1

REPORTABLE

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION

Writ Petition (Civil) No.528 of 2018

INTERNET AND MOBILE ASSOCIATION

OF INDIA …. Petitioner

Versus

RESERVE BANK OF INDIA ... Respondent

WITH

Writ Petition (Civil) No.373 of 2018

J U D G M E N T

V. Ramasubramanian, J.

1. THE STORY LINE:

1.1. Reserve Bank of India (hereinafter, “RBI”) issued a

“Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies” on April

5, 2018, paragraph 13 of which directed the entities regulated by RBI

(i) not to deal with or provide services to any individual or business

entities dealing with or settling virtual currencies and (ii) to exit the

relationship, if they already have one, with such individuals/

business entities, dealing with or settling virtual currencies (VCs).

Digitally signed by

SUSHMA KUMARI

BAJAJ

Date: 2020.03.04

13:32:29 IST

Reason:

Signature Not Verified

2

1.2. Following the said Statement, RBI also issued a circular

dated April 6, 2018, in exercise of the powers conferred by Section

35A read with Section 36(1)(a) and Section 56 of the Banking

Regulation Act, 1949 and Section 45JA and 45L of the Reserve Bank

of India Act, 1934 (hereinafter, “RBI Act, 1934”) and Section 10(2)

read with Section 18 of the Payment and Settlement Systems Act,

2007, directing the entities regulated by RBI (i) not to deal in virtual

currencies nor to provide services for facilitating any person or entity

in dealing with or settling virtual currencies and (ii) to exit the

relationship with such persons or entities, if they were already

providing such services to them.

1.3. Challenging the said Statement and Circular and seeking a

direction to the respondents not to restrict or restrain banks and

financial institutions regulated by RBI, from providing access to the

banking services, to those engaged in transactions in crypto assets,

the petitioners have come up with these writ petitions. The petitioner

in the first writ petition is a specialized industry body known as

‘Internet and Mobile Association of India’ which represents the

interests of online and digital services industry. The petitioners in the

second writ petition comprise of a few companies which run online

crypto assets exchange platforms, the shareholders/founders of these

companies and a few individual crypto assets traders. It must be

stated here that the individuals who are some of the petitioners in the

3

second writ petition are young high-tech entrepreneurs who have

graduated from premier educational institutions of technology in the

country.

Contents of the impugned Statement and Circular of RBI:

1.4. The Statement dated 05-04-2018 issued by RBI, impugned

in these writ petitions, sets out various developmental and regulatory

policy measures for the purpose of (i) strengthening regulation and

supervision (ii) broadening and deepening financial markets (iii)

improving currency management (iv) promoting financial inclusion

and literacy and (v) facilitating data management. Paragraph 13 of the

said statement which falls under the caption “currency

management” deals directly with virtual currencies and the same

constitutes the offending portion of the impugned Statement.

Therefore, paragraph 13 of the impugned Statement alone is

extracted as follows:

13. Ring-fencing regulated entities from virtual

currencies

Technological innovations, including those underlying

virtual currencies, have the potential to improve the

efficiency and inclusiveness of the financial system.

However, Virtual Currencies (VCs), also variously referred

to as crypto currencies and crypto assets, raise concerns of

consumer protection, market integrity and money

laundering, among others.

Reserve Bank has repeatedly cautioned users, holders

and traders of virtual currencies, including Bitcoins,

regarding various risks associated in dealing with such

4

virtual currencies. In view of the associated risks, it has

been decided that, with immediate effect, entities

regulated by RBI shall not deal with or provide services to

any individual or business entities dealing with or settling

VCs. Regulated entities which already provide such

services shall exit the relationship within a specified time.

A circular in this regard is being issued separately.

1.5. The Circular dated 06-04-2018 deals entirely with virtual

currencies and the prohibition on dealing with the same. This

Circular is statutory in character, issued in exercise of the powers

conferred by (i) the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 (ii) the Banking

Regulation Act, 1949 and (iii) the Payment Settlement Systems Act,

2007. This Circular in its entirety is reproduced as follows:

Prohibition on dealing in Virtual Currencies (VCs)

Reserve Bank has repeatedly through its public notices on

December 24, 2013, February 01, 2017 and December 05,

2017, cautioned users, holders and traders of virtual

currencies, including Bitcoins, regarding various risks

associated in dealing with such virtual currencies.

2. In view of the associated risks, it has been decided that,

with immediate effect, entities regulated by the Reserve

Bank shall not deal in VCs or provide services for

facilitating any person or entity in dealing with or settling

VCs. Such services include maintaining accounts,

registering, trading, settling, clearing, giving loans against

virtual tokens, accepting them as collateral, opening

accounts of exchanges dealing with them and

transfer/receipt of money in accounts relating to

purchase/sale of VCs.

3. Regulated entities which already provide such services

shall exit the relationship within three months from the

date of this circular.

4. These instructions are issued in exercise of powers

conferred by section 35A read with section 36(1)(a) of

5

Banking Regulation Act, 1949, section 35A read with

section 36(1)(a) and section 56 of the Banking Regulation

Act, 1949, section 45JA and 45L of the Reserve Bank of

India Act, 1934 and Section 10(2) read with Section 18 of

Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007.

2. THE SETTING

2.1. The Statement dated 05-04-2018 and the Circular dated

06-04-2018 of RBI, impugned in these writ petitions, were a

culmination of a flurry of activities by different stakeholders,

nationally and globally, over a period of about 5 years. Therefore, it is

necessary to see the setting in which (or the backdrop against which)

the impugned decisions of RBI were posited. While doing so, it will

also be necessary to take note of the developments that have taken

place during the pendency of these writ petitions, so that we have a

close-up as well as aerial view of the setting.

2.2. It was probably for the first time that RBI took note of

technology risks in changing business environment, in their Financial

Stability Report of June 2013. Paragraph 3.60 of this report noted

that globally, the use of online and mobile technologies was driving

the proliferation of virtual currencies. Therefore, the report stated that

those developments pose challenges in the form of regulatory, legal

and operational risks. Box 3.4 of the said report dealt specifically with

virtual currency schemes and it started by defining virtual

currency as a type of unregulated digital money, issued and

6

controlled by its developers and used and accepted by the

members of a specific virtual community. It was declared in Box

3.4 of the said report that “the regulators are studying the impact of

online payment options and virtual currencies to determine potential

risks associated with them”.

2.3. In June 2013, the Financial Action Task Force (hereinafter,

“FATF”), also known by its French name, Groupe d'action financière,

which is an inter-governmental organization founded in 1989 on the

initiative of G-7 to develop policies to combat money laundering, came

up with what came to be known as “New Payment Products and

Services Guidance” (NPPS Guidance, 2013). It was actually a

Guidance for a Risk Based Approach to Pre-paid cards, Mobile

Payments and Internet-based Payment Services. But this Guidance

did not define the expressions ‘digital currency’, ‘virtual currency’, or

‘electronic money’, nor did it focus on virtual currencies, as distinct

from internet based payment systems that facilitate transactions

denominated in real money (such as Paypal, Alipay, Google Checkout

etc.). Therefore, a short-term typologies project was initiated by FATF

for promoting fuller understanding of the parties involved in

convertible virtual currency systems and for developing a risk matrix.

2.4. On 24-12-2013, a Press Release was issued by RBI

cautioning the users, holders and traders of virtual currencies about

the potential financial, operational, legal and customer protection and

7

security related risks that they are exposing themselves to. The Press

Release noted that the creation, trading or usage of VCs, as a medium

of payment is not authorized by any central bank or monetary

authority and hence may pose several risks narrated in the Press

Release.

2.5. On 27-12-2013, newspapers reported the first ever raid in

India by the Enforcement Directorate, of 2 Bitcoin trading firms in

Ahmedabad, by name, rBitco.in and buysellbitco.in. This was stated to

be India's first raid on a Bitcoin trading firm and the second globally,

after Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States of America

conducted a raid in October of the same year.

2.6. Thereafter, a report titled “Virtual Currencies – Key

Definitions and Potential AML/CFT Risks” was issued in June 2014

by FATF, highlighting, both legitimate uses and potential risks

associated with virtual currencies. What is of great significance about

this FATF report is that it defined 2 important words. The FATF

report defined ‘Virtual currency’ as a digital representation of

value that can be traded digitally and functioning as (1) a

medium of exchange; and/or (2) a unit of account; and/or (3) a

store of value, but not having a legal tender status. The FATF

report also defined ‘Cryptocurrency’ to mean a math-based,

decentralised convertible virtual currency protected by

cryptography by relying on public and private keys to transfer

8

value from one person to another and signed cryptographically

each time it is transferred.

2.7. Again, in June 2015, FATF came up with a “Guidance for a

Risk Based Approach to Virtual Currencies”, which suggested certain

recommendations, as follows:

A. Countries to identify, assess and understand risks and to take

action aimed at mitigating such risks. National authorities to

undertake a coordinated risk assessment of VC products and services

that:

(1) enables all relevant authorities to understand how specific

virtual currency products and services function and impact

regulatory jurisdictions for Anti Money Laundering (‘AML’ for

short)/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (‘CFT’ for short)

treatment purposes;

(2) promote similar AML/CFT treatment for similar products and

services having same risk profiles.

B. Where countries are prohibiting virtual currency products and

services, they should take into account among other things, the

impact a prohibition would have on local and global level of money

laundering/terrorism financing risks, including whether prohibition

would drive such payment activities underground, where they will

operate without AML/CFT controls.

9

2.8. The FATF submitted a report in October 2015 on

“Emerging Terrorist Financing Risks”. The report was divided into

four parts, under the captions (i) introduction (ii) financial

management of terrorist organisations (iii) traditional terrorist

financing methods and techniques and (iv) emerging terrorist

financing threats and vulnerabilities. Even while acknowledging in

part 3 of the report that the traditional methods of moving funds

through the banking sector happens to be the most efficient way of

movement of funds for terrorist organisations, the report

acknowledged the emergence of new payment products and services

in part 4 of the report. The report took note of different methods of

terrorist financing, such as self-funding, crowd funding, social

network fund raising with prepaid cards etc. Coming to virtual

currencies, the report noted the following:

“Virtual currencies have emerged and attracted investment

in payment infrastructure built on their software protocols.

These payment mechanisms seek to provide a new method

for transmitting value over the internet. At the same time,

virtual currency payment products and services (VCPPS)

present ML/TF risks. The FATF made a preliminary

assessment of these ML/TF risks in the report Virtual

Currencies Key Definitions and Potential AML/CFT Risks.

As part of a staged approach, the FATF has also developed

Guidance focusing on the points of intersection that provide

gateways to the regulated financial system, in particular

convertible virtual currency exchangers.

Virtual currencies such as bitcoin, while representing a

great opportunity for financial innovation, have attracted

the attention of various criminal groups, and may pose a

10

risk for TF (terrorist financing). This technology allows

for anonymous transfer of funds internationally.

While the original purchase of the currency may be

visible (e.g., through the banking system), all

following transfers of the virtual currency are

difficult to detect. The US Secret Service has observed

that criminals are looking for and finding virtual currencies

that offer: anonymity for both users and transactions; the

ability to move illicit proceeds from one country to another

quickly; low volatility, which results in lower exchange

risk; widespread adoption in the criminal underground;

and reliability.

Law enforcement agencies are also concerned about the

use of virtual currencies (VC) by terrorist organisations.

They have seen the use of websites affiliated with terrorist

organisations to promote the collection of bitcoin donations.

In addition, law enforcement has identified internet

discussions among extremists regarding the use of VC to

purchase arms and education of less technical extremists

on use of VC. For example, a posting on a blog linked to

ISIL proposed using bitcoin to fund global extremist

efforts.” (emphasis supplied)

In support of the above conclusions, the report also indicated a case

study, which concerned the arrest of one Ali Shukri Ameen, who

admitted to have had a Twitter account with 4000 followers. He

claimed to have used his Twitter handle to provide instructions on

how to use a virtual currency to mask the provision of funds to ISIL.

In an article, the link to which he tweeted to his followers, it was

elaborated how jihadists could utilize the virtual currency to fund

their efforts. (It must be noted that the report also took note of how

prepaid cards and other internet-based payment services could also

be used for terror financing).

11

2.9. The Bank of International Settlements (hereinafter, “BIS”)

which is a body corporate established under the laws of Switzerland,

way back in the year 1930 pursuant to an agreement signed at

Hague on 22-01-1930 and owned by 60 Central Banks of different

countries including RBI, has several committees, one of which is

“Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructure” (CPMI). This

committee started taking note of digital currencies, while dealing with

innovations in retail payments. This committee formed a sub-group

within the CPMI Working Group on Retail Payments, to undertake an

analysis of digital currencies. On the basis of the findings of the sub-

group, CPMI of BIS submitted a report in November 2015 on Digital

currencies. The sub-group identified three key aspects relating

to the development of digital currencies one of which was that

the assets featured in digital currency schemes, typically have

some monetary characteristics such as being used as a means

of payment, but are not backed by any authority. In Note 1 under

the Executive Summary of the said report, it was stated as follows:

“although digital currencies typically do have some, but not all

the characteristics of a currency, they may also have

characteristics of a commodity or other asset. Their legal

treatment can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.” (emphasis

supplied) Paragraph 4 of the said report dealt with the “implications

for central banks, of digital currencies and their underlying

12

decentralized payment mechanisms”. In the said paragraph, the

report indicated that “digital currencies represent a technology for

settling peer to peer payments without trusted third parties and may

involve a non-sovereign currency”. Though the report stated that the

impact of digital currencies on the mainstream financial

system is negligible as at that time, some of the implications

indicated in the report may actually materialize if there was

widespread adoption of digital currencies. Two risks were noted

in the report and they were consumer protection and operational

risks. But in so far as distributed ledger technology is concerned, the

report was positive. However, the report cautioned that a

widespread substitution of bank notes with digital currencies

could lead to a decline in central banks’ non-interest paying

liabilities and that if the adoption and use of digital currencies

were to increase significantly, the demand for existing

monetary aggregates and the conduct of monetary policy could

be affected. Nevertheless, the report stated that at present, the use

of private digital currencies is too low for these risks to materialize.

2.10. In December 2015, the Financial Stability Report of RBI

was issued, and it included a chapter on “Financial Sector

Regulation”. The same dealt with the challenges posed by technology-

based innovations such as virtual currency schemes. In Box 3.1 of

the said report, it was indicated that though the initial concerns

13

over the emergence of virtual currency schemes were about the

underlying design, episodes of excessive volatility in their value

and their anonymous nature which goes against global money

laundering rules rendered their very existence questionable.

However, the report noted that the regulators and authorities need to

keep pace with developments, as many of the world’s largest banks

started supporting a joint effort for setting up of private blockchain

and building an industry-wide platform for standardizing the use of

technology.

2.11. In December 2016, the Financial Stability Report of RBI

came. It took note of the rapid developments taking place in Fin Tech

(financial technology) globally and exhorted the regulators to gear up

to adopt technology (christened as RegTech). Paragraph 3.22 of the

said report identified the establishment of regulatory sandboxes

1

and

innovation hubs for testing new products and services and providing

support/guidance to regulated as well as unregulated entities. The

report also noted that fast paced innovations such as virtual

currencies have brought risks and concerns about data security and

consumer protection on one hand and far reaching potential impact

on the effectiveness of monetary policy itself on the other hand. The

report took note of the fact that many central banks around the

1

Regulatory sandbox refers to live testing of new products/services in a controlled/test

regulatory environment.

14

world, had already started examining the feasibility of creating their

own digital currencies, after fretting over them initially.

2.12. In January 2017, the Institute for Development and

Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT) established by RBI in 1996

as an institution to work at the intersection of banking and

technology submitted a Whitepaper on “Applications of blockchain

technology to banking and financial sector in India”. While dealing

with the applications of blockchain technology in chapter 3, the

whitepaper also enlisted the advantages and disadvantages of digital

currency. While the advantages indicated were (i) control and

security, (ii) transparency and (iii) very low transaction cost, the

disadvantages indicated were risk and volatility.

2.13. On 01-02-2017, RBI again issued a Press Release

cautioning users, holders and traders of virtual currencies. Closely

on the heels of this Press Release, the Government of India, Ministry

of Finance, constituted, in April 2017, an Inter-Disciplinary

Committee comprising of the Special Secretary (Economic Affairs)

and representatives of the Departments of Economic Affairs,

Financial Services, Revenue, Home Affairs, Electronics and

Information Technology, RBI, NITI Aayog, and State Bank of India.

The task of the Committee was to (i) take stock of the status of VCs in

India and globally, (ii) examine the existing global regulatory and

legal structures and (iii) suggest measures for dealing with VCs. The

15

Committee was mandated to submit a report within 3 months.

2.14. The report of the Inter-Disciplinary Committee was

submitted on 25-07-2017 and it contained certain recommendations

which are as follows:

(i) A very visible and clear warning should be issued

through public media informing the general public that

the Government does not consider crypto-currencies

such as bitcoins as either coins or currencies. These are

neither a legally valid medium of exchange nor a desirable

way to store value. The Government also does not consider it

desirable for people to use or invest in something which has

no real underlying asset value.

(ii) A very visible and clear warning should be issued,

through public media, advising all those who have been

offering to buy or sell these currencies, or offering a

platform to exchange these currencies, to stop this

forthwith.

(iii) Those who have bought these currencies in good

faith and are holding these should be advised to offload

these in any jurisdiction where it is not illegal to do so.

(iv) All consumer protection and enforcement agencies

should be advised to take action against all those who,

despite these warnings, indulge in buying/selling or offering

platform for trading of these currencies, since the presumption

would be that it is being done with illegal, fraudulent or tax

evading intent.

(v) If the Government agrees with the above

recommendations, a committee should be constituted

with members from DEA, RBI, SEBI, DoR, DoLA, Consumer

Affairs, and MeitY, to suggest whether any further actions,

including legislative changes, are required to make

possession, trade and use of crypto-currencies expressly

illegal and punishable.

16

(vi) Finally, it is clarified that none of the above

recommendations are meant to restrict the use of

blockchain technology for purposes other than that of

creating or trading in crypto-currencies.

2.15. In August 2017, Securities and Exchange Board of India

(SEBI) established a 10-member advisory panel to examine global

fintech developments and report on opportunities for the Indian

securities market. The goal of the new Committee on Financial and

Regulatory Technologies was to help prepare India to adopt fintech

solutions and foster innovations within the country.

2.16. On 02-11-2017, the Government of India constituted a

committee chaired by the Secretary (Department of Economic Affairs)

and comprising of Secretary, Ministry of Electronic and Information

Technology, Chairman, SEBI and Deputy Governor, RBI (Inter-

Ministerial Committee) to propose specific actions to be taken in

relation to VCs.

2.17. At that stage, two persons, by name, Siddharth Dalmia

and Vijay Pal Dalmia came up with a writ petition in WP (C) No.1071

of 2017 under Article 32 of the Constitution of India seeking the

issue of a writ of mandamus directing the respondents to declare as

illegal and ban all virtual currencies as well as ban all websites and

mobile applications which facilitate the dealing in virtual currencies.

Similarly, another person, by name, Dwaipayan Bhowmick came up

with a writ petition in WP (C) No.1076 of 2017, seeking the issue of a

17

writ of mandamus directing the respondents to regulate the flow of

Bitcoin (crypto money) and to constitute a committee of experts to

consider the prohibition/regulation of Bitcoin and other crypto

currencies. On 13.11.2017, this Court ordered notice in both the writ

petitions.

2.18. Around the same time, namely, November 2017, the Inter-

Regulatory Working Group on Fintech and Digital Banking, set up by

RBI, pursuant to a decision taken by the Financial Stability and

Development Council Sub-Committee way back in April 2016,

submitted a report. This report, in paragraph 2.1.3.2, dealt with

Digital Currencies. It defined ‘digital currencies’ to mean digital

representations of value, issued by private developers and

denominated in their own unit of account. The Report also stated

that “digital currencies are not necessarily attached to a fiat

currency, but are accepted by natural or legal persons as a

means of exchange.”

2.19. Thereafter, RBI issued another Press Release dated 05-

12-2017 reiterating the concerns expressed in earlier press releases.

The Government of India, Ministry of Finance also issued a statement

on 29-12-2017 cautioning the users, holders and traders of VCs that

they are not recognized as legal tender and that the investors should

avoid participating in them.

18

2.20. On 01-02-2018, the Minister of Finance, in his budget

speech said that the Government did not consider crypto currencies

as legal tender or coin and that all measures to eliminate the use of

these currencies in financing illegitimate activities or as part of the

payment system, will be taken by the Government. However, he also

said that the Government will explore the use of blockchain

technology proactively for ushering in digital economy.

2.21. The Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), by an Office

Memorandum dated 05-03-2018, submitted to the Department of

Economic Affairs, a draft scheme proposing a ban on

cryptocurrencies. But the draft scheme advocated a step-by-step

approach, as many persons had already invested in cryptocurrencies.

The scheme also contained an advice to carry out legislative

amendments before banning them.

2.22. In the wake of a meeting of G-20 Finance Ministers and

Central Bank Governors that was scheduled to be held in mid-March

2018, the Financial Stability Board

2

(FSB) sent out a communication

dated 13-03-2018. It was indicated in the said communication that

as per the initial assessment of FSB, crypto assets did not pose risks

to global financial stability, as their combined global market value

even at their peak, was less than 1% of global GDP. But the report

also noted that the initial assessment was likely to change and that

2

FSB was established by G-20 in April 2009, as a successor to the Financial Stability

Forum founded in 1999 by G-7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors.

19

crypto assets raised a host of issues around consumer and investor

protection as well as their use to shield illicit activity and for money

laundering and terrorist financing.

2.23. The communique issued by G-20, after the meeting of its

Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors on March 19-20,

2018 also acknowledged that technological innovation including

that underlying crypto assets, has the potential to improve the

efficiency and inclusiveness of the financial system and the

economy more broadly. But it also noted that crypto assets do

raise issues with respect to consumer and investor protection,

market integrity, tax evasion, money laundering and terrorist

financing. Though crypto assets lacked the key attributes of

sovereign currencies, they could, at some point, have financial

stability implications. Therefore, the communique resolved to

implement FATF standards and to call on international standard-

setting bodies to continue their monitoring of crypto assets and their

risks.

2.24. On 02-04-2018, RBI sent an e-mail to the Government,

enclosing a note on regulating crypto assets. It was with reference to

the record of discussions of the last meeting of the Inter-Ministerial

Committee on virtual currency. This note examined the pros and

cons of banning and regulating cryptocurrencies and suggested that

it had to be done, backed by suitable legal provisions.

20

2.25. Immediately thereafter, the Statement dated 05-04-2018

and the Circular dated 06-04-2018, impugned in these writ petitions

came to be issued by RBI. It appears that at around the same time

(April 2018), the Inter-Ministerial Committee submitted its initial

report, (or a precursor to the report) along with a draft bill known as

Crypto Token and Crypto Asset (Banning, Control and

Regulation) Bill, 2018.

3

2.26. But in the meantime, a few companies which run online

crypto assets exchange platforms together with the shareholders/

founders of those companies and a few individual crypto assets

traders came up with the first of the writ petitions on hand, namely

WP (C) No. 373 of 2018, challenging the aforesaid Statement dated

05-04-2018 and Circular dated 06-04-2018. On 01-05-2018 this writ

petition was directed to be tagged along with the writ petitions WP (C)

Nos. 1071 and 1076 of 2017 which sought a ban on or regulation of

cryptocurrencies.

2.27. On 11-05-2018, all the three writ petitions, namely WP (C)

Nos. 1071 and 1076 of 2017 and 373 of 2018, came up for hearing.

At that time, it was pointed out that a few High Courts were also

seized of writ petitions concerning cryptocurrencies. Therefore, this

Court gave liberty to RBI to move appropriate applications for

3

The fate of the 2018 Bill is not known but a fresh bill called ‘Banning of

Cryptocurrency and Regulation of Official Digital Currency Bill, 2019’ has been

submitted.

21

transfer of all those cases to this Court.

2.28. Accordingly, RBI came up with transfer petitions and the

transfer petitions were taken on Board on 17-05-2018 and a

direction was issued that no High Court shall entertain any writ

petition relating to the impugned Circular dated 06-04-2018. This

Court also passed an interim order on 17-05-2018 permitting the

petitioners in WP (C) No. 1071 of 2017 to submit a representation to

RBI with a further direction to RBI to deal with the same in

accordance with law.

2.29. In the meantime, the Internet and Mobile Association of

India came up with the second of the writ petitions on hand, namely

WP (C) No. 528 of 2018 and notice was ordered in the said writ

petition on 03-07-2018. While doing so, this Court issued a direction

to RBI to dispose of the representation, if any, already submitted by

the Association. Accordingly, RBI considered the representation and

issued two communications dated 06-07-2018 and 09-07-2018.

2.30. On 23-07-2018, SEBI sent its comments on the 2018 Bill,

to the Department of Economic Affairs. Their primary objection to the

Bill was that they are not best suited to be the regulators of crypto

assets and tokens.

2.31. Next came the Annual Report of RBI for the year 2017-

2018. It contained a separate Box II.3.2 on “Cryptocurrency: Evolving

challenges”. The relevant portion of the same reads as follows:

22

“Though cryptocurrency may not currently pose systemic

risks, its increasing popularity leading to price bubbles

raises serious concerns for consumer and investor

protection, and market integrity. Notably, Bitcoins lost

nearly US$200 billion in market capitalisation in about two

months from the peak value in December 2017. As per the

CoinMarketCap, the overall cryptocurrency market had

nearly touched US$800 billion in January 2018.

The cryptocurrency eco-system may affect the

existing payment and settlement system which

could, in turn, influence the transmission of

monetary policy. Furthermore, being stored in

digital/electronic media – electronic wallets – it is prone to

hacking and operational risks, a few instances of which

have already been observed globally. There is no

established framework for recourse to customer

problems/disputes resolution as payments by

cryptocurrencies take place on a peer-to-peer basis without

an authorised central agency which regulates such

payments. There exists a high possibility of its usage for

illicit activities, including tax avoidance. The absence of

information on counterparties in such peer-to-peer

anonymous/ pseudonymous systems could subject users

to unintentional breaches of anti-money laundering laws

(AML) as well as laws for combating the financing of

terrorism (CFT) (Committee on Payments and Market

Infrastructures – CPMI, 2015). The Bank for

International Settlements (BIS) has recently warned

that the emergence of cryptocurrencies has become a

combination of a bubble, a Ponzi scheme and an

environmental disaster, and calls for policy

responses (BIS, 2018). The Financial Action Task Force

(FATF) has also observed that cryptoassets are being used

for money laundering and terrorist financing. A globally

coordinated approach is necessary to prevent abuses and

to strictly limit interconnections with regulated financial

institutions.

On a global level, regulatory responses to cryptocurrency

have ranged from a complete clamp down in some

jurisdictions to a comparatively ‘light touch regulatory

approach’. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

23

and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC)

have emerged as the primary regulators of

cryptocurrencies in the United States, where these assets

like most other jurisdictions, do not enjoy the legal tender

status. Asian countries have experienced oversized

concentration of crypto players – Japan and South Korea

account for the biggest shares of crypto asset markets in

the world. In the case of Bitcoins, half of transactions

worldwide are carried out in Japan. In September 2017,

Japan approved transactions by its exchanges in

cryptocurrencies. China’s exchanges hosted a

disproportionately large volumes of global Bitcoin trading

until their ban recently. […]

Developments on this front need to be monitored as some

trading may shift from exchanges to peer-to-peer mode,

which may also involve increased usage of cash.

Possibilities of migration of crypto exchange houses to dark

pools/cash and to offshore locations, thus raising concerns

on AML/CFT and taxation issues, require close watch.”

(emphasis supplied)

2.32. In this background, all the four writ petitions namely WP

(C) Nos. 1071 and 1076 of 2017 (seeking a ban) and WP (C) Nos. 373

and 528 of 2018 (challenging the indirect ban) came up for hearing,

along with the transfer petitions, on 25-10-2018, when this Court

was informed that the Union of India had already constituted a

committee and that this Inter-Ministerial Committee was deliberating

on the issue. Therefore, the writ petitions were adjourned to enable

the Committee to come up with their recommendations.

2.33. It appears that the Committee so constituted, submitted a

report on 28-02-2019 indicating the action to be taken in relation to

virtual currencies. A bill known as “Banning of Cryptocurrency and

24

Regulation of Official Digital Currency Bill, 2019” had also been

prepared by then to be introduced in the Lok Sabha. To this report of

the Committee, is appended, the minutes of the discussions of the

Committee in the meetings held on 27-11-2017, 22-02-2018, and 09-

01-2019. The contents of the report of the Inter-Ministerial

Committee dated 28-02-2019, can be well understood only if we look

at the Record of Discussions of the meetings of the Committee. The

Record of Discussions held on 27-11-2017 shows that the Inter-

Ministerial Committee was of the initial view that the banning

option was difficult to implement and that it can also drive

some operators underground, encouraging the use of such

currencies for illegitimate purposes. But it was generally agreed in

the said meeting that VCs cannot be treated as currency. However, in

the meeting held on 22-02-2018, the Deputy Governor, RBI made

an initial intervention and argued in favour of using the

banning option. Eventually, the other members of the Committee

agreed, and it was resolved in the said meeting that a detailed paper

on the option of banning VCs, including a draft law could be

prepared and submitted by RBI and CBDT. It was also resolved to

prepare a detailed paper within Department of Economic Affairs on

options of regulating crypto assets. Following the same, it was

resolved in the next meeting held on 09-01-2019 that a Standing

Committee should be constituted to revisit certain issues. Eventually,

25

the Inter-Ministerial Committee submitted the aforesaid report dated

28-02-2019. The key aspects of this report are:

i. Virtual currency is a digital representation of value that can

be digitally traded and it can function as a medium of exchange

and/or a unit of account and/or a store of value, though it does not

have the status of a legal tender.

ii. Initial Coin Offerings (hereinafter, “ICO”) are a way for

companies to raise money by issuing digital tokens in exchange for

fiat currency or cryptocurrency, but there is a clear risk with the

issuance of ICOs as many of the companies are looking to raise

money without having any tangible products. In the year 2018, as

many as 983 ICOs were issued, through which funds to the tune of

USD 20 billion were raised.

iii. Virtual currencies are accorded different legal treatment by

different countries, which range from barter transactions to mode of

payment to legal tender. Countries like China have imposed a

complete ban.

iv. The mining of non-official virtual currencies is very resource-

intensive requiring enormous amounts of electricity which may prove

to be an environmental disaster.

v. They may also affect the ability of the Central Banks to carry

out their mandates.

vi. China has not only banned trading in cryptocurrencies but

26

also used its firewall to ban crypto currency exchanges. China even

blocked crypto currency focused accounts from WeChat and crypto-

currency related content from Baidu. However, Chinese traders use

VPNs to circumvent these bans.

The report dated 28-02-2019 of the Inter-Ministerial Committee

finally made certain recommendations which included a complete

ban on private cryptocurrencies.

2.34. It is important to note here that the report of the Inter-

Ministerial Committee dated 28-02-2019 not only recommended

a ban, but also specifically endorsed the stand taken by RBI to

eliminate the interface of institutions regulated by RBI from

crypto currencies.

2.35. As a matter of fact, the issue of the impugned Circular by

RBI was even taken note of by the Financial Stability Board (of G-20),

in a document titled ‘Crypto Assets Regulators Directory’, submitted

to G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors in April

2019. While acknowledging the fact that RBI does not have a legal

mandate to directly regulate crypto assets, this Directory indicated

that with a view to ring fence its regulated entities from the risks

associated with VCs, RBI has issued the impugned Circular.

2.36. In a report released in June 2019 under the caption

‘Guidance for a risk-based approach to Virtual Assets and

Virtual Asset Service Providers’, FATF reiterated a risk-based

27

approach advocated in FATF 2012 and 2015 recommendations. At

the same time, this Guidance recognized that a jurisdiction has

the discretion to prohibit VA activities and VASPs in order to

support other policy goals not addressed in the Guidance such

as consumer protection, safety and soundness or monetary

policy. But the Guidance also suggested that countries which

prohibit VA activities or VASPs should also assess the effect that

such prohibition may have on their money laundering and terrorist

financing risks.

2.37. It is also relevant to note here that the Government was

conscious of the impugned Circular issued by RBI. This can be seen

from the answer provided by the Minister of State in the Ministry of

Finance, on 16-07-2019 in response to a question raised in the Rajya

Sabha (Unstarred question no. 2591). While answering in the

negative, the question whether the Government had banned

cryptocurrencies in the country, the Minister of State added that RBI

has been issuing advisories, press releases and circulars.

2.38. On 22-07-2019, the Report of the Inter-Ministerial

Committee, recommending a ban, along with the draft of the Bill

“Banning of Crypto currency and Regulation of Official Digital

Currency Bill 2019”, was hosted in the website of the Department of

Economic Affairs. Therefore, on 08-08-2019, the first two writ

petitions namely WP (C) Nos. 1071 and 1076 of 2017 were delinked

28

and adjourned to January 2020, since, the prayers made in these

two writ petitions (seeking a ban) appeared substantially answered.

2.39. Thereafter, the present writ petitions were taken up for

hearing and this Court passed an interim direction on 21-08-2019,

directing the Reserve Bank of India to give a detailed point-wise reply

to the representations dated 29-05-2018 and 30-05-2018. The reply

already given by RBI to the representations dated 29-05-2018 and

30-05-2018 was found by this Court to be inadequate and hence this

direction. Accordingly, RBI gave a detailed point-wise reply on 04-09-

2019 and 18-09-2019. Thereafter, the present writ petitions were

taken up for hearing.

3. FLASHBACK

3.1. The archeological excavations carried out at the (world wide

web) sites, reveal that this digital currency civilization is just 12 years

old (at the most, 37 years). But these excavations became necessary

since virtual currencies, known by different names such as crypto

assets, crypto currencies, digital assets, electronic currency, digital

currency etc., elude an exact and precise definition, making it

impossible to identify them as belonging either to the category of legal

tender solely or to the category of commodity/good or stock solely.

3.2. Any attempt to define what a virtual currency is, it

appears, should follow the Vedic analysis of negation namely “neti,

29

neti”. Avadhuta Gita of Dattatreya says, “by such sentences as ‘that

thou are’, our own self or that which is untrue and composed of

the 5 elements, is affirmed, but the sruti says ‘not this not

that’.”

4

The concept of Neti Neti is an expression of something

inexpressible, but which seeks to capture the essence of that to

which no other definition applies. This conundrum will squarely

apply to crypto currencies and hence this flashback, into its genesis,

so that its DNA is sequenced.

3.3. Though the idea of digital cash appears to have been first

introduced by David Lee Chaum, an American Computer Scientist

and Cryptographer way back in 1983 in a research paper and was

actually launched by him in 1990 through a company by name

Digicash, the company filed for bankruptcy in 1998, with Digicash

becoming Digi-crash. But the actual story of creation of

cryptocurrencies began, in a more scientific way, according to

Nathaniel Popper, the New York Times journalist,

5

in 1997, when a

British Cypherpunk

6

by name Adam Back released a plan called

hashcash, which claimed to have solved some of the problems that

stalled the digital cash project. But this program had its

shortcomings. Another Cypherpunk by name Nick Szabo, came up

4

tattvamasyādivākyena svātmā hi pratipāditaḥ

neti neti śrutirbrūyād anṛtaṁ pāñcabhautikam-

5

From his book “Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the inside story of the Misfits and Millionaires

Trying to Reinvent Money”.

6

Cypherpunk is an activist advocating widespread use of strong cryptography and privacy

enhancing technologies, as a route to social and political change. This word was added to

the Oxford English Dictionary in November 2006.

30

with a concept called bitgold, which attempted to solve hashcash’s

shortcomings. Soon, an American by name Wei Dai came up with

something called b-money. Hal Finney, another American created his

own option. But all of them had a common goal, which, as revealed

by Adam Back was as follows:

“What we want is fully anonymous, ultra low

transaction cost, transferable units of exchange. If

we get that going… the banks will become the

obsolete dinosaurs they deserve to become.”

3.4. But all these experiments continued to hit roadblocks,

until the emergence of Satoshi Nakamoto (who still remains

anonymous) in the world of netizens. It appears that Satoshi sent

an e-mail in August 2008 to Adam Back attaching a white paper

prepared by him on what was called ‘Bitcoin’. The gist of what

Satoshi stated in his paper is indicated in simple terms, for the

understanding of the common man, by Nathaniel Popper, in his

book as follows:

“Rather than relying on a central bank or company to issue

and keep track of the money – as the existing financial

system and Chaum’s DigiCash did – this system was set

up so that every Bitcoin transaction, and the holdings of

every user, would be tracked and recorded by the

computers of all the people using the digital money, on a

communally maintained database that would come to be

known as the blockchain.

The process by which this all happened had many layers,

and it would take even experts, months to understand how

they all worked together. But the basic elements of the

system can be sketched out in rough terms, and were in

Satoshi’s paper, which would become known as the

31

Bitcoin white paper.

According to the paper, each user of the system could have

one or more public Bitcoin addresses – sort of like bank

account numbers – and a private key for each address.

The coins attached to a given address could be spent only

by a person with the private key corresponding to the

address. The private key was slightly different from a

traditional password, which has to be kept by some

central authority to check that the user is entering the

correct password. In Bitcoin, Satoshi harnessed the

wonders of public-key cryptography to make it possible for

a user – let’s call her Alice again – to sign off on a

transaction, and prove she has the private key, without

anyone else ever needing to see or know her private key.

Once Alice signed off on a transaction with her private key

she would broadcast it out to all the other computers on

the Bitcoin network. Those computers would check that

Alice had the coins she was trying to spend. They could do

this by consulting the public record of all Bitcoin

transactions, which computers on the network kept a copy

of. Once the computers confirmed that Alice’s address did

indeed have the money she was trying to spend, the

information about Alice’s transaction was recorded in a list

of all recent transactions, referred to as a block, on the

blockchain. […]

The result of this complicated process was something that

was deceptively simple but never previously possible: a

financial network that could create and move money

without a central authority. No bank, no credit card

company, no regulators. The system was designed so that

no one other than the holder of a private key could spend

or take the money associated with a particular Bitcoin

address. What’s more, each user of the system could be

confident that, at every moment in time, there would be

only one public, unalterable record of what everyone in the

system owned. To believe in this, the users didn’t have to

trust Satoshi, as the users of DigiCash had to trust David

Chaum, or users of the dollar had to trust the Federal

Reserve. They just had to trust their own computers

running the Bitcoin software, and the code Satoshi wrote,

32

which was open source, and therefore available for

everyone to review. If the users didn’t like something about

the rules set down by Satoshi’s software, they could

change the rules. People who joined the Bitcoin network

were, quite literally, both customers and owners of both

the bank and the mint.”

3.5. That Satoshi and the Cypherpunks who

participated in the initial experiments developed Bitcoin as

an alternative to conventional currency, to counter the

problems of debasement of currency by central agencies, was

made clear by Satoshi himself when he said: “The root problem

with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it

work. The Central Bank must be trusted not to debase the currency

but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.”

3.6. What attracted people to Satoshi’s proposal, was the fact

that while Central Banks had no restraints in unlimited printing of

money, thereby devaluing all savings and holdings, the Bitcoin

software had rules to ensure that the process of creating new

coins would stop after 21 million were out in the world. When

Martti Malmi, a student at the Helsinki University of Technology,

joined hands with Satoshi to improvise the project and to market

it, he formulated the philosophy in the following words:

“Be safe from the unfair monetary policies of the

monopolistic Central Banks and the other risks of

centralized power over a money supply. The limited

inflation of Bitcoin system’s money supply is

33

distributed evenly (by CPU power) throughout the

network, not monopolized to a banking elite.”

3.7. Therefore, it is beyond any pale of doubt that irrespective of

the metamorphosis (or gene mutation) it has undergone over the

years, bitcoin, the Adam or Manu of the race of cryptocurrencies, was

developed as an alternative to fiat currency. Keeping this birth chart

of virtual currencies in mind, let us now see how the petitioners are

aggrieved by the impugned decisions of RBI, the grounds on which

they challenge the same and the justification sought to be provided

by RBI.

4. BACKGROUND SCORE (of the petitioners)

4.1. The theme of the song of the petitioners in one of the writ

petitions, as fine-tuned by Shri Ashim Sood, learned Counsel, can be

summarized as follows:

I. RBI has no power to prohibit the activity of trading in virtual

currencies through VC exchanges since:

(i) Virtual currencies are not legal tender but tradable

commodities/digital goods, not falling within the regulatory

framework of the RBI Act, 1934 or the Banking Regulation

Act, 1949.

(ii) Virtual currencies do not even fall within the credit

system of the country, so as to enable RBI to fall back upon

the Preamble to the RBI Act 1934, which gives a mandate

34

to RBI to operate the currency and credit system of the

country to its advantage.

(iii) Neither the power to regulate the financial system of

the country to its advantage conferred under Section 45JA,

nor the power to regulate the credit system of the country

conferred under Section 45L of the RBI Act, 1934

exercisable in public interest and upon arriving at a

satisfaction, is so elastic as to cover goods that do not fall

within the purview of the financial system or credit system

of the country.

(iv) The power to issue directions “in the public interest”

conferred under Section 35A(1)(a) of the Banking

Regulation Act, 1949 and the power to caution or prohibit

banking companies against entering into any particular

transaction conferred under Section 36(1)(a) do not extend

to the issue of blanket directions that would deny access by

virtual currency exchanges, to the banking services of the

country, as the expression “public interest” appearing in a

particular provision in a statute should take its colour from

the context of the statute.

(v) The power conferred upon RBI under Section 10(2) of

the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 to issue

guidelines for proper and efficient management of payment

35

systems and under Section 18 of the said Act to lay down

policies relating to the regulation of payment systems and

to give directions pertaining to the conduct of business

relating to payments systems, exercisable in public interest

upon being satisfied, is also not applicable to virtual

currency exchanges, as the services rendered by them do

not fall within the definition of the expression “payment

system” under Section 2(1)(i) of the said Act.

II. Assuming but not admitting that RBI has the power to deal with

the activities carried on by VCEs, the mode of exercise of such power

can be tested on certain well established parameters. They are –

(i) application of mind/satisfaction/relevant and irrelevant

considerations

(ii) Malice in law/colorable exercise of power

(iii) M.S. Gill reasoning

(iv) Calibration/Proportionality

III. All other stake holders such as the Department of Economic

Affairs of the Government of India, Securities and Exchange Board of

India, Central Board of Direct Taxes, etc., have actually recognized

the positive and beneficial aspects of cryptocurrencies as digital

assets and the Distributed Ledger Technology from which crypto

currencies emanate and hence have recommended only a regulatory

36

regime, but RBI has taken a contra position without any rational

basis.

IV. Many of the developed and developing economies of the world,

multinational and international bodies and the courts of various

countries have scanned crypto currencies, but found nothing

pernicious about them and even the attempt of the Government of

India to bring a legislation banning crypto currencies, is yet to reach

its logical end.

V. RBI should have taken into account the fact that the members of

Petitioner association have taken necessary precautions including

avoiding cash transactions, ensuring compliance with KYC norms, of

their own accord and allowing peer-to-peer transactions only within

the country.

VI. RBI has not applied its mind to the fact that not every crypto

currency is anonymous. The report of the European Parliament also

classified VCs into anonymous and pseudo-anonymous. Therefore, if

the problem sought to be addressed is anonymity of transactions, the

same could have been achieved by resorting to the least invasive

option of prohibiting only anonymous VCs.

VII. It is a paradox that blockchain technology is acceptable to RBI,

but crypto currency is not.

VIII. The benefit of the rule of judicial deference to economic policies

37

of the state is not available to RBI, as the impugned Circular is an

exercise of power by a statutory body corporate and is neither a

legislation nor an exercise of executive power. In any case, there is no

deference in law to process but only to opinion emanating from the

process. No study was undertaken by RBI before the impugned

measure was taken and hence, the impugned decisions are not even

based upon knowledge or expertise.

IX. While regulation of a trade or business through reasonable

restrictions imposed under a law made in the interests of the general

public is saved by Article 19(6) of the Constitution, a total

prohibition, especially through a subordinate legislation such as a

directive from RBI, of an activity not declared by law to be unlawful,

is violative of Article 19(1)(g). Whether a directive would tantamount

to “regulation” or “prohibition”, depends upon the impact of the

directive.

4.2. The contentions of the petitioners in the other writ petition

(WP (C) No. 373 of 2018), as set to tune by Shri Nakul Dewan,

learned Senior Counsel, are:

I. The immediate effect of the impugned Circular is to completely

severe the ties between the virtual currency market and the formal

Indian economy, without actually a legislative ban on the trading of

VCs, thereby promoting cash and black-market transactions.

II. The impugned Circular fails to take note of the difference between

38

various VC schemes such as closed VC schemes, unidirectional flow

VC schemes and bidirectional flow VC schemes and unreasonably

differentiates between unidirectional flow schemes and bidirectional

flow schemes, by targeting only bidirectional flow schemes.

III. VCs do not qualify as money, as they do not fulfill the four

characteristics of money namely medium of exchange, unit of

account, store of value and constituting a final discharge of debt and

since RBI has accepted this position, they have no power to regulate

it.

IV. Considering the fact that historically, money as understood in the

social sense and money as understood in the legal sense, are

different, the courts in different jurisdictions such as USA and

Singapore have understood VCs to be akin to money or funds at

times or as commodities/intangible properties at other times.

V. The impugned Circular is manifestly arbitrary, based on non-

reasonable classification and it imposes disproportionate restrictions.

VI. A decision to prohibit an article as res extra commercium is a

matter of legislative policy and must arise out of an Act of legislature

and not by a notification issued by an executive authority.

4.3. In addition to the aforementioned legal contentions, Shri

Nakul Dewan learned Senior Counsel also submitted that as a result

of the impugned Circular, the virtual currency exchange (VCE) run

by one of the petitioners in one writ petition was shut down on 30-

39

03-2019, the VCE run by another petitioner became non-operational,

though their website still opens and the VCE run by yet another

petitioner by name Discidium Internet Labs Pvt. Ltd., not only

became non-operational, but an amount of Rs. 12 crores lying in

their account also got frozen. However, one VCE by name CoinDCX

alone survives, by operating on a peer-to-peer (P2P) basis.

4.4. In support of their respective contentions, Shri Ashim Sood

and Shri Nakul Dewan, the learned counsels, relied upon a number

of decisions of this court and other courts. We shall refer to them

when we take up their contentions for analysis.

5. SCRIPT (of RBI)

5.1. RBI has filed counter-affidavit in one of these writ petitions,

covering the entire gamut. But the response of RBI to the contentions

of the petitioners is available not only in the counter-affidavit, but

also in some communications issued by them pursuant to certain

interim directions issued by this court.

5.2. For instance, this Court passed an interim direction on 21-

08-2019, after hearing lengthy arguments, directing the Reserve

Bank of India to give a detailed point-wise reply to the

representations dated 29-05-2018 and 30-05-2018. Pursuant to the

said interim direction, RBI gave a detailed point-wise reply on 04-09-

2019 and 18-09-2019. Therefore, RBI’s stand in these cases has to

40

be culled out not only from the counter-affidavit but also from the

orders passed/replies issued to the representations of the writ

petitioners, during the pendency of these writ petitions.

5.3. In brief, the response of RBI to the issues raised by the

petitioners, as articulated by Shri Shyam Divan, learned Senior

Counsel, can be summarized as follows:

(i) Virtual currencies do not satisfy the criteria such as

store of value, medium of payment and unit of account,

required for being acknowledged as currency.

(ii) Virtual currency exchanges do not have any formal or

structured mechanism for handling consumer disputes/

grievances.

(iii) Virtual currencies are capable of being used for illegal

activities due to their anonymity/pseudo-anonymity.

(iv) Increased use of virtual currencies would eventually

erode the monetary stability of the Indian currency and the

credit system.

(v) The impugned decision of RBI is legislative in

character and is in the realm of an economic policy

decision taken by an expert body warranting a hands-off

approach from the Court.

(vi) The impugned decision is within the range of wide

powers conferred upon RBI under the Banking Regulation

41

Act, 1949, the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and the

Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007.

(vii) No one has an unfettered fundamental right to do

business on the network of the entities regulated by RBI.

(viii) The impugned decisions do not violate any of the

rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the

Constitution of India.

(ix) The impugned decisions are not excessive,

confiscatory or disproportionate in as much as RBI has

given three months’ time to the affected parties to sever

their relationships with the banks. This is apart from the

repeated cautions issued to the stakeholders by RBI

through Press Releases from the year 2013.

(x) The ambit of the 2013 press release was much wider

than just consumer protection. RBI cautioned users,

holders and traders of VCs about the potential financial,

operational, legal, customer protection and security related

risks they were exposing themselves to.

(xi) The host of material taken note of by RBI in their

reports, the reports of the committees to which RBI was a

party and the cautions repeatedly issued by RBI over a

period of 5 years, would demonstrate the application of

mind on the part of RBI. They also demonstrate that RBI

42

did not proceed in haste but proceeded with great care and

caution. Therefore, the satisfaction arrived at by them was

too loud and clear to be ignored. The standard for

considering the impugned Circular, is the existence of

material and not the adequacy or sufficiency of such

material.

(xii) In any case, there is no complete ban on virtual

currencies or on the use of distributed ledger technology by

the regulated entities.

(xiii) The impugned decisions were necessitated in public

interest to protect the interest of consumers, the interest of

the payment and settlement systems of the country and for

protection of regulated entities against exposure to high

volatility of the virtual currencies. RBI is empowered and

duty bound to take such pre-emptive measures in public

interest and the power to regulate includes the power to

prohibit.

(xiv) The impugned decisions were necessitated because in

the opinion of RBI, VC transactions cannot be termed as a

payment system, but only peer-to-peer transactions which

do not involve a system provider under the Payments and

Settlement Systems Act. Despite this, VC transactions have

the potential to develop as a parallel system of payment.

43

(xv) The KYC norms followed by the VCEs are far below

what other participants in the payments and monetary

system follow. In any case, KYC norms are ineffective, as

the inherent characteristic of anonymity of VCs does not

get remedied.

(xvi) Cross-border nature of the trade in VCs, coupled with

the lack of accountability, has the potential to impact the

regulated payments system managed by RBI. A large

constituent of the VC universe does not hold membership

of the Petitioner association or is not even accountable for

their acts but is material and instrumental in driving the

VC trade.

(xvii) RBI or any other Government authority would not be

able to curtail, limit, regulate or control the generation of

VCs and their transactions, resulting in ever-present and

inevitable financial risks.

6. UNFOLDING OF THE PLOT

6.1. In the light of the above factual matrix and the rival

contentions, let us now see how the plot before us, unfolds.

I. No Power at all for RBI (Ultra vires)

6.2. The first ground of attack revolves around the power of RBI

to deal with, regulate or even ban VCs and VCEs. The entire

44

foundation of this contention rests on the stand taken by the

petitioners that VCs are not money or other legal tender, but only

goods/commodities, falling outside the purview of the RBI Act, 1934,

Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and the Payment and Settlement

Systems Act, 2007. In fact, the impugned Circular of RBI dated 06-

04-2018 was issued in exercise of the powers conferred upon RBI by

all these three enactments. Therefore, if virtual currencies do not fall

within subject matter covered by any or all of these three enactments

and over which RBI has a statutory control, then the petitioners will

be right in contending that the Circular is ultra vires.

6.3. Hence it is necessary (i) first to see the role historically

assigned to a central bank such as RBI, the powers and functions

conferred upon and entrusted to RBI and the statutory scheme of all

the above three enactments and (ii) then to investigate what these

virtual currencies really are. Therefore, we shall divide our discussion

in this regard into two parts, the first concerning the role, powers

and functions of RBI and the second concerning the identity of

virtual currencies.

Role assigned to, functions entrusted to and the powers

conferred upon RBI as a Central Bank

6.4. The Reserve Bank of India was established under Act 2 of

1934 for the purpose of (i) regulating the issue of bank notes, (ii)

keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in the

45

country and (iii) operating the currency and credit system of the

country to its advantage. The role of a central bank such as the

Reserve Bank in an economy is to manage (i) the currency (ii) the

money supply and (iii) interest rates. The unique feature of a central

bank is the monopoly that it has on increasing the monetary base in

the state and the control it has in the printing of the national

currency. The central bank virtually functions as “a lender of last

resort” to banks suffering a liquidity crisis.

6.5. Historians trace the rise of modern central banks to the

establishment of the Bank of England under a Royal Charter granted

on 27-07-1694 through the Tunnage Act, 1694. The establishment of

this bank in 1694 was not actually for stimulating the economy but

for financing the war that England had with France. The currency

crisis of 1797 and the creation of a ratio between the gold reserves

held by the Bank of England and the notes that the bank could

issue, under the Bank Charter Act, 1844 brought huge changes in

the way the central bank was supposed to function.

6.6. In so far as India is concerned, the functions of a central

bank were originally conferred upon the Imperial Bank of India,

established in the year 1921, under the Imperial Bank of India Act,

1920. The reason why and the manner in which the Imperial Bank

was established, is quite interesting to see. At the time when the

46

British Crown took over the control of the territories in India, after

the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, there were three Presidency Banks, one in

Calcutta, another in Bombay and the third in Madras. All these three

banks established respectively in 1809, 1840 and 1843, were

authorized to issue notes up to certain specified limits. But this

privilege was withdrawn in 1862 under the Paper Currency Act,

which vested the sole right to issue notes with the Government of

India.

6.7. The question of absorption of the three Presidency Banks

into a central bank came up for consideration on and off. Though the

Chamberlain Commission, known as the Royal Commission on

Indian Finance and Currency, appointed in 1913, felt the need for

setting up a central bank, the proposal did not materialize. But after

the First World War, the Presidency Banks themselves favoured an

amalgamation. Therefore, the Imperial Bank of India Bill providing for

the amalgamation of all the three Presidency Banks was passed in

September 1920 and came into effect in January 1921. The trend of

setting up central banks gained momentum internationally, after the

International Financial Conferences held at Brussels in 1920 and at

Genoa in 1922.

6.8. But the maintenance of an overvalued exchange rate to

help British exporters, gave rise to a clash between the colonial

47

administration and Indian business interests. The Congress sought

devaluation and hence a Royal Commission was set up in 1925 to

examine the matter. This Royal Commission on Indian Currency and

Finance, also known as Hilton Young Commission (to which Dr. B. R.

Ambedkar also contributed a statement), recommended the creation

of a strong Central Bank for India in 1926. Though a bill known as

the Gold Standard and Reserve Bank of India Bill, 1927 to give effect

to the recommendations was introduced in the Legislative Assembly,

it was withdrawn on 10-02-1928. From 1930 onwards, the question

of establishing a Reserve Bank received fresh impetus, when

Constitutional reforms for the country were undertaken.

6.9. The White Paper on Indian Constitutional Reforms,

presented in March 1933, assumed that a Reserve Bank, free from

political influence, would have to be set up and should already be

successfully operating before the first Federal Ministry was installed.

6.10. Subsequently, a Departmental Committee (hereinafter

referred to, as “the India Office Committee”) was appointed in

London by the India Office, which submitted a report dated 14-03-

1933. This report was followed up by the appointment of the “London

Committee”, which endorsed the India Office Committee’s view that

the Reserve Bank should be free from any political influence.

48

6.11. Therefore, a Bill drafted on the basis of the

recommendations of the London Committee was introduced in

September 1933. In 1934, the Bill was passed. The Reserve Bank of

India commenced operations as the country’s central bank on 01-04-

1935. Under the Reserve Bank (Transfer of Public Ownership) Act,

1948, the bank was nationalized.

6.12. Once the historical background of the creation of RBI is

understood, it will be easy to appreciate its role in the economy of the

country and the functions and powers exercised by it statutorily.

6.13. As the Preamble of the RBI Act suggests, the object of

constitution of RBI was threefold namely (i) regulating the issue of

bank notes (ii) keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary

stability in the country and (iii) operating the currency and credit

system of the country to its advantage.

6.14. In fact, the original Preamble of the Act contained only

three paragraphs. But paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Preamble were

substituted with 3 new paragraphs by Act 28 of 2016. Paragraphs 2

and 3 of the original Preamble and paragraphs 2 to 4 substituted in

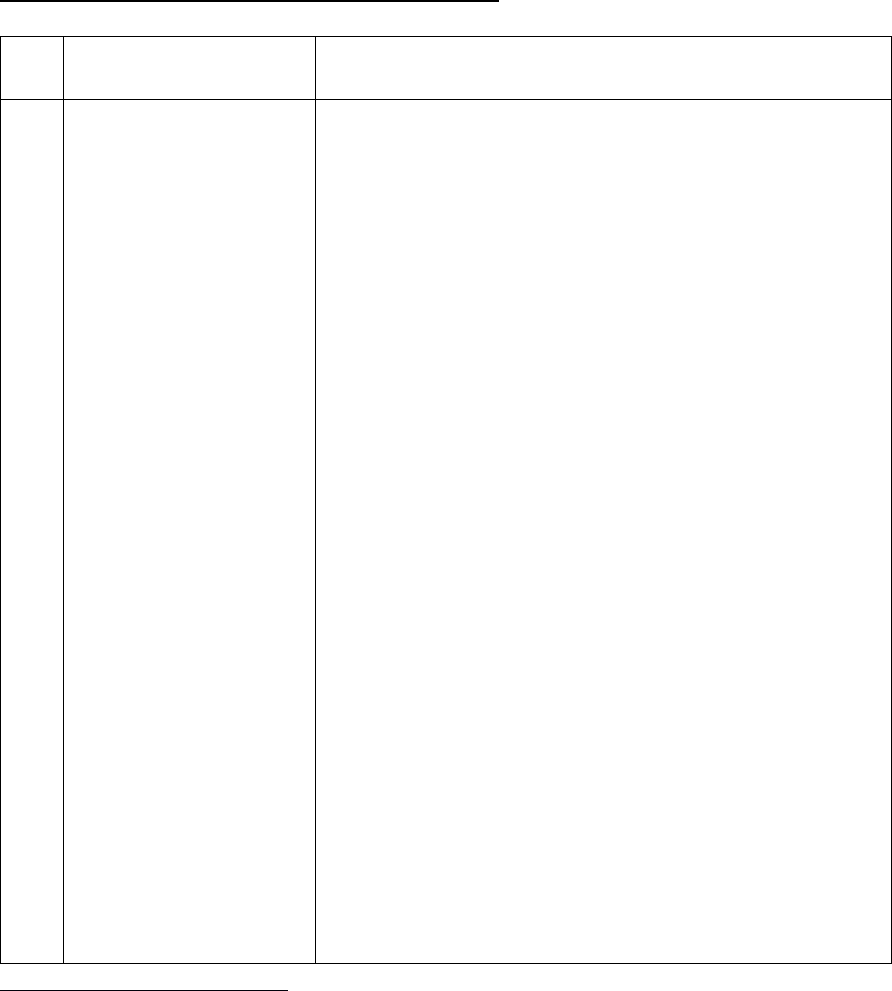

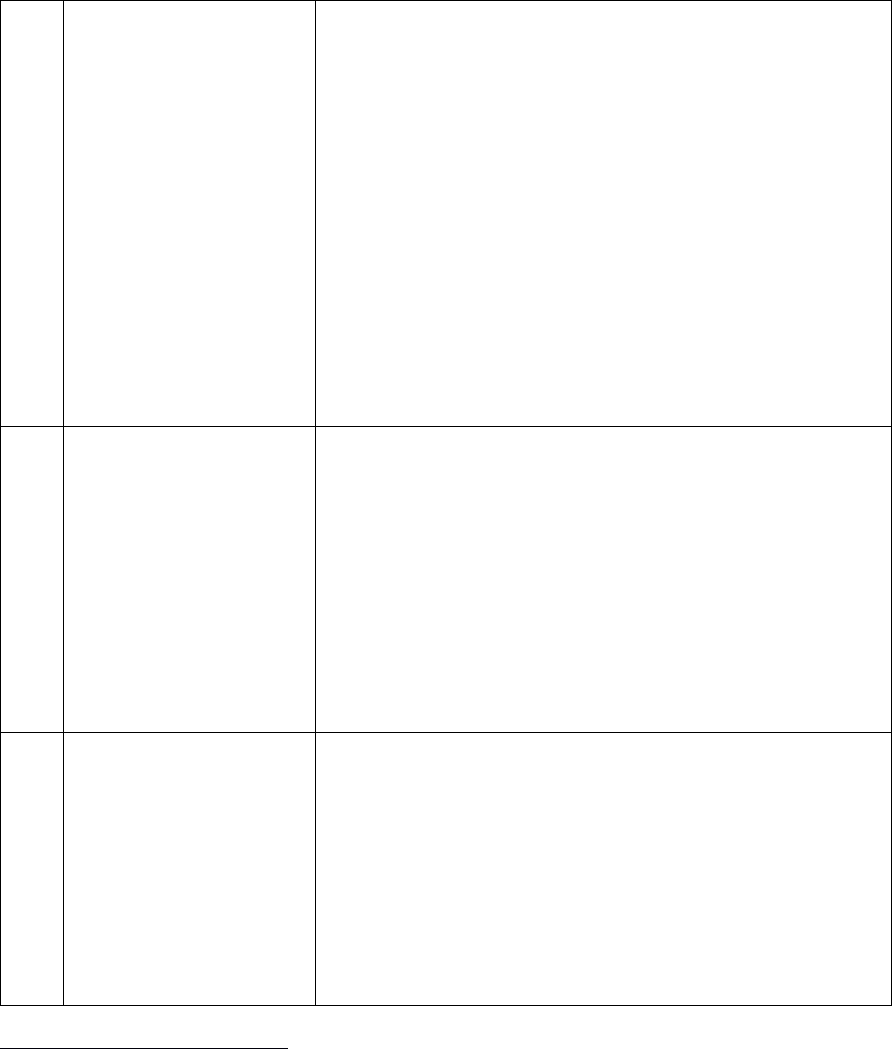

2016, are presented in a tabular column as follows:

49

Paragraphs 2 and 3 as they originally

stood

Paragraphs 2 to 4 now substituted

AND WHEREAS in the present

disorganisation of the monetary

systems of the world it is not

possible to determine what will be

suitable as a permanent basis for the

Indian monetary system;

BUT WHEREAS it is expedient to

make temporary provision on the

basis of the existing monetary

system, and to leave the question of

the monetary standard best suited to

India to be considered when the

international monetary position has

become sufficiently clear and stable

to make it possible to frame

permanent measures;

AND WHEREAS it is essential to have a

modern monetary policy framework to

meet the challenge of an increasingly

complex economy;

AND WHEREAS the primary

objective of the monetary policy is to

maintain price stability while keeping in

mind the objective of growth;

AND WHEREAS the monetary policy

framework in India shall be operated by

the Reserve Bank of India;

6.15. It may be observed from the newly substituted paragraphs

that RBI is now vested with the obligation to operate the

monetary policy framework in India. An indication of the primary

objective of the monetary policy is provided in paragraph 3 which

says that the maintenance of price stability is the prime

objective even while the objective of growth is to be kept in

mind. Paragraph 2 recognizes the necessity to have a modern

monetary policy framework to meet the challenge of an increasingly

complex economy.

6.16. Therefore, it is clear that after the amendment under Act

28 of 2016, the very task of operating the monetary policy framework

has been conferred exclusively upon RBI.

50

6.17. Though the expression “monetary policy” is not defined in

the Act, an entire chapter under the title “Monetary Policy”

containing Sections 45Z to 45ZO was inserted as Chapter IIIF. The

provisions of this chapter are given overriding effect upon the other

provisions of the Act, under Section 45Z. Under Section 45ZA(1), the

central government is empowered to determine the inflation target in

terms of the consumer price index, once in every 5 years, in

consultation with RBI. The policy rate required to achieve the

inflation target is to be determined by a Monetary Policy Committee,

constituted under Section 45ZB.

6.18. The object of establishment of RBI is also spelt out in

Section 3(1). It says that “a bank to be called the Reserve Bank of

India shall be constituted for the purpose of taking over the

management of the currency from the Central Government and