© 2021 International Monetary Fund

IMF POLICY PAPER

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE

CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES: PRIORITIES,

MODES OF DELIVERY, AND BUDGET IMPLICATIONS

IMF staff regularly produces papers proposing new IMF policies, exploring options for

reform, or reviewing existing IMF policies and operations. The following documents have

been released and are included in this package:

• A Press Release summarizing the views of the Executive Board as expressed during its

July 16, 2021 consideration of the staff report.

• The Staff Report, prepared by IMF staff and completed on June 30, 2021 for the

Executive Board’s consideration on July 16, 2021.

The IMF’s transparency policy allows for the deletion of market-sensitive information and

premature disclosure of the authorities’ policy intentions in published staff reports and

other documents.

Electronic copies of IMF Policy Papers

are available to the public from

http://www.imf.org/external/pp/ppindex.aspx

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

July 2021

PR21/238

IMF Executive Board Discusses a Strategy to Help Members

Address Climate Change-Related Policy Challenges

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Washington, DC – July 30, 2021: On July 16, 2021, the Executive Board of the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) discussed a paper proposing a strategy to help members address

climate change-related policy challenges.

The paper highlights macro-critical climate-related policy challenges that will confront all IMF

members in the coming years and decades. For example, global warming is bound to

undermine productivity and growth, affecting fiscal positions and debt trajectories. It will also

impact asset valuations, with repercussions for financial stability. Further, climate change will

redistribute income across the globe, which will influence trade patterns and exchange rate

valuations. To live up to its mandate, the paper argues, the IMF needs to assist its members

with addressing these challenges. Moreover, as a multilateral institution, the IMF can play a

helpful role in facilitating policy coordination between countries to mitigate climate change.

The paper takes stock of climate-related activities in the IMF to date. It finds that the Fund has

stepped up engagement on climate significantly in recent years—reflecting in part demands by

the membership—with a focus on policy papers and flagship reports, accompanied by some

discussion of climate change-related policy challenges in bilateral country reports.

The paper argues that the time has come for a systematic and strategic integration of macro-

critical aspects of climate change into the IMF’s core activities. It proposes covering climate

change-related policy challenges comprehensively in Article IV consultations, aiming at

discussing such challenges with all members every 5-6 years, and more frequently with the

largest emitters of greenhouse gases and countries particularly vulnerable to climate change.

It also suggests expanding coverage of climate risk to all financial stability assessments

(FSAPs), and a substantial scaling up of climate-related capacity development (CD) activity in

line with member demand. In strengthening its engagement on climate, the IMF will continue

to cooperate and partner closely with other institutions to leverage complementarities and

provide the best service to its members. The paper also estimates the cost of implementing

the strategy.

Executive Board Assessment

1

Executive Directors welcomed the opportunity to discuss a strategy to help Fund members

address climate change related policy challenges. They concurred that climate change is a

global existential threat that poses critical macroeconomic and financial policy challenges for

the whole Fund membership in the coming years and decades. Against this backdrop,

Directors broadly agreed that the Fund has an important role to play, within its mandate, in

1

At the conclusion of the discussion, the Managing Director, as Chairman of the Board, summarizes the views of Executive Directors,

and this summary is transmitted to the country's authorities. An explanation of any qualifiers used in summings up can be found here:

http://www.IMF.org/external/np/sec/misc/qualifiers.htm.

supporting members’ efforts to address climate change related challenges through its

surveillance, when macro-critical, and through its capacity development (CD) activities.

Directors supported a more comprehensive coverage of climate change related policy

challenges in Article IV consultations, where macro-critical. In line with the conclusions from

the Comprehensive Surveillance Review, they generally agreed that coverage of climate

change mitigation in Article IV consultations would be strongly encouraged for the largest

emitters of greenhouse gases. Some Directors stressed that this means that coverage of

these policies would be voluntary. Directors supported the proposal to regularly cover

adaptation and resilience building policies for the most vulnerable countries to climate change,

including options to attract climate financing. In addition, they generally saw a need to cover

the management of transition risks, including for fossil fuel exporters, of adjusting to a low

carbon economy, while taking into consideration each country’s own circumstances.

Directors agreed that Financial Sector Assessment Programs should have a climate

component where climate change may pose financial stability risks. This would help assess

any potential pressure points for the financial system from physical climate shocks and from

the transition to a low-carbon economy. A few Directors emphasized that this climate

component should be aligned with the standards being developed by relevant international

standard-setting bodies to ensure a consistent policy advice.

Directors supported expanding climate-related CD efforts, given rising demand by the

membership. They also generally supported complementing Fund CD resources with donor

funded activities. A number of Directors also noted that the Fund could consider using

program conditionality to support borrowing countries to increase their resilience to climate

change shocks and ensure macroeconomic sustainability, provided the conditionality is in line

with the Fund’s lending mandate and policies. A few Directors cautioned, however, against

using climate-related conditionality.

Directors agreed that policy papers and multilateral surveillance reports should remain critical

outlets for disseminating the Fund’s analytical and policy work on climate change, especially

for topics with a multilateral component that require policy coordination, such as mitigation

policies or climate financing. Directors underscored that reliable climate data are a critical

foundation for macro-climate analysis and encouraged further work in this area. They

generally stressed the importance of developing models and standardized toolkits to support

the Fund’s work in both multilateral and bilateral surveillance, while being mindful of potential

limitations in models and toolkits, including due to specific country circumstances.

Directors stressed the importance of partnering with other institutions, including the World

Bank Group, on climate-related work. They called for a more systematic approach to

collaboration to leverage the expertise of other institutions, while minimizing overlap and

maximizing value for the membership.

Directors took note of the proposal for gradually adding 95 Full-Time Equivalents to

implementing the proposed climate strategy. They looked forward to assessing this, together

with other funding requests, during the discussion of the Fund’s overall budget.

Directors generally agreed that some internal re-organization that facilitates an efficient

delivery of the climate strategy would be needed, in particular by establishing climate hubs in

functional departments and reinforcing area departments as necessary. A few Directors

stressed that greening the Fund’s own operations and reducing its carbon footprint will be key

for the institution’s credibility.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE

CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES: PRIORITIES,

MODES OF DELIVERY, AND BUDGET IMPLICATIONS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Climate change has emerged as one the most critical macroeconomic and financial

policy challenges that the IMF’s membership will face in the coming years and decades.

By contributing to a higher frequency and intensity of natural disasters, climate change

is already imposing large economic and social cost on many economies. In the period

ahead, climate change is bound to affect macroeconomic and financial stability through

numerous other transmission mechanisms, including fiscal positions, asset prices, trade

flows, and real interest and exchange rates. While the mechanisms’ relative importance

will differ between individual countries, no country can expect to be spared entirely.

Many of the ensuing policy challenges fall firmly within the realm of the IMF’s expertise,

and for the Fund to live up to its mandate, it needs to assist its members in addressing

these challenges. Moreover, climate change mitigation is a global public good and

requires an unprecedented level of cross-country policy cooperation and coordination.

As a multilateral institution with global reach, the IMF can assist with coordinating the

macroeconomic and financial policy response.

Driven by demands of the membership, the IMF has stepped up its engagement on

climate-related issues in recent years, and it has started building up expertise. The

approach to date has placed heavy emphasis on flagship reports and policy papers,

accompanied by some discussion of climate change-related policy challenges in

bilateral country reports. The IMF has also experimented with new formats, such as the

Climate Change Policy Assessments conducted on a pilot basis with the World Bank.

The ad-hoc approach has reached its limits, however, and the time has come for a more

systematic and strategic integration of climate change into the IMF’s activities.

This paper proposes a comprehensive strategy for the IMF’s engagement on macro-

critical, climate-related policy issues. It starts from a stock-taking exercise that reviews

the Fund’s activities in this area thus far. The paper then presents a detailed concept of

adequate engagement to serve the needs of the membership, including the delivery of

specific outputs and collaboration with other institutions. The final section sketches

budgetary and human resource management implications.

June 30, 2021

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Approved By

Ceyla Pazarbasioglu

Prepared by the Strategy, Policy, and Review Department in close

collaboration with almost all departments, in particular the Fiscal

Affairs, Monetary and Capital Markets, and Research Departments as

well as the Office of Budget and Planning. The staff team consisted of

Saad Quayyum, Tito da Silva, Vimal Thakoor, and Irene Yackovlev, was

led by Johannes Wiegand, and worked under the general guidance of

Kristina Kostial (all SPR). Significant contributions were provided by

Valerie Guillamo, Fouad Manal, Emanuele Massetti, Ian Parry, James

Roaf (all FAD), Florence Jaumotte (RES), Prasad Ananthakrishnan, Ivo

Krznar, Dulani Seneviratne (all MCM), Liam O’Sullivan (SPR), Keith Clark

(CSF), and Iryna Ivaschenko (ORM). Comments are gratefully

acknowledged from departments and from Axel Schimmelpfennig

(OBP). Marisol Murillo and Elisavet Zachou (SPR) assisted with the

production of the paper.

CONTENTS

Abbreviations and Acronyms _____________________________________________________________________________ 4

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW _____________________________________________________________________ 6

CLIMATE CHANGE: A CRITICAL MACRO-ECONOMIC POLICY CHALLENGE _____________________ 7

A. Economic Impact _______________________________________________________________________________________ 8

B. Macroeconomic and Financial Policy Challenges ____________________________________________________ 9

IMF ENGAGEMENT ON CLIMATE CHANGE ISSUES TO DATE____________________________________ 10

A. Direct Country Engagement __________________________________________________________________________ 11

B. Multilateral Surveillance, Analytics, and Policy ______________________________________________________ 12

C. Organization of Climate Work ________________________________________________________________________ 13

STEPPING UP ENGAGEMENT ON CLIMATE IN LINE WITH THE IMF’S MANDATE ___________ 14

A. Direct Country Engagement __________________________________________________________________________ 14

B. Multilateral Surveillance, Analytics, and Policy ______________________________________________________ 22

C. Support Activities ______________________________________________________________________________________ 25

D. Partnering ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 25

ORGANIZATIONAL AND RESOURCE IMPLICATIONS AND RISK ASSESSMENT _______________ 28

A. Organizational Implications___________________________________________________________________________ 28

B. Budgetary and Human Resources Implications _____________________________________________________ 30

C. Risk Assessment _______________________________________________________________________________________ 35

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

CONCLUSIONS __________________________________________________________________________________________ 36

ISSUES FOR DISCUSSION______________________________________________________________________________ 37

References_________________________________________________________________________________________________ 38

BOXES

1. In-Depth Analysis of Mitigation and Associated Transition Risks__________________________________ 16

2. Climate Risk Analysis in FSAPs ________________________________________________________________________ 18

3. Climate Considerations in IMF-Supported Programs _______________________________________________ 20

4. Greening the IMF ______________________________________________________________________________________ 31

TABLES

1. Article IV Consultations: Targeted Outputs __________________________________________________________ 17

2. FSAPs: Targeted Outputs ______________________________________________________________________________ 17

3. Capacity Development: Main Targeted Outputs ____________________________________________________ 22

4. Flagship Reports and Policy Papers: Targeted Outputs ____________________________________________ 23

5. Additional Resource Needs for New Deliverables __________________________________________________ 33

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ADs

Area Departments

AFR

African Department

APD

Asia & Pacific Department

BCBS

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

BIS/FSI

Bank for International Settlements/Financial Stability Institute

CARTAC

Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Center

CAT

Catastrophe

CCPAs

Climate Change Policy Assessments

CCRT

Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust

CD

Capacity Development

CGE

Computable General Equilibrium

CMAP

Climate Macroeconomic Assessment Program

COM

Communications Department

CSF

Corporate Services and Facilities Department

CSR

Comprehensive Surveillance Review

DRSs

Disaster Resilience Strategies

DSA

Debt Sustainability Analysis

DSGE

Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium

ESG

Environmental, Social, and Governance

EUR

European Department

Eurostat

European Statistical Office

FAD

Fiscal Affairs Department

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

FATF

Financial Action Task Force

FIN

Finance Department

FSAP

Financial Sector Assessment Program

FSB

Financial Stability Board

FTE

Full-Time Equivalent

GFSR

Global Financial Stability Report

GHGs

Greenhouse Gases

GIMF

Global Integrated Monetary and Fiscal Model

HQ

Headquarters

ICD

Institute for Capacity Development

ICPF

International Carbon Price Floor

IEA

International Energy Agency

IFIs

International Financial Institutions

IFRS

International Financial Reporting Standards

IMF

International Monetary Fund

ITD

Information Technology Department

LEG

Legal Department

LIC DSF

The Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries

LICs

Low-Income Countries

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

MAC SRDSF

Sovereign Risk and Debt Sustainability Framework for Market Access

Countries

MCD

Middle East and Central Asia Department

MCM

Monetary and Capital Markets Department

NDC

Nationally Determined Contribution

NGOs

Nongovernmental Organizations

NGFS

Network for Greening the Financial System

NOAA

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PFM

Public Financial Management

PFTAC

Pacific Financial Technical Assistance Centre

PIMA

Public Investment Management Assessment

RES

Research Department

SDRs

Special Drawing Rights

SPR

Strategy, Policy, & Review Department

STA

Statistics Department

UN

United Nations

WEMD

World Economic and Market Developments

WEO

World Economic Outlook

WHD

Western Hemisphere Department

WTO

World Trade Organization

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

1. Climate change has emerged as one the most critical macroeconomic policy challenges

that the IMF’s membership will face in the coming years and decades. By contributing to a

higher frequency and intensity of natural disasters, climate change is already causing momentous

challenges for climate-vulnerable countries. In the period ahead, climate change will impact

macroeconomic and financial stability through a variety of other transmission mechanisms. For

example, global warming is likely to affect productivity and GDP, with repercussions for fiscal

positions and public debt trajectories. It is also bound to impact asset valuations and therefore

affect the balance sheets of financial and non-financial firms, which could undermine financial

stability. Climate change will re-distribute income and wealth across the globe, and hence affect

trade flows, exchange rates, and possibly even exchange rate regimes.

2. The policy impact of addressing climate change creates another set of challenges.

Adaptation and resilience building to climate change, for example, often require substantial

investments, which can complicate fiscal management and impair debt sustainability. Preventing

climate change—i.e., climate change mitigation—typically requires significant changes to tax

regimes and regulatory frameworks, complemented by structural and spending policies to support a

just transition. Further, climate change mitigation is a global public good, hence an effective

mitigation strategy needs a global design and requires an unprecedented level of cross-country

policy cooperation and coordination. A transition of the world economy to a low-carbon mode of

production will, in turn, have repercussions for economies that depend on exporting fossil fuels.

3. For the IMF to live up to its mandate, it needs to assist its members in managing these

challenges. However, at this juncture the Fund is inadequately equipped to do so. While the IMF

has been involved in the climate change debate since at least 2008—when a chapter in the World

Economic Outlook identified climate change as “a potentially catastrophic global externality and one

of the world’s greatest collective action problems” (IMF, 2008)—engagement to date has been

mostly ad-hoc and unstructured, with a heavy focus on flagship contributions and policy papers. In

the past few years, demands from the membership for climate-related work have increased

significantly, particularly as regards the IMF’s surveillance and capacity development (CD) activities.

The institution has responded by re-dedicating resources—often on a provisional, temporary

basis—and increasing demands on existing staff. This approach has reached its limits however—it

cannot deliver the comprehensive engagement on climate needed to meet the needs of the

membership.

1

4. Equipping the IMF to deliver on climate has organizational, budgetary, and human

resource management implications. The IMF needs to reinforce its workforce with additional staff

1

For surveillance, a path forward was recently charted in the Comprehensive Surveillance (CSR) review (IMF 2021a).

For Article IV consultations, the CSR established an expectation to regularly cover the mitigation policies of the

20 largest greenhouse gas emitters, and to cover adaptation policies and transition management to a low-carbon

economy whenever the corresponding policy challenges are macro -critical.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

to work on the nexus between macroeconomics and climate issues, and it needs to train its existing

economists to increase their capacity for conducting climate-macro analysis. Specialized hubs with

climate expertise are needed to assist country teams with the coverage of climate-related issues.

Guidance needs to outline how to deal with climate-related challenges in surveillance and in other

activities, while review capacity needs to be built up to ensure that the guidance is applied

consistently and even-handedly to the membership. Partnerships with external stakeholders hold

potential to deliver better services to members by complementing and strengthening the IMF’s own

analysis and expertise. The capacity to deliver CD should increase in line with the growing demand

from the IMF’s members.

5. This paper proposes a strategy how to scale up the IMF’s capacity to deal with climate-

related macroeconomic and financial policy challenges, in order to enable the Fund to assist

its membership effectively. Section II sketches some macroeconomic policy challenges triggered

by climate change. Section III summarizes the IMF’s engagement on climate change to date. Section

IV elaborates on what adequate coverage of climate change would entail. Section V sketches

organizational, budgetary and human resource management implications and provides a risk

assessment. Section VI concludes.

CLIMATE CHANGE: A CRITICAL MACRO-ECONOMIC

POLICY CHALLENGE

Climate change causes momentous macroeconomic and financial policy challenges: it can destroy

wealth, redistribute income between regions and countries, redirect trade, and impact asset

valuations—all phenomena with major repercussions for fiscal, financial, and monetary policy

management. Mitigating and adapting to climate change triggers policy challenges on its own. Most of

these challenges and policy issues are firmly within the IMF’s mandate.

6. Climate change presents a unique and unprecedented global policy challenge.

According to the International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), absent decisive mitigation action,

the global average temperature will exceed the pre-industrial level by 3–5 degrees centigrade by

end-century—thus surpassing temperatures at any time since the emergence of mankind. Warming

at this scale would be bound to trigger seismic ecological, economic, and social shifts. At the same

time, climate change is building up gradually, which renders it difficult to fully appreciate its

significance and implications in real time.

7. In economic terms, climate change is a negative externality with global reach.

Individual households, firms and governments do not sufficiently internalize the impact of their

actions on the world’s climate. Addressing climate change therefore requires not only policy

intervention, but also an unprecedented level of global policy coordination between countries with

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

different economic structures, different levels of development, and different vulnerabilities and

exposures to climate change.

2

8. “Tipping points” are a major source of uncertainty in assessing the damages from

climate change. If critical environmental thresholds are crossed, this could lock in a new climatic

state. An example is the thawing of the permafrost, which would release into the atmosphere large

quantities of CO2 and methane currently locked away under the ice, triggering a runaway

greenhouse effect. Other tipping points include the melting of the Himalayan glacier, changes in

monsoon patterns, the weakening or reversal of ocean currents, and the melting of the Antarctic

and Greenland ice sheets. By harboring the potential for catastrophic outcomes in case of inaction,

tipping points reinforce the rationale for mitigating climate change.

A. Economic Impact

9. Early indicators of the economic damage from climate change are losses associated

with the higher frequency and magnitude of extreme weather events. Natural disasters can

cause enormous human, social and economic cost and are likely to become even more pronounced

as global warming intensifies.

3

Such events include prolonged droughts, large wildfires, intense

heatwaves, torrential rains, floods, hurricanes, or extreme cold periods.

4

Global warming is also

driving trends that are less visible and disruptive in the short term, but carry potentially large

economic cost in the long term, such as rising sea levels, the destruction of habitable lands, the

acidification of oceans, and more frequent outbreaks of vector-borne diseases such as Zika, dengue

and malaria. Other economic transmission mechanisms include lower productivity in agriculture and

fishing, increased climate-related pressures for forced migration, and risk of conflict.

10. There is broad agreement in the economic literature that the effects of rising

temperatures on the level of GDP are non-linear. An increase in the average temperature raises

GDP in countries where annual average temperatures are low, but reduces GDP where they are high,

with the threshold estimated at an annual average temperature of about 13–15C.

5

Some estimates

also suggest an additional impact of warming on growth (e.g., Burke et al., 2015), though this is open

to debate. A transmission mechanism through growth would result in much larger long-term GDP

losses: in the absence of mitigation policies, these could be to the order of 25 percent of GDP by

2100 for the world economy, relative to holding temperatures fixed at current levels.

2

Stern (2007) identifies climate change as “the greatest market failure the world has ever seen.” In April 2021, in an

open letter to world leaders, 101 Nobel laureates called for governments to sign up for a fossil fuel non -proliferation

treaty; see https://fossilfueltreaty.org/nobel-letter.

3

Output losses from natural disasters can be very large. For example, when Hurricane Maria struck Dominica in 2017,

losses were estimated to exceed 200 percent of GDP.

4

Natural disasters can also cause spillovers to other countries. A 2011 flooding in Thailand, for example, halted the

production of hard drives from one of the world’s largest producers, causing a worldwide shortage. Storms that hit

Mozambique in 2019 affected electricity exports to neighboring countries.

5

See Burke, Hsiang and Miguel (2015); Dell, Jones, and Olken (2014); Carleton and Hsiang (2016); and Heal and Park

(2016) for literature reviews. A recent study is Kalkuhl and Wenz (2020).

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

11. Low-income countries (LICs) tend to be disproportionately affected by climate change,

as many LICs are in regions that are already relatively hot. IMF estimates suggest that a

temperature increase of 1C in LICs lowers GDP in the same year by 1.2 percentage points (IMF,

2017). LICs’ vulnerability is reinforced by the fact that they often have less resources to invest in

adaptation and resilience building. They also tend to depend more on climate-vulnerable sectors

such as agriculture, and often suffer from structural weaknesses such as weaker infrastructure, a

higher prevalence of informal housing, lack of public services, weaker social safety nets, and political

fragility, often exacerbated by weak institutions.

6

Some estimates place output losses with

unmitigated climate change at 60–80 percent by 2100 for countries located in hot regions.

7

Given

the strong interconnectedness of the global economy, no country is likely to remain unscathed even

if the worst impacts are initially concentrated in hotter regions.

B. Macroeconomic and Financial Policy Challenges

12. Climate change is bound to trigger major challenges for macroeconomic and financial

policy management. These challenges are likely to materialize through a variety of channels whose

relative importance will differ between countries, reflecting factors such as vulnerability to warming

and extreme weather events, economic structures, or the degree of economic and institutional

development. Examples include:

• Fiscal management and public debt sustainability. Economic losses from climate change are

likely to translate into revenue losses and spending pressures. This will trigger difficult fiscal

policy challenges especially in countries that struggle with constrained fiscal space already.

• Financial stability. Assets and liabilities of financial firms could face large revaluations in

response to physical risks arising from damages to property, infrastructure, and land, and

transition risks that arise in the process of adjusting to a lower-carbon economy (Carney, 2015,

IMF, 2020b). Financial firms are also exposed to physical risks through their underwriting activity,

lending, and portfolio holdings. Liquidity risk can materialize in the form of asset fire sales.

• Monetary policy. As physical risk intensifies, monetary policy can face challenges from greater

volatility in output and prices. Climate change and the policy response to climate change could

also lead to persistent shifts in relative prices (for example, raising the price for fossil fuels), while

the long-term effects of climate change-related policies may affect real interest rates. Monetary

policy needs to internalize and manage these factors (McKibbin and others., 2017).

• Trade, exchange rates and exchange rate regimes. By changing relative prices and

redistributing incomes across the globe, climate change is bound to affect trade flows, with

repercussions for exchange rates. Higher volatility can also complicate adherence to managed

exchange rate regimes, especially when combined with other vulnerabilities (such as high

dollarization or debt levels).

6

IMF (2017) and IMF (2020a).

7

Burke et al. (2015).

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

13. The policy response to climate change can give rise to another set of macroeconomic

and financial policy challenges. Examples include:

• Adaptation and resilience building can be fiscally costly. IMF (2021b), for example, estimates

that for the Asia and Pacific region, annual average investment needs can exceed 3 percent of

GDP—with costs typically falling due upfront, while benefits only accrue in the medium to long

term. Further, needs for resilience building are often the most pressing in countries that already

have elevated public debt levels and limited revenue generating capacity (IMF 2019a). In this

case, domestic fiscal efforts may need to be complemented by support from the international

community to close financing gaps.

8

• Climate change mitigation and the transition to a low-carbon economy typically require

significant changes to tax, spending, and regulatory systems. Accompanying social and

structural policies are needed to ensure a just transition, repurpose human and physical capital,

and build the infrastructure for a low-carbon economy (IMF 2019b, 2020c), including incentives

for low-carbon R&D and targeted support for households and workers. The nature of transition

management needed will often differ greatly between countries, given differences in economic

structures and institutional arrangements. In particular, as mitigation typically involves higher

energy prices, it can require adjustments to development and industrial policy strategies.

• Given the public good character of climate change mitigation, enhancing the effectiveness of

mitigation efforts hinges on international policy coordination. Coordination could prevent

potentially destabilizing spillovers from inadequate mitigation policies to other countries. It

would also help reduce concerns about carbon leakage and competitiveness losses that could

materialize if countries pursue mitigation unliterally. Policy coordination is also needed to ensure

that LICs and other climate-vulnerable countries have sufficient financial and technological

means to purse adaptation and mitigation policies.

• A global transition to a low-carbon economy creates existential challenges for many countries

that depend on fossil fuel exports. A combination of financial diversification (investing export

surpluses in low-carbon assets) and real diversification (developing non-fossil fuel sectors of the

economy) will typically be needed to manage these challenges, with implications for fiscal,

structural and, potentially, exchange rate policies.

IMF ENGAGEMENT ON CLIMATE CHANGE ISSUES TO

DATE

The IMF has been involved in the climate policy debate for many years, with an emphasis on policy

papers and flagship reports in the beginning that was followed by a gradual shift to bilateral country

engagement (Article IVs, FSAPs, CD). In recent years, climate-related demands on IMF staff have

increased greatly, especially in surveillance. To support these demands, the IMF has begun developing

policies at the intersection of macroeconomics and climate, cooperating with a wide range of

8

See, for example the 2018 ECCU Article IV.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

institutions in the process. Until now the IMF has met the additional demands by reallocating resources

within a mostly unchanged budgetary envelope and organizational structure, with an extraordinary

effort made in the past nine months in anticipation of COP26—an approach that has reached its

limits.

A. Direct Country Engagement

14. Climate change has been discussed in the context of Article IV consultation and

Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) reports.

• Article IV Consultations. During 2015–17, 27 climate and energy Article IV pilots discussed

topics such as energy subsidy reform, mitigation policies and resilience building, covering a wide

spectrum of countries. Since then, Article IV consultation reports have covered climate change

on an ad-hoc basis, reflecting requests from country authorities and staff capacity.

o

For climate-vulnerable states, six Article IV consultations (about 2 per year) have been able to

draw on pilot Climate Change Policy Assessments (CCPAs) conducted jointly with the World

Bank.

9

The CCPAs contained in-depth assessments of financing and investment needs and

provided a road map for formulating disaster resilience strategies (DRSs) for climate change

adaptation. For Dominica and Grenada, the country authorities—in collaboration with the

country teams as well as other IFIs—prepared a DRS on their own that was discussed in the

Article IV report.

10

A recent example of adaptation coverage without a CCPA or DRS is the

Maldives’ consultation, which included model-based analysis for prioritizing resilience-

building needs. At present, capacity suffices to cover adaptation issues in about 4–6 Article

IV consultations per year.

o

In cases where mitigation policies and transition management have been covered in-depth,

the discussion in the Article IV report has often been complemented by selected issues or

working papers (see Box 1 for examples). At present, staff capacity suffices to cover

mitigation and transition management in-depth in 4–6 Article IV consultations per year.

• Financial Sector Assessment Programs (FSAPs). Physical and/or transition risks assessment

have been covered on average in two FSAPs per year. Current capacity does not allow climate

risk analysis in all FSAPs, including stress testing and assessments on financial oversight.

15. Climate-related topics are a rapidly increasing area of demand for CD. To date, most CD

has focused on fiscal issues. Where possible and called for on substance, CD is being delivered in

collaboration with institutions like the World Bank, OECD, and the IEA to leverage these institutions’

expertise. The IMF has also started engaging in partnerships with bilateral donors.

11

9

For Belize, Grenada, Micronesia, Seychelles, St. Lucia, and Tonga.

10

The Board was briefed on these in May. The DRS followed IMF (2019a), a paper that concluded that there was a

need for a coherent medium-term approach to help countries prioritize and prepare for natural disasters.

11

For instance, Germany is providing funds for greening the recovery and CD that helps countries design and

implement their climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, while the United Kingdom has provided funds to

(continued)

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

• On fiscal issues—other than the CCPAs mentioned above—CD has covered mitigation and

adaptation policies as well as building resilience. CD has assisted with developing carbon pricing

schemes and related tax policies. There is also initial work to develop CD for public financial

management on issues such as green budgeting and the development of a climate-related

module in public investment management assessments (PIMA).

12

• In the area of financial sector policies, CD is very limited at this point, covering climate-related

stress testing for the insurance sector, regulation and supervision of climate-related risks,

climate-related debt management, and green bonds.

• Some modelling support has covered the domestic macroeconomic, external, and distributional

implications of climate-related policies.

• To support training in member countries, a climate module is part of the newly launched

Inclusive Growth online course, and work is ongoing to develop a model-based framework on

mitigation and adaptation. Moreover, there are plans for interactive microlearning videos.

B. Multilateral Surveillance, Analytics, and Policy

16. Climate change related issues have featured in numerous flagships and policy papers

since 2008, when the first World Economic Outlook’s (WEO) climate chapter was published.

13

The

work on flagships and policy papers has often involved modeling support and instigated the

development of toolkits.

• Flagships. Staff has published many impactful analyses on climate-related topics in flagships

(WEO, GFSR, Fiscal Monitor) and Regional Economic Outlook papers. These contributions have

focused on a wide variety of issues, including (i) developing a conceptual and quantitative

framework for carbon pricing;

14

(ii) making a case for stress testing to climate risks and

promoting climate-related disclosures;

15

(iii) highlighting the economic impact of climate change

CARTAC to help member countries with CD to build climate change and disaster resilience, and Switzerland is

financing the IMF Climate Innovation Challenge, launched in June 2021.

12

Climate PIMAs focus on (i) climate-aware planning—whether public investment is planned considering climate

change policies, (ii) coordination between entities—how decision making on climate-related investment is

coordinated across the public sector, (iii) project appraisal and selection—in particular the reflection of climate-

related analysis and criteria, (iv) budgeting and portfolio management—how the government’s portfolio of climate-

related public investment projects is managed, and (v) risk management—how the government identifies and

manages its fiscal risk exposure associated with public investment that could be impacted by climate change and

natural disasters.

13

The April 2008 WEO (IMF, 2008) analyzed a variety of mitigation policies, with a recommendation for global and

equitable carbon pricing.

14

The October 2019 Fiscal Monitor (IMF, 2019b) provided a quantitative framework for understanding the impacts

and trade-offs of carbon taxes and similar pricing schemes to implement climate mitigation strategies, particularly in

the largest advanced and emerging economies.

15

The October 2019 GFSR (IMF, 2019c) covered developments in ESG markets (issuance, pricing, policy issues like

disclosures); the April 2020 GFSR (IMF, 2020b) looked at whether climate physical risks were properly priced in global

equity markets; the October 2020 GFSR offered an initial assessment of the impact of the COVID crisis on firms’

(continued)

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

and its policy implications on LICs, and on sub-Saharan Africa in particular;

16

and (iv) devising a

strategy of how to deliver global emissions reductions while minimizing economic and social

cost during the transition.

17

• Policy papers have also discussed a wide variety of climate-related topics and policies, such as

energy subsidy reform, mitigation policies, resilience building to natural disasters, state-

contingent debt instruments for climate vulnerable countries, or macroeconomic and

distributional trade-offs of different mitigation policies in the European Union and in Asian

economies.

18

17. Various strands of work aim to improve climate data for macroeconomic and financial

analysis. The IMF launched in April an experimental climate change indicators dashboard.

19

With

climate data for macroeconomic analysis being a relatively new statistical area, much work has gone

into establishing and improving methodologies.

20

Staff is also analyzing the main commercial data

and analytics solutions currently available in the market.

C. Organization of Climate Work

18. To date, climate work is conducted mostly within pre-existing structures. Formal

organizational changes have been very limited and have included (i) the creation of a Climate

Advisory Group (2019) that consists of managerial staff from all departments and meets at least bi-

monthly to disseminate information and coordinate climate work, (ii) the designation of a Deputy

Director in SPR as the Fund-wide climate change coordinator (2020), and (iii) the creation of a

climate policy group in FAD (also 2020). Further, several departments have set up networks to

collaborate on climate issues, and there is also a Fund-wide, informal network of economists who

are interested in climate issues. Other than this, many existing divisions and units have taken on

climate work in addition to their other mandates and portfolios, such as the Multilateral Surveillance

Division in RES, the Strategy and Planning Unit in MCM, the Development Issues Strategy Unit in

SPR, the Fiscal Operations 2 and Public Financial Management 2 Divisions in FAD, the Public Affairs

Division in COM, and the Digital Advisory Unit in ITD. All departments partner extensively with

external organizations on climate work (see the next section).

environmental performance (IMF, 2020f). The April 2020 GFSR made the case for stress testing and better disclosures

to improve assessments of physical risks associated with climate change.

16

IMF (2020g).

17

The October 2020 WEO mapped out how a green investment push coupled with steadily rising carbon prices would

allow countries to achieve necessary emissions reductions while containing transition costs.

18

Examples include IMF (2019a, 2020e).

19

The dashboard aims to become a comprehensive aggregator for statistical indicators on climate change,

greenhouse gas emissions from economic activity, trade in environmental goods, green finance, government policies,

and physical and transition risks. See https://climatedata.imf.org/.

20

For instance, staff organized an iLab event on climate data & disclosures during the April 2021 Spring meetings.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

STEPPING UP ENGAGEMENT ON CLIMATE IN LINE

WITH THE IMF’S MANDATE

Serving the needs of the membership requires stepping up climate work in many areas, including an

expansion of coverage in Article IV Consultations and Financial Sector Assessment reports, and a

significant increase in climate-related CD. To be able to deliver these outputs, country teams would

need to be supported with expertise at the conjunction of macroeconomics and climate science,

analytical tools, data, and guidance. The strategy below describes a steady state that is envisaged to be

reached within 3 years.

19. The overarching objective of the IMF’s engagement on climate is to provide high-

quality, granular, and tailored advice to the membership on macroeconomic and financial

policy challenges related to climate change. This would include domestic policy challenges, which

would be addressed mostly in the context of the IMF’s bilateral country engagements (surveillance,

CD and lending), but also global policy challenges—reflecting the global public good character of

climate change mitigation and the ensuing need to coordinate policies. As climate change affects

countries, regions and sectors differently, and as countries’ policy implementation capacity also

differs, IMF analysis needs to be sufficiently granular and differentiated to factor in this

heterogeneity and reflect it adequately in the IMF’s policy advice. Substantial training within the IMF

will be needed to live up to this challenge.

A. Direct Country Engagement

20. Article IV consultation reports should cover climate related policies wherever climate

change triggers macro-critical policy challenges.

21

As detailed below and summarized in Table 1,

staff proposes coverage of climate-related issues in about 60 Article IV consultations per year.

Overall, this would allow covering adaptation and resilience building every 3 years for those

countries that are most vulnerable to climate change. The climate change mitigation policies of

those countries most critical for the global mitigation effort could also be covered every 3 years,

while transition risk management could be covered every 5–6 years for all members.

• Climate Change Adaptation/Resilience Building. Adaptation and resilience building are

potentially relevant for a large portion of the IMF’s membership. IMF (2019a) identified

60 countries—many of them LICs—as particularly vulnerable to climate change, ranging from

exposure to hurricanes and floods to slower-moving phenomena such as draughts. Over time,

the list of climate-vulnerable countries is likely to increase. Adaptation to climate change

requires strategies to build both physical resilience—i.e., climate resilient infrastructure—and

financial resilience—safeguarding the financial capacity to deal with disasters and to build

resilience—with the latter firmly in the realm of the IMF’s mandate. It can also include challenges

21

See IMF (2021a) for a discussion about the relationship of the IMF’s surveillance mandate—as codified in the

Articles of Agreement and the 2012 Integrated Surveillance Decision—and the treatment of climate-change related

policy challenges in Article IV consultations.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

to financial and monetary policies, for example dealing with a higher frequency and amplitude

of supply-side shocks and with changes in relative prices triggered by climate change.

In-depth coverage in Article IVs requires inter alia an assessment of country-specific climate

vulnerabilities, adaptation policies, and financing needs to build resilience. A full, granular

assessment of these issues will often require analysis conducted outside of the Article IV

consultation cycle. The planned Climate Macroeconomic Assessment Program (CMAP) is meant

to provide such analysis and input (see below). For Article IVs that cannot be preceded by a

CMAP, standardized assessments will be needed that would also draw on work by partners.

Overall, a reasonable objective is to cover adaptation and resilience building in all climate-

vulnerable countries every 3 years, with about half accompanied by a CMAP.

• Climate Change Mitigation. The Comprehensive Surveillance Review (CSR) published in May

set forth the expectation that mitigation policies of the 20 largest emitters of greenhouse gases

(GHGs) would be covered every 3 years or so.

22

The approach inscribed in the CSR reflects the

global public goods character of mitigation: while unconstrained global warming poses large

risks to global macroeconomic and financial stability, no country can mitigate climate change on

its own. Rather, success requires a collective effort to which countries can make an adequate

contribution—with the largest impact triggered by mitigation policies of large GHG emitters.

As discussed in IMF (2021a), an Article IV consultation report would be open to different policy

approaches to reach mitigation objectives. Further, they would refrain from assessing mitigation

objectives per se, but would provide relevant context, including a comparison of domestic

mitigation objectives with those of peers.

Living up to the commitment of the CSR will require 6–7 Article IV consultations with in-depth

mitigation coverage per year (Box 1).

• Transition Management to a low-carbon economy. Transition management is a macro-critical

policy challenge for almost every IMF member. It includes domestic policy efforts to achieve a

country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris agreement, as meeting the

NDC often requires changes to tax regimes, regulatory frameworks, and accompanying social

and investment policies.

23

,

24

It also includes challenges arising from the global transition to a

low-carbon economy, such as managing the transition for fossil fuel exporting countries.

33–34 assessments per year with 8–9 going in depth—in particular for carbon exporters—plus

another 25 assessments with a more standardized methodology would allow covering transition

risks for most of the IMF’s membership over a time horizon of 5–6 years.

22

Together, these countries account for more than 80 percent of all GHG emissions.

23

All IMF members but one have committed to an NDC under the Paris agreement, and for most countries significant

policy efforts are needed to achieve their NDCs.

24

Transition risk management to achieve an NDC is closely related to and overlaps with mitigation. The difference is

that transition risk management is a domestic policy challenge that falls under the bilateral surveillance mandate of

the IMF. Mitigation adds another dimension: with mitigation being a global public good, mitig ation policy needs to

be discussed within the global context and falls under the IMF’s multilateral (rather than bilateral) surveillance

mandate. See IMF (2021a) for a detailed discussion of this distinction and the implications.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

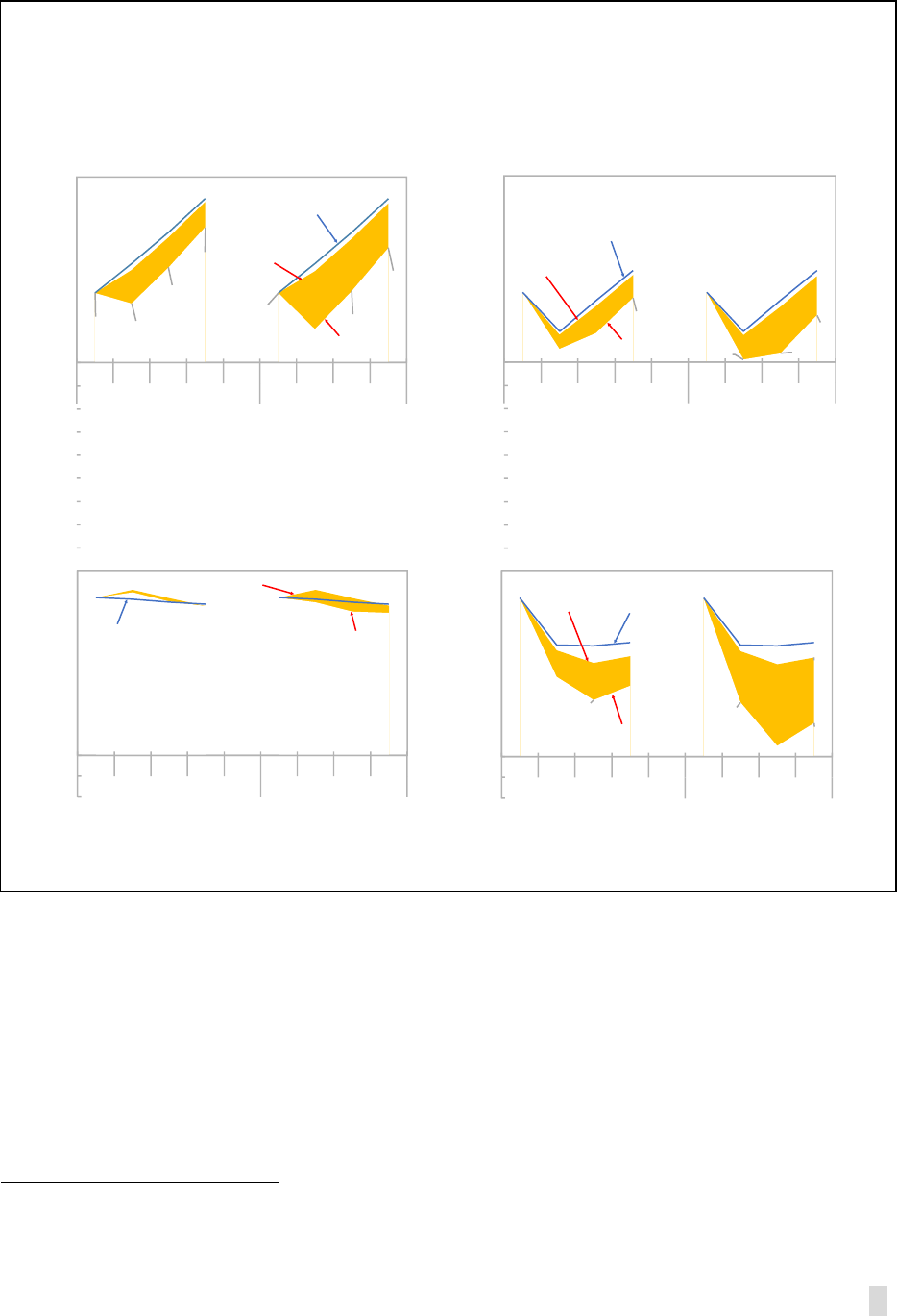

Box 1. In-Depth Analysis of Mitigation and Associated Transition Risks

A thorough analysis of mitigation policy would start with a discussion of historical and anticipated future

emissions trends, emissions sources, emissions and clean technology commitments in the context of the

Paris Agreement and in national plans, and existing and envisioned mitigation policies at the national and

sectoral level. It would also discuss the implications of the country’s NDCs and, where existent, net zero

commitments for mitigation, including an analysis of interim targets and a comparison with peers.

The analysis would present options for mitigation policies, along with quantitative assessments of the

emissions, fiscal, economic efficiency and macroeconomic (GDP, employment, trade) impact. It would also

discuss strategies for enhancing the acceptability of mitigation, particularly in countries where political

economy considerations render carbon pricing difficult. Where feasible, incidence analyses for household

income groups and vulnerable industries would be included.

The assessments would include quantitative

analyses of the emissions, fiscal, and economic

welfare impacts of carbon pricing, including the

prices implicit in countries’ mitigation pledges

(see Figure) and domestic economic co-

benefits (like the reduction of deaths from air

pollution). They would illustrate the trade-offs

(in terms of emissions, costs, and revenue)

between pricing instruments and other policies

like taxes on electricity, taxes on individual

fossil fuels, energy efficiency policies and other

regulations, and sectoral emissions pricing. The

assessments would also provide practical

guidance on how feebates or similar fiscal

instruments can be used to strengthen

mitigation incentives in various sectors (such as

power, industry, transport, building, extractive,

forestry, agriculture) while avoiding new tax

burdens on the average household or firm.

Where data permit, assessments of the

incidence of carbon pricing across household

income groups and vulnerable industries would

also be provided.

Several recent Article IV consultations have included assessments of climate mitigation and transition risk

policies in selected issues or working papers, including Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Indonesia,

Korea, the Netherlands, the U.K., and the U.S. These assessments typically recommended a comprehensive

strategy with carbon pricing as the centerpiece, reinforced with feebates and public investment in clean

technology networks along with productive use of carbon pricing revenues and just transition measures to

protect vulnerable groups.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Argentina

Australia

Brazil

Canada

China

France

Germany

India

Indonesia

Italy

Japan

Mexico

Russia

Saudi Arabia

South Africa

Korea

Turkey

United Kingdom

United States

Percent emissions reductions vs. 2030 baseline

Emissions reductions from $25 carbon price Extra reductions from $50 carbon price

Extra reductions from $75 carbon price NDC target

CO

2

Reductions for 2030 Pledges/ From Pricing

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: NDCs targets are from first-round or (if applicable) second-round Paris pledge. Estimates

assume that CO2 must fall in proportion to other GHGs to achieve the target (i.e. non-CO2 GHGs

must also fall in order for the target to be achieved). Where a country has a conditional NDC the

target is defined as the average between the conditional and unconditional target. NDCs as of 2

June 2021.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

Table 1. Article IV Consultations: Targeted Outputs

Type of Climate-Related Policy Challenge and Objectives

Coverage

Adaptation and Resilience Building.

Objective: cover 60 climate vulnerable countries every 3 years

Based on a CMAP

Without a CMAP

10 per year

10 per year

Climate Change Mitigation

Objective: cover the 20 largest emitters of GHGs every 3 years

In-depth coverage

6–7 per year

Transition Management to a Low-Carbon Economy

Objective: cover all countries every 5–6 years

In-depth coverage

8–9 per year

More standardized coverage

25 per year

Source: Authors.

21. Exposure to climate risk and policy options to manage such risk should become an

integral part of all analyses under the FSAP (Table 2). This would help understand better potential

pressure points for the financial system from physical climate shocks and from the transition to a

low-carbon economy. It would also help inform policies needed to enhance risk management and

the resilience of the financial system.

• Topics. A typical climate component of an FSAP would include stress testing to both physical

and transition risks—with the test design depending on countries’ specific vulnerabilities and

characteristics—as well as assessments of climate-relevant financial regulation and supervision.

To this end, staff plans to develop and implement a standardized approach to assessing financial

stability risks from climate change and the concomitant need for adaptation in the financial

sector, in addition to sector-specific guides (bank and insurance) for inclusion of climate risk in

the assessment of supervision and regulation (see Box 2).

• Assessment process. Staff envisages a three-stage template. First is a climate financial risk

diagnostic to decide on the scope of the assessment and relevant climate physical and transition

risks. The second is designing climate scenarios.

25

The third step would focus on risks that could

Table 2. FSAPs: Targeted Outputs

Deliverables

Coverage

Assess climate issues as part of FSAP risk analysis and assessment of financial

oversight frameworks.

1

All FSAPs, based on

an assessment of

the materiality of

climate risk

Source: Authors.

1/As agreed with county authorities and depending on the systemic importance of climate risk in the jurisdiction.

25

While staff will leverage on NGFS scenarios for transition risks where countries are covered by the NGFS, many

emerging market economies and LICs are not covered. Moreover, the physical risk coverage in NGFS scenarios is

limited to one climate hazard and thus lacks the comprehensiveness needed for FSAP climate stress testing.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

materialize over the three- to five-year FSAP horizon––in contrast with the longer-term focus

adopted by most central banks and regulators––and apply scrutiny to physical risks.

22. Climate-specific review is needed to safeguard quality and evenhanded treatment

across topics and countries. The case for review is especially strong for the coverage of mitigation

policies for the 20 largest emitters of greenhouse gases in Article IV consultations, given that (as per

CSR) regular coverage is strongly encouraged. Review would also be conducted for other in-depth

discussions of climate policies in Article IV reports, selected FSAPs, CMAPs, selected issues papers,

working papers, and for policy papers (see below).

Box 2. Climate Risk Analysis in FSAPs

FSAPs have been assessing the impact of climate-related natural disaster events on financial stability for

some time. A textual analysis of 192 FSAP reports (up to 2019) found that 33 FSAPs (17 percent) contained

meaningful references to risk factors such as droughts, floods, and storms. Many of these FSAPs were for

small island states (such as the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Samoa). Some assessments for advanced economies

(such as Belgium, Denmark, France, Sweden, and the U.S.) have also covered natural catastrophe risks as part

of insurance stress testing.

More recent FSAPs have developed new approaches to assessing climate change risk.

• Norway 2019 FSAP. Three possible transmission channels for transition risk to the financial system were

explored: (i) the impact of a substantial increase in domestic carbon pricing on banks’ health via its effect

on corporates’ operating costs and profitability, (ii) the impact of a large increase in global carbon prices

on the domestic economy and banks’ loan losses via the fall in the revenues of domestic oil producers,

(iii) the impact of a forced reduction in the production of domestic oil firms on their share prices and, in

turn, on the net wealth of domestic shareholders. Results show that a sharp increase in carbon prices

would have a significant but manageable impact on banks (IMF, 2020b and Grippa and Mann, 2020).

• Philippines 2021 FSAP. Climate stress test scenarios were constructed with three distinctive components.

The frequency and intensity of typhoons were projected under a global climate scenario drawing on

climate science inputs. A catastrophe (CAT) risk model used in the property insurance industry was

deployed to estimate damages to infrastructures from typhoons. The resulting damage was applied as

depreciation shock to the capital stock and simultaneous productivity shock based on existing literature

of infrastructure economics in a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model calibrated for the

country. The exercise focused on typhoon risks. The results indicated a relatively moderate impact on

bank capital even for an extreme typhoon on its own. Nonetheless, if multiple types of extreme shocks

materialize at the same time—so-called compound risk such as an extreme typhoon during a pandemic—

the damage could be substantially more amplified.

The oversight section of FSAPs also started to cover climate issues. In the 2020 U.S. FSAP, the regulatory

response to the increasing incidence and severity of natural catastrophes was considered as part of the

assessment of supervision and regulation of the insurance sector. In the 2019 Korea FSAP, the

coordination of climate action across authorities as well as supervisory strategy and major initiatives

among the financial industry were discussed in the Technical Note on Financial Conglomerates

Supervision.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

Box 2. Climate Risk Analysis in FSAPs (concluded)

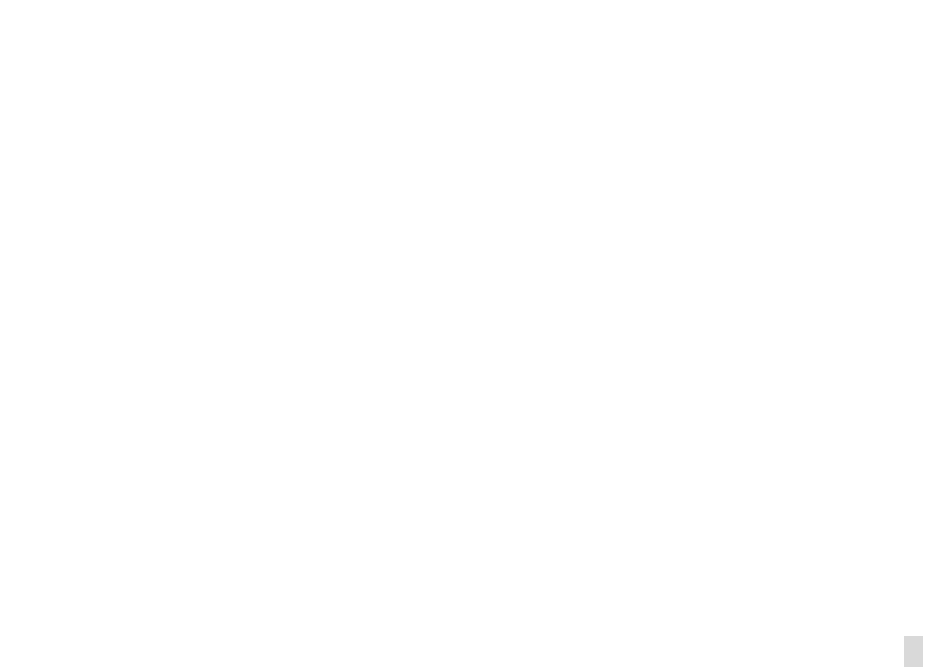

The Philippines: Climate Change Stress Test

Notes: Bank capital ratio of UKB banks.

See Appendix I for methodological details.

1/Bank capital rises in scenarios without pandemic over the short-period due to the valuation gains with securities

(mostly sovereign) as the central bank cut policy rate.

IMF-Supported Programs

23. Within the Fund’s lending mandate, financing may be provided under IMF-supported

programs when climate-related measures are deemed critical to solve a member’s balance-of-

payments (BoP) problems. The IMF is already providing rapid assistance to country hit natural

disasters through its Rapid Financing Instrument and Rapid Credit Facility.

26

Further, to preserve

fiscal sustainability, the IMF has already incorporated climate-related elements—such as energy

26

Moreover, under the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), the Fund can also provide grants for debt

relief for the poorest and most vulnerable countries hit by catastrophic natural disasters or pub lic health disasters.

Macroeconomic assumptions: a severe typhoon is assumed to hit the country in Q3 2020

Macroeconomic Impact of Typhoons-Normal Time

(2019 real GDP = 100)

125

120

115

110

105

100

January WEO

Macroeconomic Impact of Typhoons and Pandemic

(2019 real GDP = 100)

125

120

October WEO

114

Typhoon, once

in 25 years

110

106

98

115

110

105

100

95

90

85

Typhoon, once

in 25 years

100

95

90

85

100

100

100

100

99

Typhoon, once

in 500 years

95

92

Typhoon, once

in 500 years

2019 2020 2021 2022 t

Current scenario

t+1 t+2 t+3

Future scenario

2019

88

2020

91

86

87

2021 2022

Current scenario

t t+1 t+2 t+3

Future scenario

Impact on bank solvency

1

Climate change (the difference between current and future

scenarios) has only a moderate impact on the effect of a

severe typhoon to bank capital during normal time…

Impact of Typhoons on Bank Capital-Normal Time

(Total capital adequacy ratio in percent)

18.0

16.0

14.0

Typhoon, once

in 25 years

…but climate change increases the effects of a severe

typhoon in an extreme tail event—a joint shock of a once

in 500 years typhoon and pandemic.

Impact of Typhoons and Pandemic on Bank Capital

(Total capital adequacy ratio in percent)

18.0

16.0

14.0

15.3

Typhoon, once

in 25 years

15.3

October WEO

12.0

10.0

8.0

6.0

4.0

2.0

0.0

January WEO

Typhoon, once

in 500 years

12.0

10.0

8.0

6.0

4.0

2.0

0.0

10.3

9.7

10.2

9.1

8.9

9.6

7.7

6.8

5.4

5.2

Typhoon, once

in 500 years

3.2

2019 2020 2021 2022

Current scenario

t t+1 t+2 t+3

Future scenario

2019 2020 2021 2022

1.0

t t+1 t+2 t+3

Current scenario

Future scenario

Notes: Bank capital ratio of UKB banks.

See Appendix I for methodological details.

1/ Bank capital rise in scenarios without pandemic over the short-period due to the valuation gains with securities

(mostly sovereign) as the central bank cut policy rate.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

subsidy reform, carbon pricing, and financial resilience building—into some programs (Box 3). Such

measures could be informed by the IMF’s analytical and policy work in the context of its surveillance

activities. Consistent with and constrained by the IMF’s lending mandate, climate-related measures

could be further internalized in program design when such measures are deemed critical for

resolving BoP problems. The ongoing discussion on rechanneling allocated SDRs is also considering

measures to finance climate-supportive measures as part of a range of options.

Capacity Development—Single-Country CD and Training

24. Climate-related CD has several components: (i) the CMAP—a diagnostic tool under

development to analyze climate change policies and preparedness for climate-vulnerable countries,

(ii) climate-related single-country CD, and (iii) external training. Table 3 summarizes the main

outputs envisaged in these areas.

27

25. The CMAP would build on the CCPA, but with a stronger macroeconomic and financial

focus. Among other things, CMAPs would analyze links between resilience building and long-term

27

As per the IMF’s Article of Agreements, CD needs to be consistent with the purposes of the IMF (Art. V.2(b)).

Box 3. Climate Considerations in IMF-Supported Programs

IMF-supported programs (“programs” thereafter) can have an important role in helping build climate-

resilient economies, within the Fund’s lending mandate whereby the IMF provides financing to members in

resolving BoP problems. Climate considerations have already been incorporated in program design in many

countries. In the context of needed fiscal adjustments, a range of “green” measures have been deployed in

several programs:

•

Fuel and energy subsidy reforms have dual BoP-stabilization and climate mitigation effects.

Reducing energy subsidies has been the focus, for instance, in programs for Egypt (2016 EFF);

Tunisia (2016 EFF); Ukraine (2015 EFF).

•

Where revenue mobilization is a priority, programs have helped the authorities introduce new taxes

and otherwise improve their tax systems. This has included widening the range of revenue

mobilization options such as carbon taxation (Jamaica).

•

To support green recovery over the course of fiscal consolidation and to contain possible longer-

term BoP needs, programs have also highlighted the development of coherent resilience-building

strategies (Costa Rica).

•

Members have included natural disaster clauses in new borrowing contracts, which can increase

financial resilience to climate shocks (Barbados, Grenada) in the context of a sovereign debt

restructuring.

Other aspects of program design could also internalize climate considerations, to the extent that they are

consistent with the IMF’s lending mandate. Under program-supported PFM reforms, green budgeting could

help include and track climate-related spending across budget cycle phases. Offsetting distributional

implications of climate-related measures would be critical to building broad support for adjustment in

general and a green recovery. In particular, programs would need to continue prioritizing measures to

protect the poor by establishing targeted cash or near-cash transfers and expanding existing ones.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

growth, climate financing needs, distributional effects of climate policy, and long-term

decarbonization plans. As discussed above, appropriate coverage of climate-vulnerable countries

would require at least 10 CMAPs per year (up from the current delivery of 2), with a view to

informing the corresponding Article IV consultations.

28

Many countries have already signaled

interest in a CMAP.

26. Demand for climate-related single-country CD is expected to increase significantly.

29

A

substantial share of this CD is expected to go to LICs and small states, reflecting both the need to

bolster capacity and the fact that these countries tend to be disproportionately affected by climate

change.

• On fiscal issues there is already considerable CD (see the previous section). Various in-house

mitigation analysis tools are under development for use in CD. Fund staff is providing member

countries—such as Costa Rica, Colombia, Guatemala, Jamaica, Moldova, Seychelles—with fiscal

and economic assessments of the impact of carbon taxes and/or is advising them on green tax

reforms. The increase in CD would focus on green budgeting and climate PIMA; on the latter,

about a dozen countries have already shown interest.

• On financial sector issues, CD would be substantially increased to assist with climate risk stress

testing, financial sector regulation and supervision, monetary policy and central bank operations,

and climate-related debt management issues. Financial Sector Stability Reviews would be a

useful vehicle for delivering climate risk assessments to LICs and small states. Additional delivery

modalities to complement bilateral CD work such as webinars would also be considered.

• In the area of data, the Climate Change Indicators Dashboard would need to be accompanied

by CD to help bolster member countries’ capacity to collect and report the new indicators. While

no CD has been provided in this area as of now, it will be critical to train data compilers so that

they can provide reliable and timely data for policy making. To deliver CD to LICs and small

states, staff considers developing a toolkit for data collection, risk analysis and assessment.

• On macro frameworks, the objective is helping climate-vulnerable countries build macro

scenarios that reflect climate change shocks as well as mitigation and adaptation policies, with a

focus on growth, macroeconomic stability, and debt sustainability.

• On legal and financial integrity issues, single-country CD would cover legal aspects related to

climate change policies in the areas of central banking, financial sector, Public Financial

Management, tax law, governance, anti-corruption and financial integrity.

27. There also is a need to substantially increase external training. Many members are

scaling up climate work, including by establishing climate units in ministries of climate and central

banks. Given a dearth of expertise linking macro and climate science, the IMF can support these

28

Board engagement on a fully fleshed out concept for the CMAP is envisaged for early 2022.

29

Single-country CD would be mindful that digitizing government and financial services be done in a manner that

does not excessively increase the carbon footprint (e.g., adopting green cloud data centers) and that improves

transparency and efficiency in the domains of energy distribution or information sharing.

IMF STRATEGY TO HELP MEMBERS ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE RELATED POLICY CHALLENGES

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

efforts by training more authorities in these areas through dedicated courses, interactive

microlearning videos and webinars—as staff is already doing on a small scale for the Coalition of

Ministers of Finance for Climate Action. All these training methods would bolster the authorities’

capacity to analyze the macroeconomic and financial effects of climate change, natural disaster

shocks, and policies. Climate modules would also be incorporated into existing training cour ses,

including on general macroeconomics, fiscal issues, and financial sector policies.

Table 3. Capacity Development: Main Targeted Outputs

Coverage

Climate Macroeconomic Assessment Program Reports

10 per year

Single-Country CD

87 per year

Fiscal issues

Financial sector issues

Climate data

Macro modeling

Legal and financial integrity issues

10

30

20

15

12

External Training

Online course on the macroeconomics of climate change

5–6 times per year

Micro-learning interactive videos

10

Source: Authors.

B. Multilateral Surveillance, Analytics, and Policy