50-State Property Tax Comparison Study, Copyright © June 2021

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from Lincoln Institute of

Land Policy and Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence

For information contact:

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Department of Valuation and Taxation

113 Brattle Street

Cambridge, MA 02138

617-661-3016

Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence

85 East 7th Place, Suite 250

Saint Paul, Minnesota 55101

651-224-7477

Cover image: © iStockphoto/Aneese

Acknowledgements

This report would not have been possible without the cooperation and assistance of many

individuals. Research, calculations, and drafting were done by Bob DeBoer

2

and Adam H.

Langley

1

. The report benefits greatly from the architecture and ongoing design provided by

Aaron Twait

2

, and feedback from Anthony Flint

1

, Mark Haveman

2

, Will Jason

1

, Daphne A.

Kenyon

1

, George W. McCarthy

1

, Emily McKeigue

1

, Semida Munteanu

1

, Andrew Reschovsky

1

,

and Joan M. Youngman

1

.

1

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

2

Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence

About the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy seeks to improve quality of life through the effective use,

taxation, and stewardship of land. A nonprofit private operating foundation whose origins date to

1946, the Lincoln Institute researches and recommends creative approaches to land as a solution

to economic, social, and environmental challenges. Through education, training, publications,

and events, we integrate theory and practice to inform public policy decisions worldwide. We

focus our work on the achievement of six major goals: low-carbon, climate-resilient

communities and regions, efficient and equitable tax systems, reduced poverty and spatial

inequality, fiscally healthy communities and regions, sustainably managed land and water

resources, and functional land markets and reduced informality.

About the Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence

The Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence was founded in 1926 to promote sound tax policy,

efficient spending, and accountable government.

We pursue this mission by

• educating and informing Minnesotans about sound fiscal policy

• providing state and local policy makers with objective, non-partisan research about the

impacts of tax and spending policies

• advocating for the adoption of policies reflecting principles of fiscal excellence.

MCFE generally defers from taking positions on levels of government taxation and spending

believing that citizens, through their elected officials, are responsible for determining the level of

government they are willing to support with their tax dollars. Instead, MCFE seeks to ensure that

revenues raised to support government adhere to good tax policy principles and that the spending

supported by these revenues accomplishes its purpose in an efficient, transparent, and

accountable manner.

The Center is a non-profit, non-partisan group supported by membership dues. For information

about membership, call (651) 224-7477, or visit our web site at www.fiscalexcellence.org.

50-State Property Tax Comparison Study

For Taxes Paid in 2020

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6

Why Property Tax Rates Vary Across Cities .................................................................................. 9

Homestead Property Taxes ............................................................................................................ 14

Commercial Property Taxes .......................................................................................................... 20

Industrial Property Taxes .............................................................................................................. 25

Apartment Property Taxes ............................................................................................................. 30

Classification and Preferential Treatment of Homestead Properties ............................................. 34

Property Tax Assessment Limits ................................................................................................... 41

Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 44

Appendix Tables

1. Why Property Tax Rates Vary Across Cities

1a. Factors Correlated with Homestead Property Tax Rates in Large U.S. Cities ................. 52

1b. Factors Correlated with Commercial Property Tax Rates in Large U.S. Cities ............... 55

1c. Correlates of Cities’ Effective Tax Rates on Homestead Properties ................................ 58

1d. Correlates of Cities’ Effective Tax Rates on Commercial Properties .............................. 59

2. Homestead Property Taxes

2a. Largest City in Each State: Median Valued Homes ......................................................... 60

2b. Largest City in Each State: Median Valued Homes, with Assessment Limits ................ 62

2c. Largest City in Each State: Homes worth $150,000 and $300,000 ................................. 64

2d. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities: Median Valued Homes ........................................................... 66

2e. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities: Median Valued Homes, with Assessment Limits ................... 68

2f. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities: Homes worth $150,000 and $300,000 ..................................... 70

2g. Selected Rural Municipalities: Median Valued Homes ................................................... 72

2h. Selected Rural Municipalities: Homes worth $150,000 and $300,000 ............................ 74

3. Commercial Property Taxes

3a. Largest City in Each State ................................................................................................ 76

3b. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities ................................................................................................... 78

3c. Selected Rural Municipalities .......................................................................................... 80

4. Industrial Property Taxes

4a. Largest City in Each State (Personal Property = 50% of Total Parcel Value) ................. 82

4b. Largest City in Each State (Personal Property = 60% of Total Parcel Value) ................. 84

4c. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities (Personal Property = 50% of Total Parcel Value) .................... 86

4d. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities (Personal Property = 60% of Total Parcel Value) ................... 88

4e. Selected Rural Municipalities (Personal Property = 50% of Total Parcel Value) ........... 90

4f. Selected Rural Municipalities (Personal Property = 60% of Total Parcel Value) ............ 92

4g. Preferential Treatment of Personal Property, Largest City in Each State ........................ 94

5. Apartment Property Taxes

5a. Largest City in Each State ................................................................................................ 96

5b. Largest Fifty U.S. Cities ................................................................................................... 98

5c. Selected Rural Municipalities ........................................................................................ 100

6. Classification and Preferential Treatment of Homestead Properties

6a. Commercial-Homestead Classification Ratio for Largest City in Each State ................ 102

6b. Apartment-Homestead Classification Ratio for Largest City in Each State .................. 104

7. Impact of Assessment Limits .................................................................................................. 106

1

Executive Summary

As the largest source of revenue raised by local governments, a well-functioning property tax

system is critical for promoting municipal fiscal health. This report documents the wide range of

property tax rates in more than 100 U.S. cities and helps explain why they vary so widely. This

context is important because high property tax rates usually reflect some combination of: 1.)

heavy property tax reliance with low sales and income taxes, 2.) low home values that drive up

the tax rate needed to raise enough revenue, or 3.) higher local government spending and better

public services. In addition, some cities operate in an environment where the state uses property

tax classification, which can result in considerably higher tax rates on business and apartment

properties than on homesteads.

This report provides the most meaningful data available to compare cities’ property taxes by

calculating the effective tax rate: the tax bill as a percent of a property’s market value. Data are

available for 73 large U.S. cities and a rural municipality in each state, with information on four

different property types (homestead, commercial, industrial, and apartment properties), and

statistics on both net tax bills (i.e. $3,000) and effective tax rates (i.e. 1.5 percent). These data

have important implications for cities because the property tax is a key part of the package of

taxes and public services that affects cities’ competitiveness and quality of life.

Why Property Tax Rates Vary Across Cities

To understand why property tax rates are high or low in a particular city, it is critical to know

why property taxes vary so much across cities. This report uses statistical analysis to identify

four key factors that explain most of the variation in property tax rates.

Property tax reliance is one of the main reasons why tax rates vary across cities. While some

cities raise most of their revenue from property taxes, others rely more on alternative revenue

sources. Cities with high local sales or income taxes do not need to raise as much revenue from

the property tax, and thus have lower property tax rates on average. For example, this report

shows that Bridgeport (CT) has one of the highest effective tax rates on a median valued home,

while Birmingham (AL) has one of the lowest rates. However, in Bridgeport, city residents pay

no local sales or income taxes, whereas Birmingham residents pay both sales and income taxes to

local governments. Consequently, despite the fact that Bridgeport has much higher property

taxes, total local taxes are considerably higher in Birmingham ($2,995 vs. $2,155 per capita).

Property values are the other crucial factor explaining differences in property tax rates. Cities

with high property values can impose a lower tax rate and still raise at least as much property tax

revenue as a city with low property values. For example, consider San Francisco and Detroit,

which have the highest and lowest median home values in this study. After accounting for

assessment limits, the average property tax bill on a median valued home for the large cities in

this report is $3,379. To raise that amount from a median valued home, the effective tax rate

would need to be 20 times higher in Detroit than in San Francisco – 5.74 percent versus 0.28

percent.

Two additional factors that help explain variation in tax rates are the level of local government

spending and whether cities tax homesteads at lower rates than other types of property (referred

2

to as “classification”). Holding all else equal, cities with higher spending will need to have

higher property tax rates. Classification imposes lower property taxes on homesteads, but higher

property taxes on business and apartment properties.

Homestead Property Taxes

There are wide variations across the country in property taxes on owner-occupied primary

residences, otherwise known as homesteads. An analysis of the largest city in each state shows

that the average effective tax rate on a median-valued homestead was 1.379 percent in 2020 for

this group of 53 cities.

1

At that rate, a home worth $200,000 would owe $2,758 in property taxes

(1.379% x $200,000). On the high end, there are four cities with effective tax rates that are at

least 2 times higher than the average – Aurora (IL), Newark, Bridgeport (CT), and Detroit.

Conversely, there are eight cities where tax rates are half of the study average or less – Honolulu,

Charleston (SC), Boston, Denver, Charleston (WV), Cheyenne (WY), Salt Lake City, and

Birmingham (AL).

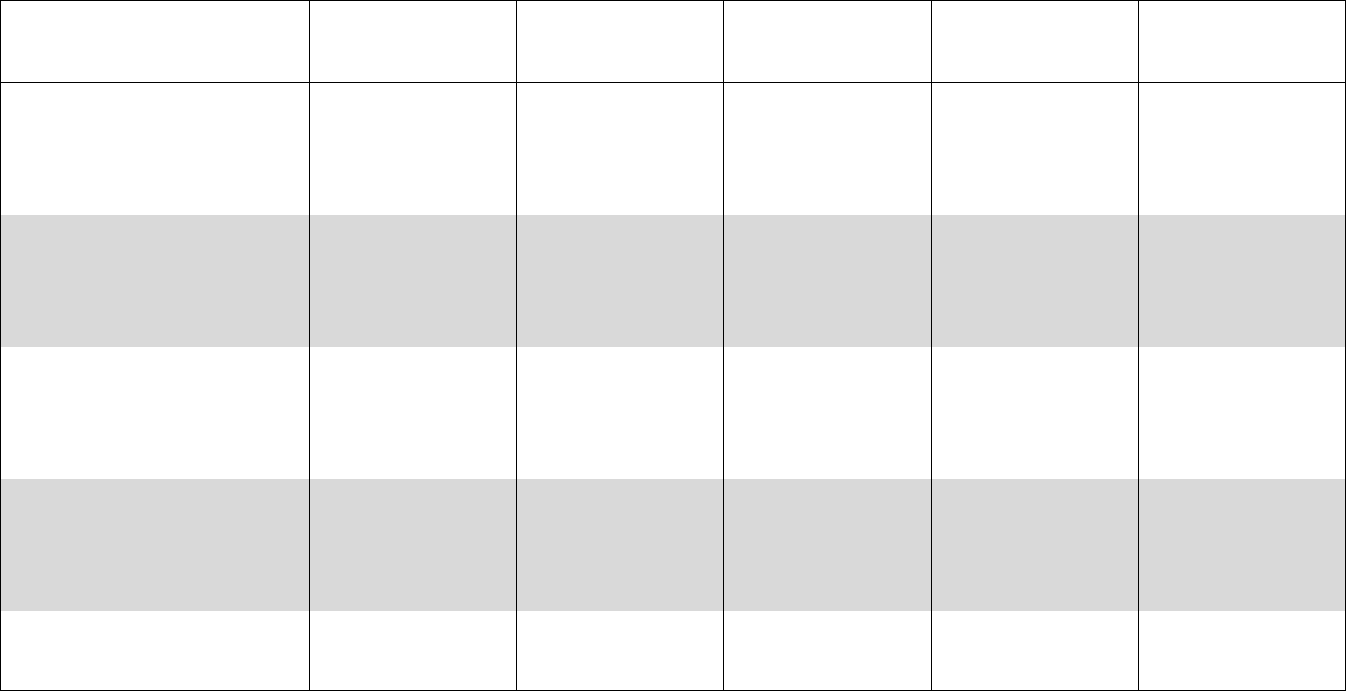

Highest and Lowest Effective Property Tax Rates on a Median Valued Home (2020)

Highest Property Tax Rates

Lowest Property Tax Rates

1

Aurora (IL)

3.25%

Why: High property tax reliance

49

Charleston (WV)

0.59%

Why: Classification shifts tax to

business, Low property tax reliance

2

Newark (NJ)

3.20%

Why: High property tax reliance

50

Denver (CO)

0.52%

Why: Low property tax reliance,

classification, high home values

3

Bridgeport (CT)

3.00%

Why: High property tax reliance

51

Boston (MA)

0.48%

Why: High home values,

Classification shifts tax to business

4

Detroit (MI)

2.83%

Why: Low property values

52

Charleston (SC)

0.48%

Why: Classification shifts tax to

business, High home values

5

Portland (OR)

2.48%

Why: Assessment limit shifts tax

to newly built homes

53

Honolulu (HI)

0.31%

Why: High home values, low local

gov’t spending, classification

Note: Data for all cities: Figure 2 (page 18), Appendix Table 1a (page 51), and Appendix Table 2a (page 59).

The average tax rate for these 53 cities fell 1.1 percent between 2019 and 2020, from 1.395

percent to 1.379 percent. This drop was on the heels of a 3.5 percent decrease in the preceding

year. From 2019 to 2020, decreases were large enough in 24 cities to more than offset increases

in 29 cities, as many of the increases were very small. The largest increase was in Nashville at

nearly 34 percent, due to an increase in the total local mill rate. However, Nashville still has a

relatively low effective tax rate, so the city’s ranking change is less remarkable: from 47

th

to 42

nd

place. The next largest increases were five cities that rose more than 5 percent, led by Jackson

(MS) at 8 percent, followed by Seattle, Des Moines, Atlanta, and Newark.

Buffalo led the way in effective tax rate decreases at 39 percent after ranking 15

th

in 2019. The

local mill rates were slashed by one-third overall in 2020, resulting in a drop of 22 places to 37

th

place. The next largest decreases were in Charleston (WV) at 29 percent, Columbus (OH) at 13

percent, and Portland (ME) at 9 percent.

1

The largest cities in each state includes 53 cities, because it includes Washington (DC) plus two cities in Illinois

and New York since property taxes in Chicago and New York City are so different than the rest of the state.

3

Note that differences in property values across cities mean that some cities with high tax rates

can still have low tax bills on a median valued home if they have low home values, and vice

versa. For example, Los Angeles and Wichita (KS) have similar effective tax rates of 1.19 and

1.17 percent on median valued homes, but because the median valued home is worth so much

more in Los Angeles ($697k vs. $147k), the tax bill is far higher in Los Angeles (3

rd

highest)

than in Wichita (47

th

highest).

Effective tax rates rise with home values in about half of the cities (26 of 53), and this pattern has

a progressive impact on the property tax distribution. Usually, this relationship occurs because of

homestead exemptions that are set to a fixed dollar amount. For example, a $20,000 exemption

provides a 20 percent tax cut on a $100,000 home, a 10 percent cut on a $200,000 home, and a 5

percent cut on a $400,000 home. The increase in effective tax rates with home values is steepest

in Boston, Atlanta, Honolulu, Washington (DC), and New Orleans.

Commercial Property Taxes

There are also significant variations across cities in commercial property taxes, which include

taxes on office buildings and similar properties. In 2020, the effective tax rate on a commercial

property worth $1 million averaged 1.953 percent across the largest cities in each state. The

highest rates were in Detroit and Chicago, where effective tax rates were more than twice the

average for these 53 cities. On the other hand, rates were less than half of the average in

Cheyenne (WY), Seattle, and Charlotte.

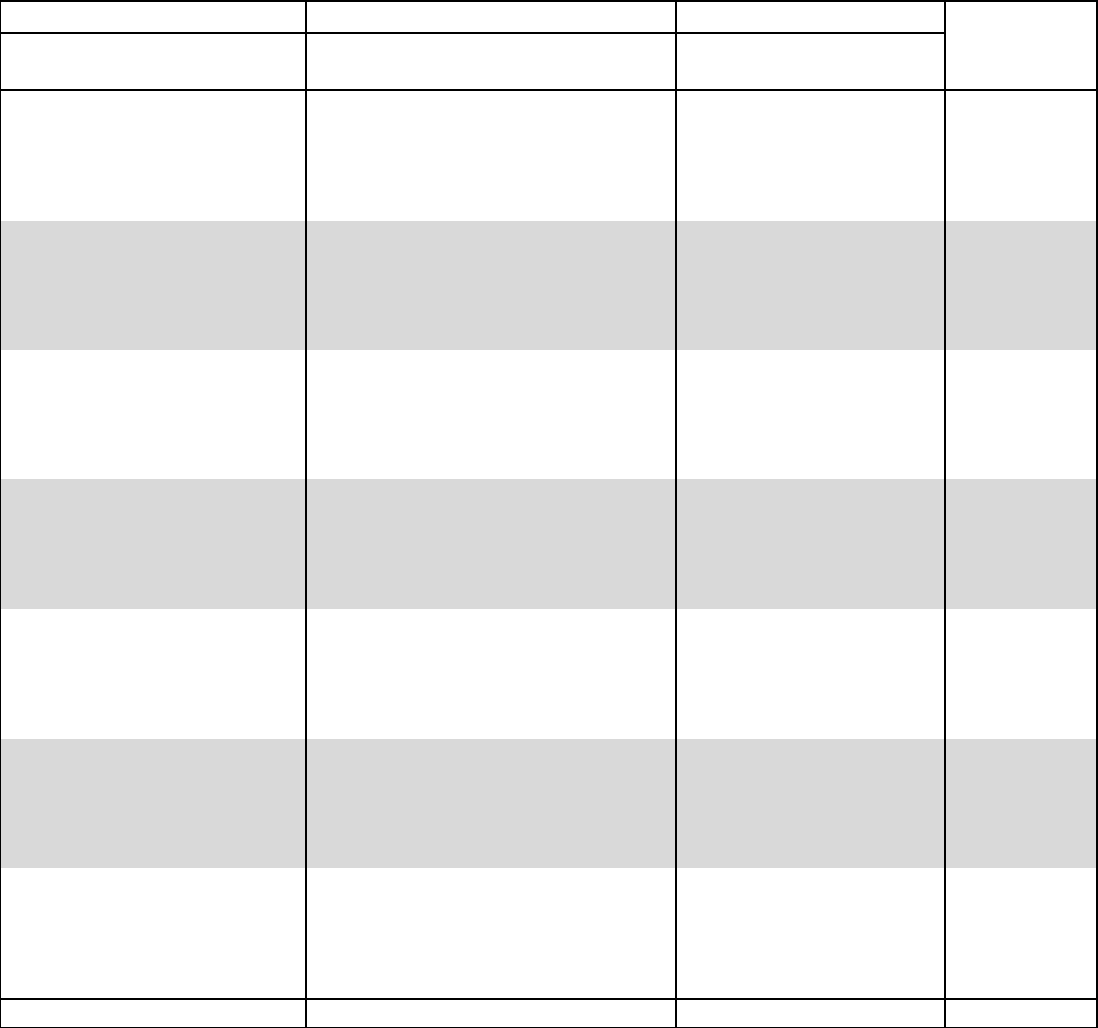

Highest and Lowest Effective Property Tax Rates on $1-Million Commercial Property

Highest Property Tax Rates

Lowest Property Tax Rates

1

Detroit (MI)

4.16%

Why: Low property values

49

Virginia Beach (VA)

1.03%

Why: Low local gov’t spending,

High property values

2

Chicago (IL)

4.03%

Why: High local gov’t spending,

Classification shifts tax to business

50

Boise (ID)

1.03%

Why: Low local gov’t spending,

High property values

3

Bridgeport (CT)

3.67%

Why: High property tax reliance

51

Charlotte (NC)

0.91%

Why: Low property tax reliance

4

Providence (RI)

3.61%

Why: High property tax reliance

52

Seattle (WA)

0.83%

Why: High property values,

Low property tax reliance

5

Des Moines (IA)

3.42%

Why: Low property values,

High property tax reliance

53

Cheyenne (WY)

0.67%

Why: Low property tax reliance

Note: Analysis includes an additional $200k in fixtures (office equipment, etc.)

Data for all cities: Figure 3 (page 23), Appendix Table 1b (page 54), and Appendix Table 3a (page 75).

Wilmington (DE) had the largest increase at 41 percent, moving the city up from 47

th

to 32

nd

place, returning close to their 2018 ranking of 35

th

place. Just like homes, the commercial rate

rose in Nashville by 34 percent, raising the city’s ranking from 48

th

to 37

th

place. Other double-

digit increases were found in Chicago (15.5 percent), Sioux Falls and Des Moines (13.5 percent),

Bridgeport (11.5 percent), and Detroit (10 percent).

The largest rate decrease was found in Buffalo, where a 38 percent decrease produced a drop in

ranking from 19

th

to 41

st

place. The only other double-digit decrease was Boise (13.5 percent). In

addition, Philadelphia, Salt Lake City, Denver, and Portland (ME) all had decreases of more than

5 percent.

4

Preferential Treatment for Homeowners

Many cities have preferences built into their property tax systems that result in lower effective

tax rates for certain classes of property, with these features usually designed to benefit

homeowners. The “classification ratio” describes these preferences by comparing the effective

tax rate on land and buildings for two types of property. For example, if a city has a 3.0%

effective tax rate on commercial properties and a 1.5% effective tax rate on homestead

properties, then the commercial-homestead classification ratio is 2.0 (3.0% divided by 1.5%).

An analysis of the largest cities in each state shows an average commercial-homestead

classification ratio of 1.77, meaning that on average commercial properties experience an

effective tax rate that is 77 percent higher than homesteads. Nearly a third of the cities (17 of 53)

have classification ratios above 2.0, meaning that commercial properties face an effective tax

rate that is at least double that for homesteads led by Boston at 4.7.

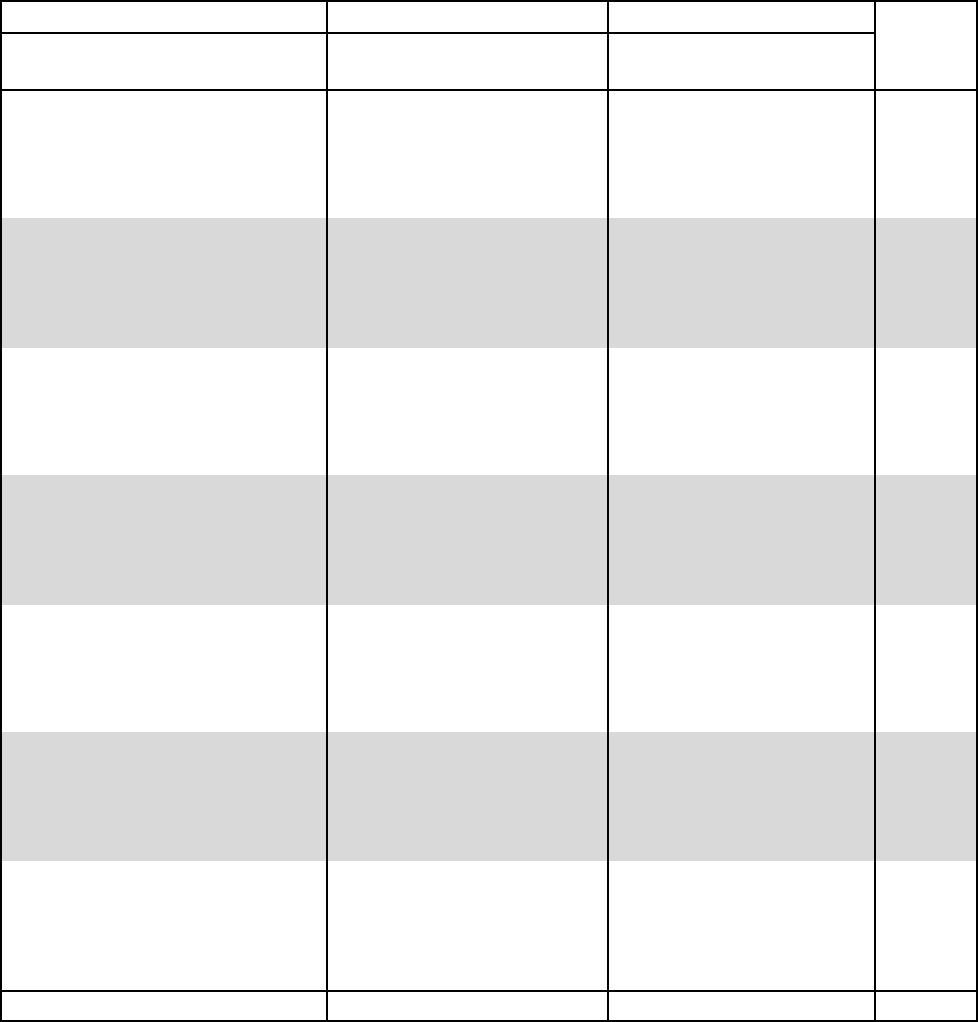

Preferential Treatment of Homeowners: Ratio of Effective Tax Rate on

Commercial and Apartment Properties to the Rate on Homestead Properties (2020)

Commercial vs. Homestead Ratio

Apartment vs. Homestead Ratio

1

Boston (MA)

4.72

1

Charleston (SC)

3.66

2

Honolulu (HI)

4.10

2

New York (NY)

2.55

3

Denver (CO)

4.01

3

Indianapolis (IN)

2.43

4

Charleston (SC)

3.66

4

Jacksonville (FL)

2.36

5

Chicago (IL)

3.25

5

Birmingham (AL)

2.16

Note: Commercial-homestead ratio compares rate on $1 million commercial building to median valued home.

Apartment-homestead ratio compares rate on $600k apartment building to median valued home.

Ratios compare taxes on real property and exclude personal property.

Data for all cities: Figures 6a and 6b (Pages 37-38), Appendix Table 6a (Pg. 101), and Appendix Table 6b (Pg. 103).

The average apartment-homestead classification ratio is significantly lower (1.33), with

apartments facing an effective tax rate that is 33% higher than homesteads on average. There are

six cities where apartments face an effective tax rate that is more than double that for

homesteads, with Charleston (SC) as the biggest outlier where the rate for apartments is 3.7

times higher than the rate on a median valued home. It is important to note that while renters do

not pay property tax bills directly, they do pay property taxes indirectly since landlords are able

to pass through some or all of their property taxes in the form of higher rents.

There are four types of statutory preferences built into property tax systems that can lead to

lower effective tax rates on homesteads than other property types: the assessment ratio, the

nominal tax rate, exemptions and credits, and differences in assessment limits. In total, 40 of the

53 cities have statutory preferences that favor homesteads over commercial properties. 21 of

these 40 cities benefit homeowners using at least two of these four statutory preferences. In 11

cities preferential treatment for homeowners is delivered through exemptions or credits alone,

while in 8 cities preferences are delivered exclusively through differences in assessment ratios or

nominal tax rates. Similarly, 36 cities have statutory preferences favoring homesteads relative to

apartments, but only 12 offer more than one preference. Seven cities have preferential

assessment ratios and/or nominal tax rates only, while 17 cities offer homestead exemptions or

credits alone.

5

Property Tax Assessment Limits

Since the late 1970s, an increasing number of states have adopted property tax limits, including

constraints on tax rates, tax levies, and assessed values. This report accounts for the impact of

limits on tax rates and levies implicitly, because of how these laws impact cities’ tax rates, but it

is necessary to use an explicit modeling strategy to account for assessment limits.

Assessment limits typically restrict growth in the assessed value for individual parcels and then

reset the taxable value of properties when they are sold. Therefore, the level of tax savings

provided from assessment limits largely depends on two factors: how long a homeowner has

owned her home and appreciation of the home’s market value relative to the allowable growth of

its assessed value. As a result, assessment limits can lead to major differences in property tax

bills between owners of nearly identical homes based on how long they have owned their home.

This report estimates the impact of assessment limits by calculating the difference in taxes

between newly purchased homes and homes that have been owned for the average duration in

each city, for median valued homes. For example, in Los Angeles, the average home has been

owned for 15 years and the median home value is $697,200. Because of the state’s assessment

limit, someone who has owned their home for 15 years would pay 47 percent less in property

taxes than the owner of a newly purchased home, even though both homes are worth $697,200.

The largest discrepancy is in New York City, which has an assessment limit that has capped

growth in assessed values for residential properties since 1981, and unlike most assessment

limits does not reset when the property is sold. As a result, the owner of a newly built, median-

valued home would face an effective tax rate 56 percent higher than the owner of a home built

prior to 1981, even though the two homes have identical values ($680,800). Assessment limits

reduce taxes by 30% or more in New York City, the eight California cities studied, the two

Florida cities studied, Detroit, Phoenix, and Portland (OR). Of the 29 cities in this report that are

affected by parcel-specific assessment limits, new homeowners face higher property tax bills

than existing homeowners in 22 cities. No 2020 home value was sheltered in all seven Texas

cities studied: Arlington, Austin, Dallas, El Paso, Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio.

Conclusion

Property taxes range widely across cities in the United States. This report not only shows which

cities have high or low effective property tax rates, but also explains why. Cities will tend to

have higher property tax rates if they have high property tax reliance, low property values, or

high local government expenditures. In addition, some cities use property tax classification,

which can result in considerably higher tax rates on business and apartment properties than on

homesteads. By calculating the effective property tax rate, this report provides the most

meaningful data available to compare cities’ property tax burdens. These data have important

implications for cities because the property tax is a key part of the package of taxes and public

services that affects cities’ competitiveness and quality of life.

6

Introduction

The property tax is one of the largest taxes paid by American households and businesses and

funds many essential public services, including K-12 education, police and fire protection, and a

wide range of critical infrastructure. Yet it is surprisingly difficult to get good data on property

taxes that are comparable across cities. This report provides the necessary data by accounting for

several key features of major cities’ property tax systems and then calculating the effective tax

rate: the tax bill as a percent of a property’s market value.

High or low effective property tax rates do not in themselves indicate that tax systems are “good”

or “bad.” Evaluating a property tax system requires a broader understanding of the pros and cons

of the property tax, the implications of high or low property tax rates, and the method by which

property tax rates are set. These key issues are outlined below.

The property tax has key strengths as a revenue instrument for local governments: it is the

most stable tax source, it is more progressive than alternative revenue options, and it promotes

local autonomy. Property taxes are more stable over the business cycle than sales and especially

income taxes, so greater property tax reliance helps local governments avoid major revenue

shortfalls during recessions. It also helps localities maintain revenue stability in the face of

fluctuating state and federal aid.

2

In addition, the property tax is relatively progressive compared

to the sales tax, which is the other main source of tax revenue for local governments. Whereas

the property tax is largely neutral, the sales tax is highly regressive.

3

The property tax is particularly appropriate for local governments because it is imposed on an

immobile tax base. While it is often easy to cross borders in search of a lower sales tax rate,

those who wish to live or locate their business in a particular location cannot avoid paying the

property tax. Thus, local governments have limited ability to charge different sales tax rates than

their neighbors, but have greater control over setting their property tax rate.

A drawback of any local tax is that the tax base can vary widely across communities, but these

disparities can be offset with state aid to local governments. For example, there are significant

differences in property values across communities, just as there are wide disparities in retail sales

and incomes across localities. State government grants to local governments can help offset these

differences to ensure everyone has access to necessary services at affordable tax prices

regardless of where they live. In addition, state-funded circuit breaker programs can help

households whose property taxes are particularly high relative to their income.

4

Property taxes are one part of the package of taxes and public services that affects

competitiveness and quality of life. This report shows that many of the cities with high property

tax rates have relatively low sales and income taxes for local governments, so the total local tax

2

Ronald C. Fisher. 2009. “What Policy Makers Should Know About Property Taxes.” Land Lines. Cambridge, MA:

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

3

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. 2015. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All

50 States.”

4

Bowman, John H., Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin. 2009. “Property Tax Circuit

Breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers.” Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

7

burden for residents and business could still be attractive. Furthermore, state aid may reduce

local property taxes, but this reduction may be offset by higher state taxes.

Similarly, if higher property taxes are used to pay for better public services, then high property

tax rates may not affect competitiveness or quality of life. Many homeowners are willing to pay

higher property taxes to have better public schools and safer neighborhoods. The bottom line is

that it is the total state-local tax burden relative to the quality of public services that determines

competitiveness and quality of life.

Property tax rates are set differently than other tax rates and reflect decisions about local

government spending. Income and sales tax rates usually do not vary much from year-to-year,

which leads to significant revenue fluctuations over the business cycle. In contrast, property tax

rates are usually established after the local government budget is determined by elected officials

and/or voters and the rate is then set to raise the targeted revenue level. However, flexibility in

setting property tax rates can be constrained by state tax limits or political concerns about

property tax burdens. The process for determining property tax rates varies across jurisdictions.

This report allows for meaningful comparisons of cities’ property taxes by calculating the

effective property tax rate—the tax bill as a percent of a property’s market value. For most

taxpayers, the effective tax rate will be significantly different from the nominal or official tax

rate that appears on their tax bill. There are several reasons for this difference. First, many states

only tax a certain percentage of a property’s market value. For example, New Mexico assesses

all property at 33.3 percent of market value for tax purposes, which means that a $300,000 home

would be taxed as if it were worth $100,000. In addition, many states and cities use exemptions

and/or credits to reduce property taxes. For example, a $50,000 homestead exemption would

mean a $200,000 home would be taxed as if it were worth $150,000. Cities also vary in the

accuracy of their assessments of property values for tax purposes. Finally, an analysis of property

tax burdens requires consideration of property taxes paid to all local governments, including

overlying counties and school districts, rather than simply comparing municipal tax rates. This

report accounts for all of these differences in cities’ property tax systems, which is essential for

meaningful comparisons of their tax rates.

This study calculates effective tax rates by analyzing several key features of each city’s

property tax system; it is not a parcel-level analysis of property tax liabilities. The Methodology

section of this report provides details on how effective tax rates are calculated. First, data are

collected for the key elements of property tax systems that determine effective tax rates:

• Total local property tax rate: The nominal tax rate that is most prevalent in the city for

each class of property (a.k.a. statutory tax rate), including taxes paid to the state, city or

township, county, school district, and special taxing districts.

• Assessment ratio (a.k.a. classification rate): The percentage of market value used to

establish a property’s assessed value. For example, a 60 percent assessment ratio means a

$100,000 home would be taxed as if it were worth $60,000.

• Sales ratio: The sales ratio measures the accuracy of assessments by comparing assessed

values to actual sales prices. For example, a 98 percent sales ratio means a $100,000

home would be “on the books” as if it were worth $98,000. This study uses a median or

average sales ratio for all properties in each class in each city. The data come primarily

8

from sales ratio studies and sometimes from state equalization studies. Those studies are

performed either by state government agencies or by contractors on behalf of state

agencies and are usually publicly available.

• Exemptions: This study accounts for exemptions that reduce the amount of property value

subject to taxation for the majority of properties in a class for each city. For example, a

$20,000 exemption means a $100,000 home would be taxed as if it were worth $80,000.

• Credits: This study accounts for credits that reduce the tax bill for the majority of

properties in a class for each city. For example, Arkansas has a $350 credit that reduces

the tax bill by $350 for all homesteads in the state. The report also accounts for early

payment discounts that can reduce tax bills in some cities.

With this information, it is possible to calculate typical tax bills in each city for four classes of

property (residential, commercial, industrial, apartments) and several different market values:

Net$Tax$Bill = $

{[(

Market$Value$x$Sales$Ratio

)

− Exemptions

]

$x$Assessment$Ratio$x$Tax$Rate

}

− Credits

First the taxable value is determined, with the market value of the property adjusted using the

sales ratio, then exemptions are subtracted, and then the assessment ratio is applied.

5

Next that

taxable value is multiplied by the total property tax rate, and any credits are subtracted. Finally,

the effective tax rate is calculated by dividing the net tax bill by the market value of the property.

It is important to note that this study provides typical effective tax rates, assuming that the

median or average sales ratio represents a typical value for all properties in each class. In

practice, the accuracy of assessments varies across properties, so some parcels will have higher

effective tax rates than reported in this study and some will have lower tax rates. In addition, this

study does not account for exemptions or credits that are available for a minority of taxpayers in

a city, such as exemptions available solely for seniors or veterans, or tax incentives available to

just some businesses or homeowners.

5

Note that exemptions based on assessed valued are subtracted after the assessment ratio is applied.

9

Why Property Tax Rates Vary Across Cities

This report demonstrates that effective property tax rates vary widely across U.S. cities. This

section explores why some cities have relatively high property tax rates while others have much

lower rates. Statistical analysis shows that four key factors explain more than two-thirds of the

variation in property tax rates. The two most important reasons why tax rates vary across cities

are the extent to which cities rely on the property tax as opposed to other revenue sources, and

the level of property values in each jurisdiction. Two additional factors that help explain

variation in tax rates are the level of local government spending and whether cities tax

homesteads at lower rates than other types of property (referred to as “classification”).

Figure 1: Key Factors Explaining Differences in Property Tax Rates

Appendix 1 shows how these variables affect tax rates on homestead and commercial properties

for each large city included in this report and details the methodology used for this analysis. This

section focuses on homestead property taxes, but our analysis shows that tax rates on business

and apartment properties are driven by the same four key factors.

Property Tax Reliance

One of the main reasons why tax rates vary across cities is that some cities raise most of their

revenue from the property tax, while others rely more on alternative revenue sources.

6

Cities

6

One way to measure the “importance” of each factor is to look at squared semi-partial correlations, which are

analogous to estimating the R-square between the effective tax rate on a median valued home and each factor,

controlling for the effect of the other factors. For the first regression of Appendix Table 1c, 23% of the variation in

effective tax rates is explained by property tax reliance, 32% is explained by median home values, 4% by local

government spending, 7% by the commercial-homestead classification ratio, and 2% by the apartment-homestead

classification ratios.

0.79%

0.48%

-0.63%

-0.40%

-0.33%

-0.80%

-0.60%

-0.40%

-0.20%

0.00%

0.20%

0.40%

0.60%

0.80%

Property Tax

Reliance

Local Gov't

Spending

Percent Change in Effective Tax Rate on Median Valued Home

from 1 Percent Increase in Each Variable

Median

Home Value

Commercial

Classification

Ratio

Apartment

Classification

Ratio

10

with high local sales or income taxes do not need to raise as much revenue from the property tax,

and thus have lower property tax rates on average. Figure 1 shows that a 1 percent increase in the

share of revenue raised by local governments that comes from the property tax is associated with

a 0.79 percent increase in the effective tax rate on a median valued home.

To see how property tax reliance impacts tax rates, compare Bridgeport (CT) and Birmingham

(AL). Bridgeport has the 3

rd

highest effective tax rate on a median valued home in large part

because it has the highest property tax reliance of any large city included in this report. So, while

Bridgeport has high property taxes ($2,128 per capita), city residents pay no local sales or

income taxes. In contrast, Birmingham has the 13

th

lowest effective tax rate on a median valued

home, but also has the fourth lowest reliance on the property tax.

7

As a result, Birmingham

residents have low property taxes ($902 per capita), but also pay a host of other taxes to local

governments, including sales taxes ($1,148 per capita), income taxes ($434 per capita), and other

local taxes ($329 per capita).

8

Consequently, total local taxes are considerably higher in

Birmingham despite the fact that it has much lower property taxes than Bridgeport ($2,995 per

capita vs. $2,155 per capita).

It is important to note that the ability of local governments to tap alternative revenue sources that

would reduce property tax reliance is normally constrained by state law. State governments

usually determine which taxes local governments are authorized to use and set the maximum tax

rate localities are allowed to impose.

9

The data on property tax reliance and local government spending that is used for this analysis is

for fiscally standardized cities (FiSCs) rather than for city municipal governments alone. FiSCs

provide estimates of revenues raised from city residents and businesses and spending on their

behalf, whether done by the city government or by overlying county governments, independent

school districts, or special purpose districts. This approach is similar to the methodology used in

this report, which includes property taxes paid to the city government, county government, and

the largest independent school district in each city. The FiSC database is available on the website

of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

10

Property Values

Home values are the other crucial factor explaining differences in property tax rates. Cities with

high property values can impose a lower tax rate and still raise at least as much property tax

revenue as a city with low property values. For example, Figure 1 shows that a 1 percent increase

in the median home value is associated with a 0.63 percent decrease in the effective tax rate on a

median valued home.

For example, consider San Francisco and Detroit, which have the highest and lowest median

home values in this study – $1,217,500 and $58,900 respectively. After accounting for

assessment limits, the average property tax bill on a median valued home in the 73 large cities in

7

Appendix Table 1a.

8

Data on per capita tax collections in 2017 is from the Lincoln Institute’s Fiscally Standardized Cities database.

9

Michael A. Pagano and Christopher W. Hoene. 2010. “States and the Fiscal Policy Space of Cities.” In The

Property Tax and Local Autonomy, ed. Michael E. Bell, David Brunori, and Joan Youngman, 243-277. Cambridge,

MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

10

https://www.lincolninst.edu/research-data/data-toolkits/fiscally-standardized-cities

11

this report is $3,379. To raise that amount from a median valued home, the effective tax rate

would need to be 20 times higher in Detroit than in San Francisco – 5.74 percent versus 0.28

percent. The effective tax rate on a median valued home is actually just 2.5 times higher in

Detroit than San Francisco (1.77% vs. 0.71%), which means San Francisco collects 8.3 times

more in property taxes from a median valued home ($8,608 vs. $1,041). This is typical – higher

property values usually lead cities to have both lower tax rates and to raise more revenue for

public services. While the difference between San Francisco and Detroit is extreme, it is

common for there to be dramatic differences in property wealth across communities within a

state or region. State government grants to local governments can be used to offset these

differences to help ensure everyone has access to necessary services at affordable property tax

prices regardless of where they live.

This analysis uses the median home value in each city, but no one measure fully captures all

differences in cities’ property wealth. For example, even with identical tax rates on homes and

businesses, cities with larger business tax bases will be able to have lower residential property

tax rates since it usually costs more to provide public services to households than to businesses.

11

In addition, the median does not provide any information about the distribution of home values.

Cities with larger concentrations of high value homes (relative to the median in that city) will be

able to have lower tax rates on a median valued home for any given level of public expenditures.

Local Government Spending

The level of local government spending is another reason why property tax rates vary across

cities, although its effect is considerably less than property tax reliance or home values. Holding

all else equal, cities with higher spending will need to have higher property tax rates. For

example, Figure 1 shows that a 1 percent increase in local government spending per capita is

associated with a 0.48 percent increase in the effective tax rate on a median valued home.

Just as property tax rates are driven by a number of key variables, there are several factors that

influence local government spending. In particular, spending is driven by needs, revenue

capacity, costs, and preferences. For example, expenditure needs are higher in cities with larger

shares of school age children or higher crime rates, because local governments in those cities will

need to spend more on K-12 education and police protection to provide the same quality of

education and public safety as cities with fewer children or lower crime. Spending will often be

higher in cities with greater revenue capacity since cities with larger tax bases can raise more

revenue without needing higher tax rates, as discussed above in the section on property values.

Costs also play a role, because cities with higher costs of living and higher private sector wages

will need to pay higher salaries to attract qualified teachers, police, and other local government

employees. Finally, residents in some cities have a higher preference for public spending – which

also means higher taxes—than in other cities.

12

11

Ernst & Young LLP and Council on State Taxation. 2017. “Total State and Local Business Taxes: State-by-State

Estimates for Fiscal Year 2016.” Pg. 15-18.

12

For an analysis that looks at the factors that drive differences in spending and revenue across states, see

“Assessing Fiscal Capacities of States: A Representative Revenue System-Representative Expenditure System

Approach, Fiscal Year 2012” by Tracy Gordon, Richard C. Auxier, and John Iselin published by the Urban Institute

(March 8, 2016). For an analysis that looks at cities, see “The Fiscal Health of U.S. Cities” by Howard Chernick and

Andrew Reschovsky in Is Your City Healthy? Measuring Urban Fiscal Health published by the Institute on

Municipal Finance and Governance.

12

Classification and Preferential Treatment of Homestead Properties

Classification is the fourth factor that helps to explain differences across cities in property tax

rates on homesteads. Under classified property tax systems, states and cities build preferences

into their tax systems that result in lower effective tax rates for certain classes of property, with

these features usually designed to benefit homeowners.

The “classification ratio” describes these preferences by comparing the effective tax rate for two

types of property. For example, if a city has a 3.0% effective tax rate on commercial properties

and a 1.5% effective tax rate on homestead properties, then the commercial-homestead

classification ratio is 2.0 (3.0% divided by 1.5%). An increase in the classification ratio will be

associated with a decrease in the tax rate on homestead properties, because it means that

homeowners are collectively bearing a smaller share of the property tax burden while businesses

and/or renters pay more. For example, Figure 1 shows that a 1 percent increase in the

commercial-homestead classification ratio is associated with a 0.40 percent decrease in the

effective tax rate on a median valued home, and a 1 percent increase in the apartment-homestead

classification ratio is associated with a 0.33 percent decrease.

Charleston (SC) has the highest classification ratio for apartment buildings relative to

homesteads, and the fifth highest commercial-homestead classification ratio. This means that

commercial buildings and apartments are taxed at a dramatically higher percentage of market

value than owner-occupied residences. In Charleston, a $1 million commercial property and a

$600,000 apartment building both face effective tax rates on their land and buildings that are 3.7

times higher than a median valued home. As a result, while among the largest cities in each state

Charleston has the 19

th

highest tax rate on apartments and the 27

th

highest rate on commercial

properties, it has a much lower tax rate – the 2

nd

lowest tax rate – on a median valued home.

13

Such findings demonstrate that in Charleston, homeowners are heavily subsidized at the expense

of renters and businesses.

The Charleston example shows the other side of the classification equation: favoring

homeowners by definition means higher property taxes on businesses and apartment buildings.

Regression analysis shows that a 1 percent increase in the commercial-homestead classification

ratio is associated with a 0.43 percent increase in the commercial property tax rate, and a 1

percent increase in the apartment-homestead classification ratio is associated with a 0.39 percent

increase in the apartment tax rate.

14

Note that while renters do not pay property tax bills directly, they do pay property taxes

indirectly since landlords are able to pass through some of their property taxes by increasing

rents.

15

Since renters have lower incomes than homeowners on average, preferences given to

homesteads relative to apartment buildings will tend to make the property tax system more

regressive.

13

Appendix tables 2b, 5a, and 3a.

14

Results for commercial properties are shown in Appendix Table 1d. The analysis with effective tax rates on

apartments as the dependent variable uses the same set of explanatory variables; the R-square is similar (0.560) and

each variable has the same level of statistical significance as in Appendix table 1d with the exception that the

coefficient on the apartment-homestead classification ratio is also significant at the 1% level.

15

Bowman, John H., Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin. 2009. “Property Tax Circuit

Breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers.” Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Pg. 32.

13

Other Factors

The four key factors described above explain more than two-thirds of the variation in cities’

effective tax rates on median valued homes and are thus the most important causes of differences

in tax rates across cities. However, there are other factors that also play a role. For example, two

variables that could affect property tax rates are the level of state and federal aid and local

governments’ share of total state and local government spending in each state. However, the

impact of these variables will depend on how exactly the state government structures aid or takes

on service responsibilities otherwise provided by local governments.

It is reasonable to expect that higher state aid will allow local governments to reduce their

reliance on property taxes and thus lead to lower property tax rates. But in fact, research shows

that the impact of state aid on local property taxes is ambiguous and depends on how state aid is

structured. Some state aid formulas can limit local spending, in which case state aid is likely to

reduce property taxes. However, other aid formulas like matching grants can encourage higher

local spending, and thus state aid may not reduce property taxes in those cases.

16

Similarly, if the state government bears a larger share of state and local government

expenditures, it makes sense that local government spending and the need for property taxes

might decline. That would be the case if the state assumes responsibility for public services that

would otherwise be provided by local governments, such as in Hawaii where there is a single

statewide school district and thus no local expenditures on K-12 education. But it is also possible

that state expenditures are higher because the state government spends more on traditional state

responsibilities, like higher education or public welfare, in which case higher state spending

would not lead to lower local government expenditures.

The regression analysis used for this section considered these two other variables, but they were

not found to be related with effective tax rates at a statistically significant level. This finding is

not surprising since the expected impact of these variables depends on institutional details that

are not captured by a single measure of state aid or state expenditures.

16

Kenyon, Daphne A. 2007. The Property Tax-School Funding Dilemma. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of

Land Policy. Page 50.

14

Homestead Property Taxes

Figure 2 shows property taxes on a median valued home for the largest city in each state. The

analysis looks at homesteads, which are owner-occupied primary residences. The average

effective tax rate on median-valued homesteads for the 53 cities in Figure 2 is 1.379 percent. At

that rate, a home worth $200,000 would owe $2,758 in property taxes (1.379% x $200,000).

Tax rates vary widely across the 53 cities. The four cities at the top of the chart – Aurora (IL),

Newark, Bridgeport (CT), and Detroit – have effective tax rates on a median-valued home that

are more than two times higher than the 53-city average. In five other cities, the effective

property tax rate is between 1.5 and 2 times the average. Conversely, the bottom eight cities –

Honolulu, Boston, Charleston (SC), Denver, Charleston (WV), Cheyenne (WY), Birmingham

(AL), and Salt Lake City – all have effective tax rates that are less than half of the study average.

Overall, the average effective tax rate for all cities fell slightly between 2019 and 2020, from

1.395 percent of value to 1.379 percent. The effective tax rate on the median-valued homestead

climbed in 29 cities and fell in 24 cities. The largest increase was in Nashville at nearly 34

percent, which mirrors the increase in the total local mill rate. Even after the increase,

Nashville’s effective tax rate is still 35 percent lower than the 53-city average in 2020, moving

up from 47

th

to 42

nd

place. The next largest increases were five cities that rose more than 5

percent, led by Jackson (MS) at 8 percent, followed by Seattle, Des Moines, Atlanta, and

Newark.

Effective rates on median-valued homes fell the farthest in Buffalo, with a 39 percent decline,

from 1.593 percent to 0.971 percent. After ranking 15

th

in 2019, Buffalo dropped 22 places to

37

th

in 2020. The local mill rates for the school and city – as well as a sewer mill rate – were

slashed by 45 percent from 2019 to 2020. With a slight increase in the county rate, the overall

decrease in mills was 32.5 percent. The next largest decreases were in Charleston (WV) at 29

percent, Columbus (OH) at 13 percent, and Portland (ME) at 9 percent.

17

Columbus and Portland

both ranked relatively high in 2019, so they each dropped just one place to 13

th

and 14

th

place.

Already-low Charleston (WV) dropped from 42

nd

to 49

th

place. Other cities with more than a 7

percent decrease include Salt Lake City (UT), Charleston (SC), Boise (ID), and Denver.

Note that in addition to effective tax rates, Figure 2 also reports the tax bill on a median valued

home for each city. Because of significant variations in home values across these cities, some

cities with modest tax rates can still have high tax bills on a median valued home relative to

other cities, and vice versa. For example, Los Angeles and Wichita have similar tax rates on a

median valued home, but because the median valued home is worth so much more in Los

Angeles ($697k vs. $147k), the tax bill is far higher in Los Angeles (3

rd

highest) than in Wichita

(47

th

highest). In general, cities with high home values can raise considerable property tax

revenue from a median valued home despite modest tax rates, whereas cities with low home

values may have fairly low tax bills even with high tax rates. The table below shows cities with

17

West Virginia performs annual sales ratio studies, and the Kanawha County assessment to sales comparison

dropped from 90% in 2019 to 63.3% in 2020 for improved residential property. The local mill rate actually rose

slightly, so the decrease in effective tax rate is mainly due to the drop in the sales ratio.

15

the largest differences in their ranking in terms of effective tax rates versus tax bills on a median

valued home.

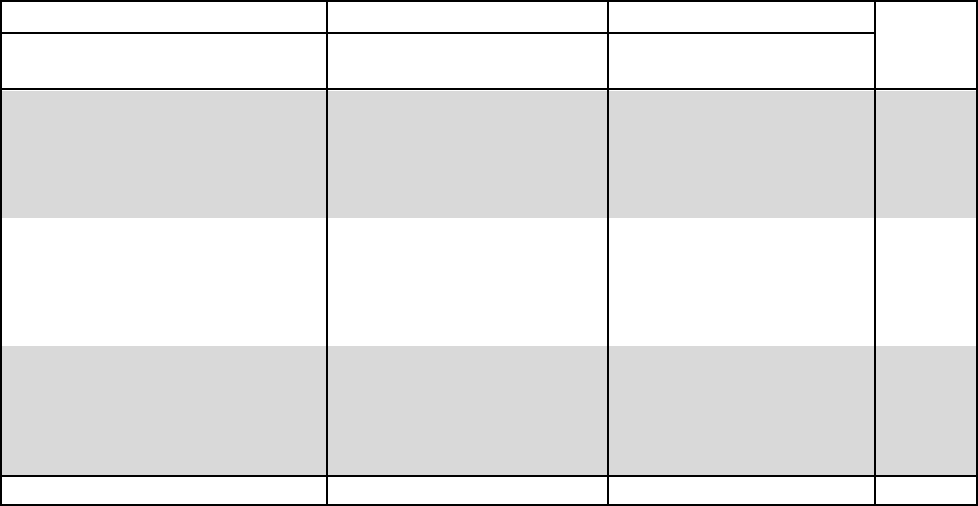

Cities with Largest Differences in Ranking on Effective Tax Rate vs. Tax Bill

for a Median Valued Home (2020)

High Home Values

Cities with high tax bills despite low tax rates

Low Home Values

Cities with low tax bills despite high tax rates

City

Tax Rate

Tax Bill

City

Tax Rate

Tax Bill

Seattle (WA)

43

7

Detroit (MI)

4

48

Washington (DC)

45

11

Jackson (MS)

17

50

Los Angeles (CA)

30

3

Louisville (KY)

24

41

Boston (MA)

51

25

Milwaukee (WI)

6

23

New York (NY)

28

4

Oklahoma City (OK)

25

42

Appendix Table 2b is similar to Table 2a except that it accounts for the effect of assessment

limits, which restrict growth in the assessed value of individual parcels for property tax purposes.

These limits reduce estimates of homestead property taxes for 10 of the 53 cities, with the largest

impacts on New York City, Los Angeles, and Jacksonville (FL). Overall, accounting for

assessment limits reduces the average property tax bill for the 53 cities by 6.5 percent. For more

details on the impact of assessment limits, see that section of this report.

Appendix Table 2c shows how effective tax rates on homestead properties vary based on their

value, showing tax rates for properties worth $150,000 and $300,000 for the largest city in each

state. As the table notes, effective tax rates vary with property value about half of the time (26 of

53 cities). Usually, effective tax rates rise with homestead value because of homestead

exemptions and property tax credits that are set to a fixed dollar amount. Under these programs,

the percentage reduction in property taxes falls as home values rise. For example, a $20,000

exemption provides a 20 percent tax cut on a $100,000 home, a 10 percent cut on a $200,000

home, and a 5 percent cut on a $400,000 home.

18

However, other design elements can create the

same effect. For example, Minnesota uses a tiered assessment system, where 1% of a home’s

market value is taxable up through $500,000 of value, while 1.5% of value above that is taxable.

Value-driven differences in effective tax rates make the biggest difference in Boston, which in

2019 offered a homestead exemption equal to the lesser of $272,707 or 90 percent of a

property’s market value. This results in ultra-low effective tax rates of 0.094% on a $150,000

home and on a $300,000 home, versus 0.48% for a median-valued home ($627,000). Other cities

with the largest differentials in the effective rates between a $150,000-valued and a $300,000-

valued home also offer substantial homestead exemptions: Atlanta (effectively over $100,000 of

market value), Honolulu ($80,000 exemption), New Orleans (effectively $75,000 of market

value), and Washington, DC ($75,700 exemption). Readers should use some caution when

interpreting the results in Appendix Tables 2c, 2f, and 2h; see the box on comparing property

taxes calculated with fixed property values (page 23).

18

For information on homestead exemptions in each state, see “How Do States Spell Relief: A National Study of

Homestead Exemptions and Property Tax Credits” by Adam H. Langley in Land Lines (April 2015).

16

Appendix Tables 2d through 2f show effective tax rates on homestead properties for a different

set of cities. Whereas Tables 2a through 2c focus on the largest city for each state, Tables 2d

through 2f show the 50 largest cities in the country regardless of their state. There is considerable

overlap between the two groups of cities, but some significant differences as well. In this set of

tables, California has eight cities, Texas has seven, Arizona has three, and five states have two

cities each (CO, FL, NC, OK, and TN). There are 21 states without any cities in the top 50. As

with the tables for the largest city in each state, there are two sets of tables for median-valued

homes: one before and one after accounting for the effects of assessment limitations (Tables 2d

and 2e respectively).

This year, the average effective tax rate for median valued homes in the 50 largest cities (Table

2d at 1.402%) exceeds the rate for the largest cities in each state (Table 2a at 1.379%). When

comparing median value homes after accounting for assessment limitations, however, the 50

largest cities drop to 6.3% below the group of largest cities in each state, with an average

effective tax rate of 1.22% (Table 2e) compared to 1.30% (Table 2b). This is because 20 cities of

the 50 largest in the country saw reductions from assessment limits in 2019, and only 10 cities of

the 53 that make up the largest cities in each state did so.

Effective tax rates can be rather homogenous across large cities in a single state. For example,

consider the effective rates on median-valued homes in the two largest states shown in Table 2d:

• In the eight California cities, the highest effective tax rate is Oakland (19

th

highest) and

the lowest is Sacramento (35

th

). California accounts for seven of the 13 cities ranked from

23

rd

to 35

th

, with effective tax rates clustering in the 1.12 to 1.24 percent range due to the

effect of California’s Proposition 13 limitations on tax rates.

• In the seven Texas cities, the highest effective tax rate is El Paso (2

nd

highest) and the

lowest is Houston (13

th

), so Texas accounts for seven of the 12 cities ranked from 2

nd

to

13

th

. It is more difficult to point to a single feature of Texas’ property tax system to

explain this clustering. However, it likely reflects the fact that local governments in these

seven Texas cities have relatively high reliance on property taxes and that Texas has a

uniform property tax system that does not allow for different tax rates or assessment

ratios on different types of property.

However, in other cases there can be considerable differences in effective tax rates between

cities within the same state. For example, Table 2d shows some noticeable differences in

effective tax rates and rankings for median-valued homes between these sets of same-state cities:

• In Tennessee: Memphis has the 15

th

highest tax rate (1.596%), while Nashville has the

44

th

highest (0.895%) – a 29 place differential.

• In Arizona: Phoenix has the 28

th

highest tax rate (1.215%) and Tucson has the 37

th

highest tax rate (1.113%), while Mesa has the 45

th

highest (0.868%) – creating a 17-place

differential between the neighboring cities of Phoenix and Mesa.

Appendix Tables 2g and 2h provide additional information about how effective property tax

rates vary across states by looking at a rural community in each state. The rural analysis includes

county seats with populations between 2,500 and 10,000 located in nonmetropolitan counties.

17

The average effective tax rate on median-valued homes in the 50 rural communities in this report

is 1.278% for taxes paid in 2020, down from 1.330 in 2019. As with large cities, the rates for

rural municipalities vary considerably around that average. In just one municipality – Maurice

River Township (NJ) – the effective tax rate on a median-valued home is 2 times the average. In

contrast, nine municipalities feature effective tax rates of less than half of the average, with the

lowest rates in Kauai (HI), Pocahontas (AR), Georgetown (DE), Monroeville (AL), and

Natchitoches (LA).

Comparing Tables 2a and 2g shows that effective tax rates on median-valued homesteads are

around 8 percent lower in rural municipalities than in large cities on average. There are two

major reasons why rates are lower in rural communities: lower nominal tax rates and homestead

exemptions that apply to a fixed amount of value across the state and therefore exempt higher

proportions of homestead value from taxation in rural areas, where home values are generally

much lower than in large cities.

In 31 states, the effective tax rate on the median-valued home is higher in the largest city

19

than

in the rural municipality. Delaware had the biggest difference in 2020; the 1.068% rate in

Wilmington is 3.9 times the 0.374% rate in Georgetown. Only two other states have a tax rate in

the largest city that is at least two times higher than in the rural community: Arkansas (where

Little Rock is 3.6 times the rate of Pocahontas, and Oregon (where Portland is 2.1 times the rate

of Tillamook).

On the other hand, in 19 states the effective tax rate on median-valued homes is higher in the

rural municipality than in the largest city in the state. The biggest difference is in Massachusetts,

where the effective tax rate in Adams is 4.3 times higher than the rate in Boston (2.079% vs.

0.481%), largely because of Boston’s unique (even within Massachusetts) homestead exemption.

Other states where the tax rate in the rural community is at least 2 times higher than the largest

city are New York (where Warsaw is 2.3 times the rate of Buffalo) and Kansas (where Iola is 2

times the rate of Wichita).

Some readers may want to use findings on effective tax rates from one specific table to reach

conclusions on property taxes throughout an entire state. The small differences in tax rates across

cities in California and Texas (Appendix Tables 2d-2f) show that the largest city in each state

can serve as a proxy for property tax rates throughout an entire state. However, the large

differences between the two largest cities in Tennessee and Arizona show that caution is needed

when extrapolating findings for a single city to an entire state.

Readers wishing to determine whether taxes in a state are high, low, or somewhere in between

are best served by comparing the rankings for urban and rural municipalities

20

. For example, in

six states (Illinois

21

, Michigan, Nebraska, New Jersey, Vermont, and Wisconsin) the effective tax

rate on the median-valued home is among the ten highest in both a rural and an urban setting –

19

Excluding Washington (DC), which has no rural analogue, and Chicago (IL) and New York (NY), which have

property tax systems that differ substantially from those in the remainder of the state. In Illinois and New York, the

differentials are calculated between the rural municipality and the state’s second-largest city.

20

Rankings for large cities are adjusted to 1-50 to compare state systems and exclude Chicago, New York City, and

Washington DC.

21

Aurora only.

18

suggesting that these states are most likely to have the highest homestead property taxes. States

where effective tax rates are among the ten lowest in both rural and urban settings are Alabama,

Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, and West Virginia – suggesting that these states are most likely to have

the lowest homestead property taxes.

19

Figure 2: Property Taxes on Median Valued Home for Largest City in Each State (2020)

0.31%

0.48%

0.48%

0.52%

0.59%

0.64%

0.65%

0.67%

0.73%

0.74%

0.82%

0.89%

0.90%

0.91%

0.93%

0.94%

0.97%

0.98%

1.00%

1.11%

1.12%

1.17%

1.17%

1.19%

1.20%

1.21%

1.21%

1.22%

1.24%

1.24%

1.24%

1.29%

1.29%

1.37%

1.41%

1.44%

1.48%

1.53%

1.54%

1.66%

1.69%

1.73%

1.96%

2.03%

2.22%

2.40%

2.41%

2.41%

2.48%

2.83%

3.00%

3.20%

3.25%

0 1,634 3,268 4,902 6,536 8,170 9,804

0.00% 0.72% 1.45% 2.17% 2.90% 3.62% 4.35%

HI: Honolulu (53, 37)

SC: Charleston (52, 46)

MA: Boston (51, 25)

CO: Denver (50, 36)

WV: Charleston (49, 52)

WY: Cheyenne (48, 49)

UT: Salt Lake City (47, 33)

AL: Birmingham (46, 53)

DC: Washington (45, 11)

ID: Boise (44, 38)

WA: Seattle (43, 7)

TN: Nashville (42, 31)

NC: Charlotte (41, 39)

VA: Virginia Beach (40, 28)

MT: Billings (39, 40)

GA: Atlanta (38, 20)

NY: Buffalo (37, 51)

PA: Philadelphia (36, 45)

LA: New Orleans (35, 34)

AR: Little Rock (34, 43)

NV: Las Vegas (33, 18)

IN: Indianapolis (32, 44)

KS: Wichita (31, 47)

CA: Los Angeles (30, 3)

ND: Fargo (29, 27)

NY: New York City (28, 4)

AZ: Phoenix (27, 22)

NM: Albuquerque (26, 30)

OK: Oklahoma City (25, 42)

KY: Louisville (24, 41)

AK: Anchorage (23, 14)

FL: Jacksonville (22, 29)

RI: Providence (21, 24)

MN: Minneapolis (20, 15)

MO: Kansas City (19, 35)

DE: Wilmington (18, 32)

MS: Jackson (17, 50)

SD: Sioux Falls (16, 21)

IL: Chicago (15, 12)

ME: Portland (14, 9)

OH: Columbus (13, 26)

TX: Houston (12, 19)

NH: Manchester (11, 10)

NE: Omaha (10, 17)

MD: Baltimore (9, 13)

VT: Burlington (8, 6)

IA: Des Moines (7, 16)

WI: Milwaukee (6, 23)

OR: Portland (5, 1)

MI: Detroit (4, 48)

CT: Bridgeport (3, 8)

NJ: Newark (2, 2)

IL: Aurora (1, 5)

Effective Tax Rate Tax Bill

Tax Relative to U.S. Average

1x

($3,470)

1.5x

($5,205)

0.5x

($1,735)

2.5x

($8,675)

2x

($6,940)

(Rate Rank, Bill Rank)

3x

($10,410)

20

Commercial Property Taxes

Figure 3 shows effective property tax rates for commercial properties worth $1 million dollars

for the largest city in each state. This analysis looks specifically at taxes on office buildings and

other commercial properties without inventory on site. Tax rates for other types of commercial

property will often be similar, but will vary in cities where personal property is taxed differently

than real property. The analysis assumes each property has an additional $200,000 worth of

fixtures, which includes items such as office furniture, equipment, display racks, and tools.

Different types of commercial property will have different proportions of real and personal

property. Therefore, effective tax rates will change between different types of commercial

property in cities where personal property is taxed differently from real property.

22

The average effective tax rate on commercial properties for the 53 cities in Figure 3 is 1.953

percent. A property worth $1 million with $200,000 in fixtures would thus owe $23,436 in

property taxes (1.953% x $1.2m).

Tax rates vary widely across the 53 cities. Detroit and Chicago both had effective tax rates that

were 2.1 times the average. Bridgeport (CT), Providence, and Des Moines were close behind at

1.9, 1.9, and 1.8 times the average. On the other hand, Cheyenne (WY), Seattle, and Charlotte

(NC) have tax rates that are less than half of the average, and a larger group of cities are between

0.53 and 0.56 of the average, including Boise, Virginia Beach, Honolulu, Fargo, and Billings

(MT).

Wilmington (DE) had the largest increase at 41 percent, with an effective tax rate change from

1.062 percent in 2019 to 1.501 percent in 2020, moving them up from 47

th

to 32

nd

place.

23

The

change returns Wilmington close to their 2018 ranking of 35

th

place. Nashville’s rate increased

by 34 percent, mirroring the increase in local mill rates, raising their ranking from 48

th

to 37

th

place. Other double-digit increases were found in Chicago (15.5 percent), Sioux Falls and Des

Moines at 13.5 percent, Bridgeport (CT) at 11.5 percent, and Detroit (10 percent).

The largest rate decrease was found in Buffalo (NY), where a 38 percent decrease produced a

drop in ranking from 19

th

to 41

st

place. As was the case with homesteads, local mill rates were

slashed for non-homestead property, although non-homestead properties do continue to have

higher mill rates overall. The only other double-digit decrease was Boise at 13.5 percent, which

was achieved by cutting the local mill rate by 12.4%, and. In addition, Philadelphia, Salt Lake

City, Denver, and Portland (ME) all had decreases of more than 5 percent.

Appendix Table 3a shows how effective tax rates on commercial properties vary based on their

value, showing tax rates for properties worth $100,000, $1 million, and $25 million (all have

22

For an analysis that looks at how effective tax rates vary between different types of commercial property, see “The

Effects of State Personal Property Taxation on Effective Tax Rates for Commercial Property” by Aaron Twait,

published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (April 2018). The paper finds that average effective tax rates for

payable 2016 exceeded 1.9% for hospitals, restaurants, and office space while wholesale trade facilities encountered

rates roughly half as large. The paper also finds the current study assumptions realistically model the property taxes

payable on the most common type of commercial property – office property.

23

Wilmington did have a 9% increase in local mill rates, but the change is mainly due to the sales ratio increasing

from 25.9% in 2019 to 33.6% in 2020, which puts the 2020 sales ratio close where it was in 2018 (35.0%).

21

fixtures worth 20% of the real property value). Effective tax rates for commercial properties

generally do not vary based on property values, unlike homestead properties, where exemptions

or other tax relief programs often create significantly lower rates on lower valued properties.

Only 12 of the 53 cities have effective tax rates that vary based on their value. Value-driven

differences in effective tax rates make the biggest difference in rankings in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia has among the lowest tax rates for commercial properties worth $100,000 (1.089%,

45

th

highest), but is above average for commercial properties worth $25 million (2.024%, 22

nd

highest). The city offers property owners a credit against the first $2,000 of Business Use and

Occupancy Tax (effectively, a property tax imposed only on business properties) assessed

against individual properties, and this credit creates this large differential. The credit reduces the

tax on a $100,000-valued property by 46%, but by only 0.3% for a property worth $25 million.

Other cities where the rankings vary significantly because of beneficial tax treatment provided to

lower-valued properties through credits, exemptions, or preferential assessment practices

include:

• Minneapolis (26

th

highest for $100k, 7

th

highest for $25m)

• Washington, DC (41

st

highest for $100k, 23

rd

highest for $25m)

• Anchorage (40

th

highest for $100k, 32

nd

highest for $25m)