1

Standard Definitions

Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys

Revised 2023

List Samples

Address-Based (ABS) Samples

Phone Samples

Online Panel Surveys

Calculating Outcome Rates from Final Dispositions

2023

THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR PUBLIC OPINION RESEARCH

2

Table of Contents

About This Report ................................................................................................................................... 5

Background ............................................................................................................................................. 6

This report: .......................................................................................................................................... 7

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 8

Using the Updated Standard Definitions Guide .................................................................................... 8

Final Disposition Codes ...................................................................................................................... 10

Completed and Partial Questionnaires ............................................................................................... 10

Modifications of the Final Disposition Codes .................................................................................. 11

Temporary vs. Final Disposition Codes ........................................................................................... 12

Substitutions ..................................................................................................................................... 14

Proxies .............................................................................................................................................. 14

Complex designs ................................................................................................................................ 15

Section 1: List Samples .......................................................................................................................... 16

Table of disposition codes ................................................................................................................. 17

Table 1.1. Valid Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) Dispositions for List Samples ...................... 17

Table 1.2 Valid Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview Dispositions for List Samples ........................... 19

Table 1.3. Not Eligible 4.0 for List Samples ..................................................................................... 21

1.1 Mail Surveys of Specifically Named Persons/Entities .............................................................. 21

Eligible, no returned questionnaire (non-response) ....................................................................... 22

Unknown eligibility, no returned questionnaire ............................................................................. 24

Not eligible .................................................................................................................................... 25

1.2 Email Surveys of Lists of Specifically Named Persons .............................................................. 26

Eligible, No Returned Questionnaire (Non-response) ..................................................................... 28

Unknown Eligibility, No Questionnaire Returned............................................................................ 29

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 29

1.3 Phone Surveys of Lists of Specifically Named Persons ............................................................. 30

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 30

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 30

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 30

1.4 In-Person Surveys of Lists of Specifically-Named Persons/Entities .......................................... 31

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 31

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 31

3

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 31

1.5 Web-Push Surveys of Lists of Specifically Named Persons ....................................................... 31

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 32

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 32

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 32

1.6 SMS (Short Message Service) or “Text Message” Surveys ....................................................... 32

Eligible cases that are not interviewed (non-respondents) ............................................................. 33

Cases of unknown eligibility ........................................................................................................... 34

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 34

Section 2: Address-Based Samples (ABS)................................................................................................ 35

Within-Unit Screening ....................................................................................................................... 36

Using appended supplemental contact information ........................................................................... 37

Appending a Name to Randomly Selected Addresses ......................................................................... 38

Table of disposition codes ................................................................................................................. 38

Table 2.1. Valid Eligible, No Interview (non-response) Dispositions for Samples of Unnamed

Addresses ...................................................................................................................................... 39

Table 2.2. Valid Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview Dispositions for Samples of Unnamed Addresses

...................................................................................................................................................... 41

Table 2.3. Valid Not Eligible Dispositions for Samples of Unnamed Addresses ................................ 45

2.1 Mail/Web-push surveys of Randomly Selected Addresses ...................................................... 45

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 45

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 49

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 49

2.2 In-person surveys of Randomly Selected Addresses (ABS) ...................................................... 50

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 51

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 51

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 51

2.3 Email surveys of Randomly Selected Addresses ...................................................................... 51

2.4 Phone Surveys of Randomly-Selected Addresses .................................................................... 52

2.5 SMS (Short Message Service) or “Text Message” Surveys ....................................................... 53

Section 3: Phone Samples, Random-Digit Dial (RDD) .............................................................................. 55

Within-Unit Selection ........................................................................................................................ 56

Dual-frame (DFRDD) Samples ............................................................................................................ 57

Table of disposition codes ................................................................................................................. 58

4

Table 3.1. Valid Eligible, No Interview (non-response) Dispositions for RDD Samples ..................... 59

Table 3.2. Valid Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview Dispositions for RDD Samples ......................... 61

Table 3.3. Valid Not Eligible Dispositions for RDD Samples ............................................................. 64

3.1 RDD Phone Surveys ................................................................................................................ 65

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 65

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 67

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 68

3.2 SMS/Text Messaging .............................................................................................................. 69

Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) ............................................................................................ 70

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview ................................................................................................ 70

Not Eligible .................................................................................................................................... 71

Section 4: Online Panel Surveys ............................................................................................................. 72

Probability-Based Internet Panels ...................................................................................................... 72

Table of disposition codes ................................................................................................................. 73

Table 4.1. Valid Eligible, No Interview (non-response) Dispositions for Samples from Online

Probability Panels .......................................................................................................................... 74

Table 4.2. Valid Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview Dispositions for Samples from Online Probability

Panels ............................................................................................................................................ 75

Table 4.3. Valid Not Eligible Dispositions for Samples from Online Probability Panels ..................... 77

Online Non-Probability Samples ........................................................................................................ 78

Section 5. Conclusion............................................................................................................................. 80

Section 6. References ............................................................................................................................ 81

Section 7. Calculating Outcome Rates from Final Disposition Distributions ............................................ 85

Calculating Outcome Rates from Final Disposition Distributions ........................................................ 85

Response Rates ................................................................................................................................. 85

Cooperation Rates ............................................................................................................................. 87

Refusal Rates ..................................................................................................................................... 87

Contact Rates .................................................................................................................................... 88

Some Complex Designs ...................................................................................................................... 88

Multistage Sample Designs ............................................................................................................ 88

Single-Stage Samples with Unequal Probabilities of Selection ........................................................ 89

Two-Phase Sample Designs ............................................................................................................ 90

5

About This Report

Standard Definitions has been a work in progress, with this being the tenth major edition. The American

Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) plans to continue updating it going forward, adding

comparable definitions for other modes of data collection and making other refinements as appropriate.

AAPOR also will be working with other organizations to further the widespread adoption and utilization

of Standard Definitions. AAPOR has been asking academic journals to use AAPOR standards in

evaluating and publishing articles; several, including Public Opinion Quarterly and the International

Journal of Public Opinion Research, have agreed to do so.

The first edition (1998) was based on the work of a committee headed by Tom W. Smith. Other AAPOR

members who served on the committee include Barbara Bailar, Mick Couper, Donald Dillman, Robert M.

Groves, William D. Kalsbeek, Jack Ludwig, Peter V. Miller, Harry O’Neill, and Stanley Presser. The second

edition (2000) was edited by Rob Daves, who chaired a group that included Janice Ballou, Paul J.

Lavrakas, David Moore, and Smith. Lavrakas led the writing for the portions dealing with mail surveys of

specifically named persons and for the reorganization of the earlier edition. The group wishes to thank

Don Dillman and David Demers for their comments on a draft of this edition. The third edition (2004)

was edited by Smith, who chaired a committee of Daves, Lavrakas, Daniel M. Merkle, and Couper.

Groves and Mike Brick mainly contributed the new material on complex samples. The fourth edition was

edited by Smith, who chaired a committee of Daves, Lavrakas, Couper, Shap Wolf, and Nancy

Mathiowetz. The new material on Internet surveys was mainly contributed by a subcommittee chaired

by Couper, with Lavrakas, Smith, and Tracy Tuten Ryan as members.

The fifth edition was edited by Smith, who chaired the committee of Daves, Lavrakas, Couper, Mary

Losch, and J. Michael Brick. New material in the fifth edition largely relates to the handling of cell

phones in surveys. The sixth edition was edited by Smith, who chaired the committee of Daves,

Lavrakas, Couper, Reg Baker, and Jon Cohen. Lavrakas led the updating of the section on postal codes.

Changes mainly dealt with mixed-mode surveys and methods for estimating eligibility rates for unknown

cases. The seventh edition was edited by Smith, who chaired the committee of Daves, Lavrakas, Couper,

Timothy Johnson, and Richard Morin. Couper led the updating of the section on internet surveys, and

Sara Zuckerbraun drafted the section on establishment surveys. The eighth edition was edited by Smith,

who chaired the committee of Daves, Lavrakas, Couper, and Johnson. Sara Zuckerbraun and Katherine

Morton developed the revised section on establishment surveys. The section on dual-frame phone

surveys was prepared by a sub-committee headed by Daves, with Smith, David Dutwin, Mario Callegaro,

and Mansour Fahimi as members. The ninth edition was edited by Smith, who chaired the committee of

Daves, Lavrakas, Couper, Johnson, and Dutwin. The new section on mail surveys of unnamed person was

prepared by a sub-committee headed by Dutwin with Couper, Daves, Johnson, Lavrakas, and Smith as

members.

This tenth edition was edited by Ned English, with significant contributions by Ashley Kirzinger, Ashley

Amaya, Cameron McPhee, Jenny Marlar, Mickey Jackson, Jennifer Berktold, and Amanda Nagle. Amaya

and McPhee led the revision and update of dispositions for this new version and drove much of the

restructuring. Nagle, McPhee, and P.J. Lugtig led the new paper on calculating e, which will appear

separately. Additional support for this edition was provided by Kristen Olson, Ashley Hyon, Ben Phillips,

Stephen Immerwahr, and Clifford Young. We also removed a section on establishment surveys that

needs updating and will be included in an addendum.

6

The tenth edition represents a wholesale reorganization of Standard Definitions, structured by frame

rather than mode as in previous versions to allow greater clarity and flexibility for users. We feel this

organization is more consistent with current survey designs and methodologies, specifically multi-mode

data collection, as modes can be appropriate for various frames and vice-versa. We also have a new

discussion of multi-mode designs and material on SMS (text) contact.

How to cite this report

This report was developed for AAPOR as a service to public opinion research and the survey research

industry, so please feel free to cite it. AAPOR requests that you use the following citation:

The American Association for Public Opinion Research. 2023 Standard Definitions:

Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 10

th

edition. AAPOR.

Background

Survey researchers have needed comprehensive and reliable diagnostic tools to understand the

components of total survey error. Some components, such as margin of sampling error, are relatively

easily calculated and familiar to many who use survey research. Other components, such as the

influence of question-wording on responses, are more difficult to ascertain. Groves (1989) catalogues

error into three other major potential areas where it can occur in sample surveys. One is coverage,

where error can result if some members of the population under study do not have a known nonzero

chance of being included in the sample. Another is measurement effect, such as when the instrument

or items on the instrument are constructed in such a way as to produce unreliable or invalid data. The

third is nonresponse error, where nonrespondents in the sample that researchers initially drew differ

from respondents in ways that are germane to the survey's objectives.

Often it is assumed — correctly or not — that the lower the response rate, the more question there is

about the validity of the sample. At the same time, the survey research industry has seen wholesale

declines in response rate in recent decades across mode and design (Curtin et al. 2005, Dutwin and

Lavrakas 2015, Brick and Williams 2013, de Leeuw et al. 2002). Although response rate information

alone is insufficient for determining how much nonresponse error exists in a survey, or even whether it

exists, calculating the rates is a critical first step to understanding the presence of this component of

potential survey error. By knowing the disposition of every element drawn in a survey sample,

researchers can assess whether their sample might contain nonresponse error and the potential reasons

for that error. Defining final disposition codes and calculating study outcome rates is the topic for this

report.

With this report, AAPOR offers an updated tool that can be used as a guide to quantifying one important

aspect of a survey’s quality. It is a comprehensive, well-delineated way of describing the final

disposition of cases and calculating outcome rates for surveys conducted using samples selected from a

variety of frames (list frames, RDD phone frames, address-based frames, as well as online sample

frames) and for data collected through multiple modes, including web, phone, paper-and-pencil, in-

person. These modes may be used alone or in combination.

7

The AAPOR Council stresses that all disclosure elements, not just selected ones, are important to

evaluate a survey. The Council has cautioned that there is no single number or measure that reflects the

total quality of a sample survey. As such, the information in this report should be used to report

outcome rates. Researchers will meet AAPOR's Standards for Minimal Disclosure requirements (Part III

of the Code of Professional Ethics and Practices) if they report final disposition codes as they are

outlined in this report, along with the other disclosure items. AAPOR's statement on reporting final

disposition codes and outcome rates can be found at the back of this booklet.

With this 10

th

edition, AAPOR hopes to continue the standardization of the codes researchers use to

catalogue the dispositions of sampled cases and their outcome rates. This objective requires a common

language and definitions the research industry can share. AAPOR urges all practitioners to use these

codes in all reports of survey methods, no matter if the project is proprietary work for private sector

clients or a public, government, or academic survey. This will enable researchers to find common

ground to compare the outcome rates for different surveys.

As observed by Tom Smith in the Ninth Edition, Linnaeus noted that “method [is] the soul of science.”

There have been earlier attempts at methodically defining response rates and disposition categories.

One of the best attempts is the 1982 Special Report on the Definition of Response Rates, issued by the

Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO). The AAPOR members who wrote the

current report extended the 1982 CASRO report, building on its formulas and definitions of disposition

categories.

This report:

▪ Has separate sections by frame, defined as list samples, address-based samples (ABS), phone

samples, and other situations.

▪ Contains an updated, detailed and comprehensive set of definitions for the four major types of

survey case dispositions: interviews, non-respondents, cases of unknown eligibility, and cases

ineligible to be interviewed.

▪ Contains tables delineating final disposition codes.

▪ Provides operational definitions and formulas for calculating response rates, cooperation rates,

refusal rates, and contact rates. The full set of definitions and formulas can be found at the end

of the report. Here are some basic definitions that the report details:

Response rates - The number of complete interviews with reporting units divided by the

number of eligible reporting units in the sample. The report provides six definitions of

response rates, ranging from the definition that yields the lowest rate to the definition

that yields the highest rate, depending on how partial interviews are considered and

how cases of unknown eligibility are handled.

Cooperation rates - The proportion of all cases interviewed out of all eligible units ever

contacted. The report provides four definitions of cooperation rates, ranging from a

minimum or lowest rate to a maximum or highest rate.

Refusal rates - The proportion of all cases in which a housing unit or the selected

respondent refuses to be interviewed or breaks off an interview out of all potentially

eligible cases. The report provides three definitions of refusal rates, which differ in how

they treat dispositions of cases of unknown eligibility.

8

Contact rates - The proportion of all cases in which the survey reached some

responsible housing unit member. The rates here are household-level rates. They are

based on contact with households, including respondents, rather than contacts with

respondents only. Respondent-level contact rates could also be calculated using only

contact with and refusals from known, eligible respondents.

▪ Demonstrates how to calculate response rates for dual frame RDD samples that require

multiple estimates for cases of unknown eligibility, or e.

▪ Provides an updated bibliography for researchers who want to understand better the influences

of non-random error (bias) in surveys.

Introduction

Using the Updated Standard Definitions Guide

There are a few topics that users should bear in mind when reading Standard Definitions for the first

time, which we summarize below. First, this tenth version of Standard Definitions has been re-organized

by frame rather than by data collection mode as in previous versions. This change is intended to reflect

how researchers design surveys in the present day and to better-accommodate multi-mode studies. An

important theme throughout this report is that case dispositions are tied to the frame from which a case

is sampled, and some dispositions can be applied consistently across frames. In contrast, others are only

appropriate for a specific frame, as reflected in the tables presented at the start of each section.

Researchers should also be aware that the salience of a disposition can vary depending on frame,

especially with respect to eligibility status.

Second, we acknowledge the proliferation of multi-mode designs in the survey industry over the past

decade. Whether multi-mode, or mixed-mode, designs can consist of surveys in which there are

separate samples that are each measured with different modes, a unified sample in which multiple

modes are used for individual cases, or a combination of both. As noted by an AAPOR task force, many

large-scale surveys have been transitioning from phone to combinations of multiple modes for

recruitment and survey administration, where phone may be only one of a number of modes that are

used, if at all (AAPOR, 2019). Multi-mode designs are utilized in surveys for a number of reasons: 1)

improving coverage; 2) increasing response rates and reducing non-response error; 3) reducing costs;

and 4) improving measurement (de Leeuw, 2018).

One example of a multi-mode survey of specifically named persons would be a survey of the AAPOR

membership, where members receive a postcard invitation with a link to an online survey, and

nonrespondents are subsequently contacted with a paper-and-pencil mail survey or by a live phone

interviewer. This type of web-push survey (see Section 1.5) is one example of a multi-mode survey, but

multi-mode surveys can be much more complex in their design. Multi-mode surveys can be sequential,

where different modes are offered to respondents in sequence, or concurrent, where respondents are

offered a choice of data collection mode. Other multi-mode surveys are multi-frame surveys. For

example, a study may combine an address-based sample of unnamed individuals (see Section 2) with

supplemental phone or online samples in an attempt to reach essential subgroups. Sampled units from

each frame may be contacted via various modes (e.g., mail, phone, email). The assignment of disposition

codes for these samples will vary by sampling frame. Users of the Guide should refer to different

9

sections if a multi-mode design utilizes multiple frames (e.g., ABS and RDD). Multi-mode designs that

use the same frame can refer to the mode references in the same section.

With respect to the AAPOR response rate calculator, users should make determinations about case

eligibility based on the sample frame from which a case is sampled. Among those known to be eligible

(disposition codes starting 1.0 or 2.0), specific interview sub-disposition codes will often be determined

by the contact or data collection mode(s). Disposition codes related to participant ineligibility or

unknown eligibility (3.0, 4.0) will often be determined by considerations related to the sample frame.

Following the example of the multi-mode survey of AAPOR members, all interview disposition codes

would draw from those discussed in the section on list samples (Section 1). The multiple modes of

contact and response (i.e., mail, web, and phone) will determine the subcodes used to classify cases into

different subsets of respondents, eligible nonrespondents, and ineligibles. However, whether the case

information leads to the classification of a sampled case as eligible (1.0 and 2.0), ineligible (4.0), or

unknown (3.0) will be based on the fact that a list of named individuals was used as the sample frame.

This is an important distinction that we address throughout the document. For example, a notification

that a piece of mail could not be delivered to a particular sampled unit on a list frame indicates a

locating issue. In contrast, a unit sampled from an address-based frame producing this notification

would likely be considered an ineligible sampled unit. Consequently, we expect appropriate disposition

categories and their outcomes to vary depending on frame.

For suggestions on keeping track of cases across modes, see Chearo and Van Haitsma (2010).

Third, there are many schemes for classifying the final disposition of cases in a survey. Previous

Standard Definitions committees reviewed more than two dozen classifications and found no two

exactly alike. They distinguished between seven and 28 basic categories. Many codes were unique to a

particular study and categories often were neither clearly defined nor comparable across surveys.

1

To limit the complexity of final disposition codes as much as possible and to allow the comparable

reporting of final dispositions and consistent calculation of outcome rates, AAPOR proposes a

standardized classification system for final disposition of sample cases, and a series of formulas that use

these codes to define and calculate the various rates.

A detailed report of the final disposition status of all sampled cases in a survey is vital for documenting a

survey’s performance and determining various outcome rates. Such a record is as important as detailed

business ledgers are to a bank or business. In recognition of this premise, the reports on the final

disposition of cases are often referred to as accounting tables (Frankel, 1983; Madow et al., 1983). They

are as essential to a well-documented survey as the former are to a well-organized business.

2

Assigning disposition codes to cases in-field is not entirely straightforward. Cases may be contacted at

multiple points through potentially different contact modes, yielding different outcomes (e.g., a survey

sequentially attains three dispositions for a single sample element: a non-contact, a soft refusal, and

1

Examples of some published classifications can be found in Hidiroglou et al., 1993; Frey, 1989; Lavrakas, 1993; Lessler and

Kalsbeek, 1992; Massey, 1995; and Wiseman and McDonald, 1978 and 1980.

2

The AAPOR statement on “best practices” (AAPOR, 1997, p. 9) calls for the disclosure of the “size of samples and sample

disposition — the results of sample implementation, including a full accounting of the final outcome of all sample cases:

e.g., total number of sample elements contacted, those not assigned or reached, refusals, terminations, non-eligibles, and

completed interviews or questionnaires …”

10

another non-contact). Researchers should assign the “highest” disposition to cases, reflecting the most

information we have thus far. A “soft refusal” establishes that a sampling unit contains a household,

while a “non-contact” provides less information about the sampled unit. Following the four disposition

categories described below, category 1 (completes) is the highest disposition, followed by category 4

(ineligible cases, category 2 (eligible cases that are not interviewed), and finally, category 3 (cases of

unknown eligibility). So, in our simplified example, we would assign the case in question to be a “soft

refusal” if data collection ended, as that provides more information than the most recent “non-contact”

disposition.

Final Disposition Codes

Survey cases can be divided into four main categories:

Category 1: Completed interviews;

Category 2: Eligible cases that are not interviewed (non-respondents);

Category 3: Cases of unknown eligibility; and

Category 4: Cases that are not eligible.

The following text and the tables at the end of this report are organized to reflect these four categories.

Although these classifications could be refined further (and some examples of further sub-categories are

mentioned in the text), they are meant to be mutually exclusive and exhaustive in that all possible final

dispositions should fit under one and only one of these categories.

The first of the following sections covers list samples, no matter what mode they are contacted. We

discuss designs based on web-push surveys, phone surveys, mail surveys, in-person surveys, and multi-

mode surveys of specifically named people. We also consider text or SMS surveys of specifically named

people, such as from a list and registry-based designs.

The second section deals with address-based sampling (or ABS) designs, employing any modes

mentioned in Section 1 for list samples.

The third section handles phone samples, specifically random-digit-dial (or RDD), with the fourth section

covering online panel surveys.

The four individual frame-oriented sections contain some redundancy, which is intentional, so

researchers interested only in one frame or mode can learn about the disposition codes for that frame

and mode without reading the sections dealing with others.

Completed and Partial Questionnaires

The definition of completed interviews is consistent across modes, so we address them in the

introduction. In any mode we can consider multiple levels of completion of the instrument, as described

in Table 1, specifically completes and partials. The distinction between completes and partials is the

proportion of questions answered by a respondent and should be defined by the researcher before data

collection using justifiable criteria. At one extreme, a respondent may provide an answer to each item.

But some respondents will get partway through the questionnaire and then, for various reasons, fail to

ever complete it, but still provide sufficient information as to be a “partial” rather than a “breakoff,” the

11

latter category being a type of refusal. In any case, a survey must provide a clear definition of these

statuses. Researchers may choose to report response rates with and without partials in the numerator,

for example, to illustrate the importance of partials and their definition to a given study.

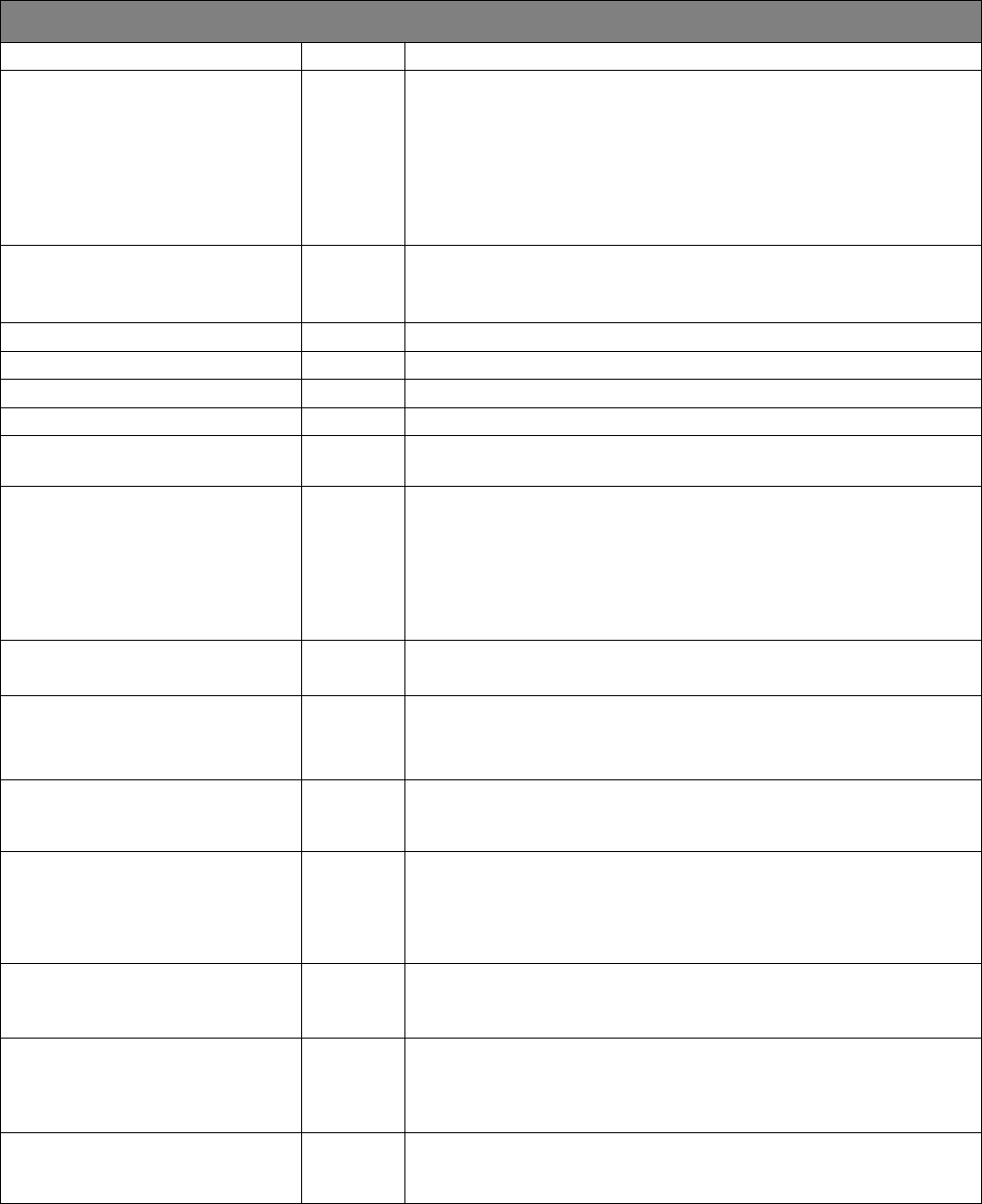

Table 1. Valid Interview Dispositions across Modes

Description

Value

Notes & Examples

Interview

1.0

A priori definitions are required to determine whether a case is a complete

or partial interview (or a breakoff). Three widely used standards for

defining these three statuses are:

a) the proportion of all applicable questions answered,

b) the proportion of all applicable questions asked, and

c) the proportion of crucial or essential questions answered (Frankel,

1983).

The above standards could be used in combination.

Complete

1.1

Example A: More than 80% of questions answered

Example B: More than 80% of questions asked

Example C: 100% of crucial or essential questions answered

Complete by Proxy

1.11

Partial

1.2

Example A: 50%-80% of questions answered

Example B: 50%-80% of questions asked

Example C: 50%-99% of crucial or essential questions answered

Partial by Proxy

1.21

How these types of incomplete cases are classified depends on the objectives of the survey and the

relative importance of various questions in the instrument., as well as on the particular design of the

survey (whether, for example, it is permitted to skip items without providing an answer). The sections in

this document on different modes of survey data collection for each frame discuss the different decision

rules for classifying cases as complete versus partial versus break-off so that discussion will not be

repeated here. The breakoff category could be further differentiated into the various sections or even

items at which the breakoff occurred, depending on the importance of these sections to the survey.

Modifications of the Final Disposition Codes

It is permissible to collapse categories if this does not compromise the calculation of outcome rates. For

example, refusals and break-offs can be reported as 2.10 rather than separately as 2.11 and 2.12 or

others (2.31-2.37) reported as generic others (2.3). Simplifications are permissible when they do not

obscure any of the standard rates delineated below. For example, no outcome rates depend on the

distinctions among non-contacts (2.21-2.27), so only the summary code 2.20 could be used if surveys

wanted to keep the number of categories limited. Simplified categories do not redefine classes or

remove the need for clear definitions of sub-classes not separately reported (e.g., break-offs).

As indicated above, more refined codes may be useful in general and for special studies. These should

consist of sub-codes under the categories listed in the relevant tables in each section. If researchers

want categories that cut across codes in the tables, they should record those categories as part of a

separate classification system or be distinguished as sub-codes under two or more of the codes already

provided. For example, one could subdivide refusals into a) refusals by the respondent; b) broken

appointments to avoid an interview; c) refusals by other household members; and d) refusals by a

household member when the respondent is unknown. These refusal distinctions can be especially

12

valuable when a survey deploys a “refusal conversion” process (Lavrakas, 1993). It is important to note

that while it is possible to subdivide a category in this way, it is not possible to define categories that

cross the main groups listed on page ten.

Temporary vs. Final Disposition Codes

Several disposition classifications used within the industry may include codes that more appropriately

reflect a temporary case status. Examples include:

▪ Maximum call limit met,

▪ Call back, respondent selected,

▪ Call back, respondent not selected,

▪ No call back by date of collection cut-off, and

▪ Broken appointments.

These and other temporary dispositions often are peculiar to individual CATI systems and survey

operations and are not necessarily dealt with here. These temporary, attempt-specific codes should be

replaced with final disposition codes listed in the tables in each section when final dispositions are

determined at the end of the survey.

In converting temporary codes into final disposition codes, one first must use appropriate temporary

codes. Temporary disposition codes should reflect the outcome of specific contact attempts before the

case is finalized. Many organizations mix disposition codes with what can be called action codes. Action

codes do not indicate the result of a contact attempt but what the status of the case is after a particular

attempt and what steps are to be taken next. Examples of these are:

▪ Maximum Number of Attempts

▪ General Callback

▪ Supervisor Review

In each case, these codes fail to indicate the outcome of the last contact attempt but instead suggest

the next required action (respectively, no further calls, callback, and supervisor to decide on the next

step). While action codes are important from a survey management point of view, they should not be

used as contact-specific, temporary disposition codes. Action codes are generally based on summaries

of the status of cases across attempts to date. In effect, they consider the case history to date, indicate

the summary status, and usually also the next step. These should also be distinguished from final codes,

representing the most informative status of a case at the close of data collection.

Typically, one will need to select a final disposition code from the often numerous and varied temporary

disposition codes. In considering the conversion of temporary to final disposition codes, one must

consider the best information from all contact attempts and how that information connects to the

frame from which the sample was selected. Temporary disposition codes may lead to different final

status codes for different frames. For example, a phone disposition indicating that a business has been

reached instead of a residential household would likely be coded with a final disposition of ineligible

(4.51) for an RDD phone survey. Still, due to the uncertainty introduced by phone matching, it may lead

to an unknown eligibility status of 3.1263 for an ABS survey that includes phone contacts. In deciding

between various possibly contradictory outcomes, four factors need to be considered: 1) status day, 2)

13

uncertainty of information, 3) hierarchy of disposition codes and 4) the frame from which the sample

was selected.

3

First, when eligibility is based on criteria that can change over time, it is necessary to choose a date on

which eligibility is determined—referred to as the “status day.” For example, suppose that the target

population is 18 to 65. Suppose further that when initial contact is made with a respondent, they are 65

and thus qualify for the study; an appointment is made to complete an interview later. If by that date,

the respondent has turned 66, the status date should determine their classification; specifically, the

respondent would remain eligible if they turned 66 after the status date but would be classified as

ineligible if they turned 66 before the status date. Similar considerations would apply if a person was

initially confirmed as eligible and selected to complete an interview but passed away before an

interview could be completed.

Second, information on a case may be uncertain due to contradictory information across or within

attempts. For example, one neighbor reported that a residence is vacant versus other evidence that it

may be occupied, or one mailing coming back as undeliverable with a U.S. Postal Service (USPS) “vacant”

code, while another yields a refusal. Or the lack of sufficient information to determine eligibility, for

example, whether the sample unit has a member of the target population. If the definitive situation for

a case cannot be determined, one should take the conservative approach of assuming the case is eligible

or possibly eligible rather than not eligible.

Next, there is a hierarchy of disposition codes in which certain temporary codes take precedence over

others. If no final disposition code is clearly assigned (e.g., completed case, all attempts coded as

refusals), the outcome of the last attempt involving contact with a sampled household or respondent will

determine the final disposition code.

Following the logic of the some-contact-over-other-outcome rule means that once there was a refusal,

the case would ultimately be classified as a refusal unless: a) the case was converted into an interview or

b) definitive information was obtained later that the case was not eligible (e.g., did not meet screening

criteria). For example, repeated no answers after a refusal would not lead to the case being classified as

no contact, nor would a subsequent disconnected phone number justify it being considered a non-

working number.

Likewise, in converting temporary codes into final codes, a case that involved an appointment that did

not end as an interview might be classified as a final refusal, even if a refusal was never explicitly given,

depending on circumstances. Unless there is specific evidence to suggest otherwise, it is recommended

that such cases be classified as a refusal.

If no final disposition code is clearly assigned and there is no contact of any kind on any attempt,

precedence should be given to the outcome providing the most information about the case. If there are

different non-human-contact outcomes and none are more informative than the others, one would

generally base the final disposition code on the last contact. For example, in a case sampled from a

phone number frame consisting of a combination of rings-no-answer, busy signals, and answering-

machines outcomes, the final code would be answering machine (3.123 for RDD or 2.22 if working with

3

For a discussion of assigning codes see McCarty, Christopher, "Differences in Response Rates Using Most Recent Versus Final

Dispositions in Phone Surveys," Public Opinion Quarterly, 67 (2003), 396-406.

14

a named, list sample, if the name is confirmed in the outgoing message) rather one of the other

disposition codes.

Of course, when applying these hierarchy rules, one must also follow the status day and uncertainty

guidelines discussed above.

Finally, as noted above, the frame from which a sampled unit is selected must be considered in the

assignment of final disposition codes. When possible, disposition codes must provide information about

the sampled unit, regardless of the contact mode for a given attempt. For example, the sampled unit will

be a phone number for an RDD frame. In contrast, the unit sampled from an ABS frame will be an

address or housing unit, which differs from a case sampled from a list or registry-based sample, which

may be a specifically named individual. A mailed survey to an ABS unit that is returned with information

that the household resident is deceased should not be coded as 4.11 (deceased) if there is a chance that

the housing unit is occupied by another individual since the sampling unit is the address, not a specific

person. However, the same type of mailed contact attempt would be classified as 4.11 if that specific

individual was sampled from a list (e.g., from a company’s employee list). Similarly, a soft refusal

provided to a phone number matched to an ABS sample that was not verified to be at the expected

address would be considered unknown eligibility (3.126). The same information provided in the RDD

context would be classified as a refusal (2.10) if no other eligibility criteria are required for that study.

Substitutions

Any substitution of sampled cases, replacing an originally-sampled unit with another, must be reported.

The main issue with substitution is that it violates probability sampling, as the probability of selection for

the substitute will be unknown. First, whatever substitution rules were used must be documented.

Second, the number and nature of the substitutions must be reported. These should distinguish and

cover both between- and within-household substitutions. Third, all replaced cases must be accounted

for in the final disposition codes. For example, if a household refuses, no one is reached at an initial

substitute household, and an interview is completed at a second substitute household. The total

number of cases would increase by two, and the three cases would be listed as one refusal, one no-one-

at-residence, and one interview. In addition, these cases should be listed in separate reports on

substitutions.

Similarly, within-household substitution would have to report the dropped and added cases and

separately document procedures for substitutions and number of substitutions. We recommend

calculating response rates with and without substitutes to show the importance of substitution to your

study. Respondent selection procedures must be clearly defined and strictly followed. Any variation

from these protocols likely constitutes a substitution and should be documented.

Proxies

A proxy is one individual who reports on behalf of an originally sampled person. This person might be a

sampled person's household member or a non-member (e.g., a caregiver). Any use of proxies must be

reported.

First, rules on the use of proxies must be reported. Second, the nature and circumstances of proxies

must be recorded, and any data file should distinguish proxy cases from respondent interviews. Third,

complete and partial interviews must be sub-divided into respondents (1.1 or 1.2) or proxies (e.g., 1.12

15

or 1.22) in the final disposition code. In the case of household informant surveys in which a) one person

reports on and for all household members and b) any responsible person in the household may be the

informant, this needs to be clearly documented, and the data file should indicate who the informant

was. In the final disposition codes and any rates calculated from these codes, researchers need to state

clearly that these are statistics for household informants. Rates based on household informants must be

explicitly and clearly distinguished from those based on a randomly chosen respondent or someone

fulfilling some special household status (e.g., head of household, chief shopper, etc.) When household

and respondent-level statistics are collected, final dispositions for both households and respondents

should be reported.

Complex designs

Complex surveys such as multi-wave longitudinal designs, surveys with multi-stage sampling, and

surveys that use a listing from a previous survey as a sample frame must report disposition codes and

outcome rates for each separate component and cumulatively. For example, a three-wave longitudinal

survey should report the disposition codes and related rates for the third wave (second reinterview) and

the cumulative dispositions and outcome rates across the three waves. Similarly, a survey such as the

National Survey of College Graduates (NSCG), which was based on a sample of respondents from the

American Community Survey (ACS), should report on both the outcomes from the NSCG field efforts and

incorporate results from the earlier ACS effort (i.e., accounting for nonresponse cases from both NSCG

and ACS).

Many other complex designs exist, such as samples with unequal probabilities of selection or designs

conducted in two or more stages, where non-respondents are subsampled in later stages. These

scenarios may require the calculation of weighted response rates. See the discussion in the "Some

Complex Designs" section for more details about these calculations.

16

Section 1: List Samples

This first section assumes a frame that lists specifically-named persons, with or without the ancillary

information necessary to collect data. Such people or list members could have associated physical

addresses, phone numbers (landline and/or mobile), and email addresses. It is possible to use

commercial vendors to match any contact information that may be missing or out-of-date. We assume

only that our frame is a list of individuals, and it would be possible to acquire or match the necessary

information to conduct data collection. One example of list samples is registry-based surveys or RBS.

RBS surveys include all surveys in which a random sample is drawn from units on a registration-based

list. Examples of RBS designs include sampling from the United States voter files (list of registered

voters) and market research among individuals subscribed to a particular service.

Importantly, this section assumes that once contact with the named respondent is made, some

screening would be needed to confirm that they are still eligible for inclusion. For a survey of registered

voters drawn from voting records, the eligibility rules could require that sampled voters still reside at

their indicated address, in the same state or community, and/or are still registered to vote. For this

reason, a failure to receive any reply to the survey would place them in the unknown eligibility category,

since it could not be confirmed that they meet these criteria. Similarly, various postal return codes that

failed to establish whether the person still lives at the mailed address would continue to leave eligibility

unknown.

When screening is required to confirm eligibility, care must be taken in determining whether a sampled

unit should be assigned an eligible nonrespondent or an unknown eligibility code. Cases for which the

respondent is contacted, but it is unknown whether they are eligible, usually occur because of a failure

to complete a needed screener. Even if this failure were the result of (for example) a “refusal,” a

breakoff, or the return of a blank questionnaire, it would only be assigned to one of these eligible

nonresponse codes. If eligibility were otherwise confirmed or could be inferred; otherwise, it should be

assigned a code of “No screener completed” (unknown eligibility). If useful for operational reasons,

researchers could create sub-codes that delineate the reason for the non-completion of the screener.

In some surveys, however, screening may not be necessary; it may be possible to assume that all

persons on the list are eligible unless otherwise determined. In such situations, the concept of unknown

eligibility does not apply, and the dispositions identified here as unknown eligibility codes should instead

be classified as eligible nonrespondent codes. Two examples of scenarios in which this treatment could

be appropriate include:

1. A sample of company employees drawn from a list of employees is known to be complete,

accurate, and up-to-date.

2. The second phase of a two-phase survey, in which the sampling frame is a list of persons who

were rostered and confirmed to be eligible in the first phase. Generally, the first phase in two-

phase surveys should follow the standards described in Section 2 for address-based samples

(ABS) or Section 3 for phone (RDD) samples. The second phase should follow the standards

described here for list samples, with all sampled units presumed to be eligible unless

determined otherwise. Additional discussion of two-phase surveys is provided in Section 2 on

ABS surveys.

17

In all cases, it is important that sampling and eligibility criteria and assumptions be decided upon

explicitly and precisely when the survey is designed. In these and other instances, the rules of eligibility

and the assumptions about eligibility will vary with the sample design and study objectives. The same

return codes may properly be assigned to different final dispositions in two studies based on different

eligibility assumptions, as in the examples above. Researchers must clearly describe their sample design

and study objectives and explicitly state and justify their assumptions about the eligibility of cases in

their sample to properly inform others how the case dispositions are defined.

Throughout this section, Standard Definitions explicitly uses the language employed by the USPS to

account for all USPS dispositions in which mail is not delivered to an addressee. Researchers operating in

other countries should treat these classifications as instructive and naturally will have to use their own

postal service codes. Non-USPS codes should follow the Standard Definitions’ logic and intent, as

illustrated by the USPS codes.

Table of disposition codes

Tables 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 provide eligible nonresponse, unknown eligibility, and ineligible codes

(respectively) applicable when sampling from a list of individuals or households. Refer to the

Introduction to this report for a discussion of general principles related to the identification of (fully or

partially) completed surveys, which apply regardless of frame. Note that in all the subsequent tables, a

single asterisk identifies a new disposition code; a disposition changed from the prior version of the

AAPOR Standard Definitions is indicated by two asterisks.

Table 1.1. Valid Eligible, No Interview (Non-response) Dispositions for List Samples

Description

Value

Notes & Examples

Eligible, Non-Interview

2.0

To be considered in this category, a case must first have been

determined to be eligible.

Example: An individual who states, ‘I do not want to participate’ before

confirming that you have reached a household and/or other eligibility

criteria should not be classified as an eligible refusal (2.10). See the

discussion about “Unknown Eligibility”.

Refusal and break-off

2.10

Refusal

2.11

Household-level (or proxy) Refusal

2.111

A member of the household of the named sample member has

declined to interview for the entire household.

Another individual from named entity explicitly refuses to allow

participation. No screening or confirmed eligibility is required

Parent or Guardian Explicit Refusal

2.1111*

The parent or guardian of the named minor respondent refuses to

allow participation

Known Respondent Refusal

2.112

The named respondent or entity directly refuses to participate

Logged on to survey, did not

complete any items

2.1121

Web-only

Email read receipt confirmation,

refusal

2.1122

Other Implicit Refusal

2.113

18

Blank questionnaire returned

(mailed survey)

2.1131*

No additional screening required

Named respondent set appointment

but did not keep it (phone or in-

person)

2.1132*

No additional screening required

Opted out of communications (SMS

or Email)

2.1133*

Break-off

2.12

The named respondent began the interview, web survey, or

questionnaire but opted to terminate it (or returned it with too many

missing items) before completing enough of it to be considered a

partial complete (see Introduction for guidance on classification of

partial interviews).

Non-contact

2.20

Named respondent never

available during field period

2.21**

Must confirm named respondent has been reached at address or

phone number.

If email contact, email is confirmed eligible and attached to named

respondent

Phone answering device (Phone)

2.22

No contact has been made with a human, but a phone answering

device (e.g., voicemail or answering machine) is reached that includes a

message confirming it is the number for the named sample member.

This code is only used if all sample members are eligible (i.e., no

additional screening is necessary).

Example: “You have reached John Smith. Please leave a message”.

Answering machine - no message

left (phone)

2.221

Answering machine - message left

(phone)

2.222

The interviewer left a message, alerting the household that it was

sampled for a survey, that an interviewer will call back, or with

instructions on how a respondent could call back.

Other non-contact

2.23

No additional screening is necessary

Quota filled (in released replicate4)

2.231*

No one reached at housing unit (in-

person)

2.24

No screening required for eligibility

Inability to gain access to sampled

housing unit (in-person)

2.241*

Completed questionnaire, but not

returned during field period

2.27

Other

2.3

Deceased respondent

2.31

Named respondent is deceased

Must be able to determine that named respondent was eligible on the

survey status date and died subsequently

Physically or mentally

unable/incompetent

2.32

The named respondent’s physical and/or mental status makes them

unable to do an interview. This includes both permanent conditions

(e.g., senility) and temporary conditions (e.g., pneumonia) that

prevailed whenever attempts were made to conduct an interview.

With a temporary condition, the respondent could be interviewed if re-

contacted later in the field period

4

A replicate may be defined as a subsample from the same population as the overall sample, designed under the same conditions.

19

Language or Technical Barrier

2.33

Household-level language problem

2.331

No one in the household speaks a language in which the interview is

offered (no screening required)

Respondent language problem

2.332

The named respondent does not speak a language in which the

interview is offered (no screening or respondent eligibility confirmed).

No interviewer available for needed

language/Wrong language

questionnaire

2.333

The language spoken in the household or by the respondent is offered.

However, an interviewer with appropriate language skills cannot be

assigned to the household/respondent at the time of contact (no

screening or respondent eligibility confirmed).

Inadequate audio quality or literacy

issues

2.34

No screener or eligibility confirmed

Location/Activity not allowing

interview

2.35

Example: cell phone reached while person is driving (no screening

required, or eligibility confirmed)

Someone other than respondent

completes questionnaire or

interview

2.36

Someone other than respondent

completes questionnaire or

interview – Full questionnaire

completed

2.361

Someone other than respondent

completes questionnaire or

interview – Partial questionnaire

completed

2.362

Wrong number

2.37

Eligibility of named person confirmed but the number dialed is

incorrect for the named person

Miscellaneous, non-interview

2.90

Miscellaneous (eligibility confirmed)

Examples: vows of silence, lost records, faked cases invalidated later on

Table 1.2 Valid Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview Dispositions for List Samples

Description

Value

Notes & Examples

Unknown Eligibility, Non-Interview

3.0

No Screener Completed, Unknown

3.20

No screener completed, unknown if sampled person is eligible

respondent

Refusals where screening is required

Undeliverable or unanswered where screening is required

Unreachable/screener not

completed

3.21

SEE APPENDIX FOR LIST OF POSSIBLE USPS CODES

USPS Category: Refused by

addressee (Mailed survey)

3.211

USPS Category: Refused by Addressee [REF] (screener required)

USPS Category: Return to Sender

(Mailed survey)

3.212

USPS category: Returned to Sender due to Various USPS Violations by

Addressee (screener required)

USPS Category: Cannot be delivered

(Mailed survey)

3.213

USPS Category: Cannot be Delivered [IA] (screener required)

USPS Category: Cannot be delivered

(Mailed survey)

3.214

Mail returned with Forwarding Information

NOTE: This can only be a final disposition for listed sample if a screener

is required

20

Unreachable (Phone)

3.215**

Unreachable, unknown if connected to named sampled

individual/entity/household (Screener required)

Always busy (Phone)

3.2151**

Screener required

No answer (Phone)

3.2152**

Screener required

Phone answering device (Phone)

3.2153**

Phone answering device (unknown if named respondent & screener

required)

The phone number connected to an answering device (e.g., voicemail

or answering machine), but the automated message did not

conclusively indicate whether the number is for the specifically named

individual or household.

Telecommunication technological

barriers (Phone)

3.2154**

Telecommunication technological barriers, e.g., call-blocking (unknown

if named respondent & screener required)

Call-screening, call-blocking, or other telecommunication technologies

that create barriers to getting through to a number

Technical phone problems (Phone)

3.2155**

Technical phone problems (unknown if named respondent & screener

required)

Examples: phone circuit overloads, bad phone lines, phone company

equipment switching problems, phone out of range (AAPOR Cell Phone

Task Force, 2008 & 2010b; Callegaro et al., 2007).

Ambiguous operator’s message

(Phone)

3.2156**

Ambiguous operator’s message (unknown if named respondent &

screener required)

An ambiguous operator’s message does not make clear whether the

number is associated with a household. This problem is more common

with cell phone numbers since there are both a wide variety of

company-specific codes used, and these codes are often unclear

(AAPOR Cell Phone Task Force, 2010b).

Non-working/ disconnected number

3.216*

Includes Fax/Data line (Unknown if named respondent & screener

required)

Interviewer unable to reach housing

unit (In-person)

3.217*

Includes situations where it is unsafe for an interviewer to attempt to

reach a housing unit (screener required)

Interviewer unable to locate housing

unit/address (In-person)

3.218*

Screener required

Invitation returned (Email or SMS

survey)

3.219*

Email/SMS invitation returned undelivered (screener required)

Message blocked by carrier (SMS

survey)

3.2191*

Carrier blocked message from being delivered

Message failed to send (SMS survey)

3.2192*

Screener required

Device unreachable (SMS)

3.2193*

Screener required

Device not supported (SMS)

2.2194*

Device does not support SMS (screener required)

Device powered off (SMS)

3.2195*

Screener required

Unknown error (SMS)

3.2196*

Screener required

Nothing ever returned

3.22

Nothing ever returned (screener required)

Not attempted or worked

3.23

No invitation sent

Questionnaire never mailed

No contact attempt made

Address not visited

21

Note, all cases in unassigned replicates (i.e., replicates in which no

contact has been attempted for any case in the replicate) should be

considered ineligible (Code 4), but once interviewers attempt to

contact any number in a given replicate, all cases in the replicate have

to be individually accounted for.

Other

3.90

This should only be used for highly unusual cases in which the eligibility

of the number is undetermined and does not clearly fit into one of the

above designations.

Example: High levels of item nonresponse in the screening interview

prevents eligibility determination.

Returned from an unsampled email

address (e-mail)

3.91

Screener required

Table 1.3. Not Eligible 4.0 for List Samples

Description

Value

Notes & Examples

Not Eligible

4.0

Selected Respondent Screened Out

of Sample

4.10

The named sample entity is reached but is determined to be ineligible

based on screening criteria.

Deceased

4.11*

Named respondent is deceased prior to survey start (status day)

Quota Filled

4.80

Ineligible in current replicate because quota filled in unreleased sample

replicate

Duplicate listing

4.81

Other

4.90

*New disposition code

**Updated disposition code

1.1 Mail Surveys of Specifically Named Persons/Entities

This section describes surveys that recruit respondents via mail in which the sampling unit is a

specifically named person, household, or other entity who is sent a self-administered questionnaire

(SAQ). Surveys using mail to contact participants vary greatly in the populations they cover and the

nature and quality of the sample frames from which their samples are drawn. As described in the frame-

level introduction, the named entity is the appropriate respondent. An example might be a sample of

registered voters residing in a particular community drawn from voting records for which mailing

addresses are available on, or can be appended to, the frame. In other words, the assumption is that

the target population is synonymous with the sampling frame and thus is defined as those persons on

the list with a valid mailing address. Different assumptions need to be made, and different rates apply

in the case of mixed-mode (e.g., email, phone, and mail push-to-web) designs. Web-push surveys are

covered in Section 1.5.

For mailed surveys sent to named sample units and other modes of contact discussed below, it is

important to remember that eligibility for the survey is linked to the sampled (listed) individual or entity

and not the contact information provided. For example, consider a survey of currently enrolled college

students at a particular university drawn from the registrar’s records or a study of professional

organization members pulled from the organizational directory. The records may include students who

have graduated, dropped out, transferred, or are no longer affiliated with the organization. Information

indicating that the sampled individual does not live at the provided mailing address does not determine

22

the sampled person’s final eligibility, as the address on the list could be incorrect or outdated. The

individual may have moved or changed how they receive their mail but could still be an enrolled, eligible

student or association member. Similarly, a failure to receive a reply to the survey invitation would place

them in the unknown eligibility category since it could not be confirmed whether they were still active

students/members.

Conversely, if a listed, sampled individual is reachable at a particular address, this does not necessarily

indicate the person’s eligibility. Often, screening is required to determine eligibility. Depending on the

quality of the list, different assumptions can be made about eligibility. For example, if it is known that

the list is accurate and current, it can be assumed that all those who receive no response are eligible

sample persons who must be treated as non-respondents. As with the other modes of data collection

described in this document, appropriate assumptions about eligibility may depend upon details of the

sample design and the state of the sampling frame or list. Researchers thus must clearly describe their

sample design and explicitly state and justify their assumptions about the eligibility of cases in the

sample to properly inform others of how the case dispositions are defined and applied. AAPOR has

prepared a document describing how to estimate the status of cases with unknown eligibility, known as

the parameter e, ate (https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/MainSiteFiles/ERATE09.pdf), with an

updated version planned for 2023.

As noted above, the discussion of completed interviews for mail surveys is similar to that for other

modes, so one may refer to Table 1 in the Introduction section for the list of dispositions.

Eligible, no returned questionnaire (non-response)

Eligible cases for which no interview is obtained consist of four types of non-response: a) refusals and

break-offs (2.1); b) non-contacts (2.2); c) others (2.3); and miscellaneous (2.9) as summarized in Table

1.1 in Section 1.

Refusals and break-offs consist of cases in which some contact has been made with the specifically

named person or with the housing/business unit in which this person is/was known to reside/work, and

the person or another responsible household/business member has declined to have the questionnaire

completed and returned (2.11); or a questionnaire is returned with too few items completed to be

considered a partial complete, with some notification that the respondent refuses to complete it further

(2.12 – see the Introduction section on what constitutes a break-off vs. a partial questionnaire).

5

Further useful distinctions include a) who refused, i.e., the named person (2.112) vs. another person

(2.1111); b) the point within the questionnaire of refusal/termination; and c) the reason for

refusal/break-off. In mail surveys, entirely blank questionnaires are sometimes mailed back in the return

envelope without explaining why the questionnaire was returned blank. Unless there is good reason to

do otherwise, this should be treated as an “implicit refusal” (2.113). In some instances, when a

noncontingent cash incentive was mailed to the respondent, the incentive was mailed back along with

the blank questionnaire. Researchers may want to create a unique disposition code to differentiate

these from the outcome in which no incentive was returned.

5

“Responsible household members” should be clearly defined. For example, the Current Population Survey considers any

household member 14 years of age or older as qualifying to be a household informant.

23

Known non-contacts in mail surveys of specifically named persons include cases in which researchers

receive notification that a respondent was unavailable to complete the questionnaire during the field

period (2.21).

6

This would include instances where the sampled unit is an entity other than a person

(e.g., a named household or a business), in which the sampled unit itself is confirmed eligible but no

person is available to respond on behalf of the sampled unit (e.g., no responsible household member

available).

7

There also may be instances in which the questionnaire was completed and mailed back too

late — after the field period has ended — to be eligible for inclusion (2.27), thus making this a “non-

interview.”

A related situation occurs in surveys that employ quotas when returned questionnaires are not treated

as part of the final dataset because the quota, or target number of completes, for a specific subgroup

has already been filled (2.231). The guiding principle when applying quotas is that eligibility criteria

must be established when a unit is released for data collection and should not change based on how

long it takes a unit to respond. Otherwise, eligible units excluded from the final dataset solely because of

a late response (whether “late” means after the end of the field period or after a quota was filled) are

properly coded as eligible nonrespondents, not ineligible cases.

Code 2.231 should be used when a unit meets the survey’s eligibility criteria. Otherwise, it would have

been included in the final dataset if they had responded earlier before the quota was met. Applying a

quota this way is akin to ending the field period early for subgroups whose quota has been filled. This

differs from a situation in which a sample replicate is released to only accept responses from particular

subgroups to meet quotas for those subgroups. In such situations, respondents from that replicate who

are outside of the target subgroups(s) for the replicate would be assigned code 4.1 (ineligible – selected

respondent screened out of sample) because they do not meet the eligibility criteria for the replicate for

which they were sampled. Consider the scenario where a survey sets separate quotas for Black and

Hispanic respondents. If the survey used only one sample release and stopped accepting responses from

Hispanic respondents after their quota was met, any Hispanic responses after this point would be

assigned code 2.23 (an eligible, non-interview code) because they were eligible at the time of sample

release. In contrast, if the survey met the Hispanic quota in the first sample release and then released a