G

lobal

S

tudy on

UNITED NATIONS

New York, 2020

Global Study on

Firearms Trafficking

2020

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME

Vienna

DISCLAIMER

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes

without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made.

Suggested citation: UNODC, Global Study on Firearms Trafficking, 2020

(United Nations publication, Sales No. E.20.IV.1).

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC, Member States or

contributory organizations, and nor does it imply any endorsement.

This document has not been formally edited. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this

publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United

Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the

delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

This document was produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein

can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union.

© United Nations, March 2020. All rights reserved, worldwide.

Title: Global Study on Firearms Trafficking

Language: English

Sales no.: E.20.IV.1

ISBN: 978-92-1-130404-6

eISBN: 978-92-1-004969-6

3

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 7

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 15

Seizures data to help understand firearms trafficking? ....................................................................................................... 16

Data sources and limitations

............................................................................................................................................. 17

CHAPTER 1 - THE PRIMARY EVIDENCE BASE: OVERVIEW OF SEIZURES ................................... 19

Chapter overview .............................................................................................................................................................. 19

How much is seized

.......................................................................................................................................................... 20

Types of firearms seized

..................................................................................................................................................... 25

Parts and components and ammunition

............................................................................................................................ 27

CHAPTER 2 - FROM SEIZURES TO TRAFFICKING ......................................................................... 31

Chapter overview .............................................................................................................................................................. 31

Why is it seized: legal justification and criminal context

................................................................................................... 32

Understanding the black market for firearms

.................................................................................................................... 36

SDG indicator 16.4.2 and tracing

..................................................................................................................................... 45

Licit manufacture

.............................................................................................................................................................. 50

CHAPTER 3 - THE NATURE OF FIREARMS TRAFFICKING ............................................................ 57

Chapter overview .............................................................................................................................................................. 57

Prices of firearms in illicit markets

..................................................................................................................................... 58

Modalities of trafficking

.................................................................................................................................................... 60

CHAPTER 4 - LINKS TO ORGANIZED CRIME, TERRORISM AND OTHER FORMS OF CRIME ...... 77

Chapter overview .............................................................................................................................................................. 77

Forms of crime linked to firearms

..................................................................................................................................... 78

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS ............................................................................... 85

ANNEX .......................................................................................................................................... 89

Africa ................................................................................................................................................................................ 89

Americas

........................................................................................................................................................................... 92

Europe

.............................................................................................................................................................................. 96

Asia and Oceania............................................................................................................................................................. 100

ANNEX - TYPES OF FIREARMS ................................................................................................... 102

ANNEX - GLOSSARY

................................................................................................................... 104

ANNEX - STATISTICAL ANNEX

................................................................................................... 107

Acknowledgements

The Global Study on Firearms Trafficking was prepared by the UNODC Crime Research Section, under the

supervision of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of the Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, and Angela Me,

Chief of the Research and Trend Analysis Branch. The UNODC Global Firearms Programme participated by

providing substantive input and advice under the supervision of John Brandolino, Director of the Division for Treaty

Affairs, and Loide Ayree, Chief of the Organized Crime and Illicit Trafficking Branch.

Core team

Analysis, drafting and study preparation

Kristiina Kangaspunta, Antoine Vella, Raggie Johansen, Simonetta Grassi, Leonardo Lara and Mareike Buettner

Database development and data management

Enrico Bisogno, Salomé Flores, Hernan Epstein, Francisco Guerreiro, Trung Anh Dang, Francesca Rosa,

Umidjon Rakhmonberdiev and Stefanie Mavrakou

Graphic design, layout and mapping

Anja Korenblik, Antero Keskinen, Lorenzo Vita, Suzanne Kunnen, Kristina Kuttnig and Federica Martinelli

Editor (Executive Summary)

Joseph Boyle

Technical inputs, review and comments

The Global Study on Firearms Trafficking benefited also from the expertise and invaluable contributions of other

UNODC colleagues in the Global Firearms Programme, namely: Diman Dimov, Paul Ianovici, Lucia Gomez

Consoli, Jacques Seckene Ndour and Silvia De Pedro Sanchez-Romero.

External inputs

This study also benefited greatly from data on customs seizures provided by the World Customs Organization. Data

from the Crime-Terror Collaboration Database (University of Massachusetts Lowell) was made available by Professor

Arie Perliger.

5

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

ABBREVIATIONS

ATF Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms

and Explosives (United States)

ARQ Annual Report Questionnaire

(UN Office on Drugs and Crime)

CTS United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and

Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

(UN Office on Drugs and Crime)

GFP Global Firearms Programme

(UN Office on Drugs and Crime)

IAFQ Illicit Arms Flows Questionnaire

IPFM Intimate partner or family member

MIAFI Monitoring Illicit Arms Flow Initiative

SALWs Small Arms and Light Weapons

Southern Europe

(excl. WB)

Southern Europe

(excluding Western Balkans)

UNODA United Nations Office for

Disarmament Affairs

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs

and Crime

WCO World Customs Organization

7

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

Firearms trafficking is a global

phenomenon with strong variations

between countries

UNODC has carried out its most comprehensive collec-

tion of data on firearms trafficking to date, gathering

details from survey responses and other sources in 81

countries for 2016-17. These data give a unique insight

into the patterns of trafficking globally, regionally and

nationally, providing a vital resource for law enforcement,

policymakers and public bodies seeking to reduce the

damage caused by the illicit circulation of firearms.

Based on these sources, a total of 550,000 firearms were

seized during each of 2016 and 2017. The data showed

wide variations among countries in terms of quantities

seized, which ranged from less than 10 to more than

300,000. The nature of seizures reported also varied

dramatically.

The real global figure for seizures is much higher than

550,000, as some of the countries covered by this study

underreported their seizures for administrative reasons,

and the quality of data varied significantly between coun-

tries. Also, many countries have not provided any infor-

mation, including some of the world’s most populous

nations. Nonetheless, the coverage for this attempt at

global data collection is good and likely to improve in the

coming years, as data collection is streamlined and embed-

ded in national institutions.

Pistols emerge as most seized

firearms globally

Pistols are the world’s most seized type of firearm. How-

ever, this pattern is driven to a large extent by the Ameri-

cas, the region that reported the most seized firearms

overall. Pistols constituted more than 50 per cent of the

total firearms seized in the region during the reporting

period.

In Africa and Asia, shotguns were the most prominent

type. Rifles were the main type of firearm seized in Oce-

ania, and in Europe the distribution was more equal

between pistols, rifles and shotguns.

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY

8

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

FIG. 1

Typical distribution* of reported seized arms, by type, 2016-17

* Simple average based on data for 81 countries.

** Includes weapons reported under “Other” without sufficient information to allow further classification; some of these weapons may be firearms or

small arms and light weapons (SALWs).

*** For some countries, the reported seizure data included weapons other than firearms/SALWs; however data on such weapons were not explicitly

requested by the questionnaire. Hence the share of such weapons is subject to variations in the reporting practice across countries.

Source: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

However, many countries in Africa and Asia appear to

have a lower capacity to intercept and report trafficked

firearms, which may lead to underreporting of some types

of firearms. Moreover, the total figures reported by coun-

tries include seizures which are not directly connected to

trafficking. Based on customs seizures at borders, rifles

emerge at par with pistols. This suggests that firearms such

as rifles may play a bigger role in global trafficking pat-

terns than what is reflected in the currently available data.

Looking more closely, links emerge between trafficking

patterns and broader regional contexts. For example, coun-

tries with higher levels of violent deaths and homicide,

particularly in Africa and Latin America and the Carib-

bean, tend to seize a higher percentage of firearms con-

nected to violent crime. Similarly, in countries with higher

levels of drug trafficking, more arms are seized linked to

that activity.

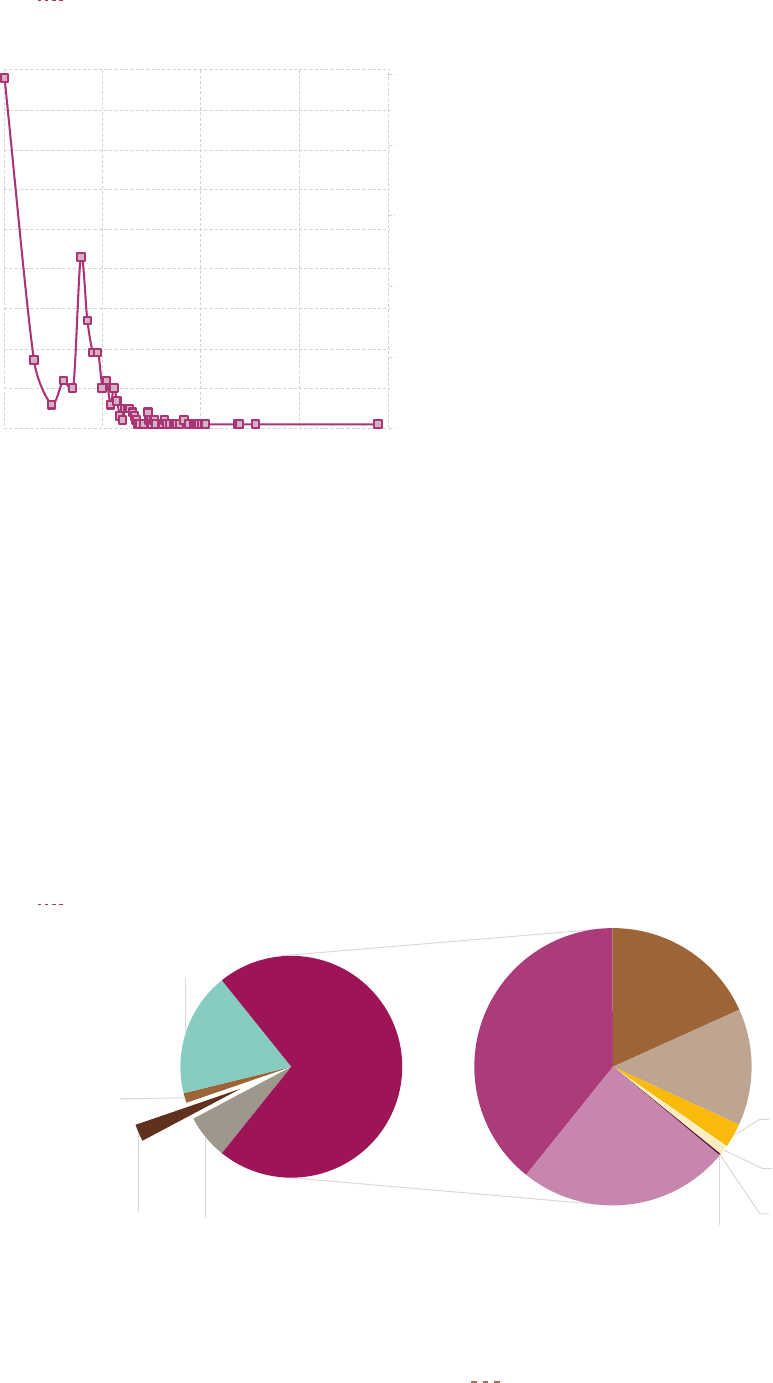

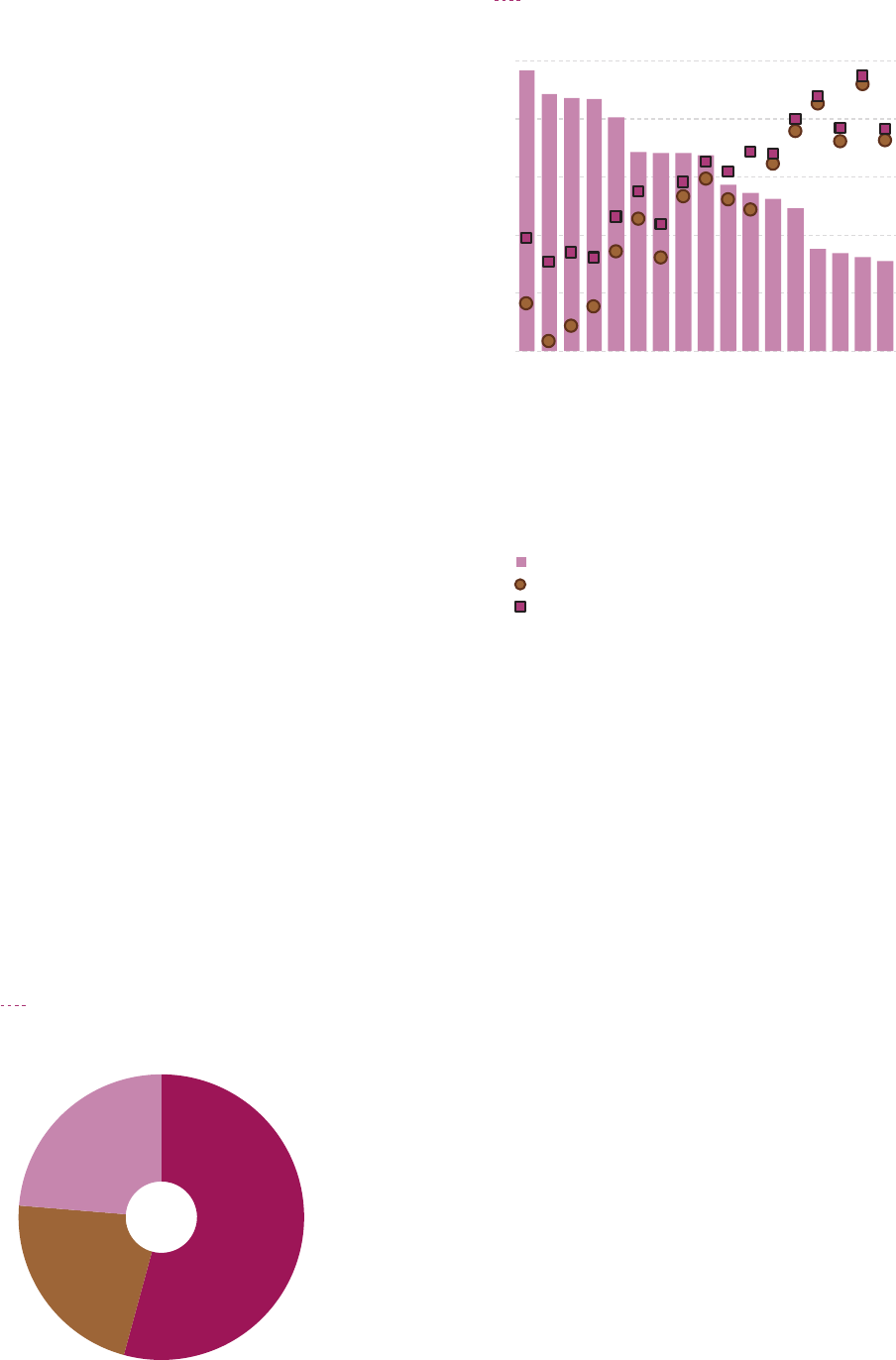

FIG. 2

Total number of arms seized, by country and type of coverage, 2016-17 (average)

¹ For Canada, Ghana and Paraguay data were available for 2016 only.

² For Cameroon, Guinea and Kyrgyzstan data were available for 2017 only.

Sources: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

1

10

100

1,000

10,000

100,000

1,000,000

Australia

Canada¹

ArgenƟna

Russian FederaƟon

Spain

Kenya

Mexico

Greece

Italy

Guatemala

Peru

El Salvador

Ecuador

Sudan

Slovakia

Denmark

Luxembourg

Tunisia

Japan

Jamaica

Albania

Lithuania

Central African Republic

Cote d'Ivoire

Suriname

Morocco

Burundi

Togo

Qatar

Paraguay¹

Saint Lucia

Liechtenstein

AnƟgua and Barbuda

Grenada

United States of America

Costa Rica

Portugal

Honduras

Brazil

Ukraine

CroaƟa

Lebanon

Dominican Republic

United Kingdom

Algeria

Burkina Faso

Hungary

Libya

Azerbaijan

Guyana

Cameroon²

Romania

Republic of Moldova

Nepal

Philippines

Gh ana¹

Colombia

Angola

Belarus

Chile

Kazakhstan

Netherlands

Uruguay

Belgium

Serbia

Panama

Sweden

Norway

Montenegro

Bahamas

Slovenia

Myanmar

Cabo Verde

North Macedonia

Bolivia (PlurinaƟonal State of)

Kyrgyzstan²

Guinea²

Botswana

Tajikistan

MauriƟus

Cuba

FULL COVERAGE INCOMPLETE COVERAGE NO INFORMATION ON COVERAGE/UNCLEAR

Number of arms (logaithmic scale)

Does not include administraƟve seizures

EŽŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶŽŶĂĚŵŝŶŝƐƚƌĂƟǀĞƐĞŝnjƵƌĞƐͬƵŶĐůĞĂƌ

Includes administraƟve seizures

Other undistinguished weapons

(unspecified/aggregate)**

Pneumatic, blank-firing

and gas weapons***

Weapons or related

items other than

firearms/SALWs,

including:***

Unclassified/

unknown

Pistols,

39%

Rifles,

18%

Revolvers,

14%

Submachine

guns, 3%

Machine

guns, 1%

Other firearms

Other SALWs

Shotguns,

25%

Firearms/

SALWs,

72%

9

Introduction

FIG. 3

Typical distributions* of seized fire-

arms/SALWs by type, according to

region, 2016-17

* Simple averages, adjusted for any firearms/SALWs which could not be

classified and quantified into the respective category and weapons other

than firearms/SALWS.

Source: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

MAP 1

Main transnational firearms trafficking flows (as defined by routes of seized firearms),

2016-17

The breakdown into subregional groupings is based on the standard UN classification (M49), adapted to take into account the availability of data and

regions of special interest of the study. Please see Methodological Annex for details.

Arrows represent flows between subregions (not specific countries).

Source: UNODC elaboration of data from Illicit Arms Flows Questionnaire and World Customs Organization.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Transnational trafficking exists

alongside domestic diversion and

illicit manufacture

Most firearms seizures are made within national territories;

seizures at borders on average account for less than 10 per

cent of all interceptions. Seized weapons are overwhelm-

ingly manufactured outside the country of seizure, but it

is likely that the sourcing of firearms found in illicit mar-

kets has an important domestic component, such as fire-

arms diverted from licit channels in the country of

seizure.

There is often little connection to the country of manu-

facture – a significant proportion of arms seized on incom-

ing shipments have not been transported directly from

where they were produced. This suggests that vulnerability

to firearms trafficking is mostly to be found in countries

where firearms are diverted from legal holdings rather than

where they are manufactured.

Northern America is the principal subregion of departure

for seized firearms, according to the available data. On a

smaller scale, Europe and Western Asia are also major

28%

52%

34%

35%

7%

22%

8%

16%

27%

71%

24%

10%

11%

38%

14%

37%

22%

20%

8%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Africa

(18 countries)

Americas

(26 countries)

Asia

(10 countries)

Europe

(26 countries)

Oceania

(1 country)

Pistols Rifles Revolvers

Shotguns Submachine guns Machine guns

Subregions

Eastern Europe

Northern AfricaCentral America

Caribbean

South America

Northern America

Northern and Western Europe Western Balkans

Oceania

Western Asia

Western and Middle Africa

Rest of the World

Eastern and South Eastern Asia

sĞƌLJůĂƌŐĞǀŽůƵŵĞŇŽǁ

sĞƌLJƐŵĂůůǀŽůƵŵĞŇŽǁ

Small

Medium

Large

Southern Europe (excl. WB)

10

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

departure points for illicit flows. However, illicit flows

within subregions often account for significant propor-

tions of firearms entering the market, notably in South

America, Northern and Western Europe and Western Asia.

Transnational trafficking

is concentrated within continents

Based on the routes of seized firearms, transnational traf-

ficking flows seem to be mostly concentrated within con-

tinents. Northern America plays a significant role as

departing subregion for other subregions, particularly

South and Central America, as well as Western Asia.

Northern America, Europe and Western Asia together

accounted for almost all departure points of trafficking in

2016-17. In contrast with other parts of the world, outgo-

ing flows from countries in Europe were predominantly

intended for trafficking across continents.

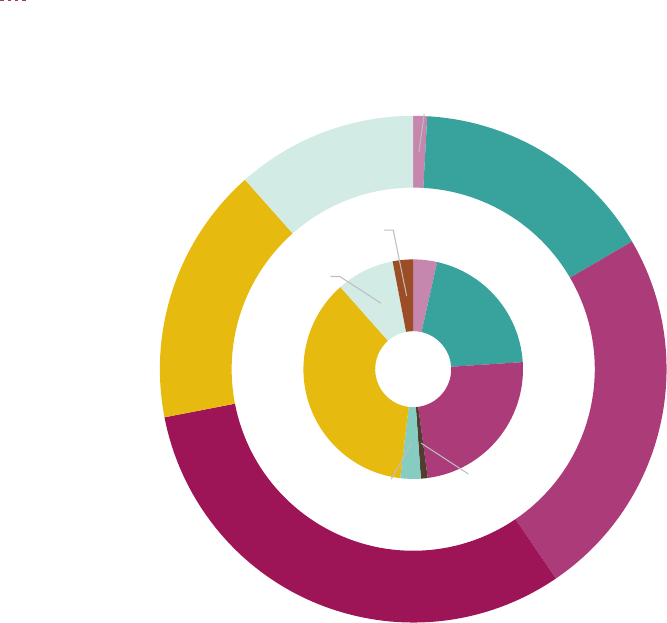

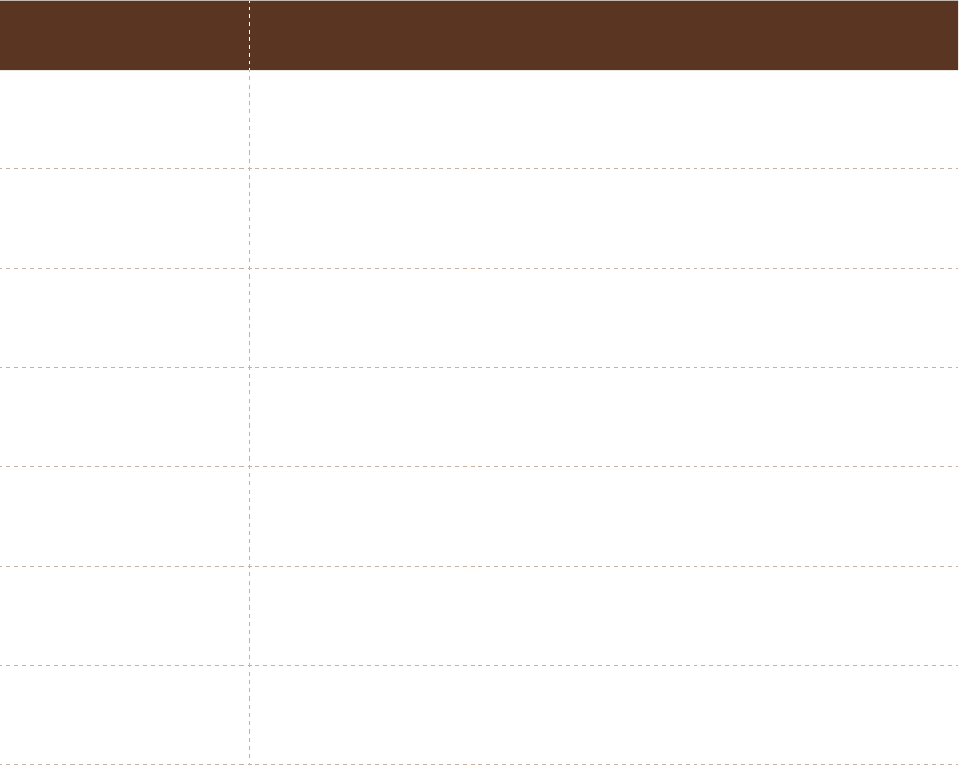

FIG. 4

Distribution of subregions identified as origin of

incoming illicit flowsª (inner circle) and

manufactureª (external circle) for seizures made

in South America, 2016-17

*Excluding Western Balkans.

ªThe largest share of transnational illicit flows affecting countries in South America occurs

between countries within South America. Similarly, countries in South America itself

account for the largest share of manufacture of weapons seized in South America

(including weapons seized in the country of manufacture). These shares are not shown in

the above figure.

Note: The shares of flows and of manufacture are based on different kinds of data which

require different methodologies. Therefore, the comparison should be made with caution.

In both cases, the calculations adjust for the share which is not classified or reported as

unknown.

Source: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

Northern

America

89%

Northern

and

Western

Europe

7%

Southern

Europe*

2%

Western

Asia

2%

Eastern and

South-

Eastern Asia

Eastern

Europe

2%

Northern

America

17%

Northern

and

Western

Europe

10%

Southern

Europe*

66%

Western

Asia

5%

Western

Balkans

Flows

Manufacture

Central and South America together with Western Asia

accounted for more than 80 per cent of trafficking desti-

nations. These main destination areas are known for high

levels of criminal violence or conflict and show the links

between firearms trafficking and violent deaths.

Manufacturing country often

unconnected to illicit flow

Illicit firearms flows are complex and do not necessarily

follow licit flows. The country of manufacture of firearms

and the country where diversions (when firearms leave the

licit circuit and enter the illicit one) and seizures take place

often do not overlap. This is clearly seen in the contrast

between countries that are identified either as manufactur-

ing countries or as the point where the illicit flow starts.

While Europe emerges as the main manufacturing region

in seizures made across the world, the most prominent

subregion of illicit origin is Northern America. Firearms

are durable goods and their circulation before and after

diversion to the black market often involves several

transfers.

Cross-border seizures are most

common at land crossings, but sea

shipments are bigger

Traffickers tend to use sea transport for large shipments.

Cases of seizures from vessels involved more than five times

the number of firearms typically intercepted from other

types of transportation. This suggests that law enforcement

could get a better return on their investment if they

focused on transportation by sea.

However, trafficking by land remains the most common

type of cross-border case, accounting for roughly two-

thirds of the total. Interceptions from vessels accounted

for only around 6 per cent of all customs cases, but 33 per

cent of the total number of firearms seized by customs.

Size of seizure case can reflect the

intended use of the firearm

It appears that the vast majority of seizure cases entail law

enforcement officers intercepting a single firearm or a very

small number, according to available data. However, in

terms of quantities of firearms seized, the big cases may

account for a significant share. For example, among cus-

toms seizures carried out at national borders, roughly three

quarters of cases involved one firearm, but around one half

of firearms were seized in instances that involved 18 or

more firearms.

Seizures of small consignments of one or two firearms may

be linked to individual use, where the firearm is taken

from the end user. These cases most commonly involved

handguns. For example, more than 80 per cent of revolv-

ers were captured in cases involving just a single firearm.

11

Introduction

This type of case often entails a violation of possession

regulations, but can also involve strategic “ant trafficking”,

whereby many people transport weapons in small consign-

ments to meet large-scale demand and reduce the risk of

disruption by law enforcement. This type of trafficking

does not fully explain global arms trafficking, but there is

evidence

1

that it is utilized to transport firearms from the

United States to Mexico.

At the other end of this continuum, countries reported

large seizures that seemed to respond to big instances of

demand, for example conflict. Seizures of rifles, shotguns

and pistols suggest that firearms of these types can be traf-

ficked in consignments of hundreds and thousands. High-

powered firearms such as machine guns and submachine

guns are not often captured, but these rare seizure events

generally involve larger quantities. Around one fifth of all

customs seizure cases that included machine guns and sub-

machine guns involved such firearms in batches of four or

more; on the other hand, such hauls of revolvers, for exam-

ple, were exceptional.

These big seizure cases were far more likely than smaller

consignments to be linked to firearms trafficking offences.

1 See Section on “Ant trafficking” in Chapter 3.

Illicit sellers can compete with licit

markets on price

The cost of buying firearms in the illicit market is usually

significantly higher than in the licit sphere, reflecting the

extra risks and profiteering involved in the black market.

However, there are exceptions. In Latin America and the

Caribbean, for example, illicit prices were lower than the

licit price for handguns. This suggests ample availability

of handguns in the illicit market.

Price data from Europe point to the Western Balkans as a

potential illicit source of firearms, notably assault rifles.

Such weapons were far less expensive in the Western Bal-

kans than in the rest of Europe.

Traffickers supply those seeking to

assemble or convert weapons

Seizures of parts and components are relatively rare com-

pared with seizures of firearms: on average, only 5 per cent

of the number of firearms. However, a different picture

emerges in countries where firearms in non-factory condi-

tion were seized in relatively high numbers (including arti-

sanal or craft production), particularly in Africa and parts

of Asia. Countries in these areas tend to report relatively

high levels of seizures of parts and components.

Illicit manufacturing, conversion, reactivation and assem-

bly of firearms is also present in some European countries,

Border

Border

Border

Border

d

Borde

Border

Border

Border

Border

Border

Border

Land

TRAFFICKING

Small quantities

in many different

vehicles

Ant

TRAFFICKING

Many actors/traffickers

carrying small amounts

Sea

TRAFFICKING

Big quantities are

smuggled by boats

CROSS-BORDER FIREARMS TRAFFICKING METHODS

12

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

possibly reflecting national control mechanisms that make

firearms hard to access legally. Modification of weapons

may also serve the needs of the criminals to use smaller or

more powerful weapons.

Firearms tracing remains insufficient

and countries risk missing SDG target

Countries are committed to “significantly reduce illicit

financial and arms flows” under SDG Target 16.4. One

of the indicators for this target is that the proportion of

firearms traced to their illicit origins must be measured.

Data from 14 countries in 2016-2017 suggest that, on

average, this illicit origin or illicit context was established

for just 28 per cent of the relevant category of firearms.

The countries that registered very high success rates in

tracing firearms reported relatively low seizure levels, per-

haps because tracing requires a lot of resources. On the

other hand, some countries with high levels of seizures

registered a low success rate, which may also be linked to

firearms seized in connection with less serious offences

and perhaps not prioritised in tracing.

Criminal justice responses tend

to underplay the significance of

firearms trafficking

Countries on average seized around two-thirds of firearms

on the grounds of illicit possession, according to the legal

justifications given by national authorities. Trafficking was,

on average, named as the legal justification in only around

9 per cent of cases.

However, it is likely that the offence of illicit possession

provides an easier and quicker way for law enforcement

to justify stopping shipments and seizing firearms, and

trafficking emerges as the actual offence only after further

investigations – this is known as the “criminal context” of

the seizure.

When the criminal context is factored in, the proportion

of seized weapons that could be connected to trafficking

more than doubles to roughly 19 per cent. The real pro-

portion is likely to be even higher, once potential under-

reporting of firearms trafficking is considered.

The evidence suggests that the criminal justice system

focuses on firearms trafficking only in a relatively small

percentage of the cases where it would be warranted –

meaning firearms trafficking is a largely hidden phenom-

enon, only part of which comes to the surface.

Violent crime and drug trafficking

are frequently linked with seizures

Other than arms offences, the criminal conduct most com-

monly linked with firearms seizures was violent crime,

particularly in Latin America and Africa. In Europe, drug

trafficking was the biggest category.

On average, a larger share of firearms is seized in the con-

text of violent crime in countries with high homicide rates.

The same link is shown with drug seizures. In addition,

drugs emerge as the most common commodity intercepted

in the same seizures as firearms, followed by counterfeit

goods, cultural property and natural resources

Unpicking the link between firearms trafficking and the

broader criminal context in which seizures occur is diffi-

cult. Some exceptionally large individual seizure cases

appear to be connected to areas with recent or ongoing

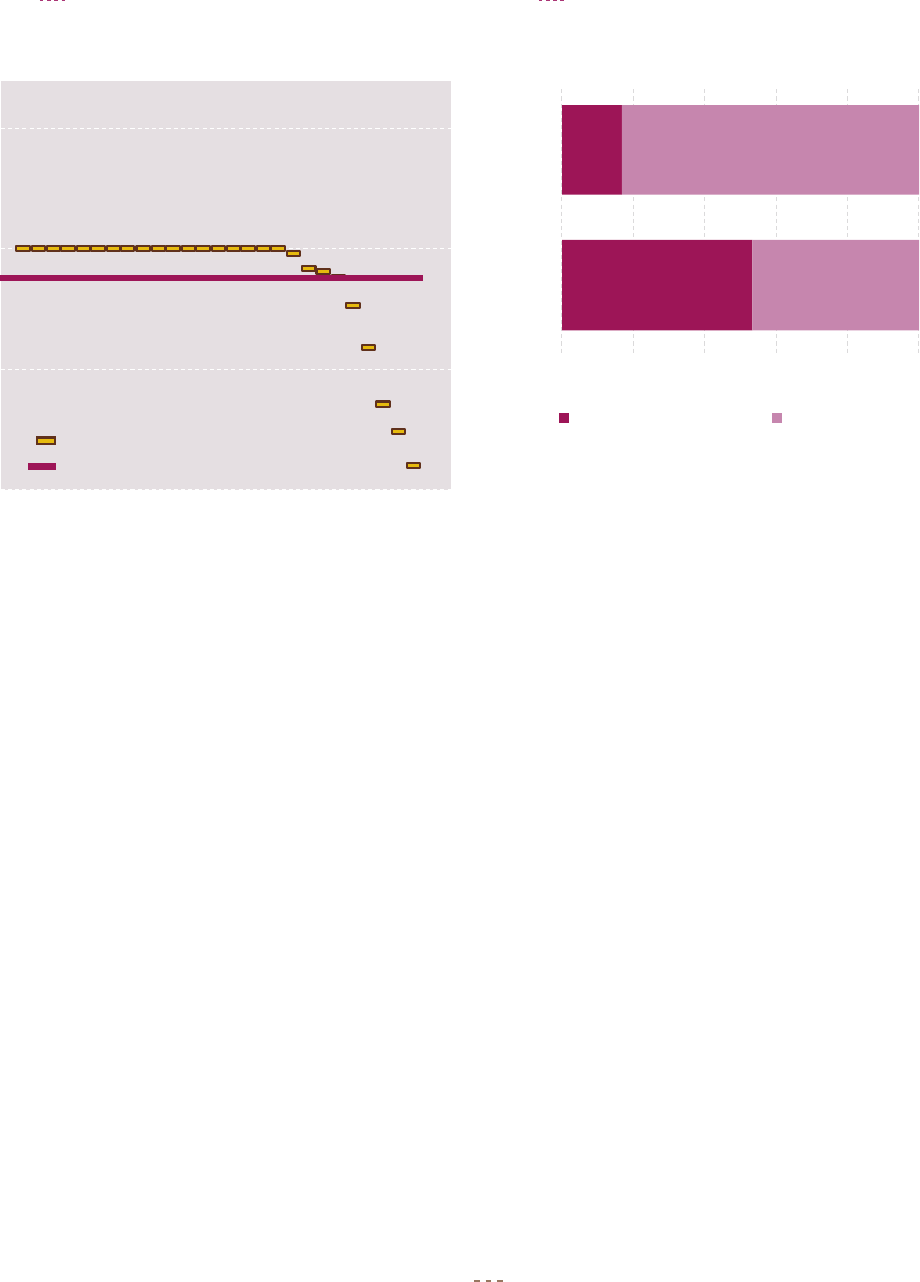

FIG. 5

Breakdowns of customs seizures, by

size* of seizure case, 2016-17

*

The size of a seizure case refers to the number of firearms seized in

that particular instance.

a

A case is considered “small” if between 2 and 5 firearms were seized

in that particular instance.

b

A case is considered “medium” if between 6 and 10 firearms were

seized in that particular instance.

c

A case is considered “large” if between 11 and 17 firearms were

seized in that particular instance.

d

A case is considered “exceptionally large” if at least 18 firearms were

seized in that particular instance.

Source: World Customs Organization.

Single

firearm,

74%

Small

cases

a

,

20%

Medium

cases

b

, 2%

Large

cases

c

, 1%

Exceponally

large cases

d

, 2%

Breakdown of seizure cases, by size*

Single

firearm,

24%

Small

cases

a

,

17%

Medium

cases

b

, 6%

Large cases

c

,

4%

Exceponally

large cases

d

,

49%

Breakdown of firearms seized,

by size* of seizure case

13

Introduction

conflicts, or countries with high levels of violence linked

to organized crime. But several large hauls were reported

that were apparently unconnected to conflict areas or

organized crime.

Some countries may face specific problems related to con-

flict. Weapons feed conflict while it is going on, then

stockpiles can proliferate in the aftermath, causing multi-

ple difficulties for the authorities.

More than 50 per cent of homicides

globally are carried out using

firearms

Overall, more than 50 per cent of homicides globally each

year are carried out with a firearm. The availability of fire-

arms is linked to the homicide rate: a rise in the rate of

firearms possession in a country often goes together with

an increase in the homicide rate.

However, the significance of firearms varies depending on

the context of the homicide. For example, firearms are by

far the most significant method in homicides related to

gangs or organized crime, but far less prominent when the

homicide involves intimate partners and family

members.

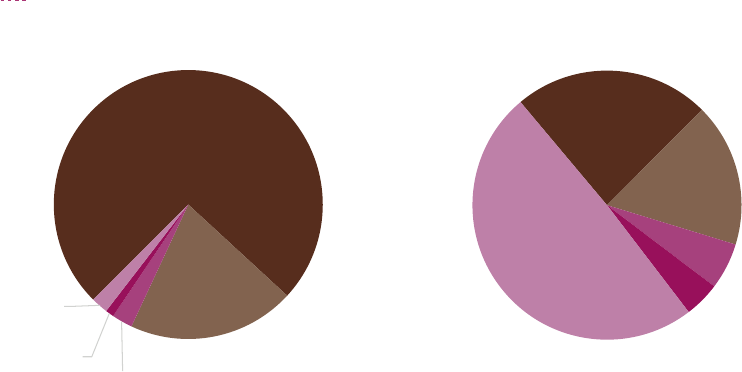

FIG. 6

Firearms seized in typical

a

customs seizure cases, by size

b

of seizure case (excluding cases

with atypical very large number of firearms), 2016-17

a

Isolated cases of a very large size were excluded; these were defined as cases with a size above the 98th percentile for the corresponding specific type

of firearm.

b

Size is measured as the number of firearms of the given specific type seized in the

corresponding case.

Source: World Customs Organization.

There is also a gender factor involved in the use of firearms

in homicide. Most homicide victims and perpetrators

globally are men, and this tends to be even more pro-

nounced among firearms homicides. When considering

homicides of intimate partners and family members, in

which most victims are women, men were more likely than

women to use a firearm when killing their female partners,

while women were more likely than men to resort to a

sharp object.

Overall, seizure data tended to suggest a relationship

between the level of interception and the rate of homicide.

Countries with higher levels of firearms seizures relative

to firearms homicides tend to have lower levels of homi-

cide, which might reflect an established and strong rule of

law situation.

1 revolver

1 pistol

1 shotgun

1 rifle

1 machine gun/

submachine gun

Small batches

Small batches

Small batches

Small batches

Small batches

Medium+

Medium+

Medium+

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Revolvers

Pistols

Shotguns

Rifles

Machine guns and

submachine guns

Seized on its own

Seized in small batches (2-5)

Seized in batches of 6 or more

15

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

INTRODUCTION

Firearms trafficking affects all parts of the world and

impacts on society in multiple ways. It is a major concern

in the context of human security, and it is central in law

enforcement efforts and activities. Firearms are instrumen-

tal in much violence, particularly homicide; they are often

used by organized criminals and they support operations

related to armed conflicts and terrorism. The most

common form of weapons trafficking involves small arms

and light weapons; however, the character of this traffick-

ing can vary significantly in different geographical contexts

and in relation to different weapons.

Firearms are usually manufactured for legal markets by

licenced manufacturers. They can, however, be diverted

into illegal markets at any point in their life cycle. The

action of law enforcement aims at stopping their illegal

movement. In many parts of the world, firearms are easily

available for those who can afford them. Firearms can cir-

culate in legal and illegal markets for a long time and

because they are durable commodities, they can be easily

reused and resold. This durability presents challenges to

prevention and control activities. For this report, data from

firearms seizures are used to have a closer look at firearms

trafficking. Building on the 2015 UNODC Study on Fire-

arms, this report analyses the flows of firearms trafficking,

the types of firearms that are trafficked, how this traffick-

ing is conducted and how it is related to other types of

crime. The report is not aiming at estimating the value of

the illegal market because the available data is too sporadic

to support such an estimation.

The complex nature of firearms concerns is also reflected

in the international legal framework. There is a wide vari-

ety of international and regional instruments addressing

firearms and their trafficking. The overall framework of

this report is based on the Protocol against the Illicit Man-

ufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts and

Components and Ammunition (‘the Firearms Protocol’)

supplementing the United Nations Convention against

Transnational Organized Crime which was adopted by the

General Assembly in 2001

1

. UNODC is the guardian of

the Convention and its Protocols. The Firearms Protocol,

which had 118 Parties as of October 2019, addresses the

illicit manufacturing of and trafficking in firearms from

the criminal justice angle, with a view to provide Member

States with measures to address the transnational nature

of the phenomenon and its links to organized and other

serious crime. Many other instruments introduce a com-

plementary approach to firearms trafficking from disarma-

ment, trade or development perspectives.

2

1 GA resolution 55/255 of 31 May 2001.

2 See a list of relevant instrument and documents in https://www.unodc.

org/unodc/en/firearms-protocol/international-legal-framework.html.

16

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

FIG. 7

Circumstances of firearms seizures

In the context of the Conference of the Parties to the UN

Convention against Transnational Organized Crime,

Member States have requested UNODC to collect and

analyse quantitative and qualitative information and suit-

ably disaggregated data on trafficking in firearms, their

parts and components and ammunition

3

. In addition,

within the framework of the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable

Development, UNODC is monitoring the global devel-

opments related to the indicator 16.4.2 (“Proportion of

seized, found or surrendered arms whose illicit origin or

context has been traced or established by a competent

authority in line with international instruments”).

UNODC also serves as the international agency co-cus-

todian of this indicator together with the Office of Disar-

mament Affairs (ODA).

Seizures data to help understand

firearms trafficking?

In the United Nations Convention against Transnational

Organized Crime, “seizure (or freezing)” is defined as

“temporarily prohibiting the transfer, conversion, disposi-

tion or movement of property or temporarily assuming

custody or control of property on the basis of an order

issued by a court or other competent authority” (article

2f). Seizure can precede final confiscation or forfeiture,

defined as “permanent deprivation of property by order

of a court or other competent authority” (article 2g).

Criteria for seizing firearms can vary considerably among

different countries. The Firearms Protocol requires states

to seize firearms which are illicitly trafficked or manufac-

tured and to criminalize these offences. National legisla-

3 Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention against Transna-

tional Organized Crime, Ninth Session, Resolution 9/2, paragraph 32.

tion and regulations often go beyond the provisions of the

Protocol and firearms can also be seized for other reasons

such as having been used in criminal activities. Seizures

can also be based on administrative violations such as a

lack of a valid licence for possession or failure to comply

with storage conditions.

Seizures are a reflection of a complex reality and of differ-

ent overlapping facets of the phenomenon of illicit traf-

ficking

4

of firearms. Seizures may be related to criminal

activity but some seizures may also arise out of infringe-

ments of an administrative nature. Whether a particular

situation or conduct constitutes an administrative or a

criminal offence will depend on the national legislation,

but administrative offences would typically relate to

expired licences, improper storage, inadequate mainte-

nance, carrying or transporting a firearm in violation of

applicable restrictions, etc. There are also seizures which

happen as a preventive measure, typically in cases of

domestic violence or threats of violence - even if no crime

has been committed with the firearm.

Bearing in mind that firearms are durable goods which

can last for decades, firearms may be detected in criminal

settings long after they entered the black market (through

diversion or illicit manufacture). Moreover, some criminal

links which give rise to the seizure of a firearm may occur

independently of whether the firearm had been previously

trafficked or not. For example, a firearm can be used in

the commission of a crime, and therefore seized, whether

it was legally held or not. Sometimes a firearm is seized in

the context of crimes or investigations which are unrelated

4 The UN Firearms Protocol uses the term “illicit trafficking”. For edi-

torial reasons, this term will be shortened to “trafficking” throughout

this report.

CIRCUMSTANCES OF FIREARMS SEIZURES

CRIMINAL OFFENCES

ADMINISTRATIVE INFRINGEMENTS

PREVENTIVE MEASURES

(e.g. from legŝƟmate owner in context of

domesƟĐ violence)

ILLICIT SUPPLY CHAIN (“TRAFFICKING”)

Firearms exchanging hands, or crossing borders

at moment of deteĐƟŽn

HELD BY “END USER”

(no indicaƟŽn of transfers/cross-border

movement/intenƟon to pass on Įrearm at

moment of deteĐƟŽn)

• ClandesƟne shipments

• False/misleading declaraƟŽns

• Fake/decoy recipients

• Missing authorizaƟon or

licences

FIREARMS ILLICITLY EXCHANGING

HANDS DOMESTICALLY

• Illicit sales/transfers of legally

held Įrearms, including by/from

individuals and licensed dealers

• TheŌof civilian Įrearms

(usually small scale)

• Provision of/distribuƟon of/trade

in Įrearms of illicit origin,

including renƟng and pooling

• Diversion from law

enforcement/military holdings

(potenƟĂůůy large scale)

ILLICITLY MANUFACTURED/

ILLICIT CONDITION

• Rudimentary arms

• ModiĮĐaƟon

• Conversion

• ReaĐƟvaƟon

• Erased/altered markings

• Assembled from parts and

components

• Arms manufactured arƟsanally

without authorizaƟon

ILLICIT USE

• Homicide

• Bodily harm

• Threats and coercion

• Danger to public safety

• Armed robbery

ILLICIT CONTEXT

Independent invesƟgaƟons

into drug traĸĐking, traĸĐking

in persons, smuggling, other

organized crime, terrorism, etc.

“PURE” ILLICIT POSSESSION

Unauthorized possession, no other

apparent criminal links and unclear

origin

TRANSNATIONAL TRAFFICKING

AND DIVERSION

17

Introduction

to arms offences, such as organized crime or drug traffick-

ing; in such cases, trafficking may or may not have hap-

pened prior to the seizure. A firearm can also be seized

because of its condition, such as the case of altered or

deleted markings or illegal modifications, or because it was

illegally manufactured, including conversion from other

weapons, illegal assembly or illicitly manufactured in arti-

sanal settings. Once more, such firearms may or may not

have been trafficked prior to seizure. There may also be

cases of a criminal nature in which a firearm seized from

its holder is of unclear origin but there are no evident

criminal links other than unauthorized possession.

The cases described above typically occur when a firearm

is seized from its “end user”, that is, a person or group of

persons who held the firearm for their own purposes and

use (lawful or not). This leaves the case of firearms which

were detected in circumstances which suggest illegal trans-

fers or movement at the moment of interception. Even

among such firearms, such transfers or physical movement

may be internal to a country, or transnational. Such sei-

zures are those which reflect most directly the nature of

illicit flows of firearms. Seizures from cross-border ship-

ments, such as those made by Customs, are of particular

interest.

Data sources and limitations

The report is based on data collected from Member States

through the Illicit Arms Flow Questionnaire (IAFQ),

5

which was developed in cooperation with national and

international experts, relevant international and regional

organizations, and non-governmental organizations and

research entities, in order to collect seizure data in both

aggregate form and on a case-by-case basis. The question-

naire collected data on several aspects of firearms traffick-

ing, such as trafficking routes, criminal context, tracing

and the criminal justice system response to this crime. A

total of 80 responses to the questionnaire were received.

In addition, complementary sources of data were used,

particularly national reports on the Implementation of the

Programme of Action on Small Arms and Light Weapons

and the International Tracing Instrument (collected and

shared by the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs) and

seizure data from the World Customs Organization

(WCO). Most of the data cover the years 2016-2017.

5 Questionnaire on Illicit Arms Flows. Note by the Secretariat. Sixth

Session of the open-ended intergovernmental working group on

firearms established by the Conference of the Parties to the United

Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, Vienna,

2-3 May 2018. CTOC/COP/WG.6/2018/CRP.2.

MAP 2

Responses to the UN-IAFQ (2018 data collection exercise on firearms) and other countries/

territories with partial or supplementary data from other sources

* Includes responses from 6 countries limited to metadata and qualitative data only.

Source: UNODC elaboration of data from Illicit Arms Flows Questionnaire and World Customs Organization.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India

and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South

Sudan has not yet been determined.A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern

Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Responses to the UN-IAFQ (Illicit Arms Flows Questionnaire)*

Countries or territories with partial data for IAFQ indicators (2016/17) from other sources

18

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

These sources were used in particular to generate quanti-

tative data for some of the indicators covered by the Illicit

Arms Flow Questionnaire, yielding data for a total of 107

countries and territories for at least one of the years 2016

or 2017.

There are some limitations concerning the use of seizure

data in the context of firearms trafficking. Seizures can be

made for reasons other than firearms trafficking per se.

Firearms may be seized because they were used in the con-

text of criminal activities such as drug trafficking or homi-

cide. In addition, as for most such data related to crime,

seizure data reflect both the level of trafficking and the

effort and capacity of law enforcement to implement the

regulatory mechanisms which may vary considerably

between countries. Triangulating seizures data with other

information and analysing them across countries help to

use seizures data to inform patterns and dynamics of traf-

ficking but seizures alone do not describe the level of traf-

ficking. Legal definitions and regulatory frameworks can

differ greatly from one country to the next, making coun-

try-level comparisons difficult and fraught with risks of

comparing different phenomena. In addition to these gen-

eral limitations, some specific limitations concerning the

data collection for this report need to be noted. The data

collection could not cover all countries in the world and

even for those countries that did respond, the richness and

quality of the responses varied. While some parts of the

questionnaire resulted in good quality data, other parts

were left empty or only scarce data were submitted. These

limitations should be kept in mind when reading the

report.

19

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

CHAPTER 1

THE PRIMARY EVIDENCE BASE:

OVERVIEW OF SEIZURES

Chapter overview

This first chapter provides an overview of the available

data on firearms seizures across the world, focusing par-

ticularly on the magnitude and location of seizures, as well

as the types of firearms that are most frequently seized. It

also analyses the typical sizes of seizure events according

to type of firearm.

Data on total arms seized were available for 81 countries

(including IAFQ responses as well as other official sources),

amounting to roughly 550,000 arms in each of 2016 and

2017. This absolute figure is however dominated by the

Americas, due to very large quantities seized by some coun-

tries in this region. This region was also relatively well

represented in terms of the number of countries with avail-

able data. On the other hand, there were significant gaps

in data availability in Africa, Asia and Europe, including

missing data from relatively large countries. Moreover, in

some cases there were clear shortfalls arising from incom-

plete coverage within a single country. For these reasons

the analysis often focuses on averages representative of a

typical country rather than global totals.

Based on the available seizure data, pistols are the most

frequently seized firearm type. This is driven to a large

extent, however, by the pattern in the Americas. The

regional patterns vary considerably. While in the Americas,

the main types of seized firearms are handguns (pistols and

revolvers), in Africa and Asia, shotguns are most frequently

seized. In Europe, seizures are relatively evenly distributed

between pistols, rifles and shotguns, whereas in Oceania,

rifles appear to be the most seized type, although this is

based on data from only one country, Australia.

Considering the regional heterogeneity, the seizures pat

-

terns may also reflect trafficking patterns, with pistols and

revolvers being the most trafficked firearms in the Ameri-

cas and – to a lesser extent - in Europe. It is not clear,

however, how the global pattern of seized firearms reflects

global trafficking as there may be less capacity in countries

in Africa and Asia to intercept and report illicit shipments

of firearms, as indicated by the considerable data gaps in

these regions. It could be that the type of firearm domi-

nating seizures in Africa and Asia – shotguns – is more

significant in global trafficking flows than what can be

gleaned from available seizure data.

Firearms seizure events vary in size, although the vast

majority of seizures involve one or a few firearms. The

average number of firearms seized per case is 1.4 but in

terms of number of seized firearms, about half were seized

in large quantities. Most seizure events were small, but a

few cases with large quantities of firearms – notably rifles,

shotguns or pistols – were seized in a single instance. This

suggests that firearms can also be trafficked in large quan-

tities. While small scale trafficking is possible and present

20

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

in some regions (see section on ant trafficking in Chapter

3), it is likely that very small seizure cases (such as a single

firearm on its own) are frequently connected to other sce-

narios that might give rise to seizures, such as administra-

tive violations, illicit possession, perpetration or threats of

violence, endangering public safety, unauthorized manu-

facture, or firearms held by criminals which come to light

in the context of investigations unrelated to firearms (inde-

pendently of whether they had been trafficked at an earlier

point in time).

Data on seizures reflect both the patterns of the actual

firearms trafficking that is taking place and the efforts of

national law enforcement and other relevant authorities

in tackling it. As such, the data cannot be taken at face

value to accurately depict firearms trafficking flows. More-

over, the data should be interpreted cautiously, particularly

in terms of cross-country comparability. Some countries

have provided partial data that do not include seizures

made in certain geographical parts or by some government

entities. Countries have also made different choices regard-

ing the reporting of administrative and criminal seizures;

some reported separately, some jointly, and some were not

in a position to distinguish. These differences should be

taken into account in comparative analyses.

How much is seized

Seizures of firearms occur when agencies such as police,

customs or other law enforcement entities detect firearms

in circumstances which indicate or suggest a violation of

the law or applicable regulations. Seizures made by such

agencies may occur in the course of, inter alia, routine

inspections (including at border control points), targeted

operations, investigations into crimes and responses to

reported violations.

Thus, seizures reflect the primary point of contact between

the illicit phenomenon and the efforts of the state to coun-

ter it. Seizure data are influenced by, and therefore reflect,

Advantages and disadvantages of other data sources related to seizures

The evidence provided in this study relies on seizures

data together with other information that help to

interpret them in understanding firearms trafficking.

There are other data not considered in the study

linked to Government responses which could poten-

tially be used with or as an alternative to seizures, but

they are either not available systematically across

countries or they carry similar challenges to seizures.

Confiscations. While seizures represent a temporary

measure that can occur on various legal grounds and

usually signify the starting point of an investigation, a

confiscation is a permanent deprivation of property

that occurs at the end of a judicial proceeding when

factual circumstances are established.* While confis-

cated firearms could provide more reliable informa-

tion on trafficking of firearms, there are several

limitations. The representativeness of confiscations

data leans more than seizures towards measuring the

effectiveness of the criminal justice system rather

than illicit flows. Judicial confiscation orders also may

not exclusively relate to illicitly sourced and trafficked

firearms. Furthermore, data on confiscations are not

as readily available as data on seizures, as judicial

proceedings may take a long time and the informa-

tion may remain in individual files with no aggrega-

tion at national or sub-national level.

Circumstances of the seizure. Data on the circum-

stances of a seizure, such as its suspected criminal

context and its geographical occurrence, represent

precious complementary information that help con-

textualize and interpret seizure data for the analysis

of illicit flows, and questions on such aspects have

hence been included in the Illicit Arms Flows Ques-

tionnaire. Unfortunately, in many countries data at

such a level of disaggregation is not collected by

frontline officers. The challenge relates to the differ-

ent sources of information for seizures and their cir-

cumstances. Seizure data are typically compiled by

law enforcement authorities, while circumstances

may be recorded or revised by other criminal justice

institutions (prosecution and conviction institutions

for example). The disaggregation of seizures data is

accurate if they come from the same primary source.

Diverted (stolen or lost) firearms. Data on diverted

(stolen or lost) firearms are directly linked to the illicit

circulation of firearms and are therefore supported by

some scholars** as a possible primary indicator to

understand firearm trafficking. The challenge with

this indicator is that it does not cover all trafficked

firearms and does not measure the share of firearms

illicitly crossing borders. Data on diverted firearms

may also not have the same level of reporting require-

ments as seizures.

* For legal definitions of “seizure” and “confiscation”, see Article 2 of the

United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime.

** Bromley M., Caparini M. and Malaret M., Measuring Illicit Arms and Finan-

cial Flows: Improving the Assessment of Sustainable Development Goal 16.

SIPRI Background Paper, July 2019.

21

The Primary Evidence Base: Overview Of Seizures I

One factor affecting comparability relates to coverage.

Five countries reported that their data set did not cover

the entire national territory (as opposed to 57 countries

which confirmed that the entire geographical territory was

covered), while 17 countries reported that the data did

not cover the operations of all authorities in charge of seiz-

ing firearms (as opposed to 43 countries which confirmed

that all relevant institutions were covered).

1

Incomplete

coverage was also related to the nature of the seizure cases.

Some countries, for example, submitted only the seizures

made by the national authorities in charge of tracing.

Another important element in analysing seizures across

countries is the distinction between administrative and

criminal seizures. While the aim of the UNODC data

collection was to focus primarily on seizures made in a

criminal context, countries could not always make this

distinction or clearly characterize the nature of the seizures

that they reported to UNODC. Sixteen countries clearly

distinguished between criminal and administrative seizures

and provided separate statistics.

2

In some other cases,

countries informed that administrative seizures were not

included, as seizures based on purely administrative

grounds were reportedly not possible in the national con-

text; however, there were also 8 countries for which the

data did include administrative seizures, but they could

not be distinguished from criminal seizures.

Thirdly, some countries reported figures that may have

included firearms which were recovered in ways other than

seizures, for example found and surrendered firearms.

For these reasons, the absolute value of the total number

of seized weapons, and especially comparisons among

countries on this basis, need to be interpreted with

caution.

Figures on national seizure aggregates can be contextual-

ized by taking into account the population of the country.

This approach does not address the comparability issues

1 An additional level of uncertainty was due to the fact that not all

countries which provided the data also provided information on the

extent of geographical or institutional coverage.

2 The requested data on administrative seizures was limited to the total

number of arms seized.

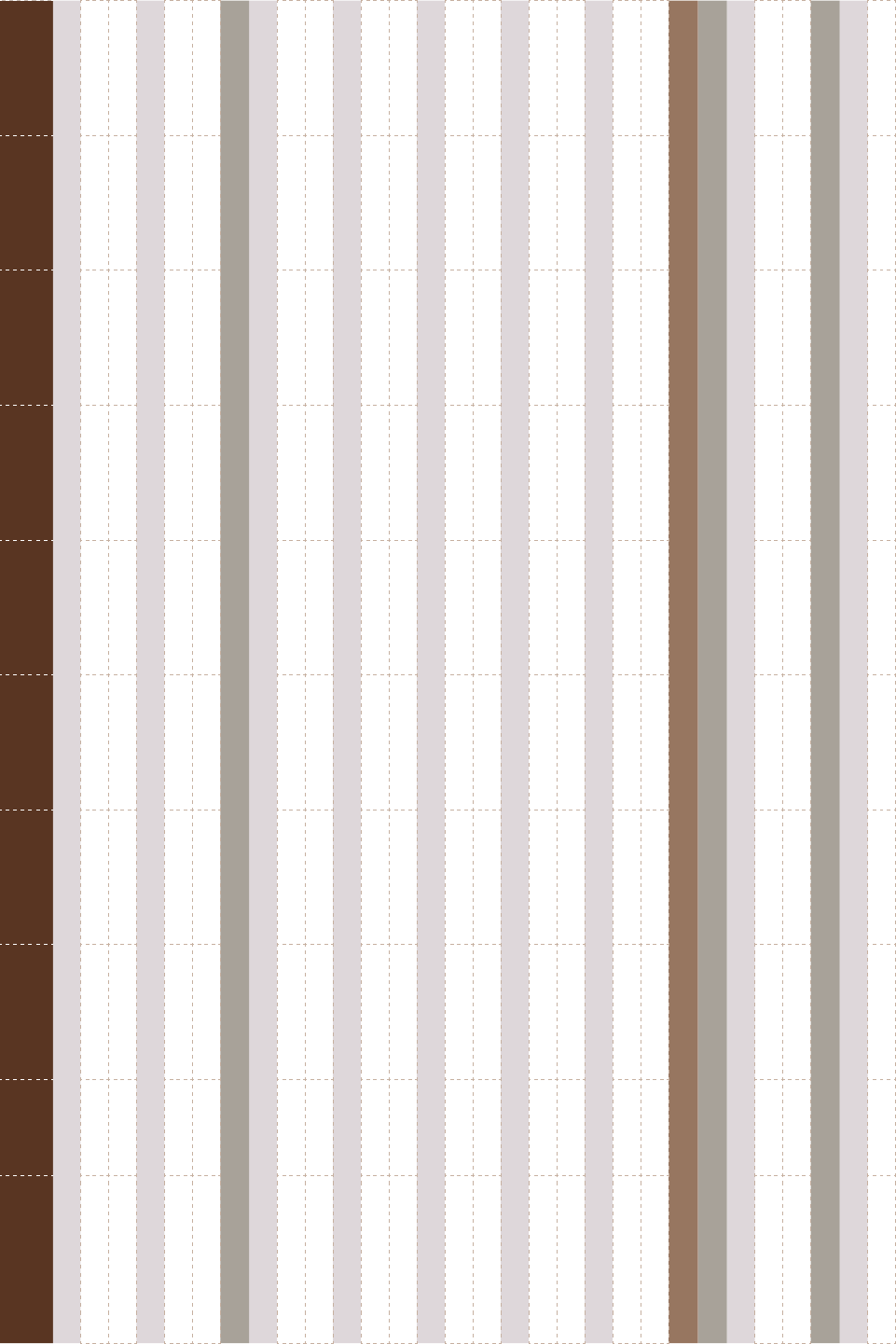

TABLE 1

Availability of seizure data,* by region,

2016-17 (number of countries)

* Total number of arms seized.

two parallel aspects: the extent of the illicit phenomenon

as well as the extent of a certain, targeted form of response

on the part of the authorities.

Moreover, seizures can be made on various grounds, not

all of which are necessarily linked to illicit trafficking. For

example, depending on the national context, firearms may

be seized for minor offences deemed in some countries to

be of an administrative nature - usually violations of regu-

lations pertaining to aspects such as the renewal of licences,

proper storage, restrictions on the carrying of firearms,

etc. Firearms may also be seized in the context of the com-

mission of other crimes such as homicide and robbery,

which, although serious, may not necessarily be commit-

ted with illicitly sourced firearms. Moreover, certain seri-

ous offences may also be related to the illicit nature of

firearms but still not directly to trafficking, such as the

unauthorized manufacture of firearms in a workshop, or

the removal or alteration of markings whose purpose is to

enable identification, accountable weapons management

and tracing.

For these reasons, the use of seizure data to understand

the nature of firearms trafficking needs careful considera-

tion. Seizure data alone can be difficult to interpret and

can potentially lead to misleading conclusions when taken

in isolation, because they reflect priority and capacity of

law enforcement as much as supply. This challenge can be

overcome by taking into account other, independent

sources of information. Another aspect to consider when

analysing seizures is the quality of the data which can

relate, for example, to the extent of coverage of data

reported by a given country. In cases of incomplete cover-

age, the comparability of total aggregates across countries

is limited, but this challenge can be partially overcome by

expressing the corresponding figures in relative terms

(shares of a total). When historical data are available, a

comparison of trends across countries may still be mean-

ingful even if the absolute values present issues of

comparability.

Seizure data, including different disaggregations of seized

items as well as the criminal context of seizures, are the

primary evidence base for this study. This section begins

by giving an overview of the seizure data available to

UNODC.

Through the Illicit Arms Flow Questionnaire, countries

were requested to provide data on the total number of

seized arms, their parts and components, and ammuni-

tion. Overall UNODC was able to compile data on the

number of arms seized in 2016 or 2017 for a total of 81

countries. The total number of such arms amounted to

around 550,000 in each of 2016 and 2017. However, this

figure varied greatly from country to country and the com-

parability across countries is subject to a number of

factors.

2016 2017 2016/2017

Africa 16 17 18

Americas 26 24 26

Asia 9 10 10

Europe 26 26 26

Oceania 1 1 1

Total 78 78 81

22

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

FIG. 1

Total number of arms seized (logarithmic scale), by country and type of overage, 2016-17

(average)

¹ For Canada, Ghana and Paraguay data were available for 2016 only.

² For Cameroon, Guinea and Kyrgyzstan data were available for 2017 only.

Sources: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

FIG. 2

Total number of arms seized per 100,000 population, by country and type of coverage,

2016-17 (average)

¹ For Canada, Ghana and Paraguay data were available for 2016 only.

² For Cameroon, Guinea and Kyrgyzstan data were available for 2017 only.

Sources: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

related to coverage and the inclusion of administrative

seizures, but it provides a better indication of the intensity

of seizures and the possible impact they may have in single

countries. The variability in the resulting prorated figures

is significantly reduced from the variability of simple

totals, but it is still very high, with the values typically

ranging between 0.5 and 69 arms per 100,000 persons.

3

Some small countries emerge among the ones with the

3 10

th

and 90

th

percentiles, respectively.

1

10

100

1,000

10,000

100,000

1,000,000

Australia

Canada¹

ArgenƟna

Russian FederaƟon

Spain

Kenya

Mexico

Greece

Italy

Guatemala

Peru

El Salvador

Ecuador

Sudan

Slovakia

Denmark

Luxembourg

Tunisia

Japan

Jamaica

Albania

Lithuania

Central African Republic

Cote d'Ivoire

Suriname

Morocco

Burundi

Togo

Qatar

Paraguay¹

Saint Lucia

Liechtenstein

AnƟgua and Barbuda

Grenada

United States of America

Costa Rica

Portugal

Honduras

Brazil

Ukraine

CroaƟa

Lebanon

Dominican Republic

United Kingdom

Algeria

Burkina Faso

Hungary

Libya

Azerbaijan

Guyana

Cameroon

²

Romania

Republic of Moldova

Nepal

Philippines

Gh ana¹

Colombia

Angola

Belarus

Chile

Kazakhstan

Netherlands

Uruguay

Belgium

Serbia

Panama

Sweden

Norway

Montenegro

Bahamas

Slovenia

Myanmar

Cabo Verde

North Macedonia

Bolivia (PlurinaƟonal State of)

Kyrgyzstan²

Guinea²

Botswana

Tajikistan

MauriƟus

Cuba

FULL COVERAGE INCOMPLETE COVERAGE NO INFORMATION ON COVERAGE/UNCLEAR

Number of arms (logaithmic scale)

Does not include administraƟve seizures

EŽŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶŽŶĂĚŵŝŶŝƐƚƌĂƟǀĞƐĞŝnjƵƌĞƐͬƵŶĐůĞĂƌ

Includes administraƟve seizures

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Luxembourg

Australia

Qatar

Canada¹

Liechtenstein

Greece

ArgenƟna

El Salvador

Suriname

Guatemala

Jamaica

Spain

Slovakia

Saint Lucia

Albania

Kenya

Denmark

AnƟgua and Barbuda

Ecuador

Russian FederaƟon

Peru

Lithuania

Italy

Grenada

Tunisia

Central African Republic

Mexico

Sudan

Burundi

Togo

Cote d'Ivoire

Japan

Paraguay¹

Morocco

Costa Rica

United States of America

Portugal

Honduras

CroaƟa

Lebanon

Guyana

Dominican Republic

Ukrai

ne

Libya

Hungary

Azerbaijan

Algeria

Brazil

Burkina Faso

United Kingdom

Republic of Moldova

Cameroon²

Romania

Nepal

Ghana¹

Philippines

Uruguay

Bahamas

Belarus

Montenegro

Colombia

Angola

Cabo Verde

Chile

Belgium

Panama

Netherlands

Kazakhstan

Serbia

Slovenia

Sweden

Norway

North Macedonia

Botswana

MauriƟus

Kyrgyzstan²

Bolivia (PlurinaƟonal State of)

Guinea²

Myanmar

Tajikistan

Cuba

FULL COVERAGE INCOMPLETE COVERAGE NO INFORMATION ON COVERAGE/UNCLEAR

Number of arms seized per 100,000 persons,

2016-17 (average)

Does not include administraƟve seizures

EŽŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶŽŶĂĚŵŝŶŝƐƚƌĂƟǀĞƐĞŝnjƵƌĞƐͬƵŶĐůĞĂƌ

Includes administraƟve seizures

23

The Primary Evidence Base: Overview Of Seizures I

MAP 1

Total number of arms seized, by country, 2017

Sources: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries.

The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and

Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet

been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning

sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

highest numbers of arms seized per capita. For some other

countries, the adjusted per capita metric confirms that the

extreme high or low levels are not attributable to their size

only.

In addition to the total number of arms seized, some coun-

tries provided also information on the number of cases

(instances or incidents) in which the arms were seized.

Using this information, it is possible to construct the typi-

cal number of arms seized in a given case providing addi-

tional insight into the nature of the offence. Nineteen

countries provided this kind of information, correspond-

ing to a total of 136,362 arms seized in 97,320 cases, and

overall average of 1.4 arms seized per case. Considering all

of these together, this implies that at least 60 per cent

(probably more) of these cases involved only one arm, and

at most 20 per cent (probably less) involved 3 arms or

more. Only two countries (Paraguay and Hungary) regis-

tered an average of more than 4 arms per case.

Countries were also asked to report information of signifi-

cant seizures on a case-by-case basis. The suggested criteria

for a seizure case to qualify as “significant” were any of the

following: more than 5 arms seized; involvement of organ-

ized crime groups; or the context of transnational traffick-

ing of arms. Independently of the reason for qualifying a

seizure as “significant”, the information collected on a case-

by-case basis included the types and number of arms seized

(along with other specifics such as modus operandi, other

items seized together with the firearms and information

on provenance).

Information of this kind was provided by 32 countries,

which collectively reported 357 cases. Not surprisingly,

significant seizure cases were typically much larger than

the average seizure cases in general. For example, Brazil

reported 10 significant cases averaging 26 arms per case,

compared with an average of 1.3 arms seized per case con-

sidering the total number of seized arms and total number

of cases.

Based on significant cases only, a greater variability (in

comparison with cases overall) across countries could be

observed in the typical number of arms seized per case,

with 7 countries reporting an average of 30 or more arms

seized in a handful of significant cases (3 or fewer), and at

the other extreme, 6 countries reporting less than 5 arms

seized per significant seizure (on average). Once more, this

is not surprising in view of the fact that significant seizures

constitute a small exceptional subset of a bigger

universe.

Overall, among all significant seizure cases, about a third

consisted of seizures of 5 arms or less (in addition to

ammunition and other items) and another third of seizures

of 5-10 arms, with the remaining cases ranging between

11 and more than 6,000 arms. Seizures of a single arm

were the most frequent, accounting for more than a fifth

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Total number of arms seized

100

100 - 00

01 - 000

001 - 10 000

10 000

No data a aila le

24

GLOBAL STUDY ON FIREARMS TRAFFICKING

2020

MAP 2

Total number of arms seized per 100,000 population, by country, 2017

Sources: UNODC IAFQ and other official sources.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries.

The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and

Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet

been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning

sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Ç

Arms seized per 100,000 population

≤ 5.0

5.1 - 25.0

25.1 - 50.0

50.1 - 75.0

> 75.0

No data available

The boundaries and names shown and the designaons used on this map do not imply ocial endorsement or acceptance by the United Naons. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. Doed line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir

agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the pares. The nal boundary betwe

en the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.A dispute exists between the Governments of Argenna and the United

Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

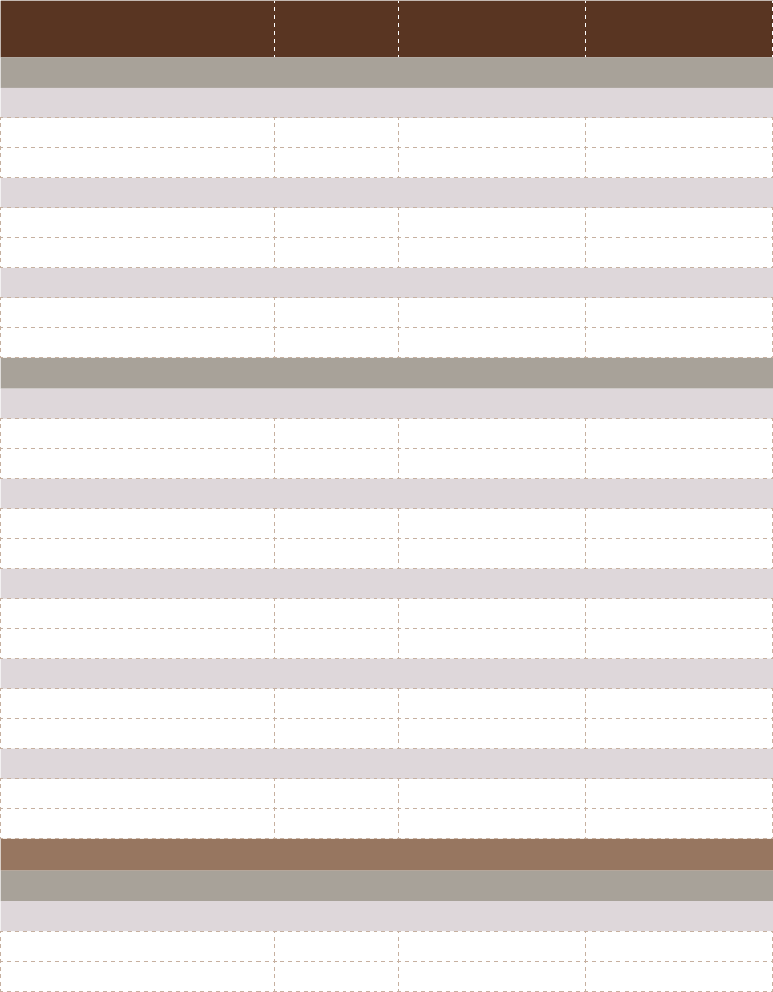

FIG. 3

Average number of arms seized per seizure case, based on total seizures and based on

significant seizures by country, 2016-17

* In addition, Croatia reported a third case involving only explosives.

Note: Number in brackets indicates the number of seizure cases.

Source: UNODC IAFQ.

2.4

2.9

3.4

12.3

26.5

95

110

362

6,435

1

10

100

1,000

10,000

100,000

Honduras (8517)

Republic of Moldova (61)

Mauritius (34)

Australia (44095)

Brazil (5635)

Serbia (2485)

United Kingdom (1417)

Spain (14082)

Netherlands (7775)

Albania (664)

North Macedonia (130)

Philippines (22)

Myanmar (246)

Mexico (7150)

Slovakia (938)

Norway (302)

Portugal (3744)

Paraguay (3)

Hungary (20)

Grenada (16)

Nepal (27)

Cuba (6)

Japan (8)

Philippines (29)

Portugal (3)

Ghana (3)

Albania (8)

Azerbaijan (1)

Panama (3)

Slovakia (2)

Croatia* (2)

Slovenia (3)

Lithuania (2)

Guatemala (8)

Algeria (7)

Costa Rica (1)

Honduras (50)

Paraguay (3)

Australia (71)

Sudan (45)

Denmark (5)

Myanmar (3)

Spain (28)

Brazil (10)

Bolivia (Plurinational State of) (2)

North Macedonia (3)

Mexico (3)

Romania (1)

El Salvador (1)

Tunisia (1)

Greece (1)

AGGREGATE DATA SIGNIFICANT SEIZURES REPORTED ON CASE-BY-CASE BASIS

Arms per case (log scale)

Sum of arms

Arms per case (aggregate data)