1

U.S. Department of State, April 2000

Introduction

The US Government continues its commitment to use all tools necessary—including international

diplomacy, law enforcement, intelligence collection and sharing, and military force—to counter

current terrorist threats and hold terrorists accountable for past actions. Terrorists seek refuge in

“swamps” where government control is weak or governments are sympathetic. We seek to drain

these swamps. Through international and domestic legislation and strengthened law enforcement,

the United States seeks to limit the room in which terrorists can move, plan, raise funds, and

operate. Our goal is to eliminate terrorist safehavens, dry up their sources of revenue, break up

their cells, disrupt their movements, and criminalize their behavior. We work closely with other

countries to increase international political will to limit all aspects of terrorists’ efforts.

US counterterrorist policies are tailored to combat what we believe to be the shifting trends in

terrorism. One trend is the shift from well-organized, localized groups supported by state

sponsors to loosely organized, international networks of terrorists. Such a network supported

the failed attempt to smuggle explosives material and detonating devices into Seattle in December.

With the decrease of state funding, these loosely networked individuals and groups have turned

increasingly to other sources of funding, including private sponsorship, narcotrafficking, crime,

and illegal trade. This shift parallels a change from primarily politically motivated terrorism to

terrorism that is more religiously or ideologically motivated. Another trend is the shift eastward

of the locus of terrorism from the Middle East to South Asia, specifically Afghanistan. As most

Middle Eastern governments have strengthened their counterterrorist response, terrorists and

their organizations have sought safehaven in areas where they can operate with impunity.

US Policy Tenets

Our policy has four main elements:

• First, make no concessions to terrorists and strike no deals.

• Second, bring terrorists to justice for their crimes.

• Third, isolate and apply pressure on states that sponsor terrorism to force them to change

their behavior.

• Fourth, bolster the counterterrorist capabilities of those countries that work with the United

States and require assistance.

The US Government uses two primary legislative tools—the designations of state sponsors and

of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs)—as well as bilateral and multilateral efforts to

implement these tenets.

State Sponsors

After extensive research and intelligence analysis, the Department of State designates certain

states as sponsors of terrorism in order to enlist a series of sanctions against them for providing

support for international terrorism. Through these sanctions, the United States seeks to isolate

states from the international community, which condemns and rejects the use of terror as a

legitimate political tool. This year the Department of State has redesignated the same seven states

that have been on the list since 1993: Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Libya, North Korea, Sudan, and Syria.

The designation of state sponsors is not permanent, however. In fact, a primary focus of US

counterterrorist policy is to move state sponsors off the list by delineating clearly what steps

these countries must take to end their support for terrorism and by urging them to take these

steps.

As direct state sponsorship has declined, terrorists increasingly have sought refuge wherever they

can. Some countries on the list have reduced dramatically their direct support of terrorism over

the past years—and this is an encouraging sign. They still are on the list, however, usually for

activity in two categories: harboring of past terrorists (some for more than 20 years) and

continuing their linkages to designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations. Cuba is one of the state

sponsors that falls in this category.

The harboring of past terrorists, although not an active measure, is still significant in terms of US

policy. International terrorists must know unequivocally that they cannot seek haven in states

and “wait out” the period until international pressure diminishes. The US Government

encourages all state sponsors to terminate all links to terrorism— including harboring old “Cold

War terrorists”—and join the international community in observing zero tolerance for terrorism.

Of course, if a state sponsor meets the criteria for being dropped from the terrorism list, it will be

removed—notwithstanding other differences we may have with a country’s other policies and

actions.

There have been encouraging signs recently suggesting that some countries are considering taking

steps to distance themselves from terrorism. North Korea has made some positive statements

condemning terrorism in all its forms. We have outlined clearly to the Government of North

Korea the steps it must take to be removed from the list, all of which are consistent with its

stated policies. A Middle East peace agreement necessarily would address terrorist issues and

would lead to Syria being considered for removal from the list of state sponsors.

In addition to working to move states away from sponsorship, the Department of State

constantly monitors other states whose policies and actions increase the threat to US citizens

living and working abroad.

Areas of Concern

The primary terrorist threats to the United States emanate from two regions, South Asia and the

Middle East. Supported by state sponsors, terrorists live in and operate out of areas in these

regions with impunity. They find refuge and support in countries that are sympathetic to their

use of violence for political gain, derive mutual benefit from harboring terrorists, or simply are

weakly governed. The United States will continue to use the designations of state sponsors and

Foreign Terrorist Organizations, political and economic pressure, and other means as necessary

to compel those states that allow terrorists to live, move, and operate with impunity and those

who provide financial and political patronage for terrorists to end their direct or indirect support

for terrorism.

In South Asia the major terrorist threat comes from Afghanistan, which continues to be the

primary safehaven for terrorists. While not directly hostile to the United States, the Taliban,

which controls the majority of Afghan territory, continues to harbor Usama Bin Ladin and a host

of other terrorists loosely linked to Bin Ladin, who directly threaten the United States and others

in the international community. The Taliban is unwilling to take actions against terrorists trained

in Afghanistan, many of whom have been linked to numerous international terrorist plots,

including the foiled plots in Jordan and Washington State in December 1999. Pakistan continues

to send mixed messages on terrorism. Despite significant and material cooperation in some

areas—particularly arrests and extraditions—the Pakistani Government also has tolerated

terrorists living and moving freely within its territory. Pakistan’s government has supported

groups that engage in violence in Kashmir, and it has provided indirect support for terrorists in

Afghanistan.

In the Middle East, two state sponsors—Iran and Syria—have continued to support regional

terrorist groups that seek to destroy the Middle East peace process. The Iranian Ministry of

Intelligence and Security (MOIS) and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) continue

to provide training, financial, and political support directly to Lebanese Hizballah, HAMAS, and

Palestinian Islamic Jihad operatives who seek to disrupt the peace process. These terrorist

organizations, along with others, are based in Damascus, a situation that the Syrian Government

made little effort to change in 1999. The Syrian Government—through harboring terrorists,

allowing their free movement, and providing resources—continued to be a crucial link in the

terrorist threat emanating from this region during the past year. Lebanon also was a

key—although different—link in the terrorist equation. The Lebanese Government does not

exercise control over many parts of its territory where terrorist groups operate with impunity,

often under Syrian protection, thus leaving Lebanon as another key safehaven for Hizballah,

HAMAS, and several other groups the United States has designated as Foreign Terrorist

Organizations.

Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs)

Secretary Albright in October designated 28 Foreign Terrorist Organizations, dropping three from

the previous list (issued in 1997) and adding one. The removal or addition of groups shows our

effort to maintain a current list that accurately reflects those groups that are foreign, engage in

terrorist activity, and threaten the security of US citizens or the national security of the United

States. The designations make members and representatives of those groups ineligible for US

visas and subject to exclusion from the United States. US financial institutions are required to

block the funds of those groups and of their agents and to report the blocking action to the US

Department of the Treasury. Additionally, it is a criminal offense for US persons or persons

within US jurisdiction knowingly to provide material support or resources to such groups.

As in the case of state sponsorship, the goal of US policy is to eliminate the use of terrorism as a

policy instrument by those organizations it designates as FTOs. Organizations that cease to

engage in terrorist-related activities will be dropped from the list.

A complete list of the designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations is included in Appendix B.

US Diplomatic Efforts

In addition to continuing our cooperation with close allies and friends, such as the United

Kingdom, Canada, Israel, and Japan, we made significant progress on our primary policy

objectives with other key governments and organizations. In 2000 we began a bilateral

counterterrorist working group with India, and we look forward to increasing US-Indian

counterterrorist cooperation in the years ahead.

We worked closely with the Group of Eight (G-8) states and reached a common agreement about

the threat that Iran’s support for terrorist groups poses to the Middle East peace process. In the

meeting in November of counterterrorist experts the G-8 representatives agreed that the Iranian

Government had increased its activities and support for HAMAS, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad,

and Hizballah with the aim of undermining the Middle East peace process. We explored with G-8

partners ways to exert influence on the Iranian Government to end its sponsorship of those

groups.

In 1999 we also expanded our discussions with Russia and initiated dialogues with key Central

Asian states, the Palestinian Authority, and other states eager to cooperate with the United

States and strengthen their ability to counter terrorist threats.

The United States worked closely with the Government of Argentina and other hemispheric

partners to bring about the creation of CICTE, the Organization of American States’ (OAS)

Inter-American Commission on Counterterrorism. As the first chair of CICTE, the United States

worked with other OAS members to develop new means to diminish the terrorist threat in this

hemisphere.

This past summer the United States also hosted an important multilateral conference that brought

together senior counterterrorist officials from more than 20 countries, primarily from the Middle

East, Central Asia, and Asia. The conference promoted international cooperation against

terrorism, the sharing of information on terrorist groups and countermeasures, and the discussion

of policy choices.

After President Clinton issued an Executive Order in July levying sanctions against the Taliban

for harboring terrorist suspect Usama Bin Ladin, the United Nations in October overwhelmingly

passed Security Council Resolution 1267, which imposed a similar set of sanctions against the

Taliban.

On 8 December the UN General Assembly also adopted the International Convention for the

Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, which grew out of the G-8’s initiative to combat

terrorist financing and was drafted and introduced by France. The convention fills an important

gap in international law by expanding the legal framework for international cooperation in the

investigation, prosecution, and extradition of persons who engage in terrorist financing.

The United States conducts a successful program to train foreign law enforcement personnel in

such areas as airport security, bomb detection, maritime security, VIP protection, hostage rescue,

and crisis management. To date, we have trained more than 20,000 representatives from over 100

countries. We also conduct an active research and development program to adapt modern

technology for use in defeating terrorists.

Summary

The United States continues to make progress in fighting terrorism. The policy and programs of

the past 20 years have reduced dramatically the role of state sponsors in directly supporting

terrorism. The threat is shifting, and we are responding accordingly. It is our clear policy goal to

get all seven countries and 28 FTOs out of the terrorist business completely. We seek to have all

state sponsors rejoin the community of nations committed to ending the threat. We must

redouble our efforts, however, to “drain the swamp” in other countries—whether hostile to the

United States or not—where terrorists seek to find safehaven for their planning and operations.

Terrorism will be with us for the foreseeable future. Some terrorists will continue using the most

popular form of terrorism—the truck or car bomb—while others will seek alternative means to

deliver their deadly message, including weapons of mass destruction (WMD) or cyber attacks.

We must remain vigilant to these new threats, and we are preparing ourselves for them.

All terrorists—even a “cyber terrorist”—must occupy physical space to carry out attacks. The

strong political will of states to counter the threat of terrorism remains the crucial variable of our

success.

Note

Adverse mention in this report of individual members of any political, social, ethnic, religious, or

national group is not meant to imply that all members of that group are terrorists. Indeed,

terrorists represent a small minority of dedicated, often fanatical, individuals in most such

groups. It is those small groups—and their actions—that are the subject of this report.

Furthermore, terrorist acts are part of a larger phenomenon of politically inspired violence, and at

times the line between the two can become difficult to draw. To relate terrorist events to the

larger context and to give a feel for the conflicts that spawn violence, this report will discuss

terrorist acts as well as other violent incidents that are not necessarily international terrorism.

Ambassador Michael A. Sheehan

Coordinator for Counterterrorism

Legislative Requirements

This report is submitted in compliance with Title 22 of the United States Code, Section 2656f(a),

which requires the Department of State to provide Congress a full and complete annual report on

terrorism for those countries and groups meeting the criteria of Section (a)(1) and (2) of the Act.

As required by legislation, the report includes detailed assessments of foreign countries where

significant terrorist acts occurred and countries about which Congress was notified during the

preceding five years pursuant to Section 6(j) of the Export Administration Act of 1979 (the so-

called terrorist list countries that repeatedly have provided state support for international

terrorism). In addition, the report includes all relevant information about the previous year’s

activities of individuals, terrorist organizations, or umbrella groups known to be responsible for

the kidnapping or death of any US citizen during the preceding five years, and groups known to

be financed by state sponsors of terrorism.

In 1996, Congress amended the reporting requirements contained in the above-referenced law.

The amended law requires the Department of State to report on the extent to which other

countries cooperate with the United States in apprehending, convicting, and punishing terrorists

responsible for attacking US citizens or interests. The law also requires that this report describe

the extent to which foreign governments are cooperating, or have cooperated during the previous

five years, in preventing future acts of terrorism. As permitted in the amended legislation, the

Department is submitting such information to Congress in a classified annex to this unclassified

report.

Definitions

No one definition of terrorism has gained universal acceptance. For the purposes of this report,

however, we have chosen the definition of terrorism contained in Title 22 of the United States

Code, Section 2656f(d). That statute contains the following definitions:

• The term “terrorism” means premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated

against noncombatant

1

targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents, usually

intended to influence an audience.

• The term “international terrorism” means terrorism involving citizens or the territory of more

than one country.

• The term “terrorist group” means any group practicing, or that has significant subgroups that

practice, international terrorism.

The US Government has employed these definitions of terrorism for statistical and analytical

purposes since 1983.

Domestic terrorism is a more widespread phenomenon than international terrorism. Because

international terrorism has a direct impact on US interests, it is the primary focus of this report.

Nonetheless, the report also describes, but does not provide statistics on, significant

developments in domestic terrorism.

Contents

Introduction iii

The Year in Review 1

Africa Overview 3

Angola 3

Ethiopia 6

Liberia 6

1

For purposes of this definition, the term “noncombatant” is interpreted to include, in addition to civilians, military personnel who at the time of

the incident are unarmed or not on duty. For example, in past reports we have listed as terrorist incidents the murders of the following US military

personnel: Col. James Rowe, killed in Manila in April 1989; Capt. William Nordeen, US defense attache killed in Athens in June 1988; the two

servicemen killed in the La Belle discotheque bombing in West Berlin in April 1986; and the four off-duty US Embassy Marine guards killed in a cafe

in El Salvador in June 1985. We also consider as acts of terrorist attacks on military installations or on armed military personnel when a state of military

hostilities does not exist at the site, such as bombings against US bases in Europe, the Philippines, or elsewhere.

Nigeria 6

Sierra Leone 6

South Africa 6

Uganda 6

Zambia 7

Asia Overview 7

South Asia 7

Afghanistan 7

India 8

Pakistan 8

Sri Lanka 9

East Asia 9

Cambodia 10

Indonesia 10

Japan 11

Philippines 12

Thailand 12

Eurasia Overview 13

Armenia 13

Azerbaijan 13

Georgia 14

Kyrgyzstan 14

Russia 14

Tajikistan 15

Uzbekistan 15

Europe Overview 16

Albania 16

Austria 16

Belgium 17

France 17

Germany 17

Greece 18

Italy 19

Spain 20

Switzerland 20

Turkey 21

United Kingdom 22

Latin America Overview 23

Argentina 24

Colombia 24

Peru 25

Triborder (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay) 25

Middle East Overview 26

Algeria 26

Egypt 27

Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip 27

Jordan 28

Lebanon 30

Saudi Arabia 30

Yemen 32

(Inset) Usama Bin Ladin 31

North America Overview 32

Canada 32

Overview of State-Sponsored Terrorism 33

Cuba 33

Iran 34

Iraq 34

Libya 35

North Korea 36

Sudan 36

Syria 37

(Inset) Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Terrorism 36

Appendixes

A.Chronology of Significant Terrorist Incidents, 1999 39

B.Background Information on Terrorist Groups 65

C.Statistical Review 101

D.Extraditions and Renditions of Terrorists to the United States 1993-99 107

E.International Terrorist Incidents, 1999 Foldout map

Patterns of Global Terrorism: 1999

The Year in Review

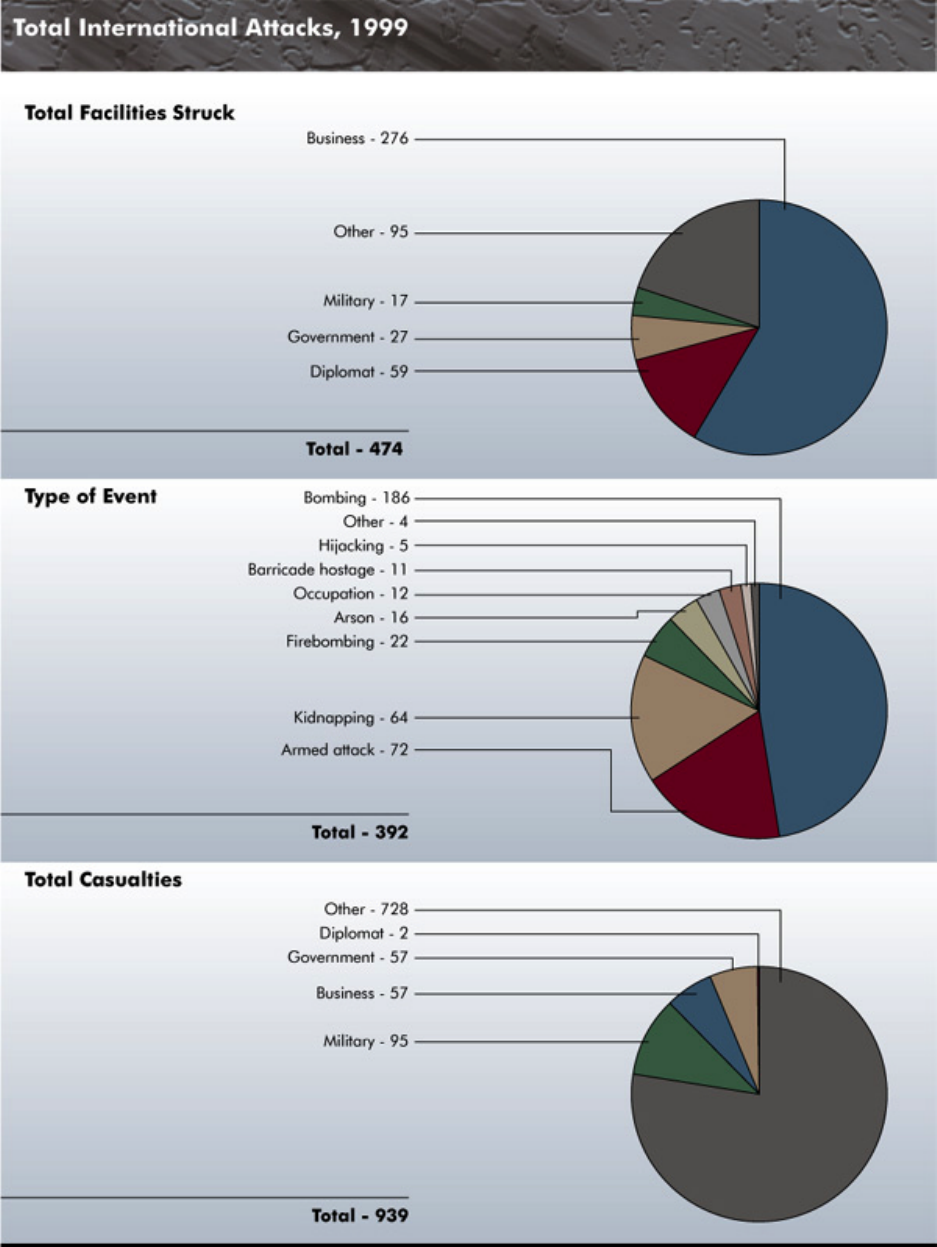

The number of persons killed or wounded in international terrorist attacks during 1999 fell

sharply because of the absence of any attack causing mass casualties. In 1999, 233 persons were

killed and 706 were wounded, as compared with 741 persons killed and 5,952 wounded in 1998.

The number of terrorist attacks rose, however. During 1999, 392 international terrorist attacks

occurred, up 43 percent from the 274 attacks recorded the previous year. The number of attacks

increased in every region of the world except in the Middle East, where six fewer attacks

occurred. There are several reasons for the increase:

• In Europe individuals mounted dozens of attacks to protest the NATO bombing campaign in

Serbia and the Turkish authorities’ capture of Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) terrorist leader

Abdullah Ocalan.

• In addition, radical youth gangs in Nigeria abducted and held for ransom more than three dozen

foreign oil workers. The gangs held most of the hostages for a few days before releasing them

unharmed.

Terrorists targeted US interests in 169 attacks in 1999, an increase of 52 percent from 1998. The

increase was concentrated in four countries: Colombia, Greece, Nigeria, and Yemen.

• In Colombia the number of attacks against US targets, including bombings of commercial

interests and an oil pipeline, rose to 91 in 1999.

• In Greece anti-NATO attacks frequently targeted US interests.

• In Nigeria and Yemen, US citizens were among the foreign nationals abducted.

Five US citizens died in these attacks:

• The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) kidnapped three US citizens working

with the U’Wa Indians in Northeastern Colombia on 25 February. Their bodies were found on

4 March and were identified as Terence Freitas, Ingrid Washinawatok, and Lahe’ena’e Gay.

• A group of Rwandan Hutu rebels from the Interahamwe in the Bwindi Impenetrable National

Park in Uganda kidnapped and then killed two US citizens, Susan Miller and Robert Haubner,

on 1 March.

In 186 incidents in 1999, bombings remained the predominant type of terrorist attack. Since

1968, when the United States Government began keeping such statistics, more than 7,000

terrorist bombings have occurred worldwide.

Law Enforcement

The United States brought the rule of law to bear against international terrorists in several

ongoing cases throughout the year:

• On 19 May the US District Court in the Southern District of New York unsealed an

indictment against Ali Mohammed, charging him with conspiracy to kill US nationals overseas.

Ali, suspected of being a member of Usama Bin Ladin’s al-Qaida terrorist organization, had

been arrested in the United States in September 1998 after testifying before a grand jury

concerning the US Embassy bombings in East Africa.

• Authorities apprehended Khalfan Khamis Mohamed in South Africa on 5 October, after a joint

investigation by the Department of State’s Diplomatic Security Bureau, the Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI), and South African law enforcement authorities. US officials brought him

to New York to face charges in connection with the bombing of the US Embassy in Dar Es

Salaam, Tanzania, on 7 August 1998.

• Three additional suspects in the Tanzanian and Kenyan US Embassy bombings currently are

in custody in the United Kingdom, pending extradition to the United States: Khalid Al-

Fawwaz, Adel Mohammed Abdul Almagid Bary, and Ibrahim Hussein Abdelhadi Eidarous.

Eight other suspects, including Usama Bin Ladin, remain at large. The FBI added Bin Ladin to

its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in June. The Department of State’s Rewards for Justice

program pays up to $5 million for information that leads to the arrest or conviction of these

and other terrorist suspects.

• On 15 October, Siddig Ibrahim Siddig Ali was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his role in a

plot to bomb New York City landmarks and to assassinate Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak

in 1993. Siddig Ali was arrested in June 1993 on conspiracy charges and pleaded guilty in

February 1995 to all charges against him. His cooperation with authorities helped prosecutors

convict Shaykh Umar Abd al-Rahman and nine others for their roles in the bombing

conspiracy.

• In September the US Justice Department informed Hani al-Sayegh, a Saudi Arabian citizen,

that he would be removed from the United States and sent to Saudi Arabia. Authorities

expelled him from the United States to Saudi Arabia on 11 October, where he remains in

custody. He faces charges there in connection with the attack in June 1996 on US forces in

Khubar, Saudi Arabia, that killed 19 US citizens and wounded more than 500 others. Al-

Sayegh was paroled into the United States from Canada in June 1997. After he failed to abide

by an initial plea agreement with the Justice Department concerning a separate case, the State

Department terminated his parole in October 1997 and placed him in removal proceedings.

Africa Overview

Africa in 1999 witnessed no massive terrorist attacks as devastating as the bombings one year

earlier of the US Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, although evidence continued to emerge of

terrorist activity and networks—both indigenous and foreign—on the continent. Terrorist

organizations such as al-Qaida, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the Gama’at al-Islamiyya, and

Hizballah posed a threat to US targets and interests throughout Africa and elsewhere. In the

region’s most deadly attack, Rwandan Hutu rebels murdered two US citizens and a number of

tourists in March.

Angola

Insecurity continued to plague Angola in 1999. Angola’s main guerrilla faction, the National

Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), committed several acts of international

terrorism as a tactic in its decades-old insurrection. In January, UNITA guerrillas ambushed a

vehicle, killing one British national, one Brazilian, and two Angolan security guards. On 10

February, UNITA rebels reportedly kidnapped two Portuguese and two Spanish nationals. The

next day, UNITA rebels attacked the scout vehicle for a convoy of diamond mine vehicles, killing

three Angolan security guards and wounding five others. Five Angolan citizens were killed on 14

April when unidentified assailants attacked a Save the Children vehicle in Salina. UNITA’s

bloodiest terrorist assault was the ambush of a German humanitarian convoy near Bocoio on 6

July. Guerrilla forces killed at least 15 persons and injured 25 others.

In addition to assaults on isolated vehicle convoys, UNITA attacked three civilian aircraft in

1999. On 13 May, UNITA rebels claimed they had shot down a privately owned plane and

abducted three Russian crewmembers. UNITA again claimed responsibility for shooting down a

private aircraft on 30 June. One of the five Russian crewmembers died when the aircraft crash

landed near Capenda-Camulemba. Three weeks later, UNITA rebels fired mortars at an

International Committee for the Red Cross aircraft parked at Huambo airport but caused no

injuries or damage.

Cabinda Liberation Front separatists are believed responsible for the kidnapping in mid-March of

one Angolan, two French, and two Portuguese oil workers in the northern enclave of Cabinda. In

past years the separatists have taken hostages to earn ransom and to pressure the Angolan

Government to relinquish control over the region.

Ethiopia

Ogaden National Liberation Front rebels on 3 April kidnapped a French aid worker, two

Ethiopian staff workers, and four Somalis. The next day, the group’s “political secretary”

announced the French hostage had been “pardoned” and was to be released to French diplomats.

Liberia

Two major kidnapping incidents occurred in Liberia in 1999. On 21 April unidentified assailants

crossed the border from Guinea and laid siege to the town of Voinjama, kidnapping the visiting

Dutch Ambassador, a Norwegian diplomat, a European Union representative, and 17 aid

workers. The attackers, whom eyewitnesses said belonged to the United Liberation Movement

for Democracy in Liberia, released all hostages later the same day. In August an armed gang

kidnapped four British nationals, one Norwegian citizen, and one Italian national. The gang

released them unharmed two days later.

Nigeria

Ethnic violence flared in Nigeria during the year as bloody feuds broke out among various

indigenous groups battling for access to and control of limited local resources. Poverty-stricken

Nigerians across the nation, particularly in the oil-producing southern regions, demanded a larger

share of the nation’s oil wealth. Radical ethnic Ijaw youth resorted to violence against oil firms as

a means of expressing their grievances. The gangs abducted more than three dozen foreign oil

workers, including 16 British nationals and four US citizens. The militant youths demanded

ransoms from the victims’ employers as well as compensation from the government on behalf of

their village, ethnic group, or larger community. In most cases the youths held the hostages for

only a few days before releasing them unharmed.

Sierra Leone

Security problems in Sierra Leone spiked during the first half of 1999 as insurgent forces

mounted a last-gasp offensive on the capital in January. Revolutionary United Front (RUF)

rebels took captive several foreign missionaries during the RUF’s siege of Freetown. The failure

of this offensive and a general sense of battle fatigue led guerrilla forces to sign a peace and cease-

fire agreement in July, and Sierra Leone remained relatively calm for the remainder of the year.

Violent flareups occurred sporadically, however, as the government tried to regain control of the

countryside.

The most significant of the post-cease-fire incidents was the kidnapping of more than three

dozen foreign nationals at a rebel demobilization and prisoner exchange ceremony. On 4 August

members of an Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) faction kidnapped 10 United

Nations military observers, 14 regional peacekeepers, and eight civilians. Among the hostages

were 14 Nigerian soldiers, seven British nationals, three Zambians, and two US citizens. The

AFRC militants demanded the release of their leader, Johnny Paul Koromah, and humanitarian

aid. After Koromah assured them that he was not imprisoned in the capital, the AFRC militants

released most of hostages the next day and the rest on 10 August.

South Africa

Islamist militants associated with Qibla and People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (PAGAD)

continued to conduct bombings and other acts of domestic terror in Cape Town. Only two of the

attacks affected foreign interests, when unidentified youths on 8 and 10 January firebombed

Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants in Cape Town, causing major damage but no injuries.

Uganda

On 14 February a pipe bomb exploded inside a crowded bar, killing five persons and injuring 35

others. One Ethiopian and four Ugandans died in the blast. Among the injured were two Swiss

nationals, one Pakistani, one US citizen, and 27 Ugandans. Ugandan authorities blamed the

bombing and a number of other terrorist incidents in the capital on Islamist militants associated

with the Allied Democratic Forces based along the border with the Democratic Republic of

Congo.

Rwandan Hutu rebels attacked three tourist camps in the Bwindi National Forest on 1 March,

kidnapping 14 tourists, including three US citizens, six British nationals, three New Zealanders,

one Australian, and one Canadian. The rebels killed two US citizens, four British nationals, and

two New Zealanders before releasing the others the next day. One month later, on 3 April,

suspected Rwandan Hutu rebels based in the Democratic Republic of Congo again crossed over

into Uganda and attacked a village in Kisoro, killing three persons.

Zambia

At least 16 bombs exploded across Lusaka on 28 February. One bomb exploded inside the

Angolan Embassy, killing one person and causing major damage. Other bombs detonated near

major water pipes, around powerlines, and in parks and residential districts, injuring two

persons. There were no claims of responsibility.

Asia Overview

South Asia

In 1999 the locus of terrorism directed against the United States continued to shift from the

Middle East to South Asia. The Taliban continued to provide safehaven for international

terrorists, particularly Usama Bin Ladin and his network, in the portions of Afghanistan they

controlled. Despite the serious and ongoing dialogue between the Taliban and the United States,

Taliban leadership has refused to comply with a unanimously adopted UNSC resolution

demanding that they turn Bin Ladin over to a country where he can be brought to justice.

The United States made repeated requests to Islamabad to end support for elements harboring

and training terrorists in Afghanistan and urged the Government of Pakistan to close certain

Pakistani religious schools that serve as conduits for terrorism. Credible reports also continued to

indicate official Pakistani support for Kashmiri militant groups, such as the Harakat ul-Mujahidin

(HUM), that engaged in terrorism.

In Sri Lanka the government continued its protracted conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil

Eelam (LTTE).

Afghanistan

Islamist extremists from around the world—including North America; Europe; Africa; the Middle

East; and Central, South, and Southeast Asia—continued to use Afghanistan as a training ground

and base of operations for their worldwide terrorist activities in 1999. The Taliban, which

controlled most Afghan territory, permitted the operation of training and indoctrination facilities

for non-Afghans and provided logistic support to members of various terrorist organizations and

mujahidin, including those waging jihads in Chechnya, Lebanon, Kosovo, Kashmir, and else-

where.

Throughout the year, the Taliban continued to host Usama Bin Ladin—indicted in November

1998 for the bombings of two US Embassies in East Africa—despite US and UN sanctions, a

unanimously adopted United Security Council resolution, and other international pressure to

deliver him to stand trial in the United States or a third country. The United States repeatedly

made clear to the Taliban that they will be held responsible for any terrorist acts undertaken by

Bin Ladin while he is in their territory.

In early December, Jordanian authorities arrested members of a cell linked to Bin Ladin’s al-Qaida

organization—some of whom had undergone explosives and weapons training in

Afghanistan—who were planning terrorist operations against Western tourists visiting holy sites

in Jordan over the millennium holiday.

On 25 December the Taliban permitted hijacked Indian Airlines flight 814 to land at Qandahar

airport after refusing it permission to land the previous day. The hijacking ended on 31 December

when the Indian Government released from prison three individuals linked to Kashmiri militant

groups in return for the release of the passengers aboard the aircraft. The hijackers, who had

murdered one of the Indian passengers during the course of the incident, were allowed to go free.

The Taliban stated that the hijackers, who reportedly are Kashmiri militants, would leave

Afghanistan even if they were unable to obtain political asylum from another country. Their

whereabouts remained unknown at yearend.

India

Security problems persisted in India in 1999 from ongoing insurgencies in Kashmir and the

northeast. Kashmiri militant groups continued to attack Indian Government, military, and civilian

targets in India-held Kashmir and elsewhere in the country. The militants probably bombed a

passenger train traveling from Kashmir to New Delhi on 12 November, killing 13 persons and

wounding 50. Militant groups operating in Kashmir also mounted a grenade attack against a

wedding in Srinagar, Kashmir’s summer capital, which wounded at least 20 wedding participants.

In the northeast, Nagaland’s Chief Minister escaped injury on 29 November when a local

extremist group attacked his convoy. The attack killed two of his guards and injured several

others.

The Indian Government took a number of steps against terrorism at home and abroad. In August

the Indian cabinet ratified the international convention for the suppression of terrorist bombings.

New Delhi also introduced a convention on the suppression of terrorism at the UN General

Assembly meeting. Indian law enforcement authorities continued to cooperate with US officials

to ascertain the fate of four Western hostages—including one US citizen— kidnapped in 1995 in

Indian Kashmir, although the hostages’ whereabouts remained unknown. New Delhi announced

in November 1999 the establishment of a US-India Counterterrorism Working Group, which

aimed to enhance efforts to counter international terrorism worldwide.

Pakistan

Pakistan is one of only three countries that maintains formal diplomatic relations with—and one

of several that supported—Afghanistan’s Taliban, which permitted many known terrorists to

reside and operate in its territory. The United States repeatedly has asked Islamabad to end

support to elements that conduct terrorist training in Afghanistan, to interdict travel of militants

to and from camps in Afghanistan, to prevent militant groups from acquiring weapons, and to

block financial and logistic support to camps in Afghanistan. In addition, the United States has

urged Islamabad to close certain madrasses, or “religious” schools, that actually serve as conduits

for terrorism.

Credible reports continued to indicate official Pakistani support for Kashmiri militant groups that

engage in terrorism, such as the Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM). The hijackers of the Air India

flight reportedly belong to one of these militant groups. One of the HUM leaders, Maulana

Masood Azhar, was freed from an Indian prison in exchange for the hostages on the aircraft in the

Air India hijacking in December and has since returned to Pakistan.

Kashmiri extremist groups continued to operate in Pakistan, raising funds and recruiting new

cadre. The groups were responsible for numerous terrorist attacks in 1999 against civilian targets

in India-held Kashmir and elsewhere in India. Pakistani officials from both Prime Minister Nawaz

Sharif’s government and, after his removal by the military, General Pervez Musharraf’s regime

publicly stated that Pakistan provided diplomatic, political, and moral support for “freedom

fighters” in Kashmir—including the terrorist group Harakat ul-Mujahidin—but denied providing

the militants training or materiel.

On 12 November, shortly after the United Nations authorized sanctions against the Taliban, but

before the sanctions were implemented, unidentified terrorists launched a coordinated rocket

attack against the US Embassy, the American center, and possibly UN offices in Islamabad. The

attacks caused no fatalities but injured a guard and damaged US facilities.

Sectarian and political violence remained a problem in 1999 as Sunni and Shia extremists

conducted attacks against each other, primarily in Punjab Province, and as rival wings of an ethnic

party feuded in Karachi. Pakistan experienced a particularly strong wave of such attacks across

the country in August and September. Domestic violence dropped significantly after the military

coup on 12 October.

In the wake of US diplomatic intervention to end the Kargil conflict that broke out in April

between Pakistan and India, several Pakistani and Kashmiri extremist groups stridently

denounced US interference and activities. Jamiat-e-Ulema Islami leaders, for example, reacted to

US diplomacy in the region by harshly and publicly berating US efforts to bring wanted terrorist

Usama Bin Ladin, who is based in Afghanistan, to justice for his role in the 1998 US Embassy

bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. The imposition of US sanctions on 14 November against

Afghanistan’s Taliban for its continued support for Bin Ladin drew a similar response.

Sri Lanka

The separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which the United States has

designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization, maintained a high level of violence in 1999,

conducting numerous attacks on government, police, civilian, and military targets. President

Chandrika Kumaratunga narrowly escaped an LTTE assassination attempt in December. The

group’s suicide bombers assassinated moderate Tamil politician Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam in July

and killed 34 bystanders at election rallies in December. LTTE gunmen murdered a Tamil

Member of Parliament from Jaffna representing the Eelam People’s Democratic Party and the

leader of a Tamil military unit supporting the Sri Lankan Army.

Over the year, LTTE attacks against police officers killed 50 and wounded 77. Bombings of

buses, trains, and bus terminals in March, April, and September killed four persons and injured

more than 80, and Sri Lankan authorities attributed several bombings of telecommunications and

power facilities to the LTTE. In July an LTTE suicide diver bombed a civilian passenger ferry

while it was in Trincomalee port, and the group’s Sea Tigers naval wing attacked a Chinese vessel

that had come too close to the Sri Lankan coastline. The LTTE allegedly massacred more than 50

civilians in September, apparently retaliating against a Sri Lankan Air Force bombing that killed

21 Tamil civilians. The LTTE is suspected in the shooting death in Jaffna of a regional military

commander for the progovernment People’s Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE)

and may be responsible for bombings at a PLOTE office and a camp in Vavuniya that killed three

and injured seven.

LTTE activity against the Sri Lankan Government centered on the continuing war in the north.

The Sri Lankan military’s offensive to open and secure a ground supply route through LTTE-

held territory suffered a major defeat when the LTTE fought a series of intense battles in early

November and regained control of nearly all land the government had captured in the past two

years. The battles resulted in thousands of casualties on both sides.

There were no confirmed cases of LTTE or other terrorist groups targeting US citizens or

businesses in Sri Lanka in 1999. Nonetheless, the Sri Lankan Government was quick to cooperate

with US requests to enhance security for US personnel and facilities and cooperated fully with

US officials investigating possible violations of US law by international terrorist organizations.

Battlefield requirements forced Sri Lankan security forces to cancel their participation in a senior

crisis management seminar under the Department of State’s Anti-Terrorism Assistance Program

in 1999.

East Asia

The scorecard for terrorism in East Asian nations in 1999 was mixed, with some countries

enjoying significant improvements and others suffering an upswing of attacks. The most positive

development occurred in Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge’s once-deadly threat all but ended

with the group’s dissolution as a viable terrorist organization.

Political disagreements frequently were the inspiration for terrorist acts in East Asia. In Indonesia

the overwhelming East Timor vote in favor of independence provoked violent reprisals by

militias on that island as well as in Jakarta. In addition, a US-owned oil company’s facilities were

targeted in Aceh, Sumatra.

Japan’s Aum Shinrikyo, which was redesignated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in

October, admitted to and apologized for its sarin attack on Tokyo’s subway in 1995. Facing

increasing public pressure, the Japanese Government instituted legal restrictions on the group. In

response, the Aum announced plans to suspend its public activities as of 1 October. The

Government of Japan also continued to seek the extradition of Japanese Red Army (JRA)

members from Lebanon and Thailand.

Several groups in the Philippines engaged in or threatened violent acts. The Communist Party of

the Philippines New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) broke off peace talks in June in retaliation for

the government’s Visiting Forces Agreement with the United States that provides for joint

military training exercises. While the CPP/NPA only threatened to attack US forces, it targeted

Philippine security forces in numerous incidents. Both the separatist group Moro Islamic

Liberation Front (MILF), as well as the redesignated FTO Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), were

blamed for various attacks and kidnappings for ransom.

In Thailand five prodemocracy students staged a takeover on 1 October of the Burmese Embassy

in Bangkok, holding 32 persons hostage, including one US citizen. The incident ended without

violence.

Cambodia

The Khmer Rouge (KR) insurgency ended in 1999 following a series of defections, military

defeats, and the capture of group leader Ta Mok in March. The KR did not conduct international

terrorism in 1999, and the US Government removed it from the list of designated Foreign

Terrorist Organizations. Former KR members, however, still posed an isolated threat in remote

areas of the country. Suspected ex-KR soldiers, for example, attacked a hill tribe in northeastern

Cambodia in July in an apparent criminal incident.

The Cambodian Government worked on drafting a law for the United Nations to assist in

establishing a court to try former KR members who were senior leaders of the regime responsible

for the deaths of up to 2 million persons in Cambodia during the 1975-79 period. A former KR

official warned in September, however, that unrest would resurface if the Cambodian

Government put the KR on trial.

Indonesia

The ballot results on 30 August favoring East Timor’s independence sparked prointegration

militias—armed East Timorese favoring unity with Indonesia—to mount a violent campaign

throughout September against proindependence supporters. A number of militia members

accused the United Nations of manipulating the ballot results, leading some militia units to seek

foreign targets in the province. Incidents included the serious wounding of a US police officer

working for the UN Assistance Mission to East Timor, an attack against the Australian

Ambassador’s vehicle, and an assault against the Australian Consulate in Dili, East Timor’s

capital. Militiamen also allegedly killed a Dutch Financial Times reporter in a Dili suburb on 21

September after his motorcycle driver tried to flee six armed men. In a separate incident the same

day, prointegrationists ambushed a British journalist and a US citizen photographer in Bacau,

east of Dili, but Australian troops later rescued the two.

A prointegration militia leader told former Indonesian Armed Forces Commander General

Wiranto in early September that he would have no regrets about killing nongovernmental

organization or UN persons who supported the proindependence side. Militia threats and attacks

against foreigners, however, dropped dramatically after late September, when the situation began

to stabilize.

Indonesian nationalists, mostly in Jakarta, responded to the referendum and the subsequent

deployment of the International Force for East Timor with protests and low-level violence

against perceived interference in their country’s internal affairs. In late September the Australian

Embassy in Jakarta was the target of almost daily demonstrations that included petrol bombs and

stone throwing. Gunmen fired shots at the Australian Embassy on three separate occasions in

apparent anger over Canberra’s role in the international peacekeeping mission. In addition,

unidentified assailants threw Molotov cocktails at the Australian International School in Jakarta

on 4 October, but no injuries resulted. As of 25 October, pursuant to a UN Security Council

resolution, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor assumed all legislative

and executive authority in East Timor and responsibility for the administration of justice.

Separatist violence flared in other parts of the country, particularly in Aceh, Sumatra, where the

Free Aceh Movement and its sympathizers clashed with Indonesian security forces throughout

the year. The separatists, demanding a referendum on Aceh independence, primarily attacked

Indonesian targets, but US interests in the province suffered collateral damage. Unidentified

assailants, for example, fired at a Mobil Oil bus and burned a Mobil-operated community health

clinic on two separate occasions in late September. Free Papua Movement separatists located in

Irian Jaya did not attack foreign interests but conducted some violent protests and low-level

attacks against Indonesian targets in 1999.

Several small-scale bombings of undetermined motivation also occurred in Indonesia during the

year, including the attack against the National Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta that injured six persons

on 19 April. In addition, unidentified assailants conducted other bombings that injured several

Indonesians in Jakarta’s city center following the presidential election in October.

Japan

Aum Shinrikyo, the Japanese cult that conducted the sarin attack on the Tokyo subway system

in March 1995, continued efforts to rebuild itself in 1999. The group’s recruitment, training,

fundraising—especially a computer business that generated more than $50 million—and property

acquisition, however, provoked numerous police raids and an extensive public backlash that

included protests and citizen-led efforts to monitor and barricade Aum facilities.

In an effort to alleviate public pressure and criticism, Aum leaders in late September announced

the group would suspend its public activities for an indeterminate period beginning 1 October.

The cult openly pledged to close its branch offices, discontinue public gatherings, cease

distribution of propaganda, shut down most of its Internet Web site, and halt property purchases

beyond that required to provide adequate housing for existing members. The cult also said it

would stop using the name “Aum Shinrikyo.” On 1 December, Aum leaders admitted the cult

conducted the sarin attack and other crimes—which they had denied previously—and apologized

publicly for the acts. The cult made its first compensation payment to victims’ families in late

December.

Japanese courts sentenced one Aum member to death and another to life in prison for the subway

attack, while trials for other members involved in the attack remain ongoing. The prosecution of

cult founder Shoko Asahara continued at a sluggish pace, and a verdict remained years away.

Japanese authorities remained concerned over the release in late December of popular former cult

spokesman Fumihiro Joyu—who served a three-and-a-half-year jail sentence for perjury—and

his expected return to the cult as a senior leader. The Japanese parliament in December passed

legislation strengthening government authority to crack down on groups resembling the Aum and

allowing the government to confiscate funds from the group to compensate victims. The Public

Security Investigation Agency stated that it would again seek to outlaw the Aum under the Anti-

Subversive Activities Law. Separately, the Japanese Government continued to seek the

extradition of members of the Japanese Red Army (JRA) from Lebanon and Thailand.

Philippines

The Communist Party of the Philippines New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) broke off peace talks

with the Philippine Government in June after the ratification of the US-Philippine Visiting

Forces Agreement (VFA), which provides a legal framework for joint military training exercises

between Philippine and US armed forces. The CPP/NPA continued to oppose a US military

presence in the country and claimed that the VFA violates the nation’s sovereignty. Communist

insurgents did not target US interests during the year, but a Communist member told the press in

May that guerrillas would target US troops taking part in the joint exercises. Press reporting in

September alleged CPP/ NPA plans to target US Embassy personnel at an unspecified time.

The CPP/NPA continued to target Philippine security forces in 1999. The organization

conducted several ambushes and abductions against Philippine military and police elements in

rural areas throughout the country. The CPP/NPA released most of its hostages unharmed by late

April but still was holding Philippine Army Major Noel Buan and Philippine Police Official

Abelardo Martin at yearend.

The Alex Boncayao Brigade (ABB)—a breakaway CPP/NPA faction—claimed responsibility for

a rifle grenade attack on 2 December against Shell Oil’s headquarters in Manila that injured a

security guard. The attack apparently protested an increase in oil prices.

Islamist extremists also remained active in the southern Philippines, engaging in sporadic clashes

with Philippine Armed Forces and conducting low-level attacks and abductions against civilian

targets. The groups did not attack US interests in 1999, however. The Abu Sayyaf Group

(ASG)—redesignated in 1999 as a Foreign Terrorist Organization—in June abducted two

Belgians and held them captive for five days before releasing them unharmed without ransom.

The ASG still was working to fill a leadership void resulting from the death of Abdurajak

Abubakar Janjalani, who was killed in a clash with the Philippine Army on 18 December 1998.

The Philippine Government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the largest

Philippine Islamist separatist group, marked the opening of peace talks on 25 October.

Nonetheless, both sides continued to engage in low-level clashes. MILF chief Hashim Salamat

told the press in February that the group had received from Usama Bin Ladin funds that it used

to build mosques, health centers, and schools in depressed Muslim communities.

Distinguishing between political and criminal motivation for many of the terrorist-related

activities in the Philippines was difficult, most notably in the numerous cases of kidnapping for

ransom in the south. Both Communist and Islamist insurgents sought to extort funds from

businesses or other organizations in their operating areas, often conducting reprisal operations if

money was not paid. Philippine police officials, for example, said that three separate bomb

attacks in August against a bus company in the southern Philippines may have been the work of

extortionists rather than terrorists.

Thailand

Five prodemocracy students armed with AK-47s and grenades seized the Burmese Embassy in

Bangkok and held 32 hostages on 1 October. The hostages included 20 individuals applying for

visas, one of whom was a US citizen. The terrorists demanded that the Burmese Government

release all political prisoners in Burma and recognize the results of a national election held in

1990. No injuries occurred, and the situation was resolved the next day after the Thai Deputy

Foreign Minister offered himself as a hostage in exchange for the safety of the hostages inside the

Burmese Embassy. The five terrorists and the Deputy Foreign Minister were taken by helicopter

to a remote jungle area on the Thai-Burmese border. The Burmese fled into the jungle. (At least

one and perhaps three of the five were shot to death by Thai security forces on 25 January 2000

after participating in the seizure of a Thai provincial hospital.)

Some low-level bombings and hoax bomb threats also occurred in Thailand during the year,

although no US interests suffered damage. Most of the incidents were directed against Thai

interests, including the bombing of the Democratic Party headquarters in Bangkok on 14 January.

Thai authorities suspect that a bomb found and defused at the construction site of a new post

office in the south on 15 April was planted by members of the separatist New Pattani United

Liberation Organization to avenge government operations against the group.

Eurasia Overview

Five gunmen attacked Armenia’s Parliament in October, killing eight members, including the

Prime Minister and National Assembly Speaker. Later in the year a grenade was thrown at the

Russian Embassy, damaging several cars but causing no injuries.

A major Central Asian regional crisis erupted in Kyrgyzstan when members of the Islamic

Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) twice crossed the border from Tajikistan and took hostages.

Among the several dozen hostages taken in the second incident were four Japanese geologists,

who eventually were released after several nations intervened; ransom was rumored to have been

paid.

Russian cities, including Moscow, were subjected to several bomb attacks, which killed and

injured hundreds of persons. Police accused the attackers of belonging to Chechen and Dagestan

insurgent groups with ties to Usama Bin Ladin and foreign mujahidin but presented no evidence

linking Chechen separatists to the bombings. The attacks prompted Russia to send military

forces into Chechnya to eliminate “foreign terrorists.” Neighboring Caucasus states within the

Russian Federation as well as surrounding countries feared Russia’s military campaign in

Chechnya would increase radicalization of Islamic internal populations and encourage violence

and the spread of instability throughout the region. The Russian campaign into Chechnya also

raised fears in Azerbaijan and Georgia, as well as Russia, that the Chechen insurgents increasingly

would use those countries for financial and logistic support.

Uzbekistan experienced several major attacks by IMU insurgents seeking to overthrow the

government. In February five coordinated car bombs exploded, killing 16 persons, in what the

government labeled an attempt on the President’s life. In September the IMU declared a jihad

against the Uzbekistani Government. In November the IMU was blamed for a violent encounter

outside the capital city of Tashkent that killed 10 Uzbekistani Government officials and 15

insurgents.

Armenia

On 27 October five Armenian gunmen opened fire on a Parliament session, killing eight

government leaders, including Prime Minister Vazgen Sarkisyan and National Assembly Speaker

Karen Demirchyan. The gunmen claimed they were protesting the responsibility of government

officials for dire social and economic conditions in Armenia since the collapse of the Soviet Union

in 1991. The gunmen later surrendered to authorities and at yearend were being detained with 10

other Armenians accused of complicity. An investigation of the incident was ongoing.

Russian facilities in Armenia also came under attack. On 25 November a grenade was thrown into

the Russian Embassy compound in Yerevan, causing no injuries but damaging several cars.

Azerbaijan

Although Azerbaijan did not face a serious threat from international terrorism, it served as a

logistic hub for international mujahidin with ties to terrorist groups, some of whom supported

the Chechen insurgency in Russia. Azerbaijan increased its border controls with Russia when the

Chechen conflict reignited during the year to prevent foreign mujahidin from operating within its

borders.

Georgia

On 13 October terrorists kidnapped seven UN observers near Abkhazia and demanded a

significant ransom for their release. Georgian officials secured the victims’ freedom within two

days, however, without acceding to the kidnappers’ demands.

Georgia also faced spillover violence from the Chechen conflict and, like Azerbaijan, contended

with international mujahidin seeking to use Georgia as a conduit for financial and logistic

assistance to the Chechen fighters. Russia pressured the Georgian Government to introduce

stronger border controls to stop the flow of men and arms. Russian officials also alleged that

armed Chechen fighters entered Georgia with refugees to hide until a possible Chechen

counterattack against Russia in the spring of 2000.

Violence again colored Georgian domestic politics, especially attacks against senior leaders.

Although no attacks were conducted against the President this year, Georgian security officials

disrupted an alleged coup plot in May, and other prominent officials were the victims or targets

of political and criminal violence.

Kyrgyzstan

International terrorism shocked Kyrgyzstan for the first time in August when armed Islamic

Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) militants twice crossed into Kyrgyzstan and instigated a two-

and-one-half-month hostage crisis. From 6 to 13 August, IMU militants from Tajikistan held four

Kyrgyzstanis hostage in southern Kyrgyzstan before they released them without incident and

retreated to Tajikistan. The militants returned in a larger force on 22 August and seized 13

hostages, including four Japanese geologists, their interpreter, a Kyrgyzstani Interior Ministry

general, and several Kyrgyzstani soldiers. IMU militants continued to arrive in subsequent

weeks, numbering as many as 1,000 at the incursion’s peak.

The IMU’s implicit goal was to infiltrate Uzbekistan and destabilize the government. The

militants first demanded safe passage to Uzbekistan; additional demands called for money and a

prisoner exchange. Uzbekistan refused to allow them to enter, leaving Kyrgyzstan’s ill-prepared

security forces to combat the terrorists with Uzbekistani military assistance, Russian logistic

support, and negotiation assistance from other governments. The militants’ guerrilla tactics

enabled them to maintain their position in difficult mountainous terrain, frustrating the

Kyrgyzstani military’s attempts to dislodge them. Observers speculated that only the approach

of winter forced the militants to retreat into Tajikistan, where negotiators were able to facilitate

an agreement between the IMU and Kyrgyzstani representatives.

On 25 October the militants finally released all hostages except a Kyrgystani soldier they had

executed. Kyrgyzstan released an IMU prisoner, but Kyrgyzstani and Japanese officials denied

Japanese press reports that they paid a monetary ransom for the hostages’ release. Although an

agreement stipulated that all IMU militants would leave Tajikistani territory after the hostage

crisis, some IMU militants may have remained in the region. Central Asian officials and most

external observers feared that a similar IMU incursion into Kyrgyzstan or Uzbekistan could

occur in the spring, either from bases in Tajikistan or from terrorist camps in Afghanistan.

Russia

In the fall a series of bombings in Russian cities claimed hundreds of victims and raised concern

about terrorism in the Russian Federation. On 4 September a truck bomb exploded in front of an

apartment complex at a Russian military base in Buynaksk, Dagestan, killing 62 persons and

wounding 174. Authorities discovered a second bomb on the base the same day and disarmed it

before it caused further casualties. On 8 and 13 September powerful explosions demolished two

Moscow apartment buildings, killing more than 200 persons and wounding 200 others. The two

Moscow incidents were similar, with explosive materials placed in rented facilities on the ground

floor of each building and detonated by timing devices in the early morning. The string of bomb

attacks continued when a car bomb exploded in the southern Russian city of Volgodonsk on 16

September, killing 17 persons and wounding more than 500 others.

A caller to Russian authorities claimed responsibility for the Moscow bombings on behalf of the

previously unknown “Dagestan Liberation Army,” but no claims were made for the incidents in

Buynaksk and Volgodonsk. Russian police suspected insurgent groups from Chechnya and

Dagestan conducted the bombings at the behest of Chechen rebel leader Shamil Basayev and the

mujahidin leader known as Ibn al-Khattab, although Russian authorities did not release evidence

to confirm their suspicions. Russian authorities arrested eight individuals and issued warrants for

nine others believed to be hiding in Chechnya but presented no evidence linking Chechen

separatists to the bombings.

In response to the apartment building bombings and to an armed incursion by Basayev and

Khattab into Dagestan from Chechnya, Russian troops entered Chechnya in October in a

campaign to eliminate “foreign terrorists” from the North Caucasus. The forces fighting the

Russian army were mostly ethnic Chechens and supporters from other regions of Russia. They

received some support from foreign mujahidin with extensive links to Middle Eastern, South

Asian, and Central Asian Islamist extremists, as well as to Usama Bin Ladin. At yearend,

Chechen militant activity had been localized in the North Caucasus region, but Russia and

Chechnya’s neighboring states feared increased radicalization of Islamist populations would

encourage violence and spread instability elsewhere in Russia and beyond.

There were few violent political acts against the United States in Russia during the year. Anti-

NATO sentiment during the Kosovo campaign sparked an attack on the US Embassy in Moscow

in late March when a protester unsuccessfully attempted to launch a rocket-propelled grenade

(RPG) at the facility. The perpetrator sprayed the front of the building with machinegun fire

after he failed to launch the RPG. At yearend no progress had been made in identifying or

apprehending the assailant.

Tajikistan

Security for the international community in Tajikistan did not improve in 1999. The US Embassy

in Dushanbe suspended operations in September 1998 because of the Tajikistani Government’s

limited ability to protect the safety of US and foreign personnel there. US personnel were moved

to Almaty, although they travel regularly to Dushanbe.

The IMU’s use of Tajikistan as a staging ground for its incursion into Kyrgyzstan was the most

significant international terrorist activity in Tajikistan in 1999. The IMU militants entered

Kyrgyzstan from bases in Tajikistan and returned to the area with their Japanese and Central

Asian hostages when they fled Kyrgyzstan in late September and October. As part of the

agreement that resolved the incident, the Uzbekistani militants left Tajikistan, although some

IMU fighters may have remained in some regions of the country.

Uzbekistan

On 16 February five coordinated car bombs targeted at Uzbekistani Government facilities

exploded within a two-hour period in downtown Tashkent, killing 16 persons and wounding

more than 100 others. Such an attack was unprecedented in a former Soviet republic. Uzbekistani

officials feared the attacks were aimed at assassinating President Islom Karimov and suspected

the IMU, some of whose members had opposed the Karimov regime for many years. By summer

the government had arrested or questioned hundreds of suspects about their possible involvement

in the bombings. Ultimately the government condemned 11 suspects to death and sentenced more

than 120 others to prison terms.

The IMU threat to Uzbekistan continued, however, with the group’s incursion into Kyrgyzstan

in August. Although the IMU militants did not attack Uzbekistani soil or personnel at the time,

they tried to achieve a foothold in Uzbekistan for future IMU action. The militants in

Kyrgyzstan also publicly declared jihad against the Uzbekistani Government on 3 September.

In November a group of Uzbekistani forest rangers encountered a group of IMU members in a

mountainous region approximately 80 kilometers east of Tashkent. Initially reported to be

bandits, the IMU militants killed four foresters and three Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD)

police. An extensive MVD search-and-destroy operation resulted in the death of 15 suspected

insurgents and three additional MVD special forces officers. During a press conference, the

Minister of the Interior identified some of the insurgents as IMU members who had taken

hostages in Kyrgyzstan in August.

Europe Overview

Europe experienced fewer terrorist incidents and casualties in 1999 than in the previous year.

Strong police and intelligence efforts—particularly in France, Belgium, Germany, Turkey, and

Spain—reduced the threat from Armed Islamic Group (GIA), Revolutionary People’s Liberation

Party/Front (DHKP-C), Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and Basque Fatherland and Liberty

(ETA) terrorists in those countries. Nonetheless, some European governments avoided their

treaty obligations by neglecting to bring PKK terrorist leader Abdullah Ocalan to justice during

his three-month stay in Italy. Greece’s performance against terrorists of all stripes continued to

be feeble, and senior government officials gave Ocalan sanctuary and support. There were signs

of a possible resurgence of leftwing and anarchist terrorism in Italy, where a group claiming to be

the Red Brigades took responsibility for the assassination of Italian labor leader Massimo

D’Antono in May.

In the United Kingdom, the Good Friday accords effectively prolonged the de facto peace while

the various parties continued to seek a resolution through negotiations. The Irish Republican

Army’s refusal to abandon its caches of arms remained the principal stumbling block. Some

breakaway terrorist factions—both Loyalist and Republican— attempted to undermine the

process through low-level bombings and other terrorist activity.

Turkey moved aggressively against the deadly DHKP-C, which attempted a rocket attack in June

against the US Consulate General in Istanbul. Following Abdullah Ocalan’s conviction on capital

offenses, PKK terrorist acts dropped sharply. The decrease possibly reflected a second-tier

leadership decision to heed Ocalan’s request to refrain from conducting terrorist activity.

Albania

Despite Albania’s counterterrorist efforts and commitment to fight terrorism, a lack of resources,

porous borders, and high crime rates continued to provide an environment conducive to terrorist

activity. After senior US officials canceled a visit to Albania in June because of terrorist threats,

Albanian authorities arrested and expelled two Syrians and an Iraqi suspected of terrorist

activities. The men had been arrested in February and charged with falsifying official documents

but were released after serving a prison sentence.

In October, Albanian authorities expelled two other individuals with suspected ties to terrorists,

who officially were in the region to provide humanitarian assistance to refugees. Albanian

authorities suspected the two had connections to Usama Bin Ladin and denied them permission

to return to Albania.

Austria

As with many west European countries, Austria suffered a Kurdish backlash in the aftermath of

the arrest of PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan in Kenya on 16 February. Kurdish demonstrators

almost immediately occupied the Greek and Kenyan Embassies in Vienna, vacating the facilities

peacefully the following day. Kurds also held largely peaceful protest rallies in front of the US

chancery and at numerous other locations across the country. PKK followers subsequently

refrained from violence, focusing instead on rebuilding strained relations with the Austrian

Government and lobbying for Ankara to spare Ocalan’s life. In addition to the PKK, the Kurdish

National Liberation Front—a PKK front organization—continued to operate an office in Vienna.

In the fight against domestic terrorism, an Austrian court in March sentenced Styrian-born Franz

Fuchs to life imprisonment for carrying out a deadly letter-bomb campaign from 1993 to 1997

that killed four members of the Roma minority in Burgenland Province and injured 15 persons in

Austria and Germany. Jurors unanimously found that Fuchs was the sole member of the

fictitious “Bajuvarian Liberation Army” on whose behalf Fuchs had claimed to act.

In a shootout in Vienna in mid-September, Austrian police killed suspected German Red Army

Faction (RAF) terrorist Horst Ludwig-Mayer. Authorities arrested his accomplice, Andrea

Klump, and on 23 December extradited her to Germany to face charges in connection with

membership in the outlawed RAF, possible complicity in an attack against the chairman of the

Deutsche Bank, and involvement in an attack against a NATO installation in Spain in 1988.

Belgium

In September, Belgian police raided a safehouse in Knokke belonging to the Turkish terrorist

group DHKP/C and arrested six individuals believed to be involved in planning and support

activities. During the operation officials seized false documents, detonators, small-caliber

weapons, and ammunition. All six detainees filed appeals, and, at yearend, Belgian authorities

released two of them. The Turkish Government requested the extradition of one group member,

Fehriye Erdal, for participating in the murder in 1996 of a Turkish industrialist.

A claim made in the name of the GIA in July threatened to create a “blood bath” in Belgium

“within 20 days” if Belgian authorities did not release imprisoned group members. Brussels took

the threat seriously but showed resolve in not meeting any of GIA’s demands, and no terrorist

acts followed the missed deadline. In addition, a Belgian court in October convicted Farid

Melouk—a French citizen of Algerian origin previously convicted in absentia by a French court

as an accessory in the Paris metro bombings in 1995—for attempted murder, criminal association,

sedition, and forgery and sentenced him to imprisonment for nine years. In the same month,

Belgium convicted a second GIA member, Ibrahim Azaouaj, for criminal association and

sentenced him to two years in prison.

France

France continued its aggressive efforts to detain and prosecute persons suspected of supporting

Algerian terrorists or terrorist networks in France. Paris requested the extradition of several

suspected Algerian terrorists from the United Kingdom, but the requests remained outstanding at

yearend. In addition, the French Government’s nationwide “Vigi-Pirate” plan—launched in 1998

to prevent a repeat of the Paris metro attacks by Algerian terrorists— remained in effect. Under

the plan, military personnel reinforced police security in Paris and other major cities, particularly

at strategic sites such as metro and train stations and during holiday periods. Vigi-Pirate also

increased border controls and expanded identity checks countrywide.

French officials in January and February arrested David Courtailler and Ahmed Laidouni, who

had received training at a camp affiliated with Usama Bin Ladin in Afghanistan. Laidouni, who

also was charged in connection with the “Roubaix” GIA Faction, and Courtailler remained

imprisoned in France, and a French magistrate was investigating their cases, although there is no

known evidence that they were planning a terrorist act.