2

nd

Edition

Teacher’s

MANUAL

Dimensions of Learning

Robert J. Marzano

and

Debra J. Pickering

with

Daisy E. Ar redondo

Guy J. Blackburn

Ronald S. Brandt

Cerylle A. Moffett

Diane E. Paynter

Jane E. Pollock

Jo Sue Whisler

Dimensions of Learning

Robert J. Marzano

and

Debra J. Pickering

with

Daisy E. Arredondo

Guy J. Blackburn

Ronald S. Brandt

Cerylle A. Moffett

Diane E. Paynter

Jane E. Pollock

Jo Sue Whisler

2

nd

Edition

Teacher’s

MANUAL

Alexandria, Virginia USA

Mid-continent Regional Educational Laboratory

Aurora, Colorado USA

DoL Teacher TP/Div 1/1/04 2:11 AM Page 1

Copyright © 1997 McREL (Mid-continent Regional Educational Laboratory), 2550 S.

Parker Road, Suite 500, Aurora, Colorado 80014, (303) 337-0990, fax (303) 337-3005. All

rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from McREL.

1703 N. Beauregard St. • Alexandria, VA 22311-1714 USA

Telephone: 1-800-933-2723 or 703-578-9600 • Fax: 703-575-5400

Web site: http://www.ascd.org • E-mail: member@ascd.org

Author guidelines: www.ascd.org/write

Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning

4601 DTC Boulevard

Suite 500

Denver, Colorado 80237

Phone: 303-337-0990

Fax: 303-337-3005

Barbara B. Gaddy, Editor/Project Manager

Jeanne Deak, Desktop Publisher

Sarah Allen Smith, Indexer

Printed in the United States of America.

ASCD publications present a variety of viewpoints. The views expressed or implied

in this book should not be interpreted as official positions of the Association.

ISBN: 978-1-4166-0897-4

ASCD stock no. 109115 S6/97

To order additional copies of this book, please contact ASCD: 1-800-933-2723 or

703-578-9600.

12 11 10 09 08 6 5 4

copyright/authors(final):copyright/authors(final) 4/11/11 10:05 AM Page 1

Dimensions of Learning

Teacher’s Manual

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi

Introduction

Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

What Is Dimensions of Learning? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Chapter 1. Dimension 1: Attitudes and Perceptions

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Helping Students Develop Positive Attitudes and Perceptions

About Classroom Climate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Feel Accepted by Teachers and Peers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Experience a Sense of Comfort and Order . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Classroom Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Helping Students Develop Positive Attitudes and Perceptions

About Classroom Tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Perceive Tasks as Valuable and Interesting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Believe They Have the Ability and Resources to Complete Tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Understand and Be Clear About Tasks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Classroom Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Unit Planning: Dimension 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Chapter 2. Dimension 2: Acquire and Integrate Knowledge

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

The Importance of Understanding the Nature of Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

The Relationship Between Declarative and Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Levels of Generality and the Organization of Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Acquiring and Integrating Declarative and Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

table of contents 4/17/09 12:11 PM Page i

Helping Students Acquire and Integrate Declarative Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Construct Meaning for Declarative Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Organize Declarative Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Store Declarative Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Classroom Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Unit Planning: Dimension 2, Declarative Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Helping Students Acquire and Integrate Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Construct Models for Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Shape Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Internalize Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Classroom Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

Unit Planning: Dimension 2, Procedural Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

Chapter 3. Dimension 3: Extend and Refine Knowledge

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

Helping Students Develop Complex Reasoning Processes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

Comparing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

Classifying . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

Abstracting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

Inductive Reasoning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

Deductive Reasoning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146

Constructing Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

Analyzing Errors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 168

Analyzing Perspectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178

Unit Planning: Dimension 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

Chapter 4. Dimension 4: Use Knowledge Meaningfully

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

Helping Students Develop Complex Reasoning Processes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191

Decision Making . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 195

Problem Solving . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205

Invention . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214

Experimental Inquiry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 224

Investigation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234

Systems Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246

Unit Planning: Dimension 4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

table of contents 4/17/09 12:11 PM Page ii

Chapter 5. Dimension 5: Habits of Mind

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

Helping Students Develop Productive Habits of Mind. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 264

Classroom Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270

The Dimensions of Learning Habits of Mind:

A Resource for Teachers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 274

Critical Thinking

Be Accurate and Seek Accuracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 274

Be Clear and Seek Clarity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 276

Maintain an Open Mind . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277

Restrain Impulsivity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279

Take a Position When the Situation Warrants It . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281

Respond Appropriately to Others’ Feelings and Level of Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . 282

Creative Thinking

Persevere . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

Push the Limits of Your Knowledge and Abilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285

Generate, Trust, and Maintain Your Own Standards of Evaluation . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

Generate New Ways of Viewing a Situation

That Are Outside the Boundaries of Standard Conventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

Self-Regulated Thinking

Monitor Your Own Thinking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 290

Plan Appropriately . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291

Identify and Use Necessary Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 293

Respond Appropriately to Feedback . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295

Evaluate the Effectiveness of Your Actions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 296

Unit Planning: Dimension 5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 298

Chapter 6. Putting It All Together

Content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 303

Assessment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309

Grading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317

Sequencing Instruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 322

Conferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 327

In Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 328

Colorado Unit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 329

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 341

Index. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 347

table of contents 4/17/09 12:11 PM Page iii

vi

Teacher’s Manual

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to those individuals from the following school

districts who contributed ideas and suggestions to this second edition of the Dimensions of Learning

Teacher’s Manual:

Ashwaubenon School District, Green Bay, Wisconsin

Berryessa Union School District, San Jose, California

Brisbane Grammar School, Queensland, Australia

Brockport Central School District, Brockport, New York

Brooklyn School District, Brooklyn, Ohio

Broome-Tioga Boces, Binghamton, New York

Cherry Creek Public Schools, Aurora, Colorado

Colegio International de Caracas, Caracas, Venezuela

Douglas County Schools, Douglas County, Colorado

George School District, George, Iowa

Green Bay Area Public Schools, Green Bay, Wisconsin

Ingham Intermediate School District, Mason, Michigan

Kenosha Unified School District #1, Kenosha, Wisconsin

Kingsport City Schools, Kingsport, Tennessee

Lakeland Area Education Agency #3, Cylinder, Iowa

Lakeview Public Schools, St. Clair Shores, Michigan

Loess Hills AEA #13, Council Bluffs, Iowa

Lonoke School District, Lonoke, Arkansas

Love Elementary School, Houston, Texas

Maccray School, Clara City, Minnesota

Monroe County ISD, Monroe, Michigan

Nicolet Area Consortium, Glendale, Wisconsin

Northern Trails AEA #2, Clear Lake, Iowa

North Syracuse Central School District, North Syracuse, New York

Prince Alfred College, Kent Town, South Australia

Redwood Elementary School, Avon Lake, Ohio

Regional School District #13, Durham, Connecticut

Richland School District, Richland, Washington

St. Charles Parish Public Schools, Luling, Louisiana

School District of Howard-Suamico, Green Bay, Wisconsin

South Washington County Schools, Cottage Grove, Minnesota

Webster City Schools, Webster City, Iowa

West Morris Regional High School District, Chester, New Jersey

table of contents revised:table of contents revised 4/11/11 11:18 AM Page vi

vii

Teacher’s Manual

The following members of the Dimensions of Learning Research and Development Consortium worked

together from 1989 to 1991 to advise, consult, and pilot portions of the model as part of the

development of Dimensions of Learning.

ALABAMA

Auburn University

Terrance Rucinski

CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles County Office of Education

Richard Sholseth

Diane Watanabe

Napa Valley Unified School District

Mary Ellen Boyet

Laurie Rucker

Daniel Wolter

COLORADO

Aurora Public Schools

Kent Epperson

Phyllis A. Henning

Lois Kellenbenz

Lindy Lindner

Rita Perron

Janie Pollock

Nora Redding

Cherry Creek Public Schools

Maria Foseid

Patricia Lozier

Nancy MacIsaacs

Mark Rietema

Deena Tarleton

ILLINOIS

Maine Township High School West

Betty Duffey

Mary Gienko

Betty Heraty

Paul Leathem

Mary Kay Walsh

IOWA

Dike Community Schools

Janice Albrecht

Roberta Bodensteiner

Ken Cutts

Jean Richardson

Stan Van Hauen

Mason City Community Schools

Dudley L. Humphrey

MASSACHUSETTS

Concord-Carlisle Regional School District

Denis Cleary

Diana MacLean

Concord Public Schools

Virginia Barker

Laura Cooper

Stephen Greene

Joe Leone

Susan Whitten

MICHIGAN

Farmington Public Schools

Marilyn Carlsen

Katherine Nyberg

James Shaw

Joyce Tomlinson

Lakeview Public Schools

Joette Kunse

Oakland Schools

Roxanne Reschke

Waterford School District

Linda Blust

Julie Casteel

Bill Gesaman

Mary Lynn Kraft

Al Monetta

Theodora M. Sailer

Dick Williams

table of contents revised:table of contents revised 4/11/11 11:18 AM Page vii

viii

Teacher’s Manual

NEBRASKA

Fremont Public Schools, District 001

Mike Aerni

Trudy Jo Kluver

Fred Robertson

NEW MEXICO

Gallup-McKinley County Schools

Clara Esparza

Ethyl Fox

Martyn Stowe

Linda Valentine

Chantal Irvin

NEW YORK

Frontier Central Schools

Janet Brooks

Barbara Broomell

PENNSYLVANIA

Central Bucks School District

Jeanann Kahley

N. Robert Laws

Holly Lomas

Rosemarie Montgomery

Cheryl Winn Royer

Jim Williams

Philadelphia School District

Paul Adorno

Shelly Berman

Ronald Jenkins

John Krause

Judy Lechner

Betty Richardson

SOUTH CAROLINA

School District of Greenville County

Sharon Benston

Dale Dicks

Keith Russell

Jane Satterfield

Ellen Weinberg

Mildred Young

State Department of Education

Susan Smith White

TEXAS

Fort Worth Independent School District

Carolyne Creel

Sherry Harris

Midge Rach

Nancy Timmons

UTAH

Salt Lake City Schools

Corrine Hill

MEXICO

ITESO University

Ana Christina Amante

Laura Figueroa Barba

Antonio Ray Bazan

Luis Felipe Gomez

Patricia Rios de Lopez

PROGRAM EVALUATOR

Charles Fisher

table of contents revised:table of contents revised 4/11/11 11:18 AM Page viii

1

Teacher’s Manual

1

Introduction

Overview

Dimensions of Learning is an extension of the comprehensive research-based

framework on cognition and learning described in Dimensions of Thinking: A

Framework for Curriculum and Instruction (Marzano et al., 1988), published by

the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Dimensions of Learning translates the research and theory explained in

Dimensions of Thinking into a practical framework that K-12 teachers can use

to improve the quality of teaching and learning in any content area. The

Dimensions of Learning Research and Development Consortium, which

worked on the model for two years, was made up of more than ninety

educators, including the author team from the first edition of this manual.

Under the leadership of Dr. Robert Marzano of the Mid-continent Regional

Educational Laboratory (McREL), these educators helped to shape the basic

program into a valuable tool for reorganizing curriculum, instruction, and

assessment.

Implicit in the Dimensions of Learning model, or framework, are five basic

assumptions:

1. Instruction must reflect the best of what we know about how learning

occurs.

2. Learning involves a complex system of interactive processes that includes

five types of thinking—represented by the five dimensions of learning.

3. The K-12 curriculum should include the explicit teaching of attitudes,

perceptions, and mental habits that facilitate learning.

4. A comprehensive approach to instruction includes at least two distinct

types of instruction: one that is more teacher directed, and another that

is more student directed.

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 1

2

Teacher’s Manual

Overview

Introduction

5. Assessment should focus on students’ use of knowledge and complex

reasoning processes rather than on their recall of information.

In addition to this teacher’s manual, Dimensions of Learning is supported by

a number of resources designed to help educators fully understand (1) how

these five assumptions affect teachers’ work in the classroom and, as a

consequence, students’ learning and (2) how the Dimensions of Learning

framework can be used to restructure curriculum, instruction, and

assessment:

• A Different Kind of Classroom: Teaching with Dimensions of Learning

(Marzano, 1992) explores the theory and research underlying the

framework through a variety of classroom-based examples. Although

teachers need not read this book to use the model, they will have a

better understanding of cognition and learning if they do. Staff

developers also are encouraged to read this book to strengthen their

delivery of the Dimensions of Learning training.

• Observing Dimensions of Learning in Classrooms and Schools (Brown,

1995) is designed to help administrators provide support and

feedback to teachers who are using Dimensions of Learning in their

classrooms.

• Dimensions of Thinking (Marzano et al., 1988) describes a framework

that can be used to design curriculum and instruction with an

emphasis on the types of thinking that students should use to

enhance their learning.

• The Dimensions of Learning Trainer’s Manual (Marzano et al., 1997)

contains detailed training scripts, overhead transparencies, and

practical guidelines for conducting comprehensive training and staff

development in the Dimensions of Learning program.

• Assessing Student Outcomes: Performance Assessment Using the Dimensions of

Learning Model (Marzano, Pickering, & McTighe, 1993) provides

recommendations for setting up an assessment system that focuses on

using performance tasks constructed with the reasoning processes

from Dimensions 3 and 4.

We recommend that those who plan to train others to use Dimensions of

Learning first participate in the training offered by ASCD or McREL or by

individuals recommended by these organizations. In some cases, experienced

staff development trainers with an extensive background in the teaching of

thinking may be able to learn about each dimension through self-study or,

ideally, through study with peers. We strongly recommend, however, that

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 2

3

Teacher’s Manual

Overview

Introduction

before conducting training for others, these individuals use the Dimensions

of Learning framework to plan and teach units of instruction themselves. In

short, Dimensions of Learning is best understood and internalized through

practical experience with the model.

• Implementing Dimensions of Learning (Marzano et al., 1992) explains

the different ways that the model can be used in a school or district

and discusses the various factors that must be considered when

deciding which approach to use. It contains guidelines that will help

a school or district structure its implementation to best achieve its

identified goals.

• Finally, the Dimensions of Learning Videotape Series (ASCD, 1992)

introduces and illustrates some of the important concepts underlying

the Dimensions of Learning framework. Videotaped classroom

examples of each dimension in action can be used during training, in

follow-up sessions for reinforcement, or during Dimensions of

Learning study-group sessions.

Together, these resources guide educators through a structured, yet flexible,

approach to improving curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 3

4

Teacher’s Manual

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

What Is Dimensions of Learning?

Dimensions of Learning is a comprehensive model that uses what researchers

and theorists know about learning to define the learning process. Its premise

is that five types of thinking—what we call the five dimensions of

learning—are essential to successful learning. The Dimensions framework

will help you to

• maintain a focus on learning;

• study the learning process; and

• plan curriculum, instruction, and assessment that takes into account

the five critical aspects of learning.

Now let’s take a look at the five dimensions of learning.

Dimension 1: Attitudes and Perceptions

Attitudes and perceptions affect students’ abilities to learn. For example, if

students view the classroom as an unsafe and disorderly place, they will

likely learn little there. Similarly, if students have negative attitudes about

classroom tasks, they will probably put little effort into those tasks. A key

element of effective instruction, then, is helping students to establish

positive attitudes and perceptions about the classroom and about learning.

Dimension 2: Acquire and Integrate Knowledge

Helping students acquire and integrate new knowledge is another important

aspect of learning. When students are learning new information, they must

be guided in relating the new knowledge to what they already know,

organizing that information, and then making it part of their long-term

memory. When students are acquiring new skills and processes, they must

learn a model (or set of steps), then shape the skill or process to make it

efficient and effective for them, and, finally, internalize or practice the skill

or process so they can perform it easily.

Dimension 3: Extend and Refine Knowledge

Learning does not stop with acquiring and integrating knowledge. Learners

develop in-depth understanding through the process of extending and

refining their knowledge (e.g., by making new distinctions, clearing up

misconceptions, and reaching conclusions). They rigorously analyze what

they have learned by applying reasoning processes that will help them

“Oh how fine it is to know

a thing or two.”

—Molière

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 4

5

Teacher’s Manual

extend and refine the information. Some of the common reasoning processes

used by learners to extend and refine their knowledge are the following:

• Comparing

• Classifying

• Abstracting

• Inductive reasoning

• Deductive reasoning

• Constructing support

• Analyzing errors

• Analyzing perspectives

Dimension 4: Use Knowledge Meaningfully

The most effective learning occurs when we use knowledge to perform

meaningful tasks. For example, we might initially learn about tennis rackets

by talking to a friend or reading a magazine article about them. We really

learn about them, however, when we are trying to decide what kind of tennis

racket to buy. Making sure that students have the opportunity to use

knowledge meaningfully is one of the most important parts of planning a

unit of instruction. In the Dimensions of Learning model, there are six

reasoning processes around which tasks can be constructed to encourage the

meaningful use of knowledge:

• Decision making

• Problem solving

• Invention

• Experimental inquiry

• Investigation

• Systems analysis

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

“Knowledge changes

knowledge.”

“Information isn’t

knowledge until you can use

it.”

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 5

6

Teacher’s Manual

Dimension 5: Habits of Mind

The most effective learners have developed powerful habits of mind that

enable them to think critically, think creatively, and regulate their behavior.

These mental habits are listed below:

Critical thinking:

• Be accurate and seek accuracy

• Be clear and seek clarity

• Maintain an open mind

• Restrain impulsivity

• Take a position when the situation warrants it

• Respond appropriately to others’ feelings and level of knowledge

Creative thinking:

• Persevere

• Push the limits of your knowledge and abilities

• Generate, trust, and maintain your own standards of evaluation

• Generate new ways of viewing a situation that are outside the

boundaries of standard conventions

Self-regulated thinking:

• Monitor your own thinking

• Plan appropriately

• Identify and use necessary resources

• Respond appropriately to feedback

• Evaluate the effectiveness of your actions

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 6

7

Teacher’s Manual

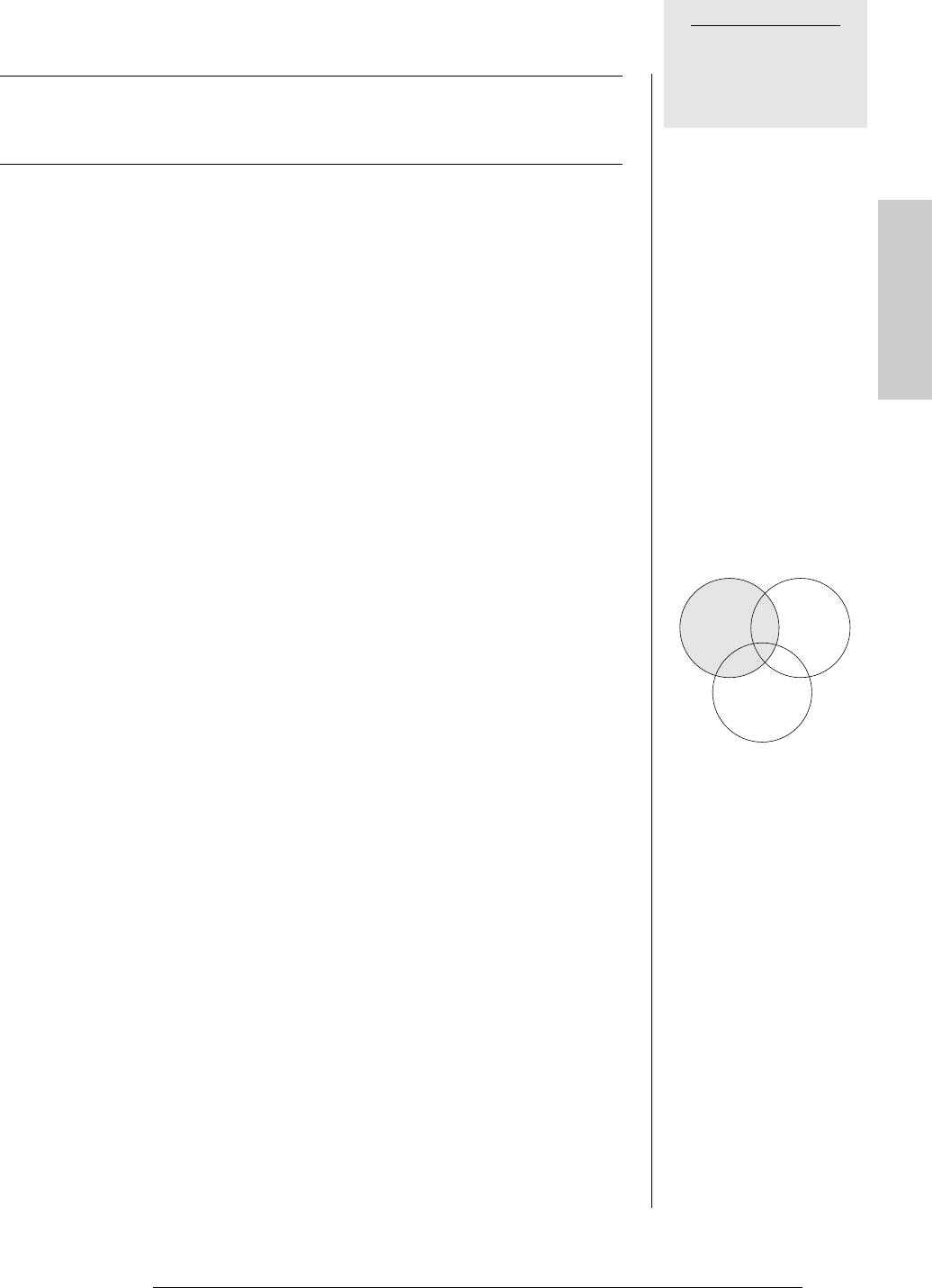

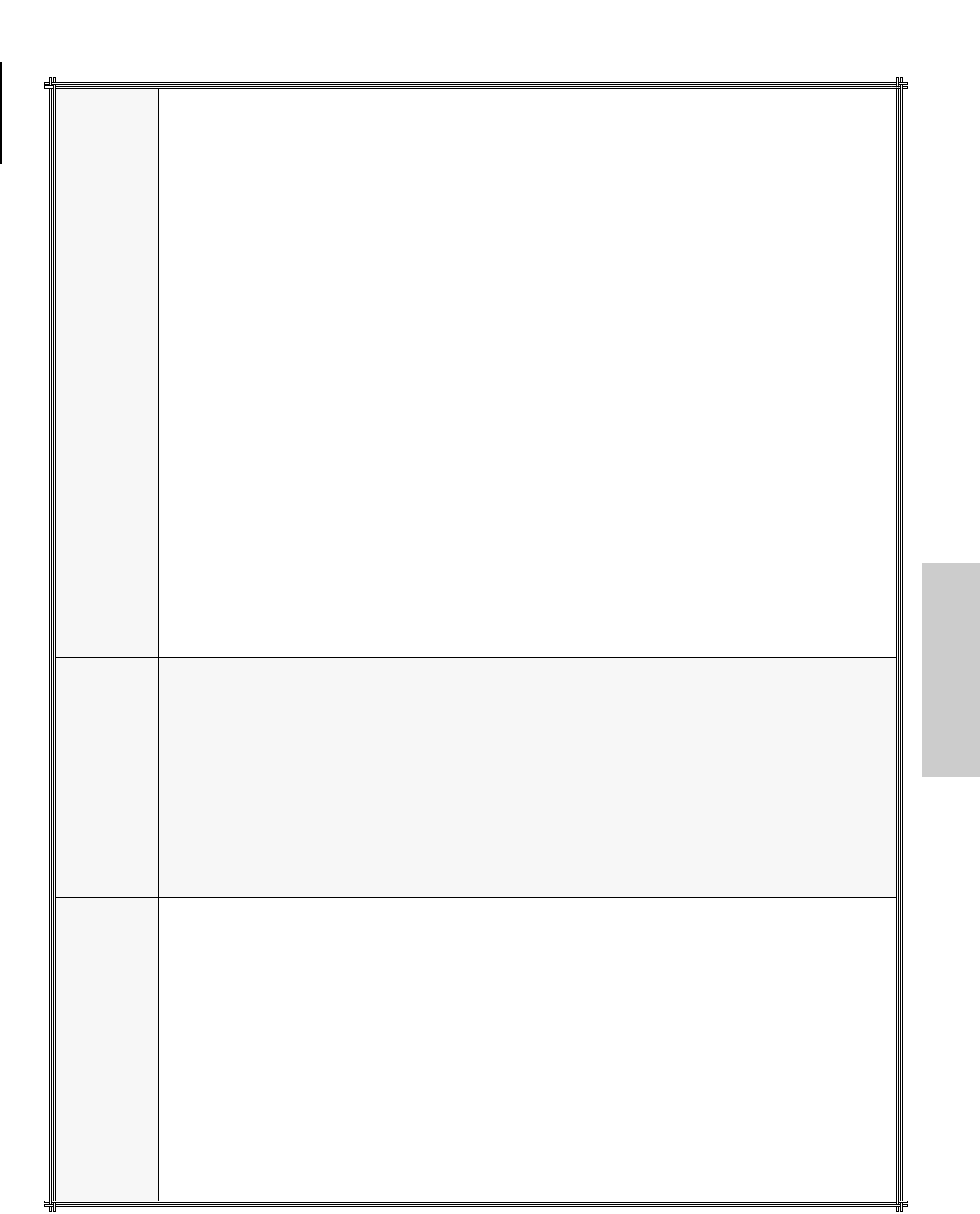

The Relationship Among the Dimensions of Learning

It is important to realize that the five dimensions of learning do not operate

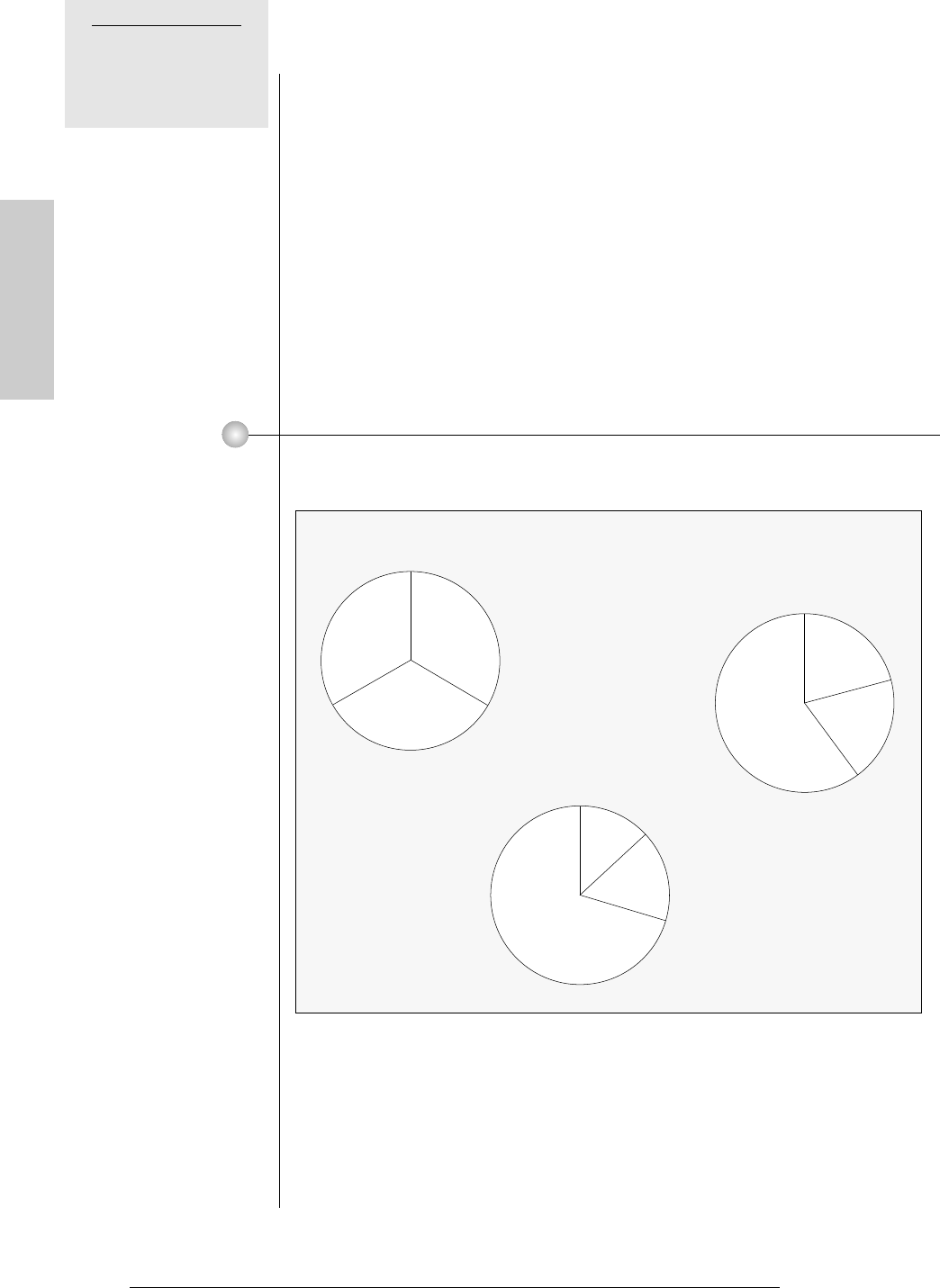

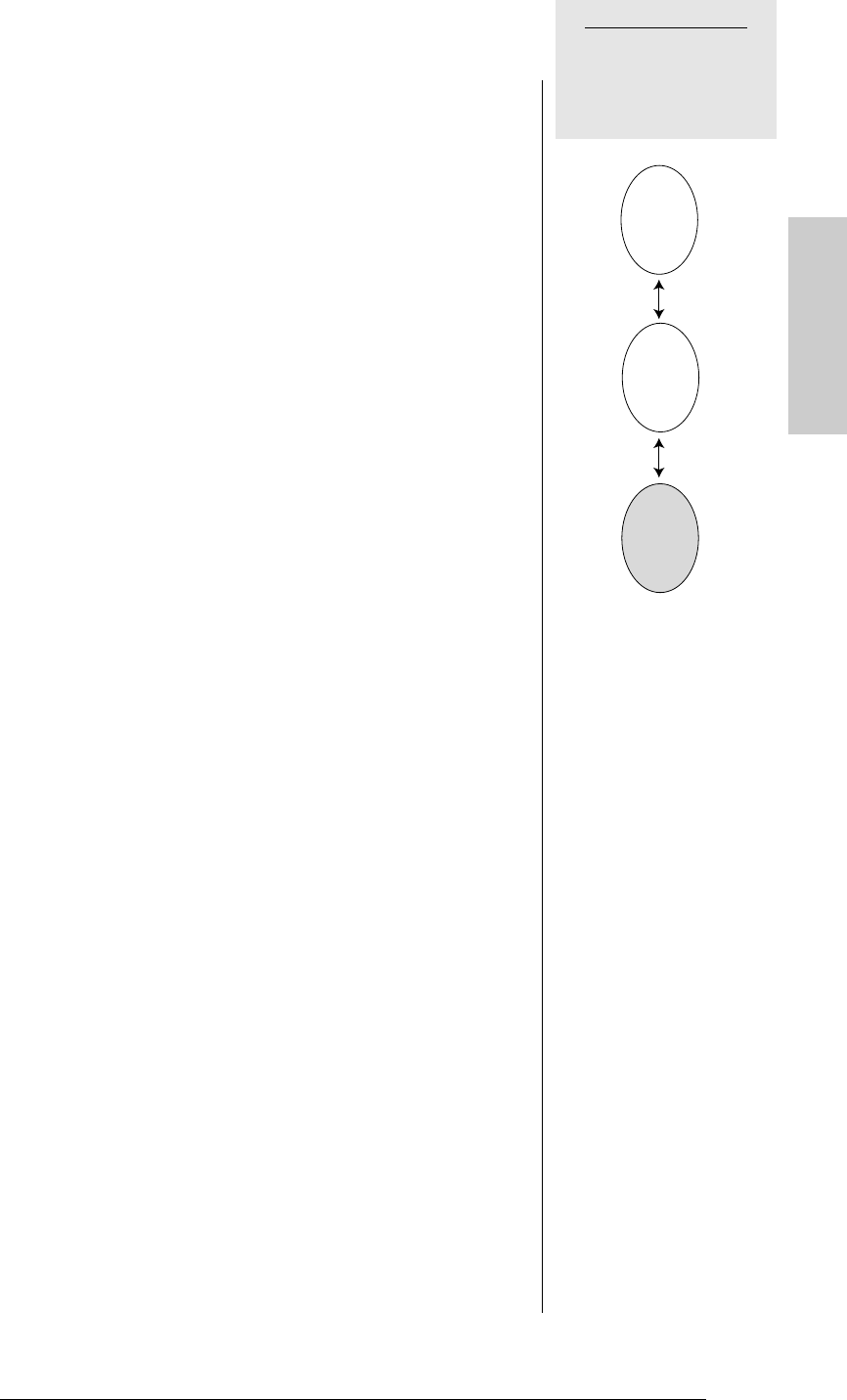

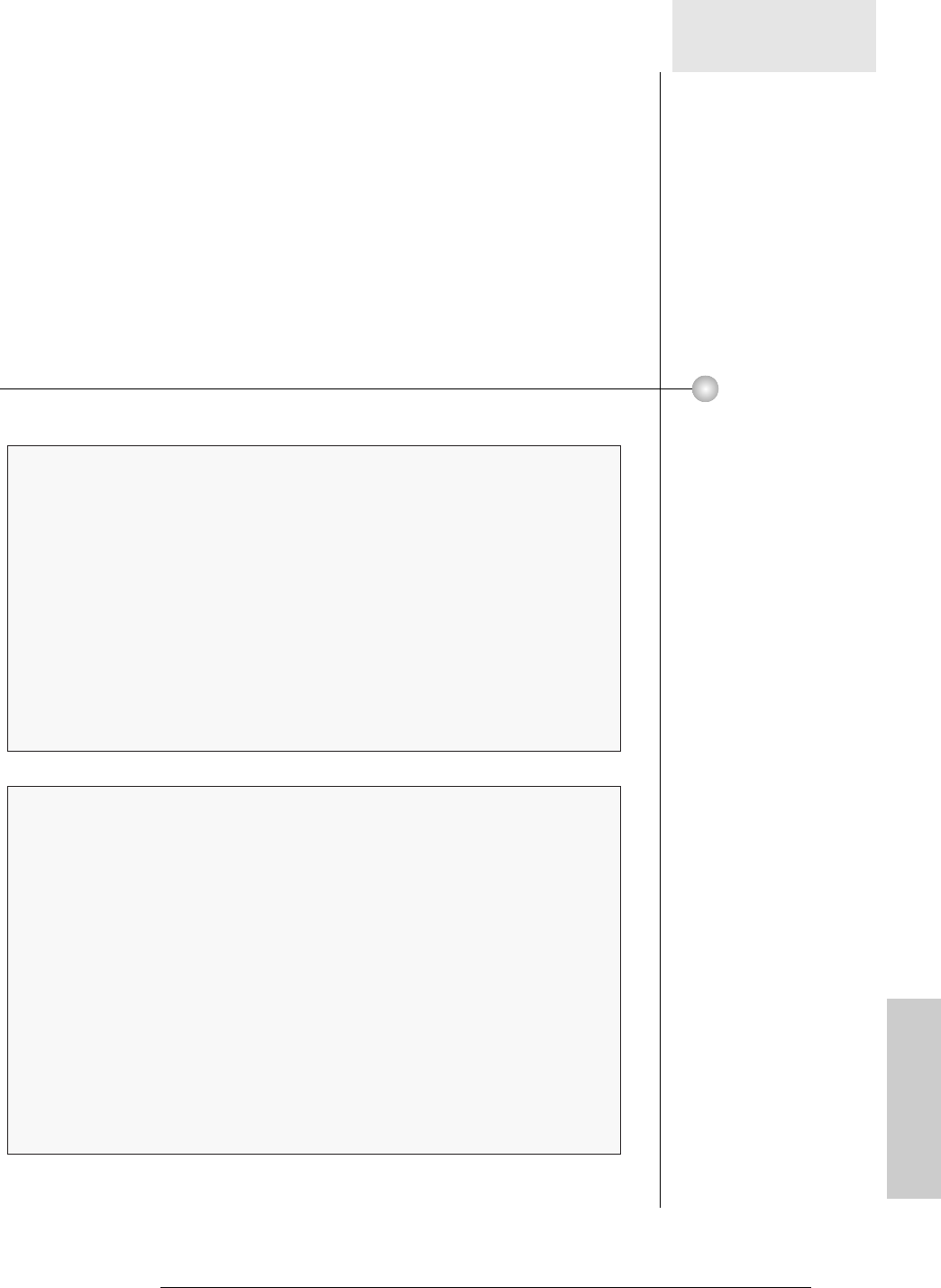

in isolation but work together in the manner depicted in Figure A.1.

FIGURE A.1

H

OW THE DIMENSIONS OF LEARNING INTERACT

Briefly, as the graphic in Figure A.1 illustrates, all learning takes place

against the backdrop of learners’ attitudes and perceptions (Dimension 1)

and their use (or lack of use) of productive habits of mind (Dimension 5). If

students have negative attitudes and perceptions about learning, then they

will likely learn little. If they have positive attitudes and perceptions, they

will learn more and learning will be easier. Similarly, when students use

productive habits of mind these habits facilitate their learning. Dimensions

1 and 5, then, are always factors in the learning process. This is why they are

part of the background of the graphic shown in Figure A.1.

When positive attitudes and perceptions are in place and productive habits

of mind are being used, learners can more effectively do the thinking

required in the other three dimensions, that is, acquiring and integrating

H

a

b

i

t

s

o

f

M

i

n

d

A

t

t

i

t

u

d

e

s

a

n

d

P

e

r

c

e

p

t

i

o

n

s

Using Knowledge

Meaningfully

Extending and

Refining Knowledge

Acquiring

and Integrating

Knowledge

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 7

8

Teacher’s Manual

knowledge (Dimension 2), extending and refining knowledge (Dimension

3), and using knowledge meaningfully (Dimension 4). Notice the relative

positions of the three circles of Dimensions 2, 3, and 4. (See Figure A.1.)

The circle representing meaningful use of knowledge subsumes the other

two, and the circle representing extending and refining knowledge subsumes

the circle representing acquiring and integrating knowledge. This

communicates that when learners extend and refine knowledge, they

continue to acquire knowledge, and when they use knowledge meaningfully,

they are still acquiring and extending knowledge. In other words, the

relationships among these circles represent types of thinking that are neither

discrete nor sequential. They represent types of thinking that interact and

that, in fact, may be occurring simultaneously during learning.

It might be useful to consider the Dimensions of Learning model as

providing a metaphor for the learning process. Dimensions of Learning offers

a way of thinking about the extremely complex process of learning so that we

can attend to each aspect and gain insights into how they interact. If it serves

this purpose, it will be a useful tool as we attempt to help students learn.

Uses of Dimensions of Learning

As a comprehensive model of learning, Dimensions can have an impact on

virtually every aspect of education. Because the major goal of education is to

enhance learning, it follows that our system of education must focus on a

model that represents criteria for effective learning, criteria that we must use

to make decisions and evaluate programs. Although Dimensions is certainly

not the only model of learning, it is a powerful tool for ensuring that

learning is the focus of what we do as educators. It should validate current

efforts in schools and classrooms to enhance learning, but should also suggest

ways of continuing to improve. Although individuals, schools, and districts

should use the model to meet their own needs, it might be helpful to

understand a number of possible ways in which the Dimensions of Learning

model might be used.

A Resource for Instructional Strategies

At the most basic level, this manual has been used as a resource for research-

based instructional strategies. Although there are many effective strategies

included in the manual, it is important to remember that the manual is not

the model. As the strategies are used, they should be selected and their

effectiveness measured in terms of the desired effect on learning. The

implication is that even at this basic level of use, it is important for teachers

to understand each dimension as they select and use strategies.

“We were thrilled to discover

that Dimensions of Learning

is not an ‘add-on’ but,

instead, a framework that

enhances teaching and

learning across the curricula

within our classrooms.”

—First-grade teacher

in Connecticut

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 8

9

Teacher’s Manual

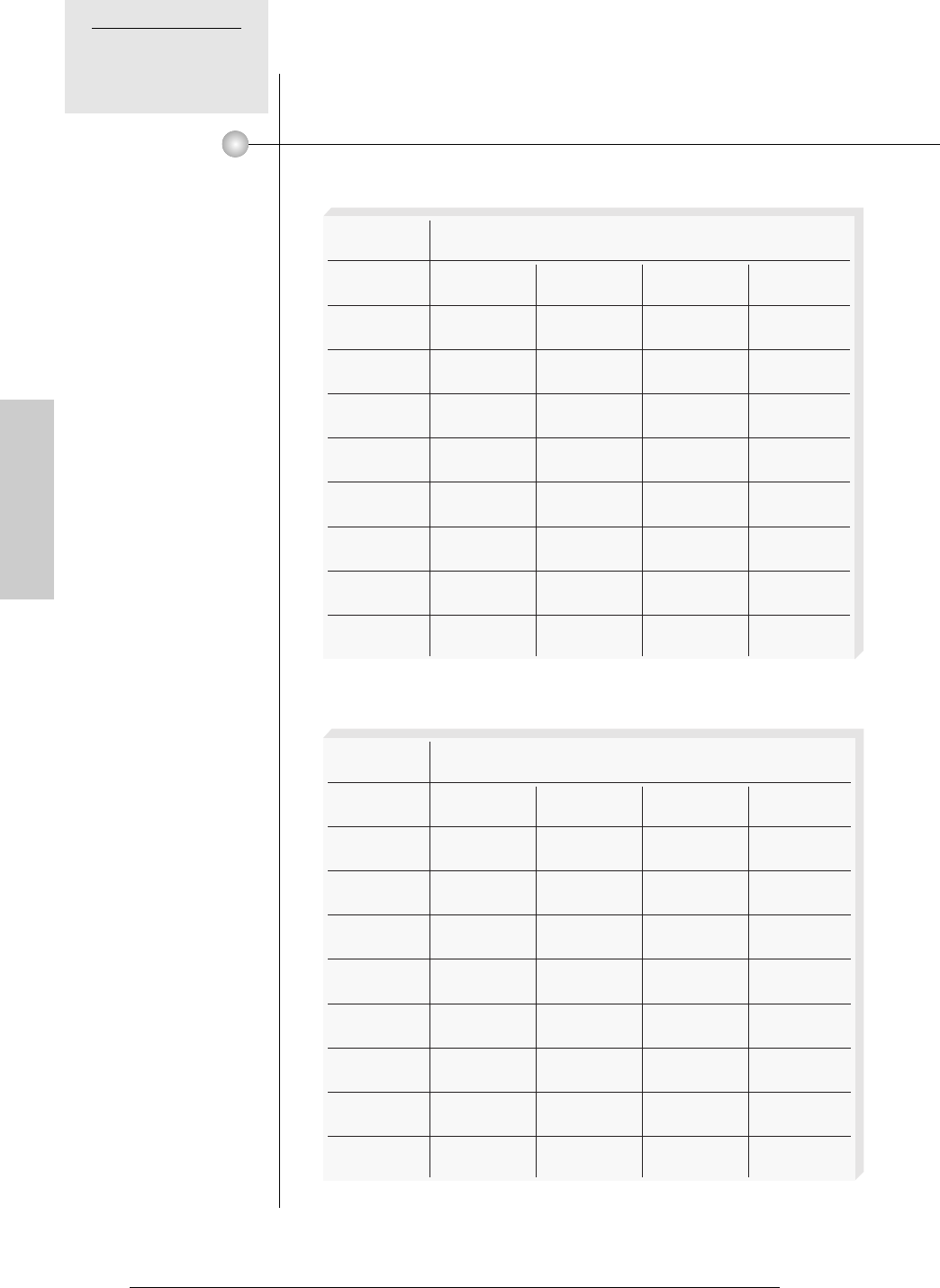

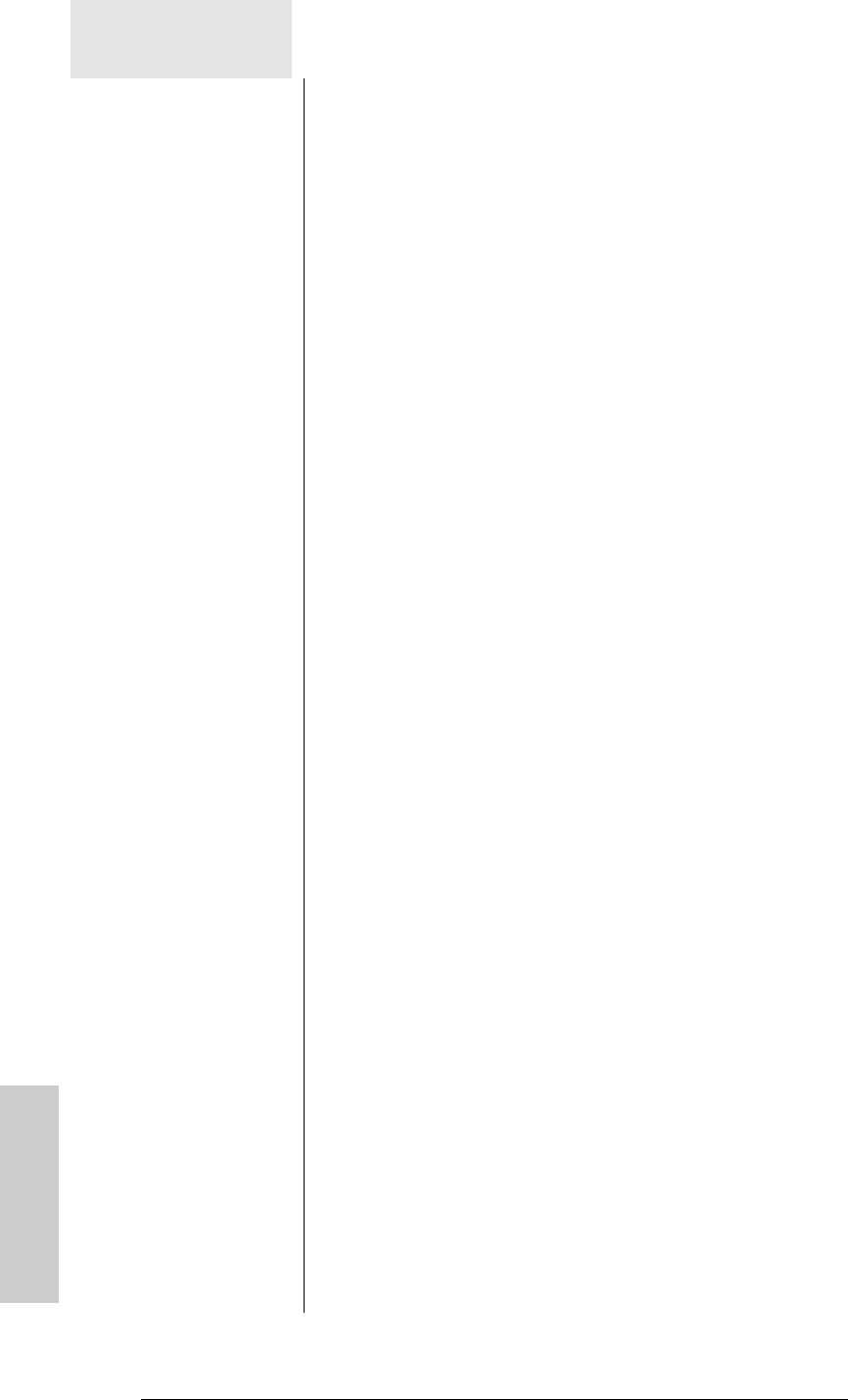

A Framework for Planning Staff Development

Some schools and districts see Dimensions as offering an important focus

during their planning of staff development and as a way of organizing the

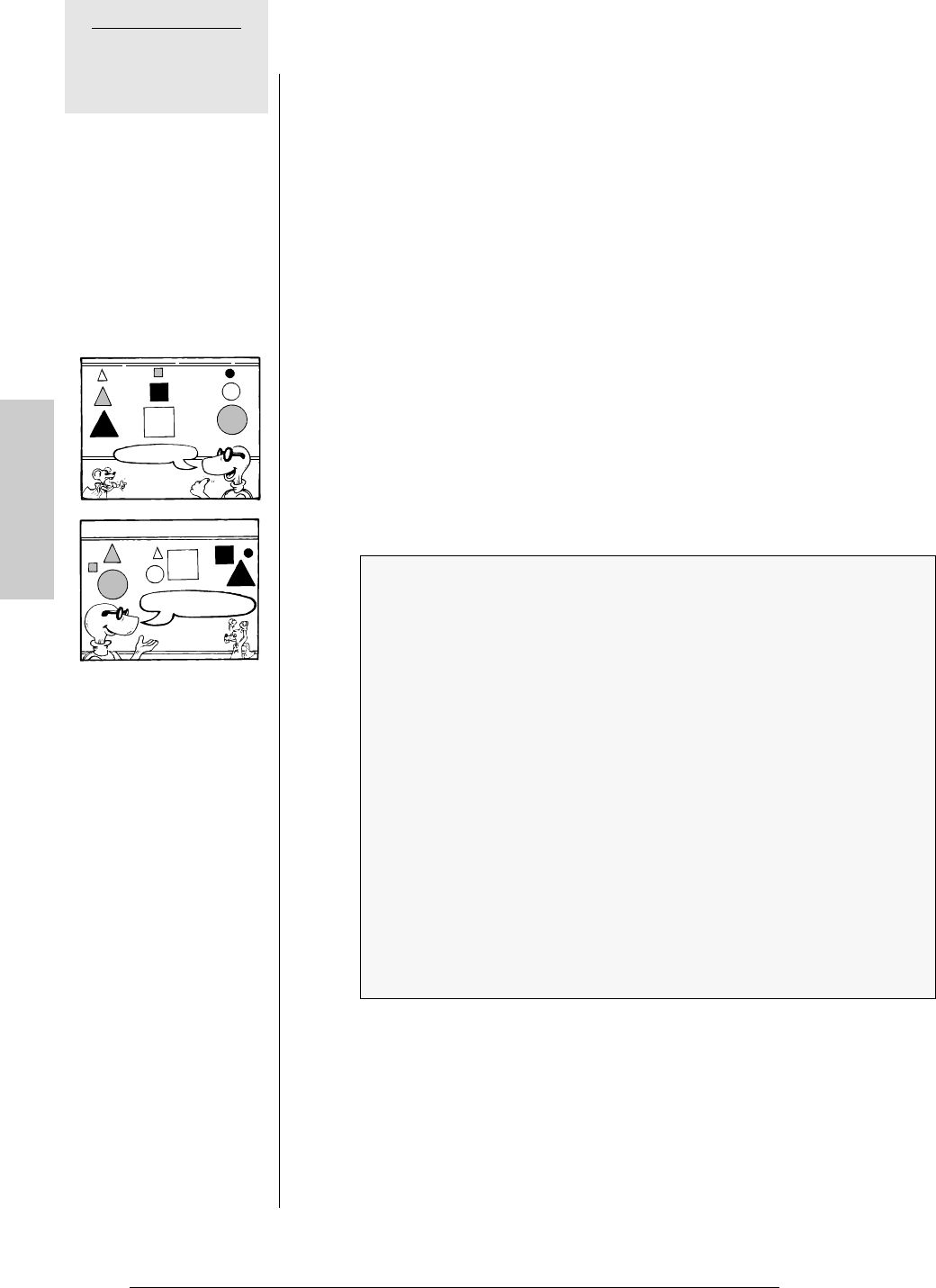

diverse inservice experiences offered in the district. The matrix in Figure A.2

(see next page) graphically represents this organization. Down the left-hand

side is an outline of the components of the Dimensions model. Planning for

professional development begins here, whether for individuals or an entire

staff. The first question staff developers would ask is, “What part of the

learning process needs to be improved?” After answering that question,

resources for seeking the improvement are identified across the top of the

matrix. These resources might includes programs, strategies, individuals, or

books that can be used to achieve the desired learning goal. There might be

many resources available that complement and supplement each other and

could, therefore, all be offered to those seeking the improvement in learning.

When any resource is identified, the matrix allows for indicating clearly

which aspects of the learning process might be enhanced if people were to

select and use that resource. Notice that the focus is on the learning process

rather than on the resource.

A Structure for Planning Curriculum and Assessment

One reason that the Dimensions of Learning model was created was to

influence the planning of curriculum and assessment, both at the classroom

and the district level. It is particularly suited to planning instructional units

and creating assessments that are clearly aligned with curriculum, including

both conventional and performance instruments.

Within each dimension there are planning questions that can help to

structure the planning so that all aspects of the learning process are

addressed: for example, “What will I do to help students maintain positive

attitudes and perceptions?” or “What declarative knowledge are the students

learning?” Although it is important for the planner to ask powerful

questions, sometimes the answer may be that very little or nothing at all

will be planned to address that part of the model. It is not important to plan

something for every dimension; it is important to ask the questions for every

dimension during the planning process. More detailed explanations and

examples are included throughout this manual and in each planning section.

Those who use the Dimensions model to influence their assessment practices

quickly realize instruction and assessment are closely integrated but that

both conventional and performance-based methods of assessment have a role.

Specific recommendations for assessment are included at the end of this

manual.

“The Dimensions model

validates so much of what

we were already doing in

our classrooms. It gives us a

common structure and

vocabulary with which to

discuss and plan professional

activities throughout the

school.”

—An elementary

school principal

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 9

10

Teacher’s Manual

Attitudes & Perceptions

I. Classroom Climate

A. Acceptance by Teachers and Peers

B. Comfort and Order

II. Classroom Tasks

A. Value and Interest

B. Ability and Resources

C. Clarity

Acquire & Integrate Knowledge

I. Declarative

A. Construct Meaning

B. Organize

C. Store

II. Procedural

A. Construct Models

B. Shape

C. Internalize

Extend & Refine Knowledge

Comparing

Classifying

Abstracting

Inductive Reasoning

Deductive Reasoning

Constructing Support

Analyzing Errors

Analyzing Perspectives

Use Knowledge Meaningfully

Decision Making

Problem Solving

Invention

Experimental Inquiry

Investigation

Systems Analysis

Habits of Mind

Critical Thinking

Creative Thinking

Self-Regulated Thinking

Resources for Improvement

Dimensions of Learning Outline

FIGURE A.2

M

ATRIX FOR PLANNING STAFF DEVELOPMENT

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 10

11

Teacher’s Manual

A Focus for Systemic Reform

The most comprehensive use of the Dimensions model is as an organizational

tool to ensure that the entire school district is structured around and

operating with a consistent attention to learning. The model provides a

common perspective and a shared language. Just as curriculum planners ask

questions in reference to each dimension during planning, people in every

part of the school system ask similar questions as they create schedules,

select textbooks, create job descriptions, and evaluate the effectiveness of

programs.

These four uses of the model are offered only as examples. There is no reason

to select only from among these four options; the purpose of the model is to

help you define and achieve your goals for student learning. The model is a

structure that should allow for and encourage a great deal of flexibility.

Using This Manual

Understanding the Dimensions of Learning model can greatly improve your

ability to plan any aspect of education. This manual is designed to help

teachers and administrators study learning through the Dimensions model

and to provide guidance for those who are using the model to achieve their

specific individual, school, and district goals. The sections of the manual, as

well as the format used to organize the information and recommendations,

are described below.

1. There is a chapter for each dimension that includes an introduction,

suggestions for helping students to engage in the thinking involved in

that dimension, classroom examples to stimulate reflection and suggest

ways of applying the information, and a process for planning instruction

in the particular dimension.

2. The margins throughout the manual contain information that should

help you think about the ideas highlighted in each dimension and

pursue further study. You will find

• bibliographic references (shortened in some cases because of space),

which provide suggestions for further reading;

• quotes from documents that were used as references for the section;

• interesting and relevant quotes or thoughts, offered as ideas for

reflection;

• descriptions of implementation activities that have been used in

schools or districts;

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 11

• suggested materials that might be used in planning classroom

activities or that contain other strategies related to the dimension; and

• graphics that depict ideas addressed in the dimension.

3. The chapter “Putting It All Together” walks the reader through the

entire planning process and offers suggestions, different planning

sequences, and examples from units of study planned using the

Dimensions of Learning framework. This chapter also discusses critical

issues related to assessment techniques that can be used to collect data

on students’ performance in each of the dimensions; rubrics to facilitate

consistent, fair teacher judgment and to promote student learning; and

ideas for assigning and recording grades.

The strategies and resources highlighted throughout this manual are only a

small percentage of those that could have been included in support of each

dimension. If cost had not been a consideration, this manual would have

been published as a loose-leaf notebook so that users could add their own

strategies and resources. Gathering additional ideas and suggestions should

be a goal for every professional educator. Hopefully, what is offered here will

contribute to the resources that master teachers already have gathered and

provide a beginning for those new to the profession.

12

Teacher’s Manual

What Is Dimensions

of Learning?

Introduction

intro chapter 4/16/09 9:23 AM Page 12

Dimension

1

DIMENSION 1

DoL Teacher TP/Div 4/17/09 7:49 AM Page 2

Dim 2 chapter-procedural 4/17/09 7:23 AM Page 1

DIMENSION 1

13

Teacher’s Manual

“I read once, ‘Billiard balls

react. People respond.’ This

reminds me that although I

recognize that I did not

cause my students to have

some of the negative

attitudes that they bring to

school, I am responsible for

having a repertoire of

effective strategies for

eliciting positive attitudes

that enhance students’

learning.”

—A mathematics

teacher in Missouri

1

Dimension 1

Attitudes and Perceptions

Introduction

Most people recognize that attitudes and perceptions influence learning. As

learners, we all have experienced the impact of our attitudes and perceptions

related to the teacher, other students, our own abilities, and the value of

assigned tasks. When our attitudes and perceptions are positive, learning is

enhanced; when they are negative, learning suffers. It is the shared

responsibility of the teacher and the student to work to maintain positive

attitudes and perceptions or, when possible, to change negative attitudes and

perceptions.

The effective teacher continuously works to influence attitudes and

perceptions, often so skillfully that students are not aware of her efforts.

Subtle though this behavior may be, it is a conscious instructional decision

to overtly cultivate specific attitudes and perceptions. In the next two

sections, you will find strategies and techniques for enhancing two types of

attitudes and perceptions: those related to the climate of the classroom and

those related to classroom tasks. You will find strategies, techniques,

recommendations, and classroom examples to refer to when you are

planning to

• elicit positive attitudes and perceptions from learners and

• teach the learner how to maintain positive attitudes and perceptions

or change negative or detrimental ones.

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 13

14

Teacher’s Manual

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Introduction

Dimension 1

DIMENSION 1

This dimension includes two main sections as described below.

I. Helping Students Develop Positive Attitudes and Perceptions About

Classroom Climate

• Feel accepted by teachers and peers

• Experience a sense of comfort and order

II. Helping Students Develop Positive Attitudes and Perceptions About

Classroom Tasks

• Perceive tasks as valuable and interesting

• Believe they have the ability and resources to complete tasks

• Understand and be clear about tasks

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 14

DIMENSION 1

15

Teacher’s Manual

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Helping Students Develop Positive Attitudes

and Perceptions About Classroom Climate

Educators recognize the influence that the climate of the classroom has on

learning. A primary objective of every teacher, then, is to establish a climate

in which students

• feel accepted by teachers and peers and

• experience a sense of comfort and order.

The following strategies are designed for teachers to use to help students

enhance their attitudes and perceptions and to help students develop their

own strategies for enhancing attitudes and perceptions.

1. Help students understand that attitudes and perceptions

related to classroom climate influence learning.

Students vary in the degree to which they understand the relationship

among attitudes, perceptions, and learning. Emphasize with students that

• attitudes and perceptions related to classroom climate are critical to

learning, and

• it is the shared responsibility of the students and the teacher to keep

attitudes as positive as possible.

Help students understand that it is important to maintain a climate that

positively affects learning and that this means much more than simply “good

behavior.” There are many ways to help build this understanding:

• Share with students how your own learning (from kindergarten to

where you are today) has been influenced by your attitudes and

perceptions related to acceptance and to comfort and order. Include

in your discussion strategies you use, or have used, as a learner to

maintain positive attitudes and perceptions and how those strategies

have worked to enhance your learning. Then ask students to share

their experiences and the effectiveness of strategies they have used.

• Present a variety of hypothetical situations in which an individual

student’s negative attitude is affecting his or her learning. Ask

students to discuss why the student might have a negative attitude

and to suggest ways in which the situation might be resolved.

An elementary school

principal regularly displays

positive quotes about

learning on bulletin boards

and posters throughout the

school (e.g., “Attitudes are

the mind’s paintbrush”). He

periodically asks students

what they think each quote

means and how the idea

might enhance their

learning.

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 15

DIMENSION 1

16

Teacher’s Manual

• Help students become aware of fictional, historical, or famous people

who have enhanced their own learning by maintaining positive

attitudes. Newspaper articles, books, films, or television programs

are good resources for examples.

Feel Accepted by Teachers and Peers

Everyone wants to feel accepted by others. When we feel accepted, we are

comfortable, even energized. However, when we do not feel accepted, we are

often uncomfortable, distracted, or depressed. The stakes are particularly

high in the classroom. Students who feel accepted usually feel better about

themselves and school, work harder, and learn better. Your job as a teacher

begins with helping students to feel accepted by both you and their peers.

There are a number of ways you can accomplish this.

2. Establish a relationship with each student in the class.

We all like to experience being “known.” A simple gesture such as being

greeted by name can be validating. Students are no different. Establishing

relationships with them communicates that you respect them as individuals

and contributes to their successful learning. There are many ways to

establish these relationships:

• Talk informally with students before, during, and after class about

their interests.

• Greet students outside of school, for instance at extracurricular

events or at stores.

• Single out a few students each day in the lunchroom and talk to

them.

• Be aware of and comment on important events in students’ lives,

such as participation in sports, drama, or other extracurricular

activities.

• Compliment students on important achievements in and outside of

school.

• Include students in the process of planning classroom activities;

solicit their ideas and consider their interests.

• Meet students at the door as they come into class and say hello to

each child, making sure to use his or her first name.

McCombs & Whisler (1997)

The Learner-Centered

Classroom and School

For strategies for

“invitational learning,” see

Purkey (1978) Inviting School

Success.

Combs (1982) A Personal

Approach to Teaching

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 16

DIMENSION 1

17

Teacher’s Manual

• Take time at the beginning of the school year to have students

complete an interest inventory. Use this information throughout the

year to connect and converse with students about their interests.

• Call students before the school year begins and ask a few questions

about them to begin to establish a relationship.

• Call parents and share anecdotes that focus on something about

which parents and students can be proud.

3. Monitor and attend to your own attitudes.

Most teachers are aware that when their attitudes toward students are

positive, student performance is enhanced. However, they are sometimes

unaware of favoring or having higher expectations for certain students.

Increasing awareness of, monitoring, and attending to your own attitudes

can contribute to students feeling accepted. The following process might be

helpful when you are aware of a negative attitude:

1. Before class each day, mentally review your students, noting those

with whom you anticipate having problems (either academic or

behavioral).

2. Try to imagine these “problem” students succeeding or engaging in

positive classroom behavior. In other words, replace your negative

expectations with positive ones. This is a form of mental rehearsal.

It’s useful to review the positive images more than once before

beginning the instructional day.

3. When you interact with students, try consciously to keep in mind

your positive expectations.

4. Engage in equitable and positive classroom behavior.

Research suggests that even those teachers who are most aware of their

interactions with students unwittingly can give more attention to high

achievers than to low achievers and call on one gender more than the other.

It is important to do what is necessary to ensure that all students are

attended to positively so that they are likely to feel accepted. To this end,

there are several classroom practices that are useful:

• Make eye contact with each student in the room. You can do this by

scanning the entire room as you speak. Freely move about all sections

of the room.

Good (1982) “How

Teachers’ Expectations

Affect Results”

Rosenshine (1983)

“Teaching Functions in

Instructional Programs”

Covey (1990) The 7 Habits

of Highly Effective People

Rosenthal & Jacobson

(1968) Pygmalion in the

Classroom

Kerman, Kimball, & Martin

(1980) Teacher Expectations

and Student Achievement

Sadker & Sadker (1994)

Failing at Fairness

Grayson & Martin (1985)

Gender Expectations and

Student Achievement

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 17

DIMENSION 1

18

Teacher’s Manual

• Over the course of a class period, deliberately move toward and be

close to each student. Make sure that the seating arrangement allows

you and students clear and easy access to move around the room.

• Attribute the ownership of ideas to the students who initiated them.

(For instance, in a discussion you might say, “Dennis has just added

to Mary’s idea by saying that. . . .”)

• Allow and encourage all students to be part of class discussions and

interactions. Make sure to call on students who do not commonly

participate, not just students who respond most frequently.

• Provide appropriate “wait time” for all students, regardless of their

past performance or your perception of their abilities.

5. Recognize and provide for students’ individual differences.

All students are unique. They come to the educational setting with varying

experiences, interests, knowledge, abilities, and perceptions of the world. As

research and experience tell us, people also vary in their preferred styles of

learning and thinking; their types and degree of intelligence; their cultural

backgrounds that include varying perspectives and customs; and their

particular needs due to background, physical or mental attributes, and

learning deficits or strengths. Teaching that recognizes and provides for such

differences results in students feeling more accepted because of greater

personalization. The result is increased and improved student learning. The

following strategies can help teachers recognize and provide for students’

individual differences:

• Use materials and literature from around the world.

• Design a classroom setup that accommodates varying physical needs.

• Plan varied classroom activities so that all students have

opportunities to learn in their preferred style.

• Allow students choice in projects so that they may use their

strengths and capitalize on their interests as they demonstrate their

learning.

• Include in your lessons examples of successful people talking about

how they recognized and capitalized on their differences.

Hunter (1976) Improved

Instruction

Rowe (1974) “Wait-time

and Rewards as

Instructional Variables,

Their Influence on

Language, Logic and Fate

Control”

Gardner (1983) Frames of

Mind; Gardner (1993)

Multiple Intelligences

McCarthy (1980) The

4MAT System

Wlodkowski & Ginsberg

(1995) Diversity and

Motivation

Dunn & Dunn (1978)

Teaching Students Through

Their Individual Learning

Styles

Gregorc (1983) Student

Learning Styles and Brain

Behavior

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 18

DIMENSION 1

19

Teacher’s Manual

6. Respond positively to students’ incorrect responses or lack of

response.

Students participate and respond when they think it is okay to make mistakes

or to not know an answer, that is, when they know that they will continue to

be accepted in spite of errors or lack of information. How you respond to a

student’s incorrect response or lack of response is an important factor in

creating this sense of safety for students. When students give wrong answers or

no answer, dignify their responses by trying one of the following suggestions:

• Emphasize what was right. Give credit to the aspects of an incorrect

response that are correct and acknowledge when the student is

headed in the right direction. Identify the question that the incorrect

response answered.

• Encourage collaboration. Allow students time to seek help from

peers. This can result in better responses and can enhance learning.

• Restate the question. Ask the question a second time and allow time

for students to think before you expect a response.

• Rephrase the question. Paraphrase the question or ask it from a

different perspective, one that may give students a better

understanding of the question.

• Give hints or cues. Provide enough guidance so that students

gradually come up with the answer.

• Provide the answer and ask for elaboration. If a student absolutely

cannot come up with the correct answer, provide it for him and then

ask him to say it in his own words or to provide another example of

the answer.

• Respect the student’s option to pass, when appropriate.

7. Vary the positive reinforcement offered when students give

the correct response.

Praise is perhaps the most common form of positive reinforcement teachers

provide when students give correct responses. There are times, however,

when praise can have little effect—or even a negative effect—on students’

perceptions of their contributions to the class. For example, students may

perceive praise as empty, patronizing, or automatic, especially when they are

frequently correct and accustomed to praise; enthusiastic praise of a correct

response may communicate to other students that the issue is closed and cut

off other answers; some students might be embarrassed when singled out,

praised, or otherwise reinforced publicly.

Hunter (1969) Teach More

Faster!

Brophy (1982) Classroom

Organization and Management

Brophy & Good (1986)

“Teacher Behavior and

Student Achievement”

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 19

DIMENSION 1

20

Teacher’s Manual

There are alternative ways to respond to correct answers that can reinforce

and validate students:

• Rephrase, apply, or summarize students’ responses. (“That would also

work if. . . .”)

• Encourage students to respond to one another. (“What do you think?

Is Juan correct?”)

• Give praise privately, particularly to students who may be

embarrassed by being acknowledged in front of their peers. (“Ian,

today in class I was very pleased when you. . . .”)

• Challenge the answer or ask for elaboration. (“Devon, that seems to

contradict. . . .”)

• Specify the criteria for the praise being given so that students

understand why they are being praised. (“Barb, that answer helps us

to see a new way of. . . .”)

• Help students analyze their own answers. (“How did you arrive at

that answer?”)

• Use your tone of voice to ensure that students understand what is

being reinforced.

• Use silence along with nods or other body language, such as eye

contact, that encourages students to elaborate on their answers.

8. Structure opportunities for students to work with peers.

Opportunities to work in groups toward a common goal, when structured

appropriately, can help students feel accepted by their peers. Be sure to set

up groups that help foster positive peer relations and that enhance student

achievement. There are a number of strategies that will increase the success

of group work:

• Teach students the skills necessary for group interactions.

• Identify learning goals in advance and make them very clear for

students.

• Monitor the group to suggest additional information, resources, or

encouragement as necessary.

• Structure the learning experience so that every student in the group

has a responsible role in completing the task.

• Make sure that each student in the group is acquiring the targeted

knowledge.

Johnson, Johnson, &

Holubec (1994) New Circles

of Learning

Slavin (1983) Cooperative

Learning

Kagan (1994) Cooperative

Learning Structures

Shaw (1992) Building

Community in the Classroom

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 20

DIMENSION 1

21

Teacher’s Manual

9. Provide opportunities for students to get to know and accept

each other.

Some students make friends and are accepted more readily than others.

Other students have a difficult time accepting peers who are different from

themselves. Take the time to provide opportunities for students to get to

know each other, to see that in spite of some apparent differences they are

alike in many ways. Encourage them to establish relationships with

individuals and groups other than those with whom they already have

friendships. Teachers commonly provide opportunities for students to get to

know each other at the beginning of the school year. Providing opportunities

at other times of the year can have positive effects especially when students

understand that the goal is to improve learning for all. Some specific

strategies might include the following:

• Ask each student to interview another student at the beginning of

the year and then introduce that student to the rest of the class.

• Have students make posters representing their backgrounds, hobbies,

and interests. Students might include pictures of themselves from

birth to the present. Then hang these posters around the classroom,

or ask students to present them to the class.

• Encourage all students to share about themselves and their heritage.

This activity might be particularly interesting for students if there

are others in the class from different countries and cultures.

• Have each student write his or her name on a sheet of paper. Ask

them to pass their papers around and write one positive comment on

each of the other students’ sheets. Encourage students to avoid

repeating a comment that is already included on the page. Return

the completed “positive-o-grams” to their “owners” to keep.

• Have students design and make a “nameplate” that represents their

likes and dislikes with a collage, pictures, or drawings. These can be

placed on students’ tables or desks during the first weeks of school.

• Use structured “get-to-know-you” activities periodically throughout

the year.

10. Help students develop their ability to use their own strategies

for gaining acceptance from their teachers and peers.

Students need to accept increasing responsibility for gaining acceptance from

teachers and peers. However, many students will need opportunities to

identify and practice using strategies for gaining acceptance. You might

Canfield & Wells (1976)

100 Ways to Enhance Self-

concept in the Classroom

Smuin (1978) Turn-ons: 185

Strategies for the Secondary

Classroom

Whisler & McCombs (1992)

Middle School Advisement

Program

Carkhuff (1987) The Art of

Helping

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 21

DIMENSION 1

“People develop feelings

that they are liked, wanted,

acceptable, and able from

having been liked, wanted,

accepted, and from having

been successful.”

—Arthur W. Combs

22

Teacher’s Manual

periodically ask students to identify and discuss potential strategies and then

record them in a way that can be regularly updated and used (e.g., on

bulletin boards or overheard transparencies or in notebooks). Remember to

emphasize with students that using strategies to gain acceptance positively

influences the learning environment for everyone.

Suggested strategies for students to use in gaining acceptance from their

teachers include the following:

• If you are developing negative attitudes toward a teacher, make an

appointment to meet with him or her one-on-one. Frequently, a

personal interaction will establish a more positive relationship.

• Treat teachers with respect and courtesy. When talking with them,

make eye contact and use appropriate language.

• If a teacher seems angry or irritable in class, don’t take it personally.

Teachers are human; they have good days and bad days just like

everyone else.

• Work hard. Regardless of your level of achievement, when a teacher

perceives you are trying to learn, the relationship between you and

the teacher will likely be a positive one.

Suggested strategies for students to use in gaining acceptance from their

peers include the following:

• Be interested rather than interesting. When you are first getting to

know people, spend more time asking them about themselves rather

than telling them about yourself.

• Compliment people on their positive characteristics.

• Avoid reminding people about their negative qualities or about bad

things that have happened to them.

• Treat people with common courtesy. Treat them as you would like to

be treated or as you would treat an honored guest.

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 22

DIMENSION 1

23

Teacher’s Manual

“The physical setting of a

high school should nurture

a student in much the same

way that the clean, safe

interior of a home makes

the youngster feel

comfortable and secure.”

—NASSP (1996)

Breaking Ranks: Changing an

American Institution,

p. 34.

Carbo, Dunn, & Dunn

(1986) Teaching Students to

Read Through Their

Individual Learning Styles

Experience a Sense of Comfort and Order

A student’s sense of comfort and order in the classroom affects his or her

ability to learn. Comfort and order as described here refer to physical

comfort, identifiable routines and guidelines for acceptable behavior, and

psychological and emotional safety.

A student’s sense of comfort in the classroom is affected by such factors as

room temperature, the arrangement of furniture, and the amount of physical

activity permitted during the school day. Researchers investigating learning

styles (e.g., Carbo, Dunn, and Dunn, 1986; McCarthy, 1980, 1990) have

found that students define physical comfort in different ways. Some prefer a

noise-free room; others prefer music. Some prefer a neat, clutter-free space;

others feel more comfortable surrounded by their work-in-progress.

Teachers can draw on the extensive research available on classroom

management (e.g., Anderson, Evertson, and Emmer, 1980; Emmer, Evertson,

and Anderson, 1980) to guide them in addressing issues about classroom

order. This research shows, for example, that explicitly stated and reinforced

rules and procedures create a climate that is conducive to learning. If

students do not know the parameters of behavior in a learning situation, the

environment can become chaotic.

Most educators understand the importance of involving students in making

decisions about the classroom climate. When students are involved in decision

making, individual needs are more likely to be met. The following subsections

cover strategies for establishing a sense of comfort and order in the classroom.

11. Frequently and systematically use activities that involve

physical movement.

Many students will be more comfortable if they do not have to remain in

one position for a long time. There are many ways to allow—even

encourage—movement during regular classroom instruction:

• Periodically take short breaks in which students are allowed to stand

up, move about, and stretch.

• Set up classroom tasks that require students to gather information on

their own or in small groups, using resources that are away from

their desks.

• Systematically switch from activities in which students must work

independently at their own desks to activities in which they must

organize themselves in small groups in different areas of the room.

• When students’ energy level begins to wane, take an exercise break

for two to five minutes to change the routine.

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 23

DIMENSION 1

12. Introduce the concept of “bracketing.”

Bracketing is a process of maintaining focus and attention by consciously

blocking out distractions. In the first step, the learner recognizes that it is

time to pay attention. Next, the learner acknowledges his or her distracting

thoughts and mentally frames or “brackets” them. Finally, the learner makes a

commitment to avoid thinking about the distracting thoughts. Bracketing can

be accomplished in a variety of ways. You might suggest to students that they

• Use self-talk. (“I won’t think about it now.”)

• Designate a later time to think about it. (“I will think about it at the

end of class.”)

• Mentally picture pushing the distracting thoughts out of their head.

Bracketing contributes to a sense of comfort in the classroom because it

helps students to focus on one idea or task at a time. To help students

understand and practice bracketing, you might use the following strategies:

• Model bracketing by talking through the process during an

appropriate transition time (e.g., after lunch or before recess). You

might say that you are “changing channels” in preparation for

beginning a new task.

• Provide personal examples and ask students to share their examples

of when bracketing was productive or not very useful.

• Share with students examples, testimonials, or videos of well-known,

accomplished people (e.g., Olympic athletes, performers, and

political leaders) explaining how they have used strategies similar to

bracketing to stay focused.

• Use examples from literature in which students might find explicit

references or infer that a character bracketed information to persevere

or stay focused.

• If a student’s distracting thoughts are consuming or urgent, suggest

that he focus on the thoughts for a minute or two and then “put

them in a box” to retrieve after class. You can use this box

figuratively, or you might have a box on your desk for this purpose.

13. Establish and communicate classroom rules and procedures.

Well-articulated classroom rules and procedures are a powerful way of

conveying a sense of order to students. This can be accomplished in a

number of ways:

Marzano & Arredondo

(1986) Tactics for Thinking

24

Teacher’s Manual

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 24

DIMENSION 1

• Generate clear rules and standard operating procedures for the

classroom (either independently or collaboratively with the class).

Figure 1.1 lists some categories for which rules and procedures are

commonly specified.

• Have students discuss what rules and procedures they think would

be appropriate for the classroom.

• Communicate rules and procedures by discussing their meaning or

rationale, providing students with a written list, posting them in the

classroom, role playing them, or modeling their use.

• Specify when rules and procedures apply and how they may vary

depending on the context (e.g., “At the beginning of class. . . .” or

“During exams. . . .”).

• When a situation occurs that requires an exception to the rules,

acknowledge the change and explain the reasons for the exception.

• When providing students with feedback about their behavior,

identify the specific behavior that was consistent with the rules of

the class. In addition, let students know how they contributed to

their own success and to the success of others.

• Enforce rules and procedures quickly, fairly, and consistently.

FIGURE 1.1

C

ATEGORIES FOR CLASSROOM RULES

1. Beginning class

2. Room/school areas

3. Independent work

4. Ending class

5. Interruptions

6. Instructional procedures

7. Noninstructional procedures

8. Work requirements

9. Communicating assignments

10. Checking assignments in class

11. Grading procedures

12. Academic feedback

25

Teacher’s Manual

Fisher et al. (1978) Teaching

Behaviors, Academic Learning

Time and Student Achievement

Evertson et al. (1981)

Organizing and Managing the

Elementary Classroom

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop

Positive Attitudes and

Perceptions About Classroom

Climate

Dimension 1

Dim 1 chapter 1/1/04 12:12 AM Page 25

DIMENSION 1

14. Be aware of malicious teasing or threats inside or outside of

the classroom, and take steps to stop such behavior.

Personal safety is a primary concern for everyone. It is difficult to learn when

you feel physically or psychologically unsafe. There are several things you

can do to help your students feel safe:

• Establish clear policies about the physical safety of students. The clearer

you can be about policies regarding physical safety, the stronger the

message will be to students. Policies and rules should include a

description of the consequences of threatening or harming others.

• Make sure your students know that you are looking out for their

safety and well-being. Be certain that they understand that you will

take action on their behalf.

• Pinpoint the students who are threatening or teasing others and

those who are being threatened or teased. Talk with the students to

find out why this is happening.

• Occasionally patrol the perimeter of the school, looking for threatening

aspects of the environment. Check areas within the school where

students could be threatened (e.g., bathrooms or hallways).

• If necessary, meet with parents to discuss problems.

• Establish an environment in which “put downs” are not acceptable.

15. Have students identify their own standards for comfort and

order.

Teachers may spend much of their time in their classrooms prompting

students to meet agreed-upon standards for comfort and order. However, the

goal is for students to learn to identify their own standards for comfort and

order based on their preferences and understandings about accepted social

behavior.

Some classroom activities can help students take on more responsibility for

their own comfort and order, while being attentive to the needs of those

around them as well:

• Ask students to describe in some detail how they would arrange

their personal space (e.g., their desk area or work space) to achieve a

sense of comfort and order. This description might include a

checklist that students could refer to later. From time to time, ask

students to assess the extent to which they are keeping their personal

space up to the standards they have identified.

Maslow (1968) Toward a

Psychology of Being

Edmonds (1982) “Programs

of School Improvement: An

Overview”

Carbo, Dunn, & Dunn

(1986) Teaching Students to

Read Through Their

Individual Learning Styles

Hanson, Silver, & Strong

(1986) Teaching Styles and

Strategies

26

Teacher’s Manual

Attitudes & Perceptions

✔ Helping Students Develop