International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1237

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

Original Article

Standard Precaution Practices among Doctors and Nurses in the

University College Hospital Ibadan

Akinade, Tolulope Abisola

Department of Social Work, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Gandonu Micheal Babatunde

Department of Guidance & Counselling, Lagos State University, Nigeria

Abstract

This study examined practice of standard precautions among health workers in the University College Hospital

Ibadan. The research adopted a cross-sectional survey design using quantitative research methods.The study was

conducted within the premises of the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan. In this study, the reference

population included doctors and nurses in UCH, from which a representative sample size of 308 participants

was obtained. Multistage sampling technique was used to select participants for the study. Data collection was

conducted using a structured, pre-coded, self-administered questionnaire. Three hypotheses were formulated and

tested using t-test and multiple regression analysis. Majority of the HCWs reported as they ‘always’ use gloves

and gown during procedures that needs this protective equipment. But only 10.4% of them reported that they

‘always’ wore Mask and Goggle. Major reasons for low practice levels included incidents of inadequate

supplies, carelessness, discomfort with use and discomfort among patients. Further results showed that there was

no significant difference in practice of standard precautions between nurses and doctors [t(292)=-.352; p>.05].

There was also no significant difference in practice of standard precautions between respondents who reported

more positive attitude towards standard precautions and their counterparts who reported less positive attitude

towards standard precautions [t(292)=.084; p>.05]. Age (β=-.041; p>.05) and marital status (β=-.003; p>.05)

emerged as insignificant predictors of standard precautions practice, work experience (β=.103; p<.05) emerged

as a significant positive predictor of standard precautions practice among nurses and doctors in UCH. Suitable

recommendations were provided in line with the study outcomes.

Keywords: Standard precaution practice, Doctor, Nurse, University College Hospital

Introduction

Health care workers (HCWs) such as medical

doctors, nurses, laboratory staff and attendants

who work in health care settings are frequently

exposed to infectious diseases during their work.

Infections acquired in the health care setting are

major causes of anxiety for HCWs. These

infections include diseases like hepatitis B virus

(HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human

immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and other blood

borne diseases (Hosoglu et al., 2011). Globally,

it has been estimated that the annual proportions

of HCWs exposed to blood-borne pathogens

were 2.6% for HCV, 5.9% for HBV, and 0.5%

for HIV (Cutter & Jordan 2012). In Nigeria,

documented cases of HIV infection following

occupational exposure among HCWs has

continually increased to an annual average of

1000 cases since the first recorded case in 1984

(Okechukwu et al., 2012). The fact that patients’

blood and other body fluids are potentially

hazardous to HCWs, the safety of HCWs at their

work place has become a great concern for health

professionals all over the world (Izegbu, Amole

& Ajayi, 2006).

Studies have shown that HCWs are at risk of

being infected with blood borne pathogens due to

their occupational exposure to blood and other

body fluids (BBF) (Agaba et al., 2012;

Omiepirisa, 2012; Okechukwu et al., 2012;;

Prüss-Üstün et al., 2005). It has been estimated

that HCWs’ exposure to blood-borne pathogens

contributes annually to about 16,000 HCV

infections and 66,000 HBV infections among

HCWs worldwide (Prüss-Üstün et al., 2005) and

90% of these infections occurred in low-income

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1238

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

countries (Kermode et al., 2005). In general, the

most common route of exposure is through

sharps; lancets, broken glass, needles and other

sharps instruments, while exposures from needle

stick injuries has been reported as the most

common of all (Omiepirisa, 2012). However, it

should be noted that many studies have

demonstrated that the incidence of needle stick

injuries are poorly reported globally and more so

in developing countries (Honda et al., 2011;

Bolarinwa et al., 2011; Chalya et al., 2015;

Voide et al., 2012; Amira et al., 2014). The

reasons for non-report of these incidents range

from perceived low risk of infection transmission

following exposure, to perceived lack of time

(Bolarinwa et al., 2011; Chalya et al., 2015;

Voide C et al., 2012; Amira et al., 2014).

The earliest attempt to reduce the incidence of

hospital-acquired infections among Health care

workers was in 1877, when the first

recommendation for isolation precautions was

published in the United States for patients with

known infectious diseases (Lynch, 1949; CDC,

1996). Several recommendations, guidelines and

protocols have since been published by the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO)

and the United States Occupational Safety and

Health Administration (OSHA); most of which

were about protection against specific diseases or

during a particular procedure. Countries adopt

recommendations and guidelines from these

bodies to develop their country-specific policies

and guidelines.

In 1983, the CDC published the Universal Blood

and Body Fluid precautions, simply called the

‘Universal Precautions’ (CDC, 1985; Farlex,

2012). These precautions were meant for patients

known to have or sSPected to have an infectious

blood-borne pathogen and were also meant to

prevent parenteral, mucous membrane and non-

intact skin exposures to blood-borne pathogens

by Health care workers (CDC, 1985). They apply

to blood, semen, vaginal secretions, deep body

fluids, body fluids with visible blood, but not to

faeces, nasal secretions, sputum, sweat, urine,

tears and vomitus; unless they contain visible

blood (CDC, 1983). In 1991, OSHA published

its Occupational Exposure to Blood-borne

Pathogen Standards, where they incorporated the

Universal Precautions and added requirements

for employers of Health care workers to provide

engineering controls, protective barriers and

devices, immunization against hepatitis for

Health care workers and training of Health care

workers on the Universal Precautions (Farlex,

2012).

However, in 1996, the CDC published new

guidelines known as the Standard Precautions

sometimes, also referred to as the ‘Safety

Precautions’ (SP) (Farlex, 2012). It includes the

Universal Precautions as well as other

recommendations for care of patients irrespective

of their diagnosis or presumed infection status.

The SP apply to blood, all body fluids, secretions

and excretions except sweat, with or without the

presence of visible blood (Garner, 1996; CDC,

2011). It includes: hand hygiene, use of personal

protective equipment (e.g., gloves, facemasks),

respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette, safe

injection practices and safe handling of

potentially contaminated equipment or surfaces

in the patient environment (CDC, 2011),

decontamination and disinfection of instruments,

maintenance of sanitary workplace and safe

waste disposal; which are the core principles of

the SP (USAID, 2000). Under each of these

principles are the recommended activities or

‘dos’ and ‘don’t’ expected of Health care

workers in order to achieve adherence to the

principles. These recommended activities are the

SP practices.

Currently the National Agency for the Control of

AIDS (NACA) in collaboration with the

Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) is

saddled with the responsibility of developing,

reviewing and disseminating guidelines and

policies related to safety practices among Health

care workers in health care settings in the

country (NACA, 2010). Guidelines and policies

are being periodically reviewed and disseminated

while implementation at the State and Local

Government levels are meant to be monitored by

the State and Local Government arms of the

FMOH and NACA (NACA, 2010; NACA,

2014). Some of the specific guidelines developed

to ensure optimal practise of the SP in health care

settings in Nigeria includes the following;

National policy on universal safety precaution,

Guidelines on TB infection control, TB infection

control plan, Policy and Guidelines on safety of

blood and blood products, Health care waste

management protocol, National protocol of post

exposure prophylaxis and Health workers’

injection safety guidelines (NACA, 2010).

However, no report or document was found

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1239

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

about the efforts of the FMOH and NACA to

enforce the implementation of these guidelines

and policies at all levels.

Statement of Problem: The practice of standard

precautions is being widely promoted to protect

Health care workers from occupational exposure

to body fluids and consequent risk of infection

with blood-borne pathogens. Health care workers

are potentially exposed to blood-borne and other

infections through contact with body fluids while

performing their duties. Health care workers

frequently provide care to patients whose HBV,

HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) status is

unknown, and individuals may be asymptomatic

for months to years while being infectious. The

occupational health of the health care workforce

of about 35 million people globally, representing

about 12% of the working population, has been

neglected. About three million Health care

workers worldwide receive percutaneous

exposure to blood-borne pathogens each year.

These injuries may result in 15,000 HCV, 70,000

HBV and 500 HIV infections, and more than

90% of these infections occur in developing

countries. Worldwide, about 40% of HBV and

HCV infections and 2.5% of HIV infections in

Health care workers are attributable to

occupational sharps exposures, which are mainly

preventable (WHO, 2016)

The Occupational Safety and Health

Administration estimates that 5.6 million Health

care workers worldwide, who handle sharp

devices, are at risk of occupational exposure to

blood-borne pathogens. Needle stick injuries

were shown to be the commonest (75.6%)

mechanism for occupational exposure in a

Nigerian teaching hospital. These injuries are

usually under-reported for so many reasons,

which include stigma that could be associated

with an eventual infection with HIV in the

affected HCW. There is no immunization for

HIV and HCV, thus the most effective

prevention is through regular practice of the

standard precautions.

Compliance to standard precautions is low in

public secondary health facilities, especially in

resource-limited settings, thus exposing Health

care workers to the risk of infection.

Occupational safety of Health care workers is

often neglected in low-income countries in spite

of the greater risk of infection due to higher

disease prevalence, low level awareness of the

risks associated with occupational exposure to

blood, inadequate supply of personal protective

equipment (PPE), and limited organizational

support for safe practices. Blood and other body

fluids from patients are becoming increasingly

hazardous to those who provide care for them.

There is therefore a need for adequate measures

to ensure compliance to standard precautions and

reduce the risk of infection among Health care

workers.

Research Hypotheses

In line with the study objectives, the following

research hypotheses are formulated for testing.

Hi: There will be significant difference in

practice of standard precautions across health

care workers in the university college hospital

Ibadan.

Hi: Attitude towards standard precautions

will have a significant influence on practice of

standard precautions among health care workers

in the university college hospital Ibadan

Hi: Age, years of experience and marital

status will have significant joint and independent

influence on practice of standard precautions

among health care workers in the university

college hospital Ibadan

Research Methods

Design and Settings: The research adopted a

cross-sectional survey design using quantitative

research methods to examine practice of standard

precautions among health workers in the

University College Hospital Ibadan. The study

was conducted within the premises of the

University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan. The

University College Hospital (UCH) is

strategically located in Ibadan North LGA. The

physical development of the Hospital

commenced in 1953 in its present site and was

formally commissioned after completion on 20

November 1957. The Hospital, at inception in

1957, prior to the Act of Parliament, had two

clinical Departments (Medicine and Surgery).

However, the Hospital has evolved to

accommodate about 65 Departments. The

Hospital, though a tertiary healthcare facility,

still caters for a lot of the primary and secondary

healthcare burden. The patients turn out in the

Emergency Department of the Hospital averages

6500 annually and about 150,000 new patients

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1240

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

are seen in the various out-patient clinics every

year.

Population and Study Sample: In this study,

the reference population included doctors and

nurses in University College Hospital (UCH),

Ibadan. A representative sample size of 308

participants was obtained based on an estimated

total number of nurses and doctors in the

University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan. The

hospital has a staff strength of over 3000 which

comprise at least 600 doctors and 1000 nurses

(Iyun, 2016). The sample size was obtained using

Slovin sample size determination formula;

n = N / (1+Ne

2

)

where; n=sample size

N=population size

e=error margin

n = 1600/(1 + 1600*.05

2

)

= 1600/5.2

=307.7

= 308 healthcare workers (doctors and nurses)

Sampling Technique: A multistage sampling

technique was used to select participants for the

study. In the first stage, a stratified random

sampling was adopted. This involved creating

limited strata made up of a minimum of 10

units/departments each within the UCH. In the

second stage simple random sampling via the

ballot technique was used to select 5

participating units/departments from each

stratum. The third stage involved the use of

purposive sampling in which nurses and doctors

from each of the participating units/departments

were selected. Factors considered included

eligibility and willingness to participate in the

study

Instrumentation: Data collection was conducted

using a structured, pre-coded, self-administered

questionnaire. Questionnaires are documents

containing questions and other items designed to

elicit information appropriate to specific research

and analysis. The questionnaire is made up of

four main sections, namely, biographical data

(section A), attitude towards standard

precautions (section B), practice of standard

precautions (section C), and factors influencing

compliance of standard precautions (section D).

The answer categories were mutually exclusive

and special instructions were provided where

necessary for easy understanding. A covering

letter also accompanied the questionnaire, which

introduced the study and its purpose to

participants and requested them to participate. It

also provided instructions on how to complete

the questionnaire. Participants were not

requested to write their name or any other form

of identity in the questionnaire in order to ensure

that their identity could not be linked with their

individual responses.

In order to measure the extent to which the

survey instruments have been able to achieve

their aims, the process of content validity will be

employed by cross examination and verification.

The knowledge gained from other investigations,

literature review, theoretical framework and

research methods was used for an initial face

validation while expert assessment from the

project supervisor provided content validatation

for the instrument. Consequently, a number of

items in the questionnaire were subject to

amendment. A pilot study was carried out among

a sample with similar charateristics to the study

population. Outcomes form the pilot study were

subjected to a split half reliability test in order to

obtain the reliability coefficient for the

instrument. Reliability coefficiants obtained were

greater than .70 and deemed adequate for the

study.

Data Collection Method: The researcher,

accompanied by research assistants, visited

participating units/departments within the

University College Hospital in Ibadan. Upon

completion of the administrative protocol, the

purpose of the study was explained to the

management of the units/department. In order to

ensure effective administration of the instrument,

a contact person (nurse/doctor) within each

unit/department was implored to distribute copies

of the questionnaire to all available colleagues

within the unit/department.

The contact persons were encouraged to ask

clarification questions. Printed instructions on

how to complete the instrument was provided on

each questionnaire, in which participants were

assured that there are no right or wrong answers

and a strict measure of confidentiality would be

ensured.

Participants were expected to fill the

questionnaires at their leisure time and return the

completed questionnaires to the contact person at

their earliest possible convenience. Data obtained

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1241

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

from the study were input and coded into an

SPSS package for data analysis. Both descriptive

and inferential statistics were employed in the

data analysis. These included the use of

percentage frequency, t-test and multiple

regression analysis.

Results

Data was analysed using both descriptive and

inferential statistics. Percentage frequency

distribution tables, t-test and multiple regression

analysis were adopted as analytical techniques.

Results are presented in the following sections

.

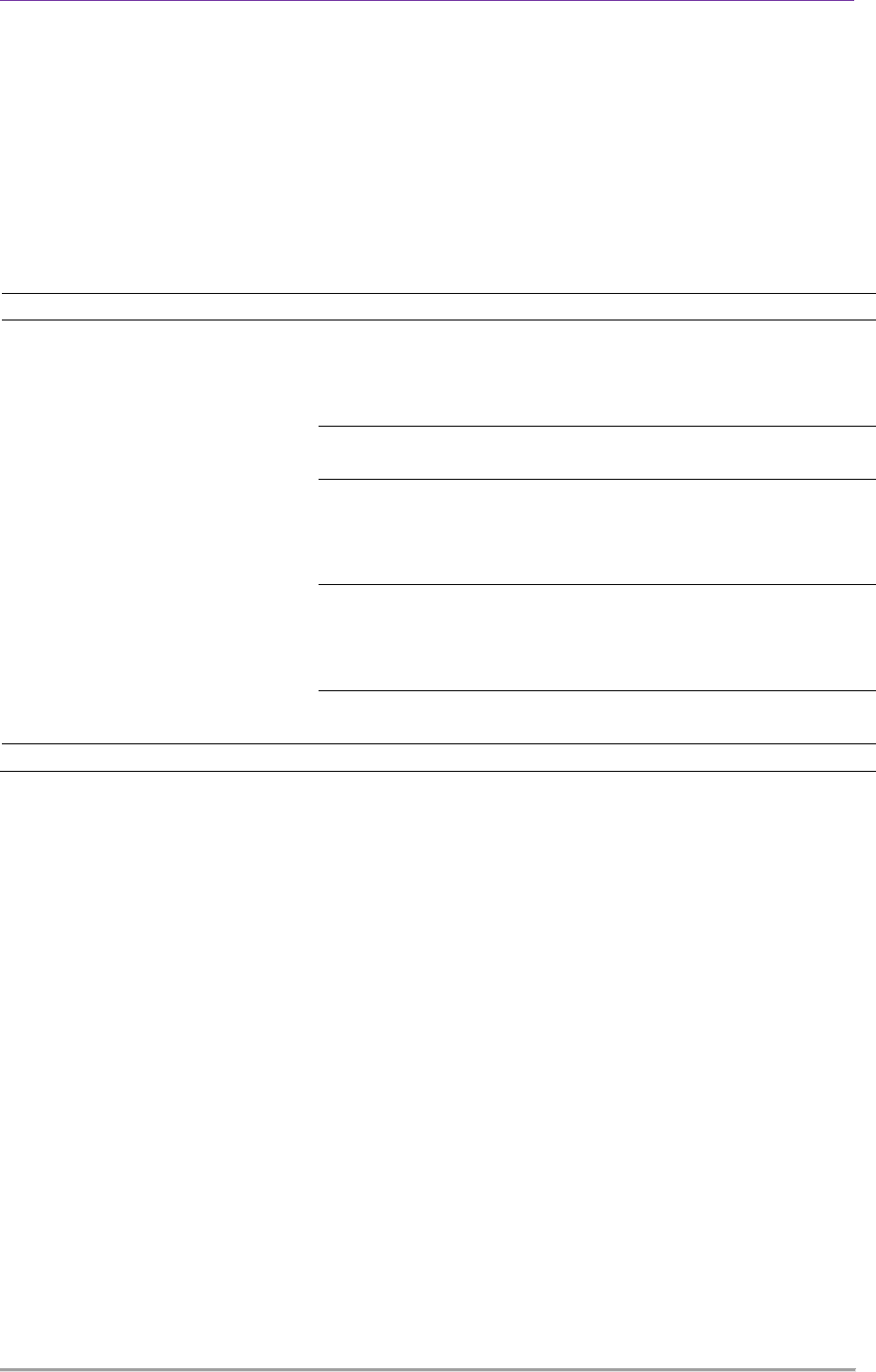

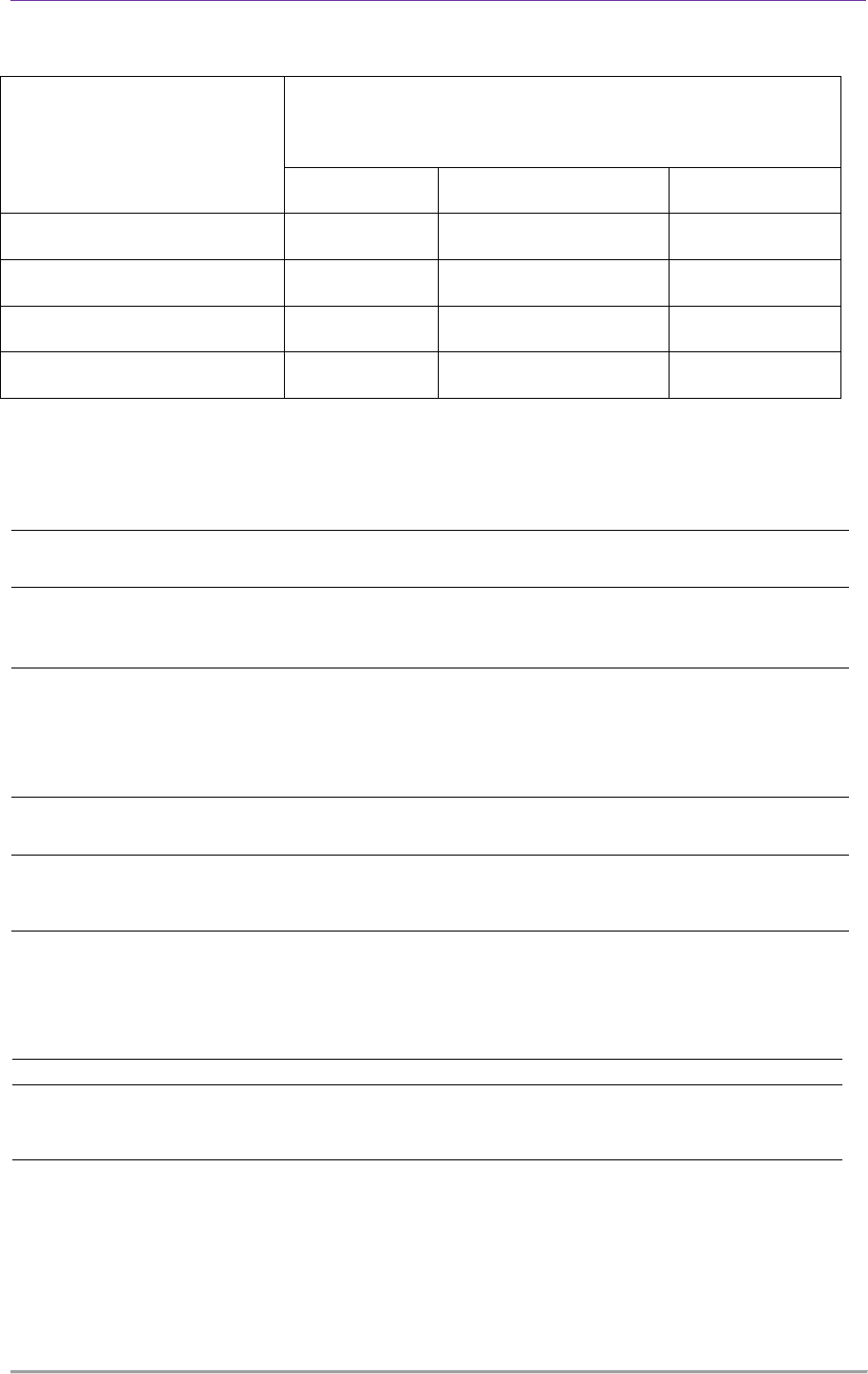

Table 1: Distribution of Respondents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Frequency Percent

Age

20-30years 10 3.4

31-40years 101 34.2

41-50years 117 39.7

51-60years 67 22.7

Gender

Male 107 37.3

Female 188 62.7

Marital Status

Single 107 36.3

Married 136 46.1

Divorced 34 11.5

Widowed 18 6.1

Work Experience

1-5years 52 17.6

6-10years 85 28.8

11-15years 102 34.6

16years or more 56 19.0

Designation

Nurse 179 60.7

Doctor 116 39.3

Total 295 100.0

Results from Table 1 show that majority

(74.9%) of the respondents were between

ages 31-50 years. The mean age of the

respondents was 37.6 years with a standard

deviation of 11.2. Their gender distribution

showed that 62.7% of the respondents were

female while the remaining 37.3% were

male. The disparity in gender distribution

can be alluded to the fact that nursing is a

female dominated profession. Further results

show that 36.3% of the respondents were

single while 46.1% of them were married.

the remaining were either divorced (11.5%)

or widowed (6.1%). In terms of their work

experience, 17.6% of the respondents had

work experience ranging from 1-5 years,

28.8% of the respondents had work

experience ranging from 6-10 years, 34.6%

of the respondents had work experience

ranging from 11-15 years, while 19.0% of

the respondents had work experience of 16

years or more.

From 295 HCWs only 61.5% always practice

hand washing after any direct contact with

patient, 34.4% often practice standard

precautions and the remaining 24.1% seldom

practice standard precautions. As shown in

Table 4.2, majority of the HCWs reported as

they ‘always’ use gloves and gown during

procedures that needs this protective

equipment. But only 10.4% of them reported

that they ‘always’ wore Mask and Goggle.

This study further assessed the major reason

for poor practice and most of 84.4% of the

respondents said that water and soap were

not available at patient care areas. As shown

in Table 3, the major reasons for poor

practice of personal protective equipment

like glove, gown and goggle, was shortage of

supply. Furthermore, 60.2% of the HCWs

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1242

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

reported that they exposed to splash of blood

or body fluid on their mucus membrane (i.e.

eye, nose or mouth) in the last one year.

After giving injection or drawing blood from

patients 82.4% of the HCWs reported not

recapping used needles, 17.0% of them had

recapping and 0.6% of them practiced

bending needles by hand. Regarding to

exposure to sharp or needle stick injury 22.2

% of the HCWs exposed in the last one-year.

Carelessness was the major reason stated by

HCWs for recapping needles (54.1%)

Discarding used needles and other sharps in

a safety box was practiced among 79.5% of

HCWs.

Hypotheses Testing: In line with the

objectives of the study, four hypotheses were

formulated and tested using appropriate

statistical techniques. Results are presented

in the following sections

Hypothesis One: There will be significant

difference in practice of standard precautions

across health care workers in the university

college hospital Ibadan. This hypothesis was

tested using t-test for independent measures.

Results are presented in Table 4.

Results from Table 4.4 show that there was

no significant difference in practice of

standard precautions between nurses and

doctors [t(292)=-.352; p>.05]. The results

imply that both nurses and doctors in UCH

exhibit similar practice levels of standard

precautions. The hypothesis stated is

therefore rejected.

Hypothesis Two: Attitude towards standard

precautions will have a significant influence

on practice of standard precautions among

health care workers in the university college

hospital Ibadan. This hypothesis was tested

using t-test for independent measures.

Results are presented in Table 5.

Results from Table 5 show that there was no

significant difference in practice of standard

precautions between respondents who

reported more positive attitude towards

standard precautions and their counterparts

who reported less positive attitude towards

standard precautions [t(292)=.084; p>.05].

The results imply that attitude towards

standard precaution had no significant

influence on practice levels of standard

precaution among nurses and doctors in

UCH. The hypothesis stated is therefore

rejected.

Hypothesis Three: Age, years of experience

and marital status will have significant joint

and independent influence on practice of

standard precautions among health care

workers in the university college hospital

Ibadan. This hypothesis was tested using

multiple regression analysis. Results are

presented in Table 6

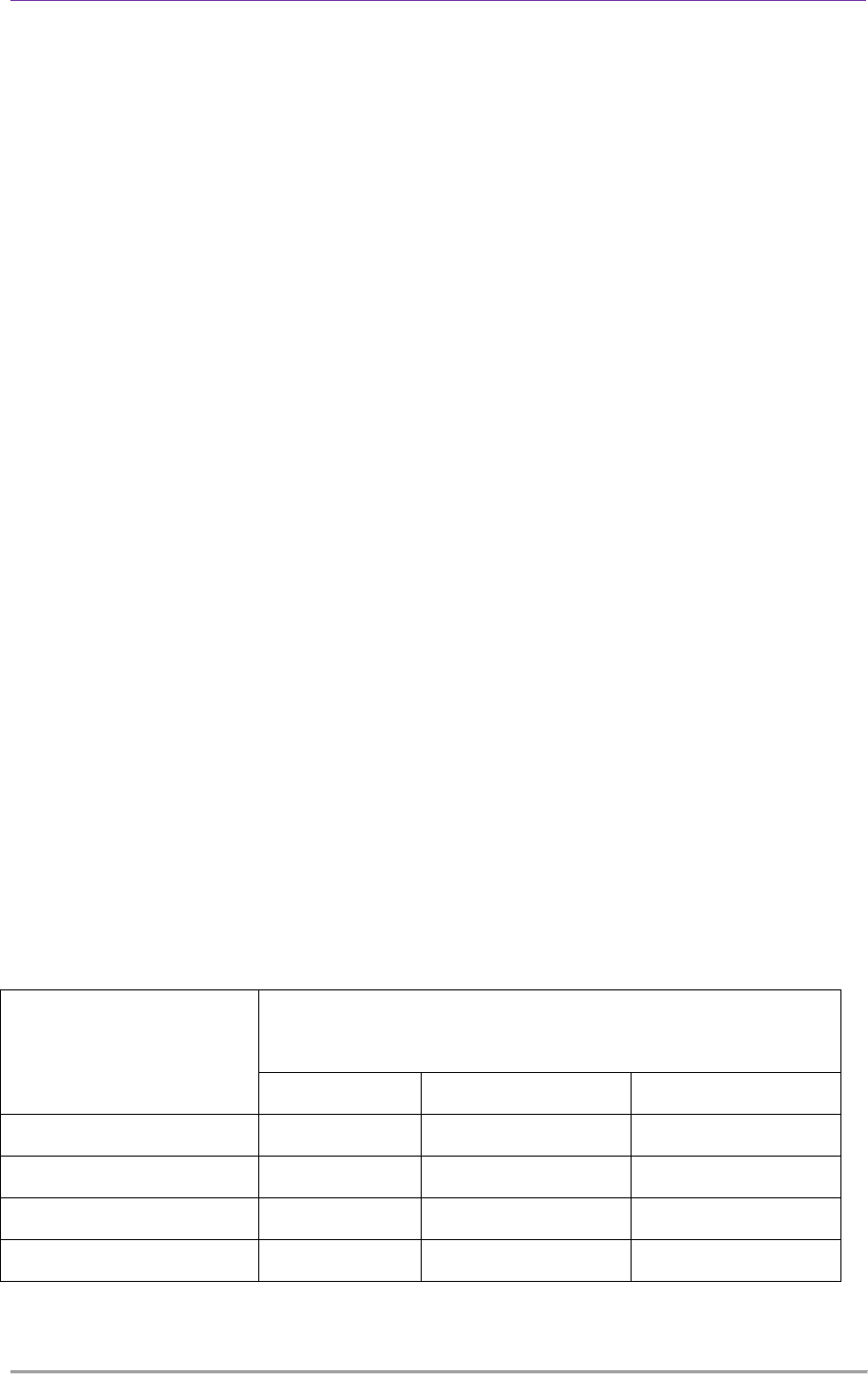

Table 2: Standard Precaution Practice

Standard Precaution

Practice

Type of Personal Protective Equipment

N=295

Glove Gown/Plastic Apron Mask and Goggle

Always 86.7 89.9 10.3

Often 11.6 6.8 20.9

Seldom 1.7 3.1 48.9

Never 0 0.1 19.9

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1243

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

Table 3: Reasons for Poor Practice Level

Reasons for Poor Practice

Level

Type of Personal Protective Equipment

N=295

Glove Gown/Plastic Apron Mask/Goggle

Shortage of Supply 15.6 71.4 84.5

Carelessness 15.6 0 2.3

Discomfort with Use 39.1 24.5 11.6

Discomfort among Patients 29.7 6.1 1.6

Table 4: Summary of t-test showing difference in standard precaution practices

between Nurses and Doctors in UCH

Designation

N Mean Std.

Deviation

df t sig

Standard

Precaution

Practice

Nurse 179 90.1732

9.79269

292 -.352 .725

Doctor 115 90.6000

10.68513

Table 5: Summary of t-test showing influence of attitude towards standard precaution on

practice of standard precaution among nurses and doctors in UCH

Standard Precaution

Attitude

N Mean Std. Dev. df t Sig

Standard

Precaution

Practice

More positive 158

90.3861

8.74969

292 .084 .933

Less positive 136

90.2868

11.57194

Table 6: Summary of multiple regression showing influence of demographics on practice of

standard precaution among nurses and doctors in UCH

R

2

F Sig Beta t Sig.

Age

-.041 -.694 .488

Marital Status .009 .165 .920 -.003 -.050 .960

Work Experience .103 .142 .047

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1244

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

Results from Table 6 show that age, work

experience and marital status did not have

significant joint influence on practice levels

of standard precautions among nurses and

doctors in UCH [F(3, 290)=.165; p>.05].

However, while age (β=-.041; p>.05) and

marital status (β=-.003; p>.05) emerged as

insignificant predictors of standard

precautions practice, work experience

(β=.103; p<.05) emerged as a significant

positive predictor of standard precautions

practice among nurses and doctors in UCH.

The hypothesis stated is therefore partially

accepted due to the significant influence of

work experience on standard precautions

practice.

Discussion

The first hypothesis which stated that there

will be significant difference in practice of

standard precautions across health care

workers in the university college hospital

Ibadan was not supported. The results imply

that both nurses and doctors in UCH

exhibited similar high practice levels of

standard precautions. The results may be

justified by the fact that training on standard

precautions is paramount for the profession

of nurses and doctors. Therefore, from a

professional point of view, every nurse or

doctor is expected to exhibit high practice

levels of standard precautions. Another

reason for the seemingly high levels of

standard precaution practice among the

respondents may also have emanated from

the effect of social desirability responses

from the study participants.

Supporting these findings, Arinze-Onyia,

Ndu, Aguwa, Modebe and Nwamoh (2018)

assessed the knowledge and practices of SP

among HCWs at the University of Nigeria

Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu

State and found that those who were trained

on SP (70.8%) and PPE (69.7) were

significantly more likely to use PPEs. A

related study by Sadoh, Fawole, Sadoh,

Oladimeji & Sotiloye (2006) practice levels

of standard precautions was not comprised

by majority of the nurses and doctors. Luo et

al. (2010) investigated significant

compliance with SPs by nurses and found

that less than 5% of the 1,444 nurses did not

comply with SP. Similarly,

Maharaj et al.

(2012) that less than 7% of doctors perceived

themselves as non-compliant to the practice of

SPs. However, i

n contrast to the result

obtained in this study, Kolude, Omokhodion

& Owoaje (2004) found that practice of

standard precaution was highest among

surgical and medical residents than nurses.

The second hypothesis which stated that

attitude towards standard precautions will

have a significant influence on practice of

standard precautions among health care

workers in the university college hospital

Ibadan was not supported. The results imply

that attitude towards standard precaution had

no significant influence on practice levels of

standard precaution among nurses and

doctors in UCH. This outcome underscores

theoretical tenets that attitude does not

always predict practice. In the case of this

study, the practice of standard precautions

among majority of the respondents is more

of a professional ethic than a personal

disposition. Therefore, even though the

respondents could be grouped as having

more or less favorable disposition towards

standard precaution, their obligation to

practice these standard precautions was

unwavering.

This outcome is similar to results obtained

by Odusanya (2003) who conducted a study

on attitude and compliance with universal

precautions amongst health workers at an

emergency medical service in Lagos,

Nigeria, and found that their attitude towards

universal compliance did not translate into

safe work practices. A similar study by

Bamigboye and Adesanya (2006) it was

observed that doctor felt that the use of

safety precautions in the medical practice

could not be compromised in an era of

communicable diseases, irrespective of the

personal dispositions.

In another study Alam (2002) examined

knowledge, attitude and practices among

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1245

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

health care workers (nurses and paramedical

staff) and found a high practice level of

standard safety precautions among them.

Efstathiou et al. (2011) explored how

hospital nurses’ shared experiences affected

by behaviour on compliance with the

practice of SPs (100%) using a focus group.

They found that fear of contracting diseases

was a more driving force towards

compliance than attitude towards safety. On

the other hand, Jawaid et al. (2009) found

that 34% of the doctors in their study often

judged the severity as a basis for strict

adherence to safety precautions; which is

indicative of a significant influence of

attitude on practice levels.

The third hypothesis which stated that age,

years of experience and marital status will

have significant joint and independent

influence on practice of standard precautions

among health care workers in the university

college hospital Ibadan was partially

accepted due to the significant influence of

work experience on standard precautions

practice. In justifying the results obtained, it

may be emphasized that medical health

workers who have more years of experience

on the job are more likely to have garnered

an accumulation of first-hand experiences or

cases that reinforce the need to adhere

strictly to all standard precautions.

Moreover, having more years of experience

on the job presents health care workers with

more opportunities for additional on-the-job

training on standard precautions and safety

measures in medical practice.

Corroborating results obtained in this study,

another study done in Ethiopia showed that,

nurses with less experience were at a higher

risk of exposure to infectious diseases and

had weak universal precautions practice

(Reda, Vandeweerd, Syre & Egata, 2009).

Similarly, Luo et al., (2010) found that

longer duration of professional experience

has been shown to be associated with

improved compliance with standard

precautions among health workers.

Abdulraheem et al. (2012) also found that

healthcare workers with ten years and above

working experience had a high level of

awareness of universal precautions than

those with below five years. Furthermore,

Abubakar et al. (2014), in their study of

nurses in Gombe state revealed that years of

experience has influence on practice of

standard precaution.

Recommendations: Based on the outcomes

of this study, health organisations must

educate their staff to increase the level of

awareness toward standard precautions, and

increase the quality of patient care.

Moreover, if the awareness of HCWs is

improved, it will hopefully reduce the

existing negative attitude toward the

implementation of standard precautions, as

the level of knowledge and compliance to

standard precautions are reciprocally related.

Looking to the future, organisations need to

involve employees in the establishment of

policies, and consider having a mandatory

program for HCWs with time allowed to

accomplish it effectively. Increasing HCWs’

awareness and acknowledgment of risk

factors in their work place, and the impact of

their poor practice on both themselves and

on patients is significant, and especially if

they do not follow the guidelines. This

change can be achieved through

communication, which is another important

aspect that impacts HCWs’ compliance.

Thus, having regular meetings with all

HCWs would reduce related practical issues,

and highlight positive perceptions that would

eventually increase and motivate HCWs to

follow the guidelines. Involving staff in the

policy process is also recommended, as

employee engagement is beneficial in

motivating staff to follow the guidelines.

However all of those factors depend mainly

on the organisation, as organisations have to

provide the protective tools for their

employees, and make sure the tools are

suitable, effective and fit for purpose,

furthermore they must be comfortable and

easy to use. Therefore, the responsibility

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1246

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

rests not only on HCWs as employees, but

also on managers and leaders; part of their

duty is to keep updating and evaluating the

HCWs’ knowledge of standard precautions.

Hopefully, after applying these

recommendations, the HCWs’ compliance

and knowledge levels will be raised. This

will result in improved quality of patient

care.

References

Abdulraheem I, Amodu M, Saka M, Bolarinwa O and

Uthman M (2012). Knowledge, awareness and

compliance with standard precautions among

health workers in north eastern Nigeria. J

Community Med Health Edu. 2 (3): 1-5.

Adinma ED, Ezeama C, Adinma JIB, Asuzu MC.

(2009) Knowledge and practice of universal

precautions against blood borne pathogens

amongst house officers and nurses in tertiary

health institutions in Southeast Nigeria. Nigerian

Journal of Clinical Practice 12: 398–402.

Agaba P, Agaba E, Ocheke A, Daniyam C, Akanbi M,

and Okeke E (2012). Awareness and knowledge of

human immunodeficiency virus post exposure

prophylaxis among Nigerian Family Physicians:

Niger Med J. 53(3); 155–160

Amira C and Awobusuyi J (2014). Needle-stick injury

among health care workers in hemodialysis units

in Nigeria: a multi-center study. Int J Occup

Environ. 5:1-8.

Arinze-Onyia, S.U., Ndu, A.C., Aguwa, E.N.,

Modebe, I., & Nwamoh U.N. (2018) Knowledge

and practice of standard precautions by health-care

workers in a tertiary health institution in Enugu,

Nigeria. Nigerian journal of clinical practice 21

(2), 149-155

Bamigboye, AP, Adesanya, AT. (2006) Knowledge

and practice of UP among qualifying medical and

nursing students: A case of Obafemi Awolowo

University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife.

Research Journal of Medicine and Medical

Sciences, 1(3): 112–116.

Bolarinwa O, Asowande A and Akintimi C (2011).

Needle stick injury pattern among health care

workers in primary health care facilities in Ilorin,

Nigeria. Academic Research international. 1(3):

419-427.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (1983).

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Precautions for health care workers and allied

professionals. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

32(34): 450-451.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (1985).

Recommendation for protection against viral

hepatitis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 35(22):

313- 324.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (1996).

Guidelines for isolation precautions in hospitals.

(Online). Available:

https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/prevguid/p000041

9/p0000419.asp

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2011).

Infection control prevention plan, (Online).

Available:

http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/settings/outpatient/basic-

infection-control-prevention-plan-

2011/fundamental-of-infection-prevention.html.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2013).

Infection control; Division of Oral health (online).

Available:

https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/fa

q/bloodborne_exposures.htm

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2013).

Occupational HIV transmission and prevention

among health care workers, (Online). Available:

www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/other,occupational.html.

(Downloaded: 10/07/13 10:47pm).

Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention (1993).

HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Available:

www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance92pdf.

Chalya P, Seni J, Mushi M, Mirambo M, Jaka H,

Rambau P, Mabula J, Kapesa A, Ngallaba S,

Massinde A and Kalluvya S (2015). Needle-stick

injuries and splash exposures among health-care

workers at a tertiary care hospital in north-western

Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research.

17(2):1-15.

Cutter J, & Jordan S. (2012) Inter-professional

differences in compliance with standard

precautions in operating theatres: a multi-site,

mixed methods study. International Journal of

Nursing Studies 49: 953–968.

Efstathiou, Georgios & Papastavrou, Evridiki &

Raftopoulos, Vasilios & Merkouris, Anastasios.

(2011). Compliance of Cypriot nurses with

Standard Precautions to avoid exposure to

pathogens. Nursing & health sciences. 13. 53-9.

10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00576.x.

Honda M, Chompikul J, Rattanapan C, Wood G and

Klungboonkrong S (2011). Sharp’s injuries among

nurses in a Thai regional hospital. Prevalence and

risk factors. Intl J Occupationa Environmental

Med. 2(4): 215-223.

Hosoglu S, Akalin S, Sunbul M, Otkun M, Ozturk R.

(2011) Healthcare workers’ compliance with

universal precautions in Turkey. Medical

Hypotheses 77: 1079–1082.

Izegbu M, Amole O, Ajayi G. (2006) Attitudes,

perception and practice of workers in laboratories

in the two colleges of medicine and their teaching

hospitals in Lagos State, Nigeria as regards

universal precaution measures. Biomedical

Research 17: 49–54.

Kermode M, Jolley D, Langkham B, Thomas M and

Crofts N (2005). Occupational exposure to blood

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2021 Volume 14| Issue 2| Page 1247

www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org

and risk of blood borne virus infection among

health care workers in rural North Indian settings.

Am J Infect Control. 33:34–41

Kolude OO, Owoaje ET, Omokhodion F. (2004)

Knowledge and compliance with UP among

doctors in a tertiary hospital. Proceedings of the

Annual General and Scientific meeting of the

West African College of Physicians. Ibadan

2004:27.

Luo Y, He G, Zhou J, Luo Y. (2010) Factors

impacting compliance with standard precautions in

nursing, China. International Journal of Infectious

Diseases 14: e1106–14.

National Agency for the Control of AIDS (2010).

National HIV/AIDS strategic plan 2010-2015.

(Online), Available:

http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/defau

lt/files/country_docs/Nigeria/hiv_plan_nigeria.pdf.

National Agency for the Control of AIDS (2014).

National HIV/AIDS Prevention plan 2014-2015.

(Online), Available:

http://sbccvch.naca.gov.ng/sites/default/files/Natio

nal%20HIV%20PrevPlan%202014- 2015(1).pdf

Omiepirisa Y (2012). Universal Precautions; A

review. The Nigerian Health Journal. 12(3); 66-

74.

Prüss-Üstün A, Rapiti E and Hutin Y (2005).

Estimation of the global burden of disease

attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among

health-care workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 48:482-490

Reda, Alex & Vandeweerd, Jean-Michel & Syre, T.R.

& Egata, Gudina. (2008). HIV/AIDS and exposure

of healthcare workers to body fluids in Ethiopia:

attitudes toward universal precautions. The

Journal of hospital infection. 71. 163-9.

10.1016/j.jhin.2008.10.003.

Sadob, A & Fawole, Olufunmilayo & Sadoh, Wilson

& Oladimeji, AO & Sotiloye, O. (2006). Attitude

of health care workers to HIV/AIDS. African

journal of reproductive health. 10. 39-46.

10.2307/30032442.

United States Agency for International Development

(USAID) (2000). Universal precautions guidelines

for primary health care canters in Indonesia.

Universal Precautions and training project,

Indonesia.

Voide C, Darling K, Kenfak-Foguena A, Erard V,

Cavassini M and Lazor-Blanchet C (2012).

Underreporting of needlestick and sharps injuries

among healthcare workers in a Swiss University

Hospital. Swiss Med Wkly.142:w13523

WHO. 2016. Reducing Risk, Promoting Health Life.

World Health Report. Geneva.