AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Aesthetics and the Environment: The Appreciation of Nature, Art and Architecture

presents fresh and fascinating insights into our interpretation of the environment.

Although traditional aesthetics is often associated with the appreciation of art, Allen

Carlson shows how much of our aesthetic experience does not encompass art but

nature, in our responses to sunsets, mountains, or more mundane surroundings,

such as gardens or the views from our windows. He demonstrates that, unlike works

of art, natural and ordinary human environments are neither self-contained

aesthetic objects nor specifically designed for convenient aesthetic consumption. On

the contrary, our environments are ever present constantly engaging our senses, and

Carlson offers a thought-provoking and lucid investigation of what this means for

our appreciation of the world around us. He argues that knowledge of what it is we

are appreciating is essential to having an appropriate aesthetic experience and that

scientific understanding of nature can enhance our appreciation of it, rather than

denigrate it.

Aesthetics and the Environment also shows how ethical and aesthetic values are

closely connected, argues that aesthetic appreciation of natural and human

environments has objective grounding, and explores the important links between

ecology and the aesthetic experience of nature. This book will be essential reading

for those involved in environmental studies and aesthetics and all who are interested

in the controversial relationship between science and nature.

Allen Carlson is an authority in aesthetics and has pioneered the field of

environmental aesthetics. He is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Alberta,

Canada.

AESTHETICS AND THE

ENVIRONMENT

The appreciation of nature, art and

architecture

Allen Carlson

London and New York

First published 2000

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of

thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.”

© 2000 Allen Carlson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced

or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means,

now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and

recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Carlson, Allen

Aesthetics and the environment: the appreciation of nature, art and

architecture/Allen Carlson

p. cm.

“Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada”

Includes bibliographical references and index

1. Environment (Aesthetics)

BH301.E58C37 1999 99–28959

111′.85–dc21 CIP

ISBN 0-203-99502-3 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-415-20683-9 (Print Edition)

FOR ARLENE, ELEANOR AND VIRGINIA

CONTENTS

List of illustrations ix

Preface x

Acknowledgements xi

Introduction: aesthetics and the environment xii

PART I The appreciation of nature 1

1 The aesthetics of nature 3

A brief historical overview 3

A brief overview of contemporary positions 5

The natural environmental model: some further ramifications 11

Notes 13

2 Understanding and aesthetic experience 17

Aesthetic experience on the Mississippi 17

Formalism and aesthetic experience 19

Disinterestedness and aesthetic experience 24

Conclusion 27

Notes 27

3 Formal qualities in the natural environment 29

Formal qualities and formalism 29

Formal qualities in current work in environmental aesthetics 30

Background on the significance assigned to formal qualities 31

Formal qualities in the natural environment 34

Conclusion 38

Notes 39

4 Appreciation and the natural environment 41

The appreciation of art 41

Some artistic models for the appreciation of nature 42

An environmental model for the appreciation of nature 47

Conclusion 51

Notes 51

5 Nature, aesthetic judgment, and objectivity 55

Nature and objectivity 55

Walton’s position 56

Nature and culture 58

Nature and Walton’s psychological claim 60

The correct categories of nature 63

Conclusion 68

Notes 69

6 Nature and positive aesthetics 73

The development of positive aesthetics 73

Nature appreciation as non-aesthetic 76

Positive aesthetics and sublimity 79

Positive aesthetics and theism 82

Science and aesthetic appreciation of nature 85

Science and appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature 88

Science and positive aesthetics 91

Notes 95

7 Appreciating art and appreciating nature

103

The concept of appreciation 103

Appreciating art: design appreciation 108

Appreciating art: order appreciation 110

Appreciating nature: design appreciation 115

Appreciating nature: order appreciation 118

vi

Conclusion 122

Notes 123

PART II Landscapes, art, and architecture 127

8 Between nature and art 129

The question of aesthetic relevance 129

Objects of appreciation and aesthetic necessity 131

Between nature and art: appreciating other things 133

Notes 135

9 Environmental aesthetics and the dilemma of aesthetic

education

139

The eyesore argument 139

The dilemma of aesthetic education 140

The natural 141

The aesthetically pleasing 143

Life values and the eyesore argument 144

Conclusion 147

Notes 148

10 Is environmental art an aesthetic affront to nature? 151

Environmental works of art 151

Environmental art as an aesthetic affront 153

Some replies to the affront charge 156

Some concluding examples 159

Notes 162

11 The aesthetic appreciation of Japanese gardens 165

The dialectical nature of Japanese gardens

165

The appreciative paradox of Japanese gardens 168

Conclusion 172

Notes 173

12 Appreciating agricultural landscapes 177

vii

Traditional agricultural landscapes 177

The new agricultural landscapes 179

Difficult aesthetic appreciation and novelty 184

Appreciating the new agricultural landscapes 187

Conclusion 190

Notes 191

13 Existence, location, and function: the appreciation of

architecture

197

Architecture and art 197

To be or not to be: Hamlet and Tolstoy 199

Here I stand: to fit or not to fit 203

Form follows function and fit follows function 208

Function, location, existence: the path of appreciation 212

Notes 215

14 Landscape and literature 219

Hillerman’s landscapes and aesthetic relevance 219

Classic formalism and postmodern landscape appreciation 221

Formal descriptions and ordinary descriptions 222

Other factual landscape descriptions 224

The analogy with art argument 226

Nominal descriptions 228

Imaginative descriptions and cultural embeddedness 230

Mythological landscape descriptions 232

Literary landscape descriptions 235

The analogy with art argument again 237

Conclusion 239

Notes 240

Index 243

viii

ILLUSTRATIONS

1 Peacock Skirt, by Aubrey Beardsley (1894) 22

2 The Grand Tetons, Wyoming 56

3 Asphalt Rundown, by Robert Smithson (1969), Rome 154

4 Time Landscape, by Alan Sonfist (1965–78), New York City 162

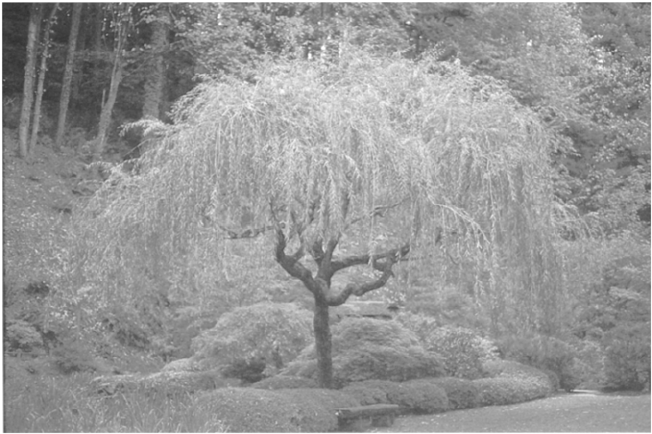

5 Willow in the Japanese garden, Portland 171

6 A traditional farmstead, Minnesota 180

7 The new agricultural landscape, Saskatchewan 180

8 Autumn Foliage, by Tom Thomson (1916) 198

9 The AT&T Building, by Philip Johnson/John Burgee (1980–83), New

York City

200

10 Ship Rock and the Long Black Ridges, New Mexico 235

PREFACE

The material in this volume spans a period of roughly twenty years and reflects my

continuing interest in the aesthetics of the environment.

A number of the chapters of the volume have been previously published as essays

in books or journals. Except for slight changes required to make corrections,

eliminate redundancies, or indicate connections, these essays are reprinted much as

they initially appeared. I have elected this alternative both because it best maintains

the integrity and quality of the individual pieces and because I think that even in

their original form, the essays come together to constitute a unified line of thought.

The introductory chapters for the two parts of the volume, Chapters 1 and 8,

present overviews and help to further unify the material. Moreover, the notes for

these two chapters provide extensive cross-referencing among the remaining

chapters and position them within the current literature in the field. In addition to

Chapters 1 and 8, two other chapters, Chapters 2 and 14, have not previously

appeared in print.

Allen Carlson

Edmonton, Canada, 1998

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I acknowledge and thank the editors and the publishers of the following books and

journals for permission to use material that originally appeared in them: For portions

of the general Introduction and of Chapter 1, by permission of, respectively, Basil

Blackwell, Routledge, and Oxford University Press, D. Cooper (ed.) A Companion

to Aesthetics, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1992, pp. 142–4; E.Craig (ed.) The Routledge

Encyclopedia of Philosophy, London, Routledge, 1998, vol. 6, pp. 731–5; and

M.Kelly (ed.) The Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, New York, Oxford University Press,

1998, vol. 3, pp. 346–9. For Chapters 3 and 9, by permission of the University of

Illinois Press, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 1979, vol. 13, pp. 99–114 and

1976, vol. 10, pp. 69–82. For Chapters 4, 5, and 12, by permission of the

University of Wisconsin Press, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1979, vol.

37, pp. 267–76; 1981, vol. 40, pp. 15–27, and 1985, vol. 43, pp. 301–12. For

Chapter 6, by permission of Environmental Philosophy, Inc., Environmental Ethics,

1984, vol. 6, pp. 5–34. For Chapter 7, by permission of Cambridge University

Press, S.Kemal and I.Gaskell (eds) Landscape, Nature Beauty and the Arts,

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993, pp. 199–227. For Chapter 10, by

permission of the University of Calgary Press, The Canadian Journal of Philosophy,

1986, vol. 16, pp. 635–50. For Chapter 11, by permission of Oxford University

Press, The British Journal of Aesthetics, 1997, vol. 37, pp. 47–56. For Chapter 13, by

permission of Editions Rodopi B.V., M.Mitias (ed.) Philosophy and Architecture,

Amsterdam, Rodopi, 1994, pp. 141–64.

I also express my appreciation to the following by the courtesy of whom it was

possible to include illustrations 2, 3, 4, 8, and 9: respectively, Corbis/ Ansel Adams

Publishing Rights Trust, The John Weber Gallery, Alan Sonfist, The National

Gallery of Canada, and American Telephone and Telegraph.

I thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the

University of Alberta for financial support for the writing of some of the material in

this volume.

I also thank my editors at Routledge for their assistance and advice.

Above all, I thank and express my appreciation to my friends and acquaintances

in the discipline, to my colleagues in the Department of Philosophy at the

University of Alberta, and to the members of my family for their support and

encouragement.

INTRODUCTION

Aesthetics and the environment

What is “environmental aesthetics”?

Aesthetics is the area of philosophy that concerns our appreciation of things as they

affect our senses, and especially as they affect them in a pleasing way. As such it

frequently focuses primarily on the fine arts, the products of which are traditionally

designed to please our senses. However, much of our aesthetic appreciation is not

confined to art, but directed toward the world at large. We appreciate not only art,

but also nature—broad horizons, fiery sunsets, and towering mountains. Moreover,

our appreciation reaches beyond pristine nature to our more mundane

surroundings: the solitude of a neighborhood park on a rainy evening, the chaos of a

bustling morning marketplace, the view from the road. Thus, there is a need for an

aesthetics of the environment, for in such cases our aesthetic appreciation

encompasses our surroundings: our environment. The environment may be more or

less natural, large or small, mundane or exotic, but in each such case it is an

environment that we appreciate. Such appreciation is the subject matter of

environmental aesthetics.

The nature of environmental aesthetics

The fact that the focus of aesthetic appreciation is an environment signals several

important dimensions of such appreciation which in turn determine the nature of

environmental aesthetics. The first of these dimensions follows from the very fact

that the object of appreciation, the “aesthetic object,” is our environment, our

surroundings. Thus, we as appreciators are immersed within the object of our

appreciation. This fact has a number of ramifications: not only are we in what we

appreciate but what we appreciate is also that from which we appreciate. If we

move, we move within the object of our appreciation and thereby change our

relationship to it and at the same time change the object itself. Moreover, since it is

our surroundings, the object of appreciation impinges upon all our senses. As we

occupy it or move through it, we see, hear, feel, smell, and perhaps even taste it. In

short, the experience of the environmental object of appreciation from which

aesthetic appreciation must be fashioned is initially intimate, total, and engulfing.

These dimensions of our experience are intensified by the unruly and chaotic

nature of the object of appreciation itself. It is not the more or less discrete, stable,

and self-contained object of traditional art, but rather an environment.

Consequently, not only does it change as we move within it, it changes of its own

accord. Environments are constantly in motion, in both the short and long term. If

we remain motionless, the wind yet brushes our face and the clouds yet pass before

our eyes. And with time changes continue without limit: night falls, days pass,

seasons come and go. Moreover, environments not only move through time, they

extend through space, and again without limit. There are no boundaries for our

environment; as we move, it moves with us and changes, but does not end. Indeed,

it continues unending in every direction. In other words, the environmental object

of appreciation is not “framed” as are traditional works of art, neither in time as are

dramatical works or musical compositions nor in space as are paintings or

sculptures.

These differences between environments and traditional artistic objects relate to a

deeper difference between the two. Works of art are the products of artists. The

artist is quintessentially a designer, creating a work by embodying a design in an

object. Thus, works of art are tied to their designers both causally and conceptually:

what a work is and what it means follows from its designer and its design. However,

environments typically are not the products of designers and typically have no

design. Rather they come about “naturally,” they change, grow, and develop by

means of natural processes. Or they come about by means of human agency, but

even then only rarely are they the result of a designer embodying a design. In short,

the paradigm of the environmental object of appreciation is unruly in yet another

way: neither its nature nor its meaning are determined by a designer and a design.

The upshot is that in our aesthetic appreciation of the world at large we are

confronted by, if not intimately and totally engulfed in, something that forces itself

upon all our senses, is constantly in motion, is limited neither in time nor in space,

and is constrained concerning neither its nature nor its meaning. We are immersed

in a potential object of appreciation and our task is to achieve aesthetic appreciation

of that object. Moreover, the appreciation must be fashioned anew, with neither the

aid of frames, the guidance of designs, nor the direction of designers. Thus, in our

aesthetic appreciation of the world at large we must begin with the most basic

questions, those of exactly what to aesthetically appreciate and how to appreciate it.

These questions set the agenda for environmental aesthetics; the field essentially

concerns the issue of what resources, if any, are available for answering them.

The two basic orientations in environmental aesthetics

The questions of what and how to aesthetically appreciate in an environment

generate a number of different approaches, but at the most fundamental level two

main points of view can be identified. The first may be characterized as subjectivist

or perhaps as skeptical. In essence, it holds that since in the appreciation of

environments we seemingly lack the resources normally involved in aesthetic

xiii

appreciation, these questions cannot be properly answered. In other words, since we

lack resources such as frames, designs, and designers as well as the guidance they

provide, then we must embrace either subjectivism or skepticism: either there is no

appropriate or correct aesthetic appreciation of environments or such appreciation

as there is, is not real aesthetic appreciation. Concerning the world at large, as

opposed to works of art, the closest we come to appropriate aesthetic appreciation is

simply to open ourselves to being immersed, respond as we will, and enjoy what we

can. And the question of whether or not the resultant experience is appropriate in

some sense, or even aesthetic in any sense, is not of any importance.

A second basic point of view may be characterized as objectivist. In essence, it

argues that, in addressing the what and how questions, there are in fact two

resources to draw upon: the appreciator and the object of appreciation. Thus, roles

that are played in the appreciation of traditional art objects by designer and design

must be played in the aesthetic appreciation of an environment by either or both of

these two resources. In such appreciation the role of designer is typically taken up by

the appreciator and that of design by the object. In other words, in our aesthetic

appreciation of the world at large we as appreciators typically play the role of artist

and let the world provide us with something like a design. Thus, when confronted

by an environment, we select the senses relevant to its appreciation and set the

frames that limit it in time and space. Moreover, as designer plays off against design,

so too in selecting and setting we play off against the nature of the environment we

confront. In this way the environment by its own nature provides the analogue of a

design—we might say it provides its own design. Thus, it offers the necessary

guidance in light of which we, by our selecting and setting, can appropriately

answer the questions of what and how to appreciate. We thereby fashion our

initially engulfing if not overwhelming experience of an environment into appropriate

and genuine aesthetic appreciation.

In disputes between subjectivist or skeptical positions and more objectivist ones,

the burden of proof typically falls on the latter. To make its case, the objectivist

account must be elaborated and supported by arguments and examples. The basic

idea of the objectivist point of view is that our appreciation is guided by the nature

of the object of appreciation. Thus, information about the object’s nature, about its

genesis, type, and properties, is necessary for appropriate aesthetic appreciation. For

example, in appreciating a natural environment such as an alpine meadow, it is

important to know, for instance, that it survives under constraints imposed by the

climate of high altitude. With such knowledge comes the understanding that

diminutive size in flora is an adaptation to such constraints. This knowledge and

understanding guides our framing of the environment so that, for example, we avoid

imposing inappropriately large frames, which may cause us simply to overlook

miniature wild flowers. In such a case we might neither appreciatively note their

remarkable adjustment to their situation nor attune our senses to their subtle

fragrance, texture, and hue. Similarly, in appreciating human-altered environments

such as those of modern agriculture, knowledge about, for example, the functional

utility of cultivating huge fields devoted to single crops is aesthetically relevant. Such

xiv

knowledge encourages us to enlarge and adjust our frames, our senses, and even our

attitudes. As a result we may more appreciatively accommodate the vast uniform

landscapes that are the inevitable result of such farming practices.

The scope of environmental aesthetics

Whether they endorse a subjectivist or an objectivist point of view, both basic

orientations in environmental aesthetics recognize the array of special problems that

confronts the field. Similarly, both recognize the expansive scope of the field itself.

The scope may be characterized in terms of three continuums.

On the first, the subject matter of environmental aesthetics stretches from

pristine nature to the very limits of the most traditional art forms, and by some

accounts even expands to include the latter. On this continuum the things treated

by environmental aesthetics range from wilderness areas, through rural landscapes

and countrysides, to cityscapes, neighborhoods, market places, shopping centers,

and beyond. Thus, within the genus of environmental aesthetics fall a number of

different species, such as the aesthetics of nature, landscape aesthetics, the aesthetics

of cityscapes and urban design, and perhaps the aesthetics of architecture, if not that

of art itself.

The second continuum in terms of which the scope of environmental aesthetics

may be characterized ranges over size. Many environments that are typical objects of

our aesthetic appreciation, especially those that surround and threaten to engulf us,

are very large: a dense old growth forest, a seemingly endless field of wheat, the

downtown of a big city. But environmental aesthetics also focuses on smaller and

more intimate environments, such as our backyard, our office, and our living room.

And perhaps the scope extends even to diminutive environments, such as we may

encounter when we turn over a rock or when traveling with a microscope into a

drop of pond water. Such tiny environments, although not physically surrounding,

are yet totally engaging.

The third continuum is closely related to the second. It ranges from the

extraordinary to the ordinary, from the exotic to the mundane. Just as

environmental aesthetics is not limited to the large, it is likewise not limited to the

spectacular. Ordinary scenery, commonplace sights, and our day-to-day experiences

are also proper objects of aesthetic appreciation. As such they not only fall under the

scope of environmental aesthetics, but also, in light of becoming objects of aesthetic

appreciation, hopefully become somewhat less ordinary.

In spite of the expansive scope of environmental aesthetics, a basic assumption of

the field is that every environment, natural, rural, or urban, large or small, ordinary

or extraordinary, offers much to see, to hear, to feel, much to aesthetically

appreciate. In short, the different environments of the world at large are as

aesthetically rich and rewarding as are works of art. Nonetheless, there are, as noted,

special issues in aesthetic appreciation posed by the very nature of environments, by

the fact that they are our surroundings, that they are unruly and chaotic objects of

appreciation, and that we are plunged into them without appreciative guidelines.

xv

The chapters that follow embrace this basic assumption and recognize these special

issues. They address the issues from an objectivist point of view.

xvi

Part I

THE APPRECIATION OF NATURE

2

1

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE

A brief historical overview

In the Western world there has been since antiquity a tradition of viewing art as the

mirror of nature. However, the idea of aesthetically appreciating nature itself is

sometimes traced to a less ancient origin: Petrarch’s novel passion for climbing

mountains simply to enjoy the prospect. Yet even if the aesthetic appreciation of

nature only dates from the dawn of the Renaissance, its development from that time

to the present has been uneven and episodic. Initially, nature’s appreciation as well

as its philosophical investigation were hamstrung by religion. The reigning religious

tradition could not but deem nature an unworthy object of aesthetic appreciation,

for it saw mountains as despised heaps of wreckage left by the flood, wilderness

regions as fearful places for punishment and repentance, and all of nature’s workings

as poor substitutes for the perfect harmony lost in humanity’s fall. It took the rise of

a secular science and equally secular art forms to free nature from such associations

and thereby open it for aesthetic appreciation. Thus, in the Western world the

evolution of aesthetic appreciation of nature has been intertwined with both the

objectification of nature achieved by science and the subjectification of it rendered

by art.

Although the scientific objectification of nature had earlier origins, the

connection between aesthetic appreciation of nature and scientific objectivity dates

from early in the eighteenth century. At that time, British aestheticians initiated a

tradition that gave theoretical expression to this connection. Empiricist thinkers,

such as Joseph Addison and Francis Hutcheson, took nature rather than art as the

ideal object of aesthetic experience and developed the notion of disinterestedness as

the mark of such experience. In the course of the century, this notion was elaborated

such as to exclude from aesthetic experience an ever-increasing range of associations

and conceptualizations. Thus, the objects of appreciation favored by this tradition,

British landscapes, were, by means of disinterested aesthetic appreciation, eventually

severed not only from religious associations, but from any appreciator’s personal,

moral, and economic interests. The upshot was a mode of aesthetic appreciation

that looked upon the natural world with an eye not unlike the distancing,

objectifying eye of science. In this way, the tradition laid the groundwork for the

idea of the sublime. By means of the sublime even the most threatening of nature’s

manifestations, such as mountains and wilderness, could be distanced and

appreciated, rather than simply feared and despised.

However, the notion of disinterestedness not only laid the groundwork for the

sublime, it also cleared the ground for another, quite different idea, that of the

picturesque. This idea secured the connection between aesthetic appreciation of

nature and the subjective renderings of nature in art. The term “picturesque”

literally means “picture-like” and indicates a mode of appreciation by which the

natural world is divided into artistic scenes. Such scenes aim in subject matter or in

composition at ideals dictated by the arts, especially poetry and landscape painting.

Thus, while disinterestedness and the sublime stripped and objectified nature, the

picturesque dressed it in a new set of subjective and romantic images: a rugged cliff

with a ruined castle, a deep valley with an arched bridge, a barren outcropping with

a crofter’s cottage. Like disinterestedness and the sublime, the picturesque had its

roots in the theories of the early eighteenth century aestheticians, such as Addison,

who thought that what he called the “works of nature” were more appealing when

they resembled works of art. However, picturesque appreciation did not culminate

until later in the century when it was popularized primarily by William Gilpin and

Uvedale Price. At that time, it became the reigning aesthetic ideal of English tourists

who pursued picturesque scenery in the Lake District and the Scottish Highlands.

Indeed, the picturesque remains the mode of aesthetic appreciation associated with

the form of tourism that sees and appreciates the natural world primarily in light of

renderings of nature typical of travel brochures, calendar photos, and picture

postcards.

After the close of the eighteenth century, the picturesque lingered on as a popular

mode of aesthetic appreciation of nature. However, the philosophical study of the

aesthetics of nature, after the flowering of that century, went into steady decline.

Many of the main ideas, such as the idea of the sublime, the notion of

disinterestedness, and the theoretical centrality of nature rather than art, reached

their climax with Kant. In his third critique some of these ideas received such

exhaustive treatment that a kind of closure was seemingly achieved. Following Kant,

a new world order was initiated by Hegel. In this world, art was a means to the

Absolute, and it rather than nature was destined to became the favored subject of

philosophical aesthetics.

However, even as the theoretical study of the aesthetics of nature declined, a new

view of nature was initiated that eventually gave rise to a different kind of aesthetic

appreciation. This mode of appreciation has its roots in the North American

tradition of nature writing, as exemplified by Henry David Thoreau. In the middle

of the nineteenth century, it was reinforced by the work of George Perkins Marsh

and his recognition that humanity is the major cause of the destruction of nature’s

beauty. It achieved its classic realization at the end of the century with American

naturalist John Muir. Muir saw all nature and especially wild nature as aesthetically

beautiful and found ugliness only where nature was subject to human intrusion.

4 AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

These ideas strongly influenced the North American wilderness preservation

movement and continue to shape the aesthetic appreciation of nature associated

with contemporary environmentalism. This kind of appreciation may be called

positive aesthetics.

1

In so far as positive aesthetic appreciation eschews humanity’s

marks on the natural landscape, it is somewhat the converse of picturesque

appreciation with its delight in signs of human presence. Thus, it has become the

rival of the picturesque as the popular mode of aesthetic appreciation of nature,

although contemporary nature appreciation frequently involves a somewhat uneasy

balance between the two different modes.

In spite of the developments in popular appreciation of nature in the nineteenth

and twentieth century, however, philosophical aesthetics, with few exceptions,

ignored nature throughout most of this period. In the nineteenth century Schelling

and a scattering of thinkers of the Romantic Movement considered the aesthetics of

nature to some extent, and in the first half of the twentieth century George

Santayana and John Dewey each discussed it. But, by and large, in so far as

aesthetics was pursued, it was completely dominated by an interest in art. Thus, by

the mid-twentieth century, within the analytic tradition, philosophical aesthetics

was virtually equated with philosophy of art. The major textbook in aesthetics at

this time was subtitled Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism and major aesthetics

anthologies bore titles such as Art and Philosophy and Philosophy Looks at the Arts.

2

Moreover, when aesthetic appreciation of nature was mentioned, it was treated, by

comparison with that of art, as a messy, subjective business of little philosophical

significance. However, in the second half of the twentieth century this situation was

destined to change.

A brief overview of contemporary positions

Many of the issues in contemporary work on the aesthetics of nature are foreshadowed

in one article: Ronald W. Hepburn’s seminal “Contemporary Aesthetics and the

Neglect of Natural Beauty.”

3

After noting that by essentially reducing aesthetics to

the philosophy of art, analytic aesthetics virtually ignores the natural world,

Hepburn sets the agenda for the discussion of the late twentieth century. He argues

that aesthetic appreciation of art frequently provides misleading guidelines for our

appreciation of nature. Yet he observes that there is in the aesthetic appreciation of

nature, as in appreciation of art, a distinction between appreciation which is only

trivial and superficial and that which is serious and deep. He furthermore suggests

that with nature such serious appreciation may require different approaches that can

accommodate not only nature’s indeterminate and varying character, but also both

our multi-sensory experience and our diverse understanding of it.

The contemporary discussion of the aesthetics of nature thus stresses different

approaches to or models for the appreciation of nature: models intended to capture

the essence of appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature. Certain more traditional

models that are rather directly related to the aesthetic appreciation of the arts are

seemingly inadequate. Two such models may be called the object model and the

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE 5

landscape model. The former pushes nature in the direction of sculpture and the

latter treats it as similar to landscape painting. Thus, the object model focuses

aesthetic appreciation primarily on natural objects and dictates appreciation of such

objects rather as we might appreciate pieces of abstract sculpture, mentally or

physically extracting them from their contexts and dwelling on their formal

properties. On the other hand, the landscape model, following in the tradition of

the picturesque noted in the first section of this chapter, mandates appreciation of

nature as we might appreciate a landscape painting. This requires seeing it to some

extent as a two-dimensional scene and again dwelling largely on formal properties.

Neither of these models fully realize serious, appropriate appreciation of nature for

each distorts the true character of nature. The former rips natural objects from their

larger environments while the latter frames and flattens them into scenery.

Moreover, in focusing mainly on formal properties, both models neglect much of

our normal experience and understanding of nature.

4

Although the aesthetic appreciation of the arts does not directly provide adequate

models for the appreciation of nature, it yet suggests some of what is required in a

more adequate model. In serious, appropriate aesthetic appreciation of works of art,

it is essential that we appreciate works as what they in fact are and in light of

knowledge of their real natures. Thus, for instance, serious, appropriate aesthetic

appreciation of the Guernica (1937) requires that we appreciate it as a painting and

moreover as a cubist or neo-cubist painting, and therefore that we appreciate it in

light of our knowledge of paintings in general and of cubist paintings in particular.

This suggests a third model for the aesthetic appreciation of nature, the natural

environmental model. This model, which I develop throughout Part I of this

volume, recommends two things. First, that, as in our appreciation of works of art,

we must appreciate nature as what it in fact is, that is, as natural and as an environment.

Second, it recommends that we must appreciate nature in light of our knowledge of

what it is, that is, in light of knowledge provided by the natural sciences, especially

the environmental sciences such as geology, biology, and ecology. The natural

environmental model thus accommodates both the true character of nature and our

normal experience and understanding of it.

5

Nonetheless, the natural environmental model may be thought not to

characterize our appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature completely accurately.

Although it does not, as the object and the landscape models, distort nature itself, it

may yet be thought to somewhat misrepresent our appreciation of nature. Its

emphasis on scientific knowledge gives such appreciation a highly cognitive and

what may be judged an overly intellectual quality. In contrast to the cognitive

emphasis of the natural environmental model, a fourth model, the engagement model,

stresses the contextual dimensions of nature and our multi-sensory experience of it.

Viewing the environment as a seamless unity of organisms, perceptions, and places,

the engagement model beckons us to immerse ourselves in our natural environment

in an attempt to obliterate traditional dichotomies such as subject and object, and

ultimately to reduce to as small a degree as possible the distance between ourselves

6 AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

and nature. In short, aesthetic experience is taken to involve a total immersion of

the appreciator in the object of appreciation.

6

The engagement model calls for the absorption of the appreciator into the

natural environment. Perhaps in doing so it goes too far. There are two main

difficulties. First, in attempting to eliminate any distance between ourselves and

nature, the engagement model may lose that by reason of which the resultant

experience is aesthetic. As noted in the first section of this chapter, within the

Western tradition the very notion of the aesthetic is conceptually tied to

disinterestedness and the idea of distance between the appreciator and the

appreciated, The second difficulty is that in attempting to obliterate dichotomies

such as that between subject and object, the engagement model may also lose the

possibility of distinguishing between trivial, superficial appreciation and that which

is serious and appropriate. This is because serious, appropriate appreciation revolves

around the object of appreciation and its real nature, while superficial appreciation

frequently involves only whatever the subject happens to bring to the experience. In

short, without the subject/object distinction, aesthetic appreciation of nature is in

danger of degenerating into little more than a subjective flight of fancy.

Another view that also seems to diverge from the natural environmental model is

the arousal model. This model challenges the central place the natural

environmental model grants to scientific knowledge in aesthetic appreciation of

nature. The arousal model holds that we may appreciate nature simply by opening

ourselves to it and thus being emotionally aroused by it. The view contends that this

less intellectual, more visceral experience of nature is a way of legitimately

appreciating nature without involving any knowledge gained from science. Unlike

the engagement model, this model does not call for a total immersion in nature, but

only for an emotional relationship with it based on our common, everyday

knowledge and experience of it. Consequently, in contrast to the engagement

model, the arousal model does not lose the right to call its experience of nature

aesthetic. Nor does it undercut the distinction between trivial and serious

appreciation of nature, even though the appreciation it stresses may be more the

former than the latter. However, the contrast between the arousal model and the

natural environmental model is less clear. If we recognize our scientific knowledge

of the natural world as only a finer-grained and theoretically richer version of our

common, everyday knowledge of it, and not as something essentially different in

kind, then the difference between the arousal model and the natural environmental

model is mainly one of emphasis. Both models track the appreciation of nature,

although the arousal model focuses on the more common, less cognitively rich, and

perhaps less serious end of the continuum.

7

A more fundamental challenge to the natural environmental model comes from

what may be called the mystery model of nature appreciation. This view holds that

the natural environmental model, in requiring that we must have knowledge of

what we appreciate, has no place for the way in which nature is alien, aloof, distant,

and unknowable. It contends that the only appropriate experience of nature is a

sense of mystery involving a state of appreciative incomprehension, a sense of not

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE 7

belonging to and of being separate from nature. However, the mystery model faces

major difficulties. With only mystery and aloofness, there seems to be no grounding

for appreciation of any kind, let alone aesthetic appreciation. The mystery and

aloofness of nature is a gulf, an emptiness, between us and nature; it is that by which

we are separate from nature. Thus, mystery itself cannot constitute a means by

which we can attain any appreciation of nature whatsoever. In short, insofar as

nature is unknowable, it is also beyond aesthetic appreciation. However, even

though mystery and aloofness cannot support appreciation, they can support

worship. Thus, perhaps the mystery model should be characterized not as an

aesthetic of nature, but rather as a religious approach to nature. If this is the case,

then rather than revealing a dimension of our appropriate aesthetic appreciation of

nature, the mystery model leaves the realm of the aesthetic altogether.

8

If the mystery model of nature appreciation moves such appreciation outside the

realm of the aesthetic, it does so unintentionally. However, the possibility that our

appreciation of nature is not aesthetic is expressly embraced as the central tenet of

the nonaesthetic model of nature appreciation. This view constitutes a radical

alternative to all other models in explicitly claiming that nature appreciation is not a

species of aesthetic appreciation. It holds that aesthetic appreciation is

paradigmatically appreciation of works of art and is minimally appreciation of

artifacts, of that which is human-made. Thus, in this view the appreciation of

nature itself cannot be aesthetic appreciation of any kind whatsoever.

9

However,

such a view is deeply problematic. The view finds some support in the tendency in

analytic aesthetics noted in the first section of this chapter, that is, the tendency to

reduce all of aesthetics to philosophy of art. Yet the view remains essentially

counterintuitive. Many of our fundamental paradigms of aesthetic appreciation are

instances of appreciation of nature, such as our appreciation of the radiance of a

glowing sunset, the grace of a bird in flight, or the simple beauty of a flower.

Moreover, the Western tradition in aesthetics, not to mention other traditions, such

as the Japanese, is committed to a doctrine that explicitly excludes the nonaesthetic

model of nature appreciation: the doctrine that, as one writer puts it, anything that

can be viewed can be viewed aesthetically.

10

There is nonetheless a grain of truth contained in the nonaesthetic model of

nature appreciation that is worth preserving. The nonaesthetic model makes a virtue

of what the mystery model encounters unintentionally: the fact that the more

removed, the more separate, something is from humankind and its artifactualization,

the more problematic is its aesthetic appreciation. The limiting case, inadvertently

illuminated by the mystery model, is the complete impossibility of aesthetically

appreciating the totally unknowable. The insight contained in the nonaesthetic

model is thus that some degree of artifactualization is necessary for aesthetic

appreciation. However, what this model fails to recognize is that our human

conceptualization and understanding of nature is itself a minimal form of

artifactualization. And although minimal, it is yet adequate to underwrite aesthetic

appreciation. To aesthetically appreciate the natural world, we do not need to

actually make it, as we make works of art; nor do we need to conceptualize it in

8 AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

artistic categories, as is done by the object and landscape models. When we cast the

conceptual net of common-sense and scientific understanding over nature we do

enough to it to make possible its aesthetic appreciation. This fact lends support to

some other models, such as the natural environment model, for it suggests that

granting a special place in nature appreciation to at least our common-sense and

scientific knowledge of nature may be a necessary condition for providing an

adequate account of serious, appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature.

However, the realization that human conceptualization and understanding is a

form of artifactualization adequate for underwriting genuine aesthetic appreciation

of nature opens the door to further possibilities. The conceptual net of common-sense

and scientific understanding is not the only one we cast over nature. There are also

numerous other nets woven by human culture in its many forms—nets woven not

only by art, but also by literature, folklore, religion, and myth. This realization

suggests the possibility of what may be called a postmodern model of nature

appreciation. Such a view would compare nature to a text, contending that in

reading a text we appropriately appreciate not just the meaning its author intended,

but any of various meanings that it may have acquired or that we may find in it.

And, moreover, none of these possible meanings has priority; no reading of a text is

privileged. Thus, on such a postmodern model, whatever cultural significance

nature may have acquired and that we may find in it, the rich and varied deposits

from our art, literature, folklore, religion, and myth, would all be accepted as proper

dimensions of our aesthetic appreciation of nature. And of such dimensions none

would be given priority; no particular appreciation would be privileged as more

serious or more appropriate than any other.

11

The possibility of a postmodern model of nature appreciation focuses attention

on the many layers of human deposit that overlay pure nature. These layers range

from the thin film of common sense, through the rich stratum of science, to the

abundant accumulations of culture. In our encounters with nature we confront this

diversity and a postmodern model would eagerly welcome it all. In sharp contrast,

some other models, such as the engagement model and the mystery model, strive

toward attempting to appreciate pure, unadulterated nature, to look on nature bare,

as Euclid looked on beauty. But the nonaesthetic model demonstrates that to go too

far in this direction is to go beyond the realm of the aesthetic, making any aesthetic

appreciation of nature impossible. Nonetheless, contained in the purist’s inclination

is the antidote for the potential excesses of a postmodern model. To achieve a

balanced understanding of the situation, we must keep in mind that, as with

appreciation of art, serious appreciation of nature means appreciating it as what it in

fact is; and yet at the same time we must recognize that this also means appreciating

nature as what it is for us. This idea limits yet enriches what is involved in

appropriate aesthetic appreciation. Contra a postmodern model, it is not the case

that just any fanciful reverie we happen to bring to nature will do as well as anything

else; and contra the purist, nature is what it is for us, is what we have made of it. To

miss or deny this latter fact is to miss or deny much of the richness that serious,

appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature has to offer.

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE 9

The idea that nature is what it is for us, is what we have made of it, widens the

scope of appropriate aesthetic appreciation, but it also constrains any view such as a

postmodern model. In part this is because neither nature nor we are one unitary

thing. It follows that not all of humankind’s cultural deposit is aesthetically

significant either to all parts of nature or for all of humankind. For any particular

part of nature and for any particular appreciator, some of the cultural overlay is

relevant, is indeed necessary for serious appreciation, while much of it is not, is

indeed little better than fanciful daydreams. In light of this, perhaps what might be

called a pluralist model of nature appreciation should supplant a postmodern

model. A pluralist model would accept the diversity and the richness of the cultural

overlay in which a postmodern model delights. However, such a model would also

recognise, first, that for any particular part of nature only a small part of that

cultural overlay is really relevant to serious, appropriate appreciation, and, second,

that for any particular appreciator only a small part of the overlay can truly be

claimed as his or her own. A pluralist model would endorse diversity, but yet would

hold that in appropriate aesthetic appreciation, not all nature either can or should

be all things to all human beings.

12

Although a pluralist model would thus restrict the role of our cultural overlay in

appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature, any such restriction need not apply

equally to all layers of the human deposit. Perhaps the more basic layers, those of

common sense and science, are dimensions of appropriate appreciation of all of

nature by any of its appreciators. Thus, even in light of the possibility of a pluralist

model, models such as the arousal model and the natural environmental model

maintain a special place as general guides to appropriate aesthetic appreciation of

nature. This is because these models concentrate on the most fundamental layers of

the human overlay, those constituting the very foundations of our experience and

understanding of nature. However, there may be other layers relevant to our

appreciation of nature that are equally universal, although they may constitute the

spires rather than the foundations of the human deposit. Such layers are the focus of

the metaphysical imagination model of nature appreciation. According to this view,

our imagination interprets nature as revealing metaphysical insights: insights about

the whole of experience, about the meaning of life, about the human condition,

about humankind’s place in the cosmos. Thus, this model includes in appropriate

aesthetic appreciation of nature those abstract meditations and speculations about

the true nature of reality that our encounters with nature frequently engender in

us.

13

The metaphysical imagination model invites us to entertain in our aesthetic

appreciation of nature deep meditations and possibly wild speculations, but again the

question of what is and what is not relevant arises. Which of such meditations and

speculations are only trivial and fanciful and which are serious and sustainable? In

essence, the question is again that of what does and what does not actually focus on

and reveal nature as it in fact is. However, in the context of the metaphysical

imagination model, this question arises as a general and profound question about

the real nature of the natural world. Thus, the metaphysical imagination model

10 AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

indicates a new agenda for the aesthetics of nature, for it suggests that in order to

ultimately adjudicate among the different models of aesthetic appreciation of

nature, we must first resolve more fundamental metaphysical issues about the true

character of nature and about our proper place in its grand design.

14

The new agenda for the aesthetics of nature indicated by the metaphysical

imagination model points to the need to address fundamental issues about the

nature of the natural world and our place in it. Thus, this agenda suggests that

primary consideration should be given to those models of aesthetic appreciation of

nature that most directly deal with such issues. As noted in the first section of this

chapter, within the Western world the development of the aesthetic appreciation of

nature has been closely intertwined with the growth of the natural sciences. And, of

course, within the Western world, it is science that is taken to most successfully

address fundamental issues about the true character of the natural world and

humanity’s place in it. Consequently, the new agenda points to the centrality of that

model which ties appropriate aesthetic appreciation of nature most closely to

scientific knowledge: the natural environmental model.

15

The natural environmental model: some further ramifications

In addition to directly speaking to the new agenda for the aesthetics of nature, the

natural environmental model has a number of other ramifications worth noting.

Some of these concern what is called applied aesthetics, in particular popular

appreciation of nature as practiced not only by tourists but by each of us in our

daily pursuits. As noted in the first section of this chapter, such appreciation

frequently involves a somewhat uneasy balance between two different modes: on the

one hand, that flowing from the tradition of the picturesque and currently

embodied in artistic and cultural models, such as the landscape model, and, on the

other, the positive aesthetics mode growing from the tradition of thinkers such as

Thoreau and Marsh and fully realized in John Muir. The balance between the two

modes of appreciation is to some degree tipped in favor of the latter by the natural

environmental model in that this model provides theoretical underpinnings for

positive aesthetics. When nature is aesthetically appreciated in virtue of the natural

and environmental sciences, positive aesthetic appreciation is singularly appropriate,

for, on the one hand, pristine nature—nature in its natural state—is an aesthetic

ideal and, on the other, as science increasingly finds, or at least appears to find,

unity, order, and harmony in nature, nature itself, when appreciated in light of such

knowledge, appears more fully beautiful.

16

Other ramifications of the natural environmental model are more directly

environmental and ethical. Many of the other models for the aesthetic appreciation

of nature are frequently condemned as totally anthropocentric, as not only anti-

natural but also arrogantly disdainful of environments that do not conform to

artistic and cultural ideals and preconceptions. The root source of these

environmental and ethical concerns is that such models, as noted in the second

section of this chapter, do not always encourage appreciation of nature for what it is

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE 11

and for the qualities it has. However, since the natural environmental model bases

aesthetic appreciation on a scientific view of nature, it thereby endows aesthetic

appreciation of nature with a degree of objectivity that helps to dispel

environmental and moral criticisms, such as the charge of anthropocentrism.

Moreover, the possibility of an objective basis for aesthetic appreciation of nature

also holds out promise of more direct practical relevance in a world increasingly

engaged in environmental assessment.

17

Individuals making such assessments,

although typically not worried about anthropocentrism, are yet frequently reluctant

to acknowledge the relevance and importance of aesthetic considerations, regarding

them simply as at worst completely subjective whims or at best only relativistic,

transient, and soft-headed cultural ideals. Recognizing that aesthetic appreciation of

nature has scientific underpinnings helps to meet such doubts.

Another consequence concerns the discipline of aesthetics itself. The natural

environmental model, in rejecting artistic and other related models of nature

appreciation in favour of a dependence on common sense/scientific knowledge,

provides a blueprint for aesthetic appreciation in general. This model suggests that

in aesthetic appreciation of anything, be it people or pets, farmyards or

neighborhoods, shoes or shopping malls, appreciation must be centered on and

driven by the real nature of the object of appreciation itself.

18

In all such cases, what

is appropriate is not an imposition of artistic or other inappropriate ideals, but

rather dependence on and guidance by means of knowledge, scientific or otherwise,

that is relevant given the nature of the thing in question.

19

This turn away from

irrelevant preconceptions and toward the real nature of objects of appreciation

points the way to a general aesthetics that expands the traditional conception of the

discipline, which, as noted in the first section of this chapter, has been for much of

this century narrowly equated with the philosophy of art. The upshot is a more

universal aesthetics. This is the field of study, now generally termed environmental

aesthetics, that is delineated in the general introduction to this volume. Its relevance

to the natural world is investigated in Part I of the volume; its application beyond

the realm of nature is pursued in Part II.

Lastly, in initiating a more universal and object-centered environmental

aesthetics, the natural environmental model aids in the alignment of aesthetics with

other areas of philosophy, such as ethics, epistemology, and philosophy of mind, in

which there is increasingly a rejection of archaic, inappropriate models and a new-

found dependence on knowledge relevant to the particular phenomena in question.

For example, the natural environmental model, in its rejection of appreciative

models condemned as anthropocentric, parallels environmental ethics in the latter’s

rejection of anthropocentric models for the moral assessment of the natural world

and the replacement of such models with paradigms drawn from the environmental

and natural sciences. The general challenge is that we confront a natural world that

allows great liberty concerning the ways and means of approaching it, and that we

must therefore find the right models in order to treat it appropriately. The aesthetic

dimension of this challenge is the primary focus of the remaining chapters of the

first part of this volume.

12 AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Notes

1 I discuss positive aesthetics in more detail in “Nature and Positive Aesthetics,”

Environmental Ethics, 1984, vol. 6, pp. 5–34 (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 6).

Muir’s view is well exemplified in his Atlantic Monthly essays collected in Our National

Parks, New York, Houghton Mifflin, 1916. For an introduction to the nature of

picturesque appreciation, see M.Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque, Stanford,

Stanford University Press, 1989.

2 The volumes referred to here are Monroe C.Beardsley’s important text, Aesthetics:

Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism, New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1958,

and the first two major anthologies in analytic aesthetics, W.E.Kennick (ed.) Art and

Philosophy: Readings in Aesthetics, New York, St Martin’s Press, 1964 and Joseph

Margolis (ed.) Philosophy Looks at the Arts: Contemporary Readings in Aesthetics, New

York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1962. It is remarkable that even with a total of 1,527

pages among them, none of these volumes, each a classic of its kind, so much as

mentions the aesthetics of nature.

3 Ronald W.Hepburn, “Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect of Natural Beauty,”

in Bernard Williams and Alan Montefiore (eds) British Analytical Philosophy, London,

Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966, pp. 285–310. Ronald W.Hepburn, “Aesthetic

Appreciation of Nature,” in Harold Osborne (ed.) Aesthetics in the Modern World,

London, Thames and Hudson, 1968, pp. 49–66, is a shorter version of the same

article. Also see Ronald W.Hepburn, “Trivial and Serious in Aesthetic Appreciation of

Nature,” in Salim Kemal and Ivan Gaskell (eds) Landscape, Natural Beauty, and the

Arts, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993, pp. 65–80.

4 I critique the object and the landscape models in more detail in “Appreciation and the

Natural Environment,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1979, vol. 37, pp. 267–

76 (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 4). For an updated version of this essay, see

“Aesthetic Appreciation and the Natural Environment,” in S.Armstrong and R.

Botzler (eds) Environmental Ethics: Divergence and Convergence, Second Edition, New

York, McGraw Hill, 1998, pp. 122–31 or, for a shorter version, see the same title in

S.Feagin and P.Maynard (eds) Aesthetics, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp.

30–40.

5 The initial development of the natural environment model is in “Appreciation and the

Natural Environment,” op. cit., (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 4) and in

“Nature, Aesthetic Judgment, and Objectivity,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism,

1981, vol. 40, pp. 15–27 (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 5).

6 The original and best development of the engagement model is in Arnold Berleant,

The Aesthetics of Environment, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1992. See also

Berleant’s Art and Engagement, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1991 and Living

in the Landscape: Toward an Aesthetics of Environment, Lawrence, University Press of

Kansas, 1997. I discuss some of the philosophical underpinnings of the engagement

model in “Beyond the Aesthetic,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1994, vol. 52,

pp. 239–41 and “Aesthetics and Engagement,” British Journal of Aesthetics, 1993, vol.

33, pp. 220–27.

7 The arousal model is presented in Noel Carroll, “On Being Moved By Nature:

Between Religion and Natural History,” in Kemal and Gaskell, opt. cit., pp. 244–66.1

discuss this model in detail and develop the suggestions made here in “Nature,

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE 13

Aesthetic Appreciation, and Knowledge,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1995,

vol. 53, pp. 393–400.

8 The mystery model is found in Stan Godlovitch “Icebreakers: Environmentalism and

Natural Aesthetics,” Journal of Applied Philosophy, 1994, vol. 11, pp. 15–30. I discuss

the mystery model more fully in “Appreciating Godlovitch,” Journal of Aesthetics and

Art Criticism, 1997, vol. 55, pp. 55–7 and “Nature, Aesthetic Appreciation, and

Knowledge,” op. cit.

9 The nonaesthetic model, under the name the Human Chauvinistic Aesthetic, is

outlined in Don Mannison, “A Prolegomenon to a Human Chauvinistic Aesthetic,” in

Don Mannison, Michael McRobbie, and Richard Routley (eds) Environmental

Philosophy, Canberra, Australian National University, 1980, pp. 212–16. A similar

position is defended in Robert Elliot, “Faking Nature,” Inquiry, 1982, vol. 25, pp. 81–

93. But for a revised position see Robert Elliot, Faking Nature: The Ethics of

Environmental Restoration, London, Routledge, 1997. I discuss this kind of approach

in “Nature and Positive Aesthetics,” op. cit. (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 6)

and “Appreciating Art and Appreciating Nature,” in Kemal and Gaskell, op. cit., pp.

199–227 (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 7).

10 See Paul Ziff, “Anything Viewed,” in Antiaesthetics: An Appreciation of the Cow with

the Subtile Nose, Dordrecht, Reidel, 1984, pp. 129–39.

11 Although the postmodern model seems a recent innovation, it was suggested over one

hundred years ago by George Santayana in The Sense of Beauty, [1896], New York,

Collier, 1961, p. 99. He claims that the natural landscape is “indeterminate” and must

be “composed” by each of us by being “poetized by our day-dreams, and turned by

our instant fancy into so many hints of a fairyland of happy living and vague

adventure” before “we feel that the landscape is beautiful.” I discuss the postmodern

model in “Between Nature and Art” (in this volume, Chapter 8) and in “Landscape

and Literature” (in this volume, Chapter 14). I consider postmodern architecture in

“Existence, Location, and Function: The Appreciation of Architecture,” in M. Mitias

(ed.) Philosophy and Architecture, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 1994, pp. 141–64 (reproduced

in this volume, Chapter 13).

12 Some themes of the pluralist model have been suggested to me by the work of Yrjo

Sepanmaa, especially his The Beauty of Environment, Second Edition, Denton,

Texas, Environmental Ethics Books, 1993. I endorse certain aspects of this model in

“Landscape and Literature” (in this volume, Chapter 14).

13 The metaphysical imagination model is outlined in Ronald W.Hepburn, “Landscape

and the Metaphysical Imagination,” Environmental Values, 1996, vol. 5, pp. 191–204.

14 Since, as noted, Hepburn’s “Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect of Natural

Beauty,” op. cit., set the initial agenda for the contemporary discussion of the

aesthetics of nature and since the metaphysical imagination model is one of his most

recent contributions to the field, it is most fitting that this model should set a new

agenda for future discussion.

15 Perhaps a paradigm exemplification of aesthetic appreciation enhanced by natural

science is Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, Oxford, Oxford University Press,

1949. Leopold’s aesthetics are elaborated in “The Land Aesthetic,” in J.B.Callicott

(ed.) Companion to A Sand County Almanac, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press,

1987, pp. 157–71. The centrality of science in aesthetic appreciation of nature is

challenged in Y.Saito, “Is There a Correct Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature?,” Journal

of Aesthetic Education, 1984, vol. 18, pp. 35–46. I discuss her concerns in “Saito on

14 AESTHETICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

the Correct Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature,” Journal of Aesthetic Education, 1986,

vol. 20, pp. 85–93. For further discussion of the role of science, see H.Rolston, “Does

Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature Need to be Science Based?,” British Journal of

Aesthetics, 1995, vol. 35, pp. 374–86 and M.Budd, “The Aesthetic Appreciation of

Nature,” British Journal of Aesthetics, 1996, vol. 36, pp. 207–22, as well as Y. Saito,

“The Aesthetics of Unscenic Nature,” S.Godlovitch, “Evaluating Nature

Aesthetically,” C.Foster, “The Narrative and the Ambient in Environmental

Aesthetics,” E.Brady, “Imagination and the Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature,” M.

M.Eaton, “Fact and Fiction in the Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature,” and H.Rolston,

“Aesthetic Experience in Forests,” all in A.Berleant and A.Carlson (eds) The Journal of

Aesthetics and Art Criticism: Special Issue: Environmental Aesthetics, 1998, vol. 56, pp.

101–66.

16 I consider positive aesthetics and its relationship to the rise of science in “Nature and

Positive Aesthetics,” op. cit, (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 6).

17 I discuss objectivity in appreciation of nature in “Nature, Aesthetic Judgment, and

Objectivity,” op. cit. (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 5) and in “On the

Possibility of Quantifying Scenic Beauty,” Landscape Planning, 1977, vol. 4, pp. 131–

72. I briefly overview some of the issues in landscape assessment research in

“Landscape Assessment,” in M.Kelly (ed.) Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, New York,

Oxford University Press, 1989, Vol. 3, pp. 102–5.

18 I apply these ideas to other kinds of cases in Part II of this volume, especially in “On

the Aesthetic Appreciation of Japanese Gardens,” British Journal of Aesthetics, 1997,

vol. 37, pp. 47–56 (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 11), “On Appreciating

Agricultural Landscapes,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1985, vol. 43, pp.

301–12 (reproduced in this volume, Chapter 12), and “Existence, Location, and

Function: The Appreciation of Architecture,” in Mitias, op. cit. (reproduced in this

volume, Chapter 13).

19 I develop the idea of an object-centered aesthetics in “Appreciating Art and

Appreciating Nature,” in Kemal and Gaskell, op. cit., pp. 199–227 (reproduced in

this volume, Chapter 7) and throughout Part II of this volume, especially in “Between

Nature and Art” (this volume, Chapter 8).

THE AESTHETICS OF NATURE 15

16

2

UNDERSTANDING AND AESTHETIC

EXPERIENCE

Aesthetic experience on the Mississippi

In Life on the Mississippi Mark Twain remarks:

The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book—a book

that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told

its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as

clearly as if it uttered them with a voice… In truth, the passenger who

could not read this book saw nothing but all manner of pretty pictures

in it, painted by the sun and shaded by the clouds, whereas to the

trained eye these were not pictures at all, but the grimmest and most

dead-earnest of reading matter.

Now when I had mastered the language of this water… I had made a

valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. I had lost

something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the

grace, the beauty, the poetry had gone out of the majestic river! I still

kept in mind a certain wonderful sunset which I witnessed when

steamboating was new to me. A broad expanse of the river was turned

to blood; in the middle distance the red hue brightened into gold,

through which a solitary log came floating, black and conspicuous; in

one place a long, slanting mark lay sparkling upon the water; in another

the surface was broken by boiling, tumbling rings, that were as many-

tinted as an opal; where the ruddy flush was faintest, was a smooth spot

that was covered with graceful circles and radiating lines, ever so

delicately traced; the shore on our left was densely wooded, and the

somber shadow that fell from this forest was broken in one place by a

long, ruffled trail that shone like silver; and high above the forest wall a

clean-stemmed dead tree waved a single leafy bough that glowed like a

flame in the unobstructed splendor that was flowing from the sun.

There were graceful curves, reflected images, woody heights, soft

distances; and over the whole scene, far and near, the dissolving lights

drifted steadily, enriching it, every passing moment, with new marvels

of coloring.

I stood like one bewitched. I drank it in, in a speechless rapture…

But as I have said, a day came when…if that sunset scene had been

repeated, I should have looked upon it without rapture, and should

have commented upon it, inwardly, after this fashion: The sun means

that we are going to have wind to-morrow; the floating log means that

the river is rising, small thanks to it; that slanting mark on the water

refers to a bluff reef which is going to kill somebody’s steamboat one of

these nights, if it keeps on stretching out like that; those tumbling

“boils” show a dissolving bar and a changing channel there; the lines

and circles in the slick water over yonder are a warning that that

troublesome place is shoaling up dangerously; that silver streak in the

shadow of the forest is the “break” from a new snag, and he has located

himself in the very best place he could have found to fish for

steamboats; that tall dead tree, with a single living branch, is not going

to last long, and then how is a body ever going to get through this blind

place at night without the friendly old landmark?

No, the romance and the beauty were all gone from the river.

1

In this passage, Twain describes two different experiences of the river. The first,

when steamboating was new to him and he saw the river as would an “uneducated

passenger,” is an experience of “all manner of pretty pictures, painted by the sun and

shaded by the clouds.” The second, when he had “mastered the language of this

water” and he looked upon the river with a “trained eye,” is an experience in which

the pretty pictures are replaced by an understanding of the meaning of the river. Twain

suggests that the two experiences are mutually exclusive, or at least that each makes

the other difficult, if not impossible. On the one hand, the uneducated passenger

sees “nothing but” pretty pictures because he or she cannot read the language of the

river. On the other, Twain, once he had learned to understand this language, had

“lost something which could never be restored”—“All the grace, the beauty, the

poetry had gone out of the majestic river!”

The first experience Twain describes, that of the grace, the beauty, and the poetry of

the river, is of the kind that is typically called aesthetic experience. The second is of

the kind that may be characterized as cognitive; it involves an understanding of

meanings achieved in virtue of knowledge gained through education or training.

Thus, a significant question posed by Twain’s remarks is the question of whether or

not aesthetic experience and cognitive experience are in conflict in the way in which

he seemingly suggests that they are. Is it the case that, without knowledge and

understanding of that which we experience, we, like the uneducated passenger, may

experience it aesthetically? And, more important, is it the case that once we have

acquired such knowledge and understanding the possibility of aesthetic experience is

in some way destroyed—and that we, like Twain, have then “lost something which

could never be restored”?

18 UNDERSTANDING AND AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE

To address these issues, we need to examine more carefully Twain’s conception of

the nature of aesthetic experience. Twain says that without knowing the language of

the river, the uneducated passenger sees nothing but pretty pictures. However, his

account of his own aesthetic experience of the river before he had acquired this

knowledge of the river’s language reveals an experience more cultivated than simply

seeing pretty pictures. It is an experience of overpowering beauty which “bewitches”

him, reducing him to a “speechless rapture.” Moreover, his description of the scene

that evokes this rapture is primarily in terms of two kinds of things. First, he describes

“marvels of coloring” such as “the river…turned to blood,…the red hue brightened

into gold,” “rings…as many-tinted as an opal,” a “trail that shone like silver,” and a

“bough that glowed like a flame in the unobstructed splendor that was flowing from

the sun.” Second, he describes what may be called marvels of form, such as “a long,

slanting mark…sparkling upon the water,” “the surface broken by boiling, tumbling

rings,” and “a smooth spot…covered with graceful circles and radiating lines, ever so

delicately traced.” In short, Twain’s conception of aesthetic experience is that of an