:

aging in popular television content

. . , . , ,

artur tofan, anne-marie depauw, and ariana case

with assistance from

angel choi and kevin yao

Media, Diversity, &

Social Change Initiative

in partnership with

2

T

he goal of the present investigation is to assess the prevalence and portrayal of senior characters in popular

television programming. The study is comprised of two samples of popular television series airing between June

1, 2016 and May 31, 2017. Popularity was determined based on Nielsen Average Audience Rating Percentage.

The first sample includes the 50 most popular television series among viewers age 18-49. The second sample includes the

50 most popular television series among viewers age 65 and older. It is important to note that 28 series are popular with

both sets of viewers and appear in analyses for both samples. We discuss overall trends for the 72 unique series across

both samples. Due to the overlap between samples and the small number of characters included in some analyses, how-

ever, caution should be exercised when interpreting differences between the 18-49 and 65-plus samples.

Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used in the study to evaluate the portrayal of senior characters. For

quantitative measures, one episode of each series was analyzed and every speaking or named character on screen was

evaluated. Following this, a series of measures assessed the depiction of characters age 60 and older across these sto-

ries. Finally, a qualitative analysis of main (i.e., leading, supporting, and series regular) senior characters was performed.

#1 What is the Demographic Profile of Seniors on Popular TV?

Senior characters represent less than 10% of all speaking characters across the 72 unique shows. Out of 1,609 speaking

characters evaluated, a total of 9.4% (n=151) were age 60 and above in the 72 unique TV series analyzed. This point sta-

tistic is below (-10.5%) U.S. Census (19.9%).

Only 3 shows of the 72 unique series evaluated featured senior characters within +2% points of U.S. Census (19.9%).

Over one fifth of the 72 episodes studied (22%, n=16) failed to include one senior speaking character on screen.

Seniors account for a mere 8.2% (n=50) of all series regulars, which did not differ by sample type.

Gender. As age increases, the percentage of female speaking characters on screen significantly decreases. Females were

cast in less than 30% (27.8%) of all roles involving characters 60 years old or over. A full 38 (52.8%) of the 72 programs

studied were missing senior women altogether on screen.

Turning to series regulars, of the 72 unique episodes evaluated, a full 41.2% were female and 58.8% were male.

Race/Ethnicity. Across the 72 unique shows, 72.2% of senior characters are White, 14.6% Black/African American, 6.6%

Hispanic/Latino, 1.3% Asian, and 5.3% from Mixed Race/Other groups. There were no meaningful differences by sample in

the proportion of senior characters within each racial/ethnic group.

Combined, 27.8% of the senior characters across 72 popular shows were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups

(i.e., Black, Latino, Asian, Other).

3

Not one show across 72 popular series featured a senior female Asian speaking character. Hispanic/Latino female seniors

were missing from 70 out of 72 shows. Finally, 64 series did not feature one Black senior female speaking character.

Across 72 popular shows, 28.2% of senior male series regulars were from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group. In the

total sample, the percentage of underrepresented senior female series regulars was 27.3%.

LGBT. Focusing on the overall sample of 72 shows, seniors accounted for 4 out of the 48 LGBT series regulars. Of these,

3 were male (2 bisexual, 1 gay) and 1 was a transgender female. In terms of invisibility, 68 out of 72 shows were devoid of

senior LGBT series regulars.

Behind the Camera. A total of 296 content creators worked behind the scenes across the 72 unique episodes coded.

Of these, 83.1% were male and 16.9% were female. A mere 8.2% were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups and

12.6% were 60 years of age and above.

Focusing on directors, a total of 75 helmers were attached to the sample of 72 episodes. One-quarter (25.3%, n=19) were

age 60 or older. Two directors age 60 and older were female and 17 were male. Combining age, race/ethnicity, and gen-

der, only 5 were underrepresented directors (4 males, 1 female) age 60 or above across the 72 shows.

A full 121 writers were credited across the 72 episodes, with 5% (n=6) age 60 or above. One of these senior writers was fe-

male. Looking across gender, race/ethnicity, and age, 0 writers 60 years of age and above were underrepresented across

the 72 top series among 18-49 year olds and audiences 65 and above.

Finally, we assessed demographic attributes of showrunners associated with the 72 programs. Of the 100 showrunners,

11% were 60 years of age or older. Ten of these individuals were male and 1 was female. No underrepresented showrun-

ners aged 60 and above worked behind the camera across the 72 episodes coded.

#2 What is the Employment Status of Seniors on Popular Television?

Every senior speaking character was evaluated for the presence of a job. Overall, 70.8% (n=109 of 154) of seniors were

depicted with an occupation. Females (62.8%) were less likely than males (73.9%) to be shown working across the sam-

ple.

Across 72 popular shows, 82.8% of high clout positions were held by male seniors and 17.1% were held by females. This

is a gender ratio of 4.83 males to every one female. Nearly one-third (31.4%, n=11) of high-status occupational roles were

held by characters from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

Across the sample, the majority of female seniors with clout were women from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

Employed main senior characters across the sample were more likely to be in supportive collegial relationships (42.9%)

than in strained relationships (10.7%). Male characters (46.5%) were more likely than female characters (30.8%) to be

depicted in supportive collegial relationships.

4

#3 What is the Health Profile of Senior Characters on Television?

A total of 7.8% (n=12 of 154) of senior characters had a health issue across the 72 series evaluated. Every one of these

characters was male. One-quarter (n=3) of seniors with a health issue were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

Few senior characters died across the samples of content. Just 5.8% (n=9) of senior characters perished in the 72 pro-

grams sampled. Across the sample, only male senior characters died. All of the seniors were felled by violence. This

included being shot, stabbed, attacked by a bear, hanged, or the victim of an explosion.

#4 What Type of Relationships do Senior Characters Have with Their Families?

The nature of familial relationships was assessed for leading, supporting, and series regular senior characters across the

72 series evaluated. Of 70 main senior characters in the sample 44.3% (n=31) had family relationships and 51.4% (n=36)

lacked these ties.

Senior characters’ familial ties were further examined to determine whether the character was a grandparent. Across

72 popular shows, 15.6% (n=24 of 154) of seniors were grandparents. Of senior grandparents, 29.2% were female, and

70.8% were male.

#5 What is the Media and Technology Use Profile of Senior Characters on Television?

Looking first at media consumption, 20% of main senior characters used any form of media while 80% did not. Among

seniors in the sample, half (n=7) of seniors using media read or watched news content, and 57.1% (n=8) watched televi-

sion.

Nearly half (47.1%, n=33) of main senior characters across all 72 series used some form of technology. One-third of female

seniors (33.3%, n=6 of 18) were shown with technology versus half of male seniors (51.9%, n=27 of 52).

Across the sample, 72.7% (n=24) of the seniors were shown utilizing a cell phone and more than one-third (39.4%, n=13)

engaged with a computer.

#6 What Type of Language is Used to Refer to Senior Characters on Television?

A total of 39 series across all 72 evaluated featured main senior characters. Of those series, 41% (n=16 of 39) had one or

more ageist comments.

Across all 16 series with an ageist comment, half of the programs were dramas and half were comedy or animated series

(i.e., The Simpsons).

5

Ageist comments were sorted into descriptive categories. The largest category was comments that reference age in a

general or non-specific manner. Thirteen or 81.3% of series with ageist comments across the full sample fit into this

category. Examples of comments in this category include: “Your parents are old. Anything unspeakable was finished by

9:30,” “Things just sound creepier when you’re old,” “You like the color? It’s called ‘ancient ivory,’ like you,” or referring to

a character as “Caveman.”

The second category related to physical and mental well-being. Here, 50% (n=8) of series with ageist comments refer-

enced senior characters’ health or abilities. This category included comments such as: “I need to write down all these

precious moments before I forget them,” or “We’re elderly, so, uh, you know, we’ll just sit here and suffer.”

A handful of other comments related to appearance and traditionality. Just 12.5%, (n=2) of series with ageist comments

mentioned these aspects of aging. One example of this was referring to a character as a “wrinkled old bastard.” Finally, 3

series (18.8%) contained ageist comments related to death.

Shows without a 60-plus writer were more likely to feature an ageist comment than shows with senior writers. A full

81.2% (n=13) of series with ageist comments were written by a writer younger than 60, while 18.8% (n=3) of series with

an ageist comment had a senior writer.

The same held true for showrunners. Three-quarters (n=12) of series with ageist comments had showrunners younger

than age 60. The remaining 25% of series with ageist comments had showrunners age 60 or older.

6

T

he global population is aging, and the U.S. is no exception. Representing 17.8% of Americans in 2010, individuals

age 60 and older were 19.9% of the U.S. population in 2015.¹ As the number of older Americans increases, so

do challenges related to health care, the workforce, housing, and public entitlement programs, to name a few.²

Alongside these subjects, an aging citizenship confronts our beliefs and conceptions about what it means to grow older.

One vehicle that may contribute to views on aging is entertainment. Storytelling may communicate ideas or stereotypes

about seniors that capture the attention of audiences. Media—especially television—claims a large part of the lives of

older individuals. Nielsen estimates that in the first quarter of 2017, Americans age 65 and older spent over 50 hours per

week watching TV.³

Given the time seniors devote to this medium, it is important to consider the messages TV transmits regarding its audi-

ence. This is particularly the case following our previous studies of top-grossing movies and Academy Award-nominated

films. Conducted in partnership with Humana, these reports revealed that senior characters were rare and ridiculed

in mainstream and critically-acclaimed films. Thus, the goal of the present investigation is to assess the prevalence and

portrayal of senior characters in popular television programming.

To that end, the study is comprised of two samples of popular television series airing between June 1, 2016 and May 31,

2017. Popularity was determined based on Nielsen Average Audience Rating Percentages during this time frame. The first

sample included the 50 most popular television series among viewers age 18 to 49 (see Appendix A for the list of shows).

The series were drawn from broadcast (i.e., ABC, CBS, NBC, CW, FOX), basic cable (i.e., AMC, Comedy Central, FX), and

premium cable outlets (i.e., HBO). This sample was chosen to assess the agenda mainstream content may be setting

about the lives of seniors on screen.

The second sample includes the 50 most popular television series among viewers age 65 and older (see Appendix B for

the list of shows). The vast majority of these programs aired on broadcast channels and only two series aired on basic

cable (i.e., TNT). This content was analyzed to understand how senior viewers may see themselves and their stories about

aging reflected in television narratives.

While two samples of content were analyzed, it is important to note that 28 series were popular with viewers 18-49 and

those 65 and older. Because of this, we present the findings in two specific ways. First, we discuss overall trends for the

72 unique series across both samples.

Second, the differences between samples are noted when they deviate by 5% on key measures. This comparison facil-

itates an understanding of the frequency and nature of portrayals viewers are exposed to in both demographic groups.

Due to the overlap between samples and the small number of characters included in some analyses, however, caution

should be exercised when interpreting differences between the 18-49 and 65-plus samples.

Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used in the study to evaluate the prevalence and portrayal of senior char-

7

acters in popular TV content. Quantitatively, we assessed every speaking or named character on screen in one episode of

the 72 series in the sample. Speaking characters were evaluated across a variety of demographic attributes and other

manifest features. Following this, a series of questions assessed the depiction of characters age 60 and older. Finally,

an in-depth qualitative analysis of main senior characters was performed. Main senior characters consisted of leading

and supporting senior characters and senior series regulars. For this deeper dive, a second episode of the series was

included to provide greater contextual assessment of characters 60 and above.¹

The results are reported across multiple areas of inquiry. The prevalence and demographic profile of senior characters is

overviewed first. Here, we contextualize the portrayal of seniors on screen by focusing on their frequency as well as the

distribution of depictions by gender, race/ethnicity, LGBT standing, employment patterns, and workplace participation.

Next, the health status of senior characters is explored including the use of assistive devices and death of senior charac-

ters. The relationships of senior characters also are assessed with a focus on family relationships, and a specific look at

grandparent status. Fifth, the media use and technology profile of seniors is explored. Finally, the use of ageist language

toward and about senior characters is analyzed.

One additional caveat is important to note. All demographic groups were included in the analyses. Due to the fact that

this paper is on aging, the findings and comparisons focus primarily on characters 60 and above. Only a few deviations

from other groups are presented in the results. For interested readers, however, we include complete demographic infor-

mation in all the tables below.

8

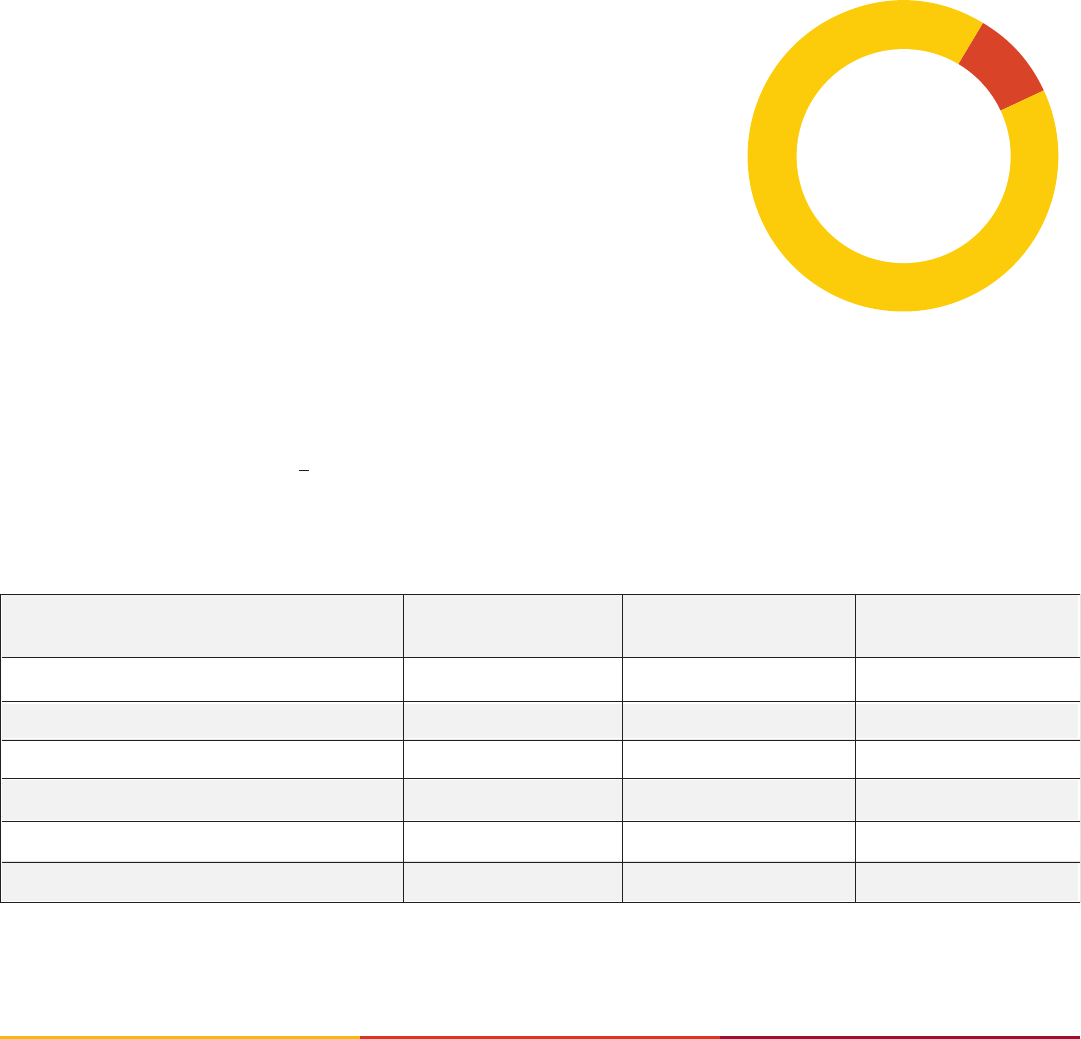

Out of 1,609 speaking characters evaluated, a total of 151 (9.4%) were age 60 and

above in the 72 unique TV series analyzed. This point statistic is below (-10.5%)

U.S. Census (19.9%).¹¹ Very little deviation appeared across the samples. Just

9.5% (n=107) of characters were seniors in shows popular with viewers 18-49 and

9.8% (n=112) of characters were seniors in programs popular with viewers 65 and

older (see Table 1).

Across the five age groups shown in Table 1, only one meaningful difference

emerged. Zero to 20 year olds (13.1%) were more likely to be depicted in shows

popular with 18 to 49 year olds than in shows popular with audiences 65 years of

age and older (7.6%).

Overall point statistics for seniors on screen are informative. However, they do not

reveal the density of senior characters across and within popular TV programming.

For instance, some shows may feature only one or two senior characters whereas

others may saturate the cast with characters 60 and above. Only focusing on a

total percentage misses this important deviation. To capture this variability, two

additional analyses were executed.

The first analysis focused on proportional representation. Proportional representation captures the number of shows

featuring senior characters within +2 percentage points from U.S. Census (19.9%).¹² As illustrated in Table 2, only 3 of the

72 unique episodes evaluated met this criterion. The samples each featured 2 programs with proportional representation

TABLE 1

SPEAKING CHARACTERS’ AGE BY SAMPLE TYPE

AGE GROUPING

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

OVERALL

0-20 YEARS

21-39 YEARS

40-59 YEARS

60 YEARS AND ABOVE

# OF CHARACTERS

# OF TV SHOWS

13.1%

46.2%

31.2%

9.5%

1,129

50

7.6%

5 0.8%

31.8%

9.8%

1,147

50

11.4%

47.2%

31.9%

9.4%

1,609

72

Note: Each column sums to 100% within age grouping. The overall column represents unique shows in the sample. Twenty-eight of

the same shows are included in both samples (18-49 years, 65 years and above) of popular content.

Out of

speaking

characters...

were age 60

and above

1,609

151

(9.4%)

#1

9

(see Table 2). The second analysis explored invisibility. Here, the total number of programs that were completely devoid

of senior speaking characters was calculated. Over one fifth of the 72 episodes (22%) failed to include one senior speaking

character on screen. Nine (18%) shows popular with 18-49 year olds and 10 (20%) shows popular with audiences 65 and

older did not portray a single senior speaking character on screen (see Table 2).

Moving from all speaking characters, we also measured the age of series regulars. A series regular is usually depicted

across multiple episodes of a TV series.¹³ As shown in Table 3, 8.2% (n=50) of all series regulars were seniors, which did not

differ by sample type. Seniors account for 7% (n=32) of series regulars in shows popular with 18 to 49 year olds and 9.8%

(n=39) of series regulars in shows popular with those 65 years of age and older.

Two additional findings pertaining to series regulars by age grouping are important to note. Zero to 20 year olds were more

likely to be series regulars in the 18-49 sample than in the 65 and older sample. A reverse trend emerged for 21-39 year olds.

Popular Shows

18-49 yr olds

50

Popular Shows

65 yrs & above

50

50

42

had NO Senior

Black or African

American females

had NO Senior

Asian females

had NO Senior

Hispanic females

49

50

45

had NO Senior

Black or African

American females

had NO Senior

Asian females

had NO Senior

Hispanic females

48

Proportional

representation

of senior

characters

NO senior

characters

Unique series

72

72

64

had NO Senior

Black or African

American females

had NO Senior

Asian females

had NO Senior

Hispanic females

70

TABLE 2

PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION & INVISIBILITY OF SENIOR CHARACTERS

ACROSS TWO SAMPLES

10

In sum, senior characters were underrepresented—relative to U.S. Census—on screen in popular TV shows. This is true of

speaking characters as well as series regulars. Further, few shows portray proportional representation of senior characters

and over a fifth were completely missing the senior demographic on screen. In the next section, we contextualize these find-

ings by examining how age grouping intersects with gender, race/ethnicity, and sexuality across the two samples of TV content.

Gender. Just over 40% of the speaking characters evaluated across the 72 unique shows were female, which did not differ

by sample type (see Table 4). This translates into a gender ratio of 1.49 males to every one female. The admixture of age

grouping by gender reveals a powerful story for senior characters. As age increases, the percentage of female speaking

characters on screen significantly decreases. Matter of fact, females were cast in less than 30% of all roles involving char-

acters 60 years or older. This is in stark contrast to the fact that gender parity is achieved among 0 to 20 year olds across

each sample.

Given the infrequency of senior women, it was important to assess how many were completely missing across popular

programming. To this end, we conducted another invisibility analysis. The results show that 38 (52.8%) of the 72 pro-

grams were missing senior women altogether on screen. Twenty-five (50%) of the 50 most popular shows among 18 to

49 year olds did not feature one senior female during the episode coded. Among the 50 most popular shows watched by

audiences 65 years of age or older, 26 (52%) programs were completely missing senior women.

TABLE 3

SERIES REGULARS’ AGE BY SAMPLE TYPE

AGE GROUPING

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

OVERALL

0-20 YEARS

21-39 YEARS

40-59 YEARS

60 YEARS AND ABOVE

# OF CHARACTERS

13.1%

48.1%

31.7%

7%

457

5.3%

55.1%

29.8%

9.8%

399

1 0.8%

5 0.3%

30.7%

8.2%

612

Note: Among age group levels, each column sums to 100%.

TABLE 4

FEMALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

SAMPLE TYPE 40-59 60+21-390-20 TOTAL

% OF FEMALE CHARACTERS 18-49 SAMPLE

% OF FEMALE CHARACTERS 65+ SAMPLE

% OF FEMALE IN OVERALL SAMPLE

50.7%

54%

51.6%

43.9%

44.6%

43.8%

34.7%

33.7%

34.2%

29%

26.8%

27.8%

40.5%

40.1%

40.1%

Note: Each column represents the percentage of females within age grouping per sample. The percentage of males is obtained by

subtracting the percentage of females from 100%.

11

Turning to series regulars, a full 41.2% were female and 58.8% were male. This is a ratio of 1.43 males to every one female.

Looking at age and gender reveals a particularly problematic picture in popular television. Only 22% of senior series reg-

ulars were female, which recalibrates the gender ratio to 3.54 males to every 1 female. There is little deviation by sample

(>5%), as noted in Table 5.

Together, this section revealed that senior women were far more likely to be underrepresented than their senior male coun-

terparts. Further, half or more shows across the two samples failed to depict one senior female on screen in a speaking

role! The representational roadblock facing senior women becomes even more pronounced as we consider race/ethnicity,

the focus of the next section of the report.

Race/Ethnicity. Overall, a full 61.5% of speaking characters were White, 18.5% Black, 8.4% Hispanic/Latino, 4.5% Asian,

and 7.1% Mixed Race/Other (see Table 6). The overall sample of 72 unique shows did not differ from the other two samples

(18-49 year olds, 65 years and older). As such, the tables for the age-based samples are not included in the report but can

be found in the footnotes section. Combined, 38.5% of the characters across 72 popular shows were from underrepresented

racial/ethnic groups. This is on par with U.S. Census (38.7%).¹ Yet, Black characters were overrepresented on screen and

Latino characters were underrepresented (see Table 6).

Focusing on race/ethnicity by age, Table 6 reveals that characters 60 years of age and older were overwhelmingly White

(72.2%) in comparison to the percentage of White characters sample wide (61.5%) or in the 21-39 or 40-59 age groupings.

Only 1.3% of characters age 60 and above on screen were Asian.

Now, we turn our attention to incorporating gender into our intersectional analyses by race/ethnicity and age. To do so,

we first bifurcate race/ethnicity of characters in the sample into two categories: underrepresented vs. not underrepresent-

TABLE 5

FEMALE SERIES REGULARS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

% of female Series Regulars

18-49 sample

% of female Series Regulars

65+ sample

0-20

YRS OLD

21-39

YRS OLD

40-59

YRS OLD

41.4%

41.4%

41.2%

60+

YRS OLD

TOTAL

0

20

40

60%

% of females in overall sample

48.2

48.3

57.1

50

46.8

34

22

45.9

37

31.7

20.5

25

Note: Each column represents the percentage of females within age grouping per sample. The percentage of males is obtained by

subtracting the percentage of females from 100%.

12

ed. Then, we run the analyses of underrepresented character status (no, yes) by age grouping within gender. We examine

males and females separately, given the pronounced differences noted above.

Slightly more than one-quarter (27.5%) of male seniors were from underrepresented racial groups overall. This is lower

than the overall percentage of racially or ethnically diverse male characters (see Table 7). Two additional patterns are worth

noting. The largest percentage of underrepresented males in the sample was found among characters 21-39 years of age.

Surprisingly, males age 0-20 were least likely to be from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

Note: Among age group levels, each column sums to 100%. The sample includes 72 unique shows. Data from U.S. Census is retrieved

from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/.

TABLE 6

CHARACTER RACE/ETHNICITY BY AGE: OVERALL SAMPLE

21 TO 39 YRS OLD 40 TO 59 YRS OLD 60+ YRS OLD

TOTAL

0-20 YRS OLD

WHITE

BLACK / AFRICAN AMERICAN

HISPANIC / LATINO

ASIAN

OTHER

68.3

66.4 72.2

61.5

54.3

20.4

13.1

18.8

14.6

18.5

1.1

5.5

7.6

6.6

8.4

4.5

7.1

10

7.1

8.3

12

8.3 5.3

2.9

1.3

U.S. CENSUS DATA

61.3

13.3

17.8

5.7

4.1

5.7

SAMPLE TYPE 40-59 60+21-390-20 TOTAL

% OF UR CHARACTERS 18-49 SAMPLE

% OF UR CHARACTERS 65+ SAMPLE

% OF UR CHARACTERS IN OVERALL SAMPLE

23.6%

28. 2%

26.1%

38.9%

42.8%

41.9%

32.3%

32.8%

31.8%

28.9%

30.5%

27.5%

33 .8%

37%

35.3%

TABLE 7

UNDERREPRESENTED MALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

13

Overall, 28.6% of senior women were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups (see Table 8). This pattern was consis-

tent across both programs popular with viewers 18-49 and viewers 65 and older. These samples differed from each other—

senior females in TV series popular with younger viewers were more likely to be from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups

than senior females in series popular with viewers 65 and older. See Table 8. Senior women were also the least likely to be

from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group across all age groups evaluated. Half of female characters age 21-39 were

from diverse racial/ethnic groups, however.

To further understand the portrayal of senior characters, an invisibility analysis of underrepresented females aged 60 and

above was undertaken. Each show was scrutinized for the presence of any senior female speaking character from three

racial/ethnic groups: Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian. The results are presented in Table 2.

Not one program in the sample featured a senior Asian female speaking character. Hispanic/Latino female seniors were

missing from nearly all of the shows included in the sample as well (70 out of 72, 97.2%). Finally, 64 series did not feature

one Black senior female speaking character in the first episode. These findings reveal the pronounced erasure of senior

females from different racial/ethnic backgrounds in popular television programming. Despite the attention and accolades

that television receives for being more inclusive, our data shows complete failure when it comes to portraying diverse fe-

male characters aged 60 and above.

In addition to all speaking characters, the race/ethnicity of series regulars by age and gender was assessed. Here, male

and female series regulars were again analyzed separately (see Tables 9 and 10). Overall, senior series regulars were less

diverse (28.2%) than all speaking characters across 72 series (34.5%). Series regulars that were senior males (29%) were

also less likely to be from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group than the percentage of all characters in shows popular

with audiences age 65 and above (38%).

For female series regulars, a few notable sample differences emerged. Female seniors were less likely to be diverse in com-

parison to the sample wide norm of underrepresented series regular females across all 72 shows (39.3%). Only a quarter of

female senior series regulars in the 65-plus sample were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups—this was the lowest

percentage among male and female series regular seniors across both samples. In contrast, 37.5% of senior female series

regulars in the 18-49 sample were from underrepresented groups. This was the highest percentage among senior series

regular males and females.

TABLE 8

UNDERREPRESENTED FEMALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

SAMPLE TYPE 40-59 60+21-390-20 TOTAL

% OF UR CHARACTERS 18-49 SAMPLE

% OF UR CHARACTERS 65+ SAMPLE

% OF UR CHARACTERS IN OVERALL SAMPLE

40%

36.2%

36.8%

48. 2%

5 0.8%

50.6%

36.1 %

37.4%

36.9%

35.5%

26.7%

28.6%

42.7%

44.1%

43.4%

14

The analyses regarding race/ethnicity revealed that most senior speaking characters and series regulars in popular televi-

sion programming were still white and male. Very few female seniors were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups and

not one senior Asian female speaking character appeared in either sample. Clearly, whether viewers are 18 or 80, popular

content presents a problematic and skewed picture of aging.

LGBT. To examine LGBT status, the focus was on series regulars rather than all speaking characters. This was because infor-

TABLE 9

UNDERREPRESENTED MALE SERIES REGULARS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

% of UR series regulars

18-49 sample

% of UR series regulars

65+ sample

0-20

YRS OLD

21-39

YRS OLD

40-59

YRS OLD

33%

38%

34.5%

60+

YRS OLD

TOTAL

0

20

40

60%

% of UR series regulars

in overall sample

37.2

16.1

15.2

39.9

34.7

28.2

11.1

41.2

40

33.3

29

33.3

0-20

YRS OLD

21-39

YRS OLD

40-59

YRS OLD

37.6%

37.6%

39.3%

60+

YRS OLD

TOTAL

0

20

40

60%

44.3

31

16.7

45.5

47.2

28.1

27.3

30.3

27.3

26.1 25

37.5

TABLE 10

UNDERREPRESENTED FEMALE SERIES REGULARS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

% of UR series regulars

18-49 sample

% of UR series regulars

65+ sample

% of UR series regulars

in overall sample

15

mation about a character’s sexuality or gender identity might not be revealed in the first episode coded.¹ A full 48 (7.8%)

series regulars were LGBT in the sample of 72 unique shows (see Table 11). This is higher than U.S. population estimate

(3.5%) or what we typically see in cinematic content (1.1%).¹

Focusing on the overall sample of 72 shows, seniors account for 4 out of the 48 LGBT series regulars. Of these, 3 were male

(2 bisexual, 1 gay) and 1 was a transgender female. Three out of the four characters were White and 1 was Black. The lowest

number of LGBT series regulars was observed for 0 to 20 year olds. Only 2 portrayals or 3% of series regulars within this

age grouping were LGBT. Looking at the two samples of popular content in Table 12, senior LGBT series regulars do not

differ from sample wide norms.

Assessing invisibility, a full 42 episodes (58.3%) out of 72 did not depict a LGBT series regular. In total, 68 (94.4%) out of 72

shows were devoid of senior LGBT series regulars.

Taken together, senior characters in popular television programming were primarily White, straight, and male. Senior fe-

males—particularly those from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups—were rarely depicted on screen. These trends are

disconcerting, particularly as senior women outnumber senior men in the U.S.¹ The lack of representation among this seg-

ment of the television audience suggests that seniors rarely see themselves or their stories reflected on screen. In the next

section of the report, we take a look at who is calling the shots behind the camera (i.e., directors, showrunners, writers) by

gender, race/ethnicity and age—which offer insight into why these patterns may exist.

TABLE 11

LGBT SERIES REGULARS BY AGE GROUP ACROSS OVERALL SAMPLE

0-20

YRS OLD

21-39

YRS OLD

40-59

YRS OLD

60+

YRS OLD

2

4

6

8

10%

3% (2)

9.7% (30)

6.4% (12)

8% (4)

TOTAL

7.8%

(48)

SAMPLE TYPE 40-59 60+21-390-20 TOTAL

% OF LGBT CHARACTERS 18-49 SAMPLE

% OF LGBT CHARACTERS 65+ SAMPLE

3.3%

0

9.5%

5.9%

7.6%

5%

9.4%

7.7%

8.1%

5.5%

TABLE 12

LGBT SERIES REGULARS BY AGE GROUP AND SAMPLE TYPE

16

Behind the Camera. A total of 296 content creators worked behind the scenes across the 72 unique episodes coded. Of

these, 83.1% were male and 16.9% were female. A mere 8.2% were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups and 12.6%

were 60 years of age and above. As with all our analyses, only presenting the findings variable by variable fails to reveal

patterns of intersectionality. Consequently, we delineate below the age grouping and gender of key personnel working

behind the camera. Race/ethnicity of underrepresented content creators is then highlighted within these results. We only

examine content creators in the sample of 72 shows, to avoid double counting that would occur due to the overlap across

series popular with 18-49 year olds and individuals 65 years of age and older.

Focusing on directors, a total of 75 helmers (90.7% male, 9.3% female) were attached to the sample of 72 episodes. This

is a gender ratio of 9.7 male directors to every 1 female director. The age breakdown of directors by gender can be found in

Table 13. Most directors were between 40 and 69 years of age. Among male directors, 11 were underrepresented (5 Black, 3

Asian, and 3 Latino). Among female directors, 2 were diverse and both women were Black. Combining age, race/ethnici-

ty, and gender, only 5 were underrepresented directors (4 males, 1 female) age 60 or above across the 72 shows.

A full 121 writers were credited across the 72 episodes, with 78.5% men and 21.5% women (see Table 14).¹ Only two writers

worked in their 20s and both were women. A mere 6.7% of writers were underrepresented. Of the male writers (n=95), 5 were

from underrepresented backgrounds (4 Black, 1 Latino). Of the female writers (n=26), only 3 were diverse (1 Black, 1 Asian, 1

Latino). Looking across gender, race/ethnicity, and age, writers 60 years of age and above were underrepresented

across the 72 top series among 18-49 year olds and audiences 65 and above.

44

4

1 1 3 1 1

20 27 13 4

30-39

YRS OLD

40-49

YRS OLD

50-59

YRS OLD

60-69

YRS OLD

70-79

YRS OLD TOTAL

TABLE 13

DIRECTOR AGE & GENDER: OVERALL SAMPLE

68

(90.7%)

7

(9.3%)

44

0

2 6 10 7 1

16 43 31 5

95

20-29

YRS OLD

30-39

YRS OLD

40-49

YRS OLD

50-59

YRS OLD

60-69

YRS OLD TOTAL

TABLE 14

WRITER AGE & GENDER: OVERALL SAMPLE

(78.5%)

26

(21.5%)

17

Finally, we assessed demographic attributes of showrunners associated with the 72 programs. Just under a fifth were wom-

en (17%) and 83% were men, a gender ratio of 4.9 to 1. Only males were running the show in their 30s, as shown in Table

15. Focusing on showrunner race/ethnicity, only three (1 male, 2 females) were underrepresented and two were accounted

for by one creator (Shonda Rhimes; Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal). All three underrepresented showrunners were Black. No

underrepresented showrunners aged 60 and above worked behind the camera across the 72 episodes coded.

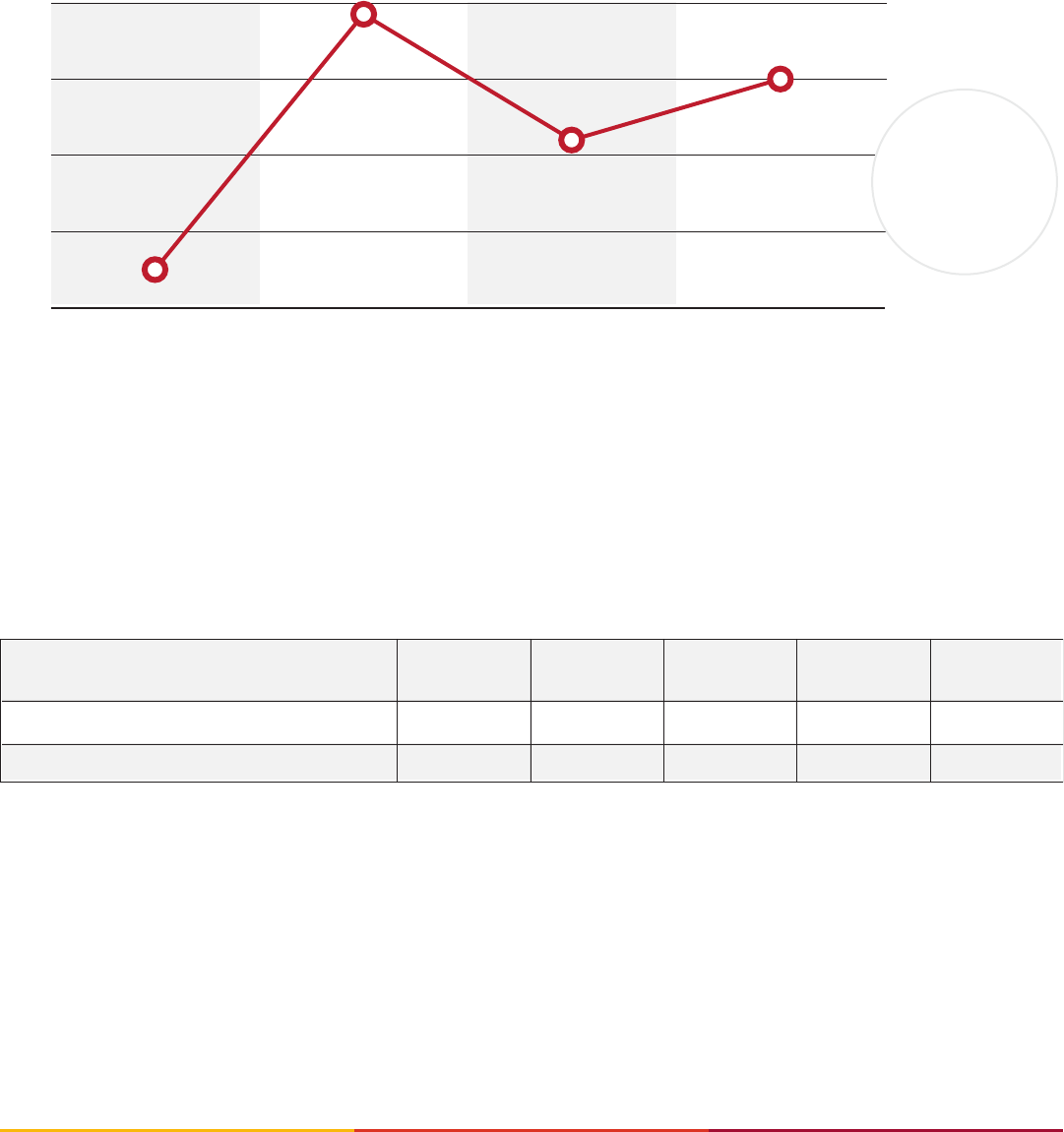

What is the relationship between content creator age and age of characters on screen in popular TV series? To answer this

question, we bifurcated the sample of directors into two age groups: those 60 years of age and older vs. those under 60.

Then, the percentage of speaking characters and series regulars by age (i.e., 60 years and above, under 60 years) was exam-

ined in these two groups. The same process was repeated for writers and showrunners.

Across 6 analyses, only one was statistically and meaning-

fully significant. As shown in Figure 1, showrunners 60 years

of age or older depicted a higher percentage of senior series

regulars on screen (+8.7%) than did showrunners under

60 years of age.¹ Because a similar trend did not emerge

when assessing the age of all speaking characters on screen

(60 and above vs. below 60 years) by showrunner age, the

results should be interpreted cautiously.

The findings on behind-the-camera personnel reveal that

few individuals age 60 and older participate in the creation

of popular television shows. Understanding the makeup of

behind the scenes teams provides an idea of why few se-

niors were depicted on screen. This is particularly the case

given that no writers or showrunners over age 60 were from

underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Perhaps diversifying

the portrayal of seniors on screen starts by employing older

writers, showrunners, and directors behind the scenes.

44

10

0 7 9 1 0

35 28 9 1

30-39

YRS OLD

40-49

YRS OLD

50-59

YRS OLD

60-69

YRS OLD

70-79

YRS OLD TOTAL

TABLE 15

SHOWRUNNER AGE & GENDER: OVERALL SAMPLE

83

(83%)

17

(17%)

FIGURE 1

SHOWRUNNER AGE BY

SERIES REGULAR AGE

% OF SENIOR

SERIES REGULAR

0

5

10

15

20

15.7%

7%

UNDER 60 YEARS60 YEARS+

18

Every senior speaking character was evaluated for the presence or absence of a job. In the qualitative analysis, this in-

cluded 154 senior characters in 72 shows, with 108 in the 18-49 sample and 114 in the sample popular with viewers 65 and

older.² Due to the overlap in senior characters across samples, results for qualitative analyses will be presented across the

72 unique series evaluated. Meaningful differences (5% or greater) between samples are noted.

Overall, 70.8% (n=109 of 154) of seniors were depicted with an occupation, which did not differ by sample (18-49=70.4%;

65+=73.7%). Females (62.8%) were less likely than males (73.9%) to be shown working across both samples. Underrepresent-

ed characters, by contrast, were slightly more likely to be employed than White characters. Nearly three-quarters (74.4%) of

underrepresented seniors held a job compared to 69.4% of White characters.

The nature of each job was assessed qualitatively for two elements. The first was the sector of employment (e.g., Politics,

Legal, Academia). The second was whether the position had clout or prestige attached to it. Clout refers to holding an

occupational post at the top of a sector. Table 17 presents the percentage of seniors with high clout across eight sectors of

employment for all 72 series included in the sample.

Male seniors (82.8%) held more high clout positions than female seniors (17.1%), with 4.83 senior males employed in pres-

tigious roles for every 1 senior female. The legal sector was the only one to depict male and female seniors nearly equally

in high clout positions. In the remaining sectors, 80% or more of the top jobs went to males. In politics, for example, the

only high clout position for a senior female was a royal figure in Game of Thrones. In contrast, males served in roles such as

President, Secretary of State, and member of Congress. One additional male character served as a royal/ruler. Thus, senior

female characters were absent from attainable and prestigious political positions across 72 of the most popular series on

television among adults age 18-49 and viewers age 65 and older.

These disparities carry into other sectors as well. To illustrate, male seniors held positions as doctors while the lone senior

female with high clout in the medical field was a hospital administrator. In law enforcement, senior males worked as police

and fire chiefs, a police commissioner, and a top general. The senior female with high clout in this sector served as CIA Di-

#2

Note: Each column sums to 100%. The sample includes episodes from 72 unique shows.

MEASURE

TOTAL

WHITE

UNDER

REPRESENTED

FEMALESMALES OVERALL

% WITH A JOB

% WITHOUT A JOB

73.9%

26.1%

111

62.8%

37.2%

43

69.4%

30.6%

111

74.4%

25.6%

43

70.8%

29.2%

154

TABLE

OCCUPATIONAL STATUS OF SENIOR CHARACTERS BY GENDER ACROSS TWO SAMPLES

19

rector. Despite this, the contributions of female seniors across industries were rarely seen at the top of various industries.

In terms of race/ethnicity of seniors with top jobs, nearly one-third (31.4%, n=11 of 35) of high-status occupational roles

were held by characters from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Notably, four underrepresented senior females held

prestigious positions. This represents two-thirds of all employed senior females with high clout. These women (3 Black/Af-

rican American, 1 Latina) included two judges, a hospital administrator, and one CIA director. The seven underrepresented

senior males worked as a Chief Justice, a high-ranking government secretary, doctors, a police chief, and the owner of an

oil company.

While the majority of senior characters on television had jobs, few were working in positions with power or prestige. The

individuals inhabiting these roles were predominantly male. Notably, there was racial/ethnic diversity among those seniors

holding high status jobs. Additionally, while there were few women with occupational prominence, the majority of female

seniors with clout were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Next, we turn toward the occupational context in

which senior characters worked.

The following analyses, as well as others later in the report, focus on “main” senior characters. As noted earlier, main char-

acters included only leading or supporting senior characters in the episode evaluated as well as senior series regulars. A

total of 70 senior characters appeared in the full 72 programs examined. This included 45 main characters in the 50 series

popular with viewers 18-49 and 56 main characters in the 50 series popular with viewers 65 and older.

Of the main senior characters across all 72 series, 80% (n=56) had a job and 20% (n=14) did not. This differed by sample.

Main senior characters were more likely to be employed in the sample of content popular with viewers 65 and older (83.9%,

n=47) than in the sample popular with viewers 18-49 (73.3%, n=33).

For those main senior characters with a job, mentions of expertise related to occupation were assessed. These statements

referred to a character’s knowledge, skill, or status. Few main senior characters (16.1%; n=9 of 56) were referenced as be-

Note: Within sector, each row sums to 100%. The sample includes 72 unique shows. Sectors with four or fewer characters were col-

lapsed to form the “Other” category.

MEASURE

TOTAL 82.8% (n=29) 17.1% (n=6)

FEMALESMALES

88.8% (n=8)

60% (n=3)

85.7% (n=6)

83.3% (n=5)

87.5% (n=7)

11.1% (n=1)

40% (n=2)

14.3% (n=1)

16.7% (n=1)

12.5% (n=1)

% IN POLITICS (E.G., PRESIDENT, MEMBER OF CONGRESS)

% IN LAW (E.G., CHIEF JUSTICES, CITY ATTORNEY)

% IN LAW ENFORCEMENT (E.G., CHIEF OF CIA, MILITARY OFFICER)

% IN HEALTHCARE (E.G., SURGEON, PHYSICIAN)

% IN OTHER (E.G., RELIGION, ACADEMIA, HOUSING, ENERGY)

TABLE 17

OCCUPATIONAL CLOUT OF EMPLOYED SENIOR CHARACTERS BY GENDER

20

ing experts across all 72 series. Only 1 female main senior character was coded with expertise, as she was called a “skilled

psychiatrist.” This same senior woman had high clout in the previous analysis. Additionally, the occupational prowess of one

Black male and one Latino male character was mentioned.

The workplace relationships of senior main characters were also examined. Here, the goal was to determine if relationships

between seniors and their colleagues were supportive, strained, or some combination of the two. A final category was used

when not enough information was provided within the plot to discern the nature of seniors’ relationships.

As shown in Table 18, employed main senior characters were primarily in supportive relationships. Seniors in series popular

with viewers age 65 and older were more likely to be in supportive relationships than characters in series popular with view-

ers age 18-49. This contrasts with supportive and strained relationships, which were more likely to occur in series popular

with viewers 18-49 than viewers 65 and older. Male characters (46.5%) were more likely than female characters (30.8%) to

be depicted in supportive collegial relationships.

The occupational profile of seniors in television contrasts with the real-world working life of older Americans. A full 70.2%

of U.S. seniors are not part of the labor force,²¹ but in television programming, seniors were overwhelmingly shown at work.

This may be due to the nature of televised storytelling, which often focuses on the workplace (i.e., a hospital, legal office,

police force). Along with the predominantly supportive relationships of seniors in occupational settings, these storylines

may offer a counter stereotypical view of seniors, particularly to younger audiences.

Managing health needs is a key component of aging. For example, 80% of adults 85 and older have, at minimum, one

chronic health condition.²² Additionally, one-third of Americans 65 years of age and older have one or more limitations on

activities of daily living.²³ As such, it was important to understand whether television programming captured health chal-

lenges of senior characters. Across both samples of content, all speaking characters age 60 and above were evaluated for

the presence of health issues.

#3

TABLE 18

RELATIONSHIPS OF EMPLOYED MAIN SENIOR CHARACTERS BY SAMPLE TYPE

RELATIONSHIP TYPE

TOTAL EMPLOYED SENIORS 33 47 56

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

TOTAL SERIES

SUPPORTIVE

STRAINED

SUPPORTIVE AND STRAINED

CAN’T TELL

36.4% (n=12)

15.2% (n=5)

21.2% (n=7)

27.3% (n=9)

46.8% (n=22)

14.9% (n=7)

10.6% (n=5)

27.2% (n=13)

42.9% (n=24)

10.7% (n=6)

17.9% (n=10)

28.6% (n=16)

21

A total of 7.8% (n=12 of 154) of senior characters had a health issue across the 72 series evaluated. There were no differ-

ences by sample as 8.3% (n=9) of seniors experienced health problems in shows popular with viewers 18-49 as did 7%

(n=8) of seniors in programs popular with viewers 65 and older. All 12 of the characters who experienced a health issue

were male. One-quarter (n=3) of seniors with a health issue were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

The nature of health issues was assessed. Five seniors were in recovery from accidents or injuries, 4 were living with physi-

cal, mental, or communicative impairments (i.e., mobility, mental health), 2 had a physical illness (i.e., cancer), and 1 had

a non-specific health issue.

The use of assistive devices among characters age 60 and older was also assessed. Here, assistive devices referred to both

mobility aids and prescription drugs. Very few seniors used assistive devices (3.2%, n=5 of 156) across all 72 series evaluat-

ed. Given that 25% of adults age 65 and above in the U.S. use a mobility aid,² and in one survey, 90% of seniors reported

taking one or more prescription drugs in the past 30 days,² television appears to vastly underrepresent the health chal-

lenges and needs of real-world seniors.

Aside from health, death of senior characters was assessed. This was to determine if content featuring seniors focused on end

of life. Few senior characters died across the samples of content. Just 5.8% (n=9) of senior characters perished in the 72 pro-

grams sampled—which is lower than the percentage of seniors who died in popular film (10.7%).² One potential explanation

for the difference between film and television is TV’s reliance on serial storytelling. When a TV character dies, it concludes his/

her storyline and cuts off other potential avenues to explore. Practically, actors may have contracts that need to be honored

across a season. Thus, films may be more likely to include senior death as a plot point or story feature than television.

There were no differences by sample in the prevalence of senior death. All of the senior characters who died were male,

and 33.3% or 3 were from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group. Every senior death was due to violence. This included

three individuals who were shot, two who were stabbed, and four others who were killed while fighting, attacked by a bear,

hanged, or the victim of an explosion.

While Americans continue to cope with the costs of aging and health care, television represents seniors as predominantly

healthy. Few seniors across the samples of content experienced any health problems or relied on assistive devices. While

the leading causes of the death for U.S. seniors are heart disease, cancer, and chronic respiratory ailments,² on television

the few seniors that die fell prey to violence. These depictions may contribute to seniors’ safety concerns or perceptions of

HEALTH ISSUE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

TOTAL

SERIES

PHYSICAL, MENTAL, COMMUNICATIVE IMPAIRMENT

PHYSICAL ILLNESS

RECOVERY

NON-SPECIFIC HEALTH ISSUE

44.4% (n=4)

22.2% (n=2)

22.2% (n=2)

11.1% (n=1)

12.5% (n=1)

12.5% (n=1)

62.5%(n=5)

12.5% (n=1)

33.3% (n=4)

16.7% (n=2)

41.7% (n=5)

8.3% (n=1)

TOTAL SENIOR CHARACTERS WITH HEALTH ISSUES 9 8 12

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS & ABOVE

TABLE 19

HEALTH ISSUES OF SENIOR CHARACTERS BY SAMPLE TYPE

22

the real world as a violent or dangerous place.² Also, this incongruity between fiction and reality suggests yet another way

that entertainment masks the day to day concerns facing many seniors.

The nature of familial relationships was assessed for main senior characters. Here, the focus was on the relationships

characters held with family members during the time they were 60 years of age or older. Thus, flashbacks to an earlier time

were not included in this measure. Current spouses or long-term romantic partners were included as family members.²

Once it was determined that characters had family relationships, these connections were coded as supportive, strained,

supportive and strained, or can’t tell (for cases where not enough information was provided).

Of the 70 main senior characters in the sample of 72 series, 44.3% (n=31) had family relationships and 51.4% (n=36)

lacked these ties. This did not differ by sample. Females were more likely than males to have family relationships. Over half

(55.6%, n=10 of 18) of senior females had families while 40.3% (n=21 of 52) of males did. Few of the seniors from underrep-

resented racial/ethnic groups (23.5%, n=4 of 17) had family relationships, versus half of White seniors (50.9%, n=27 of 53).

For the most part, familial relationships were supportive in nature. The majority (64.5%, n=20) of senior characters in the

72 series evaluated had supportive relationships with family, while 32.3% (n=10) were both supportive and strained, and 1

(3.2%) constituted a strained relationship. See Table 20. This did not differ by sample.

Senior characters’ familial ties were further examined to determine whether the character was a grandparent. For this mea-

sure, the entire sample of senior characters (n=154) was evaluated across all 72 shows. The results are presented in Table

21. A total of 24 (15.6%) seniors were grandparents while 84.4% (n=130) were not. These trends are surprising, as 83% of

Americans in the 65-plus age bracket claim status as a grandparent, while 52% of individuals age 50-64 are grandparents.³

Clearly, television does not mirror reality when it comes to showcasing this particular familial relationship.

Examining the demographics of grandparents reveals that most of these relationships were held by White males. Of se-

nior grandparents, 29.2% (n=7) were female, and 70.8% were male. One-third of senior grandparents (33.3%, n=8) were

#4

RELATIONSHIP TYPE

TOTAL SENIORS WITH FAMILY 19 25 31

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

TOTAL SERIES

SUPPORTIVE

STRAINED

SUPPORTIVE AND STRAINED

63.2% (n=12)

5.3% (n=1)

31.6% (n=6)

64% (n=16)

4% (n=1)

32% (n=8)

64.5% (n=20)

3.2% (n=1)

32.3% (n=10)

TABLE 20

FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS OF SENIOR CHARACTERS BY SAMPLE TYPE

23

from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. More senior grandparents were female in the sample of content popular with

18-49-year-olds (33.3%, n=6) than in the sample of programming popular with viewers age 65 and older (20%, n=3).

The nature of grandparent relationships was assessed for main senior characters only. Of the 15 senior characters who were

grandparents in the 72-show sample, 86.7% (n=13) had a discernible relationship with their grandchildren while 1 senior

did not. For the final individual, the presence of a relationship could not be determined (8.3%, n=1). Two-thirds of these

grandparent (66.7%, n=10) characters enjoyed supportive relationships with their grandchildren while the nature of the

remaining one-third of relationships could not be ascertained. In terms of demographics, three of these senior characters

with supportive relationships were female, and three were Black/African American.

Family relationships fill important roles in the life of seniors. Family members may provide support as caregivers or fulfill

emotional needs related to connectedness. Research suggests that close relationships with family members may even be

related to mortality.³¹ Despite the value of close family bonds, in television, less than half of main senior characters were

depicted with family relationships. For those that did have familial ties, however, these were predominantly supportive

relationships. These findings suggest that television content may offer a window into positive family interactions involving

seniors—even if they are few in number.

The media and technology use of seniors was evaluated. For each main senior character, a series of measures assessed

whether time was spent with media. Media use included watching television or movies or reading books or newspapers.

Additionally, two categories of media were assessed specifically: consuming news (televised or via newspaper) or watching

television programming. Technology use was also examined. Characters who interacted with devices such as computers,

cell phones, or tablets were considered to be using technology. Specific categories of interest included use of a cellphone

or use of any type of computer.

Looking first at media consumption, 20% of main senior characters used any form of media while 80% did not. See Table

22. This differed by sample, as 13.3% (n=6) of seniors in the sample popular with 18-49 year old viewers used media while

19.6% (n=11) of seniors in the sample popular with viewers age 65 and above interfaced with media. There were no mean-

TOTAL SENIORS 108 114 154

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

TOTAL SERIES

GRANDPARENT

NOT A GRANDPARENT

16.7% (n=18)

83.3% (n=90)

13.2% (n=15)

86.8% (n=99)

15.6% (n=24)

84.4% (n=130)

TABLE 21

SENIOR CHARACTERS PORTRAYED AS GRANDPARENTS BY SAMPLE TYPE

#5

24

ingful differences by sex or race/ethnicity in media use. Females (16.7%, n=3 of 18) were less likely to utilize media than

males (21.2%, n=11 of 52). This was also true for individuals from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups (17.6%, n=3 of 17)

compared to White characters (20.8%, n=11 of 53).

The type of media used by main senior characters was also analyzed. Half (n=7) of seniors using media read or watched

news content, and 57.1% (n=8) watched television. As characters could both consume news and television, these percent-

ages do not add to 100%.

Turning to technology engagement, nearly half (47.1%, n=33) of main senior characters across all 72 series used some form

of technology. As shown in Table 23, seniors in the sample of content popular with viewers 65 and older (50%) were more

likely to utilize technology than seniors in the series popular with viewers age 18-49 (35.6%). Differences emerged in tech-

nology use by sex and race/ethnicity. One-third of female seniors (33.3%, n=6 of 18) were shown with technology versus

half of male seniors (51.9%, n=27 of 52). This was similar to the percentage of seniors from underrepresented racial/ethnic

groups (35.3%, n=6 of 17) compared to White seniors (50.9%, n=27 of 53).

Of the senior characters that operated technology, 72.7% (n=24) did so with a cell phone. Over one-third (39.4%, n=13)

worked with a computer or similar device during the program. These percentages do not add to 100%, as it was possible

for seniors to use a cell phone and a computer.

Although half of senior characters used technology, television portrayals contrast sharply with seniors’ actual engagement

with entertainment or computing. Nielsen estimates that 82% of the Baby Boomer generation (age 53-70) have a computer

TOTAL SENIORS 45 56 70

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

OVERALL SERIES

MEDIA USE OVERALL

NO MEDIA USE

13.3% (n=6)

86.7% (n=39)

19.6% (n=11)

80.4% (n=45)

20% (n=14)

80% (n=56)

TABLE 22

MAIN SENIOR CHARACTERS’ MEDIA USE BY SAMPLE TYPE

Note: Within sample, each column sums to 100%. Media use consisted of viewing television and/or reading. Only main senior charac-

ters were evaluated for this measure.

TOTAL SENIORS 45 56 70

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

OVERALL SERIES

TECHNOLOGY USE OVERALL

NO TECHNOLOGY USE

35.6% (n=16)

64.4% (n=29)

50% (n=28)

50% (n=28)

47.1% (n=33)

52.9% (n=37)

TABLE 23

MAIN SENIOR CHARACTERS’ TECHNOLOGY USE BY SAMPLE TYPE

Note: Within sample, each column sums to 100%. Technology use included interacting with devices such as cell phones, computers,

and/or tablets. Only main senior characters were evaluated for this measure.

25

in the home, and that 86% of Boomer households have smartphones. These individuals spend considerable time with tech-

nology—roughly more than 4 hours per day across traditional computing, smartphones, or tablets.³² This generation also

spends over 6 and a half hours per day watching television,³³ and individuals 50 and older hold the largest share of news

consumption.³ Clearly, seniors are engaged with the world around them through technology and entertainment—but this

was rarely captured in popular TV programs.

The language used by and about senior characters was analyzed for the presence of ageism. Nonverbal or verbal references

to aging or other negative traits related to the aging process were catalogued. Only the series with main senior characters

were assessed for the presence of ageist comments.

A total of 39 series across all 72 evaluated featured main senior characters. Of those series, 41% (n=16 of 39) had one or

more ageist comments (see Table 24). The presence of ageist comments varied by sample. Half of shows popular with view-

ers age 18-49 featured at least one ageist comment, while slightly more than one-third of shows popular with viewers age

65 and older did.

The genre of each series was incorporated into the analysis. Across all 16 series with an ageist comment, half of the pro-

grams were dramas and half were comedy or animated series (i.e., The Simpsons). Additionally, the origin of ageist com-

ments was identified as either from the senior character or from another character. A full 68.8% (n=11) of series contained

self-originated comments and 62.5% (n=10) of series contained comments that came from others. As more than one com-

ment could occur per show, these do not sum to 100%.

Ageist comments were sorted into descriptive categories. The largest category was comments that reference age in a gen-

eral or non-specific manner. Thirteen or 81.3% of series with ageist comments across the full sample fit into this category.

Examples of comments in this category include: “Your parents are old. Anything unspeakable was finished by 9:30,” “Things

just sound creepier when you’re old,” “You like the color? It’s called ‘ancient ivory,’ like you,” or referring to a character as

“Caveman.”

TOTAL SERIES EVALUATED 26 30 39

POPULAR SHOWS

65 YRS AND ABOVE

POPULAR SHOWS

18-49 YR OLDS

TOTAL SERIES

AGEIST COMMENT PRESENT

AGEIST COMMENT ABSENT

50% (n=13)

50% (n=13)

36.7% (n=11)

63.3% (n=19)

41% (n=16)

59% (n=23)

TABLE 24

AGEIST COMMENTS BY SAMPLE TYPE

Note: Only series featuring main senior characters were evaluated for the presence of ageist comments. A total of 39 series of the 72

evaluated included main senior characters.

#6

26

The second category related to physical and mental well-being. Here, 50% (n=8) of series with ageist comments referenced

senior characters’ health or abilities. This category included comments such as: “I need to write down all these precious mo-

ments before I forget them,” or “We’re elderly, so, uh, you know, we’ll just sit here and suffer.”

A handful of other comments related to appearance and traditionality. Just (12.5%, n=2) of series with ageist comments

mentioned these aspects of aging. One example of this was referring to a character as a “wrinkled old bastard.” Finally, 3

series (18.8%) contained ageist comments related to death.

To understand the origins of ageist comments, the presence of a writer or showrunner who was 60 years of age or older on

each program with a main senior character was catalogued. Shows without a 60-plus writer were more likely to feature an

ageist comment than shows with senior writers. A full 81.2% (n=13) of series with ageist comments were written by a writer

younger than 60, while 18.8% (n=3) of series with an ageist comment had a senior writer. The same held true for showrun-

ners. Three-quarters (n=12) of series with ageist comments had showrunners younger than age 60. The remaining 25% of

series with ageist comments had showrunners age 60 or older. This analysis suggests that ageist comments stem from

the work of younger writers and showrunners.

The findings mirror the percentage of ageist comments found across popular films from 2015 (52.6%) and Academy

Award-nominated movies (42.9%). It is notable that series popular with a younger demographic contain a greater percent-

age of ageist comments than series popular with older viewers. The results also demonstrate that ageism was part of the

fabric of dialogue when it comes to storytelling featuring senior characters. Invoking stereotypes about age could have neg-

ative consequences for viewers. Research has demonstrated that implicit ageism is related to adverse health and cognition

outcomes for seniors.³ If writers and audiences understood the potential costs of ageist comments for older viewers, this

content might not seem so humorous.

27

T

he purpose of the present investigation was to assess the prevalence and portrayal of senior characters in two

samples of television content. A total of 50 series popular with 18-49 year old viewers and 50 series popular with

viewers 65 and older were examined. Four major findings emerged across the 72 TV programs evaluated.

Seniors are Snubbed in Popular Television Programs

Senior characters filled fewer than 10% of all speaking roles in popular television series. Meanwhile, seniors represent

almost one-fifth of the U.S. population, and this constituency continues to increase.³ Further, the demographic represen-

tation of fictional characters bears little resemblance to the diversity of real-world seniors. Less than 30% of senior char-

acters and close to one-quarter of series regulars in popular television series were female, although over half of individuals

age 60 and above in the U.S. are women. This disparity was more pronounced for women of color. Not one senior Asian fe-

male was depicted across the television shows studied, while Black/African American and Latina seniors appeared in only a

handful of programs. Shows that included LGBT seniors were rare, with only one transgender senior female in all 72 shows.

The lack of seniors in popular television programming mirrors previous studies on top-grossing film and Academy

Award-nominated content. The exclusion of individuals from this group across entertainment is more than a failure to

depict a significant demographic. Seniors are also a powerful audience. Baby Boomers’ household spending clocks in at

roughly $60,000 per year, which is greater than Millennials (around $47,000). Even individuals in the Silent generation

(born 1929 to 1945) spend over $40,000 per year.³ Most importantly, these groups are still tuning in to television. Neglect-

ing to include senior characters is a decision to alienate the senior audience, and one that may not be prudent for networks

courting advertisers in an increasingly fragmented television landscape.

Senior Characters Spring from the Imaginations of Younger Creators

A limited number of individuals age 60 and older worked behind the camera across the 72 series evaluated—just 12.6% of

all credited directors, writers, and showrunners. Moreover, of the individuals age 60 or above working behind the scenes,

females or individuals from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups appeared infrequently. Only 1 senior female writer and

1 senior female showrunner worked across the sample. None of the 60-plus writers or showrunners were from underrepre-

sented racial/ethnic groups.

The only significant association between the age of individuals working behind the camera and the presence of seniors on

screen occurred between series regulars and senior showrunners. However, the lack of older writers—particularly women

and those from underrepresented groups—suggests that creative individuals working behind the scenes may be important

to ensure that the stories of older characters are told. The lack of inclusion behind the scenes in Hollywood is well-docu-

mented by our other studies.³ It is clear that gender and race/ethnicity are not the only demographics that restrict oppor-

tunity—age may be another factor that limits the careers of content creators.

Seniors are Still Shown in the Workforce in Popular Television Programs

While most individuals 60 and older in the U.S. have left the workforce, popular TV programs paint a portrait of an active,

engaged and working senior contingent. Nearly three-quarters of senior characters were shown with a job, and 21% of em-

ployed seniors were in high clout positions. Female seniors, however, were less likely to be shown working, and less likely

than their male counterparts to have prestigious occupations. One bright spot, however, was the prevalence of employed

28

senior characters from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups and the depiction of women of color in high-status jobs.

The portrayal of seniors across other qualitative measures reflects the focus on seniors’ capability for work. The majority of

seniors were healthy and few died—none of whom perished due to a health issue. Additionally, nearly half of main senior

characters were shown using technology. For younger viewers—especially those who expect to work longer before retire-

ment—television may demonstrate the value of the senior workforce. For older viewers, these portrayals may reinforce that

seniors can still make important contributions to society no matter their age.

Seniors Confront Ageist Comments in Popular Television Programs

The language used to refer to senior characters in television continues to reflect stereotypes about aging. Forty-one percent

of shows featuring a main senior character contained at least one ageist comment. This is on par with previous findings

across cinematic storytelling,³ and reflects a reliance on outdated tropes by writers and storytellers. In fact, the individuals

peppering shows with ageist commentary tended not to be seniors—suggesting that stereotypes or beliefs held by younger

industry members may perpetuate misrepresentation or outdated views of older characters. While ageism may seem funny,

it can have potential negative effects. These include performance on memory tasks, handwriting, physiological indicators,

and even seniors’ will to live. Reinforcing negative conceptions about aging among younger viewers may also strengthen

stereotypes and result in stronger implicit associations about aging.

While the findings in this investigation provide important insights into the depiction of seniors in television, a few limita-

tions must be noted. First, only one episode of each series was evaluated. All speaking characters and series regulars were

examined, which provided an understanding of the overall diversity across a show as well as the individuals with a recurring

role who may be more familiar to audiences. However, this approach may mean that minor parts featuring seniors in later

episodes were missed. This extends to behind the camera data. Seniors may be employed as writers or directors on other

episodes throughout the season. Future studies may wish to extend these findings by looking at employment on screen and

behind the scenes across multiple episodes.

Second, our measures of popularity may exclude other pertinent portrayals of seniors. Importantly, streaming content was

not analyzed in this study. As many adults view content on platforms such as Netflix or Amazon, additional programs not

included in this evaluation may or may not include more diverse senior representation. Additionally, less popular programs

may feature more seniors, or they may be less likely to include individuals from this age group. Researchers may wish to

review series beyond the 72 included in this report to gain a fuller picture of the television landscape.

Finally, ageist comments were only assessed for main senior characters. It is possible that looking at the dialogue surround-

ing minor senior characters or all characters in general could reveal different findings. In particular, it would be informative

to examine portrayals of middle aged characters to understand how views of aging are conveyed through dialogue between

slightly younger individuals.

Overall, this study extends our understanding of how seniors were depicted in popular media content. It is clear that tele-

vision was similar to cinematic content in its exclusion of older individuals—both in front of and behind the camera. As a

sizeable and significant portion of the population, seniors have a wealth of stories to share and perspectives to present.

Incorporating characters and storytellers in their later years will give viewers of all ages the opportunity to watch more

vibrant, diverse, and compelling stories on screens both large and small.

29

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our thanks to Humana for their support of this project, especially, Jody Bilney, Jennifer Bazante, Tom Noland, Dr. Roy

Beveridge, and Dr. Yolangel Hernandez Suarez. Special thanks also go to our partners at Golin for their work in support

of this research. Our appreciation also goes to PHD Media, especially James Rubino and Nicole Briggs, for their help with

the sample. We are also thankful for our incredible partners at the USC Annenberg Center for Public Relations, Fred Cook

and Tina Vennegard. Our colleagues at USC and USC Annenberg are fantastic and we are grateful to work with them,

including Dean Willow Bay, Patricia Lapadula, Gretchen Parker McCartney, Evan Weisman, Calvin Cao, and Dr. Sarah

Banet-Weiser.

The Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative has amazing partners who are the force behind our work, including The

Annenberg Foundation, Ruth Ann Harnisch, Jacquelyn and Gregory Zehner, Barbara Bridges, Ann Lovell, Suzanne Lerner,

Mari and Manuel Alba, Julie Parker Benello, Bonnie Arnold, and Ann Erickson. We would also like to express our thanks

to Leah Fischman for her strategic guidance on our MDSC activities. Finally, our student researchers make all of this work

possible. They are the heartbeat of the lab, and we are immensely thankful for their work!

MDSC INITIATIVE STUDENT RESEARCH TEAM

Alexandra Aftalion

Lauren Bickford

Victor Blackwell Jr.

Alison Brett

Gabriella Cantrell

Celine Carrasco

Mahan Chitgari

Christine Choi

Samantha Cioppa

Hannah De Alicante

Audrey Deighan

Isabel Fitter

Lance Good

Megan Jackson

Suzanna Keough

Dorga Kim

Madeline Kim

Yoojin Andie Lee

Abagail Levinson

Lorraine Lin

Eric Loeb

Xiaoyue Evelyn Lu

Edward Lau

Catriona McIlwraith

Sarah Neff

Mia Nguyen

Alison Omon

Teresa Pham

Shirlene (Emma) Pierre

Caitlin Plummer

Zach Rowe

Erin Seo

Diana Silvestri

Natalie Skinner

Jenny Truong

Nandeeta Vaswani

Sylvia Villanueva

Sarah Voss

Emma Vranich

Chasen Washington

Rachael Woods

Mengran Xia

Melissa Yau

Praisella Yosep

30

1. U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.). Age Groups and Sex: 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

Available: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_5YR_S0101&prodType=table

2. The Macarthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society (2009). Facts and Fictions about an Aging America. Contexts, 8(4), 16-21.

3. The Nielsen Company (2017). The Nielsen Total Audience Report Q1 2017.

4. Smith, S.L., Pieper, K., & Choueiti, M. (2016). The Rare & Ridiculed: Senior Citizens in the 100 Top Films of 2015. Report prepared for Humana. Media, Diversi-