Assessment

of the Effects and Impacts of

HURRICANE DORIAN

in THE BAHAMAS

Assessment

of the Effects and Impacts of

HURRICANE DORIAN in

THE BAHAMAS

Foreword

The threat of climate change presents unique challenges to the

Caribbean region, with smaller island nations like The Bahamas

particularly vulnerable to the chaos of natural disasters and the impact

they have on developing economies.

The Inter-American Development Bank is proud of its long-standing,

rich history with the islands of The Bahamas, solidified in meaningful

partnerships with the nation’s Government, the private sector and its

citizenry. During this time, the Bank has witnessed first-hand the

increasing intensity of natural disasters and the disruption to lives and

the livelihoods within our member country.

In October 2016, Hurricane Matthew passed through the chain of

islands, varying between category 3 and category 4 intensity levels that

left widespread damage in its path. Nearly a year later, Hurricane Irma

tore through the country as a category 4 storm in September 2017,

rendering many smaller islands uninhabitable in the short-term and

changing daily life in those areas in the long-term. In September 2019,

the world watched as the category 5 Hurricane Dorian rained havoc

down on The Bahamas islands of Grand Bahama and Abaco and their

communities, erasing any evidence of life in some neighborhoods and

leaving behind a trail of heartbreak, sorrow and death.

The catastrophic damage to livelihoods and billions of dollars of

infrastructure on this archipelago present significant challenges to the

preparedness of its tourism-dependent economy and its rescue and

recovery capacity.

As the leading multilateral Bank, The IDB committed itself to a

restoration effort that would be far-reaching and strengthen the island

chain against future natural disasters. Through a partnership with the

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, the Bank

deployed a research team of experts – both local and international – to

the affected sites to collect pertinent data that could be integrated in a

more sustainable framework for disaster risk management, policy

preparedness and reconstruction methods after a natural disaster.

Within this report is a comprehensive overview of the toll Hurricane

Dorian had on the islands’ economies and an accounting of the losses,

broken down throughout the sectors. It analyzes key vulnerabilities and

threats and compiles findings from assessments with recommendations

to build resilience in a way that honors the nation’s past while

advancing the present and preserving its future. This report, together

with the reports on Hurricane Matthew and Hurricane Irma, provides

The Bahamas with data that supports meaningful policy reforms to

promote strategic decision making regarding natural disasters.

As we forge ahead, there is a new reality developing and it is that we

are now living in uncertain times where climate change and its impacts

require us to have tactical plans in place that protect and foster stability

in the nation’s economic and cultural systems. The Inter-American

Development Bank is honored to continue to partner with the

Government of The Bahamas and present this Damage and Loss

Assessment report to help strengthen national initiatives for a more

resilient Bahamas.

Daniela Carrera-Marquis

Country Representative

Inter-American Development Bank

Country Office Bahamas

The Caribbean is among the regions of the world most vulnerable to the

impact of extreme weather events, with countries of the subregion

experiencing among the highest rates of damage relative to their gross

domestic product (GDP). Indeed, considering the ratio of affected

population to total population and the damage-to-GDP ratio, Caribbean

small island developing States (SIDS) have been more significantly

affected than those in other regions of the world. The gravity of this

situation is brought into even sharper focus by the fact that SIDS are

already bearing the brunt of the impacts of climate change and will face

even higher economic and social costs if the projected scenarios of sea-

level rise become a reality.

Within the Caribbean subregion, the negative impacts of extreme

weather events over the years have been most vividly illustrated in the

Bahamas. Since 2015, the Bahamas has been devastated by four large

hurricanes, three of which have been classified as category 5 events.

Hurricane Joaquin affected the Family Islands in 2015 and Hurricane

Matthew hit Nassau and Grand Bahama in 2016. In 2017, the country

was not spared the ravages of Hurricane Irma, one of the Atlantic

Basin’s most powerful storms, which affected primarily Ragged Island,

Grand Bahama and Bimini. Most recently, following a brief reprieve in

2018, Hurricane Dorian unleashed devastating force on the beautiful

Abacos and Grand Bahama islands in 2019. Dorian left in its wake a

swathe of destruction surpassing the loss and damages of the three

previous hurricanes combined, costing an estimated US$ 3.4 billion.

These events have taken an overwhelming toll on the tourism sector,

the country’s main engine of growth. As a result, these vulnerabilities

significantly diminish the capacity of the Bahamas to finance its

recovery and resilience-building.

ECLAC has conducted Damage and Loss Assessments (DaLA)

following each of the events mentioned above, measuring their

economic, social and environmental impacts on the Bahamas. The

assessments were jointly undertaken with the support of the Inter-

American Development Bank (IDB) and the Pan American Health

Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). Great care is

taken to ensure the completeness and accuracy of these assessments,

given the important role the reports serve in estimating the extent of

loss and damage suffered; to describe the critical areas of need for

governments in the aftermath of these events; and to guide the

country’s resilient reconstruction efforts. The DaLA reports have also

found wider application in strengthening national policies by

integrating key recommendations in the disaster risk management

(DRM) policy framework of the Bahamas.

I am very pleased to submit for the judicious use of the Government of

the Bahamas the report on the Effects and Impacts of Hurricane Dorian

on the Bahamas. It is my hope that this assessment will serve as a

valuable guide for decision makers in the design of resilient

reconstruction and redevelopment on the affected islands. Such

development, however, requires low-cost long-term development

finance which is not currently available to the Bahamas because of its

income status. The hard evidence in this report should prove to the

international community that the Bahamas needs external financial

support to strengthen its resilience to disasters and to build back better.

I therefore propose it be used as a robust point of reference and I also

encourage DRM experts, international development partners and civil

society to embrace its specific recommendations for rebuilding with

resilience.

Alicia Bárcena

Executive Secretary

Economic Commission for

Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN

Omar Bello Mission Coordinator

Luciana Fontes de Meira Technical Coordinator and Environment

Candice Gonzales Affected Population

Leda Peralta Disaster Risk Reduction

Nyasha Skerette Education

Blaine Marcano Power and Telecommunications

Machel Patin Commerce

PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION

Gabriel Vivas Health

Sector Specialists

Carlos Espiga Roads, Port, Airports and Public Buildings

Eduardo Allen Support in Infrastructure (Tourism, Commerce)

Esteban Ruiz Support in infrastructure (Education, Health)

Francisco Ibarra Tourism, Agriculture and Fisheries

Franklin Espiga Housing, Water and Sanitation

Mauricio Gonzalez Description of the Event and GIS Support

Salvador Marconi National Accounts

INTERAMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK

Daniela Carrera-Marquis Country Representative

Michael Nelson Chief of Operations

Yuri Chakallal Natural Resources & Risk Management

Maria Alejandra Perroni Water and Sanitation Specialist

Christopher Persaud Transport Specialist

Chitralekha Deopersad Natural Resources & Risk Management

Malaika Masson Energy Specialist

Zachary Zane Editor

Sandra Caula Graphic designer

contents

List of Tables 6

List of Figures 8

Acronyms 11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 13

Introduction 13

Summary of Damage, Losses and Additional Costs 15

Methodological Approach 17

DESCRIPTION OF EVENT 25

AFFECTED POPULATION 41

Introduction 41

Primary Affected Population 43

Secondary Affected Population 52

PART ONE: ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTS

SOCIAL SECTORS 56

Housing and Public Buildings Sector 57

Introduction 57

Baseline Information 58

Damage 59

Losses 60

Additional Costs 61

Public Buildings 63

Baseline Information 63

Damage 63

Additional Costs 64

Health Sector 65

Introduction 65

Baseline Information 65

Damage 66

Losses 68

Additional Costs 69

Education 71

Introduction 71

Baseline Information 72

Damage 73

Losses 76

Additional Costs 79

INFRASTRUCTURE SECTORS 80

Roads, Airports, Ports and other Infrastructure 81

Introduction 81

Baseline Information 82

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

4

Damage 83

Losses 88

Additional Costs 88

Telecommunications 89

Introduction 89

Baseline Information 89

Damage 90

Losses 90

Additional Costs 91

Power sector 93

Introduction 93

Baseline Information 93

Damage 94

Losses 95

Additional Costs 96

Water and Sanitation 99

Introduction 99

Baseline Information 99

Losses 104

Additional Costs 104

PRODUCTIVE SECTORS 106

Tourism Sector 107

Introduction 107

Baseline Information 107

Damage 108

Losses 109

Additional Costs 115

Fisheries and Agriculture 117

Introduction 117

Baseline Information 117

Damage 117

Losses 118

Commerce sector 119

Introduction 119

Baseline Information 119

Damage 120

Losses 122

Additional Costs 124

ENVIRONMENTAL SECTOR 127

Introduction 127

Baseline Information 129

Damage 131

Losses 139

Additional Costs 141

assessment of the effects

5

MACROECONOMIC IMPACT 145

Introduction 145

Economic Activity and Remunerations 145

Impact on Economic Activity 146

Fiscal Impact 146

PART II: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A RESILIENT RECOVERY

INTRODUCTION 151

PILLAR 1: RISK IDENTIFICATION 155

A. Standardization and Protocols 155

B. Data and Information Management 156

PILLAR 2: RISK REDUCTION 163

A. Disaster Risk Management in Public Investments 163

B. Spatial Planning 163

C. Environmental Regulations 164

D. Flooding Mitigation Measures 165

E. Enforcement of the Building Code and Maintenance 167

Sectoral recommendations 171

PILLAR 3: PREPAREDNESS 175

Affected Population 175

Social Sectors 176

Infrastructure Sectors 177

Environment 178

PILLAR 4: FINANCIAL PROTECTION 179

Social Sectors 180

Infrastructure Sectors 180

Productive Sectors 181

Environment 182

PILLAR 5: RESILIENT RECOVERY 183

Affected Population 184

Social Sectors 184

Infrastructure Sector 186

Productive Sectors 197

ANNEX 201

Sectoral Risk Reduction Recommendations 203

Social Sectors 203

Infrastructure Sectors 204

Productive Sectors 208

REFERENCE MATERIALS 211

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

6

list of tables

Table 1. Summary of Effects of Hurricane Dorian 16

Table 2. Tropical Storms and Hurricanes in The Bahamas (1990 – 2019) 38

Table 3. Demographics of the Affected Islands 43

Table 4. New Providence: Population in Shelters 47

Table 5. Grand Bahama: Population in Shelters 48

Table 6. Abaco: Population in Shelters 48

Table 7. Affected Population with Damage to Homes 49

Table 8. Red Cross Relief Distributions to Affected Islands 50

Table 9. U.S Relief Distributions to Affected Islands 51

Table 10. UKaid Relief Distributions to Affected Islands 52

Table 11. Abaco: Number of Dwellings 58

Table 12. Grand Bahama: Number of Dwellings 58

Table 13. Housing Sector: Damage 59

Table 14. Abaco: Damaged Houses 60

Table 15. Grand Bahama: Damaged Houses 60

Table 16. Abaco: Losses 61

Table 17. Grand Bahama: Losses 61

Table 18. Abaco: Additional Costs 62

Table 19. Grand Bahama: Additional Costs 62

Table 20. Public Buildings: Damage 63

Table 21. Public Buildings: Level of Damage 63

Table 22. Public Buildings: Additional Costs 64

Table 23. Health Care Facilities in the Affected Islands 66

Table 24. Grand Bahama: Health Care Infrastructure Damage 67

Table 25. Abaco: Health Care Infrastructure Damage 67

Table 26. Health Sector: Damage 68

Table 27. Health sector: Losses 68

Table 28. Health Sector: Additional Costs 69

Table 29. Education Sector: Damage, Losses and Additional Costs 72

Table 30. Categories of Schools in The Bahamas 72

Table 31. Data on Public Sector Education Facilities, and Students 73

Table 32. Description of Damage of Affected Education Facilities

and Enrolment by Island 73

Table 33. Education Sector: Damage 75

Table 34. Listing of School Closures beyond 9 September 2019 77

Table 35.Education Sector: Losses 79

Table 36. Education Sector: Additional Costs 79

Table 37. Transport Sector: Damage, Losses and Additional Costs 81

Table 38. Roads: Damage 85

Table 39. Airports: Damage 86

Table 40. Ports: Damage 87

Table 41. Transport Sector: Losses 88

Table 42. Transport sector: Additional Cost 88

Table 43. Summary of Damage in the Telecommunications Sector 90

assessment of the effects

7

Table 44. Summary of Losses in the Telecommunications Sector 91

Table 45. Telecommunications: Additional Costs 91

Table 46. Power sector: Damage ($) 95

Table 47. Power Sector: Losses ($) 96

Table 48. Power Sector: Additional Costs ($) 97

Table 49. Households’ Access to Water 100

Table 50. Abaco: Private Dwelling by Type of Facilities and Source of Water 100

Table 51. Synthesis of the Data Collected on the Information Sheets (Data from 2017) 101

Table 52. Abaco: Average Tariff per Area 101

Table 53. Grand Bahama: Type of Facilities and Source of Water for Private Dwellings 102

Table 54. Water and Sanitation: Damage 103

Table 55. Water and Sanitation: Losses 104

Table 56. Water and Sanitation: Additional Costs 105

Table 57. Tourism: Damage 109

Table 58. Tourism: Losses by Type of Visitor 112

Table 59. Tourism: Losses by Type of Visitor and Year 112

Table 60. Tourism: Losses by Type of Expenditure 112

Table 61. New Providence: Losses by Type of Visitor 113

Table 62. Grand Bahama: Losses by Type of Visitor 113

Table 63. Abaco: Losses by Type of Visitor 114

Table 64. Rest Out Islands (including Castaway Cay): Losses by Type of Visitor 114

Table 65. Tourism: Additional Costs 115

Table 66. Fisheries: Damage 118

Table 67. Agriculture: Damage 118

Table 68. Fisheries and Agriculture: Losses 118

Table 69. Commerce: Damage 122

Table 70. Commerce: Losses 124

Table 71. Commerce: Losses by Year 124

Table 72. Commerce: Additional Costs 125

Table 73. Observed and Expected Qualitative Impacts of Hurricane Dorian 128

Table 74. Environmental: Damage, Losses, Additional Costs 129

Table 75. Environmental Sector: Damage 132

Table 76. Grand Bahama: Projected Damage to the National Reserves (Square Meters) 134

Table 77. Abaco: Projected Extension of Damage to the National Reserves 135

Table 78. Estimated Damage to Mangroves 137

Table 79. Damage to Coral Reefs 139

Table 80. Losses: Ecosystem Services 140

Table 81. Organic Debris Removal: Cost 141

Table 82. Grand Bahama: Fire cControl Measures 142

Table 83. Environmental Sector: Additional Costs 144

Table 84. Pillars of Action for Disaster Risk Reduction 152

Table 85. Summary of Recommendations by Pillar 153

Table 86. Subsector Specific Materials and Methods Recommendations 171

Table 87. Subsector Recommendations for Risk Reduction 172

list of figures

Figure 1. Path of Hurricane Dorian Across the Atlantic 26

Figure 2. Path of Hurricane Dorian in the Northern Caribbean and Western Atlantic 27

Figure 3. Path of Hurricane Dorian through Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama 29

Figure 4. Affected areas on Abaco Islands by Winds and Food 30

Figure 5. Affected Areas Marsh Harbour 31

Figure 6. Affected Areas The Mudd – Marsh Harbour 32

Figure 7. Affected Areas Sand Banks – North Abaco 33

Figure 8. Affected Areas Cays along Eastern Abaco 33

Figure 9. Affected Areas great Guana Cay 34

Figure 10. Affected Areas on Grand Bahama Island by Winds and Food 35

Figure 11. Affected Areas Grand Bahama Eastern Side of the Island 36

Figure 12. Affected Areas Grand Bahama Eastern Side of the Island (2) 36

Figure 13. Affected Areas Grand Bahama Eastern Side of the Island (3) 37

Figure 14. Effects of Hurricanes Joaquin, Matthew andIrma 39

figure 15. Marsh Harbour: Housing Damage Report 57

Figure 16. East Grand Bahama: Housing Damage Report 58

Figure 17. Before and After Images of the Damage at Abaco Central Primary School 76

Figure 18. Road Close to Shoreline 84

Figure 19. Deficient Asphalt Mixes 84

Figure 20. Lack of Tack Coat and not Uniform Granular Subbase 85

Figure 21. Collapsed Bridge in North Abaco 86

Figure 22. Airport Hangars Damaged in Marsh Harbour 87

Figure 23. Roof Damage in Marsh Harbour International Airport 87

Figure 24. RO plants and Water Distribution Systems 105

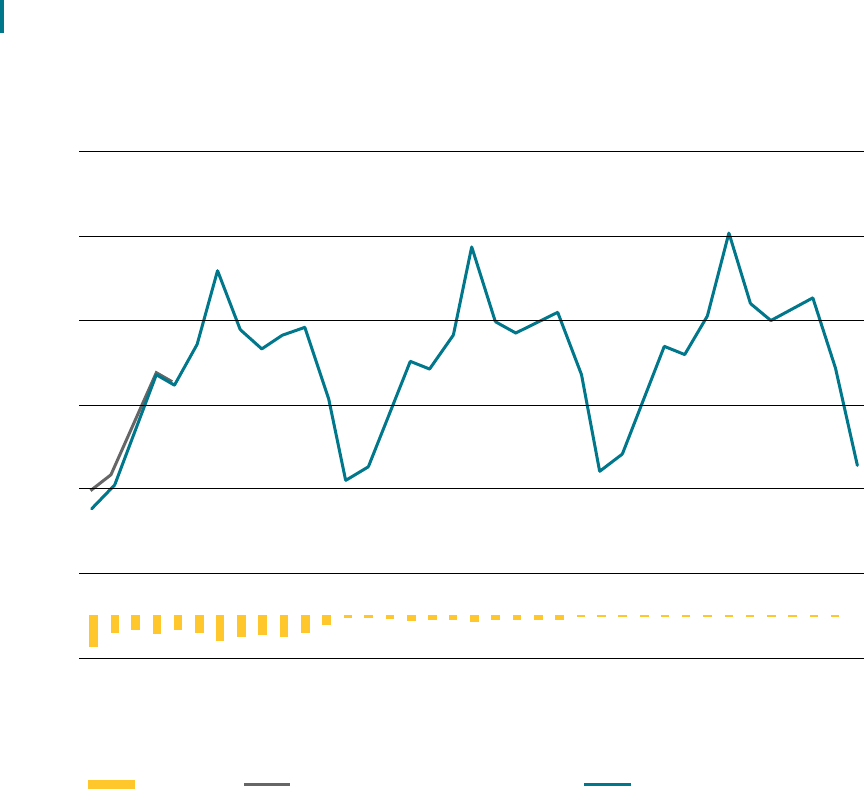

Figure 25.Bahamas: Forecasted Stopover Income and Losses (millions) 110

Figure 26. Abaco: Forecasted Stopover Income and Losses (millions) 111

Figure 27. Damage in non-Structural Elements 121

Figure 28. Damage Caused by Wind Force 121

Figure 29. Losses by Quarter in the Commerce Sector 123

Figure 30. Ecosystems on Abaco and Grand Bahama and Hurricane Dorian trajectory 127

Figure 31. Map of National Parks on Abaco and Grand Bahama 130

Figure 32. National Parks and Hurricane Dorian Trajectory 133

Figure 33. Damage in National Reserves on Abaco (1) and Grand Bahama (2, 3) 134

Figure 34. Status of Pine Forest on Grand Bahama 135

Figure 35. Status of Pine Forest on Abaco 136

Figure 36. Forest Fires Observed on Grand Bahama 136

Figure 37. Grand Bahama – Oil Spill at Equinor South Riding oil terminal 142

Figure 38. Grand Bahama – Oil Spill (Area: 398,537 sqm) 143

Figure 39. Grand Bahama before and during Hurricane Dorian 165

Figure 40. Marsh Harbour Elevation Areas 166

Figure 41. Mangrove Coastal Protection Scheme 166

Figure 42. FEMA Designing for Flood Levels Above the BFE,

Home Builders Guide to Coastal Construction 167

Figure 43.FEMA Foundation Requirements and Recommendations for Elevated Homes 167

assessment of the effects

9

Figure 44. Houses Next to Each Other in Treasure Key 169

Figure 45. Houses (Structure / Roof) Built in Wood 169

Figure 46. Damaged Road on Grand Bahamas Island 187

Figure 47. Damaged Dock on Grand Bahama 188

Figure 48. Collapsed Bridge in North Abaco 188

Figure 49. Structural Damage in the Airport on Abaco 189

Figure 50. Damage to non-Structural Elements in Freeport International Airport 189

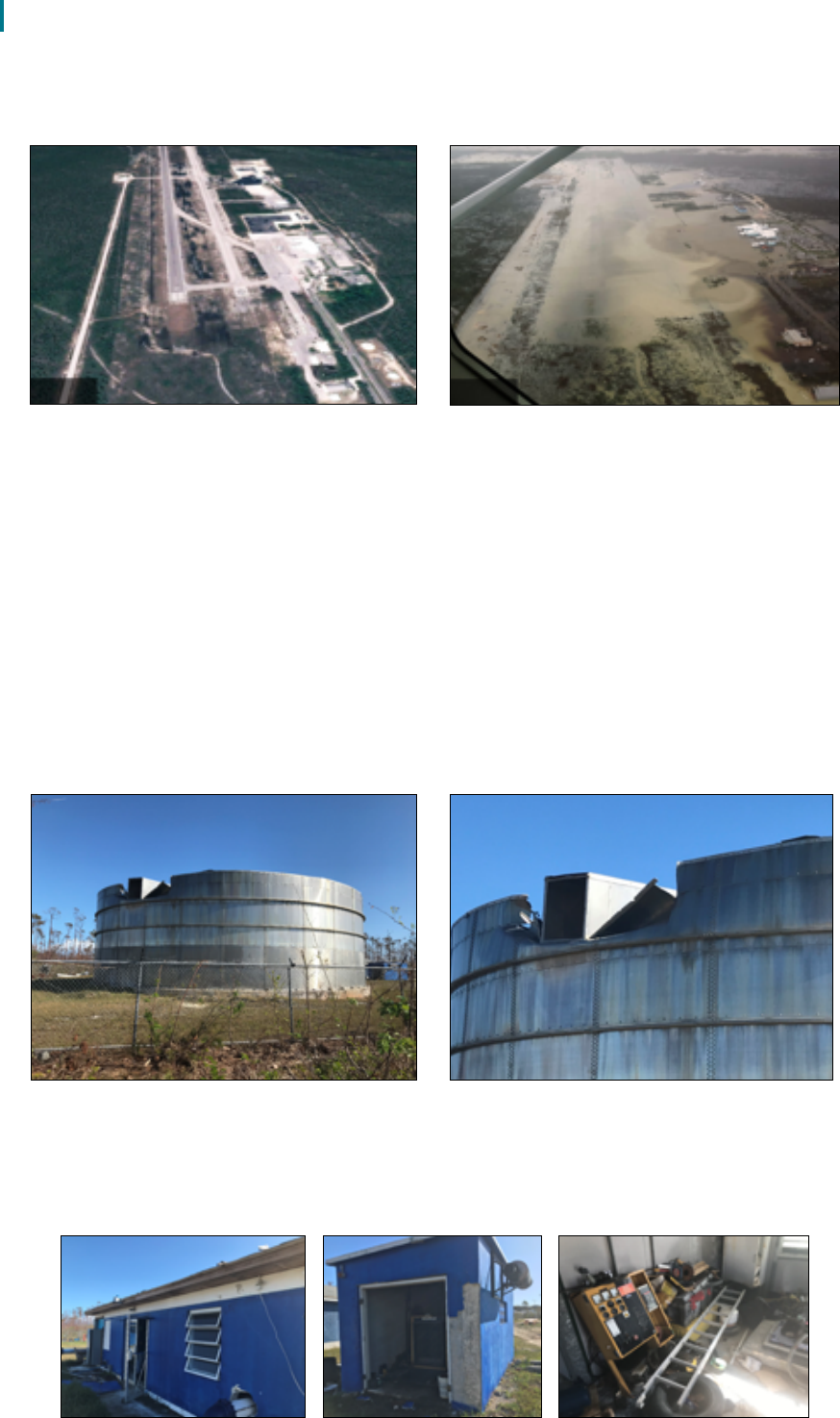

Figure 51. The Leonard M. Thompson International Airport 190

Figure 52. Main Storage Tank Damage in Marsh Harbour Pump Station 190

Figure 53. Damage to Pump Stations in Marsh Harbour and Treasure Key 190

Figure 54. Power Distribution Networks on Grand Bahama (via East End) 191

Figure 55. Sample of Small Scale / Enclosed RO Solar Plants 192

Figure 56. Sample of Small Scale / Enclosed RO Solar Plants 192

Figure 57. Piping Systems / Pumping Systems 193

Figure 58. Ground Water Collection System / Power Back Up 194

Figure 59. Fallen Cellular Tower with Destroyed base Transceiver Station 197

Figure 60. Damaged Recreational Dock 198

Figure 61. Spill at South Riding Point Oil Storage Facility Grand Bahama 200

Figure 62. Severely Damaged Power Plant at Marsh Harbour 206

assessment of the effects

11

acronyms

ARPU Average Revenue Per User

BEC Bahamas Electricity Company

BNT Bahamas National Trust

BPL Bahamas Power and Light

BTC Bahamas Telecommunications Company

CARILEC Caribbean Electric Utility Services Corporation

CCRIF Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility

CDEMA Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency

CVI Coastal Vulnerability Index

DALA Damage and Loss Assessment

ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America

EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

GBPA Grand Bahama Port Authority

GBPC Grand Bahama Power Company

GBUC Grand Bahama Utility Company

GDP Gross domestic product

GFDRR Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery

IDB Inter-American Development Bank

MEH Ministry of Environment and Housing

MoEST Ministry of Education, Science and Technology

MOH Ministry of Health

MOW Ministry of Works

MRAG Marine Resources Assessment Group

NatCap Natural Capital

NEMA The Bahamas’ National Emergency Management Agency

NGO Non-government organization

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NPDC New Providence Development Company

PAHO Pan American Health Organization

PHA Public Hospital Authority

assessment of the effects

13

executive summary

introduction

Hurricane Dorian is not an isolated occurrence, but the latest example of recurrent extreme

climate events that have changed the Bahamian landscape and impacted its economy. The increase

in water temperatures is likely to contribute to a tendency for tropical storms to be, on average,

stronger than they have been in the past (Bruyere, Holland, 2014; Balaguru, Foltz 2018; Bathia,

Vechia et al, 2019; Trenberg, Cheng et all, 2018). Due to its location in the Atlantic hurricane belt

and like other Small Island Developing States (SIDS), The Bahamas is extremely vulnerable to the

effects of disasters and climate change, as some 80 percent of the landmass is within 5 ft (1.5 m) of

mean sea level and coastal areas hold the majority of the population and economic activity. Another

relevant vulnerability is access to drinking water, which is made worse by contamination of water

resources caused by storm surges. In the upcoming years, the country will face difficult questions of

whether to relocate coastal populations and how to smartly invest in more resilient infrastructure.

It is, therefore, imperative for The Bahamas, as a country, to establish a comprehensive approach

to meeting these challenges and to incorporate considerations for disaster risk management into all

features of national development.

Disasters are described as a combination of exposure to hazard and conditions of vulnerability.

Greater vulnerability is usually linked to socio-economic and territorial aspects, as poorer

populations tend to live in at-risk areas disregarded by formal planning systems, all but ensuring

a greater exposure to hazards. This exposure of social and economic assets to hazards can be

somewhat balanced with measures to mitigate vulnerabilities, such as investments in early warning

and preparedness, and addressing pre-existing social issues such as informal settlements.

Disasters set accomplishments back in social and economic arenas and put a strain on national

budgets. This is of concern for The Bahamas, a country not eligible to receive official development

assistance (ODA) and where government debt, for example, doubled from 32 percent of GDP in

2007 to 65 percent of GDP in 2014. In this regard, the DaLA assessments of Hurricanes Joaquin,

Mathew, Irma and now Dorian offer a historical record of the cumulative effects and impacts

on economy, infrastructure and society from recurrent disasters and offers guidance for future

decision-making processes.

In The Bahamas, the characteristics of its territory and dispersed population in the Family Islands

adds extra challenges for planning and recovery. Settlements are usually dispersed and contain

small populations, which increases the costs associated with the provision of public utilities and the

development of infrastructure which needs to be extended for long distances to supply communities.

Dispersion of population also contributes to inequitable access to social services of varying quality.

Additionally, the islands face economic vulnerabilities. Tourism and fishing are, together with public

employment, a plurality of the jobs in the Family Islands. Dorian, like other hurricanes, caused

widespread damage that directly and indirectly affected these productive activities.

The Bahamas has made important efforts in mitigating risks and improving resilience through

instruments such as hard engineering and a modern building code, along with the enactment of the

Disaster Preparedness and Response Act from 2006 (amended in 2011). The subjects dealt with

in the Act are also reflected in the Vision 2040, the National Development Plan of The Bahamas,

which frames the country’s development agenda within the Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs). Nevertheless, the effects of Hurricane Dorian brought to light many areas that still require

improvement, not only in terms of physical risk, but in social and economic aspects.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

14

Resilience involves identifying these risks and developing measures to reduce them, such as

enhancing infrastructure and land-use planning and financial protection. Addressing physical

vulnerability must be accompanied by social policies to protect the livelihoods of the most vulnerable

groups. Special attention should be given to the particularities and constraints of the Family Islands,

such as the challenges to enforce and verify compliance with building codes. Specific policies and

programs and possibly additional financial resources should address these. Education and public

awareness are also important mechanisms and should be a crosscutting component of any disaster

risk management plan. Although a strong system of risk modeling and disaster data management is

a must, the population needs to understand the kind of risk they are exposed to and be provided

with the tools and capacity to act accordingly at times of emergencies.

On 1 September 2019, the eye of Hurricane Dorian made landfall on the Abaco islands with

maximum sustained winds of 185 mph (280 km/h), wind gusts over 220 mph (335 km/h), and central

barometric pressure of 911 millibars (26.9 inHg). Abaco and its cays along the eastern side were the

most affected areas. According to the trajectory of the hurricane, the central and northern part

of the island were affected by hurricane force winds, storm surge and flooding. According to the

Bahamas Department of Meteorology, the storm surge provoked storm tide of 20 to 25 ft (6.1 to

7.6 m). Dorian also dropped an estimated 3 ft (0.91 m) of rain over The Bahamas. Therefore, Dorian

is considered the strongest hurricane on record to affect The Bahamas, not only because of its wind

intensity, but also due to the storm surges. The storm surges provoked extensive damage in the

most proximal zones to the coasts and lowlands.

On 2 September, the eye of Dorian moved over the eastern side of Grand Bahama and drifted across

the island as a Category 5. The hurricane then stalled over Grand Bahama for another day, finally

pulling away from the island on 3 September. According to the descriptions of the Department of

Meteorology, storm surge and flooding were the events provoked by hurricane Dorian that caused

the most severe damage, especially in the eastern side of the island. The flooding on Grand Bahama

began from the north and northeast towards the south of the island, this phenomenon was due to

the trajectory of the hurricane and the period that Dorian remained in the northern part of The

Bahamas in open ocean.

After hurricane Dorian and the provision of initial emergency services, the government of The

Bahamas asked the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to assess the resulting damage,

losses and Additional costs. The IDB requested the United Nations Economic Commission for

Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) for technical assistance with the assessment. This

report presents the results of this assessment. It also brings recommendations to guide a resilient

reconstruction process that can reduce vulnerabilities and risks for the population and for every

sector of the economy. Since 2015, it is the fourth assessment in this kind conducted by IDB and

ECLAC in The Bahamas.

The report is divided into two sections. The first section contains the description of event,

affected population and detailed explanation of damage, losses and Additional costs in all social,

infrastructure and productive sectors. Additionally, this part includes an analysis of environmental

effects and the macroeconomic impact. The second part introduces recommendations for resilient

reconstruction based on the findings of technical experts and best-practices and is divided in five

pillars: risk identification, risk reduction, preparedness, financial protection and resilient recovery.

The upcoming section will summarize the main findings and the document and briefly describe the

conclusions of each chapter. All monetary estimates are made in Bahamian dollars; to simplify the

symbol $ is used.

assessment of the effects

15

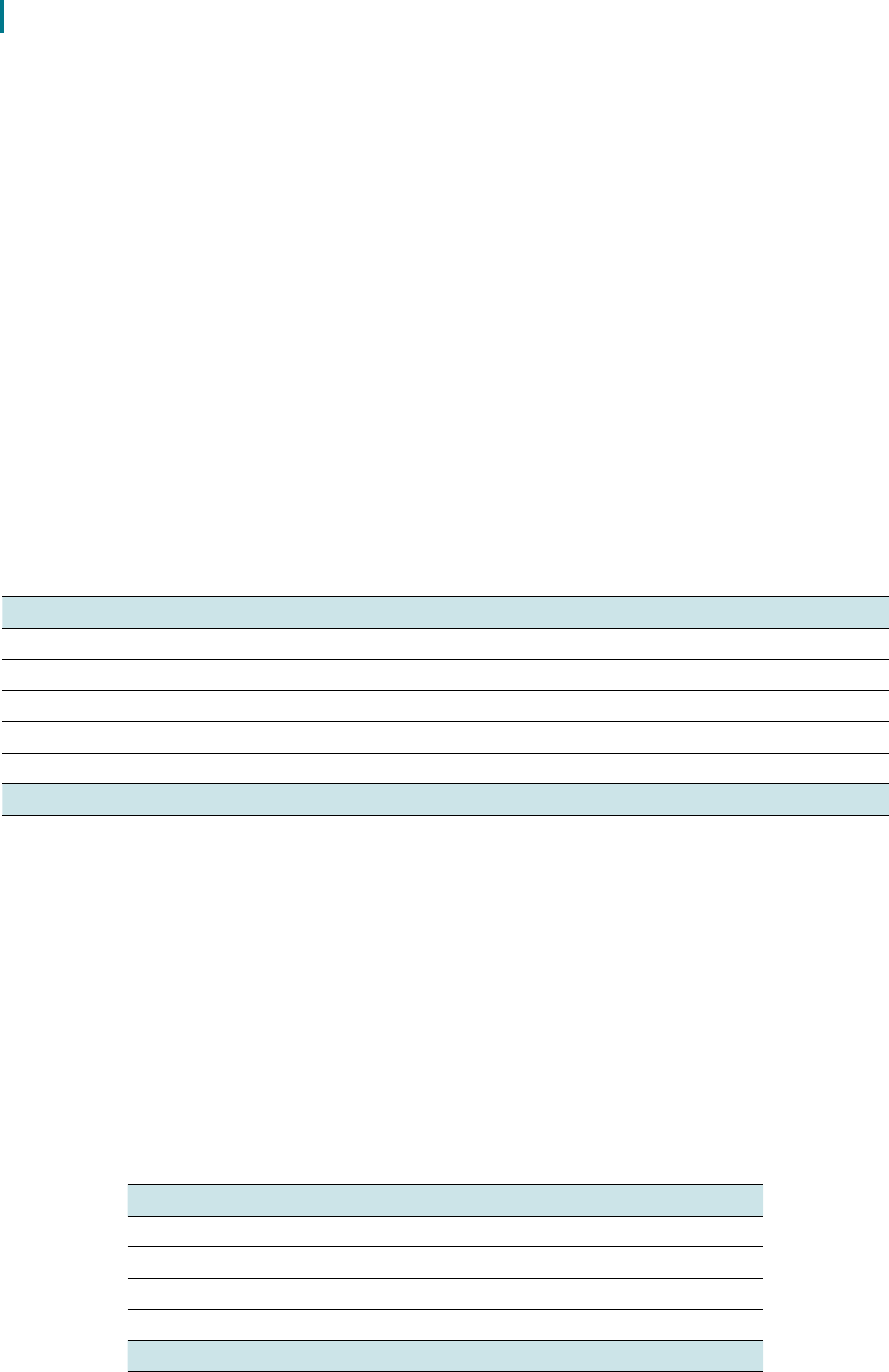

summary of damage, losses and additional costs

Hurricane Dorian’s greatest impact was felt on Grand Bahama and Abaco, although some impact

also occurred on the island of New Providence. Damage resulted from high winds and storm surge

and was exacerbated by poor construction practices and communities and infrastructure located

in vulnerable areas. Given the magnitude of this event, the reconstruction efforts will last many

years and it will require major assistance from financing institutions. Reconstruction is expected to

be a long-term process, which tests the strength of a country’s institutions. However, it is important

that those directly affected by the disaster feel the presence and solidarity of the government

throughout the process.

The costs consist of three elements: direct physical damage, revenue and other income losses,

and Additional costs—chiefly debris removal. Table 1 summarizes estimates of Damage, Losses

and Additional costs for the four primary sectors on the affected islands: social, infrastructure,

productive and environment. The estimated damage is $2.5 billion, of which nine percent is public

and 91 percent private.

1

Abaco suffered 87 percent of the damage and Grand Bahama 13 percent.

Losses are estimated as $717.3 million and were sustained primarily in the private sector,

which accounted for 84 percent of the total. (Seventy percent of the losses took place on Abaco,

15 percent on Grand Bahama, and nine percent in other islands.) Additional costs add up to

$220.9 million, 46.4 percent of those costs were in the environment sector and are associated

to the cleaning of the oil spill. A major part of the remainder of the additional costs is related to

debris removal and demolition.

Damage in the social sector was $1.6 billion, 85.3 percent took place on Abaco. Ninety-three

percent of the damage was in housing, 4.6 percent in education while 2.4 percent occurred in the

health sector. Approximately 93.8 percent of the damage in the social sector happened to private

property and the remaining 6.2 percent in public property. The productive sector suffered damage

estimated to be $620.9 million, most of them in tourism ($529.6 million), followed by commerce

($77.6 million), and fisheries and agriculture ($13.6 million). All damage in the productive sector

happened in the private sector. Infrastructure experienced damage amounting to $239.1 million.

The power sector represents 54.1 percent of the total. The telecommunications sector suffered

damage of $42.1 million, transport accounted for $50.8 million and water and sanitation $14.9

million. Approximately 48.6 percent of the damage in the infrastructure sector was to private

property and the remaining 51.4 percent was to public property. 66.8 percent of damage of the

infrastructure sector took place on Abaco.

We estimate that about 38 percent of the damages were insured. Note that the damage estimate

is based on the replacement cost of the asset. For example, in the commerce sector, in the case

of destroyed establishments, our estimate seeks to approximate what is the replacement cost of

that infrastructure, not its market value. The latter includes, for example, the value of the land. In

general, the amount of insurance is based on market value, not as much as a similar infrastructure is

worth replacing. Therefore, our estimates of the insured amount are intended to approximate the

percentage of assets whose replacement costs could be financed in this way. In the specific case of

the housing sector, it is expected that in the insurance there will be a bias towards those of greater

value and that it is influenced by the homes that had a mortgage. In this sense, we estimate that 30

percent of the damages in the housing sector were insured and that 14 percent of the properties

were insured.

1 The distinction between public or private is made on the basis of ownership of the asset, not on who will pay for

its recovery. For example, many of the airports damaged are privately owned. The damages in these facilities are

classied as private, regardless on who ends up paying for its recovery. We know that in this cases, some private

infrastructure will get public resources to rebuilt, unfortunately at this point is not possible to precise which

infrastructures and to what extent, will get public funding.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

16

Losses for the social sector are estimated to be $93.2 million, of those $65 million were in

housing, $21.4 million in health and $6.7 million in education. Losses in the

Environmental sector were estimated at 27.5 million. Losses for the productive sector were

estimated at approximately $400.3 million. Abaco suffered 83.8 percent of those losses.

Tourism accounted for most of the losses (81.2 percent) and suffered the greatest effects. This

sector suffered a loss of $325.2 million. The losses in commerce were $65 million and in fisheries

and agriculture, $10.1 million. All losses to the productive sector were private. The losses in

the Infrastructure sector were estimated at $197.1 million. Most of the losses were in the

power sector (35 percent), followed by telecommunication (27.6 percent). The losses in

water and sanitation and transportation were near $19 million each. The public losses in

the infrastructure sector were smaller (38.8 percent) than the private sectors (61.2 percent).

Abaco suffered 60 percent of the losses of the infrastructure sector.

Additional costs were estimated as $220.9 million, 46.4 percent of those costs were

in the environment sector associated to the cleaning of the oil spill. The additional costs of the social

sector were $82.6 million, followed by the productive sector, $20 million, and infrastructure,

$16.2 million. An important part of these costs is related to debris removal and demolition. Costs

associated with the emergency response were only partially provided, for example, costs of

evacuation were not made available at the time of the finalization of the report.

TABLE 1. SUMMARY OF EFFECTS OF HURRICANE DORIAN

Damage Losses Additional costs

Social 1,597,290,766

93,163,186

82,254,021

Housing 1,487,167,663 65,014,267 57,809,391

Education 72,406,603

6,799,026

19,100,000

Health 37,716,500 21,351,380 5,344,630

Infrastructure 239,135,274 197,136,671 16,236,779

Power 131,355,000 68,924,558 6,335,000

Telecommunications 42,150,000 54,380,149 1,039,960

Water and Sanitation 14,853,000 36,624,014 2,289,200

Transport 50,777,274 37,207,950 6,572,619

Productive 620,650,850 400,285,030 19,954,141

Tourism 529,550,208 325,199,267 15,146,625

Commerce 77,584,545 64,973,002 4,807,516

Fisheries and Agriculture 13,516,097 10,112,761

Environment 7,146,963 27,435,048 102,473,000

Total $2,464,223,852

$718,019,935

$220,917,941

Source: Assessment team 2019

In 2019, The Bahamas economy was expected to grow by 2.2 percent. The estimated impact of

Hurricane Dorian is one percentage point of the GDP. This implies that post-disaster, the economy

is expected to grow 1.2 percent. This will result in a decrease in salaries of $42 million and capital

income of $59.9 million. The situation is different when the focus is on local economic activity. In

the case of Abaco, the impact was estimated at 7.1 percent of its GDP, which is estimated to be

47 percent and 60 percent decrease of the country’s remuneration and capital, respectively. On

Grand Bahama, the impact was 1.9 of its GDP.

assessment of the effects

17

methodological approach

The assessment of the effects and impacts caused by Hurricane Dorian follows the Disaster

Assessment Methodology developed by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the

Caribbean. The methodology allows standardized data collection and analysis on a sectoral basis,

applying the same criteria to every sector under study. In this regard, the following concepts are

used in the assessment

2

:

(i) Effects: Damage, Losses and Additional costs

– Damage: the effect the disaster has on the assets of each sector, expressed in monetary

terms

Assets may include buildings, machinery, equipment, means of transportation,

furnishings, roads, ports, stocks of final and semi-finished goods, among others.

– Losses: goods that go unproduced and services that go unprovided during a period

running from the time the disaster occurs until full recovery and reconstruction is

achieved

– Additional costs: outlays required to produce goods and provide services as a result of

the disaster

These represent a response by both the public and the private sectors, and may take the

form of additional spending or a recomposition of spending.

(ii) Impacts: consequences of the effects on macroeconomic variables, such as GDP, public

finance and balance of payments

Based on the information gathered during field visits and interviews, the social sector analysis

focuses on affected population, housing, health and education. The infrastructure sector comprises

transportation, telecommunications, power and water and sanitation. The productive sectors

analyzed are tourism, and agriculture and fisheries. Additionally, the report includes a cross-cutting

assessment of the effects suffered by the environmental sector. The Assessment team visited

The Bahamas from 31 September to 5 October 2019 to collect data and obtain an overview of

the effects of the hurricane on the country. Between 1 and 2 of October, team members visited

the most affected areas, including Eastern Grand Bahama, Freeport and Marsh Harbour, as well

as the surrounding regions. In addition, the Assessment team held meetings and interviews with

representatives from government agencies responsible for each sector under analysis.

The assessment was carried out using official data provided by the government, interviews with the

private sector and academia, and observations from the field visits. However, as it will be detailed in

each pertinent sector, the main limitation of the assessment was access to information, either due

to unavailability during the assessment or because it is not yet collected/produced in the country.

This limitation was overcome by creating reasonable assumptions where data was unavailable. Both

official information and informed assumptions were used to estimate the effects of the hurricane

and are presented in each section.

2 ECLAC (2014), Handbook for Disaster Assessment

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

18

summary of affected population

Most inhabitants of Abaco and Grand Bahama were affected by the passage of Hurricane Dorian

in one way or another. The Assessment team estimated that approximately 29,472 persons were

affected by the hurricane as a result of some sort of damage to their homes and assets. There were

67 confirmed deaths and 282 persons still missing as of 18 October 2019. The number of related

injuries recorded by the health authorities was over 200 a week after the passage of the hurricane.

Approximately 4,861 persons were registered by the Department of Social Services during the

evacuation process. However, it should be noted that not all evacuees would have been accounted

for, as some used private transport to evacuate to Eleuthera and the United States of America.

With the passage of Hurricane Dorian, the government was faced with accommodating thousands

of displaced persons in shelters across New Providence, in some cases up to two months after the

event. The number of displaced persons in shelters on Abaco and Grand Bahama was comparatively

less as most had evacuated to New Providence.

In terms of access to services, most of the population of Abaco and Grand Bahama suffered

interruptions in utilities like telecommunications, electricity and water. Approximately 10,546

students were affected as a result of a suspension of primary and secondary school classes in both

islands. This created a significant loss in teaching time, as most school facilities were damaged in the

affected islands. Furthermore, a great number of the population employed in the commerce and

tourism sectors experienced disruptions in employment due to damaged properties.

In addition to the regional and international partners that aided in the early phases of emergency

and relief response, the government of The Bahamas, through its various institutions, allocated

around $7 million for the attention of the emergency and relief efforts.

summary of housing and public buildings

Housing was the sector most severely affected by Hurricane Dorian. Several residential settlements

along or near the coastline suffered heavy damage as a result of the intense force of winds and

storm surge or was impacted by falling trees and flying debris. Houses and residences suffered

significant damage to the structural elements, roofs, flood damage, and other components of the

buildings.

Approximately 9,000 homes and in excess of 11 million square feet of structures have sustained

some damage on the two islands. On Abaco more than 75 percent of the dwellings were somehow

affected, approximately 57 percent of the houses were severely damaged. Central Abaco (Marsh

Harbour), Treasure Cay, and Hope Town were the most affected locations. Vulnerable settlements

in Marsh Harbour were also destroyed. Damage to the housing sector on the islands of Abaco and

Grand Bahama is estimated at $1.48 billion, 88.9 percent of which took place on Abaco.

Losses in the housing sector are attributed to the interruption of accommodation and rental

services due to severe damage or destruction of the house, making it temporarily or permanently

uninhabitable. The Assessment team estimated losses at $56.8 million resulting from 2,894 homes

left uninhabitable after the hurricane.

Additional costs included in this assessment are refer to the cost of demolition of the most affected

dwellings, debris cleaning, and labor and equipment rental cost. Additional costs are estimated

at $57.8 million.

assessment of the effects

19

In total, 31 public buildings (excluding schools, hospitals/clinics and shelters that were assessed

in other

sectors) and government offices were affected. Damage to the public building sector is

estimated at $10.6 million. Additional costs to demolition and debris removal in public buildings are

estimated at $1.0 million. There was no losses related to public buildings.

summary health

The hurricane severely affected the infrastructure, equipment, medical supplies and electrical

and water supply on Abaco and Grand Bahama. Therefore, the capacity of the healthcare delivery

system has been significantly hampered on Abaco and Grand Bahama.

Hurricane Dorian damaged most of the healthcare facilities in both affected islands, with severe

damage to the Rand Memorial Hospital (RMH) and four clinics located in the eastern part of Grand

Bahama. Additionally, significant damage was also evidenced in medical equipment, furniture, and

vehicles from extensive and prolonged flooding, very high humidity and high temperatures during

and after the storm. The estimated damage in infrastructure, medical equipment, furniture, supplies

and others to the health sector on Abaco and Grand Bahamas attributable to hurricane Dorian has

been estimated in $37.7 million.

A total of $21.4 million is the estimated cost of health services operations disruption. The disruption

covers three time periods: before, during and after the hurricane.

Additional costs are related to the emergency response and provision of temporary relief and are

estimated as $5.3 million

summary of education

Following the passage of the category 5 Hurricane Dorian, Grand Bahama and Abaco were the

two hardest hit islands, incurring widespread damage to most educational facilities. Across the both

islands, there were 45 educational facilities experiencing varying levels of damage with 10,546

students and 796 teachers affected. Seven schools were altogether destroyed. On Abaco, there

were 23 educational facilities impacted with 3,512 students and 211 teachers affected while Grand

Bahama had 24 educational facilities impacted with 7,034 students and 585 teachers affected. At

the time of this report and following the registration drive conducted by the Ministry of Education,

approximately 1,500 displaced students had been reassigned to alternative schools across the

islands of The Bahamas.

The widespread damage to educational facilities amounted to $72 million. Losses in the subsector

which comprises the estimated value of lost instruction time along with the value of tuition

refunds for students no longer returning for post-secondary level education totaled $6

million. The remaining costs included Additional costs incurred during the recovery efforts,

which amounted to $19.1 million. They include the removal of rubble, school furniture to

accommodate re-assigned students and teachers, special equipment to conduct classes,

fencing, security, school meals, payment of grants, security, psychosocial support to teachers

and staff, enrollment fees and costs associated with the enrollment drive conducted by the

Ministry of Education for displaced students. The estimated costs across the two islands were

equally distributed despite the student and teacher population on Abaco being significantly

smaller than that of Grand Bahama; an indication of the magnitude of the damage on Abaco.

Public sector institutions incurred the brunt of the costs across the affected islands with a total

estimated cost of $74 million. The limited data available on private sector schools across the

both islands contributed to the significantly smaller private sector cost.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

20

summary of roads, airports and ports

The transport infrastructure, including roads, ports and airports was damaged on Abaco and Grand

Bahama. Structural damage was related to storm surge and high-speed winds and the most affected

infrastructures were located near the shore. The airports suffered high operational damage due to

flooding and roof failure due to high-speed winds, and seaports were impacted by waves, storm

surge, and wind.

The estimated transportation infrastructure damage is approximately $51 million for the whole

country, 53 percent of the damage took place on Grand Bahama, where 93 percent was sustained

at the Grand Bahama International Airport.

The losses are estimated considering the decrease in tourism and cargo in both Abaco and Grand

Bahama and its effects on the collection of port charges and services. The estimated economic

losses associated with the interruption of transportation services is $37 million. It is estimated that

44 percent of the losses will take place in 2019, 39.2 percent in 2020 and 16.8 percent in 2021.

Finally, the additional costs associated with the construction of temporary infrastructure and

removal of debris are $6.6 million.

summary of telecommunications

The telecommunications sector suffered considerable damage to infrastructure because of

Hurricane Dorian. Gale force winds caused damage to above ground network elements, while

flooding caused unexpected damage to various types of ground level telecommunications

equipment. Total damage to the telecommunications sector was estimated at $42.1 million. Water

damage to electronic systems rendered many parts of the network inoperable during and after

the hurricane, whilst the high saline content of the floodwater caused corrosion to various types of

wiring and conductors. Due to the high flood levels, buried fiber optic cables and copper wires were

damaged to the point where they emerged from the ground to connect to above ground equipment.

Heavy winds also caused the more typical type of damage associated with hurricanes, seriously

damaging wireless infrastructure such as antennae, base transceiver stations and satellite dishes.

The losses are estimated at $54.4 million and the most significant losses occur on Abaco, where

services could not be provided to end users due to widespread destruction. Losses estimates were

projected until December 2021, as recovery is expected to take at least this time or even longer to

return to normal levels. An estimated loss of $13.7 million was made for the remainder of the year

2019; $16.3 million for the year 2020; and $24.4 million for the year 2021. Losses were primarily as

a result of the absence of commercial power, the extended time needed for network restoration, and

the loss of clientele. On Abaco, where the effects of the hurricane were the hardest, it is expected

that there will be a long road to recovery of the services that require a wired telecommunications

network infrastructure.

Additional costs were estimated at approximately one million dollars, mainly reflecting the labor-

related costs required to perform repairs, as well as generator fuel burned in the absence of

commercial power.

summary of power

Hurricane Dorian caused extensive damage to the power generation, transmission and distribution

systems on the islands of Abaco and Grand Bahama.

assessment of the effects

21

Total damage in the power sector was estimated at $131.3 million, of which the largest line-items

were $80.4 million in damage to the transmission and distribution networks on Abaco and $21

million in damage to the flooded power generation plant on Grand Bahama.

Total losses were estimated at $68.9 million, reflecting the value of power that was not sold, both

because of damage to the transmission and distribution network and because of the reduction in

demand for electricity as a result of storm damage. Losses were estimated until December 2021 as

recovery is expected to take at least this time or even longer to return to normal levels. An estimated

loss of $22 million was made for the remainder of the year 2019; $40 million for the year 2020; and

$6.8 million for the year 2021.

Additional costs were estimated at $6.3 million, which mainly reflects extraordinary labor and

labor-support costs.

summary of water and sanitation

Damage to facilities and assets associated with water and sanitation are estimated at $14.8 million.

The hurricane primarily affected water pumping systems, storage tanks, distribution system and its

related damage related to WSC assets that were destroyed in the event.

Losses are related to interruption of piped water service both residential and other economic

sectors, losses of volumes of water due to system leaks, sewerage and waste collection and

estimated at $36.6 million. The decrease in water demand during the recovery period due to the

decline in tourist numbers and commercial activity is considered a loss through the end of 2019

for an estimated period of 28 months on Abaco and six months on Grand Bahama as well as an

estimated of loss of demand from 7,339 severely damage houses on both Islands.

Additional costs such as additional labor and construction equipment, emergency power generation

and solid waste management is estimated at $2.3 million. These costs also referred to the expense

of managing cleaning activities, costs for disaster assessment and recovery teams deployed, and

payment to fulfill restoration work.

summary of tourism

Hurricane Dorian impacted two major tourist destinations of The Bahamas and disrupted the

tourist flows for several days before and after the storm in the rest of the Lucayan Archipelago.

The hurricane also caused significant damage to tourism infrastructure on Abaco and in East End

of Grand Bahama; in some locations the damage was catastrophic. The total damage in the tourist

sector was $530 million. A large majority of the damage occurred on Abaco.

In this occasion the forecasted losses are less than the damage and amount to $325 million. They

are related to the disruption in the flow of tourists as result of the storm and a changed public

perception due to the damaged structures. Most of the losses will be accrued in the high season of

2019 and 2020, tapering off as the recovery is expected to gain momentum.

There were also additional costs for $15 million related to demolition, debris removal and salvaging

of sunken ships.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

22

summary of fisheries and agriculture

The impact of Hurricane Dorian in the fisheries and agriculture sector of Abaco and Grand Bahama

was significant. All the fishing processing facilities were affected, either by wind damage or storm

surge, with all the consequences of water damage. For the agricultural sector, several green houses

were decimated, and many perennial crops were damaged by wind and salt-water intrusion. A

poultry processing facility was also destroyed on Abaco.

The total damage in fisheries was $11 million including damage to vessels, processing facilities and

fishing gear. Considering the seasons for spiny lobster and stone crab, the losses in fisheries will be

$7.0 million and will represent a big fraction of the total losses. In agriculture the losses will be $2.0

million, considering perennial and annual crops, and for poultry, over $1.5 million. The total losses

for fisheries and agriculture are estimated at $10 million.

summary of commerce

The effect on the commerce sector was greater on Abaco than Grand Bahama due to the path of

the hurricane, as the eye of the storm passed through the commercial center of Marsh Harbour.

The structures that were made of concrete survived with less damage, while those made of lighter

materials fared much worse. The total damage was estimated at $77.5 million for the commerce

sector: $71.4 million on Abaco, and $6.2 million on Grand Bahama.

The losses to the sector are projected to occur over the expected length of recovery. On Grand

Bahama, the losses are expected to accrue over just four months, while on Abaco it is expected to

take a full three years. Due to the destruction of property and vital infrastructure, as well as the

evacuation of residents, commercial expenditure will fall to zero in the month of the disaster and

then gradually make its way back to pre-disaster levels as the recovery goes on. The total losses

estimated for the commerce sector are $65 million: $64.5 million on Abaco and $0.5 million on

Grand Bahama. Assessing over time, losses will be $22.1 million or 34 percent of the total in 2019,

$34.9 million or 54 percent in 2020, $7.2 million or 11 percent in 2021, and 0.8 million or 1 percent

in 2022.

The additional costs for this sector comprise debris removal and demolition. At the time of the

Assessment team’s site visit to Abaco, there was still an extensive amount of debris in Marsh

Harbour. Debris removal and demolition of damaged properties will be expensive and will take

additional time on Abaco. The total Additional costs for the commerce sector are estimated at $4.8

million: $3.8 million on Abaco and $1 million on Grand Bahama.

summary of environment

Although previous assessments in The Bahamas indicate that ecosystems in the country have

adapted over time to become resilient to tropical weather, the intensity and duration of Hurricane

Dorian still caused moderate to significant environmental effects. Wave action, storm surge and

high winds have produced partial to severe destruction to mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass beds

and forests on both Abaco and Grand Bahama. As a result, ecosystems were left in a critical state

and pre-existent vulnerabilities were exacerbated with an expected decrease in ecosystem services

provision in the short and medium term. These ecosystems are home to a wide variety of species of

flora and fauna and provide services that are essential to the development of the country.

Damage to mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass beds and protected areas account for around $7 million.

This damage is a product of impacts on coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangroves, beaches and on the

assessment of the effects

23

infrastructure of protected zones. Due to the inherent difficulty of assigning a price tag to some

of these assets, the value reflected in this damage estimation is only based on a global average of

the cost of restoration projects. Numbers could go higher depending on factors such as equipment

availability, local workforce, planning and monitoring.

The impacts to natural resources are not only expected to cause changes in biodiversity,

disappearance of habitats, and displacement of species, but also affect Bahamians who depend

on healthy ecosystems to maintain their livelihoods and economies. For example, the damage

to seagrasses beds is likely to have short- to medium-term effects (2 to 4 years) on the services

they provide to fisheries, which makes the losses represent the most significant public costs. Since

ecosystems are crucial to the economy and society in The Bahamas, it is expected that the impacts

of the hurricane on their ecosystem services will result in losses of approximately $27 million.

Additional costs entail the costs of future environmental assessments, organic debris removal, fire

control measures and a significant private cost related to the oil spill on Grand Bahama. These costs

are estimated to be $102 million.

These estimates are based on a limited amount of information available at this time and on initial

assessments, long term impact studies will be further required. There are also environmental

elements that suffered damage (such as water resources) for which there is no economic

quantification due to the limited availability of information.

assessment of the effects

25

description of event

Hurricane Dorian was the first major hurricane of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season. The National

Hurricane Centre (NHC) originally identified a tropical wave within a monsoon through over Guinea

and Senegal in western Africa. This system was disorganized for several days, and on 23 August

it consolidated, and thunderstorm activity increased. On 24 August the system was classified as

Tropical Depression Five because the system acquired enough organized convection. A deep ridge

imparted westward movement of the depression, steering it toward the Lesser Antilles. A small

cyclone developed a defined inner core with a 12-mile-wide eyelike feature. Therefore, the system

intensified into a tropical storm; it was assigned the name Dorian by the NHC. Rain bands gradually

wrapped more around Dorian on 25-26 August though convection remained inconsistent.

Dorian continued moving west and passed close to Barbados, bringing tropical storm-force winds

and heavy rain. On 27 August Dorian made landfall on the island of Saint Lucia as a tropical storm

and then entered to the Caribbean Sea. The storm underwent a center relocation further north,

to the west of Martinique, experiencing tropical storm force winds. Dorian took a more northerly

track than expected, passing to the east of Puerto Rico, and hit the US Virgin Islands. On 28 August

Dorian intensified into a Category 1 hurricane as it approached Saint Thomas in the US Virgin

Islands. On 29 August the system moved north and entered a more favorable environment and

it started to rapidly intensify, reaching Category 2 status on the first hours of 30 August. Rapid

intensification continued, and the storm eventually reached major hurricane status several hours

later, on the same day. The system continued strengthening, and on 31 August Dorian attained

Category 4 major hurricane status.

On 1 September, Dorian reached Category 5 intensity and made landfall at 16:40 UTC on Great

Abaco Island in the Bahamas, with one-minute sustained winds of 185 mph (280 km/h), wind gusts

over 220 mph (335 km/h), and central barometric pressure of 911 millibars (26.9 inHg). The storm´s

central pressure bottomed out at 910 millibars (26.87 in Hg) within a few hours, as Dorian reached

its peak intensity during landfall as it passed through Marsh Harbour. Hurricane Dorian´s forward

speed decreased around this time, slowing to a westward crawl of 5 mph (8 km/h). At 02:00 UTC

on 2 September Dorian made landfall on Grand Bahama at near the same intensity. Afterward

Dorian´s forward speed slowed to just 1.2 mph (1.9 km/h), as the Bermuda High

3

that was steering

the storm westward weakened. Later that day, the storm underwent an eyewall replacement cycle

to the north of Grand Bahama; the Bermuda High to the northeast of Dorian also collapsed, causing

Hurricane Dorian to stall just north of Grand Bahama. Around the same time, the combination of

the eyewall replacement cycle and upwelling of cold water caused Dorian to begin weakening, with

Dorian dropping to Category 4 status at 15:00 UTC. Due to the absence of steering currents,

Hurricane Dorian stalled north of Grand Bahama for about a day. Hurricane Dorian subsequently

weakened to a Category 2 storm on 3 September, before beginning to move north-westward at

15:00 UTC, parallel to the east coast of Florida, with Dorian´s wind field expanding during this time.

On 5 September, Dorian moved over the warm waters of The Gulf Stream and re-intensifying

into Category 3 hurricane off the coast of South Carolina. However, several hours later, Dorian

encountered high wind shear, causing the storm to weaken to a Category 2 hurricane, and later to

Category 1 intensity early on 6 September. At 12:35 UTC, Dorian made landfall in Cape Hatteras,

North Carolina as a Category 1 hurricane. Afterward, Dorian began to transition into an extratropical

cyclone as it quickly moved north-eastward, completing its transition on September 7. The storm

3 The Bermuda High pressure system sits over the Atlantic spring and summer. Acting as a block that hurricanes

cannot penetrate, the size and location of this system can determine where hurricanes go. A normal Bermuda

High often leads to hurricanes moving up the east cost of the US and out to sea (NASA, 2006).

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

26

subsequently strengthened, due to baroclinic processes, generating Category 2 hurricane winds.

Several hours later, Dorian made landfall on Sambro Creek, Nova Scotia, as a Category 2-equivalent

extratropical storm, before making another landfall on the northern part of Newfoundland several

hours later. On 8 September, Dorian had moved into Labrador Sea, maintaining tropical storm

strength winds. On 10 September, Dorian´s extratropical remnant dissipated off the coast of

southern Greenland.

FIGURE 1. PATH OF HURRICANE DORIAN ACROSS THE ATLANTIC

Source: Assessment team, 2019, using data provided by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

assessment of the effects

27

FIGURE 2. PATH OF HURRICANE DORIAN IN THE NORTHERN CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN ATLANTIC

Source: Assessment team, 2019, using data provided by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

hurricane dorian in the bahamas

The effects of Hurricane Dorian in The Bahamas were among the worst experienced for any

disaster in the country. Hurricane Dorian hit Abaco as a Category 5 hurricane on 1 September, and

a day later hit Grand Bahama at the same category. The hurricane then stalled over Grand Bahama

for another day, finally moving away from the island on 3 September.

On 31 August, as Hurricane Dorian intensified while approaching The Bahamas, voluntary

evacuations were issued on Abaco and Grand Bahama. In low-laying cays, government officials

urged residents to move inland. Boats rented by the government shuttled residents of outlying

fishing communities to McLean´s Town on Grand Bahama. Most major resorts were forced to

close. Nine hurricane shelters were opened on Grand Bahama and fifteen shelters were opened

on Abaco. Airports on Abaco, Grand Bahama and Bimini were closed by 1 September. Government

workers were ordered to stay indoors once winds outside reached tropical storm force.

On 1 September the Bahamas Department of Meteorology published Alert #27, detailing the track

of the storm and the potential threat to the Bahamas and it said:

“…Extremely dangerous Hurricane Dorian is closing in on Abaco and Grand Bahama…

A hurricane warning remains in effect for portions of the northwest Bahamas which

includes: North Eleuthera, Abaco, Grand Bahama, Bimini, The Berry Islands and New

Providence.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

28

A hurricane warning means that hurricane conditions could affect the mentioned

islands within 36 hours a hurricane watch remains in effect for North Andros.

A hurricane watch means that hurricane conditions could affect the mentioned island

within 48 hours.

At 2 AM EDT, the center of Hurricane Dorian was located near Latitude 26.3 degrees

north and longitude 75.6 degrees west, about 85 miles northeast of Governor´s

Harbour, Eleuthera; 95 miles east of Marsh Harbour, Abaco; 135 miles northeast of

New Providence; and 147 miles southeast of East End, Grand Bahama.

Hurricane Dorian is moving toward the west at near 8 mph and a slower westward

motion is forecast for the next day or two, followed by a gradual turn toward the

northwest. On this track, the core of Dorian should be near or over Abaco and Grand

Bahama today.

Maximum sustained winds remain near 150 miles per hour with higher gusts. Dorian

is a strong Category 4 Hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane wind scale. Some

fluctuations in the intensity are likely, but Dorian is expected to remain a powerful

hurricane during the next few days.

Hurricane force winds extend outward up to 30 miles from the center and tropical

storm force winds extended outward up to 105 miles from the center.

Currently, the feeder bands of hurricane Dorian producing showers over the islands of

Eleuthera, Cat Island Abaco, and should hurricane Dorian remain on the latest forecast

track through tonight, resident on Abaco will begin to experience tropical storm force

winds momentarily and hurricane force winds later this morning.

Meanwhile, residents in East Grand Bahama could begin to experience tropical storm

force winds at about 9 am and hurricane force winds at about 7 pm. Tropical storm

force winds are forecast to begin in West End, Grand Bahama at about 8 pm and

increase in strength through tonight. Tropical storm force winds are to be experienced

in New Providence around 9 am this morning. The eye of Dorian is forecast to pass

over Treasure Cay, Abaco at about later this morning or early this afternoon. Residents

in these areas should not be deceived by the lull in the winds as the eye passes but

remain indoors and prepare for the second phase of the hurricane.

Since Dorian is expected to slow down as it nears the northwest Bahamas, a prolonged

period of Life-Threatening storm surge accompanied by large and destructive waves

up to 15 feet above normal tide can be expected along the eastern and northern

shores of Eleuthera and Abaco today and the northern and southern of Grand Bahama

tonight through Tuesday.

Dorian is expected to produce rainfall amounts of 10 to 15 inches ever portions of

Abaco and Grand Bahama and 2 to 4 inches over the reminder of the northwest

Bahamas and the central Bahamas…”

On 1 September, the eye of Hurricane Dorian made landfall on the Abaco Islands with maximum

sustained winds of 185 mph (280 km/h), making it the strongest hurricane on record to affect The

Bahamas. The next day, the eye of Dorian moved over the eastern side of Grand Bahama and drifted

across the island. According to technical staff from different institutions and people interviewed

assessment of the effects

29

during the field visits, storm surge provoked storm tide of 20 to 25 ft (6.1 to 7.6 m). Dorian also

dropped an estimated 3 ft (0.91 m) of rain over the Bahamas.

Based on these descriptions, assessment reports from different government institutions responsible

for civil protection, emergency management entities, and the field assessment conducted by the

Assessment team between 30 September and 4 October, it has been concluded that the most

affected islands were Abaco and its cays and Grand Bahama. The main effects from Hurricane

Dorian to these islands are described below.

FIGURE 3. PATH OF HURRICANE DORIAN THROUGH ABACO ISLANDS AND GRAND BAHAMA

Source: Assessment team, 2019, using data provided by the United States National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

abaco islands

On September 1, Hurricane Dorian hit the island of Abaco as a Category 5. According to the

trajectory of the hurricane, the central and northern part of island were under the influence of

hurricane force winds. All these areas were severely affected not only by winds but also by storm

surge and flooding. The districts and towns affected were:

– In the northern part of South Abaco: Crossing Rocks.

– Central Abaco: Cherokee Sound, Ocean Point, Treasure Cay, Dundas Town, Little

Harbour, Marsh Harbour, Murphy Town, Sand Banks (Shanty Town), The Farm (Shanty

Town), Spring City, The Mudd (Shanty Town), The Pea (Shanty Town), Behring Point,

Bowen Sound, Cargill Creek, Man of War Sound.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

30

– North Abaco: Blackwood, Cedar Harbour, Cooper´s Town, Crown Haven, Fire Road,

Fox Town, Mount Hope, Wood Cay.

– Cays: Bridges Cay, Lynyard Cay, Sandy Cay, Channel Cay, Tilloo Cay, Lubbers Quarters

Cay, Elbow Cay, Sugar Loaf Cay, Man-O-War Cay, Scotland Cay, Great Guana Cay,

Treasure Cay, Pelican Cay, Green Turtle Cay, Crab Cay, Nunjack Cay, Ambergris Cay,

Powel Cay, Spanish Cay, Alians-Pensacola Cay.

FIGURE 4. AFFECTED AREAS ON ABACO ISLANDS BY WINDS AND FOOD

Source: Assessment team, 2019, using data provided by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

and Bahamas National Geographic Information System Centre

Marsh Harbour was severely affected by Dorian, most of the infrastructure was damaged and

observable comparing the satellite images before and after the event below.

assessment of the effects

31

FIGURE 5. AFFECTED AREAS MARSH HARBOUR

a- Digital Globe Image: July 13, 2019

b- Airbus Image: September 4, 2019

Source: Google Earth a) Maxar Technologies, 2019; b) Airbus, 2019

Informal communities in the area were mostly destroyed due to the type of vulnerable housing

infrastructure. One of the most affected sites was the area named “the Mudd”, which was a

community located in the eastern site of Marsh Harbour, mostly inhabited by Haitian migrants.

Figure 6 shows satellite images before and after the event.

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

32

FIGURE 6. AFFECTED AREAS THE MUDD – MARSH HARBOUR

a- Digital Globe Image: October 24, 2018

Source: Google Earth a) Maxar Technologies, 2018; b) Airbus, 2019

In North Abaco another vulnerable community located in the western side of Treasure Cay, named

Sand Banks, was also destroyed.

b- Airbus Image: September 4, 2019

assessment of the effects

33

FIGURE 7. AFFECTED AREAS SAND BANKS – NORTH ABACO

a- Digital Globe Image: January 28, 2019 b- Airbus Image: September 4, 2019

Source: Google Earth a) Maxar Technologies, 2019; b) Airbus, 2019

Hurricane Dorian impacted the cays along the eastern side of Abaco, the images below present

some examples of the areas that were severely affected by the hurricane.

FIGURE 8. AFFECTED AREAS CAYS ALONG EASTERN ABACO

Man–O–War Cay

Digital Globe Image: July 13, 2019 Airbus Image: September 4, 2019

Source: Google Earth a) Maxar Technologies, 2019; b) Airbus, 2019

hurricane dorian - the bahamas

34

FIGURE 9. AFFECTED AREAS GREAT GUANA CAY

Airbus Image: July 13, 2019

Airbus Image: September 4, 2019

Source: Google Earth a) Maxar Technologies, 2019; b) Airbus, 2019

grand bahama

On 2 September, the eye of Dorian moved over the eastern site of Grand Bahama and drifted

across the island as a Category 5. The hurricane then stalled over Grand Bahama for another day,

finally pulling away from the island on 3 September.

According to the descriptions of the Department of Meteorologist staff interviewed during the

field mission, storm surge and flooding were the events provoked by Hurricane Dorian that caused

considerable damages, especially on the eastern side of the island. They described that the flooding

on Grand Bahama began from the north and northeast and moved toward the south of the island,

this phenomenon was due to the trajectory of the hurricane and the period that Dorian remained

in the northern part of The Bahamas in the open ocean.

In Freeport the most affected areas were located on the north side of the city. Additionally, based

assessment of the effects

35

on available geo-information, flooding areas could be identified in the northwestern side of the

island around the airport. It is important to mention that according to the analysis done by the staff