213

ESSAY

STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE

Kevin Tobia,* Brian G. Slocum** & Victoria Nourse ***

How should judges decide which linguistic canons to apply in inter-

preting statutes? One important answer looks to the inside of the legisla-

tive process: Follow the canons that lawmakers contemplate. A dierent

answer, based on the “ordinary meaning” doctrine, looks to the outside:

Follow the canons that guide an ordinary person’s understanding of the

legal text. We oer a novel framework for empirically testing linguistic

canons “from the outside,” recruiting 4,500 people from the United States

and a sample of law students to evaluate hypothetical scenarios that

correspond to each canon’s triggering conditions. The empirical findings

provide evidence about which traditional canons “ordinary meaning”

actually supports.

This Essay’s theory and empirical study carry several further impli-

cations. First, linguistic canons are not a closed set. We discovered possi-

ble new canons that are not yet reflected as legal canons, including a

“nonbinary gender canon” and a “quantifier domain restriction

canon.” Second, we suggest a new understanding of the ordinary mean-

ing doctrine itself, as one focused on the ordinary interpretation of rules,

as opposed to the traditional focus on “ordinary language” generally.

Third, many of the canons reflect that ordinary people interpret rules

with an intuitive anti-literalism. This anti-literalism finding challenges

textualist assumptions about ordinary meaning. Most broadly, we hope

this Essay initiates a new research program in empirical legal inter-

pretation. If ordinary meaning is relevant to legal interpretation, inter-

preters should look to evidence of how ordinary people actually under-

* Associate Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center.

** Distinguished Professor of Law, University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law.

*** Ralph V. Whitworth Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. For

helpful comments, we thank Bernard Black, Bill Buzbee, Erin Carroll, Josh Chafetz,

Christoph Engel, Andreas Engert, William Eskridge, Ezra Friedman, Brian Galle, Neal

Goldfarb, Hanjo Hamann, Joe Kimble, Anita Krishnakumar, Tom Lee, Daniel Rodriguez,

Corrado Roversi, Sarath Sanga, Mike Seidman, Amy Semet, Josh Teitelbaum, Michele

Ubertone, and audiences at the Free University of Berlin Empirical Legal Studies Center,

the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Georgetown University Law

Center, Northwestern University Law School, the University of Chicago Law School, and the

University of Bologna. For outstanding editorial assistance, we thank Larisa Antonisse and

the sta of the Columbia Law Review. This empirical research was funded by the Swiss

National Science Foundation Spark Grant for “The Ordinary Meaning of Law,” CRSK-

1_190713.

214 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

stand legal rules. We see our experiments as a first step in that new

direction.

I

NTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 215

I. A FRAMEWORK FOR TESTING INTERPRETIVE PRINCIPLES ..................... 226

A. Testing How Canons Are Triggered ............................................ 226

1. Context and Interpretation .................................................... 228

2. The Categories of Interpretive Canons .................................. 229

B. Category One Canons ................................................................... 232

C. Category Two Canons ................................................................... 235

D. Empirical Study of Interpretive Canons ...................................... 239

1. Interpretive Canons as an Incomplete Set ............................. 239

2. Poorly Defined Triggers .......................................................... 241

3. Uncertain Categorization and Conflicting Canons ............... 243

II. EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF INTERPRETIVE CANONS .............................. 245

A. A Description of the Study ............................................................ 246

B. Testing Category One Canons ...................................................... 249

1. Gender Canons ....................................................................... 250

2. Number Canons ...................................................................... 252

3. Conjunctive and Disjunctive Canons ..................................... 252

4. Mandatory and Permissive Canons ........................................ 253

5. Oxford Comma ....................................................................... 254

6. Presumption of Nonexclusive “Include” ............................... 255

7. Series-Qualifier Canon and Rule of the Last Antecedent ..... 256

C. Testing Category Two Canons ...................................................... 257

1. Noscitur a Sociis ......................................................................... 258

2. Ejusdem Generis ........................................................................ 259

3. Expressio Unius Est Exclusio Alterius ......................................... 260

4. Quantifier Domain Restriction Canon ................................... 261

III. DO THE CANONS REFLECT ORDINARY MEANING? ............................... 262

A. Broader Empirical Findings ......................................................... 262

1. Overall Pattern of Canon Endorsement ................................ 262

2. Confidence Ratings ................................................................. 264

3. Relationships Among the Implicit Applications of Dierent

Canons ..................................................................................... 265

B. Extending the Study With a Law Student Sample ....................... 266

C. General Conclusions From the Experimental Studies ................ 270

IV. RETHINKING ORDINARY MEANING AND INTERPRETIVE CANONS ......... 274

A. Reframing Ordinary Meaning: The Meaning of Rules ............... 277

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 215

1. Empirical Research and the Significance of Rules ................ 278

2. The Ordinary Meaning of Rules ............................................. 279

B. The Interpretive Canons’ Anti-Literalism .................................... 281

1. Current Debates About Literalism in Statutory

Interpretation .......................................................................... 281

2. Interpretive Canons That Create Nonliteral Meanings ........ 286

3. Discovering New Canons That Create Nonliteral Meanings. 287

C. A New Law and Language Research Program ............................. 288

1. Discovering Hidden Canons: Are There More Canons? ....... 288

2. Ordinary Meaning and Demographics .................................. 290

3. Current and Future Empirical Testing of Interpretive

Canons ..................................................................................... 292

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................. 296

I

NTRODUCTION

“American courts have no intelligible, generally accepted, and con-

sistently applied theory of statutory interpretation.”

1

This Hart and Sacks

lament is frequently quoted but misleading.

2

Despite extensive and ongo-

ing debate about how to interpret statutes, most plausible theories share

one common principle: a commitment to “ordinary meaning.”

3

This Essay

focuses on statutory interpretation, but its theory and empirical analysis

may extend more broadly. “Ordinary meaning” plays a crucial role in in-

terpreting most legal texts: from contracts and wills, to treaties and the

U.S. Constitution.

4

Normatively, the doctrine often finds justification for

1. Henry M. Hart, Jr. & Albert M. Sacks, The Legal Process: Basic Problems in the

Making and Application of Law 1169 (William N. Eskridge, Jr. & Philip P. Frickey eds.,

1994).

2. See David S. Louk, The Audiences of Statutes, 105 Cornell L. Rev. 137, 150 (2019)

(“A common trope in discussions of statutory interpretation theory is that American judges

lack a principled method of interpreting statutes, something legal theorists and members

of the judiciary alike have long recognized.”).

3. See Brian G. Slocum, Ordinary Meaning: A Theory of the Most Fundamental

Principle of Legal Interpretation 1–3 (2015) [hereinafter Slocum, Ordinary Meaning]; see

also William N. Eskridge, Interpreting Law: A Primer on How to Read Statutes and the

Constitution 33–41 (2016) [hereinafter Eskridge, Interpreting Law]; Antonin Scalia &

Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts 33 (2012); Lawrence M.

Solan, The Language of Statutes: Laws and Their Interpretation 53 (2010).

4. See, e.g., Cal. Civ. Code § 1644 (2018) (“The words of a contract are to be

understood in their ordinary and popular sense . . . .”); Cal. Prob. Code § 21122 (2018)

(“The words of an instrument are to be given their ordinary and grammatical meaning

unless the intention to use them in another sense is clear and their intended meaning can

be ascertained.”); Curtis J. Mahoney, Note, Treaties as Contracts: Textualism, Contract

Theory, and the Interpretation of Treaties, 116 Yale L.J. 824, 829–32 (2007) (describing the

216 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

“ordinary” language principles based on notice, predictability, and the no-

tion that the public should be able to read, understand, and rely upon

legal texts.

5

Increasingly, the Supreme Court has emphasized that the interpretive

process begins by giving statutory language its ordinary meaning.

6

For

some, interpretation begins and ends with ordinary meaning. Modern tex-

tualists believe that ordinary meaning should significantly constrain inter-

pretation; other considerations enter only if ordinary meaning is indeter-

minate.

7

Purposivists agree that ordinary meaning is at least relevant to

interpretation,

8

alongside other criteria including legislative intent (typi-

cally ascertained via legislative history).

9

Few deny that ordinary meaning

is regularly deployed by all members of the current Supreme Court.

10

Con-

sider the Court’s recent landmark decision in Bostock v. Clayton County.

11

The Justices divided sharply, but all the opinions—both the majority and

two dissents—invoked “ordinary meaning” in determining whether the

term “sex” in Title VII’s antidiscrimination provision includes sexual

orientation and transgender discrimination.

12

Not surprisingly, cutting-

Supreme Court’s recent approach to treaty interpretation, which often focuses on the plain

meaning of terms in a treaty); Lawrence B. Solum, The Constraint Principle: Original

Meaning and Constitutional Practice 3 (Apr. 3, 2019), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2940215

[https://perma.cc/P7JR-9RDM] (unpublished manuscript) (“The dominant strain of con-

temporary originalism emphasizes the public meaning of the constitutional text . . . .”).

5. See William N. Eskridge Jr., Brian G. Slocum & Stefan Th. Gries, The Meaning of

Sex: Dynamic Words, Novel Applications, and Original Public Meaning, 119 Mich. L. Rev.

1503, 1516–17 (2021) [hereinafter Eskridge et al., The Meaning of Sex].

6. See, e.g., Bostock v. Clayton County, 140 S. Ct. 1731, 1738 (2020) (“This court

normally interprets a statute in accord with the ordinary public meaning of its terms . . . .”);

Food Mktg. Inst. v. Argus Leader Media, 139 S. Ct. 2356, 2364 (2019) (“In statutory

interpretation disputes, a court’s proper starting point lies in a careful examination of

the ordinary meaning and structure of the law itself.”).

7. See, e.g., Victoria Nourse, Textualism 3.0: Statutory Interpretation After Justice

Scalia, 70 Ala. L. Rev. 667, 669 (2019) (acknowledging but questioning the premise that

ordinary meaning constrains as between results in a case).

8. See, e.g., Eskridge, Interpreting Law, supra note 3, at 35 (“There are excellent

reasons for the primacy of the ordinary meaning rule.”).

9. See Robert A. Katzmann, Judging Statutes 31–35 (2014) (explaining the

purposivist approach to statutory interpretation).

10. As Justice Elena Kagan famously declared of the Court, “We’re all textualists now.”

Harvard Law School, The Scalia Lecture: A Dialogue with Justice Kagan on the Reading of

Statutes, YouTube, at 08:29 (Nov. 25, 2015), https://youtu.be/dpEtszFT0Tg (on file with

the Columbia Law Review). This statement depends upon an essential ambiguity: whether

one begins or ends with the text.

11. 140 S. Ct. 1731.

12. Id. at 1750 (Gorsuch, J.) (“[T]he law’s ordinary meaning at the time of enactment

usually governs . . . .”); id. at 1767 (Alito, J., dissenting) (“The ordinary meaning of discrim-

ination because of ‘sex’ was discrimination because of a person’s biological sex, not sexual

orientation or gender identity.”); id. at 1825 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) (“[C]ourts must

follow ordinary meaning, not literal meaning.”).

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 217

edge statutory interpretation theory has turned its focus on “ordinary

meaning.”

13

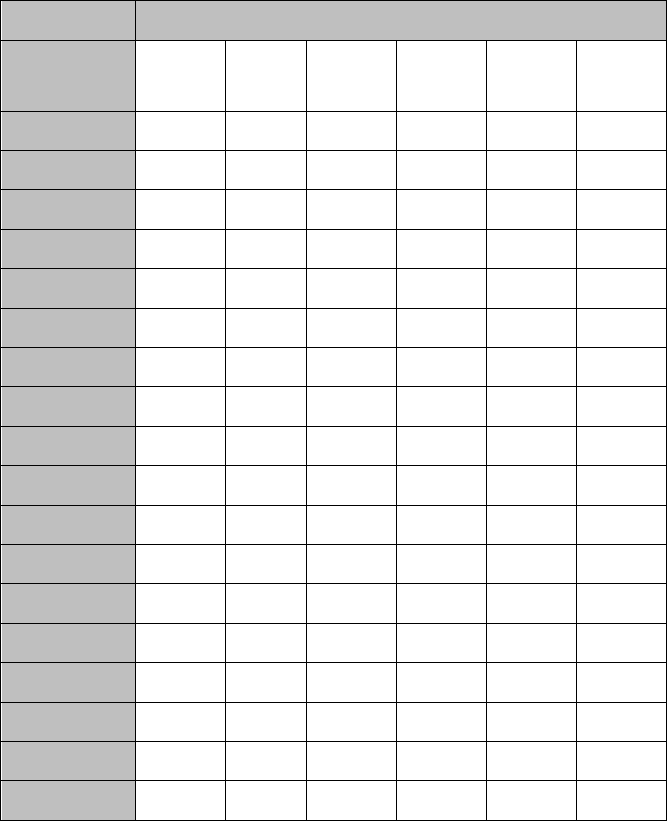

In fact, “ordinary meaning” is likely to grow in importance. Figure 1

reflects citations to “ordinary meaning,” “plain meaning,” and “legislative

history” across six million U.S. cases in Harvard Law School’s Caselaw Ac-

cess Project. Over the past fifty years, citation to “ordinary meaning” has

tripled. By way of comparison, citation to “legislative history” has halved

from its peak.

F

IGURE

1.

U.S.

C

ASE

L

AW

C

ITATIONS TO

O

RDINARY

M

EANING

,

P

LAIN

M

EANING

,

AND

L

EGISLATIVE

H

ISTORY

14

These patterns provide a rough impression of interpretive trends.

More robust empirical work supports the same conclusion, particularly in

high-profile Supreme Court cases. A recent study of the Supreme Court’s

use of interpretive tools found that between 2005 and 2017, the Roberts

Court relied on “text” and “plain meaning” in 41% of all opinions and

50% of majority opinions.

15

The Court relied on text more than intent,

13. E.g., Tara Leigh Grove, Which Textualism?, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 265 (2020); Anita S.

Krishnakumar, MetaRules for Ordinary Meaning, 134 Harv. L. Rev. Forum 167 (2021)

[hereinafter Krishnakumar, MetaRules]; Thomas R. Lee & Stephen C. Mouritsen, Judging

Ordinary Meaning, 127 Yale L.J. 788 (2018); James A. Macleod, Finding Original Public

Meaning, 56 Ga. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2021), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3729005 [https://

perma.cc/8DCR-EFK6] [hereinafter Macleod, Finding Original Public Meaning]; Slocum,

Ordinary Meaning, supra note 3; Lawrence M. Solan & Tammy Gales, Finding Ordinary

Meaning in Law: The Judge, the Dictionary, or the Corpus?, 1 Int’l J. Legal Discourse 253

(2016); Kevin P. Tobia, Testing Ordinary Meaning, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 726 (2020)

[hereinafter Tobia, Testing Ordinary Meaning]; Kevin Tobia & John Mikhail, Two Types of

Empirical Textualism, 86 Brook. L. Rev. 461 (2021).

14. Caselaw Access Project, Harv. L. Sch. (2018) (retrieved Nov. 2, 2021).

15. Anita S. Krishnakumar, Cracking the Whole Code Rule, 96 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 76, 97

(2021).

218 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

purpose, or legislative history.

16

The Court has recently gained three new

textualists, as lower federal courts welcome a new cohort of exceptionally

young judges, similarly committed to textualism.

17

So how do courts determine a statute’s “ordinary meaning”? Some-

times the debate centers on the meaning of individual terms,

18

with judges

increasingly relying on tools like dictionaries.

19

Dictionaries provide evi-

dence about how individual terms are used in nonlegal communications.

20

But statutes contain complex expressions, with terms embedded in specific

contexts.

21

This complexity raises dicult questions about the relationship

between the conventional meaning of a term and its context.

Often, contextual patterns are so frequently repeated that they are

taken to trigger regular assumptions about “ordinary meaning.” Take the

well-known case of McBoyle v. United States, which required the Court to

determine whether an airplane is a “vehicle” under the National Motor

Vehicle Theft Act.

22

This Act punishes those who knowingly transport a

stolen “automobile, automobile truck, automobile wagon, motor cycle, or

16. See id.

17. See John Gramlich, How Trump Compares With Other Recent Presidents in

Appointing Federal Judges, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Jan. 13, 2021), https://www.pewresearch.

org/fact-tank/2021/01/13/how-trump-compares-with-other-recent-presidents-in-

appointing-federal-judges/ [https://perma.cc/R7L9-4D8P]; Moiz Syed, Charting the Long-

Term Impact of Trump’s Judicial Appointments, ProPublica (Oct. 30, 2020), https://

projects.propublica.org/trump-young-judges/ [https://perma.cc/W3AX-YRR3] (explaining

that President Trump appointed a record number of federal judges and that his appointees

to the Supreme Court and appeals courts are younger than appointees by presidents going

back to President Nixon by about four years on average); see also Jason Zengerle, How the

Trump Administration Is Remaking the Courts, N.Y. Times Mag. (Aug. 22, 2018), https://

www.nytimes.com/2018/08/22/magazine/trump-remaking-courts-judiciary.html (on file

with the Columbia Law Review) (noting President Trump’s “commit[ment] to . . .

nominating and appointing judges that are committed originalists and textualists” (internal

quotation marks omitted) (quoting Donald McGahn, White House counsel to President

Trump)).

18. See Victoria Nourse, Misreading Law, Misreading Democracy 18 (2016)

[hereinafter Nourse, Misreading Law] (arguing that there are almost always two apparent

meanings for key terms).

19. See, e.g., James J. Brudney & Lawrence Baum, Oasis or Mirage: The Supreme

Court’s Thirst for Dictionaries in the Rehnquist and Roberts Eras, 55 Wm. & Mary L. Rev.

483, 493 (2013) (arguing that dictionaries have been “overused and abused by the Court”).

20. Although dictionaries can provide general information about word meanings, the

judicial practice of relying on dictionaries to define statutory terms is fraught with problems.

See Ellen P. Aprill, The Law of the Word: Dictionary Shopping in the Supreme Court, 30

Ariz. St. L.J. 275, 297–30 (1998) (stating that the level of “linguistic analysis” performed by

courts rarely rises above “dictionary shopping”).

21. See generally Peter M. Tiersma, Some Myths About Legal Language, 2 Law,

Culture & Humanities 29 (2005) [hereinafter Tiersma, Myths] (explaining that the way

legal texts are drafted adds to their complexity).

22. 283 U.S. 25, 25–26 (1931).

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 219

any other self-propelled vehicle not designed for running on rails.”

23

Jus-

tice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing for the Court, found that the stat-

ute did not apply to an aircraft: An airplane is not a vehicle.

24

If one focuses on the term “vehicle,” the Court’s conclusion might

seem puzzling. Isn’t an airplane a vehicle?

25

But any puzzlement lessens

when we consider the ordinary meaning of “vehicle” in context. The

general words, “any other . . . vehicle,” come after a long list of more spe-

cific terms: automobile, automobile truck, automobile wagon, and motor-

cycle.

26

Perhaps, based on this context, an ordinary reader would under-

stand the statutory rule to be more specific: “Vehicle” refers to

automobiles, motorcycles, and similar entities, like buses, that are

designed for traveling on land. But vehicles of a very dierent nature (e.g.,

canoes or airplanes) are not “vehicles” in this context.

27

“Vehicle” thus

communicates something dierent when it is placed at the end of a list in

a rule. The ejusdem generis canon captures this intuition: When general

words follow an enumerated class of things, the general words should be

construed to apply to things of the same general nature.

28

Thus, a statute

referring just to “vehicles” may include airplanes as vehicles, but a statute

that includes “vehicles” at the end of a list of specific examples might con-

vey a dierent, narrower meaning.

Judges rely heavily on dozens of interpretive principles like ejusdem

generis.

29

These principles are so long standing and frequently applied that

23. See id.

24. See id. at 26.

25. Some have questioned whether the ordinary meaning of “vehicle” includes air-

planes. See Lee & Mouritsen, supra note 13, at 840. Nevertheless, even if some doubt exists,

the specific context in McBoyle significantly bolstered the Court’s claim that an airplane was

not a vehicle. See McBoyle, 283 U.S. at 26.

26. McBoyle, 283 U.S. at 26.

27. For Justice Brett Kavanaugh, even the question whether a baby stroller is a vehicle

in this context may be dicult. See Bostock v. Clayton County, 140 S. Ct. 1731, 1825 (2020)

(Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) (asserting that a “statutory ban on ‘vehicles in the park’ would

literally encompass a baby stroller” but that “the word ‘vehicle,’ in its ordinary meaning,

does not encompass baby strollers”).

28. See Larry Alexander, Bad Beginnings, 145 U. Pa. L. Rev. 57, 65 (1996) (“When

general words follow specific words in a statute, the general words are to be given a ‘sense

analogous to that of the particular words.’” (quoting Scott Brewer, Exemplary Reasoning:

Semantics, Pragmatics, and the Rational Force of Legal Argument by Analogy, 109 Harv. L.

Rev. 923, 937 (1996))); see also infra section I.C.

29. See William N. Eskridge, Jr., Philip P. Frickey, Elizabeth Garrett & James J.

Brudney, Cases and Materials on Legislation and Regulation: Statutes and the Creation of

Public Policy 1195–215 (5th ed. 2014) [hereinafter Eskridge et al., Cases and Materials

2014] (identifying at least 161 dierent interpretive canons).

220 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

they are referred to as “canons” of interpretation.

30

In fact, judges cite in-

terpretive canons more frequently now than in the past.

31

Yet, some courts

and commentators also criticize canons as unjustified.

32

Debates about canons’ justification center on two very dierent em-

pirical questions. One concerns whether legislative authors contemplate

the canon when drafting.

33

The other concerns whether the canon reflects

how ordinary people reading the statute would understand the language.

34

William Eskridge and Victoria Nourse have described these justifications

as grounded in the “production” versus the “consumer” economies of

statutory interpretation.

35

The production economy emphasizes the stat-

ute’s authors; the consumer economy emphasizes its readers.

36

The empirical claim that canons reflect the meanings of the statute’s

producers or authors motivated Abbe Gluck and Lisa Bressman’s seminal

work: Statutory Interpretation from the Inside.

37

In 2013, Gluck and Bressman

published a survey of 137 congressional staers from both chambers of

30. See id. at 1195.

31. See Anita S. Krishnakumar & Victoria F. Nourse, The Canon Wars, 97 Tex. L. Rev.

163, 167 (2018) (arguing that recent Supreme Court cases have focused extensively on the

canons of construction); Nina A. Mendelson, Change, Creation, and Unpredictability in

Statutory Interpretation: Interpretive Canon Use in the Roberts Court’s First Decade, 117

Mich. L. Rev. 71, 73 (2018) (“The lion’s share of Roberts Court majority opinions engages

at least one interpretive canon in resolving a question of statutory meaning.”).

32. See, e.g., Jesse M. Cross, When Courts Should Ignore Statutory Text, 26 Geo.

Mason L. Rev. 453, 459–60 (2018) (arguing that many canons of construction must be

modified or discarded because they are inaccurate).

33. See, e.g., Abbe R. Gluck & Lisa Schultz Bressman, Statutory Interpretation From

the Inside—An Empirical Study of Congressional Drafting, Delegation, and the Canons:

Part I, 65 Stan. L. Rev. 901, 906–07 (2013) [hereinafter Gluck & Bressman, Statutory

Interpretation Part I] (surveying congressional sta and finding that many either ignore or

reject certain canons).

34. Cf. William N. Eskridge Jr. & Victoria F. Nourse, Textual Gerrymandering: The

Eclipse of Republican Government in an Era of Statutory Populism, N.Y.U. L. Rev.

(forthcoming 2021) (manuscript at 4), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3809925 [https://

perma.cc/SE3M-CGP4] (noting some scholars’ concern that canons may be manipulated

to “create an arbitrary façade of plain meaning”). These explanations of the justifications

are slightly oversimplified. In each case, it is possible that a canon might be justified even if

the authors or audience could not themselves name the canon. For example, even if

legislative drafters are unfamiliar with the term “ejusdem generis,” it might be that applying

the rule nevertheless helpfully captures features of intended meaning. Similarly, most non-

lawyers would be unfamiliar with the term “ejusdem generis.” But it might be that the rule

nevertheless helps explain how ordinary people understand statutory language. In each

case, the key empirical question is about whether applying the canon brings interpreters

closer to meaning—intended or ordinary.

35. See id. at 2.

36. See id.

37. Gluck & Bressman, Statutory Interpretation Part I, supra note 33, at 905.

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 221

Congress on topics relating to statutory interpretation, including the staf-

fers’ knowledge and use of interpretive canons.

38

The survey, designed to

explore the role the realities of legislative drafting should play in the the-

ories and doctrines of statutory interpretation, revealed that there are

some canons the drafters know and use, some the drafters reject in favor

of other considerations, and some the drafters do not know as rules but

that seem to accurately reflect how Congress drafts.

39

Critics of Gluck and Bressman, however, maintain that “insiders’”

views on canons are not the relevant measure; such studies simply seek to

unearth an unfathomable congressional mind.

40

Rather than focus on the

producers of statutes, they urge focus on the consumers of statutes, the

ordinary reader. As Justice Samuel Alito just urged in the 2020–2021 Term,

canons are only useful if they reflect ordinary meaning.

41

That is, a canon’s

validity comes from ordinary people’s linguistic practices. The key ques-

tion would be: Is the canon a guide to how ordinary people would under-

stand the language in the statute? For example, when considering the stat-

ute at issue in McBoyle, would an ordinary person implicitly understand

that the scope of “any other . . . vehicle” is partly restricted—meaning not

literally any vehicle but only those suciently similar to the enumerated

38. See Lisa Schultz Bressman & Abbe R. Gluck, Statutory Interpretation From the

Inside—An Empirical Study of Congressional Drafting, Delegation, and the Canons: Part II,

66 Stan. L. Rev. 725, 728 (2014) [hereinafter Bressman & Gluck, Statutory Interpretation

Part II]; Gluck & Bressman, Statutory Interpretation Part I, supra note 33, at 905–06. Judges

have cited the Gluck and Bressman studies for the proposition that canons should not be

used in interpretation since they are not deployed by drafters. See, e.g., James v. Heinrich,

960 N.W.2d. 350, 380 (Wis. 2021) (Dallett, J., dissenting). Our study focuses on a dierent

population, ordinary readers, and suggests that ordinary readers understand law

consistently with many (but not all) linguistic canons.

39. See Bressman & Gluck, Statutory Interpretation Part II, supra note 38, at 732–33.

In 2002, Victoria Nourse and Jane Schacter published the first case study of legislative

drafting by Senate Judiciary Committee staers, assuming that, of all congressional staers,

these were the “most likely to be schooled in the rules of clarity, canons of construction, and

statutory interpretation.” Victoria F. Nourse & Jane S. Schacter, The Politics of Legislative

Drafting: A Congressional Case Study, 77 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 575, 582 (2002). The authors found

that canons were not a “central part” of the drafting process. Id. at 614. As one staer

explained, “[W]e are conscious of . . . what a court will do, but not at the level of expressio

unius.” Id. at 601. In future work, we hope to ask congressional staers the same questions

we have posed to ordinary readers in this study.

40. John F. Manning, Without the Pretense of Legislative Intent, 130 Harv. L. Rev.

2397, 2430–31 (2017); see also Amy Coney Barrett, Congressional Insiders and Outsiders,

84 U. Chi. L. Rev. 2193, 2200–01 (2017) (arguing that Gluck and Bressman take the position

of the “hypothetical insider who knows how Congress works” whereas the textualist insists

that the “relevant user of language be ordinary”); John F. Manning, Inside Congress’s Mind,

115 Colum. L. Rev. 1911, 1941 (2015) [hereinafter Manning, Inside Congress’s Mind]

(arguing that the Gluck and Bressman studies support skepticism about looking for answers

in Congress’s mind).

41. See Facebook, Inc. v. Duguid, 141 S. Ct. 1163, 1175 (2021) (Alito, J., concurring).

For the theoretical importance of ordinary meaning, see Slocum, Ordinary Meaning, supra

note 3, at 1–3.

222 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

ones? If yes, this would support an empirically based justification for

ejusdem generis, grounded not in legislative intent or practice but in ordi-

nary meaning.

42

The Supreme Court increasingly relies on text and ordinary meaning

to resolve interpretive disputes, as do lower courts.

43

This calls for a com-

plement to Gluck and Bressman’s groundbreaking empirical work, namely

a new analysis of statutory interpretation from the outside. Recently, Chief

Justice John Roberts alluded to this intriguing possibility in oral argument:

[If] our objective is to settle upon the most natural meaning of

the statutory language to an ordinary speaker of English . . . the

most probably useful way of settling all these questions would be

to take a poll of 100 ordinary . . . speakers of English and ask

them what [the statute] means, right?

44

Such an approach was once considered beyond legal academics’ ca-

pacity,

45

but no more. There is a rich and growing literature in psychology,

linguistics, and cognitive science concerning people’s understanding of

language.

46

In law, the new field of “experimental jurisprudence” has

already demonstrated that scholars can conduct experiments to better

understand the ordinary cognition of law.

47

Thus far, those studies have

42. It would also suggest that “any vehicle” does not always mean literally any vehicle.

We propose a new ordinary meaning canon, the “quantifier domain restriction canon,” that

reflects this possibility. See infra section I.C.

43. See supra notes 6–17 and accompanying text (noting courts’ increasing reliance

on text and ordinary meaning).

44. Transcript of Oral Argument at 51–52, Facebook, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1163 (No. 19-511),

https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/2020/19-

511_l537.pdf [https://perma.cc/XEP7-QBE5].

45. See Adrian Vermeule, Interpretation, Empiricism, and the Closure Problem, 66 U.

Chi. L. Rev. 698, 701 (1999) (“Many of the empirical questions relevant to the choice of

interpretive doctrines are . . . unanswerable, at least at an acceptable level of cost or within

a useful period of time.”).

46. See, e.g., Dirk Geeraerts, Theories of Lexical Semantics 230 (2010) (“[N]ew word

senses emerge in the context of actual language use.”).

47. The field builds on work in experimental philosophy. See, e.g., Joshua Knobe &

Shaun Nichols, An Experimental Philosophy Manifesto, in Experimental Philosophy 3

(Joshua Knobe & Shaun Nichols eds., 2008); Stephen Stich & Kevin P. Tobia, Experimental

Philosophy and the Philosophical Tradition, in A Companion to Experimental Philosophy

5 (Justin Sytsma & Wesley Buckwalter eds., 2016). For an empirical study assessing the

replicability of experimental philosophy studies, see Florian Cova, Brent Strickland, Angela

Abatista, Aurélien Allard, James Andow, Mario Attie, James Beebe, Renatas Berniūnas,

Jordane Boudesseul, Matteo Colombo, Fiery Cushman, Rodrigo Diaz, Noah N’Djaye,

Nikolai van Dongen, Vilius Dranseika, Brian D. Earp, Antonio Gaitán Torres, Ivar

Hannikainen, José V. Hernández-Conde, Wenjia Hu, François Jaquet, Kareem Khalifa,

Hanna Kim, Markus Kneer, Joshua Knobe, Miklos Kurthy, Anthony Lantian, Shen-yi Liao,

Edouard Machery, Tania Moerenhout, Christian Mott, Mark Phelan, Jonathan Phillips,

Navin Rambharose, Kevin Reuter, Felipe Romero, Paulo Sousa, Jan Sprenger, Emile

Thalabard, Kevin Tobia, Hugo Viciana, Daniel Wilkenfeld & Xiang Zhou, Estimating the

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 223

focused on central legal concepts, such as causation,

48

consent,

49

intent,

50

reasonableness,

51

law itself,

52

and many others.

53

Other studies have

focused on how ordinary people understand word meanings or how they

would resolve specific interpretive disputes.

54

But, as the McBoyle case

suggests, the ordinary meaning of statutes does not arise solely from

individual word meanings, and commonly occurring types of context and

inferences are also important topics of study. Statutes are written in

sentences, which must be interpreted in light of relevant context in order

to understand the rules expressed. An important legal-interpretive

question concerns how ordinary people tend to understand this kind of

language.

This Essay takes a first step in this new direction: the empirical study

of interpretive canons from an ordinary meaning perspective. Surveying

ordinary people might seem straightforward, but designing useful experi-

ments requires very careful theory. In Part I, we develop a framework for

empirically testing interpretive canons. We describe the three relevant el-

ements of interpretive canons (triggering, application, and cancellation)

Reproducibility of Experimental Philosophy, 12 Rev. Phil. & Psych. 9 (2021). See generally

The Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Jurisprudence (Kevin Tobia ed., forthcoming).

48. See Joshua Knobe & Scott Shapiro, Proximate Cause Explained: An Essay in

Experimental Jurisprudence, 88 U. Chi. L. Rev. 165 (2021); James A. Macleod, Ordinary

Causation: A Study in Experimental Statutory Interpretation, 94 Ind. L.J. 957 (2019).

49. See Roseanna Sommers, Commonsense Consent, 129 Yale L.J. 2232 (2020).

50. See Markus Kneer & Sacha Bourgeois-Gironde, Mens Rea Ascription, Expertise

and Outcome Eects: Professional Judges Surveyed, 169 Cognition 139 (2017); Sydney

Levine, John Mikhail & Alan M. Leslie, Presumed Innocent? How Tacit Assumptions of

Intentional Structure Shape Moral Judgment, 147 J. Experimental Psych.: Gen. 1728 (2018).

51. See Christopher Brett Jaeger, The Empirical Reasonable Person, 72 Ala. L. Rev.

887 (2021); Kevin P. Tobia, How People Judge What Is Reasonable, 70 Ala. L. Rev. 293

(2018) [hereinafter Tobia, How People Judge What Is Reasonable].

52. E.g., Brian Flanagan & Ivar R. Hannikainen, The Folk Concept of Law: Law Is

Intrinsically Moral, Australasian J. Phil. (2020); Ivar R. Hannikainen, Kevin P. Tobia,

Guilherme da F. C. F. de Almeida, Ra Donelson, Vilius Dranseika, Markus Kneer, Niek

Strohmaier, Piotr Bystranowski, Kristina Dolinina, Bartosz Janik, Sothie Keo, Eglė

Lauraitytė, Alice Liefgreen, Maciej Próchnicki, Alejandro Rosas & Noel Struchiner, Are

There Cross-Cultural Legal Principles? Modal Reasoning Uncovers Procedural Constraints

on Law, Cognitive Sci., Aug. 2021, at 1.

53. Kevin P. Tobia, Law and the Cognitive Science of Ordinary Concepts, in Law and

Mind: A Survey of Law and the Cognitive Sciences 86 (2021) (examining the relationship

between folk psychology (laypeople’s commonsense understandings) and the law); Kevin P.

Tobia, Experimental Jurisprudence, 89 U. Chi. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2022),

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3680107 [https://perma.cc/XJW9-SYJV] [hereinafter Tobia,

Experimental Jurisprudence] (debunking myths about experimental jurisprudence and

arguing that it is a form of traditional jurisprudence rather than a social scientific

replacement of jurisprudence).

54. See, e.g., Omri Ben-Shahar & Lior Jacob Strahilevitz, Interpreting Contracts via

Surveys and Experiments, 92 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1753, 1765 (2017); Shlomo Klapper, Soren

Schmidt & Tor Tarantola, Ordinary Meaning From Ordinary People (unpublished

manuscript) (on file with the Columbia Law Review).

224 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

and explain that the triggering element is our focus. A canon’s “trigger”

is the linguistic condition making the canon applicable, such as a comma

or a certain word or type of phrase.

55

This focus, we argue, is necessary to

determine whether ordinary people implicitly apply an interpretive canon

in accordance with its definition. In addition, focusing on canon triggers

has the potential to help resolve longstanding interpretive problems that

have plagued courts, such as poorly defined canons and conflicts between

canons.

In Parts II and III, we implement our framework through a survey of

4,500 demographically representative people recruited from the United

States, as well as a sample of over one-hundred first-year U.S. law students.

The survey tested over a dozen interpretive canons.

56

Our study provides

crucial evidence for textualists and others committed to ordinary mean-

ing. Currently, judges and scholars assume that certain canons reflect or-

dinary meaning on the basis of intuition or tradition. The survey directly

addresses this fundamental empirical question about ordinary meaning:

Which (if any) of the interpretive canons actually reflect how ordinary peo-

ple understand language?

57

Part IV considers three broader implications of our work for statutory

interpretation theory. First, the results support a new approach toward “or-

dinary meaning” itself. There is great debate concerning whether that doc-

trine refers to the ordinary meaning of (1) “legal language” or (2) “ordi-

nary language.” We find that people intuitively apply canons across both

legal and ordinary rules. That is, surprisingly little turns on whether people

understand language as ordinary or legal, so long as it is language in a rule.

We suggest that the legal/ordinary language dichotomy obscures a more

fundamental aspect of the ordinary meaning doctrine: It is a doctrine

about ordinary understanding of language in rules. The canons do not nec-

essarily apply wherever there is “ordinary language” or “legal language”;

rather, they apply to interpretation of rules. A judge who fails to appreciate

the significance of “rule-like” contextual features may misinterpret

55. See infra section I.A.

56. The canons tested include what we term “Category One” canons, which have

relatively straightforward triggering conditions, as well as “Category Two” canons, which

have more complex triggering conditions. For a list of the canons and their definitions, see

infra Part II.

57. The survey posed hypothetical scenarios, corresponding to each canon’s triggering

conditions, to determine whether ordinary people implicitly invoke the canons when

interpreting both legal and nonlegal rules. To preview our findings: Many existing

interpretive canons reflect how ordinary people understand rules, but some popular canons

do not. For instance, ordinary people interpret rules in ways that correspond with various

longstanding canons such as ejusdem generis and noscitur a sociis but not in accordance with

the popular but frequently criticized canon expressio unius est exclusio alterius. In addition,

ordinary people implicitly resolve the conflict between the series-qualifier canon and the

rule of the last antecedent by interpreting modifiers consistently with the series-qualifier

canon.

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 225

ordinary meaning from “the outside.” For example, dictionary definitions

that are not based on rule-like contexts may not reflect the understanding

of “ordinary readers.”

Second, we argue that our results suggest the importance of anti-liter-

alism in assessing ordinary meaning. Our study reveals that ordinary peo-

ple often interpret rules nonliterally. This bears on recent debates at the

heart of textualist theory.

58

Our findings support rejecting ordinary mean-

ing as being synonymous with literal meaning. Specifically, several of the

canons implicitly applied by ordinary people result in nonliteral mean-

ings.

59

Perhaps most importantly, such a commitment to nonliteralism

challenges modern textualist practices and may have the salutary eect of

decreasing judicial reliance on dictionary definitions and increasing judi-

cial sensitivity to context.

Third, we argue that interpretive canons should be understood as an

open set, despite conventional assumptions that the traditional canons cap-

ture all relevant language generalizations. Our study provides evidence in

support of two new ordinary meaning canons—ones not traditionally rec-

ognized by law, but that can be justified on the basis of ordinary meaning.

One we term the “nonbinary gender canon.”

60

The other we term the

“quantifier domain restriction canon.”

61

Courts committed to ordinary

meaning have no less reason to rely on newly discovered canons than tra-

ditional ones assumed to reflect ordinary meaning. More broadly, this the-

ory of ordinary meaning canons as an “open set” invites empirical discov-

ery of new language canons, allowing a much more dynamic statutory

interpretation based on linguistic dynamism. This dynamism is not only

consistent with textualists’ ordinary meaning commitments; it is justified

by them.

62

We conclude by arguing for a new empirical research agenda in law

and language. This project is ambitious and forward-looking, testing fun-

damental empirical assumptions underpinning interpretive canons, dis-

covering entirely new canons, reconceptualizing the ordinary meaning

doctrine as one concerned with rules, proposing an anti-literalist view of

some interpretive canons, and articulating a program for future research.

We see our study as a first step in this new direction. We hope future stud-

ies uncover further evidence about the triggering conditions of certain

58. See infra section IV.B.1 (discussing literal interpretations).

59. See infra section IV.B.2 (discussing examples including gender canons, number

canons, ejusdem generis, and noscitur a sociis).

60. This canon holds that masculine and plural pronouns like “he/his” and “they”

also include the feminine (e.g., “her”) and nonbinary (e.g., “they”). See infra section II.B.1.

61. This canon holds that the scope of quantifiers (e.g., “any”) is typically implicitly

restricted by context, which is a linguistic fact the Supreme Court has long struggled to

recognize. See infra section II.C.4.

62. See infra section IV.C.

226 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

canons, discover additional “hidden” ordinary meaning canons, and test

how canons are cancelled or whether they are applied consistently.

I.

A FRAMEWORK FOR TESTING INTERPRETIVE PRINCIPLES

This Part provides a theoretical framework necessary for testing which

interpretive principles reflect ordinary people’s understanding of lan-

guage. It explains that every interpretive canon has three essential compo-

nents to its definition: (1) triggering, (2) application, and (3) cancellation.

Identifying the trigger for an interpretive canon is essential to testing

whether ordinary people intuitively apply the canon. The basic issue of

interpretive canon triggering is thus the critical focus of our empirical in-

quiries, as opposed to the more involved questions of how canons are or-

dered or applied in complex legal scenarios.

63

In focusing on this basic

issue, we divide potential ordinary meaning canons into two categories

that correspond to dierent ways in which context interacts with language

generalities. The first category—often called “semantic” or “syntactic”

canons—includes those triggered by specific linguistic phenomena, such

as the presence of a specific word or comma. The second category includes

canons triggered by certain kinds of linguistic formulations or contexts,

rather than by specific language. For example, the ejusdem generis canon is

triggered by the linguistic formulation of general words preceding or

following a list of more specific things.

A. Testing How Canons Are Triggered

The most basic issue regarding the testing of interpretive canons con-

cerns the tension between the generality of language rules and the in-

tensely contextual nature of legal interpretation. An ordinary meaning de-

termination must cut across contexts unconnected to any particular

Congress, subject matter, or statute.

64

Ordinary meaning interpretive can-

ons thus depend on general presumptions about language usage, but

courts assume that contextual evidence pointing to a dierent interpre-

tation might outweigh these presumptions.

65

In that sense, presumptions

63. See James J. Brudney, Canon Shortfalls and the Virtues of Political Branch

Interpretive Assets, 98 Calif. L. Rev. 1199, 1202 (2010) (“The Court has never developed

rules for harmonizing or prioritizing among the scores of existing canons, many of which

the Court has created in recent decades.”); Krishnakumar & Nourse, supra note 31, at 167

(“[P]recedent and legislative history should take precedence over rules like noscitur a

sociis.”).

64. See Brian G. Slocum & Jarrod Wong, The Vienna Convention and the Ordinary

Meaning of International Law, 46 Yale J. Int’l L. 191, 195 (2021) (noting the transsubstantive

nature of ordinary meaning).

65. See John F. Manning, The Absurdity Doctrine, 116 Harv. L. Rev. 2387, 2465 n.285

(2003) [hereinafter Manning, The Absurdity Doctrine] (noting that textual canons “serve

only as rules of thumb . . . that help users of legal language discern meaning”).

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 227

about ordinary language usage are defeasible; they may be overridden by

the specific context of the statute or by other canons.

66

To analyze the interpretive process, we consider three essential issues:

(1) the facts that trigger the canon, (2) the circumstances relevant to ap-

plying the canon, and (3) the circumstances relevant to cancelling the lan-

guage presumption.

67

Our empirical research question focuses on whether

ordinary people, as a general matter, implicitly invoke a given interpretive

canon when interpreting language (which is issue #1). As such, it is neces-

sary to neutralize circumstances relating to issues #2 and #3, which include

other potentially applicable interpretive canons along with facts and infor-

mation not related to how the canon is triggered.

To illustrate this point, consider ejusdem generis.

68

That canon is trig-

gered by a catchall following a list of terms.

69

When one sees a statute that

lists “cars, buses, motorcycles, and all other vehicles,” the recognition that

there is a list concluding with a general term triggers the canon.

70

The fact

that ejusdem generis is “triggered” does not tell us everything there is to

know about how it ultimately applies, however. The canon predicts that

“all other vehicles” would not be understood to apply to literally any vehi-

cle. But to apply the canon, the interpreter must consider what common

generalization the list describes. In the example above, the interpreter

could consider (at least) two dierent generalizations: all vehicles with

engines (covering lawn mowers) or all wheeled vehicles (covering

wheelbarrows). Applying the canon—deploying one or another gener-

alization—is dierent from knowing that the canon has been triggered

(i.e., that “any other vehicle” is restricted in some way from its literal mean-

ing).

66. See, e.g., Lockhart v. United States, 577 U.S. 347, 355 (2016) (“This Court has long

acknowledged that structural or contextual evidence may ‘rebut the last antecedent

inference.’” (quoting Jama v. Immigr. & Customs Enf’t, 543 U.S. 335, 344 n.4 (2005)));

Taniguchi v. Kan Pac. Saipan, Ltd., 566 U.S. 560, 569 (2012) (“[T]he word ‘interpreter’ can

encompass persons who translate documents, but because that is not the ordinary meaning

of the word, it does not control unless the context in which the word appears indicates that

it does.”).

67. Commentators have at times conflated these separate issues. Most famously, Karl

Llewellyn purported to show that every canon can be countered by an equal and opposite

countercanon, which he argued deprives canons of any probative force in the interpretive

process. See Karl N. Llewellyn, Remarks on the Theory of Appellate Decision and the Rules

or Canons About How Statutes Are to Be Construed, 3 Vand. L. Rev. 395, 401–06 (1950). As

various scholars have noted, however, “[t]he large majority of Llewellyn’s competing

canonical couplets are presumptions about language and extrinsic sources, followed by

qualifications to the presumptions.” William N. Eskridge, Jr., Norms, Empiricism, and

Canons in Statutory Interpretation, 66 U. Chi. L. Rev. 671, 679 (1999).

68. See supra notes 22–29 and accompanying text.

69. See supra notes 22–29 and accompanying text.

70. For a more detailed explanation of this canon, see infra section I.C.

228 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

Similarly, a canon’s trigger diers from considerations that might can-

cel the application of the canon. So, in the vehicle example, one might

understand that the canon is triggered, consider the possible general-

ization the list describes, and come to an initial conclusion about the stat-

ute’s meaning. Perhaps one may intuitively take “cars, buses, motor-

cycles, and all other vehicles” to exclude canoes. But the same interpreter

might abandon that initial conclusion after learning, for example, that the

statute provides a broad definition of the term “vehicle” elsewhere.

71

Sim-

ilarly, an interpreter might determine that the provision’s purpose

strongly indicates that the catchall should be given a broader meaning.

72

1. Context and Interpretation. — The distinction between triggering and

application or cancellation mirrors the longstanding legal understanding

of interpretation as involving both language generalities and the context

that shapes and modifies those language generalities. Justice Holmes

famously posited that the interpreter’s role is to determine “what th[e]

words [of the legal text] would mean in the mouth of a normal speaker of

English, using them in the circumstances in which they were used.”

73

As

such, the interpreter must consider the general and the specific and

choose an interpretation based on: (1) the language assumptions created

by the interpreter’s general knowledge of language usage, as shaped by

(2) inferences about what the language means in its specific context.

74

This

interpretive inquiry, as conceived by Justice Holmes, was necessarily objec-

tified and not empirical. At the time, no mechanisms existed for testing

language conventions or determining how actual ordinary people might

interpret a given legal text.

75

In determining a statute’s meaning, the interpreter must therefore

consider both facts based on language generalizations and facts about the

specific context of the statute.

76

When an interpretive canon is implicated,

71. See Tanzin v. Tanvir, 141 S. Ct. 486, 490 (2020) (explaining that statutory

definitions supplant “ordinary meaning”). In this case, the interpreter would have to

reconcile two dierent statutory definitions.

72. See Scalia & Garner, supra note 3, at 209–10 (discussing examples of catchall

language that would have no eect if limited only to the class of enumerated items, and

concluding that in such cases, the inclusion of the catchall demonstrates an intent by

drafters to broaden the meaning of the provision beyond the enumerated class).

73. Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Theory of Legal Interpretation, 12 Harv. L. Rev. 417,

417–18 (1899).

74. See Eskridge, Interpreting Law, supra note 3, at 3–11 (discussing the importance

of context to interpretation).

75. Even if aspects of the interpretive process are capable of being empirically based,

such as empirical validation of interpretive canons, we argue that the ultimate statutory

interpretation is not a matter of empiricism. Instead, it is based on a combination of various,

often conflicting sources of meaning, making necessary a resort to some sort of objectified

interpreter.

76. Interpreters must consider both language generalizations and specific context

regardless of whether language canons are all valid.

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 229

the interpreter must understand the facts that trigger the canon as well as

the circumstances relevant to applying the canon or cancelling its pre-

sumption. This is a synergistic model of meaning, in which general

assumptions about language exist along with specific inferences from con-

text. In fact, ordinary people routinely use contextual evidence to make

communication more ecient. Often, relying on the interpreter to exploit

contextual elements to discern the correct meaning is more ecient than

the author taking the time necessary to make the linguistic meaning

clear.

77

Thus, ecient communication frequently involves recognition of

nonliteral and implied meanings triggered by contextual evidence.

78

Still,

the consideration of context can make the interpretive process more

dicult and uncertain, such as when a language generalization is in

tension with aspects of context or other applicable linguistic conven-

tions.

79

2. The Categories of Interpretive Canons. — Even though context is an

essential aspect of interpretation, an interpreter cannot make sense of a

text without making assumptions about its linguistic meaning.

80

These lan-

guage generalizations frequently involve basic issues regarding conven-

tional word meanings and punctuation rules but may also include more

77. See Brendan Juba, Adam Tauman Kalai, Sanjeev Khanna & Madhu Sudan,

Compression Without a Common Prior: An Information-Theoretic Justification for

Ambiguity in Language, Innovations Comput. Sci., 2011, at 79, 79, https://conference.

iiis.tsinghua.edu.cn/ICS2011/content/paper/23.pdf [https://perma.cc/CY76-LN5M] (“[I]t

is easy to justify ambiguity to anyone who is familiar with information theory.”); Hannah

Rohde, Scott Seyfarth, Brady Clark, Gerhard Jaeger & Stefan Kaufmann, Communicating

With Cost-Based Implicature: A Game-Theoretic Approach to Ambiguity, in Proceedings of

SemDíal 2012 (SeíneDíal) 107, 108 (Sarah Brown-Schmidt, Jonathan Ginzburg & Staan

Larsson eds., 2012), http://semdial.org/anthology/Z12-Rohde_semdial_0015.pdf [https:

//perma.cc/S6Y6-TD9T] (“Rather than avoiding ambiguity, speakers show behavior that is

in keeping with theories of communicative eciency that posit that speakers make rational

decisions about redundancy and reduction.”).

78. See Steven T. Piantadosi, Harry Tily & Edward Gibson, The Communicative

Function of Ambiguity in Language, 122 Cognition 280, 281 (2012) (“[W]here context is

informative about meaning, unambiguous language is partly redundant with the context

and therefore inecient . . . .”).

79. The Supreme Court’s controversial decision in King v. Burwell, 135 S. Ct. 2480

(2015), is one notable example where the ordinary meaning of the statutory language was

in tension with relevant context. In interpreting one of the Aordable Care Act’s key

provisions referring only to “State” as including both federal and state governments, the

Court reasoned that a literal interpretation would “make little sense,” and thus that “when

read in context,” the relevant provisions were “properly viewed as ambiguous.” Id. at 2490–

92. As Justice Scalia argued in dissent, the semantic meaning of the relevant language was

clear. See id. at 2497 (Scalia, J., dissenting) (“It is hard to come up with a clearer way to limit

tax credits to state Exchanges than to use the words ‘established by the State.’”).

80. See Eskridge et al., The Meaning of Sex, supra note 5, at 1517 (“From a linguistic

perspective, considerations of context and purpose are ineliminable aspects of the ordinary

meaning determination. . . . For example, in determining whether a ‘no vehicles’ law

prohibits bicycles from the park, the interpreter . . . might consider the perceived purpose

of the law . . . .”).

230 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

subtle generalizations involving the interaction between linguistic mean-

ing and context.

81

To best assess these language generalizations, empirical

studies should present narrow scenarios to test whether a canon is trig-

gered in accordance with its definition. Thus, broader scenarios should be

avoided that simultaneously raise issues relating to canon application or

cancellation, or the ordering of canons in cases where they conflict.

82

For

example, in testing the triggering conditions of ejusdem generis, it is more

helpful (for our purposes) to study how ordinary people understand a list

concluding with a general term than to study how ordinary people would

decide the McBoyle case. The former approach isolates only the material

relevant to canon triggering. Results using the latter approach might also

reflect application or cancellation or competing canons, as well as

participants’ views about the specific facts of McBoyle or their intuitions

about which interpretation is fairer to the parties.

In focusing on canon triggering, we divide potential ordinary mean-

ing canons into two categories to highlight the dierent ways in which con-

text interacts with language generalities.

83

The two categories address so-

called “textual canons,” which are varied presumptions about meaning

“that are usually drawn from the drafter’s choice of words, their grammat-

ical placement in sentences, and their relationship to other parts of the

‘whole’ statute.”

84

The presumptions typically are said to be based on gen-

eral principles of language usage rather than legal concerns.

85

81. A “generalization” concerns a linguistic regularity in a repeated context. See

Florent Perek & Adele E. Goldberg, Linguistic Generalization on the Basis of Function and

Constraints on the Basis of Statistical Preemption, 168 Cognition 276, 277 (2017) (explain-

ing that in an artificial language experiment, a factor that plays a role in determining

whether speakers are willing to generalize the way a verb is used is whether other verbs have

already been witnessed being generalized).

82. See infra Part II; see also Tobia, Experimental Jurisprudence, supra note 53, at 3–

9 (describing the dierent methodological approaches of experimental jurisprudence and

legal psychology that aim to model jury decisionmaking).

83. Scholars have proposed various ontologies that account for the dierences among

interpretive canons, but the basic distinction is between “substantive” and “textual” canons.

See, e.g., Gluck & Bressman, Statutory Interpretation Part I, supra note 33, at 924–25

(distinguishing between “textual canons” and “substantive canons”). We divide interpretive

canons into categories solely to oer a framework that will assist in the empirical evaluation

of the canons.

84. William N. Eskridge Jr. & Philip P. Frickey, Cases and Materials on Legislation:

Statutes and the Creation of Public Policy 634 (2d ed. 1995).

85. See William Baude & Stephen E. Sachs, The Law of Interpretation, 130 Harv. L.

Rev. 1079, 1121 (2017) (“Linguistic canons . . . are just attempts to read whatever the

authors wrote, according to the appropriate theory of reading . . . .”); Abbe R. Gluck &

Richard A. Posner, Statutory Interpretation on the Bench: A Survey of Forty-Two Judges on

the Federal Courts of Appeals, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 1298, 1330 (2018) (distinguishing between

“‘linguistic’ or ‘textual’ canons, which are presumptions about how language is used,” and

“substantive” or “policy” canons, which are normative presumptions).

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 231

The first category covers canons triggered by specific linguistic phe-

nomena and minimal context. Some of these canons broaden the literal

meaning

86

of a provision.

87

The second category includes so-called “con-

textual canons,”

88

triggered by linguistic phenomena but requiring con-

sideration of the broad context of a statute for their application.

89

These

so-called “contextual canons” are each triggered by a certain kind of lin-

guistic formulation or context,

90

rather than by precise language, and each

requires that the interpreter evaluate context when applying the canon.

Typically, these contextual canons narrow the literal meaning of a provi-

sion. With respect to canons in either category, we argue that an interpre-

tive principle should be considered an “ordinary meaning canon” if ordi-

nary people would implicitly apply its interpretive presumption when

interpreting rules.

91

This is so regardless of whether ordinary people are

aware of such usage or could even identify the canon by name.

86. The term “literal meaning” is used throughout this Essay and is meant to refer to

the linguistic meaning of the relevant sentence that is conventional and context

independent. See C. J. L. Talmage, Literal Meaning, Conventional Meaning and First

Meaning, 40 Erkenntnis 213, 213 (1994). Essentially, then, literal meaning is based on the

conventional meaning of language, which is primarily tied to the semantic meanings of the

words. See François Récanati, Literal Meaning 3 (2004); Lawrence B. Solum, Commu-

nicative Content and Legal Content, 89 Notre Dame L. Rev. 479, 487 (2013) [hereinafter

Solum, Communicative Content] (“In law, we refer to semantic content as ‘literal meaning.’

This phrase is rarely theorized when it is used, and it may be ambiguous, but when lawyers

refer to the literal meaning of a legal text, it seems likely that they are referring to its

semantic meaning.”).

87. See infra section IV.A.2 (describing how these canons can broaden literal

meaning).

88. Scalia & Garner, supra note 3, at xiii–xiv.

89. We include the expressio unius est exclusio alterius canon in the category, which Scalia

& Garner label as a “semantic canon.” Id. at xii. Although nothing in our project turns on

this categorization, the expressio unius canon does not help determine the semantic meaning

of any explicit language but, rather, provides for a completeness inference (at least in some

circumstances). See infra notes 153–156 and accompanying text.

90. The expressio unius canon likely depends on context for its application but, when

applied, forbids the expansion of the literal meaning of a provision. See infra notes 153–

156 and accompanying text.

91. In labeling an interpretive canon an “ordinary meaning canon,” we refer to

“ordinary meaning” in a general way that corresponds to the interpretive practices of

ordinary people and do not choose among possible technical definitions of “ordinary

meaning.” We also do not select among the various possible tests for designating an inter-

pretive principle as a “canon.” It has been suggested, for instance, that “canonical status”

may require some showing of “historical pedigree, longevity, regularity of use,” or other

indication of longstanding usage. See Krishnakumar & Nourse, supra note 31, at 164. We

refer to the interpretive rules applied by ordinary people as “ordinary meaning canons” and

argue that the existing set of interpretive canons is incomplete, but we do not join the debate

regarding when the term “canon” should be used when referring to an interpretive

principle.

232 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

B. Category One Canons

The first category of interpretive canons includes those triggered by

specific linguistic phenomena and minimal context. These interpretive

principles are often referred to as “semantic canons” or “syntactic can-

ons,” among other terms.

92

Thus, for instance, a grammatical rule may be

triggered by the presence (or absence) of a comma.

93

Consider the

“Oxford comma rule,” one of the interpretive principles we tested.

94

The

term refers to a comma used after the penultimate item in a list of three

or more items, the presence of which can create an additional distinct item

or category.

95

The presence (or absence) of such a comma can therefore

have interpretive significance. Thus, if the Oxford comma rule is followed,

(1) Joe went to the store with his parents, Mike, and Michelle.

has a dierent meaning than does

(2) Joe went to the store with his parents, Mike and Michelle.

The presence of a second comma in (1) is the only linguistic dier-

ence between (1) and (2), but, arguably, this dierence changes the mean-

ing of (1) compared to (2). In (1), “Mike” and “Michelle” are not Joe’s

parents, but in (2), they are his parents.

The Oxford comma rule is a relatively straightforward interpretive

canon. Its trigger is a comma after the penultimate item in a list of three

or more items; additional context is not necessary for the rule’s applica-

tion. The Oxford comma rule, if valid, helps determine the literal meaning

of a provision, even if it is defeasible. For example, a judge may consider

the canon applicable but find that the broad context of a provision indi-

cates that applying it would be inconsistent with other statutory provisions

or undermine the purpose of the provision in some way.

96

The Oxford comma rule could also, of course, apply in legal contexts.

Consider two statutes that provide exemptions from overtime wages. One

statute provides as follows:

(3) The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying,

marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution of:

(1) Agricultural produce;

(2) Meat and fish products; and

92. See Scalia & Garner, supra note 3, at xii–xiii (describing and defending eleven

“semantic canons” and seven “syntactic canons”).

93. See Lance Phillip Timbreza, Note, The Elusive Comma: The Proper Role of

Punctuation in Statutory Interpretation, 24 Quinnipiac L. Rev. 63, 67 (2005) (explaining

the Supreme Court’s creation of “Punctuation Doctrines” for statutory interpretation).

94. See John Inazu, Unlawful Assembly as Social Control, 64 UCLA L. Rev. 2, 13–14

(2017) (discussing problems created by the absence of an Oxford comma).

95. See Oxford Comma, Dictionary.com, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/

oxford-comma [https://perma.cc/SGY5-QQ8M] (last visited Sept. 1, 2021).

96. See infra section I.D (describing the defeasibility of interpretive canons).

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 233

(3) Perishable foods.

97

The following hypothetical statute is the same except for the addition of a

comma after “shipment”:

(4) The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying,

marketing, storing, packing for shipment, or distribution of:

(1) Agricultural produce;

(2) Meat and fish products; and

(3) Perishable foods.

The first statute was an actual Maine statute, and the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the First Circuit held that delivery drivers did not fall within

the exemption’s scope, explaining that the provision was “ambiguous”

after considering the “relevant interpretive aids,” including the “absent

comma.”

98

Would the interpretive dispute have been decided dierently

if the Maine statute contained the additional comma, as in (4)?

99

If ordi-

nary people would interpret (4) more broadly than (3), i.e., as containing

an additional category, that would provide some intuitive support for the

Oxford comma rule.

100

Other canons based on punctuation rules are similar to the Oxford

comma rule, but Category One is not limited to punctuation rules. Below

are the interpretive canons we tested in the first category:

97. Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 26, § 664(3)(F) (2017).

98. O’Connor v. Oakhurst Dairy, 851 F.3d 69, 72 (1st Cir. 2017). The statutory

provision at issue in this case, see supra note 97 and accompanying text, was amended in

late 2017 to replace the commas with semicolons and add a semicolon between “shipment”

and “or distributing of.” The revised provision stated, “The canning; processing; preserving;

freezing; drying; marketing; storing; packing for shipment; or distributing of: (1)

Agricultural produce; (2) Meat and fish products; and (3) Perishable foods.” Me. Rev. Stat.

Ann. tit. 26, § 664(3)(F) (eective Nov. 1, 2017).

99. The validity of the Oxford comma rule does not depend on such a showing. Other

interpretive evidence (such as from legislative history or other text) could still outweigh the

probabilistic force of the Oxford comma rule. In fact, the court did consider the law’s

purpose and legislative history. See Oakhurst Dairy, 851 F.3d at 77–78.

100. Namely, that support would come if ordinary people made this judgment without

consideration of the other contextual evidence that was also addressed by the First Circuit

(e.g., legislative history). The other contextual evidence is not related to whether a

grammatical rule is triggered but rather whether any grammatical rule is cancelled by the

other evidence.

234 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

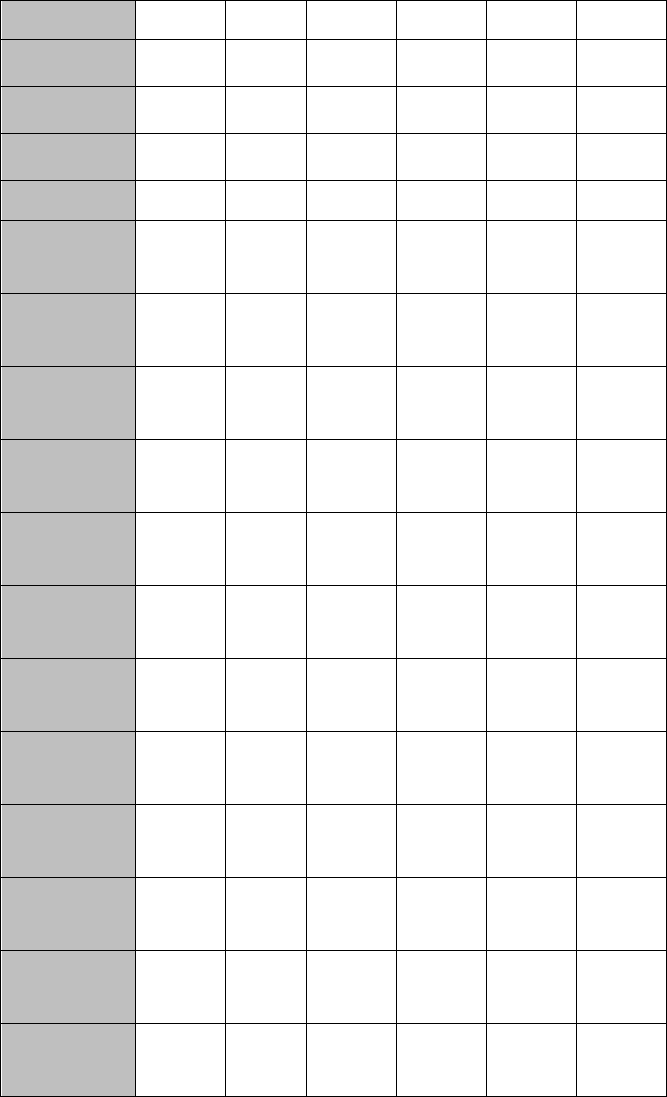

TABLE 1. CATEGORY ONE CANONS

Gender and Number Canons

In the absence of a contrary indication,

the masculine includes the feminine

(and vice versa), and the singular in-

cludes the plural (and vice versa).

101

“And” vs. “Or”

(Conjunctive/Disjunctive

Canon)

“And” joins a conjunctive list; “or” a

disjunctive list.

102

“May” vs. “Shall”

Mandatory words, such as “shall,”

impose a duty while permissible words,

such as “may,” grant discretion.

103

Oxford Comma

A comma used after the penultimate

item in a list of three or more items, the

presence of which can create an

additional distinct item or category.

104

Presumption of Nonexclusive

“Include”

The verb “to include” introduces

examples, not an exhaustive list.

105

Series-Qualifier Canon

When there is a straightforward paral-

lel construction that involves all nouns

or verbs in a series, a prepositive or

postpositive modifier normally applies

to the entire series.

106

Rule of the Last Antecedent

(1) A pronoun, relative pronoun, or

demonstrative adjective generally

refers to the nearest reasonable ante-

cedent.

(2) When a modifier is set o from a

series of antecedents by a comma, the

modifier should be interpreted to ap-

ply to all of the antecedents.

107

101. See Scalia & Garner, supra note 3, at 129.

102. See id. at 116.

103. See id. at 112.

104. See supra notes 93–100 and accompanying text (describing the Oxford comma

rule).

105. See Scalia & Garner, supra note 3, at 132.

106. See id. at 147.

107. See id. at 144.

2022] STATUTORY INTERPRETATION FROM THE OUTSIDE 235

Some of these interpretive canons may be more easily cancellable

than others. That is an issue beyond the scope of our project. In each case,

however, these interpretive canons are triggered by specific linguistic phe-

nomenon and minimal context. Our empirical study assesses those trig-

gering conditions.

C. Category Two Canons

The second category of interpretive canons includes those textual

canons triggered by a certain kind of linguistic formulation or context,

rather than by precise language. Each of these canons interacts with the

literal meaning of a provision in some way, typically by narrowing it, on the

basis of inferences from context. Although these canons are triggered by

specific kinds of language, there are no limits on the contextual evidence

that can be considered in applying the canons, allowing judges to consider

broad evidence about legislative purpose when applying the canons.

108

The unlimited recourse to contextual evidence may make the application

of these “contextual canons” discretionary and unpredictable, but we

focus only on whether the canons have discrete and consistent triggers.

109

Below are the four canons in this category that we test:

108. See Anita S. Krishnakumar, Backdoor Purposivism, 69 Duke L.J. 1275, 1304–05

(2020) [hereinafter Krishnakumar, Backdoor Purposivism] (explaining that textualist

Justices have engaged in purposive analysis when applying contextual canons); see also

Eskridge & Nourse, supra note 35, at 7 (arguing that theorists have not fully analyzed the

concept of context).

109. See Krishnakumar, Backdoor Purposivism, supra note 108, at 1291 (arguing that

some judges use textual canons in broad, purposivist ways that serve as “launch pads for

assuming or constructing legislative purpose and intent” (emphasis omitted)).

236 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 122:213

TABLE 2. CATEGORY TWO CANONS

Noscitur a sociis

The meaning of words placed together in a

statute should be determined in light of the

words with which they are associated.

110

Ejusdem generis

When general words in a statute precede or

follow a list of specific things, the general

words should be construed to include only