Enhancing Motivation for Change in

Substance Use Disorder Treatment

TI

TREATMENT I

P

MPROVEMENT

35

PROTOCOL

UPDATED 2019

This page intentionally left blank

This page intentionally left blank

TIP 35

Contents

Foreword ................................................................. viii

Executive Summary .......................................................... ix

TIP Development Participants ..................................................xv

Publication Information...................................................... xxi

Chapter 1—A New Look at Motivation .......................................1

Motivation and Behavior Change ..............................................4

Changing Perspectives on Addiction and Treatment...............................6

TTM of the SOC ...........................................................13

Conclusion................................................................16

Chapter 2—Motivational Counseling and Brief Intervention...................17

Elements of Eective Motivational Counseling Approaches........................17

Motivational Counseling and theSOC .........................................23

Special Applications of Motivational Interventions ...............................26

Brief Motivational Interventions ..............................................30

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment ..........................32

Conclusion................................................................33

Chapter 3—Motivational Interviewing as a Counseling Style ..................35

Introduction to MI .........................................................35

What Is New in MI .........................................................37

Ambivalence ..............................................................38

Core Skills of MI: OARS......................................................41

Four Processes of MI........................................................48

Benets of MI in Treating SUDs...............................................63

Conclusion............................................................... 64

Chapter 4—From Precontemplation to Contemplation: Building Readiness .....65

Develop Rapport and Build Trust .............................................66

Raise Doubts and Concerns About the Client’s Substance Use......................71

Treatment ..............................................................77

Conclusion................................................................81

Understand Special Motivational Counseling Considerations for Clients Mandated to

Chapter 5—From Contemplation to Preparation: Increasing Commitment......83

Normalize and ResolveAmbivalence ......................................... 84

Help Tip the Decisional Balance Toward Change ................................87

Conclusion................................................................93

v

TIP 35

Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Chapter 6—From Preparation to Action: Initiating Change ....................95

Explore Client Change Goals .................................................96

Develop a Change Plan .....................................................99

Support the Client’s Action Steps ............................................107

Evaluate the Change Plan ..................................................108

Conclusion...............................................................108

Chapter 7—From Action to Maintenance: Stabilizing Change.................109

Stabilize Client Change.....................................................110

Support the Client’s Lifestyle Changes ........................................117

Help the Client Reenter the Change Cycle .....................................120

Conclusion...............................................................124

Chapter 8—Integrating Motivational Approaches in SUD Treatment Settings .125

Adaptations of Motivational Counseling Approaches ............................126

Workforce Development ...................................................131

Conclusion...............................................................135

Appendix A—Bibliography....................................................137

Appendix B—Screening and Assessment Instruments..............................149

1. U.S. Alcohol Use Disorders Identication Test (AUDIT) .........................150

2. Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) ......................................152

3. Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) (Lifetime) .........................154

4. What I Want From Treatment (2.0). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .157

5. Readiness to Change Questionnaire (Treatment Version) (RCQ-TV) (Revised) ......160

6. Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale–Alcohol

(SOCRATES 8A) .........................................................162

7. Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale–Drug (SOCRATES 8D) .164

8. University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) Scale...................168

9. Alcohol and Drug Consequences Questionnaire (ADCQ) .......................171

10. Alcohol Decisional Balance Scale .........................................173

11. Drug Use Decisional Balance Scale ........................................175

12. Brief Situational Condence Questionnaire (BSCQ)...........................177

13. Alcohol Abstinence Self-Ecacy Scale (AASES) ..............................179

14. Motivational Interviewing Knowledge Test .................................181

Appendix C—Resources ......................................................186

Motivational Interviewing and Motivational Enhancement Therapy................186

Stages of Change .........................................................186

Training and Supervision ...................................................186

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration .....................187

vi

TIP 35

Exhibits

Exhibit 1.1. Models of Addiction .................................................7

Exhibit 1.2. Examples of Natural Changes ........................................13

Exhibit 1.3. The Five Stages in the SOC in the TTM .................................14

Exhibit 2.1. The Drinker’s Pyramid Feedback ......................................19

Exhibit 2.2. Catalysts for Change ...............................................24

Exhibit 2.3. Counselor Focus in the SOC ..........................................25

Exhibit 2.4. RESPECT: A Mnemonic for Cultural Responsiveness ......................27

Exhibit 3.1. A Comparison of Original and Updated Versions of MI....................37

Exhibit 3.2. Misconceptions and Clarications About MI ............................38

Exhibit 3.3. Examples of Change Talk and Sustain Talk..............................40

Exhibit 3.4. Closed and Open Questions .........................................41

Exhibit 3.5. Gordon’s 12 Roadblocks to Active Listening ........................... 44

Exhibit 3.6. Types of Reective Listening Responses ................................46

Exhibit 3.7. Components in a Sample Agenda Map ................................51

Exhibit 3.8. Examples of Open Questions to Evoke Change Talk Using DARN ...........53

Exhibit 3.9. The Importance Ruler ..............................................54

Exhibit 3.10. The Condence Ruler ..............................................60

Exhibit 4.1. Counseling Strategies for Precontemplation.............................66

Exhibit 4.2. Styles of Expression in the Precontemplation Stage: The5Rs ..............69

Exhibit 4.3. An Opening Dialog With a Client Who Has Been Mandated to Treatment....79

Exhibit 5.1. Counseling Strategies for Contemplation .............................. 84

Exhibit 5.2. The Motivational Interviewing (MI) Hill of Ambivalence ..................85

Exhibit 5.3. Decisional Balance Sheet for Substance Use ............................88

Exhibit 5.4. Other Issues in Decisional Balance ....................................89

Exhibit 5.5. Recapitulation Summary ............................................92

Exhibit 6.1. Counseling Strategies for Preparation and Action ........................96

Exhibit 6.2. When Treatment Goals Dier ........................................98

Exhibit 6.3. Change Plan Worksheet............................................101

Exhibit 6.4. Mapping a Path for Change When There Are Multiple Options ...........104

Exhibit 7.1. Counseling Strategies for Action and Relapse...........................110

Exhibit 7.2. Options for Responding to a Missed Appointment ......................114

Exhibit 7.3. Triggers and Coping Strategies ......................................116

Exhibit 7.4. A Menu of Coping Strategies........................................117

Exhibit 7.5. Susan’s Story: A Client Lacking Social Support ..........................119

Exhibit 7.6. Marlatt’s RPC Process ..............................................121

Exhibit 8.1. Blending the Spirit of MI With CBT ...................................130

vii

TIP 35 Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Foreword

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services agency that leads public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance

abuse and mental illness on America’s communities. An important component of SAMHSA’s work is

focused on dissemination of evidence-based practices and providing training and technical assistance to

healthcare practitioners on implementation of these best practices.

The Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series contributes to SAMHSA’s mission by providing science-

based, best-practice guidance to the behavioral health field. TIPs reflect careful consideration of all

relevant clinical and health service research, demonstrated experience, and implementation requirements.

Select nonfederal clinical researchers, service providers, program administrators, and patient advocates

comprising each TIP’s consensus panel discuss these factors, offering input on the TIP’s specific topics in

their areas of expertise to reach consensus on best practices. Field reviewers then assess draft content and

the TIP is finalized.

The talent, dedication, and hard work that TIP panelists and reviewers bring to this highly participatory

process have helped bridge the gap between the promise of research and the needs of practicing

clinicians and administrators to serve, in the most scientifically sound and effective ways, people in need of

care and treatment of mental and substance use disorders. My sincere thanks to all who have contributed

their time and expertise to the development of this TIP. It is my hope that clinicians will find it useful and

informative to their work.

Elinore F. McCance-Katz, M.D., Ph.D.

Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

viii

TIP 35

Executive Summary

Motivation for change is a key component in addressing substance misuse. This Treatment Improvement

Protocol (TIP) reflects a fundamental rethinking of the concept of motivation as a dynamic process, not a

static client trait. Motivation relates to the probability that a person will enter into, continue, and adhere to

a specific change strategy.

Although much progress has been made in identifying people who misuse substances and who have

substance use disorders (SUDs) as well as in using science-informed interventions such as motivational

counseling approaches to treat them, the United States still faces many SUD challenges. For example, the

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,

2018) reports that, in 2017, approximately:

•

140.6 million Americans ages 12 and older currently consumed alcohol, 66.6 million reported

at least 1 episode of past-month binge drinking (defined as 5 or more drinks on the same

occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days for men and 4 or more drinks on the same

occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days for women), and 16.7 million drank heavily in

the previous month (defined as binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past 30 days).

•

30.5 million people ages 12 and older had used illicit drugs in the past month.

•

11.4 million people ages 12 and older misused opioids (defined as prescription pain reliever

misuse or heroin use) in the past year.

•

8.5 million adults ages 18 and older (3.4 percent of all adults) had both a mental disorder and

at least 1 past-year SUD.

•

18.2 million people who needed SUD treatment did not receive specialty treatment.

•

One in three people who perceived a need for substance use treatment did not receive it

because they lacked healthcare coverage and could not afford treatment.

•

Two in five people who perceived a need for addiction treatment did not receive it because

they were not ready to stop using substances.

Millions of people in the United States with SUDs are not receiving treatment. Many are not seeking

treatment because their motivation to change their substance use behaviors is low.

The motivation-enhancing approaches and strategies

this TIP describes can increase participation and

retention in SUD treatment and positive treatment

outcomes, including:

•

Reductions in alcohol and drug use.

•

Higher abstinence rates.

•

Successful referrals to treatment.

This TIP shows how SUD treatment counselors can influence positive behavior change by developing

a therapeutic relationship that respects and builds on the client’s autonomy. Through motivational

enhancement, counselors become partners in the client’s change process.

The TIP also describes different motivational interventions counselors can apply to all the stages in the

Stages of Change (SOC) model related to substance misuse and recovery from addiction.

A consensus panel developed this TIP’s content based on a review of the literature and on panel members’

extensive experience in the field of addiction treatment. Other professionals also generously contributed

their time and commitment to this project.

ix

TIP 35

Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Intended Audience

The primary audiences for this TIP are:

•

Drug and alcohol treatment service providers.

•

Mental health service providers, such as

psychologists, licensed clinical social workers,

and psychiatric/mental health nurses.

•

Peer recovery support specialists.

•

Behavioral health program managers, directors,

and administrators.

•

Clinical supervisors.

•

Healthcare providers, such as primary care

physicians, nurse practitioners, general/family

medicine practitioners, registered nurses,

internal medicine specialists, and others who

may need to enhance motivation to address

substance misuse in their patients.

Secondary audiences include prevention

specialists, educators, and policymakers for SUD

treatment and related services.

Overall Key Messages

Motivation is key to substance use behavior

change. Counselors can support clients’ movement

toward positive changes in their substance use

by identifying and enhancing motivation that

alreadyexists.

Motivational approaches are based on the

principles of person-centered counseling.

Counselors’ use of empathy, not authority and

power, is key to enhancing clients’ motivation to

change. Clients are experts in their own recovery

from SUDs. Counselors should engage them in

collaborative partnerships.

Ambivalence about change is normal.

Resistance to change is an expression of

ambivalence about change, not a client trait

or characteristic. Confrontational approaches

increase client resistance and discord in the

counseling relationship. Motivational approaches

explore ambivalence in a nonjudgmental and

compassionate way.

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of the SOC

approach is an overarching framework that helps

counselors tailor specific counseling strategies

to different stages. Motivational counseling

strategies should be tailored to clients’ level of

motivation to change their substance use behaviors

at each of the five stages of the SOC:

•

Precontemplation

•

Contemplation

•

Preparation

•

Action

•

Maintenance

Effective motivational counseling approaches

can be brief. A growing body of evidence

indicates that early and brief interventions

demonstrate positive treatment outcomes in a

wide variety of settings including specialty SUD

treatment programs, primary care offices, and

emergency departments. Brief interventions

emphasize reducing the health-related risk

of a person’s substance use and decreasing

consumption as an important treatment outcome.

Motivational interviewing (MI) and other

motivational counseling approaches like

motivational enhancement therapy are effective

ways to enhance motivation throughout the

SOC. Motivational counseling approaches are

based on person-centered counseling principles

that focus on helping clients resolve ambivalence

about changing their substance use and other

health-risk behaviors.

MI is the most widely researched and

disseminated motivational counseling

approach in SUD treatment. The spirit of MI

(i.e., partnership, acceptance, compassion,

and evocation) is the foundation of the core

counseling skills required for enhancing clients’

motivation to change. The core counseling skills

of MI are described in the acronym OARS (Open

questions, Affirmations, Reflective listening,

andSummarization).

Counselor empathy, as expressed through

reflective listening, is fundamental to MI. Use

of empathy, rather than power and authoritative

approaches, is critical for helping clients achieve

and maintain lasting behavior change.

x

TIP 35

Adaptations of MI enhance the implementation

and integration of motivational interventions

into standard treatment methods. Training,

ongoing supervision, and coaching of counselors

are essential for workforce development and

integration of motivational counseling approaches

into SUD treatment.

Content Overview

Chapter 1—A New Look at Motivation

This chapter lays the groundwork for

understanding treatment concepts discussed

later in the TIP. It is an overview of the nature of

motivation and its link to changing substance

use behaviors. The chapter describes changing

perspectives on addiction and addiction treatment

in the United States and uses the TTM of the

SOC approach as an overarching framework to

understand how people change their substance

use behaviors.

In Chapter 1, readers will learn that:

•

Motivation is essential to substance use

behavior change. It is multidimensional,

dynamic, and fluctuating; can be enhanced; and

is influenced by the counselor’s style.

•

Benefits of using motivational counseling

approaches include clients’ enhancing

motivation to change, preparing them to enter

treatment, engaging and retaining clients in

treatment, increasing their participation and

involvement in treatment, improving their

treatment outcomes, and encouraging a rapid

return to treatment if they start misusing

substances again.

•

New perspectives on addiction treatment

include focusing on clients’ strengths

instead of deficits, offering person-centered

treatment, shifting away from labeling clients,

using empathy, focusing on early and brief

interventions, recognizing that there is a range

of severity of substance misuse, accepting risk

reduction as a legitimate treatment goal, and

providing access to integrated care.

•

People go through stages in the SOC approach;

this concept is known as the TTM of change.

•

The stages in the SOC model are:

-

Precontemplation, in which people are not

considering change.

-

Contemplation, in which people are

considering change but are unsure how

tochange.

-

Preparation, in which people have identified

a change goal and are forming a plan

tochange.

-

Action, in which people are taking steps

tochange.

-

Maintenance, in which people have met

their change goal and the behavior change

isstable.

Chapter 2—Motivational Counseling and

Brief Intervention

This chapter is an overview of motivational

counseling approaches, including screening, brief

intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT).

It describes elements of effective motivational

counseling approaches, including FRAMES

(Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu of

options, Empathy, and Self-efficacy), decisional

balancing, discrepancy development, flexible

pacing, and maintenance of contact with clients.

The chapter describes counselors’ focus in each

stage of the SOC model. It addresses special

applications of motivational counseling with

clients from diverse cultures and with clients who

have co-occurring substance use and mental

disorders (CODs).

In Chapter 2, readers will learn that:

•

Each stage in the SOC approach has

predominant experiential and behavioral

catalysts for client change on which counselors

should focus.

•

Counselors should adopt the principles of

cultural responsiveness and adapt motivational

interventions to those principles when treating

clients from diverse backgrounds.

•

Even mild substance misuse can impede

functioning in people with CODs, including

co-occurring severe mental illness. Counselors

can adapt motivational interventions for

these clients.

xi

TIP 35

Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

•

Brief motivational interventions, including SBIRT,

are effective in specialty SUD treatment facilities

and opportunistic settings (e.g., primary care

offices, emergency departments).

•

Brief interventions emphasize risk reduction

and referral to specialty addiction treatment

ifneeded.

Chapter 3—Motivational Interviewing as

a Counseling Style

This chapter provides an overview of the spirit of

MI, the principles of person-centered counseling,

the core counseling skills of MI (i.e. asking open

questions, affirming, reflective listening, and

summarizing), and the four processes of MI (i.e.,

engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning). It

describes what’s new in MI and dispels many

misconceptions about MI. The chapter discusses

the components that counselors use to help clients

resolve ambivalence and move toward positive

substance use behavior change.

In Chapter 3, readers will learn that:

•

Ambivalence about substance use and change is

normal and a motivational barrier to substance

use behavior change, if not explored.

•

The spirit of MI embodies the principles of

person-centered counseling and is the basis of

an empathetic, supportive counseling style.

•

Sustain talk is essentially statements the client

makes for not changing (i.e., maintaining the

status quo), and change talk is statements

the client makes in favor of change. The key

to helping the client move in the direction

toward changing substance use behaviors

is to evoke change talk and soften or lessen

the impact of sustain talk on the client’s

decision-makingprocess.

•

The acronym OARS describes the core skills

ofMI:

-

Asking Open questions

-

Affirming the client’s strengths

-

Using Reflective listening

-

Summarizing client statements

•

Reflective listening is fundamental to person-

centered counseling in general and MI in

particular and is essential for expressing

empathy.

•

The four processes in MI (i.e., engaging,

focusing, evoking, and planning) provide an

overarching framework for employing the core

skills in conversations with a client.

•

The benefits of MI include its broad applicability

to diverse medical and behavioral health

problems and its capacity to complement

other counseling approaches and to mobilize

clientresources.

Chapter 4—From Precontemplation to

Contemplation: Building Readiness

This chapter discusses strategies counselors

can use to help clients raise doubt and concern

about their substance use and move toward

contemplating the possibility of change. It

emphasizes the importance of assessing clients’

readiness to change, providing personalized

feedback to them about the effects and risks

of substance misuse, involving their significant

others in counseling to raise concern about

clients’ substance use behaviors, and addressing

special considerations for treating clients who are

mandated to treatment.

In Chapter 4, readers will learn that:

•

A client in the Precontemplation stage is

unconcerned about substance use or is not

considering change.

•

The counselor’s focus in Precontemplation is

to establish a strong counseling alliance and

raise the client’s doubts and concerns about

substance use.

•

Key strategies in this stage include eliciting the

client’s perception of the problem, exploring

the events that led to entering treatment, and

identifying the client’s style of Precontemplation.

•

Providing personalized feedback on assessment

results and involving significant others in

counseling sessions are key strategies for

raising concern and moving the client toward

contemplating change.

•

Special considerations in motivational

counseling approaches for clients mandated

to treatment include acknowledging client

ambivalence and emphasizing personal choice

and responsibility.

xii

TIP 35

Chapter 5—From Contemplation to

Preparation: Increasing Commitment

This chapter describes strategies to increase

clients’ commitment to change by normalizing

and resolving ambivalence and enhancing their

decision-making capabilities. It emphasizes

decisional balancing and exploring clients’ self-

efficacy as important to moving clients toward

preparing to change substance use behaviors.

Summarizing change talk and exploring the

client’s understanding of change prepare clients to

take action.

In Chapter 5, readers will learn that:

•

In the Contemplation stage, the client

acknowledges concerns about substance use

and is considering the possibility of change.

•

The counselor’s focus in Contemplation is to

normalize and resolve client ambivalence and

help the client tip the decisional balance toward

changing substance use behaviors.

•

Key motivational counseling strategies for

resolving ambivalence include reassuring the

client that ambivalence about change is normal;

evoking DARN (Desire, Ability, Reasons, and

Need) change talk; and summarizing the

client’sconcerns.

•

To reinforce movement toward change, the

counselor reinforces the client’s understanding

of the change process, reintroduces

personalized feedback, explores client self-

efficacy, and summarizes client change talk.

•

The counselor encourages the client to

strengthen his or her commitment to change by

taking small steps, going public, and envisioning

life after changing substance use behaviors.

Chapter 6—From Preparation to Action:

Initiating Change

This chapter describes the process of helping

clients identify and clarify change goals. It also

focuses on how and when to develop change

plans with clients and suggests ways to ensure that

plans are accessible, acceptable, and appropriate

for clients.

In Chapter 6, readers will learn that:

•

In the Preparation stage, the client is committed

and planning to make a change but is unsure of

what to do next. In the Action stage, the client

is actively taking steps to change but has not

reached stable recovery.

•

In Preparation, the counselor focuses on helping

the client explore change goals and develop a

change plan. In Action, the counselor focuses on

supporting client action steps and helping the

client evaluate what is working and not working

in the change plan.

•

The client who is committed to change and who

believes change is possible is prepared for the

Action stage.

•

Sobriety sampling, tapering down, and trial

moderation are goal-sampling strategies

that may be helpful to the client who is not

committed to abstinence as a change goal.

•

Creating a change plan is an interactive process

between the counselor and client. The client

should determine and drive change goals.

•

Identifying and helping the client reduce

barriers to the Action stage are important to the

change-planning process.

•

Counselors can support client action by

reinforcing client commitment and continuing

to evoke and reflect CAT (i.e., Commitment,

Activation, and Taking steps) change talk in

ongoing conversations.

Chapter 7—From Action to Maintenance:

Stabilizing Change

This chapter addresses ways in which motivational

strategies can be used effectively to help clients

maintain the gains they have made by stabilizing

change, supporting lifestyle changes, managing

setbacks during the Maintenance stage, and

helping them reenter the cycle of change if

they relapse or return to substance misuse. It

emphasizes creating a coping plan to reduce the

risk of recurrence in high-risk situations, identifying

new behaviors that reinforce change, and

establishing relapse prevention strategies.

In Chapter 7, readers will learn that:

•

During the Maintenance stage, the client has

achieved the initial change goals and is working

toward maintaining those changes.

xiii

TIP 35

Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

•

In Maintenance, the counselor focuses on

helping the client stabilize change and supports

the client’s lifestyle changes.

•

During a relapse, the client returns to

substance misuse and temporarily exits

the change cycle. The counselor focuses

on helping the client reenter the cycle of

change and providing relapse prevention

counseling in accordance with the principles of

person-centeredcounseling.

•

Maintenance of substance use behavior change

in the SOC model must address the issue of

relapse. Relapse should be reconceptualized

as a return to or recurrence of substance use

behaviors and viewed as a common occurrence.

•

Relapse prevention counseling is a cognitive–

behavioral therapy (CBT) method, but the

counselor can use motivational counseling

strategies to engage the client in the process

and help the client resolve ambivalence about

learning and practicing new coping skills.

•

Strategies to help a client reenter the change

cycle after a recurrence include affirming

the client’s willingness to reconsider positive

change, exploring reoccurrence as a learning

opportunity, helping the client find alternative

coping strategies, and maintaining supportive

contact with the client.

Chapter 8—Integrating Motivational

Approaches in SUD Treatment Settings

This chapter discusses some of the adaptations

of motivational counseling approaches applicable

to SUD treatment programs and workforce

development issues that treatment programs

should address to fully integrate and sustain

motivational counseling approaches. It emphasizes

blending MI with other counseling approaches.

It also explores ways in which ongoing training,

supervision, and coaching are essential to

successful workforce development and integration.

In Chapter 8, readers will learn that:

•

Integrating motivational counseling approaches

into a treatment program requires a broad

integration of the philosophy and underlying

spirit of MI throughout the organization.

•

Adapted motivational interventions may be

more cost effective, accessible to clients,

and easily integrated into existing treatment

approaches than expected and may ease some

workload demands on counselors.

•

Technology adaptations, including motivational

counseling and brief interventions over the

phone or via text messaging, are effective,

cost effective, and adaptable to different

clientpopulations.

•

MI is effective when blended with

other counseling approaches including

group counseling, the motivational

interviewing assessment, CBT, and recovery

managementcheckups.

•

The key to workforce development is to train

all clinical and support staffs in the spirit of

MI so that the entire program’s philosophy is

aligned with person-centered principles, like

emphasizing client autonomy and choice.

•

Program administrators should assess the

organization’s philosophy and where it is

in the SOC model before implementing a

trainingprogram.

•

Training counseling staff in MI takes more than

a 1- or 2-day workshop. Maintenance of skills

requires ongoing training and supervision.

•

Supervision and coaching in MI should be

competency based. These activities require

directly observing the counselor’s skill level and

using coding instruments to assess counselor

fidelity. Supervision should be performed in the

spirit of MI.

•

Administrators need to balance training,

supervision, and strategies to enhance

counselor fidelity to MI with costs, while

partnering with counseling staff to integrate a

motivational counseling approach throughout

theorganization.

xiv

TIP 35

TIP Development Participants

Consensus Panel

Each Treatment Improvement Protocol’s (TIP)

consensus panel is a group of primarily nonfederal

addiction-focused clinical, research, administrative,

and recovery support experts with deep

knowledge of the TIP’s topic. With the Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s

Knowledge Application Program team, members

of the consensus panel develop each TIP via a

consensus-driven, collaborative process that blends

evidence-based, best, and promising practices

with the panel members’ expertise and combined

wealth of experience.

Chair

William R. Miller, Ph.D.

Regents Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry

Director of Research

Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and

Addictions

Department of Psychology

University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Workgroup Leaders

Edward Bernstein, M.D., F.A.C.E.P.

Associate Professor and Academic Affairs

Vice Chairman

Boston University School of Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Suzanne M. Colby, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human

Behavior

Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies

Brown University

Providence, Rhode Island

Carlo C. DiClemente, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Baltimore, Maryland

Robert J. Meyers, M.A.

Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and

Addictions

University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Maxine L. Stitzer, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Biology

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Allen Zweben, D.S.W.

Director and Associate Professor of Social Work

Center for Addiction and Behavioral Health

Research

University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Panelists

Ray Daw

Executive Director

Northwest New Mexico Fighting Back, Inc.

Gallup, New Mexico

Jeffrey M. Georgi, M.Div., C.S.A.C., C.G.P.

Program Coordinator

Duke Alcoholism and Addictions Program

Clinical Associate

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina

Cheryl Grills, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

Loyola Marymount University

Los Angeles, California

xv

TIP 35 Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Rosalyn Harris-Offutt, C.R.N.A., L.P.C., A.D.S.

UNA Psychological Associates

Greensboro, North Carolina

Don M. Hashimoto, Psy.D.

Clinical Director

Ohana Counseling Services, Inc.

Hilo, Hawaii

Dwight McCall, Ph.D.

Evaluation Manager

Substance Abuse Services

Virginia Department of Mental Health, Mental

Retardation and Substance Abuse Services

Richmond, Virginia

Jeanne Obert, M.F.C.C., M.S.M.

Director of Clinical Services

Matrix Center

Los Angeles, California

Carole Janis Otero, M.A., L.P.C.C.

Director

Albuquerque Metropolitan Central Intake

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Roger A. Roffman, D.S.W.

Innovative Programs Research Group

School of Social Work

Seattle, Washington

Linda C. Sobell, Ph.D.

Professor

NOVA Southeastern University

Fort Lauderdale, Florida

The information given indicates participants’ affiliations

at the time of their participation in this TIP’s original

development and may no longer reflect their current

affiliations.

Field Reviewers, Resource Panel, and

Editorial Advisory Board

Field reviewers represent each TIP’s intended

target audiences. They work in addiction, mental

health, primary care, and adjacent fields. Their

direct front-line experience related to the TIP’s

topic allows them to provide valuable input on a

TIP’s relevance, utility, accuracy, and accessibility.

Additional advisors to this TIP include members of

a resource panel and an editorial advisory board.

Field Reviewers

Noel Brankenhoff, L.M.F.T., L.C.D.P.

Child and Family Services

Middletown, Rhode Island

Rodolfo Briseno, L.C.D.C.

Coordinator for Cultural/Special Populations and

Youth Treatment Program Services

Program Initiatives Texas Commission on Alcohol

and Drug Abuse

Austin, Texas

Richard L. Brown, M.D., M.P.H.

Associate Professor

Department of Family Medicine

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine

Madison, Wisconsin

Michael Burke

Senior Substance Abuse Specialist

Student Health

Rutgers University

New Brunswick, New Jersey

Kate Carey, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Psychology

Syracuse University

Syracuse, New York

Anthony J. Cellucci, Ph.D.

Director of Idaho State University Clinic

Associate Professor of Psychology

Idaho State University

Pocatello, Idaho

xvi

TIP 35

Gerard Connors, Ph.D.

Research Institute on Alcoholism

Buffalo, New York

John Cunningham, Ph.D.

Scientist

Addiction Research Foundation Division

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Toronto, Ontario

Janie Dargan, M.S.W.

Senior Policy Analyst

Office of National Drug Control Policy/Executive

Office of the President

Washington, D.C.

George De Leon, Ph.D.

Center for Therapeutic Community Research

New York, New York

Nereida Diaz-Rodriguez, L.L.M., J.D.

Project Director

Director to the Master in Health Science in

Substance Abuse

Centro de Entudion on Adiccion (Altos Salud

Mental)

Edif. Hosp. Regional de Bayamon

Santa Juanita, Bayamon, Puerto Rico

Thomas Diklich

Portsmouth CSR

Portsmouth, Virginia

Chris Dunn, Ph.D., M.A.C., C.D.C.

Psychologist

Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

University of Washington

Seattle, Washington

Madeline Dupree, L.P.C.

Harrisonburg-Rockingham CSB

Harrisonburg, Virginia

Gary L. Fisher, Ph.D.

Nevada Addiction Technology Transfer Center

College of Education

University of Nevada at Reno

Reno, Nevada

Cynthia Flackus, M.S.W., L.I.C.S.W.

Therapist

Camp Share Renewal Center

Walker, Minnesota

Stephen T. Higgins, Ph.D.

Professor

Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology

University of Vermont

Burlington, Vermont

Col. Kenneth J. Hoffman, M.D., M.P.H., M.C.F.S.

Preventive Medicine Consultant

HHC 18th Medical Command

Seoul, South Korea

James Robert Holden, M.A.

Program Director

Partners in Drug Abuse Rehabilitation Counseling

Washington, D.C.

Ron Jackson, M.S.W.

Executive Director

Evergreen Treatment Services

Seattle, Washington

Linda Kaplan

Executive Director

National Association of Alcoholism and Drug

Abuse Counselors

Arlington, Virginia

Matthew Kelly, Ph.D.

Clinical Director

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Northwest Mexico Fighting Back, Inc.

Gallup, New Mexico

Karen Kelly-Woodall, M.S., M.A.C., N.C.A.C. II

Criminal Justice Coordinator

Cork Institute

Morehouse School of Medicine

Atlanta, Georgia

Richard Laban, Ph.D.

Laban’s Training

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

xvii

TIP 35 Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Lauren Lawendowski, Ph.D.

Acting Project Director

Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and

Addiction

University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Bruce R. Lorenz, N.C.A.C. II

Director

Thresholds, Inc.

Dover, Delaware

Russell P. MacPherson, Ph.D., C.A.P., C.A.P.P.,

C.C.P., D.A.C., D.V.C.

President

RPM Addiction Prevention Training

Deland, Florida

George Medzerian, Ph.D.

Pensacola, Florida

Lisa A. Melchior, Ph.D.

Vice President

The Measurement Group

Culver City, California

Paul Nagy, M.S., C.S.A.C.

Director

Duke Alcoholism and Addictions Program

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina

Tracy A. O’Leary, Ph.D.

Clinical Supervisor

Assistant Project Coordinator

Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies

Brown University

Providence, Rhode Island

Gwen M. Olitsky, M.S.

CEO

The Self-Help Institute for Training and Therapy

Lansdale, Pennsylvania

Michele A. Packard, Ph.D.

Executive Director

SAGE Institute Training and Consulting

Boulder, Colorado

Michael Pantalon, Ph.D.

Yale School of Medicine

New Haven, Connecticut

Joe Pereira, L.I.C.S.W., C.A.S.

Recovery Strategies

Medford, Massachusetts

Harold Perl, Ph.D.

Public Health Analyst

Division of Clinical and Prevention Research

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Bethesda, Maryland

Raul G. Rodriguez, M.D.

Medical Director

La Hacienda Treatment Center

Hunt, Texas

Richard T. Suchinsky, M.D.

Associate Director for Addictive Disorders and

Psychiatric Rehabilitation

Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences Services

Department of Veterans Affairs

Washington, D.C.

Suzan Swanton, M.S.W.

Clinical Director

R.E.A.C.H. Mobile Home Services

Baltimore, Maryland

Michael J. Taleff, Ph.D., C.A.C., M.A.C.,

N.C.A.C.II

Assistant Professor and Coordinator

Graduate Programs in Chemical Dependency

Department of Counselor Education

Counseling Psychology and Rehabilitation Services

Pennsylvania State University

University Park, Pennsylvania

Nola C. Veazie, Ph.D., L.P.C., C.A.D.A.C.

Superintendent

Medical Services Department

United States Air Force

Family Therapist/Drug and Alcohol Counselor

Veazie Family Therapy

Santa Maria, California

xviii

TIP 35

Mary Velasquez, Ph.D.

Psychology Department

University of Houston

Houston, Texas

Christopher Wagner, Ph.D.

Division of Substance Abuse Medicine

Virginia Commonwealth University

Richmond, Virginia

Resource Panel

Peter J. Cohen, M.D., J.D.

Adjunct Professor of Law

Georgetown University Law Center

Washington, D.C.

Frances Cotter, M.A., M.P.H.

Senior Public Health Advisor

Office of Managed Care

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration

Rockville, Maryland

Dorynne Czechowicz, M.D.

Associate Director

Division of Clinical and Services Research

Treatment Research Branch

National Institute on Drug Abuse

Bethesda, Maryland

James G. (Gil) Hill

Director

Office of Substance Abuse

American Psychological Association

Washington, D.C.

Linda Kaplan

Executive Director

National Association of Alcoholism and Drug

Abuse Counselors

Arlington, Virginia

Pedro Morales, J.D.

Director

Equal Employment Civil Rights

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration

Rockville, Maryland

Harold I. Perl, Ph.D.

Public Health Analyst

Division of Clinical and Prevention Research

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Bethesda, Maryland

Barbara J. Silver, Ph.D.

Center for Mental Health Services

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration

Rockville, Maryland

Lucretia Vigil

Policy Advisor

National Coalition of Hispanic Health and Human

Services Organization

Washington, D.C.

Editorial Advisory Board

Karen Allen, Ph.D., R.N., C.A.R.N.

Professor and Chair

Department of Nursing

Andrews University

Berrien Springs, Michigan

Richard L. Brown, M.D., M.P.H.

Associate Professor

Department of Family Medicine

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine

Madison, Wisconsin

Dorynne Czechowicz, M.D.

Associate Director

Medical/Professional Affairs

Treatment Research Branch

Division of Clinical and Services Research

National Institute on Drug Abuse

Rockville, Maryland

xix

TIP 35 Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Linda S. Foley, M.A.

Former Director

Project for Addiction Counselor Training

National Association of State Alcohol and Drug

Abuse Directors

Washington, D.C.

Wayde A. Glover, M.I.S., N.C.A.C. II

Director

Commonwealth Addictions Consultants and

Trainers

Richmond, Virginia

Pedro J. Greer, M.D.

Assistant Dean for Homeless Education

University of Miami School of Medicine

Miami, Florida

Thomas W. Hester, M.D.

Former State Director

Substance Abuse Services

Division of Mental Health, Mental Retardation and

Substance Abuse

Georgia Department of Human Resources

Atlanta, Georgia

James G. (Gil) Hill, Ph.D.

Director

Office of Substance Abuse

American Psychological Association

Washington, D.C.

Douglas B. Kamerow, M.D., M.P.H.

Director

Office of the Forum for Quality and Effectiveness in

Health Care

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Rockville, Maryland

Stephen W. Long

Director

Office of Policy Analysis

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Rockville, Maryland

Richard A. Rawson, Ph.D.

Executive Director

Matrix Center and Matrix Institute on Addiction

Deputy Director

UCLA Addiction Medicine Services

Los Angeles, California

Ellen A. Renz, Ph.D.

Former Vice President of Clinical Systems

MEDCO Behavioral Care Corporation

Kamuela, Hawaii

Richard K. Ries, M.D.

Director and Associate Professor

Outpatient Mental Health Services and Dual

Disorder Programs

Harborview Medical Center

Seattle, Washington

Sidney H. Schnoll, M.D., Ph.D.

Chairman

Division of Substance Abuse Medicine

Medical College of Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

xx

TIP 35

Publication Information

Acknowledgements

This publication was prepared under contract

numbers 270-95-0013, 270-14-0445, 270-19-0538,

and 283-17-4901 by the Knowledge Application

Program (KAP) for the Center for Substance

Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Sandra

Clunies, M.S., I.C.A.D.C., served as the Contracting

Officer’s Representative (COR) for initial Treatment

Improvement Protocol (TIP) development. Suzanne

Wise served as the COR; Candi Byrne as the

Alternate COR; and Reed Forman, M.S.W., as the

Project Champion for the TIP update.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions, and content expressed herein

are the views of the consensus panel members and

do not necessarily reflect the official position of

SAMHSA. No official support of or endorsement by

SAMHSA for these opinions or for the instruments

or resources described is intended or should be

inferred. The guidelines presented should not be

considered substitutes for individualized client care

and treatment decisions.

Public Domain Notice

All materials appearing in this publication

except those taken directly from copyrighted

sources are in the public domain and may be

reproduced or copied without permission from

SAMHSA or the authors. Citation of the source is

appreciated. However, this publication may not

be reproduced or distributed for a fee without

the specific, written authorization of the Office of

Communications, SAMHSA.

Electronic Access and Copies of

Publication

This publication may be ordered or downloaded

from SAMHSA’s Publications and Digital Products

webpage at https://store.samhsa.gov. Or, please

call SAMHSA at 1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726-

4727) (English and Español).

Recommended Citation

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration. Enhancing Motivation for

Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment.

Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series No.

35. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP19-02-01-003.

Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration, 2019.

Originating Oce

Quality Improvement and Workforce Development

Branch, Division of Services Improvement, Center

for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Services Administration, 5600

Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20857.

Nondiscrimination Notice

SAMHSA complies with applicable federal civil

rights laws and does not discriminate on the basis

of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or

sex. SAMHSA cumple con las leyes federales

de derechos civiles aplicables y no discrimina

por motivos de raza, color, nacionalidad, edad,

discapacidad, o sexo.

SAMHSA Publication No. PEP19-02-01-003

First printed 1999

Updated 2019

xxi

This page intentionally left blank

Chapter 1—A New Look at Motivation

Motivation to initiate and persist in change fluctuates over time

regardless of the person’s stage of readiness. From the client’s

perspective, a decision is just the beginning of change.”

—Miller & Rollnick, 2013, p. 293

TIP 35

ENHANCING MOTIVATION FOR CHANGE IN

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER TREATMENT

KEY MESSAGES

•

Motivation is the key to substance use

behavior change.

• Counselor use of empathy, not authority

and power, is essential to enhancing client

motivation to change.

• The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of the

Stages of Change (SOC) approach is a useful

overarching framework that can help you

tailor specific counseling strategies to the

different stages.

Why do people change? How is motivation linked

to substance use behavior change? How can you

help clients enhance their motivation to engage in

substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and initiate

recovery? This Treatment Improvement Protocol

(TIP) will answer these and other important

questions. Using the TTM of behavioral change as

a foundation, Chapter 1 lays the groundwork for

answering such questions. It offers an overview of

the nature of motivation and its link to changing

substance use behaviors. It also addresses the shift

away from abstinence-only addiction treatment

perspectives toward client-centered approaches

that enhance motivation and reduce risk.

In the past three decades, the addiction treatment

field has focused on discovering and applying

science-informed practices that help people with

SUDs enhance their motivation to stop or reduce

alcohol, drug, and nicotine use. Research and

clinical literature have explored how to help clients

sustain behavior change in ongoing recovery.

Such recovery support helps prevent or lessen the

social, mental, and health problems that result

from a recurrence of substance use or a relapse to

previous levels of substance misuse.

This TIP examines motivational enhancement

and substance use behavior change using two

science-informed approaches (DiClemente, Corno,

Graydon, Wiprovnick, & Knobloch, 2017):

1. Motivational interviewing (MI), which is a

respectful counseling style that focuses on

helping clients resolve ambivalence about

and enhance motivation to change health-risk

behaviors, including substance misuse

2. The TTM of the SOC, which provides an

overarching framework for motivational

counseling approaches throughout all phases of

addiction treatment

1

TIP 35 Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

KEY TERMS

Addiction*: The most severe form of SUD, associated with compulsive or uncontrolled use of one or

more substances. Addiction is a chronic brain disease that has the potential for both recurrence (relapse)

andrecovery.

Alcohol misuse: The use of alcohol in any harmful way, including use that constitutes alcohol use

disorder(AUD).

Alcohol use disorder: Per the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; APA, 2013), a diagnosis applicable to a person who uses

alcohol and experiences at least 2 of the 11 symptoms in a 12-month period. Key aspects of AUD include

loss of control, continued use despite adverse consequences, tolerance, and withdrawal. AUD covers a

range of severity and replaces what DSM-IV, termed “alcohol abuse” and “alcohol dependence” (APA,

1994).

Health-risk behavior: Any behavior (e.g., tobacco or alcohol use, unsafe sexual practices, nonadherence

to prescribed medication regimens) that increases the risk of disease or injury.

Recovery*: A process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a

self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential. Even individuals with severe and chronic SUDs can,

with help, overcome their disorder and regain health and social function. This is called remission. When

those positive changes and values become part of a voluntarily adopted lifestyle, that is called “being in

recovery.” Although abstinence from all substance misuse is a cardinal feature of a recovery lifestyle, it is

not the only healthy, pro-social feature.

Recurrence: An instance of substance use that occurs after a period of abstinence. Where possible,

this TIP uses the terms “recurrence” or “return to substance use” instead of “relapse,” which can have

negative connotations (see entry below).

Relapse*: A return to substance use after a significant period of abstinence.

Substance*: A psychoactive compound with the potential to cause health and social problems, including

SUDs (and their most severe manifestation, addiction). The table at the end of this exhibit lists common

examples of such substances.

Substance misuse*: The use of any substance in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that can cause

harm to users or to those around them. For some substances or individuals, any use would constitute

misuse (e.g., underage drinking, injection drug use).

Substance use*: The use—even one time—of any of the substances listed in the table at the end of

this exhibit.

Substance use disorder*: A medical illness caused by repeated misuse of a substance or substances.

According to DSM-5 (APA, 2013), SUDs are characterized by clinically significant impairments in health,

social function, and impaired control over substance use and are diagnosed through assessing cognitive,

behavioral, and psychological symptoms. SUDs range from mild to severe and from temporary to chronic.

They typically develop gradually over time with repeated misuse, leading to changes in brain circuits

governing incentive salience (the ability of substance-associated cues to trigger substance seeking),

reward, stress, and executive functions like decision making and self-control. Multiple factors influence

whether and how rapidly a person will develop an SUD. These factors include the substance itself; the

genetic vulnerability of the user; and the amount, frequency, and duration of the misuse. A severe SUD is

commonly called an addiction.

Chapter 1 2

TIP 35

Chapter 1—A New Look at Motivation

Substance Category Representative Examples

Alcohol

•

Beer

•

Wine

•

Malt liquor

•

Distilled spirits

Illicit Drugs

•

Cocaine, including crack

•

Heroin

•

Hallucinogens, including LSD, PCP, ecstasy, peyote, mescaline, psilocybin

•

Methamphetamines, including crystal meth

•

Marijuana, including hashish*

•

Synthetic drugs, including K2, Spice, and "bath salts"**

•

Prescription-type medications that are used for nonmedical purposes

−

Pain Relievers - Synthetic, semi-synthetic, and non-synthetic opioid

medications, including fentanyl, codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and

tramadol products

−

Tranquilizers, including benzodiazepines, meprobamate products, and

muscle relaxants

−

Stimulants and Methamphetamine, including amphetamine,

dextroamphetamine, and phentermine products; mazindol products;

and methylphenidate or dexmethylphenidate products

−

Sedatives, including temazepam, flurazepam, or triazolam and

anybarbiturates

Over-the-Counter

Drugs and Other

Substances

•

Cough and cold medicines**

•

Inhalants, including amyl nitrite, cleaning fluids, gasoline and lighter gases,

anesthetics, solvents, spray paint, nitrous oxide

*As of June 2016, 25 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana use, for states

have legalized retail marijuana sales, and the District of Columbia has legalized personal use and

home cultivation (both medical and recreational). It should be noted that none of the permitted uses

under state laws alter the status of marijuana and its constituent compounds as illicit drugs under

Schedule I of the federal Controlled Substances Act. See the section on Marijuana: A Changing Legal and

Research Environment in the Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol,

Drugs, and Health (Office of the Surgeon General, 2016). The report is available online (https://addiction.

surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf).

The definitions of all terms marked with an asterisk correspond closely to those in the Surgeon

General’sReport.

** These substances are not included in NSDUH and are not discussed in the Surgeon General's Report.

However, important facts about these drugs are included in Appendix D - Important Facts About Alcohol

and Drugs

Chapter 1 3

TIP 35

Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Motivation and Behavior Change

Motivation is a critical element of behavior

change (Flannery, 2017) that predicts client

abstinence and reductions in substance use

(DiClemente et al., 2017). You cannot give clients

motivation, but you can help them identify their

reasons and need for change and facilitate

planning for change. Successful SUD treatment

approaches acknowledge motivation as a

multidimensional, fluid state during which people

make difficult changes to health-risk behaviors,

like substance misuse.

The Nature of Motivation

The following factors define motivation and its

ability to help people change health-risk behaviors.

•

Motivation is a key to substance use behavior

change. Change, like motivation, is a complex

construct with evolving meanings. One

framework for understanding motivation and

how it relates to behavior changes is the self-

determination theory (SDT). SDT suggests that

people inherently want to engage in activities

that meet their need for autonomy, competency

(i.e., self-efficacy), and relatedness (i.e., having

close personal relationships) (Deci & Ryan, 2012;

Flannery, 2017). SDT describes two kinds of

motivation:

- Intrinsic motivation (e.g., desires, needs,

values, goals)

- Extrinsic motivation (e.g., social influences,

external rewards, consequences)

•

MI is a counseling approach that is consistent

with SDT and emphasizes enhancing internal

motivation to change. In the SDT framework,

providing a supportive relational context that

promotes client autonomy and competence

enhances intrinsic motivation, helps clients

internalize extrinsic motivational rewards, and

supports behavior change (Flannery, 2017;

Kwasnicka, Dombrowski, White, & Sniehotta,

2016; Moyers, 2014).

•

Contingency management is a counseling

strategy that can reinforce extrinsic

motivation. It uses external motivators or

reinforcers (e.g., expectation of a reward or

negative consequence) to enhance behavior

change (Sayegh, Huey, Zara, & Jhaveri, 2017).

•

Motivation helps people resolve their

ambivalence about making difficult lifestyle

changes. Helping clients strengthen their own

motivation increases the likelihood that they

will commit to a specific behavioral change plan

(Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Research supports the

importance of SDT-based client motivation in

positive addiction treatment outcomes (Wild,

Yuan, Rush, & Urbanoski, 2016). Motivation and

readiness to change are consistently associated

with increased help seeking, treatment

adherence and completion, and positive SUD

treatment outcomes (Miller & Moyers, 2015).

•

Motivation is multidimensional. Motivation

includes clients’ internal desires, needs, and

values. It also includes external pressures,

demands, and reinforcers (positive and negative)

that influence clients and their perceptions

about the risks and benefits of engaging in

substance use behaviors. Two components of

motivation predict good treatment outcomes

(Miller & Moyers, 2015):

-

The importance clients associate

withchanges

-

Their confidence in their ability to

makechanges

•

Motivation is dynamic and fluctuates.

Motivation is a dynamic process that responds

to interpersonal influences, including feedback

and an awareness of different available choices

(Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Motivation is a strong

predictor of addiction treatment outcomes

(Miller & Moyers, 2015). Motivation can fluctuate

over different stages of the SOC and varies

in intensity. It can decrease when the client

feels doubt or ambivalence about change and

increase when reasons for change and specific

goals become clear. In this sense, motivation

can be an ambivalent state or a resolute

commitment to act—or not to act.

Chapter 1 4

TIP 35

Chapter 1—A New Look at Motivation

•

Motivation is influenced by social interactions.

An individual’s motivation to change can be

positively influenced by supportive family and

friends as well as community support and

negatively influenced by lack of social support,

negative social support (e.g., a social network of

friends and associates who misuse alcohol), and

negative public perception of SUDs.

•

Your task is to elicit and enhance motivation.

Although change is the responsibility of

clients and many people change substance

use behaviors on their own without formal

treatment (Kelly, Bergman, Hoeppner, Vilsaint,

& White, 2017), you can enhance clients’

motivation for positive change at each stage

of the SOC process. Your task is not to teach,

instruct, or give unsolicited advice. Your role

is to help clients recognize when a substance

use behavior is inconsistent with their values

or stated goals, regard positive change to

be in their best interest, feel competent to

change, develop a plan for change, begin

taking action, and continue using strategies that

lessen the risk of a return to substance misuse

(Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Finally, you should

be sensitive and responsive to cultural factors

that may influence client motivation. For more

information about enhancing cultural awareness

and responsiveness, see TIP 59: Improving

Cultural Competence (Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Services Administration

[SAMHSA], 2014a).

•

Motivation can be enhanced. Motivation is

a part of the human experience. No one is

totally unmotivated (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Motivation is accessible and can be enhanced at

many points in the change process. Historically,

in addiction treatment it was thought that

clients had to “hit bottom” or experience

terrible, irreparable consequences of their

substance misuse to become ready to change.

Research now shows that counselors can help

clients identify and explore their desire, ability,

reasons, and need to change substance use

behaviors; this effort enhances motivation and

facilitates movement toward change (Miller &

Rollnick,2013).

•

Motivation is influenced by the counselor’s

style. The way you interact with clients impacts

how they respond and whether treatment is

successful. Counselor interpersonal skills are

associated with better treatment outcomes.

In particular, an empathetic counselor style

predicts increased retention in treatment and

reduced substance use across a wide range of

clinical settings and types of clients (Moyers

& Miller, 2013). The most desirable attributes

for the counselor mirror those recommended

in the general psychology literature and

include nonpossessive warmth, genuineness,

respect, affirmation, and empathy. In contrast,

an argumentative or confrontational style of

counselor interaction with clients, such as

challenging client defenses and arguing, tends

to be counterproductive and is associated with

poorer outcomes for clients, particularly when

counselors are less skilled (Polcin, Mulia, &

Jones, 2012; Roman & Peters, 2016).

COUNSELOR NOTE: ARE YOU

READY, WILLING, AND ABLE?

Motivation is captured, in part, in the popular

phrase that a person is ready, willing, and able

to change:

• “Ability” refers to the extent to which a person

has the necessary skills, resources, and

confidence to make a change.

• “Willingness” is linked to the importance a

person places on changing—how much a

change is wanted or desired. However, even

willingness and ability are not always enough.

• “Ready” represents a final step in which

a person finally decides to change a

particular behavior.

Your task is to help the client become ready,

willing, and able to change.

Chapter 1 5

TIP 35

Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Why Enhance Motivation?

Although much progress has been made in

identifying people who misuse substances and

who have SUD and in using science-informed

interventions such as motivational counseling

approaches to treat them, the United States is still

facing many SUD challenges. For example, the

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA,

2018) reports that, in 2017, approximately:

•

140.6 million Americans ages 12 and older

currently consumed alcohol, 66.6 million

engaged in past-month binge drinking (defined

as 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on at

least 1 day in the past 30 days for men and 4 or

more drinks on the same occasion on at least

1 day in the past 30 days for women), and 16.7

million drank heavily in the past month (defined

as binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past

30 days).

•

30.5 million people ages 12 and older had past-

month illicit drug use.

•

11.4 million people misused opioids (defined as

prescription pain reliever misuse or heroin use)

in the past year.

•

8.5 million adults ages 18 and older (3.4 percent

of all adults) had both a mental disorder and at

least one past-year SUD.

•

18.2 million people who needed SUD treatment

did not receive specialty treatment.

•

One-third of people who perceived a need for

addiction treatment did not receive it because

they lacked health insurance and could not pay

for services.

Enhancing motivation can improve addiction

treatment outcomes. In the United States, millions

of people with SUDs are not receiving treatment.

Many do not seek treatment because their

motivation to change their substance use behaviors

is low. Motivational counseling approaches are

associated with greater participation in treatment

and positive treatment outcomes. Such outcomes

include increased motivation to change; reductions

in consumption of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis,

and other substances; increased abstinence rates;

higher client confidence in ability to change

behaviors; and greater treatment engagement

(Copeland, McNamara, Kelson, & Simpson, 2015;

DiClemente et al., 2017; Lundahl et al., 2013;

Smedslund et al., 2011).

The benefits of motivational enhancement

approaches include:

•

Enhancing motivation to change.

•

Preparing clients to enter treatment.

•

Engaging and retaining clients in treatment.

•

Increasing participation and involvement.

•

Improving treatment outcomes.

•

Encouraging rapid return to treatment if clients

return to substance misuse.

Changing Perspectives on

Addiction and Treatment

Historically, in the United States, different views

about the nature of addiction and its causes

have influenced the development of treatment

approaches. For example, after the passage of

the Harrison Narcotics Act in 1914, it was illegal

for physicians to treat people with drug addiction.

The only options for people with alcohol or drug

use disorders were inebriate homes and asylums.

The underlying assumption pervading these early

treatment approaches was that alcohol and drug

addiction was either a moral failing or a pernicious

disease (White, 2014).

By the 1920s, compassionate treatment of opioid

addiction was available in medical clinics. At

the same time, equally passionate support for

the temperance movement, with its focus on

drunkenness as a moral failing and abstinence as

the only cure, was gaining momentum.

The development of the modern SUD treatment

system dates only from the late 1950s. Even

“modern” addiction treatment has not always

acknowledged counselors’ capacity to support

client motivation. Historically, motivation was

considered a static client trait; the client either

had it or did not have it, and there was nothing a

counselor could do to influence it.

This view of motivation as static led to blaming

clients for tension or discord in therapeutic

Chapter 1 6

TIP 35Chapter 1—A New Look at Motivation

relationships. Clients who disagreed with

diagnoses, did not adhere to treatment plans, or

refused to accept labels like “alcoholic” or “drug

addict” were seen as difficult or resistant (Miller &

Rollnick, 2013).

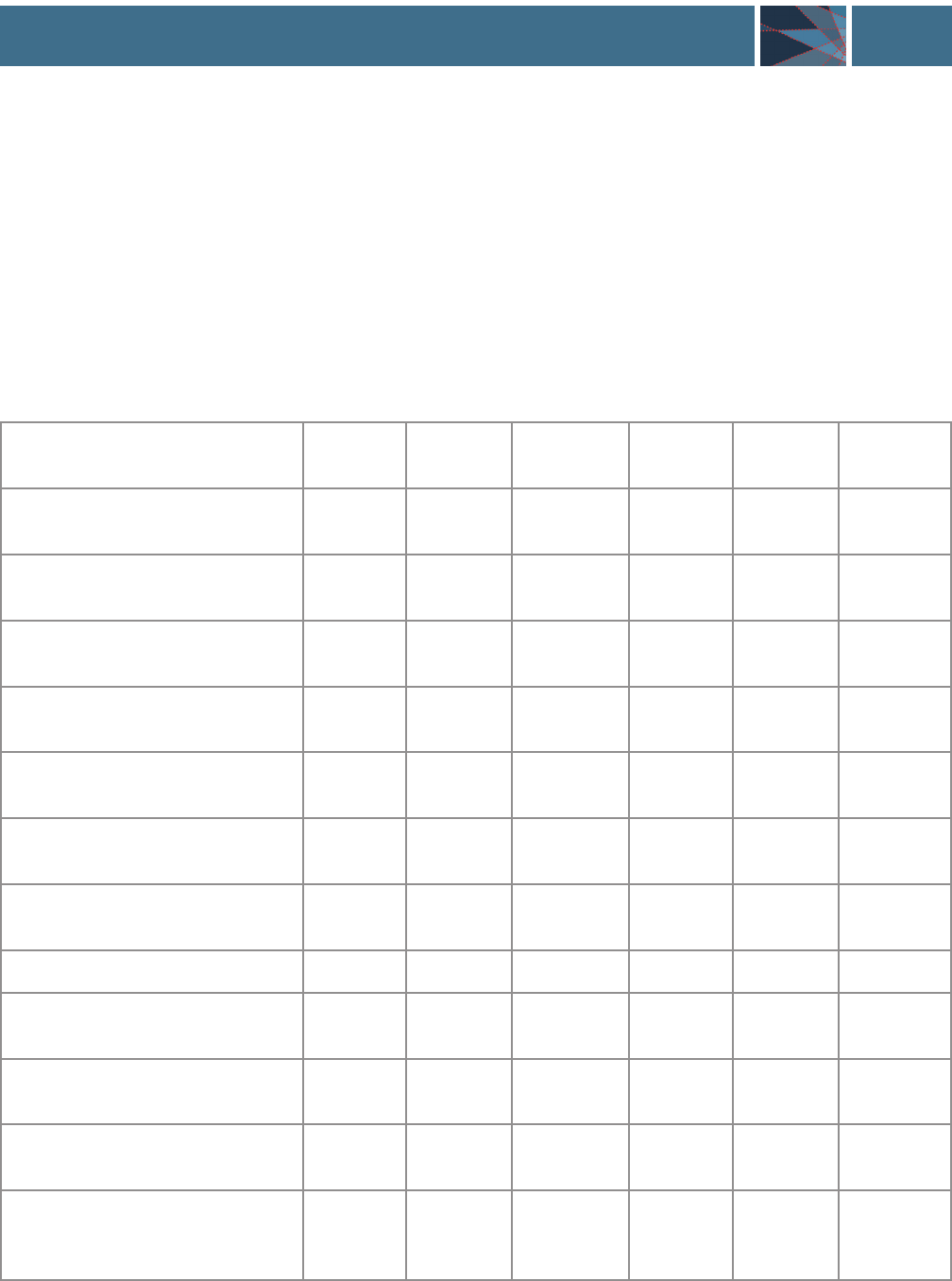

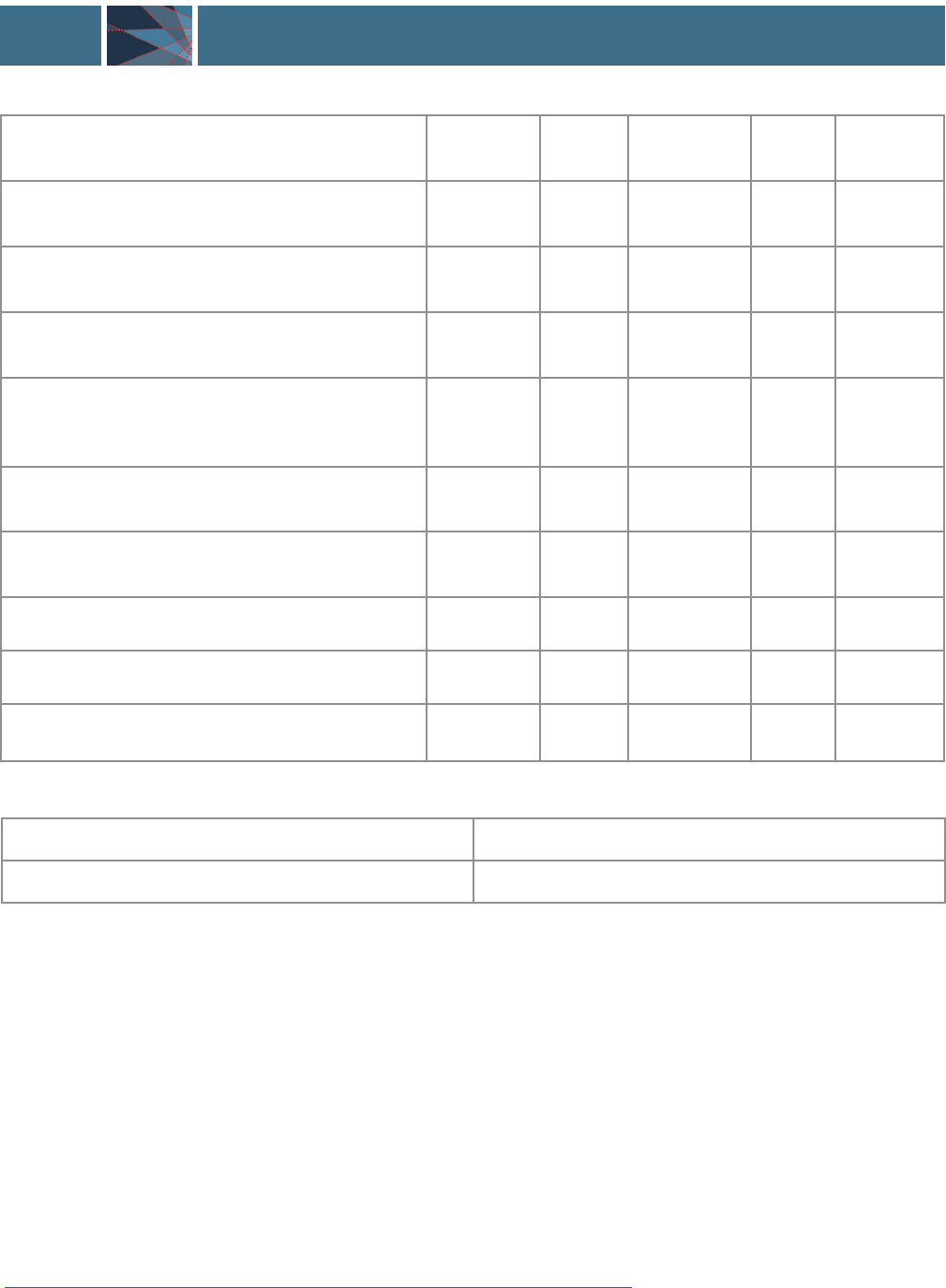

EXHIBIT 1.1. Models of Addiction

SUD treatment has since evolved in response

to new technologies, research, and theories of

addiction with associated counseling approaches.

Exhibit 1.1 summarizes some models of addiction

that have influenced treatment methods in the

United States (DiClemente, 2018).

MODEL UNDERLYING ASSUMPTIONS TREATMENT APPROACHES

Moral/legal Addiction is a set of behaviors

that violates religious, moral, or

legalcodes.

Abstinence and use of willpower

External control through hospitalization

orincarceration

Psychological Addiction results from deficits in

learning, emotional dysfunction,

orpsychopathology.

Cognitive, behavioral, psychoanalytic, or

psychodynamic psychotherapies

Sociocultural Addiction results from socialization

and sociocultural factors.

Contributing factors include

socioeconomic status, cultural

Focus on building new social and

family relationships, developing social

competency and skills, and working within a

client’sculture

and ethnic beliefs, availability of

substances, laws and penalties

regulating substance use, norms

and rules of families and other

social groups, parental and

peer expectations, modeling of

acceptable behaviors, and the

presence or absence of reinforcers.

Spiritual Addiction is a spiritual disease.

Recovery is predicated on a

recognition of the limitations of the

self and a desire to achieve health

through a connection with that

which transcends the individual.

Integrating 12-Step recovery principles or

other culturally based spiritual practices (e.g.,