A Randomized Controlled Trial of Child-Informed Mediation

Robin H. Ballard, Amy Holtzworth-Munroe, Amy G. Applegate, Brian M. D’Onofrio, and John E. Bates

Indiana University – Bloomington

With over 1 million children in the United States affected by parental divorce or separation each year,

there is interest in interventions to mitigate the potential negative consequences of divorce on children.

Family mediation has been widely heralded as a better solution than litigation; however, mediation does

not work for all families. One proposed improvement involves bringing the child’s perspective to

mediation, to motivate parents to create better agreements. In this randomized controlled trial, we

compared new child-informed forms of mediation against a mediation-as-usual (MAU) control condition.

In child-focused (CF) mediation, parents are presented with general information about children and

divorce; in child-inclusive (CI) mediation, the child(ren) are interviewed and parents are provided with

feedback about their specific case. Given the similar focus and goals of CF and CI, main study analyses

compared a combined CF and CI group (n ⫽ 47) to 22 MAU cases. The CF and CI interventions had

a positive effect on mediation outcomes relative to MAU (e.g., parents were more likely to report learning

something useful, and mediators wanted their cases to be CF and CI). Cases in CF and CI reached

comparable rates of agreement as cases in MAU, but CF and CI agreements included more parenting time

for nonresidential parents, and were more likely to include provisions for coparental communication and

provisions assumed to be better for child outcomes. Study results are encouraging and should provide

support for wider program evaluation efforts to continue refining the CI and CF interventions.

Keywords: divorce, divorce mediation, child-focused mediation, child-inclusive mediation, randomized

controlled trial

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0033274.supp

In the United States, by age 10, nearly 30% of children will

experience the divorce of their married parents, and roughly 65%

of children whose parents are cohabiting will experience the sep-

aration of their parents (Manning, Smock, & Majumdar, 2004).

Divorce and parental separation

1

are risk factors for children

across a wide variety of outcomes. Meta-analyses have shown that

children whose parents have divorced are more likely than children

of continuously married parents to have externalizing problems,

internalizing problems, and academic difficulties (Amato, 2000,

2010). These children also experience greater relationship insta-

bility themselves as adults (Amato, 2000, 2010). Child psycholog-

ical adjustment after divorce is affected by many factors, including

the child’s preexisting vulnerabilities, family structure and transi-

tions, and financial troubles. Parental stress and psychological

difficulties, as well as new family processes (e.g., parental conflict,

changing relationships between parents and children, parents’ re-

marriages and repartnering) also affect child adjustment (Hether-

ington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998). Children adjust better to

divorce when the level of ongoing conflict between parents is kept

low, competent parenting from both parents is maintained, other

important relationships with friends and family continue uninter-

rupted, and the reorganized family is economically viable (Kelly &

Emery, 2003). Interparental conflict, in particular, may be the key

determinant of poor child outcomes after divorce (Lansford, 2009).

Thus, there is interest in interventions that buffer children from the

negative effects of divorce and separation.

For decades, family court professionals have been concerned

that the process of divorce litigation can exacerbate conflict be-

tween parents and spur parents to focus on their rights rather than

their children’s needs (Carbonneau, 1986). Alternative dispute

resolution methods are now often employed instead (Emery, Otto,

& O’Donohue, 2005). A widely used alternative to litigation is

mediation, in which parents work with a neutral, third-party me-

diator to negotiate details of parenting arrangements with each

other (Milne, Folberg, & Salem, 2004).

Unfortunately, little methodologically sound research has been

done on the effectiveness of mediation. Indeed, in a recent “meta-

analysis” of studies comparing mediation to litigation (Shaw,

2010), only five studies were included. Based on this very limited

research, the meta-analysis result was a small-to-medium effect

1

For the sake of brevity, we will use the term divorce to refer to both

divorce and the separation of never married parents.

Robin H. Ballard and Amy Holtzworth-Munroe, Department of Psycho-

logical and Brain Sciences, Indiana University – Bloomington; Amy G.

Applegate, Maurer School of Law, Indiana University – Bloomington; and

Brian M. D’Onofrio and John E. Bates, Department of Psychological and

Brain Sciences, Indiana University – Bloomington.

Supported by a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Grant, Indiana

University. We thank Jennifer McIntosh for consulting on this study;

Brittany Rudd, Fernanda Rossi, and John Putz for their contributions to the

research project; and our research assistants and the student mediators and

child consultants who participated in the project.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Robin

H. Ballard, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana

University – Bloomington, 1101 East 10th Street, Bloomington, IN

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Psychology, Public Policy, and Law © 2013 American Psychological Association

2013, Vol. 19, No. 3, 271–281 1076-8971/13/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0033274

271

size in favor of mediation in the domains of parent satisfaction

with the process and outcome, parental understanding of children’s

needs, and a better coparental relationship. Only a single published

study has involved random assignment to mediation versus litiga-

tion for families in contested custody cases (Emery & Wyer,

1987). In that study of 71 families, fathers who mediated were

more satisfied than fathers who litigated. Mediated cases also

settled more quickly and were more likely to have joint legal

custody arrangements. In a 12-year follow-up (Emery, Laumann-

Billings, Waldron, Sbarra, & Dillon, 2001), relative to litigating

families, the nonresidential parent in mediation families had in-

creased contact with the child and increased involvement in

decision-making. Overall, although the limited data suggest me-

diation may be useful, it is also recognized that improving the

process of mediation may create better outcomes for children

(Emery, Sbarra, & Grover, 2005).

Recently, two related interventions, designed to improve medi-

ation outcomes for children, have been introduced in Australia:

child-focused (CF) mediation and child-inclusive (CI) mediation

(McIntosh, 2000; McIntosh, Wells, Smyth, & Long, 2008). Given

their shared goals and focus, together, we have labeled CI and CF

as child-informed mediation (Holtzworth-Munroe, Applegate,

D’Onofrio, & Bates, 2010). Child-informed mediation approaches

are designed to promote protective factors by motivating parents to

consider the perspective of their children during mediation. This

process ideally leads parents to reduce conflict, make more devel-

opmentally appropriate arrangements for their children, be more

available emotionally, and keep children out of parental disagree-

ments (McIntosh, 2007). As originally designed by McIntosh, CF

was delivered by a trained mediator who gave parents general

information about the effects of divorce and parental conflict on

children, while helping parents to consider how it applied to their

own children. CI was delivered by a mental health professional,

called a child consultant, who directly interviewed the children and

then shared information from that interview with the parents.

2

Child consultants communicated many of the same messages that

were found in parent education programs for divorcing parents

(Fackrell, Hawkins, & Kay, 2011), but did so using a more

customized and interactive presentation.

CI and CF were compared by McIntosh et al. (2008). In a study

of 181 Australian families, for the first six months all families

received CF, and in the next six months all families received CI.

Some families were screened out of the study if a parent did not

possess “adequate ego maturity. . . (demonstrated intent to better

manage the dispute, ability to perceive their children as having

needs of their own, and, with support, willingness to consider

children’s views within the mediation)” (McIntosh et al., 2008,p.

108). One year postintervention, families in both conditions experienced

improvements in family functioning (e.g., lower interparental conflict).

Families receiving CI experienced additional benefits, relative to

families in CF, such as higher levels of child-reported closeness to

father, better mother⫺child relationships, and greater parental

satisfaction with arrangements (McIntosh et al., 2008). A 4-year

follow-up demonstrated continuing benefits (McIntosh, Long, &

Wells, 2009). Only 10% of families in the study reported no

contact between the nonresidential parent and the children, much

lower than Australia’s national average (at 28%). Parents in CF

and CI reported lowered levels of acrimony and conflict, as well as

higher levels of satisfaction with parenting arrangements. The CI

cases were also less likely to have had any legal actions regarding

parenting and custody since mediation, and children in the CI

group reported perceiving less interparental conflict and feeling

less “caught in the middle” of their parents’ disagreements.

These findings are very promising, but the McIntosh study had

important methodological limitations (Holtzworth-Munroe et al.,

2010). One is the lack of a mediation-as-usual (MAU) control

group. If CF and CI do not show benefits relative to MAU, it is not

cost-justified to put families through the extra time and expense or

the involvement of an additional professional required in CF and

CI. Also, it is not clear that CF or CI interventions will generalize

to the United States from Australia, given differences in the

cultures and the legal systems. Another important methodological

limitation of the McIntosh study was the fact that participants who

agreed to be in the study were not randomly assigned to condition.

Also, the CF intervention was delivered by the mediators while the

CI intervention was delivered by a specialized child consultant.

Thus, differences between the conditions might be attributable to

the addition of a child consultant rather than the intervention

content per se.

Current Study

In the present study, our major interest was comparing child-

informed mediation approaches (CI and CF) to MAU in the United

States to examine the impact of adding an explicit focus on the

child to the mediation process. In doing so, we also explored

possible differences between CI and CF. Thus, the current study

was a randomized controlled trial of child-informed mediation

approaches relative to MAU. Of critical importance, families were

randomly assigned to a mediation condition.

The methodology of the current study also deviated from that of

McIntosh et al. (2008) by having child consultants (not mediators)

present parent feedback in both the CF and the CI conditions, for

several reasons. First, by having child consultants deliver infor-

mation to parents in both CF and CI, the interventions were similar

in terms of the amount of professional attention parents received.

Also, having child consultants give parents feedback drew a

clearer role distinction between mediators and child consultants.

Mediator neutrality has been widely seen as an indispensable

component of mediation (Taylor, 1997), and some have raised

concerns about possible conflicts of interests if mediators step

outside of a neutral role to take the position of the child during the

mediation (Simpson, 1989). Unlike McIntosh et al. (2008),wedid

not screen out cases of the study based on the parents’ level of

reflective capacity, because we were interested in testing the

effectiveness of differing forms of mediation among all parties

seeking mediation. Also, most of the interventions were provided

by students in the context of university training clinics.

The current study focused on the immediate outcomes of the

differing mediation interventions: parent perceptions, mediator

perceptions, and the content of agreements reached in mediation.

We hypothesized that, relative to parents in the MAU condition,

parents in the child-informed (CI and CF) interventions would be

more satisfied with their mediation process and agreements; they

2

The child consultant role in child-informed mediation may be viewed

as being similar to the child specialist role in collaborative family law

(Webb, 2008).

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

272

BALLARD ET AL.

would also be more likely to report that they learned something

from mediation and that focusing on their children was helpful. We

hypothesized that mediators in child-informed mediation (CF and

CI) would be satisfied with the parent feedback and mediation,

continue to use any information raised in the parent feedback

during the mediation, and prefer CF and CI to MAU. We hypoth-

esized that child-informed mediation (CF and CI) cases would be

more likely to reach agreements than MAU cases. For families

reaching agreement, we hypothesized that, relative to MAU cases,

agreements reached after CF and CI feedback would be more

likely to specify joint legal or physical custody and to schedule

more parenting time with the nonresidential parent. Additionally,

we hypothesized that CF and CI agreements would be more likely

to address coparental communication and conflict, include refer-

rals to counseling and provisions for safety, and be rated as better

serving the needs of the children.

Method

Participants

Families in mediation. Participants were parents who were

mediating initial divorces (if married) or separations (if unmarried)

or modifications of previous agreements through the Indiana Uni-

versity Maurer School of Law Viola J. Taliaferro Family and

Children Mediation Clinic (hereinafter the Clinic). Parents were

referred to the Clinic by judges from two south-central Indiana

counties. The Clinic generally serves low-income families in need

of pro bono legal services. If parents had children ages 5–17 years,

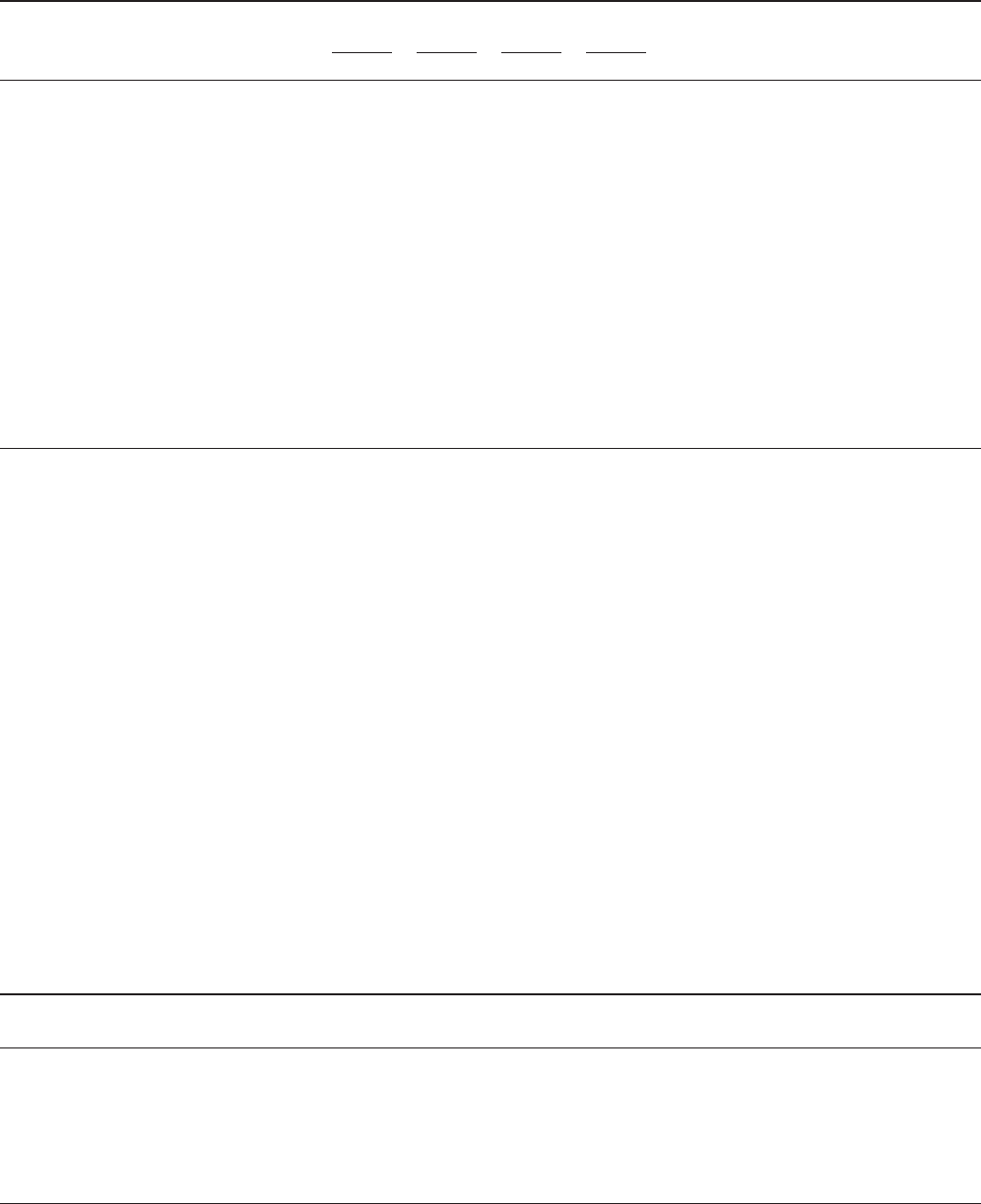

those children also participated in the study. See Figure 1 for an

enrollment flow diagram in accordance with the CONSORT 2010

Statement (Schulz, Altman, & Moher, 2010). Sixty-nine cases

were included in the study analyses.

Mediators and child consultants. Over the course of the

study, 43 mediators (42 law students and one faculty, the Clinic

director) provided mediation services. Each mediator mediated an

average of 2.88 study cases (SD ⫽ 2.08). Also, 14 child consul-

tants (12 graduate students and two faculty members from the

Indiana University Department of Psychological and Brain Sci-

ences) were involved in the study. Each child consultant provided

CI or CF parent feedback to an average of 6.29 cases (SD ⫽ 4.36).

All mediators completed a 40-hr mediator training course and

were registered as domestic relations mediators in the State of

Indiana. They then continued in a clinical law course, under the

supervision of the Clinic director. Cases were generally mediated

by two law student mediators, one who had been practicing as a

mediator for at least one semester and one who was in his or her

first semester of mediating. In CF and CI cases, one or two child

consultants joined the mediators for approximately the first hour to

talk with the parents. Graduate student child consultants were

initially trained through workshops and were then enrolled in an

ongoing clinical practicum course to obtain further training and

supervision.

Measures

Parent outcomes form. At the conclusion of mediation, each

parent reported on his or her experience in mediation. Five satis-

faction items (i.e., satisfaction with the process, the mediators, the

child consultants, and with the agreement reached or with reaching

no agreement) were assessed on 7-point Likert scales, ranging

from 1 (not at all satisfied)to7(very satisfied). Parents also

reported whether they learned anything in mediation and whether

the other parent learned anything in mediation. Finally, parents

were presented with a list of possible benefits of mediation, and

were asked to check all of the aspects of mediation that had been

helpful. This list of possible benefits is given in the Results

section.

Mediator outcomes form. At the conclusion of mediation,

mediators completed postmediation reports that were deidentified

and used for research purposes only (i.e., they did not affect

grading for any students). These items were answered on a 1–5

Likert scale, ranging from very unsatisfied to very satisfied. Me-

diators also reported on whether the child consultants’ information

about the children continued to be discussed during the mediation,

with ratings from 1 (not at all)to5(very often). Mediators also

answered the question “How well did you think the assigned

condition (CI, CF, or MAU) worked for this case?” on a 3-point

scale of very well, neutral,ornot well. Finally, mediators reported

whether the parents expressed concerns about mediator impartial-

ity, answered as a yes or no question.

Mediation results (Was an agreement reached?). The re-

sults of the mediation were coded from a document in the medi-

ation case files on which the mediator reports the outcome of the

mediation to the court. It was possible for parties to reach a full

agreement (e.g., settle all issues they had wanted to discuss), a

partial agreement (e.g., settle some of the issues they had wanted

to discuss but return to court to settle the rest), or no agreement

(e.g., settle none of the issues in their mediation and instead return

to court).

Content of mediation agreements. For parties reaching ei-

ther full or partial agreement, their mediation agreements were

coded for content, adapting a coding system previously developed

for use at this Clinic (Putz, Ballard, Arany, Applegate, &

Holtzworth-Munroe, 2012). Agreements were coded for informa-

tion, including legal and physical custody, parenting time, and

child support. Coparent communication, including aspirational

language about coparental communication (such as “parents agree

to maintain a business-like relationship”), was also coded. In

addition, referrals to counseling and provisions for child safety

were coded. Some miscellaneous provisions were coded (e.g.,

agreement to return to mediation in the future, addressing new

partners, aspirational language about parent– child relationships).

Agreements were also rated on “global” codes. One global code

assessed levels of child-related rationales stated in the entire agree-

ment (e.g., “for [child’s] benefit we agree to develop a consistent

routine and communicate with child at an age appropriate level”).

Another global code assessed the likelihood of the agreement,

taken as a whole, facilitating a positive coparenting relationship

(e.g., provisions for communication such as “parents agree to

exchange important information about [child] once per week by

phone”). A final global code assessed the likelihood of the entire

agreement facilitating child adjustment (e.g., keeping conflict low,

parents “taking it slow” with new romantic partners, young chil-

dren seeing both parents frequently).

The coding system included codes that captured whether an

issue was addressed (e.g., Did the agreement address legal cus-

tody?). These items were coded for all mediation agreements. If

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

273

CHILD-INFORMED MEDIATION

the agreement did address a topic, then agreements were coded for

further detail in a manner appropriate for that question (e.g., for

parties who specified legal custody in the agreement, the coder

went on to code how they did so—joint legal custody, sole legal

custody, or some other arrangement). The specific arrangements

could only be coded if the parties had addressed the topic in the

agreement.

3

From the 69 cases in the study, 57 agreements were available for

content coding (45 full agreements and 12 partial agreements). All

agreements were coded by a trained law student mediator or a psy-

chology graduate student. For purposes of determining reliability, 20

agreements were coded by both coders.

4

Across codes with categor-

ical data (e.g., Who gets legal custody?), the average kappa was 0.89

(range: 0.64 –1.00) and the average percent agreement was 97%

(range: 80 –100%). Across all codes with continuous data (e.g., How

much child support was paid?), the average intraclass correlation was

0.90 (range: 0.56 –1.00). For the agreements coded by both coders,

disagreements were settled by consensus of the coders.

Individual demographics. Each parent completed a basic

demographics form, reporting age, ethnicity and race, education,

employment, yearly income, and number of divorces.

3

The coding system is available from the authors (holtzwor@

indiana.edu).

4

Reliability data for all codes are available from the authors

Referred to Clinic (n = 251

cases) between October 2009

and April 2012

Declined to parcipate (n = 87 cases with reason for decline)

• Case had children 5-17 (n = 63)

24 cases, parent didn’t want to do anything extra

12 cases, reason unknown

4 cases, child already had a therapist

22 cases, parent did not want to involve children

1 case, parent thought child would refuse

• Case had children 0-4 (n = 21)

15 cases, parent didn’t want to do anything extra

4 cases, reason unknown

2 cases, parent didn’t think study would help

• Case had children of unknown ages (n = 3)

2 cases, parent didn’t want to do anything extra

1 case, reason unknown

Randomized (n = 76)

• Case had children 5-17 (n = 35)

• Case had children 0-4 (n = 41)

Assigned to CI (n =14)

• Case had children 5-17 (n = 14)

• Case had children 0-4 (n = 0)

Parcipated (n = 13)

Withdrew (n = 1; case no

showed for mediaon and

couldn’t be contacted)

Assigned to CF (n = 35)

• Case had children 5-17 (n = 9)

• Case had children 0-4 (n = 26)

Parcipated (n = 34)

Withdrew (n = 1; parents no

showed for mediaon)

Assigned to MAU (n = 27)

• Case had children 5-17 (n = 12)

• Case had children 0-4 (n =15)

Parcipated (n = 23)

Withdrew (n = 4; 2 cases no-

showed and couldn’t be

contacted; 1 case deemed not

appropriate for mediaon aer

intake; 1 case parents reconciled

prior to mediaon)

Analyzed (n = 13) Analyzed (n = 34) Analyzed (n = 22)

• Excluded from analysis:

grandmother vs. mother (n = 1)

Excluded for not meeng inclusion criteria (n = 88 cases)

• Mediators refused to mediate due to violence/abuse (n = 14)

• One or both pares did not appear for intake (n = 21)

• Children in case were over age 18 (n = 10)

• Mediaon canceled prior to intake (n = 15)

• Pares in case had no children together (n = 10)

• Pares reconciled prior to intake (n = 4)

• Children in case lived more than 1 hour away (n = 7)

• Scheduling difficules precluded study parcipaon (n = 4)

• Parent pares in case were minors (n = 1)

• Case was a terminaon of parental rights, not a divorce or

separaon (n = 1)

• Case was an adopon, not a divorce or separaon (n = 1)

Figure 1. Enrollment flow diagram.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

274

BALLARD ET AL.

Family characteristics. Each parent completed a question-

naire about their past and current family structure, including length

of time in their relationship with the other parent, number and ages

of children, and presence of a new partner.

Case characteristics. Data were gathered from the case file to

determine whether the case was a divorce case (parents had been

married) or a paternity case (parents were never married). In divorce

cases, it was also noted whether the case was an initial dissolution

(creating arrangements so the divorce could be granted) or a modifi-

cation of dissolution (returning to mediation after divorce in order to

modify arrangements made at the time of the divorce).

Procedures

Intake day. Parties attended an intake appointment approxi-

mately two weeks before their mediation. Each parent had been

mailed a description of the study and consent form prior to intake.

Rarely, cases referred to the Clinic were found to be ineligible to

mediate if there was a conflict of interest (e.g., a party had received

legal services from another clinic or person affiliated with the law

school) or if the parties had a history of severe intimate partner

violence. If the case was deemed by mediators to be eligible for

mediation and if the case fit inclusion criteria for the research

study, each parent was approached individually by a child consul-

tant to be invited to participate in the study. See Figure 1 for

various reasons that cases were not included in the study.

If both parents independently consented to study participation, the

case was randomly assigned to an intervention condition based on

the age(s) of the child(ren). If the case involved any children between

the ages of 5 and 17 years, the parents were eligible to be assigned to

all three study conditions—CI, CF, or MAU—with a case having a

one-third chance of being assigned to each condition. Parents with

younger children only (age range: 0– 4 years) were eligible for only

CF or MAU, because children under the age 5 may have had diffi-

culties completing child interviews and thus could not participate in

CI. For parents with younger children, the CF condition was more

heavily weighted in the randomization such that they had a two-thirds

chance of assignment to CF and a one-third chance of assignment to

MAU; this was done to enhance training opportunities for the grad-

uate student child consultants. Mediators and child consultants were

assigned to cases in advance of the intake, based on schedule avail-

ability, and were therefore only in the study themselves if the parties

in the case agreed to study participation.

After being assigned to a mediation condition, each parent sepa-

rately completed a research assessment and was compensated $35. If

the case was assigned to CI, the child consultant also conducted a 20-

to 30-min developmental history with each parent, separately, to

gather information to prepare for the child interview. The develop-

mental history focused on each child’s development, understanding of

the separation, and strengths and difficulties. In both CF and CI cases,

child consultants met with mediators to discuss the case and review

the case file that provided a history of the dispute.

Child interviews. In CI cases, the children (age range: 5–17

years) participated in a child interview, which took place between

intake and mediation, and was held at the psychology department.

These interviews took approximately one hour, and were com-

pleted by child consultants. Children assented to the child inter-

view, were informed that the child consultant would make sure that

the child agreed to what information the consultant would share

with their parents, and were compensated with a $10 gift card. The

child interview was designed to assess the child’s experience of the

parents’ separation and to gather information in a manner that was

therapeutic to the child (McIntosh et al., 2008). Depending on the

age and comfort level of the child, the child interview included

verbal questions, playing with dolls and doll houses, drawings,

completion of story stems, and use of other interactive materials as

appropriate for the case. The sessions were video recorded to

facilitate supervision of the child consultant and case preparation,

but the video recording was never shown to parents or mediators.

The parent who brought a child in for an interview was compen-

sated $20.

Parent feedback and mediation. Parents returned to the

Clinic for their mediation session. In MAU cases, the child con-

sultant was not present, and the parents and mediators immediately

began the negotiation phase of mediation. In CF or CI mediation,

the session began with the child consultants providing parent

feedback. Usually, at least part of the parent feedback was con-

ducted with the parents in the same room, followed by individual

meetings with each parent. Parent feedback averaged 1.35 hours

(SD ⫽ 0.44) in CF and 1.46 hours (SD ⫽ 0.40) in CI; these times

did not differ significantly, F(1, 45) ⫽ 0.61, p ⫽ .44.

Parent feedback generally consisted of the following stages.

First, child consultants reminded parents of their role in the process

(e.g., to provide helpful information about children and divorce).

Then the child consultant engaged the parents in a discussion to

“bring the child into the room.” For example, in CF cases, this

might involve looking at pictures of the child and asking parents to

describe their child and their future hopes for their child. In CI

cases, the child consultant gave an overview of the child interview

that had been conducted. Next, the child consultant discussed a

few main issues that would be helpful for the parents to consider

during the mediation process. The issues to discuss were chosen in

advance by child consultants, in consultation with mediators. In

both CF and CI, the topics chosen were based on the research

literature about improving child adjustment to divorce and on

information the child consultant had gathered about the family and

child. These messages were tailored to the individual case, but

nearly all parent feedback sessions included information about the

impact of interparental conflict on children and the need to develop

a civil coparenting relationship and stronger parenting alliance.

Examples of other messages include the need for the children to

have a strong relationship with each parent and the value of quality

versus quantity of time with the child. When appropriate, messages

also included the needs of young children to see parents frequently,

the needs of older children to spend time with peers, and the need

for a safe and secure household. Examples of messages often

delivered to parents individually included discussions about the

role of new partners or substance abuse issues. In discussing these

messages, CF parent feedback relied on the general research on

the effects of divorce on children while also considering how the

research fit the particular children and family being discussed. CI

parent feedback was primarily framed in terms of what the child

consultant heard from the child during the child interview.

After parent feedback concluded, child consultants left and

parents and mediators started the negotiation phase of mediation.

Parents could mediate parenting plans and financial arrangements,

depending on the needs of their case. Of the 138 parents in the

study, 107 were pro se. For the 31 parents who had legal repre-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

275

CHILD-INFORMED MEDIATION

sentation, 29 had their attorneys physically present during the

feedback and negotiation phases of the mediation. The other two

parents had their attorneys available by telephone for consultation

as needed. In all conditions, the negotiation phase usually con-

cluded on the same day, although sometimes parents returned for

additional sessions. Duration of mediation negotiations averaged

4.60 hours (SD ⫽ 2.16) in MAU, 6.38 hours (SD ⫽ 2.91) in CF,

and 8.09 hours (SD ⫽ 3.47) in CI. These times differed signifi-

cantly, F(2, 65) ⫽ 6.52, p ⫽ .003. A post hoc Tukey’s test showed

that mediation duration differed significantly between CI and

MAU, but not between MAU and CF or CF and CI.

When mediation negotiations ended, parents completed the par-

ent outcomes form. Parents were each compensated $30 for com-

pleting this form. Mediators completed the mediator outcomes

form. If parties reached a partial or full agreement in mediation,

the content of those mediation agreements were later coded by

graduate-level research staff, as described above in the content of

mediation agreements subsection.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in Mplus. The analyses accounted for the

clustered nature of the data (e.g., mother’s and father’s reports

from the same family) by using robust standard errors. The anal-

yses also used full information maximum likelihood methods of

estimation (a method that estimates missing values in data) so that

all of the raw data could be analyzed. This had the advantage of

including information from people with missing values (Schafer &

Graham, 2002). Continuous variables were analyzed with linear

regression analyses, and categorical variables were analyzed with

logistic regression analyses.

Data were analyzed by comparing a combined group of CI and

CF interventions to cases in MAU. Our primary concern was to

examine whether a child-informed (CF or CI) approach to medi-

ation would lead to different outcomes than MAU. Also, combin-

ing CF and CI maximized statistical power, given relatively small

sample sizes. In the same analysis, for exploratory reasons and to

more directly replicate the McIntosh et al. (2008) study, CI was

compared to CF. Where appropriate in all analyses, if mother and

father data were separable, parents were compared to each other as

well.

Results

General Presentation of the Results

In most tables, means and standard deviations are presented

separately for mothers and fathers in each intervention condition

and for the CF/CI combined (or child-informed mediation) group.

Some variables (e.g., coded content of the mediation agreement)

are at the case level, so there is no separate information for mothers

and fathers. When data were continuous, results of the compari-

sons are given as estimated differences with the 95% confidence

interval of that estimate. When data were categorical, results of the

comparisons are given as odds ratios with the 95% confidence

interval of the odds ratios. For both types of data, p values are also

given. In the tables, parent refers to differences between mothers

and fathers; these differences are not discussed in the text. Group

differences are also indicated (e.g., CF and CI vs. MAU refers to

the results comparing the CF and CI cases as one group versus the

MAU cases); we note statistically significant group differences in

the text.

Demographics and Family and Case Characteristics

We compared the groups in each intervention condition (see the

supplemental materials, Table A). Parents in cases across the

intervention conditions generally did not differ with respect to

demographics: age, education, income, duration of relationship,

duration of separation, number of times divorced, number of

children, age of oldest child, race and ethnicity, employment,

presence of new partner, attorney representation, or type of di-

vorce. There were exceptions, as anticipated, in comparisons of the

CI group to the other groups, because CI cases had to have children

age 5 or older assigned to CI. CI parents were older, reported

longer relationship durations, and reported an older age of their

oldest child relative to CF and MAU parents.

Outcome Measures: Agreement Rates

Contrary to the hypothesis, there were no significant differences

across conditions in rates of agreement, but note the high rate of

some level of agreement (80 – 85%) in all three intervention con-

ditions. Agreement rate data are in Table 1.

Parent Satisfaction and Self-Reported Outcomes

Contrary to hypotheses, no differences between CF/CI and

MAU reached statistical significance for satisfaction ratings. Com-

paring CF and CI, there were no group or parent differences in

satisfaction with the child consultants who provided their parent

feedback. Data are presented in Table 2.

As seen in Table 3, and supporting hypotheses, parents in the

combined CF/CI group were more likely than parents in MAU to

report learning something in mediation and to report that the other

parent learned something.

Table 1

Agreement Rates

Level of

agreement

Did the case reach agreement?

Odds ratio [confidence interval],

p value

MAU CF/CI CF CI

n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%)

Full (n ⫽ 45) 14 (63.6) 31 (66.0) 22 (64.7) 9 (69.2) CF/CI vs. MAU: 0.001 [⫺0.13, 0.15], p ⫽ .98

CF vs. CI: ⫺0.03 [⫺0.28, 0.21], p ⫽ .79Partial (n ⫽ 12) 5 (22.7) 7 (14.9) 5 (14.7) 2 (15.4)

None (n ⫽ 12) 3 (13.6) 9 (19.1) 7 (20.6) 2 (15.4)

Note. No differences across the interventions were found when full and partial were collapsed into one category and compared to reaching no agreement.

MAU ⫽ mediation-as-usual; CF ⫽ child-focused; CI ⫽ child-inclusive.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

276

BALLARD ET AL.

When presented with a checklist of aspects of mediation that could

have been helpful (see Supplemental Materials, Table B), relative to

parents in the MAU condition, parents in the CF/CI group were more

likely to report that a helpful aspect of the mediation was getting

information on the children. Parents in the CI group were more likely

than parents in the CF group to report that hearing about their own

children was a helpful aspect of mediation. The same list of items was

presented for parents to select the one thing that was most useful or

important about the mediation. In MAU, the most common answer for

mothers (endorsed by 25%) was being able to talk and discuss

concerns, and for fathers (23.5%), it was focusing on the children. The

most common answer for CF and CI mothers (31.8%) and fathers

(37.8%) was focusing on the children.

Mediator Outcome Data

Mediators were more satisfied at a trend level (CF/CI vs. MAU:

⫺0.14 [⫺0.30, 0.30], p ⫽ .10; CF vs. CI: ⫺0.12 [⫺0.40, 0.11],

p ⫽ .30) with their mediations in CF/CI cases (M

CF/CI

⫽ 4.37,

SD ⫽ 0.71; M

CF

⫽ 4.44, SD ⫽ 0.68; M

CI

⫽ 4/19, SD ⫽ 0.78) than

MAU cases (M ⫽ 3.90, SD ⫽ 1.00). Although no comparison with

MAU was possible (because there was no parent feedback in

MAU), mediator ratings of satisfaction with the parent feedback

sessions were generally high in both the CF (M ⫽ 4.18, SD ⫽

0.77) and the CI (M ⫽ 4.33, SD ⫽ 0.65) interventions.

Mediators generally reported thinking CI worked best for

their cases, followed by CF (see Table 4). Mediators were

mostly neutral as to whether MAU worked well, but, in 39% of

the MAU cases, mediators would have preferred a different

condition.

Mediators were asked if the child consultants’ information

about the children continued to be discussed during the medi-

ation negotiations. Only four of 60 mediators in CF reported

“not at all,” and none of 26 mediators in CI reported “not at all.”

The average rating was 3.39 (0.92) in CF and 4.00 (0.76) in CI,

Table 2

Parent Satisfaction

Measure

MAU

(n ⫽ 22)

CF/CI

(n ⫽ 47)

CF

(n ⫽ 34)

CI

(n ⫽ 13)

Estimate [95% confidence interval], p value (all

cases)M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)

Satisfaction with Process Mother 5.62 5.78 5.52 6.46 Parent: ⫺0.20 [⫺0.61, 0.21], p ⫽ .34

(n ⫽ 67) (1.75) (1.67) (1.82) (0.97) CF/CI vs. MAU: ⫺0.08 [⫺0.31, 0.15], p ⫽ .50

Father 5.53 5.53 5.41 5.85 CF vs. CI: 0.36 [⫺0.01, 0.70], p ⫽ .06

(n ⫽ 66) (1.47) (1.59) (1.64) (1.46)

Satisfaction with mediators Mother 6.48 6.28 6.18 6.54 Parent: 0.02 [⫺0.43, 0.48], p ⫽ .92

(n ⫽ 67) (0.87) (1.82) (1.90) (1.66)

Father 6.26 6.40 6.29 6.69 CF/CI vs. MAU: ⫺0.02 [⫺0.16, 0.13], p ⫽ .82

(n ⫽ 66) (1.2) (1.17) (1.34) (0.48) CF vs. CI: 0.19 [⫺0.14, 0.52], p ⫽ .26

Satisfaction with child consultants Mother NA NA 6.31 6.54 Parent: ⫺0.27 [⫺0.83, 0.29], p ⫽ .34

(n ⫽ 42) (1.07) (1.66)

Father NA NA 6.04 6.27 CF vs. CI: 0.12 [⫺0.19, 0.43], p ⫽ .46

(n ⫽ 39) (1.29) (1.01)

Satisfaction with agreement Mother 5.00 5.87 5.70 6.27 Parent: 0.15 [⫺0.23, 0.54], p ⫽ .44

(n ⫽ 56) (1.94) (0.99) (1.03) (0.79) CF/CI vs. MAU: ⫺0.13 [⫺0.37, 0.11], p ⫽ .28

Father 5.94 5.66 5.59 5.82 CF vs. CI: 0.20 [⫺0.06, 0.45], p ⫽ .13

(n ⫽ 55) (1.35) (1.19) (1.28) (0.98)

Satisfaction with not reaching

agreement

Mother 2.33 1.57 1.80 1.00 NA: too few cases to analyze

(n ⫽ 10) (1.33) (1.13) (1.30) (0.00)

Father 1.50 2.71 2.80 2.50

(n ⫽ 9) (0.71) (1.60) (1.64) (2.12)

Note. MAU ⫽ mediation-as-usual; CF ⫽ child-focused; CI ⫽ child-inclusive; NA ⫽ not available.

Table 3

Parent Report of Learning Anything (Self or Other Parent)

Measure

MAU CF/CI CF CI Odds ratio [confidence interval], p value

n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%)

Anything helpful you learned? (% reporting yes) Mother

(n ⫽ 65)

7 (35.0) 30 (66.7) 22 (68.8) 8 (61.5) Parent: 0.60 [0.34, 1.05], p ⫽ .08

Father

(n ⫽ 64)

4 (23.5) 26 (55.3) 19 (55.9) 7 (53.8) CF/CI vs. MAU: 0.66 [0.48, 0.91] p ⫽ .01

CF vs. CI: 0.88 [0.51, 1.51], p ⫽ .64

Anything helpful the other parent learned?

(% reporting yes)

Mother

(n ⫽ 39)

5 (38.5) 17 (65.4) 11 (57.9) 6 (85.7) Parent: 0.25 [0.10, 0.59], p ⫽ .002

Father

(n ⫽ 47)

1 (7.1) 11 (33.3) 6 (24.0) 5 (62.5) CF/CI vs. MAU: 0.59 [0.41, 0.86], p ⫽ .006

CF vs. CI: 1.86 [0.83, 4.19], p ⫽ .13

Note. MAU ⫽ mediation-as-usual; CF ⫽ child-focused; CI ⫽ child-inclusive.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

277

CHILD-INFORMED MEDIATION

which indicates that feedback content continued to be discussed

in mediation “sometimes” to “often.” The difference between

CF and CI was statistically significant, F(1, 43) ⫽ 4.47, p ⫽

.04.

Mediator Impartiality

Across all cases in the study, in only one case did mediators

indicate that they believed the parents had any concerns about

mediator impartiality.

5

Content of Mediation Agreements

Descriptive data for all codes are given in Table C of the

Supplemental Materials. Where data were sufficient (i.e., no cells

with 0 or 100%), group difference across the interventions were

also analyzed. Most cases addressed legal custody, with joint legal

custody being the most common arrangement (64.3% of MAU

cases and 75.0% of CF and CI cases). Most agreements addressed

physical custody, with mother given sole/primary custody in

92.9% of MAU cases and in 61.5% of CF and CI cases. Nearly all

cases addressed parenting time, with parenting time usually being

specified for the father (i.e., usually the nonresidential parent). CF

and CI cases agreed to more parenting time for the nonresidential

parent on weekdays, weeknights, and weekend nights than did

cases in MAU. There was no difference in the number of weekend

days across conditions (most families chose to alternate week-

ends).

Regarding provisions about coparental communication and con-

flict, parents in CF and CI cases were more likely than parents in

MAU cases to address communication between parents. CF and CI

agreements included more aspirational language about coparental

communication, were more likely to agree not to disparage or

insult each other, and were more likely to prohibit fighting or

conflict in their relationship. Between one third and one half of

cases addressed child support; this did not differ significantly

across conditions.

6

Fathers generally paid child support. There was

no difference in the amount of child support paid per week across

the conditions.

Referrals to counseling were uncommon and did not differ

across intervention groups. Safety provisions were likewise

uncommon, and only one case had a court-appointed special

advocate or a guardian ad litem. In the miscellaneous provi-

sions, cases split fairly evenly on whether provisions were

included for returning to mediation. Agreements rarely ad-

dressed the presence of new partners, but CI cases were more

likely to do so than CF cases (CF and CI did not differ from

MAU on this item). Parents in CF and CI cases were more

likely to include aspirational language about the importance of

parent– child relationships than parents in MAU cases. Cases in

CF and CI groups created longer mediation agreements, in

number of pages, than cases in MAU; we included this count as

an indirect measure of agreement complexity.

On the global codes, relative to MAU cases, CF and CI cases

were judged to include more child-related rationales, and CI cases

had more rationales than CF cases as well. CF and CI cases were

judged to include more provisions to improve the coparental

relationship and to facilitate child adjustment to divorce compared

to MAU cases.

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence that child-informed

mediation interventions, designed to include the child’s perspec-

tive and to motivate parents to focus on their children’s needs, are

liked and are perceived as helpful by parents and mediators. They

result in mediation agreements that are judged as being more likely

than MAU agreements to facilitate positive child adjustment to

divorce.

Contrary to our hypotheses, no differences were found in me-

diation party satisfaction levels across all conditions, possibly

because satisfaction was generally high, as found in previous

research at this Clinic (Pettersen, Ballard, Putz, & Holtzworth-

Munroe, 2010). Mediators tended to be more satisfied with CF and

CI than MAU and were satisfied with CI and CF parent feedback

sessions. Furthermore, mediators usually thought that CF and CI

mediations worked well for their cases, rarely thought that CF and

5

This was a child-focused mediation case. The mediators both reported

that the father accused the mediators of not being impartial, that the

accusation did not appear to have anything to do with the participation of

a child consultant, and that they believed the father was attempting to

manipulate the mediation process.

6

If a parent was in arrears in paying child support, they were often not

legally allowed to include child support provisions in their mediation

agreement.

Table 4

Mediators Report of Utility of Case Assignment

How well did you think the assigned condition worked

for this case?

Measure Very well n (%) Neutral n (%) Not well n (%)

Mediators in MAU (n ⫽ 36) 5 (13.8) 17 (47.2) 14

a

(38.9)

Mediators in CF (n ⫽ 63) 33 (52.4) 23 (36.5) 7

b

(11.1)

Mediators in CI (n ⫽ 26) 20 (76.9) 5 (19.2) 1

c

(3.8)

Note. MAU ⫽ mediation-as-usual; CF ⫽ child-focused; CI ⫽ child-inclusive.

a

Of the mediators who reported that MAU did not work well and expressed a preference, five wished for the

mediation to be in the CI condition and seven wished for mediation to be in the CF condition.

b

Of the

mediators who reported that CF did not work well, none specified what condition they would have wanted

instead.

c

The mediator who thought that CI did not work well thought the case would have been better as a

MAU because “the parents were stuck in their ways.”

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

278

BALLARD ET AL.

CI was not helpful, and often wanted their MAU cases to be

assigned to CF or CI. Anecdotally, mediators would let child

consultants know that they were pleased child consultant could

deliver messages to parents that mediators, as neutral parties, did

not feel comfortable delivering. Another possible reason for ap-

proval of CF and CI was that parents in CI and CF were more

likely than parties in MAU to report that they and their partners

learned something helpful. Parents in the CI and CF intervention

groups were more likely than parents in MAU to endorse that

getting information about their children and hearing about their

children was helpful. And mediators reported that the parent feed-

back information continued to be used in the negotiation phase of

the mediation process. Because mediations were not observed for

research purposes, it is not known whether feedback information

continued to be used in negotiations because of how mediators

behaved or because of parents choosing to address those topics

again. Either would acceptable from a child-informed mediation

perspective.

Of import, these gains were realized without negatively affect-

ing perception of other important aspects of mediation, such as the

process being fair, being able to discuss concerns, feeling sup-

ported, and having neutral mediators (as reported by parents and

mediators). One potential concern about a child consultant offering

advice to parents during the mediation process was that parents

may have perceived that mediators were aligned with the child

consultant and were therefore not neutral. That does not appear to

have happened.

Cases in CF and CI and cases in MAU were equally like to reach

agreement in mediation, contrary to our hypothesis. This may have

occurred because the small percentage of families not reaching

agreement may have been in greater conflict and needed much

more assistance than the additional hour or so of child consultant

time. Another possibility is that child consultant feedback “stirred

up” more issues for consideration, helping some families to settle

and complicating negotiations for others.

However, cases receiving the CI and CF interventions created

mediation agreements that differed in important ways from

cases in the MAU condition. Parents in CF and CI agreed to

more weekdays, weeknights, and weekend nights for the non-

residential parent, increasing the overall amount of time spent

between the nonresidential parent and children. Although con-

tact alone does not substantially affect child outcomes, it is

necessary to have sufficient contact between parent and child

for the nonresidential parent to feel emotionally close and to

engage in authoritative parenting, both of which improve child

outcomes (Amato & Gilbreth, 1999). Also, when asked to

reflect on their childhoods, young adults have generally re-

ported wishing they had more time with the nonresidential

parent (Fabricius & Hall, 2000). Interventions such as CF and

CI, which provide more time for the child’s relationship with

the nonresidential parent, may therefore improve child out-

comes and alleviate child distress at losing a parent to divorce

or separation.

Because conflict between parents is one of the strongest

predictors of child outcomes following divorce (Kelly & Em-

ery, 2003; Lansford, 2009), it was heartening to see that parents

in CF and CI cases were more likely to address coparental

communication in their agreements than parents in MAU. They

made agreements that included more aspirational language

about coparental communication, often incorporating ideas

from the child consultants’ feedback, such as maintaining a

“business-like relationship” or only communicating in particu-

lar ways (e.g., agreeing to only communicate by text message).

Parents in CF and CI were also more likely to agree not to fight

or insult each other. Keeping conflict low was an idea addressed

in almost all feedback sessions, and that idea appears to have

been reflected in the mediation agreements.

Further evidence for the difference in mediation agreements

between MAU and CF/CI cases comes from the global ratings

of the agreements. CF and CI cases included more child-related

rationales for their provisions, possibly indicating that parents

gave more thought as to why they should make the arrange-

ments they were making. The provisions in the mediation

agreements of CF and CI cases, if followed as written, were also

judged to be more likely to facilitate a positive coparental

relationship (e.g., agreeing not to fight) and to facilitate child

adjustment to divorce (e.g., frequent contact with the nonresi-

dential parent).

Certain kinds of mediation agreement provisions may have

been helpful to child adjustment, but were rare in all agreements

and not more frequent in CF and CI cases. These provisions

include safety provisions and counseling referrals. These find-

ings are consistent with prior research at this Clinic, and other

clinics, that parents usually do not choose to include such

provisions in their mediation agreements (Putz et al., 2012;

Beck, Walsh, & Weston, 2009).

One methodological strength of the current study was the

presence of a meaningful control condition (MAU). Prior re-

search on the CF and CI interventions did not employ an MAU

control condition, so comparison was only possible between the

two child-oriented intervention conditions. It is unknown in the

McIntosh et al. (2008) study whether CF and CI were improve-

ments over mediation without the child-specific components, an

important question to answer because of the extra time and

resources involved in implementing child-informed approaches.

The present findings suggest the benefits of child-informed

mediation over MAU. The issue of meaningful comparisons

was further confounded in McIntosh’s study by having the

mediators deliver the CF intervention and a child consultant

deliver CI. This means that the extra time and attention from the

child consultant in CI alone could have caused the differences

between CF and CI in Australia. In the present study, child

consultants delivered the parent feedback in both CF and CI,

and there were few differences between the CF and the CI

conditions. However, some of the lack of differences between

CF and CI in the present study could be due to the use of student

child consultants (and mediators), because they have less im-

pact than seasoned professionals. The lack of differences be-

tween CF and CI might also be due to limited statistical power,

given our small CI sample. Thus, more research will be neces-

sary to determine if there truly are incremental benefits to CI

over CF that justify the extra time and effort of conducting child

interviews.

Another primary strength of the current study was a design

that included random assignment to intervention conditions.

Rare in research in family law, random assignment is the

criterion standard for intervention studies, because it allows

researchers to draw a causal relationship between intervention

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

279

CHILD-INFORMED MEDIATION

conditions and outcomes (Holtzworth-Munroe, Applegate,

D’Onofrio, & Bates, 2009). Randomization worked fairly well

to equalize the intervention groups on individual, family, and

case demographic variables. Partial failures of randomization

can be explained by recruitment procedures that caused the CI

group to be older (with longer relationship duration and older

children).

A third study strength was that nearly every case deemed

eligible for mediation was invited to participate in the study. Thus,

a broad range of cases were included in this research—from

parents who had had very brief relationships, were never married,

and were creating initial parenting time arrangements to parents

modifying parenting arrangements made after a divorce that oc-

curred years ago. In addition, we included a broader range of child

ages than examined in previous research on CI and CF (birth to 17

years in the present study versus ages 5–16 years in McIntosh et

al., 2008). We did not screen out parents thought to have inade-

quate “ego maturity” (McIntosh et al., 2008), instead permitting a

broader range of cases to enroll. By providing the intervention to

families with very young children, there was the potential to affect

the trajectories of child outcomes for children who may never

remember their parents’ separation. Broadening the scope of re-

cruitment may also enhance the generalizability of the interven-

tions in other mediation clinics that serve a wide variety of fam-

ilies. Participants in this study were generally low income, often

high conflict, and often experiencing multiple stressful life circum-

stances. These factors place these families at particularly high risk

of negative outcomes after divorce, and are a population most in

need of services.

There are also important limitations to this research study.

Despite recruiting for more than two years, only 69 families

consented to research and completed the mediation process.

This is a relatively small sample, particularly when spread

across three conditions, which limits the power of statistical

analyses that may be conducted. Because of age restrictions on

randomization into CI, the 69 cases were not evenly distributed

across all three conditions, and relatively few CI cases were

completed. One potential result of the small sample is that

existing group differences are currently not significant or are at

a trend level that may turn out to be significant in future studies

with larger samples. Data from a small sample are also more

likely to yield false-positives that do not survive replication in

future studies. The small sample size was driven, in part, by the

fact that roughly half of the families approached refused to

participate, but these refusals were unequally distributed across

ages. Two thirds of families with only younger children (all age

4 or younger) consented, while only one third of families with

older children (ages 5 or older) consented. Many parents who

had older children cited not wanting to involve their children in

the process, so the child interview component appears to have

discouraged some families from participating. Future research-

ers will need to consider how to address this, and this finding

suggests a potential limitation on the acceptability of CI to

parents in the United States.

As with any study at one site, our sample represents a small

slice of the divorcing population and one particular style of

mediation. Important factors, such as attorney representation,

can vary widely among jurisdictions (e.g., Beck et al., 2010).

Also, drawing from people who live in south-central Indiana,

this study lacked much racial and ethnic diversity. Because of

how difficult it was for low-income parties to return to the

Clinic for multiple mediation sessions (e.g., inability to take

additional days off work), the mediations usually occurred in a

single session. This is a potential drawback, because parties

may have become tired by the end of a long session. Outcomes

may have differed if the mediations had proceeded in smaller,

more frequent increments.

This study is also limited in that only the immediate outcomes

from the interventions were available to analyze. Long-term

follow-up of the families who participated is a critical step in

determining if the CF and CI interventions produce sustained

benefits to these families. A longitudinal study of the families who

participated is underway, but data are not yet available for analy-

sis. The longitudinal data will include measures of parent and child

functioning, interparental conflict, and child adjustment to divorce

that will allow an empirical examination of the hypothesis that the

agreements reached in CF and CI mediations ultimately result in

better child outcome.

Another potential study limitation is that the mediators and

child consultants were students, not experienced professionals.

It is controversial whether less experienced therapists in psy-

chotherapy provide less effective services (Montgomery,

Kunik, Wilson, Stanley, & Weiss, 2010; Stein & Lambert,

1995), and students were provided extensive supervision, but

this issue may still have affected the mediations and feedbacks.

A related issue is that, to determine if an intervention is being

delivered in a competent manner, many program evaluation

studies include measures of intervention adherence to a treat-

ment manual and competence. This study did not include such

measures. Although students were observed in most of the

feedbacks and mediations, they were not formally rated for

adherence or competence. One of the difficulties was that the

mediation sessions could not be recorded for fear of creating a

record of the confidential mediation that a parent or attorney

may try to obtain as evidence in a trial. Because of this

limitation, in future work, adherence and competence will have

to be measured live—a much more difficult task.

Conclusion

The CF and CI interventions were well accepted by parents and

mediators, and they led to mediation agreements that should be

helpful to family functioning as parents and children adjust to life

after separation or divorce. Parents seem to be able to hear the

messages of the child consultants (e.g., ideas such as a “business-

like coparenting relationship” are often included verbatim in me-

diation agreements), and those messages are kept salient in the

mediation process even after feedback ends. Overall, this random-

ized controlled trial represents a promising next step from the

research conducted in Australia for family law professionals seek-

ing brief interventions to improve the outcomes of divorcing

families.

References

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children.

Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1269 –1287. doi:10.1111/j

.1741-3737.2000.01269.x

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

280

BALLARD ET AL.

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new

developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666. doi:

10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. G. (1999). Nonresident fathers and children’s

well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61,

557–573. doi:10.2307/353560

Beck, C. J. A., Walsh, M. E., Ballard, R. H., Holtzworth-Munroe, A.,

Applegate, A., & Putz, J. W. (2010). Divorce mediation with and

without legal representation: A focus on intimate partner violence and

abuse. Family Court Review, 48, 631– 645. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617

.2010.01338.x

Beck, C. J. A., Walsh, M. E., & Weston, R. (2009). Analysis of mediation

agreements of families reporting specific types of intimate partner abuse.

Family Court Review, 47, 401– 415. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2009

.01264.x

Carbonneau, T. E. (1986). A consideration of alternatives to divorce

litigation. University of Illinois Law Review, 4, 1119 –1192.

Emery, R. E., Laumann-Billings, L., Waldron, M. C., Sbarra, D. A., &

Dillon, P. (2001). Child custody mediation and litigation: Custody,

contact, and coparenting 12 years after initial dispute resolution. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 323–332. doi:10.1037/0022-

006X.69.2.323

Emery, R. E., Otto, R. K., & O’Donohue, W. T. (2005). A critical

assessment of child custody evaluations: Limited science and a flawed

system. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6, 1–29. doi:

10.1111/j.1529-1006.2005.00020.x

Emery, R. E., Sbarra, D., & Grover, T. (2005). Divorce mediation: Re-

search and reflections. Family Court Review, 43, 22–37. doi:10.1111/j

.1744-1617.2005.00005.x

Emery, R. E., & Wyer, M. M. (1987). Child custody mediation and

litigation: An experimental evaluation of the experience of parents.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 79 –186. doi:0022-

006X/87

Fabricius, W. V., & Hall, J. A. (2000). Young adults’ perspectives on

divorce: Living arrangements. Family & Conciliation Courts Review,

38, 446 – 461. doi:10.1111/j.174-1617.2000.tb00584.x

Fackrell, T. A., Hawkins, A. J., & Kay, N. M. (2011). How effective are

court-affiliated divorcing parents education programs? A meta-analytic

study. Family Court Review, 49, 107–119. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617

.2010.01356.x

Hetherington, E. M., Bridges, M., & Insabella, G. M. (1998). What

matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between

marital transitions and children’s adjustment. American Psychologist,

53, 167–184. doi:0003-066X/98

Holtzworth-Munroe, A., Applegate, A. G., D’Onofrio, B., & Bates, J.

(2009). Family dispute resolution: Charting a course for the future.

Family Court Review, 47, 493–505. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2009

.01269.x

Holtzworth-Munroe, A., Applegate, A. G., D’Onofrio, B., & Bates, J.

(2010). Child Informed Mediation Study (CIMS): Incorporating the

children’s perspective into divorce mediation in an American pilot study.

Journal of Family Studies, 16, 116 –129. doi:10.5172/jfs.16.2.116

Kelly, J. B., & Emery, R. E. (2003). Children’s adjustment following

divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations: An Inter-

disciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 52, 352–362. doi:

10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00352.x

Lansford, J. E. (2009). Parental divorce and children’s adjustment. Per-

spectives on Psychological Science, 4, 140–152. doi:10.1111/j.1745-

6924.2009.01114.x

Manning, W. D., Smock, P. J., & Majumdar, D. (2004). The relative

stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Re-

search and Policy Review, 23, 135–159. doi:10.1023/B:POPU

.0000019916.29156.a7

McIntosh, J. (2000). Child-inclusive divorce mediation: Report on quali-

tative research study. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 18, 55–69. doi:

10.1002/crq.3890180106

McIntosh, J. (2007). Child inclusion as a principle and as evidence-based

practice: Applications to family law services and related sectors. AFRC

Issues, 1, 1–23. Retrieved from http://www.aifs.gov.au/afrc/pubs/issues/

issues1/issues1.pdf

McIntosh, J., Long, C. M., & Wells, Y. D. (2009). Children beyond

dispute: A four year follow up study of outcomes from Child Focused

and Child Inclusive post-separation family dispute resolution. Victoria,

Australia: Family Transitions.

McIntosh, J. E., Wells, Y. D., Smyth, B. M., & Long, C. M. (2008).

Child-focused and child-inclusive divorce mediation: Comparative out-

comes from a prospective study of postseparation adjustment. Family

Court Review, 46, 105–124. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2007.00186.x

Milne, A. L., Folberg, J., & Salem, P. (2004). The evolution of divorce and

family mediation. In J. Folberg, A. L. Milne, & P. Salem (Eds.), Divorce

and family mediation (pp. 3–25). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Montgomery, E. C., Kunik, M. E., Wilson, N., Stanley, M. A., & Weiss, B.

(2010). Can paraprofessionals deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy to

treat anxiety and depressive symptoms? Bulletin of the Menninger

Clinic, 74, 45– 62. doi:10.1521/bumc.2010.74.1.45

Pettersen, M. M., Ballard, R. H., Putz, J. W., & Holtzworth-Munroe, A.

(2010). Representation disparities and impartiality: An empirical anal-

ysis of party perception of fear, preparation and satisfaction in divorce

mediation when only one party has counsel. Family Court Review, 48,

663– 671. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2010.001340.x

Putz, J. W., Ballard, R. H., Arany, J. G., Applegate, A. G., & Holtzworth-

Munroe, A. (2012). Comparing the mediation agreements of families

with and without a history of intimate partner violence. Family Court

Review, 50, 413– 428. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2012.01457.x

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state

of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X

.7.2.147

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., & for the CONSORT group.

(2010). CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting

parallel group randomized trials. British Medical Journal, 340, 698–

702. doi:10.1136/bmj.c332

Shaw, L. A. (2010). Divorce mediation outcome research: A meta-analysis.

Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 27, 447– 467. doi:10.1002/crq.20006

Simpson, B. (1989). Giving children a voice in divorce: The role of family

conciliations. Children & Society, 3, 261–274. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860

.1989.tb00351.x

Stein, D. M., & Lambert, M. J. (1995). Graduate training in psychotherapy:

Are therapy outcomes enhanced? Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 63, 182–196. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.63.2.182

Taylor, A. (1997). Concepts of neutrality in family mediation: Contexts,

ethics, influence, and transformative process. Mediation Quarterly, 14,

215–236. doi:10.1002/crq.3900140306

Webb, S. (2008). Collaborative law: A practitioner’s perspective on its

history and current practice. Journal of the American Academy of Mat-

rimonial Lawyers, 21, 155–169.

Received January 18, 2013

Revision received April 29, 2013

Accepted April 30, 2013 䡲

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

281

CHILD-INFORMED MEDIATION