America’s

Trillion-Dollar

Repair Bill:

CAPITAL BUDGETING AND THE DISCLOSURE OF

STATE INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDS

JERRY ZHIRONG ZHAO

CAMILA FONSECA-SARMIENTO

JIE TAN

November 2019

WORKING PAPER

This paper was prepared for the Volcker Alliance for its project on Truth and Integrity in Government Finance.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reect the position of the

Volcker Alliance. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

© 2019 VOLCKER ALLIANCE INC.

Printed November 2019

The Volcker Alliance Inc. hereby grants a worldwide, royalty-free, non-sublicensable, non-exclusive license to download and distribute the

Volcker Alliance paper titled America’s Trillion-Dollar Repair Bill: Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs (the “Pa-

per”) for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the Paper’s copyright notice and this legend are included on all copies.

Don Besom, art director; Michele Arboit, copy editor.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

ii

TRUTH AND INTEGRITY IN GOVERNMENT FINANCE TEAM

W G

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT AND DIRECTOR

STATE AND LOCAL INITIATIVES

M A

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

N A. W-R

PROJECT MANAGER

M C

PROGRAM ASSISTANT

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

iii

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

INTRODUCTION 2

LITERATURE REVIEW 4

FINDINGS 15

CALL TO ACTION: Ten Steps Toward Better Disclosure 33

CONCLUSION: Turning Best Practices into Infrastructure Policy 39

APPENDIX A: States that Post Centralized Capital Improvement Plans 40

APPENDIX B: Agencies Addressing Infrastructure Needs 41

Acknowledgments 42

About the Alliance 43

About the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota 43

About the Authors 44

Board of Directors 45

Staff of the Volcker Alliance 45

Endnotes 46

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS PROVIDE about 80 percent of US public infrastructure

spending. But reported infrastructure spending may not suciently address America’s criti-

cal need to repair public assets, such as roads, highways, waterworks, and buildings, that are

vital to the functioning and growth of the nation’s economy. In its annual Truth and Integrity

in State Budgeting studies, the Volcker Alliance has found that few states have disclosed the

immense cost of these needed repairs in their budget documents. We estimate that the cost

of making deferred repairs at the state level may be as large as $873 billion, equivalent to 4.2

percent of US gross domestic product, or almost three times the value of all investment by

states and localities in nonresidential xed assets. Combined with a reported federal backlog

of $170 billion, the national total deferred maintenance cost may be at least $1 trillion. The

sum may be even larger because while states disclose voluminous information about their

general fund budgets, the same cannot be said for their capital budgeting practices, which

vary widely among states.

In contrast to general fund budgets, which pay for recurring operating expenditures such

as education, public safety, and, sometimes, routine maintenance of infrastructure, capital

budgets typically include costly, long-lived assets involving one-time expenses whose pay-

ment is spread over years to equalize funding needs over time and stabilize taxes. But reporting

standards, such as the type of assets included and the information disclosed, dier from state

to state, and few report infrastructure conditions and needs in their budget documents. To

help states close this critical information gap and improve their decision-making processes,

we oer a ten-point action plan based on best practices relied upon by several states and the

District of Columbia. Implementing the plan will help policymakers set common standards;

improve asset management; make information consistent, updated, and available; and build

a better-informed decision-making process for capital projects.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

2

INTRODUCTION

CAPITAL BUDGETS FINANCE MOST public infrastructure projects, with state and local

governments—through taxes, user fees, bonds, loans, and other nancing mechanisms—

responsible for about 80 percent of public infrastructure investment.

1

According to the US

Bureau of Economic Analysis, state and local investment in government nonresidential xed

assets reached $304.3 billion in 2018.

2

But this sum is likely insucient to address America’s

critical need on deferred maintenance of roads, highways, waterworks, buildings, and other

locally and state-owned assets that are vital to the functioning of the nation’s economy. In

its 2018 study, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preventing the Next Fiscal Crisis,

3

the

Volcker Alliance found that few states reveal the cost of deferred maintenance in their general

fund budget documents. According to the report, “Unfunded infrastructure maintenance is

akin to underfunded pensions. The total liability for each may grow every year that spending

is short of what is required.”

4

States’ lack of disclosure of their deferred maintenance liability has helped reduce most

of their budget transparency grades. Only three states—Alaska, California, and Tennessee,

all of which publish deferred maintenance cost estimates—received a top A in the category

for fiscal 2016 through 2018.

5

The poorer showing by other states show that while most

disclose considerable information about their general fund, or operating, budgets, includ-

ing processes, funding gaps, and program ecacy, the same cannot be said for their capital

budgeting practices.

Although infrastructure is widely regarded as a national concern, capital budgeting prac-

tices dier widely from state to state, reecting America’s composition as a republic of y

individual sovereign entities. State capital budgets typically include costly, long-lived assets

that generally involve one-time expenses whose payment is spread over years to equalize

funding needs and stabilize taxes. But reporting standards, such as the type of assets included

and the information disclosed, vary among states. For instance, transportation assets are

excluded from capital budgets in some states, and information on deferred maintenance is

oen limited. Capital budgets also may not include assets managed by government agencies,

such as state infrastructure authorities.

Few states report on infrastructure conditions and needs in their budget documents.

Most states refer to a document called a capital improvement plan (CIP) as a road map for

future capital infrastructure needs. However, this document depicts more a revenue-oriented

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

3

than a needs-based planning process. The lack of available information about infrastructure

condition forces the public and policymakers to rely on outside analysis of data to inform

decision-making. While such sources are important and largely reliable, states should con-

sider making data collection, distribution, and disclosure more of a priority in their capital

budgeting processes.

This working paper examines the disclosure of infrastructure needs in state budgeting

documents, building on Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preventing the Next Fiscal

Crisis and its 2017 predecessor, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: What Is the Reality?

6

The two reports evaluate the purpose of public spending and the manner in which funds

are spent, and emphasize the importance of comprehensive and accurate accounting and

transparent reporting to inform citizens, encourage responsible policymaking, and improve

scal stability.

In this paper we delve deeper into capital budgeting practices, particularly the disclo-

sure of infrastructure needs in the y states and the District of Columbia. We rst present a

review of literature on the topic and then discuss the methodology used in this paper. Follow-

ing that, we present our ndings in terms of capital budgeting processes, capital budgeting

documentation, and infrastructure needs. We then lay out a ten-point infrastructure disclosure

action plan, featuring examples of best practices from states and the District of Columbia.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

Capital Budgeting Practices

Most literature on capital budgeting has focused on budgeting practices across the states. In

their foundational 1963 work for the Council of State Governments, State Capital Budget-

ing, Albert Miller Hillhouse and S. Kenneth Howard

7

performed some of the most complete

research. The authors used the term “central state capital budgeting” to describe a budgeting

process that considered the submission of agencies’ capital requirements to a central review

agency, the consolidation of these requests for submission to the legislature, and the existence

of administrative arrangements for execution. In a 1988 study that appeared in Public Budgeting

and Finance, researchers Lawrence W. Hush and Kathleen Pero

8

summarized the results of

a survey conducted in all y states that collected information on capital budgets, including

how the capital budget appeared in the governor’s budget, the role of the state legislature,

the elements included in the capital budget, and the way states nanced capital projects. In

a 2013 study published in State and Local Government Review, public nance scholar Natalia

Ermasova

9

examined the eects of economic decline on changes in capital budgeting practices

and evaluated capital budgeting processes in the states aer the Great Recession.

10

Lastly, the

National Association of State Budget Ocers (NASBO) published a series of reports on bud-

geting procedures, including Capital Budgeting Practices in the States, with editions in 1992,

1997, 1999, and 2014. In its 2014 report, NASBO provided a comparative analysis of capital

budgeting practices in the states, highlighting information on each state’s budget documents,

process, and denitions.

11

While existing literature is thorough and reveals nuances in states’

capital budgeting practices, it does not provide a systematic analysis of these practices.

Comparing Capital Budgeting Practices

The literature agrees that the lack of a standardized budget makes it dicult to compare

capital budgeting practices across the states. Capital budgets dier in their contents and the

time span they cover.

12

Each state (we treat the District of Columbia as a state throughout this

paper) has its own denitions, measures, standards, and policies regarding capital expen-

ditures included in the capital budget. Capital expenditures may include land acquisition,

construction, buildings, equipment, renovations, and maintenance.

13

Due to the variety of capital expenditures, states use additional criteria to consider them

in the capital budget. These criteria, such as minimum expenditure thresholds, minimum

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

5

useful life, and nonrecurring nature, vary widely across states. Capital projects in Mary-

land, for instance, are “acquisitions, designs, construction and equipment with a een-year

life, excluding vehicles and supplies and projects under $100,000,” while in Massachusetts

they correspond to “expenditures related to the construction, substantial improvement or

acquisition of capital assets.”

14

Even the denition of capital expenditures—particularly that

of capital maintenance—changes. Ermasova

15

found that a quarter of states included some

maintenance in their operating budgets, while almost a third distinguished between main-

tenance for building renewal, which is included in capital budgets, and routine maintenance,

which is part of operating budgets.

Similarities and Variations in Capital Budgeting Practices

Existing studies reveal some similarities in budgeting practices:

•

States generally rely on long-term capital plans to forecast infrastructure and nancial

needs. Most states report such plans in the CIP, a document that includes capital needs,

the costs of planned projects, and sources of nancing. The life span of these plans

usually ranges between three and ten years, with ve years the most frequent.

16

In its

2014 capital budgeting report, NASBO found that forty-two states and the District of

Columbia have a multiyear CIP.

•

Most states estimate the scal impact of capital projects on future operating budgets.

According to NASBO, capital project requests in forty-three states must include such

information so that ocials can better assess project aordability and facilitate coor-

dination between operating and capital budgets.

17

•

States’ capital budgets may not include all capital expenditures. Hush and Pero

18

found

that the budgets frequently covered less than half of total capital spending. Transpor-

tation was the major exclusion, followed by higher education.

19

NASBO reported that

nineteen states did not include capital expenditures for transportation in their capital

budgets, mainly because transportation revenues came from earmarked resources.

20

•

Current revenues are the primary funding source for most state capital projects, despite

their long life spans. Over the last two decades, current revenues have funded about

70 percent of capital projects, while bond proceeds have nanced the remaining 30

percent.

21

In 1967, twenty states relied primarily on current revenues to fund capital

projects.

22

The number has remained stable, with twenty-two states maintaining a

formal or informal policy of funding capital projects with current revenues.

23

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

6

Although there are some similarities in states’ capital budgeting practices, the literature

illustrates widely dierent procedures—most involving the agencies that prepare budgets.

State agencies submit capital budget proposals to either the governor or the governor’s budget

sta, to the governor and the legislature simultaneously, or to the legislature.

24

The capital

budget formulation usually includes recommendations from state agencies, suggestions from

the capital budget sta, and governor’s preferences. In most cases, the legislature becomes

involved in the process aer the proposed budget is submitted. According to NASBO, twenty-

ve states have a joint legislative and executive review board for capital projects, an approach

that provides another layer of scrutiny before legislative consideration.

25

A number of states,

including Delaware, Indiana, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin, have, in addi-

tion to the governor’s proposal, a state board or advisory committee that submits capital

development recommendations and priorities to the legislature.

26

Classification of States

Of the articles reviewed, Hillhouse and Howard

27

and Ermasova

28

categorized states using dif-

ferent criteria (see table 1). Hillhouse and Howard classied states into three groups according

to the time span covered by the capital budget. The authors determined that the third category

was the “ideal,” and they found just two states in it: Hawaii and Rhode Island. Ermasova

also classied states in three categories, but according to their capital budgeting practices.

She focused on multiyear capital planning, nancial forecasting, nancing sources, formal

systems to present and track capital projects, evaluation of spending, project prioritization,

separation of budget processes, and the CIP.

Single-State Studies

Some authors have focused on single cases. For example, researcher Arwiphawee Srithon-

AUTHORS CATEGORIES

Hillhouse and Howard (1963) 1) States preparing a capital budget that covers the same time period as the operating budget.

2) States with capital budget and operating budget covering the same period and a capital

program covering a longer period.

3) States with a capital budget that covers the operating budget period as well as a longer

period.

Ermasova (2013) 1) Capital budgeting as part of operations.

2) Capital budget as multiyear capital planning.

3) Capital budgeting as strategic capital management.

TABLE 1: Categorization of State Capital Budgeting

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

7

grung

29

and New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli

30

examined capital budgeting

processes in Illinois and New York, respectively, in 2010. Srithongrung found Illinois’s tech-

nical practices for capital budgeting (including cost-benet analyses, quantitative scoring

systems, and statewide inventory accounting) were replaced by nonaccounting approaches,

such as incremental appropriation, interactive discussions in priority ranking, and internal

negotiations among policymakers. Departments usually ranked identied projects based on

each agency’s own criteria and did not use technical practices in prioritization. The author also

found that not all agencies used the CIP, as their projects did not receive funding according to

the CIP schedule; some agencies used the CIP only when obliged to by federal requirements.

Moreover, most of the agencies Srithongrung interviewed stated that the nal appropriations

were not consistent with the original strategic plan because of limited resources, political

inuences, and the legal framework.

DiNapoli noted that agencies lacked a standardized approach to assess the condition of

their capital assets. Without such an approach, agencies provide information with dierent

degrees of specicity, which results in a CIP with inconsistent information. His report also

stated that it was impossible to know how much agencies would spend on maintenance of

capital assets, as that expense was oen included within funds allocated for other capital

purposes. The comptroller also highlighted a lack of integration and coordination in New

York’s capital budgeting and nancing processes, which undermined long-term strategic

planning and made it dicult for the state to assess its risks, needs, and opportunities.

NASBO, GFOA Recommended Practices

While several academic studies and professional association publications help guide ocials

preparing operating budgets, less research has been done on best practices in public capital

budgeting. At the national level, organizations such as NASBO and the Government Finance

Ocers Association (GFOA) have studied some of these practices.

In the 2014 edition of Capital Budgeting in the States, NASBO identied “good practices”

that budget ocers recognize as “eective and ecient tools” to better allocate operating and

capital resources. The organization grouped best practices into ve categories: identication

of capital and maintenance expenditures; capital planning and budgeting; capital nancing

and debt management; capital budget development and execution; and capital asset man-

agement and evaluation (see table 2).

Complementing NASBO’s best practices, GFOA brought attention to the presentation of

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

8

the capital budget as part of the budget document. According to the association, “An excep-

tional capital presentation enhances the transparency and accountability to citizens.” It also

provided guidelines for presentation of the capital budget document:

31

It should include the

denition of capital expenditures it contains, as well as the funding sources and uses for all

projects; it should communicate major steps in the decision-making processes, such as the

schedule, and the evaluation, prioritization, and reporting processes; and it should include

capital project details such as description and costs, time line, and operating impacts.

32

The

association also recommends linking the capital budget to the multiyear CIP, which should

be in a separate section of the budget document.

State Infrastructure Needs

Economic growth and community development depend on high-quality, reliable infrastruc-

ture. Such infrastructure facilitates industrial production and the delivery of goods to con-

sumers. The daily life of communities depends on water and sewer systems, highways and

roads, and schools. Despite its importance, infrastructure in the US is seen as being in poor

TABLE 2: NASBO Recommendations for Good Practices

CATEGORY RECOMMENDATIONS

Identification of capital

and maintenance

expenditures

statute).

Capital planning and

budgeting

Capital financing and debt

management

Capital budget

development and

execution

Capital asset management

and evaluation

SOURCE National Association of State Budget Officers, Capital Budgeting in the States.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

9

condition, signicantly deteriorated, and below standard.

33

This carries serious consequences,

not only for economic growth but for quality of life.

In the literature, we identied three main ways that infrastructure needs are chroni-

cled: the Infrastructure Report Card of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), an

industry organization, as numerous reports and state documents on infrastructure refer to

it or support its ndings;

34

the state management report card,

35

which grades some areas of

government management, including infrastructure; and infrastructure investment trends

in recent decades in the US.

36

The National Council on Public Works Improvement (NCPWI) originated the concept

of a report card to grade US infrastructure. The NCPWI was created by congressional man-

date as an ad hoc council with a two-year life and the mission of reporting to Congress and

the president about the condition of the nation’s infrastructure.

37

The council published a

report in 1988, Fragile Foundations: A Report on America’s Public Works, that assessed the

quality of infrastructure for aviation, drinking water, hazardous waste, inland waterways,

roads, schools, solid waste, transit, and wastewater. The US was given an overall grade of C

because of signs of deterioration and signicant deciencies in conditions and functionality.

ASCE began performing a similar analysis and tracking of the condition of infrastructure

in the US aer the federal government indicated that the NCPWI’s report would not be updated.

ASCE issued its rst Infrastructure Report Card in 1998, adding bridges and dams to NCPWI’s

original categories. Since then, ASCE has added energy, levees, ports, parks and recreation, and rail.

ASCE has updated the report every four years since 2001 and expanded its breadth. The

report now includes a total cost estimate for improving America’s infrastructure—specically,

the cost of upgrading to achieve a B grade in all areas. Since 2009, the report has also included

estimated funding gaps (see table 3). According to the latest report, “Investment needs and

funding are estimated by looking at past trends and future projections when available.”

38

Government agencies, nonprot corporations, and industry consortiums are the ASCE’s main

sources of information.

ASCE grades on a scale of A to F (see table 4). An A indicates that the infrastructure is

in excellent condition, new or recently rehabilitated, and meets future needs. On average,

however, US grades remain poor, exhibiting few signs of improvement over the decades. Ten

years aer the National Council on Public Works Improvement was issued, ASCE reduced

the nation’s overall grade to D. Since then, the grade has risen no higher than D-plus, its

level in 2013 and 2017. The grades indicate that most US infrastructure is in poor condition,

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

10

with many facilities approaching the end of their useful life. Among the sixteen categories,

transit receives the lowest grade (D-minus), while rail receives the best (B). Aviation, dams,

drinking water, inland waterways, levees, and roads all receive Ds.

To assess the condition of infrastructure in categories and ultimately assign a grade,

ASCE formed the twenty-eight-member Committee on America’s Infrastructure. It calcu-

lates grades using eight criteria:

39

CAPACITY Capacity to meet current and future demands.

CONDITION Existing and near-future physical condition of the infrastructure.

FUNDING Current level of funding from all levels of government compared to the esti-

mated funding needed.

YEAR

US

GRADE

TOTAL

INVESTMENT NEEDS

TOTAL

FUNDING GAP

ANNUAL

INVESTMENT NEEDS

ANNUAL

FUNDING GAP

1988 C N/A N/A N/A N/A

1998 D N/A N/A N/A N/A

2001 D+ $1.74 trillion N/A $0.35 trillion N/A

2005 D $1.94 trillion N/A $0.39 trillion N/A

2009 D $2.32 trillion $1.33 trillion $0.46 trillion $0.27 trillion

2013 D+ $3.91 trillion $1.74 trillion $0.49 trillion $0.22 trillion

2017 D+ $4.6 trillion $2.1 trillion $0.46 trillion $0.21 trillion

TABLE 3: The Cost of US Infrastructure Improvement

SOURCE National Council on Public Works Improvement (1998), American Society of Civil Engineers infrastructure report cards (1998–2017).

NOTES N/A: Not available. Values adjusted by authors to constant 2015 dollars.

TABLE 4: ASCE Infrastructure Grading Scale

GRADE DEFINITION

A EXCEPTIONAL, FIT FOR THE FUTURE:

Facilities meet modern standards for functionality and are resilient to withstand most disasters and severe weather events.

B GOOD, ADEQUATE FOR NOW:

capacity issues and minimal risk.

C MEDIOCRE, REQUIRES ATTENTION: The infrastructure is in fair to good condition, it shows general signs of deterioration

vulnerability to risk.

D POOR, AT RISK: The infrastructure is in poor to fair condition and mostly below standard, with many elements approaching

concern with strong risk to failure.

F FAILING/CRITICAL, UNFIT FOR PURPOSE: The infrastructure is in unacceptable condition with widespread advanced

SOURCE American Society of Civil Engineers, 2017 Infrastructure Report Card.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

11

FUTURE NEED Cost to improve the infrastructure and the ability of future funding will

to address the need.

OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE Owners’ ability to operate and maintain the infrastructure

properly, and the infrastructure’s compliance with government regulations.

PUBLIC SAFETY The extent to which the condition of the infrastructure jeopardizes public

safety, and the consequences of failure.

RESILIENCE Infrastructure system’s capability to prevent or protect against signicant

multihazard threats and incidents, and ability to quickly recover and reconstitute critical

services with minimum consequences for public safety and health, the economy, and

national security.

INNOVATION The implementation of new and innovative techniques, materials, technolo-

gies, and delivery methods to improve the infrastructure.

The committee applies the grading criteria and metrics to reports about specic types of

infrastructure—such as aviation, dams, bridges, and railroads. Instead of relying on state data,

which can be scarce, scattered, and inconsistent, ASCE uses for its analysis data from the US

government and professional societies. Reports from the Federal Aviation Administration,

Federal Highway Administration, Association of State Dam Safety Ocials, Environmental

Protection Agency, Federal Emergency Management Agency, and National Parks Service all

appear in ASCE work.

Since its inception, the Infrastructure Report Card has increased in use and popularity.

Several individuals, organizations, and agencies rely on it for insights into the condition of

infrastructure in the nation as well as in individual states. The administrations of Presidents’

Barack Obama and Donald Trump have referenced it, as have international, national, state,

and local news outlets. ASCE’s state-level reports equip national and state legislatures, pro-

fessional associations, and local government associations to make the case for new invest-

ment in infrastructure, in addition to helping them better understand the current condition

of their infrastructure and the costs of delaying investment.

In a study for the Pew Center on the States published in 2008, Katherine Barrett and

Richard Greene (currently special project consultants to the Volcker Alliance) assessed the

quality of management in state government.

40

In particular, states were assigned a grade,

on a scale from A to D, in four fundamental areas of government management, including

infrastructure.

41

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

12

The study graded states less on the physical condition of infrastructure than on the way

it is managed. According to the authors, an A-graded state should “have excellent statewide

and agency planning, be a leader in performance auditing, have outcome data for almost all

government functions, show substantial use of performance information by the executive

branch and some use by the legislature,” and electronically communicate the state’s perfor-

mance to citizens. In assigning grades, the authors used data from several sources, including

an online survey and public documents such as budgets, capital and workforce plans, auditor

reports, and websites. They also conducted interviews with legislators and their stas, scal

analysts, controllers, treasurers, budget ocers and auditors, human resource and transpor-

tation ocials, managers in charge of nontransportation infrastructure, and representatives

of agencies and departments. The authors then considered these criteria:

•

The state regularly conducts a thorough analysis of its infrastructure needs and has a

transparent process for selecting infrastructure projects.

•

The state has an eective process for monitoring infrastructure projects throughout

their design and construction.

•

The state maintains its infrastructure according to generally recognized engineering

practices.

•

The state comprehensively manages its infrastructure.

•

The state creates eective intergovernmental and interstate infrastructure coordina-

tion networks.

Barrett and Greene’s nal report gave the y states an average infrastructure score of

B-minus. Utah (A) and Florida and Michigan (both A-minus) performed best, while Massachu-

setts and New Hampshire (both D-plus) performed the worst. According to the authors, Utah

had a good idea of what its infrastructure required in the way of maintenance and budgeted

1.1 percent of the total replacement value of state-owned buildings every year. Conversely,

New Hampshire’s underfunding and lack of clear priorities for buildings, bridges, and roads

le the state with tough deferred maintenance problems and outdated infrastructure.

US Infrastructure Investment

State and local governments are responsible for most investment in US infrastructure. Over

the years, their responsibility has increased as federal infrastructure investment has decreased;

recently state and local governments accounted for about 80 percent of public infrastructure

investment.

42

Infrastructure spending as a share of GDP has declined in the US over the last

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

13

decades. In a 2014 report for the National Association of Manufacturers, Jerey Werling

and Ronald Horst

43

estimated that total real infrastructure investment, including that in the

public and private sectors, had decreased from nearly 4.5 percent of GDP in the late 1960s to

about 1.5 percent in 2012. Real public infrastructure investment had fallen especially rapidly

since 2003.

44

From 2003 to 2008, such investment fell by 4 percent annually because of high

construction costs; aer that and because of the Great Recession, it continued to fall by an

average of 2 percent a year. Between 2009 and 2010, there was a slight increase due to the

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which provided state and local governments with

funds for infrastructure spending.

These results are similar to those presented by Elizabeth McNichol of the Center for

Budget and Policy Priorities,

45

who showed that, between 2002 and 2016, capital spend-

ing as a share of GDP fell in the vast majority of states. The author also found that in most

states, the portion of total expenditures devoted to capital projects was less than 15 percent

in 2014. Only North Dakota (22.7 percent), South Dakota and the District of Columbia (each

16.7 percent), Wyoming (15.7 percent), and Alaska (17 percent) exceeded that threshold.

Overall, capital spending varied across states based on size, population density, and the

age of infrastructure.

Methodology

We performed a document analysis of governors’ capital budget proposals, capital bills, budget

instructions, budgeting processes and time lines, capital improvement plans, and infrastruc-

ture programs for all states and the District of Columbia. The analysis includes only publicly

available documents and other information. The analysis is divided into three main categories:

capital budgeting processes, capital budgeting documentation, and infrastructure needs.

For the capital budgeting processes analysis, we primarily reviewed the budget pro-

cess document, the budget instructions document, and legislature’s websites. For the capi-

tal budget documentation, we examined the governor’s proposed plan and bills related to

capital projects, the budget instructions document, and the capital improvement plan. We

later analyzed the CIP, as many states noted the importance of this document as a road map

for capital infrastructure needs. Finally, we reviewed infrastructure needs reports and the

disclosure of deferred maintenance in capital budgets and CIPs. Deferred maintenance is

particularly important because of increased costs and risks in an aging infrastructure system.

Because regular maintenance activities are less visible than the construction of new

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

14

facilities, they are oen postponed. The failure to keep up with maintenance has signicant

negative impacts on asset life, leading to higher future maintenance costs and threatening

the safety and health of those using the facility.

46

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

15

FINDINGS

Capital Budgeting Processes

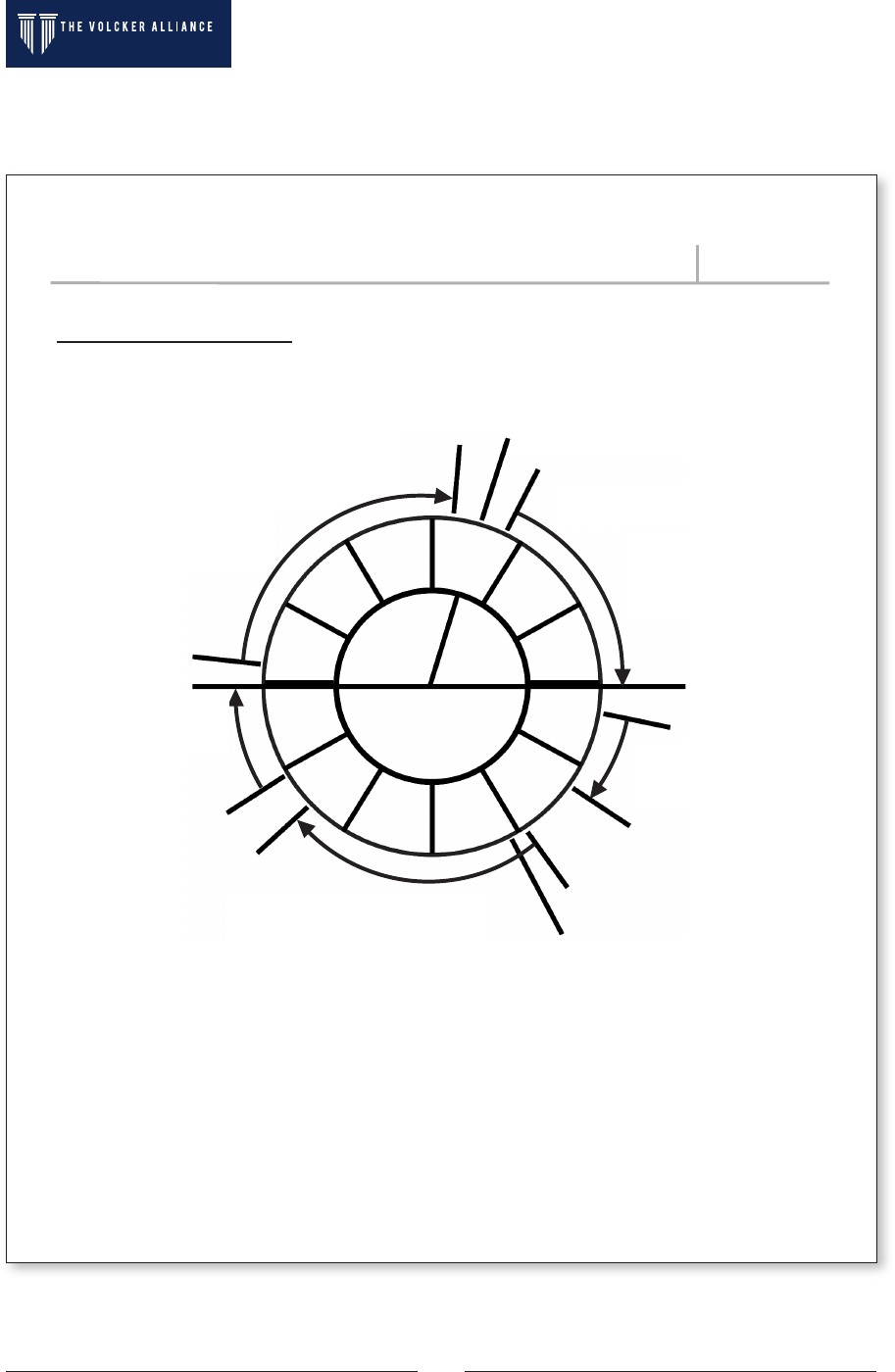

We reviewed budgeting processes with the aim of assessing the level of separation between

the capital and the operating budgeting processes. The budget cycle, which includes all the

events in the budgeting and spending process, consists of four major phases: preparation,

legislative consideration, execution, and audit and evaluation.

47

In this section, we consider

the dierences between capital and operating budgeting processes in terms of when these

processes occur in budget cycles, the parties involved in their preparation, and legislative

consideration (see gure 1).

Most of the literature does not distinguish between the timing for determining the

operating and capital budgets but treats them as being decided simultaneously. We expand

on the current literature by dierentiating between the consideration of these two budget

components. Budget cycles for the capital and operating budgets occur simultaneously in

forty-eight states, with members of the legislature voting for the respective bills in the same

legislative session. In the two exceptions, Minnesota and Ohio, budget cycles for the capital

and the operating budgets are clearly separated. These states use a biennial budget, with the

rst year devoted to the operating budget and the second to the capital budget. Legislators

vote for the operating and the capital bills in sessions held in alternating years.

Hillhouse and Howard

48

listed states according to where capital budget proposals were

submitted: to the governor’s operating budget sta, the governor directly, the legislature

directly, or the governor and the legislature simultaneously. Ermasova,

49

meanwhile, pre-

sented a list of the agencies and committees responsible for preparing a capital budget. We

expand the literature by looking at whether states have a governor’s capital budgeting sta

or a dierent agency that prepares the capital budget. In most states, the governor’s budget

oce prepares the operating budget. Only eleven states clearly identify in their budget docu-

ments either an oce or division dedicated to preparing the capital budget (see table 5). In

Maryland, for instance, the Oce of Capital Budgeting prepares the governor’s annual capital

budget.

50

In New Jersey, all departments requesting capital funding must submit their plan

to the state Commission on Capital Budgeting and Planning, which includes representatives

of the executive branch, the legislature, and the public.

51

Most of the literature on the legislative consideration of the capital budget focuses on

boards or committees that submit recommendations to the legislature that may be made in

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

16

FIGURE 1: Capital Budgeting Processes

Capital Budget Separation Preparation and Consideration Preparation Consideration Neither

WA

MT

ND

SD

NE

KS

OK

MN

WI

MI

OH

ME

NY

PA

WV

KY

AL

FL

SC

NC

VA

IL

MO

AR

LA

WY

NM

HI

MA

RI

CT

NJ

DE

MD

DC

VT

NH

ID

NV

UT

CO

TX

IA

IN

TN

MS

GA

AZ

OR

CA

AK

•

•

•

SOURCE Authors’ research.

TABLE 5: Oce or Division for Capital Budget Preparation

STATE OFFICE OR DIVISION FOR CAPITAL BUDGET PREPARATION

Idaho Permanent Building Fund Advisory Council, Division of Financial Management, and Legislative Services Oce

Louisiana Facility Panning and Control in the Division of Administration

Maryland Oce of Capital Budgeting in the Department of Budget and Management

Massachusetts

Missouri Division of Facilities Management, Design, and Construction in the Oce of Administration

Montana Architecture & Engineering Division of the Department of Administration

Nevada State Public Works Division in the Department of Administration

New Jersey New Jersey Commission on Capital Budgeting and Planning in the Oce of Management and Budget

New Mexico Capital Outlay Bureau in the Department of Finance and Administration

Vermont Department of General Services

Wisconsin Secretary of the State Building Commission

SOURCE Authors’ research.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

17

addition to the governor’s proposal. In this paper, we examine the legislative committees

or subcommittees that consider capital budget appropriations. In een states, the capital

budget is the responsibility of a single committee in each chamber of the legislature, either

an appropriations panel or a subcommittee dedicated to capital projects; that committee or

subcommittee is separate from the one that reviews operating budget appropriations (see

table 6). In Michigan, for instance, the budget appropriation goes to the Appropriations

Committee in each chamber,

52

and each committee has a Capital Outlay Subcommittee

53

to

consider capital projects. In Washington, the House Capital Budget Committee oversees only

the capital budget,

54

while the Senate Ways and Means Committee is responsible for both

operating and capital budgets.

55

Capital Budgeting Documentation

To assess states’ transparency in disclosing infrastructure needs, we examine key elements

of the documentation and the information disclosed in it. We focus on the capital budget

document, the disclosure of transportation expenses in capital budgets, and the use of a

centralized capital improvement plan.

In its 2014 report, NASBO found that in thirty-two states the capital budget is dis-

tinct from the operating budget, while in eighteen states the capital budget is included in

the operating budget.

56

In our study we expand the question by looking at those states that

include the capital budget in the operating budget—particularly on how these states present

the capital budget.

We nd that thirty states and the District of Columbia have an individual document for

the capital budget (see table 7). This document can be a proposal or a bill. All other states

present their capital budget as part of the operating budget: Nine states clearly separate the

capital and the operating budget in two dierent sections in the same document; four fol-

low almost the same pattern but distinguish the capital and operating budgets as dierent

subsections in accordance with the request of each department; and seven blur the boundary

between capital and operating budgets. In these states, the capital budget is presented as a

line item in the operating budget.

Is Transportation Spending Included in the Capital Budget?

According to some studies, transportation expenditures are the major exclusion in the capital

budget.

57

NASBO recently reported that nineteen states do not include capital expenditures

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

18

TABLE 6: Committees for Legislative Consideration of Capital Budget

STATE COMMITTEE FOR LEGISLATIVE CONSIDERATION OF CAPITAL BUDGET

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Iowa Senate Appropriation Committee, Transportation, Infrastructure, and Capital Appropriations Subcommittee

House Appropriation Committee, Transportation, Infrastructure, and Capital Appropriations Subcommittee

Maryland

House Appropriation Committee, Capital Budget Subcommittee

Michigan Senate Appropriation Committee, Capital Outlay Subcommittee

House Appropriation Committee, Capital Outlay Subcommittee

Minnesota Senate Capital Investment Committee

House Capital Investment Committee

Montana Senate Finance and Claims, Long-Range Planning Subcommittee

House Appropriation Committee, Long-Range Planning Subcommittee

New Hampshire Senate Capital Budget Standing Committee

House Public Works and Highways Standing Committee

North Carolina House Appropriation Committee on Capital

2

Oregon Joint Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Capital Construction

Utah Senate Appropriations Committee, Infrastructure and General Appropriations Subcommittee

House Appropriations Committee, Infrastructure and General Appropriations Subcommittee

Vermont Senate Committee on Institutions

House Committee on Corrections and Institutions

Virginia Senate Finance Committee, Capital Outlay and General Government Subcommittee

House Appropriation Committee, General Government and Capital Outlay Subcommittee

Washington House Capital Budget Committee

3

Senate Ways and Means Committee

3

SOURCE Authors’ research.

1) Joint subcommittee. 2) The Senate Appropriations/Base Budget Committee. 3) The Senate Ways and Means Committee consider both

operating and capital budget bills.

TABLE 7: Capital Budget Document

CAPITAL BUDGET DOCUMENT STATES

Individual capital budget Alaska

, Arkansas

, Colorado

, Delaware

, District of Columbia

, Illinois

, Iowa

, Kansas

, Kentucky

,

Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts

, Minnesota

, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New

Hampshire

, New York

, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania

, Rhode Island

,

South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, Wyoming

Capital budget in the operating

budget with some separation

Separate section:

Arizona, Connecticut

, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina,

North Dakota, Virginia

Capital budget as an operating

budget line item

Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, Maine, South Dakota, West Virginia

SOURCE Authors’ research.

1) Discloses transportation expenses in capital budget.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

19

for transportation in their capital budgets, mainly because transportation revenues oen come

from dedicated sources like motor fuel taxes.

58

In this study, we look closely at information

on transportation service expenses, which typically include expenditures on highways, local

roads, and transit.

Almost half of the states with a CIP include in it the cost of transportation services.

Ohio, Vermont, and Washington prepare independent transportation bills. The other states

present transportation expenses in their operating budgets.

The Capital Improvement Plan

While it is not a legally binding document, the CIP assesses capital needs using a multiyear

planning horizon. The document typically comprises two parts: a capital budget and a capital

program.

59

Usually, the rst year or two of the CIP covers the capital budget. The remaining

years are the capital program, which includes projects for which funding may not have been

obtained.

According to NASBO, the CIP serves as a medium- or long-term roadmap for capital

infrastructure requirements. In this document, states identify capital spending needs, the

costs of planned projects, sources of nancing, and the impact that planned projects will

have on current and future operating budgets.

60

NASBO found that forty-two states and the

District of Columbia maintain a multiyear CIP. We expand the literature by focusing on the

disclosure of a centralized capital improvement plan. We dene a centralized, multiyear CIP as

a document that is unique to each state, issued by a central oce, and includes requests from

all state agencies. Such a document reects an enhanced level of analysis and coordination

by the budget oce. It implies that the oce is taking the time to analyze and gather all the

data available to have an informed decision-making process about the state’s capital projects.

We nd that thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia use a CIP (see table 8).

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have a centralized CIP. In eighteen other states,

the central budget oce asks state agencies to submit a CIP through the budget instruction

document, but a centralized document is not available. In most of these cases, the central

budget oce provides a link for each agency’s CIP. The remaining fourteen states do not

provide any information related to long-term capital planning. A few states, such as Mas-

sachusetts, publish a document that is called a multiyear report but that in fact presents

information only for the current budget cycle.

We further concentrate on the states that have a centralized CIP. We focus on the number

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

20

TABLE 8: Where Centralized Capital Improvement Plans Are Used

STATE

CENTRALIZED CAPITAL

IMPROVEMENT PLAN

NO CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT

PLAN CONSOLIDATING

INDIVIDUAL AGENCY PLANS NEITHER

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

District of Columbia

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

SOURCE Authors’ research.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

21

of years covered by the centralized CIP, the connection between CIPs and capital budgets, the

coverage of asset types, the availability of a scheme to prioritize capital projects, information

about nance choices, and the provision of actual infrastructure needs (see table 9). More

than 60 percent of centralized CIPs cover a ve-year period, although the duration of plans

can range from two to ten years. The asset coverage of the centralized CIP is limited in most

states. As table 9 shows, we group states into three categories of asset coverage: buildings

only, limited, and comprehensive. While building only refers to CIPs that include only struc-

tures, comprehensive refers to CIPs that contain all types of assets, including highways and

roads. Limited includes states that exclude transportation assets or that include or exclude

specic capital projects.

TABLE 9: Centralized Capital Improvement Plan Details

STATE PERIOD

CONNECTION

WITH CAPITAL

BUDGET COVERAGE

PRIORITIZATION

SCHEMES

DISPLAYS

FUNDS

DISPLAYS

FINANCING

SOURCES

FUNDING

GAP

Arizona 2 years Buildings only

California

5 years Comprehensive

Connecticut 5 years Buildings only

District of

Columbia

6 years Comprehensive

Iowa 5 years Limited

Kentucky

6 years Limited

Maryland 5 years Comprehensive

Nebraska 6 years Buildings only

New Jersey 7 years Comprehensive

New Mexico 5 years Limited

New York

5 years Comprehensive

Oklahoma 8 years Limited

Rhode Island 5 years Comprehensive

South

Carolina

5 years Limited

South

Dakota

5 years Limited

Texas 5 years Comprehensive

Utah 5 years Buildings only

Vermont 10 years Limited

Virginia 6 years Limited

SOURCE Authors’ research.

1) Financing sources include bond history.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

22

In CIPs with more comprehensive coverage, capital projects in transportation and educa-

tion usually comprise a higher proportion of assets than other sectors. For instance, in Rhode

Island’s 2018–22 CIP, those two categories account for 67.5 percent of total recommended

appropriations for future years.

61

In California, transportation service represents 91 percent

of total proposed funding.

62

In most cases, states oer detailed explanations of their recom-

mended appropriations for future years. South Dakota, Iowa, New Mexico, and Virginia CIPs

contain only limited explanations, however.

Just a handful of states use a standardized method to prioritize capital projects. This typi-

cally includes a single agency or committee taking a lead role in project evaluation. Nebraska,

for example, relies on its Comprehensive Capital Facilities Planning Committee to take charge

of evaluating appropriations. The committee oers suggestions from three dierent perspec-

tives: critical issues related to threat to human life and immediacy of the need; nancial and

economic goals related to operating cost savings and asset preservation; and values related

to project signicance, improved services, and mission relevance.

63

While many CIPs fall short in terms of their scope, 84 percent provide details of revenue

sources, including general funds, federal funds, and other specic funds. The CIPs of eleven

states disclose the availability of nancing sources, such as general obligation bonds, but

only ve of those states include their bond history.

Arizona, New Jersey, Vermont, and Virginia also indicate whether an infrastructure

funding gap may exist. In all four states, the gap reects the dierence between the revenue

available for appropriation and total requests from state departments. The planning of future

capital projects, or at least the preparation of the CIP, is developed primarily by considering

the amount of future revenues. Therefore, the information in CIPs allows us to observe a

pattern of a revenue-oriented planning process in capital budgets. (Further information on

which state agencies issue centralized CIPs can be found in appendix A.)

Disclosure of Infrastructure Needs

Disclosure of infrastructure needs is limited. Several states refer to the capital improvement

plan as the road map for planning, but the CIP usually considers only infrastructure needs

that will be funded in the future. We dene infrastructure needs as the sum of three compo-

nents: deferred maintenance, operation and maintenance, and additional construction (see

gure 2). These elements represent investments that would be needed for current and future

capacity, as well as investments that have been deferred and accumulated over the years and

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

23

that aect present and future investments. We nd that capital budgeting documents con-

sider all the needs in operations and maintenance but only a portion of those in additional

construction and deferred maintenance—usually the portion that will be funded. The portion

that is unfunded constitutes a gap in the data on infrastructure needs.

As many accounts of infrastructure needs refer to ASCE report cards, we looked at

whether states themselves produce reports on their infrastructure needs. We searched docu-

ments providing comprehensive information for various infrastructure assets, along with

their condition and any funding gaps.

We found that Tennessee, New Jersey, Michigan, and the District of Columbia have

released information on infrastructure needs in centralized reports. Although most state

governments do not publicly disclose estimates of their infrastructure needs, some non-

governmental organizations (NGOs) and academic institutions produce reports in this area

(see table 10).

The Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR), for

example, is tasked with compiling and maintaining an inventory of needed infrastructure as

well as with presenting those needs and associated costs to the General Assembly during its

regular legislative session. Created by statute in 1978, TACIR includes representatives from

the executive and legislative branches and counties and municipalities, as well as the state

comptroller. By law, TACIR issues an annual report on infrastructure needs covering a ve-

year period, including projects involving a capital cost of at least $50,000. Information in

the report come from data from the Tennessee Department of Transportation, capital budget

requests submitted by state agencies, and state and local ocials, although localities may

provide only partial information or may decline to participate without penalty.

64

According to TACIR’s January 2018 report, the total estimated cost of needed infra-

structure improvements in the state is about $45 billion, with about two-thirds of this cost

FIGURE 2: Components of Infrastructure Needs

INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDS

DEFERRED MAINTENANCE OPERATION & MAINTENANCE ADDITIONAL CONSTRUCTION

Deferred

Maintenance

Unfunded

Deferred

Maintenance

Appropriation

Operation and Maintenance

Appropriation

Additional

Construction

Appropriation

Additional

Capacity

Unfunded

Gap Capital Appropriation Gap

<

<

<

SOURCE Authors’ research.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

24

unfunded. The total amount includes projects in six categories

65

that will be completed during

the ve-year period of July 2016 to June 2021.

66

In the District of Columbia, the Oce of the Chief Financial Ocer is required to develop

an annual report on a replacement schedule for capital assets. The oce’s Long-Range Capital

Financial Plan Report includes capital asset replacement needs beyond the normal six-year

capital planning period. To determine total capital needs, the district completes a compre-

hensive review of governmental agencies’ capital and asset maintenance requirements, and

scores and ranks each project to ensure that the highest-priority projects were funded.

To analyze needs, the District of Columbia developed the capital asset replacement

scheduling system (CARSS). It involved creating a centralized database of all district-owned

assets and their condition to calculate maintenance and replacement costs.

67

For 2018–23, the

district plans to fund $6.7 billion in capital projects, about $5 billion more than its nancing

capacity (amounting to an average primary capital needs gap of $700 million a year, or 8 per-

cent of the district’s general fund). Of this gap, 52.5 percent corresponds to facilities (mainly

elementary, middle, and high schools) and 36.8 percent to so-called horizontal infrastructure,

principally repairs to streets.

68

In a report last issued in 2000 and not updated since, the New Jersey State Planning

Commission

69

compiled and summarized information provided by state agencies since the

adoption of the rst Infrastructure Needs Assessment in 1992. According to the 2000 report,

the state’s total needs for 2000–20 were $65.5 billion (in constant 1999 dollars), of which

$45.8 billion corresponded to present needs

70

and $19.7 billion to prospective ones.

71

These

amounts included seventeen components of infrastructure in three categories: transporta-

TABLE 10: Reports on Infrastructure Needs

STATE ISSUED BY PERIOD COVERAGE

ANNUAL AVERAGE

TOTAL NEEDS

(BILLIONS)

ANNUAL AVERAGE

TOTAL GAP

(BILLIONS)

Tennessee State 6 sectors $9.0 $6.0

District of Columbia DC government 5 sectors $1.1 $0.8

New Jersey State 3 sectors $4.9 N/A

Michigan State 4 sectors N/A $3.0

Hawaii University 5 sectors $2.9 N/A

Kentucky NGO 12 sectors N/A N/A

Washington NGO 11 sectors $9.5 N/A

SOURCE Authors’ research.

NOTES N/A: Not available. NGO: Nongovernmental organization. Figures in 2018 dollars.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

25

tion and commerce (44 percent), health and environment (33 percent), and public safety and

welfare (23 percent).

In 2016, the governor of Michigan created the 21st Century Infrastructure Commission

to address infrastructure needs. It estimated that the state infrastructure investment gap

over the next 20 years exceeded $60 billion, with an annual investment decit of almost $4

billion. The commission concluded that the state had an annual gap of $1 billion in water,

$2.7 billion in transportation, and almost $70 million in communications infrastructure. The

panel also advanced more than 100 recommendations to improve communications, energy,

transportation, and water infrastructure. The advice revolved around four main subjects:

asset management, coordinated planning, sustainable funding, and emerging technologies.

Some of the recommendations were pilot-testing a regional infrastructure asset manage-

ment process; instituting a database system; implementing a long-term strategy to address

asset condition, needs, and priorities; and creating the Michigan Infrastructure Council to

coordinate infrastructure-related goals.

72

The commission ceased operating in 2017, with its

recommendations unfullled.

73

In some states—including Hawaii, Kentucky, and Washington—NGOs rather than ocial

bodies produce infrastructure needs reports. The Hawaii Institute for Public Aairs

74

con-

solidated in a report the state’s projected infrastructure costs for scal 2010–15. It included

projects in water and environment, transportation, public facilities, energy, and disaster

resiliency, with data coming from an inventory survey of twenty governmental agencies.

The institute found that a total of $14.3 billion of infrastructure was planned for the six-year

period, 53 percent of which was for new projects. Almost 55 percent of the total related to

transportation projects.

The Kentucky Chamber of Commerce released a report in 2017 on the condition of infra-

structure.

75

The report did not provide an exact total to cover needs but listed gaps of about $2

billion in bridges, $6.2 billion in drinking water facilities, and $6.2 billion in wastewater assets.

76

A 2017 report from the Association of Washington Business, the Association of Washing-

ton Cities, the Washington State Association of Counties, and the Washington Public Ports

Association

77

presented the state’s infrastructure needs and benets. Data came from federal

and state departments, cities, and the ASCE. The associations determined total infrastruc-

ture needs of about $190 billion over twenty years, including$134 billion for highways and

roads, about $13 billion for aviation, and $5 billion each for ports, energy, water, wastewater,

and bridges.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

26

Disclosure of Deferred Maintenance in Capital Budget Documents

In the literature, only the Volcker Alliance discusses the disclosure of deferred maintenance

in budget documents. The Alliance

78

in 2017 reported that only two states, Alaska and Cali-

fornia, estimated the costs of deferred infrastructure maintenance in their operating budget

or equivalent documents; in 2018 it updated the total to include Hawaii and Tennessee.

79

We expand the eld by looking at disclosure in capital budgets or supplemental documents

and nd that twenty-three states and the District of Columbia disclose some information

about deferred maintenance (see table 11). We emphasize the denition of deferred mainte-

nance in documents, coverage, estimation methods, and size of the total maintenance gap

or appropriation.

States have similar denitions for deferred maintenance. At the national government

level, the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board denes deferred maintenance as

“maintenance that was not performed when it should have been or was scheduled to be and

which, therefore, is put o or delayed for a future period.”

80

In addition, it recognizes the

use of two measurement methodologies: condition assessment surveys and life-cycle cost

forecasts. Condition assessment surveys are periodic visual inspections of property, plants,

and equipment to determine their condition and the estimated cost to correct deciencies.

Life-cycle costing is an acquisition or procurement technique that considers operating, main-

tenance, and other costs as well as the acquisition cost of assets.

81

State agencies use similar

denitions but oen add that deferred maintenance occurs because of lack of funds, other

pressing expenses, and priority projects. In addition, the denition of deferred maintenance

varies among states. We identify the three main variations as maintenance appropriation,

maintenance gaps, or a combination of both:

MAINTENANCE APPROPRIATION The amount allocated or requested by an agency to fund

maintenance that has been deferred in previous years.

MAINTENANCE GAP The maintenance need that has been deferred. This information is

disclosed as a total (for example, the total deferred maintenance is estimated to be $X

million) or as a portion (this project will reduce deferred maintenance by $X million) in

which the total maintenance gap is unknown.

COMBINATION OF BOTH Deferred maintenance is dened as an appropriation and as a gap

interchangeably throughout the document.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

27

TABLE 11: How Deferred Maintenance Is Reported

STATE

USAGE OF

DEFERRED

MAINTENANCE

DOCUMENT

CONTAINING

DEFERRED

MAINTENANCE

INFORMATION

PLACEMENT

THROUGHOUT

THE

DOCUMENT COVERAGE CALCULATION COORDINATION

Alaska Maintenance

Gap;

Maintenance

Appropriation

with Funding

Final Total SLA

2017

Scattered Limited

Arizona Maintenance

Gap

ADOA Building

System CIP

FY2018

Centralized Limited

Arkansas Maintenance

Appropriation

Biennium

Centralized Limited

California Maintenance

Gap;

Maintenance

Appropriation

2017 California

Five-Year

Infrastructure

Plan

Centralized Comprehensive

Delaware Maintenance

Appropriation

FY2019

Governor's

Recommended

Capital Budget

Scattered Limited

District of

Columbia

Maintenance

Gap

Long-Range

Capital Financial

Plan

Centralized

Hawaii Maintenance

Appropriation

Operating and

Capital Budget,

Centralized Comprehensive

Illinois Maintenance

Gap;

Maintenance

Appropriation

Capital Budget

FY 2019

Centralized Comprehensive

Indiana Maintenance

Appropriation

List of

Appropriations

Biennium

Scattered Limited

Iowa Maintenance

Appropriation

Budget Report

Scattered Limited

Kentucky Maintenance

Appropriation

Statewide

Capital

Improvements

Plan

Scattered Limited

Louisiana Maintenance

Appropriation

2018 House Bill

No. 2

Scattered Limited

2

Maryland Maintenance

Gap

Capital Budget

Volume

Scattered Limited

2

Massachusetts Maintenance

Appropriation

FY2018

22

Five-Year Capital

Investment Plan

Scattered Limited

SOURCE Authors’ research.

1) Excludes transportation assets. 2) Includes only universities and colleges.

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

28

Only twenty-three states and the District of Columbia disclose information about

deferred maintenance. Of these, een states refer to deferred maintenance as “mainte-

nance appropriation,” four refer to it as “maintenance gaps,” and four use the denitions

interchangeably. Most of the information is available in the capital budget (such as a plan or

bill) or CIP and is usually scattered throughout the document. Only six states and the District

of Columbia provide centralized information about deferred maintenance.

The coverage of deferred maintenance is mostly limited. Coverage is related to the state

STATE

USAGE OF

DEFERRED

MAINTENANCE

DOCUMENT

CONTAINING

DEFERRED

MAINTENANCE

INFORMATION

PLACEMENT

THROUGHOUT

THE

DOCUMENT COVERAGE CALCULATION COORDINATION

Minnesota Maintenance

Gap

2018 Governor's

Capital Budget

Recommendations

Scattered Limited

Montana Maintenance

Appropriation

Governor's

2019, Long-

Range Building

Program

Scattered Limited

Nebraska Maintenance

Appropriation

Biennial Budget

information,

biennium

Scattered Limited

Nevada Maintenance

Appropriation

Scattered Limited

New Jersey Maintenance

Gap;

Maintenance

Appropriation

Fiscal

Year Capital

Improvement

Plan

Scattered Limited

2

North Dakota Maintenance

Gap

Legislative

Appropriations

Biennium

Scattered Limited

2

Oregon Maintenance

Appropriation

Enrolled Senate

Scattered Limited

Pennsylvania Maintenance

Appropriation

Senate Bill 651

Scattered Limited

2

South Carolina Maintenance

Appropriation

Budget

Scattered Limited

Texas Maintenance

Appropriation

Sec. 17.14

in General

Appropriations

Biennium

Centralized Limited

SOURCE Authors’ research.

1) Excludes transportation assets.

2) Includes only universities and colleges.

TABLE 11: How Deferred Maintenance Is Reported

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

29

departments or agencies that issue information related to deferred maintenance and the

quality of that information. We classify states to have comprehensive or limited coverage.

Comprehensive coverage means that most state departments or agencies issue deferred

maintenance information and that this information relates not only to state-owned buildings

but to other state assets, including transportation assets. In our analysis, California, Hawaii,

and Illinois provide comprehensive coverage. The other states have limited coverage, as they

disclose deferred maintenance only on state-owned buildings or do not include transportation

assets. Louisiana, Maryland, New Jersey, North Dakota, and Pennsylvania provide informa-

tion on deferred maintenance only for colleges and universities.

There is also a lack of information about how deferred maintenance estimates are arrived

at. Of the twenty-three states that disclose information about deferred maintenance, only

Minnesota and Arizona disclose their calculation methods. In Minnesota, the higher educa-

tion system uses a facilities reinvestment and remodeling forecasting tool to maintain the

system’s projected backlog and renewal needs.

82

This tool is critical for estimating building

needs and projected life expectancy as structures wear out and need replacement. Arizona

uses a building renewal formula (BRF) that was approved by the legislature and follows the

Sherman-Dergis Formula, developed at the University of Michigan in 1981, to model struc-

tures’ upkeep and replacement costs. The BRF is used to determine the annual appropriation

required for renewal for state administrative buildings.

83

It is expressed as

BRF =

2/3 (BV) BA

n

where BV is the building value, BA is the building age, and n the life expectancy of the struc-

ture. According to the Arizona Department of Administration, the BRF reects the current-

year replacement value by updating the original construction cost using the Marshall & Swi

Valuation Service’s building cost index.

84

The state denes the deferred cost in a given year as

Deferred cost = BRF – appropriation

Based on this formula, the department reported $532 million of deferred costs in 2010

dollars accumulated from 1988 to 2017.

85

Only three states (Illinois, Nebraska, and Texas) have a central agency in charge of coor-

dinating deferred maintenance information. In Illinois, the Capital Development Board is

responsible for renovation and rehabilitation projects at more than 8,700 state buildings.

86

The board’s 2019 report shows $7.4 billion in deferred maintenance needs, with the Depart-

ment of Corrections and the Department of Human Services accounting for 53.4 percent of

AMERICA’S TRILLION-DOLLAR REPAIR BILL:

Capital Budgeting and the Disclosure of State Infrastructure Needs

30

that sum. Nebraska’s Task Force for Building Renewal addresses the state’s sizable backlog of

deferred building repairs and improvements. The task force evaluates, prioritizes, and allo-

cates funds for requested deferred building renewal projects.

87

Its process typically includes

a team of architectural, mechanical, and electrical professionals, and requires inspections

of the highest-priority requests of the campus, institution, or agency. Such allocations may

not exactly follow those priorities. In Texas, the Education Code requires the Higher Educa-

tion Coordinating Board to collect information on deferred maintenance needs, including at

public universities, colleges, and health care–related institutions.

88

Many states appropriate less than 1 percent of annual expenditures to address deferred

maintenance (see table 12). Only Illinois and Indiana appropriate more than 2 percent, while

Hawaii, in contrast, appropriates close to 10 percent. But overall, the nation’s total maintenance

gap is unknown. Only California reports complete data on deferred maintenance, providing

comprehensive asset coverage and the total maintenance gap. The governor’s 2017 ve-year

infrastructure plan reports statewide deferred maintenance needs of $78 billion, including

for the Department of Transportation (72.9 percent), Department of Water Resources (16.6

percent), and the University of California (4.0 percent).

89

Considering that the total maintenance gap as a share of California’s expenditures is

about 44 percent and assuming this share is similar across all states, the total state mainte-