The State Bar of

California’s Attorney

Discipline Process

Weak Policies Limit Its Ability to Protect the

Public From Attorney Misconduct

April 2022

REPORT 2022-030

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact our Public Affairs Office at 916.445.0255

This report is also available online at www.auditor.ca.gov | Alternative format reports available upon request | Permission is granted to reproduce reports

Capitol Mall, Suite | Sacramento | CA |

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

.. | TTY ..

...

For complaints of state employee misconduct,

contact us through the Whistleblower Hotline:

Don’t want to miss any of our reports? Subscribe to our email list at

auditor.ca.gov

Michael S. Tilden Acting State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200 | Sacramento, CA 95814 | 916.445.0255 | 916.327.0019 fax | www.auditor.ca.gov

April 14, 2022

2022‑030

e Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

e StateBar of California (StateBar) is responsible for protecting the public from attorneys who fail

to fulfill their professional duties, and it works to meet this obligation by administering a disciplinary

system that investigates and prosecutes complaints. However, our audit of the StateBar found that it

failed to effectively deter or prevent some attorneys from repeatedly violating professional standards.

We found that the StateBar prematurely closed some cases that warranted further investigation and

potential discipline. We reviewed files for one attorney who was the subject of 165 complaints over

seven years, many of which the StateBar dismissed outright or closed after sending private letters to the

attorney. Although the volume of complaints against the attorney has increased over time, the StateBar

has imposed no discipline, and the attorney maintains an active license. e StateBar dismisses about

10 percent of all complaints using nonpublic measures such as private letters, which did not deter some

attorneys we reviewed from continuing to engage in similar misconduct.

e StateBar failed to adequately investigate some attorneys, despite lengthy patterns of complaints

against them. In one example, it closed multiple complaints alleging that an attorney failed to pay clients

their settlement funds. When the StateBar finally examined the attorney’s bank records, it found that

the attorney had misappropriated nearly $41,000 from several clients. In another example, the StateBar

closed 87 complaints spanning 20 years before it sought disbarment of an attorney due to a federal

conviction for money laundering. Had the StateBar taken the pattern of complaints into account when

deciding whether to request additional evidence, it might have discovered the misconduct sooner and

mitigated harm to clients.

Finally, the State Bar has not consistently identified or addressed the conflicts of interest that exist

between its own staff members and the attorneys they investigate. In more than one-third of the cases

we reviewed, the StateBar did not document its consideration of conflicts before it closed these cases.

To remedy these weaknesses, the StateBar needs to make significant improvements to the safeguards

that help ensure its staff conduct thorough investigations, and the Legislature should take additional

steps to ensure the StateBar’s compliance with its revised policies and procedures.

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL S. TILDEN, CPA

Acting California State Auditor

iv California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

vCalifornia State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Contents

Summary 1

Recommendations 5

Introduction 9

Audit Results

Weaknesses in the StateBar’s Attorney Discipline System Have Resulted

in Some Attorneys Not Being Held Accountable for Misconduct 13

The StateBar Failed to Accurately Track or Document Its Consideration

of Some Staff Members’ Potential Conflicts of Interest 26

The StateBar’s Weak Safeguards Have Hampered Its Ability to Prevent

Repeated Client Trust Account Violations 27

Weaknesses in the StateBar’s Monitoring of Its Attorney Discipline

System Limit the Independence of That Monitoring 36

Appendix A

Demographic Data Pertaining to Complaints Against Attorneys 43

Appendix B

Scope and Methodology 51

Response to the Audit

The StateBar of California 53

California State Auditor’s Comments on the Response From

the StateBar of California 65

vi California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

1California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Summary

Results in Brief

Attorneys hold significant responsibility as representatives and

advisers of their clients. Clients often seek an attorney during

times of crisis when they are in a particularly vulnerable situation.

To protect the public from attorneys who fail to fulfill their

professional responsibilities competently, the StateBar of California

(StateBar) administers a disciplinary system that investigates and

prosecutes complaints of professional misconduct against the more

than 250,000 lawyers licensed in California. After investigating

complaints, it may bring a case to the StateBar Court of California

seeking discipline against an attorney. A case may be closed for

reasons such as insufficient evidence; it may be resolved through a

nondisciplinary measure, such as a warning letter; or it may result

in discipline. To ensure that complaints of attorney misconduct

are reviewed consistently, the StateBar establishes policies and

processes for its staff to follow.

e StateBar closes many cases without notice to the public

through certain methods, such as warning letters—which we

describe as nonpublic measures—but it lacks clear policies on

when staff should use these nonpublic measures. Cases that

are confidential and not made public may not deter attorney

misconduct because current and potential clients cannot find out

about the behavior. Similarly, the StateBar lacks clear policies on

what its staff should do when a complainant withdraws from a case,

which can result in cases being closed without determining whether

misconduct occurred. For example, we identified an attorney for

whom the StateBar closed four cases when the clients withdrew

their complaints. ese cases demonstrated that the StateBar knew

that multiple clients had similar complaints about the attorney not

promptly distributing funds to which the clients were entitled. Had

the StateBar investigated these cases, it might have found sufficient

grounds for discipline and thus might have prevented further harm

to the attorney’s clients.

e StateBar does not proactively seek out information regarding

disciplinary actions against attorneys in other jurisdictions; instead

it relies on the attorneys themselves or the other jurisdictions to

report the discipline to the StateBar. However, we found several

examples of discipline imposed by other jurisdictions that were not

communicated to the StateBar for one year or more. e American

Bar Association maintains a National Lawyer Regulatory Data Bank

(data bank) of discipline imposed in other jurisdictions, but the

StateBar has not used it on any regular basis to proactively identify

California-licensed attorneys disciplined in other jurisdictions,

thereby increasing the risk that attorneys who have committed

Audit Highlights . . .

Our audit of the State Bar’s attorney discipline

process found that it failed to effectively

prevent attorneys from repeatedly violating

professional standards.

» The State Bar prematurely closed some

cases that may have warranted further

investigation and potential discipline.

» It lacks clear policies on the use of nonpublic

measures for closing complaints.

• It dismissed many investigations by

nonpublic measures, such as private

warning letters to attorneys.

» It did not adequately investigate some

attorneys with lengthy patterns of complaints.

• It closed multiple complaints alleging

that an attorney failed to pay clients

their settlement funds because the

clients withdrew their complaints,

which allowed the attorney to continue

misappropriating client funds.

» It has not consistently identified or

addressed the conflicts of interest that may

exist between its own staff members and

the attorneys they investigate.

• In more than one-third of the cases we

reviewed, the State Bar did not document

its consideration of conflicts before it

closed complaint cases.

» These issues are illustrated in the State Bar’s

handling of client trust account violations,

in which it repeatedly used nonpublic

measures to close complaints.

2 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

misconduct in other jurisdictions will continue to practice in

California. Further, the StateBar’s ability to analyze patterns of

similar complaints is hampered because its case management

system has 672 types of allegations but does not group these

complaints into similar categories. Without more general categories

of allegations, it can be difficult for StateBar staff to identify

patterns of complaints alleging similar behavior.

Additionally, the StateBar requires its employees to complete an

annual questionnaire in which they disclose personal, financial,

and professional relationships they have with licensed California

attorneys. However, in 11 of 30 cases we reviewed, the StateBar did

not document its consideration of conflicts of interest. It is critical

that the StateBar objectively assess and document its consideration

of conflicts of interest when closing a case, particularly at the

intake stage. e chief trial counsel agreed with our findings and

indicated that management of conflicts of interest is an area where

the StateBar needs much improvement. He further noted that

conflict-of-interest information has not been consistently updated

in its current case management system, and he is working with his

staff to correct the issue.

e issues we identified are illustrated in the StateBar’s handling

of many complaints related to client trust accounts. ese

accounts hold funds paid to attorneys on behalf of a client, such

as an advance fee for future services or funds received as the

result of a settlement. Our review identified that the StateBar

closed many client trust account complaints using nonpublic

measures, sometimes without even notifying the attorney about

the complaint, and that an attorney’s prior history of allegations did

not appear to affect the StateBar’s decision to close certain client

trust account cases. For example, for one attorney we reviewed, the

StateBar closed 87 complaints spanning 20 years, some through

nonpublic measures and some through a policy that allowed it to

close certain cases without contacting the attorney for additional

information because the monetary amounts involved were relatively

low (a deminimis closing). However, the StateBar eventually

sought disbarment based on this attorney’s conviction in federal

court for money laundering through client trust accounts.

Finally, weaknesses in the StateBar’s monitoring processes diminish

the value of those processes in ensuring that it is closing attorney

discipline cases appropriately. It closes the majority of cases without

discipline. Although it allows complainants to appeal its decisions

to close complaints, relatively few complainants do so. us, it

appears that individuals may need additional assistance in filing

complaints and appeals. One option for assisting complainants with

these actions would be to establish an independent ombudsperson

for attorney discipline. Moreover, the StateBar uses an external

3California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

reviewer to conduct a semiannual review of a selection of its closed

cases to identify errors and areas for staff improvement. However,

several flaws in the design of the external review process limit its

independence, such as not alternating among different reviewers;

having the reviewer submit its report to StateBar management

instead of directly to the Board of Trustees of the StateBar; and not

having the external reviewer select cases for review. All of these

factors increase the risk that the review is notobjective.

Agency Comments

e StateBar generally agreed with our findings and

recommendations, with one exception. However, it asserted

that it would need significant additional resources to implement

therecommendations.

4 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

5California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Recommendations

e following are the recommendations we made as a result of our

audit. Descriptions of the findings and conclusions that led to these

recommendations can be found in the Audit Results section of

thisreport.

Legislature

To improve the independence and objectivity of the semiannual

review of the State Bar of California (StateBar) case files, the

Legislature should require the StateBar to do the following:

• Regularly change its external reviewer.

• Have its external reviewer present its findings and

recommendations, with all confidential information redacted,

directly to the Board of Trustees of the State Bar (board).

• Require the StateBar to report periodically to the

board on the actions it takes to address the external

reviewer’srecommendations.

To ensure that the StateBar implements the policy and procedure

changes identified in this audit, the Legislature should require

an assessment by no later than December 2023 of the StateBar’s

compliance with those policies and procedures.

StateBar

To ensure that it uses nonpublic measures to close complaints only

when such use is consistent and appropriate, the StateBar should

revise its policies by October 2022 to define specific criteria that

describe which cases are eligible to be closed using nonpublic

measures and which are not eligible.

To ensure that it fulfills its duties to investigate attorney

misconduct, by April 2023, the StateBar should begin monitoring

compliance with its new policy for identifying the circumstances

in which investigators should continue to investigate even if the

complainant withdraws the complaint.

e StateBar should notify the public on its website when other

jurisdictions have determined that an attorney who is also licensed

in California presents a substantial threat of harm to the public.

6 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

To ensure that it identifies discipline imposed on California

attorneys in other jurisdictions, the StateBar should use the

American Bar Association’s data bank to identify attorneys

disciplined in other jurisdictions who have not reported that

discipline to the StateBar.

To allow its staff to more easily identify patterns of similar

complaints made against attorneys, by July 2022, the StateBar

should begin using its general complaint type categorizations when

determining whether to investigate a complaint.

To improve its ability to identify and prevent conflicts of interest

that its staff may have with attorneys who are subjects of

complaints, the StateBar should develop a process by July 2022 for

monitoring the accuracy of the information in its case management

system used to flag attorneys with whom its staff have declared a

conflict of interest.

To ensure that StateBar staff do not inappropriately close cases

against attorneys on the conflict list, the StateBar should create

a formal process by October 2022 for determining whether it is

able to objectively assess whether such a complaint should be

closed or whether the decision should be made by an independent

administrator. e StateBar should document this assessment in its

case files for each case against an attorney on the conflict list.

To increase the independence and objectivity of the external review

of its case files, the StateBar should amend its policies by July 2022

to do the following:

• Require its external reviewer to select the cases for the

semiannual review.

• Establish formal oversight to ensure that it follows up and

addresses the external reviewer’s findings.

To ensure that it appropriately reviews complaints involving

overdrafts and alleged misappropriations from client trust accounts,

the StateBar should perform the following by July 2022:

• Discontinue its use of informal guidance for review of bank

reportable actions and direct all staff to follow the policies

established in its intake procedures manual (intake manual).

• Revise its intake manual to disallow deminimis closures if the

attorney has a pending or prior bank reportable action or case

alleging a client trust account violation.

7California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

• Establish a monitoring system to ensure staff are following its

policies for deminimis closures.

• When investigating client trust account-related cases and

bank reportable actions not closed deminimis, require its

staff to obtain both the bank statements and the attorney’s

contemporaneous reconciliations of the client trust account, and

determine if the relevant transactions are appropriate.

• Require a letter with client trust account resources be sent to the

attorney after the closure of every bank reportable action.

8 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

9California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Introduction

Background

e California Constitution establishes three branches of state

government: the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

e judicial branch is responsible for interpreting the laws of

the State and, among other functions, providing access to the

courts for individuals to defend their personal and property

rights, determining the guilt or innocence of those accused

of violating laws, and protecting the rights of individuals. e

Supreme Court of California (Supreme Court) holds the power

to admit, disbar, and suspend attorneys who are considered

officers of the court. Attorneys hold significant responsibility as

representatives of and advisers to their clients. Clients often seek

the services of an attorney during times of crisis when they are in

a particularly vulnerable situation. To fulfill their role, attorneys

are accorded a great degree of trust, as well as certain privileges

and responsibilities: they may legally represent their clients,

may hold funds on behalf of their clients, and must maintain the

confidentiality of the information that their clients provide them.

Every person who is admitted and licensed to practice law in

California must be a member of the StateBar of California

(StateBar), except for judges currently serving in that capacity. e

StateBar is a public corporation within the judicial branch. As the

text box shows, state law establishes public protection as the

highest priority of the StateBar. e StateBar

provides this protection by, among other activities,

licensing attorneys, regulating the profession and

practice of law, enforcing its Rules of Professional

Conduct for attorneys, and disciplining attorneys

who violate rules and laws. To prevent attorney

misconduct, the StateBar encourages ethical

behavior through resources such as education

programs and a hotline for attorneys seeking

guidance on their professionalresponsibilities.

e StateBar is governed by the 13-member

Board of Trustees of the StateBar (board), seven

of whom are attorneys appointed by the Supreme

Court or the Legislature. e remaining six are

members of the public who are not attorneys

and who are appointed by the Legislature or the

Governor. e board adopts a strategic plan with

goals for meeting the StateBar’s responsibilities,

such as ensuring timely, fair, and appropriately

resourced admission, discipline, and regulatory

systems for the more than 250,000 lawyers

The StateBar’s

Core Mission and Selected Responsibilities

Core Mission

State law establishes that “Protection of the public... shall

be the highest priority for the StateBar of California and the

board of trustees in exercising their licensing, regulatory,

and disciplinary functions. Whenever the protection of

the public is inconsistent with other interests sought to be

promoted, the protection of the public shall be paramount.”

Selected Functions

• License attorneys in California.

• Enforce the Rules of Professional Conduct for attorneys.

• Discipline attorneys who violate rules and laws.

• Administer the California bar exam.

Source: State law and the StateBar’s website.

[Insert Text Box]

10 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

licensed in California. e board also establishes

committees composed of its own members,

including a regulation and discipline committee

that oversees the StateBar’s management of the

attorney discipline process.

Attorney Discipline

To protect the public from attorneys who fail

to fulfill their professional responsibilities

competently, the StateBar administers a discipline

system through which it receives, investigates,

and prosecutes claims of attorney misconduct.

e StateBar receives complaints from the

public by mail or through an online submission

form. In addition, it can initiate inquiries or

investigation into attorney conduct based on

information it receives from third-party sources.

For example, the StateBar may open cases based

on sources it terms reportable actions, such as a

notification from a bank that an attorney’s client

trust account has insufficient funds. e text box

identifies some major categories of professional

misconductallegations.

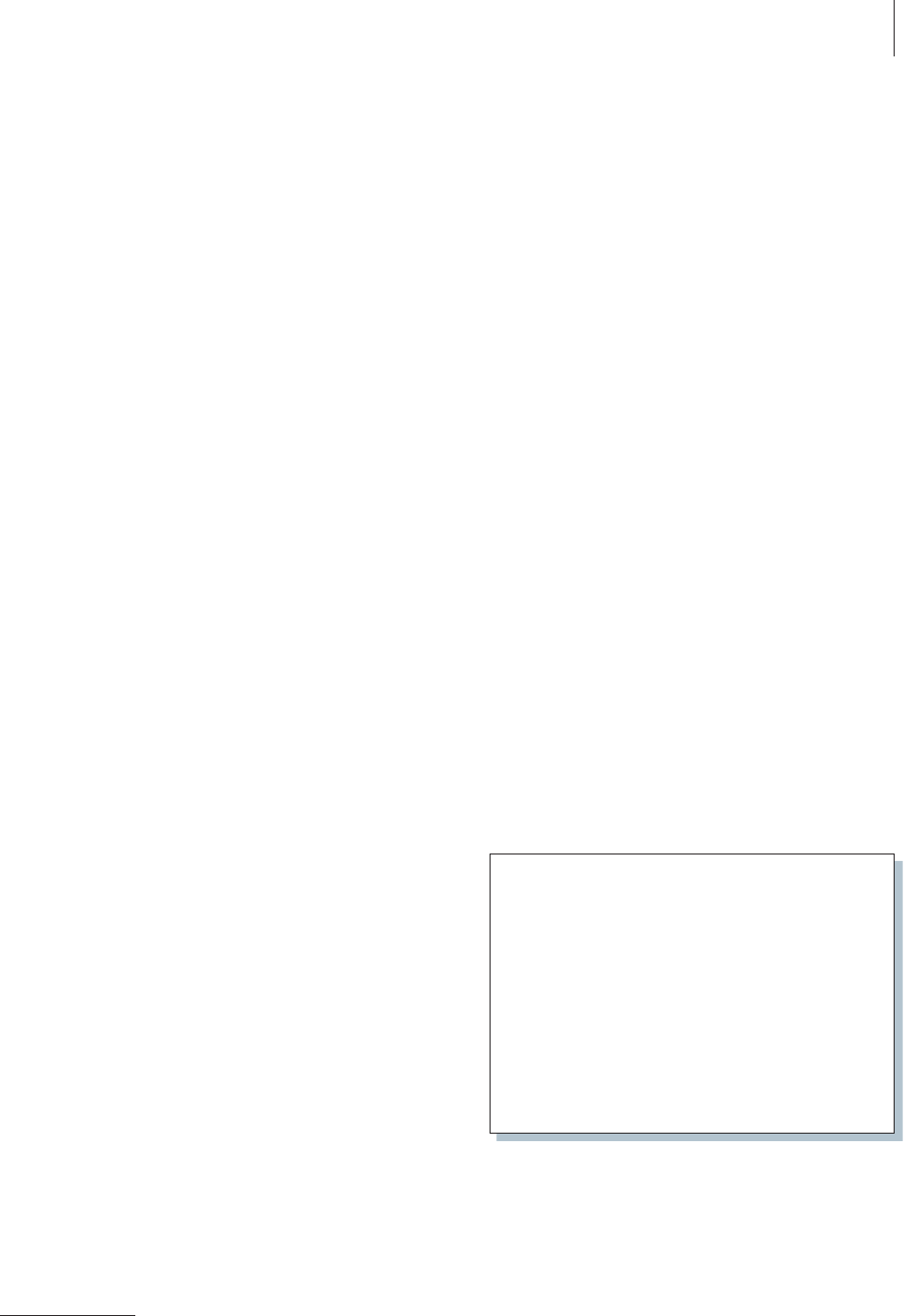

Two of the primary components of the StateBar’s attorney

discipline system are the Office of Chief Trial Counsel of the

StateBar (trial counsel’s office) and the StateBar Court of California

(StateBar Court). For 2021 the StateBar adopted a budget of nearly

$75million for these divisions. As Figure1 indicates, the StateBar’s

process for reviewing complaints of alleged attorney misconduct

includes multiple levels of reviews, and it closes many complaints

at the intake level. At the intake level, the trial counsel’s office

conducts a review to determine whether misconduct alleged in a

complaint warrants an investigation. When the StateBar closes a

complaint at the intake level, it informs the individual who made

the complaint of the decision in writing and describes how to

request an appeal of the decision or provide additional facts. From

January 2010 to November 2021, more than one-third of complaints

received were investigated, and slightly more than 5percent of cases

resulted in formal discipline of the attorney.

For those complaints that it does not close at the intake phase, the

trial counsel’s office investigates and, where appropriate, prosecutes

attorneys for violations of the StateBar Act or the StateBar’s Rules

of Professional Conduct, which establish professional and ethical

standards for attorneys to follow. e StateBar Court adjudicates

the matters that the trial counsel’s office files and may privately

[Insert Text Box]

[Insert Figure 1]

Examples of Allegations of

ProfessionalMisconduct

The StateBar receives allegations of attorney misconduct,

including the following general types:

Failure to perform competently: When an attorney does

not perform agreed-upon services, such as appearing in

court or drafting a document for the client.

Untimely communication: When an attorney does not

promptly inform a client of decisions or circumstances that

require informed consent or disclosure according to the

StateBar Act or the Rules of Professional Conduct.

Commingling of funds: When an attorney holds certain

funds received for the benefit of a client in an account that

holds the attorney’s own funds.

False advertising: When an attorney guarantees results

oroutcomes.

Source: State law, the StateBar’s Rules of Professional Conduct,

the StateBar’s intake procedures manual (intake manual), a state

court case, and the StateBar’s 2021 annual disciplinereport.

11California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

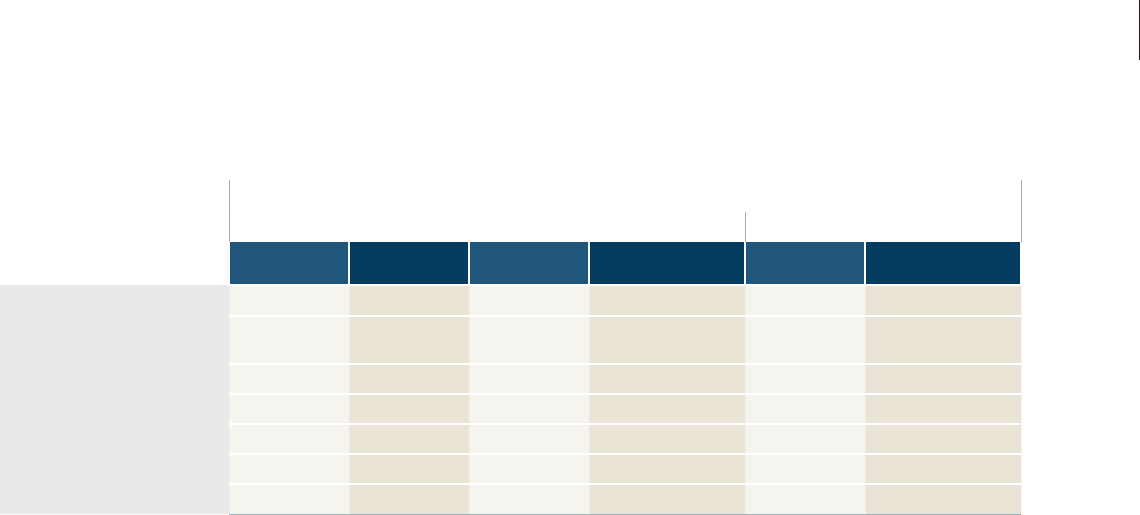

Figure1

The StateBar’s Attorney Discipline Process Includes Multiple Levels of Review

INTAKE

When the trial counsel’s office receives a complaint, it conducts a legal

review to determine whether the alleged misconduct constitutes a

disciplinable violation. In doing so, the trial counsel’s office may close the

complaint or forward it for investigation.

35.5%

INVESTIGATION

If forwarded, the trial counsel’s office conducts an investigation to

determine whether there is sufficient evidence to support the allegation of

attorney misconduct. If so, the complaint advances to prefiling. The trial

counsel’s office may, at its discretion, close a case at this stage without

imposing discipline, such as by issuing a warning letter.

13.3%

PREFILING

The trial counsel’s office drafts disciplinary charges for cases that it has

determined have sufficient evidence for prosecution in the State Bar Court.

Either party may request an early conference before a judge to discuss a

potential settlement.

7.1%

HEARING AND DISCIPLINE

• The State Bar Court conducts evidentiary hearings and then renders a

decision with findings and recommendations of discipline or closes the

case without discipline. The State Bar Court’s authority to discipline

attorneys includes issuing reprovals, which can be public or private.

• In cases that warrant the imposition of suspension or disbarment, the

State Bar Court recommends the appropriate disciplinary actions to the

Supreme Court for review.

64.5%

22.2%

6.2%

1.8%

of cases

went to

of cases

went to

of cases

went to

of cases were

closed with

of cases

were closed

during INTAKE.

during PREFILING.

during INVESTIGATION.

during HEARING and DISCIPLINE

without discipline.

of cases

were closed

of cases

were closed

of cases

were closed

of cases were closed with REPROVALS or

RESIGNATION WITH CHARGES PENDING

0.5%

STATE BAR COURT

5.3%

FORMAL DISCIPLINE

of cases were closed

with SUSPENSIONS and DISBARMENTS

4.8%

SUPREME COURT

Source: Analysis of the StateBar’s case data, state law, the Rules of Professional Conduct, the Rules of Procedure of the StateBar, the StateBar’s intake

manual, and the StateBar’s 2021 annual discipline report.

Note: Percentages in this figure are derived from the more than 221,000 cases that the StateBar closed between January 1, 2010, and November10,2021,

which include cases opened in previousyears.

12 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

or publicly reprove an attorney or, if warranted,

may recommend that the Supreme Court—which

makes the final decision for such discipline—

suspend or disbar the attorney in question. e

text box identifies some of the possible outcomes

of the StateBar’s disciplinary cases.

According to the clerk of the StateBar Court, in

some instances, the StateBar Court chooses to

place an attorney on probation for all or part of

the time he or she would otherwise be suspended.

e goals of attorney probation include protection

of the public and rehabilitation of the attorney.

Probation may include a variety of conditions,

such as financial restitution or StateBar ethics

school. e StateBar’s Office of Probation

supervises attorneys placed on probation, and

when an attorney does not comply with the terms

of probation, the StateBar has established three

potential outcomes: close the matter without

further action; revoke the probation, which may

result in the attorney’s suspension; or prosecute

the noncompliance as a new offense, which may

result in the imposition of new discipline.

e Legislature passed a law, which became

effective on January 1, 2022, requiring the

California State Auditor’s Office to conduct an

audit of the StateBar’s attorney complaint and

discipline process. e Legislature included this

requirement in the law because the StateBar did not take action

against one attorney for misconduct until recently, despite repeated

allegations of this attorney’s misconduct overdecades.

[Insert Text Box]

Examples of Potential Outcomes of the

StateBar’s Disciplinary Cases

Disbarment: A public disciplinary sanction whereby the

Supreme Court orders the attorney’s name to be stricken

from the roll of California attorneys; during this time, the

attorney is precluded from practicing law in the State.

Suspension: A public disciplinary sanction that generally

prohibits a licensee from practicing law or from presenting

himself or herself as entitled to practice law for a period

of time ordered by the Supreme Court. A suspension can

include a period of actual suspension, stayed suspension,

or both.

Reproval: The lowest level of court-imposed discipline,

wherein the StateBar Court censures or reprimands

the offending attorney for misconduct. Reprovals may

include conditions such as making restitution, completing

probation, or completing education on subjects such as

ethics or the law. Reprovals can be public or private.

Dismissal: The disposal or closure of a disciplinary matter,

for reasons such as insufficient evidence. The StateBar may

close cases using methods that do not provide notice to the

public, such as a warning letter. Such methods are known as

nonpublic measures.

Source: State law, Rules of Procedure of the StateBar, the

StateBar’s investigation manual, and the StateBar’s training

material on determining the level of discipline.

13California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Audit Results

Weaknesses in the StateBar’s Attorney Discipline System Have Resulted

in Some Attorneys Not Being Held Accountable forMisconduct

To assess the StateBar’s attorney discipline system, we focused on

key aspects of that process and determined whether the StateBar

had established safeguards that are sufficient to ensure that it

identifies attorney misconduct and imposes appropriate discipline.

To ensure that its reviews of complaints of attorney misconduct are

consistent, the StateBar must establish policies and processes for

its staff to follow. However, we found that the StateBar’s policies

on how it should use certain methods to close cases without public

notice—known as nonpublic measures—lack clarity and that it

overused these methods. Until recently, the StateBar’s policies

did not identify the factors staff should consider when deciding

whether to close cases in which an attorney has likely committed

misconduct but the complainant withdraws the complaint. In

addition, although the StateBar established policies for addressing

misconduct by California attorneys in other jurisdictions and for

addressing patterns of complaints against attorneys, its failure to

develop and use tools that would help it identify these issues has led

to inconsistencies and missed opportunities to inform and protect

the public.

The StateBar Prematurely Closed Some Cases That Should Have

Warranted Further Investigation and Potential Discipline

e StateBar’s official policy describes three primary purposes of

attorney discipline: protection of the public, the courts, and the

legal profession through deterrence; maintenance of the highest

professional standards; and preservation of public confidence in

the legal profession. However, some of the StateBar’s policies

lack clarity, which has resulted in its staff closing cases when

further investigation would likely have better protected the public.

Specifically, the StateBar closes many cases through nonpublic

measures, such as warning letters, but it lacks clear policies on

when it is appropriate for staff to use these nonpublic measures.

Complaints that are closed through nonpublic measures are

confidential and may have less of a deterrent effect on attorney

misconduct because current and potential clients cannot find out

about the behavior. Similarly, the StateBar has lacked clear policies

on whether its staff should proceed with cases when a complainant

withdraws the complaint, and it closed several such cases we

reviewed without determining whether misconduct had occurred.

14 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Although the StateBar’s policies provide general guidelines for

deciding when to use nonpublic measures, the policies lack the

details necessary to ensure that they are implemented consistently.

e StateBar uses a number of types of nonpublic measures,

which Figure2 details. Its policy directs staff to pursue nonpublic

measures only when doing so will reasonably protect against future

misconduct. Nevertheless, the policy does not identify the factors

that staff should consider to determine whether future misconduct

is likely to occur. e policy also states that nonpublic measures

should be used for minor violations that did not cause significant

harm or for violations that would likely not result in the imposition

of discipline. However, the policy does not define minor violations

or levels of harm resulting from an attorney’s conduct. e chief

trial counsel stated that staff should use their experience, judgment,

training, and knowledge of applicable standards to implement the

policy, but we found that the StateBar’s use of these measures is not

achieving the intent of its policy regarding their use.

e StateBar’s data indicate that the use of nonpublic measures is

not providing reasonable protection against future misconduct, as

its policy requires. A StateBar study from July 2021 showed that a

significant number of attorneys were investigated for misconduct

within two years after being disciplined. It also showed that nearly

26percent of attorneys whose cases were closed with a warning

letter in 2019 had a new complaint about their professional conduct

investigated by the StateBar within two years of the original case

being closed. e StateBar’s executive director indicated that the

StateBar has taken steps to address repeated misconduct, including

issuing a new policy addressing alternatives to discipline and adding

information to the closing letters for reportable actions that it

sends to attorneys, but its efforts to reduce recidivism are centered

around a redesign of its probation process for attorneys convicted

of misconduct.

Notwithstanding these steps, patterns of attorney misconduct

suggest that the StateBar is overusing nonpublic measures. From

2010 to 2021, the StateBar closed more cases through nonpublic

measures—a total of 22,600, or 10percent of all case closures—

than it did through public discipline, which totaled 11,200, or

5percent of all case closures. During the same period, more than

700 attorneys each had four or more cases that the StateBar closed

through nonpublic measures. Our review of a selection of cases

associated with five of these attorneys determined that StateBar

staff closed cases through nonpublic measures despite indications

in its case files that further investigation or actual discipline may

have been warranted. Of the five attorneys, four had at least

one previous complaint for similar misconduct that was closed

[Insert Figure 2]

The StateBar’s use of nonpublic

measures to close complaints is not

providing reasonable protection

against future misconduct, as its

policy requires.

15California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

Figure2

Nonpublic Measures That the StateBar Uses to Close Cases

Directs action on the part of an attorney. This

can include direction to return a client file or

to communicate with a client.

Informs an attorney of his or her ethical

obligations when there is substantial evidence

that he or she committed a violation that may

be misconduct.

A written agreement that may involve

conditions of practice or further legal

education or rehabilitation.

A censure or reprimand that may include

conditions. Private reproval is the only

nonpublic measure that the State Bar

considers to be discipline.

Describes resources, such as ethics training

or client trust account training, along with

a summary of the conduct of concern and

ways to rectify it.

RESOURCE LETTER

DIRECTIONAL LETTER

WARNING LETTER

AGREEMENT IN LIEU OF DISCIPLINE

PRIVATE REPROVAL

Source: The StateBar’s policy directives, website, and 2021 annual discipline report; Rules of

Procedure of the StateBar; the StateBar’s intake manual; StateBar discipline case files; and statelaw.

through nonpublic measures. In total, we reviewed 42 cases for

these five attorneys and found indications that the StateBar had

inappropriately closed 13 of them through nonpublic measures.

16 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

CaseExample1 demonstrates how, for one of these attorneys, the

complaints against the attorney increased over time even as the

StateBar closed multiple cases involving this attorney through

nonpublic measures. e StateBar’s legal adviser reviewing the

complaints against this individual asserted that the complaints

related more to the attorney’s poor office management than to

misconduct and stated that education and outreach might be more

appropriate than discipline for this attorney. However, the nature

of the complaints against the attorney call into question the legal

adviser’s assertions.

e cases involving this attorney that were closed using nonpublic

measures not only included failing to provide settlement payments

or to provide client files, but also included the attorney threatening

to report another attorney to the StateBar if the other attorney

did not provide requested information as well as offering to pay a

complainant to withdraw a complaint made to the StateBar. Further,

the StateBar’s use of nonpublic measures to address complaints

made against this attorney were ineffective as the number of

complaints against this attorney per year have increased. is

increase in cases may have resulted in further harm to the public as

well as representing an additional workload for the StateBar.

In cases where complainants no longer wish to pursue their

allegations, the StateBar’s policies previously gave it discretion

to continue the investigation but did not require that it do so,

regardless of whether it already possessed evidence of misconduct.

e Rules of Procedure of the StateBar allow it to investigate and

prosecute misconduct at its discretion, even if a complainant asks

to withdraw his or her complaint. e inconsistencies identified

as a result of this audit led the StateBar to issue a policy directive

in February 2022 clarifying how to proceed when a complainant

withdraws the complaint or otherwise fails to cooperate in the

investigation. Before this new policy, the StateBar’s policies did

not identify what factors should prevent it from closing a case

when a complainant considers a matter resolved or withdraws

the allegation, and we determined that the StateBar closed

some cases even when there was evidence of misconduct.

To examine the possible effects of this unclear guidance, we

reviewed 33closedcases for which the StateBar indicated that

the complainant no longer wished to pursue the complaint or the

attorney and complainant had resolved the issue. In seven of those

cases, there was evidence of misconduct by theattorney.

For example, for the attorney in CaseExample2, the StateBar

closed four cases from March 2019 through August 2019 after the

client in each case withdrew the complaint. A senior trial counsel

at the StateBar stated that, in practice, the StateBar closes cases

when the complainant withdraws the complaint, in part because

[Insert CaseExample1]

The inconsistencies identified

as a result of this audit led the

StateBar to issue a policy directive

in February clarifying how

to proceed when a complainant

withdraws the complaint or otherwise

fails to cooperate in the investigation.

17California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

CaseExample1

Case Example 1

Complaints

against

the attorney

Complaints

closed using a

nonpublic

measure

2006 2014Year 2021

1 42

1 1 1 1 1 1

2 2 2

6 6 7 8

3 3

4

6

9 10

20 20 21

19 18

31 26

Case Example 1

An attorney exhibited a pattern of

failing to provide settlement

payments or to provide files to

clients until the client complained.

The State Bar closed cases against

this attorney 28 times over 16 years

using nonpublic measures and all

of the other closed cases were

closed outright. However, complaints against the

attorney continued to increase. From 2014 to 2021, the

attorney was the subject of 165 complaints. Despite

the high number of complaints, many for similar

matters, the State Bar has imposed no discipline, and

the attorney still maintains an active license.

In one early case, the State Bar issued a warning letter

to the attorney for failing to release a client’s case file

for nearly a year. However, the attorney has continued

to generate complaints from other clients for this

same issue. In the 11 years since the State Bar issued

that warning letter, complaints have led the State Bar

to issue 11 directional letters requiring the attorney to

return client files.

Case Example 1

Note: We changed the demographics depicted in some of our case examples to protect the

confidentiality of these investigations.

the StateBar would need further evidence and testimony from the

complainant to be able to prosecute a case, and it does not have

an effective way of compelling cooperation from a complainant.

However, the complaints against the attorney described in

CaseExample2 demonstrate that closing a case because a

complainant no longer wishes to pursue the complaint may not

be in the public’s best interest. ese cases demonstrate that the

18 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

CaseExample2

Case Example 2

Case Example 1

The State Bar closed multiple

complaints that were made

against an attorney over the

course of about 18 months, each

alleging that the attorney had

failed to pay clients their

settlement funds. Generally, the

State Bar closed each complaint after the attorney

finally paid the client, noting either that the matter

was resolved between the attorney and the

complainant after the client withdrew their

complaint or that there was insufficient evidence to

support that the attorney’s conduct warranted

discipline. A pattern was discernible from five

complaints the State Bar received within one year

alleging that the attorney’s clients were not

receiving settlement payments. However, the State

Bar did not identify the need to examine the

attorney’s bank records until it had received more

than 10 complaints over two years. It did not

examine the records for another six months, during

which time the State Bar continued to receive

similar complaints.

When the State Bar finally examined the client trust

account, it found that the attorney had

misappropriated nearly $41,000 in total from

several clients. The State Bar ultimately filed

charges against the attorney stemming from these

more recent complaints. After the State Bar

questioned the attorney about discrepancies in the

client trust account, the attorney admitted to using

client funds for personal reasons.

Case Example 2

StateBar was informed that multiple clients had complained about

the attorney not promptly distributing funds the clients were

entitled to, which may be sufficient grounds for discipline. Had the

StateBar investigated these cases, it might have prevented further

harm to the attorney’sclients.

e StateBar’s practices and its staff’s responses to our inquiries

illustrated a common theme: the StateBar is generally focused on

closing cases expeditiously. is emphasis on closing cases quickly

appears to be in response to criticism the StateBar has faced for the

amount of time it has taken to close some cases.

[Insert CaseExample2]

19California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

e StateBar has long struggled to process all of the complaints

that it receives each year. Audits our office issued in April 2019 and

in April 2021 identified concerns about the backlog of unclosed

cases.

1

According to its executive director, addressing the complaint

backlog has been the most significant driving factor in the StateBar’s

development of performance measures and processes, in part

because of the focus of our office and the Legislature on the backlog.

Nevertheless, the patterns we observed suggest that staff following

some of the StateBar’s policies may be contributing to the large

number of complaints it must address. As Case Examples 1 and 2

illustrate, the StateBar’s actions have failed to prevent additional

misconduct of a similar nature, leading to an increase in the volume

of subsequent complaints about a specific attorney for the same

misconduct. In turn, this has increased the StateBar’s workload, which

makes it more difficult for it to address its backlog and fulfill its primary

mission of protecting the public.

Weak Processes Allow Attorneys Who Committed Misconduct in Other

Jurisdictions to Continue Practicing in California

Although state law clearly sets forth expectations regarding discipline

for attorneys who have committed misconduct in other jurisdictions,

the StateBar’s implementation of this law has not protected the public

in some instances and has led to significant delays in identifying

some cases of attorney discipline imposed on California attorneys

in other jurisdictions. Attorneys practicing law in other jurisdictions

may also be licensed by the StateBar to practice

law in California. e text box shows examples of

other jurisdictions. According to state law, a final

determination of professional misconduct in other

jurisdictions, such as a federal court or another state

court, is evidence that the attorney is culpable of

professional misconduct in California, with limited

exceptions. When another attorney disciplinary

authority, such as the state bar of another state,

disciplines an attorney who is also licensed to practice

in California, the StateBar’s policy is to determine

whether it should pursue imposing discipline on the

attorney based on the discipline imposed in the other

jurisdiction, a practice known as reciprocal discipline.

Imposing reciprocal discipline helps to protect the public and maintain

confidence in the legal profession by preventing attorneys who are

suspended or disbarred for misconduct in one jurisdiction from

practicing in California.

1

StateBar of California: It Should Balance Fee Increases With Other Actions to Raise Revenue and Decrease Costs,

Report -; and The StateBar of California: It Is Not Effectively Managing Its System for Investigating and

Disciplining Attorneys Who Abuse the Public Trust, Report -.

[Insert Text Box]

Examples of Other Jurisdictions

• Federal courts, including district courts and bankruptcycourts.

• Courts of other states.

• Regulatory agencies with authority to discipline attorneys,

such as the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Source: Federal law, StateBar intake manual, StateBar

guidelines for attorney mandatory reportable actions, the

U.S.Court’s website, and StateBar case files.

20 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

According to the assistant chief trial counsel who manages intake

staff (intake manager), the StateBar initiates cases related to

discipline in other jurisdictions in three instances: when attorneys

self-report the discipline as required by state law; when the

StateBar receives notifications from other jurisdictions; or when

the StateBar becomes aware of the discipline through other means,

such as media reports. However, as we discuss later, the StateBar’s

processes do not proactively identify discipline imposed by

otherjurisdictions.

From 2010 through 2021, the StateBar closed more than 700 cases

relating to attorney misconduct in other jurisdictions. We reviewed

32 of those cases and identified issues with nine of them, including

four for which the StateBar failed to impose public discipline even

though it was aware that another jurisdiction had done so, such as

in CaseExample3. In that case, before the attorney’s resignation in

California, the StateBar issued the attorney a warning letter instead

of taking other disciplinary action on the basis that it deemed the

attorney a minimal risk to the public due to their age and lack of

ties with California. e StateBar’s intake manager did not provide

any additional rationale for the StateBar’s decision to close the case.

However, the attorney’s age does not seem relevant, as the other

jurisdiction indicated that the alleged misconduct had recently

occurred—less than five years before the StateBar’s decision to

close the case with a warning letter. e StateBar does not consider

a warning letter to be a disciplinary action, and thus its response

was not reciprocal, given that the other jurisdiction ordered that the

attorney be permanently prohibited from practicing law. Because

the StateBar did not impose any public reciprocal discipline, the

attorney has no public record of misconduct in California. Based

on the attorney’s history of practicing law with a suspended license

and failing to comply with the agreement with the other state to

resign from practice in California, the lack of public discipline by

the StateBar increases the risk that this attorney could engage in

similar inappropriate behavior in the future.

In another of the cases we reviewed, the StateBar did not take

proactive steps to inform the public that another jurisdiction

had temporarily suspended the attorney to protect the public

from further misconduct while the case was being decided.

CaseExample4 describes this instance. State law considers

a certified copy of a final order determining that an attorney

committed professional misconduct by a court or body authorized

to discipline attorneys in another jurisdiction as conclusive

evidence that the attorney is culpable of professional misconduct in

California. Because the case in the other jurisdiction was not final

until January 2022, the StateBar could not have imposed discipline

before then based solely on the actions of that other jurisdiction.

However, state law does allow the StateBar to initiate and conduct

The StateBar does not proactively identify

discipline imposed by otherjurisdictions.

[Insert CaseExample3]

21California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

investigations of the conduct in other jurisdictions of attorneys

licensed in California. According to the intake manager, it seemed

more prudent to allow this case to reach its conclusion in the other

jurisdiction, at which point all of the facts that the other jurisdiction

could prove would be available to the StateBar. However, there

are other options available to the StateBar to address the risk of

harm the attorney posed to the public. According to the Rules of

Procedure of the StateBar of California, if an attorney is under

investigation by a regulatory or licensing agency, the chief trial

counsel may disclose information for the protection of the public

after privately notifying the attorney. us, the StateBar could

have informed the public on its website that this attorney had been

CaseExample3

Case Example 3

Case Example 1

In another state, an attorney was charged

with several violations of that state’s Rules of

Professional Conduct, including continuing to

advertise and practice law while suspended.

The attorney requested to permanently

resign from practicing law in that state and in

all other jurisdictions—specifically including

an agreement to resign in California—in lieu

of receiving discipline in that state. The

supreme court of that state issued an order

approving the request and further ordered that the

attorney be permanently prohibited from practicing

law, an action that state considered to be a public

reprimand. With limited exceptions, California state law

provides that the final order of discipline from the other

jurisdiction is conclusive evidence that the attorney is

culpable of misconduct in California.

However, the State Bar concluded that it could not use

the other state’s supreme court order permanently

prohibiting this attorney from practicing law as

conclusive evidence of a final order of discipline because

the other state’s supreme court order did not include a

final determination or finding on the attorney’s

misconduct. Instead, the State Bar used its authority to

open an investigation against the attorney. Ultimately,

the State Bar issued the attorney only a private warning

letter, thereby permitting the attorney to continue to

practice law in California despite the attorney’s

agreement in another state to resign from practicing

law in all jurisdictions. Subsequent to the warning letter,

the attorney resigned from the California State Bar.

Case Example 3

22 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

CaseExample4

Case Example 4

Case Example 1

The supreme court of another

state temporarily suspended an

attorney in that state in 2020 for

misappropriating and misusing

client funds. The attorney was

also licensed to practice law in

California. The supreme court in

that state also placed

restrictions on the attorney’s handling of client funds,

concluding that the attorney posed a substantial

threat of serious harm to the public. According to

documents in the State Bar case file, that state’s

supreme court ultimately disbarred the attorney in

early 2022. Although the State Bar had been aware of

the attorney’s temporary suspension in the other state

since April 2021, it had not imposed discipline as of

February 2022.

Case Example 4

suspended in another state. e chief trial counsel agreed that doing so

could enhance public protection when another state has concluded that

an attorney presents a threat of harm to the public. However, because of

the StateBar’s inaction, current and potential clients in California were not

informed of the threat the attorney posed for more than a year after the

attorney was suspended in the otherjurisdiction.

e StateBar also has not actively sought information on attorney

discipline in other jurisdictions. e intake manager said that the StateBar

may open a case if it becomes aware of discipline imposed on a California

attorney in another jurisdiction through media reports or other means.

However, he also stated that there is no unit within the StateBar charged

with proactively seeking information on discipline imposed in other

jurisdictions. According to the intake manager, the StateBar opens cases

based on attorney self-reporting and reporting from other jurisdictions.

However, relying on attorneys to volunteer that they have been disciplined

is not an effective process, as they do not always do so in a timely manner.

Further, attorneys who commit misconduct warranting disbarment in other

jurisdictions have little incentive to report that misconduct to the California

StateBar. According to the intake manager, there is no attorney discipline

beyond disbarment. erefore, an attorney may not be motivated to report

the misconduct if they anticipate that they will be disbarred.

[Insert CaseExample4]

23California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

State law requires the StateBar to notify the appropriate discipline

agencies in any other jurisdictions where an attorney is admitted

to practice if it suspends or disbars an attorney or if it reinstates a

suspended or disbarred attorney. Other jurisdictions may have similar

rules. e special assistant to the chief trial counsel stated that he is not

aware of any agreements that the StateBar has with other jurisdictions

to share such information.

An attorney discipline agency in another state may not necessarily

report to the StateBar the discipline it imposes on attorneys also

licensed in California. For example, in one StateBar discipline case

we reviewed, another state’s attorney discipline oversight body

noted in court documents requesting a suspension that the attorney

was admitted to the California StateBar. However, according to the

California StateBar, it has no record of receiving information about this

disciplinary action.

Because it has relied on attorneys and other discipline agencies to

report instances of discipline in other jurisdictions, the StateBar

did not learn about some disciplinary actions until a year or more

after they were imposed. Of the 32 cases that we reviewed related

to 20attorneys that pertained to discipline in other jurisdictions,

we found 10 instances in which discipline was imposed by the other

jurisdiction, but the StateBar was not notified for one year or longer.

For example, as CaseExample5 describes, had the attorney not

chosen to self-report the discipline when reapplying to practice law in

California, the StateBar might never have learned of themisconduct.

In contrast to its current approach, the StateBar could take advantage

of existing information about attorney discipline imposed in other

jurisdictions. e American Bar Association maintains the National

Lawyer Regulatory Data Bank (data bank) for regulators, such as the

StateBar, to use to facilitate reciprocal discipline. e data bank is a

repository of information concerning public regulatory actions related

to lawyers throughout the United States. According to the intake

manager, StateBar staff do not regularly use the databank to proactively

identify attorneys disciplined in other jurisdictions. e StateBar’s

failure to use this resource increases the risk that those attorneys will

continue to practice in California and engage in misconduct here.

The Information That the StateBar Provides Its Staff Limits Their Ability to

Identify Patterns of Complaints

Patterns of complaints can provide useful information about the impact

of the StateBar’s corrective actions and whether new complaints

merit investigation. Although the StateBar directs its staff to look

for patterns when reviewing new complaints, we found that the tools

available to staff limit their ability to effectively do so.

We found instances among

the cases we reviewed in which

discipline was imposed on an

attorney by another jurisdiction,

but the StateBar was not notified

for one year or longer.

[Insert CaseExample5]

24 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

For the purposes of this audit, we defined three or more separate

complaints for a single attorney involving similar allegations

within a span of 12 months to be a pattern of complaints. Although

patterns of complaints are not evidence of misconduct, they can

indicate whether the disciplinary or nondisciplinary measures

that the StateBar imposes are having an effect on the attorney’s

behavior. A pattern of complaints may also indicate that a

new complaint merits additional investigation. e StateBar’s

procedures require intake attorneys reviewing a new complaint to

research whether the attorney has a history of closed complaints,

closed investigations, discipline, or pending matters in order to

assess the possibility of a pattern of complaints or misconduct.

We reviewed the case history of 19 attorneys who each had 25 or

more complaints. Of those attorneys, we identified 17 who exhibited

a pattern of complaints. In some cases, the pattern involved a

significant number of complaints over an extended period. For

example, over the course of about two and a half years, there were

29 cases opened against the attorney in CaseExample2, all based on

allegations that the attorney failed to provide funds owed to clients.

CaseExample5

Case Example 5

Case Example 1

An attorney licensed to practice

law in California and in another

state was suspended in the other

state in 2007. The attorney did not

notify the State Bar of the

suspension within the statutory

30-day deadline and, in 2008, let

their California license become

inactive. When seeking to become active again in

2021, the attorney informed the State Bar of the

2007 discipline. The State Bar might have

readmitted the attorney without considering the

past misconduct if the attorney had not shared

this information. As of February 2022, the State Bar

is considering potential discipline of the attorney

for the misconduct in the other state and for failing

to disclose the past misconduct to the State Bar.

Case Example 5

25California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

e patterns of complaints against some attorneys suggest that

the StateBar’s responses to those complaints did not influence

the attorneys’ subsequent behavior. We determined that there

were 212 attorneys with six or more complaints that were closed

through nonpublic measures from 2010 through 2021. e patterns

of complaints we identified for 10 of the 19 attorneys we reviewed

occurred after the StateBar had closed cases involving allegations

of similar types of misconduct through nonpublic measures. For

example, the timing of the pattern of failing to provide settlement

payments or return client files described in CaseExample1

demonstrates that the StateBar’s use of nonpublic measures did

not deter the attorney from continuing the conduct and generating

similar complaints. Had the StateBar considered the pattern of past

conduct, it might have conducted further investigation, which could

have resulted in more severe corrective action and discouraged the

attorney from continuing this conduct.

In addition, a pattern of past complaints can indicate that a new

complaint merits further investigation. For instance, CaseExample2

describes a pattern of complaints against an attorney alleging that

the attorney had not provided funds to several clients, and the

StateBar closed these complaints as resolved after the attorney

paid each complainant. Had the StateBar treated the pattern

of complaints as an indicator that new complaints warranted

investigation, it might have discovered the misappropriation sooner

and mitigated harm to the attorney’sclients.

After we brought our concerns about its process for identifying

patterns of complaints to the StateBar’s attention, it issued a

policy directive clarifying procedures for intake staff to use when

considering prior closed complaints in their determination of

whether to close or investigate a complaint. e policy directive states

that prior closed complaints of a similar nature may support the

plausibility of certain allegations. It also notes that a history of similar

closed complaints may suggest the need for investigative steps to

generate sufficient evidence about whether a violation has occurred.

Although it has now clarified how patterns of complaints should be

addressed, StateBar staff lack the tools to effectively and efficiently

conduct such a review. e StateBar’s case management system

allows staff to access all cases against an attorney for the most

recent five years, and cases older than five years that resulted in

discipline and nondisciplinary measures. However, the report

showing the past cases against an attorney that the StateBar’s

case management system generates describes those cases using

individual allegation types rather than general categories. As of

January 2022, there were 672 different allegation types. For example,

the StateBar has established 46 allegation types related to client

or entrusted funds. Because the case management system uses a

A pattern of past complaints of attorney

misconduct can indicate that a new

complaint merits further investigation.

26 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

detailed allegation type for each case, the numerous types makes

it difficult to identify patterns of similar behavior. e chief trial

counsel agreed that categorizing allegations into broader categories

would allow staff to more easily identify patterns of complaints. e

StateBar has already grouped the allegation types into 25 general

categories for use as a research tool outside of the case management

system. However, according to the chief trial counsel, the StateBar

is still assessing how best to use this case categorization in its

handling of cases.

The StateBar Failed to Accurately Track or Document Its

Consideration of Some Staff Members’ Potential Conflicts of Interest

According to the Rules of Procedure of the StateBar, the chief

trial counsel is required to recuse the trial counsel’s office from

inquiries or complaints against attorneys if a conflict of interest

or the appearance of a conflict of interest could raise doubts

that the chief trial counsel would be impartial. To make this

determination, the StateBar requires its employees to complete

an annual questionnaire in which they disclose personal, financial,

and professional relationships they have with licensed California

attorneys. e StateBar then adds these attorneys to a list (conflicts

list). Further, the StateBar can flag these attorneys in its case

management system. When the StateBar identifies a conflict, the

trial counsel’s office can assign the case to outside prosecutors, who

are attorneys contracted by the StateBar or, in certain situations,

recuse only those employees who have a connection to the case.

e StateBar relies on its employees to identify potential conflicts of

interest at both the intake and investigation stages. Its intake manual

requires the employee processing a complaint to check whether

the attorney identified in each complaint has a relationship with

the StateBar that presents a potential conflict. If the employee then

identifies such a potential conflict, a supervising attorney refers the

case to an independent administrator contracted by the StateBar, who

recommends whether the case should be processed by a StateBar

employee with no declared relationship to the case or by an outside

prosecutor. In addition, StateBar policy requires that employees notify

their supervisors as soon as possible if a potential conflict arises or

becomes known after a case has been opened.

Despite its staff identifying attorneys with whom they have

a conflict of interest, in 11 of 30 cases we reviewed where the

attorney was on the conflicts list, the StateBar did not document

its consideration of those conflicts. In seven of those 11 cases,

the attorney was on the conflicts list but was not flagged in the

StateBar’s case management system, and the case notes do not

describe any evaluation of the conflict of interest. In the other

The StateBar relies on its employees

to identify potential conflicts of

interest at both the intake and

investigation stages.

27California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

fourcases, the attorney was flagged as having a conflict of interest,

but intake staff proceeded to review the cases and ultimately closed

the cases without involving the independent administrator or

documenting the steps the StateBar took to mitigate the conflict

ofinterest.

e StateBar does not appear to recognize the significance of the

risk associated with dismissing a case against an attorney on the

conflicts list. For one of the cases, the intake attorney documented

an email exchange with his supervisor in which the supervisor

acknowledged the conflict of interest but nonetheless directed the

intake attorney to review the case anyway and agreed with the intake

attorney’s proposal to dismiss the case. In another case, the intake

attorney did not document any evaluation of the conflict of interest

in the case file, but in response to our questions, she provided

an email from her supervisor stating that the conflict-of-interest

requirements were waived and he approved closing the case. e

chief trial counsel believes that the cases in which an attorney

attempts to exert undue influence on a StateBar employee or in

which a StateBar investigator or attorney intentionally attempts

to influence the case are extremely rare and would be difficult

to prevent. Nevertheless, the decisions to close cases described

above illustrate that the StateBar is not appropriately assessing

how conflicts of interest pose a risk that staff will close cases

inappropriately. us, it is critical that the StateBar objectively assess

and document its consideration of conflicts of interest when closing

a case at the intake stage against an attorney on the conflicts list.

e chief trial counsel agreed with our findings and indicated

management of conflicts of interest is an area where the StateBar

needs much improvement. He further noted that conflict-of-interest

information has not been consistently updated in its current case

management system, and he is working with his staff to correct

thatissue.

The StateBar’s Weak Safeguards Have Hampered Its Ability to Prevent

Repeated Client Trust Account Violations

Despite establishing formal guidance in an intake manual in 2018

for reviewing certain complaints related to client trust accounts, the

StateBar has not consistently followed it. In several instances, the

issues we describe in the previous sections have contributed to the

StateBar’s failure to appropriately review cases of alleged client trust

account violations. For example, the StateBar has used nonpublic

measures to close cases involving client trust account violations, and

an attorney’s prior history of allegations did not appear to affect the

StateBar’s decision to close certain client trust account cases.

It is critical that the StateBar

objectively assess and document its

consideration of conflicts of interest

when closing a case at the intake

stage against an attorney on the

conflicts list.

28 California State Auditor Report 2022-030

April 2022

When attorneys or law firms receive funds on behalf of clients, such

as fees paid in advance for future services or proceeds from insurance

settlements, the StateBar’s Rules of Professional Conduct require these

funds be deposited into one or more client trust accounts. A primary

reason for maintaining client trust accounts is to ensure that funds

being held for the benefit of clients are not commingled with those of

the attorney or law firm. A client trust account also provides protection

against seizure of client funds by third parties or in the event that the

attorney declares bankruptcy. According to the StateBar’s Handbook

on Client Trust Accounting for California Attorneys, an attorney may

deposit funds related to multiple clients into a single client trust account

if the attorney keeps an accurate record of the amounts that belong

to each client. As part of the requirements for safekeeping of funds

and property of clients and other persons, the StateBar’s Rules of

Professional Conduct require attorneys to maintain, among other things,

monthly reconciliations of their client trust accounts. e reconciliation

process involves comparing the three basic types of records attorneys

are required to keep—bank statements, client ledgers, and account

journals—against each other to find and correct any mistakes.

From 2010 through 2021, 23percent of all StateBar cases involved

allegations related to client trust accounts. e StateBar receives

complaints about alleged client trust account violations from different

sources, such as from clients who believe that an attorney has acted

improperly, or through reportable actions, which are mandatory

reports about events concerning attorneys. Reportable actions are

submitted by entities such as courts and banks and include court orders,

sanctions, and overdraft notices for client trust accounts. According to

the StateBar, bank notifications about insufficient funds in client trust

accounts, or bank reportable actions, make up the largest number of

reportable actions.

It is critical for the StateBar to thoroughly review complaints regarding

client trust accounts because of the potential for attorneys to misuse

funds in these accounts and the harm that such misuse can cause to the

attorney’s clients. For example, an attorney could commingle personal

assets with a client’s assets, making it unclear to whom the funds

belong and risking that the attorney or his or her creditors will seize

the client’s funds. A serious misuse of a client trust account, known

as misappropriation, occurs when an attorney uses client funds for

personal benefit or otherwise fails to maintain the required balance of

client funds in the account.