Procurement Disaster Assistance Team

October 2021

(FM-207-21-0002)

(PDAT) Field Manual

Procurement Information for FEMA Award Recipients

and Subrecipients

PDAT Field Manual

This page intentionally left blank

III

Contents

FOREWARD ........................................................................................................................................ 1

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3

1. Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 3

Navigating the Manual ............................................................................................................... 4

Additional Resources ................................................................................................................. 5

Chapter 2: Applicability of the Federal Procurement Under Grant Standards .......................... 6

Overview of Contracts ................................................................................................................ 6

Use of Contractors by Recipients and Subrecipients .................................................... 6

Role of The Federal Government in Recipient and Subrecipient Contracting ............. 6

Definition of Contract and Distinction from Subaward ................................................. 6

Contract Payment Obligations ........................................................................................ 7

Fixed Price and Cost-Reimbursement Contracts ........................................................... 7

Applicability ................................................................................................................................ 9

Procurement by State Entities ........................................................................................ 9

Procurement by Non-State Entities ............................................................................. 10

Chapter 3: General Procurement Under Grant Standards ...................................................... 15

Mandatory Standards ............................................................................................................. 15

Maintain Oversight ....................................................................................................... 16

Written Standards of Conduct ..................................................................................... 16

Gifts ............................................................................................................................... 16

Conflicts of Interests .................................................................................................... 17

Disciplinary Actions ...................................................................................................... 19

Need Determination ..................................................................................................... 20

Contractor Responsibility Determination .................................................................... 22

Maintain Records ......................................................................................................... 24

Contractor Selection ..................................................................................................... 25

Settlement of Issues .................................................................................................... 27

IV

Time-and-Materials Contracts ................................................................................................ 28

Considerations for State Entities using T&M Contracts ............................................. 28

Encouraged Standards ........................................................................................................... 29

Use of Federal Excess and Surplus Property .............................................................. 29

Use of Value Engineering ............................................................................................. 30

Use of Intergovernmental or Inter-Entity Agreements ................................................ 30

Chapter 4: Competition ............................................................................................................. 32

Restrictions to Competition .................................................................................................... 32

Unreasonable Requirements ....................................................................................... 33

Requiring Unnecessary Experience or Excessive Bonding ........................................ 33

Noncompetitive Pricing Practices ................................................................................ 34

Noncompetitive Contracts to Contractors on Retainer .............................................. 35

Organizational Conflicts of Interest ............................................................................. 36

Specifying Only a Brand Name Product ...................................................................... 37

Any Arbitrary Action in the Procurement Process ....................................................... 38

Geographic Preferences ......................................................................................................... 38

Exclusion of Contractors from Outside a Geographic Area ........................................ 38

Price Matching .............................................................................................................. 38

Reducing Bids ............................................................................................................... 38

Adding Weight to Evaluation Factors .......................................................................... 39

Set Asides ..................................................................................................................... 39

Written Procedures ................................................................................................................. 40

Clear and Accurate Description of Requirements ...................................................... 40

Nonrestrictive Specifications ....................................................................................... 41

Qualitative Requirements ............................................................................................ 41

Product Specifications ................................................................................................. 41

Identify All Requirements/Evaluation Factors ............................................................ 41

Prequalified Lists .................................................................................................................... 41

Chapter 5: Methods of Procurement ........................................................................................ 43

V

Informal Methods .................................................................................................................... 43

Procurement by Micro-Purchases ............................................................................... 43

Competition .................................................................................................................. 44

Prohibited Divisions ..................................................................................................... 44

Documentation ............................................................................................................. 44

Responsibility ............................................................................................................... 44

Procurement by Small Purchases ............................................................................... 44

Formal Methods ...................................................................................................................... 45

Procurement by Sealed Bidding .................................................................................. 45

Procurement by Proposals ........................................................................................... 48

Noncompetitive Procurement ................................................................................................. 51

Procurement by Micro-Purchase ................................................................................. 51

Single Source ................................................................................................................ 51

Public Emergency or Exigency ..................................................................................... 52

Federal Awarding Agency or Pass-Through Entity Approval ....................................... 54

Inadequate Competition .............................................................................................. 55

Justification and Documentation: ............................................................................... 56

Negotiation of Profit: .................................................................................................... 56

Ensure Compliance with Additional Requirements: ................................................... 56

Suggested Elements for Noncompetitive Procurement Justification ........................ 57

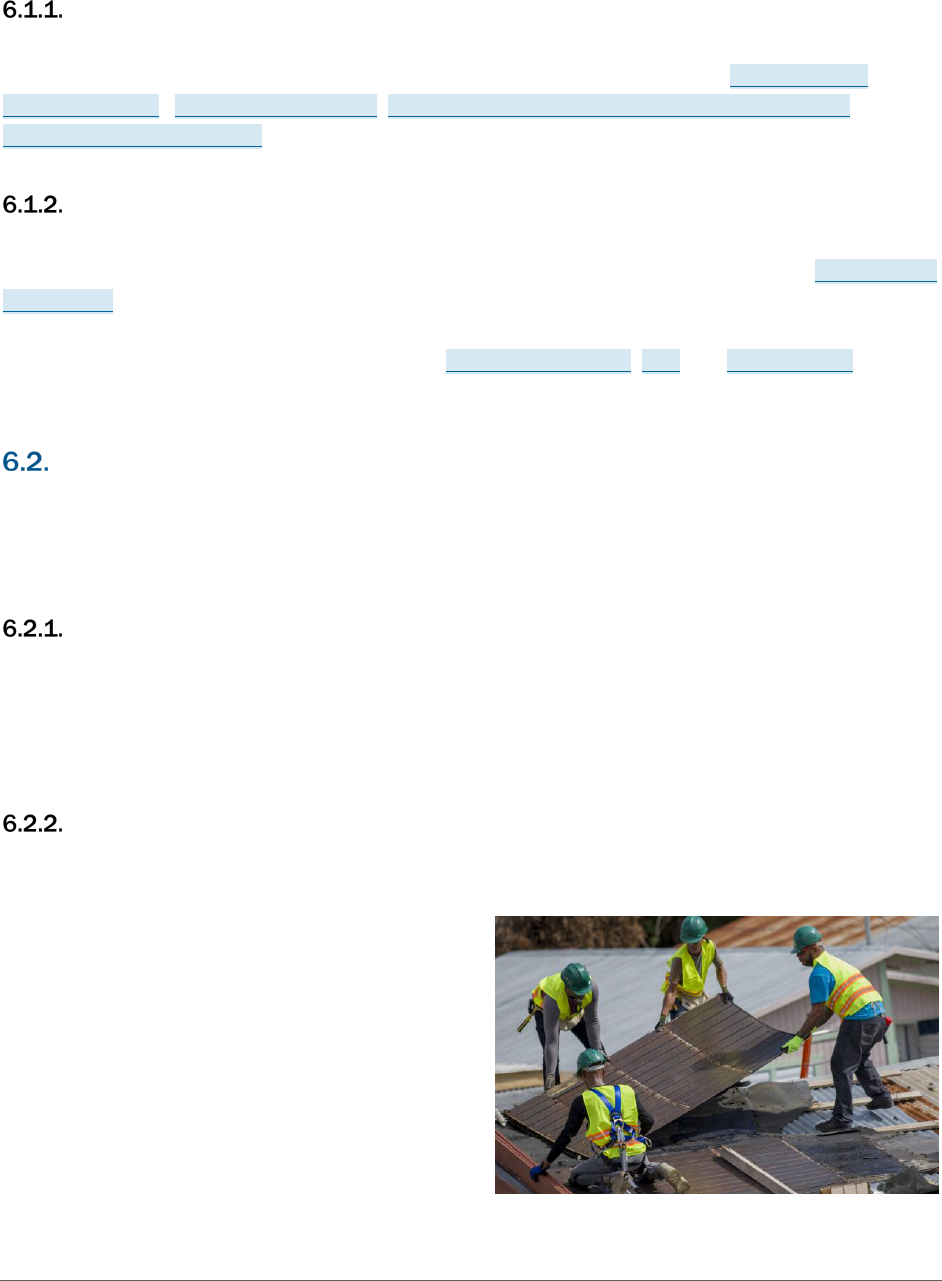

Chapter 6: Socioeconomic Contracting .................................................................................... 59

Affirmative Steps ..................................................................................................................... 59

Solicitation Lists ........................................................................................................... 59

Soliciting ........................................................................................................................ 59

Dividing Requirements ................................................................................................. 59

Delivery Schedules ....................................................................................................... 60

Obtaining Assistance .................................................................................................... 60

Prime Contractor Requirements .................................................................................. 60

Definitions for Socioeconomic Firms ..................................................................................... 61

Small Business ............................................................................................................. 61

VI

Women’s Business Enterprise ..................................................................................... 61

Minority Business ......................................................................................................... 61

Labor Surplus Area ....................................................................................................... 62

Labor Surplus Area Firm .............................................................................................. 62

Chapter 7: Domestic Preferences ............................................................................................ 64

Domestic Preferences for Procurement ................................................................................. 64

Applicability ................................................................................................................... 64

Definitions ..................................................................................................................... 64

Chapter 8: Procurement of Recovered Materials .................................................................... 66

Inapplicability to Indian Tribes and Private Nonprofit NFEs .................................................. 66

EPA Product Designation ........................................................................................................ 67

Affirmative Procurement Program .......................................................................................... 67

Solid Waste Disposal Services ............................................................................................... 68

Certifications ........................................................................................................................... 68

Chapter 9: Cost or Price Analysis ............................................................................................. 69

Price Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 69

Cost Analysis ........................................................................................................................... 70

Cost Plus a Percentage of Cost Contracts ............................................................................. 71

Four-Part Analysis ......................................................................................................... 71

Considerations for State Entities using CPPC Contracts ........................................... 72

Chapter 10: Federal Awarding Agency/Pass-Through Entity Review ...................................... 74

Pre-Award Procurement Review ............................................................................................. 74

Technical Specifications .............................................................................................. 74

Procurement Documents ............................................................................................. 74

Exemption ............................................................................................................................... 75

FEMA or Pass-Through Entity Review .......................................................................... 75

Self-Certification ........................................................................................................... 75

Post-Award Procurement Review ........................................................................................... 76

VII

Chapter 11: Bonding Requirements ........................................................................................ 77

Bid Guarantee ......................................................................................................................... 77

Performance Bond .................................................................................................................. 78

Payment Bond ......................................................................................................................... 78

Chapter 12: Contract Provisions .............................................................................................. 80

Required Provisions ................................................................................................................ 80

Contract Remedies ....................................................................................................... 80

Termination for Cause and Convenience ................................................................... 81

Equal Employment Opportunity ................................................................................... 81

Davis-Bacon Act ............................................................................................................ 82

Copeland Anti-Kickback Act ......................................................................................... 83

Contract Work Hours and Safety Standards Act ........................................................ 83

Rights to Inventions Made Under a Contract or Agreement ...................................... 83

Clean Air Act and the Federal Water Pollution Control Act ........................................ 84

Suspension and Debarment ........................................................................................ 84

Byrd Anti-Lobbying Amendment .................................................................................. 85

Procurement of Recovered Materials ......................................................................... 86

Prohibition on Contracting for Covered Telecommunications Equipment or Services

....................................................................................................................................... 86

Domestic Preferences for Procurements .................................................................... 87

FEMA Recommended Provisions............................................................................................ 87

Access to Records ........................................................................................................ 87

Changes and Modifications ......................................................................................... 87

DHS Seal, Logo, and Flags ........................................................................................... 88

Compliance with Federal Law, Regulations, and Executive Orders .......................... 88

No Obligation by the Federal Government .................................................................. 88

Program Fraud and False or Fraudulent Statements or Related Acts ...................... 88

Affirmative Socioeconomic Steps ................................................................................ 89

Copyright ....................................................................................................................... 89

Chapter 13: Beyond the Basics: Important Procurement Considerations ............................. 90

VIII

Considerations for Indian Tribal Governments ...................................................................... 91

Indian Tribal Preferences When Awarding Contracts ................................................. 91

Inapplicability of the Socioeconomic Affirmative Steps ............................................. 92

Contract Changes/Modifications ........................................................................................... 93

Scope of the Contract .................................................................................................. 94

Scope of Competition ................................................................................................... 94

Design-Bid-Build and Design-Build Contracts ........................................................................ 94

Design-Bid-Build ........................................................................................................... 94

Design-Build Contracts ................................................................................................. 95

CMAR Delivery Method ........................................................................................................... 96

Price as a Selection Factor for CMAR ......................................................................... 96

Cooperative Purchasing .......................................................................................................... 97

Joint Procurements ...................................................................................................... 97

Joint Procurements between State and Non-State Entities ...................................... 98

Using Another Jurisdiction’s Contract (Piggybacking) ................................................ 99

Non-State Entities and Piggybacking .......................................................................... 99

State Entities and Piggybacking .................................................................................. 99

Cooperative Purchasing Programs ....................................................................................... 100

Use of General Services Administration Schedules ................................................. 100

Other Supply Schedules and Cooperative Purchasing Programs ........................... 101

Prepositioned Contracts for Disaster Grants ....................................................................... 103

Non-State Entities and Prepositioned Contracts ...................................................... 104

State Entities and Prepositioned Contracts .............................................................. 104

Mutual Aid Agreements ........................................................................................................ 105

Purchasing Agents ................................................................................................................ 106

Non-State Entities and Purchasing Agents ............................................................... 106

State Entities and Purchasing Agents ....................................................................... 107

Chapter 14: Remedies for Procurement Noncompliance ..................................................... 108

Remedies for Noncompliance .............................................................................................. 108

Specific Conditions ............................................................................................................... 109

IX

APPENDIX ................................................................................................................................ 110

ACRONYM REFERENCE ................................................................................................................ 110

DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................. 111

PDAT Field Manual

1

FOREWARD

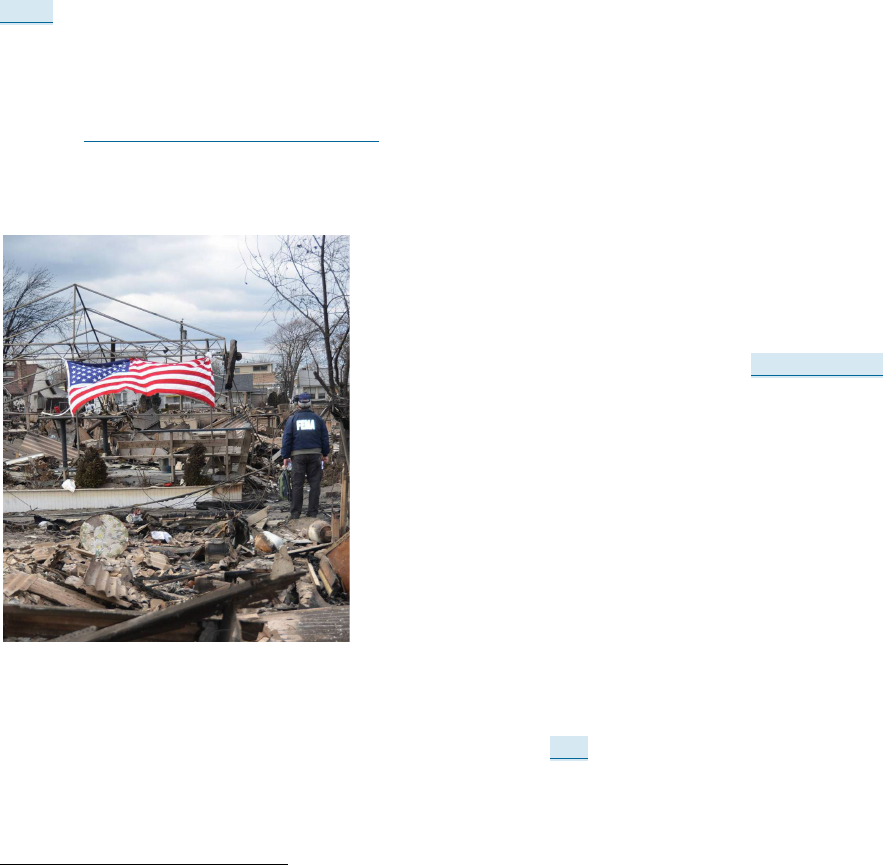

All FEMA awards are subject to the federal procurement standards under the Uniform Administrative

Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards found at 2 C.F.R. §§

200.317-200.327.

1

The Procurement Disaster Assistance Team (PDAT) Field Manual (Manual)

provides guidance regarding the mandatory requirements for FEMA award recipients and

subrecipients using federal funding to finance the procurement of property and services.

PDAT, a subcomponent of FEMA’s Grant Programs Directorate’s (GPD), Office of Enterprise Grant

Services, Policy Division, developed this Manual to provide accurate and updated information to

support both FEMA staff and FEMA award recipients and subrecipients regarding proper compliancy

under the federal procurement standards.

This version of the PDAT Field Manual will:

A. Exemplify the Agency’s mission statement:

Helping people before, during and after disasters;

B. Improve accessibility to all users of this Manual, providing clear and understandable language to

enhance understanding of the federal procurement standards;

C. Provide guidance regarding the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) revisions and final

guidance to the Uniform Rules, 2 C.F.R. Part 200 on August 13, 2020;

D. Illustrate how certain rules apply to an award recipient and/or subrecipient with real world

examples; and

E. Give additional resources, tools, and guidance to help all users develop further knowledge of the

procurement under grants subject matter.

FEMA administers over 45 disaster and non-disaster grant programs that provide over $3 billion in

federal assistance to state entities and non-state entities annually. All recipients and subrecipients

of FEMA awards are subject to the Uniform Rules found at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.317-200.327

, which

apply to contracts under FEMA awards or Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency

Assistance Act (Stafford Act) disaster declarations issued on or after November 12, 2020. This

Manual is applicable to FEMA awards and Stafford Act disaster declarations issued on or after

November 12, 2020.

For contracts under FEMA awards or Stafford Act declarations issued between December 26, 2014,

and November 11, 2020, please refer to the

Field Manual: Procurement Information for FEMA Public

Assistance Award Recipients and Subrecipients (October 2019).

1

Adopted by DHS at 2 C.F.R. § 3002.10. 79 Fed. Reg. 75871 (Dec. 19, 2014); Revised 2 C.F.R. 200 (Aug. 13, 2020).

PDAT Field Manual

2

For contracts under FEMA awards or Stafford Act declarations issued before December 26, 2014,

please refer to the

Field Manual: Public Assistance Grantee and Subgrantee Procurement

Requirements Under 44 C.F.R. PT. 13 AND 2 C.F.R. PT. 215 (December 2014).

While prior versions of the Field Manual are only directly applicable to FEMA’s Public Assistance

Program, all FEMA award recipients and subrecipients are encouraged to review these resources

since they provide guidance on the federal procurement under grants regulations unless restricted

by statue.

NOTE: FEMA will monitor the implementation of this policy through close coordination with various

program offices, regional staff, and, as appropriate, interagency partners and non-federal

stakeholders. FEMA will consider feedback, as appropriate, from these entities when issuing a final

policy.

3

Chapter 1: Introduction

1. Overview

This version of the Manual incorporates relevant content from both the 2014 Field Manual, the

2016 Supplement to the Field Manual,

2

and the 2019 Field Manual.

3

However, this version now

supersedes both previous resources following OMB revisions of OMB Guidance for Grants and

Agreements found in Title 2 of the Code of Federal Regulations. These revisions are applicable to all

FEMA awards issued on or after November 12, 2020, unless specifically indicated otherwise.

4

These

revisions include changes to the federal procurement standards, which govern how FEMA award

recipients and subrecipients must purchase under a FEMA award. For FEMA declarations made on,

or awards issued prior to November 12, 2020 and after December 26, 2014, please reference the

previous

federal procurement standards. While the Manual is intended to serve as a practical field

reference and has the effect of FEMA policy, it is not all encompassing, nor does it have the force

and effect of law and regulation.

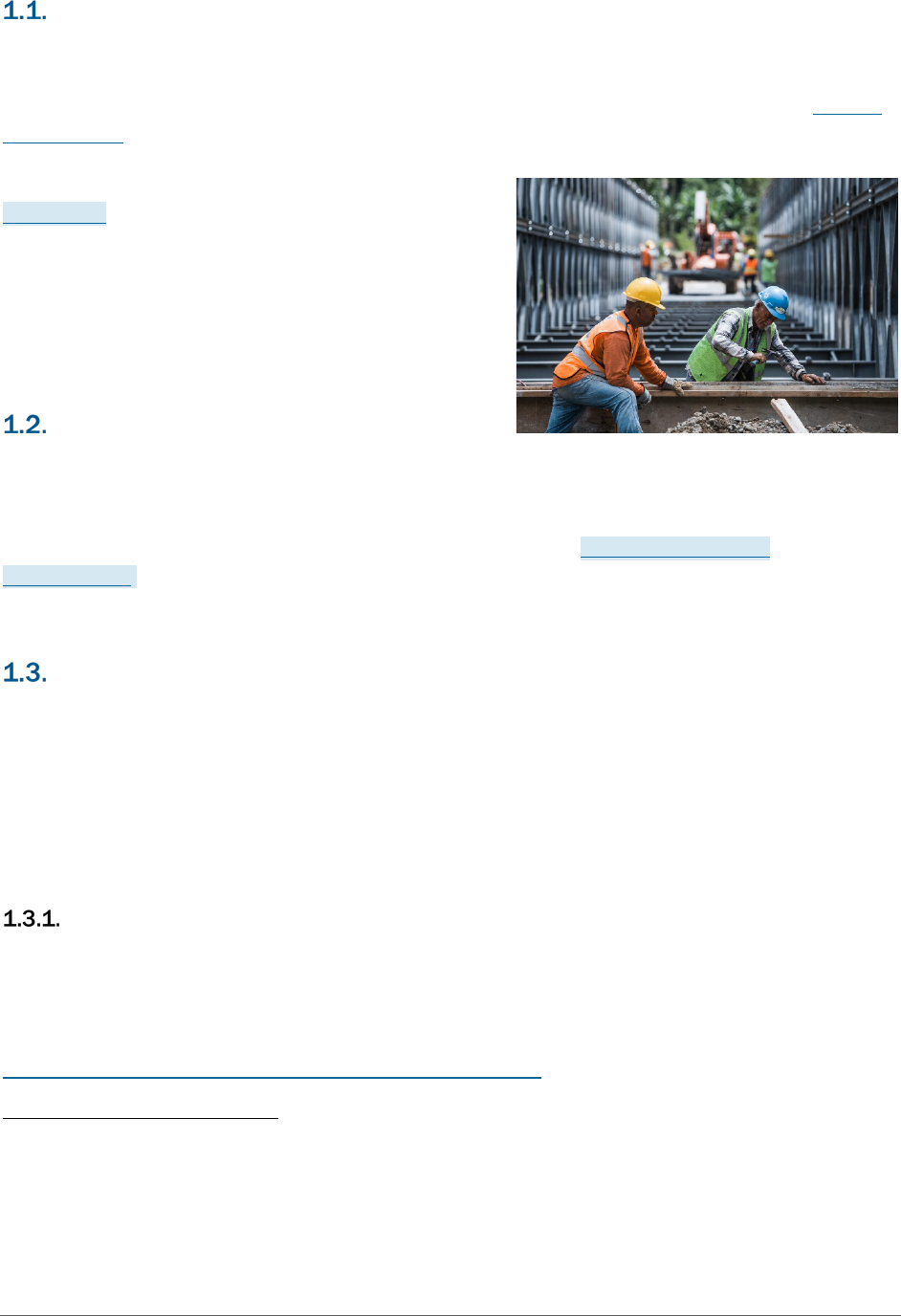

The information provided in the Manual is only intended to

serve as a basic reference and framework for both FEMA

staff involved in the various aspects of administering FEMA

awards as well as the recipients and subrecipients procuring

property and services as identified in the Uniform Rules. It is

not intended to be, nor does it provide or constitute legal

advice for FEMA award recipients and subrecipients.

Adherence to, application of, or use of this document

regarding a procurement subject to FEMA awards does not

guarantee the legal sufficiency of any procurement, nor does

it ensure that an award or subaward will not be audited or

investigated. All legal questions concerning the sufficiency of

a procurement in terms of federal procurement should be

referred to the recipients and subrecipients’ legal counsel.

As a condition of receiving reimbursement for contractor costs relating to FEMA’s federal assistance

programs, FEMA award recipients and subrecipients must comply with all applicable federal laws,

regulations, and executive orders. Each non-Federal Entity (NFE) is responsible for managing and

administering its federal awards in compliance with the applicable requirements, including but not

limited to the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for

2 Procurement Guidance for Recipients and Subrecipients under 2 C.F.R Part 200 (Uniform Rules) Supplement to the

Public Assistance Procurement Disaster Assistance Team (PDAT) Field Manual, June 21, 2016.

3 Field Manual – Procurement Information for FEMA Public Assistance Award Recipients and Subrecipients, October 2019.

4 2 C.F.R. § 200.216 Prohibition on certain telecommunications and video surveillance services or equipment is applicable

to all FEMA awards issued on or after August 13, 2020.

4

Federal Awards codified at 2 C.F.R. Part 200, which DHS adopted at 2 C.F.R. § 3002.10.

5

Specifically, the regulations at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.317-200.327 set forth the procurement standards

that NFEs must follow when using FEMA financial assistance to conduct procurements of real

property, goods, or services.

Navigating the Manual

This Manual is structured according to the progression of the federal procurement under grant

requirements listed in 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.317-200.327. Throughout the Manual, icons are used to help

identify key definitions, examples, tools/resources, and common DHS OIG audit findings.

Internal hyperlinks connect sections that are complementary within the Manual.

External hyperlinks connect the Manual with relevant external references or resources.

Blue boxes indicate important terms or sections to know and understand.

Gray boxes indicate an example where procurement under a FEMA award is being used.

Graphics indicate:

5 79 Fed. Reg. 75871 (Dec. 19, 2014); 85 Fed. Reg. 49506 (Aug. 13, 2020).

Definition

Examples

Tools/Resources

Common OIG Findings

St

ate Entities

Non-State Entities

5

Additional Resources

Questions regarding this policy may be directed to your assigned FEMA program analyst or grants

management specialist or the Centralized Scheduling and Information Desk (CSID) at

.

Related Tools and Resources

FEMA Public Assistance Program and Policy Guide (PAPPG)

The Uniform Rules

Top 10 Procurement under Federal Awards Mistakes

OIG DHS Audit Reports related to FEMA

Fire Management Assistance Grant Program Guide (FMAG)

FEMA Preparedness Grants Manual

Assistance to Firefighters Grants (AFG) Program

Hazard Mitigation Assistance Program (HMGP) Guidance

6

Chapter 2: Applicability of the

Federal Procurement Under Grant

Standards

Overview of Contracts

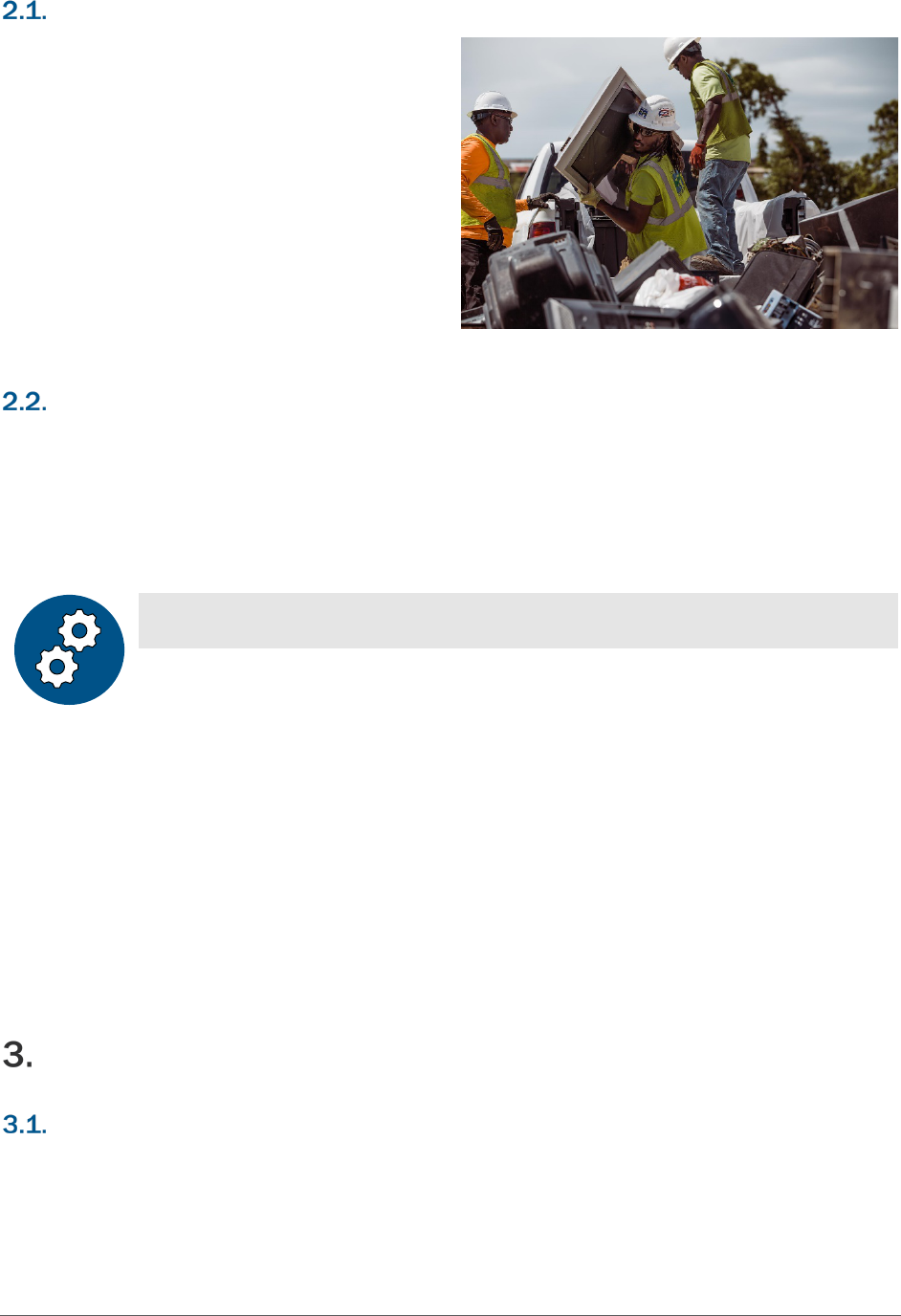

Use of Contractors by Recipients and Subrecipients

Recipients and subrecipients often use contractors to help carry out their FEMA award projects. For

example, a subrecipient may receive financial assistance under a FEMA award to repair a building

damaged by a major disaster, and it may then award a contract to a construction company to

complete the work. FEMA generally views contractor costs as an allowable cost

6

under the FEMA

award, as long as the costs are deemed reasonable.

Such a contract is a commercial transaction between the recipient or subrecipient and its contractor,

and there is privity, or a legally recognized relationship, of contract between the recipient or

subrecipient and its contractor. However, FEMA is not a party to that contract and has no privity of

contract with that contractor. FEMA’s legal relationship is only with the award recipient, not with the

subrecipient or contractors. Therefore, there is no contractual liability on the part of FEMA to the

recipient’s or subrecipient’s contractor.

Role of The Federal Government in Recipient and Subrecipient

Contracting

Although the federal government is not a party to a recipient’s or subrecipient’s contract, it

determines eligibility and reimbursement for a recipient’s or subrecipient’s contracting with outside

sources under the FEMA award. Recipients and subrecipients that use FEMA award funding must

comply with the procurement under grant requirements imposed by federal law, executive orders,

federal regulations, and terms of the grant award.

7

Definition of Contract and Distinction from Subaward

A contract is a promise or a set of promises for the breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the

performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty. There are three elements necessary

to form a contract:

6 2 C.F.R. § 200.403.

7 See Illinois Equal Employment Opportunity Regulations for Public Contracts, B-167015, 54 Comp. Gen. 6 (1974); see

also King v. Smith, 392 U.S. 309, 333 n. 34 (1968).

7

Mutual assent;

Consideration or a substitute; and

No defenses to formation;

8

such as duress, misrepresentation or fraud,

mistake and unconscionability.

Co

ntracts are generally governed by the common law, although contracts for the sale of goods such

as movable and tangible property, are governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code as well

as common law.

The term “contract” is general and includes several different varieties or types.

9

For example,

contracts can be categorized by subject matter such as construction, research, supply, service or by

the manner in which they can be formed and accepted such as bilateral or unilateral. Recipients and

subrecipients are free to select the type of contract they award consistent with the federal

procurement under grant rules and federal law, applicable state, Tribal, and local laws and

regulations, and within the bounds of good commercial business practice.

The Uniform Rules provide that a contract is for obtaining goods and services for the NFE’s own use

and creates a procurement relationship with the contractor.

10

Characteristics indicative of a

procurement relationship between the NFE and a contractor include when the contractor:

1. Provides the goods and services within normal business operations;

2. Provides similar goods or services to many different purchasers;

3. Normally operates in a competitive environment;

4. Provides goods or services that are ancillary to the operation of the federal program; and

5. Is not subject to compliance requirements of the federal program, as a result of the

agreement, though similar requirements may apply for other reasons.

11

Contract Payment Obligations

There are generally three types of contract payment obligations: fixed-price, cost-reimbursement, and

time-and-materials (T&M). Because the Uniform Rules do not define or fully describe these types of

contracts, the following provides a general overview of these contracts that is largely based on the

concepts and principles from the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR).

Fixed Price and Cost-Reimbursement Contracts

With regard to fixed price and cost-reimbursement contracts, the specific contract types range from

firm-fixed price, in which the contractor has full responsibility for the performance costs and resulting

profit or loss, to a cost-plus-fixed-fee, in which the contractor has minimal responsibility for the

performance costs and the negotiated fee or profit is fixed. There are also various incentive contracts

8 Restatement (Second) of Contract, § 1 (1981). Mutual assent also known as offer and acceptance,

9 Id.

10 2 C.F.R. § 200.1.

11 2 C.F.R. § 200.331(b).

8

in which the responsibilities of the contractor for performance costs and the profit or fee incentives

offered are tailored to the uncertainties involved in contract performance.

Fixed price contracts provide for a firm price or, in appropriate cases, an adjustable

price.

12

The risk of performing the required work at the fixed price is borne by the

contractor.

13

Firm-fixed price contracts are generally appropriate where the

requirement, such as scope of work, is well-defined and of a commercial nature.

14

Construction contracts, for example, are often firm-fixed price contracts.

NOTE: T&M contracts and

labor-hour contracts are not firm-fixed price contracts.

15

Cost-reimbursement contracts provide for payment of certain incurred costs to the

extent stipulated in the contract.

16

They normally provide for the reimbursement of

the contractor for its allowable costs, with an agreed-upon fee.

17

There is a limit to the

costs that a contractor may incur at the time of contract award, referred to as a ceiling

price. The contractor may not exceed the ceiling price without the recipient’s or

subrecipient’s approval, or the contractor does so at its own risk.

In a cost-reimbursement contract, the recipient or subrecipient bears more risk than in a firm-fixed

price contract.

18

A cost-reimbursement contract is appropriate when the details of the required

scope of work are not well-defined.

19

There are many variations of cost-reimbursement contracts,

such as cost-plus-fixed-fee, cost-plus-incentive-fee, and cost-plus-award-fee contracts.

20

However,

the cost plus a percentage of cost (CPPC) contract which is discussed in detail later on in this

Manual, is strictly prohibited for non-state entities.

21

12 48 C.F.R. Subpart 16.2 (Fixed-Price Contracts). A fixed price contract can be adjusted, but this normally occurs only

through the operation of contract clauses providing for equitable adjustment or other revisions of the contract price under

certain circumstances. 48 C.F.R. § 16.203 (Fixed-Price Contracts with Economic Price Adjustment).

13 Bowsher v. Merck & Co., 460 U.S. 824, 826 at n. 1 (U.S. 1983) (“A pure fixed-price contract requires the contractor to

furnish the goods or services for a fixed amount of compensation regardless of the costs of performance, thereby placing

the risk of incurring unforeseen costs of performance on the contractor rather than the Government.”).

14 48 C.F.R. § 16.202-2.

15 48 C.F.R. § 16.201(b).

16 48 C.F.R. Subpart 16.3 (Cost-Reimbursement Contracts).

17 48 C.F.R. Subpart 16.3.

18 Kellogg Brown & Root Servs. v. United States, 742 F.3d 967, 971 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (“…cost-reimbursement contracts are

intended to shift to the Government the risk of unexpected performance costs…”).

19 48 C.F.R. § 16.301-2(a).

20 48 C.F.R. Subpart 16.3.

21 See 2 C.F.R. § 200.323(d); DHS Office of Inspector General, Report No. OIG-14-44-D, FEMA Should Recover $5.3

Million of the $52.1 Million of Public Assistance Grant Funds Awarded to the Bay St. Louis Waveland School District in

Mississippi-Hurricane Katrina, p. 4 (Feb. 25, 2014) (“Federal regulations prohibit cost-plus-percentage-of-cost contracts

because they provide no incentive for contractors to control costs—the more contractors charge, the more profit they

make.”). Note, Report No. OIG-14-44-D references 2 C.F.R. § 200.323(d). However, the 2 C.F.R. revisions applicable on or

after November 12, 2020 modified the regulation citation to 2 C.F.R. § 200.324(d). The language found at both citations is

identical and states “The cost plus a percentage of cost and percentage of construction cost methods of contracting must

not be used.” Although the OIG references an old citation, the report is still valid since the regulatory language was

unchanged and the citation was merely updated.

9

Applicability

The procurement under grant standards set forth at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.317-200.327 apply to all FEMA

awards issued on or after November 12, 2020.

22

Failure to follow the Uniform Rules found in 2

C.F.R. Part 200 when procuring and selecting contractors places FEMA award recipients and

subrecipients at risk of not receiving either their full reimbursement for associated disaster costs or

having obligated funds recouped by FEMA. This Manual focuses on the procurement standards set

forth in 2 C.F.R. Part 200. For procurement guidance associated with disasters declared before

November 12, 2020, please refer to the

Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and

Audit Requirements for Federal Awards.

There are different sets of procurement rules that apply to

state and non-state entities. A FEMA award recipient,

therefore, must first determine if it is a state or non-state

entity as defined under the federal procurement rules.

Additional guidance for determining an NFE’s entity type

and identifying the procurement standards applicable to

that entity type can be found in the subsections below.

Procurement by State Entities

The federal procurement standards applicable to state entities are set forth in 2 C.F.R. § 200.317.

State

23

entities include:

Any state of the United States,

The District of Columbia,

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico,

U.S. Virgin Islands,

Guam,

American Samoa,

The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and

Any agency or instrumentality thereof exclusive of local governments.

When procuring property or services under a FEMA award, a state entity must:

Follow the same policies and procedures it uses for procurements from its non-federal funds

found at 2 C.F.R. § 200.317

(procurement by states);

22 85 Fed. Reg. 49506 (Aug. 13, 2020).

23 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 Institutions of Higher Education.

St

ate Entities

10

Follow all necessary affirmative steps found in 2 C.F.R. § 200.321 (contracting with small and

minority businesses, women’s business enterprises, and labor surplus area firms) to assure that

small and minority businesses, women’s owned enterprises, and Labor Surplus Area (LSA) firms

are used when possible;

Provide a preference, to the greatest extent practicable, for the purchase, acquisition, or use of

goods, products or materials produced in the United States found in 2 C.F.R. § 200.322

(domestic preferences for procurements);

Ensure compliance with procurement of recovered materials guidelines found at 2 C.F.R. §

200.323 (procurement of recovered materials); and

Include all necessary contract provisions required by 2 C.F.R. § 200.327 (mandatory contract

provisions).

Even if a state complies with its own policies and procedures used for procurement from non-federal

funds when it procures property or services under a FEMA award, FEMA will still evaluate the

procurement to determine whether the costs conform to the Cost Principles at

2 C.F.R. Part 200,

Subpart E.

24

For example, while state entities are not prohibited by the federal rules to award a CPPC

contract, FEMA may still question the contract costs as unreasonable, since this type of contract

incentivizes the contractor to drive up costs to increase profit. A state must use the Cost Principles at

2 C.F.R. Part 200, Subpart E as a guide in the pricing of fixed-price contracts and subcontracts where

costs are used in determining the appropriate price.

25

Additionally, while more prescriptive conflict of interest rules apply to non-state entities, FEMA,

pursuant to its authorities, requires that all NFEs, including state entities, maintain written conflict of

interest rules, including organizational conflicts of interests rules, governing the actions of their

procurement professionals and disclose any potential conflict of interest to FEMA in writing.

26

Procurement by Non-State Entities

The federal procurement under grant standards applicable to non-state entities when procuring

property or services under an award or cooperative agreement are set forth in 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.317-

327. Non-state entities are eligible FEMA award recipients that do not meet the “state” definition

found at 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 States.

24 A cost is reasonable if, in its nature and amount, it does not exceed that which would be incurred by a prudent person

under the circumstances prevailing at the time the decision was made to incur the cost. The question of reasonableness is

particularly important when the NFE is predominantly federally funded.

25 2 C.F.R. § 200.401.

26 2 C.F.R. § 200.112.

11

Non-state entities include:

Local

27

and Tribal

28

governments,

Institutions of Higher Education (IHEs)

29

that do not meet the definition

of state,

Hospitals

30

that do not meet the definition of state instrumentality, and

Other PNPs

31.

Although an Indian Tribal Government may potentially be either a recipient or subrecipient under the

Stafford Act and other FEMA financial assistance programs, Indian Tribal Governments are not

defined as a “state” at 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 States. In turn, Indian tribes must comply with the federal

procurement under grant standards applicable to non-state entities. Each of the federal procurement

under grant requirements applicable to non-state entities will be expanded upon in this Manual.

The NFE must have and use documented procurement procedures, consistent with state, local, and

Tribal laws and regulations and the standards of this section, for the acquisition of property or

services required under a Federal award or subaward. As set forth in 2 C.F.R. § 200.318(a),

an NFE

must use its own documented procurement procedures which reflect applicable state, local, and

Tribal laws and regulations, provided that the procurements conform to appliable federal law and the

federal procurement standards identified in §§ 200.317-200.327.

The federal procurement under grant standards only address certain, limited procurement concepts,

and do not focus on all possible procurement issues. Where the federal procurement under grant

standards do not address a specific procurement issue, a non-state entity must abide by the

applicable state, local, and/or Tribal procurement standards or regulations. However, where a

difference exists between a federal procurement standard and a state, local, and/or Tribal

procurement standard or regulation, the non-state entity must apply the rule(s) that allow for

compliance with all applicable levels of governance.

Example: Non-State Entity Application of the Rules

Scenario: Non-state entity procurement under grant standards may, in some cases, be

more restrictive than the federal procurement standards at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.318-

200.327. For example, the regulation at 2 C.F.R. § 200.320(a)(2) allows a non-state

entity to use procurement by small purchase procedures when the total value of services, property,

or other property acquired remains below the federal Simplified Acquisition Threshold (SAT),which is

27 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 Local government.

28 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 Indian tribe.

29 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 Institutions of Higher Education (IHEs).

30 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 Hospital.

31 2 C.F.R. § 200.1 Nonprofit organizations.

Non-State

Entities

12

$250,000 as of June 2018.

32

However, it may be the case that the applicable state, local, and/or

Indian Tribal procurement standards and regulations do not permit small purchase procedures for

acquisitions over $100,000. Which acquisition threshold is a non-state entity required to comply with

in this scenario?

Answer: In such a circumstance where there is a difference between state, local, and/or Tribal

procurement standards and these federal procurement under grant standards, the non-state entity

is required to follow the rule(s) that allows compliance with all applicable levels of governance. A

more permissive federal procurement standard would not control over a more restrictive applicable

state, local, and/or Tribal standard. In this scenario, complying with the $100,000 threshold allows

for compliance at all levels.

NOTE: This concept of differing and following the rule that allows compliance with all applicable

levels only applies to non-state entities. This underscores the importance of an NFE’s evaluation of

whether it is a state or non-state entity as defined under the federal procurement rules. State

entities will always follow the procurement standards found at 2 C.F.R § 200.317, which directs

them to utilize their own procurement standards, take socioeconomic affirmative steps at 2 C.F.R. §

200.321, provide a preference for the purchase of goods, products, or materials produced in the

United States as required by 2 C.F.R. § 200.322, comply with applicable guidelines regarding

procurement of recovered materials as set forth in 2 C.F.R. § 200.323, and include all necessary

contract provisions required by 2 C.F.R. § 200.327. Conversely, non-state entities must adhere to

their own procurement policies and procedures, applicable state and/or Tribal laws, and the federal

procurement under grant requirements found at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.318-200.327.

Example: Differing Procurement Standards for State vs. Non-State Entities –

Geographic Preference

Scenario: The President declares a major disaster for the State of Z as the result of a

hurricane, and the declaration authorizes Public Assistance (PA) for all counties in the

State. The hurricane damaged a building of the State Z Agency of Transportation. Following approval

of a

Project Worksheet to repair the damaged building, State Z Agency of Transportation procures

the services of a contractor to complete the repairs to the building by following the same policies and

procedures it uses for procurements from its non-federal funds when it procures construction

services. The State Z Agency, when evaluating the bids for the work, uses a state statutorily imposed

geographic preference and awards a contract, and the contract includes all clauses required by

federal law, regulation, and executive order. Is the use of the geographic preference by State Z

Agency permissible under 2 C.F.R. § 200.317?

32 See 2 C.F.R. § 200.1; 48 C.F.R. § 2.101. While the SAT is periodically adjusted for inflation, it was adjusted to

$250,000 as of June 2018. OMB Memo (M-18-18), available at

https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2018/06/M-18-18.pdf

13

Answer: Yes, the use of the geographic preference is permissible under 2 C.F.R. § 200.317. The

federal regulation at 2 C.F.R. § 200.317 provides, in relevant part, that a state must follow the same

policies and procedures it uses for procurements from its non-federal funds when it procures

property and services under a FEMA award. In this case, the State Z Agency of Transportation

followed these procedures, which included adhering to a statutorily imposed geographic preference

when evaluating the bids.

33

NOTE: It is important to recognize that the procurement standards are different for state and non-

state entities. As it relates to non-state entities, the federal procurement standards under the

Uniform Rules at

2 C.F.R. § 200.319(c) prohibit the use of statutorily or administratively imposed

state, local, and/or Tribal geographic preferences in the evaluation of bids or proposals, except in

those cases where applicable federal statutes expressly mandate or encourage geographic

preferences. However, because the state is not subject to regulation at 2 C.F.R. § 200.319, the

regulation bears no applicability to the question presented in this scenario.

Example: Waivers of State, Local, and/or Tribal Procurement Standards for Non-

State Entities

Scenario: As a result of, or in anticipation of, a disaster or emergency, NFEs may,

pursuant to their own rules, waive their own procurement standards or regulations.

Do such waivers apply to the federal procurement under grant rules for non-state entities?

Answer: No. Even though the appropriate NFE may have waived state, local, and/or Tribal

procurement standards or regulations, the NFE cannot waive the applicable federal procurement

under grant standards. Where state, local, and/or Tribal procurement standards or regulations have

been waived pursuant to the NFE’s own legal requirements, the federal procurement under the

Grant Rules found at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.318-200.327 continue to apply to a non-state entity

regardless of such a waiver by an NFE.

NOTE: NFEs must follow the federal procurement requirements found at 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.317-

200.327. However, federal regulations allow for noncompetitive procurements under certain

circumstances, including when a non-state entity determines that immediate actions required to

address the public exigency or emergency cannot be delayed by a competitive solicitation. More

information regarding emergency and exigency circumstances are addressed later within this

Manual.

33 Whether or not a geographic preference regime imposed by a state raises Constitutional issues under the dormant

commerce clause is outside the scope of this Manual.

15

Chapter 3: General Procurement

Under Grant Standards

The general procurement under grant standards at 2 C.F.R. § 200.318 set

forth various standards for non-state entities, some of which are mandatory

and some of which are encouraged. There are eleven general procurement

standards: eight are mandatory and three are encouraged. Chapter 3 will

discuss

T&M Contracts and each of the following general procurement

standards:

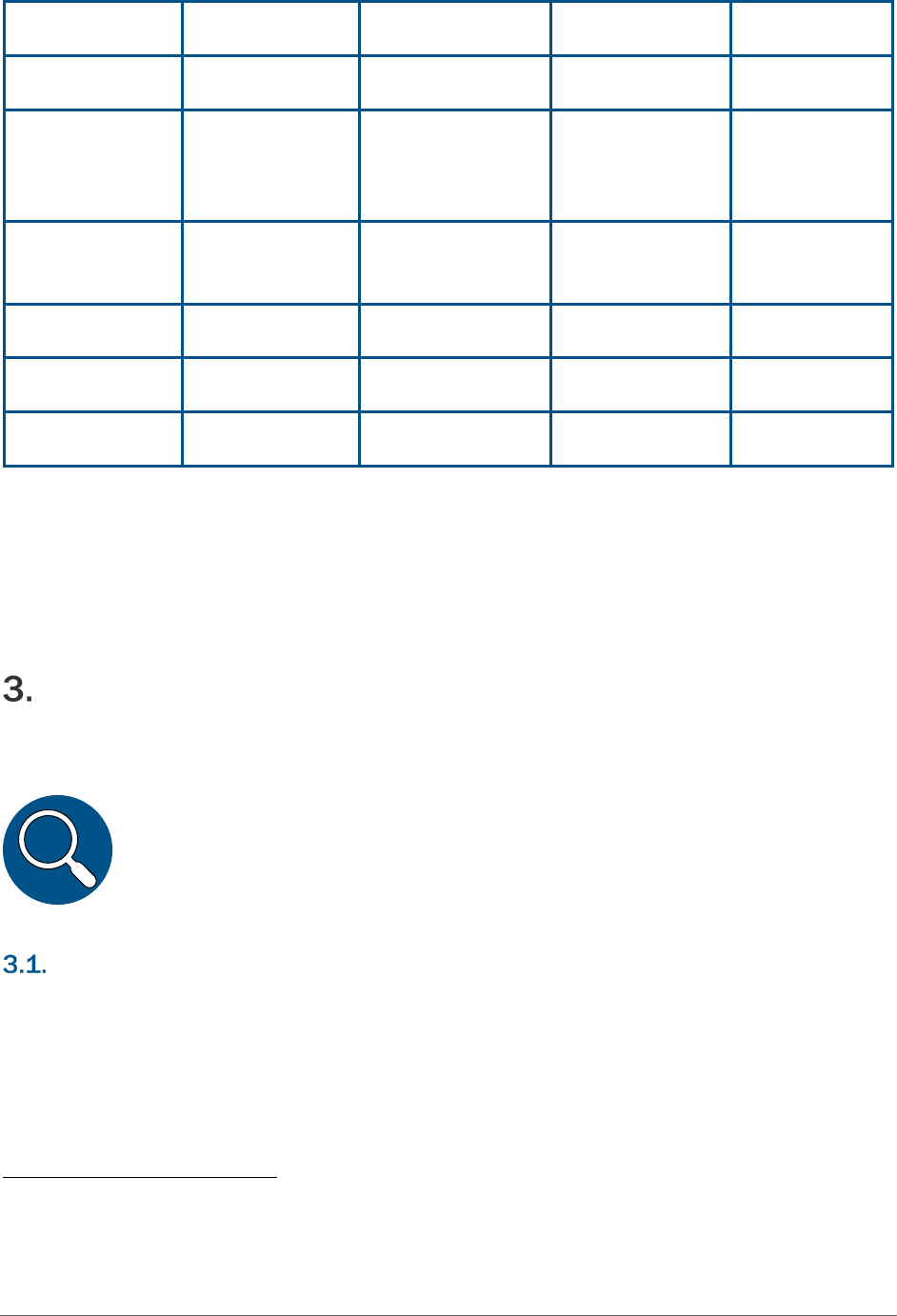

Mandatory Standards

Non-state entities must use their own documented procurement procedures which reflect applicable

state, local, and Tribal laws and regulations, provided the procurement conforms to applicable

Federal law and the standards set forth in 2 C.F.R. Part 200

.

NOTE: Non-state entities must comply with all other applicable Federal laws, regulations, and

executive orders when procuring services or property under a FEMA award. The requirements

identified in this Manual only address the federal procurement standards. Additional information

regarding FEMA remedies to address NFE noncompliance is outlined in Chapter 14 of this Manual.

Mandatory Standards

Maintain Oversight

Written Standards of Conduct

o Gifts

o Conflict of Interest

Need Determination

Contractor Responsibility

Determination

Maintain Records

Settlement of Issues

Encouraged Standards

Use of Federal Excess/Surplus

Property

Value Engineering

Use of Intergovernmental or Inter-

Entity Agreements

Non-State

Entities

16

Maintain Oversight

A non-state entity must maintain oversight to ensure that contractors perform in accordance with the

terms, conditions, and specifications of their contracts or purchase orders.

34

If a non-state entity

lacks qualified personnel within its organization to undertake such oversight as required by

2 C.F.R.

§ 200.318(b), then FEMA expects the non-state entity to acquire the necessary personnel to provide

these services.

Contractors selected to perform procurement functions

on behalf of the non-state entity are subject to the

Uniform Rules. Examples of this oversight include

making sure contractors comply with contract terms

and conditions, invoices are correct, and goods and

services are received.

Written Standards of Conduct

FEMA expects a recipient or subrecipient, when contracting under a FEMA award, to ensure that

procurement transactions are conducted with impartiality and without preferential treatment.

35

The

regulations require

non-state entities to have written standards of conduct covering conflicts of

interests and governing the actions of employees engaged in the selection, award, and

administration of contracts. These standards must include disciplinary actions in the event of

violations of the standards of conduct.

36

Gifts

The officers, employees, and agents of non-state entities may neither solicit nor accept gifts or

gratuities, favors, or anything of monetary value from contractors or parties to subcontracts.

This

would include entertainment, hospitality, loans, and forbearance. This also includes services as well

as gifts such as training, transportation, personal travel, lodgings, and meals, whether provided in-

kind, by purchase of a ticket, payment in advance, or reimbursement after the expense has been

incurred.

37

DE MINIMIS GIFTS EXCEPTION

A non-state entity may set standards for accepting gratuities in situations in which the financial

interest is not substantial, or the gift is an unsolicited item of nominal value. Federal regulations do

not provide any additional clarity as to what constitutes “substantial” or “nominal intrinsic value,”

such that the content of any such exception is left to the discretion of the non-state entity. The

Standards of Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch

provide a useful guide in analyzing a

34

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(b).

35

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(1)(2).

36

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(1).

37

Id.

17

non-state entity’s exception.

38

However, the non-state entity will need to look to applicable state,

local, and/or Tribal requirements and consult its servicing attorney to determine if other applicable

rules speak to a specific dollar amount for a de minimis exception.

Conflicts of Interests

No employee, officer, or agent may participate in the selection, award, or administration of a contract

supported by a federal award if he or she has a real or apparent conflict of interest. The purpose of

this prohibition is to ensure, at a minimum, that employees involved in the award and administration

of contracts are free of undisclosed personal or organizational conflicts of interest—both in fact and

appearance.

39

REAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

A real conflict of interest arises when an employee, officer, any member of his or her immediate

family, his or her partner, or an organization which employs or is about to employ any of the

aforementioned individuals, has a financial or other interest or a tangible personal benefit from a

firm considered for a contract.

FINANCIAL INTEREST

Although the term “financial interest” is not defined or otherwise described in the Uniform Rules, a

financial interest can be considered to be the potential for gain or loss to the employee, officer, or

agent, any member of his or her immediate family, his or her partner, or an organization which

employs or is about to employ any of these parties as a result of the particular procurement. The

prohibited financial interest may arise from:

Ownership of certain financial instruments or investments like stock, bonds, or real estate; or

A salary, indebtedness, job offer, or similar interest that might be affected by the procurement.

Example: Real Conflict of Interest

Scenario: During its annual review of historic properties, the J County identified several

structural problems to its historic courthouse. Working with its State Historic

Preservation Office, J County formed a committee to issue a Request for Proposal (RFP) to rebuild

the courthouse. One of the County Commissioners is selected to serve as the chair of the committee.

The County Commissioner’s brother owns a prominent construction company in J County called

Historic Renovation & Construction Co. This company submitted a proposal for the project, and J

38

Cf. 5 C.F.R. § 2635.203(b) (defining “gift” under the Standards of Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch).

39

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(2).

18

County awarded it the contract to rebuild the courthouse. Did J County violate the federal

procurement regulations?

Answer: Yes. The regulation at 2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(1) prohibits real conflicts of interest which

includes, among other things, awarding contracts to any employee or member of his or her

immediate family with a financial interest in a firm considered for a contract. Here, the County

Commissioner’s brother, a member of their immediate family, has a financial interest in Historic

Renovation & Construction Co. because he owns the company. Therefore, J County violated the

federal procurement regulations.

APPARENT CONFLICT OF INTEREST

An apparent conflict of interest is an existing situation or relationship that creates the appearance

that an employee, officer, or agent, any member of his or her immediate family, his or her partner, or

an organization which employs or is about to employ any of the parties indicated herein, has a

financial or other interest in or a tangible personal benefit from a firm considered for a contract.

Example: Apparent Conflict of Interest

Scenario: Town of Y procured concrete from Company Z because Company Z offered

the best rates and the most competitive delivery schedule. The owner of Company Z

and the Town of Y’s Purchasing Officer were college roommates. Did Town of Y violate

the federal procurement regulations?

Answer: Yes. The regulations at 2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(1) prohibit both real and apparent conflicts of

interest. Even though Town of Y procured goods from Company Z based on its rates and delivery

schedule, the relationship between owner of Company Z and Town of Y’s Purchasing Officer creates

the appearance that an employee of Town of Y has a personal interest in awarding the contract to

Company Z. Therefore, Town of Y violated the federal procurement regulations.

ORGANIZATIONAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

If a non-state entity has a parent, affiliate, or subsidiary organization that is not a state, local

government, or Indian tribe, the non-state entity must also maintain written standards of conduct

covering organizational conflicts of interest. One type of organizational conflict of interest occurs

when, because of relationships with a parent company, affiliate, or subsidiary organization, the non-

state entity is unable or appears to be unable to be impartial in conducting a procurement action

involving a related organization.

40

40

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(2).

19

Example: Organizational Conflict of Interest

Scenario: A hospital in the Town of E sustained structural damage during a hurricane.

The hospital owns several subsidiary companies, including a local construction firm.

Because of its relationship with the hospital, the construction firm is privy to detailed information

regarding the work needed. The hospital issued an

Invitation for Bids (IFB) and decided to award its

contract to the local construction firm. Did the hospital violate the federal procurement regulations?

Answer: Yes. The regulation at 2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(2) requires written standards of conduct

regarding these types of organizational conflicts of interests, and 2 C.F.R. § 200.319(b)(5) prohibits

procurements involving organizational conflicts of interests. This means that a non-state entity is

unable or appears to be unable to be impartial in conducting a procurement action because of a

relationship between a parent company, affiliate, or subsidiary organization that is not a state, local

government, or Indian tribe. In this case, the hospital was unable or appeared to be unable to be

impartial in awarding a contract to its subsidiary construction firm, which was not a state, local

government, or Indian tribe. Therefore, the hospital violated the federal procurement regulations.

Disciplinary Actions

The standards of conduct must provide for disciplinary actions to be applied for violations of such

standards by officers, employees, or agents of the non-state entity.

41

For example, the disciplinary

action for a non-state entity employee may be dismissal.

Another possible way to resolve a conflict of interest, if allowed under the non-state entity’s

procurement procedures and other applicable laws, is recusal. A recusal may be appropriate when

an employee involved in awarding a contract has a financial interest or other business or personal

relationship with a contractor bidding for the award. By removing that employee from the contractor

selection process, a non-state entity may be able to resolve the conflict. A non-state entity is

encouraged to check its state and local procurement rules regarding conflicts of interest and

document any recusals in writing to include in its procurement file.

Example: Recusal

Scenario: Nonprofit X suffered significant flooding to its headquarters building

following a hurricane in City Y. As a result, Nonprofit X issued an IFB for mold

remediation companies to assess the damage. A procurement specialist of Nonprofit X

is part owner of a mold remediation company that plans to bid for the contract to repair the

headquarters building. The procurement specialist of Nonprofit X recused herself and did not

participate in the evaluation or selection of mold remediators. Nonprofit X documented the

41

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(c)(1).

20

procurement specialist’s recusal and included documentation in its procurement file when seeking

federal reimbursement. Did Nonprofit X violate the federal procurement under grant regulations?

Answer: No. Even though the procurement specialist had a conflict of interest because she had a

financial interest in the mold remediation company as part owner, Nonprofit X resolved the conflict of

interest by recusal. By excluding the procurement specialist from the evaluation and selection of

mold remediation companies, Nonprofit X was able to comply with the federal procurement under

grant rules governing conflicts of interest.

Need Determination

A non-state entity must avoid the acquisition of unnecessary or duplicative items and procure goods

and services using the most economical approach when feasible.

42

To this end, the federal

procurement regulations instruct a non-state entity to do the following:

AVOID UNNECESSARY OR DUPLICATIVE ITEMS

A non-state entity must have procedures to avoid the acquisition of unnecessary or duplicative

supplies or services. A non-state entity must limit its procurements to its current and reasonably

expected needs to carry out the scope of work under a FEMA award. A non-state entity may not add

items or quantities unrelated to the scope of work or procure additional items for use later. A non-

state entity may award advance contracts before an incident occurs for the potential performance of

work under a Stafford Act emergency or major disaster. These are also known as prepositioned or

pre-awarded contracts, which are eligible for reimbursement when used to support response and

recovery efforts pursuant to a financial assistance award.

Example: Procurement of Unnecessary Items

Scenario: This year, the Island of X experienced widespread power outages due to a

Super Typhoon striking the region. In particular, the Island’s airport lost power for

weeks. A functioning airport is essential for Island residents because they rely on

imported goods and supplies to function. The airport requires four generators to restore power. This

is the third year in a row that the Island of X suffered a Typhoon and the third consecutive year that

the airport lost power for an extended period. To get the airport up and running, and to prepare for

potential damage from future Typhoons, the Island procured eight generators using FEMA award

funds. Did the Island of X comply with the federal procurement regulations?

Answer: No. Pursuant to 2 C.F.R. § 200.318(d), the Island is prohibited from procuring unnecessary

or duplicative items. In this case, the Island needed only four generators to meet its current

requirement of restoring power to the airport. The federal procurement regulations do not allow for

42

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(d).

21

the acquisition of duplicative items or stockpiling items for future use. Therefore, the Island of X

violated the federal procurement regulations.

CONSOLIDATE OR BREAK OUT PROCUREMENTS

A non-state entity should consider consolidating or breaking out procurements to obtain a more

economical purchase.

43

Example: Breaking Out Procurements

Scenario: County of X solicited and received unit price quotes from 13 debris removal

contractors for various types debris removal work. Contractor A submitted the lowest

bid for removing and disposing of vegetative debris. Contractor B submitted the lowest

bid for removing and disposing of construction and demolition debris. Contractor C submitted the

lowest bid for both tasks combined. Although the combined total was the lowest bid, the unit price

quotes for vegetative debris and construction and demolition debris (each elements of the combined

bid) were higher than Contractors A and B, respectively.

County of X considered the bids submitted and realized that it would be able to obtain a more

economical purchase if it broke up these purchases into separate procurement actions awarded to

Contractor A and B. The County awarded the vegetative debris removal work to Contractor A and the

construction and demolition debris removal work to Contractor B. Is County of X in compliance with

the federal procurement under grant rules by breaking up their procurement in order to obtain a

more cost-effective purchase?

Answer: Yes. In this scenario, the County broke up their procurement into two activities and awarded

two contracts (one for vegetative debris removal work and another for construction and demolition

debris removal work) to contractors that had the lowest bid for each of the two tasks. This decision

resulted in a more economic purchase overall. By awarding two separate contracts, the County

saved costs that would otherwise be unnecessary for efficient contract performance.

NOTE: Non-state entities may break down procurements to obtain a more economical purchase or

permit maximum participation by small and minority businesses, women’s business enterprises, and

LSA firms when economically feasible.

44

However, non-state entities are not allowed to break down

procurements to avoid the additional procurement requirements that apply to larger purchases.

LEASE VERSUS PURCHASE ANALYSIS

A non-state entity must, where appropriate, make an analysis of lease versus purchase alternatives,

and any other appropriate analysis to determine the most economical approach. FEMA may review

43

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(d).

44

2 C.F.R. § 200.321.

22

any costs used in the comparison for reasonableness, realistic current market conditions, and based

on the expected useful service life of the asset.

45

Contractor Responsibility Determination

A non-state entity must award contracts only to responsible contractors possessing the ability to

perform successfully under the terms and conditions of a proposed procurement.

46

FEMA requires

the non-state entity to document its determination that a prospective contractor qualifies as

responsible, as well as its basis for such determination. In making a contractor responsibility

determination, the non-state entity must consider such matters as contractor integrity, compliance

with public policy, record of past performance, and financial and technical resources.

47

CONTRACTOR INTEGRITY

A contractor must have a satisfactory record of integrity and business ethics. In analyzing a

contractor’s integrity, the non-state entity may consider whether the contractor has:

Committed fraud or a criminal offense in connection with obtaining or attempting to obtain a

contract;

Committed embezzlement, theft, forgery, bribery, falsification or destruction of records, or tax

evasion;

Committed any other offense indicating lack of business integrity or business honesty that

seriously and directly affects the present responsibility of the contractor; or

Been indicted for any of the above-mentioned offenses.

PUBLIC POLICY

A contractor must have complied with the public policies of the federal government as well as the

public policies of appropriate states, local governments, or Indian Tribal Governments.

48

The non-

state entity should look at the contractor’s past and current compliance with matters such as:

Equal opportunity and nondiscrimination laws; and

Applicable prevailing wage laws, regulations, and executive orders (EO)

45

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(d).

46

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(h).

47

Id.

48

Id.

23

RECORD OF PAST PERFORMANCE

A contractor must be able to demonstrate that it has enough resources (i.e., personnel and

subcontractors), with adequate experience, to perform the required work. In addition, the contractor

must provide that it has adequate prior experience carrying out similar work, which can be

demonstrated by:

Having the necessary organization, accounting, and operational controls;

Adhering to schedules, including the administrative aspects of performance;

Exhibiting business-like concern for the interest of the customer; and

Meeting quality requirements.

FINANCIAL RESOURCES

A contractor must have adequate financial resources to perform the contract or the ability to obtain

such resources. In making this evaluation, a non-state entity could analyze:

The existing cash flow of the contractor;

Account receivables; and

Other financial data.

49

TECHNICAL RESOURCES

A contractor must have or be able to acquire the required construction, production, and/or technical

facilities, equipment, and other resources to perform the work under the contract.

50

SUSPENSION AND DEBARMENT

Non-state entities, as well as state entities, must ensure the contractor is not suspended or

debarred.

51

NFEs must not make any award or permit any award at any tier to parties listed on the

government-wide exclusions in the System for Award Management (SAM), which can be found at

www.SAM.gov. All contracts must also include the suspension and debarment clause.

Example: Sealed Bidding and the Selection of Responsible Contractors

Scenario: Y Parrish is conducting a solicitation for new firetrucks under the Assistance

to Firefighters Grants Program. Using the sealed bidding method, Y Parrish received

49

2 C.F.R. § 200.318(h).

50

Id.

51

Id.; See also 2 C.F.R. § 200.214.

24

the lowest bid from Affordable Fire Vehicles, Inc. In conducting a responsibility determination, Y

Parrish found that Affordable Fire Vehicles, Inc. previously committed fraud in obtaining a contract

and does not have adequate financial resources to perform the required work within the new

contract. Is Y Parrish required to award the contract to Affordable Fire Vehicles, Inc. because it was

the lowest bid?

Answer: No. Pursuant to 2 C.F.R. § 200.318(h), a non-state entity is required to award contracts only

to responsible contractors possessing the ability to perform successfully under the terms and

conditions of a proposed procurement. In so doing, Y Parrish must look at contractor integrity,

compliance with public policy, record of past performance, and financial and technical resources.

Here the contractor’s integrity is at issue due to committing fraud previously. Moreover, Affordable

Fire Vehicles, Inc. does not have adequate financial resources to perform the required work. Y

Parrish must document its determination that Affordable Fire Vehicles, Inc. is not responsible and

must also document its basis for this determination.

Related Tools and Resources

Contract Provisions Guide

Suspension and Debarment FAQs

OMB Guidelines on Suspension and Debarment

Maintain Records

A non-state entity is required to maintain records sufficient to detail the history of a

procurement.

52

These records include, but are not limited to, the rationale for the

method of procurement, the selection of the contract type, the contractor selection or

rejection, and the basis for the contract price.

53

Additionally, the non-state entity’s records must also

include the contract document and any contract modifications with the signatures of all parties.

Contract documents pertinent to a Federal award must be retained for a period of three years from

the date of submission of the final expenditure report pursuant to 2 C.F.R. § 200.334

.