EVALUATION OF THE COMPREHENSIVE

PRIMARY CARE INITIATIVE: FOURTH

ANNUAL REPORT

May 2018

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative

Fourth Annual Report

May 2018

Lead authors:

Deborah Peikes

Grace Anglin

Stacy Dale

Erin Fries Taylor

Ann O’Malley

Arkadipta Gosh

Kaylyn Swankoski

Jesse Crosson

Rosalind Keith

Anne Mutti

Sheila Hoag

Pragya Singh

Ha Tu

Thomas Grannemann

Mariel Finucane

Aparajita Zutshi

Lauren Vollmer

Randall Brown

Contributing authors (in alphabetical order):

Patrick Balke

Bryan Bernecker

Karen Bogen

Nancy Clusen

Jared Coopersmith

Annie Doubleday

Nancy Duda

Claire Dye

Michael Fields

Tyler Fisher

Jonathan Gellar

Kristin Geonnotti

Sabitha Gopalsamy

Mary Harrington

Shannon Heitkamp

Tricia Higgins

John Holland

Tessa Huffman

Jasmine Little

Rachel Machta

Nancy McCall

Shira Mitchell

Norberto Morales

Nikkilyn Morrison

Brenda Natzke

Victoria Peebles

Dmitriy Poznyak

Eugene Rich

Brianna Sullivan

Xiaofan Sun

Deker Winsor

Submitted to:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

7500 Security Blvd.

Baltimore, MD 21244-1850

Project Officer: Timothy Day

Contract Number: HHSM-500-2014-00034I\HHSM-500-T0010

Submitted by:

Mathematica Policy Research

P.O. Box 2393

Princeton, NJ 08543-2393

Telephone: (609) 799-3535

Fax: (609) 799-0005

Project Director and Principal Investigator: Deborah Peikes

Deputy Project Director and Principal Investigator: Erin Taylor

Co-Principal Investigators: Stacy Dale and Randall Brown

Reference Number: 50319

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... XVII

1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1

1.1. Overview of the Comprehensive Primary Care initiative .................................................... 1

1.2. Design of the CPC evaluation ............................................................................................. 5

1.3. This report ........................................................................................................................... 7

2. WHO PARTICIPATED IN CPC? ...................................................................................................... 9

2.1. Key takeaways on CPC participation .................................................................................. 9

2.2. Methods ............................................................................................................................ 12

2.3. Participating regions and payers ....................................................................................... 12

2.4. Participating practices and patients .................................................................................. 16

2.4.1 Details on CPC practice withdrawals and terminations ....................................... 19

3. WHAT PAYMENTS, DATA FEEDBACK, AND LEARNING DID CMS AND OTHER

PAYERS PROVIDE TO CPC PRACTICES? ................................................................................. 25

3.1. Key takeaways on CPC supports to practices .................................................................. 25

3.1.1. Payments to CPC practices ................................................................................. 25

3.1.2. Data feedback provided to CPC practices ........................................................... 26

3.1.3. Learning supports provided to CPC practices ..................................................... 27

3.2. Methods ............................................................................................................................ 28

3.3. Payments to CPC practices .............................................................................................. 28

3.3.1. Care management fees from CMS and other payers .......................................... 29

3.3.2. Shared savings payments from CMS and other payers ...................................... 33

3.3.3. Practices’ use of and perspectives on CPC payments ........................................ 39

3.4. Data feedback provided to CPC practices ........................................................................ 41

3.4.1. Data feedback from CMS and other payers ........................................................ 41

3.4.2. Practices’ use of and perspectives on CPC data feedback ................................. 45

3.5. Learning supports provided to CPC practices .................................................................. 50

3.5.1. Learning support from CMS ................................................................................. 50

3.5.2. Learning support from other payers ..................................................................... 59

3.5.3. Practices’ use of and perspectives on CPC learning support .............................. 61

v

CONTENTS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

4. HOW DID CPC PAYERS, PRACTICES, AND OTHER STAKEHOLDERS WORK

TOGETHER? ................................................................................................................................. 65

4.1. Key takeaways on collaboration among CPC payers and other stakeholders ................. 65

4.2. Methods ............................................................................................................................ 66

4.3. CPC collaborative goals and structure.............................................................................. 66

4.4. Results of CPC collaboration ............................................................................................ 68

4.5. Factors influencing CPC collaboration .............................................................................. 70

4.5.1. Collaboration among non-CMS payers ................................................................ 70

4.5.2. Collaboration between CMS and other payers .................................................... 72

4.5.3. Collaboration between non-CMS payers and other stakeholders ....................... 74

5. HOW DID CPC PRACTICES CHANGE THE WAY THEY DELIVERED CARE THROUGH

WORK ON SPECIFIC MILESTONES? .......................................................................................... 75

5.1. Key findings on practices’ changes in care delivery ......................................................... 75

5.2. Milestones and data sources ............................................................................................ 80

5.2.1. Overview of Milestones ........................................................................................ 80

5.2.2. Data sources ........................................................................................................ 81

5.3. Changes over time in CPC practices’ approaches to primary care delivery..................... 82

5.4. Progress on individual Milestones .................................................................................... 88

5.4.1. Milestone 2: Care management for high-risk patients ......................................... 89

5.4.2. Milestone 3: Access and continuity .................................................................... 104

5.4.3. Milestone 4: Patient experience ......................................................................... 109

5.4.4. Milestone 5: Use data to guide quality improvement ......................................... 113

5.4.5. Milestone 6. Care coordination across the medical neighborhood .................... 120

5.4.6. Milestone 7: Shared decision making ................................................................ 124

5.4.7. Milestone 8: Participation in the CPC learning collaborative ............................. 130

5.4.8. Milestone 9: Health IT ........................................................................................ 130

5.5. Monitoring of adequate Milestone achievement ............................................................. 133

5.5.1. Practices that received CAPs for PY2016 Q1–Q3 performance ....................... 134

5.5.2. Patient dismissal ................................................................................................ 135

5.6. Facilitators of and barriers to implementing changes in care delivery across

Milestones and implications for other care delivery initiatives ........................................ 135

5.6.1. Characteristics of the CPC initiative................................................................... 135

5.6.2. CPC practices’ structure and characteristics ..................................................... 136

5.6.3. Practices’ strategies to implement CPC ............................................................ 137

5.6.4. Factors external to CPC practices ..................................................................... 137

vi

CONTENTS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

6. HOW DID CPC AFFECT THE EXPERIENCES OF PHYSICIANS, OTHER CLINICIANS,

AND STAFF? ............................................................................................................................... 143

6.1. Key takeaways on the effect of CPC on physician, other clinician, and staff

experience ....................................................................................................................... 143

6.2. Methods .......................................................................................................................... 144

6.2.1. Survey content and measures ........................................................................... 144

6.2.3. Survey administration ........................................................................................ 148

6.2.4. Survey sample and response rates ................................................................... 149

6.2.5. Analysis .............................................................................................................. 150

6.3. Findings ........................................................................................................................... 152

6.3.1. Burnout ............................................................................................................... 152

6.3.2. Control over work ............................................................................................... 157

6.3.3. Alignment of work with training .......................................................................... 160

6.3.4. Satisfaction with work ........................................................................................ 163

6.3.5. Ratings of CPC in 2016 among CPC practice members ................................... 165

6.4. Discussion ....................................................................................................................... 169

7. HOW DID CPC AFFECT THE EXPERIENCES OF MEDICARE FFS BENEFICIARIES? .......... 171

7.1. Key takeaways on the effect of CPC on the experiences of Medicare

beneficiaries .................................................................................................................... 171

7.2. Methods .......................................................................................................................... 172

7.2.1. Survey content and measures ........................................................................... 172

7.2.2. Survey administration ........................................................................................ 173

7.2.3. Survey sample and response rates ................................................................... 174

7.2.4. Analysis .............................................................................................................. 175

7.3. Results ............................................................................................................................ 176

7.3.1. Composite measures ......................................................................................... 176

7.3.2. Individual questions not in the composite measures ......................................... 180

7.4. Discussion ....................................................................................................................... 185

8. WHAT WERE CPC’S IMPACTS ON MEDICARE EXPENDITURES, SERVICE USE, AND

QUALITY OF CARE DURING THE INITIATIVE? ........................................................................ 187

8.1. Key takeaways on the effect of CPC on Medicare expenditures, service use, and

quality of care .................................................................................................................. 187

8.2. Methods .......................................................................................................................... 191

8.2.1. Comparison group selection .............................................................................. 191

8.2.2. Outcomes ........................................................................................................... 194

vii

CONTENTS MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

8.2.3. Difference-in-differences estimation strategy .................................................... 196

8.2.4. Statistical power to detect effects ...................................................................... 199

8.2.5. Bayesian analysis .............................................................................................. 200

8.3. CPC-wide results ............................................................................................................ 200

8.3.1. Medicare expenditures ....................................................................................... 201

8.3.2. Service use ........................................................................................................ 225

8.3.3. Claims-based quality of care .............................................................................. 226

8.3.4. Aggregate impacts of CPC for all attributed beneficiaries ................................. 234

8.4. Discussion ....................................................................................................................... 235

9. WERE PRACTICES’ CARE DELIVERY APPROACHES ASSOCIATED WITH

IMPROVED EXPENDITURE AND UTILIZATION OUTCOMES?................................................ 239

9.1. Key takeaways ................................................................................................................ 240

9.2. Findings from previous analyses .................................................................................... 241

9.3. Approach to Year 4 analysis ........................................................................................... 242

9.4. Data and methods ........................................................................................................... 244

9.5. Practice-level model results ............................................................................................ 249

9.6. Beneficiary-level model results ....................................................................................... 250

9.6.1. Overview of results for Years 2, 3, and 4 ........................................................... 251

9.6.2. Results for CPC Year 4 ...................................................................................... 254

9.7. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 260

9.8. Future work ..................................................................................................................... 261

REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................................... 263

viii

MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

TABLES

1.1. CPC Milestones for program year (PY) 2016 .................................................................................. 1

1.2. CPC evaluation data sources .......................................................................................................... 5

2.1. Number of non-Medicare CPC payers in 2016, by lines of business included .............................. 14

2.2. Reasons that participating practices left CPC ............................................................................... 18

2.3. Comparison of practices that left CPC and practices that remained throughout CPC .................. 20

3.1. Range of CPC participating payers’ PMPM payments for PY2016 ............................................... 30

3.2. 2016 CPC shared savings methodologies among participating payers ............................................ 35

3.3. Results from CPC Medicare FFS shared savings calculations for performance in PY2014,

PY2015, and PY2016 by region ..................................................................................................... 38

3.4. Payers reporting that CPC generated savings for PY2014 or PY2015, among those

reporting results of their shared savings calculations, by region ................................................... 38

3.5. Timing and structure of aggregated data feedback from payers’ claims data in Colorado,

Ohio/Kentucky, and Oklahoma, PY2016 ....................................................................................... 45

3.6. Content and structure of aligned feedback reports in Arkansas and Oregon, PY2016 ................. 45

3.7. Percentage of practices that reported receiving and reviewing feedback reports and

patient-level data files all or most of the time in 2016, CPC-wide and by region........................... 46

3.8. Description of CPC learning support .............................................................................................. 51

3.9. Planned frequency and mode of individualized practice coaching and the percentage of

practices that reported receiving coaching at their practice site, by region, PY2016 .................... 56

4.1. CPC multistakeholder meeting participants ................................................................................... 67

4.2. Frequency of CPC payer-only and multistakeholder meetings...................................................... 67

4.3. Selected CPC collaborative outcomes, by region .......................................................................... 69

5.1. CPC Milestones for PY2016 .......................................................................................................... 80

5.2. Data sources on CPC practice change practices .......................................................................... 81

5.3. Primary care delivery domains measured by the M-PCMH-A in the CPC practice survey ........... 83

5.4. Types of data used by CPC practices to risk-stratify patients in PY2016, CPC-wide and

by region ........................................................................................................................................ 91

5.5. Average percentage of patients risk-stratified by and receiving care management from

CPC practices at end of PY2016, CPC-wide and by region .......................................................... 93

5.6. Conditions that CPC practices focused on for self-management support, CPC-wide and

by region ........................................................................................................................................ 99

5.7. Percentage of CPC practices with behavioral health specialist(s) co-located within the

practice in PY2016, CPC-wide and by region .............................................................................. 100

5.8. Integration of behavioral health specialists into primary care in PY2016 (among practices

with co-located behavioral health specialists), CPC-wide and by region .................................... 100

ix

TABLES MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

5.9. CPC practices’ methods of identifying patients for behavioral health services, in PY2016,

CPC-wide and by region .............................................................................................................. 101

5.10. CPC practices’ approaches for providing behavioral health care, in PY2016, CPC-wide

and by region ............................................................................................................................... 101

5.11. CPC practices’ approaches for providing medication management, in PY2016, CPC-wide

and by region ............................................................................................................................... 103

5.12. CPC practices method(s) of identifying patients for medication management, in PY2016,

CPC-wide and by region .............................................................................................................. 104

5.13. Percentage of CPC practices reporting each type of enhanced-access activity, in 2016,

CPC-wide and by region .............................................................................................................. 106

5.14. Percentage of CPC practices choosing various options to elicit patient experiences, CPC-

wide and by region ....................................................................................................................... 110

5.15. Percentage of CPC practices indicating that a survey or PFAC influenced various

practice changes, in PY2016, CPC-wide and by region .............................................................. 110

5.16. Percentages of eCQMs that CPC practices selected for quality improvement activities, in

PY2016, CPC-wide and by region ............................................................................................... 114

5.17. Percentages of CPC practice staff who generate and implement QI ideas and review

data, and intervals for tracking measures and progress, in PY2016, CPC-wide and by

region ........................................................................................................................................... 116

5.18. Percentages of CPC practices that chose CPC’s three care coordination activities, in

PY2016, CPC-wide and by region ............................................................................................... 121

5.19. Shared decision making topics chosen by CPC practices as of Quarter 1, PY2016 .................. 125

5.20. Sources of decision aids used by CPC practices, PY2016, CPC-wide and by region ................ 126

5.21. Reasons for selecting priority shared decision making areas, PY2016, CPC-wide and by

region ........................................................................................................................................... 126

5.22. Identification of eligible patients for shared decision making and documentation of shared

decision making, CPC-wide and by region .................................................................................. 128

5.23. Number of practices placed on a CAP for PY2016 performance ................................................ 134

5.24. Percentages of the 40 practices receiving CAPs by Milestone ................................................... 134

5.25. Facilitators of, and barriers to, implementation of CPC Milestones for PY2016, as

reported by deep-dive practices ................................................................................................... 141

6.1. Questions and domains included in this chapter ......................................................................... 147

6.2. Sample sizes and weighted survey response rates for the primary care clinician and

practice staff surveys, by round ................................................................................................... 149

7.1. Experiences included in the patient survey composite measures ............................................... 172

7.2. Number of questions that gauge patient experience in survey .................................................... 173

7.3. CPC patient survey rounds and fielding dates ............................................................................. 174

7.4. Percentage of Medicare FFS beneficiaries giving the top-box response for five composite

measures, CPC-wide, 2013 and 2016 ......................................................................................... 179

x

TABLES MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

7.5. Meaningful differences in Medicare FFS beneficiaries’ ratings of practices by select

practice and beneficiary characteristics, among CPC and comparison practices

combined, 2016 ............................................................................................................................ 180

7.6. The proportion of Medicare FFS beneficiaries giving the best response to 28 survey

questions not included in the composite measures, CPC and comparison practices, CPC-

wide .............................................................................................................................................. 183

8.1. Percentage impacts on Medicare FFS expenditures and service utilization over the four

years of CPC (all attributed beneficiaries) ................................................................................... 190

8.2. CPC regions and external comparison group regions ................................................................. 191

8.3. Regression-adjusted means and difference-in-differences estimates of CPC’s impact on

expenditure and utilization measures among attributed Medicare FFS beneficiaries,

annual and four-year cumulative CPC-wide estimates ................................................................ 205

8.4. Breakdown of savings in total Medicare FFS expenditures per beneficiary per month, by

service category ........................................................................................................................... 212

8.5. Regression-adjusted means and difference-in-differences estimates of CPC’s impact on

Medicare FFS expenditures, hospitalizations, and outpatient ED visits, cumulative four-

year estimates, by region ............................................................................................................. 214

8.6. Probability that CPC achieved savings, by year, based on a Bayesian analysis ........................ 219

8.7. Estimates of the cumulative impact on PBPM Medicare expenditures without fees, from

sensitivity tests ............................................................................................................................. 221

8.8. Variation in cumulative impact on PBPM Medicare expenditures without fees, by practice

characteristics at baseline ............................................................................................................ 224

8.9. Regression-adjusted means and estimated difference-in-differences estimates of CPC’s

impact on selected quality-of-care process and outcome measures: annual and four-year

cumulative CPC-wide estimates ................................................................................................... 229

8.10. Aggregate CPC-wide results, by year and cumulative ................................................................ 235

9.1. Key primary care delivery approaches from the M-PCMH-A ....................................................... 246

9.2. Mean scores (out of a maximum of 12) by year of key primary care delivery approaches ......... 247

9.3. Variation of key primary care delivery approaches across CPC practices in Year 4 .................. 254

9.4. Associations of key primary care delivery approaches with annual per beneficiary

outcomes in Year 4 ...................................................................................................................... 255

9.5. Relationships of key primary care delivery approaches with annual per beneficiary

outcomes for high-risk beneficiaries in Year 4 ............................................................................. 257

9.6. Variation in the associations between key primary care delivery approaches and annual

per beneficiary outcomes with clinical involvement of nonphysicians, Year 4 ............................. 259

xi

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

FIGURES

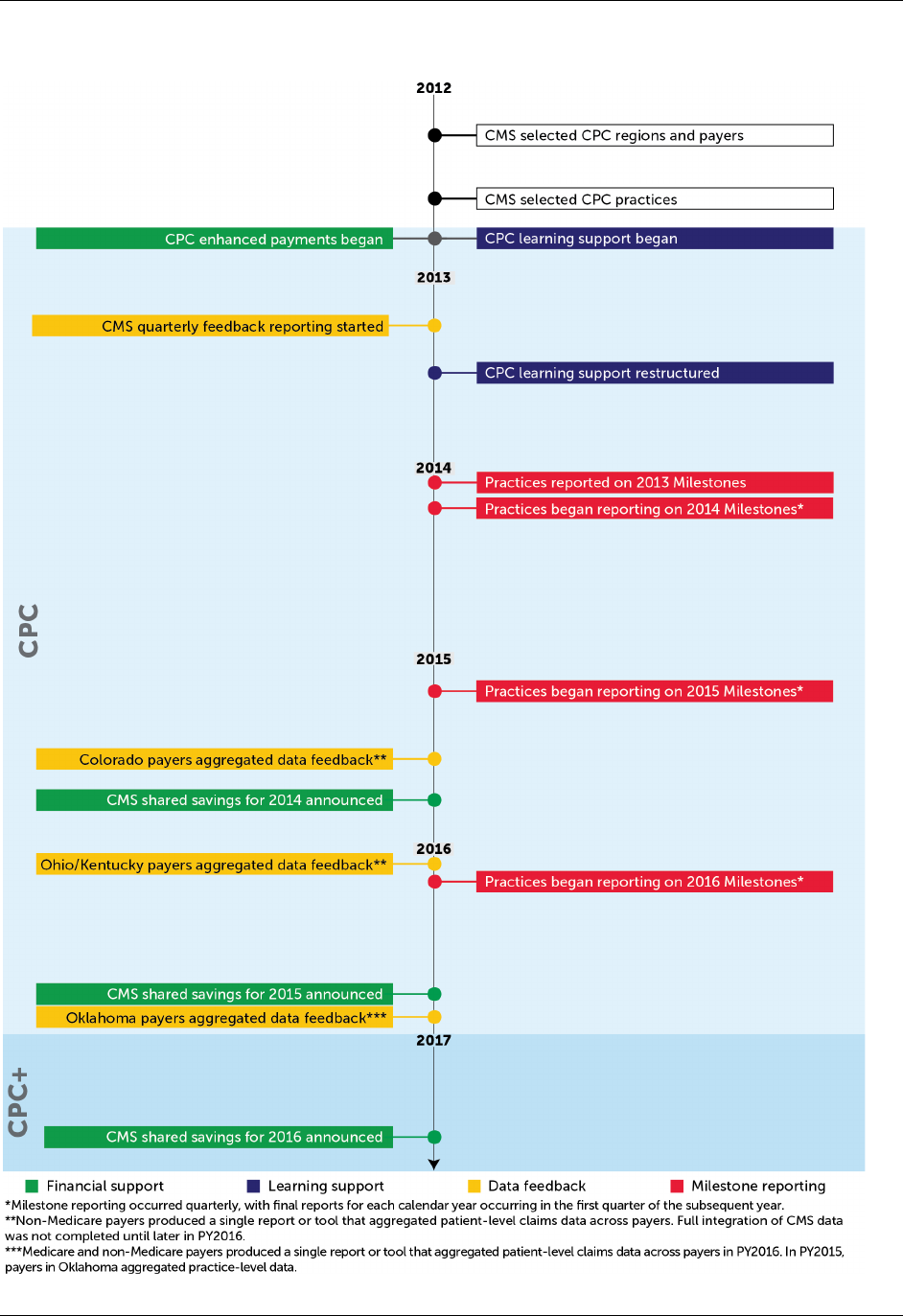

1.1. CPC implementation timeline ........................................................................................................... 4

2.1. CPC regions, non-Medicare payers, practices, and patients......................................................... 11

2.2. Participation of self-insured clients in CPC in 2016 ....................................................................... 15

2.3. Change in the number of CPC participating practices ................................................................... 18

3.1. Median CPC funding per practice, CPC-wide and by region ......................................................... 31

3.2. Median CPC funding per clinician, CPC-wide and by region......................................................... 31

3.3. Median attributed patients per practice and median CPC funding per attributed life, CPC-

wide and by region (excluding Oklahoma*) ................................................................................... 32

3.4. Practices’ perceptions in PY2016 of Medicare and non-Medicare shared savings

methodologies for assessing PY2015 performance ...................................................................... 36

3.5. Practices’ perceived adequacy of Medicare FFS care management fees relative to the

costs of implementing CPC in PY2014, PY2015, and PY2016 ..................................................... 39

3.6. Practice-reported total CPC spending in PY2014, PY2015, and PY2016 for selected cost

categories, in millions ..................................................................................................................... 40

3.7. Percentage of practices that reported receiving and reviewing CPC data feedback all or

most of the time, PY2014 and PY2016 .......................................................................................... 46

3.8. Percentage of practices reporting that CPC data feedback was somewhat or very useful,

among practices that reported seeing the feedback, PY2014 and PY2016 .................................. 48

3.9. Percentage of CPC clinicians and staff receiving various types of CPC assistance during

the past six months, 2016 .............................................................................................................. 53

3.10. Number and format of CPC group learning activities, PY2013 through PY2016 .......................... 54

3.11. Percentage of system-owned practices reporting staff in the practice site or their larger

health care organization communicate with RLF, in 2016 ............................................................. 57

3.12. Percentage of practices reporting interacting with their RLF at least once a month,

PY2014–PY2016, CPC-wide and by region .................................................................................. 58

3.13. Percentage of practices reporting they received coaching or assistance from non-

Medicare payers in the past six months, CPC-wide and by region, PY2016 ................................ 60

3.14. Percentage of CPC practices rating their RLF as excellent or very good in meeting their

CPC-related needs, in PY2014 and PY2016, by region ................................................................ 61

3.15. Reports of how useful various types of CPC assistance were to CPC practices, among

those that received the assistance, 2016....................................................................................... 62

5.1. CPC practices’ mean 2012 M-PCMH-A scores, with 2014, 2015, and 2016 gains, for the

seven domains and overall ............................................................................................................ 85

5.2. CPC and comparison practices’ mean M-PCMH-A scores in 2016, for the seven domains

and overall ...................................................................................................................................... 86

xiii

FIGURES MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

5.3. Distribution of CPC and comparison practices’ overall M-PCMH-A scores over time ................... 87

5.4. CPC practices’ average overall M-PCMH-A scores, for all practices and by practices’

2012 score ..................................................................................................................................... 88

5.5. Percentages of physicians who agree or strongly agree with statements about quality

improvement, CPC and comparison practices, 2016 .................................................................. 117

5.6. Data sharing by practices that are in a health care system or group .......................................... 132

5.7. Data sharing by practices that are not part of a system .............................................................. 132

6.1. Percentage of physicians reporting high levels of burnout, CPC and comparison

practices, 2013 and 2016 ............................................................................................................. 153

6.2. Percentage of physicians reporting how often they felt burned out from their work in the

past year, CPC and comparison practices, 2013 and 2016 ........................................................ 154

6.3. Percentage of physicians who say they agree with the statement on burnout once or

more per week, CPC and comparison practices, 2016 ............................................................... 155

6.4. Physician scores on a subset of the Maslach Burnout Inventory scales (0 = more burnout,

1 = less burnout), CPC and comparison practices, 2013 and 2016 ............................................ 156

6.5. Percentage of CPC practice members reporting high levels of burnout, 2013 and 2016 ........... 157

6.6. Percentage of physicians reporting great or moderate control over various aspects of

their work, CPC and comparison practices, 2016 ........................................................................ 159

6.7. Overall scores on the control-over-work summary composite for CPC practice members,

2013 and 2016 ............................................................................................................................. 160

6.8. Proportion of time each week that physicians do work that is well-matched to their

training, CPC and comparison practices, 2013 and 2016 ........................................................... 161

6.9. Percentage of CPC practice members saying that 75 percent or more of their time is

spent doing work that is well-matched to their training, 2016 ...................................................... 162

6.10. Extent of physician agreement with statement, “Overall I am satisfied with my current

job,” CPC and comparison practices, 2013 and 2016 ................................................................. 163

6.11. Extent of agreement with statement, “Overall I am satisfied with my current job,” by CPC

practice members, 2013 and 2016 .............................................................................................. 164

6.12. CPC physician reports of how CPC participation changed the quality of care or service

provided to patients, 2016 ............................................................................................................ 165

6.13. CPC practice members’ reports of how much they would support or oppose their

practice’s participation in CPC if they could do it all over again, 2016 ........................................ 166

6.14. Percentage of CPC physicians reporting each factor as a main reason for supporting

participation in CPC, among those that would support participating again, 2016 ....................... 167

6.15. Percentage of CPC physicians reporting each factor as a main reason for opposing

participation in CPC, among those that would oppose participating again, 2016........................ 169

7.1. Percentage of Medicare FFS beneficiaries giving the best response in 2013 and 2016, for

five composite measures, CPC and comparison practices, CPC-wide ....................................... 177

xiv

FIGURES MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

7.2. Percentage of Medicare FFS beneficiaries answering with the best response, by

composite measure, CPC and comparison practices, CPC-wide ............................................... 178

7.3. Percentage of Medicare FFS beneficiaries giving the best response in 2016, CPC and

comparison practices, CPC-wide ................................................................................................. 182

8.1. Estimated impact on Medicare FFS expenditures without care management fees, by year ....... 202

8.2. Regression-adjusted mean Medicare Part A and Part B expenditures PBPM, excluding

Medicare’s CPC care management fees, all beneficiaries, CPC-wide ........................................ 203

8.3. Estimated impact on Medicare Part A and Part B expenditures PBPM, excluding CPC

care management fees, all beneficiaries, CPC-wide ................................................................... 204

8.4. Probability that CPC achieved savings (before fees) during initiative ......................................... 218

9.1. Distribution of changes in outcomes among CPC practices between the year before CPC

(baseline) and Year 4 ................................................................................................................... 239

9.2. Distribution of scores by year for key primary care delivery approaches .................................... 247

9.3. Associations of improvements in continuity, after-hours access, and follow-up after acute

care with changes in practice-level service use and expenditures in Years 2, 3, and 4 ............. 250

9.4. Associations between primary care delivery approaches and outcomes for Years 2, 3,

and 4 ............................................................................................................................................ 251

9.5. Predicted associations between primary care delivery approaches and outcomes, at

average-risk and high-risk HCC values for Years 2, 3, and 4 ......................................................... 252

9.6. Predicted associations between key primary care delivery approaches and outcomes for

practices with 25th percentile (10) and maximum (12) levels of clinical involvement of

nonphysicians for Years 2, 3, and 4 ............................................................................................... 253

xv

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In October 2012, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) of the Centers

for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the four-year Comprehensive Primary Care

(CPC) initiative. The goal of CPC was to improve primary care delivery, health care quality, and

patient experience, and lower costs. CPC also aimed to enhance clinicians’ and staff members’

experience. CMS leveraged the support of 39 other public and private payers to target the

transformation of primary care delivery in nearly 500 primary care practices in seven regions

across the United States. These practices included more than 2,000 clinicians and served around

3 million patients.

CPC required practices to transform across five key care delivery functions: (1) access and

continuity, (2) planned care for chronic conditions and preventive care, (3) risk-stratified care

management, (4) patient and caregiver engagement, and (5) coordination of care across the

medical neighborhood. CMS specified a series of Milestones to help move practices along the

path of implementing the five functions, and it updated the requirements for each Milestone

annually to build on practices’ progress in the prior year. CMS assessed whether practices met

targets set within the Milestones, which were considered minimum requirements to remain in the

initiative. Although the CPC Milestones overlap with many of the activities typically included in

existing patient-centered medical home (PCMH) recognition programs, CPC did not require

practices to have or obtain PCMH recognition, although nearly 40 percent did have this

recognition when they applied to CPC

. CPC supported practices’ transformation with: (1)

prospective care management fees and the opportunity to earn shared savings in addition to their

usual payments; (2) data feedback on cost, utilization, and quality; and (3) learning support.

1

This fourth and final report to CMS covers the full CPC intervention period (October 2012

through December 2016). The report examines: (1) who participated in CPC; (2) the supports

practices received; (3) how practices implemented CPC and changed the way they delivered

health care; (4) the impacts of CPC on clinicians’ and staff members’ experience; and (5) the

impacts of CPC on patient experience, cost, service use, and quality-of-care outcomes for

attributed Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries. (See Taylor et al. 2015, Peikes et al.

2016a, and Peikes et al. 2016b, respectively, for results from the first three years of the

initiative.)

This Executive Summary provides a brief overview of findings and a more detailed

summary of findings in each chapter of the final report.

1

The CPC change package (https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/cpcidiagram.pdf) describes the underlying logic of

CPC, including the primary and secondary drivers to achieve the aims of CPC and the concepts and tactics that

support the changes.

xvii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

Effects on Outcomes for Attributed Medicare FFS Beneficiaries

• CPC reduced hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits for Medicare

FFS beneficiaries attributed to the CPC practices more than for beneficiaries

attributed to comparison practices.

- The rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for Medicare FFS beneficiaries grew for both

CPC and comparison practices, but growth in ED visits and hospitalizations was 2

percent less for attributed beneficiaries in CPC practices than for those in comparison

practices. The favorable difference for ED visits was more pronounced in the last two

years of CPC.

• Medicare expenditures for attributed beneficiaries grew less for CPC practices than

for comparison practices, but the savings were not enough to cover Medicare’s CPC

care management fees.

- Medicare expenditures without factoring in CPC care management fees increased for

both CPC and comparison practices, but the increase was $9 per beneficiary per month

(PBPM) (1 percent) less for Medicare FFS beneficiaries attributed to CPC practices than

for beneficiaries attributed to comparison practices. This difference was not statistically

significant, and estimated effects became less pronounced over time.

- After including care management fees, Medicare expenditures increased by $6 PBPM

more for CPC practices than for comparison practices. The difference was not

statistically significant.

- There is a 94 percent probability that CPC generated some reduction in Medicare

expenditures (excluding the care management fees) during the intervention period.

However, our analysis indicates the likelihood that those savings were greater than the

average $15 PBPM fee that Medicare paid over the four years is less than 1 percent. In

other words, although CPC did reduce Medicare Part A and B expenditures slightly

relative to expenditures in comparison practices, it is highly unlikely that these Medicare

savings generated by CPC were enough to cover the CPC care management fees

Medicare paid.

• CPC had minimal effects on the limited claims-based quality-of-care process and

outcome measures examined.

- Differences on most claims-based quality-of-care measures for Medicare beneficiaries

were not statistically significant over the course of CPC, except for a small (3 percent)

reduction in the likelihood of an ED revisit within 30 days of an outpatient ED visit

relative to the comparison group.

• CPC had little impact on beneficiaries’ experience of care.

- Findings for Medicare FFS beneficiaries in CPC and comparison practices were

comparable on most measures of patient experience, except for an increase in

transitional care for beneficiaries in CPC practices.

xviii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

Effects on Care Delivery

• Practices engaged in substantial, challenging transformation and improved how they

delivered care over the course of CPC.

- Overall, the largest areas of improvement were in risk-stratified care management,

expanded access to care, and continuous improvement driven by data. Based on data

from the annual practice survey, CPC practices’ approach to risk-stratified care

management was more advanced than that of comparison practices. CPC practices’

approaches to other aspects of care delivery were slightly more advanced than those of

comparison practices.

- Practices faced barriers to change, including burden associated with quality monitoring

and reporting for CMS and other payers, existing incentives in the FFS payment system

that encourage volume of services over efficient use of services, and lack of

infrastructure for comprehensive and efficient health information exchange between

providers.

Effects on Clinician and Staff Experience

• Clinicians and staff in CPC practices had largely favorable views of CPC. Although

CPC required an intensive amount of work for practices, it did not affect burnout,

control over work, alignment of work with training, and job satisfaction among

clinicians and staff, favorably or unfavorably.

- Eighty percent of responding physicians at CPC practices reported that CPC had

improved the quality of care or service they provide to their patients, and if they could

do it again, 79 percent would support their practice’s participation in CPC. Only 12

percent of physicians would oppose participation in CPC and 9 percent reported not

knowing enough about CPC to answer. However, physicians at CPC practices,

regardless of whether they would support their practice’s participation in CPC, indicated

that CPC administrative reporting presented a burden and that the transformation work

in CPC was difficult (reported by 44 and 34 percent of physicians that would support

CPC participation, respectively).

Supports Provided to Practices

• CMS and other participating payers provided substantial support for CPC practices

and, in general, practices found these supports helped them accomplish the required

work.

- Medicare FFS and other payers prospectively paid care management fees to practices

totaling $479 million over the four-year initiative. Medicare FFS paid 58 percent of the

total care management fees to CPC practices. Other payers contributed the remaining

care management fees. In the final year of CPC (2016), this funding translated to a

median of $179,519 per practice ($50,189 per clinician). These payments accounted for

a median of 10 percent of 2016 practice revenue.

- CMS and 32 of the 36 non-CMS payers that participated throughout the initiative

provided data feedback to practices; depending on the payer, the feedback included cost,

utilization, and/or quality data reported at the practice level, patient level, or both. Payers

in three regions—Colorado, Ohio/Kentucky, and Oklahoma—achieved data aggregation,

xix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

producing a single tool that aggregated data across payers each quarter (non-Medicare

FFS payers aggregated data first in late 2015 or 2016 and then Medicare FFS integrated

its data into those efforts in mid- to late-2016).

- CMS and its contractors provided practices with a variety of group learning activities,

including webinars and all-day, in-person meetings. Regional learning faculty (RLF)

also provided individualized coaching to practices they identified as needing additional

support. On the 2016 CPC practice survey, 56 percent of practices reported that they had

received in-person coaching at their practice site from RLF in the prior six months.

Participation

• Payer and practice participation remained relatively stable throughout the initiative.

- Only three small payers left CPC during the initiative, and by the end of the initiative,

439 (or 87 percent) of the original 502 practices were still participating. Most

commonly, practices that left the initiative did so to join Medicare accountable care

organizations (ACOs), because CMS did not permit practices to participate in CPC and a

Medicare ACO.

- Many of the payers and practices that participated in CPC are participating in

Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+), another primary care model that began in

January 2017 and builds on lessons learned from CPC and other PCMH models. Of the

36 payers that remained in CPC throughout the initiative, 28 joined CPC+. Moreover,

412 of the 422 practices that remained through the end of CPC and were located in

CPC+ regions (as well as 15 of the 57 practices that withdrew or were terminated from

CPC for reasons other than closing and were located in CPC+ regions) decided to join

CPC+.

In the rest of this executive summary, we provide a detailed summary of the key results for

each chapter of this report.

DETAILED SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

ES.1. Participation remained relatively stable (Chapter 2)

Payer participation. CMS and 39 other payers, which included private health plans in all

CPC regions and state Medicaid agencies in five regions, committed substantial public and

private resources to redesign primary care in CPC’s seven regions.

2,3

Over the course of CPC,

payer participation remained steady in all seven regions—only three small payers left CPC

during the initiative (Figure ES.1).

4

In general, payers remained engaged in and committed to the

2

Payers that participated in more than one region were counted separately for each region in which they

participated. At the start of CPC, 31 distinct payers participated in CPC in addition to Medicare.

3

New Jersey and New York were the two regions whose Medicaid agencies did not participate. In addition, the

Oklahoma Health Care Authority participated in the Oklahoma region and was counted as a Medicaid participating

payer, although it did not provide care management fees to participating practices.

4

In addition to withdrawals, one participating payer acquired another participating payer (thus subtracting one payer

from the total). Moreover, one national payer that was participating in two CPC regions joined in a third region

during the first year of the initiative (thus adding one payer to the total).

xx

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

initiative—most reported sustained or increasing commitment to primary care redesign and to

alternative payment more generally during interviews conducted in the summer and early fall of

each program year. Demonstrating their continued interest, 28 of the 36 payers that remained in

CPC throughout the initiative also joined CPC+, which CMS launched in January 2017 and

builds on lessons learned from CPC.

Participating payers included most of their lines of business in CPC, but varied on whether

they included self-insured clients. Many of the 26 payers with self-insured clients initially

struggled to enroll these clients in CPC. Through concerted efforts to engage self-insured clients,

the number of payers reporting that all or nearly all of their self-insured clients participated in

CPC doubled from 7 to 14 during the initiative.

Practice participation. CMS selected 502 diverse practices to participate in CPC. These

practices included independent and system-owned practices, some practices that were recognized

as medical homes and others that were not, and practices of different sizes. Practice participation

remained relatively stable throughout the initiative—only 1.8 percent (9 practices) were

terminated from the initiative and another 11.2 percent (56 practices) voluntarily withdrew.

Among practices that withdrew, the most common reason was to join a Medicare ACO, since

CMS did not allow concurrent participation in CPC and any of its shared savings models (29 of

the 56 practices), or due to challenges meeting CPC requirements (13 practices). In addition, 5

practices voluntarily withdrew after assessing the terms and conditions of CPC participation

early in the initiative, and 6 practices closed.5 By the end of the initiative on December 31, 2016,

439 practices remained in CPC. Of the 422 of these practices located in CPC+ regions, 412 (98

percent) applied and were selected by CMS to join CPC+, as did 15 of the 57 practices that

withdrew or were terminated from CPC for reasons other than closing.6

Patient participation. CPC was designed to transform whole practices; as such, CPC

practices were expected to deliver the same care to all patients they saw. This included patients

of participating payers that were attributed to their practice (for which practices received care

management fees), patients of participating payers who were not attributed to the practice,

patients of nonparticipating payers, and uninsured patients. The numbers of attributed and total

patients were substantial, with attributed patients estimated at 1.1 million (321,000 of these were

Medicare FFS beneficiaries), and total patients estimated at 3.1 million across all participating

practices in 2016.

5

Several CPC practices also changed their composition during the initiative. Five CPC practices each split into two

practices (adding five CPC practices to the total count). Three CPC practices merged with other CPC practices

(subtracting three CPC practices from the total count).

6

Three counties (Putnam, Rockland, and Westchester counties) that were included in the Capital District-Hudson

Valley Region in New York for CPC were not included in the region for CPC+. Seventeen CPC practices were

located in these counties and thus ineligible to apply for CPC+.

xxi

xxii

Figure ES.1. CPC regions, Non-Medicare payers, practices, and patients

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

ES.2. CPC delivered substantial financial support, data feedback, and

learning supports to practices

(Chapter 3)

CMS and other participating payers provided significant support to CPC practices and, in

general, practices found that these supports helped them accomplish the work required for CPC.

In addition to traditional payments, Medicare FFS and other payers provided substantial non-

visit-based financial support for participating practices. CMS and most other payers also

provided data feedback to participating practices and, in five regions, payers aligned or

aggregated that data feedback across payers in the region. Many practices considered CPC’s data

feedback useful, but some found it challenging to incorporate into their improvement efforts.

Many practices also considered CPC learning supports, which included group learning activities

and—for a subset of practices—individualized coaching, important for achieving the aims of

CPC.

Financial supports. Medicare FFS and all but 2 of the 36 other participating payers that

remained throughout the initiative provided monthly, non-visit-based care management fees to

CPC practices, in addition to usual payments for services, to support enhanced, coordinated

care.

7

CMS care management fees for Medicare FFS attributed beneficiaries averaged $20

PBPM for the first two years of CPC and $15 PBPM for the last two years.

8

CMS paid higher

care management fees in the first two years of the initiative to support upfront investments in

practice transformation. Among other payers, care management fee amounts varied considerably

but most were lower than Medicare FFS amounts.

According to Medicare FFS payment data and practice-reported data on payments received

from other payers, care management fees to practices from Medicare FFS and other payers

translated to a median of $7.95 per member per month (PMPM) per attributed patient (that is, for

patients attributed to practices by CPC payers) or $3.55 PMPM per active patient (that is,

patients attributed by CPC payers and nonattributed patients).

Together, this funding totaled $479.1 million over the

four-year initiative. Reflecting the decrease in care

management fees over time by Medicare and 30 percent of

other payers, the median payments to practices (in addition to

their regular revenues) were higher in 2013 ($227,849) and

2014 ($203,949) than in 2015 ($175,774) and 2016

($179,519). Similarly, median payments per clinician

7

One payer provided capitated payments instead of PMPM payments. One payer did not contribute enhanced

payments to practices.

8

CMS paid $20 PBPM in care management fees during Quarters 1 through 9 of CPC (through December 2014), and

it paid $15 PBPM from January 2015 onward (for the last eight quarters of CPC). Therefore, over the 17 quarters of

CPC, the average PBPM care management fee paid for patients still attributed to a practice was approximately $18.

However, the average PBPM fee received in the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis sample used to estimate the effects of

CPC was $15, because we retained all beneficiaries after they were first attributed, even if a practice did not receive

fees for them because they were no longer attributed.

For the median practice, CPC

care management fees totaled

more than $175,000 per year,

in addition to their regular

revenues. This represented

more than $50,000 per clinician

per year.

xxiii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

decreased from $70,045 in 2013 to $50,189 in 2016.

9

Depending on the year, these payments

accounted for 10 to 20 percent of practice revenue. Medicare and about two-thirds of other

participating payers also provided practices the opportunity to share in any savings accrued

during each of the last three years of the initiative (program year [PY] 2014, PY2015, and

PY2016). Medicare FFS calculated savings at the regional level (that is, it compared total costs

of attributed Medicare FFS beneficiaries across all CPC practices in a region to an expenditure

target); other payers that offered the opportunity of shared savings calculated savings in a variety

of ways (including at the regional, system, or practice level, or among groups of unaffiliated

practices). CMS’s shared savings calculations serve a different purpose than the evaluation and,

as such, use a different approach.

10

Medicare FFS and other payers reported the following shared savings results:

• For PY2014 performance, Medicare FFS found that CPC generated savings in one region—

Oklahoma. Medicare FFS shared savings payments to Oklahoma practices totaled $658,129.

Across all regions, 10 of the 20 non-Medicare FFS payers that reported results of their

shared savings calculations for PY2014 found that CPC generated savings.

• For PY2015 performance, Medicare FFS found that CPC generated savings in four

regions—Arkansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, and Oregon. Medicare FFS shared savings

payments to practices in these regions totaled more than $13 million. Across all regions, 10

of the 15 non-Medicare FFS payers that reported results of their shared savings calculations

for PY2015 found that CPC generated savings.

• For PY2016 performance, Medicare FFS found that CPC generated savings in two

regions—Arkansas and Oklahoma. Medicare FFS shared savings payments to practices in

these regions totaled more than $10 million. Non-Medicare payers did not report results for

this performance year in time for inclusion in this report.

More than three-quarters of practices reported on the CPC practice surveys in 2014, 2015,

and 2016 that CPC payments—including care management fees and, when relevant, shared

savings payments—were adequate or more than adequate relative to the costs of implementing

CPC.

Data feedback. By PY2015, CMS and 32 of the 36 non-CMS payers participating at that

time provided data feedback to practices. At the outset of CPC, payers primarily provided

practices with individual payer reports.

11

The payers designed the content and structure of this

feedback individually, often based on data feedback they were already providing to practices

before CPC. Largely in response to practices’ input on data feedback, most payers took steps

9

Payments in PY2013 were higher than in PY2014 because PY2013 included several months of CMS payments in

late 2012.

10

See Chapter 3 for information on Medicare and other payers’ shared savings methodologies for CPC. See Chapter

8 for information on the methodology used for and results from the CPC impact evaluation.

11

As part of its evaluation contract, Mathematica Policy Research produced the Medicare FFS data feedback reports

and patient-level data files for CMS.

xxiv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

over the four-year initiative to provide new or additional forms of data feedback to practices or to

improve existing reports.

In addition, by the end of CPC, payers in five

regions were using a common approach to data feedback.

Payers in Arkansas and Oregon took steps to align the

cost and service use measures included in individual

payer feedback reports with each other and with

Medicare FFS. Payers in Colorado, Ohio/Kentucky, and

Oklahoma achieved data aggregation—producing a

single tool to aggregate data across payers each quarter

(non-Medicare FFS payers aggregated data first in late

2015 or 2016 and then Medicare FFS integrated its data

into those efforts in mid- to late-2016).

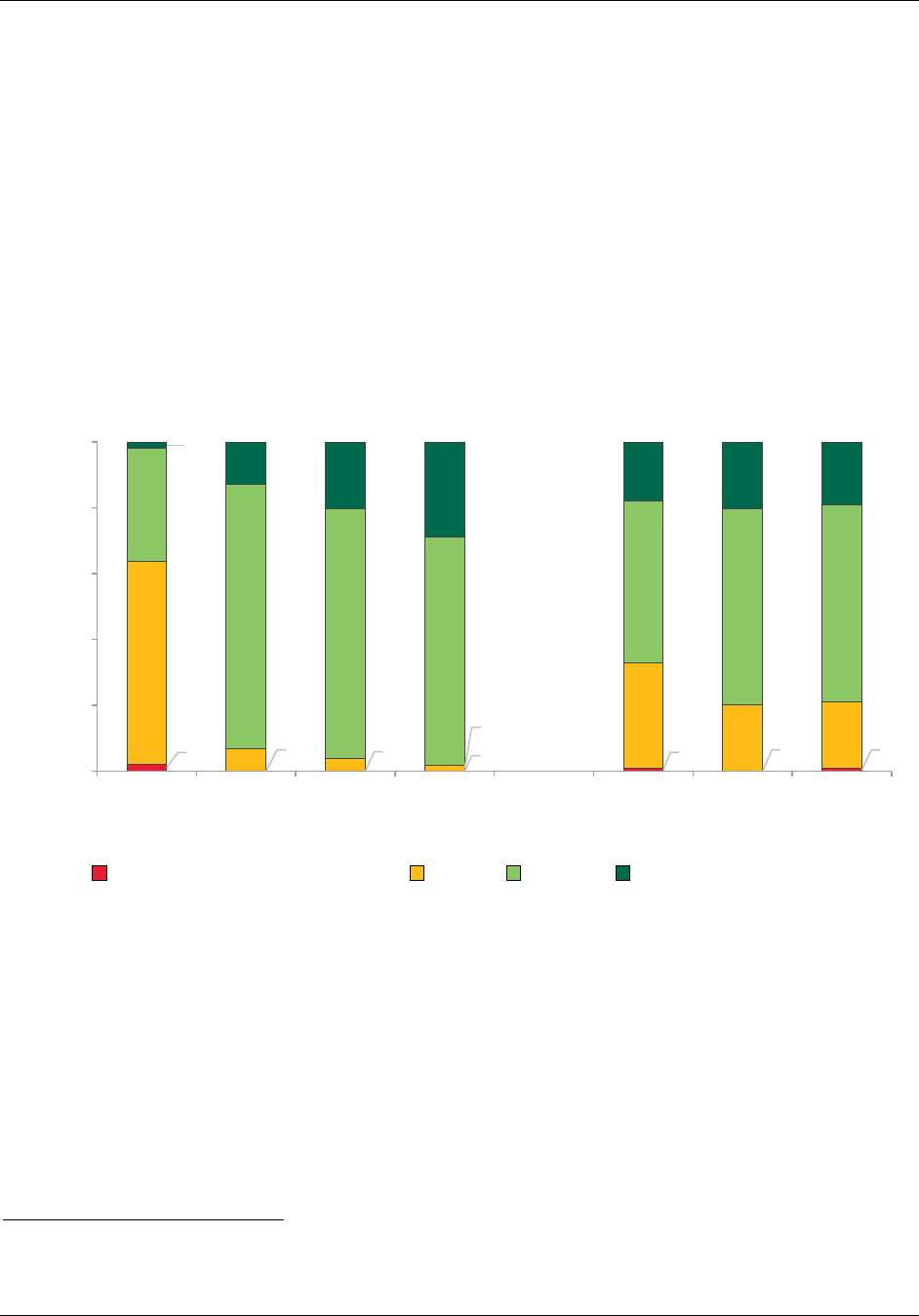

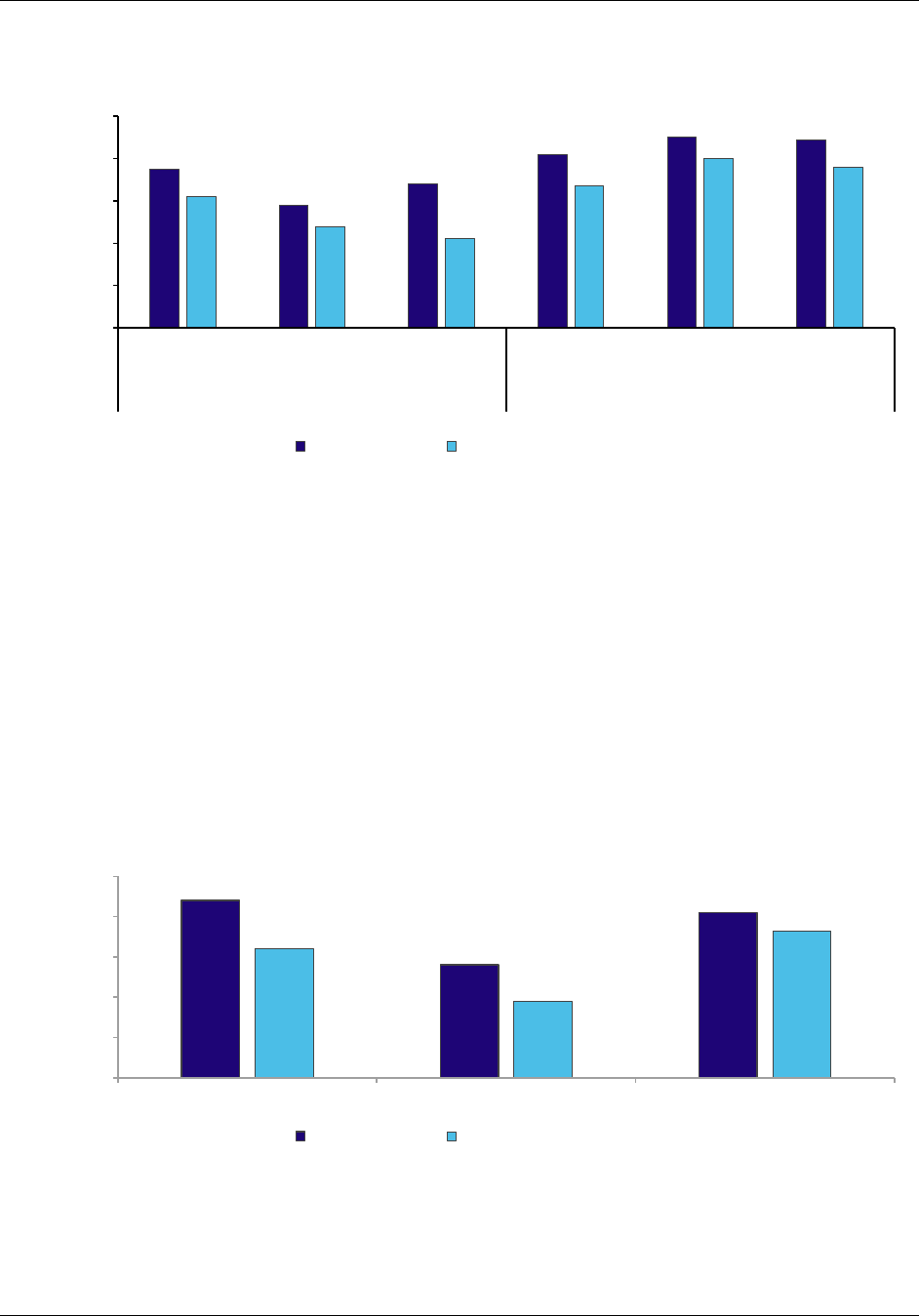

Although most practices reported that they had reviewed data feedback, the frequency with

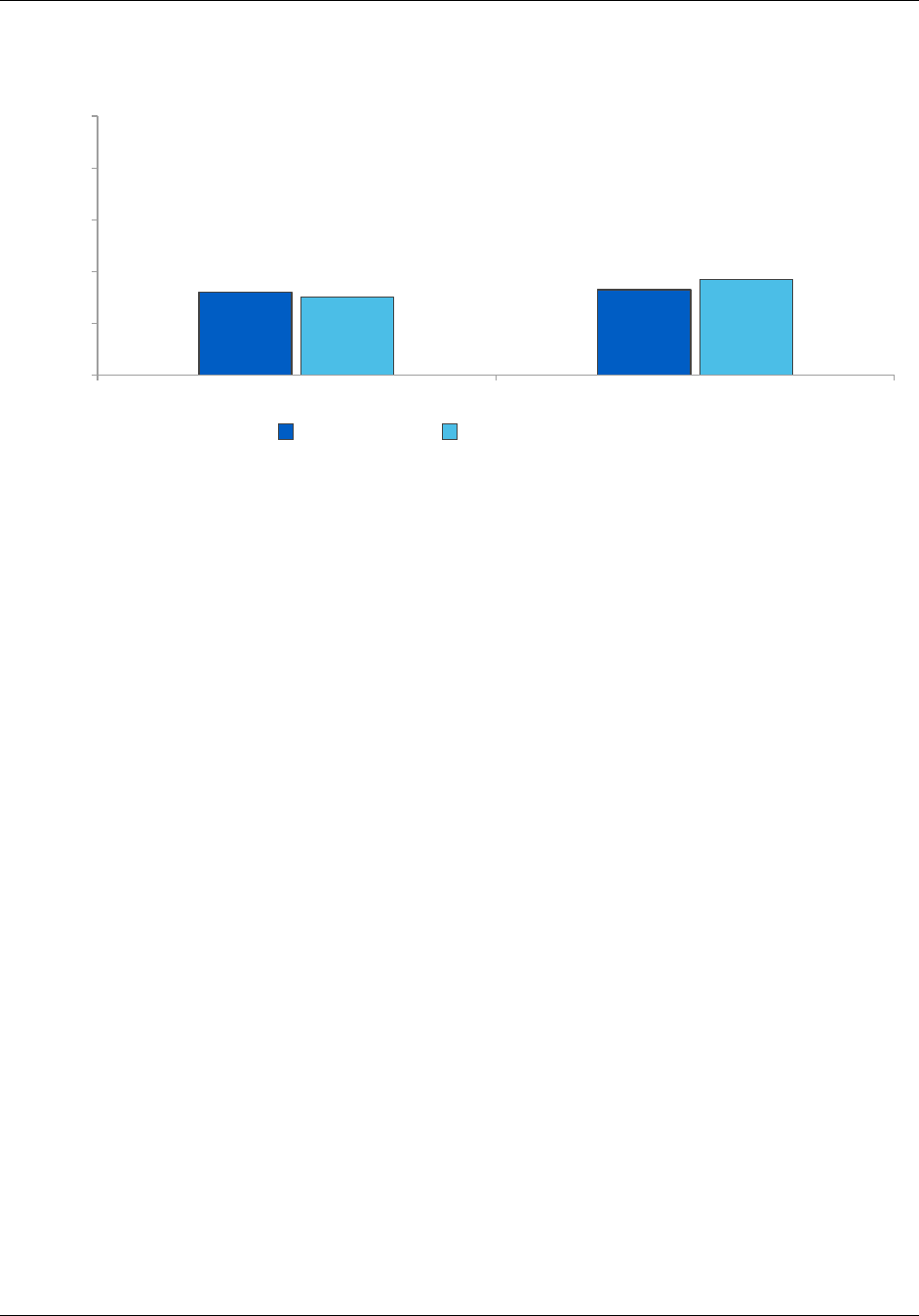

which practices reviewed reports varied by report type and over time (Figure ES.2). During

interviews with deep-dive practices—a set of 21 CPC practices selected for intensive study

throughout the initiative—some of these practices reported that they had used CPC data feedback

to identify goals for their quality improvement (QI) work or to improve identification of high-

risk patients.

Figure ES.2. Percentage of practices that reported receiving and reviewing

CPC data feedback all or most of the time, PY2014 and PY2016

Source: CPC practice survey, administered April through July 2014 and April through August 2016.

Through interviews with deep-dive practices and CMS contractors, and surveys of CPC

practices and clinicians, we identified several challenges practices faced using data feedback.

Some practices:

18

28

16

23

22

29

15

16

55

53

31

35

26

32

23

25

0

20

40

60

80

100

2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016

Feedback reports Patient-level data Feedback reports Patient-level data

From Medicare FFS From other payers

Percentage of practices

Always

Most of the time

From Medicare FFS From other payers

Medicare and almost all other

participating payers provided

practices with data feedback during

CPC.

While important progress was made

on providing feedback and refining it

over time, areas for improvement

include educating practices on using

feedback and making feedback

more timely and actionable.

xxv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

• Reported that only staff at the health system level (and not the practice level) reviewed

feedback reports; this was reported by health system-owned practices

• Viewed data feedback as complex and difficult to understand

• Lacked the time or skills to use data feedback effectively

• Viewed factors driving high costs as out of their control

Learning support. CMS contracted with TMF Health

Quality Institute to provide learning supports to CPC practices.

CMS, TMF, and its subcontractors—referred to as regional

learning faculty (RLF)—provided practices with a variety of

group learning activities, including webinars and all-day, in-

person meetings. CMS and its contractors adapted learning

activities over time to encourage additional peer-to-peer

learning, emphasize the use of data for practice improvement, and engage practices in

implementing small tests of change.

RLF also had limited resources to provide a subset of practices with individualized

coaching. RLF selected practices to receive this coaching and adjusted the intensity depending

on practices’ progress toward CPC Milestones and their performance on quarterly Medicare

feedback reports. On the 2016 CPC practice survey, 56 percent of participating practices

reported that they had received in-person coaching at their practice site from RLF in the prior six

months.

According to the 2016 CPC practice survey, non-Medicare payers also provided coaching or

assistance to 71 percent of participating practices in the prior six months. The percentage that

reported that they had received this assistance varied considerably by region, from 52 percent of

practices in Oregon to 96 percent in Ohio/Kentucky.

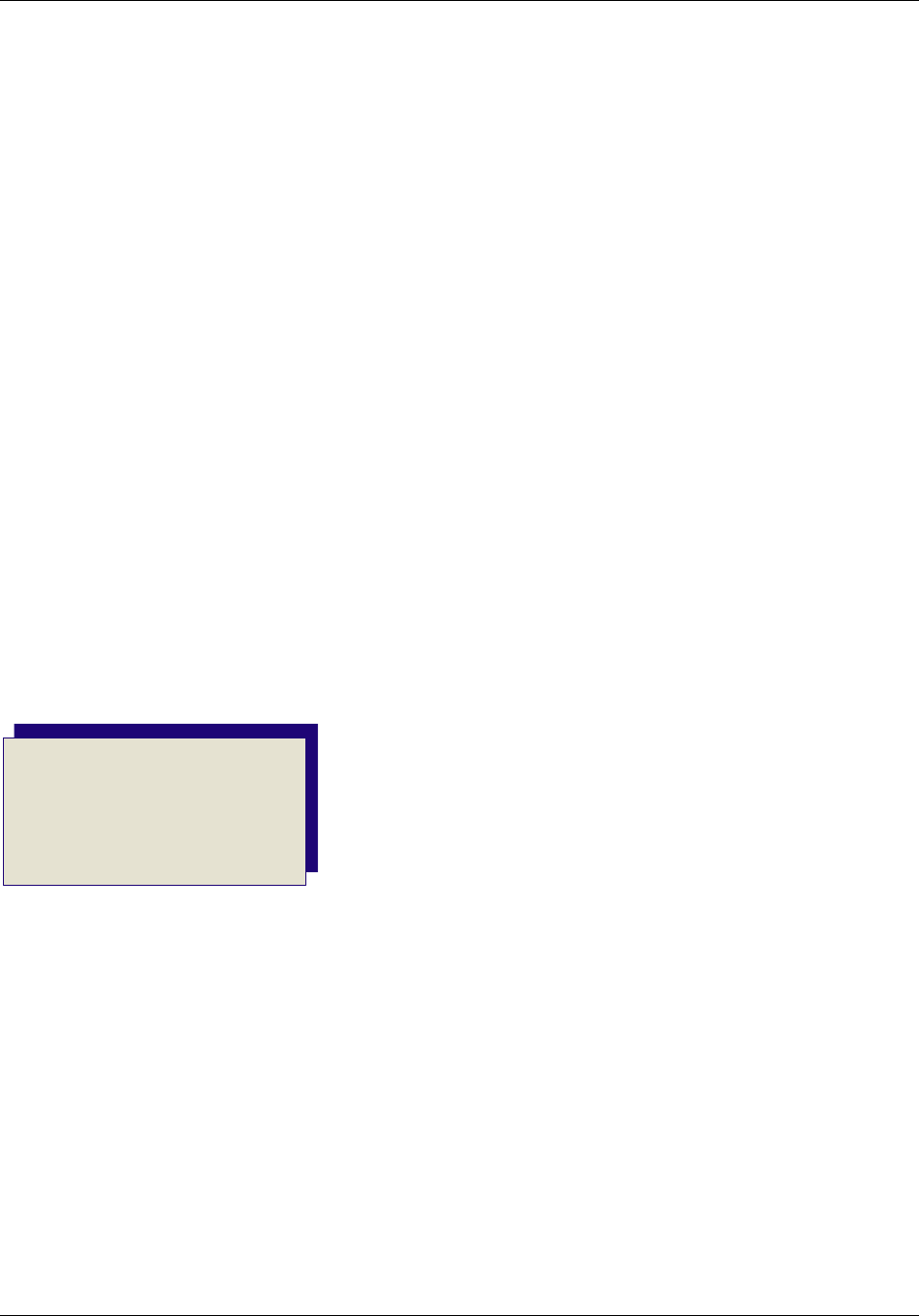

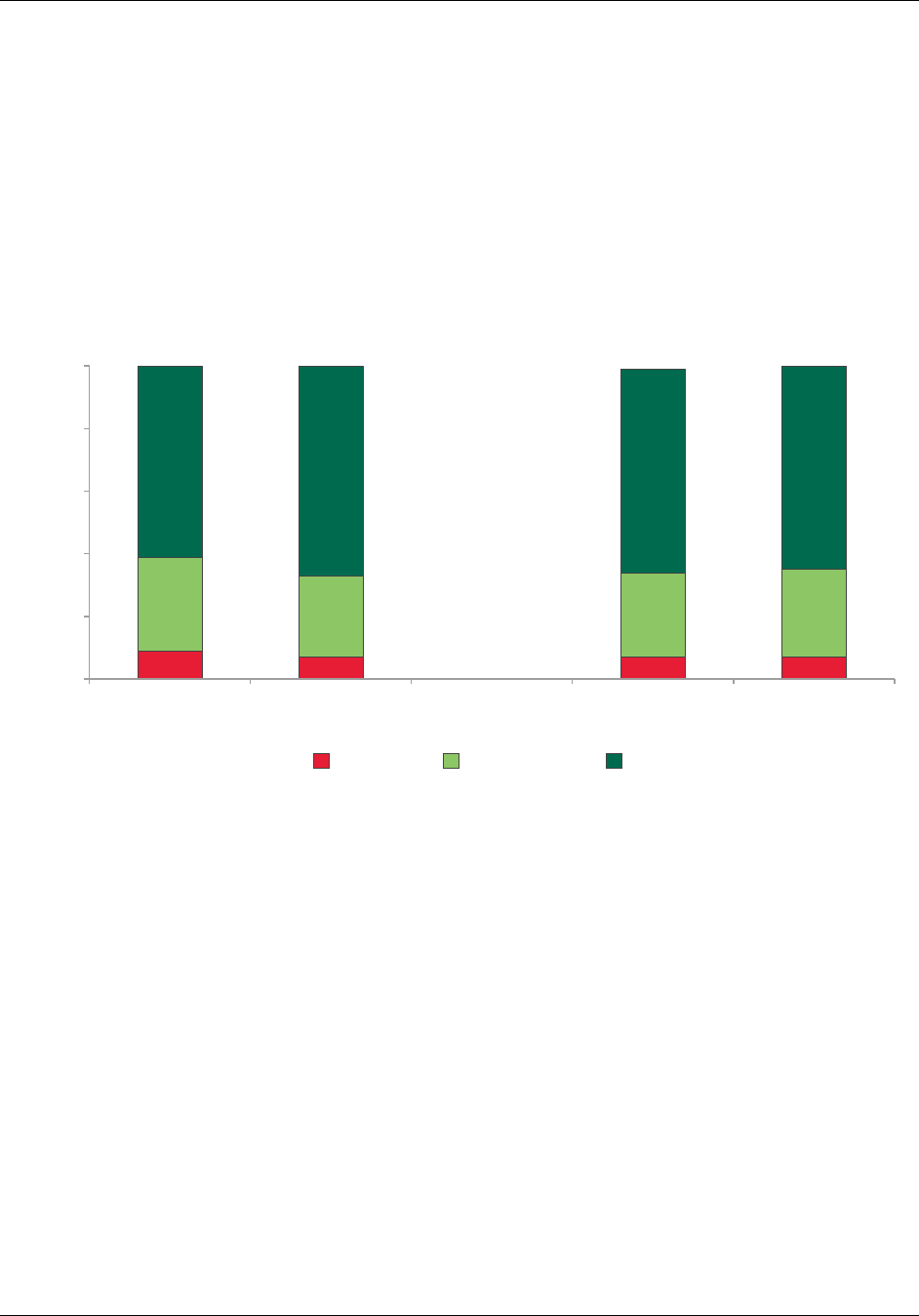

In 2016, 75 percent of practices CPC-wide rated their RLF as excellent (40 percent) or very

good (35 percent) at meeting their CPC-related needs. The proportion of practices that rated their

RLF as excellent, however, varied across regions and over time (Figure ES.3). Most notably,

RLF in Colorado consistently received some of the highest ratings, whereas New York RLF

generally received some of the lowest ratings, though their ratings still were fairly high.

Practices found that in-person learning activities and opportunities for peer-to-peer learning

were the most valuable forms of learning support, according to the practice survey and

interviews with deep-dive practices. Although practices valued learning, deep-dive practices also

indicated that finding time to participate in learning activities was challenging and some

activities (in particular, webinars) were repetitive or were not tailored to meet different practice

needs. Practices also noted that electronic health record (EHR) vendors did not participate in

learning activities and this limited practices’ ability to resolve EHR-related issues.

Although CPC provided a

variety of learning supports,

participating practices

found in-person learning

activities and opportunities

for peer-to-peer learning to

be the most valuable.

xxvi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

Figure ES.3. Percentage of CPC practices that rated their RLF as excellent or

very good at meeting their CPC-related needs, in PY2014 and PY2016, by

region

Source: CPC practice survey, administered April through July 2014 and April through August 2016.

ES.3. CMS and other payers formed collaborative relationships with each

other and with practices and other stakeholders to implement CPC

(Chapter 4)

CPC was one of the largest and most substantial multipayer initiatives ever tested. For the

initiative, CMS, state Medicaid agencies, and private payers committed to providing practices

enhanced payment to promote comprehensive primary care. Payers also agreed to work together

to develop an approach to align and coordinate data feedback for participating practices. This

work required a tremendous amount of coordination and collaboration among participating

stakeholders. By bringing together payers and other stakeholders, CPC enabled payers to

accomplish several collaborative outcomes, including aligning quality measures, goals, and

financial incentives; coordinating common approaches to data feedback; and coordinating CPC

with other regional efforts.

Most payers remained committed to CPC and actively engaged in collaborative discussions

for the duration of the initiative. Payers generally reported that they established productive,

positive working relationships with other payers in their region. According to payers, the

following factors facilitated collaboration: prior experience working together, strong facilitation

by a neutral payer convener, and leadership from payer champions who spearheaded

collaborative efforts and encouraged other payers to commit the needed time and resources to

accomplish goals.

From the start of the initiative, CMS encouraged payers to engage practices and patients or

patient advocacy groups in their collaborative work and, by PY2015, multistakeholder meetings

were the most common forum for discussing CPC. Most payers valued the opportunity to discuss

CPC with practices, and to hear more directly about the challenges and successes that practices

experienced in implementing the CPC requirements and transforming care. However, in several

regions, payers reported that active, sustained practice engagement in multistakeholder meetings

35

35

28

32

28

38

21

38

38

34

45

32

40

48

39

25

37

40

43

53

62

51

59

42

23

14

32

49

17

33

24

37

0

20

40

60

80

100

2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016 2014 2016

CPC-wide AR CO NJ NY OH/KY OK OR

Percentage of practices

Very good Excellent

xxvii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

was difficult to attain. Payers indicated that

multistakeholder meetings would have been more useful

if they had more clearly delineated goals for

engagement, focused on engaging stakeholders with the

time and skills needed to contribute to discussions, and

worked to build trust among payers and other

stakeholders earlier in the initiative.

Most payers viewed CMS as a critical partner in efforts

to transform primary care, recognizing its role in

encouraging practices to participate in transformation efforts and bringing additional financial and

technical support to each region. However, CMS’s dual role as initiative convener and

participating payer at times made collaboration challenging. CMS was able to build trust with other

payers over time by clarifying which parts of CPC could be adapted to regional contexts and

deferring to other payers for these decisions, increasing opportunities for payers to meet with CMS

representatives, and committing to build on the successes and lessons of CPC in CPC+.

ES.4. CPC changed how participating practices delivered care (Chapter 5)

CPC required participating practices to make many complex, interconnected changes in how

they deliver care to their patients, by focusing on five key functions: (1) access and continuity,

(2) planned care for chronic conditions and preventive care, (3) risk-stratified care management,

(4) patient and caregiver engagement, and (5) coordination of care across the medical

neighborhood. To promote progress on these functions, CMS specified a series of Milestones at

the start of CPC, and updated the Milestone requirements annually to build on practices’

progress in the prior year (Table ES.1). Some Milestones straddle more than one function.

Table ES.1. CPC Milestones for program year (PY) 2016

1. Budget. Complete an annotated annual budget with PY2015 revenues/expenses and projected

CPC initiative practice revenue flow for PY2016 at the start of the year and report actual

revenue/expenses for PY2016 at the end of the year.

2. Care management for high-risk patients. Maintain at least 95 percent empanelment to provider

and care teams. Continue to risk-stratify all patients, maintaining risk-stratification of at least 75

percent of empanelled patients. Expand care management activities for highest risk patients who

are likely to benefit from longitudinal care management and those not otherwise at high risk but

requiring episodic care management. Provide information about the care plans that are used for

both longitudinal care management and episodic care management. Maintain the implementation of

and further refine one of three strategies (behavioral health integration, medication management, or

self-management support).

3. Access by patients and enhanced access. Enhance patients’ ability to communicate 24 hours a

day, 7 days a week with a care team that has real-time access to their electronic medical records.

Continue to implement asynchronous forms of communication (for example, patient portal and

email) and ensure timely responses. Measure continuity of care by measuring visit continuity

quarterly for each provider and/or care team in the practice.

4. Patient experience. Assess patient experience through patient surveys or patient and family

advisory council meetings and communicate to patients (using electronic, poster, pamphlet, or

similar communication methods) about resulting changes the practice is making.

For successful multipayer

collaboration, it is important to clarify

the role of various stakeholders and

build trust among participants.

Adapting an initiative to regional

contexts, when possible, is also

useful in building support and gaining

buy-in from regional stakeholders.

xxviii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH

Table ES.1 (continued)

5. Quality improvement. Continue to perform continuous quality improvement using electronic health

record (EHR)-based clinical quality measures (eCQMs) on at least three of the measures that

practices report annually. Review at least one payer data feedback report (CMS Practice Feedback

Report or other payers’ reports) to identify a high-cost area and a practice strategy to reduce this

cost while maintaining or improving quality.

6. Care coordination across the medical neighborhood. Track patients by implementing two of

three options: follow up via telephone with patients within one week of emergency department (ED)

visits; contact at least 75 percent of hospitalized patients within 72 hours of discharge; and enact

care compacts with at least two groups of high-volume specialists.

7. Shared decision making. Use at least three decision aids to support shared decision making

(SDM) for three preference-sensitive conditions and track patient eligibility for and use of the aids.

8. Participating in learning collaborative. Participate in regional and national learning offerings and

communicate with regional learning faculty.

9. Health information technology (IT). Attest that each eligible professional in the practice is