Bank Holding Company

Supervision

Manual

Division of Supervision and Regulation

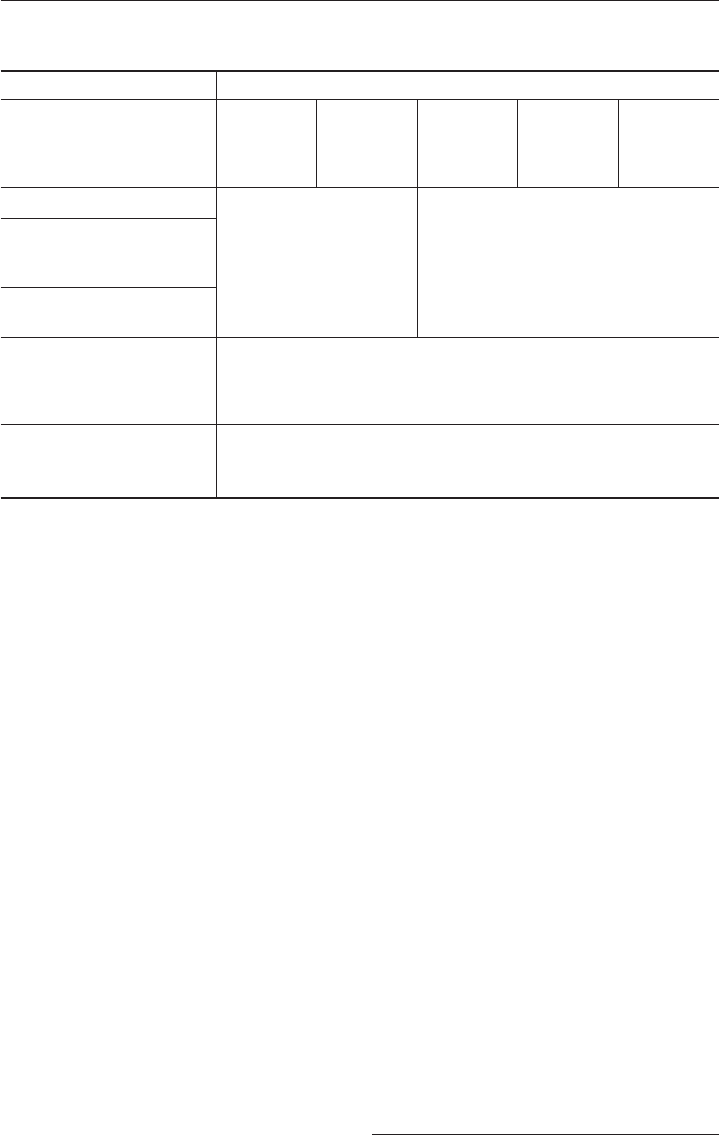

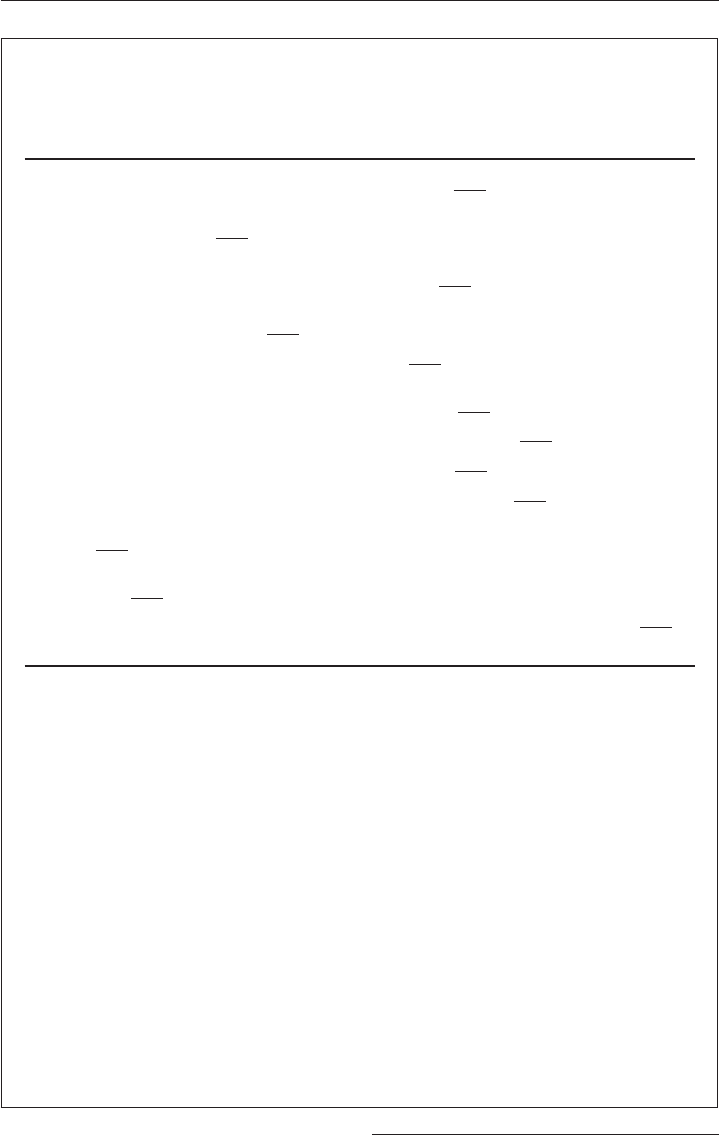

General Table of Contents

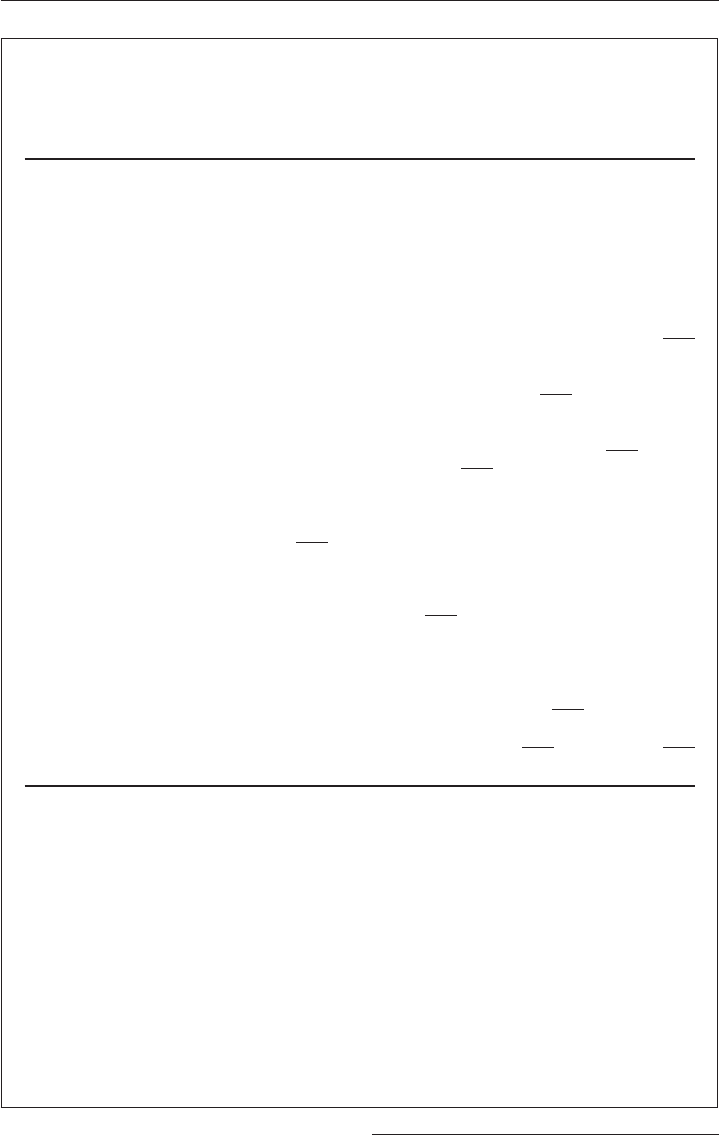

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual

This general table of contents lists the major section heads for each part of the manual:

1000 About this Manual, Supervisory Process

2000 Supervisory Policy and Issues

3000 Nonbanking Activities

4000 Financial Analysis

5000 BHC Inspection Program

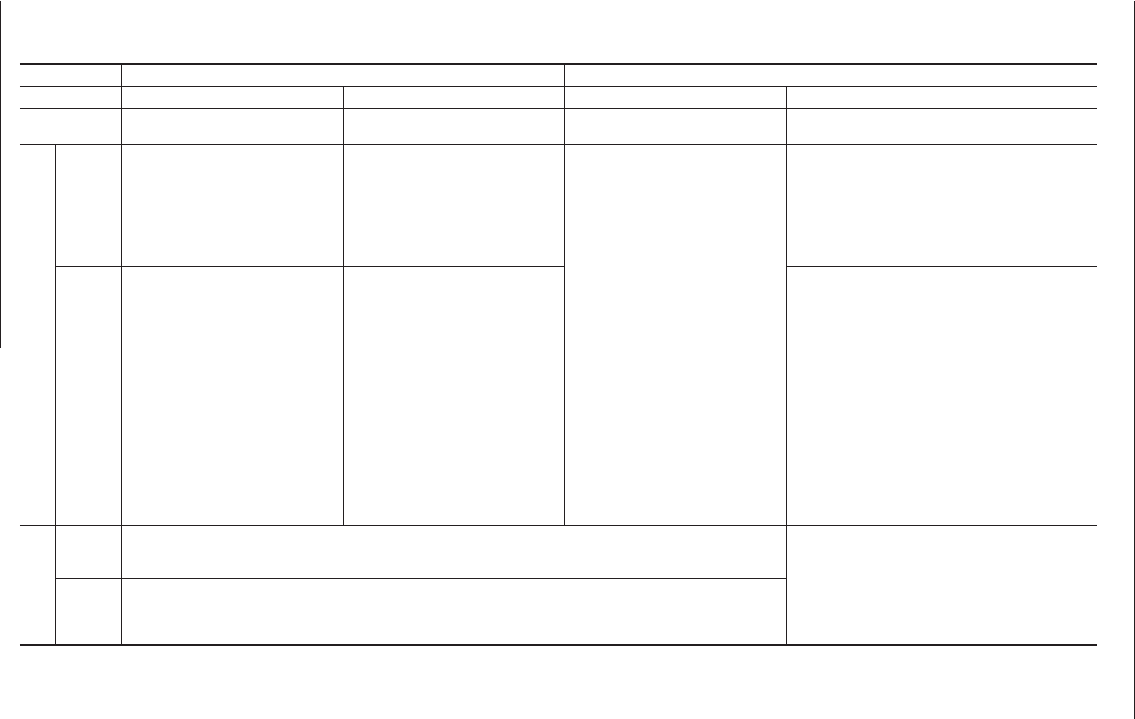

Sections Title

1000 ABOUT THIS MANUAL, SUPERVISORY PROCESS

1000.0 About this Manual

1020.0 Supervision of Savings and Loan Holding Companies

1040.0 Bank Holding Company Examination and Inspection Authority

1045.0 Supervision of Holding Companies with Less Than $10 Billion

in Total Consolidated Assets

1050.0 Consolidated Supervision of Bank Holding Companies and the Combined

U.S. Operations of Foreign Banking Organizations

1050.1 Guidance for the Consolidated Supervision of Domestic Bank Holding

Companies That Are Large Complex Banking Organizations

1050.2 Consolidated Supervision of Regional Holding Companies

1060.0 Large Financial Institution Rating System

1060.1 Large Financial Institution Rating System: Capital Planning and Positions

1060.2 Supervisory Assessment of Capital Planning and Positions for Category I Firms

1060.3 Supervisory Assessment of Capital Planning and Positions for Category II

or III Firms

1060.20 Liquidity Planning and Positions

1060.30 Supervisory Guidance on Board of Directors’ Effectiveness (Governance

and Controls)

1060.31 Assessment of Risk-Management Processes and Internal Controls of

BHCs Having $100 Billion or More in Total Assets

1062.0 RFI Rating System

1062.1 Supervisory Guidance for Assessing Risk Management at Supervised

Institutions with Total Consolidated Assets Less than $100 Billion

1063.0 Holding Company Ratings Applicability and Inspection Frequency

1065.0 Nondisclosure of Supervisory Ratings and Confidential Supervisory

Information

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 1

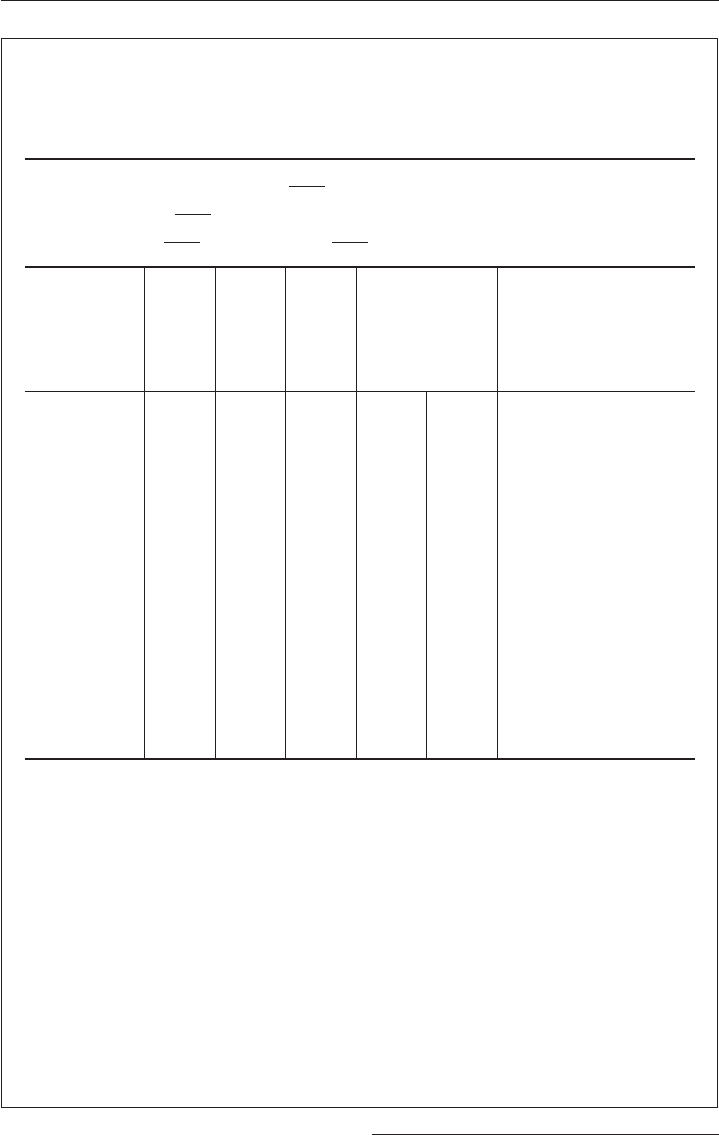

Sections Title

1070.1 Communication of Supervisory Findings

1072.0 Considerations in Assigning and Revising Supervisory Ratings

1075.0 Formal Corrective Actions

1080.0 Federal Reserve System Holding Company Surveillance Program

1080.1 Surveillance Program for Small Holding Companies

2000 SUPERVISORY POLICY AND ISSUES

2000.0 Introduction to Topics for Supervisory Review

2010.0 Supervision of Subsidiaries

2010.1 Funding Policies

2010.2 Loan Administration

2010.3 Investments

2010.4 Consolidated Planning Process

2010.5 Environmental Liability

2010.6 Retail Sales of Nondeposit Investment Products

2010.7 Reserved

2010.8 Sharing of Facilities and Staff by Banking Organizations

2010.9 Required Absences from Sensitive Positions

2010.10 Internal Loan Review

2010.11 Private-Banking Functions and Activities

2010.12 Fees Involving Investments of Fiduciary Assets in Mutual Funds and Potential

Conflicts of Interest

2010.13 Establishing Accounts for Foreign Governments Embassies, and Political

Figures

2020.0 Intercompany Transactions

2020.1 Transactions Between Member Banks and Their Affiliates—Sections 23A

and 23B of the Federal Reserve Act

2020.2 Loan Participations

2020.3 Sale and Transfer of Assets

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 2

Sections Title

2020.4 Compensating Balances

2020.5 Dividends

2020.6 Management and Service Fees

2020.7 Transfer of Low-Quality Assets

2020.8 Reserved

2020.9 Split-Dollar Life Insurance

2030.0 Grandfather Rights—Retention and Expansion of Nonbank Activities

2040.0 Commitments to the Federal Reserve

2050.0 Extensions of Credit to BHC Officials

2060.0 Management Information Systems (General)

2060.05 Policy Statement on the Internal Audit Function and Its Outsourcing

2060.07 Supplemental Policy Statement on the Internal Audit Function and

Its Outsourcing

2060.1 Audit

2060.2 Budget

2060.3 Records and Statements

2060.4 Structure and Reporting

2060.5 Insurance

2065.1 Nonaccrual Loans (Accounting, Reporting, and Disclosure Issues)

2065.2 Maintaining and Documenting the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses

2065.3 Allowance for Credit Losses

2068.0 Sound Incentive Compensation Policies

2070.0 Taxes—Consolidated Tax Filing

2080.0 Funding—Introduction

2080.05 Bank Holding Company Funding and Liquidity

2080.1 Commercial Paper and Other Short-term Uninsured Debt Obligations

and Securities

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 3

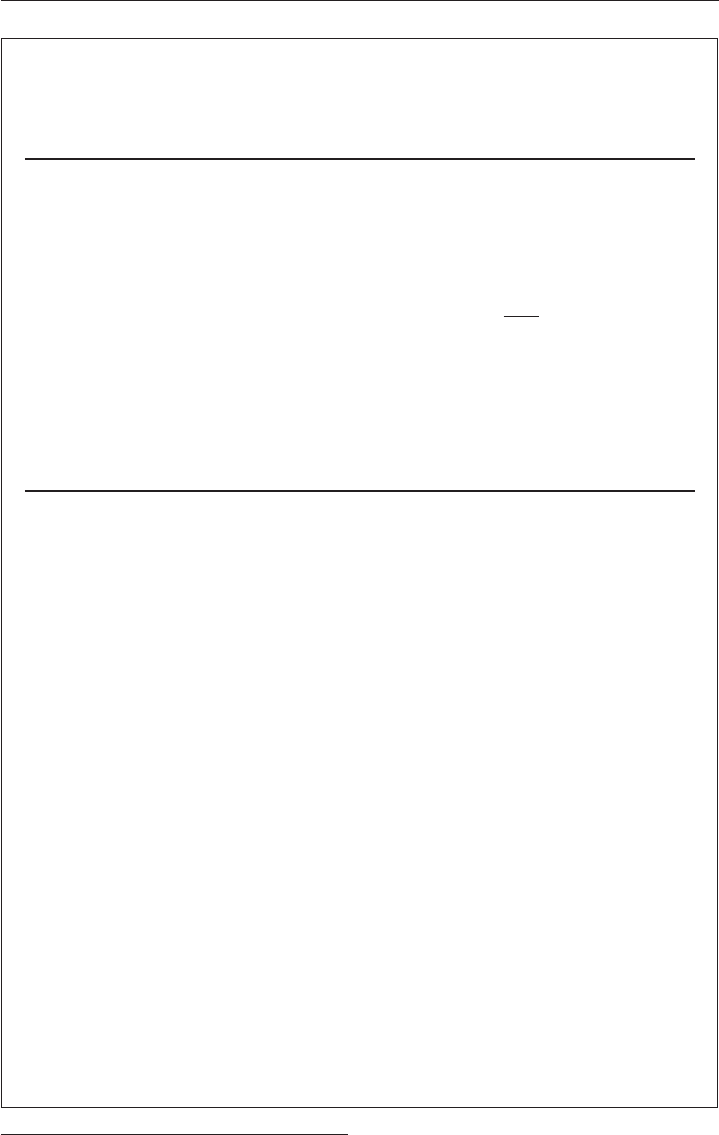

Sections Title

2080.2 Long-Term Debt

2080.3 Equity

2080.4 Retention of Earnings

2080.5 Pension Funding and Employee Stock Option Plans

2080.6 Holding Company Funding from Sweep Accounts

2090.0 Control and Ownership—General

2090.05 Qualified Family Partnerships

2090.1 Change in Control

2090.2 BHC Formations

2090.3 Treasury Stock Redemptions

2090.4 Policy Statements on Equity Investments in Banks and Bank

Holding Companies

2090.5 Acquisitions of Bank Shares Through Fiduciary Accounts

2090.6 Control Determinants

2090.7 Nonbank Banks

2090.8 Liability of Commonly Controlled Depository Institutions

2091.0−

2092.0

Reserved

2093.0 Control and Ownership—Shareholder Protection Arrangements

2100.0 International Banking Activities

2120.0 Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Federal Election Campaign Act

2122.0 Internal Credit-Risk Ratings at Large Firms

2124.0 Risk-Focused Safety-and-Soundness Inspections

2124.01–

2124.04

Reserved

2124.05 Consolidated Supervision Framework for Large Financial Institutions

2124.07 Compliance Risk-Management Programs and Oversight at Large Firms

2124.1 Assessment of Information Technology in Risk-Focused Supervision

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 4

Sections Title

2124.2 Reserved

2124.3 Managing Outsourcing Risk

2124.4 Information Security Standards

2124.5 Identity Theft Red Flags and Address Discrepancies

2126.0 Model Risk Management

2126.1 Investment Securities and End-User Derivatives Activities

2126.2 Investing in Securities without Reliance on Ratings of Nationally

Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations

2126.3 Counterparty Credit Risk Management Systems

2126.5 Volcker Rule (Section 13 of the Bank Holding Company Act)

2127.0 Interest-Rate Risk—Risk Management and Internal Controls

2128.0 Structured Notes—Risk Management and Internal Controls

2128.01 Reserved

2128.02 Asset Securitization

2128.03 Credit-Supported and Asset-Backed Commercial Paper

2128.04 Implicit Recourse Provided to Asset Securitizations

2128.05 Securitization Covenants Linked to Supervisory Actions or Thresholds

2128.06 Valuation of Retained Interests and Risk Management of Securitization

Activities

2128.07 Reserved

2128.08 Subprime Lending

2128.09 Elevated-Risk Complex Structured Finance Activities

2129.0 Credit Derivatives—Risk Management and Internal Controls

2129.05 Risk and Capital Management—Secondary-Market Credit Activities

2130.0 Futures, Forward, and Option Contracts

2140.0 Securities Lending

2150.0 Repurchase Transactions

2160.0 Recognition and Control of Exposure to Risk

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 5

Sections Title

2175.0 Sale of Uninsured Annuities

2178.0 Support of Bank-Affiliated Investment Funds

2180.0 Securities Activities in Overseas Markets

2187.0 Violations of Federal Reserve Margin Regulations Resulting from

“Free-Riding” Schemes

2220.3 Note Issuance and Revolving Underwriting Credit Facilities

2231.0 Real Estate Appraisals and Evaluations

2240.0 Guidelines for the Review and Classification of Troubled Real Estate Loans

2241.0 Retail-Credit Classification

2250.0 Domestic and Other Reports to Be Submitted to the Federal Reserve

2260.0 Venture Capital

3000 NONBANKING ACTIVITIES

3000.0 Introduction to BHC Nonbanking and FHC Activities

3001.0 Section 2(c) of the BHC Act—Savings Bank Subsidiaries of BHCs Engaging in

Nonbanking Activities

3005.0 Section 2(c)(2)(F) of the BHC Act—Credit Card Bank Exemption from the

Definition of a Bank

3010.0 Section 4(c)(i) and (ii) of the BHC Act—Exemptions from Prohibitions on

Acquiring Nonbank Interests

3020.0 Section 4(c)(1) of the BHC Act—Investment in Companies Whose Activities

Are Incidental to Banking

3030.0 Section 4(c)(2) and (3) of the BHC Act—Acquisition of DPC Shares, Assets, or

Real Estate

3032.0 Rental of Other Real Estate Owned Residential Property

3040.0 Section 4(c)(4) of the BHC Act—Interests in Nonbanking Organizations

3050.0 Section 4(c)(5) of the BHC Act—Investments Under Section 5136 of the

Revised Statutes

3060.0 Section 4(c)(6) and (7) of the BHC Act—Ownership of Shares in Any Nonbank

Company of 5 Percent or Less

3070.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Mortgage Banking

3070.3 Nontraditional Mortgages—Associated Risks

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 6

Sections Title

3071.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Mortgage Banking— Derivative

Commitments to Originate and Sell Mortgage Loans

3072.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Activities Related to Extending Credit

3072.8 Real Estate Settlement Services

3073.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Education-Financing Activities

3080.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Servicing Loans

3084.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Asset-Management, Asset-Servicing,

and Collection Activities

3090.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Receivables

3090.1 Factoring

3090.2 Accounts Receivable Financing

3100.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Consumer Finance

3104.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Acquiring Debt in Default

3105.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Credit Card Authorization and

Lost/Stolen Credit Card Reporting Services

3107.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Stand-Alone Inventory Inspection Services

3110.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Industrial Banking

3111.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Acquisition of Savings Associations

3120.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Trust Services

3130.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—General Financial and Investment Advisory

Activities

3130.1 Investment or Financial Advisers

3130.2 Reserved

3130.3 Advice on Mergers and Similar Corporate Structurings, Capital Structurings,

and Financing Transactions

3130.4 Informational, Statistical Forecasting, and Advisory Services for Transactions

in Foreign Exchange and Swaps, Commodities, and Derivative Instruments

3130.5 Providing Educational Courses and Instructional Materials for Consumers on

Individual Financial Management Matters

3130.6 Tax-Planning and Tax-Preparation Services

3140.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Leasing Personal or Real Property

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 7

Sections Title

3150.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Community Welfare Projects

3160.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—EDP Servicing Company

3160.1 EDP Servicing—Network for the Processing and Transmission of Medical

Payment Data

3160.2 Electronic Benefit Transfer, Stored-Value-Card, and Electronic Data

Interchange Services

3160.3 Data Processing Activities: Obtaining Traveler’s Checks and Postage Stamps

Using an ATM Card and Terminal

3160.4 Providing Data Processing for ATM Distribution of Tickets, Gift Certificates,

Telephone Cards, and Other Documents

3160.5 Engage in Transmitting Money

3165.1 Support Services—Printing and Selling MICR-Encoded Items

3170.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Insurance Agency Activities of Bank Holding

Companies

3180.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Insurance Underwriters

3190.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Courier Services

3200.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Management Consulting and Counseling

3202.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Employee Benefits Consulting Services

3204.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Career Counseling

3210.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Money Orders, Savings Bonds, and

Traveler’s Checks

3210.1 Payment Instruments

3220.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Arranging Commercial Real Estate Equity

Financing

3230.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Agency Transaction Services for Customer

Investments (Securities Brokerage)

3230.05 Securities Brokerage (Board Decisions)

3230.1 Securities Brokerage in Combination with Investment Advisory Services

3230.2 Securities Brokerage with Discretionary Investment Management and

Investment Advisory Services

3230.3 Offering Full Brokerage Services for Bank-Ineligible Securities

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 8

Sections Title

3230.4 Private-Placement and Riskless-Principal Activities

3230.5 Acting as a Municipal Securities Brokers’ Broker

3230.6 Acting as a Conduit in Securities Borrowing and Lending

3240.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Underwriting and Dealing in

U.S. Obligations, Municipal Securities, and Money Market Instruments

3250.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Agency Transactional Services

(Futures Commission Merchants and Futures Brokerage)

3251.0 4(c)(8) Agency Transactional Services—FCM Board Orders

3255.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Agency Transactional Services for

Customer Investments

3260.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Investment Transactions as Principal

3270.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Real Estate and Personal Property Appraising

3320.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Check-Guaranty and

Check-Verification Services

3330.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Operating a Collection Agency

3340.0 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Operating a Credit Bureau

3500.0 Prohibitions Against Tying Arrangements

3510.0 Sections 4(c)(9) and 2(h) of the BHC Act—Nonbanking Activities of Foreign

Banking Organizations

3520.0 Section 4(c)(10) of the BHC Act—Exemption from Section 4

for BHCs That Are Banks

3530.0 Section 4(c)(11) of the BHC Act—Authorization for BHCs to Reorganize

Share Ownership Held on the Basis of Any Section 4 Exemption

3540.0 Section 4(c)(12) of the BHC Act—Ten-Year Exemption from Section 4 of

the BHC Act

3550.0 Section 4(c)(13) of the BHC Act—International Activities of Bank Holding

Companies

3560.0 Section 4(c)(14) of the BHC Act—Export Trading Companies

3600.0 Permissible Activities by Board Order

3600.1 Operating a “Pool Reserve Plan”

3600.2–

3600.4

Reserved

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 9

Sections Title

3600.5 Engaging in Banking Activities via Foreign Branches

3600.6 Operating a Securities Exchange

3600.7 Acting as a Certification Authority for Digital Signatures

3600.8 Private Limited Investment Partnerships

3600.9–

3600.12

Reserved

3600.13 FCM Activities

3600.14–

3600.16

Reserved

3600.17 Insurance Activities

3600.18–

3600.20

Reserved

3600.21 Underwriting and Dealing

3600.22 Reserved

3600.23 Issuance and Sale of Mortgage-Backed Securities Guaranteed by GNMA

3600.24 Sales-Tax Refund Agent and Cashing U.S. Dollar Payroll Checks

3600.25 Providing Government Services

3600.26 Real Estate Settlement through a Permissible Title Insurance Agency

3600.27 Providing Administrative and Certain Other Services to Mutual Funds

3600.28 Developing Broader Marketing Plans and Advertising and Sales Literature for

Mutual Funds

3600.29 Providing Employment Histories to Third Parties

3600.30 Real Estate Title Abstracting

3610.1 Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Board Staff Legal Interpretation—Financing

Customers’ Commodity Purchase and Forward Sales

3610.2

Section 4(c)(8) of the BHC Act—Board Legal Staff Interpretation—Certain

Volumetric-Production-Payment Transactions Involving Physical Commodities

3700.0 Impermissible Activities

3700.1 Land Investment and Development

3700.2 Insurance Activities

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 10

Sections Title

3700.3 Real Estate Brokerage and Syndication

3700.4 General Management Consulting

3700.5 Property Management

3700.6 Travel Agencies

3700.7 Providing Credit Ratings on Bonds, Preferred Stock, and Commercial Paper

3700.8 Acting as a Specialist in Foreign-Currency Options on a Securities Exchange

3700.9 Design and Assembly of Hardware for Processing or Transmission of Banking

and Economic Data

3700.10 Armored Car Services

3700.11 Computer Output Microfilm Service

3700.12 Clearing Securities Options and Other Financial Instruments for the Accounts

of Professional Floor Traders

3900.0 Section 4(k) of the BHC Act—Financial Holding Companies

3901.0 U.S. Bank Holding Companies Operating as Financial Holding Companies

3903.0 Foreign Banks Operating as Financial Holding Companies

3905.0 Permissible Activities for FHCs

3906.0 Disease Management and Mail-Order Pharmacy Activities

3907.0 Merchant Banking

3909.0 Supervisory Guidance on Equity Investment and Merchant Banking Activities

(Section 4(k) of the BHC Act)

3910.0 Acting as a Finder

3912.0 To Acquire, Manage, and Operate Defined Benefit Pension Plans in the

United Kingdom (Section 4(k) of the BHC Act)

3920.0 Limited Physical-Commodity-Trading Activities

3950.0 Insurance Sales Activities and Consumer Protection in Sales of Insurance

3980.0 Establishment of an Intermediate Holding Company

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 11

Sections Title

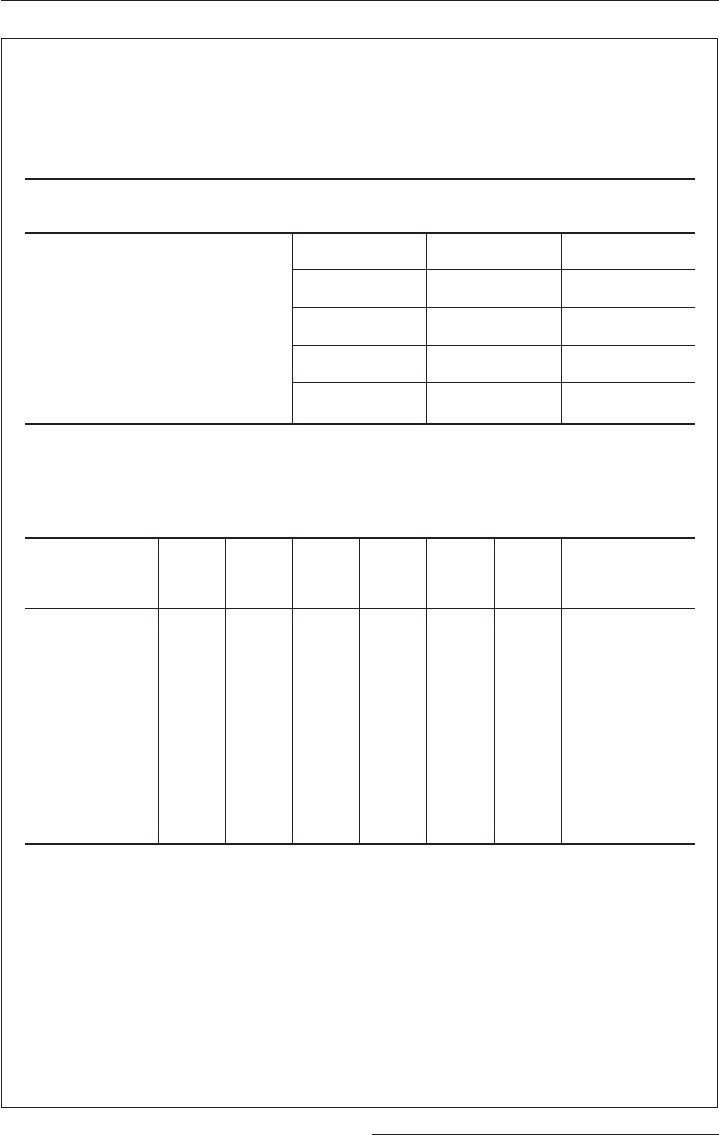

4000 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

4000.0 Financial Factors—Introduction

4010.0 Parent Only: Debt-Servicing Capacity—Cash Flow

4010.1 Leverage

4010.2 Liquidity

4020.0 Banks

4020.1 Banks: Capital

4020.2 Banks: Asset Quality

4020.3 Banks: Earnings

4020.4 Banks: Liquidity

4020.5 Banks: Summary Analysis

4020.6–

4020.8

Reserved

4020.9 Supervision Standards for De Novo State Member Banks of Bank Holding

Companies

4030.0 Nonbanks

4030.1 Nonbanks: Credit Extending—Classifications

4030.2 Nonbanks: Credit Extending—Earnings

4030.3 Nonbanks: Credit Extending—Leverage

4030.4 Nonbanks: Credit Extending—Reserves

4040.0 Nonbanks: Noncredit Extending

4050.0 Nonbanks: Noncredit Extending—Service Charters

4060.0 Consolidated—Earnings

4060.1 Consolidated: Asset Quality

4060.2–

4060.7

Reserved

4060.8 Overview of Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Programs

4060.9 Consolidated Capital Planning Processes—Payment of Dividends, Stock

Redemptions, and Stock Repurchases at Bank Holding Companies

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 12

Sections Title

4061.0–

4065.0

Reserved

4066.0 Consolidated—Funding and Liquidity Risk Management

4067.0–

4089.0

Reserved

4090.0 Country Risk

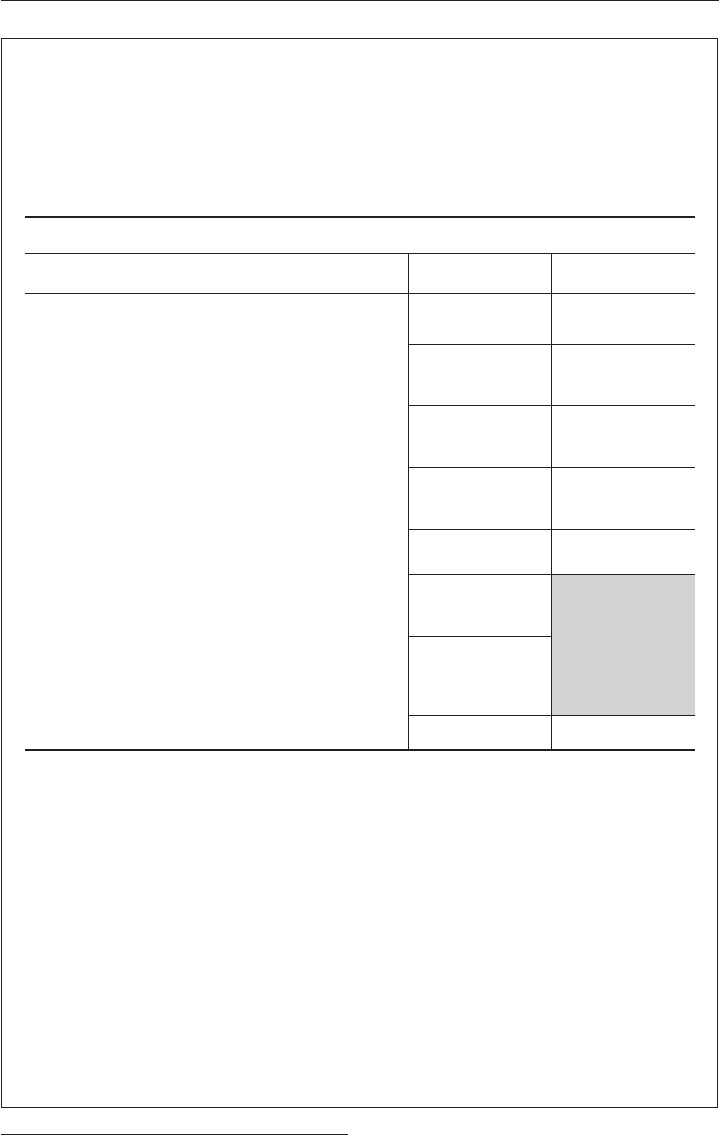

5000 BHC INSPECTION PROGRAM

5000.0 BHC Inspection Program—General

5010.0 Procedures for Inspection Report Preparation— Inspection Report References

5010.1 General Instructions to FR 1225

5010.2 Cover

5010.3 Page i—Table of Contents

5010.4 Core Page 1—Examiner’s Comments and Matters Requiring Special

Board Attention

5010.5 Core Page 2—Scope of Inspection and Abbreviations

5010.6 Core Page 3—Analysis of Financial Factors

5010.7 Core Page 4—Audit Program

5010.8 Appendix Page 5—Parent Company Comparative Balance Sheet

5010.9 Appendix Page 6—Comparative Statement of Income and Expenses (Parent)

5010.10 Appendix Page 7—Consolidated Classified and Special Mention Assets

5010.11 Appendix Page 8—Consolidated Comparative Balance Sheet

5010.12 Appendix Page 9—Comparative Consolidated Statement of Income and

Expenses

5010.13 Capital Structure

5010.14 Page—Policies and Supervision

5010.15 Page—Violations

5010.16 Page—Other Matters

5010.17 Page—Classified Assets and Capital Ratios of Subsidiary Banks

5010.18 Page—Organization Chart

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 13

Sections Title

5010.19 Page—History and Structure

5010.20 Page—Investment in and Advances to Subsidiaries

5010.21 Page—Commercial Paper (Parent)

5010.22 Page—Lines of Credit (Parent)

5010.23 Page—Questions on Commercial Paper and Lines of Credit (Parent)

5010.24 Page—Contingent Liabilities and Other Accounts

5010.25 Page—Statement of Changes in Stockholders’ Equity (Parent)

5010.26 Page—Income from Subsidiaries

5010.27 Page—Cash Flow Statement (Parent)

5010.28 Page—Parent Company Liquidity Position

5010.29 Page—Classified Parent Company and Nonbank Assets

5010.30 Page—Bank Subsidiaries

5010.31 Page—Nonbank Subsidiary

5010.32 Page—Nonbank Subsidiary Financial Statements

5010.33 Page—Fidelity and Other Indemnity Insurance

5010.34 Reserved

5010.35 Page—Other Supervisory Issues

5010.36 Page—Extensions of Credit to BHC Officials

5010.37 Page—Interest Rate Sensitivity—Assets and Liabilities

5010.38 Treasury Activities/Capital Markets

5010.39 Reserved

5010.40 Confidential Page A—Principal Officers and Directors

5010.41 Confidential Page B— Condition of BHC

5010.42 Confidential Page C—Liquidity and Debt Information

5010.43 Confidential Page D—Administrative and Other Matters

5020.1 Bank Subsidiary (FR 1241)

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 14

Sections Title

5020.2 Other Supervisory Issues (FR 1241)

5030.0 BHC Inspection Report Forms

5040.0 Procedures for “Limited-Scope” Inspection Report Preparation—

General Instructions

5050.0 Procedures for “Targeted” Inspection Report Preparation—General Instructions

5052.0 Targeted MIS Inspection

5060.0 Portions of Bank Holding Company Inspections Conducted in Federal Reserve

Bank Office

General Table of Contents

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 15

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual

Supplement 56—February 2023

This supplement reflects decisions of the Board

of Governors, new and revised statutory and

regulatory provisions, supervisory guidance, and

instructions that the Division of Supervision and

Regulation has issued since the publication of

the November 2021 supplement.

Section 1000.0, “About this Manual”

This section was revised to remove a reference

to SR letter 18-5/CA letter 18-7, “Interagency

Statement Clarifying Role of Supervisory Guid-

ance.” The Board codified the 2018 “Inter-

agency Statement Clarifying the Role of Super-

visory Guidance,” with clarifying changes, as

appendix A to 12 C.F.R. 262, “Statement Clari-

fying the Role of Supervisory Guidance.” The

final rule superseded the 2018 statement. See

86 Fed. Reg. 18,173 (April 8, 2021).

Section 1020.0, “Supervision of Savings

and Loan Holding Companies”

This new section contains guidance that was

previously in section 2500.0, “Supervision of

Savings and Loan Holding Companies.” The

material was moved closer to the manual’s other

sections that describe supervisory process guid-

ance. In addition, this section was modified to

provide an overview of the statutes, regulations,

and guidance that apply to savings and loan

holding companies (SLHCs). The section de-

scribes the supervisory approach for SLHCs,

highlighting that the Federal Reserve employs a

“portfolio approach” to consolidated supervi-

sion for most SLHCs to facilitate greater consis-

tency of supervisory practices and assessments

across comparable organizations. The section

describesthe ratings systems that apply to SLHCs.

The Federal Reserve uses the “RFI/C(D)” rating

system for non-insurance and non-commercial

SLHCs with total consolidated assets less than

$100 billion. The “Large Financial Institution”

or “LFI” rating system is used for all non-

insurance, non-commercial SLHCs with total

consolidated assets of $100 billion or more.

Supervisedinsuranceinstitutionsreceive a unique

rating. See 87 Fed. Reg. 60,160 (October 4,

2022). The section also describes guidance on

qualified thrift lenders (see SR-17-9, “Supervi-

sory Guidance for Examining Compliance with

the Qualified Thrift Lender Test”), as well as

covered savings associations (see SR-22-2, “Sta-

tus of Covered Savings Associations and Hold-

ing Companies of Covered Savings Associa-

tions Under Statutes and Regulations

Administered by the Federal Reserve”).

Section 1045.0, “Supervision of Holding

Companies with Less Than $10 Billion in

Total Consolidated Assets”

Previously, this section was called “Supervision

of Holding Companies with Total Consolidated

Assets of $10 Billion or Less.” The section’s

title and content have been revised to reflect

minor technical applicability changes. Previ-

ously, the guidance in the section applied to the

supervision of holding companies with $10 bil-

lion or less in total consolidated assets. The

section was revised to reflect that the guidance

applies to holding companies supervised by the

Federal Reserve with less than $10 billion in

total consolidated assets. For more information

see SR-13-21, “Inspection Frequency and Scope

Expectations for Bank Holding Companies and

Savings and Loan Holding Companies that are

Community Banking Organizations.”

Section 1060.20, “Liquidity Planning and

Positions (LFI Ratings System)

This new section provides an overview of key

liquidity-related regulations and guidance issu-

ances that apply to firms that are subject to the

large financial institution (LFI) rating system.

This section provides an overview of the “Inter-

agency Policy Statement on Funding and Liquid-

ity Risk Management” (see SR-10-6). The sec-

tion introduces key liquidity-related requirements

in Regulation YY, “Enhanced Prudential Stan-

dards” (12 C.F.R. part 252). Further, the section

describes the liquidity coverage ratio require-

ments and the net stable funding ratio require-

ments in Regulation WW, “Liquidity Risk Mea-

surement Standards” (12 C.F.R. part 249). The

liquidity regulatory requirements in the Com-

plex Institution Liquidity Monitoring Report

(FR 2052a) are summarized. The FR 2052a is

required to be submitted by top-tier BHCs, top-

tier SLHCs, and FBOs subject to Category I, II,

III, or IV standards under the Board’s Regula-

tion YY and Regulation LL. Lastly, the section

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 1

describestheFederalReserve’ssupervisoryactiv-

ities and approach for assessing liquidity at

LFIs.

Section 1063.0, “Holding Company

Ratings Applicability and Inspection

Frequency”

This section was revised to update the inspec-

tion scope and frequency expectations for super-

vised insurance organizations. A “supervised

insurance organization” is a depository institu-

tion holding company that is an insurance under-

writing company, or that has over 25 percent of

its consolidated assets held by insurance under-

writing subsidiaries or has been otherwise desig-

nated as a supervised insurance organization by

Federal Reserve staff. For more information on

the ratings system that applies to supervised

insurance organizations, see SR-22-8, “Frame-

work for the Supervision of Insurance Organiza-

tions.”

Section 1075.0, “Formal Corrective

Actions”

This new section contains guidance that was

previously in section 2110.0, “Formal Correc-

tive Actions.” The material was moved closer to

the manual’s other sections that describe super-

visory process guidance. The section was re-

vised to include the entities against which the

Federal Reserve has the statutory authority to

take formal enforcement actions. In particular,

the section was revised to indicate which formal

actions apply to SLHCs. Additional information

was added to describe enforcement actions for

Bank Secrecy Act and anti-money laundering

compliance failures, as well as the interagency

coordination activities of federal banking agen-

cies on formal enforcement actions. Clarifying

edits were made to the subsections describing

civil money penalties, prohibited indemnifica-

tion payments, and golden parachute payments,

as well as prohibition and removal authority.

The section highlights that the Board does not

issue an enforcement action on the basis of a

“violation” of or “non-compliance” with super-

visory guidance.

Section 2010.6, “Supervision of

Subsidiaries (Retail Sales of Nondeposit

Investment Products)”

Previously, this section was called “Supervision

of Subsidiaries (Financial Institution Subsidiary

Retail Sales of Nondeposit Investment Prod-

ucts).” The section’s title has been revised to

reflect the significant changes that were made to

the material. This section provides a summary

of the relevant guidance on nondeposit invest-

ment products and directs readers to the key

pieces of guidance, via hyperlinks, that the

Board and other banking agencies have issued

regarding this topic. The inspection objectives

and inspection procedures have been removed.

Relevant examination objectives and procedures

on the retail sales of nondeposit investment

products are in the Commercial Bank Examina-

tion Manual.

Section 2080.6, “Funding (Holding

Company Funding from Sweep

Accounts)”

Previously, this section was called “Funding

(Bank Holding Company Funding from Sweep

Accounts).” The section was renamed to reflect

that the guidance in this section applies to

SLHCs as well as bank holding companies

(BHCs). The section was revised to reflect the

expanded applicability of the guidance. Further,

the section was revised to better align with the

“Statement Clarifying the Role of Supervisory

Guidance” (see 12 C.F.R. part 262, appendix A).

Unlike a law or regulation, supervisory guid-

ance does not have the force and effect of law,

and the Board does not take enforcement actions

based on supervisory guidance.

Section 2090.2 “Control and Ownership

(BHC Formations)”

This section contains information about the Small

Bank Holding Company and Savings and Loan

Holding Company Policy Statement (12 C.F.R.

part 225, appendix C). Additional information

was added to explain the calculation of equity,

the denominator of the debt-to-equity ratio, as

described in this policy statement. The compo-

nents of total equity capital align with the com-

ponents of equity that are listed in the Parent

Company Only Financial Statements for Small

Holding Companies Report (FR-Y-9SP). Total

equity capital includes perpetual preferred stock

(including related surplus); common stock

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 56—February 2023

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 2

(including related surplus); retained earnings;

accumulated other comprehensive income; and

all other equity capital components, including

the total carrying value (at cost) of treasury

stock and unearned Employee Stock Ownership

Plan shares.

Section 2110.0, “Formal Corrective

Actions”

The material in this section has been revised and

moved to section 1075.0. As a result, this sec-

tion has been removed from the manual. See the

description above for section 1075.0 for more

information.

Section 2128.02 Asset Securitization (Risk

Management and Internal Controls)

This section was significantly revised. Much of

the information that was previously in the sec-

tion was removed because it conveyed outdated

risk-based capital provisions affecting asset se-

curitization, as well as outdated accounting ref-

erences. The section refers readers to the Asset

Securitization section of the Commercial Bank

Examination Manual for more information. The

inspection objectives and inspection procedures

also were removed, as the Securitization Exami-

nation Documentation (ED) module provides

more detailed examination procedures for exam-

iners.

Section 2241.0, “Retail-Credit

Classification”

This section was revised to reflect that the guid-

ance in this section applies to BHCs as well as

SLHCs. Outdated references were removed from

the section. Minor edits were made to the defini-

tions for the classifications used for retail credit:

Substandard, Doubtful, and Loss. Edits were

made to these definitions to ensure they align

with the definitions that the federal bank regula-

tory agencies utilize for assets adversely classi-

fied for supervisory purposes. Further, edits

were made to better align the guidance in the

manual section with the “Statement Clarifying

the Role of Supervisory Guidance.”

Section 2500.0, “Supervision of Savings

and Loan Holding Companies”

The material in this section has been revised and

moved to section 1020.0. As a result, this

section has been removed from the manual. See

the description above for section 1020.0 for

more information.

Section 3520.0, “Section 4(c)(10) of the

BHC Act (Exemption from Section 4 for

BHCs That Are Banks)”

This section, previously called “Section 4(c)(10)

of the BHC Act (Grandfather Exemption from

Section 4 for BHC’s Which Are Banks)” was

revised to note that at the time of the enactment

of the BHC Act, the exemption described in the

section accommodated only three BHCs and

that these BHCs no longer exist. The section

remains in the manual to provide historical

background information.

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 56—February 2023

BHC Supervision Manual February 2023

Page 3

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual

Supplement 55—November 2021

This supplement reflects decisions of the Board

of Governors, new and revised statutory and

regulatory provisions, supervisory guidance, and

instructions that the Division of Supervision and

Regulation has issued since the publication of

the February 2020 supplement.

Section 1050.2, “Consolidated

Supervision of Regional Holding

Companies”

This section was previously called “Guidance

for the Consolidated Supervision of Regional

Bank Holding Companies.” The section was

revised to note that it applies to domestic bank

holding companies (BHCs) and savings and

loan holding companies (SLHCs) having between

$10 billion and $100 billion in total consoli-

dated assets. Several discussions regarding super-

visory findings were modified to align more

closely with the “Statement Clarifying the Role

of Supervisory Guidance” (12 CFR part 262,

appendix A). Further, this section was revised to

include an outline of the report of inspection

that examiners should follow when assigning

holding company rating components and sub-

components at full-scope or roll-up inspections

of BHCs and SLHCs in the regional banking

organization portfolio. The section explains the

timing expectations for examination staff to

complete safety-and-soundness examination and

inspection reports for domestic regional finan-

cial institutions and the submission of the re-

ports to the institution. Lastly, references to

inactive guidance issuances were updated.

Section 1060.1, “Large Financial

Institution Rating System: Capital

Planning and Positions”

This new section provides an overview of key

capital-related regulations and guidance issu-

ances that apply to firms that are subject to the

large financial institution (LFI) rating system.

The section describes capital stress testing re-

quirements for BHCs and covered SLHCs with

total consolidated assets of $100 billion or more

(Regulation YY and Regulation LL). The sec-

tion also contains an overview of Regulation Q,

which establishes minimum capital require-

ments and overall capital adequacy standards

for Federal Reserve-regulated institutions. A

fuller discussion of Regulation Q is provided in

the “Assessment of Capital Adequacy” section

of the Commercial Bank Examination Manual.

In addition, the section describes the applicabil-

ity and purpose of the capital plan rule (Regula-

tion Y and Regulation LL), which requires an

LFI to develop an annual capital plan that is

approved by its board of directors. This section

contains updated information that was previ-

ously discussed in section 4060.5, “Capital Ad-

equacy (Advanced Approaches)” and sec-

tion 4061.0, “Consolidated Capital (Capital

Planning).”

Section 1060.2, “Supervisory Assessment

of Capital Planning and Positions for

Category I Firms”

This new section contains guidance that was

previously in section 4063.0, “Federal Reserve

Supervisory Assessment of Capital Planning and

Positions for LISCC Firms and Large and Com-

plex Firms.” This material was moved closer to

the other sections in the manual that provide

guidance on the assessment of capital planning

and positions at LFIs. Further, this section was

modified to cover U.S. BHCs that are subject to

category I standards under the Board’s tailoring

framework. These applicability modifications

align with the Board’s tailoring rules. See 84

Fed. Reg. 59,032 (November 1, 2019) for more

information. See also SR-15-18, “Federal Reserve

Supervisory Assessment of Capital Planning and

Positions for Firms Subject to Category I Stan-

dards.”

Section 1060.3, “Supervisory Assessment

of Capital Planning and Positions for

Category II or III Firms”

This new section contains guidance that was

previously in section 4065.0, “Federal Reserve

Supervisory Assessment of Capital Planning and

Positions for Large and Noncomplex Firms.”

The material was moved closer to the other

sections in the manual that provide guidance on

the assessment of capital planning and positions

at LFIs. Further, this section was modified to

cover U.S. BHCs, U.S. intermediate holding

companies of foreign banking organizations,

and covered SLHCs that are subject to cate-

gory II or III standards under the Board’s tailor-

ing framework. These applicability modifica-

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 1

tions align with the Board’s tailoring rules. See

84 Fed. Reg. 59,032 (November 1, 2019); and

SR-15-19, “Federal Reserve Supervisory Assess-

ment of Capital Planning and Positions for Firms

Subject to Category II or III Standards.”

Section 1060.30, “Supervisory Guidance

on Board of Directors’ Effectiveness

(Governance and Controls)”

This new section is based on SR-21-3/CA-21-1,

“Supervisory Guidance on Board of Directors’

Effectiveness.” The guidance in this section

explains key attributes of effective boards at

BHCs and SLHCs that are LFIs. Specifically,

this guidance notes that boards of directors at

LFIs should: (1) set clear, aligned and consistent

direction regarding the firm’s strategy and risk

appetite; (2) direct senior management regard-

ing the board’s information needs; (3) oversee

and hold senior management accountable; (4)

support the independence and stature of inde-

pendent risk management and internal audit;

and (5) maintain a capable board composition

and governance structure. The section also pro-

vides an explanation of supervisory consider-

ations in assessing board effectiveness as part of

the LFI rating system.

Section 1060.31, “Assessment of

Risk-Management Processes and Internal

Controls of BHCs Having $100 Billion or

More in Total Assets”

This new section was previously section 4070.1.

The material was moved closer to the manual’s

sections on the assignment of ratings for hold-

ing companies subject to the LFI rating system.

The section was revised to cover the supervision

of BHCs having $100 billion or more in total

consolidated assets. Further, this section was

updated to reflect the Federal Reserve’s guid-

ance for boards of directors in SR-21-3/CA-21-1,

“Supervisory Guidance on Board of Directors’

Effectiveness.” Specifically, the section was re-

vised to better reflect the roles and responsibili-

ties of the board of directors and the roles and

responsibilities of senior management.

Section 1062.1, “Supervisory Guidance

for Assessing Risk Management at

Supervised Institutions with Total

Consolidated Assets Less than

$100 Billion”

This new section was previously section 4071.0.

The material in this section was moved closer to

the manual’s sections on the assignment of rat-

ings for holding companies with less than

$100 billion in assets (RFI/C(D) rating system).

In addition, the section was revised to cover the

supervision of Federal Reserve-regulated insti-

tutions with total consolidated assets of less

than $100 billion, including state member banks,

BHCs, and SLHCs (including insurance and

commercial SLHCs); as well as foreign banking

organizations with consolidated U.S. assets of

less than $100 billion. Previously, the guidance

in the section generally applied to the supervi-

sion of Federal Reserve-regulated institutions

with total consolidated assets of less than

$50 billion. Outdated references to SR letters

also were removed from the section. See

SR-16-11, “Supervisory Guidance for Assess-

ing Risk Management at Supervised Institutions

with Total Consolidated Assets Less than

$100 billion.”

Section 1070.1, “Communication of

Supervisory Findings”

This section was revised to include a reference

to the “Statement Clarifying the Role of Super-

visory Guidance.” This statement, as codified in

12 CFR part 262, implements a September 2018

statementclarifyingthe differences between regu-

lation and guidance. Unlike a law or regulation,

supervisory guidance does not have the force

and effect of law, and the Board does not take

enforcement actions based on supervisory guid-

ance. Rather, guidance outlines expectations and

priorities, or articulates views regarding appro-

priate practices for a specific subject. See 12 CFR

part 262, appendix A; 86 Fed. Reg. 18,179,

(April 8, 2021).

Section 1072.0, “Considerations in

Assigning and Revising Supervisory

Ratings”

This new section was previously section 4070.3,

“Revising Supervisory Ratings.” The material

was moved closer to the other sections in the

manual covering aspects of the Federal Reserve’s

supervisory process. The section was revised to

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 55—November 2021

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 2

describe considerations for upgrading supervi-

sory ratings at community banking organizations.

See SR-12-4, “Upgrades of Supervisory Ratings

for Banking Organizations with $10 Billion or

Less in Total Consolidated Assets.” In addition,

the section describes how examinersprovidetimely

and accurate assessments of larger holding com-

pany through the LFI rating system.

Section 1080.0, “Federal Reserve System

Holding Company Surveillance Program”

This section was formerly section 4080.0, “Fed-

eral Reserve System BHC Surveillance Pro-

gram.” The material was moved to be closer to

the other sections in the manual covering as-

pects of the Federal Reserve’s supervisory pro-

cess. Minor technical edits were made to the

section.

Section 1080.1, “Surveillance Program

for Small Holding Companies”

This section was formerly section 4080.1, “Sur-

veillance Program for Small Holding Compa-

nies.” The material was moved closer to the

other sections in the manual covering aspects of

the Federal Reserve’s supervisory process. Mi-

nor technical edits were made to the section.

Section 2010.12, “Fees Involving

Investments of Fiduciary Assets in Mutual

Funds and Potential Conflicts of Interest”

This section was updated to reflect the Federal

Reserve’s guidance for boards of directors in

SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory Guidance on

Boardof Directors’Effectiveness,” and

SR-16-11,

“Supervisory Guidance for Assessing Risk Man-

agement at Supervised Institutions with Total

Consolidated Assets Less than $100 Billion.”

Specifically, the section was revised to better

reflect the roles and responsibilities of the board

of directors and the roles and responsibilities of

senior management with regards to this activity.

Section 2065.2, “Maintaining and

Documenting the Allowance for Loan and

Lease Losses”

Section 2065.2, “Determining an Adequate Level

for the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses

(Accounting, Reporting, and Disclosure Issues),”

was renamed “Maintaining and Documenting

the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses.”

Section 2065.2 was modified to summarize the

contents of the following manual sections, which

were based on several SR letters:

• Section 2065.3, “Maintenance of an Appropri-

ate Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses

(Accounting, Reporting, and Disclosure

Issues)” (See SR-06-17);

• Section 2065.4, “ALLL Methodologies and

Documentation (Accounting, Reporting, and

Disclosure Issues)” (See SR-01-17); and

• Section 2065.5, “ALLL Estimation Practices

for Loans Secured by Junior Liens” (See

SR-12-3)

As a result of the changes to section 2065.2,

sections 2065.4, and 2065.5 have been removed

from the manual. Section 2065.3 “Maintenance

of an Appropriate Allowance for Loan and

Lease Losses (Accounting, Reporting, and Dis-

closure Issues),” has been replaced with entirely

newcontenton the “Allowance for Credit Losses.”

In addition, references to the 2020 interagency

guidance on credit-risk review systems were

added to section 2065.2. See SR-20-13, “Inter-

agency Guidance on Credit Risk Review Sys-

tems.”

Section 2065.3, “Allowance for Credit

Losses”

This new section provides an overview of the

Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB)

Accounting Standards Update No. 2016-13,

Financial Instruments—Credit Losses

(Topic 326): Measurement of Credit Losses on

Financial Instruments. The section highlights

the Interagency Policy Statement on Allow-

ances for Credit Losses,” which was issued by

the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller

of the Currency, Federal Deposit Insurance Cor-

poration, and National Credit Union Adminis-

tration. (See SR-20-12.) The statement describes

the measurement of expected credit losses under

the current expected credit losses (CECL) meth-

odology and the accounting for impairment on

available-for-sale debt securities in accordance

with FASB Accounting Standards Codification

Topic 326; the design, documentation, and vali-

dation of expected credit loss estimation pro-

cesses, including the internal controls over these

processes; the maintenance of appropriate allow-

ances for credit losses (ACLs); the responsibili-

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 55—November 2021

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 3

ties of boards of directors and management; and

examiners’ review of a bank’s ACLs. The sec-

tion also explains the Board’s rules providing

institutions the option to phase in the day-one

adverse effects on regulatory capital that may

result transitioning from the incurred loss meth-

odology to the CECL methodology.

Section 2065.4, “ALLL Methodologies

and Documentation (Accounting,

Reporting, and Disclosure Issues)”

This section has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 2065.2 for

more information on the removal of this section

from the manual.

Section 2065.5, “ALLL Estimation

Practices for Loans Secured by Junior

Liens”

This section has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 2065.2 for

more information on the removal of this section

from the manual.

Section 2090.0, “Control and Ownership

(General)”

This section was revised to provide an overview

of the concept of control as it is applied by the

Federal Reserve under the relevant banking and

savings and loan-related statutes. The section

was revised to include key concepts from a final

rule that the Board issued in 2020 on control

and divesture proceedings. See 85 Fed.

Reg. 12,398 (March 2, 2020).

Section 2122.0, “Internal Credit-Risk

Ratings at Large Firms”

This section was renamed and updated to reflect

the Federal Reserve’s guidance for boards of

directors in SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory

Guidance on Board of Directors’ Effectiveness,”

and SR-16-11, “Supervisory Guidance for As-

sessing Risk Management at Supervised Institu-

tions with Total Consolidated Assets Less than

$100 Billion.” Specifically, the section was re-

vised to better reflect the roles and responsibili-

ties of the board of directors and the roles and

responsibilities of senior management with re-

gards to this activity. Outdated guidance refer-

ences in the section were updated. In addition,

the inspection objectives and procedures were

removed.

Section 2124.01, “Risk-Focused

Supervision Framework for Large

Complex Banking Organizations”

Section 2124.01 was removed from the manual

as SR-97-24, “Risk-Focused Framework for Su-

pervision of Large Complex Institutions,” has

been made inactive. Refer to SR-21-4/CA-21-2,

“Inactive or Revised SR Letters Related to the

Federal Reserve’s Supervisory Expectations for

a Firm’s Boards of Directors.”

Section 2124.07, “Compliance

Risk-Management Programs and

Oversight at Large Firms”

This section was renamed and updated to reflect

the Federal Reserve’s guidance for boards of

directors in SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory

Guidance on Board of Directors’ Effectiveness,”

and SR-16-11, “Supervisory Guidance for As-

sessing Risk Management at Supervised Institu-

tions with Total Consolidated Assets Less than

$100 Billion.” Specifically, the section was re-

vised to better reflect the roles and responsibili-

ties of the board of directors and the roles and

responsibilities of senior management with re-

gards to implementing compliance risk-

management programs.

Section 2124.1, “Assessment of

Information Technology in Risk-Focused

Supervision”

This section was updated to reflect the Federal

Reserve’s guidance for boards of directors in

SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory Guidance on

BoardofDirectors’ Effectiveness,” and SR-16-11,

“Supervisory Guidance for Assessing Risk Man-

agement at Supervised Institutions with Total

Consolidated Assets Less than $100 Billion.”

Specifically, the section was revised to better

reflect the roles and responsibilities of the board

of directors and the roles and responsibilities of

senior management with regards to institutions’

use of information technology. Outdated refer-

ences to information technology tools or pro-

cesses were removed. Further, the inspection

objectives and inspection procedures were

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 55—November 2021

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 4

removed from the section. More information on

inspection objectives and procedures is pro-

vided in the FFIEC IT Examination Handbook.

Section 2124.3, “Managing Outsourcing

Risk”

This section was updated to reflect the Federal

Reserve’s guidance for boards of directors in

SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory Guidance on

BoardofDirectors’ Effectiveness,” and SR-16-11,

“Supervisory Guidance for Assessing Risk Man-

agement at Supervised Institutions with Total

Consolidated Assets Less than $100 Billion.”

Specifically, the section was revised to better

reflect the roles and responsibilities of the board

of directors and the roles and responsibilities of

senior management with regards to outsourcing

risk.

Section 2125.0, Trading Activities of

Banking Organizations (Risk Management

and Internal Controls)

Section 2125.0 was removed from the manual

as SR-93-69, “Examining Risk Management

and Internal Controls for Trading Activities of

Banking Organizations,” has been made inac-

tive. Refer to SR-21-4/CA-21-2, “Inactive or

Revised SR Letters Related to the Federal

Reserve’s Supervisory Expectations for a Firm’s

Boards of Directors.”

Section 2126.5, “Volcker Rule (Section 13

of the Bank Holding Company Act)”

This section’s title was revised from “Proce-

dures for a Banking Entity to Request an Extended

Transition Period for Illiquid Funds.” Further,

the section was revised to provide an overview

of section 13 to the Bank Holding Company Act

of 1956 (BHC Act), commonly referred to as

the Volcker rule. The Volcker rule generally

prohibits any banking entity from engaging in

proprietary trading or from acquiring or retain-

ing an ownership interest in, sponsoring, or hav-

ing certain relationships with a hedge fund or

private equity fund, subject to certain exemp-

tions. The section provides background informa-

tion on the applicability of the Volcker rule, as

well as Regulation VV, which implements the

Volcker rule. The section retained salient infor-

mation related to the procedures that institutions

could follow to request an extended transition

period for illiquid funds.

Section 2129.05, “Risk and Capital

Management—Secondary-Market Credit

Activities (Risk Management and Internal

Controls)”

This section was updated to reflect the Federal

Reserve’s guidance for boards of directors in

SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory Guidance on

Board of Directors’ Effectiveness,” and SR-16-11,

“Supervisory Guidance for Assessing Risk Man-

agement at Supervised Institutions with Total

Consolidated Assets Less than $100 Billion.”

The material related to SR-97-21, “Risk Man-

agement and Capital Adequacy of Exposures

Arising from Secondary Market Credit Activi-

ties,” was removed from the section as this letter

was made inactive. Refer to SR-21-4/CA-21-2,

“Inactive or Revised SR Letters Related to the

Federal Reserve’s Supervisory Expectations for

a Firm’s Boards of Directors.” SR-21-4/CA-

21-2 notes that the expectations related to the

responsibilities of board of directors will be

revised in the Bank Holding Company Supervi-

sion Manual to be consistent with the guidance

in SR-21-3/CA-21-1 as well as SR-16-11.

Section 3500.0, “Prohibitions Against

Tying Arrangements”

This section was revised to provide an overview

of section 106 of the BHC Act amendments

of 1970 (section 106). Section 106, as imple-

mented by the Federal Reserve Board’s Regula-

tion Y (12 CFR part 225), prohibits a bank from

conditioning the availability or price of one

product on a requirement that the customer also

obtain another product from the bank or an

affiliate of the bank. The statute is intended to

prevent banks from using their ability to offer

bank products in a coercive manner to gain a

competitive advantage in markets for other prod-

ucts and services. Several legal interpretations

about the applicationof section 106 were removed

from the section because legal interpretations

are available on the Board’s public website. The

inspection objectives and inspections procedures

were updated.

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 55—November 2021

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 5

Section 3909.0, “Supervisory Guidance

on Equity Investment and Merchant

Banking Activities (Section 4(k) of the

BHC Act)”

This section was updated to reflect the Federal

Reserve’s guidance for boards of directors in

SR-21-3/CA-21-1, “Supervisory Guidance on

BoardofDirectors’ Effectiveness,” and SR-16-11,

“Supervisory Guidance for Assessing Risk Man-

agement at Supervised Institutions with Total

Consolidated Assets Less than $100 Billion.”

Specifically, the section was revised to better

reflect the roles and responsibilities of the board

of directors and the roles and responsibilities of

senior management with regards to this activity.

Section 4020.9, “Supervision Standards

for De Novo State Member Banks of Bank

Holding Companies”

This section was revised to incorporate updated

guidance on the supervision program for de

novo state member banks. The section was

revised to explain that a state member bank is

considered to be in the de novo stage until it has

been operating for at least three years. In addi-

tion, the section was updated to note that as a

condition of membership, the Federal Reserve

typically requires each de novo to maintain a

tier 1 leverage ratio of at least 8 percent for the

first three years of its existence. See SR-20-16,

“Supervision of De Novo State Member Banks.”

Section 4060.3, “Consolidated Capital

(Examiners’ Guidelines for Assessing the

Capital Adequacy of BHCs)”

Section 4060.3 has been removed from the

manual. This section contained outdated infor-

mation describing the capital adequacy guide-

lines for BHCs that was previously found in

appendix A to Regulation Y (12 CFR part 225).

Supervised institutions should refer to the Board’s

capital rule (12 CFR part 217 or Regulation Q)

and the Small Bank Holding Company and Sav-

ings and Loan Holding Company Policy State-

ment (12 CFR part 225, appendix C). For more

information on Regulation Q, see the Commer-

cial Bank Examination Manual’s section en-

titled, “Assessment of Capital Adequacy.” For

more information on the Small Bank Holding

Company and Savings and Loan Holding Com-

pany Policy Statement, see this manual’s sec-

tion 2090.2, “Control and Ownership (BHC For-

mations).”

Section 4060.5, “Capital Adequacy

(Advanced Approaches)”

Section 4060.5 has been removed from the

manual. This section described the advanced

approaches framework, which provides a risk-

based capital framework that requires some

bank holding companies to use an internal ratings-

based approach to calculate credit-risk capital

requirements and advanced measurement ap-

proaches in order to calculate regulatory

operational-risk capital requirements. The rel-

evant information on the advanced approaches

framework is located in section 1060.1, “Large

Financial Institution Rating System: Capital Plan-

ning and Positions,” in the subsection entitled,

“Regulation Q (12 CFR 217): Capital Posi-

tions.” For more information on the advanced

approaches framework see 12 CFR part 217,

subpart E, as well as the Basel Coordination

Committee Bulletins on the

Board’s public

website

.

Section 4061.0, “Consolidated Capital

(Capital Planning)”

Section 4061.0 has been removed from the

manual. Relevant guidance on the capital plan

rule (12 CFR 225.8) is in section 1060.1, “Large

Financial Institution Rating System: Capital Plan-

ning and Positions,” in the subsection entitled,

“Regulation Y: Capital Plan Rule and Stress

Capital Buffer.” Section 1060.1 explains the

purpose of a firm’s capital plan; the applicabil-

ity of the rule; and the mandatory elements of a

capital plan. The tailored capital plan rule sets

forth requirements for firms that are subject to

category IV standards.

Section 4063.0, “Federal Reserve

Supervisory Assessment of Capital

Planning and Positions for LISCC Firms

and Large and Complex Firms”

This section has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 1060.2 for

more information on the removal of this section

from the manual.

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 55—November 2021

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 6

Section 4065.0, “Federal Reserve

Supervisory Assessment of Capital

Planning and Positions for Large and

Noncomplex Firms”

This section has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 1060.3 for

more information on the removal of this section

from the manual.

Section 4070.1, “Rating

Risk-Management Processes and Internal

Controls of BHCs Having $50 Billion or

More in Total Assets”

This section has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 1060.31

for more information on the removal of this

section from the manual.

Section 4070.3, “Revising Supervisory

Ratings”

The content of this section was revised and

moved to section 1072.0, “Considerations in

Assigning and Revising Supervisory Ratings.”

As a result, this section has been removed from

the manual. See the description above for sec-

tion 1072.0 for more information.

Section 4071.0, “Supervisory Guidance for

Assessing Risk Management at Supervised

Institutions with Total Consolidated Assets

Less than $50 Billion”

This section has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 1062.1 for

more information on the removal of this section

from the manual.

Section 4080.0, “Federal Reserve System

BHC Surveillance Program”

The material in this section has been moved to

section 1080.0. As a result, this section has been

removed from the manual. See the description

above for section 1080.0 for more information.

Section 4080.1, “Surveillance Program

for Small Holding Companies”

The material in this section was moved to sec-

tion 1080.1. As a result, this section has been

removed from the manual. See the description

above for section 1080.1 for more information.

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 55—November 2021

BHC Supervision Manual November 2021

Page 7

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual

Supplement 54—February 2020

This supplement reflects decisions of the Board

of Governors, new and revised statutory and

regulatory provisions, supervisory guidance, and

instructions that the Division of Supervision and

Regulation has issued since the publication of

the February 2019 supplement.

Section 1045.0

The contents of this new section, “Supervision

of Holding Companies with Total Consolidated

Assets of $10 Billion or Less,” were previously

in this manual’s section 5000.0, “BHC Inspec-

tion Program (General).” A standalone section

was developed to help clarify the supervisory

program for smaller holding companies. The

content of the section was revised to modify

inspection frequency and scope expectations for

holding companies with total consolidated assets

between $1 billion and $3 billion. The inspec-

tion frequency and scope expectations were

modified for this population of holding compa-

nies to align with updated statutory require-

ments as authorized by the Economic Growth,

Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection

Act. References were also updated to reflect that

non-commercial and non-insurance savings and

loan holding companies (SLHCs) are assigned

RFI ratings, effective February 1, 2019. See

SR-13-21, “Inspection Frequency and Scope

Requirements for Bank Holding Companies and

Savings and Loan Holding Companies with

Total Consolidated Assets of $10 Billion or

Less.”

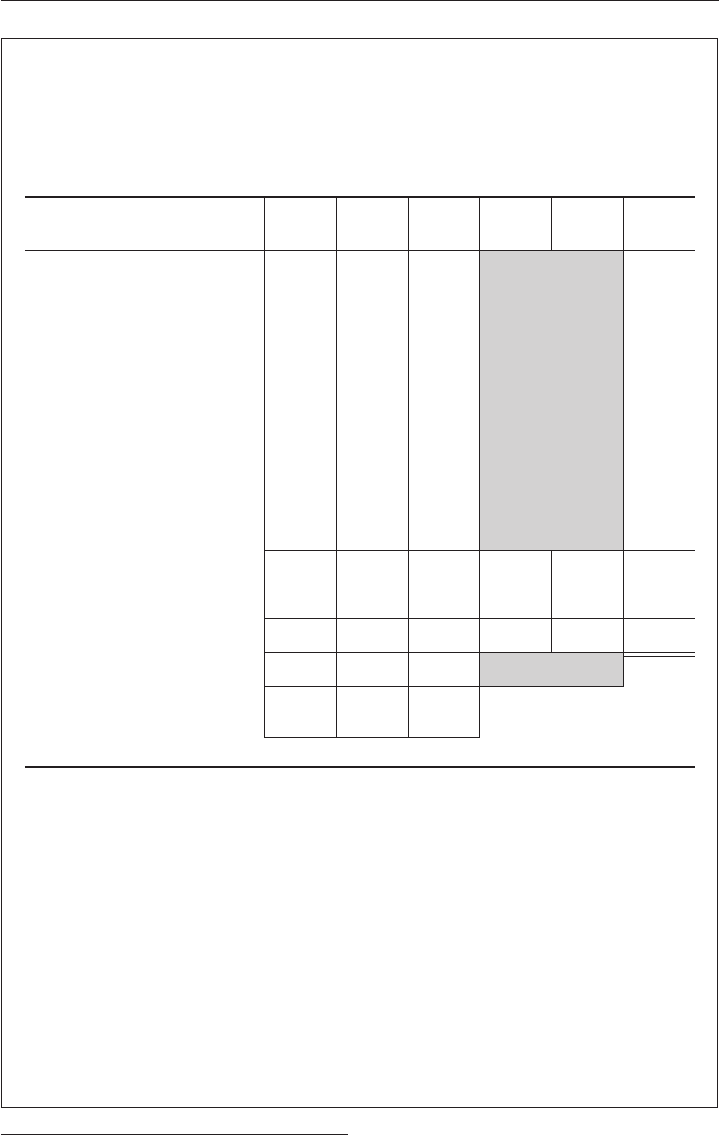

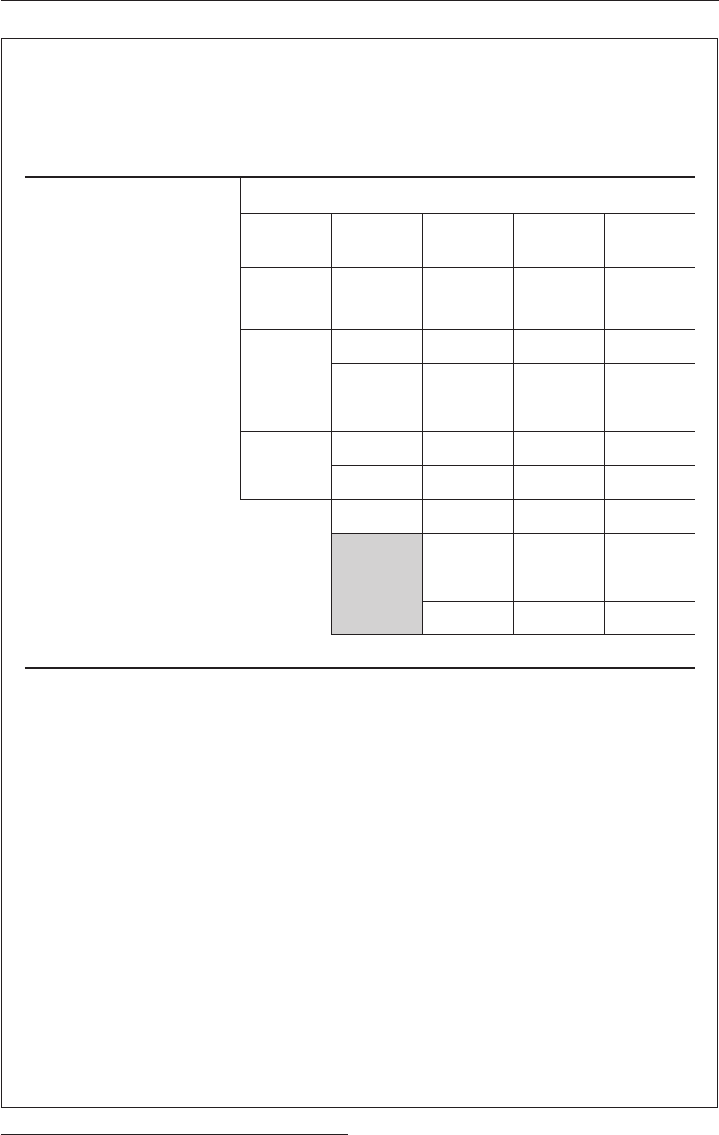

Section 1063.0

This new section, “Holding Company Ratings

Applicability and Inspection Frequency,” pro-

vides an overview of the inspection scope and

frequency expectations for bank holding compa-

nies (BHCs) and SLHCs supervised by the Fed-

eral Reserve. The section explains the applica-

bility of the two rating systems Federal Reserve

examiners use to assess the condition of BHCs

and SLHCs. The section also provides a table

illustrating the inspection scope and frequency

expectations for holding companies with less

than $10 billion in assets, which is described in

more detail in section 1045.0. See also SR-19-4/

CA-19-3, “Supervisory Rating System for

Holding Companies with Total Consolidated

Assets Less Than $100 billion”; SR-19-3/

CA-19-2, “Large Financial Institution (LFI) Rat-

ing System”; and SR-13-21.

Section 1065.0

This new section, “Nondisclosure of Supervi-

sory Ratings and Confidential Supervisory Infor-

mation,” was previously section 4070.5. The

section was moved to section 1065.0 so it would

be located closer to the manual’s sections on the

assignment of ratings for holding companies. In

addition, the section was revised to reference

the large financial institution (LFI) rating sys-

tem as another example of confidential supervi-

sory information. Superfluous historical back-

ground informationwasremoved from thesection.

In addition, outdated references to the Office of

Thrift Supervision and their holding company

rating system were removed from the section.

Section 1070.1

The content of this new section was previously

part of section 5000.0, “BHC Inspection Pro-

gram (General).” The content of section 1070.1

primarily is based on the guidance in SR-13-13/

CA-13-10, “Supervisory Considerations for the

Communication of Supervisory Findings.” Sec-

tion 1070.1 highlights that examiners should

convey, if evident, both the root cause of the

finding and the potential effect of the finding on

the organization. The section also includes a

reference to SR-18-5/CA-18-7, “Interagency

Statement Clarifying the Role of Supervisory

Guidance,” which examiners should also con-

sider when communicating supervisory find-

ings. Lastly, the section describes key factors

examiners shouldconsider in determiningwhether

to recommend additional formal or informal

investigation or enforcement action for a hold-

ing company.

Section 2231.0

Section 2231.0, “Real Estate Appraisals and

Evaluations,” has been revised significantly. This

section provides a brief summary of the Board’s

appraisal regulations and directs readers to the

key pieces of guidance that the Board and other

banking agencies have issued relating to real

BHC Supervision Manual February 2020

Page 1

estate appraisals and evaluations. Previously, the

section contained the entire contents of the

December 2010 “Interagency Appraisal and

Evaluation Guidelines.” The revised manual

section includes a brief summary of the Decem-

ber 2010 Interagency Appraisal and Evaluation

Guidelines, as well as a hyperlink to the guide-

lines. (See SR-10-16.)

Section 4060.4

Section 4060.4, “Consolidated Capital (Tier 1

Leverage Measure),” has been removed from

the manual. The section was outdated and based

on regulations that no longer exist. For more

information on the leverage ratio, including

leverage ratio components and requirements, see

the Board’s Regulation Q (12 CFR part 217). In

addition, the instructions to the FR Y-9C, “Con-

solidated Financial Statements for Holding Com-

panies,” (Schedule HC-R) outline the reporting

requirements for the leverage capital ratios.

Section 4070.5

This section, “Nondisclosure of Supervisory

Ratings,” has been removed from the manual.

See the description above for section 1065.0 for

more information on the removal of this section

from the manual.

Section 4080.1

This section, “Surveillance Program for Small

Holding Companies,” was modified to alter the

applicability of the Federal Reserve’s surveil-

lance program for holding companies. The small

holding company surveillance program covers

holding companies having total consolidated

assets of less than $3 billion. Previously, the

program covered holding companies having to-

tal consolidated assets of less than $1 billion.

(See SR-13-21.)

Section 5000.0

Section 5000.0, “BHC Inspection Program (Gen-

eral),” has been revised significantly and is now

focused on the coordination of holding com-

pany supervisory activities. Much of the rel-

evant content in section 5000.0 was moved to

other sections to improve the manual’s organi-

zation. More specifically, information related to

the supervision of holding companies with total

consolidated assets $10 billion or less was

removed, revised, and incorporated into sec-

tion 1045.1 of the manual. The section’s content

related to the communication of supervisory

findings was removed and incorporated into sec-

tion 1070.1 of the manual. In addition, outdated

content on the frequency and scope of holding

company inspections was removed from this

section. Section 1063.0 contains consolidated

and updated inspection frequency and scope

expectations for holding companies.

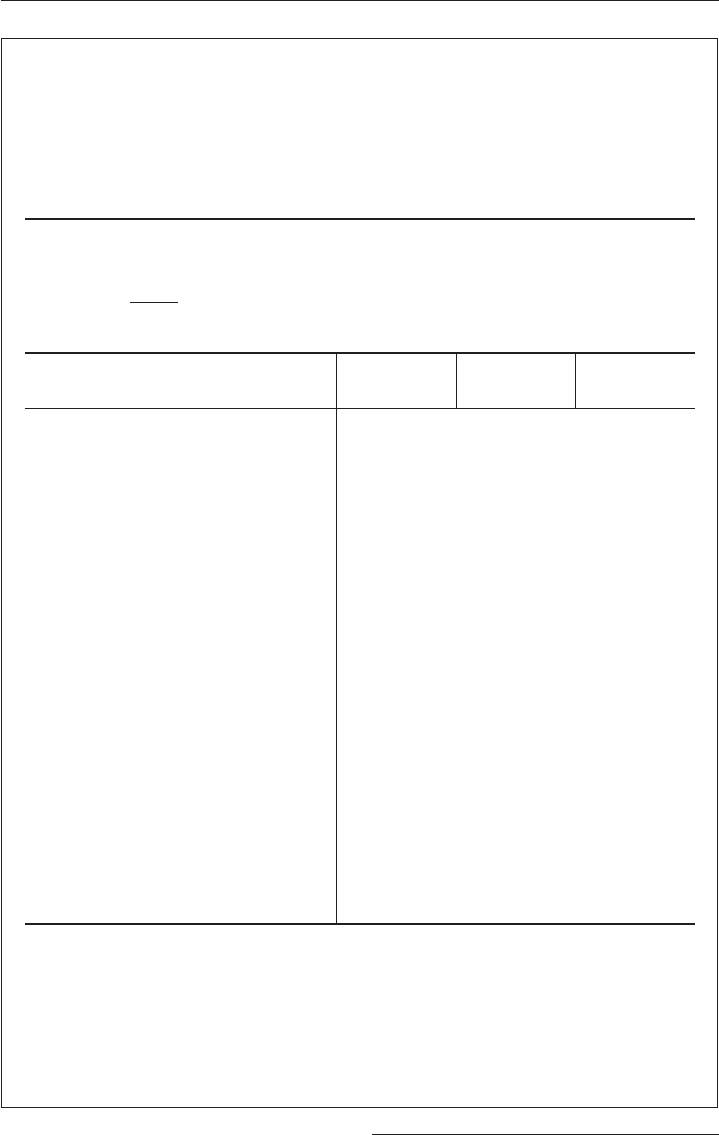

Section Tables of Contents

The detailed tables of contents sections, which

listed the subheadings within each major part of

the manual (parts 2000, 3000, 4000, and 5000)

have been removed. Because the Board no lon-

ger offers print versions or subscriptions for the

manual, these detailed tables of contents sec-

tions are obsolete. Manual readers can use the

search function within the online version of the

manual to find material. The General Table of

Contents (section 1010.0) at the beginning of

the manual, which provides a broad overview,

has been retained.

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual Supplement 54—February 2020

BHC Supervision Manual February 2020

Page 2

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual

Supplement 53—February 2019

This supplement reflects decisions of the Board

of Governors, new and revised statutory and

regulatory provisions, supervisory guidance, and

instructions that the Division of Supervision and

Regulation has issued since the publication of

the September 2017 supplement.

Section 1000.0

This section was renamed from “Foreword” to

“About this Manual” and now includes the rel-

evant content from sections 1020.0 and 1030.0.

In addition, the section clarifies the role of

supervisory guidance. A statute or regulation

has the force and effect of law. Unlike a law or

regulation, supervisory guidance does not have

the force and effect of law. Rather, supervisory

guidance outlines the agencies’ supervisory ex-

pectations or priorities and articulates the agen-

cies’ general views regarding appropriate prac-

tices for a given subject area. See SR letter

18-5/CA letter 18-7, “Interagency Statement

Clarifying Role of Supervisory Guidance,” for

more information.

Section 1020.0

The relevant content of this section, “Preface,”

was moved to section 1000.0 of this manual. As

a result, section 1020.0 was removed from the

Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual.

Section 1030.0

The relevant content in this section, “Use of the

Manual,” has been moved to section 1000.0 of

this manual. As a result, section 1030.0 was

removed from the Bank Holding Company Su-

pervision Manual.

Section 1060.0

This new section, “Large Financial Institution

Rating System,” presents the supervisory rating

system adopted in November 2018 for

• bank holding companies with total consoli-

dated assets of $100 billion or more;

• all non-insurance, non-commercial savings

and loan holding companies with total con-

solidated assets of $100 billion or more; and

• U.S. intermediate holding companies of for-

eign banking organizations with combined

U.S. assets of $50 billion or more established

pursuant to the Federal Reserve’s Regula-

tion YY.

The large financial institution (LFI) rating sys-

temrepresentsasupervisory evaluationofwhether

a firm possesses sufficient financial and opera-

tional strength and resilience to maintain safe-

and-sound operations and comply with laws and

regulations, including those related to consumer

protection, through a range of conditions. The

LFI rating system is composed of the following

three components: (1) Capital Planning and

Positions; (2) Liquidity Risk Management and

Positions; and (3) Governance and Controls.

The Federal Reserve will assign initial LFI rat-

ings to firms in the Large Institution Supervi-

sion Coordinating Committee portfolio in early

2019. For all other firms subject to the LFI

rating system, the Federal Reserve will assign

initial LFI ratings in early 2020. See 83 Fed.

Reg. 58,724 (November 21, 2018) and 84 Fed.

Reg. 4309 (February 15, 2019). See also SR

letter 19-3/CA letter 19-2, “Large Financial

Institution (LFI) Rating System.”

Section 1062.0

This new section, “RFI Rating System,” primar-

ily clarifies which supervisory rating system

applies to holding companies with total consoli-

dated assets less than $100 billion. In 2018, the

Board adopted the LFI rating system for bank

holding companies and non-insurance and non-

commercial savings and loan holding compa-

nies (SLHCs) with total consolidated assets of

$100 billion or more (see section 1060.0). Also

in 2018, the Board adopted the RFI rating sys-

tem for non-insurance and non-commercial

SLHCs with total consolidated assets less than

$100 billion. See 83 Fed. Reg. 56,081 (Novem-