Georgetown University Law Center Georgetown University Law Center

Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW

2018

Interpretation and Construction in Contract Law Interpretation and Construction in Contract Law

Gregory Klass

Georgetown University Law Center

, gmk9@law.georgetown.edu

This paper can be downloaded free of charge from:

https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1947

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2913228

This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author.

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub

Part of the Contracts Commons

Interpretation and Construction in Contract Law

Gregory Klass

*

January 2018 - DRAFT

When faced with questions of contract interpretation, courts

commonly begin with the principle that “[t]he primary goal in interpreting

contracts is to determine and enforce the parties’ intent.”

1

The maxim

affirms that contractual obligations are chosen obligations. Parties acquire

them by voluntarily entering into agreements whose terms they control.

Contract interpretation therefore begins by seeking out the choices parties

made. The maxim is of a piece with a picture of contract as a form of

private legislation. Contract law gives parties the power to undertake new

legal obligations when they wish. That power requires giving parties the

obligations they intend. And the maxim serves to allocate responsibility.

When a court enforces a contract, it is not imposing an obligation on a

party, but merely giving effect to her own earlier choice. If a party is now

unhappy with the contract terms, she has only her earlier self to blame.

But of course contractual obligations are not only a matter of party

choice or intent. Sometimes when parties enter into the agreement, they do

not have or do not express an intent one way or another on some issues—

say whether the seller warrants the quality of the goods or the remedy for

breach. Thus the importance of default rules in contract law, which

determine parties’ contractual obligation in the absence of evidence of their

intent. Alternatively, the parties’ expressions of their intent might be

ambiguous. When this occurs, a court might apply a rule like contra

proferentem, interpreting against the drafter, or the preference for

*

Agnes N. Williams Research Professor, Professor of Law, Georgetown

University Law Center. I am grateful to John Mihail, Ralf Poscher and

especially Lawrence Solum for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

1

Old Kent Bank v. Sobczak, 243 Mich. App. 57, 63 (2000). A few other

examples: “The fundamental, neutral precept of contract interpretation is

that agreements are construed in accord with the parties’ intent.” Greenfield

v. Philles Records, Inc., 98 N.Y.2d 562, 569 (2002). “Under statutory rules

of contract interpretation, the mutual intention of the parties at the time the

contract is formed governs interpretation.” AIU Ins. Co. v. Superior Court,

51 Cal. 3d 807, 821 (1990) (citing Cal. Civ. Code § 1636). “The cardinal

rule for interpretation of contracts is to ascertain the intention of the parties

and to give effect to that intention, consistent with legal principles.” Bob

Pearsall Motors, Inc. v. Regal Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc., 521 S.W.2d 578,

580 (Tenn. 1975).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

2

interpretations in the public interest, neither of which looks to party intent.

There are also cases in which the parties’ intent is clear, but a court will

decline to give it legal effect. This is so when their agreement runs contrary

to a mandatory rule, such as minimum wage or civil rights laws, the penalty

rule, or the more general prohibition on enforcing agreements against

public policy. Courts also often apply interpretive rules that predictably

sometimes fail to capture what the parties actually intended. Plain meaning

rules, for example, exclude context evidence that can be essential for

understanding the parties’ intent. Finally, “the parties’ intent” is itself

ambiguous. Does it refer to parties’ intent with respect to their legal

obligations? Or does it refer only to their intended exchange, from which

those legal obligations flow?

In order to understand the relationship between parties’ expressions

of intent and their contractual obligations, one needs to distinguish two

activities: interpretation and construction. Interpretation identifies the

meaning of words or actions, construction their legal effect. Legal

interpretation employs linguistic and other social abilities that originate

outside the law. To live in a social world means to be constantly

interpreting the words and actions of others. We interpret what people say,

both expressly and by implication; the reasons for their actions; their beliefs

and their intentions. Legal interpretation engages those interpretive skills,

though it sometimes shackles them in one way or another. Rules of

construction, in distinction, originate in the law. Rules of construction

translate the output of interpretation into legal effects. Rules of construction

therefore govern the relationship between the ordinary and the legal

meanings of parties’ words and actions, or between the parties’ intent and

their contractual obligations.

Although the distinction between interpretation and construction is

easy to state in the abstract, a complete account of the two activities and

the relationship between the two is no easy thing—even if one restricts the

inquiry to interpretation and construction in contract law.

2

One reason is

that contract interpretation takes several different forms. Depending on the

details of the transaction and the legal question at issue, it might aim at the

plain meaning of the parties’ words, at those words’ contextually

determined use meaning, at subjective or at objective meaning, at an

agreement’s apparent purpose or purposes, or at what the parties believed

or intended. Rules of contract construction also come in several varieties.

They include the familiar categories of mandatory and default rules, as well

2

The interpretation-construction distinction has recently received

considerable attention from constitutional theorists, and especially

originalist. See, e.g., Lawrence B. Solum, The Interpretation-Construction

Distinction, 27 Const. Comment. 95 (2010); Randy Barnett, Interpretation

and Construction, 34 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 65 (2011); Jack M. Balkin, The

New Originalism and the Uses of History, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 641 (2013).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

3

as the less familiar category of altering rules—rules that govern when

parties words or actions suffice to contract out of a default legal state of

affairs. And while some altering rules require interpretation of the parties’

words and actions, others employ formalities that need no interpretation.

Finally, the relationship between the activities of interpretation and

construction is itself complex. In the order of application, interpretation

comes first, construction second. One must often interpret the parties’

words before one can determine their legal effect. But because legal

interpretation is always in the service of construction, the correct approach

to legal interpretation depends on the applicable rule of construction. And

rules of construction sometimes affect the meaning of what parties say—

both because acts of judicial construction can give words new conventional

legal meanings and because parties often intend their words to have certain

legal effects.

This Article provides a descriptive theory of interpretation and

construction in the law of contracts and the interplay between the two

activities.

3

Part One traces the history of the concepts in US law and legal

theory, which provides the basis for a clearer understanding of each. The

history focuses on three figures: Francis Lieber, Samuel Williston and Arthur

Linton Corbin. Tracing the development of the concepts of interpretation

and construction through these three authors suggests two different

conceptions of them. In both Lieber and Williston, one finds a

supplemental conception of interpretation and construction. For both,

construction appears only when interpretation either runs out due to gaps

or ambiguity or gaps or runs up against a higher-order rule. Corbin, in

distinction, articulates a complementary conception of the two activities.

According to Corbin, rules of construction apply throughout the process of

contract exposition, operating also in the absence of gaps or ambiguities.

Part One argues that the complementary conception provides the better

theoretical account of the two distinct activities.

Part Two provides a systematic account of the rules of contract

construction. Rules of construction include mandatory rules, default rules

and altering rules. Over the past thirty years, contract theorists have had

much to say about both mandatory and default rules. They have paid less

systematic attention to altering rules, which govern what it takes to change

3

Although Keith Rowley and Edwin Patterson each refer to the distinction

between interpretation and construction in the title of an article, those

works do not provide analyses of the distinction itself. See Keith A. Rowley,

Contract Construction and Interpretation: From the “Four Corners” to Parol

Evidence (and Everything in Between), 69 Miss. L.J. 73 (1999); Edwin W.

Patterson, The Interpretation and Construction of Contracts, 64 Colum. L.

Rev. 833 (1964).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

4

a default legal state of affairs.

4

Part Two describes the structure of contract

altering rules and provides a typology of them. Altering rules determine

among other things what types of meaning are legally salient, and thereby

also how the parties’ words and actions should be interpreted.

The description of altering rules provides the groundwork for Part

Three’s discussion of contract interpretation. The rules of contract

construction call on several different types of meaning. These include plain

meaning, use meaning, subjective meaning, objective meaning, purpose,

and belief and intent. The correct approach to contract interpretation differs

according to the facts of the case and the legal question at issue.

Part Four examines the interplay between interpretation and

construction. Because legal actors often take account of the law when

deciding what to say and do, interpreting their words and actions

sometimes requires understanding the rules of construction they mean to

satisfy or avoid. I term this the “pragmatic priority” of construction. Official

acts of construction can also give words or entire clauses technical

meanings, turning them into legal terms of art. This I call the “semantic

priority” of construction. Consequently, whereas interpretation typically

precedes construction in the order of exposition, there instances in which

the interpreter must know the legal rule of construction in order identify the

meaning of the parties’ words or actions. The law of contract is designed to

take advantage of this interplay.

Before proceeding further, a few words about method. This Article

is about the structure and content of legal rules. My interest is therefore in

the legally authorized activities of interpretation and construction. When I

say that interpretation precedes construction in the process of exposition, I

am saying something about the relevant legal rules. This is not to say that

parties, judges or other legal actors always play by those rules. Legal actors,

consciously or unconsciously, sometimes look to results before rules. And

the rules themselves are loose enough to allow some play at the joints. Thus

Corbin, ever the Legal Realist, observed:

Just as construction must begin with interpretation, we shall find

that our interpretation will vary with the construction that must

follow. Finding that one interpretation of the words will be followed

by the enforcement of certain legal effects, we may back hastily

away from that interpretation and substitute another that will lead to

a more desirable result.

5

4

The first attempt at a systematic account of altering rules can be found in

Ian Ayres, Regulating Opt-Out: An Economic Theory of Altering Rules, 121

Yale L.J. 2032 (2012).

5

Arthur Linton Corbin, 3 Corbin on Contracts: A Comprehensive Treatise

on the Rules of Contract Law § 534 at 11 (1951) (hereinafter “Corbin (1st

ed.)”). Eyal Zamir makes a similar point in The Inverted Hierarchy of

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

5

This is an enormously important point, not in the least because the ability to

substitute an interpretation that will lead to a more desirable result suggests

that meaning is, to some degree and in some cases, indeterminate. The

determinacy or indeterminacy of meaning has long been a topic of

discussion and disagreement among legal theorists.

6

And the degree to

which legal texts have stable, predictable and precise meanings is crucial to

the justification and critical appraisal of rules of construction that take one

or another form of meaning as their starting points.

That said, this Article is about the internal logic of legal rules that

assume that words and other legally relevant acts often have sufficiently

determinate meanings to bind future actors. From that point of view,

outcome driven forms of interpretation are ultra vires. They do not belong

to the internal logic of the law. This is not to say that they are not interesting

or important. Only that they are not my topic here.

1 The Interpretation-Construction Distinction

Like all concepts, the ideas of interpretation and construction have a

history. This Part traces the distinction from its origin in the work of Francis

Lieber to the first edition of Samuel Williston’s treatise, and then on to the

first edition of Arthur Linton Corbin’s treatise. That history shows a

movement from a supplemental conception of interpretation and

construction, according to which interpretation alone can answer some

legal questions, to a conception of the two activities as complementary,

according to which a rule of construction must always be applied to arrive

at a legal result. I argue that the complementary conception of the

distinction is the descriptively correct and more theoretically productive

one.

1.1 Francis Lieber

The interpretation-construction distinction is commonly traced to

Francis Lieber’s 1839 book, Legal and Political Hermeneutics, or Principles

of Interpretation and Construction in Law and Politics,

7

though Ralf Poscher

Contract Interpretation and Supplementation, 97 Colum. L. Rev. 1710

(1997).

6

See, e.g., Gary Peller, The Metaphysics of American Law, 73 Cal. L. Rev.

1151 (1985); Lawrence B. Solum, On the Indeterminacy Crisis: Critiquing

Critical Dogma, 54 U. Chi. L. Rev. 462 (1987).

7

Francis Lieber, Legal and Political Hermeneutics, or Principles of

Interpretation and Construction in Law and Politics (enlarged ed.

1839/1970). The book is a reworking and expansion of two articles that

appeared in The American Jurist in 1837 and 1838.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

6

has suggested that Lieber’s approach is rooted in Friedrich Schliermacher’s

earlier work on hermeneutics.

8

Lieber understands successful communication to be the

transmission of ideas from one person to another through the use of words

or other signs. Interpretation is the activity of discovering those ideas.

“Interpretation is the art of finding out the true sense of any form of words:

that is, the sense which their author intended to convey, and of enabling

others to derive from them the very same idea which the author intended to

convey.”

9

Lieber suggests that with respect to authoritative legal texts,

successful interpretation suffices to identify the text’s legal effect, which is

the effect intended by the authority that authored or authorized that text.

Although Lieber does not articulate a command theory of law, this account

of interpretation is consistent with one.

10

The correct interpretation of a

command identifies the intent of the authority who issued it—precisely how

Lieber describes the correct interpretation of a legal text.

Lieber observes that sometimes interpretation alone is not enough to

identify what the law is. In the course of Legal and Political Hermeneutics,

he identifies several situations in which the “true significance,” of a legal

text might not fully determine what the associated law is: (1) when the text

contains internal contradictions;

11

(2) “in cases which have not been

foreseen by framers of those rules, by which we are nevertheless obliged,

for some binding reason, faithfully to regulate, as well as we can, our

8

Ralf Poscher, The Hermeneutical Character of Legal Construction, in Law’s

Hermeneutics: Other Investigations 207, 207 (Simone Glanert and Fabien

Girard eds., 2017).

9

Lieber, supra note 7 at 23.

10

See H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law 18-25 (2d ed. 1994); H.L.A. Hart,

Commands and Authoritative Legal Reasons, in H.L.A. Hart, Essays on

Bentham: Studies in Jurisprudence and Political Theory 243-268 (1982).

11

Lieber, supra note 7 at 55-56. Today many theorists would also say that

construction is necessary when a legal text is ambiguous. Lieber’s intent-

based understanding of meaning, however, leads him to conclude that a

legal text cannot be ambiguous.

No sentence, or form of words, can have more than one ‘true

sense,’ and this only one we have to inquire for. . . . Every man or

body of persons, making use of words, does so, in order to convey a

certain meaning; and to find this precise meaning is the object of all

interpretation. To have two meanings in view is equivalent to

having no meaning—and amounts to absurdity. Even if a man use

words, from kindness or malice, in such a way, that they may signify

one or the other thing, according to the view of him to whom they

are addressed, the utterer’s meaning is not twofold; his meaning is

simply not to express his opinion.

Id. at 86.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

7

actions respecting the unforeseen case”;

12

and (3) when the simple meaning

of the text contravenes “more general and binding rules, [such as]

constitutional, written and solemnly acknowledged rules, or moral ones,

written in the heart of every man.”

13

In each of these instances,

interpretation alone cannot determine the legal outcome.

Lieber does not discuss contracts, but contract law includes rules

that address each of the situations Lieber identifies. The Mirror Image Rule

and section 2-207 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), for example,

each provides a rule to resolve potentially authoritative but conflicting

contractual texts. Under the Mirror Image Rule, the terms in last document

sent control (the “last shot rule”).

14

Under section 2-207, conflicting terms

drop out entirely and are replaced by Article Two’s default terms.

15

In

neither case does the rule turn on further interpretation of the meaning of

the parties’ words or intentions. Lieber’s second category, “cases which

have not been foreseen by the framers,” describes both situations that

trigger contractual defaults and the implied duty of good faith. Defaults

apply when a contractual agreement is silent on a subject—when, in effect,

the parties have not agreed on a relevant term.

16

The implied duty of good

faith constrains a party’s actions when a contractual agreement gives her

discretion or does not fully specify her obligations, often due to unforeseen

circumstances.

17

Finally, the doctrines of unconscionability and public

policy both generate cases in which a text’s legal effect is limited by “more

general and binding rules.”

18

In each of these situations interpretation alone fails to specify the

correct legal rule. We require supplemental rules or principles to determine

the legal state of affairs. Lieber terms these rules of “construction.”

12

Id. at 56.

13

Id. at 166. Or again: “But it is not said that interpretation is all that shall

guide us, and . . . there are considerations, which ought to induce us to

abandon interpretation, or with other words to sacrifice the direct meaning

of a text to considerations still weightier; especially not to slaughter justice,

the sovereign object of laws, to the law itself, the means of obtaining it.” Id.

at 115.

14

See E. Allan Farnsworth, Contracts § 3.21 (4th ed. 2004).

15

The above statement of the section 2-207 rule for different terms

oversimplifies, but is in the author’s opinion the best reading of this poorly

drafted statute. See 2 Anderson U.C.C. §§ 2-207:102 & 103 (3d. ed.). Other

readings of section 2-207 provide alternative rules of construction for cases

in which writings conflict.

16

See, e.g. U.C.C. §§ 312, 314 & 315 (implied warranties of title,

merchantability and fitness).

17

See Daniel Markovits, Good Faith as Contract Law’s Core Value, in

Philosophical Foundations of Contract Law 272 (G. Klass, et al. eds., 2014).

18

See Restatement (Second) of Contracts §§ 178-185, 208 (1981).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

8

In politics, construction signifies generally the supplying of

supposed or real imperfections, or insufficiencies of a text,

according to proper principles and rules. By insufficiency, we

understand, both imperfect provision for the cases, which might or

ought to have been provided for, and the inadequateness of the text

for cases which human wisdom could not foresee.

19

Construction is unavoidable because “[m]en who use words, even with the

best intent and great care as well as skill, cannot foresee all possible

complex cases, and if they could, they would be unable to provide for

them, for each complex case would require its own provision and rule.”

20

Construction for Lieber therefore serves a gap-filling and equitable

function. On Lieber’s theory, “interpretation precedes construction”

because construction steps in when interpretation runs out or runs up

against a higher-order legal rule or principle.

21

For this reason, Lieber also

sees a continuity of purpose between the two activities. “Construction is the

drawing of conclusions respecting subjects, that lie beyond the direct

expression of the text, from elements known from and given in the text—

conclusions which are in the spirit though not within the letter of the

text.”

22

This supplemental conception suggests that, at least when extending

a legal text to unforeseen cases, one should look for parallels covered

cases. “Construction is the building up with given elements, not the forcing

of extraneous matter into a text.”

23

That said, Lieber recognizes that to arrive

at the correct legal rule it is sometimes necessary to go beyond the “spirit”

of the text. This is so when construction is required to cure some injustice

in the law or conform it to a superior authority, as when a statute is

construed to conform to constitutional requirements.

24

The most interesting feature of Lieber’s theory for the analysis that

follows is this supplemental conception of interpretation and construction.

Lieber describes construction as operating only in what Larry Solum calls

the “construction zone”: “the zone of underdeterminacy in which

construction that goes beyond direct translation of semantic content into

19

Id. at 57.

20

Id. at 121.

21

“Since our object is to discover the sense of the words before us, we must

endeavor to arrive at it as much as possible from the words themselves, and

bring to our assistance extraneous principles, rules, or any other aid, in that

measure and degree, only as the strictest interpretation becomes difficult or

impossible, (interpretation precedes construction) otherwise interpretation is

liable to become predestined.” Id. at 113.

22

Id. at 56.

23

Id. at 124.

24

Id. at 58-59.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

9

legal content is required for application” of the rule.

25

According to Lieber’s

supplemental conception, construction steps in when interpretation fails to

determine the text’s legal effect.

26

1.2 Samuel Williston

It would be interesting to trace the influence of Lieber’s distinction

between interpretation and construction throughout the next century of

legal thought. Poscher suggests that it appears in somewhat different guise

in Friedrich von Savigny’s 1840 System of Modern Law.

27

William Story

employs the categories in his 1844 A Treatise on the Law of Contracts Not

under Seal, as does Theophilus Parsons in his 1855 Law of Contract.

28

Lieber’s distinction also appears in the 1868 first edition of Thomas

Cooley’s treatise on the US Constitution, the same year Lieber’s concepts

first appeared in John Bouvier’s legal dictionary.

29

James Bradley Thayer, in

his 1898 Treatise on Evidence, expressly declines to adopt the distinction,

arguing that “neither common usage nor practical convenience in legal

discussions support [it],” and the concepts do not appear in Wigmore’s

1905 or 1923 discussions of interpretation.

30

For my purposes, things

become interesting with the 1920 first edition of Samuel Williston’s The

Law of Contracts. In section 602, “Construction and interpretation,”

Williston makes what I view as two improvements on Lieber’s theory.

25

Solum, supra note 2 at 108 (2010) (internal punctuation omitted).

26

What I am calling the “supplemental conception” is akin to what Solum

calls the “Alternative Methods Model.” Lawrence B. Solum, Originalism and

Constitutional Construction, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 453, 498-99 (2013).

27

Poscher, supra note 8 at 207.

28

William W. Story, A Treatise on the Law of Contracts Not under Seal, §

228, at 148 (1844); 2 Theophilus Parsons, The Law of Contracts 3 n. a

(1855); 4 John Henry Wigmore, A Treatise on the System of Evidence in

Trials at Common Law, §§ 2458-2478 (1905); 5 John Henry Wigmore, A

Treatise on the Anglo-American Law of Evidence in Trials at Common Law,

§§ 2458-2478 (2d ed. 1924).

29

Thomas M. Cooley, Treatise on the Constitutional Limitations which Rest

upon the Legislative Power of the States of the American Union 89 n. 1

(1868); John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and

Laws of the United States of America 337 (12th ed. 1868).

30

James Bradley Thayer, A Preliminary Treatise on The Law of Evidence at

the Common Law 411 n. 2 (1898).

John Austin indicates something like Lieber’s distinction in his

Fragments, where he distinguishes between “[c]onsequences expressed by

parties, and consequences annexed by law in default of such expression.”

John Austin, Fragments—On Contracts, in Lectures on Jurisprudence, or

The Philosophy of Positive Law 939 (Robert Campbell ed., 4th ed. 1879).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

10

First, Williston suggests a narrower conception of construction. The

drawing of “conclusions that are in the spirit, though not in the letter of the

text,” Williston argues, is not different in kind from interpretation and

“seems of no legal consequence as far as the law of contracts is

concerned.”

31

For example, when a court reads a written agreement “as a

whole to determine its purpose and intent,”

32

it is engaging in a form of

interpretation, even when the result supplements or even supplants the

literal words in the agreement.

33

One must interpret an agreement to

determine its purpose and the parties’ likely intent. Better then, Williston

suggests, to limit “construction” to activities entirely distinct from

interpretation. For example, “when it is said that contracts which affect the

public are to be construed most favorably to the public interest, it is

obvious that the court is no longer applying a standard of interpretation,

that is it is not seeking the intention of the parties.”

34

Similarly when a

guarantee is interpreted in favor of the guarantor. Construction, for

Williston, is the category of rules whose function is not to realize or extend

the parties’ intentions, but that serve some other principle or purpose.

Although he advocates a narrower conception of construction,

Williston follows Lieber is in conceiving construction as supplemental to

interpretation. “[A] rule of construction can come into play only when the

primary standard of interpretation leaves the meaning of the contract

ambiguous.”

35

Construction again appears only when interpretation runs

out.

Williston’s second innovation is to suggest that neither

interpretation nor construction suffices to determine the legal state of affairs.

Each concerns itself “with the legal meaning of the contract, not with its

legal effect after that meaning has been discovered.”

36

The legal effect,

31

Samuel Williston, 2 The Law of Contracts § 602, 1160 (1920) (hereinafter

“Williston (1st ed.)”).

32

W.W.W. Assocs., Inc. v. Giancontieri, 77 N.Y.2d 157, 162 (1990).

33

See, e.g., McCoy v. Fahrney, 55 N.E. 61, 63 (Ill. 1899) (“Particular

expressions will not control where the whole tenor or purpose of the

instrument forbids a literal interpretation of the specific words.”).

34

Williston (1st ed.) at 1161.

Interestingly, Williston suggests that contra proferentem—the rule

that ambiguities are to be interpreted against the drafter—is a rule of

interpretation, “since it should be anticipated that the person addressed will

understand ambiguous language in the sense most favorable to himself, and

that his reasonable understanding should furnish the standard” Id. I would

say this is at best a majoritarian rule of construction, and better supported

by considerations of fairness and incentives than by the logic of

interpretation.

35

Id.

36

Id.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

11

Williston suggests, is a function of “substantive law of contracts which

comes into play after interpretation and construction have finished their

work.”

37

Williston served as the Reporter for the first Restatement of

Contracts, and a similar claim appears again in the comments to section

226: “Interpretation is not a determination of the legal effect of language.

When properly interpreted it may have no legal effect, as in the case of an

agreement for a penalty; or may have a legal effect differing from that in

terms agreed upon, as in the case of a common-law mortgage.”

38

Williston therefore distinguishes three activities: (1) interpretation,

which aims to get at the author’s intention; (2) a supplemental activity of

construction, which applies purely non-interpretive principles and steps in

when interpretation runs out, such as in cases of irresolvable vagueness or

ambiguity; and (3) the substantive law of contract, which specifies legal

effects based on the work of interpretation and construction.

1.3 Arthur Linton Corbin

Corbin’s 1951 treatise on contract law marks an important step

forward in understanding the activities of interpretation and construction.

Corbin provides the first clear account of construction as complementing,

rather than merely supplementing, interpretation. He describes

interpretation and construction as interlocking activities, each of which is

necessary to determine what the law is.

By “interpretation of language” we determine what ideas that

language induces in other persons. By “construction of the

contract,” as the term will be used here, we determine its legal

operation—its effect upon the action of courts and administrative

officials. If we make this distinction, then the construction of a

contract starts with the interpretation of its language but does not

end with it; while the process of interpretation stops wholly short of

a determination of the legal relations of the parties.

39

37

Id.

38

Restatement of Contracts §§ 226 cmt. c (1932).

39

Corbin (1st ed.) § 534 at 7. Those interested in the development of

Corbin’s thoughts on the interpretation-construction distinction should

begin with a passage he added on the subject as editor the 1919 third

American Edition of Anson’s Principles of the Law of Contracts. William

Reynell Anson, Principles of the Law of Contract: With a Chapter on the

Law of Agency, 14th English ed., 3rd American ed. § 353, 405-06 (Arthur L.

Corbin ed. 1919) (reprinted in Arthur L. Corbin, Conditions in the Law of

Contract, 28 Yale L.J. 739, 740-41 (1919)).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

12

Whereas Williston distinguished between, on the one hand, legal rules that

resolve ambiguities or fill gaps and, on the other, rules that determine the

legal effect of an unambiguous text or other speech act, Corbin recognizes

that those two activities are not different in kind. Both determine the legal

effect of what the parties said and did, including what they did not say or

do. Both should therefore be classified as rules of construction.

This more expansive view of construction—the activity of

determining the legal effect of a legal actor’s words and actions—allows

Corbin to view construction as complementing, rather than supplementing,

interpretation.

40

Both Lieber and Williston conceived of construction as

stepping in only when interpretation runs out. Corbin suggests that

determining the parties’ contractual obligation always requires a rule of

construction.

41

“[T]he process of interpretation stops wholly sort of a

determination of the legal relations of the parties,” because interpretation

tells us only what some persons said, meant or intended. We require a rule

of construction, or what H.L.A. Hart called a “rule of change,”

42

to

determine which sayings or meanings or intendings of what legal actors

have what legal effects.

Suppose, for example, an unemancipated minor and an adult each

signs an identical enforceable agreement, each clearly evincing her

intention that it be binding. Under US law, only the adult thereby acquires

a nonvoidable contractual obligation.

43

The agreements and signatures have

the same meaning; but meaning alone does not determine legal effect. That

requires a rule of construction. Here the relevant rule provides that the

adult’s signature results in a nonvoidable contractual obligation, whereas

the same act done by a minor creates an obligation that the minor can later

disclaim. Rules of construction determine not only unintended legal

consequences, as Lieber and Williston maintain, but also intended ones.

This broader conception of construction casts new light on the

maxim that the primary goal of contract interpretation is to ascertain the

parties’ intent.

44

Although often treated as a rule of interpretation, the rule is

in fact one of construction. It says that when adjudicators are determining

contracting parties’ legal obligations, they should look first to evidence of

the parties’ shared intentions. Generally speaking and ceteris paribus,

contract law enforces the agreement that the parties intended. Such a rule is

a rule of construction.

40

What I am calling the “complementary conception” of interpretation and

construction is similar to what Solum calls the “Two Moments Model.”

Solum, Constitutional Construction, supra note 26 at 498-99.

41

Thus Corbin could expressly reject Lieber’s account of interpretation and

construction. Corbin (1st ed.) § 534, at 11, n.11.

42

Hart, The Concept of Law, supra note 10 at 95-96.

43

See Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 14 (1981).

44

See supra note 1

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

13

But that is only generally speaking. When parties have

memorialized their agreement in an integrated writing, for example, their

contractual rights and obligations might turn on the writing’s plain

meaning, even if one or both parties had a different understanding of its

content. And other rules of construction—the ones Lieber and Williston

emphasize, and that Corbin also discusses—hew even less closely to the

parties’ expressed intent. Examples include generic rules of construction

like contra proferentem and the rule favoring interpretations that accord

with public policy. Also in this category are the many default rules that

determine parties’ legal obligations absent their contrary expression, as well

as mandatory rules that parties cannot contract out of, such as the duty of

good faith. The rules of contract construction also include rules that deny

enforcement based on the substance of an agreement, such as the rules for

illegal agreements or the unconscionability doctrine. These and other extra-

interpretive rules of construction apply when the object of interpretation is

ambiguous, contradictory or gappy, when the situation is one that we

believe lawmakers did not foresee, or when the text’s meaning or parties’

intent contravenes a higher legal authority or principle.

The important point, however, is Corbin’s recognition that a text’s

meaning never suffices to determine its legal effect. Even when the text

appears to fully determine the legal rule, it does so only by virtue of a rule

of construction. Construction does not supplement interpretation, but

complements it.

1.4 Interpretation and Construction

Corbin’s complementary conception of interpretation and

construction can be restated as follows: interpretation identifies the

meaning of some words or actions, construction their legal effect. Rules of

interpretation are used to discern the meaning of what parties say and do;

rules of construction determine the resulting legal state of affairs.

One might think of rules of interpretation and rules of construction

as two types of functions. A rule of interpretation takes as its input some

domain of interpretive evidence. That evidence necessarily includes the act

or omission whose meaning is at issue, which I will call the “interpretive

object,” as well as the interpreter’s background linguistic and practical

knowledge. Depending on the rule being applied, the interpretive input in a

contract case might also include dictionary definitions and rules of syntax,

testimony or other evidence of local linguistic practices, what was said

during negotiations, any course of performance under the agreement at

issue, any prior similar transactions between the parties, testimony as to

how participants in the transaction meant or understood the interpretive

object, evidence of the parties’ reasons or motives for entering into the

exchange, and so forth. A rule of interpretation maps that input onto a

meaning, which interpretation ascribes to the interpretive object.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

14

The output of legal interpretation—the meaning ascribed to the

interpretive object—serves as an input for construction. Construction might

take other input as well. A rule of contract construction might, for example,

condition legal effects not only on what the speaker says—the meaning of

her words and actions—but also on who she is, on the form in which she

expresses herself, or on her use of conventional words or acts. And as will

be discussed below, sometimes rule of construction requires no

interpretation, as when parties employ a formality. A rule of construction

maps those inputs onto a legal state of affairs. That is, it identifies their legal

effect.

I will use “exposition” to refer to the entire process of determining

the legal effect of a person or persons’ words or actions. Exposition

commonly involves both interpretation and construction. In the process of

exposition, interpretation comes first, construction second. The reason is

not, as Lieber and Williston suggest, that construction steps in only when

interpretation runs out. It is that one generally must decide what words or

actions mean before one can know their legal effects. As Corbin says, “A

‘meaning’ must be given to the words before determining their legal

operation.”

45

Or as I have put the point, the output of legal interpretation

serves as the input for construction. That said, later parts of this Article

identify other senses in which construction is sometimes or always prior to

interpretation.

Although the interpretation-construction distinction has been

around for over a century and a half, it is often ignored. Many contract

scholars use “interpretation” to refer to the activity of construction. Ian

Ayres: “Algebraically, one could think of interpretation as a function, f(),

that relates actions of contractual parties, a, and the surrounding

circumstances or contexts, c, to particular legal effects, e.”

46

Richard

Posner: “Contract interpretation is the undertaking . . . to figure out what

the terms of a contract are, or should be understood to be.”

47

Alan Schwartz

and Robert Scott: “[A] theory of interpretation . . . ‘maps’ from the semantic

content of the parties' writing to the writing's legal implications.”

48

Contrariwise, and especially among British jurists and scholars, it is not

uncommon to use “construction” to refer to the search for objective

meaning, which is a form of interpretation as I am using the term.

49

45

Corbin (1st ed.) § 534, 8.

46

Ayres, supra note 4 at 2046.

47

Richard A. Posner, The Law and Economics of Contract Interpretation, 83

Tex. L. Rev. 1581, 1582 (2005)

48

Alan Schwartz & Robert E. Scott, Contract Theory and the Limits of

Contract Law, 113 Yale L.J. 541, 547 (2003).

49

For example, in his treatise, The Construction of Commercial Contracts,

J.W. Carter defines “construction” as “the process by which the intention of

the parties to a contract is determined and given effect to,” and argues that

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

15

These façons de parler are fine as far as they go. The technical

definitions of “interpretation” and “construction” depart from those words’

everyday meanings, and there is nothing wrong with using common words

in accordance with common usage. But there is a difference between the

activities of interpretation and construction. Corbin again: “there is no

identity nor much similarity between the process of giving a meaning to

words, and the determination by the court of their legal operation.”

50

Attention to the difference, and to the different rules that govern each

activity, is essential to a clear understanding of how law translates words

and actions into legal effects. The advantage of adhering to the terms’

technical meanings is that it forces one to keep in view the difference

between the two activities, and to be clear about what one is talking about

when.

2 Rules of Contract Construction

Having distinguished the activities of interpretation and

construction, it is now possible to take a closer look at the rules that govern

each. This Part provides an account of the rules of contract construction;

Part Three discusses varieties of contract interpretation.

The rules of contract construction divide into three broad

categories: mandatory rules, default rules and altering rules. A mandatory

rule specifies a legal state of affairs that applies no matter what legal actors

say and do. Thus when the Second Restatement observes that “[e]very

contract imposes upon each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its

performance and its enforcement,” it states that the parties who have

entered into a contract have a duty of good faith no matter what.

51

The duty

cannot be disclaimed. Other examples include the minimum wage and

civil rights laws, the penalty rule for liquidated damages, and the

nonenforcement of contracts contrary to public policy. A default rule

specifies the legal state of affairs absent evidence the right person’s or

persons’ contrary intent. Familiar examples in contract law include the rule

that an offer on which the offeree has not relied is revocable;

52

the implied

“since even a decision on the linguistic meaning of words may determine

the legal rights of the parties, there seems little point in seeking to

distinguish between a process called ‘interpretation’ and one which is

termed ‘construction.’” J.W. Carter, The Construction of Commercial

Contracts 4 & 6 (2013).

50

3 Corbin (1st ed.) § 534, 11.

51

Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 205 (1981). This is not to say that the

parties cannot alter the specific requirements of that obligation through

their words and actions. The point is only that they cannot escape the duty

altogether.

52

See Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 42 cmt. a (1981).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

16

warranty of merchantability that attaches to a merchant’s sale of goods;

53

and most rules governing the calculation of damages for breach.

54

An

altering rule specifies whose saying of what suffices to effect one or another

change from the default legal state of affairs.

55

Thus a merchant selling

goods can make her offer irrevocable for up to three months by expressing

her intent to do so in a signed writing;

56

a seller can disclaim the implied

warranty of merchantability by using words like “as is” or “with all faults”;

57

and parties can generally agree to liquidate or limit damages for breach by

expressing their shared intent to do so.

58

This Part focuses on default and altering rules, which together

translate parties’ words and actions into contractual obligations.

2.1 Default Rules

Contract scholars often speak of default rules as “rules of

interpretation,” and commonly use terms like “default interpretations” or

“interpretive defaults.”

59

One reason for this way of speaking is inattention

to the interpretation-construction distinction. The inattention is fine so long

as everyone is clear that “interpretation” is being used to include

construction. If one attends to the difference between the two activities, it is

clear that default rules are rules of construction. A default rule determines

the legal state of affairs absent the parties’ expression to the contrary. As

Corbin observes, “[w]hen a court is filling gaps in the terms of an

agreement, with respect to matters that the parties did not have in

contemplation and as to which they had no intention to be expressed, the

judicial process . . . . may be called ‘construction’; it should not be called

‘interpretation.’”

60

Another reason why contract scholars might associate defaults with

rules of interpretation is that defaults rules are often designed to get at what

53

U.C.C. § 2-314(1).

54

See Restatement (Second) of Contracts §§ 346-52 (1981).

55

I take this term from Ian Ayres’s important work, Regulating Opt-Out: An

Economic Theory of Altering Rules, 121 Yale L.J. 2032 (2012). See also Brett

McDonnell, Sticky Defaults and Altering Rules in Corporate Law, 60 SMU

L. Rev. 383 (2007). In earlier work, I have analyzed altering rules under the

heading of “opt-out” rules. Gregory Klass, Intent to Contract, 95 Va. L. Rev.

1437 (2009).

56

U.C.C. § 2-205.

57

U.C.C. § 2-316(3)(a).

58

Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 356 (1981).

59

A search of Westlaw’s JLR database finds 85 articles using “default

interpretation,” 88 using “interpretive default,” and 52 using “default rule of

interpretation.” Search run on January 2, 2018.

60

3 Corbin (1st ed.) § 534 at 9.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

17

parties probably intended, or would have intended had they thought about

the matter, and these can look like interpretive questions. Thus Richard

Posner writes: “Gap filling and disambiguation are both . . . ‘interpretive’ in

the sense that they are efforts to determine how the parties would have

resolved the issue that has arisen had they foreseen it when they negotiated

their contract.”

61

I do not want to claim a monopoly on the word “interpretation.” But

neither setting a majoritarian default nor seeking what particular parties

would have agreed to requires interpretation in the sense in which this

Article uses the term. Predicting parties’ probable preferences or intentions

is not the same as interpreting what individual parties said or did in a

particular transaction.

62

Moreover, not all default rules are or should be

majoritarian ones or correspond to what the parties would have agreed to.

63

Lawmakers might set the default to accord with public policy or other

social interests as a way to guide parties to socially desirable outcomes. Or

they might adopt a penalty default that is designed not to get at the terms

most parties want or would have chosen, but to give one or both parties a

new reason to share information by opting out of the default.

The above paragraphs barely scratch the surface of the extensive

literature on default rules in contract law. This Article’s primary

contribution to that literature is simply to clarify how one should

understand of default rules. Default rules are not rules of interpretation, but

rules of construction. Once one recognizes this fact, it is not surprising that

they might be designed with a view to factors other than parties’ probable

intentions or hypothetical agreement. The social interests in the

enforcement contractual agreements extend beyond party choice.

2.2 Altering Rules

Every default comes with an altering rule. To describe a legal state

of affairs as a default is to say that some person or persons might change it

by saying the right thing in the right way. Who must say what how is

determined by an altering rule. As Ian Ayres writes, “[a]n altering rule in

essence says that if contractors say or do this, they will achieve a particular

61

Posner, supra note 47 at 1586.

62

For a variation on this point, see Seana Valentine Shiffrin, Must I Mean

What You Think I Should Have Said?, 98 Va. L. Rev. 159, 163 (2012);

Gregory Klass, To Perform or Pay Damages, 98 Va. L. Rev. 143, 145-47

(2012).

63

Ian Ayres & Robert Gertner, Filling Gaps in Incomplete Contracts: An

Economic Theory of Default Rules, 99 Yale L.J. 87 (1989).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

18

contractual result.”

64

Because altering rules describe the legal effects of

what parties say and do, they too are rules of construction.

All altering rules share a tripartite structure specifying actor, act and

effect. An altering rule provides that if (1) the right actor or actors (2)

performs a specified act, then (3) a certain nondefault legal state of affairs

will pertain. Article Two’s rule for firm offers not supported by

consideration provides a useful example. The default rule for offers is that

they are revocable. Section 2-205 provides an associated altering rule:

An offer by a merchant to buy or sell goods in a signed writing

which by its terms gives assurance that it will be held open is not

revocable, for lack of consideration, during the time stated or if no

time is stated for a reasonable time, but in no event may such

period of irrevocability exceed three months.

The rule establishes (1) whose acts are relevant: those of a merchant buyer

or seller of goods; (2) what acts are sufficient to displace the default: a

signed written assurance that the offer will be held open; and (3) the term

that substitutes for the default: irrevocability for the time stated or, if no time

is stated, for a reasonable time, but in no case for more than three months.

This Article focuses on the second element of altering rules: the

identification of acts that suffice to displace the default. I call these “altering

acts.”

Altering acts can have multiple salient features. Consider again the

section 2-205 rule for firm offers. In order to be irrevocable under the rule,

a merchant’s offer must satisfy three requirements. It must (a) “by its terms

give[] assurance that it will be held open,” (b) be in writing, and (c) be

signed. Determining whether the first requirement is met—whether the right

sort of assurance was given—requires interpretation, even if only to

ascertain the literal meaning of the merchant’s words. Determining whether

the second and third requirements are satisfied—whether the assurance was

in writing and whether it was signed—does not require interpretation. The

first requirement is that the offer perform an act with the right meaning, the

second and third that the act be of the right form.

I will call rules that condition legal outcomes on the meaning of

what the parties say and do “interpretive components” of altering rules, and

rules that condition legal outcomes on facts that can be ascertained without

64

Ayres, supra note 4 at 2036. I do not think that Ayres gets things quite

right when he writes that altering rules are “the necessary and sufficient

conditions for displacing a default legal treatment with some particular

other legal treatment.” Id. at 2036. It is more helpful to think of altering

rules as specifying acts sufficient to displace a default, but not necessary to

do so. Contract law often provides several separate paths to effecting a legal

change.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

19

interpretation “formal components.” An interpretive component requires

interpretation of the parties’ words and actions to determine whether they

have effected a legal change. A formal component requires examination of

formal qualities of the parties’ words and actions.

Any given altering rule might have only interpretive components,

only formal components, or a mix of the two. I will say that an altering rule

that includes only formal components is “formalistic,” and the altering acts

such a rule specifies “formalities.” Consider section 2-319 of the Code,

which provides that, “when the term is F.O.B. the place of shipment, the

seller must at that place ship the goods in the manner provided in this

Article . . . and bear the expense and risk of putting them into the

possession of the carrier.” According to this rule, the letters “F.O.B.” plus

the name of a place suffice to effect the legal change. No further inquiry

into what the parties or their words meant is required. The rule is a

formalistic one, establishing “F.O.B.” as a legal formality. The section 2-316

rule for “as is” and “with all faults” is similarly formalistic. It provides that,

ceteris paribus, the mere use of those words is enough to exclude all

implied warranties. So too, famously, the common law and statutory rules

governing the legal effect of the seal.

65

I will say that altering rules that are not formalistic are “interpretive.”

Interpretive altering rules always contain an interpretive component. The

application of an interpretive altering rule requires interpretation of the

parties’ words and actions. Interpretation enters the process of legal

exposition by way of interpretive altering rules.

An interpretive altering rule might or might not include formal

components. I will call altering rules that do not include formal

components “pure interpretive altering rules.” The Second Restatement

defines an offer, for example, as any “manifestation of willingness to enter

into a bargain.”

66

The rule requires interpretation of a party’s words and

actions to determine whether there has been an offer. But it does not

condition the legal effect of those words or actions on their formal qualities,

such appearing in a writing or with a signature. Similarly, UCC section

65

Altering rules can specify legal effects that are either defeasible or non-

defeasible, depending on whether the resultant legal state of affairs is

default or mandatory. Most modern formalistic altering rules establish

defeasible effects. The Second Restatement, for example, provides that

“[t]he adoption of a seal may be shown or negated by any relevant

evidence as to the intention manifested by the promisor.” Restatement

(Second) Contracts § 98 cmt. a (1981). See also 1 Williston on Contracts

§ 2:2 n.11 (4th ed. 2016) (citing cases); Eric Mills Holmes, Stature & Status

of a Promise Under Seal as a Legal Formality, 29 Willamette L. Rev. 617,

636-37 (1993) (discussing the modern requirement of a party’s intent to

deliver the sealed instrument).

66

Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 24 (1981).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

20

2-204’s formation rule: “A contract for sale of goods may be made in any

manner sufficient to show agreement, including conduct by both parties

which recognizes the existence of such a contract.”

67

Determining whether

the parties have agreed to a sale of goods requires interpreting their words

and conduct. The rule is an interpretive one. Because section 2-204 does

not impose any formal requirements, it too is a pure interpretive altering

rule.

68

I will call interpretive altering rules that that have one or more

formal components “mixed interpretive rules.” The section 2-205 rule for

firm offers is a mixed interpretive rule. It requires both that a merchant

seller say words with the right meaning—that the offer “by its terms gives

assurances that it will be held open”—and that those words be in the right

form—“in a signed writing.” A merchant’s offer must satisfy both the

interpretive and the formal components to be a firm offer pursuant to the

rule.

The distinction between formal and informal components therefore

produces a typology of altering rules that can be represented in a two-by-

two table.

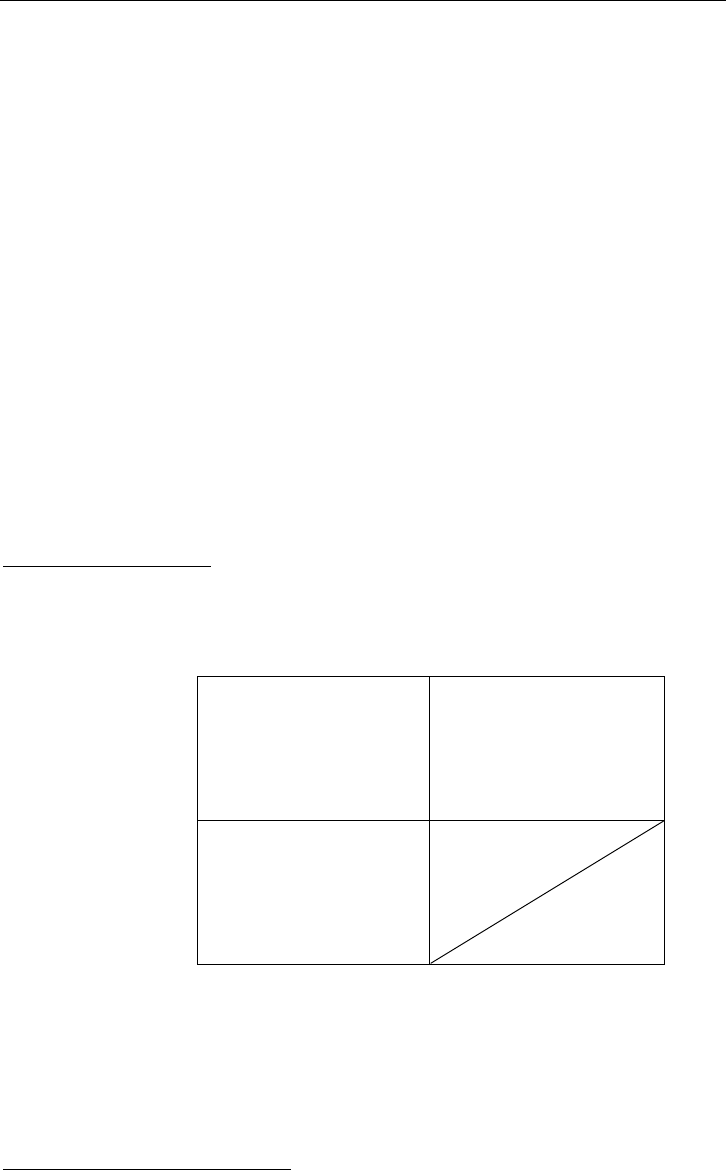

Types of altering rules

Interpretive Component

Yes

No

Formal

Component

Yes

mixed

interpretive rules

(UCC rule for firm

offers)

formalistic rules

(“as is,” “F.O.B.”)

No

pure

interpretive rules

(generic rules for

agreement)

Part Three discusses interpretive altering rules. Formalistic altering rules

figure into the discussion of Part Four.

Lastly, it is worth nothing that altering rules themselves can be

mandatory or default rules. Contract law grants parties broad powers not

only over their first-order legal obligations to one another—roughly, the

67

U.C.C. § 2-204.

68

Other sections of the code add formal requirements for some contract

types, most obviously the Code’s Statute of Frauds. U.C.C. § 2-201.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

21

obligations whose nonperformance constitutes a breach

69

—but sometimes

also over the framework rules that determine when those obligations come

into existence and what their content is.

The mailbox rule provides a simple example. The rule establishes

precisely when an acceptance effects a legal change, and is therefore a

component of the effects-prong of formation altering rules. A mailed

acceptance is effective “as soon as it is put out of the offeree’s possession,

without regard to whether it ever reaches the offeror.”

70

That rule, however,

does not apply if “the offer provides otherwise.”

71

The mailbox rule itself is

a default rule. An offeror has the power to stipulate, for example, that an

acceptance shall be effective only upon receipt.

The parol evidence rule provides another, somewhat more complex,

example. The contemporary default rule is that writings are given no special

weight in determining parties’ contractual obligations.

72

If, however, parties

agree that a writing shall serve as a final expression of some or all of the

contract between them—that the writing shall be “integrated”—parol

evidence of contrary or additional terms is generally excluded.

73

Integration

alters the default legal effects of the writing and of extrinsic evidence. U.S.

courts generally recognize two ways parties can effectively express or

evince their shared intent that a writing be integrated. They can include in

the writing an integration clause, which expressly states that it is the final

statement of some or all terms. Or, absent an integration clause, a writing

will be judged integrated if “in view of its completeness and specificity

reasonably appears to be a complete agreement, it is taken to be an

integrated agreement.”

74

These are altering rules. Each specifies how parties

can effectively express their intent that the writing serve as a final statement

of terms.

Although many rules of construction are defaults, there are also

mandatory limits on the parties’ ability pick and choose those rules. A

clause that requires modifications to be in writing might be ineffective

69

In addition to first-order duties, a contract might provide for first-order

permissions, powers and other legal relations. Here and in much of the rest

of this essay, for the sake of simplicity I ignore these other types of contract

terms.

70

Restatement (Second) Contracts § 63 (1981).

71

Id.

72

This was not always the case. Under the old best evidence rule, a writing

automatically excluded all oral evidence of contrary terms. The best

evidence rule established an evidentiary hierarchy: written evidence, which

was commonly under seal, could not be contradicted by oral evidence.

See, e.g., Salmond, The Superiority of Written Evidence, 6 L. Q. Rev. 75

(1890).

73

Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 213 (1981).

74

Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 209(3) (1981).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

22

under common law, though effective under the Uniform Commercial

Code.

75

Courts do not enforce provisions that purport to alter the rules

governing waivers.

76

And integration will not prevent a party from later

introducing parol evidence of “illegality, fraud, duress, mistake, lack of

consideration, or other invalidating cause.”

77

* * *

The analysis so far can be summarized as follows. Legal exposition

involves two separate activities: interpretation, which identifies the meaning

of the parties’ words and actions, and construction, which identifies their

legal effect. Rules of construction include mandatory, default and altering

rules. A mandatory rule says what the legal state of affairs is no matter what

the parties say or do. A default rule says what the legal state of affairs is

absent the parties’ contrary expression. An altering rule identifies contrary

expressions sufficient to effect a change from the default. Altering rules can

have interpretive and formal components. Interpretive components

condition legal change on the performance of acts with the right meaning.

Formal components condition legal change on the performance of acts of

the right form. Formalistic altering rules have only formal components. Pure

interpretive rules have only interpretive components. Mixed interpretive

rules have both formal and interpretive components.

Conceptual distinctions and taxonomies are of value when they

shed new light on old questions. The argument for the above categories can

therefore be found in the remainder of this Article. That said, it is already

possible to identify an example of their utility. Eric Posner has suggested

that “[a]n interesting aspect of the Statute of Frauds and other contract

formalities is that they do not fit easily into the default-immutable rule

dichotomy frequently used by contract theorists.”

78

The reason is that the

default-immutable rule, or default-mandatory rule, dichotomy is

incomplete. Statutes of Frauds and other formal requirements belong to a

third category: altering rules. A writing requirement like a Statute of Frauds

is not itself an altering rule, but is sometimes a component of other altering

75

See Samuel Williston, 29 Williston on Contracts § 73:22 (4th ed.) (no-

oral-modification clauses ineffective); U.C.C. 2-209(2) (no-oral-

modification clauses effective).

76

See 13 Williston on Contracts § 39:36 (4th ed.) (“[A] provision that a term

or condition of any sort cannot be eliminated by a waiver, or by an

estoppel, is ineffective, and a party has the same power to waive the

condition, or to be estopped from asserting it, as though the provision did

not exist.”).

77

Restatement (Second) Contracts § 214(d) (1981).

78

Eric A. Posner, Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: A

Comment, 144 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1971, 1981 (1996).

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

23

rules. In the transactions to which it applies, a Statute of Frauds adds a

formal component: the parties’ agreement must be evidenced by a signed

writing.

79

Altering rules and their components, like any other framework

contract rules, can themselves be mandatory or default. As it happens,

Statutes of Frauds are mandatory components of the altering rules into

which they figure. Parties cannot contract out of their writing requirements.

Although a complete understanding of such formal requirements demands a

richer conceptual toolkit, a Statute of Frauds therefore also fits “into the

default-immutable rule dichotomy.”

3 The Varieties of Contract Interpretation

Part One emphasized differences among how Lieber, Williston and

Corbin conceive interpretation and construction and the relationship

between the two activities. But there is a similarity among their

understandings of interpretation. Each has a relatively narrow conception of

meaning. For Lieber, “[t]rue sense is . . . the meaning which the person or

persons, who made use of the words, intended to convey to others, whether

he used them correctly, skillfully, logically or not.”

80

Williston follows

Lieber’s intentionalist account: “Interpretation is the art of finding out the

true sense of any form of words: that is, the sense which their author

intended to convey, and of enabling others to derive from them the very

same idea which the author intended to convey.”

81

Corbin adopts a listener-

centered account of meaning, but one that is similarly one-dimensional.

“By ‘interpretation of language’ we determine what ideas that language

induces in other persons.”

82

These simple accounts of meaning, and by extension interpretation,

oversimplify. This Part argues that contract law’s interpretive altering rules

recognize and give legal effect to several different types of meaning.

83

These

79

This is roughly the basic requirement of Article Two’s writing

requirement. U.C.C. § 2-201(1). The rule in section 2-201 of the Code

contains exceptions and qualifications that are not captured in the above.

And other Statutes of Frauds require additional things of the writing. The

Second Restatement, for example, suggests that the contents of the writing

must (1) reasonably identify the subject matter of the contract; (2) indicate

that a contract has been made; and (3) state the essential terms of the

unperformed promise. Restatement (Second) Contracts § 131 (1981).

80

Lieber, supra note 7 at 23. See also id. at 19 (“[I]t is necessary for him, for

whose benefit [a sign] is intended, to find out, what those persons who use

the sign, intend to convey to the mind of the beholder or hearer.”).

81

Williston (1st ed.) § 602, at 1159-60 (quoting Lieber, supra note 7 at 23).

82

Corbin (1st ed.) § 534, at 7.

83

Lieber expressly rejects the idea that there are multiple types of meaning

relevant to the law, contrasting legal to Biblical interpretation.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

24

include plain meaning, context dependent use meaning, subjective and

objective meaning, an agreement’s or term’s purpose, and the parties’

intentions and beliefs. Each can, under the right circumstances, figure into

determining the existence or content of a contract. Each is identified by

interpretation of the parties’ words and actions. And the legal relevance of

each is determined by a rule of construction.

Two scholars have recently suggested that public laws too have

multiple meanings. Cass Sunstein argues that “there is nothing that

interpretation ‘just is,’” and that “no approach to constitutional

interpretation is mandatory.”

84

And Richard Fallon identifies a “diversity of

senses of meaning that constitute . . . potential ‘referents’ for claims of legal

meaning.”

85

Sunstein suggests an outcome-based approach the choice

among interpretive methods in constitutional law. “Among the reasonable

alternatives, any particular approach to the Constitution must be defended

on the ground that it makes the relevant constitutional order better rather

than worse.”

86

To date Sunstein he has not made an outcome-based case for

one or another form of constitutional interpretation. Fallon argues that it is a

mistake to equate statutory or constitutional meaning with any one type of

meaning. Rather than selecting a single mode of interpretation on the basis

of overall outcomes, Fallon recommends “a relatively case-by-case

approach to selecting” the appropriate sort of meaning.

87

Neither Sunstein’s nor Fallon’s theory describes the choice of

meaning in the law of contracts. In contract exposition, different types of

meaning are relevant in different circumstance and to different legal

questions. And generally accepted rules of construction govern which type

of meaning is legally relevant when. Contract law thereby illustrates how

legal exposition can incorporate multiple types of meaning in a rule-

Owing to the peculiar character which the Bible possesses, as a

book of history and revelation, and the relation between the old and

new testaments, we find that some divines ascribe various meanings

to the same passages or rites, and that different theologians take the

same passage in senses of an essentially different character. We hear

thus of typical, allegorical, parabolical, anagogical, moral and

accommodatory senses, and of corresponding modes of

interpretation. . . . In politics and law we have to deal with plain

words and human use of them only.

Lieber, supra note 7 at 75-76.

84

Cass Sunstein, There Is Nothing that Interpretation Just Is, 30 Const.

Comment. 193, 193 (2015).

85

Richard H. Fallon, Jr., The Meaning of Legal “Meaning” and Its

Implications for Theories of Legal Interpretation, 82 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1235,

1239 (2015).

86

Sunstein, supra note 84 at 212.

87

Fallon, surpra note 85 at 1303.

Klass: Interpretation and Construction

Last printed 1/16/18 4:03 PM

25

governed way. And it exemplifies how what counts as the right approach to

legal interpretation depends on the relevant rule of construction, as the

complementary conception suggests it must.

This Part focuses on the interpretation of contractual agreements.

But it is worth remembering that agreements are not the only types of

altering acts that contract law recognizes. Offers, rejections, counter offers,

retractions, preliminary agreements, modifications, waivers, repudiations,

demands for adequate assurance, cancellations, elections of remedies and

other meaningful acts before and after formation can alter the parties’

contractual rights, obligations, powers, privileges and so forth. All of

commonly require interpretation to determine their legal effect. This Part

makes only a start at describing the varieties of interpretation in contract

law.

3.1 Plain Meaning and Use Meaning

Perhaps the most contested question about contract interpretation

concerns the choice between plain meaning and use meaning. In contract

law, “plain meaning” generally refers to the meaning an experienced

interpreter can glean from a writing using nothing but a dictionary, her

knowledge of the English language, and her generic understanding of the

social world. Because plain meaning interpretation uses so few inputs, a

writing’s plain meaning often is its literal meaning. But not always. A

written agreement read as a whole, for example, might evince a general

purpose which suggests that a provision in it should not be read literally. As

Williston explained in the first edition of his treatise:

in giving effect to the general meaning of a writing particular words

are sometimes wholly disregarded, or supplied. Thus “or” may be

given the meaning of “and,” or vice versa, if the remainder of the