transfers $8,000 to scammer impersonating her son

Karlene received a text from someone she thought was her son, saying he had changed

his mobile provider and had a temporary new number. After several casual messages with

Karlene he asked for assistance to pay an After-pay invoice due that day.

The message stated that he couldn’t access his accounts because his new phone number

wasn’t linked yet. Karlene was provided enough information in the messages to make her

believe she was messaging her son.

Karlene made a payment of $4,000 via bank transfer, which her ‘son’ assured her he would

pay back the next day. They then asked for another payment of almost $4,000 which

Karlene transferred,

“It was when he asked me to make a 3rd transfer that I twigged that something was wrong.

I asked him to send me his date of birth and then the person said no and argued with me for

a while.”

With her suspicions realised, Karlene called her bank immediately to report the scam and

disputed the transactions.

Trend 7 – Unpaid road toll impersonation scam

Unpaid road toll scams use phishing techniques to impersonate road toll companies. They send

messages or emails claiming victims did not pay a road toll and include a hyperlink to pay the toll.

If victims provide their credit card details via the phishing sites, scammers will make unauthorized

transactions with their details.

In total, Scamwatch received 14,585 of these reports in 2022 with reported losses of $664,093.

The losses are mostly reported in states which have toll roads, NSW (33.41%), VIC (27.86%), and

QLD (21.06%).

17

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Figure 3.1:

u Case Study: $16,000 lost in LINKT scam

Daniel received a text from LINKT about an unpaid toll trip with the message “Please pay in

full to avoid late fees” which included a link. Daniel’s actual LINKT account was overdrawn

so he believed that the message was real and proceeded to click the link and enter his

credit card details. The next day he noticed 16 transactions of $1000 charged to his credit

card.

3.3 Youngpeoplelosingmoneyto

employmentscams

Trend 8 – Employment scams

Financial loss to job and employment scams increased by 259.4% to $9.6 million in 2022. Reports

decreased by 2% to 3,383. The average loss was $14,963 and the median loss was $3,150.

Most nancial losses were experienced by people who were contacted on social media ($3.2 million)

or via mobile applications like WhatsApp ($3.2 million). Most payments were made via cryptocurrency

($4.8 million) followed by bank transfer ($3.4 million).

The most nancially damaging employment scams occurred via social media, where victims were

told they could earn several hundred dollars for little effort while working from home.

Typically, these scams claim to be associated with legitimate companies, offering ‘task’ based

work requiring highly repetitive yet simple data entry or validation via an app or website, the need to

top up accounts via online trading platforms, and requests for more money to allow withdrawal of

large sums.

According to Scamwatch data, the average job scam victim is likely to be a young man or

woman, aged between 25 and 34 years old and living in NSW or Victoria. They may come

from a culturally and linguistically diverse community. They will usually receive a WhatsApp

message or meet the scammer on social media or a job platform. They will be encouraged to

communicate via WhatsApp. They are likely to be in the scam for a long period of time and pay

the scammer via cryptocurrency.

18

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

u Case study: Job scam costs victim $65,000

With the cost of living increasing, Lucinda needed a second job. She was excited when

she received a WhatsApp message offering her a job with a great hourly rate where she

could work from home rating hotels online. She could work in her own time and would

receive one-on-one online training before starting the job.

She was told that as the popularity of the hotel rises, so too would her earnings. After

receiving her intensive training and completing her required quota of ratings, she

could see her potential earnings increase. The Hotel booking service platform required

her to inject cryptocurrency to complete the ratings but she received that back plus

a commission.

When it was time for her to withdraw the almost $65,000 in her crypto wallet however, she

received a letter stating that she would have to pay an additional 35% of the withdrawal

amount as a fee to release the funds.

“I was so stressed out that I told my family, and they rushed me to go to report it to

the police.”

Under the advice of her family, she has since ceased all contact with the group.

3.4 OlderAustralianslosingmoneytoremote

accessscams

Trend 9 – Remote access scams

Remote access scams continue to be a signicant problem in Australia. Combined reported losses

about remote access scams were $229 million in 2022.

Scamwatch received 11,792 reports about remote access scams (a decrease of 24.9%) with reported

losses increasing 32.6% to $21.7 million in 2022. The average loss was $17,328 and the median loss

was $5,000.

Almost all remote access scams commence with a phone call and most losses occur via bank

transfer ($15.5 million). People aged 65 and over reported losing the most money to these scams

with $9.2 million reported lost.

According to Scamwatch data, the average remote access scam victim is likely to be a woman

aged 65 or over, living in NSW. She will usually receive a phone call while at home and be

scared or tricked into providing remote access to her device or computer. The contact may

come after her legitimate enquiries with her ISP about problems with her NBN connection.

She may not be immediately aware that the scammer has accessed her bank accounts to do a

transfer.

19

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

u Case study: remote access scam loss of over $30,000

Laura, 78 got a phone call from a ‘Paul’ asking if she had purchased anything from eBay.

She said she had never used eBay. Paul said hackers were using people’s accounts and

making purchases. Paul said eBay security was setting up a sting and they wanted her

help. Laura was aware of scams and was sceptical. Paul assured her it was real and said

they were working with the Australian Cyber Security Centre.

Paul asked her to download an app to track her computer to catch the hackers, which she

did. Over a couple of months Paul made her move her money from her bank account into

other accounts, some that used her name. She was told it was top secret and she couldn’t

tell the bank staff as they believed someone in the bank was involved. Eventually the bank

threatened Laura that if she didn’t tell them what was going on they would tell the police.

By this time all of her money was gone.

3.5 ReportstoScamwatchdecrease16.5%

Trend 10 – Reasons for decrease in reports in 2022

Reports to Scamwatch decreased by 16.5% in 2022, from the 286,622 received in 2021 to

239,237 in 2022. One of the biggest contributors to the decrease in reports was the reduction in

phone scam reports. In 2022 phone scam reports decreased 55.9% from 144,603 received in 2021 to

63,821 in 2022. This coincided with the implementation of the Reducing Scam Calls and SMS Code

which requires telecommunications providers to monitor and block scam calls. It also reected the

work undertaken by law enforcement and regulators here and internationally to stop the Flubot phone

scams which had led to signicant increases in phone scam reports in 2021.

Phone was the only contact method that decreased in 2022, all other contact methods increased

in reports.

The scam categories that had the most signicant decrease in reports were ‘Threats to life, arrest

or other’ which decreased 90.6% from 32,426 reports in 2021 to 3,036 in 2022 and ‘Ransomware &

malware’ which decreased 32.2% from 3,623 in 2021 to 2,457 in 2022.

There may also be some apathy in reporting due to the often-daily contact that Australians receive

from scammers, particularly via text message. Decreases in reporting may suggest that it is more

normal for Australians to receive contact from scammers, and they may be less likely to report them

if they have not fallen victim to a scam. Scamwatch continues to encourage people to report scams

that they see or receive as it helps organisations raise awareness so that people do not fall victim

to them.

20

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

4. The people reporting scams

4.1 Thedemographics

People who report to Scamwatch differ in gender, age, location and ethnicity

7

. Some people report on

behalf of a relative and some report on behalf of a business or community organisation. Scamwatch

collects demographic data to help it and other agencies understand who is most impacted by

scams and provide warnings and information to people in an effective way. This section of the report

explores who reported and lost money (and often personal information) to scams in 2022.

Not everybody who reports a scam provides their age, gender, location or ethnicity, but those that do,

provide us with valuable insight into how scams impact different demographics.

Gender

In 2022, men reported losing more money than women. Men reported losses of $273 million and

women reported losses of $231.5 million. However, women made slightly more reports than men.

Table 4.1: Gender and scam reports and losses

Gender No. of reports Reports with loss Losses

Men 112,975 13,399 $273m

Women 120,418 15,330 $231.5m

Non-specied 5,844 260 $64.9m

Both men and women lost more money to investment scams than any other type of scam. While

men lost more money to investment scams women lost more money than men in all other top

loss categories.

Table 4.2: Top loss scams by gender

Gender Men Women

Investment scams $190.9m $123.6m

Romance scams $13.5m $27m

Phishing $11.3m $13.1m

False billing $10.8m $13.7m

Remote access $8.9m $12.7m

7 Scamwatch does not collect data about specic ethnicity. Reports can identify in the report form as a person who speaks a

language other than English.

21

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Age

In 2022, people aged 65 and over made the most reports to Scamwatch (49,163) and reported the

highest losses of $120.7 million. Losses reported by women increased 76.5% in 2022. Similar to 2021,

losses in 2022 generally increased with age with the exception of higher reported losses for people

aged 35–44.

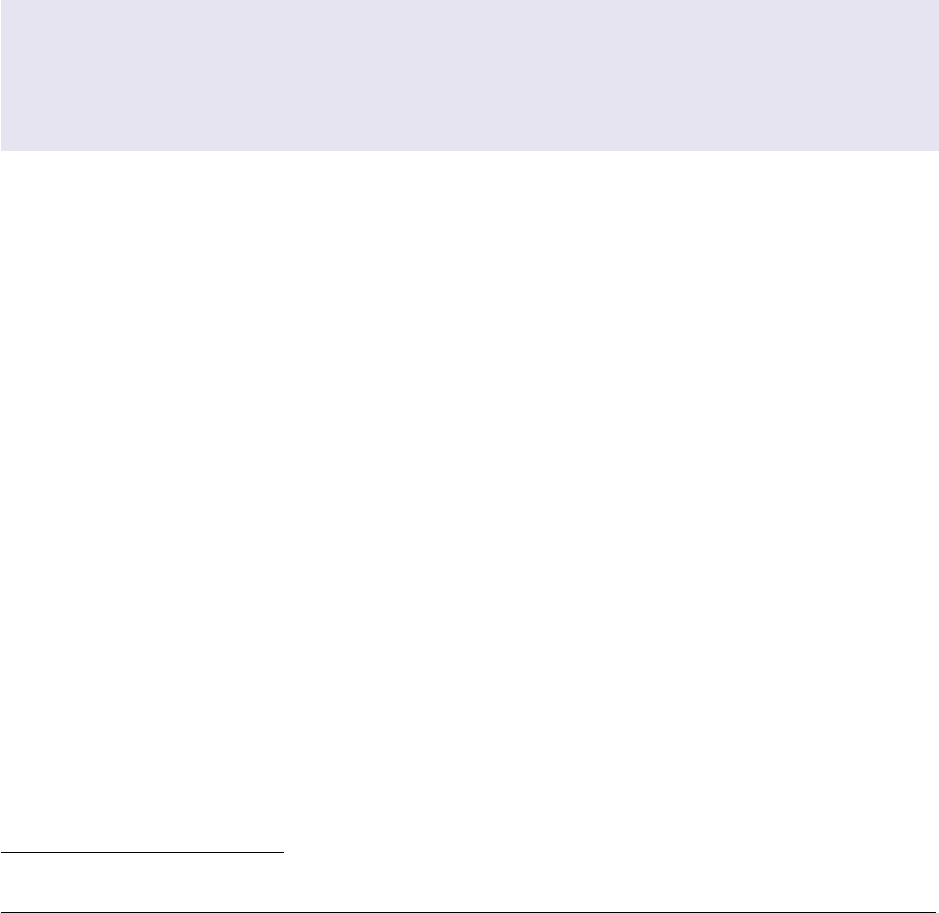

Figure 4.1: Age Group

0 k

10 k

20 k

30 k

40 k

50 k

60 k

70 k

$0 m

$20 m

$40 m

$60 m

$80 m

$100 m

$120 m

$140 m

< 18 18–24 25–34 35–44 45–54 55–64 65 and Over N/A

2021 Losses 2022 Losses 2021 Reports 2022 Reports

Table 4.3: Number of Scamwatch reports and losses by age group – 2022

Age 2022 Reports 2022 Losses 2021 reports 2021 losses

>18 1,550 $361,976 1,984 $366,592

18–24 10,508 $16m 14,834 $12.7m

25–34 27, 281 $5 7.5 m 39,954 $40.3m

35–44 32,735 $91.2m 43,527 $ 47.8 m

45–54 36,639 $88.3m 38,893 $57.6m

55–64 32,367 $99.5m 37,64 4 $58.9m

65 and over 49,163 $120.7m 46,286 $81.9m

N/A 52,994 $95.6m 63,500 $23.8m

22

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

4.2 ScamsaectingIndigenousAustralians

Scamwatch invites reporters to indicate whether they are Indigenous

8

when they complete a

webform. This information helps Scamwatch to identify the types of scams that may be impacting

Indigenous Australians and target our warnings to the relevant communities.

Financial losses reported by Indigenous Australians increased 5.3% to $5.1 million but reports

decreased 21.6% to 3,889. The average loss reported was $8,123 and the median loss was

$754 which represents up from the $650 reported in 2021.

The highest losses reported by Indigenous reporters were Investment scams ($2.5m), Dating &

romance scams ($764,000) and Jobs & employment scams ($278,000). Indigenous Australians

reported higher median losses ($1,075) to classied scams when compared with all reporters

($900 for all reporters).

Table 4.4: Top 5 scams with highest losses for Indigenous Australians

Scam type Losses % from 2021 Median loss

Investment $2.5m 63.1% $4,000

Romance $764,883 47.6% $2,100

Jobs & employment $278,14 4 108.3% $2,400

Identity theft $228,927 239.3% $1,500

Classied scams $227,686 15.4% $1,075

u Case study: Indigenous Australian loses over $30,000 to investment scam

Adam met Cindy on Tinder. Cindy mentioned her brother had helped her set up a protable

investment portfolio. She said her brother could help Adam make money too. He was

connected by a colleague of Cindy’s brother, Matt, who helped Adam set up accounts with

cryptocurrency exchanges.

Adam spoke with Matt daily, making trades, transferring more cryptocurrency, selling

different types of cryptocurrencies, and monitoring his prots.

After a month, the prots turned to large losses and Adam couldn’t get in contact with

Matt or Cindy. They had both blocked him on social media. Adam also couldn’t access his

account on the platform and the cryptocurrency exchange.

“I came across information about this happening to others and now I am reporting it. I can

show bank details from my transactions and have access to Binance who have told me they

can’t do anything but just to report it.”

8 Scamwatch reports may include reporters who identify as Indigenous in other countries.

23

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

4.3 Scamsaectingculturallyandlinguistically

diversecommunities

People reporting to Scamwatch can identify as a person from a ‘non-English speaking background’

when lodging an online report. This is used as a proxy by Scamwatch to report on scams that impact

culturally and linguistically diverse communities (CALD communities). Scamwatch does not collect

data on the specic languages spoken or cultural backgrounds of reporters from a non-English

speaking background.

In 2022, people from CALD communities made up almost 5% of reports and almost 10% of reported

losses. They collectively made 11,418 reports (decrease of 18.8%) with $56.6 million in reported

losses (increase of 36.1%). The median loss for CALD consumers was $1,435 (up from the $1,200 in

2021) and the average loss was $24,330.

The highest losses for CALD communities were reported by people aged 45–54 and 35–44. Women

from CALD communities reported higher losses than men.

Compared to non-CALD reporters, CALD communities were more likely to experience scam losses

on social media with $17.5 million reported lost. The second highest contact method was phone call

with $11.1 million reported lost.

Table 4.5: Top 5 scams with highest losses for CALD communities

Scam type Losses % change from 2021 Median loss

Investment $29.7m 45.2% $13,000

Romance $6.6m -6.6% $4,800

Threats to life, arrest or other $6m 49.9% $34,166

Identity theft $2.9m -19.3% $1,252

Pyramid schemes $2.4m 386.1% $14,331

People from CALD communities were over-represented in the losses for some scam types,

accounting for:

7.8% of reports but 43.7% of losses to scams involving threats to life arrest or other

15.9% of reports but 32.7% of losses for pyramid scheme scams

6.0% of reports but 27.9% of losses for identity theft

4.4% of reports but 23% of losses for inheritance scams

8.4% of reports but 21.4% of losses for jobs & employment scams

24

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

u Case study – Student loses all his money to threat based scam

“I told them I am a student, and I don’t have any other money.”

Yusuf received a call from a person stating they were from the ATO. The scammer said

there was money laundering using his tax le number and threatened him with arrest.

They offered to help Yusuf with this situation, but he would have to move all his money

from his existing accounts into holding accounts to allow the investigation to continue and

to protect his money.

When he disagreed, the caller said his accounts would be frozen and he would be arrested

and deported. They demanded Yusuf provide a picture with his passport near his face, and

a picture of it on a at surface, which he provided.

Yusuf moved his money into the account they provided. The caller then directed him to

pay more money for the cost of the ‘federal procedure’, but Yusuf had no money left. He

contacted the ATO soon after and was advised it was a scam.

4.4 Scamsaectingpeoplewithdisability

When people report to Scamwatch, they can indicate if they identify as a person with disability on the

report form. This helps Scamwatch identify scams that may be targeting or impacting people with

disability so that we can ensure our warnings are relevant and effective.

Scamwatch received 16,473 reports (6.8% of total reports) from people with disability, with nancial

losses of $33.7 million (5.9% of total losses) reported. Reports increased 7.1% and losses increased

71.2%. The median loss for people with disability was $900 and the average loss was $18,024. More

people with disability reported losing money in 2022 than in 2021.

People with disability who lost money to scams were more likely to be in Victoria, or Queensland.

The most common contact methods where people with disability lost money were phone ($8m) and

internet ($7.8m). People aged 45–54 lost the most with $11.8 million reported lost.

Unlike most other reporters, people with disability were more likely to specify ‘other payment’ as the

method of payment. $13.4 million was reported lost to other payment methods in 2022. Some people

with disability specied payment by taking actions such as transferring house ownership, or multiple

bank and cryptocurrency transfers, debt owing, superannuation fund, or paid by cheque.

Table 4.6: Top 5 scams with highest losses for reporters with disability

Scam type Losses % change from 2021 Median loss

Investment $18.7m 135.6% $10,000

Romance $4.6m 8% $2,000

Threats to life, arrest or other $4.2m 296.5% $1,912

Phishing $899,724 6 87.7% $3,100

Remote access scams $897,898 -22.8% $2,890

25

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

The susceptibility to loss from ‘threats to life, arrest or other’ scams is common to both CALD

communities and people with disability, and a difference from the overall population’s losses to this

category for which it ranks sixth. These scams rely on a fear of authority or lack of familiarity with the

scam or with the processes of businesses or government. More research is required to understand

the vulnerability to these scams and how it could be addressed.

People with disability were over-represented in the losses for some scam types, making up:

11.2% of reports but 30.5% of losses for scams involving threats to life, arrest or other

7.2% of reports but 23.1% of losses for ransomware and malware

5.7% of reports but 14% of losses for mobile premium services scams.

u Case study – Young man loses all his money to sextortion scam

Ryan, 18 came across a woman who was posting her Snapchats publicly on Reddit. He

added her Snapchat account and the woman added him back. She asked Ryan to share a

video of himself “for fun” which Ryan did assuming it was harmless and just between the

2 of them.

The woman sent Ryan a Facebook friend request which he accepted. What Ryan didn’t

know was that the woman had captured the ‘compromising’ Snapchat video of him, and

she now had access to his friends and family on Facebook. The woman threatened Ryan

that if he didn’t send her money, she would share the video with all his Facebook contacts.

Ryan sent $1,000, over multiple payments until he had no more money to send.

The businesses losing money to scams

Scamwatch receives reports about scams from businesses and they are invited to indicate whether

they are large (over 200 staff); medium (20–199); small (5–19) of micro (0–4) or not to provide

the size.

The scam that impacts business the most is payment redirection, also known as business email

compromise. Combined losses to these scams from Scamwatch, ReportCyber and the AFCX were

$224 million.

Overall, Scamwatch received 3,857 reports from business with $23.2 million reported lost. This

represents a 73% increase on the $13.4 million reported last year. The most common contact method

was email (49.9%) resulting in 2,183 reports with $8.5 million reported lost.

Table 4.6: Losses and reports by business size

Business size by staff Reports Losses Losses % change from 2021 Median loss

Micro (0–4) 1,176 $8m 128.6% $3,350

Small (5–19) 843 $5.6m 60.9% $4,559

Medium (20–199) 634 $3.6m -13.5% $4,100

Large (over 200) 570 $980,000 132.8% $9,330

Size not provided 634 $4.8m 176% $2,767

26

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Among common business-related scams were payment redirection (business email compromise),

where scammers compromise the business email, either through hacking or by impersonating the

businesses email (by changing one letter in the email address). They alter invoices or requests for

payment by changing the bank account details. Many of these are reported to Scamwatch as false

billing scams.

While all business sectors are affected by these scams, historically the typical targets are high

transaction industries such as real estate conveyancing rms or the construction industry. In 2022,

however as international travel reopened post-COVID19 border closures the luxury travel industry was

also targeted.

Table 4.7: Top 5 scams by loss – business

Scam type Losses % change from 2021 Median loss

Investment $9.8m 94% 50,000

False billing $8.6m 1174% 6,000

Identity theft $1.2m 598% 2,922

Phishing $1.2m 627% 8,000

Remote access 854,000 843% 25,000

The highest number of reports were received from New South Wales businesses (34.5%) followed by

Queensland (19.3%) and Victoria (18.5%).

Queensland businesses reported the highest average loss ($54,636) followed by South Australia

($35,353) and New South Wales ($32,929). In terms of small businesses, those based in WA reported

losing the most money ($1.7m). For micro businesses those based in Queensland reported losing the

most ($2.2m)

u Case study – West Australian farmers lose $1 million

Farmers from Western Australia lost $1 million to scammers after their email account

was compromised.

Two emails containing invoices for payments, one for the sale of grain and the other for

agricultural machinery were fraudulently updated with bank account details that did not

belong to the farmers.

The email compromise was only identied after the farmers contacted the businesses to

follow up the missing payments.

27

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

5. Law enforcement activity to

combat scams

Most scams are crimes of deception. State and federal police in Australia and overseas investigate

some scams and prosecute scammers in relevant jurisdictions.

Examples of actions from law enforcement in Australia include:

Commonwealth public ocials’ impersonation arrests

9

In April 2022, 2 Sydney men faced court after an Australian Federal Police led Taskforce

Vanguard investigated a fraud syndicate allegedly impersonating public ocials.

It was discovered that members of a fraud syndicate allegedly contacted the victim, claimed to be

Commonwealth public ocials and deceived the victim into providing personal information and

transferring funds from their bank account.

SMS spoong scam arrests

10

In August 2022, the AFP arrested a man, for his alleged role in a Sydney-based criminal syndicate

accused of stealing banking and identication details from thousands of Australians in a bid to

access their accounts.

Operation Lasion began in September 2021 to identify the criminals responsible for sending

hundreds of thousands of automated text messages that contained links to replica Australian

banking and telecommunication websites.

The SMS phishing scam is alleged to have started in 2018 to target customers of the

Commonwealth Bank of Australia, National Australia Bank and Telstra, among others.

Fraud enabling technology arrests

11

In November 2022, 2 Victorians were charged following an international investigation into a

website selling fraud enabling technology responsible for more than $1,000,000 stolen from

Australian victims.

Operation Stonesh was launched in August 2022 after authorities in the United Kingdom began

an investigation into a website that offered a multitude of spoong services, for as little as

£20 British Pounds.

Once subscribed the site enabled users to make fraudulent robo-calls including sending

One-Time-Pins and other services designed to make the call seem legitimate to the victims.

9 https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/two-arrested-following-investigation-scammers-impersonating-afp-

ocers.

10 https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/second-man-charged-over-sms-phishing-scam.

11 https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/second-man-charged-over-sms-phishing-scam.

28

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

International investment scam syndicate arrests

12

In December 2022, 4 Chinese nationals living in Sydney were charged as part of an investigation

into an organised criminal syndicate involved in a cyber-enabled investment scam that resulted in

more than US$100 million in losses world-wide.

The highly sophisticated scam involved the unlawful manipulation of legitimate electronic trading

platforms, normally licensed to foreign exchange brokers who then provide the software to

their clients.

The organised crime syndicate used a sophisticated mix of social engineering techniques,

including the use of dating sites, employment sites and messaging platforms to gain the victim’s

trust before mentioning investment opportunities.

Actions from international law enforcement include:

Business Email Compromise scam arrests

13

In January 2022, INTERPOL reported the arrest of 11 alleged members of a prolic cybercrime

network. Operation ‘Falcon II’ identied that the suspects were members of a network known for

Business Email Compromise scams which harmed thousands of companies globally.

Scam call centre arrests

14

A two-month worldwide crackdown (8 March – 8 May 2022) codenamed ‘First Light 2022’ on

social engineering fraud resulted in scammers identied globally, substantial criminal assets

seized, and new investigative leads triggered in every continent.

The operations saw 76 countries take part in an international clampdown raiding national call

centres suspected of telecommunications or scamming fraud, particularly telephone deception,

romance scams, e-mail deception, and connected nancial crime.

Transnational cybercrime arrests

15

In May 2022, the cybercrime unit of the Nigeria Police Force arrested a 37-year-old Nigerian man

in an international operation spanning 4 continents (Africa, Australia, Canada, and the United

States).The suspect is alleged to have run a transnational cybercrime syndicate that launched

mass phishing campaigns and business email compromise schemes targeting companies and

individual victims.

12 https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/four-men-charged-sydney-sophisticated-cyber-scam-world-wide-

losses.

13 https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2022/Nigerian-cybercrime-fraud-11-suspects-arrested-syndicate-

busted.

14 https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2022/Hundreds-arrested-and-millions-seized-in-global-INTERPOL-

operation-against-social-engineering-scams.

15 https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2022/Suspected-head-of-cybercrime-gang-arrested-in-Nigeria.

29

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

6. Glossary links

6.1 Scamtermsandcategories

Business email compromise scams

Please refer to payment redirection scams below.

Classied scams

Scammers use online and paper based classieds and auction sites to advertise popular products

(even puppies) for sale at cheap prices. They will ask for payment up-front and often claim to

be overseas.

The scammer may try to gain victims’ trust with false but convincing documents and

elaborate stories.

Dating and romance scams

Scammers take advantage of people looking for love by pretending to be prospective partners, often

via dating websites, apps or social media. They play on emotional triggers to get victims to provide

money, gifts or personal details. Dating and romance scams can continue for years and they are

increasingly introducing investment scams. They cause devastating emotional and nancial damage.

Fake charity scams

Scammers impersonate genuine charities and ask for donations. These scams are particularly

prolic after public tragedies such as natural disasters and other events such as, for example, the

2020 bushres and the COVID-19 pandemic.

False billing scams

False billing scammers send invoices demanding payment for directory listings, advertising, domain

name renewals or oce supplies that were never ordered. They tend to target businesses over

individuals. These scams often take advantage of businesses’ limited resources and rely on them

paying the amount before realising the invoice is fake.

Hacking

Hacking occurs when a scammer uses technology to break into someone’s computer, mobile device

or network.

30

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Health and medical products

Health and medical product scams may sell victims healthcare products at low prices that they never

receive or make false promises about their products, such as medicines and treatments that will cure

you or have special healing properties.

Hope business/Wonderful world scams

In these scams, victims are encouraged to sign up for a ‘work from home’ job with the premise of

earning a signicant amount of money. The specics of the job vary but the scam always moves to

include the transfer of the victim’s own money to bank accounts specied by the scammers. The

scams often involve professional-seeming online support, live chats and social media discussion

forums with other people participating in the scheme. Many of the other users are in fact placed there

by the scammer.

In the Hope Business scam, victims thought they were purchasing items from online merchants

to increase their trac on online marketplaces but in fact were sending money directly to the

scammers’ bank accounts. Initially, victims would receive a full refund of the money they sent plus

a ‘commission’. Victims received referral bonuses for signing up friends and family members.

Scammers eventually stopped allowing participants to withdraw any funds and encouraged them to

send more money to allow funds withdrawal.

Identity theft

Identity theft is fraud that involves using someone else’s personal information to steal money or gain

other benets. Identity theft has become a signicant risk in most scams.

Inheritance and unexpected money scams

These scams offer victims the false promise of money via an inheritance or other unexpected

opportunity to claim a large sum of money in their name to trick them into parting with their money or

sharing their bank or credit card details.

Investment scams

Investment scammers offer a range of fake nancial opportunities and the promise of high returns

with low risk. These may include fake initial stock or coin offerings, brokerage services or an

investment in expensive software or online trading platforms. These scammers often use glossy

brochures and professional-looking websites to lure victims.

Jobs and employment scams

Jobs and employment scams trick victims into handing over money or personal information to

scammers while applying for a new job. Some iterations of this scam will offer a guarantee to make

fast money or a high-paying job for little effort.

Mobile premium services

Scammers will often create text message competitions to trick people into paying extremely high call

or text rates when replying to unsolicited text messages on mobiles.

31

ACCC | Targeting scams | Report of the ACCC on scams activity 2022

Online shopping scams

Online shopping scams involve scammers pretending to be legitimate online sellers, by using a fake

website or setting up a fake prole on a genuine website or social media platform.

Overpayment scams

Overpayment scams work by getting victims to refund a scammer who has sent them too much

money for an item they are selling, or an item they have purchased online and for which they have

purportedly been charged too much money. The victim later discovers the scammer never paid the

initial amount in the rst place.

Payment redirection scams

Note these scams are sometimes referred to as business email compromise scams.

These scams involve targeted phishing and hacking of a business. Scammers commonly send

emails to the business’ clients requesting payment to a fraudulent account, often by manipulating