Evaluation of Removal of the

Spare Room Subsidy

Final Report

December 2015

Research Report No 913

A report of research carried out by by the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning

Research and Ipsos MORI on behalf of the Department for Work

and Pensions.

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and

Pensions or any other government department.

© Crown copyright 2015.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium,

under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/

or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU,

or email: [email protected].uk.

This document/publication is also available on our website at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-work-pensions/about/

research#research-publications

If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email:

First published December 2015.

ISBN 978 1 911003 14 4

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and

Pensions or any other Government Department.

3

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Summary

This report presents ndings from the evaluation of the Removal of the Spare Room

Subsidy (RSRS) undertaken by Ipsos MORI and the Cambridge Centre for Housing and

Planning Research. The eldwork was carried out over the rst 20 months of implementation,

from April 2013 until November 2014. An interim report was published in July 2014.

The objectives of this project were to evaluate:

• The preparation, delivery and implementation of the policy changes by local authorities

and social landlords.

• The extent of increased mobility within the social housing sector leading to more effective

use of the housing stock.

• The extent to which as a result of the RSRS more people are in work, working increased

hours or earning increased incomes.

• The effects of the RSRS on, and responses to it of:

– Housing Benet (HB) claimants.

– Social landlords.

– Local authorities (LAs).

– Voluntary and statutory organisations and advice services.

– Funders lending to social landlords.

4

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Contents

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 10

The Authors

............................................................................................................................11

List of abbreviations............................................................................................................... 12

Glossary of terms

.................................................................................................................. 13

Executive summary

.............................................................................................................. 14

1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 21

1.1 Aims ...................................................................................................................... 21

1.2 Background ........................................................................................................... 21

1.3 Research methods ................................................................................................ 22

2 Implementation ................................................................................................................ 28

2.1 Numbers and prole of households affected ......................................................... 28

2.2 Degree of impact on landlords .............................................................................. 31

2.3 Administering the Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy ...................................... 32

2.3.1 Payment methods ................................................................................... 34

2.3.2 Communication between claimants, landlords and local authorities ...... 36

2.4 Administering Discretionary Housing Payments ................................................... 37

2.4.1 Discretionary Housing Payments in Scotland and Wales ....................... 38

2.4.2 Awarding Discretionary Housing Payments ............................................ 39

2.4.3 The role of landlords in supporting tenants to apply for Discretionary

Housing Payments .................................................................................. 40

2.4.4 Renewal and conditionality of Discretionary Housing Payments ............ 42

2.5 The costs of implementation ................................................................................. 44

2.5.1 The costs of implementation for local authorities .................................... 44

2.5.2 Costs for social landlords ........................................................................ 44

3 The response of claimants .............................................................................................. 47

3.1 Overall responses ................................................................................................. 47

5

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

3.1.1 Responses of claimants who were no longer affected ............................ 47

3.1.2 Responses of those who were still affected ............................................ 49

3.1.3 Comparing the responses of different groups ......................................... 50

3.2 Finding work or increasing incomes ...................................................................... 51

3.2.1 Support for nding work .......................................................................... 52

3.3 Moving to the private rented sector ....................................................................... 53

3.4 Claiming Discretionary Housing Payments ........................................................... 54

3.5 Taking in lodgers and family members .................................................................. 57

3.6 Paying the shortfall ................................................................................................ 58

3.6.1 How many were paying?......................................................................... 58

3.7 Managing on a lower budget ................................................................................. 61

4 Changes to the social housing stock ............................................................................... 65

4.1 Altering or reclassifying stock ................................................................................ 65

4.1.1 Altering stock .......................................................................................... 65

4.1.2 Reclassifying the number of bedrooms in properties .............................. 66

4.2 Allocations and lettings .......................................................................................... 67

4.2.1 Assessing the size of home required ...................................................... 69

4.2.2 Means testing housing applicants ........................................................... 70

4.2.3 Other changes to allocation policies ....................................................... 70

4.2.4 The impact of the changes to allocations on who can access social

housing ................................................................................................... 71

4.3 Downsizing ............................................................................................................ 72

4.3.1 Geographical variation in downsizing ..................................................... 75

4.3.1 Landlords’ role in facilitating downsizing ................................................. 76

4.3.2 Allowing downsizing with rent arrears ..................................................... 78

4.3.3 Demand for downsizing .......................................................................... 79

4.3.4 Barriers to downsizing............................................................................. 82

4.3.5 Claimants’ reasons for not wanting to downsize ..................................... 83

4.4 The impact on overcrowding ................................................................................. 86

4.5 Changes to demand for social housing ................................................................. 88

6

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

4.5.1 Managing turnover and voids.................................................................. 88

4.5.2 Shared housing ....................................................................................... 92

4.6 Changes to development plans ............................................................................. 95

4.7 Financing future development of social housing ................................................... 97

4.8 Rent collection and arrears ................................................................................... 98

4.9 Evictions and homelessness ................................................................................. 99

4.9.1 Evictions................................................................................................ 100

4.9.2 Homelessness services ........................................................................ 102

5 The impact on voluntary organisations, advice and support services ........................... 104

5.1 Overall impact ..................................................................................................... 104

5.2 Increasing work incentives .................................................................................. 106

6 Conclusions ................................................................................................................... 107

6.1 Implementation .................................................................................................... 107

6.2 The response of claimants .................................................................................. 108

6.3 Mobility and changing use of the housing stock .................................................. 109

Appendix A Claimant survey methods ................................................................................ 110

Appendix B Claimant survey – questionnaire .....................................................................118

Appendix C Qualitative claimant interviews – technical note ............................................. 141

Appendix D Landlord survey methods ............................................................................... 154

Appendix E Landlord survey .............................................................................................. 157

Appendix F Topic guides for case study work and lender interviews ................................ 167

List of tables

Table 2.1 Demographic prole of claimants (household heads) affected by the

RSRS ............................................................................................................... 30

Table 2.2 Which of the following best describes how you become aware when

tenants start or cease to be affected by the RSRS? ........................................ 33

Table 2.3 Which of the following payment methods have you encouraged for

your tenants to pay their rental shortfalls arising from the RSRS? .................. 35

Table 2.4 Has the total DHP funding (including any top up from the Scottish or

Welsh Government) been sufcient to allow DHP to cover the shortfalls

in full of all RSRS-affected tenants as long as they apply for it? ...................... 38

7

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Table 2.5 Which of the following best describes the system used most often for

assessing eligibility for DHP for your tenants? ................................................. 39

Table 2.6 In how many of the local authorities in which you work are you familiar

enough with the policy on DHP to advise tenants affected by the RSRS

as to whether they might be eligible? ............................................................... 40

Table 2.7 Do you have any other comments about DHP? ............................................... 42

Table 2.8 Case study landlords’ estimates of costs ......................................................... 45

Table 3.1 Overall responses to the RSRS among those still affected in autumn 2013

and summer 2014 ............................................................................................ 49

Table 3.2 Overall responses to the RSRS/actions taken by analysis groups since

autumn 2013 .................................................................................................... 50

Table 3.3 What proportion of your tenants currently affected by the RSRS are

currently in arrears/were in arrears on 31 March 2013? .................................. 60

Table 3.4 On which, if any, of the following things have you spent less since we

last spoke in October or November of last year because of the changes

to Housing Benet? .......................................................................................... 62

Table 3.5 Frequency with which claimants reported running out of money before

the end of the week or month at various stage before and since becoming

affected by the RSRS ....................................................................................... 63

Table 4.1 The original size of properties reclassied in response to the RSRS .............. 66

Table 4.2 Which of the following best describes your approach to reclassifying? ........... 67

Table 4.3 Which of the following best describes your approach to deciding/what

size of home to let to new tenants? .................................................................. 69

Table 4.4 Downsizing within the social rented sector ...................................................... 73

Table 4.5 Which two or three, if any, of these are the most important reasons you

have for staying here instead of moving elsewhere? ....................................... 84

Table 4.6 Void gures supplied by landlords .................................................................... 92

Table 4.7 Reasons for offering shared housing ............................................................... 93

Table 4.8 Reasons for not offering shared housing ......................................................... 94

Table 4.9 Total arrears held by landlords ......................................................................... 99

Table 4.10 Taking action against arrears. Of tenants affected by the RSRS: .................. 100

Table 4.11 Can I please check, are you currently up to date with the rent you owe,

or are you in arrears? ..................................................................................... 101

Table 4.12 Combined responses in both autumn 2013 and summer 2014 in

response to the question: Can I please check, are you currently up to

date with the rent you owe, or are you in arrears? ......................................... 101

Table 4.13 Claimants’ self-reported frequency of being in arrears at various points

before/since becoming affected by the RSRS................................................ 102

8

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Table A.1 Target and actual interviews by case study area ............................................112

Table A.2 Sampling Tolerances for wave 1 (autumn 2013) .............................................115

Table A.3 The prole of the affected cohort, waves 1 and 2 ...........................................116

Table D.1 The size of landlords responding to the survey .............................................. 154

Table D.2 Prole of social landlords responding to survey ............................................. 155

Table D.3 Social rented dwellings managed by location of landlord, and location

of social rented stock in Britain ...................................................................... 156

List of Figures

Figure 1.1 Analysis groups and their status in autumn 2013 and summer 2014 ............. 25

Figure 2.1 Numbers of households affected by the RSRS by month, as a proportion

of those initially affected in May 2013 ............................................................. 29

Figure 2.2 Change in the number of RSRS-affected tenants reported by landlords

April 2013 to October/November 2014 ............................................................. 32

Figure 2.3 Which of the following processes of applying for DHP apply to your

tenants? ........................................................................................................... 41

Figure 3.1 You told us that you are NOT CURRENTLY affected by the changes

to Housing Benet but were PREVIOUSLY affected/are no longer receiving

Housing Benet. From what you know or understand, why are you not

currently affected? ............................................................................................ 48

Figure 3.2 Thinking about the period since 1 April 2013, which of the following

statements best describes your situation in relation to Discretionary

Housing Payments (DHPs)? ........................................................................... 55

Figure 3.3 Proportion of tenants affected by the RSRS who have paid their rental

shortfall ............................................................................................................. 59

Figure 4.1 Have you made any changes to your allocations policy during the last

12 months to increase the priority given to potential downsizers? ................... 68

Figure 4.2 Proportion of new tenancies issued to households who are under

occupying in England ....................................................................................... 71

Figure 4.3 New tenancies issued to working-age households because of under

occupation by Housing Benet status in England ........................................... 74

Figure 4.4 Numbers of downsizers per 1,000 tenancies initially affected, by means

of downsizing and broad region where landlords stock is mostly located ........ 75

Figure 4.5 Is there a nancial incentive available to your tenants who wish to

downsize? ........................................................................................................ 77

Figure 4.6 Average size of landlords’ typical amount offered to downsizers ..................... 78

Figure 4.7 Do you allow tenants affected by the RSRS and with arrears to

downsize? ........................................................................................................ 79

9

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Figure 4.8 Combined responses in both autumn 2013 and summer 2014 in

response to the question: Are you currently looking to move from this

accommodation, or not? ................................................................................... 81

Figure 4.9 Moves within the social sector because of overcrowding in England .............. 87

Figure 4.10 Relets of social housing in England (i.e. lets excluding new build)

2013–14 by number of bedrooms .................................................................... 89

Figure 4.11 Have you experienced any difculties in letting properties as a result

of the RSRS? ................................................................................................... 90

Figure 4.12 Proportion of landlords reporting difculties letting as a result of RSRS

or Benet Cap who were experiencing difculties with each size and type

of property ........................................................................................................ 91

Figure 4.13 Do you offer shared housing (i.e. groups of unrelated adults/sharing a

house)? ............................................................................................................ 93

Figure 4.14 Ways in which landlords report having altered their development plans

as a result of the RSRS .................................................................................... 96

10

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions. The project

managers were Chris Lord, Graham Walmsley, Ailsa Redhouse and Claire Frew and input

was also received from Vicky Petrie, Simon Wheeldon, Andy Brittan and Preeti Tyagi.

The authors would also like to thank the local authority staff, housing associations, voluntary

and statutory agency staff, the Scottish SCORE team and Housing Benet claimants who

gave their time to participate in this research.

11

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

The Authors

Anna Clarke is a Senior Research Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Housing and

Planning Research (CCHPR) and has been responsible for the management of the local

case study work with landlords and agencies and the landlord survey. She has managed a

range of research projects in the eld of housing including past projects for the Department

for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) as well as work for housing associations on

welfare reform.

Lewis Hill is a Research Manager in Ipsos MORI’s Housing, Planning and Development

team. As part of this evaluation, he is Project Manager for the survey research with

claimants. He has managed a number of projects for Department for Work and Pensions

(DWP) on welfare reform, covering the Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy and the Benet

Cap.

Ben Marshall is Research Director at Ipsos MORI and Business Manager for the Housing,

Planning and Development team. He has designed and directed hundreds of projects for

government and public sector clients. He is Project Director for this evaluation for the DWP

and worked in a similar role within a consortium evaluating reforms to the Local Housing

Allowance in the private rented sector during 2011–13.

Michael Oxley is the Director of CCHPR. He was previously Professor of Housing at De

Montfort University and a Visiting fellow at Delft University of Technology. Mike has a strong

track record in the eld of housing and planning and an extensive publication list including

his book Economics, Planning and Housing.

Isabella Pereira is an Associate Director in Ipsos MORI’s Qualitative Social Research Unit

and managed the qualitative research with claimants. Isabella has worked on a number of

projects for DWP and other clients researching welfare reform and its impacts.

Eleanor Thompson is a Senior Research Executive in Ipsos MORI’s Employment, Welfare

and Skills team. On this study, she helped design and deliver the qualitative research with

claimants. She has experience on a number of qualitative depth interviewing projects,

including work for the Welsh Government.

Peter Williams was the Director of CCHPR until December 2013 and undertook the lender

interviews of this evaluation. His long career includes academia, government and industry

and has been Deputy Director General of the Council of Mortgage Lenders.

The research team also included Michael Jones, Ros Lishman, Sarah Monk and Christine

Whitehead.

12

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

List of abbreviations

CAB Citizens Advice Bureau

CAPI Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing

CORE Continuous Recording of Sales and Lettings

DCLG Department for Communities and Local Government

Defra Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

DHP Discretionary Housing Payments

DLA Disability Living Allowance

DWP Department for Work and Pensions

HB Housing Benet

LA Local authority

PIP Personal Independence Payment

PRP Private Registered Provider

PRS Private Rented Sector

PSU Primary Sampling Unit

RSRS Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy

SDR Statistical Data Return completed by English PRPs

SCORE Scottish Continuous Recording of Sales and Lettings

SHBE Single Housing Benet Extract (DWP’s Housing Benet

data)

UC

Universal Credit

13

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Glossary of terms

Affected claimant Housing Benet claimant affected by the Removal of the

Spare Room Subsidy (RSRS).

The Benet Cap

The Benet Cap, introduced in 2013 and limiting the total

amount of benets that most out of work working-age

households can receive. This is £500 a week for couples

and families and £350 a week for single people

Discretionary Housing

Payments awarded by local authorities when they

Payments (DHPs)

consider that a claimant requires further nancial

assistance towards housing costs. The DWP allocates

funding for DHPs to local authorities, who decide how to

allocate it and may also choose to top up the funding from

their own resources.

Housing Benet

Financial support paid to tenants (or to landlords on their

behalf) for those who are out of work or on low incomes

to help pay their rent. It can cover up to the entire value of

the rent, depending on the claimant’s circumstances and

income.

Private Registered

Housing Associations and other providers of social

Providers (PRPs)

housing registered with the Homes and Communities

Agency, but excluding local authorities

Social landlords

Landlords who manage social housing, including local

authorities, housing associations and other registered

providers.

14

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Executive summary

This report presents ndings from the evaluation of the Removal of the Spare Room

Subsidy (RSRS) undertaken by Ipsos MORI and the Cambridge Centre for Housing and

Planning Research. The eldwork was carried out over the rst 20 months of implementation,

from April 2013 until November 2014. An interim report was published in July 2014.

The objectives of this project were to evaluate:

• The preparation, delivery and implementation of the policy changes by local authorities

and social landlords.

• The extent of increased mobility within the social housing sector leading to more effective

use of the housing stock.

• The extent to which as a result of the RSRS more people are in work, working increased

hours or earning increased incomes.

• The effects of the RSRS on, and responses to it of:

– Housing Benet (HB) claimants.

– Social landlords.

– Local authorities (LAs).

– Voluntary and statutory organisations and advice services.

– Funders lending to social landlords.

Background

The RSRS was brought into effect on 1 April 2013. It entailed a reduction in HB for working-

age social tenants whose properties have more bedrooms than they need based on the

Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) size criteria (see below).

15

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

The number of bedrooms required is worked out so that no one has to share a bedroom

unless they are:

• A couple.

• Both aged under 10 years old.

• Both aged under 16 years old and of the same sex.

No more than two people should have to share any bedroom.

An additional bedroom is also allowed in certain circumstances for regular non-resident

overnight carers, foster carers, disabled children unable to share a bedroom and people

who are recently bereaved. Bedrooms used by students and members of the armed forces

are not counted as ‘spare’ if they are away and intend to return home.

Those deemed to have spare bedrooms have had their rent eligible for Housing Benet

reduced by:

• 14 per cent for one spare bedroom.

• 25 per cent for two or more spare bedrooms.

(Source: Wilson (2015) ‘Under-occupation of social housing: Housing Benet entitlement’

Department for Work and Pensions)

The DWP’s HB data show that in May 2013, 547,000 households

1

were affected by the

RSRS

2

, which equates to 11.6 per cent of all social tenancies. By November 2014, the number

had fallen to 465,000, a reduction of 14.2 per cent over the rst 18 months of the policy.

Research methods

The research methods comprised:

• Two separate surveys of social landlords throughout Britain. The rst of these ran between

October and November 2013, and the second a year later in October and November 2014.

A total of 312 landlords replied in full to the rst survey and the second survey had 256

responses. In both surveys the landlords answering the survey (between them) managed

a stock of around two million homes, over 40 per cent of the social housing stock in Britain.

• A longitudinal survey of Housing Benet claimants both affected and not affected by the

RSRS carried out across 15 local authorities (LAs) in autumn 2013 and summer 2014.

Face-to-face interviews were carried out with a total of 1,502 HB claimants in October and

November 2013, of whom two-thirds were currently affected by the RSRS according to

DWP’s Single Housing Benet Extract (SHBE) records. A follow-up survey was conducted

among 972 respondents between June and August 2014, split between:

1

Since HB is claimed on a family household basis, the term household has been used

interchangeably with claimant throughout this report.

2

Data from https://stat-xplore.dwp.gov.uk. DWP gures relate to the numbers on the

second Thursday of the month. Data for April were not available. The DWP’s data

from StatXplore include only people affected by the RSRS who were still in receipt of

at least some HB. Some people who would otherwise be eligible for partial HB have

been affected by the RSRS but are not recorded in the gures, because the RSRS has

reduced their HB award to zero. The DWP has not published any gures on the number

of people affected in this manner.

16

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

– respondents from the ‘affected cohort’, which included all those affected in the autumn

2013 survey. This group is split between those ‘still affected’ and those ‘no longer

affected’ by summer 2014; and

– respondents unaffected in autumn 2013 and still unaffected by summer 2014, agged as

‘never affected’.

See section 1.3 for more detailed information.

• Detailed qualitative interviews with 30 of the surveyed claimants affected by RSRS

were carried out in November 2013 in six of the 15 areas, with follow-up interviews

conducted between September and November 2014. Where possible, interviews were

conducted with the same participants from the rst wave of qualitative interviews, with

those who could not be re-contacted replaced by claimants of interest from the second

wave of the longitudinal survey.

• Case study work in ten local authority areas. This included group interviews carried

out with LA staff and social landlords in the summer of 2013 and again in early autumn

2014, and telephone interviews with a total of 47 local agencies across the ten areas in

the autumn of 2013 and again in autumn 2014, including Children’s Services, the Citizens

Advice Bureau, Job Centres and local voluntary organisations

3

.

• Interviews with eight of the major lenders to the housing association sector were

conducted during October 2013 and they were contacted again in October 2014.

• The DWP’s Local Authority Insight Survey. This was undertaken between October and

December 2013 and included questions added to assist this evaluation.

• Analysis of secondary data sources. This included data on social housing lettings

from CORE (Continuous Recording of Sales and Lettings, published by the Department

for Communities and Local Government (DCLG)) and SCORE (Scottish Continuous

Recording of Sales and Lettings, published by the Scottish Government) and DWP’s own

data

4

.

This report has drawn upon all these sources of information, using more than one source

where possible to increase the validity of the conclusions drawn.

3

LA staff interviewed included those involved in the administration of HB, as well as

strategic housing managers and (where applicable) those responsible for managing

social housing stock.

4

Department for Communities and Local Government. (2015). Continuous Recording

of Social Housing Lettings and Sales (CORE), 2007/08-2014/15: Special Licence

Access. [data collection]. 3rd Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 7604,

http://dx.doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7604-3.

17

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Key ndings

Implementation

• The DWP’s data shows a reduction in the number of households affected by the RSRS

from 547,000 to 465,000 by November 2014, a reduction of 14.2 per cent

4

. The greatest

falls were in London, followed by the North West and East of England (StatXplore).

• There was an increase in the average age of those affected by the RSRS during the period

of the research (StatXplore): partially explained by the rising pension age, but the research

suggested that changing allocation rules are likely to have reduced the number of younger

claimants (case study work) whilst younger claimants were also more likely to have found

work or otherwise ceased to be affected (claimant survey).

• A combined 46 per cent of those no longer affected said this was because of a change

in household composition or their/their children’s ages. One in ve (20 per cent) said they

found work or increased earnings and were no longer affected (claimant survey).

• The majority of claimants from the affected cohort were still affected nine months later

(claimant survey). Of those affected in autumn 2013, 17 per cent were no longer affected

by summer 2014 (claimant survey).

• A range of systems had been devised jointly by LAs and social landlords for keeping

landlords updated about which tenants were affected by the RSRS. Landlords working

across many areas were more likely to be having difculties in knowing which tenants

were affected (landlord survey).

• Among those claimants still affected by the RSRS in 2014, 29 per cent said they applied

for Discretionary Housing Payment (DHP) when asked what actions they had taken to

deal with being affected (claimant survey). Comparatively few still affected claimants

were successful with their application (36 per cent of those applying, 23 per cent of all still

affected) (claimant survey).

• Awareness of DHPs increased. Those who did not apply were asked if they had heard

of DHP – 52 per cent said they had, meaning 66 per cent in total of the still affected

claimants were aware of DHP by 2014, an increase from 49 per cent nine months

previously (claimant survey).

• Setting conditions on the receipt of DHP (e.g. job seeking or registering and/or bidding

for downsizing) was something that most LAs had developed over the course of the rst

year of the RSRS. LAs were becoming better at managing DHP and predicting levels of

demand (landlord survey and case study work).

• LAs were not excluding disability benets (Disability Living Allowance (DLA), or Personal

Independence Payment (PIP)) but considered both income and expenditure relating to

disabilities when they means test to assess eligibility for DHP. There was some confusion

amongst landlords about this (landlord survey and case studies).

4

This is a net reduction. The extent of ‘churn’ of households on and off being affected by

the RSRS is not known.

18

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

The response of claimants

• Seventeen per cent of claimants affected in autumn 2013 had ceased to be so by summer

2014 (claimant survey). The most common reasons for ceasing to be affected were nding

work/increasing earnings, a friend or relative moving in or a change in age of children

meaning they were no longer considered to have a spare bedroom (claimant survey).

• Twenty per cent of affected claimants say they have looked to earn more through

employment-related income as a result of the RSRS, rising to 63 per cent of those who

said they were unemployed and seeking work.

• Overall, ve per cent of respondents (or another adult in their household) in the initially

affected cohort found work between 2013 and 2014 – three per cent were still affected,

while for two per cent this meant becoming unaffected (claimant survey).

• Barriers to nding work or additional hours cited by participants included lack of

employment opportunities in the local area and employers being unable to offer additional

hours (claimant qualitative interviews).

• Most social landlords required permission for tenants to take lodgers, but only 0.3 per

cent of their affected tenants had asked for permission to take a lodger (landlord survey).

Seventeen per cent of no longer affected claimants reported the reason as being a friend

or relative moved in while two per cent said that a lodger had moved in.

• Around 12,000 RSRS-affected claimants nationally were estimated to have moved to the

private rented sector, less than 2.2 per cent

5

of affected tenants (landlord survey).

• The proportion of affected claimants who had paid all their rental shortfall rose from 41

per cent in 2013 to 50 per cent in 2014, whilst the proportion who had paid none of their

shortfall fell from 20 per cent to 10 per cent (landlord survey).

• Claimants who were still affected by the RSRS in 2014 were more likely than those no

longer affected to say they run out of money by the end of the week or month very/fairly

often (78 per cent compared with 69 per cent) (claimant survey).

• Among those still affected, claimants had paid the rent by: using up savings; borrowing

from family or friends or accruing debt (claimant qualitative interviews), although we do not

know whether they have a history of borrowing for other purposes.

• In the affected cohort cut backs were made on energy (46 per cent of those who had cut

back on spending), travel (33 per cent), food (76 per cent) and leisure costs (42 per cent)

(claimant survey and qualitative interviews).

• Overall 55 per cent of tenants affected by the RSRS were in arrears in autumn 2014,

though 43 per cent had been in arrears in March 2013 (prior to the introduction of the

RSRS) (landlord survey).

Changes to the social housing stock

• There is evidence of a declining proportion of lets to those who under occupy their new

home in England, and an increase in proportion of lets to families from 36.3 per cent in

2012–13 to 40.7 per cent in 2013–14 (CORE).

5

Precise percentage unknown due to ‘churn’ within the caseload.

19

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

• By autumn 2014, most landlords gave top priority to downsizers, with 57 per cent reporting

that they had increased the priority in response to the RSRS, but 20 per cent did not give

them top priority (landlord survey).

• The landlord survey suggests that nationally around 45,000 RSRS-affected claimants had

downsized within the social sector by autumn 2014, as compared with around 24,000 in

autumn 2013 (landlords surveys).

• In England the RSRS has resulted in a substantial increase in demand for downsizing,

compared to previous rates. The data shows a substantial increase in working-age tenants

moving within social housing via transfer lists because of under occupation from 2,755 per

year in 2009–10 (less than 0.5 per cent of all tenants) to 14,755 in 2013–14 (CORE).

• Landlords reported in autumn 2014 that around 16 per cent of affected tenants were

currently registered for downsizing – which would suggest that nationally around 87,000

tenants currently affected by the RSRS were seeking to downsize. This is a slight

reduction on the 19 per cent reported to be registered for downsizing at the time of the rst

survey (autumn 2013) (landlord surveys).

• Claimants’ reasons for not wanting to downsize were most often related to remaining close

to family, liking the area, good neighbourhoods, liking the accommodation, and particular

difculties for disabled tenants related to nding a property that meets their needs as well

as in packing and transporting belongings. For families with children, schools (48 per cent)

were the most important barrier to moving (claimant survey).

• Most LAs and social landlords reported that large numbers of people were unable to

move because of a shortage of smaller homes. Some claimants said they had not

registered because they were aware of the shortage (case studies and claimant qualitative

interviews).

• 42 per cent of landlords reported difculties in letting some properties because of the

RSRS. There was a strong correlation between the proportion of tenants affected by the

RSRS and reporting difculties in letting homes as a result. Fifty four per cent of landlords

with the highest proportion of tenants affected reported difculties letting, compared with

13 per cent of those with the lowest proportions (landlord survey).

• Data supplied by landlords does not provide evidence of any statistically signicant

increase in voids (landlord survey). There is some evidence of increased turnover since

the introduction of the RSRS in England, most notable for larger property sizes (CORE).

Case study evidence found that there were costs associated with the increased turnover

and reletting activity.

• Around half (51 per cent) of developing landlords said they have altered their build plans

as result of the RSRS, up from a third in 2013. They were building more one bedroom

homes and fewer larger ones. Some were concerned about the future of the policy at the

time of the eldwork and hence were reluctant to alter their stock prole (landlord survey).

• Lenders generally felt housing associations had responded well to RSRS and have put

resources in place. The RSRS was not thought to have impacted on the pricing of loans

made to the housing association sector. Their concerns were more focused on the wider

package of welfare reforms and Universal Credit rather than RSRS specically.

20

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

• There was no signicant change in levels of arrears held by social landlords between

autumn 2013 and autumn 2014 (landlord survey). Most landlords said they now

considered the affordability of the rent for prospective tenants before letting.

• 40 per cent of still affected claimants said they were currently in arrears in 2014, a slight

fall from 47 per cent in 2013 (claimant survey). Overall, the cause of arrears is uncertain

– as we cannot directly attribute increases in arrears to the RSRS. (The comparable

gures for non-affected claimants are 19 and 21 per cent respectively). Tenants with

arrears arising solely as a result of the RSRS were in most cases being supported and

encouraged to pay, or helped with the use of DHPs (case studies). The RSRS was

reported to have had some impact on homeless households seeking to move on from

temporary accommodation as it was now quicker to move families, due to larger properties

being freed up by downsizers, but conversely harder for singles who were now competing

with more households, including downsizers, for one bedroom properties.

• The research found no discernible increase in evictions arising from the RSRS at the time

of the autumn 2014 eldwork. Landlords reported having applied for possession on ve

per cent of RSRS-affected tenancies, though less than a tenth of this number have actually

been evicted (landlord survey). Case study work suggested most evictions by November

2014 had been of tenants with pre-existing arrears and/or who had not engaged with their

landlord (case studies). Most agencies reported an increase in demand for their services

from 2013, but the RSRS was one of several reasons for this and it was not possible to

clarify what specic impact it had, that might not be attributable to other welfare reforms

and economic changes. Agencies were concerned about the cumulative impact of welfare

reform, especially the RSRS and Council Tax liability (case studies).

21

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

1 Introduction

This nal report presents ndings from the evaluation of the Removal of the Spare Room

Subsidy (RSRS). The evaluation was led by Ipsos MORI and the Cambridge Centre for

Housing and Planning Research and the eldwork was carried out between April 2013 and

November 2014. The interim ndings were published in 2014

6

. The evaluation also examined

the impact of the Benet Cap within the social rented sector. The ndings from this strand of

the work were presented separately in the autumn of 2014

7

.

The focus of the evaluation is Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales).

1.1 Aims

This nal report presents the ndings from the study, covering the rst 20 months of

implementation from April 2013 to November 2014.

Assessing whether Housing Benet (HB) expenditure has fallen is being carried out by the

Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) separately, and does not lie within this evaluation.

The objectives of this evaluation were to explore:

• The preparation, delivery and implementation of the policy changes by local authorities

(LAs) (in their strategic housing role) and social landlords.

• The extent of increased mobility within the social housing sector leading to more effective

use of the housing stock with households in more suitable sized accommodation.

• The extent to which, as a result of the RSRS, more people are in work, working increased

hours or earning increased incomes.

• The effects of the RSRS, and responses to it by:

– Claimants.

– Social landlords.

– LAs.

– Voluntary and statutory organisations and advice services, including Children’s Services.

– Funders lending to social landlords.

1.2 Background

The RSRS was brought into effect on 1 April 2013. It entailed a reduction in HB for working-

age social tenants whose properties have more bedrooms than they are considered to need,

based on the DWP’s size criteria (see below).

6

See www.gov.uk/government/publications/removal-of-the-spare-room-subsidy-interim-

evaluation-report

7

See www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/le/386213/

supporting-households-affected-by-the-benet-cap.pdf

22

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

The number of bedrooms required is worked out so that no one has to share a bedroom

unless they are:

• A couple.

• Both aged under 10 years old.

• Both aged under 16 years old and of the same sex.

No more than two people should have to share a bedroom.

An extra bedroom was also allowed for:

• A non-resident overnight carer for the tenant or their partner.

• Foster carers who have fostered or become approved for fostering within the last year.

• A child whose disability or medical conditions means they cannot share a bedroom with

another child whom they would otherwise be expected to share with.

Bedrooms used by students and members of the armed forces are not counted as ‘spare’ if

they are away and intend to return home.

(Source: Wilson (2015) ‘Under-occupation of social housing: Housing Benet entitlement’

Department for Work and Pensions)

Those with one spare bedroom, according to the criteria, have had their rent eligible for HB

reduced by 14 per cent, whilst those with two or more spare bedrooms have had their rent

eligible for HB reduced by 25 per cent. People on partial HB will in some cases have ceased

to be eligible for HB as the reductions are applied to their eligible rent, not the actual amount

of HB previously received. The average reduction was projected to be around £14 (DWP,

2012

8

).

The DWP’s initial data on the impact of the RSRS shows that in May 2013, two-thirds of

tenants with one spare bedroom were seeing reductions of between £10 and £15 a week,

whilst 16 per cent had their HB reduced by under £10. For tenants with two or more spare

bedrooms, half were experiencing reductions of between £20 and £25, with 28 per cent were

seeing reductions of over £25

9

.

1.3 Research methods

There were six strands to this research:

• A survey of social landlords throughout Britain.

This survey ran between 16 October and 8 November 2013 and again between 13 October

and 7 November 2014. A total of 750 landlords were invited to take part in each survey,

comprising all stock-owning LAs and Private Registered Providers (PRPs) with over 1,000

properties, as well as a sample of smaller social landlords throughout Britain. A total of 312

responded to the rst survey and 256 to the 2014 survey.

8

DWP. (2012). Housing Benet: Under occupation of social housing Impact Assessment,

Department for Work and Pensions.

9

https://sw.stat-xplore.dwp.gov.uk

23

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

The survey asked for substantial numeric data relating to nances and numbers of affected

tenants. Landlords were instructed: “Draw on any data you hold wherever possible, but give

us your best estimate if not. Please leave blank any questions where you do not know the

answer, and cannot provide a good estimate either”.

The landlords who responded were representative of all social landlords in terms of their

spread between England, Scotland and Wales. In 2013, they had an average of 11.1 per

cent of their stock occupied by tenants affected by the RSRS, which was precisely the

national average as of August 2013. In 2014, the landlords answering the survey had 10.4

per cent of their stock occupied by tenants affected by the RSRS, very close to the national

gure of 10.0 per cent for August 2014. For further details, see Appendix D.

• A longitudinal survey of HB claimants both affected and not affected by the RSRS.

A total of 15 areas were selected for the purposes of undertaking primary survey research

among HB claimants in the social rented sector. These covered England (13 areas),

Scotland and Wales (one area each) and were chosen to ensure a range of housing market

circumstances, region, tenure mix, type and size of LA throughout Britain. This was not

designed to be representative in any statistical sense – and should not be considered as

such, but rather to ensure coverage of a mixture of stock-owning and non-stock owning, rural

and urban and unitary and district authorities.

Table 1.1 below shows key statistics of the 15 case study areas, as compared to the national

average:

Table 1.1 Key statistics of the 15 case study areas

15 case study areas Britain

Proportion where LA owns stock 60% 53%

Proportion rural (Defra class 4–6) 40% 51%

Mean % private rented sector tenants 19% 16%

Average overcrowded households per 100 households 5 4

Mean proportion social sector with 1–2 rooms 10% 11%

Mean estimate of proportion of tenants affected by RSRS 15% 14%

Source: 2001 and 2011 Censuses, Defra, Scottish Government and Welsh Government websites;

Estimate of proportion affected by RSRS modelled from DWP impact assessment.

10

In order to encourage frank and open discussion, the case study authorities in which

eldwork was undertaken (via the claimant survey and case study work) were selected on

the basis of guaranteeing anonymity; they have not been identied in this report.

The survey of claimants was a longitudinal one, that is to say interviewers returned to the

same respondents to research how things had changed (according to what they think had

changed and by comparing their responses between the two waves). This is distinct from

a cross-sectional study in which two matched but separate samples are built in order to

10

DWP. (2012). Housing Benet: Under occupation of social housing Impact Assessment,

Department for Work and Pensions. The Impact Assessment provided estimates of the

likely number of affected claimants by region. These were used to estimate the likely

proportion of tenants who would be affected in each region, (as the actual numbers by

LA were not known at the time of selecting case studies.

24

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

compare or detect changes with weighting applied to the two samples (if necessary) to be

sure that any differences are ‘real’ and not simply the product of variation in the samples.

Since, in this nal report, the focus has been undertaking longitudinal analysis, the data used

is unweighted. For further information about this, please see Appendix A.

The rst (autumn 2013) wave of research ran between 1 October and 24 November 2013,

following a small-scale pilot survey conducted in September. The sample was drawn from

the May 2013 Single Housing Benet Extract (SHBE), which agged claimants as either

‘affected’ or ‘non affected’ by the RSRS at the point the extract was compiled. Ipsos MORI

interviewed 100 claimants face-to-face in their homes in each area. Sampling and quotas

were structured to achieve interviews with affected claimants in a 70:30 ratio of affected to

non-affected claimants at both local and aggregate levels.

In total, 1,071 affected HB claimants were interviewed plus a non-affected sample of 431 HB

claimants. For analysis purposes, ndings focus on the 871 claimants agged in the May

2013 SHBE extract as affected by the changes

11

and who said they were currently affected

by the changes and that their Housing Benet has been reduced (‘affected’), and on the 381

claimants agged as not affected in the May 2013 SHBE extract and who said they were not

currently affected by the changes (‘non-affected’).

12

The second (summer 2014) wave of research ran between 16 June and 4 August 2014.

Ipsos MORI completed interviews with 972 respondents who took part in the autumn 2013

survey. Reecting the longitudinal nature of the survey, the focus of analysis in this report is

on certain types of claimant based on their longitudinal status at wave one and wave two:

1

Those in the autumn 2013 survey recontacted in 2014 who were agged as affected by

the changes in the May 2013 SHBE extract and who said they were ‘currently affected

by the changes and Housing Benet has been reduced’ (called the ‘affected cohort’).

Of these:

2

those who were still affected in 2014 (‘I am currently affected by these changes and my

Housing Benet has been reduced’), including those receiving Discretionary Housing

Payment (DHP) to cover the shortfall (referred to as ‘still affected’);

3

those who say they were no longer affected by 2014 (‘I am not currently affected by these

changes, but I have been previously’) (‘no longer affected’); and

4 those who were unaffected in autumn 2013 and remain unaffected in 2014 (‘I am not

currently affected by these changes and never have been’) (‘never affected’, or the

‘comparison group’)

The diagram in Figure 1.1 shows the movement of the four groups of interest between the

two waves of research.

11

This was derived from SHBE eld 21 – ‘the weekly amount of social sector size criteria/

under-occupation deduction’.

12

This allows greater certainty, but relies on respondent recall/reporting (and does not

provide precise validation of the SHBE ag). We detected some confusion on the issue

– for example, of the 1,502 taking part in the survey, 180 agged as affected by SHBE

said that their HB had not been reduced. A further 32 agged as not affected by SHBE

said that their HB had been reduced, while 10 said they believed they were affected but

their HB had not been reduced. A further 28 were unsure of their current status.

25

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Figure 1.1 Analysis groups and their status in autumn 2013 and summer 2014

13

Focusing on these groups allows a comparison of the behaviours/responses to RSRS

among those who remained under occupiers and those who were no longer under

occupying, as well as comparing against the group of claimants who were never under

occupying/affected.

For further details on methods and the interview schedule used, see Appendix A.

• Follow-up qualitative interviews with 30 claimants affected by the RSRS

In addition to the survey of claimants, 30 in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted in

autumn 2013 among those affected by RSRS (who had taken part in the original survey).

Respondents were chosen based on a range of demographic characteristics to ensure a

cross-section of affected claimants was interviewed. Interviews were conducted in six of

the 15 areas (four in England, one in Wales, one in Scotland) to ensure the inclusion of a

diverse selection of case study areas

These claimants were contacted again to take part in a follow-up interview in autumn

2014. Of the 30 who took part in autumn 2013, 22 were interviewed again in autumn 2014.

Eight interviews were conducted with claimants who had taken part in the survey but had

not taken part in the qualitative interviews in autumn 2013. These claimants were again

selected to reect a range of demographic characteristics and who had pursued diverse

responses to the RSRS.

Further details about the qualitative interviews can be found in Appendix C.

13

Please note that the ‘affected cohort’ grouping is placed across the affected/not affected

line to reect the proportion of respondents within this group who are no longer

affected.

Autumn 2013

(Wave one)

Summer 2014

(Wave two)

Affected by the RSRS

‘Affected cohort’

(n=563)

Not affected by the RSRS

Comparison

group (never

affected)

(n=204)

‘Affected cohort’

(n=563)

Comparison

group (never

affected)

(n=204)

‘Still affected’

(n=469)

‘No longer

affected’

(n=94)

26

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

• The qualitative ndings described in this report include some indications of the prevalence

of views or experiences across the sample or within subgroups, presented through the

use of words such as ‘most’, ‘many’ and ‘few’ to describe how typical views or experiences

were across the relevant group. This should be considered indicative rather than exact

due to the nature of qualitative research which is not intended to give a statistical measure

of the prevalence of different views. Rather, qualitative research is designed generate

detailed and exploratory accounts, provides insight into the perceptions, experiences and

behaviours of participants.

• Case study work in ten local authority areas.

The ten case study LAs were chosen to reect a range of housing market circumstances.

Nine of the ten areas were chosen from within the 15 areas selected above

14

. Group

interviews were held between May and August 2013 in each location with between two

and ten LA staff in attendance at each interview and these same people were interviewed

again by telephone in September 2014. In total, 26 landlords were interviewed by telephone

in summer 2013 and again a year later. These landlords between them held 89 per cent

of the housing stock in the case study areas, around 186,000 properties. Interviews were

also conducted in November 2013 and again in October 2014 with a total of over 50 local

agencies and LA departments across the ten areas, including Children’s Services, the

Citizens Advice Bureau, Job Centres and local voluntary organisations. One LA and one

housing association who both took part in 2013 declined to participate in 2014 and one

(different) housing association had declined in 2013 but agreed to participate in 2014.

The topic guides used are provided in Appendix E.

• Interviews with eight of the major lenders to the social housing sector in the UK.

Eight interviews were conducted during October 2013, and six lenders provided written

responses to questions in October 2014. In 2013, the six largest lenders were all included,

along with two others both of whom were selected because they were recent entrants to

the sector lending to housing associations. In 2014, the same lenders were contacted

again, along with others by open invitation via the Council of Mortgage Lenders’ Social

Housing Panel. This panel includes most of the lenders to the housing association sector

in the UK. Thus, although it is not a full survey of the market, the coverage does provide a

useful snapshot of views in October 2014.

• The DWP’s Local Authority Insight Survey.

The DWP carry out a survey of all LAs every six to 12 months, known as the Local

Authority Insight Survey’ (formally the Omnibus Survey)

15

. The autumn 2013 survey

ran from October to December 2013 and included questions added to contribute to this

evaluation. The questions added covered:

14

The intention had been to choose just nine from within the 15 selected for claimant

interviews, but one case study area was found not to have adequate SHBE data and

therefore was no longer suitable for claimant interviews. It was therefore decided to

include an additional tenth case study area – nine from the 15, as planned, as well as

continuing eldwork in the tenth one where claimant interviews could not be carried out.

15

For further information about the Local Authority Insight Survey see

www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-authority-insight-survey-wave-24-rr847

27

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

• DHPs and their use in relation to people affected by the RSRS.

• HB advice given to people affected by the RSRS.

• Communication with claimants affected by the RSRS.

• Whether the numbers affected had increased or decreased and perceived reasons for any

decrease.

• Other comments on the RSRS.

This report has drawn upon all these sources of information and used triangulation methods

which involve using information from more than one source wherever possible in order to

cross-check and increase the validity of the conclusions drawn.

28

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

2 Implementation

This section reports on the implementation of the Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy

(RSRS) during its rst 20 months of operation, until autumn 2014. The Interim Report of July

2014 covered preparedness and initial implementation of the RSRS. The second round of

eldwork in autumn 2014 focused on ongoing issues of communication between landlords

and local authorities (LAs), emerging staff training needs and ongoing communication with

claimants.

2.1 Numbers and prole of households affected

Key ndings

• The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP’s) data shows a reduction in the

number of households affected by the RSRS from 547,000 to 465,000 by November

2014, a reduction of 14.2 per cent

16

. The greatest falls were in London, followed

by the North West and East of England (StatXplore).There was an increase in

the average age of those affected by the RSRS during the period of the research

(StatXplore). This is partially explained by the rising pension age, but the research

suggested that changing allocation rules are likely to have reduced the number of

younger claimants (case study work) whilst younger claimants were also more likely

to have found work or otherwise ceased to be affected (claimant survey).

• The large majority of claimants from the affected cohort were still affected nine

months later (claimant survey). Of those affected in 2013, 17 per cent were no longer

affected by autumn 2014 (claimant survey).

• Those no longer affected were more likely to be younger and more likely to be in

households with young children (StatXplore).

• A combined 46 per cent of those no longer affected said this was because of a

change in household composition or their/their children’s ages. One in ve (20

per cent) said they found work or increased earnings and were no longer affected

(claimant survey).

The DWP’s data show that in May 2013 a total of 547,341 households were affected across

Britain, falling to 471,887 by August 2014, a reduction of 13.8 per cent over the rst 16

months of the policy. There were variations between LAs in the degree of the reduction, but a

net reduction was found in every single LA in Britain. A higher reduction was seen in England

(14.8 per cent) than in Wales (12.6 per cent) or Scotland (8.9 per cent).

Figure 2.1 shows how this reduction has occurred across the different parts of Britain.

16

This is a net reduction. The extent of ‘churn’ of households on and off being affected by

the RSRS is not known.

29

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

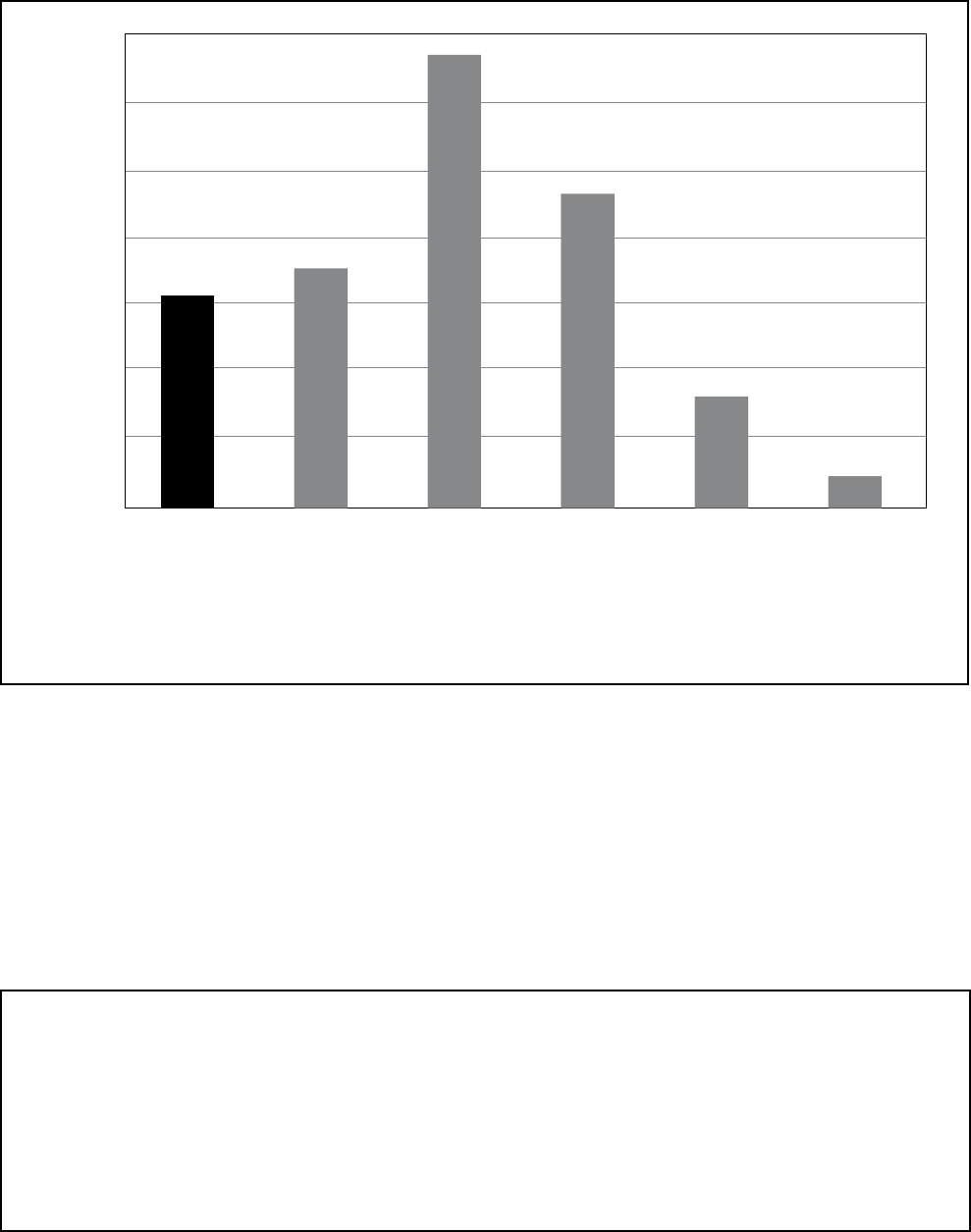

Figure 2.1 Numbers of households affected by the RSRS by month, as a proportion

of those initially affected in May 2013

17

17

The apparent rise in June 2013 in some regions is related to missing data from May

2013 in some authorities. No data has been published from April 2013. The fall of

around 2,000 in February 2014 and subsequent rise back up in March would appear

most likely related to the closing of the loophole that had excluded people with claims

running continually from prior to 1996.

Percentages

Source: DWP, StatXplore.

North East

North West

Yorkshire and

The Humber

East Midlands West Midlands

East of

England

London

0

20

40

60

80

100

2013 2014

May

June

July

August

September

November

October

December

May

June

July

August

January

February

March

April

30

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

Proportionally the greatest falls in the number of claimants affected between May 2013 and

August 2014 occurred in London (a 19 per cent fall), followed by the North West and East of

England (both 17 per cent). Overall, the reduction in numbers happened mainly in the rst

few months of implementation, falling by ve per cent between May and August 2013.

The

numbers fell by a further nine per cent in the following 12 months (August 2013 to August

2014). With the exception of the North W

est, the reductions have been highest in the regions

where the smallest proportions of social tenants were affected by the RSRS.

The DWP data also show the differential impact on age groups, with the number of young

people affected having reduced by 29 per cent, as compared to a rise of 28 per cent for

the over 60s. This is most likely related to the changes in allocation systems reducing the

proportion of new lets to under occupying tenants (who are most likely to be young) and

the increase in the upper age limit for being affected by the RSRS, in line with increases in

women’s pension age (Table 2.1):

Table 2.1 Demographic prole of claimants (household heads) affected by the

RSRS

Characteristic May 2013 August 2014 Reduction

Age of claimant Under 25 24,843 17,615 29.1%

25 to 34 82,044 65,528 20.1%

35 to 44 110,736 87,765 20.7%

45 to 49 93,972 78,152 16.8%

50 to 54 102,883 91,581 11.0%

55 to 59 100,931 90,654 10.2%

60 to 64 31,723 40,582 -27.9%

Unknown 206 11 94.7%

Number of

dependent children

0 387,755 341,258 12.0%

1 83,500 68,470 18.0%

2 66,055 54,132 18.1%

3 5,926 4,776 19.4%

4 3,519 2,825 19.7%

5+ 584 436 25.3%

Total 471,887 547,341 13.8%

Source: DWP, StatXplore.

Table 2.1 also shows a reduction in the proportion of affected households who have children.

This may be related to the greater availability of suitable stock for downsizing for those in

need of two or more bedrooms, though may also be partially accounted for by the increased

numbers of over 60s affected, who are less likely to have dependent children.

These gures are net gures; it is not possible to tell from this data alone whether it is the

same households affected by August 2014 as were affected in May 2013, due to the churn

in the Housing Benet (HB) caseload. It is likely that somewhat more than 13.8 per cent of

initially affected tenants had ceased to be so by August 2014, whilst some other tenants are

likely to have also become affected during this period.

31

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

The claimant survey provided self-reported outcomes for those who were affected at the start

of the policy. It found that the large majority (82 per cent) of claimants from the affected cohort

of respondents in autumn 2013 were still affected by summer 2014. Among this group, 17 per

cent said they were no longer affected (but had been previously), while one per cent said they

were unsure (but for the purposes of the analysis were treated as still affected).

The survey also found relatively little movement in and out of being affected by the RSRS

between autumn 2013 and summer 2014. Almost all claimants still affected by the policy

said they became affected at its inception and had been affected ever since. Some 97 per

cent said they had been affected since 1 April 2013 (as one might expect given the original

sample for the autumn 2013 survey was drawn from the May 2013 SHBE extract). A similarly

high proportion (94 per cent) said they had been affected consistently during that time,

though a small proportion (6 per cent) said they had been affected at some times since 1

April 2013 but not at others.

The majority of still affected claimants had their HB reduced by between £10 and £15 per

week (38 per cent) or more than £15 per week (43 per cent), with many uncertain about

the amount by which their HB had been reduced (16 per cent). Those with three or more

bedrooms in their property were far more likely to pay more than £15 per week of their rent

(55 per cent of them did so).

In line with the caseload analysis (but keeping in mind the smaller base size of this sub-

group of the affected cohort), those no longer affected by the RSRS were much more likely

to be in families with at least one child under 16 (54 per cent compared with 27 per cent of

those still affected).

They were also likely to be younger; 53 per cent of respondents no longer affected were

45 or older compared with 71 per cent of those who were still affected. However, those still

affected (75 per cent) were more likely to report having someone in their household with

long-term health problems than those no longer affected (62 per cent).

2.2 Degree of impact on landlords

Key ndings

• The overall proportion of tenancies affected fell from 11.5 per cent to 10.0 per cent by

autumn 2014 (various data sources). The landlord survey found substantial variation

between landlords in the degree of impact with the proportion of tenants currently

affected ranging from two per cent to 48 per cent.

• Most social landlords saw a reduction in the proportion of tenancies affected during the

rst 18 months of operation, some of over 40 per cent, but 16 per cent of landlords saw

an increase (landlord survey).

The impact of the RSRS on social landlords varied between areas and between landlords.

Overall, the proportion of tenants affected fell from 11.5 per cent of tenancies in April 2013

to 10.0 per cent (10.4 per cent among for landlords answering the survey) by August 2014

18

.

The reduction, however, varied considerably with some landlords seeing a reduction of over

40 per cent and others seeing an increase of up to 28 per cent (Figure 2.2).

18

Sources: 2011 Census on stock size, and DWP StatXplore on claimants affected by

RSRS.

32

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

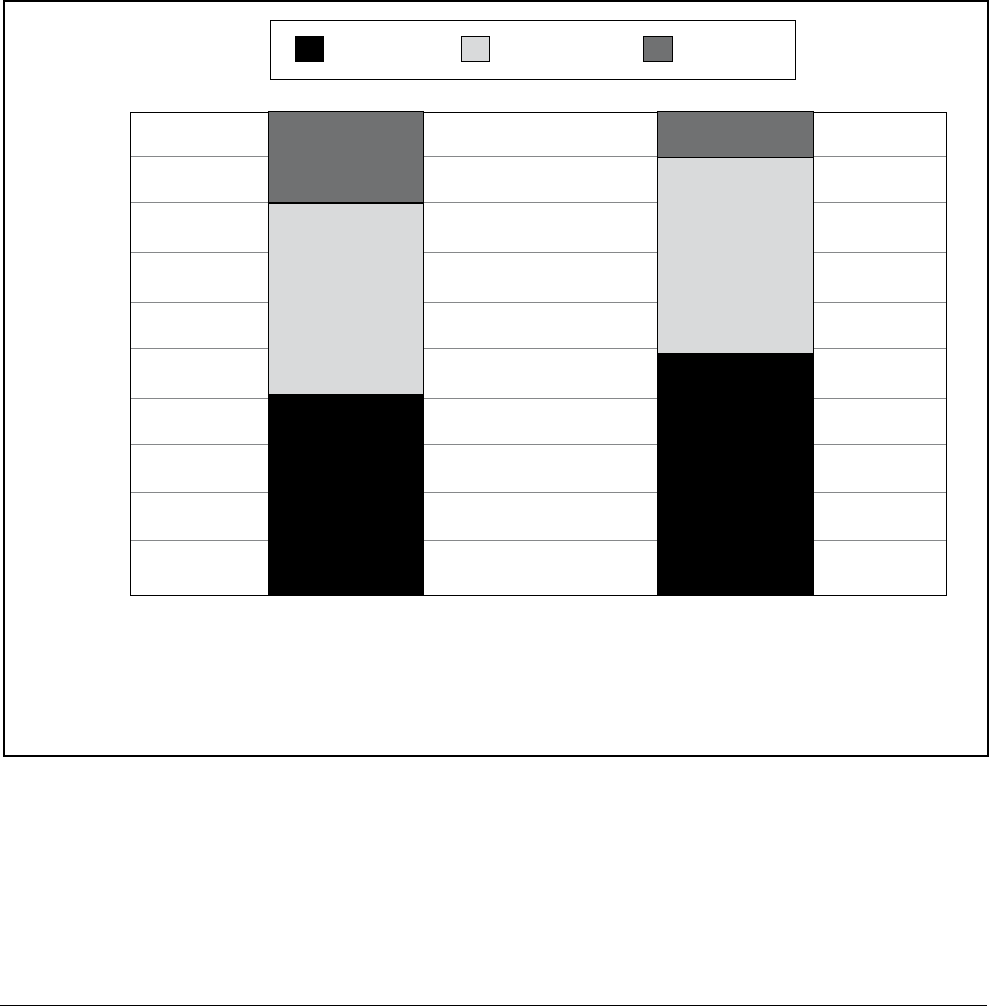

Figure 2.2 Change in the number of RSRS-affected tenants reported by landlords

April 2013 to October/November 2014

Overall the proportion of tenants affected ranged from two per cent to 48 per cent. Amongst

landlords with over 1,000 general needs properties, the proportions ranged from two per cent

to 34 per cent, which is likely to reect their stock prole and historic allocation practices; for

further details see Chapter 4.

2.3 Administering the Removal of the Spare

Room Subsidy

Key ndings

• A range of systems had been devised jointly by LAs and social landlords for keeping

landlords updated about which tenants were affected by the RSRS.

• Most landlords were, by autumn 2014, informed regularly but a minority were informed

less than monthly (15 per cent) or not at all (8 per cent).

• Landlords working across many areas were more likely to be having difculties in

knowing which tenants were affected.

Increase

Proportion of landlords

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0–10%

decrease

10–20%

decrease

20–30%

decrease

30–40%

decrease

40%

decrease

Change in number of RSRS-affected tenants

Base: All Landlords n=256. Fieldwork Dates: 13 October to 7 November 2014.

Source: CCHPR/DWP.

33

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report

In 2013, the landlord survey found that around a quarter of landlords were not informed

regularly when tenants started or ceased to be affected by the RSRS. The 2014 survey

found that these gures had changed little (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Which of the following best describes how you become aware when

tenants start or cease to be affected by the RSRS?

System 2013 2014

Number Proportion Number Proportion

We have access to the local authority HB

database so we can see for ourselves

42 14% 31 12%

The local authority informs us on a case by

case basis when people start or cease to be

affected

45 15% 20 8%

The local authority informs us on a regular

basis (at least monthly)

43 14% 41 16%

The local authority informs us but less often

than monthly

34 11% 29 11%

We do not get informed by the LA reliably

so rely on the tenant telling us directly

44 14% 38 15%

Other (please explain) 90 29% 21 8%

A mixture of the above 8 3% 75 29%

Total 306 100% 255 100%

Base: All Landlords (2013 n=306; 2014 n=255). Fieldwork Dates: 16 October to 8 November 2013

and 13 October to 7 November 2014. Source: CCHPR/DWP.

Landlords with dispersed stock reported more difculties in nding out when tenants started

or ceased to be affected. Stock-owning LAs were generally able to access the HB database