The re-accomplishment of place in twentieth century

Vermont and New Hampshire: history repeats itself,

until it doesn’t

Jason Kaufman & Matthew E. Kaliner

Published online: 27 January 2011

#

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011

Abstract Much recent literature plumbs the question of the origins and

trajectories of “place,” or the cultural development of space-specific repertoires

of action and meaning. This article examines divergence in two “places” that

were once quite similar but are now quite far apart, culturally and politically

speaking. Vermont, once considered the “most Republican” state in the United

States, is now generally considered one of its most politically and culturally

liberal. New Hampshire, by contrast, has remained politically and socially quite

conservative. Contrasting legacies of tourist promotion, political mobilization,

and public policy help explain the divergence between states. We hypothesize

that emerging stereotypes about a “place” serve to draw sympathetic residents

and visitors to that place, thus reinforcing the salience of those stereot ypes and

contributing t o their reality over tim e. We term this l atter process idio-cultural

migration and argue its centrality to ongoing debates about the accomplishment of

place. We also elaborate on several means by which such place “reputations” are

created, transmitted, and maintained.

Keywords Migration

.

Culture

.

American politics

In their widely cited, prize-winning article, “History repeats itself, but how? City

character, urban tradition, and the accomplishment of place,” Molotch et al. (2000)

explore an extremely trenchant sociological problem: How do geographical spaces

become sociological places, locales with distinctive cultural, social, and political

characteristics? By focusing on two locales that might well have evolved along similar

lines but did not—Santa Barbara and Ventura, California—they employ a most useful

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

DOI 10.1007/s11186-010-9132-2

J. Kaufman (*)

Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University , 23 Everett St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

e-mail: jkaufm[email protected]rvard.edu

M. E. Kaliner

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

methodological technique, “most similar cases” (Mill 1881;Skocpol1984; Tilly

1984), to study a cutting-edge sociological problem.

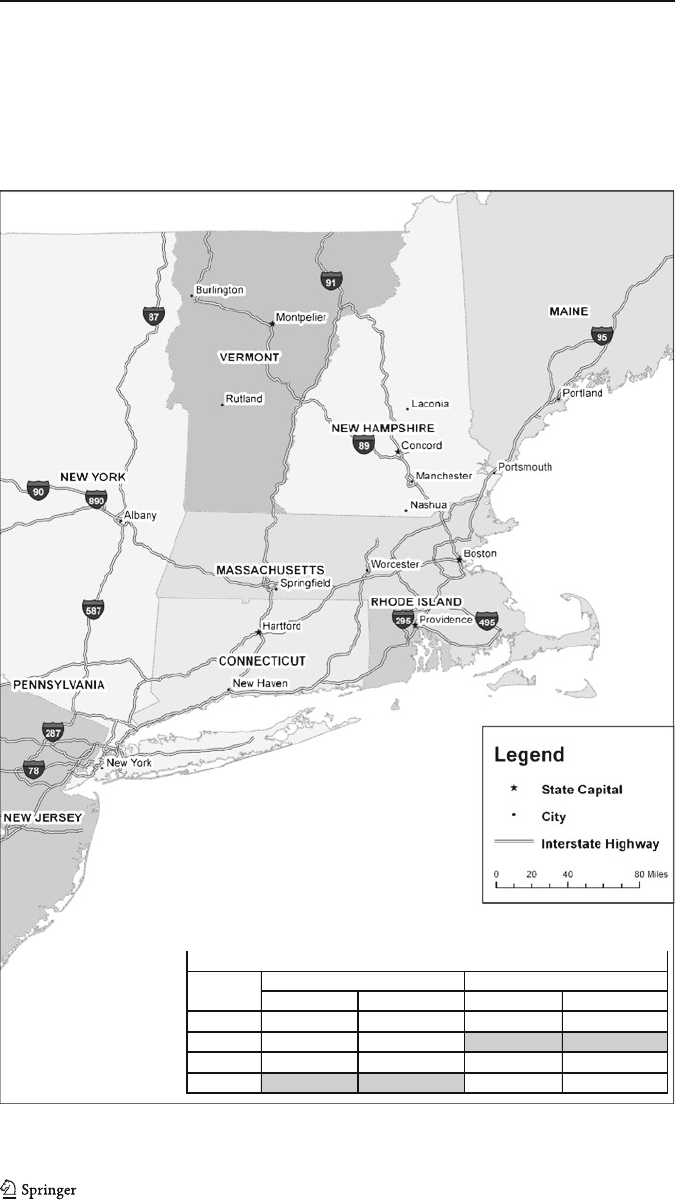

In order to contribute to this scholarly tradition, we examine here both the

“accomplishment of place” in twentieth century Vermont and the contrasting “place”

trajectory of neighboring New Hampshire (see Map 1). These neighboring states had

Miles Years Built Miles Years Built

I-89 130 1960-1968 61 1958-1968

I-91 177 1958-1978

I-93 11 1963-1982 132 1954-1986

1948-195016I-95

New HampshireVermont

Interstate

High way

Major Interstate Highways: Lengths and Years Built

Map 1 Interstate highway map and transit information for Vermont, New Hampshire and surrounding

states

120 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

quite similar “place” reputations throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries, but by the late twentieth century they had radically diverged.

We herein define the “accomplishment of place” as the achievement of a locale’s

subjective reputation as perceived by insiders (residents) and outsiders (non-

residents). In plain English, this refers to the process whereby both in-state and out-

state residents come to identify a specific place with specific values, resources, and

behaviors, the emphasis being on the perception of place, as opposed to the accuracy

of said perception. We stress throughout our account the many pre-existing

similarities of Vermont and New Hampshire and the fact that an arbit rary state

“border” has afforded the development of two distinct social spaces in ways that are

difficult to explain in terms of mere “path dependency.”

Our analysis of these cases aims to contribute to the “accomplishment of

place” literature in three ways: first, we extend this style of “place-based”

analysis from the city to the rural and state levels (cf., Searls 2003)in

recognition of the fact that the literature on space and place tends to focus

primarily on cities (e.g., C hing and Creed 1997). Second, in contrast to Molotch et

al. (2000), who focus on a process they call “rolling inertia,” we examine a case in

which “history did [not] repeat itself”—Vermont made a rather abrupt about-face

over the course of the twentieth century. Through detailed analysis of this

counter f act ua l, we deve lo p a new p e rsp ec tive on place-building. Third, we offer a

two-sided model of the accomplishment of place that tracks not only the changing

image of Vermont in the public mind but also the response of would-be

participants to that change. This approach should be seen in contrast to bulk of

the current li terature on city “brandi ng” an d “place marketing” (e.g., Clark 2004;

Gottdiener 2001;Greenberg2008;Hannigan1999;Harvey2001; Judd and

Fainstein 1999; Kearns and Philo 1993; Sorkin 1992), all of which presume t hat

tourists and residents passively respond to most, if not all, efforts to lure them. One

of the key processes underlying the “accomplishment of place” in our research is

the way residents, politicians, bureaucrats, and entrepreneurs actively shaped the

social character of their locales. Place, in this sense, is truly an “accomplishment,”

though one often forged without consensus or coordination. These analytic and

theoretical lacunae are fundamental to understanding the

“accomplishment of

place.”

Extensive quantitative a nd qualitati ve r esearch has led us to conclude that a

specific type of population migration was a key element in the transformative

place-building process studied here. As Vermont’s place reputation developed

and changed, new types of people were inspired to move there, people who saw

something in the state’s local cultur e that reso nat ed with their own value s. By

moving to the state, these new residents helped expand and entrench Vermont’s

place reputation, thus reinforcing the salience of those stereotypes and

contributing to their reality (cf., Merton 1968). Some degree of cohort

replacement l ikely contributed to Vermont’s t ransform ation—younger generations

likely espoused different lifestyles and preferences than their forebears—but absent

a major inter-generational shift in Vermont but not elsewhere in the United States,

it seems hard to explain Vermont’s trajectory without reference to newcomers:

people like Howard Dean, Bernie Sanders, Ben & Jerry—all archetypal

Vermonters born and raised out-of-state.

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 121121

We coin the term idio-cultural migration to refer to population migration based

on place-specific cultural preferences.

1

In so doing, we borrow and build on the term

“idio-culture” as used by Fine (1979, p. 734), who defines it as, “a system of

knowledge, beliefs, behaviors, and customs shared by members of an inte racting

group to which members can refer and employ as the basis of further interaction.”

Idio-cultural migration refers to more than mere “lifestyle migration,” in other

words, or the process of moving to a place because of the cultural ameni ties it offers

(cf., Frey 2002). Idio-cultural migration refers to migrants’ motivation to seek and

join a collective socio-cultural milieu. Fine applies idio-culture to “small groups”

such as clubs and teams, but we find it equally useful in conceptualizing the

experience and existence of “place” at any level—spheres of reference wherein

members recognize themselves and others as part of a common enterprise with

mutual meanings and experiences.

Key for our purpose is Fine’s(1979: 734) specification that,

Members recognize that they share experiences in common and these

experiences can be referred to with the expectation that they will be understood

by other members, and further can be empl oyed to construct a social reality.

The term, stressing the localized nature of culture, implies that it need not be

part of a demographically distinct subgroup, but rather that it is a particularistic

development of any group in the society.

Idio-cultural migration entails more than just “birds of a feather flocking together,” in

other words; it encompasses not only homophily but the active re-negotiation of the

reputation and meanings associated with place, as well as the reflexive definition of

“other” neighboring places.

Conceptually speaking, our “idio-cultural” concept of intra-state migration

contrasts with the view typically posed by demographers and economists, who tend

to see inter-state moves as being primarily motivated by economic concerns such as

jobs, wages, and housing costs (e.g., Lowery and Lyons 1989; Percy et al. 1995;

Preuhs 1999), or political preferences regarding the mixture of taxes and services

offered in a particular locale (cf. Tiebout 1956).

Our perspective also contrasts and makes more complex the theories of the “tourist

gaze” (Urry 1990), which posit a binary opposition between “that which is

conventionally encountered in everyday life” and the “extraordinary,” unusual

experiences gained while traveling away from home. Contemporary idio-cultural

migrants to Vermont appear to be trying to create permanent lives that deviate from the

“normal” American experience, thereby blurring the distinction between work and

leisure, the exotic and the everyday. “For over a century,” Harrison notes (2006, p. 11),

“tourism has forced rural work and rural leisure [in Vermont] into continual contact

with one another, such that the meanings, practices, and spaces associated with each

category have informed one another to the point of becoming mutually constitutive.

Tourism blurred the boundaries between work and leisure in rural places, making each

inseparable from the other.

” Urry (1990, pp. 101–102) himself concedes that a new

“post-tourist” movement is developing [in England] wherein the pastoral countryside

1

Molotch et al. (2000, p. 816) refer to the contribution of “selective migration” in the accomplishment of

place but skirt its actual mechanics. They do note, as do we, that “demographers typically ignore” it.

122 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

beckons and the division between work and pleasure that defines tourism breaks

down. One possible interpretation of this trend would be that idio-cultural migration

represents a new social movement to create distinct, non-normal, perhaps even

deviant, social spaces within the larger “normal” domestic social sphere.

Although idio-cultures similar to Vermont’s evolved in many places around the

country in the 1960s and 1970s, Vermont seems unique in the degree to which an

entire state was, and still is, seen through this lens, both nationally and locally. Binkley

(2007:2)summarizesthisethosas“getting loose,” an oppositional culture in which

“the blinkered, unknowing, constraining ways of the establishment are undermined by

a subterranean flow of expression and experience—a vernacular for a new hedonism,

to be sure, but one fashioned on an ambitious program of ethical self-renewal and a

singular commitment to the affirmation of feeling and impulse in daily life.” In the

Vermont context, this “loose” culture has historically been associated with practices

such as the consumption of illegal drugs, the practice of polyamory (“free love”), and

far-left political activism, particularly with respect to the environment. Hiking, skiing,

vegetarianism, organic farming, and “jam bands” such as Phish and The Grateful

Dead are pastimes commonly associated with Vermont as well.

Nonetheless, one would be mistaken to presume that all Vermonters aspire to this

“loose” ethos (Harrison 2006; Searls 2006). Nor would it be fair to presume a single,

consistent idio-culture in place or time. The “idio-cultures” described herein represent

malleable concatenations of cultural preferences and behaviors that are more imaged

than real—i.e., they are based on ster eotyp es about inhabitants of a specific place that

combine and confound various and often unrelated types of behavior, personal style,

cultural preference, and so on (Harrison 2006; McDonald 1993). What we will often see

in this depiction of place reputations is that they are best defined not in their own right

but in opposition to other cultures (cf. Lamont and Molnar 2002). Stereotypes contribute

to the accomplishment of place by creating and maintaining social boundaries—“they

render intimate, and sometimes menacing, the abstraction of otherness,” writes Herzfeld

(1992: 73). Regardless of their accuracy in fact, such collective stereotypes exist and, in

fact, stimulate their own realization through idio-cultural migration. Nonetheless, it

remains quite diff icult to describe, let alone operationalize the idio-cultures of which we

speak. Later, we will discuss some experimental methods for so doing, but we readily

admit that none is wholly satisfactory.

Although we illustrate the onset of mid-twentieth century idio-cultural migration

to Vermont in a number of different ways, survey data do not exist to test

systematically the plausibility of our observations about migrants’ motives for

moving.

2

If our own study achieves only one thing, it will be to alert social scientists

to the need to expand and itemize this category in future studies of intra-national

2

While the Census and Current Population Survey include raw mobility data and some attitudinal data,

both focus almost exclusively on economic motives for moving—housing prices, property taxes, and the

like. The Census includes data on which states migrants moved from, but this too reveals little about why

they chose to move. The Current Population Survey (CPS) only began asking respondents questions about

inter-state migrants’ motives for moving in 1997, and the data collapse virtually all motives beyond work,

family, or housing-related reasons to a residual “other reasons” category (US Census 2001) with four

options: attending college; for a change of climate; health reasons; and “other reasons.” The percentage of

respondents indicating this last residual category varied between 3% and 6% in the CPS national sample,

1997–2000.

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 123123

migration. Lacking more nuanced data on migration-motives, we draw on tourist

literature and narrative accounts of migration to each state in an effort to outline both

these trends and their causes and effects. We also offer qualitative data from informal

interviews conducted with residents, realtors, and scholars in both states, as well as

informal analysis of on-line materials currently available to those considering a

move to either state. These sources confirm our hunch that many Vermont residents

moved there because they perceived it to be a place offering a unique array of non-

economic benefits: from hippie enclaves to “artsy” towns and organic farms. We also

find ample evidence to support the observation that both the state government and

the resi dents of Vermont a ctively contributed to this image of Vermont, broadcasting

its appeal nationwide. New Hampshire’s real estate and tourist industries contrast

markedly with Vermont’s in this respect.

In trying to explain these divergent outcomes and the surprising shif t in Vermont’s

“place trajectory” more specifically, we are careful to consider a variety of

alternative explanations, from demographic composition to geography to climate to

economic development. While each of these factors has a role in the process, none

seem to explain the outcomes alone. Nor do we see the divergence in “place” to be

the simple result of pre-existing conditions in the two states.

Theoretical background: the accomplishment of place

It should be noted that, although we draw on the commu nity and urban sociology

literatures extensively, our empirical objects are in fact neither cities n or

communities. Vermont and New Hampshire are states (not municipalities), and rural

ones at that (cf., Ching and Creed 1997 ; Williams 1975). One of the key dimensions

of place is its flexibility with regard to scale (Gieryn 2000, p. 464). In Gieryn’s

useful approach, places are constituted by three distinct features: a geograp hic

location, material or physical form, and an “investment with meaning and value”

(465). It is this last point that is perhaps most fundamental to our understanding of

place. As Gieryn puts it, places are “doubly constructed”: first in terms of a physical

location but also as social spaces that must be “interpret ed, narrated, perceived, felt,

understood, and imagined” (465).

The idea that neighborhoods are defined by sentiments, images, and reputations—that

is, symbolic and cultural qualities—goes back to the core of the Chicago school’s

conceptualizatio n thereof (e.g., Park 1925, 1952). In his research on land use in

downtown Boston, Firey (1945, 1947) was the first to articulate an explicitly “cultural”

ecology of the city. Firey’s central point was that land use cannot be understood without

taking into account the symbols and cultural values that become lodged in certain

places. Firey (1945, p. 323) suggests that local history and tradition mark certain areas

of a city as “culturally contingent,” thus effecting future development and locational

decision-making among residents. Firey saw social actors adapting to the accumulated

meaning of places, suggesting, in a Durkheimien sense, that the symbolic qualities of

places should be treated as “things” that act back on inhabitants as restraints.

In The Social Construction of Communities,

Gerald Suttles (1972 ) takes up

Firey’s concerns, arguing that neighborhood identities emerge largely through

contrast with neighboring areas. Rather than persistence or adaptation, as Firey

124 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

might have it, Suttles stresses differentiation, putting weight on the uneven qualities

across adjoining locales as the source for place distinction. Suttles (1972, 1984) also

suggests that cultural “outsiders” like journalists, politicians, and even novelists, can

play key roles in assigning and disseminating place distinctions. We find similar

instances of socially constructed images of place here, though we see much more

than mere relative differentiation taking place. In our cases, for example, conflict

arises over efforts to shape and define place meaning. Enclaves of dedicated social

actors and organizations aspire to the accomplishment of place. Other recent studies

have found similar trends (e.g., Aguilar-San Juan 2005; Greenberg 2000, 2008;

Hiller and Rooksby 2002; Walton 2001; Wilson and Taub 2007; Zukin 1995). One

contribution of our study is its focus on an unusually sweeping degree of “place”

transformation occurring over an unusually long period of time.

Scholarly literature on the political economy of “place” tends to emphasize the role of

capitalists and their coalitions in place-building process (e.g., Brenner 2004; Greenberg

2008;Harvey1985; Judd and Fainstein 1999; Lefebvre 1991 [1974]; Logan and

Molotch 1987;Mele2000;Zukin1991). Place, in this sense, is a commodity, or

“brand,” and its meaning or character is carefully cultivated by business and government

boosters seeking to maximize their returns on investment (e.g., Clark 2004; Greenber g

2008; Nevarez 2003). Our approach contrasts with this in two ways: first, we examine

many non-e conomic motives and actors involved in the place-building process; second,

we stress the “reception” side of the equatio n, focusing on how such “branding” efforts

are received and reified by their intended (and unintended) audiences.

From the purview of Molotch et al. (2000), the accomplishment of place resembles a

process of “rolling inertia,” one that often defies the efforts of cultural agents

determined to create change—Ventura residents try to rejuvenate their ailing

downtown and fail, for example. Molotch et al. (2000) give names to these place-

building processes—

e.g.,“lashing up,”—but shed relatively little light on how “lash

up” works or why things might “lash up” differently in one place or another. The

Vermont case provides a useful counter-factual to this perspective, showing as it does

the way entrepreneurs, tourists, migrants, and political insurgents took advantage of

structural and political opportunities to refashion the social, political, and economic

landscape of their “place.” Nonetheless, while we may quarrel with some of the

conceptual language offered by Molotch et al. (2000), we build directly from their

work and in general share their (and others’)ambitiontoelevate“place distinctive-

ness” from a residual category to a central problem of contemporary sociology.

Documenting and explaining continuity and change: a preliminary model

of place-accomplishment

To clarify what we observe here to be the causal steps integral to the “place

transformation” of twentieth century Vermont, we offer the schematic Fig. 1:It

shows a sequence of events in chronological order and the actors involved in each. It

is impossible to know whether each stage was a necessary or sufficient component

of the “place transformation” process. We also lack the means to verify the necessity

of the exact sequence in which these events transpired. It does seem reasonable,

however, to assume that each part of the sequence built on and accentuated those

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 125125

before it (Abbott 2001). It seems evident, for example, that Vermont’s political

transformation of the 1930s through 1950s could have occurred without the prior

“branding” of Vermont, and vice-versa. These two steps also seem interchangeable

in terms of temporal sequence. However, both of these transformations occurred

before the onset of major population growth in Vermont—Vermont’s population

grew a mere 8.6% between 1930 and 1960 but boomed 30.9% from 1960 to 1980

(US Census 2001)—indirect evidence that idio-cultural migration did in fact follow

these two prior transformations. (It seems unlikely that 31,000 new residents—surely

not all voters—would have been responsible for Vermont’s vast political transfor-

mation in the 1940s and 1950s.) This observatio n is logically consistent with the

notion that something about the state’s image (and underlying reality) had to change

before new migrants began moving there in search of it. In-migration surely

accelerated these changes but only after the initial transformations had taken place.

3

In the course of our research, we explored as many hypothetical explanations as

possible before arriving at the current formulation. New Hampshire entered the

twentieth century as a slightly more urban, more industrial, and more immigrant-

laden society than Vermont, for example; however, we concluded that over-time

changes in these variables seemed insufficient explanation of the subsequent change

in their place reputations. Nationally speaking, furthermore, neither state has ever

been very urban, indus trial, or foreign-born, and these differences, small to begin

with, have largely converged over the course of the last century.

4

Economic and

demographic differences likely contributed to the different place environments in

both states, but these differences alone hardly begin to explain the divergent place

reputations under investigation here.

Since Vermont is proximate to New York City and New Hampshire to Boston (see

Map 1), it also seemed plausible that different spheres of influence might have shaped

the development of each state. Having reviewed the relative transportation and

migration history of each state, however, we concluded that it seems less important

where tourists and migrants came from than what brought them in the first place. In

other words, it doesn’t seem to matter whether early twentieth century tourists to

Vermont came from New York or Boston; what matters is their outlook and behavior.

Until the mid-twentieth century, Vermont remained more difficult to reach than

New Hampshire, particularly by public transportation. (Passenger railroads spanned

New Hampshire well before they did Vermont.) These early differences in

accessibility did influence the subsequent development of both states, but this,

again, entails consideration of more than mere geography and infrastructure. State

residents and legislatures played important roles in the development of their

respective transportation and tourist infrastructures.

We also explored the possibility that topographical and geological differences

might matter in some way—Vermont’s lower, lusher Green Mountains may have

fostered more farming, more summer tourism, and more skiing than New

3

Alternatively, one might imagine some exogenous change in out-of-state residents’ preferences that

suddenly makes a given place more appealing than before, though this seems unlikely without

contemporaneous endogenous change in the place in question.

4

Census data from 2000 show both states converging toward similar percentages of their workforce in

each of three main categories—“professional, managerial, clerical, and service occupations,”“manual,

industrial, and craft occupations,” and “farm-related occupations”—for example.

126 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

Hampshire’s tall, rugged White Mountains. These differences, too, seem neither

necessary nor sufficient to the outcome studied here.

In summary, we arrived at our particular explanation of the divergence in Vermont

and New Hampshire’s place reputations only after exploring the tenability of every

other explanation we could think of. None seemed to capture the unexpected and

widely divergent characters of these two places as well as the model presented here.

Below, we offer narrative histories of the three types of transformation

highlighted in our account: Vermont ’s shift from a largely Rep ublican, libertarian

polity to one well to the “left” of the American mainstr eam; Vermont’s emerging

reputation as a haven for intellectuals, artists, bohemians, and nature-lovers; and

Vermont’s changing economy and infrastructure, from a state full of isolated family

farms to one densely populated with vacati on homes, recreational facilities, and

college towns. We demonstrate and explain how similar transformations did not

occur in neighboring New Hampshire. Every effort has been made to find

comparative longitudinal data to document each trend.

Data: documenting political change

Politics is perhaps the most striking realm in which Vermont has changed but New

Hampshire has not. Republicans controlled all of Vermont’s statewide offices from

1854 through 1958, the longest single party control in American history (Hand

2002). Yet, as early as the 1920s, Vermont politicians broke with state tradition and

started (albeit gradually) on a politically progressive path toward increased

government spending and environmental protections (Bryan 1984; Judd 1979;

Sherman 2000). Over the same period, New Hampshire stood fast by a libertarian

agenda of limited taxation, minimal state spending, and political skepticism (Associated

Press 2003; Winters 1980, 1984). We document here the scope and timing of this

switch. It is important to note from the outset that Vermont’s shift from Republican to

Democratic Party dominance preceded t he onset of major in-migration. The

Democrats were well in the ascendance before 1960, when Vermont’s population

began a rapid period of growth after decades of relative stagnation.

“Branding”

(temporary residents + state agencies)

Political Transformation

(residents + politicians)

Idio-Cultural Migration

(residents

non-residents)

1890 1927 1955 1964 1980

Fig. 1 Schematic of casual sequence: VT, 1890–1980

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 127127

Empirically documenting these contrasting political trajectories presents some

interesting challenges. Voting in presidential and gubernatorial elections is often driven

by idiosyncrasies related to the candidates themselves. New Hampshire’slongstanding

position as “first in the nation” for presidential primaries further complicates such data.

Vermont and New Hampshire also have among the smallest Congressional delegations

in Washington, with only one and two representatives serving them, respectively.

National public opinion surveys abound, but such surveys typically have too few cases

to conduct comparative research at the state level, particularly for ‘tiny’ states like

Vermont and New Hampshire. No state-specific surveys have been administered with

sufficient regularity to make longitudinal analysis possible.

5

Another feasible source for

assessing political change, voter registration, is also not useful in our case, because

Vermont does not register voters by party.

The results of elections for statewide office are what we find to be the most revealing

information about long- and short-term political trends in both of these states. Data on

party representation in the state legislatures were gathered for New Hampshire, 1937–

2000 (Council on State Governments 1900–2000) and 1900–2000 for Vermont (Hand

2002; Council on State Governments 1900–2000).

6

We focus specifically on the lower

chambers of both legislatures, both of which are among the largest in the nation. Party

distribution in these lower chambers seems a subtle and incremental barometer of

political culture in the two states over a fairly substantial period of time.

Figures 2 and 3 review the partisan composition of each state’s lower chamber.

Figure 2 serves to show how powerful the Republican Party was in Vermont early in

the twentieth century–between 80% and 90% of the House was controlled by

Republicans prior to the 1950s. Since 1956, however, Vermont Democrats made

significant gains, reaching parity in the 1980s and pulling ahead for much of the

1990s. In the massive New Hampshire House of Representatives (Fig. 3), by contrast,

the Democrats never achieved a competitive position, despite some gains in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, Republicans retook these seats and strengthened their position, leaving

them in a stronger position than they had been throughout the twentieth century. In the

Vermont house, Democrats overcame a deficit of nearly 80% to reach competitiveness

and eventually to gain control, while over the same period New Hampshire Democrats

lost ground. This shift from Republican to Democratic Party dominance happened in a

number of other Northeastern states after the Second World War—Massachusetts and

Rhode Island, for example—but only in Vermont was this shift accompanied by such

radical transformation of public opinion and political culture (Mayhew 1967;Mileur

1997). It is possible that Vermont’s earlier brand of Republicanism already differed

from that elsewhere in New England, but we have not found strong evidence of this

fact. More detailed analyses, however, might turn up important, albeit subtle, variants

in early New England Republicanism.

Data on the prevalence and tolerance of same-sex couples has been seen by some

as a reasonable indicator of contemporary political sentiment (e.g., Florida 2002,

5

New Hampshire does have a quarterly survey of public opinion administered by the University of New

Hampshire, the Granite State Poll, but the survey has only been in existence for a dozen years and its raw

data are only available since 2000. Despite longstanding talk of establishing a similar poll in Vermont,

there appear to be no concrete plans to do so at this time.

6

We analyzed gubernatorial election and party primary data but found them far too sensitive to candidate-

specific perturbations to be of much use, trendwise.

128 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

2005). Data from the 2000 Census (Simmons and O’Connell 2003) indicate that

Vermont has the nation’s fifth highest numbe r of “same-sex unmarried partner”

households of all states (including the District of Columbia), whereas New

Hampshire ranks a middling 27th.

7

However, both states’ homosexual populations

appear to contain high proportions of lesbian couples by national standards. As of

summer, 2009, furthermore, both states were in the vanguard of states providing

means for same-sex couples to marry legally.

To fill in the absence of comparable state-level public opinion polls, political

scientists in recent years have developed alternatives by pooling multiple years of

national opinion surveys to generate sufficiently large state samples, as well as by

constructing measures through interest group rating scores. These measures offer a

somewhat less dramatic image of the political differences between New Hampshire

and Vermont, but they consistently point to Vermont as significantly more liberal

than New Hampshire in the near present.

Drawing on 1976–1988 data gathered by CBS/New York Times, Erikson et al.

(1993) construct a sample sufficient for cross-sectional comparison of all fifty states.

By this account, Vermont residents are about 3 percentage points more liberal and

five percentage points less conservative (and thus 2% less moderate overall) than

New Hampshire residents–a small if not negligible difference. Erikson et al. (1993)

also regress a series of demographic, regional, and dummy variables on individual

level partisanship and ideology measures to assess the “effect” of residing in a

particular state. They find that New Hampshire, relative to its demography, has the

most “conservatizing” effect of all states in the country ceteris paribus and that the

effect of residing in Vermont is about 7 percentage points more “liberalizing” on

partisanship and 4.3 percentage points more liberalizing on political ideology. These

may appear to be small effects, but they are about equal to the effects of gender

differences once other demographic factors are controlled. The story that emerges

from this dataset, in short, is that over the years 1976 – 1988, Vermont residents were

more liberal and Democratic than their New Hampshire counterparts by a small but

statistically signific ant margin.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1890 1910 1930 1950 1970 1990 2010

Republican Democrat Other Unrepresented

Fig. 2 Composition of

Vermont house 1900–2005

(150–248 seats)

7

These data precede the legalization of gay marriage in either state. The sexual preference of members of

these households is only interpolated from demographic information given in Census returns, however; it

should be read with some skepticism.

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 129129

Berry et al. (1998) have generated an over-time estimate of citizen and state

ideology by pooling interest group ratings of congressional incumbents and

challengers and weighting these ratings by electoral support. Off years are linearly

assigned and the full trends are weighted differently to reflect conceptually distinct

“citizen ideology” and “state ideology.” The advantage of this measure is that it

covers all years from 1960, when interest group ratings were first published, to 2002,

and has been show n to be an improvement over more conventional measures of

public opinion through a series of replications of prominent studies.

Figure 4 displays the citizen ideology of Vermont and New Hampshire for the

years 1960–2002, extracted from the Berry et al. dataset. We have chosen to focus

on their measure of “citizen ideology,” as it is a closer fit to our concern with public

opinion and politic al culture than thei r measure of “state ideology,” which seeks to

represent the ideology of each state government. A higher ideology score indicates

greater liberalism.

The two trend lines indicate a gradual, if wavering, shift toward liberalism for

Vermont and an equally wavering trend toward conservatism for New Hampshire.

The dashed line captures the growing ideological gap between the states and it

provides the best evidence of polarization in opinion between the states. In terms of

state-by-state ranks, Vermont emerges as the most liberal state in the country by

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

Republican Democrat Other Unrepresented

Fig. 3 Composi tion of New

Hampshire house 1937–2006

(399–433 seats)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002

VT citizen ideology NH citizen ideology Dif between VT and NH

Fig. 4 Vermon t a nd N ew

Hampshire citizen ideology,

1960–2002. (Source: Berry et al.

1998)

130 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

2002, when New Hampshire ranks well below “neutral” at 37th. Note, however, that

Vermont is already more liberal than New Hampshire in 1960, when Vermont’s

population boom begins. Figur e 4 also su ggests that the overall ideological

difference between Vermont and New Hampshire has approximately doubled from

the 1960s to the 1990s, the result, we presume, of an influx of new ‘liberal’ voters to

Vermont as a result of idio-cultural migration.

We will turn shortly to the task of explaining how and why we think this

occurred. But first, what of the less tangible features of socio-cultural change?

Data: documenting socio-cult ural change

Describing the socio-cultural transformation of modern-day Vermont is as difficult as

explaining it. There is no simple “metric” of socio-cultural change; we experimented

with many. Given that much longitudinal data come in the form of population and

economic trends, we looked first to those, hoping to find indirect evidence of

cultural change. Census data on over-time trends in the percentage of the population

with college degrees reveal no noticeable difference between New Hampshire and

Vermont, and though both have better educated populations than the national

average, growth rates are about the same (data available upon request). Household

income is rather different across these two states: the 3-year-average median for

2003–2005 was $58,233 in New Hampshire but only $48,502 in Vermont, evidence

of a fairly big gap in average prosperity.

8

This is consistent with the fact that an

increasing proportion of New Hampshire’s population consists of affluent com-

muters who work in the metro-Boston area (Wangsness 2007). Vermont has many

affluent citizens as well, but a large percentage appear to reside there only part time;

presumably, the census counts many, if not all of them in their state of primary

residence. Inter state differences in these measures do not change greatly over time,

however.

Our efforts to track in detail what kinds of people have been moving in and out of

each state were also stymied by a lack of adequate data. In-state and out-state

migration data are available, but they say little about what types of people are

moving and why. Cohort-specific socio-demographic effects are also masked.

Overall, census data on in-state migration since 1900 show a consistently higher

percentage of new residents (i.e., residents born out of state) in New Hampshire than

Vermont (Fig. 5). This should lead us to expect greater cultural change in the former

than the latter. Since this is not what we observe, we conclude that this basic

migration data, too, does not adequately address the phenomenon at hand.

Although census data on occupational distrib utions in each state since 1940 reveal

Vermont’s economy to have been more agriculturally-based than New Hampshire’s,

over time, the occupational structure of the two states has converged with respect to

three major categories of employment: professional, managerial, clerical, and service

occupations; manual, industrial, craft occupations; and farm-related occupations (US

8

Data from US Census Bureau website, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/histinc/h08b.html June

22, 2007. The data are derived from the 2004 to 2006 “Annual Social and Economic Supplements” of the

Current Population Survey (CPS).

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 131131

Census). We also examined historical data on the numbe r of working farms in each

state over time (Carter et al. 2006), another area in which these two states might have

diverged, economical ly and culturally speaking. Vermont consistently has more

farms than New Hampshire, but the relative change in farm-ownership is about the

same in each state, dropping steadily from 1880 through 1970 and then picking up

again slightly in the 1990s. On the other hand, on-line data referencing organic

markets and producers of o rganic goods show some important contemporary

differences (Fig. 6):

An on-line directory of “eco-friendly and holistic health products,” Green-

People.org, lists 20 “Coops/health food stores” in New Hampshire and 24 in

Verm ont .

9

Adjusted for 2005 state population size, that amounts to approximately

one store per 65,497 New Hampshire residents, as opposed to one per 25,960

Vermonters. The same website lists a variety of related retail outlets: it lists 26

“vegetarian restaurants” in New Hampshire and 21 in Vermont, or one per 50,382

and one per 29,669 residents respectively. It lists five stores selling eco-friendly

“hemp” products in New Hampshire and six in Vermont, or one per 261,988 and

one per 103,841 residents respectively. Similarly, the O rganic Trade Association’s

website lists 142 “retailers” of “organi c goods” in New Hampshire and 141 in

Vermont, another large disparity considering New Hampshire’s substantially larger

population.

10

Another archetypal Vermont consumer item is Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. Ben

&Jerry’s first opened in 1978 in Burlington, Vermont, and made a name for

itself by embracing strict environmental standards and leftist political causes. It

has since come to be a national symbol of Vermont’s ‘hippie’ roots, selling

flavors such as ‘Cherry Garcia,’ after the Grateful Dead singer Jerry Garcia, and

‘Phish Food,’ after the jam band Phish. As Thomas Naylor, a non-native

Vermo nte r and le ad er of the “Green Mountain Independence Movement,” recently

told a reporter from Slate.com (Levin 2009), Ben & Jerry’sis“ not in the ice cream

business. They [are] in the Vermont business.” Dairy Queen, by contrast, opened

its first store in 1940 in Joliet, Illinois and brands itself as an American tradition—

9

Site accessed June 22, 2007. 2005 state population figures are from the US Census Bureau. New

Hampshire population=1,309,940, Vermont=623,050.

10

<www.theorganicpages.com> accessed June 22, 2007.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Vermont New Hampshire United States

Fig. 5 % of US native

population born out of

state, 1900–2000

(Source: US Census)

132 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

like apple pie, only colder. The Ben & Jerry’s ice cream company reports eight

Vermont stores and six in New Hampshire, a fairly large difference in per capita

terms.

11

By contrast, there are 7 Dairy Queens in New Hampshire but not one in

the entire state of Vermont.

12

This may indicate a radical difference in ice cream

tastes, price-points (Ben & Jerry’s is considerably more expensive t han Dairy

Queen), or simply a reactive marketing strategy on the part of Dairy Queen with

respect to Ben Jerry’s home-state advantage in Vermont. On the other hand, Ben &

Jerry’s explicitly markets itself as an eco-friendly Vermont-based business, whereas

Dairy Queen, a far older company, is stereotypically associated with old-fashioned,

middle-American tastes and values.

A clearer cultural indicator of Vermont/New Hampshire differences, perhaps, is

the prevalence of Birkenstock sandal dealers—Birkenstocks are clunky sandals

stereotypically associated with self-proclaimed “hippies.” Birkenstock USA lists 17

dealers in Vermont and 19 in New Hampshire, or one per 36,650 and one per 77,055

residents respectively.

13

Conversely, Vermont is home to two licensed Harley-

Davidson motorcycle dealers; New Hampshire 10.

14

Contrary to Vermont’s “leftist,” hippie image, however, the two states have the

same number of Smith & Wesson gun dealerships per capita.

15

Hunting is very

popular in Vermont, and its gun laws are extremely lenient, including no ban on

carrying concealed, loaded weapons in public. This is exactly why we stress the

image versus the reality of place reputations—stereotypes about Vermont are just

that, though, through idio-cultural migration, they have tended to become self-

perpetuating over time.

While these comparative data on consumer outlets as markers of distinct socio-

economic and socio-cultural milieu provide neither a balanced nor representative

sample of lifestyle-purveying outlets, the overall sense one gleans is this: On the one

15

Store locator accessed at <www.smith-wesson.com> on June 29, 2007. This may not be representative

of gun-ownership as a whole; on-line listings of gun stores are sociological quicksand, and most major

gun manufacturers do not list dealer information.

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

Outlets per 1,000 residents (2005 pop.)

B

i

r

k

e

n

s

t

o

c

k

D

e

a

l

e

rs

B

e

n

&

J

e

rry

'

s

S

t

o

r

e

s

D

a

i

r

y

Q

u

e

e

n

s

"

H

e

m

p

"Pro

d

u

c

t

R

e

t

a

i

l

e

r

s

"

Ve

g

e

ta

r

i

a

n

"R

e

s

t

a

u

r

a

n

t

s

"

C

o

o

p

s

/

H

e

a

l

t

h

Fo

o

d

"St.

.

.

H

a

rl

e

y

-D

a

v

i

d

s

o

n

d

e

a

l

e

r

s

S

m

i

t

h

&

W

e

s

s

o

n

d

e

a

l

e

r

s

Vermont New Hampshire

Fig. 6 Various socio-cultural

indicators, 2007

14

Store locator accessed at <www.harley-davidson.com> on June 29, 2007.

13

Store locator accessed at <www.birkenstockusa.com> on June 22, 2007.

12

Store locator accessed at <www.dairyqueen.com> on June 29, 2007.

11

Store locator accessed at <www.benjerry.com> on June 22, 2007.

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 133133

hand, both states participate in various aspects of contemporary “new age” or “eco”-

culture—Ben & Jerry’s, Birkenstocks, vegetarian restaurants, etc.—but Vermont

clearly dominates in this respect. On the other hand, both states are also home to

stereotypically “down home” traditional lifestyle outlets, such as gun shops and

Harley dealers, and the percentages are even similar in the case of Smith & Wesson

dealers; but New Hampshire clearly dominates in this respect. Overall, we submit,

the culture or “feel” of these two states is different. Both are largely rural,

predominantly white states, but, on balance, the aforementioned data appear to

confirm our notion that Vermont and New Hampshire have rather different “place

characters” today.

Informal interviews with a variety of residents, former-residents, realtors, and

academics confirmed these observations about the states at present.

16

We spoke to a

realtor in Brattleboro, VT—a town very near the New Ham pshire border—who said

that there is a clear difference between house-hunters looking on either side of the

border. Those looking for homes in Brattleboro are often attracted by its vibrant arts

scene, for example. Political differences, too, draw prospective home-buyers to

Vermont, particularly policies like Vermont’s statewide regulations against billboard

signage on highways and local regulations that block big-box stores and restaurant

chains. Realtors also said that some Vermont home-buyers were attracted by what

they saw to be an active, participatory political culture in Brattleboro, particularly its

tradition of annual town meetings. One realtor proudly described how Wal-Mart was

denied a permit to build in Brattleboro.

Farther west, in Bennington, Vermont, a realtor said that “quality of life” factors

were the major draw for homebuyers: natural, well-preserved forest- and farmland; a

quaint village center boasting a lively arts and culture scene; a few restaurants and

retail shops; beautiful, historic real estate; proximity to New York and Boston; streets

so safe that locals regularly leave their keys in their cars, unlocked. In contrast, a

New Hampshire-based realtor mentioned that home-shoppers there tend to be

looking primarily at price and taxes in considering where to buy. He mentioned the

extensive efforts the town of Keene, New Hampshire was making to attract big retail

“chain” stores to the area, something presumably enticing to would-be movers.

Vermont, by contrast, has experienced repeated protests over efforts to build big-box

stores there.

Our realtor respondents told us that some Vermont home-shoppers absolutely

refuse to consider homes just across the border, in New Hampshire. These shoppers

generally perceive New Hampshire to be more corporate, more commercial, and less

aesthetically pleasing than Vermont.

But not everyone who moves to Vermont actually intends to move there,

interestingly. Two different Vermont residents (one a former-resident) said that they

were merely “passing through” when Vermont first caught their attention. While

16

These were short, informal interviews largely conducted via telephone. These results are not in any way

intended to be “representative” but are merely illustrative examples of first-hand statements consistent

with our own hypotheses and observations. Since the length and extent of interviews varied greatly—

many were based on “cold-calls”—it is difficult to name and codify them as a whole. Quotes are not

verbatim; some paraphrasing and re-construction is employed here, though nothing that would distort

speakers’ intended meaning.

134 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

hitchhiking from Quebec to Cape Cod in the mid-1970s, one informant experienced

a life-changing stop at a “hippie house” in Vermont. “The girls, the dope, the

mountains, great music, skinny dipping in the lake.... Vermont felt clean and pure,

and life felt really close,” he said, describing how he impulsively moved there and

“did all that hippie stuff” for the next 5 years. It was not politics, per se, that drew

him to Vermont but something more like its unique ethos, milieu, and sense of

community. “VT was, for me, beautiful and refined—like gentlemen farming. NH

felt a bit crude, more rugged, a little less smart, a little less intelligent.” Replicated up

and down the Connecticut River, these micro-processes of dist inction concatenate

into the vast idio-cultural divergence we observe between the two states.

To collect more data on the image each state currently projects (as opposed to

how migrants and home-shoppers perceive it at present), we also consulted several

types of contemporary tourist literature from each state: each official state website,

for example, and Vermont Life and New Hampshire magazines, major statewide

periodicals. We also reviewed all New York Times articles referencing Vermont or

New Hampshire between 1851 and 1980. The differences were rather striking.

The content of a leading periodical, Vermont Life magazine, mirrors many of the

things we heard realtors and residents say about contemporary Vermont. Founded by

the state government in 1946 (but privatized in 1969), “Every issue of Vermont Life

magazine celebrates the unique heritage, countryside, traditions, and people of

Vermont and explores issues of contemporary interest to Vermonters and visi tors of

the state.” Vermont Life bills itself as “the state’s official magazine, an insider’s guide

to the secret places and special character of the region.” In addition to regular

columns on dining, outdoor recreation, and weekend getaways, the Spring 2008

edition featured stories on “Vermont’s love affair with the written word” and the

Green Mountain Film Festival.

17

New Hampshire Magazine touts itself as “the essential guide to living in the

Granite State.” It seems to run stories of a more pragmatic bent than those in

Vermont Life. The April 2008 edition of New Hampshire Magazine features articles

on “designer windows” and New Hampshire’s “top doctors,” for example. Its target

audience seems to be people already committed to living in New Hampshire, as

opposed to Vermont Life’s more tourist-oriented approach. Although we could not

access back issues of each periodical to more systematically test these observations,

Vermont Life generally seems more focused on cultural amenities, and less on

pragmatic goods and services, than New Hampshire Magazine.

18

Both state websites—VT.gov and NH.gov—provide a bevy of useful information

to residents, contractors, tourists, and would-be residents.

19

They do it in subtly

different ways, however. Both provide colorful pictures of their governors and

nicely-shot, colorful landscape photos—Vermont’s of an unsown meadow, New

Hampshire’s a covered-bridge—but only VT.gov includes secti ons like “Share a

Vermont Moment,” a moderated forum for tourists and residents to share happy

stories like, “I was fortunate enough to live in Vermo nt for a year from ‘06 to ‘07 ...

and was overwhelmed by the beauty and peaceful lifestyle, but more importantly, by

19

Both sites accessed April 10, 2008.

18

<www.nhmagazine.com> accessed April 10, 2008.

17

<www.vermontlife.com> accessed March 1, 2008 and April 10, 2008.

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 135135

the friendliness and genuine generosity of spirit of everyone I came into contact

with. Don’t ever change!” After another out-of-state contributor outlines her plans to

move to Vermont after retirement, she names a few of her favorite things about it:

“Nothing’s better than Cabot cheese, maple candy, apple cider from Cold Hollow

Cider Mill in Waterbury, Magic Hat [beer], and Nectars [restaurant and bar] in

Burlington.” Some of these are the same items originally promoted by the state in

the late nineteenth century to empha size its pasto ral charm . “[T]he people, the

lifestyle, and the land.... We loved it all!!!” the contributor concludes.

NH.gov is generally more staid in appearance and less emphatic about the cultural

amenities of the “Granite state.” There is virtually no tourist information on the NH.

gov homepage. It gives prominence of place to the most current “Homeland Security

Advisory”—something VT.gov never mentions—and contains featured links to the

New Hampshire Business Resource Center, a vendor-resource center (“Doing

Business with NH State Government”), and information about in-state “job training

grants.” VT.gov contains none of these links on its homepage and bears a simpler,

less cluttered design overall.

To the (limited) extent that these sources reveal something a bout the place

character of states, Vermont and New Hampshire broadcast rather different images of

themselves to both in-state residents and out-of-state tourists and migrants. In the

terms of contemporary cultural sociology, the symbolic boundaries delineating each

state are strong and evident, although not very internally consistent (cf. Herzfeld

1992; Lamont and Molnar 2002).

Creating opportunity structures: trajectories of continuity and change

The cultural transformation of Vermont

As early as the 1890s, state-sponsored programs throughout Northern New England

began promoting the region’s rural vacationlands. However, “… it was in Vermont, New

England’s most rural state, that the pastoral vacation outdistanced all other kinds of

tourism,” writes historian Dona Brown of this period (1995, p. 143). Toward the end of

the nineteenth century, the Vermont Board of Agriculture waged a vigorous campaign

to convince local farmers to sell “authentic” crops and made-goods to tourists. In

1893, for example, it published Vermont: A Glimpse of its Scenery and Industries

(Spear 1893), a guidebook that appears to have been written to dispel the belief that

Ver mon t’s charm and natural beauty were no more. “The hills have lost none of their

former freshness,” notes the author in the introduction (Spear 1893,p.3),“nor the

valleys their peculiar charm. The water is as pure and sparkling, the air still laden with

health and vigor, the winters as cold and the summers as delightful as ever....” The

volume documents Vermont’s beautiful landscapes, noble populace, and unsurpassed

agricultural products. It also boasts of the state’s burgeoning manufacturing and

mining sectors. “At a time when nationally known brand names were beginning to

compete with local products,” writes Brown (1995: 145), “the state itself, in

cooperation with producers’ associations like the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’

Market and the Vermont Dairymen’s Association, was doing its best to become a kind

of brand name, a guarantee for quality and ‘authenticity’ of the product.”

136 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

Unlike rival tourist destinations, such as Maine and New Hampshire, which

emphasized their rugged terrain and hearty founders, Vermont presented a softer

image of itself, one of a bucolic motherland beckoning its flock, “protective, gentle,

and nurturing” (Brown 1995: 147). Vermont’s mount ains were referred to in tourist

literature as the “Green Hills” and its verdant fields and healthful air were extolled.

Vermont farmers were also discouraged from boasting to tourists of the

“modernization” of their farms. The Vermont Board of Agr iculture went so far as

to instruct local farmers about the kinds of food that summer boarders expected; not

the starchy, fatty meals farmers actually ate but fresh produce, dairy, and baked

goods like the tourists imagined they ate. Locals sometimes resented this

overbearing, unrealistic vision of farm life, but many profited from it noneth eless.

Although this would appear to mark the beginning of Vermont’s internal place

transformation, there is little evidence that this early state tourism policy was necessary

or sufficient to bring about the subsequent place transformations of the twentieth

century. For the time being, the state remained a rural backwater, losing more citizens

than it gained (Harrison 2006). The tourist industry, too, remained relatively small

despite the prescient plans of the state Board of Agriculture. Idio-cultural migration

was still a long way off, as was anything resembling a political realignment.

Over time, longer stays and the purchase (as opposed to rental) of vacation homes

increased outsiders’ exposure and commitment to Vermont. It also fostered chain-

migration to the state. By the 1930s, notes Harrison (2006, pp. 51–52), “Vermont’s

summer homes [had become] central to the reworking of rural Vermont, emerging as

potent symbols and powerful agents in the transformation of Vermont property from

work to leisure.” Some locals objected to this “sale” of their state, arguing that it was

changing its culture and ethos forever. Nonetheless, government organizations like

the Vermont State Board of Agriculture (VBSA) and the Vermo nt Burea u of

Publicity continued to market the state to would-be purchasers of vacation homes. In

fact, notes Harrison (2006: 61), beginning in the 1890s, the VBSA “published a

series of annual advertising books, each of which was distributed by the thousands to

potential [home] buyers inside and outside the state.” Out-of-state home buyers, they

argued, would bring valuable money and human and social capital to the state,

which had long suffered from a moribund economy and withering out-migration.

Vermont’s contemporary reputation as a bohemian, “earthy” paradise was also

bolstered greatly in the 1930s. This owes much to the efforts of a single woman:

Dorothy Canfield. Canfield epitomized a new middle-class sensibility in the early

twentieth century United States. She was a long-time member of the Book of the

Month Club selection committee and helped bring the Montessori teaching method

to the United States. Although born and raised in the Midwest, she had roots in

Vermont and spent much of her adult life there, where she authored numerous books

about “the good life” awaiting upper-middle-class folks who moved to Vermont. In

her 1932 book, Vermont Summer Homes, published by the Vermont Bureau of

Publicity, Canfield bends over backward to assure readers that “those who earn their

living by a professionally trained use of their brains”,—“those who are doctors,

lawyers, musicians, writers, artists,” e.g.,—are just as welcome to summer in

Vermont as those “

superior interesting families with character, cultivation, good

breeding and also plenty of money....” (Note: her appeal is only to summer tourists;

large-scale idio-cultural migration has yet to begin in Vermont.)

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 137137

Vermont Summer Homes includes pictures of the farmhouses of professors,

musicians, and artists who summer in Vermont and includes a quote from author

Sinclair Lewis, who, in explaining his choice to buy a home in Vermont, testifies, “I

like Vermont because it is quiet, because you have a population that is solid and not

driven mad by the American mania which considers a town of four thousand twice

as good as a town of two thousand....” Lewis, author of anti-est ablishmentarian

classics such as Babbitt, Main Street, and Elmer Gantry, adds, “I can see coming to

Vermont people with long vacations who will establish estates here ... doctors,

writers, college professors.”

Canfield, too, pushes this theme hard, stressing the unique cultural values of

Vermont’s finer summer folk: “We approve of and are proud of many of your ways

that some Americans find odd—such as the fact that you prefer to buy books and

spend your money on educating the children rather than to buy ultra chic clothes and

expensive cars. That makes us feel natural and at home with you.... You value

leisurely philosophic talk and so do we.” Such impressions of Vermont cultural life

are mirrored in other publications, such as Daniel Leavens Cady’s Rhymes of

Vermont Rural Life, the epigraph of which includes the following description of rural

Vermont by the author (1919, p. 6): “Bucolic yet academic, her villages the beauty

spots of New England, with entire streets of homes in every one of which dwells

some person familiar with Virgil and on friendly terms with Horace. As her

mountains look down upon the storms of earth, so do her robust people look down

upon the frivolities of mankind....”

Despite the fact that Vermont publicists like Cady and Canfield portrayed it as a

rural paradise forgotten by time, Vermont had both heavy industry—textile mills,

sawmills, factories, and the negative externalities that come with it: noise, air, and

water pollution (Harrison 2006; Meeks 1986; Sherman 2000; Spear 1893). Early

twentieth century Vermont was far from an Edenic paradise, in other words, but its

most vocal spokespeople boasted of its pastoral charm nonetheless. The same year as

the publication of Dorothy Canfield’s Vermont idyll, for example, a bohemian

couple from New York City, Helen and Scott Nearing, moved to Vermont and began

an experience that would help launch a national cultural revolution; what many later

termed the “Back to the Land” movement (Gould 2005; Trubek 2008). Before

discovering Vermont, the Nearings lived as artists in New York City. Like many

subsequent Vermont migrants, they coveted Vermont’s beautiful landscapes and

simple live-and-let-live ideology. They moved to Vermont in 1932, and after

20 years experimenting with self-sustaining, quasi-organic agriculture in Vermont,

they published what would become the “Bible” of the back-to-the-land movement:

Living The Good Life (1954).

The Nearings themselves moved on to Maine in 1952, yet their book helped

jump-start the commune movement in Vermont in the 1960s (Fairfield 1971; Frazier

2002; Nearing and Nearing 1979; Veysey 1973). Nowher e else in New England did

so large a density of “communards” and environmental activists congregate, as is

shown in Fig. 7

. Many, if not most of these communes eventually folded or failed,

but they left behind a bevy of new local institutions: food co-ops, vegetarian

restaurants, organic markets, coffee shops, and the like (Sherman 2000). These local

institutions and communities became “magnets” that drew further migrants to the

state. They also helped “brand” Vermont as a bastion of American counter-culture.

138 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

Another important factor shaping the gravity of Vermont’s new cultural image

was the founding of a number of small “experimental” colleges there in the mid-

twentieth century. The founding of colleges like Goddard (est. 1938), Bennington

(1931), Marlboro (1946), and Windham (1951–1978), in addition to Vermont’s older

schools—Middlebury (1800), Green Mountain (1834), and the University of

Vermont (1791)—helped draw artists, radicals, writers, and students to Vermont,

as well as build its reputation as a hospitable place for independent thought and

leftist political activism. This bolstered the cultural life and economy of numerous

Vermont towns. New Hampshire lacked (and continues to lack) comparable

institutions, at least not in anything close to this density.

Cultural continuity in New Hampshire

The case we are trying to make here is that the “place character” of twentieth century

Vermont changed markedly, whereas its neighbor, New Hampshire, changed, but

only in ways that maintai ned its original trajectory, more or less keeping pace with

wider changes in American society (Peirce 1972; Lockhard 1959; Winters 1984;AP

2003). Several major features of New Hampshire ’s cultural landscape helped

preserve its reputation as a rugged individualist place modeled in a libertarian vein.

A systematic comparison of state guidebooks and tourist pamphlets was not

possible owing to the absence of comprehensive collections of such documents, but

we did find at least one New Hampshire counterpart to Dorothy Canfield’s 1932

book: A 1930s pamphlet, Inviting You to Visit and To Live in the Monadnock

Region: ‘Land of New Hampshire Charm,’ written by John Coffin and published by

a group called the Monadnock Region Associates in the 1930s.

20

Although it shares

with Canfield’s text the come-hither tone of mid-century boosterism—“The Folks of

The Monadnock Region Want YOU For a Neighbor,” reads the opening page—it

seems intent on appealing to a different type of consumer than Canfield’s Vermont

aims for. There is a distinct emphasis on Southern New Hampshire’s accessibility to

Boston, its modern conveniences (electricity, for example), and its ample incentives

for businesses. “If you are a manufacturer, have you ever thought of the advantages

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Vermont

New Hampshire

Massachusetts Maine Connecticut Rhode Island

Fig. 7 Number of communes

initiated, 1965–1975, per

100,000 residents in 1970

(Source: Miller 1999)

20

No date is provided anywhere on the manuscript, though library archivists date it to this decade.

Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154 139139

of moving your business to a small town?” reads one caption. “Or if you are retired,

have you ever thought of spending your leisure years where they can be enjoyed? Or

if you are a busin essman, wouldn’t you prefer the easy-going, yet progressive

methods of the modern small town?”

This is a stark contrast from the back-t o-the-land hauteur of Canfield’s Vermont.

Canfield discusses economics quite frequently, but only in terms of the anti-

bourgeois values of Vermonters (cf. Lamont 1992). The New Hampshire pamphlet,

in contrast, is at pains to flatter bourgeois values: “[B]ear in mind that the low tax

rate on Monadnock Region property is not the least of its benefits, ” it boasts. New

Hampshire’s target audience appears not to be urban sophisticates but pragmatic

business owners and retirees looking for a cheap place to live the “good” life. So

concludes the Monadnock introduction: “Whatever your pursuit—industry, com-

merce, agriculture, or rest, live in our region and be happy!”

Overlaying this image of neo-pastoral New Hampshire is a stress on modern

amentities and its proximity to major cities. “Here you find scenic splendour [sic] at

every hand, backed up by modern needs. Wide-surfaced concrete roads speed you

quickly back to Boston, while local firemen and state and local police have guarded

your interests while you were away. Pure water, seasonal vegetables fresh from

nearby gardens, modernly managed stores at your service, good schools, economical

living costs and the convenience of electricity in all but three towns are other

advantages of the region.”

Of course, we have no way of knowing who or how many people read these

respective brochures; we do not intend to over-emphasize their causal impact on the

future peopling of Vermont or New Hampshire. Nevertheless, there are other, better

documented differences in the two states’ tourist industries that confirm this

observation.

Two travel pieces published in 1955 in the Sunday New York Times by the same

author, Mitchell Goodman, reflect the longstanding differences in Vermont and New

Hampshire’s approaches to tourism: The New Hampshire piece (Goodman 1955a)

says, “this state is, quite consciously and deliberately, in the vacation business. They

make a scien ce and an industry of it, mix well with some Yankee ingenuity, and

produce a package that for neatness, compactness and high contrasts is not easily

matched this side of Switzerland.” Among other things, Goodman’s New Hampshire

piece extols the state ’s “big-time race track” and 56 golf courses. In contrast, the

Vermont piece (Goodman 1955b), published several weeks later, praises the revival

of small town fairs in rural Vermont, especially that in Norwich, “where the homely

virtues of rural life appear at their best.” Describing the ordinary rural folk behind

the small Vermont town fair, Goodman notes, “They work out of a sense of

community, for the pleasure of it; there is no money in it.” Describing the

participants in the ensuing parade, Goodman writes, “They are down from the hills

and the villages where tourism and television have made little impression.” He also

notes, “There are no side-shows, no bathing beauties, no barkers; what there is is

familiar, and enough.

” This piece is accompanied by a listing o f similar town fairs

across the country, but the feature focuses on Vermont and clearly presents it as the

epitome of a dying way of life.

Long before the automobile made Vermont accessible to motorists, New

Hampshire was well-networked via railroad; it was filled with tourist-friendly

140 Theor Soc (2011) 40:119–154

express and connector routes. In comparison, Vermont’s turn of the century railway

system was mostly oriented toward freight, and the state resisted highway

improvements for decades (Bryan 1974; Harrison 2006). Not surprisingly, then, a

large summer tourist industry sprouted in New Hampshire (but not in Vermont) to

take advantage of its proximity to working and lower-middle class communities in

places like Massachusetts and Quebec. A brochure issued by the Concord and

Montreal Railroad (1892) proudly boasts of its regular service to the summer

attractions of New Hampshire, for example, and it also lists summer resorts

accessible by rail. In the rapidly changi ng econom y of late nineteenth century New

England, New Hampshire’s tourist industry represented a perfect symbiosis between

accessibility, affordability, and variety. In turn, this accessibility to “mainstream ”

summer tourists appears to have allowed New Hampshire-ites to profit from tourism

without changing much else in the state. Like Maine or old Nantucket, New

Hampshire could open its elf to outsiders in the tourist season and then return to its

old self the rest of the year. Vermont, by contrast, had to work harder to attract

tourists and seemingly had to change more about itself in order to attract those who

might be interested in coming.

Vermont had a small tourist industry by the 1890s, as shown above, but it did

not really come into its own until the 1930s (Brown 1995;Sherman2000). From

the aforementioned comparative tourist literature, it would appear that many

would-be migrants would have seen New Hampshire as over-populated with noisy

attractions, urban amenities, and perhaps most importantly, unsophisticated

working class vacationers from New England’s nea rb y cities and mi ll towns .

Verm ont ’s “cultural distance” from the major metropoles, unlike New Hampshire’s

rather solicitous relationship with urban tourists, seems to have added to its appeal

for an increasingly diverse array of “counter-culture” types—artists, professors,

and back-to-the-landers.

Absent New Hampshire’s early advantages—a thriving tourist industry, minor

industrial cities, and convenient transportation to the rest of the East Coast—

Vermont remained in many ways an avatar of an earlier age. As late as the 1950s,

Vermont was a very rural state peopled largely by struggling farmers, logger s, and

craftsmen (Judd 1979). Nonetheless, great effort was spent in highlighting and

broadcasting those qualities that people like the Nearings and Dorothy Canfield were

looking for: pristine farmhouses; small, quaint towns; and, most imp ortantly, a

perceived escape from the bourgeois materialism of twentieth century America.

An interesting example of this is the birth of the skiing industry in Vermont. The