The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

1

OVERVIEW

The Evolution of Deep

Trade Agreements

A. Mattoo, N. Rocha, and M. Ruta

1

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

2

OVERVIEW

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

A. Mattoo*, N. Rocha* and M. Ruta*

* World Bank, Washington, DC, United States

CONTENTS

O.1. INTRODUCTION 3

O.2. SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY 6

O.3. STYLIZED FACTS 12

O.4. THE CHALLENGE OF QUANTIFYING THE EFFECTS OF DTAs 19

O.4.1 Directly constructed indices 19

O.4.2 Indirectly estimated measures 20

O.4.3 Quantication challenges: some analytical issues going forward 22

O.5. CONCLUSIONS 23

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 24

REFERENCES 25

ANNEX 26

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

3

O.1. INTRODUCTION

This Handbook provides new data on and analysis of all preferential trade agreements

(PTAs) that have been notied to the World Trade Organization (WTO), and highlights the

emergence of deep trade agreement (DTA).

1

DTAs are reciprocal agreements between countries that cover not just trade but additional policy

areas, such as international ows of investment and labor, and the protection of intellectual property

rights and the environment, amongst others. While these legal arrangements are still referred

to as trade agreements, their goal is integration beyond trade or deep integration. DTAs aim at

establishing ve “economic integration” rights: free (or freer) movement of goods, services, capital,

people, and ideas. DTAs also include enforcement provisions that limit the discretion of importing

governments in these areas, as well as provisions that regulate the behavior of exporters.

Preferential trade agreements have always been a feature of the world trading system but

have become more prominent in recent years. The number of PTAs increased from 50 in the

early 1990s to roughly 300 in 2019. All WTO members are currently party to one, and often

several, PTAs. While WTO rules still form the basis of most trade agreements, PTAs have

in some sense run away with the trade agenda. Traditional trade policy areas, such as tari

reduction or services liberalization, are now more frequently negotiated in regional contexts

rather than at the WTO, with PTAs often going beyond what countries have committed to

at the WTO. The result is that PTAs have expanded their scope. While the average PTA in

the 1950s covered 8 policy areas, in recent years they have averaged 17. In other words, there

is some preliminary evidence that PTAs are becoming DTAs, both on the intensive margin

(specic commitments within a policy area) and the extensive margin (number of policy areas

covered). In this Handbook, we do not draw a sharp distinction between DTAs and other

PTAs. Rather, the aim is to demonstrate the progressive deepening of PTAs.

Deep trade agreements matter for economic development. The rules embedded in DTAs,

along with the multilateral trade rules and other elements of international economics law

such as international investment agreements, inuence how countries (and, hence, the people

and rms that live and operate within them) transact, invest, work, and, ultimately, develop.

1

In the international economics and law literature, “PTA” is an umbrella term encompassing several types of

reciprocal agreements between trading partners: regional trade agreements (RTAs), free trade agreements (FTAs),

and customs unions (CUs). This denition diers from that of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which

denes PTAs as agreements that grant unilateral (i.e., non-reciprocal) trade preferences such as the Generalized

System of Preferences schemes, under which developed countries grant preferential taris to imports from

developing countries.

This study, following the denition from international economics and law, uses the term “PTA” to refer to

all types of trade agreements, both within and across regions, and uses “DTA” to refer to PTAs that contain

provisions aimed at deepening economic integration between trading partners.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

4

Trade and investment regimes determine the extent of economic integration, competition

rules aect economic eciency, intellectual property rights matter for innovation, and

environmental and labor rules contribute to social and environmental outcomes.

It is, therefore, vital that rules and commitments in DTAs be informed by evidence and

shaped more by development priorities than by international power dynamics or domestic

politics. An impediment to this goal is that data and analysis on trade agreements have not

captured the new dimensions of integration, which makes it dicult to identify the content

and consequences of DTAs.

This Handbook takes a rst step towards lling this important gap in our understanding of

international economic law and policy. It presents detailed data on the content of the eighteen

policy areas most frequently covered in PTAs, focusing on the stated objectives, substantive

commitments, and other aspects such as transparency, procedures, and enforcement. In terms

of the coverage of policy areas and the granularity of information within each area, this is the

most comprehensive eort to date. Each chapter, authored by a leading expert in his or her

eld, explains in detail the methodology used to collect the information and provides a rst

look at the evidence in each policy area.

The new data and analysis will inform experts and policymakers in their eorts to design, negotiate,

and take advantage of DTAs that promote development. This information will also enable

researchers to develop indicators on the depth of trade agreements in dierent policy areas, assess

the similarities between these arrangements, and benchmark countries’ DTAs relative to their

partners. It will also help identify the rules that benet only participants and those that have large

spillover eects on non-participants or excluded countries. Finally, the new data and analysis in this

study will allow researchers to identify areas where there is de facto convergence across dierent

players, thus facilitating the adoption of commonly agreed multilateral rules.

This Handbook will lay the groundwork for new research in international economics

and other elds. A large body of economic literature has looked at the eects of PTAs

on international trade ows and on welfare.

2

However, this literature has two important

limitations.

3

On the theoretical side, the study of PTAs is mostly based on Vinerian

4

logic,

which focuses exclusively on taris, thus by construction excluding deep integration issues.

On the empirical side, attempts to quantify the eects of PTAs suer from a measurement

error problem, as studies generally rely on dummies to identify trade agreements or distinguish

between broad categories of agreements such as FTAs or CUs. The new data will help

theorists to model DTAs and help empirical economists to properly identify their eects.

2

See, e.g., Freund and Ornelas 2010, Limao 2017.

3

See, e.g., Baldwin 2010, Mattoo et al. 2017.

4

Viner 1950.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

5

Beyond economics, the data will inform research in other elds, primarily international law

and international relations, on important issues such as the commonality or divergence of the

rules set in PTAs and how they could evolve in the future.

The research in this Handbook is the result of collaboration among the World Bank, the

International Trade Centre (ITC), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD), the WTO, and experts from academic institutions. It builds on previous

research by the World Bank and others. A rst database on the content of deep trade agreements

was published in 2017 with the goal of documenting how the policy areas covered by PTAs

had increased over time (Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta 2017). This dataset allowed researchers

to construct a rst series of indicators which capture the scope of trade agreements; i.e., what

policy areas they cover. We refer to this as the extensive margin of PTA depth. Based on this rst

dataset, several research papers then looked, respectively, at the impact of deep trade agreements

on trade, global value chains, and foreign direct investment (FDI), and the eect of breaking

up such agreements.

5

The data have also been extensively employed for policy advice by the

Wo rl d B an k i n s eve ra l d eve lo pi ng c o u n t r i es i n Af r i c a , L a ti n A me r i c a , E a st As ia , a n d t h e B a l k a n s .

The new data that we briey review in this introduction and that are analyzed in detail

in the individual chapters of this Handbook oer insights into a dierent dimension of

PTAs’ depth. They capture the detailed commitments to establish and preserve the rights to

economic integration, and the procedures, institutions, and enforcement mechanisms that

countries set up to make deep integration work. The focus is therefore not on the extensive

margin of integration (number of policy areas that are covered by the agreement), but on its

intensive margin (the specic commitments within a policy area).

While there are a number of individual studies that have documented the deepening of PTAs

in specic areas, two major data collection projects—Dür, Baccini, and Elsig (2014) and Acharya

(2016)—also aimed at documenting the specic commitments for a group of policy areas covered

in PTAs. Both eorts have important merits. Dür, Baccini, and Elsig (2014) covered a large set of

PTAs, including those that have been notied to the WTO but are no longer in force. Acharya

(2016) provided a series of databases on the content of PTAs that go beyond specic policy areas

and cover emerging issues such as e-commerce or the rules on dispute settlement in PTAs. Relative

to these data collection projects, the new dataset is more comprehensive, both in terms of the

number of policy areas covered and in terms of the information on detailed disciplines in each area.

This introduction describes the scope and methodology underlying the research agenda on

deep trade agreements. It also highlights a novel set of stylized facts that can be inferred from

a rst look at the new data collected as part of this project, and oers some insights into

future applications and areas for analysis.

5

Mattoo et al. 2017, Mulabdic et al. 2017, Laget et al. 2018, Laget et al. 2019.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

6

O.2. SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY

The number of policy areas covered by PTAs has increased in the last two decades. Up until

the late 1990s, when the number of PTAs started increasing, the majority of new agreements

covered fewer than 10 policy areas. Since the 2000s, most new PTAs have covered between

10 and 20 policy areas, with some having even more than 20 (Figure O.1). In a study of 28

trade agreements signed by the US and the EU, Horn et al. (2010) identify up to 52 policy

areas that have been covered by at least one of the agreements. The inclusion of new policy

areas in PTAs is not random. As shown in Mattoo et al. (2017), trade agreements covering

few policy areas generally focus on traditional trade policy, such as tari liberalization or

customs (Table O.1). Agreements with broader coverage (between 10 and 20 policy areas)

tend to include trade-related regulatory issues, such as subsidies or technical barriers to trade.

Finally, agreements with more than 20 provisions often include policy areas that are not

directly related to trade, such as labor, environment, and movement of people.

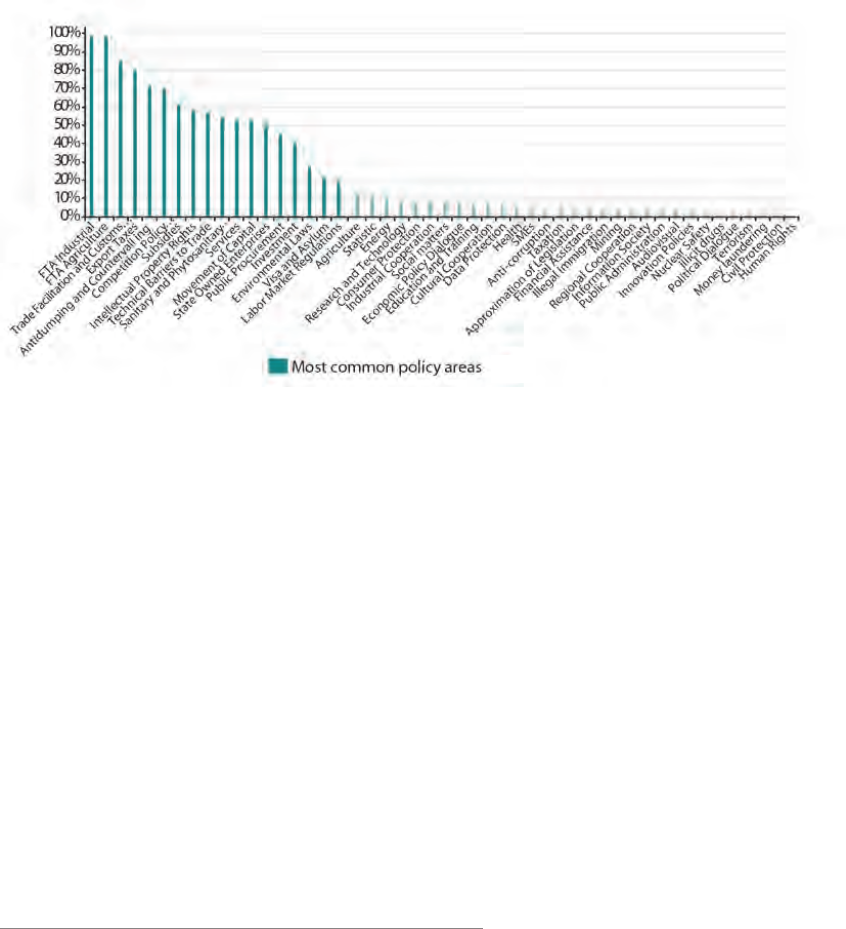

The policy areas studied in this Handbook are those that appear most frequently in trade

agreements. They include (a) a set of 18 policy areas that are covered in 20 percent or more of

trade agreements notied to the WTO (Figure O.2): (b) taris on industrial and agricultural

goods, which are covered by all trade agreements; (c) customs and export taxes, which are

regulated in more than 80 percent of PTAs; (d) services and movements of capital, which

are regulated in roughly half of the PTAs; and (e) environmental and labor issues, which

are covered by around 20 percent of all trade agreements. Other issues that are sometimes

(although infrequently) regulated in trade agreements, such as education, nuclear safety, and

Figure O.1: Number of policy areas covered in PTAs, 1970-2017

Source: WTO, Preferential Trade Agreements database, following Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta 2017.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

7

Table O.1: Share of policy areas for dierent PTAs

Source: Mattoo et al. 2017.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

8

human rights, are not included in this Handbook and could be the subject of future research.

The focus on individual areas helps us to identify specic policies that are the object of

negotiation but may obscure cross-cutting issues—such as electronic commerce—that may

be disciplined under multiple policy areas.

The classication of policy areas used in Figure O.2 deviates slightly from the one of Horn et

al. (2010).

6

Specically, for this Handbook, we decided to include rules of origin, a policy area

that was absent from the Horn et al. (2010) classication, and to treat as a single policy area:

(a) trade remedies, which include anti-dumping and countervailing measures; (b) investment,

which includes the areas covered under the WTO’s Trade-Related Investment Measures, or

TRIMs; and (c) intellectual property rights (IPR), which include the areas covered under the

WTO’s Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPs.

Trade agreements are generally assessed in terms of the market access they create. Given the

complexity of policy areas that are covered by DTAs, the metric of market access—while

still important—appears inadequate. In this introduction, we propose to dene deep trade

agreements as international arrangements that aim to regulate three (partially overlapping)

sets of policy areas (Figure O.3).

• First, the core policy areas included in DTAs aim to establish five economic

integration rights: free (or freer) movement of goods, services, capital, people, and ideas.

7

6

The Horn et al. 2010 classication was used to collect data on the extensive margin of PTA depth.

7

We use the words “aim to establish” rather than “establish” for two main reasons. First, DTAs may cover only a

subset of integration rights. Second, provisions may not be justiciable. A contribution of the new data is to identify

the extent to which integration rights are established in PTAs.

Figure O.2: Number of policy areas covered in PTAs, by policy

Source: Deep Trade Agreements Database, based on Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta 2017.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

9

The policy areas that directly impact these ows include: (a) taris and export taxes,

which aect the movement of goods; (b) services, which regulate services trade ows;

(c) investment and movement of capital, which aect the movement of capital; (d) visa

and asylum, which regulate the movement of people; and (e) intellectual property rights,

which inuence the ows of ideas.

• Second, DTAs also include policy areas that aim to support these economic integration

rights by limiting government discretion. Actions by importing governments that limit

international ows can be taken at the border and behind the border and are often of

a regulatory nature. The policy areas that fall in this category are: (a) customs; (b) rules

of origin; (c) trade remedies; (d) public procurement; (e) technical barriers to trade (TBT); (f)

sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS); (g) state-owned enterprises (SOEs); (h) subsidies;

and (i) competition policy.

8

• Third, DTAs cover policy areas that aim to enhance social or consumer welfare

by regulating the behavior of exporters. Policy areas such as environment and labor

impose obligations on exporters to further consumer or social interests in importing

countries. Rules in areas such as competition, SOEs, and subsidies can have a dual

aspect: in addition to regulating action that undermines economic integration rights,

they can aim to address distortionary actions that lower economic eciency, thus

hurting consumer or social welfare.

For each policy area, the experts followed a uniform approach to coding.

9

T h e c o d i n g t e m p l a t e s

encompass several common headings such as objectives and denitions, institutional framework,

and an enforcement mechanism, plus a series of discipline-specic questions. Under each heading,

questions on specic provisions in the agreement are formulated so that they can be answered

with Yes/No. For some policy areas, additional information is provided at the provision level,

including (a) the relationship between the coverage of the disciplines on and the corresponding

regulation in the WTO; (b) the level of enforceability of each provision;

10

(c) whether the specic

8

Some of these provisions apply only to cross-border trade in goods (e.g., customs, TBT, and SPS). Others can

also apply to cross-border trade in services (e.g., public procurement and competition policy). In some cases,

services-related provisions are included separately in a services agreement.

9

One exception is preferential taris. Dierently from the other policy areas, tari commitments apply at the

product level. The information for this area is therefore collected at the country-pair-product level. For rules

of origin a sub-sample of agreements in Latin America and East Asia, the dataset on regime-wide provisions is

accompanied by a mapping of the rules of origin that apply at the product level.

10

The legal enforceability of the PTA provisions is coded according to the language used in the text of the

agreements. It is assumed that commitments expressed with a clear, specic, and imperative legal language can

more successfully be invoked by a complainant in a dispute settlement proceeding, and therefore are more likely

to be legally enforceable. In contrast, unclearly formulated legal language might be related to policy areas that are

covered but that might not be legally enforceable.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

10

Figure O.3: A classication of policy areas in DTAs

commitment can be applied discriminatorily or whether it is de facto non-discriminatory.

Finally, when applicable, for example, in services and government procurement, the coders

included information at the sectoral level on exclusion of certain sectors from an agreement,

or the applicability of an agreement to a specic industry.

The analysis covers the realm of PTAs that are in force and notied to the WTO as of

end-2017. The basis of the coding analysis is the legal text of the trade agreements and the

relevant annexes that accompany the agreement (and have been notied to the WTO). This

approach comes with two main limitations that should be clear to the user of the database.

First, the focus on the legal text of the agreement implies that secondary law (the body of law

that derives from the principles and objectives of the treaties) has not been coded. This is a

concern particularly when assessing the depth of integration of the EU, since in most policy

areas covered in this Handbook, EU institutions have used secondary law such as regulations,

directives, and other legal instruments to pursue integration.

11

Second, the focus on the legal

text also excludes from consideration issues of implementation of the trade agreement into

national laws and regulations or subsequent annexes that the parties might agree on which

are not reported to the WTO. These are important areas for future research.

Despite the similarity in the coding approach, policy areas dier widely from each other. First,

some policy areas are inherently more complex than others and their description requires

11

Note that the gures and tables in this introduction refer to the EU as a single entity (i.e., the European Union

agreement and enlargements are excluded) and report data for EU PTAs with third countries where this concern

does not apply.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

11

a larger number of questions to reect the more detailed provisions. IPR has the highest

number of provisions (120), while labor has the lowest (18). Second, some policy areas focus

primarily on substantive provisions: specic commitments on integration, such as market

access commitments, and specic obligations such as harmonization of standards. Others

tend to have a larger number of procedural provisions, such as transparency provisions and

procedural requirements. Table O.2 provides an overview, showing the heterogeneity across

policy areas in these dierent dimensions and identifying the set of “substantive” provisions

as those that require specic integration/liberalization commitments and obligations.

Table O.2: Number of substantive and other provisions per policy area in all PTAs notied to the WTO

Source: Deep Trade Agreements Database.

Objectives 1 1 8 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 23

Scope and denitions 1 16 11 7 2 17 2 4 2 1 10 8 10 91

Transparency 4 9 3 13 3 8 6 3 10 7 4 5 1 76

Substantive commitments 17 19 13 59 3 6 2 19 20 4 3 8 11 27 20 12 243

Liberalization/ 14 8 11 19 4 1 3 4 3 13 80

Integration

Conditions/ 3 11 2 40 3 2 1 16 16 1 3 8 11 27 7 12 163

Obligations

Procedural requirements 17 8 12 3 28 10 3 28 2 2 17 130

Enforcement mechanism 1 3 8 22 1 2 4 5 7 5 4 1 63

Sectoral coverage 2 1 2 5 33 9 8 60

Specic coverage 2 1 13 9 8 2 8 1 44

Exceptions 5 6 2 35 4 4 3 1 3 63

Safeguards 1 10 31 1 43

Special and 7 2 2 11

dierentiated treatment

Institutional framework 1 1 2 2 2 6 2 11 2 1 2 32

Cooperation 2 3 1 8 3 3 1 1 1 5 4 1 33

Miscellaneous 9 6 5 2 2 1 25

Total provisions 46 64 57 95 120 30 52 51 34 59 100 36 54 35 48 38 18 937

Discipline

Export Taxes

Services

Investment

Movement of Capital

Intellectual Property Rights

Visa and Asylum

Trade Facilitation and Customs

Anti-dumping and

Countervailing Duties

Technical Barriers to Trade

Sanitary and Phytosanitary

Measures Public

Procurement Subsidies

State-Owned Enterprises

Competition Policy

Environmental Laws

Rules of Origin

Labor Market Regulations

Total provisions

Category

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

12

We also make an eort to identify the set of provisions within each policy area that are

essential to achieve the objectives of the agreement. The provisions we refer to as “essential”

comprise the set of substantive provisions plus the disciplines among procedures, transparency,

enforcement, or objectives which are viewed as indispensable and complementary to achieving

the substantive commitments. Non-essential provisions are referred to as “corollary.” A caveat

is that this exercise is based on the experts’ knowledge and, hence, is subjective. However, this

approach has the advantage of limiting the dimensionality of the data in an informed way.

12

O.3. STYLIZED FACTS

A number of new stylized facts emerge from a preliminary analysis of the data. Each of the

chapters in this Handbook provides a rst look at the data by policy area. In this introduction,

we present a bird’s-eye view of the entire dataset put together by experts. Given the dierences

among policy areas and among provisions within each policy area, this approach presents

many quantication challenges, which are discussed below. In this section, we rely on simple

counts of the provisions and on coverage ratios

13

to investigate the evolution of the content

of deep trade agreements. The underlying assumption in this approach is that deeper trade

agreements imply a larger number of provisions.

As shown in chapter 1,

14

liberalization in PTAs has reduced trade-weighted average tari rates

to less than 5 percent for more than two-thirds of countries (Figure O.4). While there are still

12

A statistical approach on how to assess the importance of specic provisions included in the dierent policy

areas in explaining trade outcomes is presented in section O.4.

13

The coverage ratio is dened as the share of provisions for a policy area contained in a given agreement relative

to the maximum number of provisions in that policy area or agreement.

14

Chapter 1 by Espitia et al. 2020.

Figure O.4: Taris in PTAs and MFN taris

Source: Chapter 1 by Espitia et al. 2020.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

13

pockets of high protection in some countries, most notably lower-income economies, PTAs

have been broadly successful in committing national governments to maintaining low taris.

Trade-weighted applied taris are, on average, 2.3 percentage points lower than average

most-favored-nation (MFN) rates, with gaps of greater than 6 percentage points for countries

like Tunisia, Morocco, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Namibia, and the Lao People’s Democratic

Republic. So, while from an eciency perspective, preferential tari liberalization is inferior

to non-preferential liberalization, the commitments countries have made in the network

of preferential trade agreements may provide a safety net at a time when trade tensions are

escalating and some countries are disregarding their multilateral commitments.

The number of commitments that governments have made in trade agreements, particularly

since the early 2000s, has increased over time. Figure O.5 shows how the coverage ratio

has changed over time for the 17 policy areas analyzed in this Handbook (all but taris) in

aggregate. With only a few exceptions, the majority of new PTAs signed after 2000 have a

coverage ratio higher than 25 percent. This stands in sharp contrast to the trade agreements

signed in the 1980s and 1990s, when coverage ratios were below 15 percent and, in many

cases, even below 5 percent. The reduction in taris accomplished through preferential

trade liberalization, together with the increased depth of agreements over time, suggests

that countries that are willing to cut taris reciprocally may also be willing to accept deeper

mutual commitments in other areas.

While the overall number of provisions is suggestive, it can hide important elements of

the evolution of deep trade agreements. First, as discussed above, some provisions imply

substantive commitments while others concern broad objectives, denitions, or procedural

matters. Second, deep trade agreements, as dened in this Handbook, do not only concern

themselves with market access in goods, but also aim to establish freedom of mobility for

Figure O.5: Number of agreements over time vs. average coverage ratio

Note: Coverage ratio refers to the share of provisions contained in a given agreement relative to the maximum

number of provisions. European Union agreement and enlargements excluded.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

14

services, capital, ideas, and people, as well as regulating policy areas that have an impact

on consumer and/or social welfare, such as labor and the environment. To gain a better

understanding of how the commitments in PTAs have changed over time, we look at the

evolution of coverage ratios by policy area.

Figure O.6 shows that the coverage of essential disciplines in PTAs has increased over time

across all policy areas. This is most clearly the case for the policy areas aimed at facilitating

the ows of goods (customs and trade facilitation), capital (investment and movement of

capital), and services. IPR and movement of people (visa and asylum) also saw a steady

but less remarkable increase in essential commitments over time. Along with economic

integration rights, PTAs increasingly include essential commitments in policy areas that

support these rights or impose obligations on exporters. The ones that appear to stand

out are subsidies, competition, and SOEs, areas that are either excluded from the WTO or

for which reform of multilateral rules is considered dicult. Interestingly, while essential

commitments in labor have largely increased in recent years, this happened to a lesser

extent for provisions on the environment.

The presumption is that the increase in the essential disciplines in deep PTAs has been driven

by countries taking on more substantive commitments over time. Indeed, Figure O.7 shows

Figure O.6: Coverage ratios by policy area, over time

Note: Coverage ratio by policy area refers to the share of provisions for a policy area contained in a given

agreement relative to the maximum number of provisions in that policy area. Years refer to entry-into-force date.

European Union agreement and enlargements excluded.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

15

that this is the case, but it also uncovers interesting insights about the evolution of non-

substantive commitments. We focus on the three (numerically) most relevant non-substantive

provisions: procedural rules, transparency, and enforcement provisions. The deepening of

substantive commitments has been accompanied by an increase in the number of corollary

provisions, suggesting that achieving deeper commitments may require more procedural

rules for implementation, transparency, and enforcement. A second insight is that, while these

disciplines are all necessary to render substantive commitments in trade agreements eective,

they have evolved dierently in recent years. Starting in the early 2000s, the relevance of

enforcement provisions in DTAs has increased disproportionally relative to procedural and

transparency provisions. The growing enforcement capacity of DTAs may help explain the

success of these institutional arrangements as tools for deep integration.

When we break down the trade agreements by level of development of the signatories,

we observe two facts. First, the deepest PTAs are those involving developed economies,

followed by PTAs between developed and developing economies. PTAs between

developing countries are the shallowest. Indeed, there is a sizeable gap between average

coverage ratios for the latter group of PTAs relative to the rst two (Figure O.8). This

could reect a focus of negotiations on tari s and traditional trade barriers, which are still

high for several low-income economies. Second, in terms of composition, PTAs between

developed countries and those between developed and developing economies include

similar shares of provisions establishing economic integration rights, supporting these

rights, and aiming to regulate exporters (Figure O.9). PTAs between developing countries

are shallower across the board, with a stronger gap in areas such as environment and labor

that aim at improving social welfare.

Figure O.7: Substantive provisions and a breakdown of non-substantive provisions in PTAs, over time

Note: Coverage ratio refers to the share of provisions for a policy area contained in a given agreement relative

to the maximum number of provisions in that policy area. Years refer to entry-into-force date. European Union

agreement and enlargements excluded.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

16

Figure O.8: Inclusion of substantive commitments in PTAs, by level of development

Note: Coverage ratio refers to the share of provisions for a policy area contained in a given agreement relative

to the maximum number of provisions in that policy area. Years refer to entry-into-force date. European Union

agreement and enlargements excluded.

Figure O.9: Coverage ratio by type of policy and level of development

Note: Coverage ratio refers to the share of provisions for a policy area contained in a given agreement relative

to the maximum number of provisions in that policy area. Years refer to entry-into-force date. European Union

agreement and enlargements excluded.

We next analyze the depth of trade agreements by country. Here, we focus on the

substantive commitments.

15

As several countries have multiple agreements with dierent

levels of depth, we present the average number of substantive commitments per country

in panel a of Figure O.10 and the maximum number in panel b of Figure O.10. The main

takeaway is that developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North

Africa, South America, South Asia, and, to a lesser extent, East Asia tend to have fewer

substantive commitments in trade agreements relative to advanced economies. The few

15

Annex Tables O.A.1 and O.A.2 provide other indicators by PTA and by country.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

17

Figure O.10: Substantive provisions in PTAs by country

a. Average number of provisions

b. Maximum number of provisions

exceptions include countries in South America that are signatories to the Pacic Alliance

and other developing economies that have signed deep trade agreements with an advanced

trade partner, such as Mongolia with Japan and Caribbean countries with the EU. In terms

of depth as measured here, North America and Europe are the most integrated regions,

through NAFTA and its successor agreement, and through the agreements the EU has

signed with neighboring countries. East Asia is a region with a mixed prole: the network

of ASEAN agreements includes most countries but tends to have fewer substantive

commitments relative to North America and Europe, except for some countries such as

Vietnam, which have signed on to the Comprehensive Agreement for the Trans-Pacic

Partnership (with a coverage ratio of 61 percent).

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

18

With the increasing depth and complexity of trade agreements, both similarities and

dissimilarities between PTAs could potentially increase. Older agreements that covered

only preferential tariff liberalization and other aspects of market access tended to

be very similar. As PTAs now cover more ground, there can be provisions that are

included in two agreements, making them more similar, or there can be provisions

that are covered by one PTA but not by another, making them more dissimilar. To

capture this information, we construct a similarity index for DTAs, calculated as the

ratio between the number of provisions for which two agreements have a “yes” (a

measure of similarity) and the total number of provisions covered by the agreements,

independently of whether they have the same answer or not. The closer the similarity

index is to one (or zero), the more (or less) similar are the two DTAs; i.e., they include

the same type(s) of provisions.

Figure O.11 plots the degree of similarity for the PTAs signed by the three major trading

blocs: the European Union, the United States, and Japan. Each color represents a DTA

signed by a third country with the US (green bubbles), EU (purple bubbles), or Japan (pink

bubbles). The size of the bubbles represents the depth of the agreements, measured as the

number of provisions covered. Each agreement is connected to the one which is most similar

within a trading bloc. The gure also links the three trading blocs, by connecting the pair of

agreements that are the most similar between two blocs.

As expected, within each bloc, DTAs are highly similar: up to 0.89 for the US (US-Peru;

US-Colombia), up to 0.80 for the EU (EU-Moldova; EU-Ukraine), and up to 0.75 for

Japan (Japan-Indonesia; Japan-Mongolia). This fact often reects a “template eect,” where

the EU, the US, and Japan tend to negotiate based on a template oered to third countries.

Interestingly, the similarity of DTAs is relatively high even across blocs, although lower

than within blocs. For example, the EU-Republic of Korea agreement shares more than

50 percent of the provisions with the Japan-Switzerland agreement (similarity index of

0.54) and with the US-Peru agreement (similarity index of 0.51). These results indicate that

concerns about the fragmentation of the global trade system have some foundation (i.e., they

do not share almost half of provisions), but also point to substantial similarities—based on

which multilateral rules can be agreed upon.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

19

Figure O.11: Similarity of agreements

Note: The size of the bubbles represents the depth of a trade agreement, as captured by the number of provisions

included in the agreement. Each edge connects an agreement with one that is most similar. Purple bubbles

represent EU agreements with non-EU countries, green bubbles represent US agreements, and pink bubbles

represent Japan’s agreements.

O.4. THE CHALLENGE OF QUANTIFYING THE EFFECTS OF DTAs

Quantication of the eects of DTAs poses a serious challenge. DTAs cover heterogeneous

areas: taris, contingent protection, export taxes, customs procedures, technical barriers in

goods; a wide range of restrictions across modes in services; investment measures, subsidies,

procurement, state enterprises, competition policy aecting both trade and investment in

goods and services, visas and asylum, and a range of regulatory requirements aecting labor

mobility; and a variety of policies aecting the protection of intellectual policy rights and

the environment. How can the diversity of policies be quantied and aggregated within

separate areas? How can we aggregate across the dierent areas? We briey discuss here

two approaches to quantication—directly constructed indices and indirectly estimated

measures—and some analytical issues going forward.

O.4.1 Directly constructed indices

The count variables and coverage ratios presented in the previous section are the simplest

directly constructed indices of depth. They provide an immediate view of how commitments

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

20

in PTAs have changed over time, across countries, and for subsets of provisions. Still, aggregate

indicators based on some form of counting disregard the fact that DTAs cover multiple policy

areas and sectors and that the “value” of each provision is unlikely to be the same even within

the same policy area.

In some cases, it may be possible to construct a hierarchy of measures. For example, in

the areas of services and government procurement, provisions could be divided into three

tiers. Tier 1 would comprise provisions ensuring market access and national treatment at

entry. Tier 2 would comprise provisions on post-entry operation; e.g., preferences or osets.

Tier 3 would comprise procedural rules limiting discretion in licenses and awards. The

construction of an index could then be lexicographic, in that we would consider rst only

dierences between countries or sectors in Tier 1 and move to subsequent tiers only to break

ties. Such an approach is ideally suited to the construction of an ordinal rather than cardinal

(i.e., qualitative rather than quantitative) measure.

A pragmatic approach to overcoming some of the constraints to constructing representative

indices is to rely on experts’ judgment. This is the method adopted in this Handbook. The

individual chapters will oer a disaggregated set of stylized facts for each policy area using count

variables, coverage ratios, and the individual assessment of the authors of the key provisions in

each policy area. We have already discussed the distinction between substantive and essential

provisions. Some chapters go even beyond these categories. For instance, the chapter on

SOEs (Rubini and Wang 2020) identies four commitments concerning issues of ownership,

discrimination, subsidization, and anti-competitive behavior as key. The chapter on technical

barriers to trade (Espitia et al. 2020) identies a subset of seven commitments which are key to

achieving deep integration in the area of technical regulations. This type of information can be

used in the estimation exercises we discuss below, as it allows the researcher to address problems

associated with large numbers of possible variables at hand, such as multicollinearity (i.e., the

high correlation between the dierent provisions within and across policy areas).

O.4.2 Indirectly estimated measures

These measures are obtained by estimating the impact of the provisions on a variable of

interest. For example, we could infer the value of individual provisions by estimating their

impact on bilateral trade, controlling for other inuences. In principle, each binary element

in the relevant DTA areas could be included in a country-product import regression as a

right-hand variable while controlling for applied policies, including taris and non-tari

measures. Similar methods have been used to estimate the Overall Trade Restrictiveness

Index.

16

However, even for trade in goods we have limited degrees of freedom, and in other

16

Kee, Nicita, and Olarreaga 2009.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

21

areas (such as services), we do not have suciently ne outcome data. In these areas, it may

be necessary to take a hybrid approach, based on rst constructing more aggregated indices.

Another approach is to quantify the eects of DTAs and build indicators of depth using new

statistical methods. As a rst example, we employ machine learning techniques to detect the

inuential variables/provisions in DTAs for trade.

17

“Machine learning” is a generic term

referring to a wide variety of algorithms which detect a certain pattern from a large dataset,

often referred to as “Big Data,” and make predictions based on that pattern. In this case, we

use a method called Random Forest (RF) to calculate the importance of each variable/

provision for international trade ows.

18

Specically, we run as a rst step a structural gravity

model with the standard set of xed eects and then use the residuals as the left-hand

variable in the RF.

Figure O.12 shows the boxplot of scores calculated by the RF of variables/provisions in

PTAs belonging to the 17 (non-tari) policy areas analyzed in this Handbook.

19

The areas

are colored according to their categorization into the three main groups illustrated in Figure

O.3; dark green indicates policies that establish economic integration rights, purple is assigned

to those supporting these rights, and light green to those that promote welfare. Each box

shows the range of the rst (25 percent) and third (75 percent) quartiles, and the black line

in the box shows the median of the scores. The vertical lines extending from the box indicate

the variability outside the above quartiles, and the dots outside of the line are regarded as

outliers. Boxplots are ordered according to the magnitude of the median.

Focusing on the entire set of PTAs, we nd that provisions such as investment, subsidies,

and services, and to a lesser extent, rules of origin and movement of capital have a median

score above the overall score average, suggesting that these policy areas are good predictors of

bilateral trade, after controlling for the usual gravity determinants of trade ows. Provisions

in policy areas such as SPS, environmental laws, and visa and asylum are located at the other

extreme of the distribution of median scores, suggesting a more limited role in predicting

bilateral trade ows. The size of the boxes and the vertical lines also indicate that there are

policy areas such as movement of capital and IPR for which the contribution to trade is

more or less uniform across provisions. For other policy areas such as competition policy and

SOEs, there is more heterogeneity within provisions in terms of their contribution to trade.

17

This exercise has been carried out in collaboration with Kazusa Yoshimura and Edith Laget. Parallel work

by Breinlich et al. (2020) also uses machine learning techniques to precisely quantify the impact of individual

provisions in trade agreements on trade ows.

18

RF is a frequently used machine learning algorithm that predicts a Y variable by combining the results from

hundreds of regression/classication trees. It has the merit of not imposing a linear relationship between the Y and

X variables, which is an advantage when analyzing the impact of a highly heterogenous set of variables, such as the

provisions in PTAs.

19

A score should not be interpreted as a coecient in a regression analysis. It measures how much the accuracy

of the prediction for Y gets worse if the particular X variable is randomly permuted.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

22

Figure O.12: Boxplot of scores calculated by the RF of variables/provisions in PTAs

O.4.3 Quantication challenges: some analytical issues going forward

Looking ahead, there is a need for stronger analytical underpinnings for any quantication

exercise. Ideally, the “value” of a commitment must be evaluated in light of the objective

that the provision of the deep trade agreement is trying to achieve. In other words, depth

indicators could use dierent weights, depending on whether the outcome variable is market

access, welfare, or another metric. For trade policy, market access may seem to be the most

obvious metric, but for intellectual property rights, welfare may be the more relevant. In still

other areas, such as competition policy, both might be relevant: the market access measure

would include only provisions restricting barriers to foreign entry and operation while the

welfare measure would include provisions requiring action against anti-competitive behavior

aecting consumers.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

23

One indicator cannot provide a measure of both the trade distortions a country imposes

on its trading partners (market access) and the trade distortions a country imposes on itself

(welfare). For a market access-based measure in the goods context, the relevant question

could be: what is the uniform tari that if imposed on home imports instead of the existing

structure of protection would leave aggregate imports at their current level? And for a

welfare-based measure: what is the uniform tari that if applied to imports instead of the

current structure of protection would leave home welfare at its current level? The relationship

between the two measures is likely to vary across policy areas: positive correlation for taris;

perhaps negative for environmental standards; and ambiguous for intellectual property rights.

A further issue relates to whether we should be interested in what legal commitments do

to the level of a policy or to its variance. Provisions such as the elimination of taris, or of a

national treatment rule in services or government procurement, x the level of protection

at zero. Provisions which legally bind policy (e.g., the permissible levels of fees, subsidies, or

preferences) truncate the distribution of possible policy outcomes by reducing the variance

and hence the expected level of protection. Provisions which reduce discretion, such as

rules on customs valuation, licensing, or procurement procedures, narrow the distribution of

possible policy outcomes.

Finally, we also need to consider whether we should assess agreements per se or agreements

relative to applied policies. If we have the relevant data, the mean and variance shift would

ideally be assessed relative to the prevailing policy (and not just the law or policy on paper

but how it is implemented). For example, a legally binding tari at 10 percent might have a

dierent value depending on whether the existing tari was 5, 10, or 20 percent. The creation

of new databases on applied policies in goods and services trade may facilitate such analysis.

O.5. CONCLUSIONS

The World Development Report 2009 made the case that “thicker” borders between countries

hurt economic growth, especially in developing countries. Policies that directly or indirectly

restrain the international mobility of goods, services, capital, people, and ideas limit, among

other things, the scale of the market, which is vital for development.

20

Deep trade agreements

aim at establishing the rights of economic integration, protecting these rights from importing

governments’ actions that could undo them, and regulating actions of exporters that can have

negative welfare eects. These agreements have developed over time into a key institutional

mechanism for countries to overcome the constraints to economic development created by

the thick borders that fragment markets.

20

World Bank 2009.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

24

Of course, deep integration is not an end in itself. First, countries at dierent levels of

development may have dierent institutional needs, and trade agreements still need to strike

the right balance between rules in PTAs and the needed discretion at the national level to

pursue desirable social objectives. Second, while many deep provisions may be de facto non-

discriminatory and apply to members and non-members alike, there is still a tension between

the proliferation of regional approaches and multilateral rules enshrined in the WTO.

Therefore, from the perspective of both economic development and global governance, the

ecient set of rules in DTAs is an empirical question.

The wealth of information on the content of the policy areas commonly included in PTAs

could provide new impetus to the analysis of the determinants and impact of deep trade

agreements. Such analysis would also provide the necessary tools to further understand the

opportunities and challenges that countries face in terms of negotiation and implementation

of deep trade agreements.

We suggest three areas of work going forward. A rst step is to improve the measurement

of the depth of trade agreements and quantication of its eects. Beyond simple count

variables and coverage ratios, more work will be needed to develop new analytic methods

to overcome the challenges discussed in the previous section. As shown, machine learning

techniques may provide a useful, innovative approach. Second, the detailed information at

the level of individual policy areas could inform a series of studies to assess how specic

provisions impact trade and other relevant economic variables. As trade policy experts well

understand, the devil is often in the details. Finally, the new data and analysis could provide

essential information to policymakers on priorities for the negotiation and implementation

of trade agreements: nding what potential partners include in their trade deals, identifying

best practices in DTAs and areas where practices diverge or overlap across dierent players,

and assessing gaps between international commitments and domestic legislation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are highly indebted to Alvaro Espitia for providing background research for this

introduction and more broadly for his outstanding contribution to the production of this

Handbook. Kazusa Yoshimura and Edith Laget worked on the quantication exercise using

machine learning techniques in Section O.4.

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

25

REFERENCES

Acharya, R. (ed.) 2016. Regional trade agreements and the multilateral

trading system. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baldwin, R. 2010. 21st century regionalism: Filling the gap between

21st century trade and 20th century trade rules. Working Paper

2010-31, Geneva Graduate Institute, Geneva.

Breinlich, H., V. Corradi, N. Rocha, M. Ruta, J. Santos Silva, and

T. Z y l k i n . 2 0 2 0 . “ M a c h i n e l e a r n i n g i n i n t e r n a t i o n a l t r a d e r e s e a r c h :

Evaluating the impact of trade agreements.” Unpublished,

University of Surrey and World Bank.

Dür, A., L. Baccini, and M. Elsig. 2014. The design of international

trade agreements: Introducing a new dataset. Review of International

Organizations 9(3): 353-75.

Espitia, A., A. Mattoo, M. Mimouni, X. Pichot, and N. Rocha.

2020. Preferential taris. Chapter 1 in Handbook of Deep Trade

Agreements,, edi te d by A. M at too, N. Ro cha, a nd M. R uta..

Wa sh in g to n, D C: Wo r ld B an k .

Espitia, A., S. Pardo, R. Piermartini, and N. Rocha. 2020.

Te c h n i c a l b a r r i e r s t o t r a d e . C h a p t e r 1 2 i n Handbook of Deep

Tra d e Ag r ee ment s , edit ed by A. Ma ttoo, N. Ro ch a, and M . R ut a..

Wa sh in g to n, D C: Wo r ld B an k .

Freund, C., and E. Ornelas. 2010. Regional trade agreements.

Annual Review of Economics 2: 139-66.

Hofmann, C., A. Osnago, and M. Ruta. 2017. Horizontal depth: A

new database on the content of preferential trade agreements. Policy

Research Working Paper 7981, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Horn, H., P.C. Mavroidis, and A. Sapir. 2010. Beyond the WTO?

An anatomy of EU and US preferential trade agreements. Wo rld

Economy 33: 1565-88.

Kee, Hiau Looi, Alessandro Nicita, and Marcelo Olarreaga.

2009. Estimating trade restrictiveness indices. Economic Journal

119 (534): 172–99.

Laget, E., A. Osnago, N. Rocha, and M. Ruta. 2018. Deep trade

agreements and global value chains. Policy Research Working

Paper 8491, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Laget, E., N. Rocha, and G. Varela. 2019. Deep trade agreements

and foreign direct investments. Unpublished paper,World Bank,

Wa s h i n g t o n , D C .

Limao, N. 2016. Preferential trade agreements. In Handbook

of commercial policy, vol. 1, edited by K. Bagwell and R. Staiger.

Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Mattoo, A., A. Mulabdic, and M. Ruta. 2017. Trade creation and

trade diversion in deep agreements. Policy Research Working Paper

8206, World Bank, Washington, DC. Paper funded by the World

Bank’s Strategic Research Program.

Mulabdic, A., A. Osnago, and M. Ruta. 2017. Deep integration

and UK-EU trade relations. Policy Research Working Paper

7947,World Bank, Washington, DC.

Rubini, L., and T. Wang. 2020. State-owned enterprises. Chapter

15 in Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements,, e dit ed by A. M attoo, N.

Rocha, and M. Ruta.. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Viner, J. 1950. The customs union issue. New York: Carnegie

Endowment for International Peace.

Wo r l d B a n k . 2 0 0 9 . Wor ld d evelo pme nt r epo rt 200 9: Reshaping economic

geography. Wa s h i n g t o n , D C : Wo r l d B a n k .

———. 2019. Wor ld de ve lopm ent re por t 20 20: Trading for development

in the age of global value chains. Wa s h i n g t o n , D C : Wo r l d B a n k .

Wo r l d Tr a d e O r g a n i z a t i o n . 2 0 1 1 . World trade report 2011: The WTO

and preferential trade agreements – From co-existence to coherence. Geneva:

WTO.

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

26

Annex Table O.A.1: Number of provisions included and coverage ratio – by agreement

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

1958 EC Treaty 121 24 13.5 10.8

1960 European Free Trade Association (EFTA) 224 38 24.9 17.0

1961 Central American Common Market (CACM) 155 44 17.2 19.7

1971 EU - Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT) 57 11 6.3 4.9

1973 EC-Iceland 57 11 6.3 4.9

EC-Norway 57 9 6.3 4.0

EC-Switzerland-Liechtenstein 58 9 6.5 4.0

EC (9) Enlargement 127 31 14.1 13.9

Caribbean Community and 152 36 16.9 16.1

Community Market (CARICOM)

1976 APTA 68 10 7.6 4.5

1977 Australia - Papua New Guinea (PATCRA) 19 3 2.1 1.3

EC-Syrian Arab Republic 30 2 3.3 0.9

1981 South Pacic Regional Trade and Economic 21 2 2.3 0.9

Cooperation Agreement (SPARTECA)

Latin American Integration Association 32 7 3.6 3.1

EC (10) Enlargement 114 30 12.7 13.5

1983 Australia-New Zealand (ANZCERTA) 108 35 12.0 15.7

1985 US-Israel 90 7 10.0 3.1

1986 EC Enlargement (12) 118 32 13.1 14.3

1987 Panama - Dominican Republic 20 1 2.2 0.4

1988 CAN 116 25 12.9 11.2

1989 Global System of Trade Preferences among 7 0 0.8 0.0

Developing Countries (GSTP)

1991 Lao PDR-Thailand 9 1 1.0 0.4

EU - Andorra 30 6 3.3 2.7

MERCOSUR 161 32 17.9 14.3

1992 Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) 46 8 5.1 3.6

Turkey-EFTA 120 30 13.3 13.5

ASEAN free trade area 133 18 14.8 8.1

1993 Russian Federation - Uzbekistan 34 13 3.8 5.8

Russian Federation - Tajikistan 36 8 4.0 3.6

Russian Federation - Turkmenistan 40 13 4.4 5.8

Russian Federation - Azerbaijan 41 15 4.6 6.7

Faroe Islands - Norway 65 17 7.2 7.6

ECOWAS 99 18 11.0 8.1

EFTA-Israel 101 22 11.2 9.9

1994 MSG 26 3 2.9 1.3

Georgia - Russian Federation 42 10 4.7 4.5

CIS 109 23 12.1 10.3

COMESA 158 40 17.6 17.9

EEA 213 42 23.7 18.8

NAFTA 360 68 40.0 30.5

ANNEX

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

27

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

1995 South Asian Preferential Trade 11 2 1.2 0.9

Agreement (SAPTA)

Faroe Islands - Switzerland 21 6 2.3 2.7

Kyrgyz Republic - Armenia 37 11 4.1 4.9

Ukraine-Turkmenistan 38 8 4.2 3.6

Kyrgyz Republic - Kazakhstan 39 7 4.3 3.1

Armenia - Moldova 39 10 4.3 4.5

EC Enlargement (15) 111 31 12.3 13.9

Colombia - Mexico 254 61 28.3 27.4

1996 Ukraine - Azerbaijan 34 6 3.8 2.7

Armenia - Turkmenistan 36 10 4.0 4.5

Ukraine - Uzbekistan 37 5 4.1 2.2

Georgia - Azerbaijan 38 11 4.2 4.9

Georgia - Ukraine 40 12 4.4 5.4

Armenia - Ukraine 40 7 4.4 3.1

Kyrgyz Republic - Moldova 42 10 4.7 4.5

EC-Turkey 110 40 12.2 17.9

1997 Russian Federation - Belarus - Kazakhstan 12 1 1.3 0.4

EAEC 52 8 5.8 3.6

EC-Faroe Islands 59 8 6.6 3.6

Turkey - Israel 74 15 8.2 6.7

EC-West Bank and Gaza 107 21 11.9 9.4

Canada - Israel 141 21 15.7 9.4

Canada - Chile 290 62 32.3 27.8

1998 PAFTA 11 0 1.2 0.0

Kyrgyz Republic - Uzbekistan 37 7 4.1 3.1

Georgia - Armenia 37 10 4.1 4.5

Ukraine-Kazakhstan 37 6 4.1 2.7

Kyrgyz Republic - Ukraine 39 10 4.3 4.5

EC-Tunisia 126 35 14.0 15.7

1999 Georgia - Kazakhstan 40 9 4.4 4.0

Economic and Monetary Community 57 14 6.3 6.3

of Central Africa (CEMAC)

EFTA - West Bank and Gaza 100 24 11.1 10.8

EFTA - Morocco 130 31 14.5 13.9

Chile - Mexico 265 69 29.5 30.9

2000 Georgia - Turkmenistan 40 10 4.4 4.5

West African Economic and 61 12 6.8 5.4

Monetary Union (WAEMU)

Turkey - FYR Macedonia 73 14 8.1 6.3

Southern African Development Community 84 22 9.3 9.9

East African Community (EAC) 103 32 11.5 14.3

EC-Mexico 121 20 13.5 9.0

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

28

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

2000 EC-Morocco 122 27 13.6 12.1

EC-Israel 125 31 13.9 13.9

EC-South Africa 128 33 14.2 14.8

Israel - Mexico 139 18 15.5 8.1

2001 Armenia - Kazakhstan 38 11 4.2 4.9

India-Sri Lanka 39 8 4.3 3.6

Ukraine - FYR Macedonia 65 19 7.2 8.5

US-Jordan 80 22 8.9 9.9

EC-FYR Macedonia 171 46 19.0 20.6

New Zealand - Singapore 179 34 19.9 15.2

Dominican Republic - Central America 189 44 21.0 19.7

EFTA - Mexico 233 37 25.9 16.6

2002 Asia Pacic Trade Agreement (APTA) - 29 3 3.2 1.3

Accession of China

EU-San Marino 32 11 3.6 4.9

Ukraine – Tajikistan 39 8 4.3 3.6

EFTA - FYR Macedonia 121 26 13.5 11.7

EFTA - Jordan 122 25 13.6 11.2

Canada - Costa Rica 155 35 17.2 15.7

EC-Jordan 162 46 18.0 20.6

Chile - Costa Rica (Chile - Central America) 230 49 25.6 22.0

Chile - El Salvador (Chile - Central America) 230 49 25.6 22.0

Japan-Singapore 237 29 26.4 13.0

2003 GCC 32 3 3.6 1.3

Pacic Island Countries Trade Agreement (PICTA) 37 1 4.1 0.4

India - Afghanistan 37 4 4.1 1.8

China - Macao SAR, China 60 14 6.7 6.3

Turkey - Bosnia and Herzegovina 77 16 8.6 7.2

EC-Lebanon 93 32 10.3 14.3

EFTA - Singapore 264 52 29.4 23.3

Panama - El Salvador (Panama - Central America) 271 59 30.1 26.5

EC-Chile 301 54 33.5 24.2

Australia-Singapore 303 76 33.7 34.1

2004 SACU 25 7 2.8 3.1

CEZ 45 13 5.0 5.8

China-Hong Kong SAR, China 64 12 7.1 5.4

EC Enlargement (25) 103 29 11.5 13.0

EC-Arab Rep. of Egypt 132 32 14.7 14.3

EFTA - Chile 232 38 25.8 17.0

Mexico - Uruguay 233 59 25.9 26.5

Panama - Taiwan, China 271 73 30.1 32.7

US-Singapore 318 56 35.4 25.1

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

29

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

2004 Chile-Rep. of K orea 330 55 36.7 24.7

US-Chile 348 64 38.7 28.7

2005 Pakistan - Sri Lanka 43 7 4.8 3.1

Ukraine - Moldova 65 14 7.2 6.3

Turkey - Tunisia 87 18 9.7 8.1

Turkey - West Bank and Gaza 104 15 11.6 6.7

Jordan - Singapore 120 17 13.3 7.6

EC-Algeria 132 37 14.7 16.6

EFTA - Tunisia 145 30 16.1 13.5

Thailand - New Zealand 178 28 19.8 12.6

China-ASEAN 184 36 20.5 16.1

Australia-Thailand 197 33 21.9 14.8

India-Singapore 197 37 21.9 16.6

Japan-Mexico 252 35 28.0 15.7

US-Australia 324 61 36.0 27.4

2006 India - Bhutan 8 1 0.9 0.4

Ukraine-Belarus 36 8 4.0 3.6

SAFTA 39 2 4.3 0.9

Russian Federation - Serbia 39 7 4.3 3.1

Iceland - Faroe Islands 66 18 7.3 8.1

Turkey - Morocco 85 18 9.5 8.1

Chile-China 130 22 14.5 9.9

EC-Albania 158 39 17.6 17.5

Guatemala – Taiwan, China 227 52 25.3 23.3

US-Bahrain 237 38 26.4 17.0

Japan-Malaysia 245 47 27.3 21.1

Trans-Pacic Strategic Economic Partnership 260 52 28.9 23.3

US-Morocco 273 52 30.4 23.3

Panama - Singapore 274 52 30.5 23.3

EFTA-Rep. of Korea 296 47 32.9 21.1

CAFTA-Dominican Republic 300 53 33.4 23.8

Rep. of Korea-Singa pore 315 54 35.0 24.2

2007 Agadir Agreement 22 0 2.4 0.0

East African Community (EAC) - 40 14 4.4 6.3

Accession of Burundi

Mauritius and Pakistan 42 7 4.7 3.1

Chile-India 70 11 7.8 4.9

Arab Rep. of Egyp t - Tur key 84 18 9.3 8.1

EC Enlargement (27) 102 29 11.3 13.0

Turkey - Syrian Arab Republic 109 17 12.1 7.6

China-Pakistan 120 10 13.3 4.5

EFTA - Lebanon 142 36 15.8 16.1

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

30

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

2007 EFTA - Arab Rep. of Egypt 150 37 16.7 16.6

CEFTA 153 55 17.0 24.7

Chile-Japan 244 39 27.1 17.5

Japan-Thailand 267 55 29.7 24.7

2008 Japan-ASEAN 67 8 7.5 3.6

Turkey - Albania 73 14 8.1 6.3

Turkey - Georgia 78 15 8.7 6.7

EFTA - SACU 108 21 12.0 9.4

Panama - Chile 145 27 16.1 12.1

EC-Montenegro 194 63 21.6 28.3

Brunei Darussalam - Japan 197 34 21.9 15.2

EC-Bosnia Herzegovina 204 57 22.7 25.6

Pakistan - Malaysia 212 37 23.6 16.6

Japan-Indonesia 222 38 24.7 17.0

Chile - Honduras (Chile - Central America) 226 49 25.1 22.0

El Salvador - Honduras - Taiwan, China 233 54 25.9 24.2

Panama - Costa Rica (Panama - Central America) 241 49 26.8 22.0

Japan-Philippines 251 60 27.9 26.9

China-New Zealand 256 50 28.5 22.4

EC-CARIFORUM 334 74 37.2 33.2

Nicaragua - Taiwan, China 334 95 37.2 42.6

2009 India - Nepal 19 0 2.1 0.0

MERCOSUR-India 52 7 5.8 3.1

EU-Côte d’Ivoire 78 11 8.7 4.9

EU - Papua New Guinea/Fiji 96 14 10.7 6.3

EU-Cameroon 108 18 12.0 8.1

Canada-EFTA 158 23 17.6 10.3

China-Singapore 214 39 23.8 17.5

Colombia - Northern Triangle 223 41 24.8 18.4

(El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras)

Panama - Nicaragua (Panama - Central America) 231 45 25.7 20.2

Panama - Guatemala (Panama - Central America 237 49 26.4 22.0

Panama - Honduras (Panama - Central America) 239 49 26.6 22.0

Japan-Vietnam 250 38 27.8 17.0

Peru - Chile 258 64 28.7 28.7

Chile - Colombia 266 60 29.6 26.9

US-Oman 286 59 31.8 26.5

Japan-Switzerland 292 47 32.5 21.1

Peru - Singapore 306 57 34.0 25.6

Chile-Australia 332 51 36.9 22.9

US-Peru 355 74 39.5 33.2

Canada-Peru 375 79 41.7 35.4

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

31

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

2010 Turkey - Montenegro 71 15 7.9 6.7

Turkey - Serbia 71 14 7.9 6.3

EFTA - Serbia 162 30 18.0 13.5

EFTA - Albania 173 29 19.2 13.0

ASEAN-India 175 29 19.5 13.0

ASEAN-Rep. of Korea 194 31 21.6 13.9

EU-Serbia 209 56 23.2 25.1

Chile - Guatemala (Chile - Central America) 228 49 25.4 22.0

New Zealand - Malaysia 245 44 27.3 19.7

Rep. of Korea - Ind ia 252 45 28.0 20.2

China-Peru 260 44 28.9 19.7

ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand 260 59 28.9 26.5

2011 South Asian FTA (SAFTA) - 30 0 3.3 0.0

Accession of Afghanistan

Turkey - Jordan 82 16 9.1 7.2

Turkey - Chile 93 19 10.3 8.5

China - Costa Rica 176 23 19.6 10.3

Hong Kong SAR, China - New Zealand 211 42 23.5 18.8

India-Malaysia 213 32 23.7 14.3

India-Japan 234 40 26.0 17.9

EFTA - Peru 291 61 32.4 27.4

EFTA - Colombia 330 63 36.7 28.3

EU - Rep. of Korea 392 81 43.6 36.3

Canada - Colombia 401 79 44.6 35.4

Peru - Rep. of Korea 403 77 44.8 34.5

2012 Treaty on a Free Trade Area between members 37 5 4.1 2.2

of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

El Salvador-Cuba 51 10 5.7 4.5

EU - Eastern and Southern Africa 78 16 8.7 7.2

States Interim EPA

Chile - Malaysia 91 12 10.1 5.4

Canada - Jordan 120 29 13.3 13.0

EFTA - Montenegro 206 52 22.9 23.3

Chile - Nicaragua (Chile - Central America) 227 48 25.3 21.5

Peru - Mexico 236 45 26.3 20.2

Mexico - Central America 244 56 27.1 25.1

EFTA - Hong Kong SAR, China 295 54 32.8 24.2

EFTA - Ukraine 302 54 33.6 24.2

Panama - Peru 311 65 34.6 29.1

Japan - Peru 324 51 36.0 22.9

US - Panama 328 71 36.5 31.8

Rep. of Korea - US 344 68 38.3 30.5

US - Colombia 355 76 39.5 34.1

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

32

Entry Agreement PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

into

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

Force

(%) (%)

(Year)

2013 Turkey - Mauritius 55 7 6.1 3.1

EU (28) Enlargement 102 31 11.3 13.9

Ukraine - Montenegro 133 22 14.8 9.9

Rep. of Korea - Tur key 140 42 15.6 18.8

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) - Singapore 184 27 20.5 12.1

Malaysia - Australia 291 65 32.4 29.1

Costa Rica - Singapore 294 57 32.7 25.6

Costa Rica - Peru 301 64 33.5 28.7

New Zealand - Taiwan, China 340 70 37.8 31.4

Canada - Panama 345 74 38.4 33.2

EU - Central America 395 88 43.9 39.5

EU - Colombia and Peru 399 89 44.4 39.9

2014 Chile - Vietnam 75 5 8.3 2.2

Iceland - China 180 32 20.0 14.3

Hong Kong SAR, China - Chile 189 27 21.0 12.1

Switzerland - China 210 40 23.4 17.9

Singapore - Taiwan, China 274 40 30.5 17.9

EFTA - Central America (Costa Rica and Panama) 356 74 39.6 33.2

Canada - Honduras 357 74 39.7 33.2

EU - Georgia 376 96 41.8 43.0

EU - Moldova 402 94 44.7 42.2

Rep. of Korea - Aus tralia 415 91 46.2 40.8

EU Ukraine 448 111 49.8 49.8

2015 Southern African Development Community 40 10 4.4 4.5

(SADC) - Accession of Seychelles

Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) - 114 38 12.7 17.0

Accession of Armenia

Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) - 117 40 13.0 17.9

Accession of Kyrgyz Republic

Mexico - Panama 169 24 18.8 10.8

Rep. of Korea - Vie tnam 186 18 20.7 8.1

Australia - China 202 39 22.5 17.5

EFTA - Bosnia and Herzegovina 206 48 22.9 21.5

Rep. of Korea - New Zealan d 240 37 26.7 16.6

Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) 243 63 27.0 28.3

China - Rep. of Korea 262 56 29.1 25.1

Japan - Australia 342 63 38.0 28.3

Canada - Rep. of Korea 415 93 46.2 41.7

2016 Pacic Alliance 110 27 12.2 12.1

Costa Rica - Colombia 172 28 19.1 12.6

Japan - Mongolia 210 42 23.4 18.8

Rep. of Korea - Col ombia 267 49 29.7 22.0

2017 Trans-Pacic Partnership 486 136 54.1 61.0

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

33

Annex Table O.A.2: Average number of provisions included and coverage ratio – by country

Number of

PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

Economy

Agreements

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

(%) (%)

Afghanistan 2 33.5 2.0 3.7 0.9

Albania 4 139.3 34.3 15.5 15.4

Algeria 2 71.5 18.5 8.0 8.3

Andorra 1 30.0 6.0 3.3 2.7

Angola 2 62.0 16.0 6.9 7.2

Antigua and Barbuda 1 152.0 36.0 16.9 16.1

Argentina 4 63.0 11.5 7.0 5.2

Armenia 9 77.9 22.2 8.7 10.0

Aruba 1 57.0 11.0 6.3 4.9

Australia 13 253.8 54.9 28.2 24.6

Austria 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Azerbaijan 5 51.8 12.0 5.8 5.4

Bahamas, T h e 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Bahrain 4 116.0 17.0 12.9 7.6

Bangladesh 5 35.4 3.4 3.9 1.5

Barbados 1 334.0 74.0 37.2 33.2

Belarus 7 88.4 24.4 9.8 11.0

Belgium 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Belize 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Benin 2 80.0 15.0 8.9 6.7

Bermuda 1 57.0 11.0 6.3 4.9

Bhutan 4 22.0 1.3 2.4 0.6

Bolivia 2 74.0 16.0 8.2 7.2

Bosnia and Herzegovina 4 160.0 44.0 17.8 19.7

Botswana 4 64.3 15.0 7.1 6.7

Brazil 3 81.7 15.3 9.1 6.9

Brunei Darussalam 9 217.3 44.8 24.2 20.1

Bulgaria 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Burkina Faso 2 80.0 15.0 8.9 6.7

Burundi 3 100.3 28.7 11.2 12.9

Cabo Verde 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Cambodia 6 168.8 30.2 18.8 13.5

Cameroon 2 82.5 16.0 9.2 7.2

Canada 12 300.3 64.4 33.4 28.9

Cayman Islands 1 57.0 11.0 6.3 4.9

Central African Republic 1 57.0 14.0 6.3 6.3

Chad 1 57.0 14.0 6.3 6.3

Chile 26 218.8 44.0 24.3 19.7

China 14 167.6 30.0 18.6 13.5

Colombia 12 243.8 50.4 27.1 22.6

Comoros 1 158.0 40.0 17.6 17.9

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

34

Number of

PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

Economy

Agreements

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

(%) (%)

Congo, Dem. Rep. 3 94.0 24.0 10.5 10.8

Congo, Rep. 1 57.0 14.0 6.3 6.3

Costa Rica 13 246.8 51.1 27.4 22.9

Côte d’Ivoire 3 79.3 13.7 8.8 6.1

Croatia 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Cuba 2 41.5 8.5 4.6 3.8

Cyprus 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Czech Republic 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Denmark 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Djibouti 1 158.0 40.0 17.6 17.9

Dominica 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Dominican Republic 3 181.0 39.7 20.1 17.8

Ecuador 2 74.0 16.0 8.2 7.2

Egypt, Arab Rep. 6 92.8 21.2 10.3 9.5

El Salvador 10 229.1 49.8 25.5 22.3

Equatorial Guinea 1 57.0 14.0 6.3 6.3

Eritrea 1 158.0 40.0 17.6 17.9

Estonia 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Ethiopia 1 158.0 40.0 17.6 17.9

Faroe Islands 4 52.8 12.3 5.9 5.5

Fiji 4 45.0 5.0 5.0 2.2

Finland 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

France 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

French Polynesia 1 57.0 11.0 6.3 4.9

Gabon 1 57.0 14.0 6.3 6.3

Gambia, T h e 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Georgia 8 86.4 21.6 9.6 9.7

Germany 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Ghana 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Greece 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Greenland 1 57.0 11.0 6.3 4.9

Grenada 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Guatemala 9 244.2 52.9 27.2 23.7

Guinea 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Guinea-Bissau 2 80.0 15.0 8.9 6.7

Guyana 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Haiti 1 152.0 36.0 16.9 16.1

Honduras 10 256.1 55.2 28.5 24.8

Hong Kong SAR, China 4 189.8 33.8 21.1 15.1

Hungary 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Iceland 29 189.1 37.4 21.0 16.8

India 16 92.1 14.4 10.2 6.5

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

35

Number of

PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

Economy

Agreements

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

(%) (%)

Indonesia 7 176.4 31.3 19.6 14.0

Iran, Islamic Rep. 1 46.0 8.0 5.1 3.6

Iraq 1 11.0 0.0 1.2 0.0

Ireland 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Israel 6 111.7 19.0 12.4 8.5

Italy 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Jamaica 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Japan 16 257.5 47.6 28.6 21.4

Jordan 8 89.9 19.4 10.0 8.7

Kazakhstan 10 73.7 19.6 8.2 8.8

Kenya 3 100.3 28.7 11.2 12.9

Kiribati 2 29.0 1.5 3.2 0.7

Korea, Rep. 17 267.5 50.4 29.8 22.6

Kuwait 3 75.7 10.0 8.4 4.5

Kyrgyz Republic 9 80.0 21.6 8.9 9.7

Lao PDR 9 124.3 21.7 13.8 9.7

Latvia 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Lebanon 3 82.0 22.7 9.1 10.2

Lesotho 4 64.3 15.0 7.1 6.7

Liberia 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Libya 2 84.5 20.0 9.4 9.0

Liechtenstein 27 194.0 38.3 21.6 17.2

Lithuania 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Luxembourg 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Macao SAR, China 1 60.0 14.0 6.7 6.3

Macedonia, FYR 5 116.6 32.0 13.0 14.3

Madagascar 4 90.0 22.0 10.0 9.9

Malawi 3 94.0 24.0 10.5 10.8

Malaysia 13 215.1 42.6 23.9 19.1

Maldives 3 26.7 1.3 3.0 0.6

Mali 2 80.0 15.0 8.9 6.7

Malta 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Marshall Islands 1 21.0 2.0 2.3 0.9

Mauritius 6 76.2 17.0 8.5 7.6

Mexico 14 223.9 47.3 24.9 21.2

Micronesia, Fed. Sts. 2 29.0 1.5 3.2 0.7

Moldova 5 140.2 36.6 15.6 16.4

Mongolia 1 210.0 42.0 23.4 18.8

Montenegro 5 151.4 41.4 16.8 18.6

Morocco 6 107.2 21.3 11.9 9.6

Mozambique 2 62.0 16.0 6.9 7.2

Myanmar 6 168.8 30.2 18.8 13.5

Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements

36

Number of

PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

Economy

Agreements

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive

(%) (%)

Namibia 4 64.3 15.0 7.1 6.7

Nauru 2 29.0 1.5 3.2 0.7

Nepal 4 24.8 1.0 2.8 0.4

Netherlands 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

New Caledonia 1 57.0 11.0 6.3 4.9

New Zealand 12 232.0 49.1 25.8 22.0

Nicaragua 8 259.4 59.1 28.9 26.5

Niger 2 80.0 15.0 8.9 6.7

Nigeria 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Norway 28 189.4 37.5 21.1 16.8

Oman 4 128.3 22.3 14.3 10.0

Pakistan 9 61.1 8.1 6.8 3.6

Panama 14 245.6 50.9 27.3 22.8

Papua New Guinea 5 39.8 4.6 4.4 2.1

Paraguay 3 81.7 15.3 9.1 6.9

Peru 16 285.2 60.3 31.7 27.0

Philippines 7 180.6 34.4 20.1 15.4

Poland 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Portugal 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Qatar 3 75.7 10.0 8.4 4.5

Romania 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Russian Federation 12 67.9 19.1 7.6 8.6

Rwanda 3 100.3 28.7 11.2 12.9

Samoa 2 29.0 1.5 3.2 0.7

San Marino 2 240.0 61.0 26.7 27.4

Saudi Arabia 3 75.7 10.0 8.4 4.5

Senegal 2 80.0 15.0 8.9 6.7

Serbia 5 126.8 32.4 14.1 14.5

Seychelles 4 90.0 22.0 10.0 9.9

Sierra Leone 1 99.0 18.0 11.0 8.1

Singapore 22 238.1 45.3 26.5 20.3

Slovak Republic 37 170.1 39.7 18.9 17.8

Slovenia 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Solomon Islands 3 28.0 2.0 3.1 0.9

South Africa 5 77.0 18.6 8.6 8.3

South Sudan 1 158.0 40.0 17.6 17.9

Spain 37 165.4 39.7 18.9 17.8

Sri Lanka 7 37.0 4.6 4.1 2.0

St. Kitts and Nevis 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

St. Lucia 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

St. V i n c e n t a n d t h e G r e n a d i n e s 2 243.0 55.0 27.0 24.7

Sudan 1 11.0 0.0 1.2 0.0

The Evolution of Deep Trade Agreements

37

Number of

PROVISIONS COVERAGE RATIO

Economy

Agreements

Overall Substantive Overall Substantive