PROFILES OF

TEENAGERS IN

PREWAR EUROPE

INTRODUCTION

The profiles compiled here feature the stories of real-life Jewish teenagers who lived in Europe and North Africa

between World War I and World War II. Some of the profiles are in the young people’s own words – their diaries,

autobiographies, and essays. Others are recounted based on interviews, testimonies, news articles, and dialogues.

It’s impossible to understand the scope of the tragedy that was the Holocaust without understanding what we lost.

By entering the world of these teenagers, students will better understand who the Jews were before they were

persecuted in the Holocaust and gain an appreciation for the diversity of Jewish life that existed prior to World War

II.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Anni Hazkelson ……………………….

Page

2

Esther ………………………………………...

Page

5

Hannah Senesh ……………………….

Page

8

Jakub Harefuler ………………………

Page

11

Petr Ginz …………………………………...

Page

14

Victor “Young” Perez ……………...

Page

17

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 1

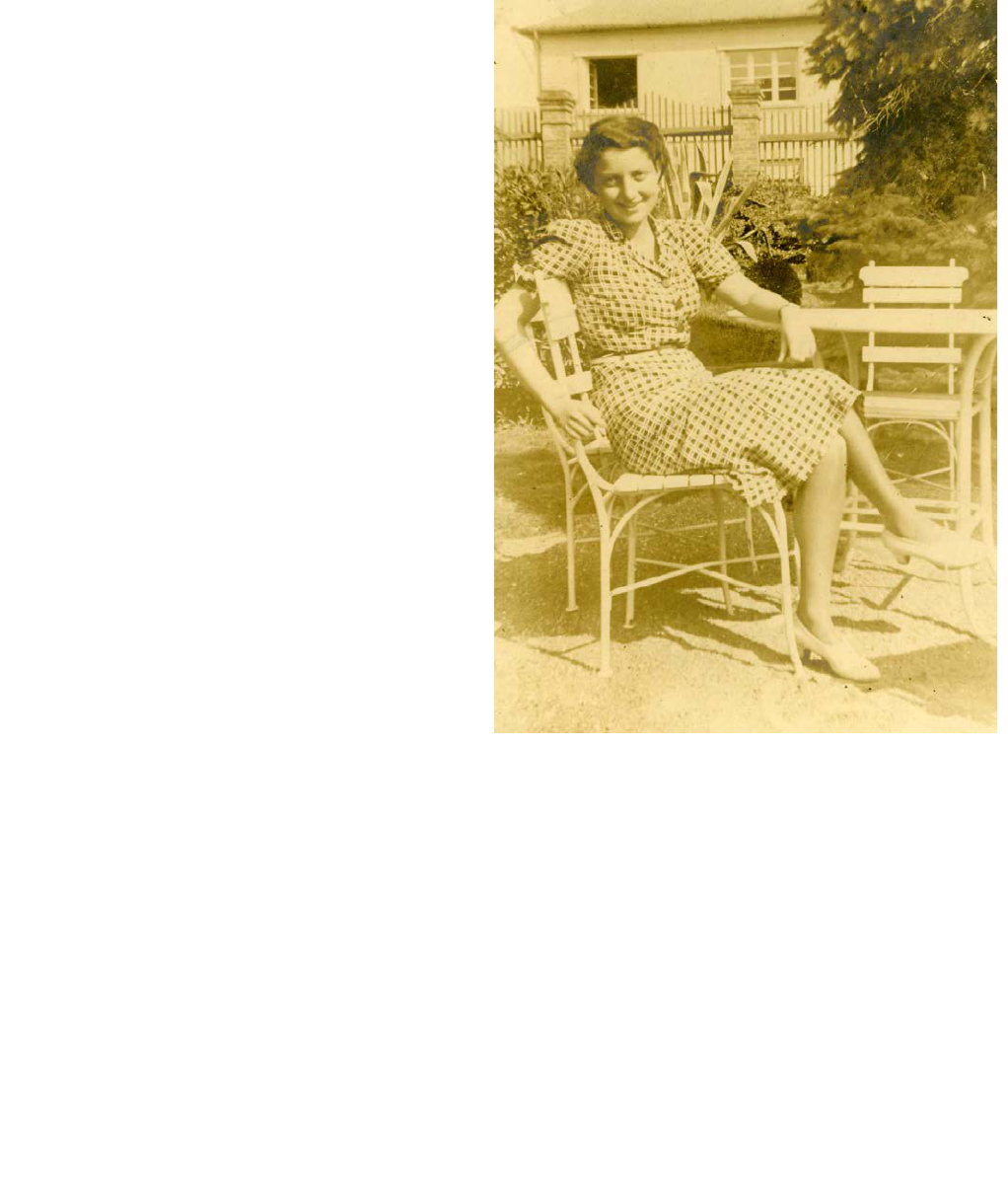

Anni Hazkelson

Anni Hazkelson was born on January 25, 1924. She lived in Riga, the capital of Latvia and the cultural center of Latvian

Jewry. Anni’s father, Shaya Benjamin, was a doctor, and her mother, Maria, taught English. Her sister, Lucy, was 2 ½

years younger than she was. Anni began keeping a diary two days after her 10th birthday. Though she spoke Latvian,

she kept her diary in German, a language spoken by many Latvian Jews. She also learned English with her mother.

The following are excerpts from Anni’s diary.

***

1934

January 27. I write poems which I would like to publish in the “Children’s Corner” of a newspaper. I would love to

write for a newspaper and become a real author. Mama said one day she would sooner see me become a doctor, like

Papa, but I don’t have the slightest desire to do that.

January 31. At the dental

clinic today they put

braces on my teeth.

February 14. Tomorrow

we are getting our marks.

I’m only worried about

arithmetic.

March 4. Yesterday I went

to the cinema, where

Oliver Twist was playing. I

liked the film very much.

March 31. Lucy has read

my diary. As a

punishment

I will no

longer tell her any stories.

[She] sticks her snooping little nose into everything.

April 6. How rough boys can be. Today some Latvians called me a “kosherbody” and threw paper at me. I simply told

them, “You’re a bunch of stupid boys.” But why this enmity? Didn’t the Jews shed their blood alongside the Latvians

in the fight for Latvia’s freedom? Then we were appreciated, but now that Latvia is free, they can do without us. Is

that just? But the Jews will not be kicked around forever. One day they too will see the dawn of liberty. If Latvia could

gain its freedom, why shouldn’t Palestine be able to do the same?

May 14. School ends on the 18

th

and only reopens on July 3

rd

. Mama says we get too much vacation. But vacations are

a wonderful thing, especially in summer. The sun is shining, we live near the beach or in the forest park, and one

can swim in the sea.

First page of Anni’s diary with her photo

from the diary of a Jewish girl from Riga, Latvia - Anni Hazkelson -

written 1934-1939. Yad Vashem Archives 0.33/6412.

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 2

June 4. In the synagogues they preach that we must

fight for Latvia and they sing the Latvian national

anthem. I love Latvia very much. The Jews have

many privileges and they are allowed to open

businesses and work.

June 16. The library from which we get our books is

about to be closed! Terrible! There will be long days

full of boredom.

September 23. I want to amount to something. Most

of all, I want not to be forgotten after my death.

1935

September 3. Why did they sing the two Latvian hymns in the synagogue this morning and not the Jewish one? It is

hard that even in a Jewish house of worship the Jews take a backseat.

October 26. After I complete my schooling I want to go to Palestine and there I want to propagate a free Palestine

that belongs only to the Jews.

November 29. What does it mean to be religious? Not to hold on fanatically to one’s own religion, but to see God in all

religions, that is the real, the true religion.

1936

January 25. Today is my birthday. I got many beautiful gifts. The one I liked best was The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

February 14. I’m in low spirits today. I have the impression that my classmates no longer accept me. They see in me a

conceited person who thinks she is better than they are. If they only knew how wrong they are.

June 3. Yesterday the class party took place after all. After tea there was a dance. I’m seldom asked for a dance.

November 21. That’s the tragedy of the Jews. No country of our own, without rest or peace, chased from one country

to the other; that is our tragedy.

1937

October 4. The main thing is love and forgiveness. Never forget that we are only human, with human faults, and that

only God has the right to judge.

Teenagers on the Beach in Riga, Latvia from a Page of Testimony

for Golda Gottlieb, Yad Vashem Photo Archives 15000/14070341.

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 3

October 12. If God came down to earth and asked, “What have you done with the world I gave you? Did you look after

it well? Did you deal with each other as is seemly between brothers and human beings?” In reply men would cast

their eyes down and keep their silence. Especially the white race, the English, French and Italians make life hell for

their colored brethren.

* * *

Anni’s diary is excerpted Diary of a Jewish girl from Riga, Latvia - Anni Hazkelson - written 1934-1939. Yad

Vashem Archives 0.33/6412

Grade 6 students at the Ezra School, Riga, Latvia, 1935. Anni is the third person from the left in the third

row from the bottom.

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 8449/39

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 4

Esther

“Esther” was one of a few hundred young Jews who submitted an autobiography to the Institute for Jewish Research in

Vilna (known as “YIVO”) as part of a contest in 1939. She submitted it anonymously, so her last name is unknown. She

was about 19 at the time, and came from the small town of Grójec, about 25 miles south of Warsaw, in Poland. On the

eve of World War II there were about 5,200 Jewish inhabitants in Grójec, who made up about 60% of the entire

population. They were traditional, religious Jews who worked in occupations connected with crafts and trade; most were

very poor.

What follows are excerpts from the autobiography Esther submitted.

***

I was born in 1920 into a strict Hasidic family. As far back as I can

remember, I was steeped in Hasidic traditions.

When I was five a woman named Sara Schenirer came to [town].

Her arrival caused an upheaval. People said that she was

establishing schools for Jewish girls.

The word “school” was magic to me. I envisioned a paradise.

Imagine! To be able to learn! Knowledge! I kept asking whether

they would teach us writing and arithmetic. Father answered,

“First you will learn to pray, to write Yiddish, and to translate the

prayers.” And when he told me that we would also study the

Bible, it took my breath away.

[A] Beys Yaakov school [for girls] was founded. I was an excellent

student. In the school I experienced my happiest moments as a

child. Finally I was able to study. After two years in Beys Yaakov, I

started to think about public school. Father didn’t like the idea of

my going to a school where boys and girls studied together.

Finally, Father promised me that I could go to public school, but

on one condition only: the Beys Yaakov school was to come first.

My freedom during those school days was limited. Father didn’t

let me go to the movies. This was forbidden because indecent and sacrilegious things were being shown there. But I

saved up my money and went. My heart throbbed with joy and excitement. When I came home I was terrified that

Father might find out. Quietly, I sneaked off to bed.

There was a library at school. When I said that the teacher had given me permission to sign up for the library, Father

stopped eating his dinner and declared that under no circumstances was I to read any [secular] books. Mother came

to my aid. Together we decided that I would sign up for the library without Father’s knowledge. And that is what I

did.

I devoted myself to reading with a passion. [In] books I found an enchanted world, filled with regal characters

involved in wondrous tales that completely captivated my young mind. I read in secret, so as to escape my father’s

notice. I was tormented by the thought that I was deceiving him, but I lacked the courage to tell him.

Four Hasidim talking in the street, Poland

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 1619/196

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 5

I participated in every spiritual aspect of Jewish life, both at home and in the Beys Yaakov school. I found spiritual

pleasure in the poetry of the Sabbath and holiday table, the melody of my father studying; these inspired me with

reverence for all that is beautiful and uplifting in the Jewish tradition.

The noble call to “love your neighbor as yourself,” proclaimed on the wall of the Beys Yaakov school, lived within me.

I understood what it meant to live in a community. And at the age of thirteen, I was elected leader of our group.

Those were years of faith.

At home we were beginning to feel the

impact of the unfolding economic

crisis. The haberdashery [tailoring

shop] we owned became smaller and

smaller. My father had to find other

means of supporting us. He became a

melamed [teacher of young children,

generally poorly paid and low on the

social ladder]. He taught older boys,

but it was still a big

blow to him.

A public school teacher had a great

influence on me. [We] constantly

planned amateur performances.

Amateur theater was my life. I was

never too tired to act in plays and I

especially liked to direct them. I

passionately loved all the preparations and the rehearsals. My imagination carried me to a faraway place, a dream

world. This made me forget the suffering at home, where things had taken a turn for the worse.

We had to sell the store. There wasn’t enough money to stay in business. We had to move to another apartment.

Mother started selling goods from our home, and Father continued teaching boys.

I completed public school [in 1935, after the seventh grade] and was faced with the question: What next?

[G]rim fate intervened. My father died suddenly. He passed away in the prime of life, at the age of forty-nine. Yes, it

is true that he was a strict father, but he never meant to harm me, nor was it his fault that he didn’t understand me.

Mother, my sister, and I faced a difficult task. How would we make a living? As the oldest daughter in the house, I

felt that I had responsibilities.

I received a letter offering me a position as a Beys Yaakov teacher in a small town. At seventeen years of age, I set

out on my journey all alone.

I arrived in a very small town: a sleepy country community, a few squat houses, a marketplace strewn with sand,

where all sorts of animals lazed about, and a church tower. This was the town at first glance.

Then the cold weather began. The poorer children stopped coming to school. This was a disastrous blow; there were

days when only half the children attended.

Pupils of the “Beis Yaakov” ultra-Orthodox girls’ school in Grójec, with

their mothers and teachers.

SOURCE: Ghetto Fighters' House Museum, Israel, Photo Archives, 27303

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 6

The antisemitism in this little town increased. It could be seen in the shrinking non-Jewish clientele in Jewish-

owned shops. It could be heard in the smashing of a windowpane on a dark night. It could be seen in the black eye of

a Jewish peddler. Naturally I felt it at the school as well.

The police followed me, observing my every move.

Every Sunday, peasants from the surrounding villages would gather outside the school window, look in and make

fun of the “Jewish school.” I had to struggle to be strong. Then once, during class, a policeman walked in. The

children were petrified, his face glowed with malice. [H]e declared that schools weren’t allowed unless they were

licensed. And so I had to close the school.

* * *

Esther’s autobiography is excerpted from Shandler, Jeffrey, ed. Awakening Lives: Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland

Before the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. Reproduced by permission of Yale University Press.

Excerpt from Esther’s autobiography, written in Yiddish

SOURCE: Yugfor #440, 1939, Archives of the YIVO Institut

e

for Jewish Research, New York

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 7

Hannah Senesh

Hannah Senesh (also spelled Szenes) was born on July 17, 1921 in Budapest, Hungary. She began keeping a diary when

she was 13 years old. Hannah’s family was highly cultured. Her father Bela, who was a famous playwright, passed away

of a heart attack when Hannah was barely six. She lived with her brother, Gyuri, who was slightly older than she, and

her mother, Catherine.

What follows are excerpts from her diary.

***

1934

September 12. Today was the first day of school. It’s strange to

realize that next year I’ll be in high school.

September 20. The other day there was an election in school. I got

all the votes but two. It was not the appointment that made me so

happy, but rather that all the girls in my class like me.

October 7. This morning there was a lovely celebration [of the

Jewish holidays], and this afternoon I went to synagogue. Those

afternoon services are so odd; it seems one does everything but

pray. The girls talk and look down at the boys, and the boys talk

and look up at the girls – this is what the entire thing consists of.

I’m glad I’ve grown lately. I’m now five feet tall and weigh 99

pounds. I don’t think I’m considered a particularly pretty girl, but I

hope I’ll improve.

October 14. I’m to tutor Marianne six hours a week. Now I can pay

for dancing and skating lessons with my own money. Perhaps I’ll

even buy a season ticket for the ice rink.

November 18. Gyuri [Hannah’s brother] found my diary not long ago and read the entire thing. I was furious because

he constantly teased me about it. But last night he took a solemn oath never to mention it again.

December 25. Sunday we went to the Opera to hear The Barber of Seville. It was a beautiful performance.

1935

September 16. Mama asked whether I would like to take piano lessons again this year, and I said yes.

1936

June 15. I would like to be a writer. For the time being I just laugh at myself; I’ve no idea whether I have any talent.

Hannah as a child, Budapest, Hungary

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 3213/1

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 8

June 18. When I began keeping a diary I decided I would write only about beautiful and serious things, and under no

circumstances constantly about boys, as most girls do. But it looks as if it’s not possible to exclude boys from the life

of a fifteen-year-old girl.

July 17. As of today I’m a vegetarian.

August 3. I still long to be a writer. It’s my constant wish. I don’t know

whether it’s simply a desire for praise and fame, but I do know it is

such a marvelous feeling to write something well that I think it is

worth struggling to become a writer. I would rather be an unusual

person than just average. And I would like to be a great soul. If God

will permit!

August 4. As I reread my last entry I became quite angry with myself.

What I wrote seems so terribly conceited. Great soul! I am so far away

from anything like that. I’m just a struggling fifteen-year-old girl

whose principal preoccupation is coping with herself. And this is the

most difficult battle. But even this sounds contrived.

August 31. I think I’ll eat meat a couple of times a week this winter

after all.

September 18. It’s the second day of the Jewish New Year. Yesterday

and today we went to synagogue. I am not quite clear just [where] I

stand: synagogue, religion, the question of God. About the last and

most difficult question I am the least disturbed. I believe in God -

even if I can’t express just how. Actually, I’m relatively clear on the

subject of religion, too, because Judaism fits in best with my way of

thinking. But the trouble with the synagogue is that I don’t find it at

all important and I don’t feel it to be a spiritual necessity; I can pray

equally well at home.

May 15. The person elected [secretary of the Literary Society] must be Protestant. It’s very depressing. Only now am

I beginning to see what it really means to be a Jew in a Christian society.

July 19. It’s already quite clear that there will be no boys this summer. There are a great many non-Jewish boys, but

the segregation here is so sharply defined one can’t possibly think of mixing, or imagine that a Christian boy would

even go near a Jewish girl. It is a very sad and disquieting sign.

Hannah and her brother, Budapest,

Hungary

c. 1933

SOURCE: Hannah Senesh Memorial Center via

PikiWiki – Israel

1937

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 9

1938

July 21. Saturday evening a rather large group of us went out and celebrated my birthday – my seventeenth. At

midnight we drank to my health, danced a bit, and at

about two in the morning went home.

October 27. I don’t know whether I’ve already

mentioned that I’ve become a Zionist. [I]t means, in

short, that I now consciously and strongly feel I am a

Jew, and am proud of it. My primary aim is to go to

Palestine, to work for it. Of course this did not develop

from one day to the next; it was a somewhat gradual

development. [P]eople, events, times have all brought

me closer to the idea, and I am immeasurably happy

that I’ve found this ideal, that I now feel firm ground

under my feet and can see a definite goal toward

which it is really worth striving. I am going to start

learning Hebrew, and I’ll attend one of the youth

groups. In short, I‘m really going to knuckle down

properly. I’ve become a different person, and it’s a

very good feeling.

One needs something to believe in, something for

which one can have whole-hearted enthusiasm. One

needs to feel that one’s life has meaning, that one is

needed in this world. Zionism fulfills all this for me.

1939

July 21. I’ve got it; I’ve got it! [The document that

allowed Hannah to move to British Mandatory

Palestine]. I’m filled with joy and happiness! I don’t

know what to write; I can’t believe it. But I can

understand that Mother can’t see the matter as I do;

she is filled with conflicting emotions, and is really brave. I won’t ever forget her sacrifice.

* * *

Hannah’s diary is excerpted from Hannah Senesh: Her Life and Diary, Schocken Books, New York, NY, 1972.

Hannah in Budapest, Hungary 1939

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 3213/39

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 10

Jakub Harefuler

“Jakub” was one of a few hundred young Jews who submitted an autobiography to the Institute for Jewish Research in

Vilna (known as “YIVO”) as part of a contest. He was 18 at the time he submitted his autobiography, which was written

in Polish. He was from Warsaw, the capital of Poland, which had the largest Jewish community in Europe in the prewar

world. Jakub was not his real name; he used it to mask his identity in order to write more freely.

What follows are excerpts from his autobiography.

***

I was born on 15 March 1921. My name is Jakub; I am the oldest child in my family; I also have two brothers and two

sisters. We live in a dark room, where the filth makes me cringe, although there’s nothing I can do about it. [My

brother] Boruch and I work at home with our father; we earn our living by sitting at machines, making baby shoes. I

don’t have a mother; she died when I was fourteen.

During the first period of my life we lived in a garret over my grandmother’s kitchen [on] a street inhabited by poor,

simple people and by the dregs of society. My first friend [and I] collected cigarette boxes. Every one of these boxes

was a prized possession. We later did the same with the silver wrappers from chocolates. In the winter we spent

time skating, making snowmen, and having snowball fights.

When I was three I went to a kheyder [school for very

young boys]. [The teacher] listened to us chant the

Bible. On the wall behind our teacher were colorful

portraits of Aaron and Moses. The Bible was my first

intellectual and spiritual source of inspiration.

Studying it prompted vivid fantasies and awoke a

strong sense of Jewishness in me. I saw Adam and

Eve, the sunny land of Palestine. This instilled in me

a faith in my existence and in God’s existence, a faith

in everything that religion proclaimed.

[T]he holidays inspired my most heartfelt feelings.

Memories of [traditions including] new clothes,

cakes, eating sweets and watching my father dance

with the Torah scroll as I held a little flag in my

hand.

Whenever I remember these things today, I become furious with the so-called “Enlightenment.” I would give a great

deal to be able to experience this celebratory feeling, this cheerfulness once again. Education opened my eyes,

awoke me from a religious dream, from the wonderful, age-old poetry of my people, and converted me to realism.

But the dream was more beautiful than the awakening.

In 1930 we moved. A new change entered my life: the school. [We learned] Polish language, history, math, Jewish

studies. We put on a show for the members of the society that supported our school [in] Yiddish and Polish. That was

the most wonderful time of my childhood. The school developed my sense of being a Polish Jew. I hadn’t been an

old-fashioned, zealously religious Jew for a long time but I had become casual about my Jewishness. I came to love

Poland and the Polish language more than Yiddish.

Jewish boys studying Torah at a Cheder, also spelled

kheyder (a religious elementary school), Poland

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 1475/22

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 11

I started working at home [after my mother died] with my father. Because of my family’s situation I’m buried in

work that I’ve never cared for from the start. Since I started working I’ve started reading again. I read books

by Jules Verne and other such authors. I remember in particular how avidly I read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Robinson

Crusoe, which made a big impression on me. They developed my imagination and acquainted me with things I’ve

never seen.

[I joined] a youth organization [that

stood for] a fearless struggle for

justice. This was the most important

period in my life. I found enlightenment.

The meetings, distributing of leaflets,

hanging of posters, flags, mass

assemblies – all this shaped my intellect.

I can’t describe the feelings I’ve had on

camping trips and outings. All this had a

positive effect on me. [T]he way I related

to other people, especially girls, changed

radically. At one time, other people

made me uncomfortable. I wasn’t

sociable and didn’t have any manners.

Now, all at once, I had clearly changed.

child, over the grave of an

awakening life.”

Members of Hashomer Haleumi (“National Guardsmen”), a Zionist youth

group, at a camp, Moroczno, Poland

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 6465/16

I didn’t realize what a teeming maze of narrow streets my youth had been crammed into until I returned from

[camp’s] broad unlimited spaces. Now my apartment looked strange: dirt, stale air, darkness. Only now I saw my

great poverty, which I hadn’t

noticed out of habit. I’m ashamed to

say that I burst into tears as I sat on

[my younger brother, Menahem’s]

bed. He woke up, cheerily called out

my name, put his little arms around

my head and pressed against me,

happy to see me. I had to cry. His

skinny arms embracing me, his

pale, haggard, sleepy face lit up, the

dirty sheets, the peeling walls, the

unpleasant smell, and the still-vivid

impression of the freedom I had

experienced moved me to tears.

With my head on my pillow I cried

and whispered to myself, “I’m

crying over the living grave of this

Business courtyard on Nalewki Street in the Jewish quarter, Warsaw,

Poland, 1938

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 12

No one, I think, longs for education more than I do. Learning is essential nutrition for my mind, and my mind’s

appetite is as big as my stomach’s.

I’m a poor, assimilated fellow. I’m a Jew and a Pole,

or rather I was Jew but under the influence of the

environment, language, culture and literature, I

evolved into a Pole – I love Poland. But I don’t love

the Poland that hates me for no reason. I hate the

Poland that doesn’t want me as a Pole and sees me

only as a Jew, that wants to chase me out of the

country in which I was born and raised. That Poland

I hate – I hate its anti-Semitism. I don’t know what I

am: a Jew or a Pole. I want to be a Pole but you won’t

let me. I want to be a Jew, but I can’t; I’ve moved

away from Jewishness.

Poland rejects me as a Jew and only a Jew, treating

me like a foreigner. I look around and see that

Poland isn’t mine, and I can’t be free here. [T]he

most ignorant lout – who doesn’t possess even a

fraction of my knowledge of Polish culture - can

wound my human dignity, taunt me and punch me

in the face – simply because I was born a Jew.

I started taking an interest in the Zionist

movement. I can imagine the journey to [Palestine]

the land of my dreams. I can see myself walking

behind a plow with a rifle on my shoulder, with a

free heart, a free gait, and a proud peaceful gaze.

* * *

Jakub’s autobiography is excerpted from Shandler, Jeffrey, ed. Awakening Lives: Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland

Before the Holocaust, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. Reproduced by permission of Yale University Press.

Excerpt from Jakub’s autobiography, written in Polish

SOURCE: Yugfor #581, 1939, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 13

Petr Ginz

Petr Ginz was an artist, a novelist, a poet, a reporter, and a

scientist, all before the age of 15.

He was born in Czechoslovakia, a progressive democracy. His

Jewish father and his Christian mother met and fell in love at a

conference for Esperanto, an “artificial” language invented to

unite humanity and bring world peace. Petr was born in Prague

on February 1, 1928. His sister, Eva (later Chava) was born two

years later.

Petr’s father was a strict disciplinarian, but the children knew he

loved them. Chava has said, “Our parents raised Petr and me to

have good manners, discipline and education. They taught us to

distinguish between right and wrong, good and bad.” Chava

loved and looked up to Petr, but the two also fought with each

other. Petr teased Chava by calling her Slecna Brecna (Miss

Crybaby or, in rhyme, Missy Sissy). Yet, by her own admission,

she always tried to copy everything he did.

Their house was filled with books, and Petr became a non-stop

reader. Chava remembers, “Our father and mother had a large

library, and we children were allowed to read some of these

books. And we … would go to the public library. We borrowed

books there quite often.” Petr himself began to write as a child;

he began by writing short stories and he turned his attention to

writing longer works from the age of around 13. He wrote five

novels before he turned 14. He also wrote articles, stories and

poems, and drew a lot as well.

He dreamed of far off adventures and fantastic journeys to the center of the earth and the bottom of the sea. He had

a rich imagination. He devoured science fiction and especially loved the French novelist Jules Verne. In fact, Petr

took Verne’s fantasy one step further: Verne wrote Around the World in Eighty Days; Petr wrote Around the World in

a Second.

Petr also painted and drew: strange and incredible sea creatures, robots, lush jungles filled with giant flowers and

erupting volcanoes. He illustrated at least one of his own novels.

Petr was curious about everything in his world. Chava remembers that “Petr was hungry for knowledge. [D]uring

our joint outings Petr walked with his eyes firmly on the ground, and therefore often found some ‘treasure’ – a

special veined stone, a bead or even a coin.”

He was a serious boy, but he could be naughty as well. His blue eyes were often playfully happy due to some boyish

mischief.

Peter Ginz, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1931

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Archives 6352/14

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 14

Petr went to an excellent Jewish school in Prague. One of its goals was to foster a pride of Judaism in its students.

Besides traditional academics, the students learned about Jewish history and culture, celebrated Jewish holidays,

and took field trips to museums and sites of Czech heritage.

Like most Czech Jews of their generation, the Ginz family identified with Jewish culture more than strict religious

Orthodoxy. Petr celebrated his Bar Mitzvah with his proud family when he was 13 years old. At home, there was a

Jewish atmosphere, but it was less traditional. Chava remembers that her family attended the synagogue only on

major holidays. Their mother kept a kosher household, but in a liberal fashion. The children were brought up in a

Jewish spirit, observing all Jewish holidays.

In addition to Jewish culture, Petr and his sister celebrated holidays with his mother’s non-Jewish family, especially

Christmas. According to Chava, this made for a rich and happy childhood with an atmosphere full of love, that drew

from both sides of the family.

There was little

antisemitism in

Czechoslovakia, which was a

progressive and tolerant

democracy. However, Chava

remembers incidents at

school. “During recess we

would go out into the

schoolyard, which was

separated from the yard of

the German school by just a

fence, and those small

German boys would even

then yell things like 'Juden

heraus!' [Jews out!] and 'Jews

to Palestine' at us.”

Petr and his sister went to

museums and concerts with

their parents. They strolled

along the river Vltava that

ran through Prague, and

took up many sports.

Chava describes their daily life:

“In our home it was important that the children pay attention to their responsibilities and that all

was in order. In the morning we rose, the maid prepared breakfast and then Petr and I would walk

by ourselves to school. … It was a beautiful walk; on winter mornings the gas lamps would still be lit

and the snow would crunch under our feet. …. [After school] we would play a bit at home, and then

go out for a walk, usually with the maid. Often we would … toboggan or play with a ball, and when it

was warm, you could bathe in the Vltava there. And in the winter we would again go to the Vltava,

to skate; the river froze over regularly…. [After] suppertime… Petr and I would like to read, there

really wasn't any other form of entertainment. Reading was our main hobby.”

Petr and his sister, Eva (Chava), Otradovice, Czechoslovakia, 1933

SOURCE: Y

ad Vashem Archives 6352/10

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 15

Petr’s extended family was a warm and constant presence in his life. He and his family visited his grandmother

every Saturday. She recognized Petr’s creativity and would often give him antique prints to transform into vivid

color. Chava remembers,

“Our household was always a hive of activity and fun, and we always had visitors over, and also our

Ginz relatives, grandma and my father's brothers and sisters. . . . On Sunday we would go for a walk

in the park, together with the children of the other uncles and aunts we would run on ahead and

play, and the parents would walk behind us and talk. Back then we had to be nicely dressed . . .

[with] shiny shoes - so we wouldn't cast a bad light on the family.”

* * *

SOURCES

Neuner, Pavla. “Interview with Chava Pressburger.” Centropa. https://www.centropa.org/sites/default/files/cz_pressburger_a4.pdf.

Yad Vashem. Holocaust survivor testimony of Chava Pressburger. https://www.yadvashem.org/holocaust/video-testimonies.html.

Memory of Nations. Interview with Chava Pressburger. https://www.memoryofnations.eu/en/pressburgerova-roz-ginzova-chava-eva-

1930.

Pressburger, Chava, ed. The Diary of Petr Ginz 1941-1942. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007.

IWitness.

Testimony of Chava Pressburger.

The four members of the Ginz family, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1939

SOURCE: Yad Vashem Arc

hives 6352/1

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 16

Victor “Young” Perez

“He was a superstar, just like soccer players these days, like Ronaldo or Messi.” - Yossi Bariach, neighbor from Tunis.

Messaoud Hai Victor Perez was an unlikely

superstar. He was born in the Jewish quarter

of Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, on October 18,

1911. His father, a salesman of household

goods, and his mother, a homemaker, had six

children and lived in the “Hara” – the Jewish

“ghetto”, an area of narrow, dusty streets that

was the poorest area of the city. But Jewish life

inside these houses was warm and rich. Most

families, including Victor’s, were religiously

and culturally Jewish – they celebrated the

Sabbath and holidays with traditional foods

and customs. Victor was not as religious as his

parents were, but he learned enough Hebrew

to enable him to read the Torah for his Bar

Mitzvah at thirteen years old.

Tunisia was then controlled by France. Victor learned in a school system established to give Jewish children both a

Jewish and a modern French education, despite their poverty. He started working at the port in Tunis at the age of 11

to make some money. Mischievous and gutsy, Victor also had a

big heart. Once he swiped some oranges for his mother from the

marketplace. The family couldn’t afford them, but he knew she

loved them.

Jews were a tiny minority in Tunisia; relations with the Muslims,

who were 99% of the population, were unpredictable. A terrifying

incident occurred in 1918 when Victor was a little boy. Jews were

attacked by Muslim Tunisian soldiers who went down to the Hara,

beat Jews in the streets, and looted stores and houses. The French

police did nothing to stop them. Jews were left wounded and dead

in the rioting. Victor’s mother hid him, together with his older

brother, Benjamin, under a bed in their house when the rioters

stormed in.

From an early age Victor dreamed of becoming a famous boxer,

but Jews were prohibited from joining local Arab sports

associations. So the Jews of Tunis organized their own sports club;

in 1912, the “Maccabi” sports organization was established on a

side street in the Jewish quarter. Organized sports were a modern

activity and a bridge between the Jewish and non-Jewish worlds.

Maccabi became the place for Jews who were interested in sports

to train.

Maccabi Boxing Club, Tunis, Tunisia, 1923

SOURCE: Wikimedia Commons

Victor “Young” Perez

SOURCE: Wikimedia Commons

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 17

Benjamin, Victor’s older brother, was a boxer who trained at Maccabi and became the flyweight champion of North

Africa. In the ring, he was known as “Kid” Perez. Victor watched and learned. He too began to train at Maccabi. He

had natural talent. At the age of 14, Victor decided to drop out of school and pursue boxing. It was a glamorous way

to escape the poverty he knew and live a different type of life.

Victor was small and thin. He reached a height of only 5’1” and weighed around 115 pounds. His size meant that he

was not a power hitter, but he was amazingly agile and fast, and was a non-stop puncher. He decided to add the

nickname “Young” to his name, and in the ring he became known as Victor “Young” Perez, or just “Young.”

When his trainer, Joe Guez, organized his first match, Young didn’t even have a pair of real boxing shorts.

"We'll get some made," his trainer said.

"You know what?" said Young, becoming serious, "I would like to sew a Star of David onto them."

Taken aback, Joe looked at the young boy and was touched by the seriousness in his face.

"Is this very important to you?" he asked.

"Yes! It's very important!"

"OK," promised his trainer. "But only this time. The more neutral you are in the ring, the better."

Young made his boxing debut in shorts emblazoned with a symbol of

his Jewish identity, the Star of David. He was just sixteen.

That year, Young boxed throughout Tunisia and Algeria, winning all his

fights. Benjamin, then in Paris, urged his little brother to come try his

luck in France. So one day Young left his mother a note, went down to

the port and caught a ship to Marseilles. He had no ticket and not a

penny in his pockets. In Marseilles, a rabbi gave him enough money to

get to Paris. Just shy of seventeen, he had taken the step that would

change his life.

In Paris, Young worked during the day to support himself, but trained

the rest of the time. He found himself in a new country, boxing against

more experienced men, but he worked his way to the top of the

flyweight boxing world. At only nineteen he became the French

Flyweight Champion. Then, right after he turned twenty, he fought

American boxer Frankie Genaro for the world title. Genaro was an

Olympic Gold medalist and former World Flyweight Champion. The

fight was watched by 16,000 wildly excited spectators. Young knocked

Genaro to the canvas ten seconds into the second round of the match.

Paris newspapers called the win “brilliant and triumphant.” Young had

become World Champion.

Young returned to Tunis to celebrate. Nearly 100,000 people came out

for his victory parade. The governor of Tunisia gave him a medal,

Article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

1931

SOURCE: Brooklyn Public Library

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 18

declaring that he had united the Jews and the Arabs. Young made a pilgrimage to the ancient El Ghriba Synagogue

to give thanks.

André Nahum, a boy of 7 at the time, remembers what the championship meant to Tunisian Jewry.

“The undisputed flyweight champion! A Jew from Tunis, from the ghetto, from the Hara – it was

unthinkable. He completely washed away all the humiliations that had gone on for centuries. It was

a Jew they were talking about, in the papers, on the wireless, in France, in America, everywhere. He

was a legend. He was the star of the ghetto.”

Young never forgot where he came from and what it was like to be poor. He made money and gave much of it away

to his friends and his family. He contributed to charities, including to WIZO, a Zionist organization. To a friend who

scolded him for being too generous, he said, ''What’s the use of money if not to help those who are in need?''

* * *

SOURCES

André Nahum,

Four Leather Balls or the Strange Destiny of Young Perez, (Paris: Bibliophane, 2002) [French]. The dialogue

between Young and Joe Guez comes from this biography/narrative.

New York Times, October 27, 1931: “Perez Stops Genaro in Second Round in Paris to Win World Flyweight Title”, https://

timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1931/10/27/98065367.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0 Paris-Soir, October 28,

1931 [French].

Odette Guinard, Victor Perez, at http://www.memoireafriquedunord.net/biog/biog05_perez.htm [French].

“Forever Young” in One Sports by Mor Reches and Assi Mamman, April 28, 2014 at https://www.one.co.il/

article/16-17/7,983,0,0/232584.html [Hebrew].

Searching for Victor “Young” Perez. Dir. Sophie Nahum. EPF Media, 2016. Film. The quote from André Nahum comes from

this film.

STUDYING THE HOLOCAUST

© Echoes & Reflections Partnership 19