1

Introduction

The Republic of Turkey has often been governed under the state of emergency (SoE) regimes

since its proclamation in 1923. SoE government procedures have been implemented for a total of 43

years in Turkey, including a total of 41 years covering 26 years of martial law regime at various times

between 1923 and 1987 and a 15-year-long state of emergency between 1987 and 2002 in addition to

a 2-year-long SoE between 2016 and 2018.

1

During these emergency periods, amendments were usually introduced to many laws, most

notably to constitutions; either new constitutions were drafted as was the case in military coup periods

in 1961, 1971 and 1980 or legislative amendments that restricted fundamental rights and freedoms

were introduced in individual laws.

The latest SoE regime was declared in the aftermath of the coup d’état attempt of 15 July 2016.

The government, exercising the power granted by Article 120 of the Constitution of the Republic of

Turkey, declared a 3-month SoE all over the country starting on 21 July 2016 within the scope of

Article 3(1)(b) of Law No. 2935 on State of Emergency. Following the first three months, SoE was

extended 7 times and was finally lifted on 18 July 2018.

2

The government started issuing decree laws [kanun hükmünde kararname] that restricted

fundamental rights and freedoms in the aftermath of the declaration of SoE following the failed coup

attempt staged against the government on 15 July 2016. These decree laws are necessarily exempt

from judicial review. The Constitutional Court recanted its “previous” case-law in its judgment on

emergency decree laws in 2016 holding that emergency decree laws were not subjected to

constitutionality review.

3

Although the SoE was lifted, these decree laws were enacted into laws to be

implemented in states/conditions of non-emergency through Law No. 7145 and Law No. 7333.

SoE decree laws have two implications on the human rights field in Turkey with regards to their

content and practice. Firstly, they resulted in the corrosion of the principle of rule of law and in the

unlawful governance of the field of fundamental rights and freedoms in Turkey as per procedure.

1

For documents and assessment of the period up to 1991, see. M. Semih Gemalmaz. Olağanüstü

Rejim Standartları. 1994.

2

For a detailed analysis of the SoE period and emergency decree laws, see Human Rights Joint

Platform’s (HRJP) “Updated Situation Report: State of Emergency in Turkey 21 July 2016-20

March 2018” https://ihop.org.tr/en/2018/04/25/updated-situation-report-state-of-emergency-in-

turkey-21-july-2016-20-march-2018/

3

For a comprehensive analysis of emergency decree laws, see the information note entitled “Atipik

KHK’LER ve Daimi Hukuksuzluk: OHAL KHK’si ile erkeği kadın, kadını erkek yapamazsınız!” co-

authored by Kerem Altıparmak, Dinçer Demirkent and Murat Sevinç. http://www.ihop.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/2018/04/Atipik-OHAL-KHKleri_II-1.pdf

2

Secondly, they led to the shrinking of the activity field of current human rights struggle in many ways

in their practice. Therefore, the first part of this report will address the standards in restricting rights

and freedoms in major national and supranational human rights documents while discussing the

legality of declaration of SoE and its successive extensions, and the second part will focus on

interferences with human rights and freedoms in the unlawful environment brought about through and

by decree laws themselves with regards to human rights and freedoms beginning with 15 July 2016

extending today as well as their impact on a diverse set of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Certain prominent cases will be offered as samples in order for us to comprehend these implications

on the human rights struggle in everyday life. The final part will offer recommendations with an eye to

the elimination of problems brought about by the SoE and emergency decree laws and the

consequences of the violations they led to.

3

Declaration of SoE and Turkey’s Obligations

A coup attempt was plotted in Turkey on 15 July 2016 against the government that took office by

the popular vote. Military officers and non-commissioned officers of the Turkish Armed Forces that

attempted to stage a coup used a variety of arms including heavy weaponry like fighter jets and tanks.

245 citizens, including 173 civilians, lost their lives while 2,194 citizens were wounded during these

attacks. Coup plotters wounded numerous people (anti-coup public officials and civilian citizens who

resisted them). Coup plotters also bombarded the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (GNAT), the

legislative organ of the state. Following the quenching of the attempted coup on 16 July 2016, the

council of ministers (government) convening under the chairpersonship of the president on 20 July

2016 declared SoE for three months throughout the country under Article 120 of the then current

Constitution. The decision rendered by the council of ministers was ratified a day later on 21 July 2016

by the GNAT.

Constitution of the Republic of Turkey, Article 120 [Repealed]

In the event of serious indications of widespread acts of violence aimed at the destruction

of the free democratic order established by the Constitution or of fundamental rights and

freedoms, or serious deterioration of public order because of acts of violence, the Council

of Ministers, meeting under the chairmanship of the President of the Republic, after

consultation with the National Security Council, may declare a state of emergency in one or

more regions or throughout the country for a period not exceeding six months.

SoE was extended for another three months each time by the council of ministers convening under

the chairpersonship of the president and these extension decisions were ratified by the GNAT. This

process resumed until 19 July 2018 with three-month extensions. The committee of ministers

rendered a total of 32 emergency decree laws under the then in-effect Article 121 of the Constitution.

4

5 other decrees, other than these 32 emergency decree laws

5

, numbered 698, 699, 700, 702 and 703

also went into force as ordinary decree laws during the same timeframe.

4

For a full record of decree laws issued during the SoE, see appendix “State of Emergency

Decree Laws, Their Publishing in the Official Gazette and Their Content in Brief.”

5

The Constitutional Court stated the following in its judgment of 26 January 2022 (Merits No.

2020/17, Judgment No. 2020/17) published in the Official Gazette of 1 April 2022 on the Decree

Law No. 682 (Law No. 7068): “Law No. 7068, which includes the rule appealed against, went into

force as a result of the ratification by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey of the Decree Law

No. 682 on General Law Enforcement Disciplinary Provisions of 2 January 2017 that was issued

within the scope of the state of emergency” (para. 17). The Constitutional Court, thus, qualifies

4

One can summarize the prominent features and consequences of emergency decree laws as

such:

• More than 130,000 public employees were dismissed from their posts through decree laws.

These employees did not only consist of such officials as military officers, non-

commissioned officers, police officers and intelligence officers who were actively involved in

the coup attempt. They were public servants holding office almost at every level within the

state organization.

• Along with the dismissal of public employees from their posts, in other words their lustration

from the state apparatus, not only their passports but those of their spouses and children

were also cancelled.

• Arms permits, ship’s crew documents or piloting licenses held by these individuals were

also cancelled.

• Those dismissed were evacuated from public-owned residences, lodgments within 15 days.

• Those dismissed were dismissed for good; they will not be able to hold offices in public

services anymore.

• Thousands of those dismissed were subjected to arrests and detentions.

• Private institutions and organizations, educational institutions, press, newspapers, journals,

TV channels, universities, foundations and associations, etc. were permanently shut down

on the grounds of their alleged “affiliation, contact or junction” [mensubiyet, irtibat or iltisak]

with the attempted coup or terrorism. Their movable and immovable property were seized,

confiscated.

The fact, however, is that the law on SoE is the Law No. 2935 on the State of Emergency dated

1983. Under these circumstances, all emergency decree laws issued within the framework of Article

121/3 of the Constitution should have to be in accordance with Law No. 2935 on the State of

Emergency. Moreover, a permanent measure exceeding the SoE timeframe and violating principles of

proportionality, effectiveness, constitutionality, rule of law, fundamental rights and democracy is

blatantly in violation of the standards of the Council of Europe, as has also been referred to in the

case-law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and reports by the Venice Commission.

SoE Extension Decisions and Soe Decree Laws

The SoE was extended for a total of 7 times by the committee of ministers under Article 3 of Law

No. 2935 on State of Emergency beginning with 21 July 2016 and the latest covered the period

between 19 April 2018 and 18 July 2018 while these extension decisions were ratified by the Plenary

of the GNAT.

Decree Law No. 682 as a decree law that was issued “within the scope of state of emergency.”

Therefore, Decree Law No. 682 is referred to as an emergency decree law in our study.

5

Law No. 2935 on State of Emergency

6

Article 3 - (b)

(…) The state of emergency decision shall be published in the Official Gazette and

immediately be submitted for approval of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. If the

Grand National Assembly of Turkey is in recess, it shall be summoned to convene

immediately. The Assembly may amend the duration of the state of emergency. Upon a

request from the Council of Ministers, the Assembly may extend the duration each time for

a period not exceeding four months, or it may terminate the state of emergency. The

Council of Ministers after declaring a state of emergency in accordance with provision (b),

shall also consult the National Security Council before rendering a decision on questions

related to the extension of the duration, alternation of the scope, or the termination of the

state of emergency. (…)

A total of 32 decree laws were issued during the SoE under Article 121 of the Constitution and they

were published in the Official Gazette. It has, however, been observed that procedures were not

followed during the ratification of many decree laws. Such state of affairs reveals that the legislative

branch could not duly and pertinently review the executive branch’s acts, while the executive branch

used the power of the legislative branch through normative regulations (decree laws) until the time

when legislative checks would be provided.

For instance, decree laws nos. 672 and 673 that were published in the Official Gazette on 1

September 2016 were submitted to the Plenary of the GNAT a year and six months after they went

into force, while they were ratified on 6 February 2018 having been deliberated at the Plenary and

published in the Official Gazette on 8 March 2018 as Law No. 7080 and Law No. 7081 respectively.

This issue is covered by Article 121 of the Constitution. Accordingly, “Decrees shall be published in

the Official Gazette, and shall be submitted to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on the same

day for approval; the duration and procedure for their approval by the Assembly shall be indicated in

its Rules of Procedure.” Article 128 of the GNAT’s Rules of Procedure sets forth that if deliberations

on the decrees fail to be concluded in the committees, within twenty days the latest, the Office of the

Speaker puts them on the agenda of the Plenary to be deliberated immediately within thirty days.

Out of a total of 32 SoE decree laws, a committee was convened merely for one, while 31 decree

laws were sent directly to the Plenary because they were not deliberated. 5 (667, 668, 669, 671, 674)

) out of 12 decree laws issued in 2016 were deliberated at the Plenary of the GNAT 3 months after

having been published in the Official Gazette in the same year, the remaining 7 decree laws (670,

672, 673, 675, 676, 677, 678) were deliberated at the Plenary 14 to 16 months after having been

published in the Official Gazette in 2018, while 18 decree laws (679–696) issued in 2017 were

deliberated at the Plenary 13 months after having been published in the Official Gazette in 2018 and

all were passed into laws.

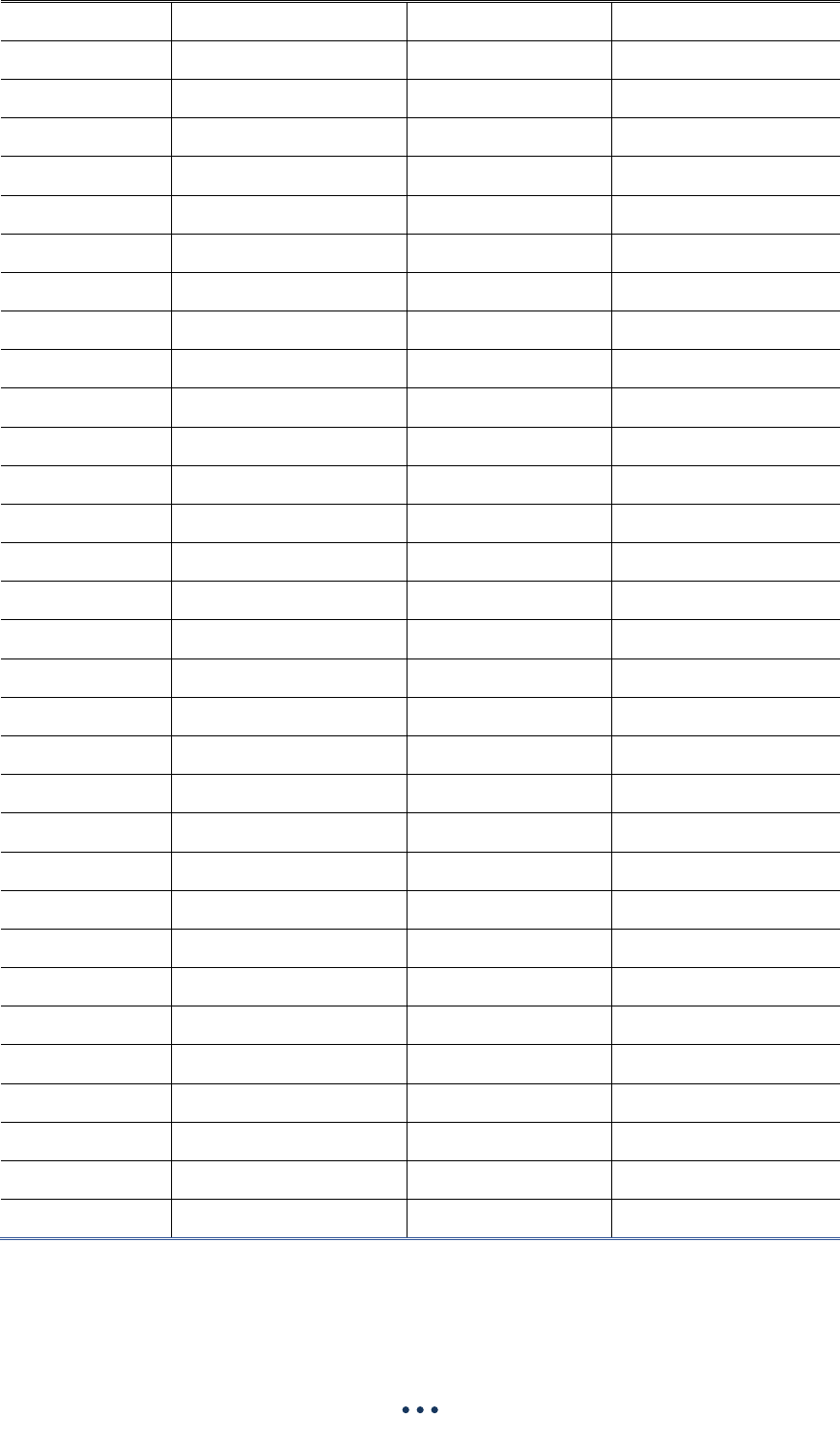

Decree law no. 697 issued in 2018 was deliberated at the Plenary of the GNAT within a month,

while the last decree law of the state of emergency, decree law no. 701, was passed into law after

having been deliberated at the Plenary 3 months after it was issued. The following table presents the

timeline of decree laws passed into laws:

The Timeline of Decree Laws Passed into Laws

Decree Law No

Official Gazette

Law No

Official Gazette

6

For the full text of Law No. 2935 on State of Emergency, see:

https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.5.2935.pdf

6

667

23.07.2016

6749

29.10.2016

668

27.07.2016 Doublet

6755

24.11.2016

669

31.07.2016

6756

24.11.2016

670

17.08.2016

7091

08.03.2018 Doublet

671

17.08.2016

6757

24.11.2016

672

01.09.2016 Doublet

7080

08.03.2018 Doublet

673

01.09.2016 Doublet

7081

08.03.2018 Doublet

674

01.09.2016 Doublet

6758

24.11.2016

675

29.10.2016

7082

08.03.2018 Doublet

676

29.10.2016

7070

08.03.2018 Doublet

677

22.11.2016

7083

08.03.2018 Doublet

678

22.11.2016

7071

08.03.2018 Doublet

679

06.01.2017 Doublet

7084

08.03.2018 Doublet

680

06.01.2017 Doublet

7072

08.03.2018 Doublet

681

06.01.2017 Doublet

7073

08.03.2018 Doublet

682

23.01.2017

7068

08.03.2018 Doublet

683

23.01.2017

7085

08.03.2018 Doublet

684

23.01.2017

7074

08.03.2018 Doublet

685

23.01.2017

7075

08.03.2018 Doublet

686

07.02.2017 Doublet

7086

08.03.2018 Doublet

687

09.02.2017

7076

08.03.2018 Doublet

688

29.03.2017 Doublet

7087

08.03.2018 Doublet

689

29.04.2017 Doublet

7088

08.03.2018 Doublet

690

29.04.2017 Doublet

7077

08.03.2018 Doublet

691

22.06.2017 Doublet

7069

08.03.2018 Doublet

692

14.07.2017 Doublet

7089

08.03.2018 Doublet

693

25.08.2017

7090

08.03.2018 Doublet

694

25.08.2017

7078

08.03.2018 Doublet

695

24.12.2017

7092

08.03.2018 Doublet

696

24.12.2017

7079

08.03.2018 Doublet

697

12.01.2018

7098

08.03.2018 Doublet

701

08.07.2018

7150

03.11.2018 Doublet

The objective of decree law no. 667, as set forth in its Article 1, is to “identify the necessary

measures to be taken within the scope of the state of emergency declared throughout the country

7

within the framework of the coup attempt and counter-terrorism, and the related procedures and

principles.”

The decree law states that public employees assessed to be a member of, belonging to or acting in

junction or contact with terrorist organizations or structures, formations or groups decided to have

been acting against the national security of the state by the National Security Council would be

dismissed from their public posts. The decree law also regulates the ways in which judges would be

removed from office. SoE Law no. 2935 does not set forth a legal regulation on the removal of judges

from office. Moreover, there is no provision as to the liquidation of other public officials, not only

judges. Permanent closure / liquidation of legal persons (the law refers to them as associations) is not

covered by Law No. 2935 either. The final paragraph of Article 11 of the law merely mentions that an

association’s activities can be suspended on the condition that it does not exceed three months.

Further, it is resolved that this needs to be done individually for each association.

Articles 3 and 4 of decree law no. 667 prescribe that judges and other public officials may be

dismissed upon decisions rendered by related judicial organs or administrative bodies. Article 2 of

decree law no. 668 incorporates a list of public officials to be dismissed and of press institutions to be

closed down by the decree law. All assets belonging to those in the list are passed down to the state

treasury permanently and without charge. The above-mentioned regulations are literally repeated in

all dismissal decrees as well as provisions on movable and immovable property. All these measures

are permanent. Dismissals are permanent. Revoking licenses are permanent. Confiscation of

movable and immovable property free of charge is permanent. Further, issue of stay orders cannot be

rendered in court cases brought against decisions and measures taken within the scope of decree

laws under Article 10/1 of decree law no. 667.

The Venice Commission’s “Opinion on Emergency Decree Laws Nos. 667-676 Adopted following

the Failed Coup of 15 July 2016”

7

underlined the fact that the same results could have been achieved

through temporary measures instead of permanent ones in paragraph 85.

85. The risk of a repeated coup may be significantly reduced if the supposed Gülenists, as

a precautionary measure, were suspended from their posts, and not dismissed. Similarly,

instead of definitely confiscating all assets of organizations, it may suffice to temporarily

freeze large amounts on their bank accounts or prevent important transactions, to appoint

temporary administrators and to allow only such economic activity which may help the

organization in question to survive until its case is examined by a court following normal

procedures. Temporary measures of this type also ultimately make possible fairer

examination of the correctness of the decisions being made according to ordinary judicial

process.

The Venice Commission, which set forth that some provisions in the decree laws were permanent

noting that such state of affairs did not comply with the temporariness of the SoE (para. 87) and

offered examples to this end (para. 88):

87. (...) While certain measures introduced by the decree laws are clearly temporary, other

measures make changes to the current legislation, and the decree laws do not indicate that

these measures will cease to apply after the end of the emergency period. Thus, the

authorities intend to keep these measures in the legislation permanently.

7

https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2016)037-e

8

88. Thus, for example, Article 23 of Decree Law No. 671 abolishes the Telecom

Presidency and transfers its functions to the Information and Communication Technologies

Authority. Article 25 of this Decree Law establishes a new procedure for authorizing

wiretapping of telecommunications and obtaining access to electronic data archives. It thus

amends current Article 60 of the Electronic Communications Law. Article 16 of Decree Law

No. 674 amends Law No. 5275 on the execution of penalties and security measures, giving

the Chief Public Prosecutor the power to restrict the detainees’ “temporary leave” from

penitentiary institutions and detention centers. (…)

Restrictions on Fundamental Rights and Freedoms through

Emergency Decree Laws

Restrictions can be imposed on the implementation of the articles of international and regional

human rights conventions or covenants that a country is a party to and these articles can be

suspended during states of emergency. The important fact, however, is that these restrictions are

subjected to notification and supervision. Moreover, such suspensions or derogations are not valid for

convention or covenant articles that cannot be restricted or derogated from. The Republic of Turkey is

a party to the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the

European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The below-cited articles of this covenant and

convention list human rights and freedoms that the states are not allowed to derogate from and

cannot take measures in violation of them.

UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 4

Derogation in time of emergency

1. In time of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of

which is officially proclaimed, the States Parties to the present Covenant may take

measures derogating from their obligations under the present Covenant to the extent

strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that such measures are not

inconsistent with their other obligations under international law and do not involve

discrimination solely on the ground of race, color, sex, language, religion or social origin.

2. No derogation from articles 6, 7, 8 (paragraphs I and 2), 11, 15, 16 and 18 may be made

under this provision.

3. Any State Party to the present Covenant availing itself of the right of derogation shall

immediately inform the other States Parties to the present Covenant, through the

intermediary of the Secretary-General of the United Nations, of the provisions from which it

has derogated and of the reasons by which it was actuated. A further communication shall

be made, through the same intermediary, on the date on which it terminates such

derogation.

The following rights are regulated in the articles listed in the second paragraph of Article 4:

The right to life (Art. 6), prohibition of torture (Art. 7), prohibition of slavery and servitude

(Art. 8), prohibition of imprisonment merely on the ground of inability to fulfil a contractual

obligation (Art. 11), no punishment without law (Art. 15), right to recognition as a person

before the law (Art. 16), right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Art. 18).

No derogations are allowed about these rights and freedoms as is stated in Article 4/2.

from these obligations

European Convention on Human Rights, Article 15

9

Derogation in time of emergency

1. In time of war or other public emergency threatening the life of the nation any High

Contracting Party may take measures derogating from its obligations under this

Convention to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that

such measures are not inconsistent with its other obligations under international law.

2. No derogation from Article 2, except in respect of deaths resulting from lawful acts of

war, or from Articles 3, 4 (paragraph 1) and 7 shall be made under this provision.

In this case, rights and freedoms from which no derogation is allowed and no inconsistent

measures can be taken under Article 15/2 of the ECHR are: rights to life (Art. 2), prohibition

of torture (Art. 3), prohibition of slavery and servitude (Art. 4/1), and no punishment without

law (Art. 7).

Turkey, a party to the human rights conventions and covenants by the Council of Europe and the

United Nations, notified the Secretary General of the Council of Europe immediately after the

declaration of the SoE on 21 July 2016 under Article 15 of the ECHR and the UN Secretary General

on 2 August 2016 under Article 4 of the ICCPR. Turkey also clearly communicated to the UN from

which articles of the covenants it would derogate but the authorities confined themselves to submitting

a mere general statement to the Council of Europe.

The ECtHR noted in its judgment in the case of Mehmet Hasan Altan v. Turkey (application no.

13237/17, judgment date: 20.03.2018) on Turkey’s notification to the Council of Europe within the

context of Article 15:

The Court accepts that the notice of derogation by Turkey satisfied the formal requirement

laid down in Article 15/3 of the Convention, namely to keep the Secretary General of the

Council of Europe fully informed of the measures taken by way of derogation from the

Convention and the reasons for them. The Court further notes that under Article 15 of the

Convention, any High Contracting Party has the right, in time of war of public emergency

threatening the life of the nation, to take measures derogating from its obligations under

the Convention, other than those listed in paragraph 2 of that Article, provided that such

measures are strictly proportionate to the exigencies of the situation and that they do not

conflict with other obligations under international law.

The government notified the UN that it would impose restrictions on a total of 13 articles of the

ICCPR. The articles derogated from included “right to an effective remedy in case of a violation”

among the General Provisions under Article 2, right to liberty and security of person (Art. 9), rights of

persons deprived of their liberty (Art. 10), liberty of movement (Art. 12), procedural guarantees against

the deportation of foreign nationals (Art. 13), freedom of expression (Art. 19), freedom of assembly

(Art. 21), freedom of association (Art. 22), political rights (Art. 25), equality before law (Art. 26),

protection of minority rights (Art. 27).

As per domestic law, there are also provisions on rights from which no derogation is allowed in

times of war and states of emergency in Article 15/2 of the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey.

Article 15 stated the following as of the attempted coup of 15 July 2016 before it was amended (the

term “martial law” was removed from the paragraph through Article 16 of Law No. 6771 dated

21/1/2017):

IV. Suspension of the exercise of fundamental rights and freedoms

10

Article 15 – In times of war, mobilization, martial law or a state of emergency, the exercise

of fundamental rights and freedoms may be partially or entirely suspended or measures

derogating the guarantees embodied in the Constitution may be taken to the extent

required by the exigencies of the situation, as long as obligations under international law

are not violated.

(Miscellaneous: 7.5.2004-5170/2 Art.) Even under the circumstances indicated in the first

paragraph, the individual’s right to life, the integrity of their physical and psychological

existence shall be inviolable except where death occurs through acts in conformity with law

of war; no one shall be compelled to reveal their religion, conscience, thought or opinion,

nor be accused on account of them; offenses and penalties shall not be made retroactive;

nor shall anyone be held guilty until so proven by a court ruling.

As is seen, international covenants and conventions Turkey is a party to and the Constitution of the

Republic of Turkey list rights and freedoms that are not allowed to be derogated from in times of war

and states of emergency. Nonetheless, Turkey hastily opted for suspending all international and

national obligations upon the declaration of the SoE without taking the time to assess whether such

restrictions were necessary or not.

Council of Europe Human Rights Commissioner Nils Muiznieks also offered significant analyses of

the SoE in Turkey. Commissioner Muiznieks published “Memorandum on the human rights

implications of the measures taken under the state of emergency in Turkey”

8

on 7 October 2016

following his visit to Turkey between 27 and 29 September 2016.

The commissioner noted that the sweeping measures taken on the basis of decree laws without

any court ruling were not limited to the public sector but also included the civil society, municipalities,

private schools, universities, medical establishments, legal professionals, media, business and

finance, as well as the family members of suspects. For the commissioner, it was therefore clear that

these measures created sweeping interferences with the human rights of a very large number of

persons. The commissioner underlined that far-reaching, discretionary powers exercised by the

administration via decree laws engendered a certain degree of arbitrariness and eroded rule of law,

yet protection of human rights was impossible without the rule of law. The commissioner criticized the

government for sustaining state of emergency although two and a half months had passed since the

coup attempt at the time of his memorandum and stated that the time had come to revert to ordinary

legislation as regards criminal and administrative procedures and safeguards. The commissioner

significantly emphasized that the Turkish authorities should immediately start repealing the

emergency decrees (para. 12). Commissioner Muiznieks reminded the readers of the following

principles as well (para. 13):

The Commissioner is convinced that it is in the interest of the Turkish authorities to conduct

this fight while fully upholding human rights, as well as general principles of law such as,

among others, presumption of innocence, individuality of criminal responsibility and

punishment, no punishment without law, non-retroactivity of criminal law, legal certainty,

right to defense and equality of arms. In the Commissioner’s view, the restoration of social

peace and confidence in democratic institutions that Turkish society direly needs in the

aftermath of the coup attempt can only be attained if all proceedings are conducted in a

fully transparent manner, adhering to these general principles of law and human rights

which are at the core of the Council of Europe.

8

https://rm.coe.int/ref/CommDH(2016)35

11

The commissioner also drew attention to the extension of the custody period to 30 days, drastic

restrictions on access to lawyers, as well as limitations on the confidentiality of the client-lawyer

relationship and indicated that Turkey had no functioning National Preventive Mechanism concerning

the allegations of torture and ill-treatment (para. 15). Further, the commissioner took note of the

information that the National Security Council had already designated FETÖ/PDY as a terrorist

organization in 2015, while noting that the conclusions of this body were not addressed to the public,

but to the council of ministers (para. 19). The commissioner pointed that there was no final judgment

rendered by the Turkish judiciary about this organization as well (para. 20). The commissioner,

therefore, urged the authorities to dispel these fears by communicating very clearly that mere

membership or contacts with a legally established and operating organization, even if it was affiliated

with the Fethullah Gülen movement, was not sufficient to establish criminal liability and to ensure that

charges for terrorism were not applied retroactively to actions which would have been legal before 15

July.

The Venice Commission’s “Opinion on Emergency Decree Laws Nos. 667-676 Adopted following

the Failed Coup of July 2016” published in December 2016 was adopted by the commission at its

109

th

Plenary Session. The opinion presented comments based mainly on 10 emergency decree laws

issued until December 2016. The Venice Commission also indicated in its opinion that state of

emergency powers should be used in limitation and measures against current threats should be taken

by means of ordinary legislation:

9

(…) The Government requested and received emergency powers from Parliament in July

2016 in connection with a specific public emergency, and should use those powers

accordingly. As underlined in the Rule of Law Checklist (with reference to further

international human rights standards), in the context of an emergency situation “strict limits

on the duration, circumstance and scope of such [emergency] powers [of the Government]

is therefore essential.” Other threats to the public order and safety should be dealt with by

means of ordinary legislation.

The Venice Commission recommended the government to try, to the maximum extent possible,

and whenever the danger might be averted otherwise, to take provisional individual measures during

the emergency regime, i.e. those which were of limited duration or might later be revoked or

amended.

Emergency Decree Laws and the Constitutional Court

Deputies from the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi -CHP) lodged an application

before the Constitutional Court in September 2016 to revoke and render issues of stay for emergency

decree laws nos. 668, 669, 670 and 671 on the grounds that they were in violation of the Preamble to

the Constitution as well as Articles 2, 6, 7, 8, 11, 91 and 121.

9

Para. 68: https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-

AD(2016)037-e

12

Nevertheless, the Constitutional Court rejected these applications lodged under Article 121 of the

Constitution on the grounds of lack of jurisdiction holding that it was not possible for the court to

undertake judicial review on the merits of the case in the light of the provision in the third sentence of

Article 148/1 of the Constitution which puts forth: “Presidential decrees issued during a state of

emergency or in time of war shall not be brought before the Constitutional Court alleging their

unconstitutionality as to form or substance” (Merits: 2016/166, Judgment: 2016/159, Judgement Date:

12 October 2016).

127 deputies also lodged an application before the Constitutional Court to revoke 25 laws which

had been issued originally as decree laws but had then been passed into laws after ratification by the

GNAT. The General Secretariat of the Constitutional Court held after its review of the case that the

laws in question were not unconstitutional in form. Applications for review on merits were finalized a

year later than the lifting of the SoE (July 2018) in 2019 and in 2020.

Altıparmak et. al. characterized these emergency decree laws, which transgressed the boundaries

drawn by both the Constitution and international law, as “atypical” and classified them in two groups:

10

a. Decree laws irrelevant to the SoE and regulated issues that required regulation by

ordinary legislation, therefore, bearing the qualification of transfer of legislative power.

b. Decree laws without general, abstract and non-personal rules with personalized punitive

qualification, therefore, bearing the qualification of transfer of judicial power.

Both groups of decree laws, which were issued by bypassing the legislative power of the GNAT

and later passed into laws, were made exempt from judicial review by means of the Constitutional

Court judgment, while effective protection of and guaranteeing fundamental rights and freedoms were

circumvented. Such state of affairs, in turn, created a situation that shrunk the field of both

fundamental rights and freedoms as well as that of human rights advocacy in Turkey.

The Constitutional Court rendered partial repeal judgments on various issues within the scope of

cases about laws that adopted emergency decree laws verbatim. Nonetheless, this issue will not be

tackled in detail as it would quite extend the scope of this study at hand.

Emergency Decree Laws and the European Court of Human Rights

Many an individual lodged direct applications before the ECtHR in the aftermath of the dismissals

through emergency decree laws as there were no available domestic remedies in Turkey because

there had been no legal and judicial remedies that individuals could use against measures taken

through emergency decree laws under Article 40 of the Constitution until decree law no. 685 was

issued.

The fact that the ECtHR declared all applications lodged on the issue before it in 2016 inadmissible

caused great disappointment. The first of these inadmissibility decisions was Mercan v. Turkey

(Application no: 56511/2016)

11

and the other was Zihni v. Turkey (Application No: 59061/2016).

12

10

Altıparmak, Kerem, Dinçer Demirkent andMurat Sevinç. “Atipik KHK’ler ve Daimi Hukuksuzluk:

Artık Yasaları İdare Mi İptal Edecek?” HRJP: 8 March 2018: https://www.ihop.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/2018/03/Atipik_OHAL_-KHKleri-1.pdf

13

The ECtHR suggested various means within domestic law that people could apply to in Turkey by

means of the Council of Europe. Indeed the Inquiry Commission on the State of Emergency

Measures

13

was established by authorities having taken the recommendations of the Council of

Europe and the Venice Commission into account (but moving away from these recommendations) via

decree law no. 685 on 23 January 2017.

The ECtHR found a violation in its judgment in the case of Hamit Pişkin, whose employment

contract was cancelled through decree law no. 677, on 15 December 2020. Following the cancellation

of his employment contract, Hamit Pişkin’s appeals were rejected by the Ankara Labor Court and

others. The Constitutional Court, too, declared his individual application inadmissible. No criminal

proceedings had been initiated into Hamit Pişkin upon which he lodged an application before the

ECtHR and the European court found a violation of Article 8 of the ECHR that regulates the right to

respect for private life in its judgment in the case of Pişkin v. Turkey (Application No: 33399/18) on 15

December 2020.

14

The Inquiry Commission on the State of Emergency Measures

Council of Europe General Secretariat’s recommendation for Turkey to establish a special

provisional board tasked with “inquiring public employees’ removal from their posts and individual

cases about other related measures” as a “temporary solution” in the face of the high number and

volume of applications lodged before the ECtHR was also supported by the Council of Europe Venice

Commission.

As a result of consultations with the Council of Europe General Secretariat, Decree law no. 685,

published in the Official Gazette of 23 January 2017, established an inquiry commission in order to

“carry out an assessment of and render a decision on applications about measures taken directly

through the provisions of decree laws, without any other administrative measure taken, on the

grounds of membership, belonging, acting in junction or contact with terrorist organizations or

structures, formations or groups decided to have been acting against the national security of the state

by the National Security Council within the scope of state of emergency.”

Procedures and principles about applications to be lodged before the Inquiry Commission on the

State of Emergency Measures and the modus operandi of the commission were designated by the

office of the prime minister and published in the Official Gazette of 12 July 2017 (No. 30122 -doublet).

The office of the prime minister announced that the applications would be received by the commission

starting on 17 July 2017. The commission stated that a total of 230 staff were assigned to serve on

the commission including 80 rapporteurs (judges, experts, inspectors) to assess and render a decision

on acts established directly through decree laws under the SoE including dismissals from public

service, cancellation of scholarship, annulment of ranks of retired security personnel and closure of

institutions and organizations.

Article 1/2 of decree law no. 685 set forth that the commission would be composed of 7 members,

3 of whom would be selected and assigned by the prime minister from among public officials, one

11

https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng-press#{%22itemid%22:[%22003-5549956-6992608%22]}

12

https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng-press#{%22itemid%22:[%22003-5571723-7028417%22]}

13

https://soe.tccb.gov.tr

14

https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng-press?i=003-6886711-9239474

14

member would be assigned by the minister of justice from among judges and prosecutors working for

the ministry of justice, one member would be selected by the interior minister from among personnel

holding the class of chief of civil administration and two members would be assigned by the Supreme

Board of Judges and Prosecutors from among rapporteur judges holding office in the Court of

Cassation and the Council of State.

When the chairperson of the commission was assigned as an undersecretary at the Ministry of

Justice and left the commission, he was not replaced and the commission resumed work with 6

members.

The commission only started working 6 months after 23 January 2017, when the decision to

establish such commission was rendered on 23 January 2017, and announced its initial decisions on

18 January 2018. According to information provided by the commission, a mere total of 16,060

acceptance decisions were rendered about 126,883 applications lodged before it as of 31 December

2021. The number of rejected applications was 104,643, while 6,080 decisions were pending before

the commission.

15

Provisional Article 1/3 of decree law no. 685 provided those who were dismissed from their posts

by authorized organs to go to courts within 60 days after the publication of the decree law. There is,

however, no publicly available data about the results and number of applications lodged within the

scope of this legal remedy that was particularly made available for dismissed judges and prosecutors

through decisions rendered by the Board of Judges and Prosecutors.

Appeals against Decisions Rendered by the Inquiry Commission on

the State of Emergency Measures

Ankara Administrative Courts were authorized to hear annulment cases to be brought against

decisions rendered by the Inquiry Commission on the State of Emergency Measures. According to an

announcement by the Board of Judges and Prosecutors, these courts would hear cases brought by

those dismissed from their posts and by closed-down organizations against rejection decisions

rendered by the commission.

Public employees, who were directly dismissed by the institutions they had worked for, on the other

hand, need to bring a case to an administrative court in due time while judges and prosecutors who

had been dismissed through decisions rendered by the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors

need to apply to the Council of State. The deadline for appeals vary between 30 to 45 days depending

on the institution. If the deadline is missed, reinstatement becomes legally out of the question. If

administrative courts deliver “rejection” rulings for reinstatement, applicants can appeal to the Council

of State. And if a similar ruling is delivered by the Council of State too, then the applicant has the right

to “individual application” before the Constitutional Court. Applicants, whose individual applications are

also rejected by the Constitutional Court, can subsequently bring their cases before the ECtHR.

15

https://soe.tccb.gov.tr

15

Implications of Decree Laws on the Civic Field

Decree law no. 667, which was issued on 23 July 2016 right after the declaration of the SoE,

signaled the measures to be taken during the SoE. These measures were designated on 22 July 2016

by the council of ministers that convened under the chairpersonship of the president as per Article 121

of the Constitution and Article 4 of Law No. 2935 on the State of Emergency dated 25 October 1983.

The measures prescribed by decree law no. 667 primarily targeted the Gülen sect that was said to

be the plotter of the failed coup attempt and incorporated the following measures in brief:

• Measures about closed-down institutions and organizations.

• Measures about members of the judiciary and those in the legal profession.

• Measures about public employees.

• Measures to be taken in pending investigations.

• Investigation and prosecution procedures.

• Cancellation of lease contracts about rights of easement and usufruct.

However, it was revealed in a couple of days that the government would turn the SoE into an

apparatus of repression and surveillance so as to cover everyone who could be regarded as

dissidents. Decree law no. 668, issued four days after decree law no. 667, expanded the scope of the

SoE and paved the way to introducing permanent amendments to the current legislation by way of

decree laws without being subjected to checks by the GNAT. Measures taken by the remaining 30

decree laws, issued after these two, fall outside the list of measures described by the Law on State of

Emergency dated 1983 since Articles 9 and 11 of Law No. 2935 on State of Emergency list the

measures to be taken within the scope of declaration of the SoE.

Although this law is referred to in decree laws, the prescribed measures transgress the borders

drawn by the Law on State of Emergency. For instance, measures like “removal of public employees

or judges from their posts” or “permanent liquidation of legal personalities” are not listed among the

measures to be taken in the declaration of SoE in the Law on State of Emergency dated 1983.

Regulations in Decree Laws Irrelevant to the Reasons for the Declaration of SoE

16

Measures to be taken during the SoE, permanent legislative regulations that had no causal

link to the reasons why SoE was declared were set forth by way of decree laws. These can

be listed as such:

1. A new university, “National Defense University,” was established through decree law no. 669.

2. An additional article was amended to Law No. 2547 on Higher Education through decree law

no. 674. Accordingly, the statuses of research assistants employed within the scope of the

Faculty Development Program were subjected to the provisions of Article 50(d) without any

other measure required.

3. Rectorate elections at universities were abolished through decree law no. 676. According to the

decree law, rectors are to be appointed to public universities by the president.

4. Law No. 6356 on Trade Unions and Collective Labor Agreements (Art. 63/1) was amended

through decree law no. 678. Accordingly, strike actions in inner-city public transport services for

metropolitan municipalities and banking services can now be postponed for 60 days.

5. The statement “military officers, contracted military officers, non-commissioned officers,

contracted non-commissioned officers, specialist gendarmes, specialist sergeants, contracted

sergeants and contracted privates serving at the Gendarmerie General Command and Coast

Guard Command” was added to the list of those who are not allowed to become members and

founders of public trade unions in Law No. 4688 on Public Employees’ Trade Unions and

Collective Labor Agreements through decree law no. 682.

6. A subparagraph was added to Article 4/1 of Law No. 6741 on the Establishment of Turkey

Wealth Fund Administration Incorporation and Amendments to Some Other Laws and the

scope of resources and financing for the Turkey Wealth Fund were expanded through decree

law no. 684.

7. There is no causal link between numerous regulations and the reasons why SoE was declared.

For instance, one cannot in good conscience find a correlation between using snow tires in

winter and terrorism, national security and, naturally, an attempted coup but it was the subject

of an emergency decree law (Article 2 of decree law no. 687, published in the Official Gazette of

9 February 2017).

8. Provisional articles were added to Law No. 4447 on Unemployment Insurance through decree

law no 687. The regulation for insurance premium support for each additional worker

employees would hire to be paid by the Unemployment Insurance Fund was introduced by this

decree law.

9. The Law on the Establishment of Radios and Televisions and Their Broadcasting Services was

amended through decree law 690. Marriage programs were banned.

10. Turkish Sugar Authority was closed down on 24 December 2017 through decree law no. 696.

11. A regulation on tenure for subcontracted public workers was done through decree law no. 696.

12. Decree laws nos. 674, 676, 680, 684, 694 and 696 introduced permanent amendments to the

Code of Criminal Procedure.

Decree laws both regulated the governmental (administrative) structure of the country and

issues of security and defense as well as introducing radical and permanent changes to

the fields of education, judiciary, social security.

16

Emergency decree laws should not introduce permanent structural changes to judicial bodies,

procedures and mechanisms, particularly in cases where such changes are not expressed in

unequivocal and clear terms in the Constitution.

17

As is declared in Article 2 of the Constitution of the

16

For amendments and additions introduced by decree laws to the legislation by way of “omnibus

bills,” see: When the State of Emergency Becomes the Norm: The Impact of Executive Decrees on

Turkish Legislation https://tr.boell.org/en/2018/03/15/when-state-emergency-becomes-norm

17

The above-mentioned “Opinion” by the Venice Commission also raised concerns about this

issue.

17

Republic of Turkey, the idea of “a democratic state governed by rule of law” also contains within itself

the principle of limited government. The Constitution of the Republic of Turkey allows governments to

derogate from or restrict human rights provisions and obligations only during the state of emergency

and on the condition that it is “categorically necessary” and it does not broaden this power to cover

legal rules to be implemented after the termination of the state of emergency. As has also been

indicated by the UN Human Rights Committee, “the predominant objective must be the restoration of

a state of normalcy where full respect for human rights can again be secured”

18

for a state party that

derogated from the ICCPR.

When one takes into account international and regional human rights mechanisms, provisions in

emergency decree laws should lose legal validity upon the termination of state of emergency when

structural (general) measures are in question. Thus, it is expected that no permanent amendments

are introduced to the legislation through decree laws during the state of emergency. In Turkey,

however, 32 decree laws went into effect incorporating more than 1,200 articles within the current

legislation during the two-year-long state of emergency and these decree laws introduced

amendments to more than 150 laws. These amendments were not checked by the GNAT and they

were introduced without creating an effective remedy in respect of their consequences.

19

It is observed that the majority of measures taken through decree laws issued within two years are

those that go beyond the duration of state of emergency with respect to their consequences. Most of

these measures have had important implications on the shrinking of civic space in Turkey. Indeed,

Article 2 of decree law no. 667 set forth that more than 2,000 private institutions would be closed

permanently. Within the framework of this decree law 35 healthcare institutions, 934 schools, 109

student dormitories, 104 foundations, 1,125 associations, 15 universities, and 19 workers’ trade

unions were closed down for good. Further, under Article 2/2 of this decree law, all assets of such

legal personalities were transferred to the state permanently and without charge.

The number of closed-down associations amounted to 1,607 as of 31 December 2017 as per

decree laws 667, 677, 679, 689 and 695, while closure decisions were lifted for 183 associations upon

objection which makes the figure go down to 1,424. The Inquiry Commission the State of Emergency

Measures, too, announced that it delivered acceptance decisions for 61 closed-down associations,

foundations, dormitories, television channels and newspapers as of 31 December 2021.

20

Closure

decisions for foundations were rendered through emergency decree laws and by a commission set up

within the General Directorate of Foundations. 168 foundations were closed down by means of decree

laws nos. 667, 689 and 695 along with the commission at the general directorate. Closure decisions

were then revoked for 23 of the closed-down foundations. The number of closed-down foundations

was 145 as of 31 December 2017.

Among the associations closed down through various decree laws were law organizations that

carried out effective works in the field of human rights (Progressive Lawyers’ Association, Lawyers for

18

CCPR, General Comment No. 29. <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/451555> para. 1.

19

For a full list of legislative regulations introduced through emergency decree laws, see Human

Rights Joint Platform’s “Updated Situation Report: State of Emergency in Turkey 21 July 2016-20

March 2018” <https://ihop.org.tr/en/2018/04/25/updated-situation-report-state-of-emergency-in-

turkey-21-july-2016-20-march-2018/> pp.49-53. And, the Confederation of Progressive Trade

Unions of Turkey (DİSK) offered a list of laws amended through decree laws in the appendix of its

report of 21 July 2018 entitled “OHAL’in İki Yılının ve Başkanlık Rejiminin Çalışma Hayatına

Etkileri: OHAL ve Başkanlık Emeğe Zararlıdır.” <http://arastirma.disk.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/2020/08/OHAL-2-Yıl-ve-Başkanlık-Rejimi-Yeni-Rapor-TASLAK-SON.pdf>

20

The Inquiry Commission on the State of Emergency Measures, “Activity Report: 2021”,

<https://soe.tccb.gov.tr/Docs/SOE_Report_2021.pdf> p. 24.

18

Freedom Association, Association for Human Rights Research) as well as those working in the fields

of rights of women and children. For example, closed-down women’s associations included Adıyaman

Women’s Life Association, Anka Women’s Research Association, Bursa Panayır Women’s Solidarity

Association, Ceren Women’s Association, Rainbow Women’s Association, KJA, Muş Women’s Roof

Association, Selis Women’s Association, and Van Women’s Association.

Agenda: Child! Association that carried out effective works for the rights of the child was among the

closed-down associations. Diyarbakır-based Sarmaşık Association that undertook activities based on

the fact that poverty was an obstacle to the protection and exercise of human rights, Van Women’s

Association (VAKAD), and Muş Women’s Roof Association had also carried out activities for the rights

of the child.

Social Workers’ Association’s Diyarbakır branch carrying out activities with children who migrated

from Diyarbakır’s Sur district and Happy Children Association in Ankara were also among the closed-

down associations.

The distribution of closed-down associations as per cities as of 31 December 2017 [Source: HRJP]

A total of 200 media outlets were also closed down during the 18-month SoE. Closure decisions

were revoked only for 25 of them, which makes the figure 175 as of 31 December 2017. Closure

decisions were rendered for 67 newspapers through decree laws nos. 668, 675, 677, 693 and 695

during the SoE, while these decisions were revoked for 17 of them through decree laws nos. 675 and

679. 6 news agencies, 18 periodicals and 29 publishing houses were also closed down in this period.

Further, 37 television channels were closed down through decree laws nos. 668 and 677 and through

decisions rendered by the Supreme Board of Radio and Television during the SoE. Closure decisions

were revoked only 4 of these television channels through decree law no. 675 and decisions by the

supreme board. Closure decisions were still pending for 33 television channels as of 31 December

2017.

Articles 3 and 4 of decree law no. 667 prescribe dismissal of judges and other public officials

through decisions rendered by related judicial organs or administrative bodies. Thus, for example,

Article 23 of Decree Law No. 671 abolished the Telecom Presidency and transferred its functions to

the Information and Communication Technologies Authority. Article 25 of this Decree Law established

a new procedure for authorizing wiretapping of telecommunications and obtaining access to electronic

data archives. It thus amended the current Article 60 of the Electronic Communications Law.

19

Article 16 of decree law no. 674 amended Law No. 5275 on the Enforcement of Sentences and

Security Measures granting the Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office the power to restrict “temporary

leave” for prisoners from penal institutions. The article reads:

Article 16 – The following sentence has been added to Article 92/1 on Law No. 5275 on the

Enforcement of Sentences and Security Measures dated 13/12/2004:

In the event that it is evaluated that prisoners incarcerated under offenses listed in Article

9/2 may endanger the order of the penitentiary institution and public security, that members

of terrorist organizations or other criminal organizations may provide opportunities for

activities and communication in accordance with the purposes of their respective

organizations and that there are security risks with regards to roads, penitentiary

institutions in which they are held, exam centers or schools, the Chief Public Prosecutor’s

Office shall be entitled to restrict their leave from such institutions.

Article 38 of this decree law, amending Law No. 5393 on Municipalities, put forth the procedure to

replace mayors who were removed from their offices for offenses of aiding and abetting terrorism.

Elected mayors were thus removed from office, a significant number of them were detained and

convicted. The administrative organs of municipalities of the Democratic Regions Party were

transferred to the local representatives of the central government.

Article 1 of decree law no. 676 introduced the rule that a maximum of three lawyers could be

present at court hearings held within the scope of prosecutions undertaken with regards to offenses

committed within the framework of organizational activity. Article 3, amending the provisions of the

Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP), prescribed that suspects taken into custody for such offenses

might not be allowed to confer with their defense attorneys for 24 hours. Article 6 amended the

provisions of Law No. 5275 and set forth the rules of restriction on conferences between detainees

and their lawyers.

The Venice Commission also criticized the issue of “trade union rights.” As is known, thousands of

wage-earners employed at closed-down institutions were not public officials and were employed as

workers entirely within the framework of private law. The termination of the receivables of these

workers under private law through a decree law goes well beyond the objective of the declaration of

the SoE and introduces a permanent amendment to labor law. Such changes cannot be done through

emergency decree laws. Fees and other workers’ receivables are incumbent on the employer both

under the Law of Obligations and Labor Law.

The state, which confiscated these institutions, cannot victimize workers employed at these

institutions. Upon the closure of these institutions, fees and severance pay receivables should be paid

to the workers. Workers cannot be held responsible and punished for offenses that might have been

committed by the owners of the closed-down institutions. Yet, the trial and punishment of workers

employed at these institutions for offenses they might have committed, if any, is another issue. Fees

and other receivables fall entirely under private law. Moreover, workers’ fees and similar receivables

cannot be terminated for offenses committed somewhere else than their workplaces. Workers

employed at closed-down institutions cannot be deprived of severance pay unless their employment

contracts are rightfully dissolved. Even in the event of rightful dissolution, workers’ fee receivables, if

20

any, have to paid. The contrary would mean forced labor and under the ECHR forced labor is

prohibited even under states of emergency.

21

4,770 members of trade unions affiliated with the Confederation of Public Employees’ Trade

Unions (KESK) were dismissed from their posts having their right to work violated. 4,283 of these

public employees were dismissed through emergency decree laws, while 487 were dismissed through

decisions rendered by the higher disciplinary boards at their respective institutions. While 358

individuals were reinstated through decisions by the Inquiry Commission on the State of Emergency

Measures as of December 2019, the commission rejected applications by 1,023 and inquiries were

pending for about 2,900 of KESK members.

The permanent closure of trade unions is both against the Constitution and the ICCPR as well as

the Revised European Social Charter and ILO conventions (No. 111 Discrimination -Employment and

Occupation).

The most concrete example of this proves to be dismissals by means of provisional Article 35 of

decree law no. 375 that provides for the continuation of dismissals. A total of 18 trade union members

-including 10 from SES, 4 from Eğitim-Sen, 3 from Haber-Sen and 1 from BES- have been dismissed

in this manner through decisions rendered by commissions set up at their respective ministries and

upon the consent of the related ministry. The common point of these individuals was that they were

either trade union executives or active members of their unions or took part in protests and activities

organized by their unions.

SES (Health and Social Services Workers’ Trade Union) was, too, subjected to repressive policies

faced by trade unions affiliated with KESK during the SoE. Because a large number of members of

trade unions affiliated with KESK were dismissed during the SoE, these dismissals led to resignations

from trade unions. It should be noted that SES lost blood in terms of its number of members. While

the number of SES members was 39,207 as of May 2016, this figure went down to 20,304 in May

2019. 796 SES members were also dismissed from their public posts during this period. While 162 of

these individuals were reinstated as of February 2020, applications by 92 were rejected. Inquiries are

pending for other dismissed members.

22

According to a report on union rights violations drafted by KESK and announced on 26 December

2019, 4,283 public employees were dismissed from their posts through emergency decree laws during

the SoE, while 487 public employees were dismissed by decisions rendered by higher disciplinary

boards at their respective institutions.

23

Although KESK and its affiliated trade unions have been

active since 1989 and had to relation to FETÖ/PDY, charged with the coup attempt, authorities took

advantage of the failed coup attempt and dismissed at least 4,770 members of trade unions affiliated

with KESK with no legal guarantees granted. Even this state of affairs on its own actually reveals the

fact that the current constitutional and legal guarantees in Turkey were suspended during the SoE and

the practice was changed in its entirety.

21

Aziz Çelik. “OHAL ve Sendikal Haklar.” BirGün. 29.07.2016. <https://www.birgun.net/haber/ohal-

ve-sendikal-haklar-122037>

22

Two reports on trade union rights and violations faced by union members can be consulted:

Confederation of Public Employees’ Trade Unions [KESK]. “15 Temmuz Darbe Girişimi Sonrası

Sivil Darbe Sürecinde Yaşanan Hak İhlalleri.” 19 January 2018. <http://www.kesk.org.tr/wp-

content/uploads/2018/01/19_01_2018-rapor.pdf>

Confederation of Progressive Workers’ Unions [DİSK]. “OHAL’in İki Yılının ve Başkanlık Rejiminin

Çalışma Hayatına Etkileri: OHAL ve Başkanlık Emeğe Zararlıdır.” 21 July 2018.

<http://arastirma.disk.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/OHAL-2-Y%C4%B1l-ve-

Ba%C5%9Fkanl%C4%B1k-Rejimi-Yeni-Rapor-TASLAK-SON.pdf>

23

https://kesk.org.tr/2019/12/26/sendikal-hak-ihlalleri-raporumuzu-acikladik/

21

The Global Rights Index 2020 issued by the International Trade Unions’ Confederation (ITUC)

listed Turkey among the 10 worst countries in the world for working people among 144 countries.

24

This report, too, revealed the serious setback in freedom of association, a part of trade union rights, in

Turkey.

The problem of substitution of criminal laws in Turkey has deteriorated particularly in the aftermath

of the declaration of SoE. Council of Europe Venice Commission’s “Opinion on the Measures

Provided in the Recent Emergency Decree Laws with respect to Freedom of the Media” (No.

872/2016) dated 13 March 2017 is quite important in that the opinion indicated that the fact that public

prosecutors charged journalists, rights defenders, trade unionists and activists under Article 314 or

220 of the TPC and Article 7 of the ATC on the grounds of the statements they made, demonstrations

they took part in and the articles they wrote was unlawful with no legality of offense sought and

ultimately led to very serious rights violations.

25

Such state of affairs is often observed in trade union

protests and activities as well.

The July 2020 report “A Perpetual Emergency: Attacks on Freedom of Assembly in Turkey and

Repercussions for Civil Society”

26

and the May 2021 report “Turkey’s Civil Society on the Line: A

Shrinking Space for Freedom of Association,”

27

both drafted by drafted by the Human Rights

Association (İHD) and the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders (OBS), revealed

that legislative regulations introduced during and after the SoE led to the shrinking of civic space,

perpetual attempts at intimidation repressed civil society actors while this state of affairs resulted in a

climate of fear.

Saturday Mothers’ 700

th

peaceful vigil, which has been held since 1995 in İstanbul’s Galatasaray

Square asking for the fates of their loved ones who had been subjected to enforced disappearances in

the 1980s and 1990s, was also banned by the Beyoğlu District Governor’s Office in line with the

state’s attempts to shrink the civic space. Since then, Saturday Mothers are not allowed to hold their

weekly sit-ins in Galatasaray Square that they had been doing so for decades without any problems

and they are only allowed to do so in a small street before İHD’s İstanbul branch.

24

https://www.ituc-csi.org/ituc-global-rights-index-2020?lang=en

25

https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2017)007-e

26

https://ihd.org.tr/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/20200728_FIDH-OMCTIHD_TurkeyReport.pdf

27

https://ihd.org.tr/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/OBS-İHD-TURKEY.pdf

22

Emergency Decree Laws and Repression of the Human

Rights Field

The principle of rule of law, right to a fair trial, right to property, ILO Termination of Employment

Convention (C 158), ban on discrimination in employment and occupation (ILO C 111), right to work,

right to education, freedom of association, freedom of movement, presumption of innocence, judicial

guarantees, academic freedom, right to liberty and security of person, right to defense, right to legal

counsel can be listed among the violated human rights within the scope of this study.

Emergency decree laws issued during the 2016-2018 SoE violated Articles 10, 11, 20, 23, 24, 25,

34, 35, 36, 40, 49, 50, 51, 53, 121, 125, 129, 130 of the Constitution; Articles 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14

of the ECHR; ILO Conventions Nos. 111 and 158; Article 7 of the UN International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as well as the Committee’s General Comment No. 18.

According to data collected by İHD, the balance sheet of SoE conditions, which started on 21 July

2016 and ended on 18 July 2018, is as follows:

Period of custody was extended to 30 days through decree law no. 667 that went into

effect on 23 July 2016; conferences with lawyers were banned for the first 5 days of

custody through decree law no. 668 that went into effect on 27 July. This practice was

maintained nonstop for 6 months.

Period of custody was cut back down to 14 days from the previous 30 through decree law

no. 682 that went into effect on 23 January 2017 while the ban on conferences with

lawyers was also cut back down to 1 day.

135,147 public employees were dismissed from public service through decree laws during

the SoE.

Works permits of 22,474 people, who had been working at closed-down private institutions

and most of who were teachers, were revoked.

A total of 4,395 judges and prosecutors were dismissed through mostly by decisions

rendered by the Board of Judges and Prosecutors, Constitutional Court rulings, and

through Supreme Military Council decisions for military judges and prosecutors.

48 healthcare institutions were closed down.

2,281 private educational institutions (schools, educational centers, boarding houses,

dormitories, etc.)

15 private universities were closed down, while a total of 3,041 of their tenured personnel

became unemployed.

Activities of 19 trade unions and confederations were terminated.

23

985 companies were confiscated and had trustees appointed during the SoE. 49,587

workers had been working at these companies.

201 media outlets were closed down during the SoE.

The report “A Perpetual Emergency: Attacks on Freedom of Assembly in Turkey and

Repercussions for Civil Society,” drafted by the Human Rights Association (İHD) and the Observatory

for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders (OBS), demonstrated the fact that all rights defenders,

particularly human rights defenders working in the Southeast, LGBTI+ rights defenders and women’s

rights defenders, faced gross repression; their activities were surveilled by the police everywhere;

almost none of their outdoor activities was allowed during the SoE. It was also observed that human

rights defenders were subjected to criminal investigations and prosecution due to virtually all their

activities in the public space.

Numerous journalists were detained during the SoE. When the SoE was lifted there were 172

journalists in prison. 1,607 associations and 168 foundations were also closed down during the SoE.

According to the official figures released by the Ministry of Justice, court cases had been brought

against 4,187 persons for insulting the president (TPC Art. 299) in 2016 while this figure went up to

6,033 persons in 2017. While 482 court cases were brought under TPC Article 301 that regulates

insulting Turkishness in 2016, this figure went up to 753 in 2017. Further, 17,322 persons faced

prosecution for allegedly making propaganda for an illegal organization in 2016 and this figure too

went up to 24,585 in 2017.

Although the SoE was lifted as of 18 July 2018, it was rendered permanent with all its

consequences when the 25-article Law No. 7145 on Amendments to Some Laws and Decree Laws,

which prescribed that important practices implemented during the SoE would stay in effect for at least

three more years, was ratified by the GNAT on 25 July 2018. Law No. 7145 that went into effect on 31

July 2018 upon the ratification of the president also attempted to fill in some gaps in which SoE

decree laws that rendered extraordinary practices of the regime proved insufficient to fill. The grounds

for the law indicated that these amendments were necessary as the 2-year-long SoE would not be

extended anymore and the following additional regulations were introduced:

Custody periods could be extended to a total of 12 days through 4-day extensions by a judge’s

ruling was regulated. The Constitution was clearly violated in this way since the period of custody can

only be extended to a maximum of 4 days even for collective offenses upon the request of the public

prosecutor and the ruling of the judge under Article 19 of the Constitution. Article 19 of the

Constitution prescribes that custody periods may be extended during a state of emergency or in time

of war. This amendment, thus, signifies that the SoE was de facto sustained.

Not only governors were granted the power to prohibit the entry and exit of specific persons into

and from specific places in a city for 15 days, they were also given the authority to declare curfews

and ban vehicles to go out in traffic at certain places and times without a time limit. It is without doubt

that personal liberty and security enshrined in Article 19 of the Constitution as well as the rights to

freedom of residence and movement enshrined in Article 23 of the Constitution are violated through

the use these powers. Alongside with these rights, many related rights would also be violated upon

the use of these powers.

Further, measures and practices that would lead to the violation of Article 34 of the Constitution

that designates the right to freedom of assembly was paved for by granting governors such new

powers as imposing restrictions and early dispersal of meetings and demonstrations.

24

The law designated that dismissal of persons from public office would continue by way of

commissions to be established at every public institution and body upon the consent of the related

minister. This was an attempt to maintain the SoE order in just the same way as emergency decree

laws by introducing such a concept as persons in “junction” with terrorist organizations and structures

and formations posing a threat to national security. It also set forth that passport cancellations of those

who had been and would be dismissed would continue. As for dismissed academics, it was regulated

that they would not be reinstated to their former universities even if a reinstatement decision was

rendered for them.

Numerous regulations that terminated procedural guarantees and the right to a fair trial were also

put in place, for instance, it was regulated that when the need to retake a person’s statement about

the same incident arose this procedure could be undertaken by the law enforcement upon a written

order by a public prosecutor and decisions on objections to detention and requests for release could

be rendered over the file.

Permanent SoE Law No. 7145 violated numerous rights. These include: 1. The right to liberty and

security of person, 2. Freedom of residence and movement, 3. Presumption of innocence, 4. Right to

a fair trial, 5. Principle of equality and prohibition of discrimination, 6. Freedom of thought and opinion,

7. Freedom of expression, 8. Freedom of association, 9. Respect for the privacy of private and family

life, 10. Academic freedom, 11. Right to work. The SoE was rendered permanent by means of the

above-mentioned and similar other articles that restricted rights and freedoms while expanding the

authority of the political power with no limits.

The number of unlawful arrests and detentions as well as imprisonment convictions rendered for

human rights defenders in finalized cases that utterly violated the right to a fair trial, which were all at

play even before the SoE, has also been on the rise.