UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles

Measuring Linguistic Empathy:

An Experimental Approach to Connecting

Linguistic and Social Psychological Notions of Empathy

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the

requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

in Applied Linguistics

by

Trevor Kann

2017

© Copyright by

Trevor Kann

2017

ii

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION

Measuring Linguistic Empathy:

An Experimental Approach to Connecting

Linguistic and Social Psychological Notions of Empathy

by

Trevor Kann

Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Linguistics

University of California, Los Angeles, 2017

Professor Olga Tsuneko Yokoyama, Chair

This dissertation investigated the relationship between Linguistic Empathy and

Psychological Empathy by implementing a psycholinguistic experiment that measured a

person’s acceptability ratings of sentences with violations of Linguistic Empathy and

correlating them with a measure of the person’s Psychological Empathy. Linguistic

Empathy demonstrates a speaker’s attitude and identification with a person or event in an

utterance (Kuno & Kaburaki, 1977; Kuno, 1987; Silverstein, 1976; Yokoyama, 1986). This

identification is represented in the utterance through a speaker’s unconscious/automatic

selection from grammatically valid options that convey pragmatically different attitudes.

On the other hand, Psychological Empathy is a social psychological notion that allows a

person to understand and experience the emotional reality of others. The capacity for

Psychological Empathy is known to differ among individuals, and assessment of this

capacity is often implemented in a clinical setting to indicate those at risk of conditions

iii

with deficits of Empathy, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder. This study measured

Psychological Empathy with the Empathy Quotient test, which was designed for both

clinical and non-clinical settings (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004).

This study extended the notion of Linguistic Empathy from a linguistic phenomenon

that is represented in speech to a measurable trait in an individual. The measure of

Linguistic Empathy specifies the individual’s capacity to notice and rate sentences that are

grammatically valid but contain unnatural violations of Linguistic Empathy phenomena

(e.g.,

I met Nancy

versus

Nancy met me

). The results of the experiment showed that

Linguistic Empathy is a measurable and systematic trait, and that it has a significant

positive correlation with Psychological Empathy. This correlation suggests that despite

their disparate theoretical origins, Linguistic and Psychological Empathy share a common

information processing component. One important clinical application of the results is to

use a test of Linguistic Empathy as an unbiased screen for individuals at risk for a deficit of

Psychological Empathy.

iv

The dissertation of Trevor Kann is approved.

Eran Zaidel

Jesse Aron Harris

Olga Tsuneko Yokoyama, Committee Chair

University of California, Los Angeles

2017

v

To Jenni,

for challenging and inspiring me

desde Simon Dice

.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

EMPATHY: AN INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

1.0 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

1.1 EMPATHY IN SOCIETY AND LANGUAGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

1.2 GOALS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.2.1 MEASURING LINGUISTIC EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.2.2 CORRELATIONS OF LINGUISTIC EMPATHY

AND PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

1.2.3 METHODOLOGICAL IMPACT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

1.2.4 CONFIRMATIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

1.3 SUMMARIES OF CHAPTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

CHAPTER 2

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND LINGUISTIC NOTIONS OF EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

2.0 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

2.1 PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

2.1.1 AFFECTIVE AND COGNITIVE EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

2.1.2 PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY MEASURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

2.2 LINGUISTIC EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

2.2.1 EMPATHY PERSPECTIVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

2.2.2 EMPATHY HIERARCHIES AND

THEIR PRAGMASEMANTIC CONNECTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

2.2.3 POINT OF VIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

2.2.4 SENTENTIAL TOPICS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

2.2.5 PASSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS AND RECIPROCAL VERBS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

2.2.6 UNIVERSAL AND INDIVIDUAL NOTIONS OF EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

2.3 EMPATHY IN THIS STUDY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

vii

CHAPTER 3

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH TO EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

3.0 INTRODUCTION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

3.1 RATIONALE FOR EXPERIMENTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

3.1.1 MEASURE OF LINGUISTIC EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

3.1.2 MEASURES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

3.1.3 BENEFITS OF LINGUISTIC EXPERIMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

3.2 LINGUISTIC MANIPULATION OF THE STIMULI. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

3.2.1 OPERATIONALIZATION OF EMPATHY HIERARCHIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

3.2.2 TARGET SENTENCES AND CONTEXT SENTENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . 58

3.2.3 CONDITIONS OF THE STIMULI. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

3.3 PREDICTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

3.3.1 STIMULUS TYPES AND EMPATHY HIERARCHIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

3.3.2 EXPERIMENT DESIGN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

3.3.3 SENSITIVITY TO LINGUISTIC EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

3.3.4 CORRELATIONS BETWEEN LINGUISTIC AND

PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

3.4 METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

3.4.1 PARTICIPANTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

3.4.2 STIMULI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

3.4.3 PROCEDURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

CHAPTER 4

EXPERIMENT: CORRELATIONS BETWEEN

LINGUISTIC AND PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

4.0 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

4.1 RESULTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

4.1.1 RECIPROCAL ITEMS AND EXPERIMENT VALIDATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

viii

4.1.1.1 RECIPROCAL DESIGN

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

4.1.1.2 DEFINING CONDITIONS

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

4.1.1.3 LINGUISTIC EMPATHY SENSITIVITY AND

CORRELATIONS WITH PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY (EQ)

. . . . . . 81

4.1.2 ACTIVE/PASSIVE ITEMS AND EXPERIMENT VALIDATION . . . . . . . . . . . 84

4.1.2.1 ACTIVE/PASSIVE DESIGN

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

4.1.2.2 DEFINING CONDITIONS

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

4.1.2.3 LINGUISTIC EMPATHY SENSITIVITY AND

CORRELATIONS WITH PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY (EQ)

. . . . . . 87

4.1.3 COMPARISON ACROSS SENTENCE TYPES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

4.2 DISCUSSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

4.2.1 DEFINING CONDITIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

4.2.2 DIFFERENCE MEASURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

4.2.3 LINGUISTIC EMPATHY MEASURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

4.2.4 IMPLICATIONS FOR THE LINGUISTIC EMPATHY HIERARCHIES . . . . . 94

4.3 LIMITATIONS AND EXTENSIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

CHAPTER 5

CONCLUSIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

5.0 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

5.1 METHODOLOGICAL CONTRIBUTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

5.2 MEASURE OF LINGUISTIC EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

5.3 CONNECTION BETWEEN LINGUISTIC EMPATHY

AND PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPATHY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

5.4 ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL EXTENSIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

5.5 UNDERLYING EMPATHY PROCESSING COMPONENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

ix

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Figure 2.1: Kuno & Kaburaki’s “Empathy and Camera Angles” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Table 3.1: Example Trials, Violations, and Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Table 3.2: Reciprocal Stimulus Matrix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Table 3.3: Active/Passive Stimulus Matrix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Figure 3.1: Sample Trial of the Experiment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Figure 4.1: Mean Ratings, Reciprocal Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Table 4.1: Sample Reciprocal Sentences for the Defining Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Table 4.2: Mean Ratings and Correlations, Reciprocal Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Table 4.3: Mean Ratings and Correlations, Reciprocal Difference Measures . . . . . 81

Figure 4.2: Correlation of EQ and Linguistic Empathy, Reciprocal Sentences . . . . 83

Figure 4.3: Mean Ratings, Active/Passive Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

Table 4.4: Sample Active/Passive Sentences for Defining Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Table 4.5: Mean Ratings and Correlations, Active/Passive Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

Table 4.6: Mean Ratings and Correlations, Active/Passive Difference Measures . . 86

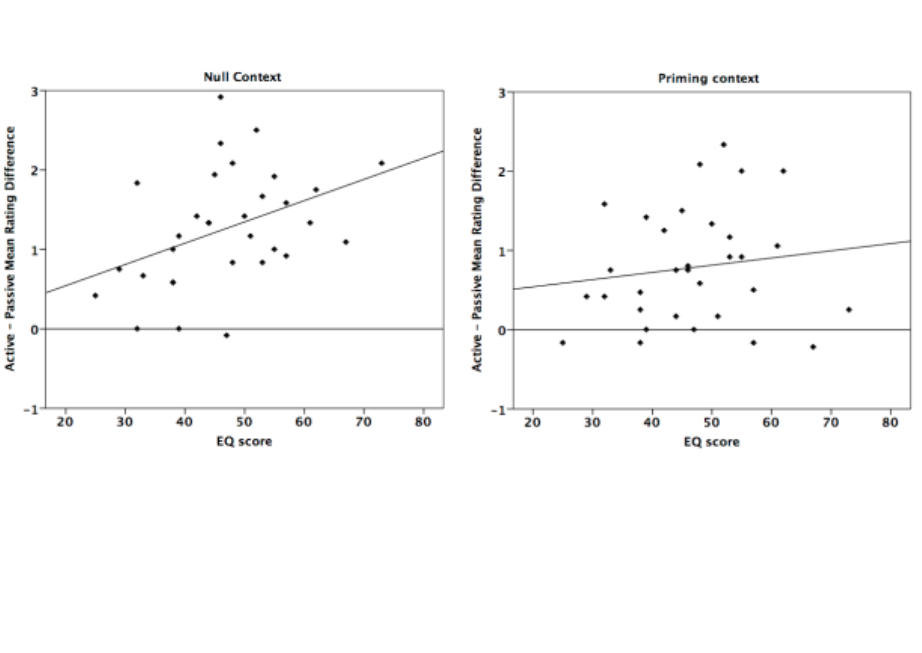

Figure 4.4: Correlation of EQ and Linguistic Empathy, Active/Passive Sentences. . 88

x

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND SPECIAL TERMS

Language/Empathy Terms:

NP Noun Phrase

ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder

EQ Empathy Quotient

HES Hogan Empathy Scale

IRI Interpersonal Reactivity Index

QMEE Questionnaire Measure of Emotional Empathy

Rasch Analysis A method for measuring latent traits like attitude or ability

Statistics Terms:

ANOVA Analysis of Variance: statistical method for testing between

and among groups

SD Standard Deviation

M Mean

SE Standard Error: standard deviation of the sampling

distribution of a statistic

F

Mean of the within group variances

MSE

Mean Squared Error: risk function corresponding to expected

value

p

Probability value of obtaining a result (statistical significance)

η

p

2

Partial Eta Squared: default measure of effect size in ANOVAs

r Correlation Coefficient: measures how closely 2 variables are

related

t-test Assessment of whether 2 groups are statistically different

Fisher Z Test Converts correlations into a normally distributed measure

z Comparison of a test population with a normal population

∑ Sigma: the sum of the values that follow

xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Although my dissertation research has focused on Empathy, what I have learned

about this topic was exponentially eclipsed by the insight I have gained from my loved ones

and from my committee. The Empathy that the people mentioned below have shown me is

the central reason that I have been able to complete this dissertation.

I must first and foremost thank those in my personal life for their love, support, and

patience throughout academic career. Jenni, the passion you exhibit toward everything you

undertake, no matter how daunting the task, is both humbling and inspiring. Since we

were thirteen, the intellectual and emotional fortitude with which you carry yourself have

challenged me to strive in ways I could have never imagined. Mom, you demonstrate more

Empathy than anyone I know, and I live my life hoping to show others the type of kindness

that comes so naturally to you. I owe my love for teaching and entertaining to you. Dad,

without the love you have shown and the sacrifices you have made, I would not have had

the opportunities that I have enjoyed. Also, I know for a fact that others are super grateful

to you for making me as sarcastic as I am. Dylan, without the high academic standards you

set for us, I would have never pursued academia. I could not imagine a funnier, more

thoughtful, and more loving brother (despite always making me turn out the light even

though I was already asleep). Jee, your love and counsel that began in my youth continue to

guide me through the challenges I face. Thank you for being the first to intrigue me with

and expose me to higher educational pursuits. Ardelle, I cannot thank you enough for your

tireless generosity throughout this process; your selflessness astounds me. Finally, I must

acknowledge Mike, who instilled in me a love for teaching and linguistics at an early age,

and always smothered his tutelage and our friendship in a healthy layer of wry humor. I

regret that I could not finish this dissertation in time for him to see its completion.

xii

I will forever be indebted for the guidance, compassion, and understanding that my

committee have exhibited. I am truly humbled by the unbelievable support they continue to

demonstrate through the difficult circumstances I have faced in this dissertation process.

Olga, you have continually exceeded the role of a mentor by providing me with layers upon

layers of support that I never knew I needed. Thanks to your mentorship, you have

motivated me to apply myself and to believe in myself, and you continue to model a

staggering level of dedication to both professional pursuits and personal convictions. I have

always felt encouraged and understood, and with this has come trust and respect for you as

an academic, an advocate, and a friend. Eran, I admire your passion for your work and for

your family, and I appreciate your ability to provoke your colleagues into meaningful

discussion and action. You personify an enviable combination of kindness and brilliance in

an advisor. Jesse, your sharp insight and thoughtful support are astounding, and your

adeptness as a younger academic is inspiring. Thank you also for providing a roof for the

experiments when we were suddenly without one. Finally, John, since I began my graduate

studies, you have embodied what I had hoped was true: that seriousness and levity are not

mutually exclusive in academia. To all of my advisors, I can only aspire to one day provide

mentorship for others with a fraction of effectiveness as you have shown me.

I would also like to acknowledge the generous contributions from the Dr. Ursula

Mandel Endowed Fellowship, which helps to fund research that endeavors to contribute to

the medical field, and to the UCLA Grad Division for the Dissertation Year Fellowship.

Additionally, I would like to thank the Department of Applied Linguistics for the Teaching

Assistance positions and other funding opportunities that have helped me become a more

effective educator and researcher.

Finally, I would also like to acknowledge my colleagues in the research team who

have contributed significantly to the development of this project. Portions of this

xiii

dissertation (primarily segments in chapters 3 and 4) overlap with a co-authored

manuscript that is currently in preparation (cited below). Olga Yokoyama and Eran Zaidel

are responsible for conceiving of and initiating the study, for assembling the wonderful

research team, and for contributing to the co-authored paper below. Additionally, I must

thank Michael Cohen for his brilliance in generating and analyzing the statistics in chapter

4. Despite the contributions from my co-authors, any mistakes in this dissertation are

entirely my own.

Kann, T., Yokoyama, O.T., Cohen, M.S., Gülser, M., Goldknopf, E., Berman, S., Erlikhman,

G., Zaidel, E. (2017).

Linguistic Empathy: Behavioral measures, physiological

correlates and correlation with Psychological Empathy.

Manuscript in preparation.

xiv

VITA

2004 B. A. Linguistics, Portuguese Minor

University of California, Los Angeles

2010 M. A. Applied Linguistics & TESOL

University of California, Los Angeles

PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT

2014 - 2016 Graduate Research Assistant, Zaidel Psychology Lab

University of California, Los Angeles

Department of Psychology

Designed, oversaw, and conducted behavioral and neurophysiological

experiments in psycholinguistics.

2009 - 2016 Teaching Assistant/Teaching Associate/Teaching Fellow/Instructor

University of California, Los Angeles

Department of Applied Linguistics

Courses Taught

:

o Appling 10W: Language in Action

o Appling 30W: Language and Social Interaction

o Appling 40W: Language & Gender

o Appling 101W: Language Learning and Teaching

o Appling 102W: The Nature of Language

o Appling 144M: Fundamentals of Translation

o Appling 161W: Talk and the Body

Department of Linguistics

Course taught:

o Linguistics

1: The Study of Language

Department of Writing Programs

Courses taught:

o ESL 32: Academic Interaction

o ESL 33C: Academic Writing

o ESL 34: Public Speaking

o ESL 38B: Pronunciation

UCLA Anderson School of Business

International Student Summer Program

Speaking/Listening for Business English

2012 - 2013 Instructor of English as a Second Language

Santa Monica Community College

Department of English as a Second Language

Courses taught:

o 11B: Basic English II

o 21B: English Fundamentals II

xv

AWARDS AND HONORS

2015-2016 Dissertation Year Fellowship, UCLA

Awarded on the basis of a thorough dissertation research proposal,

organization and initiative for preliminary findings, and prospective

contributions to the field.

2015-2016 Dr. Ursula Mandel Scholarship, Endowed Fellowship

Awarded to dissertation fellows in scientific fields whose research is of

value to the medical field.

2013 Celce-Murcia Outstanding Teaching Award, UCLA

Received by one student annually. Nominated and awarded by

professors in Applied Linguistics and the Social Sciences for excellence

in teaching performance, mastery of materials, student satisfaction,

and original contributions.

2010-2013 Scholarship, Applied Linguistics, UCLA

PRESENTATIONS

Yokoyama, O. T. & Kann, T. (2014).

EEG methods in pragmatics research

. Paper

presented at the Second Annual American Pragmatics Conference, UCLA, Los

Angeles, CA.

Kann, T. (May 2012).

The prosodical son: The influence of music and other modalities

on evolution of language.

Paper presented at the

11th Annual Conceptual

Structure, Discourse, and Language Conference University of British Columbia,

Vancouver, BC, Canada.

1

CHAPTER 1

EMPATHY: AN INTRODUCTION

Social psychology and linguistics share a term,

Empathy

, to designate two distinct

concepts:

Psychological Empathy

and

Linguistic Empathy

. Psychological Empathy is

described as the ability to “understand emotionally another’s feelings and experience”

(Ehrlich & Ornstein, 2010, p. 4) or as “the ability to see the world through others’ eyes so as

to sense their hurt and pain and to perceive the source of their feelings in the same way as

they do” (Watson, 2002, p. 446). In other words, Psychological Empathy registers a person’s

emotional reactions to others and the emotional understanding involved in these

experiences. Alternatively, Linguistic Empathy is a notion based on perspectives in

linguistic structure that capture a speaker’s attitude toward people and things that are

referenced in an utterance. As defined by Kuno (1987), Linguistic Empathy is “the speaker’s

identification, which may vary in degree, with a person/thing that participates in the event”

(p. 206). Linguistic Empathy is used to explain utterances that differ with respect to the

speaker’s perspective, yet defy standard grammatical explanation. For instance, the

utterances

I met someone last summer

and

Someone met me last summer

are logically and

structurally equivalent; however, the latter seems to be markedly less acceptable than the

former. Similarly, Linguistic Empathy is used to explain lexically correct options at a

speaker’s disposal (e.g., a mother asking her child

Did daddy call?

rather than

Did Terrance

call?

). Psychological Empathy and Linguistic Empathy both involve the understanding and

application of perspective taking; however, there is no consensus of how the two types of

Empathy are related. This study is designed to shed light on this question.

2

1.1 Empathy in Society and Language

The popular use of the term Empathy is often synonymous with compassion. When

people strive to show Empathy, they are attempting to understand the world based on

another’s circumstances and to convey this understanding through a compassionate

response. Although there may be individual and cultural nuances, the implementation of a

version of Empathy exists across cultures. Empathy is universally acknowledged as a

personal and social asset: It can serve as a window into morality (Baier, 1958; Hogan,

1969), it can benefit cross-cultural interaction, and it is a quality that parents endeavor to

impart to their children. Barack Obama has even stressed the personal importance of

learning about Empathy from his mother by using her “simple principle — ‘How would that

make you feel?’ — as a guidepost for [his] politics.” He has also argued that the United

States is “suffering from an empathy deficit” (Obama, 2006, p. 66-67). Ciarrochi et al. (2016)

cite the extensive prosocial benefits of Empathy, from having positive effects on

relationships and communication, to promoting conflict management and emotional

learning.

Although the arguments against Empathy as a prosocial behavior are few, the

promotion of Empathy does convey some inherent drawbacks. First, because Empathy is

highly valued socially and culturally, those who experience a deficit of Empathy on a

clinical level (e.g., Autism Spectrum Disorder, psychopathy, schizoid personality disorder)

can become disadvantaged and disenfranchised. Their lack of Empathy is considered

antisocial and becomes stigmatized. However, for them, a lack of Empathy is not a result of

complacence, selfishness, or cold calculation; it is not a choice. It is a condition that is

ingrained in their neurology, which can be addressed through medical and therapeutic

channels, if desired.

Bloom (2016) describes another drawback with respect to Empathy. He argues that

3

a paradoxical pitfall of Empathy involves a phenomenon where Empathy is more likely to

be triggered when exposed to the harrowing plight of an individual as opposed to the notion

of widespread human tragedy. Logically, the suffering of many should outweigh the

suffering of a single person. Nevertheless, providing personal detail about an individual’s

struggle provides a face to the tragedy, whereas a mass of people loses out on specificity and

poignancy. Bloom argues that Empathy is potentially a cultural downfall for this reason,

and instead, if humans attempted to exercise compassion with more impartiality and logic,

there would be less suffering. This argument suggests that when the experience of

another’s suffering is described as specific, real, and relatable, it becomes a more relevant

target of Empathy than suffering that may be more unjust and tragic. If the suffering

affects a larger population, it becomes more difficult to describe with precision an

experience that affects many. When this specificity is lost, the struggle becomes less

relevant and relatable.

Unfortunate circumstances can feel much more significant for a person when these

details are relevant to this person’s life. Yokoyama (1986) cites the example from the 1980s

of Americans coping with increased gasoline prices, versus the concurrent tragedy of food

shortages experienced by the Polish (p. 148). For most Americans, the issue of gasoline

prices was far more relevant and palpable than the distant issue of Poland’s food shortage,

despite the fact that coping with devastating health issues like starvation and malnutrition

exceeds the struggle of confronting more expensive gas. Relatedly, Yokoyama (1986, pp. 28

ff.) describes the linguistic notion of a

relevance requirement

, in which a message must

contain information that is relevant for the hearer. Yokoyama provides the examples of a

stranger who approaches someone at a train station and utters

you dropped your ticket

.

This utterance is considered relevant and valid to the hearer considering the importance of

a ticket in a train station. However, if the stranger approaches and utters

I’m cooking fish

4

tonight

, this would be irrelevant and invalid from the hearer’s perspective (Yokoyama,

1986, p. 28). When the

relevance requirement

is applied on to Empathy, it suggests that

when a struggle like starvation is distant (e.g., in Poland) or less specific (e.g., a mass of

people), then it is considered less relevant to those who learn of these issues. Linguistic

messages, like descriptions of suffering, become more relatable when the principle of

relevance is observed.

The term Empathy also remains problematic for linguistics. Because Linguistic

Empathy is a little known term outside of the discipline, the notion of Psychological

Empathy is the default for both the layman and academics outside of linguistics. In fact,

Linguistic Empathy is often avoided within the field of linguistics and overshadowed by

traditional notions of syntax. Linguistic Empathy takes a functional view of language

analysis in which grammar and pragmatics are interrelated, and the language participants

(e.g., speaker, author, hearer, addressee) are inseparable from the speech event. This is an

alternative approach to traditional syntax, which endeavors to establish and describe rules

of language by investigating linguistic structure. However, grammar on its own is not the

quintessence of language. Yokoyama (1986) argues that “grammar and pragmatics are

inseparable; they … verbalize both universally human (“phylogenic”) experience, as well as

narrowly personal (“ontogenic”) experience” (p. 186). Linguistic Empathy is a linguistic

phenomenon that is firmly planted in both grammar (e.g., subject/object alternation in

I

met someone last summer

versus

Someone met me last summer

) and pragmatics (e.g.,

speaker/hearer relationship that justifies the utterance

Did daddy call?

). By extension, it

considers both universal human tendencies of language, as well as situational

idiosyncrasies when applied to discourse.

5

1.2 Goals

1.2.1 Measuring Linguistic Empathy. As mentioned, Linguistic Empathy considers

both linguistic structure and individual circumstances when analyzing language behavior

in order to describe a speaker’s identification and point of view with respect to entities

within a sentence. When this linguistic phenomenon is quantified (e.g.,

more

Empathy or

less

Empathy), it refers to the extent to which a speaker shares the perspective with an

entity in a sentence. For instance, the utterance

Joey was hit by Katie

expresses more

Empathy with

Joey

than the utterance

Katie hit Joey

or

Katie hit her neighbor

(in which

her neighbor

and

Joey

are co-referential). Similarly, when Psychological Empathy is

quantified (e.g.,

more

Empathy or

less

Empathy), it can refer to a situation in which an

experiential perspective is shared more or less with others. For example, two people might

have different emotional responses upon learning that someone has broken an arm while

riding a unicycle: One might experience

more

Empathy by feeling upset with the person

and by expressing concern, while another might experience

less

Empathy and instead feel

that this person deserved to have an accident for riding a unicycle.

Unlike Linguistic Empathy, Psychological Empathy is also conceived of in terms of

an individual’s capacity to experience more or less Empathy. Various medical conditions,

such as Autism Spectrum Disorder, are related to deficits of Psychological Empathy.

However, Linguistic Empathy is not currently measured as an individual trait in the same

way that Psychological Empathy can be measured as a screening tool for deficits of

Empathy. Although difficulty in language acquisition and processing is one of the most

prominent symptoms for those who experience a Psychological Empathy deficit, Linguistic

Empathy is not currently conceived of as a quantifiable notion. A primary goal of this study

is to extend the theory of Linguistic Empathy from a notion that describes a speaker’s

6

identification within a speech event to include a measure of a person’s capacity for

experiencing Linguistic Empathy.

1.2.2 Correlations of Linguistic Empathy and Psychological Empathy. A driving

force in this study is to explore the correlations between Linguistic Empathy and

Psychological Empathy. This is examined by issuing a psycholinguistic experiment

designed to probe both notions of Empathy. In this experiment, a person’s capacity to

experience Psychological Empathy is determined through a prevalent measure of

Psychological Empathy, i.e. Empathy Quotient (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). Then,

experimental participants are exposed to sentences that vary in felicitousness, and they are

asked to provide acceptability ratings for these stimuli that manipulate phenomena within

Linguistic Empathy. If a measure of Linguistic Empathy is found (as posited in section

1.2.1), and if this measure correlates significantly with the measure of Psychological

Empathy, then it follows that Linguistic Empathy and Psychological Empathy share more

than a common term, Empathy, and are in fact interrelated phenomena. Uncovering the

extent that this overlap exists is a central goal of this study.

1.2.3 Methodological impact. This dissertation takes a transdisciplinary approach to

assess correlations between Psychological Empathy and Linguistic Empathy. The goals of

this approach, as stated above, are to yield a measure of Linguistic Empathy as well as

establish correlations between Psychological and Linguistic Empathy. The aforementioned

psycholinguistic experiment produces quantifiable results that can apply to both the

linguistic phenomena that are manipulated in the experiment and to the individuals who

participate in the experiment. When the results are analyzed with respect to the linguistic

phenomena, this serves to solidify current understandings of Linguistic Empathy, and to

7

nuance the understanding of the linguistic phenomena that are represented in the

experiment. This methodology is relatively standard in experimental linguistics. However,

when the results are analyzed by applying these results to the participants themselves, this

methodology investigates individual difference factors that can account for variation in

acceptability ratings. The success of the goals in sections 1.2.1 (Linguistic Empathy

measure) and 1.2.2 (correlations of Linguistic and Psychological Empathy) are predicated

on the analysis of the results reflecting individual differences in Empathy processing and

issuing language acceptability ratings. The goal of this methodological approach is to

challenge linguists to examine acceptability judgments in language not only through

grammatical rules that reflect linguistic structure, but through idiosyncratic and pragmatic

accounts of language that reflect individual differences in linguistic capacity.

1.2.4 Confirmations and Extensions of Empathy. In addition to the individual

differences that are investigated in this dissertation, confirmation and extension to existing

Linguistic Empathy theory will be discussed. The experiment provides a quantitative

means to solidify linguistic phenomena within Linguistic Empathy, which can serve as

evidence for a united theory of Linguistic Empathy. Additionally, if Psychological Empathy

is demonstrated as a correlate of Linguistic Empathy, then the extended view of Linguistic

Empathy must accommodate this united view of Empathy.

1.3 Summaries of Chapters

Chapter 2

Chapter 2 of this dissertation examines the notions of Psychological Empathy and

Linguistic Empathy more deeply. One goal of this chapter is to present the disparate

applications of these notions while also demonstrating an overlap in the fundamentals of

8

perspective taking. The chapter investigates the evolution of Psychological Empathy

measures and evaluates strengths and weaknesses of the various approaches, including the

Empathy Quotient test (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). Despite its shortcomings,

Empathy Quotient is presented as an eminent measure of Psychological Empathy, and it

serves as the measure of Psychological Empathy for the subsequent experiment in this

dissertation. Then, the notion of Linguistic Empathy is reviewed, beginning with Empathy

Hierarchies that are posited by Kuno & Kaburaki (1977) and Kuno (1987). The specifics of

three of these hierarchies, the Surface Structure Empathy Hierarchy, the Person Empathy

Hierarchy, and the Topic Empathy Hierarchy, are examined in depth because these

hierarchies were central to creating the stimuli for the experiment in the study.

Additionally, this chapter situates Kuno’s approach with other notions of viewpoint in

linguistics and related fields, and consolidates it with notions of Linguistic Empathy in

other approaches (e.g., Silverstein, 1976; Yokoyama, 1986; Deane, 1992) for a unified

Linguistic Empathy model.

Chapter 3

The purpose of chapter 3 is to bridge the theoretical notions of Empathy discussed in

chapter 2 with a psycholinguistic experimental approach, and to illustrate the methodology

for this approach. This chapter first provides a rationale for the experimental approach.

Next, the specific features of the Linguistic Empathy Hierarchies can be isolated and

operationalized as variables within an experimental setting, so the chapter demonstrates

the process of linguistic manipulation of the stimuli in the experiment. The chapter then

submits specific predictions based on the manipulation of the stimuli, and it concludes by

providing the methodology of the experiment.

9

Chapter 4

The results and discussion of the experiment are presented in chapter 4. The

purpose of this chapter is to present the quantitative evidence that supports the pursuit of

a valid individual measure of Linguistic Empathy as well as a correlation between

Psychological and Linguistic Empathy. The goals of the results are to confirm the

predictions of Linguistic Empathy theory, an individual measure of Linguistic Empathy,

and an Empathy processing component that is common to both Psychological and Linguistic

Empathy. Additionally, the limitations and potential extensions of this experiment are

considered.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5 expands upon the implications of the experiment that were introduced in

the previous chapter. This chapter extends the application of these results into four areas.

First, the implications of a measure of Linguistic Empathy sensitivity are introduced.

Second, the correlations between Psychological Empathy and Linguistic Empathy are

reviewed, and the influence that a test of Linguistic Empathy can exert on Psychological

Empathy measures is discussed. Third, the methodological contributions of experimental

approach challenge linguists to rethink the methods and implications of acquiring native

speaker grammatical judgments. Finally, extensions are proposed for further Linguistic

Empathy and Psychological Empathy experimentation.

10

CHAPTER 2

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND LINGUISTIC NOTIONS OF EMPATHY

This chapter describes varying notions of Psychological and Linguistic Empathies,

including where they overlap and where they diverge. After establishing current

psychological understandings of Empathy, the chapter discusses the means of measuring

an individual’s capacity for Psychological Empathy. The chapter then considers Linguistic

Empathy theory, beginning with the Empathy Hierarchies proposed by Kuno and Kaburaki

(1977) and Kuno (1987), and continuing with notions related to linguistic point of view,

such as animacy (Silverstein, 1976) and entrenchment (Deane, 1992). Next, the chapter

examines the role that passive constructions, reciprocal verbs, and preceding context can

have in Linguistic Empathy. Based on these discussions, the approach to Empathy taken in

this dissertation is then illustrated.

2.1 Psychological Empathy

The term Psychological Empathy in this study is used to refer to the social

psychological notions of Empathy in order to distinguish Psychological Empathy from

Linguistic Empathy. Psychological Empathy refers to the ability of a person to understand

the thoughts and emotions of others, to share in this emotional experience, and to respond

to these situations appropriately. Psychological Empathy allows a person to navigate

productively the social and emotional landscape in which the interaction between the

speaker and others takes place. In the field of psychology, this term is typically discussed in

terms of Affective Empathy and Cognitive Empathy.

11

2.1.1 Affective and Cognitive Empathy. Affective Empathy reflects the emotional

and prosocial component that is applied to seeing the world from another’s perspective. As

defined by Bryant (1982, p. 414), Affective Empathy is “the vicarious emotional response to

the perceived emotional experiences of others.” The emotional responses that comprise

Affective Empathy are typically categorized as either parallel (i.e., experiencing the same

emotion) or reactive (i.e., sympathy, pity, or compassion beyond the experiencer’s emotion)

(Davis, 1980; Lawrence et al., 2004). Crucially, the emotional response must be socially

appropriate to be considered as part of Affective Empathy. Taking delight in another’s

misfortune, for instance, is self-oriented, and therefore not considered a prosocial response

to another person (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004; Lawrence et al., 2004).

Sympathy and Affective Empathy are neither equivalent nor distinct from one

another; they overlap. Davis (1994) cites that the origins of sympathy and Empathy have

different theoretical roots. The concept of sympathy originated from 18

th

century moral

philosophy to describe the emotional response that occurs when a person observes someone

else experiencing a significant emotion. This means that sympathy originates from focusing

on another’s situation, but maintaining one’s own point of view. Contrarily, the concept of

Empathy originates from German aesthetics to describe the phenomenon of a person

inserting her/himself into another’s situation. Thus, a contrast between Empathy and

sympathy is that sympathy maintains a person’s perspective, and Empathy involves

leaving one’s own point of view in order to take another’s (Davis, 1994). Affective Empathy

thereby demands the recognition of another’s emotions and requires the ability to craft an

appropriate emotionally congruent response, which sometimes includes sympathy, and

sometimes includes other emotional responses.

Cognitive Empathy, on the other hand, involves parsing out the emotions and

reactions of Affective Empathy from the unemotional and rational aspects of Empathy. The

12

focus is placed on the ability to understand others’ emotions (Kohler, 1929) as well as

processes like role taking and perspective switching (Mead, 1934). As defined by Hogan

(1969, p. 313), Cognitive Empathy is the “intellectual or imaginative apprehension of

another’s condition or state of mind.” This approach is not necessarily prosocial. If this

person were to exploit or manipulate others with the knowledge that accompanies

emotional understanding, he/she might display a lack of Affective Empathy but a wealth of

Cognitive Empathy. Similarly, Smith (2006) contends that an imbalance of Cognitive and

Affective Empathy is associated with Empathy deficits such as schizoid personality disorder

and antisocial personality disorder, and Jolliffe & Farrington (2006, p. 592) suggest that the

apparent social charm of psychopaths can be attributed to this imbalance. Jolliffe &

Farrington go on to argue that, as a means of identifying this imbalance, it would useful to

have Empathy measures that accurately reflect different facets of Empathy. However,

Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright (2004) maintain that despite the theoretical existence of

multiple facets that Empathy embodies, they are so inherently tied that, empirically, it is

exceedingly difficult to tease them apart.

2.1.2 Psychological Empathy measures. Hogan (1969) argues for the importance of

developing an Empathy measurement in order to quantify concepts directly and indirectly

related to morality, and thus developed a test for measuring these concepts. Developing this

scale, he argues, provides a necessary step toward shifting conceptions of Empathy to a

quantifiable construct. However, Jolliffe & Farrington (2006) argue that a shortcoming of

the Hogan Empathy Scale (HES) is that it does not measure Empathy; rather, it identifies

individuals belonging to high and low Empathy groups based on other conditions. The HES

is no longer considered a valid measure of Cognitive Empathy, but it remains an accurate

predictor of behavior that is indicative of criminal or delinquent behavior (Jolliffe &

13

Farrington, 2006, p. 591).

Other common Empathy measures include the Questionnaire Measure of Emotional

Empathy (QMEE) (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972), which measures Emotional (i.e., Affective)

Empathy, and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) (Davis, 1980), which measures both

Affective and Cognitive Empathy. Both tests are self-reports in which respondents agree or

disagree with statements that are designed to reflect Empathy. However, Jolliffe &

Farrington (2006) argue that some statements falsely equate sympathy and Empathy (e.g.,

“I get very angry when I see someone being ill-treated” [Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972], “other

people’s misfortunes do not usually disturb me a great deal” [Davis, 1980]). While these

statements reflect instances of sympathy (or the lack thereof), Jolliffe & Farrington

consider only the parallel responses of Affective Empathy (i.e., experiencing the same

emotions) and not the reactive responses of Affective Empathy (feelings beyond the

experiencer’s emotions) under their definition of Affective Empathy (2006, pp. 591 ff.). As

such, they argue that questions relating to sympathy (i.e., reactive Affective Empathy)

should be disqualified from Affective Empathy measures. Nevertheless, there appears to be

a consensus that Affective Empathy includes any appropriate parallel or reactive emotional

response (Davis, 1994; Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004; Lawrence et al., 2004).

Additionally, despite the attempts of the QMEE to measure solely Affective

Empathy, the creators of the QMEE (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972) cite that its items were

likely to tap into a single empathic construct that includes both cognitive aspects and

emotional arousal (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). Other critiques of the IRI state

that it does not attempt to measure Cognitive Empathy; rather, they attempt to measure

more general perspective taking ability. In other words, instead of measuring a person’s

ability to understand the emotions of others, the IRI measures the person’s ability to take

another’s perspective without necessarily understanding the emotions involved (Jolliffe &

14

Farrington, 2006).

Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004) justify the need for a unifying test for

Psychological Empathy, citing previous shortcomings of the IRI and QMEE (Baron-Cohen

& Wheelwright, 2004). While previous Empathy measures may accurately express factors

within Empathy (e.g., Cognitive Empathy, empathic concern, etc.), they assert that

Affective and Cognitive Empathy cannot be parsed easily, and one should not be analyzed

without the other. Consequently, Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright sought to develop a

measure of Empathy, Empathy Quotient (EQ), to investigate the relationship between

Empathy and Autism. Baron-Cohen et al. (2001) had already developed a test called the

Autism Spectrum Quotient, but this quotient did not focus on Empathy. They argued that a

lack of Empathy, both affectively (i.e., appropriate emotional responses) and cognitively

(i.e., theory of mind), requires a unifying measure that does not attempt to parse and

measure individual aspects of Empathy.

Initial tests of reliability and replicability for EQ reinforce the validity of the

measure. Lawrence et al. (2004) demonstrate that the EQ test yields strong inter-rater

reliability, test-retest reliability, and correlation with key aspects of the IRI. However, the

study also indicates that social desirability (i.e., not wanting to self-report unfavorably)

may influence participants in some questions. Additionally, despite Baron-Cohen and

Wheelwright’s (2004) claim that facets of Empathy (e.g., Affective versus Cognitive) cannot

be parsed, Lawrence et al. (2004) employed a Principal Components Analysis to determine

that the EQ questions could be accurately categorized into three subtypes of Empathy that

measure: Cognitive Empathy, emotional reactivity, and social skills separately. Other

evaluations of EQ (e.g., Muncer & Ling 2006, Berthoz et al. 2008) again confirm that the

measure of these three separate types of Empathy is valid. Furthermore, Allison et al.

(2011) support dividing the test into three categories of Empathy by applying a Rasch

15

analysis, to measure latent personal traits, to evidence the view of EQ as a unidimensional

measure of Empathy. Crucially, through all this, the validity of the EQ remains, and

considering EQ as multi-factor measure of Empathy or a unidimensional measure of

Empathy are valid approaches and applications of EQ.

Additional criticisms of EQ cite that participants with Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD) often underreport their own Empathy compared to control groups (Baron-Cohen &

Wheelwright, 2004; Lawrence et al., 2004; Allison et al. 2011). With EQ questions and ASD

status both relying on self-reporting, the opportunity for variance arises between those with

ASD who report their condition and those who do not (Lawrence et al., 2004). Despite these

criticisms, Lawrence et al. (2004) report that EQ accurately distinguishes between control

groups (i.e., participants without ASD) and clinical groups (i.e., participants with ASD)

because of the robust sample size. This particular shortcoming targets EQ in

clinical/diagnostic settings; however, this does not convey that EQ is a false indicator of a

person’s Empathy. Additionally, if someone is hoping to get a baseline measure of

Psychological Empathy without heeding the ASD implications, this test is described as

“suitable for use as a casual measure of temperamental Empathy by and for the general

population” (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004).

To measure a socio-cognitive construct like Empathy with reliability is no simple

task. Certain tests have proven successful at reliably targeting specific aspects of Empathy

or Empathy related behavior (e.g., HES - offending behavior, EQ - singular Empathy

construct, QMEE - emotional arousal, IRI - perspective taking). As Psychology continues to

improve upon previous versions of Empathy tests, the most prominent tests all seem to

follow a self-reporting style, which appears to be an inherent conflict to the impartiality of

what it attempts to measure. Many of the questions on these exams are quite direct and

transparent toward the goal of assessing social awkwardness or emotional confusion. This

16

creates a motive for someone who may want to “correctly” answer a question to avoid being

labeled at risk for a deficiency of Empathy.

2.2 Linguistic Empathy

The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of Linguistic Empathy, which is

the central principle under investigation in the psycholinguistic experiments in this paper.

As mentioned, Linguistic Empathy and Psychological Empathy derive from different

theoretical constructs, which happen to share the term

Empathy

. However, as will be

demonstrated in this section, many of the theoretical foundations, like perspective-taking

and appropriate responses, overlap between the two concepts. The extent to which these

two distinct concepts overlap is a central research question to be explored.

2.2.1 Empathy perspective. Linguistic Empathy refers to the vantage point from

which an event is encoded in a speaker’s language. Empathy is the perspective with respect

to certain participants (e.g. the agent or the patient of the action in an utterance) or events

in a sentence. In expressing his/her point of view, the speaker identifies with entities in a

speech event to varying degrees. As defined by Kuno (1987):

(2.1) Empathy: Empathy is the speaker’s identification, which may vary in degree,

with a person/thing that participates in the event or state that he describes in a

sentence (Kuno, 1987, p. 206).

(2.2) Degree of Empathy: The degree of the speaker’s Empathy with x, E(x), ranges

from 0 to 1, with E(x) = 1 signifying his total identification with x, and E(x) = 0 a

total lack of identification (Kuno, 1987, p. 206).

One facet of Linguistic Empathy is that it explains certain linguistic data that defy

standard syntactic explanation. It manifests in the speech events produced in the form of a

17

speaker’s momentary and subconscious choice of expression among grammatically or

lexically correct options at his/her disposal. Linguistic Empathy has been used to explain

how the subconscious selection is reached. For example, when a mother asks her five-year-

old son

Did daddy call?

rather than

Did Joey call?

or

Did my husband call?

, the mother is

sharing the perspective of the child, who thinks of his father as

daddy

instead of

Joey

or

(his mother’s) husband.

The mother, however, more likely considers this same person as

Joey

or

my husband

when expressing her own perspective. Besides playing a role in the

choice of referential expressions (

daddy

versus

Joey

), Linguistic Empathy has been

proposed as the force behind other lexical choices (

come

versus

go

), as well as behind the

choice of the grammatical subject of reciprocal verbs and some active/passive options (see

more on this below), reflexive forms (

you

versus

yourself

), and other phenomena observed

in several typologically unrelated languages (Silverstein, 1976; DeLancey, 1981; Kuno,

1987; Yokoyama, 1999; Oshima, 2007a).

Since language speakers are typically heavily reliant on their visual sense, this

vantage point is often conceived of through visual representation, as in

Figure 2.1

below.

This depicts Kuno and Kaburaki’s (1977, p. 628) reference to “camera angles” as a manner

of experiencing language, where the sentences listed in (A), (B), and (C) correspond to the

metaphorical vantage point of (A), (B), and (C). The notion of “camera angle” corresponds to

where a camera would be placed to capture the scene depicted in the utterances. The

utterances are all logically equivalent, and they vary only in grammatical structure and

referential expressions. The utterances in (A) provide a relatively neutral depiction of the

scene, whereas the utterances in (B) and (C) convey

Teddy’s

and

Lucy’s

perspective,

respectively.

Kuno’s initial description of Linguistic Empathy suggests that a sentence can be

conceived of in terms of camera placement as if the scene were filmed. Although this

18

embodies much of how Linguistic Empathy exists in language, this notion oversimplifies

Linguistic Empathy and falls short of representing its crux. The camera placement aligns

nicely with

viewpoint

, in which we literally

see

the scene described in the sentence from the

appropriate angle. However, this does not account for sentences that are

experienced

and

cannot be

viewed

, in literal terms. Like the theory of perspective discussed by Uspensky

(1972), Linguistic Empathy goes beyond the visual experience implied through the use of a

camera angle and instead represents the entire visceral experience of an event. The extent

to which a speech event portrays this experience reflects Linguistic Empathy. For instance,

a sentence like

her stomach turned

is not something for which “camera placement” is

appropriate. This sentence is not about the film-able signals of such an event (e.g., a

wincing facial expression that indicates someone’s stomach might be turning); rather, this

sentence is about the internal experience of one’s stomach turning. The version of this

(A) Teddy hugged Lucy.

Lucy hugged Teddy.

Teddy and Lucy hugged.

(B) Teddy hugged his sister.

(C) Lucy was hugged by her

brother.

Adapted from Kuno & Kaburaki (1977, p. 628).

Figure 2.1: Kuno & Kaburaki’s “Empathy and Camera Angles”

19

sentence that would be film-able (e.g.,

[it seemed that] her stomach turned

) would shift the

perspective from internal to external.

For a classic illustration of a shift in Linguistic Empathy that defies syntactic

explanation, we turn to Kuno and Kaburaki (1977) and some examples with the Japanese

verbs

yaru

and

kureru

, which share the same logical meaning,

to give.

The difference in

these verbs is entirely empathic:

yaru

is used when the speech event is described from the

sentential subject’s (i.e., the giver’s) perspective, and

kureru

is used when the speech event

is described from the sentential dative’s (i.e., the receiver’s) perspective, as seen in the

following two sentences, both of which have the core meaning “Taroo gave the money to

Hanako.”

(2.3) a. Taroo wa Hanako ni okane o

yatta.

(Subject-Centered)

Taroo-NOM Hanako-DAT money-ACC gave

‘Taroo gave the money to Hanako.’

b. Taroo wa Hanako ni okane o

kureta.

(Dative-Centered)

Taroo-NOM Hanako-DAT money-ACC gave

‘Taroo gave the money to Hanako.’

(Adapted from Kuno & Kaburaki 1977, p. 630)

The syntactic structure and case marking of these two examples are identical, and

the logical truth value for each sentence is the same (i.e.,

Taroo

was the giver of money to

Hanako

). However, despite the fact that both (2.3a) and (2.3b) are grammatical and

acceptable, there is not free alternation of these verbs and their corresponding perspectives.

By uttering (2.3a), the speaker conveys the perspective of

Taroo

, thereby unequivocally

signaling an identification with him. It would most naturally be uttered by someone who is

part of

Taroo’s

in-group (e.g.,

Taroo’s

friend or relative). Alternatively, by uttering (2.3b),

the speaker conveys the perspective of

Hanako

, thereby unequivocally signaling an

20

identification with her. It would most naturally be uttered by someone who is part of

Hanako’s

in-group (e.g.,

Hanako’s

friend or relative). For a speaker who is part of an in-

group to utter a sentence that corresponds with the perspective of the other entity would

sound jarring to the hearer and cause confusion as to the speaker’s allegiance. A speaker

who is not part of either in-group or who is part of both in-groups choosing between these

two verbs must therefore indicate whether to view and convey the logical truth of the

utterance from the perspective of the giver (

Taroo

) or from the perspective of the receiver

(

Hanako

) by means of verb choice

1

.

It is possible for the identification with one of the entities in the sentence to be made

lexically explicit when certain referential expressions are used. For instance, uttering the

Japanese first person male pronoun

boku

identifies the speaker unequivocally with the

speaker’s own perspective (i.e., the speaker must identify with himself), whereas uttering

the name

Taroo

does not explicitly identify the speaker’s perspective. Sentences are

unacceptable when the identification with one of the sentential entities is made lexically

explicit, and the perspective conveyed by the verb conflicts with the explicit perspective of

that sentential entity, as in examples (4) and (5) below.

(2.4) a.

Boku

wa Taroo ni okane o

yatta.

(Subject-Centered Verb)

I - ACC Taroo-DAT money-ACC gave

‘I gave money to Taroo.’

1

A truly neutral speaker, e.g. a judge in a court case, would avoid either verb and resort to

a formal Sino-Japanese high register word like

zouyo-suru

‘gift’ or an archaism high

register word like

ataeru

‘give’, neither of which would be usable in normal speech.

21

b. * Taroo wa

boku

ni okane o

yatta.

(Subject-Centered Verb)

Taroo-ACC I-DAT money-ACC gave

‘Taroo gave me money.’

(2.5) a. *

Boku

wa Taroo ni okane o

kureta.

(Dative-Centered Verb)

I - ACC Taroo-DAT money-ACC gave

‘I gave money to Taroo.’

b. Taroo wa

boku

ni okane o

kureta.

(Dative-Centered Verb)

Taroo-ACC I-DAT money-ACC gave

‘Taroo gave me money.’

(Adapted from Kuno & Kaburaki 1977, p. 631)

In all examples above, the perspective is explicit by means of the first person

pronoun

boku

. In other words, when

boku

is uttered, the speaker conveys his/her own

perspective, and the sentence should be experienced from this vantage point. When

boku

is

used as the subject of the sentences in (2.4a) and (2.5a), the subject-centered verb

yaru

in

(2.4a) correctly corresponds with the perspective of the speaker (

boku

), whereas the dative-

centered verb

kureru

in (2.5a) clashes with the perspective that is already established by

boku

. Similarly, when

boku

is used as the indirect object of the sentences in (2.4b) and

(2.5b), the dative-centered verb

kureru

in (2.5b) correctly corresponds with the perspective

of the speaker (

boku ni

), whereas the subject-centered verb

yaru

in (2.4b) clashes with the

perspective that is already established.

Examples (2.4) and (2.5) illustrate that a shift in Empathy perspective to an

unnatural or unexpected Empathy locus can hinder the acceptability of an utterance. Kuno

and Kaburaki, (1977) and Kuno (1987) use violations of Linguistic Empathy like those in

(2.4b) and (2.5a) to inform and establish rules of acceptable perspective taking. Like

Silverstein’s (1976) predictions of the distribution of split-ergative case markings, these

22

rules form Empathy Hierarchies that can predict violations and acceptability of sentences

where syntax fails to do so.

2.2.2 Empathy Hierarchies and their pragmasemantic connections. Kuno (1987)

posits that the Degree of Empathy is managed by a series of rules in the form of Empathy

Hierarchies (EHs) that determine preferences and constraints for the perspectives shared

in utterances. A speaker establishes a vantage point, or Empathy locus, through different

discourse channels (e.g., referential expressions, structure, semantic relations, context) that

manifest within these hierarchies (Kuno & Kaburaki, 1977; Kuno, 1987), three of which are

described below.

(2.6) Surface Structure Empathy Hierarchy: It is easier for the speaker to empathize

with the referent of the subject than with the referents of other noun phrases

(NPs) in the sentence.

E(subject) > E(other NPs), (Kuno, 1987, p. 211)

a.

Observed:

Juli met a strange man at the party.

b.

Violated:

(?) A strange man met Juli at the party.

This Surface Structure EH formalizes the notion that perspective is typically established by

the subject of the sentence. In (2.6a), the sentential subject

Juli

is the Empathy locus.

However, in (2.6b), the Surface Structure EH selects the Empathy perspective of the subject

A strange man

. The sentence becomes awkward once the name

Juli

is uttered since a

proper name like

Juli

is typically more relevant than an indefinite NP like

a strange man

.

In addition to the structural account of establishing Empathy perspective, a speaker

typically express identity with her/himself over others by using the first person pronouns

I

and

me

, which is the notion asserted in the Person EH below.

23

(2.7) Person Empathy Hierarchy (also known as the Speech-Act Empathy Hierarchy):

The speaker cannot empathize with someone else more than with himself.

E(speaker) > E(others), (Kuno, 1987, p. 212)

a.

Observed:

I like Gary.

b.

Violated:

(?) Gary is liked by me.

The Person EH formalizes the notion that a speaker identifies with her/his own point of

view over all others. The logical truth value in (2.7a) and (2.7b) above is identical; however,

when the Empathy locus shifts from the speaker (

I

) to a third person entity (

Gary

), the

acceptability of the sentence suffers. The effect that passive voice exerts on sentences like

(2.7b) will be discussed in section 2.2.5. The Topic EH, below, is the final EH to be discussed

here, and it addresses the role of context in perspective taking.

(2.8) Topic Empathy Hierarchy: Given an event or state that involves A and B such

that A is coreferential with the topic of the present discourse and B is not, it is

easier for the speaker to empathize with A than with B.

E(discourse topic) ≥

2

E(nontopic), (Kuno, 1987, p. 210)

a. Observed:

Did you hear what happened to John? He got into a car accident

with Anna.

b. Violated:

Did you hear what happened to John? (?) Anna got into a car

accident with him.

The Topic EH formalizes the notion that entities that are topically relevant are typically

the focus of Empathy. Examples (2.8a) and (2.8b) again convey the same logical content;

2

It is not clear what motivated Kuno (1987) to use the ≥ instead of the > in this EH. This

paper will continue the use of the ≥ within this EH, but it does not take a strict stance as to

which sign is more appropriate.

24

however, (2.8b) is less acceptable than (2.8a). This is due to the first sentence in each

example, in which the referent

John

is mentioned. The question

Did you hear what

happened to John?

establishes

John

as a relevant topic for the following discourse, and the

Topic EH suggests that Empathy with a discourse topic is more natural than with a non-

topic.

When the Empathy relations across these hierarchies align, then the sentence’s

Empathy perspective is consistent. However, discrepancies in Empathy locus can occur

within one utterance, which can often cause marginality in the acceptability of a sentence.

Kuno postulates a

Ban on Conflicting Empathy Foci

, which posits that “a single sentence

cannot contain logical conflicts in Empathy relations” (1987, p. 207). According to this

hypothesis, the Empathy relations must remain logically consistent across these

hierarchies. Following Kuno’s terms, when the inequalities align, then there is no Empathy

violation. However, when the inequalities conflict, this causes an Empathy violation, which

affects sentence acceptability. It should be mentioned that Uspensky (1972), Yokoyama

(1979, 2000), and Christensen (1994) have all provided counterexamples in Russian and

Polish that refute Kuno’s ban. In these examples, multiple distinct perspectives occur in the

same sentence. Yokoyama and Christensen have argued against the ban on these grounds.

Instead, the Ban on Conflicting Empathy Foci can be considered a guideline. Let us

consider some examples of the sentences that are in violation, and analyze them using

Kuno’s ban.

(2.9)

I met a strange man at the party.

a. Surface Structure EH: E(

I

) > E(

a strange man

)

b. Person EH: E(

I

) > E(

a strange man

)

c. Topic EH: N/A

25

(2.10)

A strange man met me at the party.

a. Surface Structure EH: E(

a strange man

) > E(

me

)

b. Person EH: E(

me

) > E(

a strange man

)

c. Topic EH: N/A

(2.11)

I like Gary.

a. Surface Structure EH: E(

I

) > E(

Gary

)

b. Person EH: E(

I

) > E(

Gary

)

c. Topic EH: N/A

(2.12)

Gary is liked by me.

a. Surface Structure EH: E(

Gary

) > E(

me

)

b. Person EH: E(

me

) > E(

Gary

)

c. Topic EH: N/A

(2.13)

Did you hear what happened to John? He got into a car accident with

Anna.

a. Surface Structure EH: E(

John

) > E(

Anna

)

b. Person EH: N/A

c. Topic EH: E(

John

) > E(

Anna

)

(2.14)

Did you hear what happened to John? Anna got into a car accident with

him.

a. Surface Structure EH: E(

Anna

) > E(

John

)

b. Person EH: N/A

c. Topic EH: E(

John

) > E(

Anna

)

Examples (2.9), (2.11), and (2.13) all explicitly invoke two of the three EHs discussed

above, and the Empathy relationships for these hierarchies do not conflict. Contrarily,

examples (2.10), (2.12), and (2.14) also invoke two of the three EHs, but the Empathy

26

relationships for these hierarchies are in conflict. For instance, examples (2.11) and (2.12)

investigate the sentences

I like Gary

and

Gary is liked by me

, respectively, in terms of the

Person EH and the Surface Structure EH. Since the Surface Structure EH places the

Empathy perspective on the subject of the sentence, and the Person EH places the Empathy

perspective with the speaker (

I/me

) above other NPs,

I

is valid as the Empathy locus by

means of both EHs in example (2.11), but the Empathy perspective is conflicting in example

(2.12). This conflict, according to Kuno, causes marginality in sentences. Since there is no

explicit topic in this example (e.g., no preceding context), the Topic EH was not considered

in the examples above unless there was a context sentence given. Kuno does not make

explicit how a sentential entity becomes a “topic of the present discourse,” in cases when no

preceding context includes a topic, so for now, it is assumed that the sentential entity must

be referenced previously. The role of Topic EH when there is not explicit entity that is

referenced previously will be discussed in section 2.2.4.

Other linguistic hierarchies have been proposed that are closely related to Kuno’s

EHs. Silverstein (1976, 1981) and Deane (1992) propose hierarchies that largely overlap

with Kuno’s and describe closely related phenomena. The Silverstein Hierarchy was

originally proposed to explain variability in split-ergative languages. Ergativity allows

perspectives and identities to be assigned without specific lexical items or structural

changes. Ergative-absolutive languages assign the same case marking to the subject of an

intransitive verb as the object of a transitive verb, whereas nominative-accusative

languages, such as English, assign the same case marking to subjects of transitive and

intransitive verbs. Split-ergative languages contain sentences that can vary between

sentences with ergative-absolutive case markings and sentences with nominative-

accusative case markings. Silverstein establishes a hierarchy based on animacy (e.g.,

human > nonhuman

, and

1

st

person > 2

nd

person > 3

rd

person

, etc.) that predicts which

27

sentential NPs prefer a given case based on the lexical properties of this NP — that the

“‘split’ of case markings is not random” (Silverstein, 1976, p. 113). In other words, NPs that

are higher on the Silverstein Hierarchy more naturally take nominative-accusative case

markings, and the NPs that are lower on the hierarchy take ergative-absolutive case

markings. This parallels the hierarchies that Kuno proposed for Linguistic Empathy in

terms of the ease with which a speaker can identify/empathize with an entity in a speech

event. Kuno argues that in order to share an entity’s perspective, that entity must be

capable of having a perspective in the first place. That excludes inanimate entities and non-

human animate entities, which must be personified in order for the speaker to assume their

perspective. Importantly, Silverstein focuses on the lexical properties of the varying NPs

when establishing order to the assignment of case markings. DeLancey (1981)

acknowledges the Silverstein Hierarchy and builds upon the lexical properties of NPs to

include the use of aspect in determining viewpoint in split-ergative languages. Verb aspect

(e.g., perfect vs. imperfect) in these languages can shift viewpoint from internal to external

without a change in case markings or lexical items. Other languages, such as English, must

default to changes in structure, like passivization, in order to accomplish a similar effect.

Deane (1992) applies the notions of animacy, agency, and salience to the NPs of an

utterance in order to extend the Silverstein Hierarchy. Deane argues that the extent to

which a sentential entity embodies these qualities correlates with how naturally a

speaker/hearer should share its perspective. Animacy, agency, and salience unify Deane’s

hierarchy of entrenchment with Kuno’s EHs, and these qualities can map onto Kuno’s EHs.

The first factor of these factors, animacy, is the conceptual relation that an entity has in

common with the speaker. That is, the more in common an entity has physiologically with

the speaker, the more natural it is to empathize with this entity. As mentioned above, the

notion of animacy is central to the Silverstein Hierarchy (Silverstein, 1976). Animacy

28

hierarchies rank humans over non-humans, which is typically further delineated in the

following order:

Humans > Animals > Plants > Natural Forces > Concrete Objects >

Abstract Objects

. The

Humans

portion of this hierarchy most broadly unravels into the

following order:

First Person > Second Person > Third Person

(Yamamoto, 1999). Animacy

and humanness map directly onto Kuno’s Person EH and provide the means to investigate

greater granularity to the concepts of

speaker

and

other

. A crucial difference between

Deane’s entrenchment hierarchy and Kuno’s Person EH is that the granularity introduced

in the Deane’s hierarchy is based on tendencies of Empathy relations, but not strict rules;

violating these tendencies does not necessarily result in an invalid utterance. However, the

Person EH is based on the binary notion of

speaker

versus

others

, and it claims that

utterances that violate this preference, i.e.,

others

over

speaker

, are infelicitous.

The agency of a NP is another factor that diminishes sequentially along Deane’s

entrenchment hierarchy and the Silverstein Hierarchy. With humans at the top, and non-

humans toward the bottom, the relevance for establishing agency also diminishes as one

moves down the hierarchy. In other words, semantically speaking, humans should be more

capable of serving as agents in narrated events, which is a notion that aligns with the

animacy hierarchies. Hopper & Thompson (1980) consider agency interrelated with the