FREE TRADE

AGREEMENTS

U.S. Partners Are

Addressing Labor

Commitments, but

More Monitoring and

Enforcement Are

Needed

Report to Congressional Requesters

November 2014

GAO-15-160

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-15-160, a report to

congressional requesters

November 2014

FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS

U.S. Partners Are Addressing Labor Commitments,

but More Monitoring and Enforcement Are Needed

Why GAO Did This Study

The United States has signed 14 FTAs,

liberalizing U.S. trade with 20 countries.

These FTAs include provisions regarding

fundamental labor rights in the partner

countries. USTR and DOL, supported by

State, are responsible for monitoring and

assisting FTA partners’ implementation of

these provisions.

GAO was asked to assess the status of

implementation of FTA labor provisions in

partner countries. GAO examined (1)

steps that selected partner countries

have taken, and U.S. assistance they

have received, to implement these

provisions and other labor initiatives and

the reported results of such steps; (2)

submissions regarding possible violations

of FTA labor provisions that DOL has

accepted and any problems related to

the submission process; and (3) the

extent to which U.S. agencies monitor

and enforce implementation of FTA labor

provisions and report results to

Congress. GAO selected CAFTA-DR and

the FTAs with Colombia, Oman, and

Peru as representative of the range of

FTAs with labor provisions, among other

reasons. GAO reviewed documentation

related to each FTA and interviewed

U.S., partner government, and other

officials in five of the partner countries.

What GAO Recommends

DOL should reevaluate its submission

review time frame and better inform

stakeholders about the submission

process. USTR and DOL should

establish a coordinated strategic

approach to monitoring and enforcement

labor provisions. USTR’s annual report to

Congress should include more

information of USTR’s and DOL’s

monitoring and enforcement efforts. The

agencies generally agreed with the

recommendations but disagreed with

some findings, including the finding that

they lack a systematic approach to

monitor and enforce labor provisions in

all FTAs. GAO stands by its findings.

What GAO Found

Partner countries of free trade agreements (FTA) that GAO selected—the Dominican

Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) and the

FTAs with Colombia, Oman, and Peru—have taken steps to implement labor provisions

and other initiatives to strengthen labor rights. For example, U.S. and foreign officials said

that El Salvador and Guatemala—both partners to CAFTA-DR—as well as Colombia,

Oman, and Peru have acted to change labor laws, and Colombia and Guatemala have

acted to address violence against union members. Since 2001, U.S. agencies have

provided $275 million in labor-related technical assistance and capacity-building activities

for FTA partners, including $222 million for the four FTAs GAO reviewed. However, U.S.

agencies reported, and GAO found, persistent challenges to labor rights, such as limited

enforcement capacity, the use of subcontracting to avoid direct employment, and, in

Colombia and Guatemala, violence against union leaders.

Since 2008, the Department of Labor (DOL) has accepted five formal complaints—known

as submissions—about possible violations of FTA labor provisions and has resolved one,

regarding Peru (see fig.). However, for each submission, DOL has exceeded by an

average of almost 9 months its 6-month time frame for investigating FTA-related labor

submissions and issuing public reports, showing the time frame to be unrealistic. Also,

union representatives and other stakeholders GAO interviewed in partner countries often

did not understand the submission process, possibly limiting the number of submissions

filed. Further, stakeholders expressed concerns that delays in resolving the submissions,

resulting in part from DOL’s exceeding its review time frames, may have contributed to the

persistence of conditions that affect workers and are allegedly inconsistent with the FTAs.

Five Labor Submissions Accepted by DOL Regarding Free Trade Agreements

In 2009, GAO found weaknesses in the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s (USTR)

and DOL’s monitoring and enforcement of FTA labor provisions. In the same year, the

agencies pledged to adopt a more proactive, interagency approach. GAO’s current review

found that although the agencies have taken several steps since 2009 to strengthen their

monitoring and enforcement of FTA labor provisions, they lack a strategic approach to

systematically assess whether partner countries’ conditions and practices are inconsistent

with labor provisions in the FTAs. Despite some proactive steps, they generally rely on

labor submissions to begin identifying, investigating, and initiating steps to address

possible inconsistencies with FTA labor provisions. According to agency officials, resource

limitations have prevented more proactive monitoring of all FTA labor provisions. As a

result, USTR and DOL systematically monitor and enforce compliance with FTA labor

provisions for only a few priority countries. USTR’s annual report to Congress about trade

agreement programs provides limited details of the results of the agencies’ monitoring and

enforcement of compliance with FTA labor provisions.

View GAO-15-160. For more information,

contact Kimberly Gianopoulos at (202) 512-

8612 or

gianopoulosk@gao.gov.

Page i GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Letter 1

Background 5

Selected Countries Have Taken Steps, with U.S. Assistance, to

Address FTA Labor Commitments and Other Labor Initiatives

but Have Limited Enforcement Capacity 10

One of Five Labor Submissions Has Been Resolved, but

Reporting Deadlines and Limited Public Awareness of the

Process Present Problems 23

U.S. Agencies Provide Limited Monitoring, Enforcement, and

Reporting on FTA Labor Provisions 32

Conclusions 46

Recommendations for Executive Action 47

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 47

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 50

Appendix II Reported Violence against Trade Unionists in Colombia and

Guatemala 55

Appendix III U.S. Monitoring of Implementation of Other Labor Initiatives 65

Appendix IV Status of Labor Submissions 69

Appendix V Comments from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative 77

Appendix VI Comments from the Department of Labor 92

Appendix VII GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 96

Contents

Page ii GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Figures

Figure 1: Labor-Related Technical Assistance Administered by

U.S. Agencies under Selected Free Trade Agreements

(FTA) and All Other FTAs 16

Figure 2: U.S. DOL Labor Submission Process 24

Figure 3: Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Labor Submissions

Accepted by DOL as of July 2014 26

Figure 4: Murders of Unionists in Colombia, 2003-2013 56

Figure 5: Timeline and Status of Labor Submission Regarding

Bahrain 70

Figure 6: Timeline and Status of Labor Submission Regarding the

Dominican Republic 72

Figure 7: Timeline and Status of Labor Submission Regarding

Guatemala 74

Figure 8: Timeline and Status of Labor Submission Regarding

Honduras 75

Figure 9: Timeline and Status of Labor Submission Regarding

Peru 76

Page iii GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Abbreviations

AFL-CIO American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial

Organizations

CAFTA-DR Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free

Trade Agreement

CICIG International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala

DOL Department of Labor

DPPS División de Protección de Personas y Seguridad

DRL Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

ENS Escuela Nacional Sindical

FTA free trade agreement

ILO International Labour Organization

INL Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement

NAFTA North American Free Trade Agreement

NGO nongovernmental organization

SENA Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje

SINAUT National Union of Tax Administration Workers

SUNAUT National Superintendency of Tax Administration

TPSC Trade Policy Staff Committee

UNP Unidad Nacional de Protección

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

USTR Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

November 6, 2014

The Honorable George Miller

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Sander M. Levin

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

As global economic competition has intensified, concerns in the United

States that competitors’ labor practices may disadvantage U.S. workers

and producers have become acute. Recent U.S. free trade agreements

(FTA) contain a provision requiring partner countries to commit to respect

internationally accepted core labor rights, such as freedom of association

and the right to bargain collectively.

1

FTAs phase out barriers to trade

with particular countries or groups of countries and contain rules and

other commitments to improve access for services and investment. FTAs

represent a major component of U.S. trade policy, as the United States

has signed 14 FTAs with 20 countries covering, according to the

Department of Commerce, more than 35 percent of all U.S. imports—$2.3

trillion in 2013.

2

1

For example, FTAs that have entered into force since February 2009 contain a provision

stating that “[e]ach Party shall adopt and maintain in its statutes and regulations, and

practices thereunder, the following rights, as stated in the ILO [International Labour

Organization] Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and Its Follow-

up (1998).” For example, see United States-Colombia FTA (entered into Force May 2012),

art. 17.2. According to the Department of Labor (DOL), freedom of association is the right

of workers and employers to organize to defend their interests, including for the purpose

of negotiating salaries, benefits, and other conditions of work, and is a fundamental right

that underpins democratic representation and governance; collective bargaining is an

essential element of freedom of association that helps to ensure that workers and

employers have an equal voice in negotiations and provides workers the opportunity to

seek to improve their living and working conditions.

The status of the implementation of FTA labor provisions

2

As of July 2014, the United States had entered into FTAs with Australia, Bahrain,

Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala,

Honduras, Israel, Jordan, South Korea, Mexico, Morocco, Nicaragua, Oman, Panama,

Peru, and Singapore. The Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade

Agreement (CAFTA-DR) covers six of these countries (Costa Rica, Dominican Republic,

El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua).

Page 2 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

is of particular relevance, as the United States is negotiating the Trans-

Pacific Partnership—a trade agreement with 11 Pacific Rim countries, in

which the administration is seeking to negotiate high-standard labor

provisions. The effective implementation of labor provisions is also

relevant as Congress considers renewal of the President’s lapsed Trade

Promotion Authority, most recently in effect from 2002 through 2007.

3

In 2009, we reported significant challenges connected with the

enforcement of labor provisions in four FTAs.

4

We also reported that the

U.S. agencies responsible for the monitoring and implementation of labor

provisions in the FTAs in many cases engaged in only minimal oversight

and assistance with FTA partner countries to address these challenges.

We recommended that the Department of Labor (DOL), in consultation

with other agencies, initiate regular contact with all FTA partners’

ministries of labor to review implementation of FTA labor provisions and

to develop ongoing priorities and plans for technical cooperation on labor

matters. We also recommended that the Office of the U.S. Trade

Representative (USTR), in cooperation with other agencies, prepare

updated plans to implement, enforce, monitor, and report on compliance

with and progress under the FTAs’ labor provisions and that these plans

should reflect ongoing trade developments, be provided to Congress, and

be summarized in USTR’s annual trade agreements report. In 2012, both

agencies were taking actions to address the recommendations.

5

As the main U.S. point of contact for all FTAs, USTR has general

oversight responsibility for commitments in FTAs. DOL is responsible for

monitoring partner countries’ labor conditions and compliance with FTA

labor provisions, addressing complaints regarding violations of these

provisions, and providing technical assistance. The Department of State

3

Trade Promotion Authority, previously known as “fast track” negotiating authority,

established conditions and procedures under which the President could submit legislation

to approve and implement trade agreements, such as FTAs, that Congress could approve

or disapprove but could not amend or filibuster. See Bipartisan Trade Promotion Authority

Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-210, Div. B, § 2103, 116 Stat. 933, 1004–08.

4

GAO, International Trade: Four Free Trade Agreements GAO Reviewed Have Resulted

in Commercial Benefits, but Challenges on Labor and Environment Remain, GAO-09-439

(Washington, D.C.: July 10, 2009). Our 2009 report reviewed implementation of the U.S.

FTAs with, respectively, Chile, Jordan, Morocco, and Singapore.

5

Additional information about U.S. agencies’ monitoring and reporting on compliance with,

and progress under, FTA labor provisions is presented later in this report.

Page 3 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

(State) supports USTR and DOL in discharging their responsibilities and

also monitors labor conditions in each partner country. In some instances,

the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) supports partner

countries in implementing FTA labor obligations and initiatives by

administering technical assistance projects, carried out by USAID’s

implementing partners. In 2009, USTR announced that it would take

steps jointly with DOL and State to improve interagency cooperation;

proactively monitor the implementation of labor provisions; and address

identified problem areas, including foreign practices that would constitute

violations of FTA requirements. Furthermore, the President’s 2014 Trade

Policy Agenda indicates that the administration will focus on

implementation of the numerous agreements into which the United States

has entered and that the United States will work with key trading partners

around the world to address specific labor issues.

You asked us to assess the current status of the implementation of FTA

labor provisions as well as the United States’ and trade partner countries’

responses to related challenges, such as reported violence against

unionists in some partner countries. This report examines the following

(see app. I for a detailed description of our scope and methodology):

1) steps that selected partner countries have taken, and U.S. assistance

they have received, to implement FTA labor provisions and other

labor initiatives and the reported results of such steps;

2) complaints—known as submissions—about possible violations of FTA

labor provisions that DOL has accepted and any problems related to

the submission process; and

3) the extent to which USTR, DOL, and State monitor and enforce

partner countries’ implementation of FTA labor provisions and report

results to Congress.

In addition, appendix II describes reported violence against labor

unionists in selected FTA partner countries as well as steps that the

countries have taken to address such occurrences. Appendix III describes

U.S. agencies’ efforts to monitor implementation of other labor initiatives.

For our review, we selected four FTAs—the Dominican Republic-Central

America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), the United

States-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (Colombia FTA), the

United States-Oman Free Trade Agreement (Oman FTA), and the United

States-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement (Peru FTA). We also visited five

partner countries—El Salvador and Guatemala, both of which are

Page 4 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

CAFTA-DR partners; Colombia; Oman; and Peru. We selected these

FTAs and countries in part because of the extent of known labor issues in

each country; because of the timing of the FTAs’ entry into force; and to

reflect regional dispersion across Central America, South America, and

the Middle East.

6

In addition, we selected the Colombia and Peru FTAs in

part because the labor chapters in those agreements contain provisions

reflecting labor language as delineated in the May 10, 2007, Bipartisan

Trade Agreement on Trade Policy, popularly known as the May 10th

Agreement.

7

To address our objectives, we reviewed relevant documents, including

the labor chapters of the four selected FTAs; labor submissions received

by DOL; labor rights reports and trade agreement reports compiled by

U.S. agencies, international organizations, and FTA stakeholders; and

documents pertaining to U.S. monitoring and enforcement plans. In

addition, we reviewed documentation related to labor conditions in partner

countries that we obtained from partner country governments as well as

from business associations, labor unions, the International Labour

Organization (ILO), and nonprofit organizations. We interviewed

representatives of these organizations; relevant foreign government

officials; and U.S. agency officials in Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala,

Oman, and Peru during fieldwork in those countries. We also interviewed

U.S. agency representatives in Washington, D.C., and Geneva,

Switzerland.

However, the results of our review of these selected FTAs

and partner countries cannot be generalized to all FTAs and partner

countries.

8

6

According to USTR, FTA provisions provide for the FTA’s entry into force through an

exchange of formal diplomatic notes among the parties. USTR also notes that, in the

United States, the President must first determine that the trading partner has come into

compliance with obligations that will take effect when the agreement enters into force.

When an FTA enters into force, it generally means that the agreement becomes legally

binding on the parties to the agreement.

We collected data on U.S. funding for labor assistance

7

Congressional leaders and the Bush administration jointly agreed to the May 10th

Agreement, resulting in a new trade policy template that calls for, among other things, (1)

enforceable reciprocal obligation for the countries to adopt and maintain in their laws and

practice the five basic internationally recognized labor principles, as stated in the

International Labour Organization (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights

at Work and (2) labor obligations subject to the same dispute settlement procedures and

remedies as commercial obligations.

8

The views expressed by these officials and organizations cannot be generalized to all

officials or organizations knowledgeable about labor provisions in the selected FTAs.

Page 5 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

programs in FTA partner countries from 2001 to 2013 and on reported

violence against unionists in Colombia—the only selected FTA partner

country with such data—and we assessed these data’s reliability by

interviewing agency officials knowledgeable about the data sources and

by tracing the data to source documents. We determined that the data

were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing U.S. assistance

for implementation of labor provisions in FTA partner countries and

describing general trends in reported violence against unionists in

Colombia. (See app. I for further details of our scope and methodology.)

We conducted this performance audit from May 2013 to November 2014

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The current and prior administrations have expressed concerns that poor

labor standards in FTA partner countries may affect workers in the United

States and other parts of the world, incentivizing a global “race to the

bottom” that unfairly distorts global markets and prevents U.S. businesses

and workers from competing on a level playing field. According to DOL, to

address such concerns, each FTA signed in the past decade, including

those we selected, contains a “labor chapter” that differs in detail across

the FTAs but generally includes labor provisions

, establishes points of

contact for labor matters, and provides a recourse mechanism for matters

arising from the labor provisions.

9

9

All of the selected FTAs contain mechanisms to address matters arising under the

respective labor chapters. CAFTA-DR and the Colombia, Oman, and Peru FTAs each

include labor provisions that state that each party shall designate an office within its labor

ministry that shall serve as a contact point with the other party and with the public.

Furthermore, the FTAs state that each party’s contact point shall provide for the

submission, receipt, and consideration of communications on matters related to the

respective labor chapter and shall make such communications available to the other party

and, as appropriate, to the public. While either party can request consultations regarding

any matter addressed in the labor chapter, FTA dispute settlement procedures may be

invoked only under specified circumstances, which vary by FTA.

The provisions in the labor chapters of

Background

FTA Labor Provisions

and Other Initiatives to

Address Labor Concerns

Page 6 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

the four FTAs that took effect most recently generally reflect the trade

policy template created by the May 10th Agreement.

10

• In FTAs that entered into force from January 2004 through January

2009, including CAFTA-DR and the Oman FTA, the labor chapter

contains a provision that a party shall not fail to effectively enforce its

labor laws, through a sustained or recurring course of action or

inaction, in a manner affecting trade between the parties.

11

Under

CAFTA-DR and the Oman FTA, matters related to this obligation are

the only matters under the respective labor chapters for which parties

can seek recourse through dispute settlement that may result in

possible fines and sanctions.

12

These FTAs also contain a provision

whereby parties commit to “strive to ensure” that the labor rights

enumerated in the respective labor chapter are protected by their

laws; however, matters arising under this provision do not have

recourse through the dispute settlement chapter of the respective

FTA.

13

• In FTAs that entered into force after January 2009, including the

Colombia and Peru FTAs,

14

10

FTAs with Colombia, Panama, Peru, and South Korea contain language reflecting the

labor provisions of the May 10th Agreement.

the labor chapter includes language

echoing the May 10th Agreement that obligates each partner to adopt

and maintain in its statutes, regulations, and practices certain

11

United States-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (entered into force in January 2004),

art. 17.2; United States-Chile Free Trade Agreement (entered into force in January 2004),

art. 18.2; United States-Australia Free Trade Agreement (entered into in force January

2005), art. 18.2; United States-Morocco Free Trade Agreement (entered into force in

January 2006), art. 16.2; CAFTA-DR (entered into force between 2006 and 2009 for the

various countries), art. 16.2; United States-Bahrain Free Trade Agreement (Bahrain FTA)

(entered into force in January 2006), art. 15.2; and Oman FTA (entered into force in

January 2009), art. 16.2.

12

CAFTA-DR, art. 16.6.7; Oman FTA art. 16.6.5.

13

CAFTA-DR, art. 16.1.1 and 16.6.7; Oman FTA, art. 16.1.1 and 16.6.5.

14

United States-Peru FTA (entered into force in February 2009), art. 17.2, 17.3; United

States-Colombia FTA (entered into force in May 2012), art. 17.2, 17.3; United States-

Korea Free Trade Agreement (entered into force in March 2012), art. 19.2, 19.3; and

United States-Panama Free Trade Agreement (entered into force in October 2012), art.

16.2, 16.3.

Page 7 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

fundamental labor rights as stated by the ILO.

15

Although the text of

the respective FTAs’ labor chapters varies, this language generally

relates to, for example, the rights to freedom of association and

collective bargaining and the elimination of compulsory or forced

labor. The labor chapters of these FTAs also obligate the parties not

to fail to effectively enforce these labor laws in a manner affecting

trade between the parties. Pursuant to the labor chapters of these

FTAs, if consultations fail, the parties can seek to resolve matters

arising under the labor chapters by pursuing recourse through the

respective FTAs’ dispute settlement chapters, which may result in

possible fines and sanctions.

16

In addition, other labor initiatives—one known as the White Paper

17

and

the other titled Colombian Action Plan Related to Labor Rights (Labor

Action Plan)

18

—were developed in the context of CAFTA-DR and the

Colombia FTA, respectively.

19

• White Paper. Before Congress enacted implementing legislation for

CAFTA-DR,

20

15

International Labour Organization, Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at

Work and Its Follow-Up (1998),

a group of vice ministers responsible for trade and labor

in the partner countries developed the White Paper to address labor

concerns in Central America and the Dominican Republic. The White

http://www.ilo.org/declaration/thedeclaration

/textdeclaration/lang--en/index.htm, accessed August 18, 2014. The principles and rights

stated by the ILO are (1) freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right

to collective bargaining, (2) the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor, (3)

the effective abolition of child labor, and (4) the elimination of discrimination in respect of

employment and occupation.

16

United States-Peru FTA, art. 17.7; Colombia FTA, art. 17.7; United States-Korea Free

Trade Agreement, art. 19.7; and United States-Panama Free Trade Agreement, art. 16.7.

17

Working Group of the Vice Ministers Responsible for Trade and Labor in the Countries

of Central America and the Dominican Republic, The Labor Dimension in Central America

and the Dominican Republic: Building on Progress: Strengthening Compliance and

Enhancing Capacity (April 2005), accessed June 7, 2013, http://www.ilo.org/sanjose

/lang—es/index.htm.

18

Colombian Action Plan Related to Labor Rights (April 7, 2011), accessed May 29, 2013,

http://www.ustr.gov/webfm_send/2787.

19

These labor initiatives were created outside an FTA framework.

20

Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement

Implementation Act, Pub. L. No. 109-53, 119 Stat. 262 (Aug. 2, 2005).

Page 8 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Paper detailed six areas of focus and included recommendations to

enhance the implementation and enforcement of labor standards and

to strengthen the region’s labor institutions.

21

• Labor Action Plan. Colombia and the United States agreed in 2011

to the Labor Action Plan, in furtherance of Colombia’s commitment to

protect internationally recognized labor rights, prevent violence

against labor leaders, and prosecute the perpetrators of such

violence. The plan listed nine issue areas to strengthen labor rights

that Colombia was required to address before the FTA could receive

congressional approval.

According to DOL, the

U.S. government did not participate in preparing or negotiating the

White Paper’s recommendations. The ILO Verification Project, funded

by DOL, was created to monitor implementation of the White Paper

commitments and released verification reports every 6 months

between 2007 and 2010.

22

USTR and DOL are jointly responsible for

monitoring Colombia’s ongoing progress in fulfilling these

requirements.

USTR, DOL, and State have key responsibilities related to monitoring

partner countries’ implementation of FTA labor provisions. These roles

involve both discrete and shared responsibilities that require both formal

and informal coordination. USAID has provided funding for cooperative

projects to improve labor capacity.

• USTR. The U.S. Trade Representative is the President’s principal

adviser and spokesperson on trade and has lead responsibility for

negotiating trade agreements, including FTAs, as well as for

21

Under the White Paper, the labor ministers of the six CAFTA-DR countries agreed to

address the following priority areas: (1) labor law and implementation, (2) budget and

personnel needs of the labor ministries, (3) strengthening the judicial system for labor law,

(4) protections against discrimination in the workplace, (5) worst forms of child labor, and

(6) promoting a culture of compliance.

22

The nine areas that Colombia agreed to address under the Labor Action Plan were (1)

creation of a specialized Ministry of Labor; (2) criminal code reform; (3) prohibiting the

misuse of cooperatives; (4) preventing the use of temporary service agencies to

circumvent labor rights; (5) criminalizing the use of collective pacts to undermine the right

to organize and bargain collectively; (6) collecting and disseminating information on the

definition of essential services; (7) seeking the ILO’s assistance in implementing the Labor

Action Plan and working with the ILO to strengthen its presence, capacity, and role in

Colombia; (8) reforming protection programs; and (9) criminal justice reforms.

U.S. Agencies’

Responsibilities Related to

Monitoring Implementation

of FTA Labor Provisions

Page 9 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

developing and coordinating U.S. trade policy and issuing policy

guidance related to international trade functions. USTR is responsible

to the President and Congress for administering the trade agreements

program, including periodic reporting to Congress as required.

23

• DOL. DOL’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs is responsible for

monitoring implementation of FTA labor provisions for all FTAs. The

bureau’s Office of Trade and Labor Affairs is designated as the point

of contact for implementation of the labor provisions of the FTAs as

well as for the labor cooperation mechanisms. Before congressional

approval and implementation of an FTA, DOL’s responsibilities

include preparing reports for Congress, in consultation with USTR and

State, about the partner country’s labor rights protections and child

labor laws and the FTA’s potential effect on employment in the United

States. After an FTA enters into force, DOL’s responsibilities include

receiving, reviewing, and acting on any public complaint submitted

about the partner’s compliance with FTA labor obligations

(submissions).

USTR is also responsible for coordinating the administration’s

activities to create a fair, open, and predictable trading environment

by identifying, monitoring, enforcing, and resolving the full range of

international trade issues. According to USTR, this includes asserting

U.S. rights; vigorously monitoring and enforcing bilateral and other

agreements; and promoting U.S. interests, including labor interests,

under FTAs.

24

23

19 U.S.C. § 2171. Generally, the trade agreements program includes all activities

consisting of, or related to, the negotiation or administration of international agreements

that primarily concern trade and that are concluded pursuant to the authority vested in the

President by the Constitution, 19 U.S.C. § 1351, the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, and

the Trade Act of 1974 as amended.

Both before and after an FTA is implemented, DOL is

responsible for assisting the partner country as needed—for example,

planning, developing, and pursuing cooperative projects related to

labor matters—to strengthen the partner country’s capacity to promote

respect for core labor standards.

24

In addition, DOL is responsible for convening the FTA labor affairs councils among

partner government’s labor ministries, which oversee the FTA labor chapters, and for

administering the U.S. Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade

Policy. The committee consists of representatives of labor organizations and is tasked

with providing information and advice with respect to negotiation and implementation of

U.S. trade agreements. DOL also administers the National Advisory Committee for Labor

Provisions of U.S. Free Trade Agreements, which consists of 12 representatives (4 from

the business community, 4 from the labor community, and 4 from the public sector).

Page 10 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

• State. State is responsible for supporting USTR and DOL in

implementing and monitoring FTAs. State’s Bureau of Democracy,

Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) coordinates State’s in-country labor

officers, who are tasked with carrying out regular monitoring and

reporting and day-to-day interaction with foreign governments

regarding labor matters. State annually produces Country Reports on

Human Rights Practices, which includes information about countries’

labor practices. In addition, State participates with USTR and DOL in

the USTR-led interagency team that negotiates FTA labor provisions,

contributes critical input to the research and analysis of reports

produced by DOL, and provides technical assistance funding to

strengthen some countries’ labor capacity. Because USTR and DOL

do not maintain a presence in other countries, they often rely on State

for outreach, monitoring, and reporting activities related to FTA labor

provisions.

• USAID. USAID administers technical assistance programs to address

labor-related matters. USAID administers trade-capacity-building

programs globally in both FTA and non-FTA partner countries. In

addition, during the FTA negotiations, USAID provides USTR input on

draft FTA text as well as input on possible trade-capacity-building

programs to address labor-related issues.

Each of the FTA partner countries that we selected for our review has

taken steps to strengthen labor rights pursuant to its FTA with the United

States, and some of these countries have also implemented other labor

initiatives outside the FTA framework. The U.S. government has provided

some technical assistance to help FTA partner countries meet their labor

commitments. However, stakeholders reported that limitations in partner

countries’ capacity to enforce labor laws cause gaps in labor protections

to persist.

Selected Countries

Have Taken Steps,

with U.S. Assistance,

to Address FTA Labor

Commitments and

Other Labor Initiatives

but Have Limited

Enforcement

Capacity

Page 11 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

El Salvador and Guatemala, the CAFTA-DR countries we selected for our

review, have both taken steps to implement labor initiatives responding to

their FTA commitments and areas of focus identified in the White Paper.

According to the ILO, and as reported by DOL, these countries have

addressed these areas of focus by implementing changes to improve

labor protections, such as increasing the number of labor inspectors and

increasing the number of judges and courts that hear labor cases.

El Salvador. According to DOL and ILO verification reports, El Salvador

increased its Ministry of Labor’s enforcement budget by about 120

percent from 2005 to 2010, leading to an increase in the number of labor

inspectors during the same period as well as increases in both the

number of inspections conducted and the number of fines imposed on

employers.

25

Ministry of Labor officials reported that with the increase in

size and budget, which resulted from the White Paper recommendations,

the ministry is now able to accommodate workers’ requests for workplace

inspections and labor inspectors can issue fines for violations not

addressed by employers.

26

25

Department of Labor, Progress in Implementing Chapter 16 (Labor) and Capacity-

Building under the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade

Agreement (Washington D.C.: May 11, 2012). According to DOL, this report relies on

information collected by the ILO as part of its project to verify the results of actions taken

to address the White Paper recommendations.

In addition, according to officials from the

Supreme Court in El Salvador, the labor courts have created a

comprehensive statistical system to track labor issues identified in the

White Paper, and unions have successfully advocated for legislation that,

if passed, would speed labor case reviews and allow plaintiffs to

participate more actively.

26

Stakeholders reported challenges related to the issuance of fines, as discussed later in

this report

Selected Countries Have

Taken Steps to Implement

FTA Labor Commitments

and Other Labor

Initiatives, Including

Strengthening Labor

Institutions

CAFTA-DR: El Salvador and

Guatemala

Page 12 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Guatemala. Guatemala has taken some steps to address labor

conditions in accordance with commitments outlined in an Enforcement

Plan that the United States and Guatemala agreed to in 2013 as a result

of negotiations to resolve a labor case initiated through a labor

submission to DOL.

27

The actions that the plan calls for include, among

others, increasing the budget for labor law enforcement at the Ministry of

Labor and verifying employer compliance with court orders.

28

According to USTR, Colombia has taken steps to implement labor

protection commitments outlined in the Labor Action Plan, such as

reforming the criminal code to establish criminal penalties for employers

that undermine the right to organize and bargain collectively, enacting

legal provisions and regulations prohibiting the use of temporary service

agencies to circumvent labor rights, and reforming the criminal justice

system. USTR and DOL have reported that the Colombian government

took concrete steps and made meaningful progress under the Labor

Action Plan, which fulfilled the condition for advancing the FTA to

Congress and resulted in the FTA’s entering into force in May 2012. The

government’s steps included securing legislation to establish a separate

labor ministry and expanding its labor inspectorate by hiring additional

Officials

from the Ministry of Labor reported improvements in labor rights

implementation in response to the Enforcement Plan. For example, the

number of labor inspections rose from about 5,000 nationwide in 2011 to

about 36,800 nationwide in 2013. Also, according to ministry officials, the

ministry now conducts labor inspections regularly, rather than in response

to complaints, and has increased its legal education requirements for

labor inspectors, to further fulfill its Enforcement Plan commitments.

27

Mutually Agreed Enforcement Action Plan between the Government of the United States

and the Government of Guatemala (2013), accessed August 1, 2013,

http://www.dol.gov/ilab/programs/otla/guatemalasub.htm.

28

The commitments outlined in the Enforcement Plan are (1) reaching an interagency

information exchange agreement, (2) providing police assistance for Ministry of Labor

inspectors, (3) allocating resources for Ministry of Labor enforcement of labor laws, (4)

allowing for the ministry to issue fine recommendations and expedited judicial review, (5)

standardizing time frames for Ministry of Labor inspections, (6) ensuring labor law

compliance for certain enterprises, (7) ensuring labor law compliance for enterprises

receiving export benefits, (8) ensuring labor law compliance upon enterprise closure, (9)

employer substitution, (10) developing a system for tracking compliance with court orders,

(11) verifying employer compliance with court orders, (12) monitoring judicial enforcement

of court orders, (13) applying certain labor code articles, (14) ensuring transparency and

tripartite coordination on Enforcement Plan implementation, (15) publishing labor law

enforcement statistics and data.

Colombia

Page 13 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

inspectors. Additionally, USTR and the Colombian Ministry of Labor

reported that the government enacted a series of laws and ministerial

decrees that expanded labor protections as a result of the Labor Action

Plan. According to USTR and the Colombian Ministry of Labor, these

laws and decrees include, for example, legislation to establish criminal

penalties, including imprisonment, for employers that undermined the

right to organize and bargain collectively as well as new provisions and

regulations to prohibit and sanction with significant fines the misuse of

cooperatives

29

and other employment relationships that undermine

workers’ rights.

30

Oman has taken steps to implement labor protections that have allowed

for unionization and collective bargaining. Officials from Oman’s Ministry

of Manpower—the ministry responsible for labor affairs—reported that

Oman’s interest in entering into a free trade agreement with the United

States helped lead to the introduction of labor reforms, including the

establishment of unions. According to USTR, in order to meet its

commitments made in connection with the FTA, Oman has enacted a

number of labor law reforms including, among others, a royal decree in

2006 that established the right to organize labor unions, allowed for

collective bargaining, prohibited the dismissal of workers for union

activity, guaranteed the right to strike, and guaranteed unions the right to

practice their activities freely and without interference from outside

parties. According to union and Ministry of Manpower officials we met

with in Oman, the General Federation of Trade Unions held its first

election in 2010 and served as the starting point for the union movement

in Oman. The federation serves as an umbrella organization representing

workers from various sectors and, according to union officials, represents

about 200 company-level unions and one sector-level union, established

in 2013 in the oil and gas sector.

29

According to DOL, associated work cooperatives are self-governed, autonomous

enterprises, under which associated workers are considered cooperative owners, rather

than workers, and are excluded from many Labor Code protections.

30

According to DOL’s 2011 Labor Rights Report on Colombia, until late 2010, penalties for

the misuse of cooperatives to avoid direct employment relationships were not enforced

against third-party employers. According to DOL, as a result, cooperatives became a

vehicle widely used by employers to end direct employment relationships with their

workforces while retaining the same workers through cooperatives and continuing to act

as their de facto employers.

Oman

Page 14 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

According to USTR, Peru committed to steps to implement labor

protection commitments in the context of FTA negotiations with the United

States. During our fieldwork, officials at Peru’s Ministry of Labor told us

that Peru recently established a new labor inspection regime and that the

ministry has focused on improving inspections in the workplace. For

example, in 2013, according to Ministry of Labor officials, the ministry

took action to centralize authority for labor inspections and help ensure

that inspectors are applying the same criteria across the country. Ministry

of Labor officials also reported that the ministry took steps to improve

labor inspections by modernizing its information systems to allow for

digital record keeping, with technical assistance provided by USAID.

According to USAID, as a result of these programs, the time required to

adjudicate labor cases has decreased from 2 years to 6 months.

Additionally, according to a 2007 U.S. House of Representatives,

Committee on Ways and Means report, in order to bring Peruvian labor

laws into alignment with the obligations under the FTA, the government of

Peru took steps to change Peru’s legal framework governing temporary

employment contracts, subcontracting and outsourcing contracts, the

right of workers to strike, recourses against unit-union discrimination, and

workers’ right to organize. Ministry of Labor officials reported that the

ministry has progressively increased the number of labor inspectors, in

connection with the commitments Peru made during the FTA negotiation,

to double its labor inspectorate. As of September 2013, the ministry

reported having about 400 labor inspectors on staff nationally.

Peru

Page 15 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

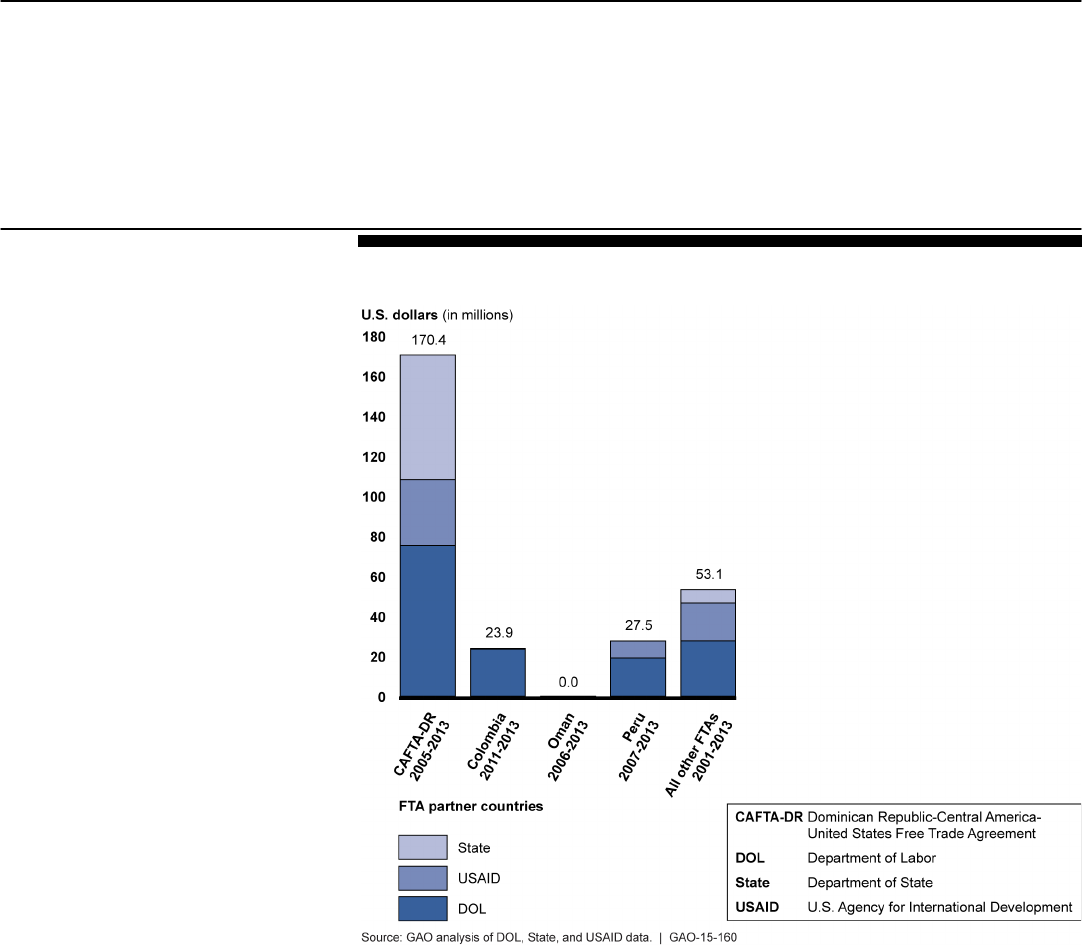

From fiscal year 2001 through fiscal year 2013, the U.S. government

provided a combined total of about $275 million in labor-related

assistance for all FTA partner countries.

31

All CAFTA-DR countries,

Colombia, and Peru received a combined total of about $222 million in

labor-related technical assistance and capacity-building activities since

the passage of implementing legislation for these FTAs. In contrast, the

U.S. government provided about $53 million in labor-related assistance

for all other FTA partner countries during the periods since those FTAs

were implemented.

32

Figure 1 shows the labor-related technical assistance that U.S. agencies

provided under CAFTA-DR and the Colombia, Oman, and Peru FTAs

during the periods beginning, respectively, with the year that Congress

passed the FTA’s implementing legislation and ending in 2013. Figure 1

also shows labor-related technical assistance that U.S. agencies provided

from 2001 through 2013 under all other FTAs that entered into force in or

after 2001.

31

This amount includes both FTA and non-FTA labor-related assistance provided to FTA

partner countries. This amount does not include labor-related technical assistance to

Oman that DOL provided for a joint project in Oman and Bahrain. DOL’s records show

that it obligated $758,000 for the project in 2006 but do not show how the funds were

divided between the two countries, because, according to DOL, standard financial reports

for federal grants to more than one country do not allow the grantor to report amounts

received by each country. In addition, this amount excludes any assistance provided

under the United States-Israel Free Trade Agreement (Israel FTA), which does not contain

a specific article on labor provisions, and the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA), which addresses labor-related issues under a related agreement, the North

American Agreement on Labor Cooperation.

32

This amount excludes the Israel FTA and NAFTA.

U.S. Agencies Have

Provided Technical

Assistance to Help FTA

Partner Countries Meet

Labor Commitments, with

Largest Amounts for

CAFTA-DR

Page 16 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Figure 1: Labor-Related Technical Assistance Administered by U.S. Agencies under

Selected Free Trade Agreements (FTA) and All Other FTAs

Notes: Time periods for the data shown for CAFTA-DR and the Colombia, Oman, and Peru FTAs

each begin with the year that the respective FTA’s implementing legislation was passed by Congress,

before the FTA entered into force. Data for “All other FTAs” exclude the only FTAs that entered into

force before 2001—the U.S.-Israel Free Trade Agreement (1985) and the North American Free Trade

Agreement (1994).

Totals for projects that DOL administered under CAFTA-DR include projects that Congress funded

through appropriations to DOL for technical assistance to reduce child labor as well as projects that

State’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs funded through transfers to DOL from State’s

Economic Support Fund and Development Assistance account.

Data shown exclude funding that DOL provided for a regional labor-related technical assistance

project in Oman and Bahrain in 2006. According to DOL officials, data showing country-specific

funding for regional projects are not available.

Data shown for Colombia include $500,000 that State provided for promotion of labor rights.

CAFTA-DR’s six partner countries have received the largest amounts of

U.S. assistance for labor-related projects undertaken pursuant to the FTA

or independent of the FTA. From 2005, when the CAFTA-DR

CAFTA-DR

Page 17 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

implementing legislation was passed by Congress, through 2013, the

U.S. government provided about $170 million for such projects. According

to DOL, this amount included funding appropriated by Congress to fund

labor-capacity-building activities as well as funds appropriated to DOL for

child labor technical assistance projects to assist these partner countries

in addressing labor-related priorities outlined in the White Paper.

33

U.S. technical assistance for labor-related projects in Colombia totaled

about $24 million from 2011, when the Colombia FTA implementing

legislation was enacted, through 2013. U.S. agencies provided $9 million

of that amount for projects to combat child labor and about $13 million to

address workers’ rights. DOL has also provided in-kind resources,

sending a staff person with labor expertise to support the Colombian

government in taking initial steps to implement the Labor Action Plan. The

United States is currently funding multiple labor-related projects in

Colombia, including State’s award of about $500,000 to the ILO for the

promotion of core labor rights and DOL’s award of about $7.8 million for

the ILO office in Colombia.

According to DOL officials, DOL, State, and USAID established an

interagency group to develop FTA labor-related projects in consultation

with USTR and CAFTA-DR partner governments and to allocate funding

among these projects, with funds transferred from State. DOL reported

that from 2005 to 2013, these three U.S. agencies administered more

than 20 technical assistance projects in support of the White Paper’s

priority issue areas.

Oman has not received U.S. technical assistance specifically for labor-

related projects since the FTA was enacted. According to State, the

United States is not involved in any labor-capacity-building or labor-

related assistance programs in Oman because of the Omani

government’s reluctance to accept foreign assistance. However, officials

at Oman’s Ministry of Manpower told us that the United States has

provided information and advice on supporting unions and the role of

unions in the economy and has expressed support of ongoing labor

reforms, including the establishment of unions.

33

Beginning in 2005, Congress appropriated funds for labor-capacity-building activities

relating to the free trade agreements with the countries of Central America and the

Dominican Republic. For example, see Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005, Pub. L.

No.108-447, §570, 118 Stat. 2809, 3026 (2004).

Colombia

Oman

Page 18 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

U.S technical assistance for labor-related projects in Peru totaled about

$27.5 million from 2007, when the Peru FTA implementing legislation was

enacted, through 2013. Of that amount, $13 million was dedicated to

combat child labor, with the remainder dedicated to labor-capacity-

building and education projects. USAID officials stated that, for example,

the agency expended $3.3 million over a 3-year period to target labor

issues. Of this amount, $2.7 million was granted to the Solidarity Center,

a labor nongovernmental organization (NGO) affiliated with the American

Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO),

to strengthen union negotiation capacity, and $600,000 was granted to an

implementing partner—Nathan Associates—for improving information

systems, providing training for labor inspectors, and training judges on the

implementation of labor laws.

El Salvador. Stakeholders we met with during our fieldwork in El

Salvador identified concerns related to the enforcement of labor rights.

Further, State and DOL reports show that workers are often unable to

benefit from the legal rights afforded in the labor laws. For example,

according to NGO officials, although labor courts have improved their

ability to process cases, court decisions are often not enforced. U.S.

officials stated that the Ministry of Labor’s increases in its budget and

number of labor inspectors have not improved the labor inspectorate’s

effectiveness. According to Ministry of Labor officials, although the

ministry’s labor inspectors can fine employers for labor law violations, the

ministry does not collect the fines and workers must petition the labor

courts to enforce the penalties. Moreover, according to an ILO official,

although the government of El Salvador has greatly reduced the amount

of time that the courts take to accept a case, resolution of most labor

disputes still takes 2 to 4 years. Officials from the Supreme Court in El

Salvador told us that about 51 percent of labor court sentences are not

enforced, primarily because the plaintiffs do not have the funds required

to continue the claims. Union and NGO officials we met with in El

Salvador emphasized their concerns over enforcement, stating that

because of the length of time the courts take to adjudicate labor cases,

Peru

Stakeholders Reported

Limited Enforcement

Capacity and Gaps in

Labor Rights in Selected

Partner Countries

CAFTA-DR: El Salvador

and Guatemala

Page 19 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

workers often take buyouts from the company and drop the cases. State’s

2013 Human Rights Report echoes these concerns. For example, the

report states that in 2013, the government of El Salvador did not always

effectively enforce the laws on freedom of association and the right to

collective bargaining, and that legal remedies and penalties are

ineffective.

Guatemala. According to stakeholders we met with during our fieldwork

in Guatemala, as well as State reports, concerns related to the

enforcement and application of labor rights persist. According to USTR,

Guatemala has taken steps to address labor reforms outlined in the

Enforcement Plan, but additional steps are needed, including passing

legislation providing for an expedited process to sanction employers that

violate labor laws and implementing a mechanism to ensure payments to

workers in cases where enterprises have closed.

34

Additionally, according

to USTR, Guatemala will need to demonstrate that the legal reforms it

has undertaken and still needs to undertake are being implemented

effectively and are leading to positive changes.

35

34

According to USTR, as of September 2014, this bill had not been passed by the

Guatemalan congress.

Union representatives

reported concerns related to freedom of association—specifically, that

union leaders have been offered monetary compensation to resign from

their jobs and to influence other workers against joining the union. Union

officials we met with also noted that workers have been terminated for

their union affiliation or for not disbanding unions. State’s 2013 Human

Rights Report echoed these concerns, stating that the government of

Guatemala did not effectively enforce legislation on freedom of

association, collective bargaining, or antiunion discrimination. Further,

according to this report, as a result of inadequate allocation of budget

resources and inefficient legal and administrative processes, the relevant

government institutions did not effectively investigate, prosecute, and

punish employers who violated freedom of association and collective

35

For more information about the status of implementation of the Guatemala Enforcement

Plan, see app. III.

Page 20 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

bargaining laws, and the institutions did not reinstate workers illegally

dismissed for engaging in union activities.

36

Stakeholders we met with in Colombia identified concerns related to the

enforcement of labor rights and not benefiting from rights afforded in the

labor laws. According to USTR, the government of Colombia has made

meaningful progress under the Labor Action Plan, but work remains to

build on this progress and address remaining and new challenges.

• According to USTR, the collection of fines for labor violations remains

problematic. USTR and DOL have reported that although Colombia’s

national training and apprenticeship system, Servicio Nacional de

Aprendizaje (SENA), is responsible for collecting fines for labor

violations, until recently SENA has been barred from collecting fines

from companies that filed a judicial appeal.

37

• USTR has reported that new forms of abusive contracting remain

problematic to the protection of labor rights in Colombia. For example,

according to USTR, although the number of illegal cooperatives has

dropped, many employers have shifted to various forms of

subcontracting, including entities known as simplified stock

companies, to avoid direct employment relationships.

According to a joint

USTR-DOL statement, as of April 2014, SENA was authorized to hold

monetary payment as collateral payment from businesses, pending

the outcome of the judicial appeal of their fines, but had not yet begun

to exercise this authority. Additionally, although the Ministry of Labor

increased the number of inspectors, labor unions and NGOs reported

that this action has not resulted in more effective inspections or

improved working conditions.

38

36

According to U.S and Guatemalan officials, as well as union representatives and the

ILO, violence against unionists has occurred in Guatemala. The government of Guatemala

reported that it had taken steps to address the violence. However, stakeholders were

unsure of the extent of the problem because of a lack of statistics collected by the

government. For more information about violence against unionists in Guatemala, see

app. II.

ILO, NGO,

37

According to DOL, Colombia’s Minister of Labor heads SENA's board of directors.

38

According to DOL, a simplified stock company is a corporate model that holds

shareholders liable only up to the amount of their investment. DOL further stated that

these companies are easy to create and dissolve and are a legitimate business model in

Colombia. In cases where a simplified stock company is used for contracting—either legal

or illegal—an employer hires the company to carry out a task and the company provides

the labor through its own employees.

Colombia

Page 21 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

and labor union officials we met with described this form of

subcontracting as a legal loophole that is used to undermine workers’

rights. According to union officials, a law passed by the Colombian

government in 2013 prohibiting the misuse of cooperatives was also

intended to increase formalized employment and encourage

companies to hire workers directly instead of as temporary labor.

State’s 2013 Human Rights Report noted that the Colombian government

generally enforced applicable labor laws and took steps to increase the

enforcement of freedom-of-association laws. However, the report

identified weaknesses in labor protections in Colombia, echoing concerns

expressed to us by labor union and NGO representatives, related to labor

inspections, collecting fines for labor violations, and employers’ use of

outsourcing contracts.

39

Ministry of Manpower and union officials we met with in Oman reported

that collective bargaining and freedom of association are allowed by law

and largely respected. However, State has raised concerns about the

enforcement of labor law among Oman’s foreign worker population.

State’s 2013 Human Rights Report notes that Oman’s Ministry of

Manpower effectively enforces the labor law as it applies to Omani

citizens but has not effectively enforced regulations related to working

conditions and hours for foreign workers.

Despite steps that the government of Peru has taken to address labor

conditions, union and NGO officials we met with reported that

enforcement of labor laws remains weak and labor conditions have not

improved in certain respects. According to State, Peru’s labor laws place

a 5-year limit on the continuous renewal of short-term labor contracts not

leading to permanent employment in most sectors of the economy.

However, State’s 2013 Human Rights Report notes that a sector-specific

law covering nontraditional export sectors such as apparel exempts

employers from this 5-year limit and allows them to hire workers through

indefinite series of short-term contracts. Union officials we met during our

fieldwork also reported poor labor conditions in Peru’s nontraditional

39

In addition, although murders of unionists have generally been decreasing over the past

10 years, and despite actions by the Colombian government to reduce homicides of union

members and labor activists, stakeholders we interviewed reported that violence against

unionists continues. For a more detailed description of reported violence against union

members and activists in Colombia, see app. II.

Oman

Peru

Page 22 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

export sectors, which these officials described as not affording the same

labor rights as other sectors in the economy.

40

State’s 2013 Human Rights Report also identifies continuing labor

concerns in Peru’s nontraditional export sectors, such as the effect of the

use of temporary service contracts and subcontracting on workers’

freedom of association. State’s report also notes that in 2013, penalties

for violations of freedom of association and collective bargaining were

rarely enforced, the judicial process was prolonged, and employers were

seldom penalized for dismissing workers involved in trade union activities.

In addition, union officials whom we met with stated that Peru’s

agricultural law allows for workers to be paid less than the legal minimum

wage and to be continuously hired on temporary contracts for 2- to 3-

month periods. These officials stated that this limits workers’ ability to

collectively bargain and exercise freedom of association, because of fear

that if they join a union, their contracts will not be renewed.

More generally, according

to NGO officials, Peru’s large informal sector makes it difficult for the

government to enforce labor rights, because informal companies, which

are not registered with the government and therefore are not subject to

labor inspections, typically do not follow labor laws.

40

According to State, Peru’s nontraditional export sectors include fishing, wood and paper,

nonmetallic minerals, jewelry, textiles and apparel, and the agriculture industry.

Page 23 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

DOL has accepted five of six labor submissions—that is, formal

complaints alleging that FTA labor provisions had been violated—that it

has received since 2008

41

and has closed one submission as resolved.

However, DOL did not meet its original deadlines for reviewing and

reporting on any of the submissions, exceeding the established 6-month

submission review time frame by an average of about nine months and

possibly delaying resolution of the submissions. Stakeholders whom we

interviewed in the selected five partner countries generally expressed a

lack of awareness or understanding of DOL’s submission process, which

may have limited the number of submissions filed. Moreover,

stakeholders we interviewed expressed concerns about delays in

resolving labor concerns detailed in the submissions for Guatemala and

Honduras.

According to DOL, FTA labor provisions establish official processes for

receiving submissions from interested organizations that believe a trading

partner is not fulfilling its labor commitments. In the United States, DOL

generally receives and reviews submissions made under the labor

chapters of each trade agreement. DOL issued procedural guidelines

pertaining to this function via publication of a Federal Register notice in

2006.

42

41

According to DOL officials, DOL also received a sixth submission, filed under the Costa

Rica FTA in July 2010, which the filing party withdrew before DOL decided whether to

accept it. DOL has also accepted other labor submissions under the North American

Agreement on Labor Cooperation (one of three accords supplementary to NAFTA), which

we did not examine.

The guidelines contain deadlines and substantive criteria for

acceptance and investigation of submissions. For example, DOL shall

determine whether to accept a submission within 60 days and is to

consider, among other things, whether it contains statements that, if

substantiated, would constitute a failure by the other party to comply with

its commitments under an FTA. If DOL determines that the circumstances

require, the 60-day timeframe can be extended. According to DOL, its

decision to review a public submission does not indicate any

determination as to the validity or accuracy of the allegations contained in

the submission; the submission’s merit is addressed in the public report

that follows DOL’s review and analysis. DOL officials noted that although

DOL has responsibility for investigating submissions, USTR, DOL, and

State work together to engage diplomatically to address concerns.

42

71 Fed. Reg. 76691 (Dec. 21, 2006).

One of Five Labor

Submissions Has

Been Resolved, but

Reporting Deadlines

and Limited Public

Awareness of the

Process Present

Problems

DOL Announced Its

Process for Receiving

and Evaluating

Submissions in 2006

Page 24 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Figure 2 illustrates DOL’s submission process, including the established

time frames for accepting and reviewing submissions.

Figure 2: U.S. DOL Labor Submission Process

Legend: FTA = free trade agreement, USTR = Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

a

DOL may extend the timeframe if it determines that circumstances require such an extension.

b

The free trade commission established for each FTA is the primary forum for bilateral dialogue about

the FTA’s implementation.

Page 25 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

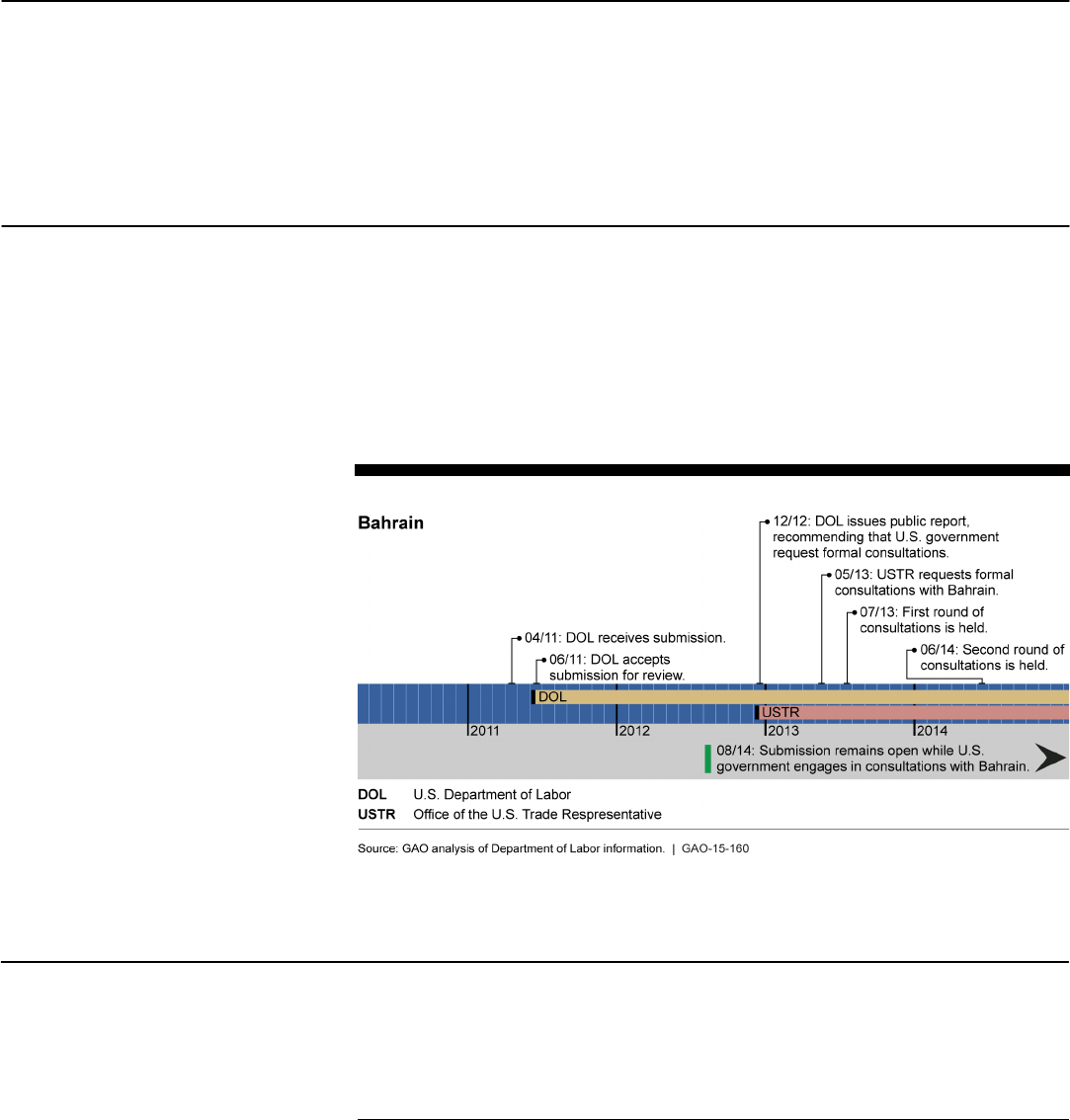

Since 2008, DOL has accepted labor submissions filed under the

Bahrain, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru FTAs and

has closed the Peru FTA submission.

43

43

DOL has also accepted other labor submissions under the North American Agreement

on Labor Cooperation (one of three accords supplementary to NAFTA), which we did not

examine.

The submissions for Bahrain, the

Dominican Republic, and Guatemala—accepted in 2011, 2012, and 2008,

respectively—remain open while the U.S. government engages with the

governments to address the concerns that the submissions raised. The

submission for Honduras, accepted in 2012, remains open while DOL

reviews its allegations. Figure 3 presents information about the five

submissions (see app. III for further details).

DOL Has Closed One of

Five Labor Submissions

Accepted since 2008

Page 26 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Figure 3: Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Labor Submissions Accepted by DOL as of

July 2014

Notes: DOL has also accepted other labor submissions under the North American Agreement on

Labor Cooperation, which we did not examine.

Alleged violations shown for the Bahrain, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Honduras

submissions are examples of those detailed in the submissions.

Page 27 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

Although DOL accepted most of the submissions it received within the 60-

day time frame established by its guidelines, it did not complete its

reviews of the submission within the established 180-day time frame.

44

For each of the submissions, DOL determined at the end of the original

180-day review time frame to extend the review period and reported its

findings and recommendations an average of 262 days after the original

time frame had ended. According to USTR and DOL, before DOL

publishes its review of a submission, both agencies engage informally

with the relevant partner country to explore ways to address the concerns

raised in the submission. However, USTR and DOL do not request formal

consultations with a partner country to address DOL’s recommendations

until DOL has issued its report. As a result, extensions of DOL’s review

time frame may delay resolution of the submission.

A

DOL official we met with indicated that DOL cannot complete within the

180-day time frame the types of comprehensive investigations and

reports it has been providing.

• Bahrain. DOL received the Bahrain submission on April 21, 2011,

and accepted it on June 10, 2011, or 50 days later. In December

2011, DOL extended the submission review period to consider and

review additional information received from the government of Bahrain

and Bahraini workers, amendments made to the Bahraini Trade Union

Law, and labor-related developments in international forums. DOL

issued its report on December 20, 2012, 559 days after accepting the

submission.

• Dominican Republic. DOL received the Dominican Republic

submission on December 22, 2011, and accepted it on February 22,

2012, or 62 days later. In August 2012, DOL extended the review time

frame to consider public comments about the submission as well as

information gathered by a Bureau of International Labor Affairs

delegation during a visit to the Dominican Republic. DOL issued its

report on September 27, 2013, 583 days after accepting the

submission.

• Guatemala. DOL received the Guatemala submission on April 23,

2008, and accepted it on June 12, 2008, or 50 days later. DOL issued

44

DOL may extend the timeframe if it determines that the circumstances require such an

extension. 71 Fed. Reg. 76691.

DOL Did Not Meet 6-

Month Time Frame for

Any Submission, Showing

the Time Frame to Be

Unrealistic

Page 28 GAO-15-160 Labor Provisions in Free Trade Agreements

its report on January 16, 2009, 218 days after accepting the

Guatemala submission.

• Honduras. DOL received the submission on March 26, 2012, and

accepted it on May 14, 2012, or 49 days later. On November 2, 2012,

5 days before DOL’s 180-day reporting deadline, DOL extended its

review because of the scope of the submission, the scope of the

alleged labor law violations, and the large amounts of information

received from the Honduran government and stakeholders. As of

September 2014, DOL officials were continuing to review

documentation of the allegations and prepare their report. DOL

officials were unable to estimate when they would issue a public

report.

• Peru. DOL received the submission for Peru on December 29, 2010,

and accepted it on July 19, 2011, or 202 days later. On January 20,

2012, 185 days after accepting the submission, DOL concluded that

circumstances required an extension of time for a thorough and

detailed review of the Peru submission. DOL issued its report for the

Peru submission on August 30, 2012, 408 days after accepting it.

Although DOL has periodically reviewed and updated the submission

process since establishing it in 1994, DOL officials told us that they have

not reviewed or adjusted the submission review time frame to reflect the

time it takes DOL to issue its reports after accepting the submissions.

DOL’s extensions of each submission review period since 2008 have

shown this time frame to be unrealistic. Federal standards for internal

control call on agency management to monitor and assess the

effectiveness and efficiency of their operations over time and to promptly