Ethical Trading Initiative

External Evaluation Report

IOD PARC is the trading name of International

Organisation Development Ltd//

Omega Court

362 Cemetery Road

Sheffield

S11 8FT

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 114 267 3620

www.iodparc.com

Prepared for //

Ethical Trading Initiative

Date //16/04/2015

By// IOD PARC

1

1. Contents

1. Contents 1

1. Introduction 1

1.1. Introduction to the Ethical Trading Initiative 1

1.2. Purpose and Scope of the Evaluation 3

1.3. The Evaluation Process 4

2. Setting: ETI within the Broader Landscape 6

2.1. Workers’ Rights: Global Trends 6

2.2. Initiatives Similar to ETI 9

2.3. The Role of the ‘Private Sector’ in Development, the UNGPs and ETI 9

2.4. ETI – the 2015-2020 Five Year Strategy 11

3. The Major Findings 14

3.1. ETI Results 15

3.2. The Effectiveness of ETI’s Multi-stakeholder Processes 18

3.3. Achieving Impact 19

3.4. Summary on Results 20

3.5. ETI Capabilities: the Reporting Framework 20

3.6. ETI capabilities: a Competent Team 22

3.7. ETI Capabilities: the Funding Gap 22

3.8. Summary on Capabilities 23

4. Overall Conclusions and Recommendations 24

4.1. How ETI has Progressed and is Positioned 24

4.2. A Shift needed in ETI Orientation, Emphasis, Pace and Capacity 25

4.3. Recommendations 26

1

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to the Ethical Trading Initiative

The ethical complexities of international trade have been deepened by globalisation and the rise of

transnational supply chains. Several issues pertaining to labour rights remain unresolved to this day.

Around the world, labour rights, including freedom of association and the right to a living wage, are

routinely disregarded or ignored and pressures for more informal contracting of workers are

increasing.

Within the landscape of protecting workers’ rights there has been a fundamental transformation in

the type of actors involved. In particular:

“…by the early 1990s, virtually all industrialised countries provided a base for numerous multi-

national corporations, which were fast becoming ‘the dominant form of organisation

responsible for the international exchange of goods and services’… …In the wake of this growth

and globalisation, [MNC’s] found themselves in the extraordinary position of outperforming the

national economies of states – a dramatic turn of events considering that hitherto nation-states

had been considered the primary, if not exclusive, actors within the international order.”

1

A very real risk was that this trend could result in a ‘race to the bottom’, “in which governments seek

to attract foreign direct investment by removing policies that, although potentially socially desirable,

are viewed as unattractive by firms”.

2

It was against this challenging backdrop that the ETI was formed in 1998, by “a group of UK

companies, NGOs and trade union organisations”. The aim was to build “an alliance of organisations

that would work together to define how major companies should implement their codes of labour

practice in a credible way – and most importantly, in a way that has maximum impact on workers.”

3

Pursuant to this goal, the ETI developed its ‘Base Code’ – a normative document founded upon the

conventions of the ILO, which the Initiative’s member companies voluntarily commit to implement.

The ETI’s membership base has expanded significantly since its inception – from just four companies

in 1998 to over 70 in 2015, with combined revenue of over £166 billion

4

, “collectively reaching nearly

10 million workers across the globe”.

In its early days, the ETI registered a number of tangible achievements, chief amongst which was an

important contribution to placing the idea of ‘ethical trade’ (a position to which many companies had

previously only made vague overtures) firmly in the consciousness and then in the planning of a

group of progressive UK retailers. By highlighting issues pertaining to workers’ rights around the

globe, and thereby enhancing their visibility in the eyes of companies, governments and consumers,

the ETI secured several commitments from international retailers that subsequently translated into

qualitative improvements in labour conditions around the world. However, by 2006 it was recognised

that despite progress in many of the areas identified in the ETI’s Base Code, improvements remained

discrete, insofar as they were confined to specific groupings of workers within company supply chains.

1

Blitt, R. (no date) Beyond Ruggie’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Charting and Embracive Approach to Corporate Human

Rights Compliance ; Texas International Law Journal, Volume 48, Issue 1, Page. 36, available at:

http://www.tilj.org/content/journal/48/num1/Blitt33.pdf - accessed 09/02/2015

2

Davies, R. & Vadlamannti K.C. (2011) A Race to the Bottom in Labour Standard? An Empirical Investigation, IIIS Discussion Paper no. 385,

available at: http://www.tcd.ie/iiis/documents/discussion/pdfs/iiisdp385.pdf - accessed 02/02/2015

3

Ethical Trading Initiative (2015) ETI’s Origins, available at: http://www.ethicaltrade.org/origins-eti - accessed -02/02/2015

4

Ethical Trading Initiative (2015) Our Members, available at: http://www.ethicaltrade.org/about-eti/our-members - accessed 02/02/2015

2

The benefits of the ETI’s individual programmes and projects did not diffuse across the larger

landscape. Furthermore, implementation of the Base Code by member organisations was largely

limited to action on its more ‘visible’ principles, including health and safety and child labour, and did

not extend to more long term principles such as freedom of association, which would ultimately

enhance the capacity of workers to shape their own working environments.

5

The threat facing the ETI’s vision was clear and at that time it was acknowledged: that the Initiative’s

role could become relegated to that of a ‘convenient smokescreen’ – a subscription-based forum

through which member organisations could publicise relatively minor improvements in their supply

chains, while effectively ignoring the wider picture. The need for a strategic reorientation was evident,

and this led to the move in 2011 whereby the Initiative opted to focus on examining supply chains in

context; looking at the totality of workers conditions within a supply chain – what is happening and

why it is happening – and from this, looking for a course of collaborative action by members which

seeks to address issues systemically rather than a short-term piecemeal localised response.

The set

6

of a number of selected supply chain initiatives was developed as the de facto ‘R&D’ arm of

the ETI and as part of an overall ‘programming’ vision designed to be complemented by the

emergence and strengthening of a knowledge and learning department within ETI – which would

seek out lessons and turn this into knowledge for wider use and thereby ETI reach – and the

strengthening of an approach that would galvanise the activity and accountability of the membership.

The “supply chain initiatives were aimed at addressing the root causes of poor working conditions in

relation to the specific contexts of those supply chains.”

7

This programming approach was captured

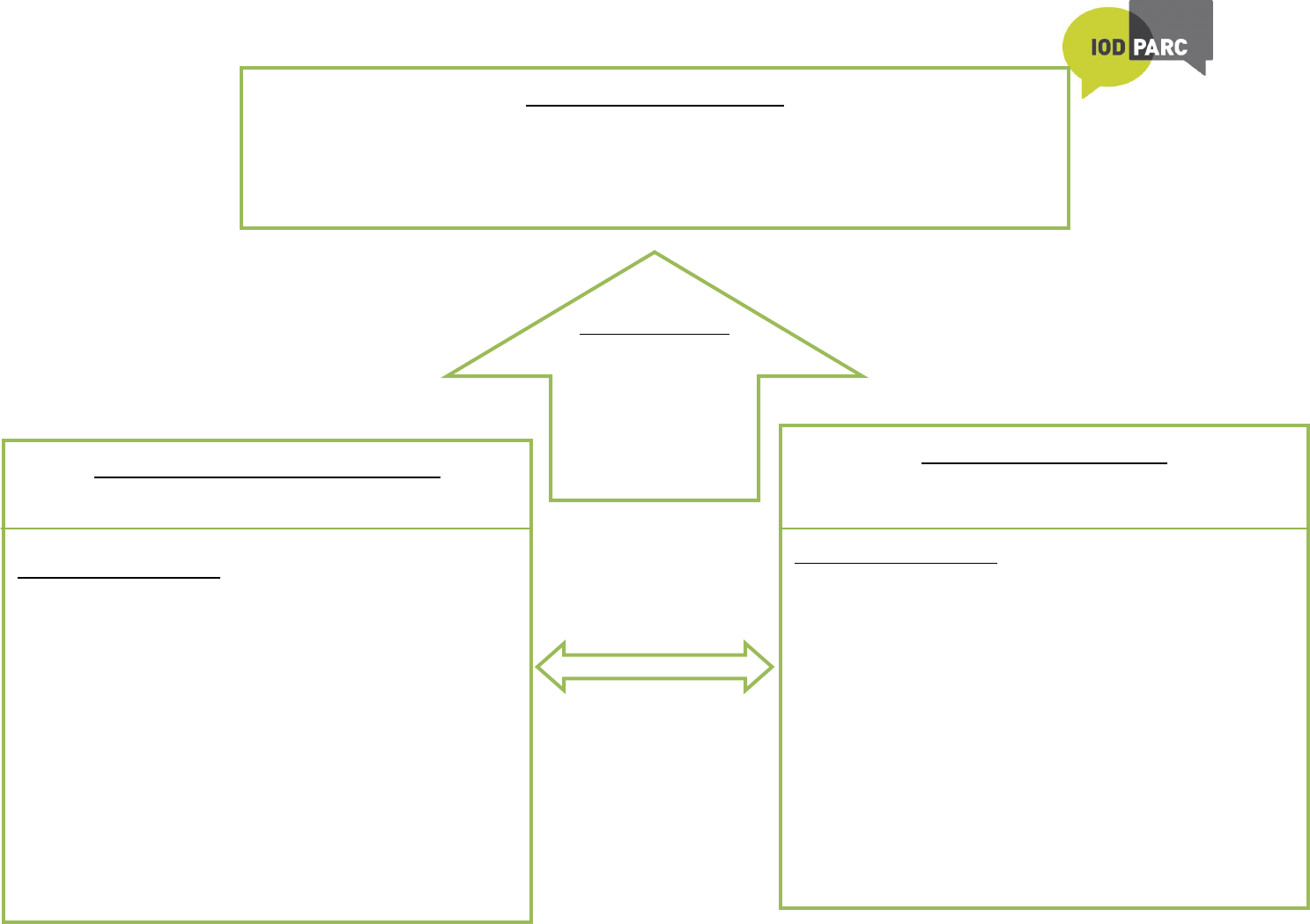

within the results framework (extracted below) and reporting to DFID under the ETI PPA agreement.

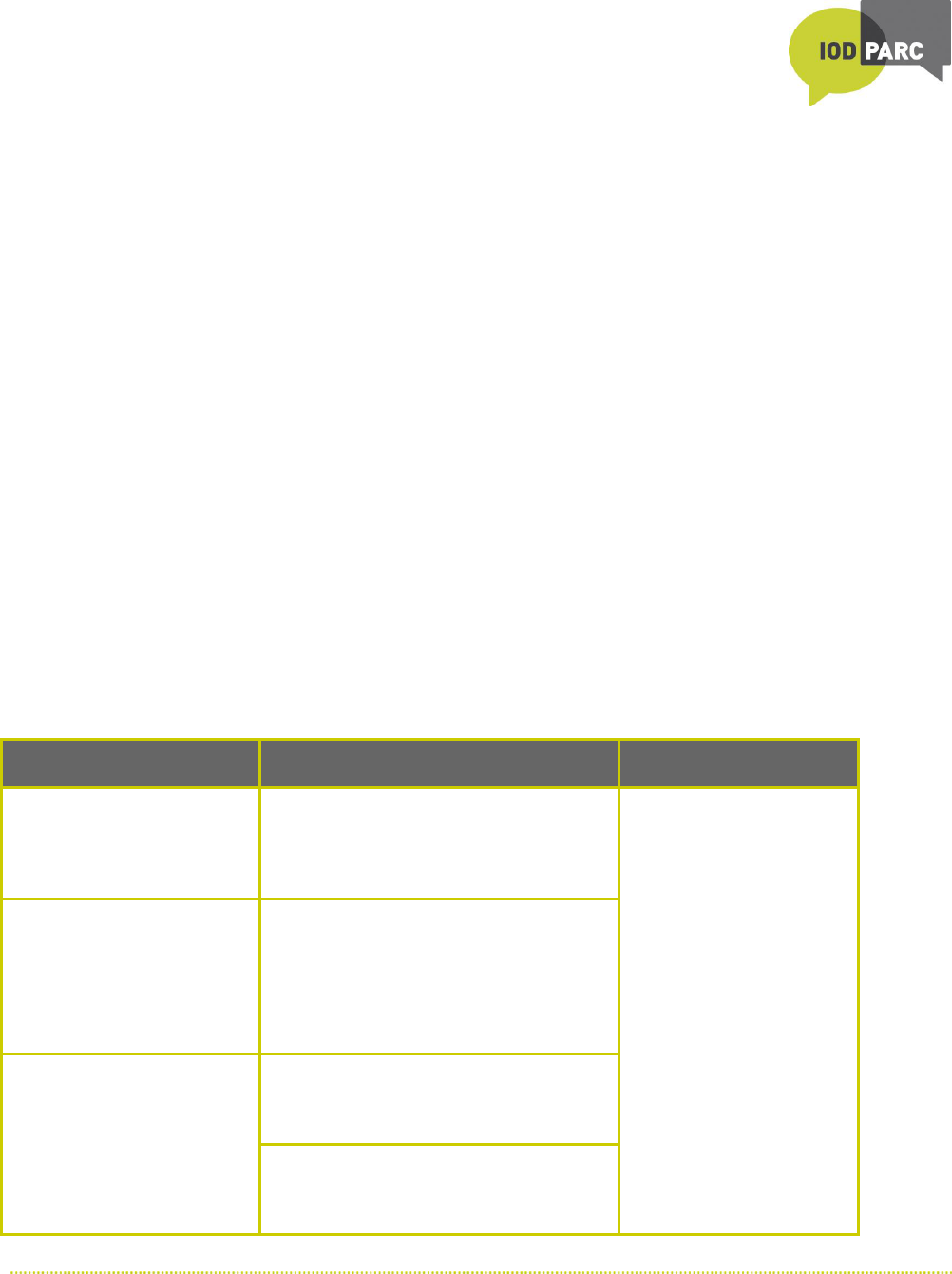

Immediate Outcomes

Intermediate Outcomes

Higher-level Outcomes

Choice of supply chains is

agreed through tripartite

discussion

Factors that contribute to exploitation

and discrimination in supply chains are

understood through joint assessment

and comprehensive analysis

Improved working

conditions for poor and

vulnerable workers,

especially women, in

prioritised supply chains

Programme of work in

prioritised supply chains is

designed and agreed

through tripartite

discussion

Collaborative programmes between

businesses, civil society and

governments are implemented within

priority supply chains

Robust monitoring and

evaluation framework

tracks impact and drives

results-based-programming

Root causes (rather than the symptoms)

of workers’ rights abuses are integrated

in/addressed through programmes

Learning on key issues and cross-

cutting themes is captured and shared

widely among membership and beyond

5

Institute of Development Studies (2006), Report on the ETI Impact Assessment.

6

Between 2010-2012 priority supply chains were identified and mapped using the following criteria: The number of workers in the supply chains;

The level of harm or vulnerability to harm experienced by workers; The importance of the supply chain to members; The ETI’s ability to leverage

change in the supply chain; The potential to replicate lessons learnt. Additionally, supply chains were classified according to the following ‘product

category groups’: Food and Farming (F&F) ; Hard Goods and Household (HG&H); Apparel and Textiles (A&T). A substantial amount of research,

investigation and consultation was initiated during this period, aimed at better understanding the root causes of poor working conditions. The result

was the mapping of 41 supply chains across the three product category groups.

7

Independent Evaluation of the PPA (2012)

3

Through the direction taken in 2011 which centred on “developing supply chain initiatives aimed at

addressing the root causes of poor working conditions in relation to the specific contexts of those

supply chains” the ETI Secretariat aimed to become a convener and an influencer. Facilitating ETI

membership to collaborate in a collective endeavour to map and scrutinise complex global supply

chains, developing a more comprehensive understanding of why workers’ rights were being abused,

and taking suitable action to address those underlying causes.

The new approach was predicated upon a theoretical ‘change journey’ – that is, a logical – though not

necessarily linear – process involving several stages through which results would be realised. The

first step of this change journey entailed laying the groundwork, an iterative process which would

consist of:

1) Collaborating for change: Identifying the key stakeholders and facilitating collaboration to

develop innovative solutions to labour rights issues across prioritised value chains

2) Understanding root causes: Developing a collective understanding of labour rights abuses

and where the efforts of the ETI have most influence in creating the basis for lasting change

3) Supporting and challenging companies: Facilitating member companies in their efforts

to address complex labour challenges and ensuring that member companies’ activities reflect

the ETI Base Code

Once the foundations had been laid, the ETI would be well-placed to begin enabling change,

through:

1) Sharing lessons learned: Disseminating knowledge and experience gained among

members, policy makers and other key stakeholders, in a bid to enhance the impact of their

ethical trading activities

2) Extending the ETI’s reach: Supporting member companies in endeavours to ‘roll out’

innovative solutions to labour rights abuses across their supply chains

3) Extending Influence: Using accumulated experience to influence policy makers, leverage

funds for transformative action and increase membership

The confluence of the above would then allow the Initiative to begin achieving results, to create a

better working world in which:

1) ETI efforts contribute to workers’ rights being upheld and working conditions improved in

targeted supply chains.

2) Member companies embed responsible business practice into the heart of their operations

3) Policy makers remove the barriers to betting working conditions

4) Workers have the skills, confidence, knowledge and structures to actively shape their

working environments.

1.2. Purpose and Scope of the Evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation is to conduct an independent but participatory assessment of the

progress which the ETI has registered against its vision and theory of change, and to gauge the extent

to which the ETI is organisationally fit to deliver on its new five-year strategy

8

.

8

ETI Perspective 2020: A five-year strategy was approved by the ETI Board in March 2015.

4

Object of the evaluation

The object of the evaluation is the ETI organisation. This is the Membership guided, facilitated and

supported and (at times) led by the Secretariat operating within the direction set by the ETI Board. As

such the evaluation is looking at the collective ability of ETI to support change and deliver impact on

workers conditions.

In conducting the evaluation IOD PARC was also conscious of ETI as; an initiative – a membership

organisation with the ability to initiate things independently. And a catalyst for change – causes or

accelerates a change. Enables or inspires others.

It also recognised that the spread of ETI activity extended beyond the priority supply chain initiatives

to cover joint initiatives born out of more reactive circumstances, forums, members acting

independently, advocacy, accountability, individual member support.

Framing the enquiry

The enquiry was based around the need to offer a credible assessment of:

The impact of the ETI’s work on the lives of workers

The effectiveness of the ETI’s multi-stakeholder process in its global supply-chain work

The efficiency and effectiveness of the ETI’s structures and accountability systems

The adequacy of the ETI’s funding strategy against its budgetary and human resource

requirements to deliver the 2020 strategy.

Throughout the enquiry particular attention was paid to the following sub questions:

To what extent has the ETI’s work enhanced transparency and accountability within supply

chains, and enabled workers to challenge employers over abuse of their rights?

To what extent has the ETI’s work catalysed change in the knowledge, attitudes and

behaviour of those with a direct influence on workers’ lives (employers, industry associations,

governments, trade unions and other worker representatives)?

The conclusions and recommendations of the evaluation will inform the shaping of ETIs operational

plan as it moves within the direction set by the new Strategy.

1.3. The Evaluation Process

The enquiry and analysis of the evaluation was conducted over a four month period from November

2014 culminating in a presentation of major themes and related questions to the ETI Board in March

2015.

Compared with previous ETI impact assessments (2006) and strategic reviews (2010 and 2012), this

evaluation has been a relatively light exercise

9

. Its understanding was significantly deepened,

9

A contract for 15 consultancy days from IOD PARC (Julian Gayfer) with some additional document review and logistical assistance provided

directly by the ETI in the form of a support consultant (Jacqueline Amankwah). Enrique Wedgwood from IOD PARC provided additional research

support to the process.

5

however, by the active involvement in the evaluation process of a tripartite nine person Reference

Group drawn from the ETI’s membership, who helped to frame the detailed enquiry, review emerging

findings and shape the conclusions.

The evaluation process made use of the following tools:

Interviews and interactions with the NGO and Trade Union caucuses, company member

group meetings and the staff of the ETI Secretariat. Some members (including the Chair) of

the ETI Board were also interviewed.

Review of existing ETI documentation and ETI/member monitoring data on the results of the

work of ETI (and its members) and the operating processes of ETI, using the ‘Change

Journey’ (ETI’s theory of change) as a reference point.

Within the interviews and the document review a more detailed look at the supply chain

experience and in particular within this the multi-stakeholder processes of the engagement in

Tamil Nadu on the practice of Sumangali (TNMS) and the engagement with conditions for

workers in the Thai Shrimp industry.

A review of member reporting; the system and examples of member ‘reporting’ trajectory.

A light touch review of documentation and informed opinion on the changing landscape for

the respect of workers’ rights,

An electronic survey (with a high response rate) across the wider ETI membership and

Secretariat staff, not as a means of assessment, but rather as a means of ‘testing’ preliminary

findings elicited from analysis of data solicited from the sources above.

A vital and much valued role in the evaluation process was played by an active Evaluation Reference

Group (drawn from the ETI tripartite membership). Through a series of three meetings aligned to

different stages of the process (November, January & February) the group helped in the framing of

the detailed enquiry, the review of emerging findings and developing the focus for the member survey,

and in the shaping of the conclusions.

Throughout the evaluation process IOD PARC has worked closely with the Knowledge & Learning

Unit of the ETI Secretariat, and through this, linking the evaluation to earlier impact assessments,

strategic reviews (2006, 2010, 2012) and current analysis and reflection undertaken and/or guided by

the Unit.

Through the interviews and in particular within the member caucus and roundtable meetings, the

enquiry sought to gather stories of change observed by members from their broader company

experience and within this bringing out reflections on whether change is happening, the nature and

significance of this change and the role (if any) of ETI processes in influencing this change.

6

2. Setting: ETI within the Broader Landscape

This section looks at the wider landscape for workers’ rights and where and how the work of ETI is

positioned to this bigger picture and dynamic of change.

2.1. Workers’ Rights: Global Trends

A brief overview of global trends regarding the observation of workers’ rights highlights the enduring

relevance of the principles enshrined within the ETI Base Code. It also demonstrates the problematic

nature of evidence and the wider trends that in some cases are likely to be intensifying what is already

a deep rooted problem.

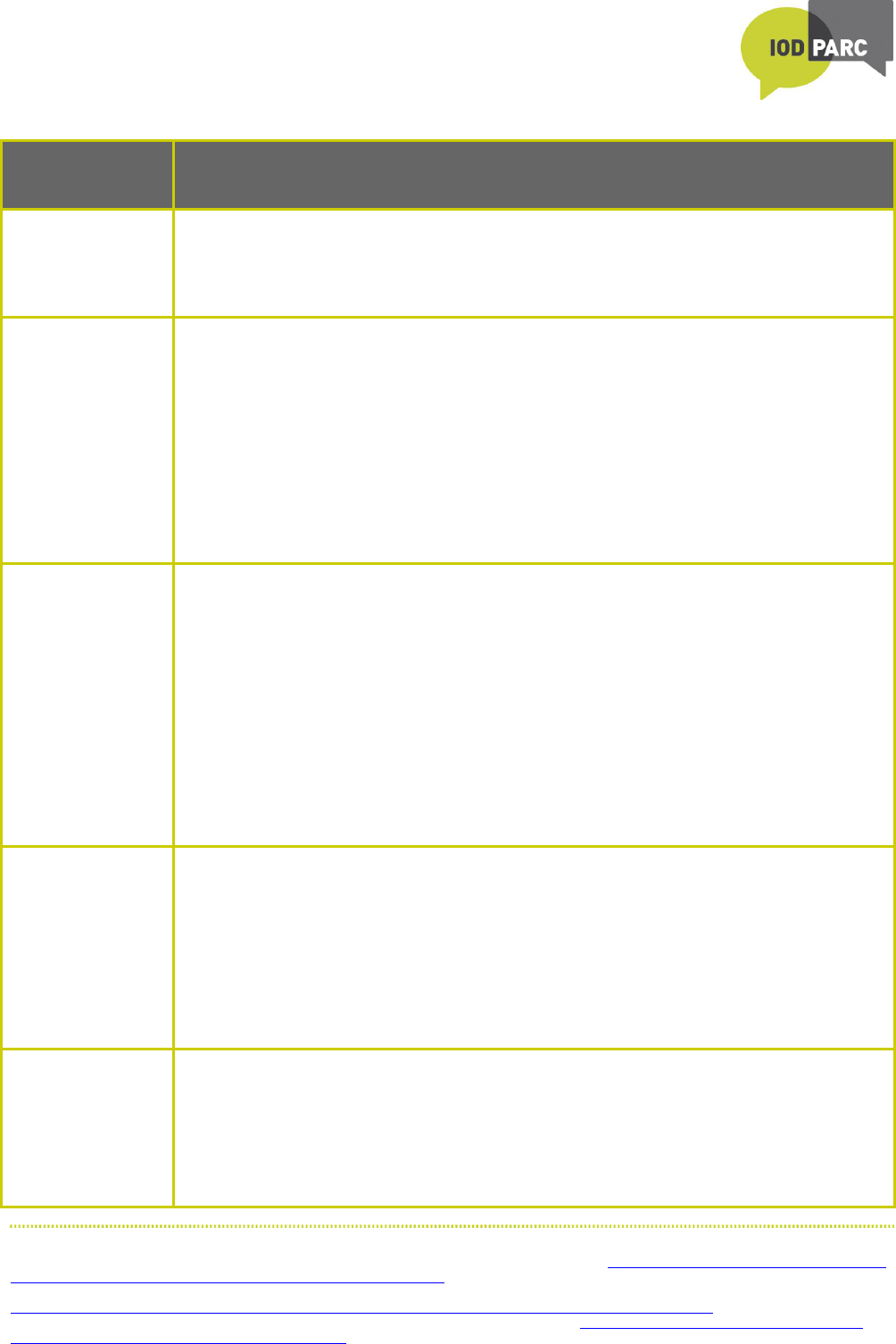

Base Code

Principle

Evidence

Employment is

freely chosen

Measuring the global prevalence of forced labour and contemporary slavery is

problematic, due to the ‘hidden’ nature of the phenomenon, which is often

sustained by opaque criminal networks

10

. ILO data does indicate however that:

Up to 21 million

11

people remain victims of forced labour

Of these, up to 19 million are exploited by private individuals or

enterprises

Forced labour in the private economy generates up to $150 billion in

illegal profits every year

Domestic work, agriculture, construction, manufacturing and

entertainment are among the sectors most concerned.

Migrant workers and indigenous people are among those most vulnerable

to forced labour

12

Freedom of

association and

the right to

collective

bargaining are

respected

The principle international legal instruments on this subject are the ILO’s 1948

“Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention

(No.87)” and the 1949 “Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention

(No. 98)”. The extent to which freedom of association and the right to collective

are respected can be superficially measured by looking at the number of states

that have ratified these core conventions.

To date, a total of 153 countries have ratified Convention 87 and a total of 164

countries have ratified Convention 98

13

. This is out of a total of 185 countries

that are members of the ILO. Ratification, however, does not imply recognition.

It does though imply a legal commitment on behalf of the ratifying state to

10

Walk Free Foundation (2014) The Global Slavery Index 2014, available at: http://d3mj66ag90b5fy.cloudfront.net/wp-

content/uploads/2014/11/Global_Slavery_Index_2014_final_lowres.pdf – accessed 04/02/2015

11

Anti-Slavery International (2015), What is Modern Slavery, available at:

http://www.antislavery.org/english/slavery_today/what_is_modern_slavery.aspx - accessed 02/02 /2015

12

International Labour Organisation (2015) Forced Labour, Human Trafficking and Slavery, available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-

labour/lang--en/index.htm - accessed 04/02/2015

13

International Labour Organisation (2015) International Labour Standards on Freedom of Association, available at:

http://ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/freedom-of-association/lang--en/index.htm - accessed

04/02/2015

7

Base Code

Principle

Evidence

implement the principles stipulated within the respective conventions.

A 2012 report by a committee of experts on the application of conventions noted

with “deep concern that murders of trade union leaders and members continue

to occur in certain countries”, and that “a number of the sectors and groups of

workers excluded from the right to organise and related rights are often

predominately female.”

14

According to the ETI itself, “tens of thousands of

workers lose their jobs every year for attempting to join a trade union.”

15

Working

conditions are

safe and hygienic

Over the past two decades, the ETI has registered several achievements vis-à-vis

this particular principle. Nevertheless, occupational safety remains a key

challenge for workers across the globe.

The ILO has estimated that:

Approximately 2.3 million workers succumb to work related accidents or

diseases every year, which corresponds to roughly 6000 deaths every

day.

Exposure to hazardous substances in the workplace account for

approximately 651,279 deaths per year

16

Child labour

shall not be used

Preventing the use of child labour in supply chains is another area of the Base

Code in which the ETI has registered previous successes.

Globally, the prevalence of child labour does appear to be declining, with the

number of children engaged in labour estimated to have fallen by a third since

the year 2000. However, the ILO estimates that approximately 168 million

children remain in child labour, with more than half of them engaged in

hazardous work.

17

Living wages are

paid

Wages constitute one of the most important indicators for assessing working

conditions. Across the world, many workers receive wages that are barely

sufficient to cover their subsistence needs, let alone those of their families. The

ILO’s 2014-2015 global wage report noted that:

Global wages dropped sharply during the 2008-2009 crisis, and have yet

to rebound to their pre-crisis levels

Global wage growth has been driven largely by emerging and developing

14

International Labour Office (2012) General Survey on the Fundamental Conventions Concerning Rights at Work in Light of the ILO Declaration

on Social Justice for a Fair Globalisation, 2008, pages 36 and 37 – available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---

relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_174846.pdf - accessed 04/02/2015

15

Ethical Trading Initiative (2015) Why We Exist – available at: http://www.ethicaltrade.org/about-eti/why-we-exist - accessed 04/02/2015

16

International Labour Organisation (2011) World Statistic, available at:

http://www.ilo.org/public/english/region/eurpro/moscow/areas/safety/statistic.htm - accessed 04/02/2015

17

International Labour Organisation (2015) Child Labour, available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/child-labour/lang--en/index.htm - accessed

04/02/2015

8

Base Code

Principle

Evidence

economies, where wages are gradually increasing

In the period 1999-2013, real wage growth has lagged behind labour

productivity

18

Working hours

are not excessive

Working hours were the subject of the ILO’s first ever convention; the 1919

“Hours of Work (Industry) Convention” establishing the principle of eight hours

a day and 48 hours a week for the manufacturing sector. This convention was

subsequently supplemented by several others.

Reliable information regarding the extent to which these conventions have been

implemented is hard to come by. A 2007 study for the ILO however, found that

in general, “weekly working hours have been relatively stable for the last ten

years in many countries”, and that in “developing countries, the incidence of

both long and short hours is high”.

19

No

discrimination is

practiced

There are several indications that discrimination against women, migrant

workers and other minorities is widespread in the world of work. A 2011 ILO

report on global working conditions found that:

On average, women’s wages are 70-90% of men’s

Sexual harassment occurs on every continent and across a wide variety

of occupations

In many countries, migrant workers make up 8 to 20 percent of the

labour force, and are often subject to discrimination

Work-related discrimination against people with disabilities is deeply

rooted

Regular

employment is

provided

This principle regards protection against fluctuations in earnings due to

arbitrary job loss. It also covers protection of those engaged in non-standard and

often unpredictable forms of employment such as marginal, part-time work and

temporary agency work among others. The ILO has found that over the past two

decades, the number of people engaged in alternative contractual arrangements

has increased significantly, in both developed and developing countries. In many

cases, this has led to increased ambiguities in the relationship between employer

and employee, and has hampered efforts by workers to assert their rights.

20

No harsh or

inhumane

treatment is

allowed

This principle entails protection against physical, sexual and verbal abuse at the

workplace. There is no systematic source of data regarding the global prevalence

of harsh, inhumane treatment in the workplace. However, harsh treatment is a

concept which cuts across the other eight ETI base code principles, and the

extent to which it occurs can be at least partially gauged from the evidence

provided above.

18

International Labour Organisation (2014) Global Wage Report 2014/2015 Summary, available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---

dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_324839.pdf - accessed 04/02/2015

19

Lee, McCann, Messenger (2007) Working Time Around the World, pg. 61, available at:

http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_104895.pdf – accessed 04/02/2015

20

International Labour Organisation (2015) Non-Standard Forms of Employment, available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/employment-

security/non-standard-employment/lang--en/index.htm - accessed 04/02 /2015

9

2.2. Initiatives Similar to ETI

There is a diverse plethora of organisations ostensibly geared towards improving the conditions of

workers’ around the world. Examples of such organisations include the Fair Labour Association,

BSCI, the Better Work Programme and Social Accountability International. The plurality of

organisations dedicated to enhancing working conditions presents both opportunities and challenges

for ETI. It suggests an abundance of both commitment and expertise, which if properly harnessed and

coordinated, could be directed towards affecting meaningful changes in working conditions around

the world. Although most Codes are based on ILO Conventions, there is the risk of confusing

suppliers with competing compliance requirements and possible duplication of efforts. This may have

direct implications for the ETI, in that the ‘Base Code’ and its attention to tackling root causes to poor

working conditions/ workers’ rights may become ‘lost in the crowd’.

In addition, there are 15 materials sustainability indices (MSIs), which are essentially large databases

of suppliers, and the standards (ethical, environmental or otherwise) which they purport to uphold, as

well as their actual record of compliance against those standards. Of these indices, six are sector

specific, 11 are membership-based and nine promulgate labour codes. MSIs have the potential to

constitute a valuable tool that companies can use to assess the ‘sustainability’ of their supplies, and

ultimately to help inform investment and/or sourcing decisions. Some of the ETI’s membership

indicated in their annual reports that they made use of MSIs in their ethical trade activities. The

potential utility of the MSIs, and the fact that some companies are already taking advantage of them,

merits their further investigation by the ETI in order to identify opportunities for incorporating them

into future programmes.

A ‘market analysis’ recently conducted by the Membership Services Unit of the ETI Secretariat of

organisations engaged in the ethical trade agenda found that the ETI was the only organisation which

provided for a comprehensive annual reporting process, supplemented by “structured matrix-based

feedback and advice on improvement pathways towards best practice”. It further found that across

the landscape, the ETI dealt with the greatest range of issues, and was the organisation that was most

‘collaborative’ in its programmes.

The ‘landscape’ of organisations involved in ethical trade is diverse and not fully formed or developed.

In this context ETI is well positioned – drawing on its unique tripartite nature - to adopt a leadership

role, and contribute to bringing some coherence, direction and clarity on the multiplicity of efforts

aimed at improving working conditions around the globe.

2.3. The Role of the ‘Private Sector’ in Development, the UNGPs and ETI

The private sector’s profile in the development agenda has grown enormously over the past decade,

with some enthusiasts portraying it as the engine of development and prosperity; a panacea for all the

difficulties and challenges faced by the world’s poor. The UK government, for example, has recently

declared its commitment to placing the private sector “centre stage” in its efforts to generate

“opportunity and prosperity for poor people in developing countries.”

21

This approach envisions transforming business environments by reducing costs, lowering legislative

and regulatory barriers and promoting other conditions that will enable the private sector to thrive.

Historical development experience suggests that for the assumption to hold that ‘development’ is an

automatic corollary of a thriving private sector requires that governments create an enabling

21

DFID (2011) The Engine of Development: The Private Sector and Prosperity for Poor People, Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67490/Private-sector-approach-paper-May2011.pdf - accessed

10/02/ 2015

10

environment that supports legal protection for workers, education and health, good governance and

infrastructure; and a critical role for civil society in checking the occasional excesses of the private

sector to ensuring that the benefits of thriving business are distributed amongst the wider population

with a degree of equity. The inherent complexities of a development approach focused on private-

sector led growth have been acknowledged by the United Kingdom’s aid watchdog, the Independent

Commission for Aid Impact, which noted in 2014 that “references to ‘the miracles’ that companies are

able to perform risks underplaying the role that donors like DFID and country governments have in

ensuring that economic development provides benefits to the poorest in society.”

22

Notwithstanding the above there can be little doubt that the private sector does have a critical role to

play in development. The International Finance Corporation, for example, points out that:

“The private sector is responsible for around 90% of employment in the developing world –

including both formal and informal jobs – it provides critical goods and services; is the source

of good tax revenue; and is key to ensuring the efficient flow of capital.”

23

The most sustainable approaches to development are ‘holistic’ in nature – embracing the dynamism

and energy of the private sector, the duty of government to foster environments conducive to the

success of business and the protection of rights, and the oversight of civil society and representative

trade unions. Such an approach is given substance by the tripartite nature of the ETI, as well as by

the Protect, Respect and Remedy framework as articulated by the United Nations Guiding

Principles (UNGPs) on business and human rights.

The UNGPs on human rights and business – also known as the ‘Ruggie Principles’, after their

progenitor John Ruggie - were first articulated in 2008. It is important to point out that the

principles are not formal legal obligations. Rather, they attempt to establish another “common global

standard for preventing and addressing the adverse human rights impact of business activity

24

”. The

principles rest upon the following three ‘pillars’:

States have a duty to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including

business enterprises, through appropriate policies, regulation and adjudication.

Businesses have a corporate responsibility to respect human rights, meaning that they must

act with due diligence to avoid violating the rights of others. They are responsible for

respecting human rights within their own establishments as well as those linked to services

arising from their business relationships.

Both judicial and non-judicial mechanisms need to be established to allow for greater access

to remedy for the victims of business-related abuse.

These principles complement the ETI’s vision. They are of particular relevance insofar as they

recognise the crucial role of governments in protecting the rights of workers within their jurisdiction,

which entails establishing and enforcing conducive legal frameworks in both ‘producing’ and

‘consuming’ countries. While governments in ‘consuming’ countries should establish regulations

controlling ‘their corporations’ activities abroad’, governments in ‘producing countries’ have a

responsibility to enact and enforce legislative frameworks which protect working conditions within

their own territories.

22

Guardian (2014) Aid Watchdog Lambasts UK Focus on ‘Miracle’ Private Sector, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/global-

development/2014/may/15/uk-watchdog-aid-private-sector-development - accessed 10/02/2015

23

IFC (2015) The Role of the Private Sector in Poverty Reduction, available at:

http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/idg_home/ifc_and_poverty_role_private_sector - accessed

10/02/2015

24

Advocates for International Development (2011) John Ruggie’s The Guiding Principles: A Legal Guide to ‘The Guiding Principles’ on Business and

Human Rights, available at: http://a4id.org/sites/default/files/user/Microsoft%20Word%20-%20Legal%20Guide%20-

%20John%20Ruggies%20Guiding%20Principles.pdf – accessed 09/02/2015

11

Nevertheless, it is important to note that these principles have been the subject of some criticism. In

particular, it has been argued that “the principles set a minimal-expectation bar for businesses,

promulgating a series of non-binding, lowest common denominator recommendations that arguably

neglect a more complex reality.”

25

There is also concern that for many companies the default

response to the due diligence challenge of the principles will be to contract out an auditing exercise

(the numbers) with minimal reflection internally on how the company operations within the supply

chain can interact in way that impacts positively on the lives of workers and in doing so identifies and

addresses endemic issues that persist.

An important part of the context is the relatively limited resources of the trade union members –

globally, regionally and nationally. Going forward it will be important for ETI to have an informed

position on the resource needs of their union partners and what needs to happen to meet those needs

if union members and their partners are to be able to optimally respond to the demands and

opportunities that ETI’s existence presents.

2.4. ETI – the 2015-2020 Five Year Strategy

The Goal of the new Strategy is that by 2020 ETI wants to see that the 10 million workers in ETI

company members’ global supply chains enjoy improved protection of the rights described in the ETI

Base Code, greater respect of these rights by those they work for and better access to remedy when the

rights are abused.

To reach this goal the ETI will concentrate its efforts on five strategic pillars from 2015 to 2020:

1) Lead in the application of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human

Rights (UNGPs) in the area of workers’ rights: Mainstreaming the ‘Protect, Respect

and Remedy’ principles into ETI programming will supplement the promotion and

implementation of the Base Code. The ETI plans to avail practical guidance to its members on

implementing the UNGPs, and will undertake independent impact assessments of selected

initiatives in order to generate knowledge and learning, which will be disseminated amongst

the membership base and beyond. This will enable the ETI to “contribute to a global body of

knowledge by sharing the results of practical application.”

2) Ensure workers are represented: This represents a commitment to placing workers at

the centre of ethical trade by encouraging respect for freedom of association and collective

bargaining. The ETI will engage with trade unions so that the workers’ voices will become

integral to the process of identifying problems and risks, and developing sustainable solutions

to issues which affect them directly. It is anticipated that the Initiative will work to develop a

model of worker-management dialogue in the garment sector which can be replicated across

other sectors.

3) Support an emerging international network of local ethical trade platforms: This

involves developing and supporting local tripartite structures in key sourcing countries. These

will be equipped to collaboratively approach local challenges with local solutions and

knowledge, so that interventions are suitably adapted to regional variations in socioeconomic

and political circumstances. Local tripartite structures will be physically ‘closer’ to where

workers’ rights issues are found which will open up possibilities for beneficiary participation

25

Blitt, R. (no date) Beyond Ruggie’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Charting an Embracive Approach to Corporate Human

Rights Compliance ; Texas International Law Journal, Volume 48, Issue 1, Page. 36, available at:

http://www.tilj.org/content/journal/48/num1/Blitt33.pdf - accessed 09/02/2015

12

in the design of interventions. The ETI anticipates that by the year 2020, they will have

supported the establishment of at least three local “ethical trading hubs” in key sourcing

countries.

4) Increase accountability: The ETI has acknowledged the need to encourage its member

companies to be more transparent about working conditions in their supply chains. To

support heightened accountability, the ETI will regularly publish and disseminate policies,

objectives and lessons from past interventions among its membership, and will maintain the

requirement that corporate members produce concise annual reports on labour rights risks in

their supply chains, and the steps that they have taken to mitigate these risks and implement

the Base Code. Crucially, by 2020 ETI member companies will have demonstrated the

business case for heightened transparency in supply chains, so that compliance to the Base

Code becomes both an ethical and commercial imperative.

5) Influence policy and practice: Working with policy makers to establish and enforce

regulatory frameworks geared towards the protection of workers’ rights represents a

development of the ETI’s previous approach, and a welcome expansion of the ‘tripartite’

structure of the organisation to capture the crucial role of government. By 2020, the ETI hopes

to have “demonstrated and documented the value of policy level engagement in at least three

areas.”

In addition to the above ‘pillars’, the ETI has outlined four strategic ‘enablers’ crucial to realising

impact. These include further efforts to foster strategic alliances between companies, trade unions

and NGOs, developing partnerships with like-minded organisations, enhancing organisational

governance through representation and leadership, and establishing a sustainable business model

which will complement membership fees with the ETI’s own income generation, direct funding for

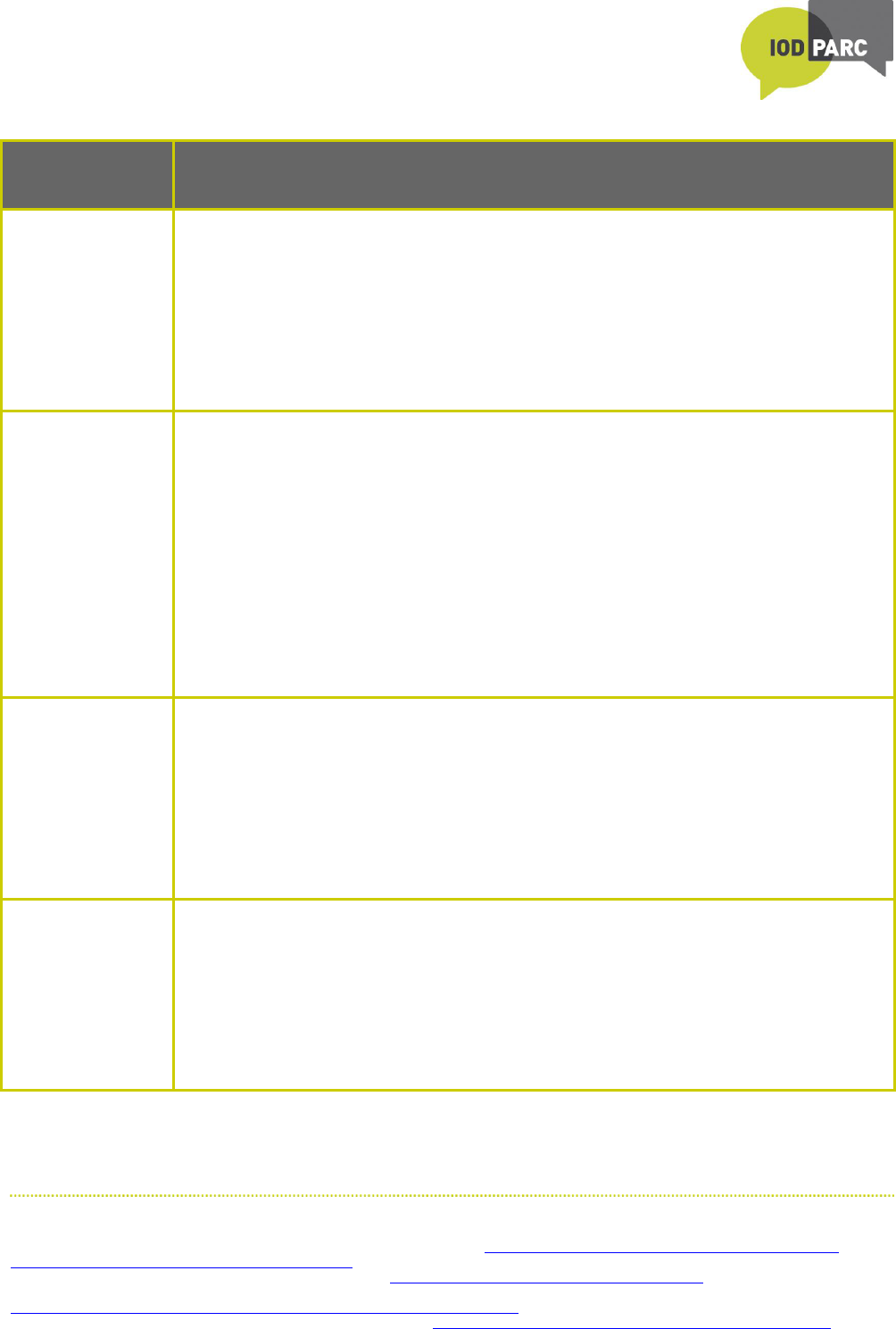

project activity and third party donor funding. Figure 1 overleaf provides a diagrammatic

representation of the 2020 strategy which reflects ETI continuing to look to move beyond an audit

and compliance approach (with its well understood limitations) to advancing the conditions for

workers’ rights.

The new strategy is ambitious at its core lies the aim for ETI to be:

Recognised as a global leader in supporting workers’ rights through implementation of the

ETI Base Code and the practical application of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and

Human Rights.

Successful in promoting genuine worker representation, improving accountability and

advocating for an environment that supports workers’ rights

13

Laying the Groundwork

• Collaborating for Change

• Understanding Root Causes

• Supporting & Challenging Companies

Key Strategic Pillars

• Creating a global network: creating local tripartite alliances

and structures in key producing countries so that decisions

are made ‘closer to the ground’ and interventions are suitably

tailored to local conditions.

• Increasing accountability: increasing transparency by fully

mapping priority supply chains and identifying abuses of

workers’ rights.

• Amplifying workers’ voices: ensuring that workers

participate in the process of mapping supply chains and

identifying issues within them.

Enabling Change

• Sharing lessons learned

• Extending the ETI’s reach

• Extending influence

Key Strategic Pillars

• Increasing accountability: Moving beyond approach based on

self-assessment and intermittent auditing, and developing

and communicating new incentives among member

companies to heighten transparency within supply chains.

• Influencing policy and practice: Recognising the crucial role

that governments must play in delineating and protecting

workers’ rights, and engaging them to that effect.

• Amplifying workers’ voices: Ensuring that workers actively

participate in ETI interventions through constructive

engagement with Trade Unions.

• Supporting local ethical trade networks: Supporting local

tripartite structures in their efforts to improve working

conditions in supply chains, and sharing lessons learned with

a wider, global audience.

• Supporting the application of the UNGPs: raising awareness

among the membership and workers, and providing guidance

and support to companies and governments in their

endeavours to adhere to the principles.

Strategic Enablers

• Effective alliances

• Strategic

Partnerships

• Representation

and leadership

• A sustainable

business model

Achieving Results

• ETI efforts contribute to workers’ rights being upheld and working conditions being improved in

targeted supply chains

• Member companies embed responsible business practice into the heart of their operations

• Policy makers remove the barriers to better working conditions

• Workers have the skills, confidence, knowledge and structures to actively shape their working

environments

14

3. The Major Findings

This section provides an overview of what the evaluation enquiry has established in terms of the state

of play on ETI results and capabilities as of late 2014/ early 2015. In terms of results it considers the

results emerging on a local scale from the priority supply chain work, the achievements looking across

wider aspects of ETIs recent work and the effectiveness of ETIs multi-stakeholder processes. It also

projects forward to look at how ETIs current configuration of work and pattern of results sits against

the longer term aim of achieving a wider impact and in particular the fundamental base code element

of freedom of association. In respect to capabilities this section provides an overview of the efficiency

and effectiveness of the ETI’s structures and accountability systems, including member reporting and

the adequacy of the ETI’s funding strategy against its budgetary and human resource requirements to

deliver the 2020 strategy.

The nature of data available for assessing ETI results

The extent to which it is possible to assess the results of the ETI’s programmes on working conditions

is influenced by the quantity and quality of available data. The data utilised for this assessment was

drawn from four sources:

ETI reporting: These included, but were not limited to: annual reports submitted by the

ETI to DFID under the PPA support (see below), previous evaluations of the ETI, internally

research documents, minutes from stakeholder meetings, strategy documents and publicly

available material.

PPA results architecture: In 2011, the ETI entered into a programme partnership

arrangement (PPA) with the Department for International Development (DFID). One

consequence of this was the dominance of a reporting framework which allows for a

relatively detached assessment of the impact of the various activities encompassed by the

programme. This reporting framework consists of a number of quantifiable indicators and

targets, which are tracked/measured annually, and can be used as a basis for assessing

change.

Membership reporting framework: The ETI Secretariat requires its corporate members to

submit annual reports on their ethical trading activities. These reports are constructed

around pre-defined management benchmarks and key performance indicators, and to

some extent, they constitute a monitoring and evaluation framework in and of themselves.

At the very least, they provide a vast ‘reservoir’ of data which could, in theory, be

scrutinised as a means of assessing results in terms of the impact of member organisations

on the lives of workers in their supply chains.

Interviews: Information on results obtained from the sources identified above was

augmented by and substantiated through interviews with individuals from the ETI’s

tripartite membership, as well as interviews with members of the ETI Secretariat.

15

3.1. ETI Results

It is clear that the ETI’s innovative tripartite approach works. This is attested to by indications of

qualitative improvements in labour conditions achieved across a variety of sectors and within several

national settings and through different entry points.

Changing worker conditions through Supply chain initiatives

Many of these initiatives have been running for a number of years. For example work in Morocco on

strawberry production and with homeworkers in the garment industry in northern India. The

experience of the priority supply chain initiatives has contributed to those actively involved ETI

members getting a better understanding of the challenges within a specific supply chain. For example

the process within the Rajasthan Sandstone Working Group was successful in developing

collaborative programmes for sandstone sourced from Rajasthan. This involved ETI members

“carrying out extensive mapping exercises of their Rajasthan sandstone supply chains, providing a

rich picture of the nature of the industry, the key challenges for workers” and the areas in which the

ETI was best placed to exert its influence.

In Tamil Nadu and the Sumangali labour practice it has taken three years for ETI working through its

tripartite approach to develop a full understanding of the local situation including the key

relationships within a complex issue. Whilst frustratingly slow this has built up some trust in areas

where previously there was distance and antipathy. Whether this new set of relationships and the

emerging local ETI platform supported by a south Indian based team, can now be leveraged in ways

that can ultimately lead to a systemic change within the mill operations remains untested. There is a

concern that the slow burn ‘project’ nature of such ETI sponsored initiatives (coupled with the

associated uncertainties of continued funding and of a predominant development project working

style) has led to a position where the sense of ownership – for the PSCs - is often more strongly held

by the Secretariat (matched by a strong focus of attention from NGO members) than by the member

companies and trade unions.

The above illustrations of change coupled with other findings on ETI results suggest that the basic

theory of the ETI’s change journey is valid, although results directly affecting the lives of workers are

to date largely limited to the more ‘visible’ (and readily accessible) aspects of the Base Code such as

child labour and health/safety.

The Table below draws on available results information held within the ETI reporting framework for

the PPA that ETI entered with the Department for International Development (DFID) in 2011

documentation. The figures also illustrate some of the inherent problems and continuing challenge of

capturing, interpreting and communicating the results of ETI’s work.

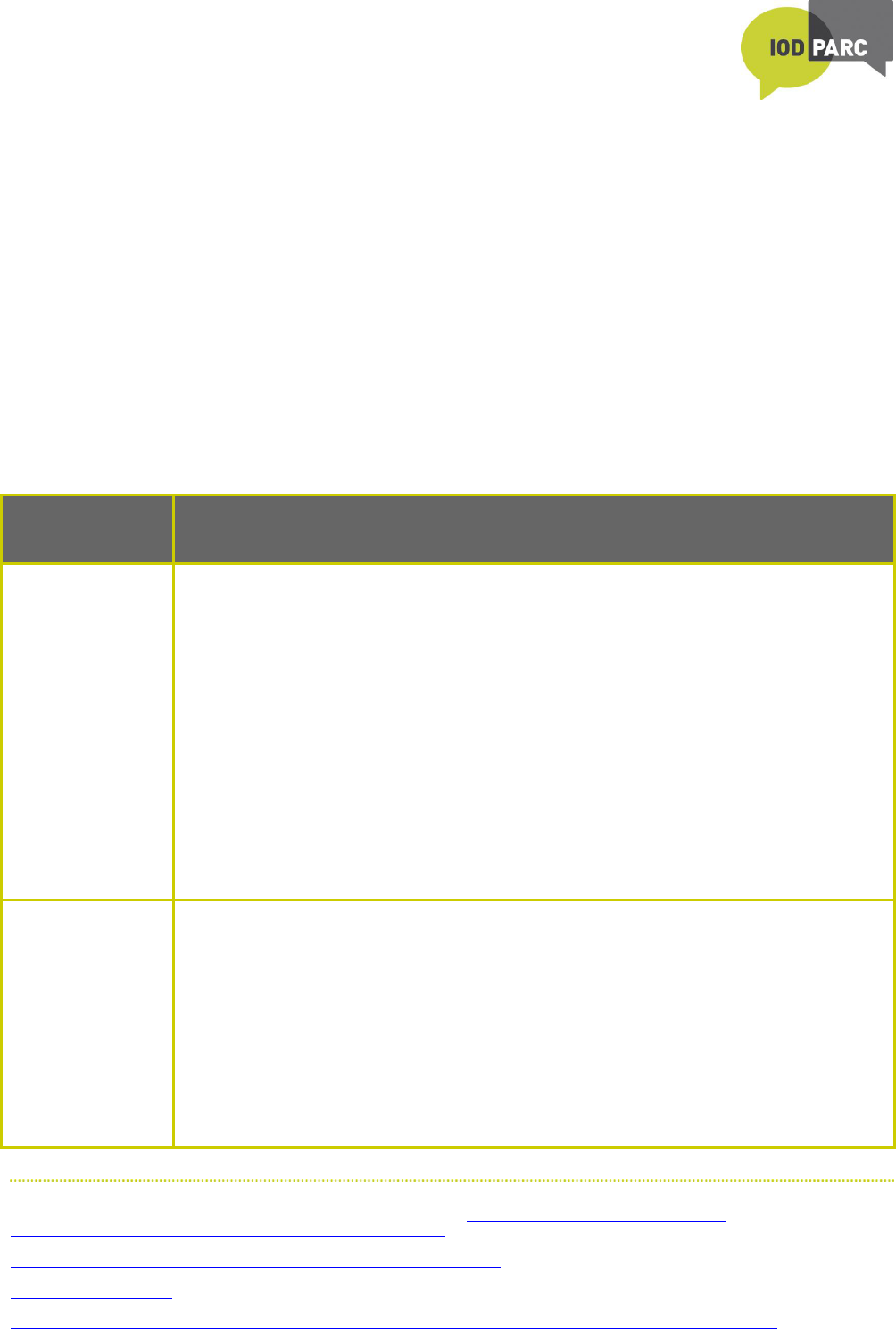

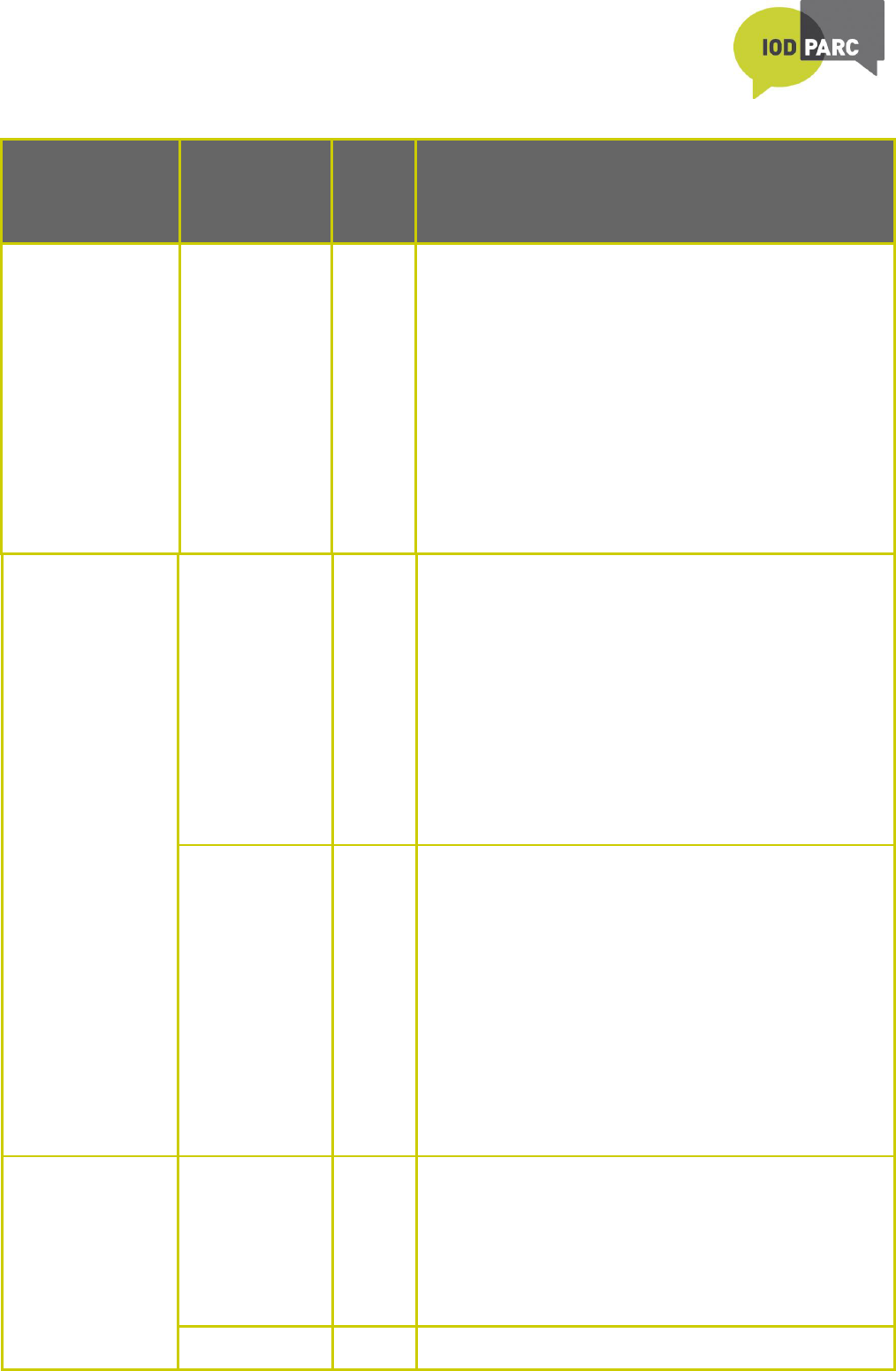

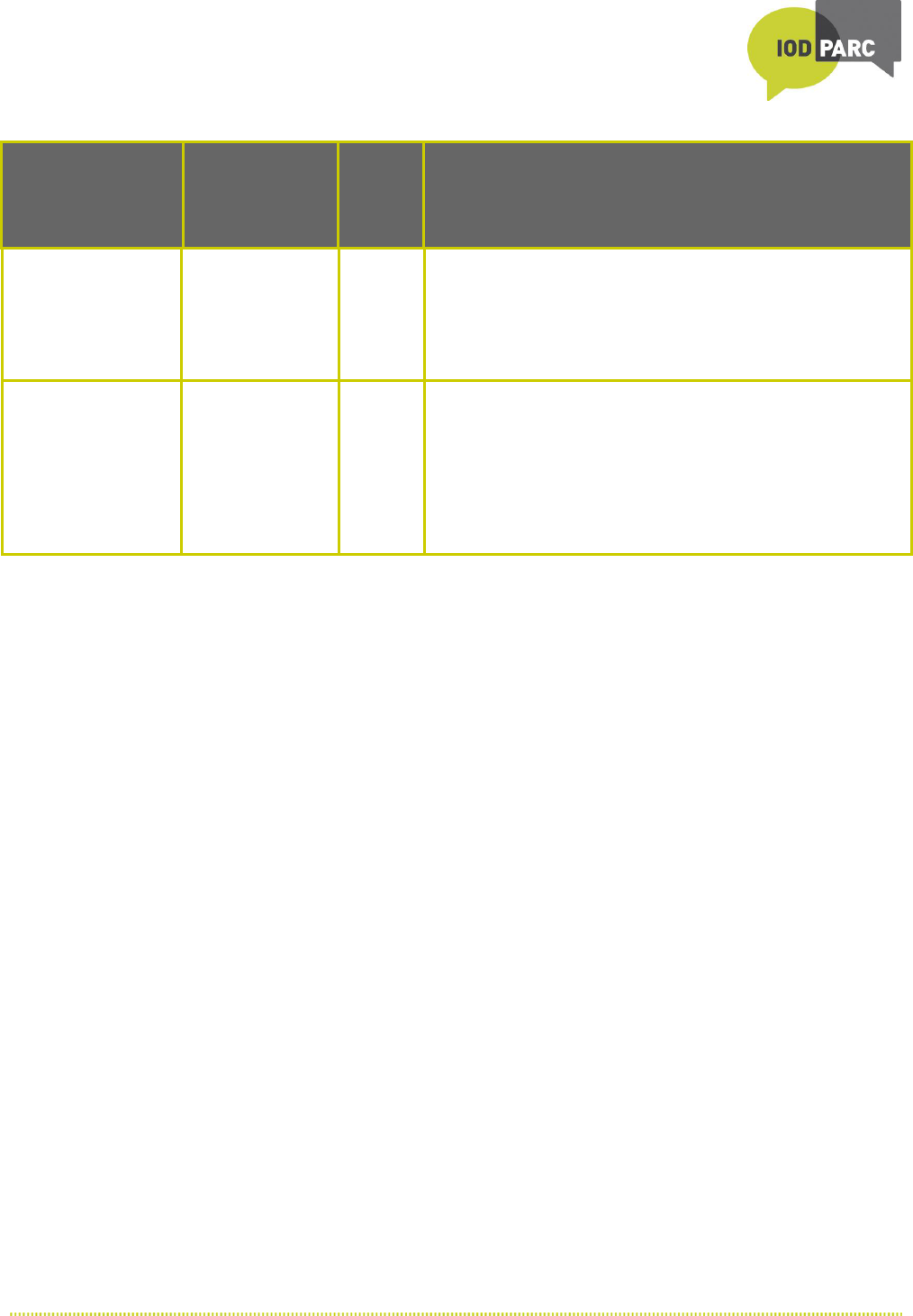

Table 1: Illustration of Results Achieved

Evidence within

ETIs work of

Indicator

Target

/

Result

(Yr 3)

Progress Assessment

Fostering

partnerships to

tackle labour rights

issues

Finding innovative

solutions to labour

rights issues arising

from companies,

Trade Unions and

NGOs collaborating

Number of joint

programme

initiatives in

selected

workplaces

addressing a

specific workers’

condition as

described in the

ETI base code.

30/ 34

Whilst the targets for these indicators have been exceeded,

the impact of ‘joint initiatives’ remains unclear. It is

evident that the basis for dialogue has been established.

However, it is not possible to ascertain the extent to which

this has been translated into action. The results registered

against indicator 2 are ambiguous – it is not clear how the

ETI has succeeded in encouraging ‘active participation’ in

joint initiatives beyond its membership base. Additionally,

the concept of ‘active participation’ remains open to

interpretation, because it does not specify the extent or

impact of ‘participation’. Furthermore, the concept of

16

Evidence within

ETIs work of

Indicator

Target

/

Result

(Yr 3)

Progress Assessment

together

ETI brokering

agreements in

disputes and crisis

situation

Number of

organisations

actively

participating in

selected

workplaces

[PSC?] in joint

programme

initiatives.

300/

501

collaboration does not seem to encompass the crucial role

of government in establishing a conducive legislative

environment for improvements in working conditions.

% of

improvement

actions in

prioritised

supply chains in

which workers

independently

report positive

change

85%/

79%

The PPA annual report for 2013/14 highlights challenges

encountered in collecting data against this indicator. Data

here appears to have been collected from three

programmes: “South Africa Supervisor Training”,

“Moroccan Strawberries” and the “RAGS Programme”.

Therefore it does not provide a particularly broad insight

into results registered in this outcome area. The report

acknowledges that “correlating improvement actions with

workers reporting change” is not always feasible, because

“capturing reliable data on independent worker reporting

is complex”. Bearing this in mind, ETI has agreed with

DFID that it will also use ‘outcome mapping’ as a means

through which progress in this outcome area can be

assessed.

25,000 workers,

especially

women, enjoy

improvement in

one or more of

the rights

described in the

ETI Base Code

25,000/

367,145

The target for this indicator has been exceeded

considerably. However, 345,949 of the workers ‘enjoying

improvements’ can be found in only one value chain –

Bangladeshi garments – and can attribute improvements

to only one joint initiative – the ‘Bangladesh Accord on

Fire and Building Safety’. The PPA report for 2013/2014

acknowledges that “this response to an unforeseen

disaster explains why we have so dramatically exceeded

our target”. If the Bangladeshi garment supply chain is

ignored, then the actual number of workers enjoying

improvements in their Base Code rights is just 12,775. This

is not to diminish the considerable achievements

registered because of the Bangladesh accord. However,

performance in this outcome area needs to be seen in its

proper context.

Poor and

vulnerable workers

in prioritised

supply chains are

better prepared to

act on their rights

Number of

workers

reporting

knowledge of

their rights at

work

disaggregated by

gender

40,000

/ 84,317

Drawn from company member reports

Number of

workplaces with

130/

Drawn from company member reports

17

Evidence within

ETIs work of

Indicator

Target

/

Result

(Yr 3)

Progress Assessment

mechanisms in

place through

which workers

can voice their

workplace

concerns

161

ETI members

operate in a way

that supports

improvements in

working conditions

in prioritised

supply chains

Number of

changes in

business

practices

adopted by

businesses that

affect prioritised

supply chains

40/ 49

Drawn from company member reports

Policy development and change

ETI has often proven to be an effective actor in the policy space and there are notable examples both

in the UK and beyond of where the ETI has brought something distinctive and significant to the

staging and content of policy level dialogue. For example: the work in Cambodia on conditions within

the garment industry; facilitating the Bangladesh Accords

1

in response to the Rana Plaza disaster

which shed light on poor health and safety conditions within the Bangladesh garment supply chains

and resulted in several positive transformations, including compensation to thousands of bereaved

relatives, frequent factory inspections, and factories deemed unsafe being closed or repaired; the

effective lobbying of government and parliamentarians by ETI members and the Secretariat on the

UK Gangmasters Licencing Authority Legislation and the Modern Slavery Bill. In such cases the ETI

Secretariat has often demonstrated leadership – often in an understated and behind the scenes way –

and in some cases forming a position around which members have effectively rallied.

The above cases illustrate the effective way in which ETI can engage with government who play a

critical role in delivering on workers’ rights. That said the government dimension has hitherto been

comparatively overlooked by the work of ETI. Going forward to engage more strongly in this area will

require a Secretariat sufficiently resourced with access points, credibility with government and the

expertise to engage.

Developing and strengthening the company business case for ethical trade

Defining and communicating the ‘benefits of ETI membership’ in terms of a member organisations

having a business case to fully invest in the practice of ethical trade remains a weak area. The

imperative of this for sustainable change is acknowledged on the ETI website - “ETI members have

found that the most powerful tool for persuading senior management, staff and suppliers to take

ethical trade seriously is to set out the business benefits as well as the moral imperative.”

ETI members are active, both individually and with other tripartite members, outside of the priority

supply chains and in doing so are providing test beds for their business case for ethical trade. It is this

1

The signing of the ‘Bangladesh Accord’ to which over 170 companies have subscribed.

18

organisational experience that reflects the wider reach of ETIs work and going forward offers an

important channel for reflection and learning.

The interviews surfaced a number of instances where member companies have been taking significant

steps in terms of member company policy and practice on ethical trade; including structural changes

to infuse ethical trade considerations into their sourcing and business practice. The new strategic

reporting approach for the ‘leaders and achievers’ allied with good feedback from the Secretariat and

related dialogue on the company position should prove a rich source of experience and provide a

positive momentum on the moves to a business case, and a lens to capture, report and learn from this.

Such gains are in parallel to the achievements in workers conditions captured within the priority

supply chain work outlined above, and ultimately from an impact perspective are potentially of

greater significance.

The evaluation member survey revealed five main obstacles to member companies addressing ethical

trade more robustly within their organisation. This included three that can be construed as resulting

from the lack of a convincing business case for ethical trade; (i) competing commercial resources, (ii)

insufficient staff resources (staff capacity), (iii) short-term thinking regarding planning and budgeting

cycles. Almost a quarter of respondents indicated that their company had not developed a clear

business case for ethical trade. Furthermore of the 70% who have developed a business case for

ethical trade only just over half have financially quantified it.

The ETI continues to provide a critical and valued ‘safe space’ for dialogue between partners on

understanding and jointly exploring and addressing challenging and in particular new issues relating

to ethical trade. Over 80 percent of respondents to the survey that was carried out as part of this

evaluation expressed agreement with this finding. The tripartite dialogue experience with the

associated exposure and access to peers this provides for members, is an important contributor to

improvements in members’ ethical trade practice. This includes early exposure and information on

emerging issues and helping to drive positive organisational changes that reinforce this.

Professional capacity of members on ethical trade being built

In addition to the ‘exposure’ value to issues that ETI members benefit from the training and capacity

building activities led and largely serviced by the ETI Secretariat are valued by the membership (e.g.

training on ‘worker voice’). ETI remains well positioned to deliver professional training on the issues

and potential solutions relating to root causes affecting workers’ rights, through bringing an

understanding of the complexity of the situation and what the requisite multi-stakeholder solutions

will demand.

The ETI continues to provide a valuable forum for the sharing of members’ wider experience and for.

Efforts continue to be made to foster a stronger climate of sharing on learning between members on

their own general experiences. This could be usefully extended to include their experiences in

embedding and infusing ethical trade policy and practice within their organisational structure and

business operating systems and the effects thereof.

3.2. The Effectiveness of ETI’s Multi-stakeholder Processes

The process of formulating approaches tailored to improving working conditions in selected supply

chains has been protracted, and this led to frustration and at times a perception of stagnation across

the ETI’s membership. However, delays in formulating a context specific approach were attributed

primarily to an appreciation of the need to adopt a ‘measured approach’ in which all the relevant

stakeholders are brought together to develop consensus – a process which is complicated, sensitive

and time consuming, but entirely necessary where systemic issues are being targeted.

Despite the general sense of positive movement – some early results towards the prospect of positive

outcomes - within many of the priority supply chain initiatives, challenges to laying the groundwork

19

for change have been encountered. The understandable ‘slow burn’ of laying the groundwork has been

exacerbated by the priority supply chain work proving to be more time-consuming and complex than

anticipated. This is often in contrast to other ETI initiatives – short, sharp and opportunistic

interventions – that have developed faster and more organically, and developed their own natural

momentum such as work with garment workers in Leicester. In both cases gaining a sufficient

understanding of local dynamics, movers and shakers has been a critical step facilitated by ETI

Secretariat.

There has to date been limited learning generated from the study field of the multi-stakeholder

processes within the priority supply chain work and such learning is perceived as relatively small in

relation to the amount of effort, time and resources expended. Moreover whilst important progress

has been made within the supply chain work the communication of this to member has often not been

sufficient and this has helped to feed a sense of frustration and a perception of stagnation.

3.3. Achieving Impact

There is a multiplicity of factors involved in bringing change to workers conditions - as recognised by

ETIs Theory of change - and determining and attributing the impact of ETIs work will always remain

challenging. Notwithstanding the above the basis for gauging ETIs impact as a membership

organisation is constrained by the lack of a coherent, overarching and rounded ‘results framework’

reflecting the totality of what ETI does – its different entry points – and reflective of the multiple

paths to impact on workers conditions in the landscape that ETI inhabits. To date the priority supply

chain initiatives have – through the DFID PPA – been a significant reference point for gauging and

reporting on ETIs impact.

ETI members are active, both individually and with other tripartite members, outside of the priority

supply chains and in doing so are providing test beds for their business case for ethical trade. It is this

organisational experience that reflects the wider reach of the ETI’s work and offers an important

channel for reflection and learning. ETI engagement can help member companies (and involved trade

union and NGO partners) extend the scope of such work – pushing on and up-scaling – from the

‘short term project’ approach that is often characteristic of member interventions working with

external consultants. This will be an increasingly important channel for achieving impact.

The key issue of freedom of association when looking at impact

Member companies openly acknowledging the constraints and limitations of audit and compliance-

based approaches to advancing ethical trade within their own working environments. Members

recognise that to make significant advances on workers conditions aspects such as purchasing

practices and weak trade unions and other forms of association (which members struggle to singularly

address themselves) need to be more purposefully addressed – within the bounds of what ETI can

realistically do on such issues. Over 70 percent of respondents to the survey distributed for this

evaluation agreed that promoting freedom of association was the most sustainable means to

promoting positive change in working conditions within supply chains.

This viewpoint, which portrays member companies as the primary ‘agents of change’, underscores

central contradiction facing the ETI: that its tripartite nature is at once its greatest strength and its

key weakness. On the one hand, the initiative’s tripartite structure holds the potential to promote a

broad and inclusive debate on the issues with which the membership collectively grapples and to

prioritising within this such as with freedom of association. On the other hand, the tripartite structure

necessarily implies conflicting objectives and incentives, which if not reconciled, could threaten to

forestall meaningful action. Going forward, a key challenge for the ETI Secretariat will be to transform

this latent conflict of interests into a confluence of interests and action. In looking for more catalytic

ways to engage on this pivotal aspect of the Base Code the level of engagement from trade union

members and their engagement with their affiliates at local level working with suppliers down

through the supply chain will be an increasingly critical area for ETI.

20

3.4. Summary on Results

In summary:

The distinctive and unique ETI tripartite approach works and is valued.

Whilst there is an understandable ‘slow burn’ to much of ETI’s work there is a danger of ETI

being perceived as moving slowly – being in the ‘slow lane’ of achieving change in workers

conditions. This has been exacerbated by the priority supply chain work proving to be more

time-consuming and complex than anticipated. This is in contrast to other ETI supported

initiatives – short sharp opportunistic interventions - that have developed faster and more

organically, and developed their own natural momentum such as work with garment workers

in Leicester.

ETI has not given enough attention to the impediments for freedom of association.

ETI can be and often is an effective actor in the policy space engaging with government and

there is significant scope for enhancing policy level engagement, which by necessity involves

closer dialogue with government.

ETI is a valued source for building professional capacity within members on ethical trade.

ETI’s ability to effect change needs to focus on the level of engagement, support and direct

action by ETI members reinforced and facilitated by the stewardship and activities of the ETI

Secretariat.

3.5. ETI Capabilities: the Reporting Framework

Whilst continually improving the member reporting system is having a less than optimum effect on

helping member companies to improve their business practice on ethical trade. Interviews with

members, Secretariat staff and the independent consultants who up until 2012

2

were previously

involved in the analysis of member annual reporting, coupled with a wider documentation review and

a light touch review of three member companies reporting journeys revealed the following findings.

Overall, the quality of reporting was high, and demonstrated an in-depth understanding of the

multiple issues at stake relating to ethical trade. This was in part due to the coherent reporting

structure required by the ETI. The standard annual reporting tool provided by ETI is built around

“Principles of Implementation”, which “set out the approaches to ethical trade expected of ETI

members

3

”. These principles are substantiated by 29 sub-principles. In an exercise of self-

assessment, a company is asked to determine their level of performance against each principle and

sub-principle of implementation, and assess where they are according to a set of ETI ‘management

benchmarks’: “foundation stage”, “improver”, “achiever” or “leader”. Companies are then given the

opportunity to describe the activities which “support their chosen performance level”. This process is

further bolstered by a set of Key Performance Indicators for each of the Principles of Implementation,

against which companies are required to report. In sum, this format provides a relatively sound basis

for ensuring accountability from members, and tracking progress along the ethical trade agenda.

However, the effectiveness of the process in ensuring accountability and monitoring progress is

limited by the following factors:

2

From 2012 on the assessment of annual reports was brought back in-house to the Secretariat.

3

These seven principles of implementation relate specifically to: Policy, Communication and Advocacy, Resources,

Influencing Suppliers, Strategy, ETI Participation, Collaboration.

21

a. It is challenging to assess the veracity of the information disclosed within the annual report,

which is confidential. The ETI assess and evaluates each member’s report with the input from

NGO members. ETI has aimed for 15% of reporting companies to “receive validation visits

each year in line with ETI’s validation process” but in practice this has been significantly less

and there was a long period between 2012 and 2014 where there were no validation visits.

b. All company reports are shared with “other corporate, trade union and non-government

members of ETI, subject to signature of a confidentiality agreement”. Additionally,

“anonymous information about the performance of ETI’s corporate members will be made

available to the public.” This process enables a fairly high degree of internal transparency,

but only a very limited degree of external transparency.

c. The above point is linked to the fact that the annual reporting process does not really amount

to more than self-assessment, although the evaluation observed that in the case of one

company “we have formed further partnerships with independent 3

rd

party providers to

enhance the skill base of the central CR team, give greater insight into labour issues on the

ground and add an independent element to our assessments. The 3

rd

parties are local NGOs,

independent consultants and internationally known audit firms.”

d. Because the reporting format is limited largely to self-assessment, the quality, depth and

integrity of information provided is likely to vary between member companies. This does not

provide a particularly sound basis for interpreting performance across members, because the

data sources are of varying and uncertain reliability. Whilst evidence gathered by NGO

members involved in the company reporting assessment shows a steady improvement trend

in the reported ethical trade performance of individual ETI company members the process

doesn’t support a sense of peer pressure between company members in respect to the

trajectories of their individual member journey.

In 2014, informed by feedback that the standard process was too arduous, the ETI Secretariat

introduced a new approach to reporting – ‘reporting by exception’ - whereby members only report

when they believe they have moved up a level performance wise/ they have made some progress.

Another change is that as of 2014, members who were classified as ‘achievers’ or ‘leaders’ could opt to

submit an ‘Ethical Trade Strategic Plan’ instead of the standard annual report. This ‘Strategic

reporting Framework’ was finalised in early 2014 and allows members to submit a report on how they

are performing against their strategic plans; a set of tailored objectives, targets and activities to

advance the ethical trade agenda, as well as tools and processes through which progress could be

measured.

Providing ‘achiever’ and ‘leader’ members with the option of submitting a strategic plan instead of the

standard annual report presupposes that the process through which members qualified to be

‘achievers’ and ‘leaders’ was sound. There is fairly good cause to believe that this is the case. Despite

some shortcomings, the standard reporting framework was comprehensive enough to allow for a

sufficient degree of confidence in the accuracy of these classifications.

Overall there are mixed views amongst the membership on the appropriateness (level of complexity,

size) of the reporting system and concerns over the quality, sharpness and timeliness of the feedback

provided on members’ reports by the ETI Secretariat. The reporting framework (both the standard

and the strategic variants) encourages a sense of accountability from member companies – at least in

so far as members are required to submit evidence to substantiate their self-assessment. There is good

cause to believe that members’ – on the whole – approach the exercise with good-will. It is in their

interests to report accurately, and point out shortcomings where they may happen to exist. That said

the reporting system still has a somewhat extractive feel and doesn’t correlate as well as it could to the

reality of the process of member reflection on their own unique journey on ethical trade; charting and

reporting on the immediate steps they are taking, the challenges they are experiencing and how this

translates into proposed actions within their company environment. The partial drive that the

22

reporting process provides to an individual member company setting has been compounded by the

low level of activity on verification visits from ETI which in themselves are seen as important

opportunities for ETI to engage with more senior levels within the member companies.

The potential for the reporting process to drive progress collectively of ETI member companies along

the ethical trade agenda certainly exists. However, it is largely dependent on the ETI Secretariat’s

capacity to draw lessons from the aggregated reports, share those lessons among members and the

broader public, and take a lead role in encouraging action based upon those lessons. ETI struggles to

meaningfully ‘sanction’ poor performance by individual company members. Whether or not the ETI

should aspire to a position in which it has the capacity to inflict sanctions on non-compliant members

is contentious. It was generally felt that it was not the role of the ETI Secretariat to inflict sanctions on

its non-compliant members. That ‘stick’ would be more sustainably wielded by the hands of workers,

their trade unions and their governments. However, it is for the ETI to facilitate its members to hold