fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 1

TYPE Original Research

PUBLISHED 08 February 2023

DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

OPEN ACCESS

EDITED BY

Wenting Feng,

Hainan University, China

REVIEWED BY

Chenhan Ruan,

Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, China

Lei Zheng,

Fuzhou University, China

*CORRESPONDENCE

Nan Zhang

SPECIALTY SECTION

This article was submitted to

Human-Media Interaction,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Psychology

RECEIVED 15 December 2022

ACCEPTED 16 January 2023

PUBLISHED 08 February 2023

CITATION

Zhang N (2023) Product presentation

in the live-streaming context: The effect

of consumer perceived product value and time

pressure on consumer’s purchase intention.

Front. Psychol. 14:1124675.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

COPYRIGHT

© 2023 Zhang. This is an open-access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use,

distribution or reproduction in other forums is

permitted, provided the original author(s) and

the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the

original publication in this journal is cited, in

accordance with accepted academic practice.

No use, distribution or reproduction is

permitted which does not comply with

these terms.

Product presentation in the

live-streaming context: The effect

of consumer perceived product

value and time pressure on

consumer’s purchase intention

Nan Zhang

*

School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China

Live streaming is conducive to consumers obtaining rich and accurate product

information, by displaying products through real-time video technology. Live

streaming provides a new type of product presentation method, such as showing

products from different perspectives, interacting with consumers by trying the

products out, and answering consumers’ questions in real time. Other than the

current research focus on anchors (or influencers) and consumers in live-streaming

marketing, this article tried to explore the way of the product presentation and

its effect and mechanism on consumers’ purchase intention. Three studies were

conducted. Study 1 (N = 198, 38.4% male) used a survey to explore the main

effect of product presentation on consumers’ purchase intention and the mediating

effect of the perceived product value. Study 2 (N = 60, 48.3% male) was a

survey-based behavioral experiment, and it tested the above effects in the scenario

of food consumption. Study 3 (N = 118, 44.1% men) tried to deeply discuss

the above relationship in the appeal consumption scenario by priming different

levels of the product presentation and time pressure. The results found that

the product presentation positively affected consumers’ purchase intention. The

perceived product value played a mediating role in the relationship between product

presentation and purchase intention. In addition, different levels of time pressure in

the living room moderated the above mediation effect. When time pressure is high,

the positive impact of product presentation on purchase intention is strengthened.

This article enriched the theoretical research on product presentation by exploring

product presentation in the context of live-streaming marketing. It explained how

product presentation could improve consumers’ perceived product value and the

boundary effect of time pressure on consumers’ purchase intention. In practice,

this research guided brands and anchors on designing product displays to improve

consumers’ purchase decisions.

KEYWORDS

product presentation, live streaming, perceived product value, time pressure, purchase

intention

Frontiers in Psychology 01 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 2

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

Introduction

When consumers shop online, they cannot directly view,

touch, taste, or try products. Therefore, the product presentation

information becomes the critical clue for consumers to judge

the product quality and make purchase decisions (Jiang and

Benbasat, 2004). The e-commerce platforms try to optimize product

presentation to effectively convey related product information to

consumers, such as using traditional text, pictures, animation, voice,

background music, and video (Jovic et al., 2012). Distinct formats

of product presentation provide different influences on consumers’

cognition, emotion, and behavior. It has been proved that the high

media richness presentation could significantly reduce the perceived

risk and improve consumer trust (Yue et al., 2017) and consumer

product preference (Jovic et al., 2012).

With the rapid development of live-streaming marketing, the

living room provides a new style of product presentation in real-

time 3D formats. Extent research on product presentation mainly

focused on designs on the webpage of e-commerce, namely, the

2D display and prerecorded video (Algharabat et al., 2017; Petit

et al., 2019). However, few researchers have examined the effect and

specific mechanism of the live-streaming product display formats

on consumers’ decisions. Product presentation in live streaming

is different from that on a traditional e-commerce webpage.

The product presentation in live streaming provides rich visual

information by displaying products from multiple angles and sensory

information by trying the product. The interactive technology used

in live streaming helps to increase consumer engagement, time

sensitivity, and personalized shopping experience (Sjöblom and

Hamari, 2017). In addition, real-time interactions, such as displaying

products according to consumers’ requests and answering questions

in a targeted manner, make consumers feel like shopping in physical

stores (Kumar and Tan, 2015). Given the difference in product

presentation between webpage and live streaming, it is necessary to

explore how products should be presented in live streaming and the

effect on consumer behavior.

There is also a research gap on the research objects of live

streaming. Theoretically, live-streaming marketing mainly focused

on the characteristics of anchors and the interaction between anchors

and consumers on consumer decisions. The influencing factors

include anchor type (Huang et al., 2021), fit between anchor and

products/brand (Park and Lin, 2020), interactional communication

style (the sense of community and emotional support; Chen and Liao,

2022; Liao et al., 2022), consumer’s social motivation (Hilvert-Bruce

et al., 2018), and consumer’s state boredom (Zhang and Li, 2022).

However, less research paid attention to the effect of products.

In addition, the mechanism of product presentation in live

streaming on consumer’s decisions may change. Prior studies

explained the specific mechanisms of product presentation on

consumer’s purchase intention, such as mental imagery (Overmars

and Poels, 2015; Flaviaìn et al., 2017), perceived diagnosticity (Cheng

et al., 2022), and perceived risk (Fiore et al., 2005; Kim and Forsythe,

2008; Cano et al., 2017). Moreover, researchers also explored the

moderating effect of both consumer factors and product factors, such

as information processing motivation (Orús et al., 2017), need for

touch (Flaviaìn et al., 2017), the product type (Li and Meshkova,

2013; Huang et al., 2017), and product rating (Cheng et al., 2022).

However, the above findings might not explain the psychological

mechanism of consumers’ decisions in the context of real-time 3D

product presentation in the live room. Therefore, this article will test

the mediating effect of consumer perceived product value and the

moderating effect of time pressure.

Specifically, this research focused on product presentation in the

context of live streaming, and it intended to address the following

research questions. Could product presentation, rather than the

prevalent influence of anchors, promote consumer decisions in the

live room? How does the product presentation increase consumers’

purchase intention? Does time pressure strengthen or weaken the

positive effect of product presentation on consumers’ purchase

intention? Based on the theoretical analysis and practical observation,

this research proposed that a high level of product presentation

increases consumer purchase intention, through the mediating effect

of consumer perceived product value. The boundary effect of the

above relationship is the perceived time pressure in the live room.

Theoretical background and research

hypotheses

Online product presentation

Different from shopping offline, shopping online could not

provide an equivalent tactile experience in physical stores (Cano et al.,

2017). According to information processing at the cognitive level,

consumers need to acquire, process, retain, and retrieve information

(Eroglu et al., 2001). Therefore, e-commerce merchants need to

present consumers with timely, sensory, and rich-visual information

on product details (Petit et al., 2019), to reduce the uncertainty and

perceived risk when making purchase decisions online.

Thanks to the rapidly developed interactive technology (e.g.,

virtual reality, augmented reality, and real-time live streaming),

there are many product presentation formats for online

consumption. Traditional e-commerce websites can use various

visual presentations, such as static pictures, image zooming videos,

product rotation, 3D product presentation, and virtual fitting rooms

(Kim and Forsythe, 2008; Park et al., 2008; Algharabat et al., 2017;

Petit et al., 2019). Owing to the spatial limitations of the Internet, the

richness of media could increase the information transformation and

communication effect (Daft and Lengel, 1986). Compared to verbal

information in texts, pictures are seen as well-established predictors

of consumers’ mental imagery (Wu et al., 2016). Yoo and Kim (2014)

suggested that pictures are more effective than descriptions by texts,

and pictures showing the method and scene of usage are more

effective than pictures not showing them. Nowadays, online product

presentation videos have increasingly become the popular way to

display products online, because it has been proven to be more

prosperous and vivid than pictures and texts with dynamic visual

and auditory information (Jiang and Benbasat, 2007b; Vonkeman

et al., 2017), it increases the perceived ease of imaging the product

(Flaviaìn et al., 2017), and it provides the closest experience to the

product in physical stores (Kumar and Tan, 2015).

In general, extensive research on online product presentation

mainly focused on different kinds of product presentation formats.

On the one hand, some studies especially compared product

presentation text descriptions (Aljukhadar and Senecal, 2017),

pictures (Wu et al., 2020; Jai et al., 2021), interactive images

(Overmars and Poels, 2015), and virtual experience (Cowan et al.,

2021) with videos. Some scholars think that product presentation

Frontiers in Psychology 02 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 3

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

video is better than other formats (Roggeveen et al., 2015); however,

some scholars argued that product presented by pictures is more

effective for search products (Huang et al., 2017). On the other hand,

some research studies the combination of different kinds of product

presentation. Jovic et al. (2012) discovered that the most effective

combination format is text, picture, video, voice, and background

music. Yue et al. (2017) recommended the combination of static

photos, video, and 3D images.

Research has found that online product presentation formats

significantly influence consumers’ positive attitudes and purchase

intentions (Park et al., 2005; Jiang and Benbasat, 2007a; Verhagen

et al., 2014; Visinescu et al., 2015). The online product presentation

provides consumers with more product cues. It makes the products

more vivid (Orús et al., 2017) and more accessible to evaluate

(Jai et al., 2021). It also helps to increase consumer imagery

fluency (Orús et al., 2017) and perception of interactivity (Kim and

Forsythe, 2008) and decrease the perceived risk (Kim and Forsythe,

2008). In addition, it provides consumers with a sense of local

presence (Algharabat et al., 2017) and psychological ownership and

endowment (Brasel and Gips, 2014).

Product presentation in live streaming and

consumer’s purchase intention

As a new form of e-commerce, product demonstrations in live

streaming have not received enough attention. Unlike traditional

product video, live streaming provides a unique style of product

presentation. The product presentation in live streaming is close to

the actual using situations, showing products from various angles

and providing trials by real people. The basic product information

is introduced by anchors in words, rather than the traditional text

product introduction on a webpage. This increases the amount of

information transformation and the effectiveness of information

understanding, which makes it easier for consumers to perceive the

utilities of the product. In addition, anchors always try on products

during the live streaming, such as eating food and trying clothes on

and answer consumers’ questions interactively (Hilvert-Bruce et al.,

2018).

Compared with the original display format, the most significant

improvement of product presentation in live streaming is the rich,

vivid, and interactive visual experience. On the one hand, product

presentation in live streaming provides rich and tangible information.

This experience is the primary sensory experience of shopping

in the live room, and it increases the consumer’s perception of

product quality and tangibility. For example, the static pictures, 360

spin rotation, and virtual mirror help consumers to form a clear

mental representation of the product (Verhagen et al., 2016), get a

sense of its physical characteristics, and even get an idea of how

to use it (Schlosser, 2003; Jiang and Benbasat, 2007b). That is to

say, the product presentation could help consumers to get cues

about product functionality and its features (Coyle and Thorson,

2002). Therefore, the rich and tangible information presented in live

streaming positively affects consumers’ perceived practical value of

the product.

On the other hand, product presentation in live streaming

provides vivid and interactive information. One fundamental

problem with online shopping is that consumers lack sufficient

awareness of products because they cannot check or try them.

Jiang and Benbasat (2007b) found that diverse online product

presentations provide more product cues, increase the perception

of online products, and decrease information asymmetry. Studies

discovered that high-quality pictures, three-dimensional (3D) images

(Visinescu et al., 2015), and local presence (Verhagen et al., 2014)

make online product presentations more vivid and interactive. In

addition, a dynamic online product presentation, such as a product

presentation video, could provide more specific clues to activate

consumer mental imagery than a static online product presentation,

such as pictures and texts (Overmars and Poels, 2015). In more

depth, Huang et al. (2017) investigated how the interaction of

static and dynamic displays of products and product types would

affect consumer behavior. For experiential products (e.g., food or

beauty), consumers would give higher evaluations if the product

is displayed dynamically. Park et al. (2005) claimed that online

apparel shopping is popular but also risky, because of the lack of

sensory attributes displayed on the website, such as fabric hand,

garment fit, color, and quality. Therefore, e-tailers need to create

an attractive visual product presentation with some sense of fit

and other tactile experiences (Szymanski and Hise, 2000). Three-

dimensional (3D) product presentation enables consumers to visually

inspect products by enlarging, zooming in or out on the product,

and rotating the product (Algharabat et al., 2017). The interaction

between anchors and consumers, especially the try-on behavior,

makes the product presentation in live streaming more vivid and

interactive and improves consumers’ purchase intention.

Generally speaking, product presentation in live streaming can

help consumers better diagnose product quality, which enhances

consumers’ shopping pleasure (Jiang and Benbasat, 2007a). Various

formats of product presentations provide consumers virtual product

experience (VPE) and enhance consumers to feel, touch, and even try

products in a virtual online environment (Li et al., 2003). Based on

these, this article proposed the first hypothesis:

H1: Product presentation in live streaming has a positive effect

on consumer’s purchase intention.

Mediating effect of consumer’s perceived

product value

A consumer’s perceived product value is an overall mental

evaluation of a particular good (Peterson and Yang, 2004). Product

perceived value is about the assessment of consumers that they have

received in terms of product quality and satisfaction and also that

they have given in terms of money, time, and other costs. Research

reveals that the perception of product value is a multidimensional and

highly subjective evaluation of factors (Ruiz et al., 2008), including

functional, symbolic, and experiential attributes (Boksberger and

Melsen, 2011).

This article used the classic division of perceived product value

dimensions: utilitarian and hedonic. On the one hand, utilitarian

value is product-centric thinking, focusing on the functional,

instrumental, and extrinsic cues of products (Hirschman and

Holbrook, 1982). The two typical utilitarian values for consumers are

monetary saving and convenience (Rintamäki et al., 2006). Monetary

saving happens when consumers find discounted products, or when

the prices are perceived as less than other stores. It reduces the

consumer’s pain of paying (Chandon et al., 2000) and increases the

Frontiers in Psychology 03 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 4

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

consumer’s perceived utilitarian value of the product. Convenience

is defined as a ratio of inputs (e.g., time and effort) to outputs

(Holbrook, 1999). Seiders et al. (2000) pointed out that maximizing

the speed and ease of shopping contributes to convenience. They

defined four kinds of convenience, including access (reach a retailer),

search (identify and select the essential products), possession (obtain

desired products), and transaction (effect or amend transactions)

convenience (Seiders et al., 2000).

On the other hand, the hedonic perception value of the product

is self-oriented and self-purposeful (Holbrook, 1999). Generally

speaking, consumers want entertainment and exploration during

the consumption experience (Rintamäki et al., 2006). Studies found

that themed environments, shows or events, and the overall store

atmospherics could improve the entertainment of the shopping

experience (Babin and Attaway, 2000). Hedonic value is sometimes

a reaction to aesthetic features and is related to positive emotions

evoked by the shopping experience. In addition, exploration is

about the excitement of product or information search (Chandon

et al., 2000). Consumers see shopping as an adventure, just enjoying

browsing, seeking, and bargaining (Hausman, 2000).

Product presentation in the live-streaming context improves

consumers’ perception of utilitarian product value from the

convenient and monetary-saving parts. First, products in the living

room are introduced and trailed by the anchors, and the linguistic and

behavioral information output decreases time consumption. Once

consumers enter the living room, they can easily access the products

they are interested in, in the product lists or from the anchor’s display.

They can also ask questions about the products to the anchors or

the customer service staff. In addition, the design of the transaction

process is easy and quick. These increase the perception of product

utilitarian value, namely, access, search, possession, and transaction

convenience. Second, product price seems cheaper than other sales

channels. The anchors spend a lot of time discussing price discounts,

such as receiving coupons, buy one get one, and other gifts. Therefore,

consumers will count the price rationally and feel monetary savings.

At the same time, product presentation in the live-streaming

context can also enhance consumer perceived hedonic product value

from the entertainment and exploration aspects. First, the anchors in

the live streaming are generally attractive, introduce products funnily,

and make the consumers relaxed and delighted. Also, consumers

could raise questions to anchor and interact with other audiences,

which enhances their sense of immersion and offers a relatively real

shopping scene (Liu et al., 2020). Finally, live-streaming selling is a

new marketing strategy focused on consumers’ unnoticed interests,

which leads consumers to explore new products. In reality, many

consumers have no purchase needs at the beginning. Still, after

watching the introduction in the living room, they become interested

in the product and intend to buy it.

A consumer’s perceived product value is one of the most

critical determinants of a consumer’s purchase intention (Chang and

Wang, 2011). When consumers shop online, the utilitarian value of

the website could positively affect their flow experience and then

affect their intention of continuing to consume (Chang and Chen,

2014). As for the hedonic shopping value, it will affect consumers’

information search propensity and purchase intention (Wang, 2010).

In addition, hedonic values have a direct impact on consumers’

perceived uniqueness, leading to place dependence, frequent visits,

and longer shopping time (Allard et al., 2009).

Therefore, product presentations in live streaming enhance

the two kinds of perceived product value, by providing external

information and generating self-cognitions for consumers.

After obtaining product-related information, consumers would

psychologically reflect on the meanings and value of the information

in the product. Thus, the higher the value of information, the higher

the consumer’s perceived product value (Zhang and Merunka, 2015).

At the same time, the higher the value of information indicates that

consumers have an in-depth and comprehensive understanding of

the product and thus feel the product is sincere and reliable (Manfred

et al., 2012). Hence, this article used perceived product value as

mediating variable and proposed the second hypothesis:

H2: Consumer’s perceived product value mediated the

positive effect of the product presentation and consumer’s

purchase intention.

Moderating effect of time pressure on

consumption

Time pressure is an anxious emotional response that arises

from the decision-maker’s lack of time to complete tasks within a

specific deadline (Svenson and Edland, 1987). Time pressure could be

divided into subjective time pressure and objective time pressure. The

subjective time pressure is mainly determined by the discount rates,

while the objective time pressure is determined by the promotion

time constraints. Discount rates and time constraints constitute

opportunity costs, lead to consumers’ perceived time pressure, and

then affect consumers’ decisions (Zhu and Zhang, 2021).

Time pressure has a moderating effect on the mediation

relationship between product presentation and consumer purchase

intention. Time pressure reduces consumers’ information search

during the purchase decision process (Beatty and Smith, 1987).

Under time pressure, consumers spend significantly less time

searching for information, especially unbiased information sources

(Murray, 1983). In addition, their cognitive closure is more inclined

to intuitive heuristics (Murray, 1983), relying on experience or

intuition to make decisions. Under this condition, consumers tend

to exaggerate the perceived benefits, ignore possible risks, look for

evidence to support their ideas, and pay less or no attention to

evidence that denies their views. They have less time to attain and

analyze other rich information rather than that got from product

presentation, and they make purchase decisions impulsively and

fast. That is to say, for consumers with high time pressure, their

purchase intention primarily relied on information obtained from

product presentations. Therefore, the limited time constraint, or time

pressure, may enhance the positive effect of product presentation on

consumers’ purchase intention. Based on these, the third hypothesis

was proposed:

H3: Time pressure moderates the effect of product presentation

on consumers’ purchase intention. For consumers under a

high level of time pressure, product presentation is positively

associated with consumer purchase intention; for consumers

under a low level of time pressure, the positive impact of product

presentation on purchase intention is attenuated.

Based on the above hypotheses, the research framework is shown

in Figure 1.

Frontiers in Psychology 04 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 5

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

FIGURE 1

The research framework.

Study 1

Study 1 was a self-reported survey, to explore the main

effect of product presentation on consumers’ purchase

intention and the mediating effect of the perceived product

value. In Study 1, participants were asked to recall their

consumption experience in live streaming and answer

related questionnaires.

Participants

The questionnaire was designed and released through the

Credamo platform. We received 249 answers. There were 198

qualified responses eventually, after excluding questionnaires that

showed too long/short duration, regular answering patterns,

incomplete information, and failed to pass screening questions.

Among them, 76 (38.4%) were male participants, 141 (71.2%) were

21–30 years old, and 51 (25.8%) were 31–40 years old. More

demographic information was shown in Table 1.

Procedures and measures

After obtaining informed consent, participants were asked to

recall their last live-streaming watching and shopping experience

and answer related questions. First, the detailed information

was based on the consumption experience. They were asked

whether they watched the consumption live streaming and

whether they bought products in the live-streaming room. They

were also required to write down this consumption experience

with detailed information, such as the brand, product category

(e.g., clothing, food, and cosmetics), and price, to enhance the

recalling effect. Second, product presentation was measured with

mature scales (α = 0.62; Farrelly et al., 2019). Third, product

purchase intention was measured with a 4-item scale adapted

from mature scales (α = 0.83; Huang et al., 2013). Fourth,

perceived product value was measured with 12 items in total

(α = 0.88; Mathwick et al., 2001; Loiacono et al., 2007) for the

utilitarian and hedonic value. All the items were measured with

a 7-Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly

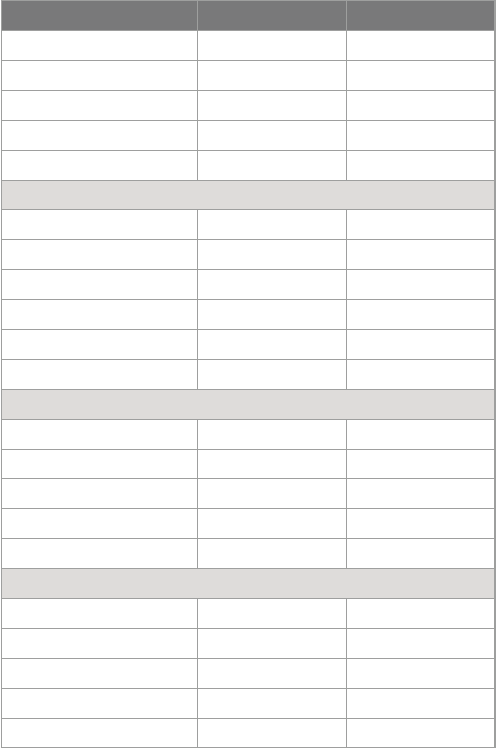

TABLE 1 Description of participants’ demographics in Study 1.

Age N Percentage (%)

0–20 3 1.5

21–30 141 71.2

31–40 51 25.8

41–50 3 1.5

Education

High school 2 1.0

Associate’s degree 17 8.6

Bachelor’s degree 163 82.3

Master’s degree 14 7.1

Ph.D. degree 2 1.0

Occupation

Student 17 8.6

State-owned enterprises 46 23.2

Public institutions 33 16.7

Civil servant 2 1.0

Private enterprises 89 44.9

Foreign-invested enterprises 11 5.6

Monthly income (RMB)

<3,000 13 6.6

3,000–4,999 32 16.2

5,000–7,999 81 40.9

8,000–10,000 46 23.2

≥10,000 26 13.1

Monthly consumption (RMB)

<1,000 19 9.6

1,000–1,999 85 42.9

2,000–2,999 65 32.8

3,000–4,000 25 12.6

≥4,000 4 2.0

N = 198.

agree. Finally, demographics were collected, including gender,

age, occupation, highest education, monthly income, and monthly

consumption.

Frontiers in Psychology 05 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 6

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

TABLE 2 Description and correlation of variables in Study 1.

Mean SD Product

perceived value

Purchase

intention

Product

presentation

5.85 0.58

Perceived product

value

5.80 0.54 0.76**

Purchase intention 5.81 0.57 0.72** 0.79**

**p < 0.01.

TABLE 3 Regression analysis for Study 1.

Purchase intention Model 1 Model 2

β t β t

Product presentation 0.72** 14.43 0.71** 13.75

Gender −0.11* −2.05

Age −0.12* −2.28

Occupation 0.07 1.33

Education 0.12* 2.37

Monthly income −0.003 −0.05

Monthly consumption 0.02 0.25

R

2

0.52 0.55

Adjusted R

2

0.512 0.533

F 208.09 33.12

N = 198; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Results

Common method bias check

Given the nature of the single-shot cross-sectional survey, we first

checked whether there was a common method bias before the formal

data analysis. Harman’s one-factor analysis was conducted (Podsakoff

and Organ, 1986), by including all of the items of critical variables for

an exploratory factor analysis using a maximum likelihood solution.

The results showed that four factors emerged with eigenvalues larger

than 1.00, indicating that more than one factor underlies the data.

In addition, the first factor accounted for only 39.12% of the total

variance, suggesting that the common method variance may not be

a severe concern in the present study (Eby and Dobbins, 1997).

The main effect of product presentation

on consumer’s purchase intention

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of key variables

are presented in Table 2. To test the main effect of product

presentation on product purchase intention in the live streaming,

regression analysis was conducted by two models (refer to Table 3).

In Model 1, we regressed the product presentation on consumers’

purchase intention. Model 2 revealed that after controlling for

demographic variables such as gender, age, education, occupation,

monthly income, and monthly expenditure, product presentation

also positively predicted customers’ purchase intention (β = 0.71,

t = 13.75, p < 0.000, refer to Table 3) and, thus, H1 was supported.

Mediation effect analysis

We predicted that the perceived product value would mediate

the effect of product presentation on product purchase intention.

A 5,000 resampling bootstrapping mediation analysis using product

presentation as the predictor, perceived product value as the

mediator, and product purchase intention as the dependent variable

(Hayes, 2018, Model 4) confirmed this prediction. The analysis

revealed a significant omnibus index of mediation (Effect = 0.43,

SE = 0.07, 95% CI: [0.30, 0.58]). Thus, H2 was supported.

Study 2

Study 2 was a survey-based behavioral experiment. The aim

of Study 2 was to test the main effect of product presentation on

consumer purchase intention, and the mediation effect of perceived

product value, namely to verify H1 and H2.

Participants

This experiment was designed and distributed through the online

survey platform Credamo.

1

A total of 83 subjects, who had not joined

Study 1, participated in the formal experiment, and 23 subjects were

excluded because of too long or too short response time, inconsistent

responses, and wrong answers for the attention check. Among the

final 60 participants, 29 (48.3%) were male participants, and the

average age was 29.08 years (SD = 5.54, Min = 18, Max = 42). More

demographics are shown in Table 4.

Procedures and measures

Study 2 was a one-factor (product presentation: high vs. low)

between-subject design. The final 60 subjects were randomly assigned

to one of two experimental groups, with 30 people in each condition.

Before the formal experiment, participants signed informed consent

online. They were guaranteed anonymity and allowed to discontinue

the experiment at any time. They were told that this was a sociological

study that consisted of several unrelated sub-surveys. After the

answer was qualified and accepted, each participant would be paid

5 yuan in renminbi (RMB).

Participants were first shown the same live-streaming clip for

approximately 20 s. It was cut from the “Ear Gourmet” living room

and presented the product of chocolate. This video introduced the

basic product information, including the chocolate brand, original

country, price, and four kinds of flavors.

Second, the different conditions were primed with different

descriptions of the product presentation information. The high level

of product presentation is primed by enough information about

this chocolate in detail, such as the origin, raw materials, functional

groups, product positioning, and applicable scenarios. In addition,

the participants were told that the anchor also introduced the

information about this chocolate in detail through various behaviors

in the live streaming, including the anchor’s tasting, the assistant’s

1 https://www.credamo.com/#/

Frontiers in Psychology 06 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 7

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

TABLE 4 Description of participants’ demographics in Study 2.

Education N Percentage (%)

High school 1 1.7

Associate’s degree 4 6.7

Bachelor’s degree 42 70.0

Master’s degree 13 21.7

Ph.D. degree 0 0

Occupation

Student 13 21.7

State-owned enterprises 12 20.0

Public institutions 4 6.7

Civil servant 3 5.0

Private enterprises 24 40.0

Foreign-invested enterprises 4 6.7

Monthly income (RMB)

<3,000 10 16.7

3,000–4,999 14 23.3

5,000–7,999 18 30.0

8,000–10,000 8 13.3

≥10,000 10 16.6

Monthly consumption (RMB)

<1,000 21 35.0

1,000–1,999 25 41.7

2,000–2,999 11 18.3

3,000–4,000 2 3.3

≥4,000 1 1.7

N = 60.

tasting, product detail display, and interactive Q&A. However, in the

group of low-level product presentation, participants were told that

the anchor did not introduce other product information, except for

the above information got in the video. Furthermore, the anchor did

not show the product through behaviors in the live streaming, such

as the anchor’s tasting, the assistant’s tasting, product detail display,

and interactive Q&A.

Third, participants were asked to recall video contents and then

answer their purchase intention with four items (α = 0.93; Huang

et al., 2013). Fourth, manipulation checks and attention checks were

tested. The questions for the manipulation check used the scales

of product presentation (α = 0.91; Farrelly et al., 2019) with seven

items, such as “Anchor introduced objective attributes of products,

such as ingredients and specifications” and “There are product trials

sessions in live streaming.” Furthermore, there are two questions for

the attention check, about the contents of the video or text reminder.

Fifth, product perceived value was measured with six items for the

utilitarian value (α = 0.91; Loiacono et al., 2007) and six items for

the hedonic value (α = 0.93; Mathwick et al., 2001). The example

items are “The products recommended in live streaming meet my

functional demands for such products” and “I think the live streaming

entertains me.” Finally, the demographics were collected, including

gender, age, highest education, work, monthly income, and monthly

consumption.

Results

Manipulation check of product

presentation

The results indicated that there is a significant difference in

the perception of product presentation between the high-level

(Mean = 5.73, SD = 0.90) and the low-level groups (Mean = 2.80,

SD = 0.59), t = −15.01, p < 0.000. Therefore, the manipulation of

high and low levels of product presentation succeeded.

The main effect of product presentation

on consumer’s purchase intention

The independent sample t-test revealed that product

presentation had a positive main effect on consumers’ purchase

intention. Participants in the high product presentation had

higher purchase intention (M

high product

presentation

= 5.70, SD

high

product

presentation

= 0.99) than those in the low group (M

low product

presentation

= 3.92, SD

low product

presentation

= 1.40), t = −5.71, p < 0.000.

Thus, H1 was supported.

Mediation effect analysis

We predicted that consumers’ perceived product value would

mediate the effect of product presentation on product purchase

intention. A 5,000 resampling bootstrapping mediation analysis

confirmed this prediction, using product presentation as the

predictor, perceived product value as the mediator, product purchase

intention as the dependent variable (Hayes, 2018, Model 4),

and demographics as control variables. The analysis revealed a

significant omnibus index of mediation for product presentation

(Effect = 0.99, SE = 0.26, 95% CI: [0.54, 1.56]). Thus, H2 was

supported.

Study 3

Study 3 was a survey-based behavioral experiment to explore

further the mediating effect of product value perception and

moderated mediation effect of time pressure in the clothing

consumption scenario.

Participants

A total of 176 participants were recruited from the sample

database on Credamo. After excluding 58 answers that were too

long or too short response time, inconsistent responses, and

wrong answers for the attention check, 118 valid answers were

reserved. Among them, 52 (44.1%) were male participants, and

the average age was 28.53 years (SD

age

= 6.72, Min

age

= 19,

Max

age

= 52). More demographic information is shown in

Table 5.

Frontiers in Psychology 07 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 8

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

TABLE 5 Description of participants’ demographics in Study 3.

Education N Percentage (%)

High school 2 1.6

Associate’s degree 15 12.7

Bachelor’s degree 87 73.7

Master’s degree 14 11.9

Ph.D. degree 0 0

Occupation

Student 32 27.1

State-owned enterprises 24 20.3

Public institutions 5 4.2

Civil servant 2 1.7

Private enterprises 50 42.4

Foreign-invested enterprises 5 4.2

Monthly income (RMB)

<3,000 30 25.4

3,000–4,999 20 16.9

5,000–7,999 29 24.6

8,000–10,000 17 14.4

≥10,000 22 18.6

Monthly consumption (RMB)

<1,000 52 44.1

1,000–1,999 44 37.3

2,000–2,999 14 11.9

3,000–4,000 7 5.9

≥4,000 1 0.8

N = 118.

Procedures and measures

Study 3 followed a 2 (product presentation: high vs. low)

∗

2 (time

pressure: high vs. low) between-subject design. Participants were

recruited to join in a survey on product evaluation in live streaming.

They signed informed consent online, guaranteed anonymity, and

were allowed to discontinue the experiment at any time. After

the answer was checked and accepted, each participant would be

paid 5 yuan in RMB.

First, watch the same video of the product. All participants were

asked to watch a short video carefully, which was an excerpted video

from Anta’s live-streaming room. The anchor introduced the black

and white panda sneakers, the same style for men and women.

The price of this product in the live-streaming room is 229 yuan

in RMB. Second is the manipulation of different levels of product

presentation. Participants were randomly assigned to read different

descriptions of the information in the live room, to prime consumers’

different perceptions of the product presentation and time pressure.

The product presentation was primed with detailed/brief descriptions

of the shoes, to manipulate the high/low level of product presentation.

The high/low time pressure was primed by “The low price and

coupons in the live-streaming room are valid for a short/long

time, leaving a short/long time for consumers to make purchasing

decisions.” “The anchor continues to/does not continue to urge

consumers to quickly buy” (Benson and Svenson, 1993). Third,

participants completed the purchase intention scale (α = 0.93) and

product value perception scale (α = 0.96; Mathwick et al., 2001;

Loiacono et al., 2007). Then, participants indicated their agreement

on two scales as a manipulation check for product presentation

(α = 0.89; Farrelly et al., 2019) and time pressure (α = 0.95; Svenson,

1992). All measurements were based on a 7-point Likert scale

(1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree). Finally, participants

reported their demographics as identical to that in Study 2. We also

included an attention check in the middle of the process.

Results

Manipulation check of the product

presentation and time pressure

As we expected, participants in the high product presentation

perceived high product presentation information (M

high product

presentation

= 5.68, SD

high product

presentation

= 0.87) more than those

in the low group (M

low product

presentation

= 3.69, SD

low product

presentation

= 1.08), t = −10.99, p < 0.000. Moreover, the t-test revealed

that there is also a significant difference in the perception of time

pressure between high and low groups, t = −15.81, p < 0.000, M

high

time pressure

= 5.73, SD

high

time pressure

= 1.08, M

low

time pressure

= 2.28,

SD

low

time pressure

= 1.27. The result showed that the manipulation of

the product presentation and time pressure was effective.

The main effect of product presentation

on consumer’s purchase intention

The independent sample t-test revealed that product

presentation had a positive main effect on consumers’ purchase

intention. Participants in the high product presentation had

higher purchase intention (M

high product

presentation

= 5.80, SD

high product

presentation

= 0.72) than those in the low group (M

low

product

presentation

= 4.06, SD

low product

presentation

= 1.55), t = −5.71,

p < 0.000. Thus, H1 was supported.

Mediation effect of perceived product

value

Based on Model 4 in PROCESS (Hayes, 2018), we conducted a

5,000 resampling bootstrapping mediation analysis, using product

presentation (0 = low level, 1 = high level) as the predictor,

consumer perceived product value as the mediator, and consumer’s

purchase intention as the dependent variable. The results confirmed a

significant mediation effect of product value (Effect = 1.15, SE = 0.18,

95% CI: [0.80, 1.50]). Therefore, H2 was supported again.

Moderation effect

Following Model 5 of the PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2012), we

performed a 5,000 resampling bootstrapping moderated mediation

analysis with product presentation (0 = low level, 1 = high

Frontiers in Psychology 08 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 9

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

level) as the independent variable, perceived product value as the

mediator, time pressure (0 = low level, 1 = high level) as the

moderator, and consumer’s purchase intention as the dependent

variable. The results indicated a moderated effect of time pressure

perception (Effect = 0.70, SE = 0.26, 95% CI: [0.20, 1.21]). In

particular, for consumers with a low level of time pressure, the

main effect of product presentation on purchase intention was

not significant (Effect = 0.27, SE = 0.19, 95% CI: [−0.10, 0.64]);

However, when the time pressure perception was high, the positive

effect of product presentation on consumer’s purchase intention

was significant (Effect = 0.97, SE = 0.20, 95% CI: [0.57, 1.38]). In

addition, the mediation effect of “product presentation→product

value perception→purchase intention” was significantly positive

(Effect = 1.11, SE = 0.18, 95% CI: [0.78, 1.46]). Therefore, H3 was

supported.

Conclusion and implications

Conclusion

This article focused on the formats of product presentation in

the context of live streaming. It investigated the relationship between

product presentation and consumer purchase intention and the

specific psychological mechanisms. Based on three studies, this article

found that product presentation in live streaming had a positive effect

on consumers’ purchase intention. Also, it tested the mediating effect

of consumer perceived product value, both utilitarian and hedonic

values, and the moderated mediation effect of time pressure. The

results indicated that product presentation, especially the high level

of vivid, rich, and interactive information displayed in the live room,

increased consumers’ perception of product value, thereby improving

consumers’ purchase decisions. However, the boundary of the above

effect is the time pressure perception. When consumers considered

that the time pressure is high, they had less time to access, process,

and analyze related product information, and the positive effect of

product presentation on purchase intention was enhanced.

Theoretical contributions

Theoretically speaking, this article extended the literature on

product presentation, by providing a new research context of live

streaming. Previous research mainly focused on product display

in e-commerce on the webpage, involving text, pictures, videos,

and other dynamic display methods (Overmars and Poels, 2015;

Wu et al., 2020; Cowan et al., 2021; Jai et al., 2021). To some

extent, this is a kind of two-dimensional (2D) and sometimes

three-dimensional (3D) product presentation, which is a one-way

information input from the webpage to consumers. However, the

product presentation in the live-streaming scene is a real-time, two-

way, and 3D combination display (Sjöblom and Hamari, 2017).

Products are presented by oral introductions, tryouts in action, and

answers to consumers’ personalized questions by the anchor. The

Q&As between anchors and consumers realize two-way information

transmission, which helps consumers learn more rich, interactive,

and tangible product information. In addition to the differences in

the specific forms of product displays, the particular mechanism

of the product presentation on consumers’ decisions also needs to

be re-examined. Prior studies have found that the product display

on the webpage works through perceived risk (Jiang and Benbasat,

2007b), mental imagery (Overmars and Poels, 2015), vividness (Orús

et al., 2017), interactivity (Kim and Forsythe, 2008), local presence

(Algharabat et al., 2017), and so on. However, this article found that

rich product presentation helps consumers understand the utilitarian

and hedonic value of the product in an all-around way, thereby

promoting their purchase intention.

In addition, this article extended the literature on live streaming

and consumer behaviors, by providing a new research perspective on

product presentation. Live streaming is a rapidly emerging Internet-

age phenomenon. Scholars currently studied the characteristics of

the anchor and the consumers, the characteristics of the anchor

(anchor type; Huang et al., 2021), the fit between the anchor and

products (Park and Lin, 2020), typology of seller’s sales approach

(Wongkitrungrueng et al., 2020), consumer’s social motivation

to watch live streaming (Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2018), personal

characteristics for live-streaming addiction (state boredom; Zhang

and Li, 2022), and so on. However, less research cares about product

presentation currently. It seems that the particularity of the live

streaming is the anchor. But in fact, this real-time video greatly

enriches the form and content of product display. Therefore, this

article studied the effect of product presentation on consumers’

purchase decisions. At the same time, this article also considered time

pressure, a new factor in the living room, as a moderator. Limiting

time is often used in the live room, but whether the substantial

effect is good or bad is not conclusive. Therefore, simultaneous

consideration of product presentation and time pressure makes a

theoretical contribution to the study of live marketing.

Managerial implications

From the marketing practices, the results of this article would

support brands, anchors, and consumers. On the one hand, the

formats of product presentation in the living room should be

well designed. This article concluded that a high level of product

presentation has a positive effect on consumer purchase intention.

Therefore, brands and anchors could get enlightenment on how to

fully use different presentation methods to maximize consumers’

perceived value and purchase intention. Within the live-streaming

shopping, anchors are supposed to focus on introducing the

characteristics of products, optimizing the performance of trials and

Q&As, and using product value and stories as supplements. By

reasonably assigning the significance of a high level of presentation

information, consumers could perceive utilitarian and hedonic

product value faster and better. This display enhances consumers’

shopping pleasure (Jiang and Benbasat, 2007a) and provides a

similar experience to shopping in physical stores (Kumar and Tan,

2015). Hence, consumers could be delighted, would like to purchase

products, and stay in the live room for a long time (Jovic et al., 2012).

On the other hand, anchors should enhance the role of time

pressure in a timely manner to achieve the effect of stimulating

consumer purchase. In practice, the time constraints for each product

in the live room are very strict. It seems that the less time left to

the consumer, the more likely the consumer is to buy impulsively.

However, how to control the purchase time embodies the art of

management. Excessive time constraints can degrade the shopping

experience for consumers. Therefore, if brands or anchors hope to

stimulate consumers’ impulse buying by limiting the purchase time,

Frontiers in Psychology 09 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 10

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

they should highlight the product valve (e.g., benefits and scarcity of

the product) as much as possible and improve the transaction utility

of the products (Zhu and Zhang, 2021).

Limitations and future research

There are two deficiencies in this article, and future research

can make up for two aspects. First is the division of product

presentations. In this article, product presentation is considered as

a whole, and the differential effects of its high and low levels on

consumer decisions were studied. In the future, researchers could

divide product presentation as intrinsic cues (e.g., flavor and aroma

cues for beer) and extrinsic cues (e.g., price, store image; Olson

and Jacoby, 1972). Second is the abundance of stimuli materials.

In this article, the stimuli chosen from the live streaming are food

and appeal, which are the top two popular categories sold for live

streaming. In the future, more kinds of products (such as terroir

products or tourism products) could be studied in order to see

whether the results are still robust.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be

made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and

approved by the School of Economics and Management, Beijing

Jiaotong University. The patients/participants provided their written

informed consent online to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NZ: conceptualization, methodology, writing and editing,

funding acquisition, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author acknowledge the financial supported from the

“National Natural Science Foundation of China” (Grant Nos.

72102012 and 71832015).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the

absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be

construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the

authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated

organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers.

Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may

be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the

publisher.

References

Algharabat, R., Alalwan, A. A., Rana, N. P., and Dwivedi, Y. K. (2017). Three

dimensional product presentation quality antecedents and their consequences for online

retailers: The moderating role of virtual product experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 36,

203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.02.007

Aljukhadar, M., and Senecal, S. (2017). Communicating online information via

streaming video: The role of user goal. Online Inform. Rev. 41, 378–397. doi: 10.1108/

OIR-06-2016-0152

Allard, T., Babin, B. J., and Chebat, J. C. (2009). When income matters: Customers

evaluation of shopping malls’ hedonic and utilitarian orientations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv.

16, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2008.08.004

Babin, B. J., and Attaway, J. S. (2000). Atmospheric effect as a tool for creating customer

value and gaining share of customer. J. Bus. Res. 49, 91–99. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(99)

00011-9

Beatty, S. E., and Smith, S. M. (1987). External search effort: An investigation

across several product categories. J. Consum. Res. 14, 83–95. doi: 10.1086/20

9095

Benson, L., and Svenson, O. (1993). Post-decision consolidation following the

debriefing of subjects about experimental manipulations affecting their prior decisions.

Psychol. Res. Bull. 32, 1–13.

Boksberger, P. E., and Melsen, L. (2011). Perceived value: A critical examination of

definitions, concepts and measures for the service industry. J. Serv. Mark. 25, 229–240.

doi: 10.1108/08876041111129209

Brasel, S. A., and Gips, J. (2014). Tablets, touchscreens, and touchpads: How varying

touch interfaces trigger psychological ownership and endowment. J. Consum. Psychol.

24, 226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2013.10.003

Cano, M. B., Perry, P., Ashman, R., and Waite, K. (2017). The influence of image

interactivity upon user engagement when using mobile touch screens. Comput. Hum.

Behav. 77, 406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.042

Chandon, P., Wansink, B., and Laurent, G. (2000). A benefit congruency framework of

sales promotion effectiveness. J. Mark. 64, 65–81. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.64.4.65.18071

Chang, C. C., and Chen, C. W. (2014). Examining hedonic and utilitarian bidding

motivations in online auctions: Impacts of time pressure and competition. Int. J. Electr.

Commerce 19, 39–65.

Chang, H. H., and Wang, H. W. (2011). The moderating effect of customer perceived

value on online shopping behaviour. Online Inform. Rev. 35, 333–359. doi: 10.1108/

14684521111151414

Chen, J., and Liao, J. (2022). Antecedents of viewers’ live streaming watching: A

perspective of social presence theory. Front. Psychol. 13:839629. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.

839629

Cheng, Z., Shao, B., and Zhang, Y. (2022). Effect of product presentation videos on

consumer’s purchase intention: The role of perceived diagnosticity, mental imagery, and

product rating. Front. Psychol. 13:812579. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.812579

Cowan, K., Spielmann, N., Horn, E., and Griffart, C. (2021). Perception is reality. . .

How digital retail environments influence brand perceptions through presence. J. Bus.

Res. 123, 86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.058

Coyle, J., and Thorson, E. (2002). The effects of progressive levels of interactivity and

vividness in web marketing sites. J. Adv. 15, 65–77. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2001.10673646

Daft, R. L., and Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media

richness and structural design. Manag. Sci. 32, 554–571. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554

Frontiers in Psychology 10 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 11

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

Eby, L. T., and Dobbins, G. H. (1997). Collectivistic orientation in teams: An

individual and group-level analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 18, 275–295. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)

1099-1379(199705)18:3<275::AID-JOB796>3.0.CO;2-C

Eroglu, S., Machleit, K., and Davis, L. (2001). Atmospheric qualities of online retailing

A conceptual model and implications. J. Bus. Res. 54, 177–184. doi: 10.1016/S0148-

2963(99)00087-9

Farrelly, F., Kock, F., and Josiassen, A. (2019). Cultural heritage authenticity:

A producer view. Ann. Tour. Res. 79:102770. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.10

2770

Fiore, A. M., Kim, J., and Lee, H.-H. (2005). Effect of image interactivity technology

on consumer responses toward the online retailer. J. Interact. Mark. 19, 38–53. doi:

10.1002/dir.20042

Flaviaìn, C., Gurrea, R., and Oruìs, C. (2017). The influence of online product

presentation videos on persuasion and purchase channel preference: The role of imagery

fluency and need for touch. Telemat. Inform 34, 1544–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.

002

Hausman, A. (2000). A multi-method investigation of consumer motivations

in impulse buying behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 17, 403–419. doi: 10.1108/

07363760010341045

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process

analysis: a regression-based approach (methodology in the social sciences), 2nd Edn. New

York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable

mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Available online at: https://

www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed May 13, 2021).

Hilvert-Bruce, Z., Neill, J. T., Sjöblom, M., and Hamari, J. (2018). Social motivations

of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput. Hum. Behav. 84, 58–67. doi:

10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.013

Hirschman, E. C., and Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption:

Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 46, 92–101. doi:

10.1177/002224298204600314

Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Introduction to consumer value, Consumer Value: A

Framework for Analysis and Research. London: Routledge Kegan Paul. doi: 10.4324/

9780203010679.ch0

Huang, J., Zou, Y. P., Liu, H. L., and Wang, J. T. (2017). Is ‘Dynamic’ Better Than

‘Static’? The effect of product presentation on consumer’s evaluation – the mediation

effect of cognitive processing. Chin. J. Manag. 14, 742–750.

Huang, L., Tan, C. H., Ke, W., and Wei, K. K. (2013). Comprehension and assessment

of product reviews: A review-product congruity proposition. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 30,

311–343. doi: 10.2753/MIS0742-1222300311

Huang, M., Ye, Y., and Wang, W. (2021). The interaction effect of broadcaster and

product type on consumer’s purchase intention and behaviors in livestreaming shopping.

Nankai Bus. Rev. 9, 1–21.

Jai, T.-M., Fang, D., Bao, F. S., James, R. N., Chen, T., and Cai, W. (2021). Seeing it is like

touching it: Unraveling the effective product presentations on online apparel purchase

decisions and brain activity (an fMRI study). J. Interact. Mark. 53, 66–79.

Jiang, Z., and Benbasat, I. (2004). Virtual product experience: Effects of visual and

functional control of products on perceived diagnosticity and flow in electronic shopping.

J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 21, 111–147. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2004.11045817

Jiang, Z., and Benbasat, I. (2007a). Investigating the influence of the functional

mechanisms of online product presentations. Inform. Syst. Res. 18, 454–470. doi: 10.1287/

isre.1070.0124

Jiang, Z., and Benbasat, I. (2007b). The effects of presentation formats and task

complexity on online consumer’s product understanding. MIS Q. 31, 475–500. doi: 10.

2307/25148804

Jovic, M., Milutinovic, D., Kos, A., and Tomazic, S. (2012). Product presentation

strategy for online customers. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 18, 1323–1342.

Kim, J., and Forsythe, S. (2008). Adoption of virtual try-on technology for online

apparel shopping. J. Interact. Mark. 22, 45–59. doi: 10.1002/dir.20113

Kumar, A., and Tan, Y. L. (2015). The demand effects of joint product advertising in

online videos. Manag. Sci. 61, 1921–1937. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2014.2086

Li, H., Daugherty, T., and Biocca, F. (2003). The role of virtual experience in consumer

learning. J. Consum. Psychol. 13, 395–407. doi: 10.1207/S15327663JCP1304_07

Li, T., and Meshkova, Z. (2013). Examining the impact of rich media on consumer

willingness to pay in online stores. Electr. Commerce Res. Appl. 12, 449–461. doi: 10.1016/

j.elerap.2013.07.001

Liao, J., Chen, K., Qi, J., Li, J., and Yu, I. Y. (2022). Creating immersive and parasocial

live shopping experience for viewers: The role of streamers’ interactional communication

style. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 17, 140–155. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-04-2021-0114

Liu, F. J., Meng, L., Chen, S. Y., and Duan, K. (2020). The impact of network

celebrities’ information source characteristics on purchase intention. Chin. J. Manag. 17,

94–104.

Loiacono, E. T., Watson, R. T., and Goodhue, D. L. (2007). WebQual: An instrument

for consumer evaluation of web sites. Int. J. Electr. Commerce 11, 51–87. doi: 10.2753/

JEC1086-4415110302

Manfred, B., Verena, S., Daniela, S., and Daniel, H. (2012). Brand Authenticity:

Towards a deeper understanding of its conceptualization and measurement. Adv. Cons.

Res. 40:567.

Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., and Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value:

Conceptualization measurement and application in the catalog and internet shopping

environment. J. Retail. 77, 39–56. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00045-2

Murray, S. C. (1983). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and

fiascoes, by Irving L Janis. Presidential Stud. Q. 13, 654–656.

Olson, J. C., and Jacoby, J. (1972). “Cue utilization in the quality perception process,”

in Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research,

(Chicago), 3–5.

Orús, C., Gurrea, R., and Flavián, C. (2017). Facilitating imaginations through online

product presentation videos: Effects on imagery fluency, product attitude and purchase

intention. Electr. Commerce Res. 17, 661–700. doi: 10.1007/s10660-016-9250-7

Overmars, S., and Poels, K. (2015). How product representation shapes virtual

experiences and re-patronage intentions: The role of mental imagery processing and

experiential value. Int. Rev. Retail Distr. Consum. Res. 25, 236–259. doi: 10.1080/

09593969.2014.988279

Park, H. J., and Lin, L. M. (2020). The effects of match-ups on the consumer attitudes

toward internet celebrities and their live streaming contents in the context of product

endorsement. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 52:101934. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101934

Park, J., Lennon, S. J., and Stoel, L. (2005). On-line product presentation: Effects on

mood, perceived risk, and purchase intention. Psychol. Mark. 22, 695–719. doi: 10.1002/

mar.20080

Park, J., Stoel, L., and Lennon, S. J. (2008). Cognitive, affective and conative responses

to visual simulation: The effects of rotation in online product presentation. J. Consum.

Behav. 7, 72–87. doi: 10.1002/cb.237

Peterson, R. T., and Yang, Z. (2004). Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and

loyalty: The role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 21, 799–822. doi: 10.1002/mar.20030

Petit, O., Velasco, C., and Spence, C. (2019). Digital sensory marketing: Integrating

new technologies into multisensory online experience. J. Interact. Mark 45, 42–61. doi:

10.1016/j.intmar.2018.07.004

Podsakoff, P. M., and Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research:

Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 12, 531–544. doi: 10.1177/014920638601200408

Rintamäki, T., Kanto, A., Kuusela, H., and Spence, M. T. (2006). Decomposing the

value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions:

Evidence from Finland. Int. J. Retail Distr. Manag. 34, 6–24. doi: 10.1108/

09590550610642792

Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., Townsend, C., and Krishnan, R. (2015). The impact

of dynamic presentation format on consumer preferences for hedonic products and

services. J. Mark. 79, 34–49. doi: 10.1509/jm.13.0521

Ruiz, D. M., Gremler, D. D., Washburn, J. H., and Carrio ìn, G. C. (2008). Service

value revisited: Specifying a higher- order, formative measure. J. Bus. Res. 61, 1278–1291.

doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.015

Schlosser, A. (2003). Experiencing products in the virtual world: The role of goal and

imagery in influencing attitudes versus purchase intentions. J. Consum. Res. 30, 184–198.

doi: 10.1086/376807

Seiders, K. B., Berry, L. L., and Gresham, L. G. (2000). Attention, retailers! How

convenient is your convenience strategy? Sloan Manag. Rev. 41, 79–90.

Sjöblom, M., and Hamari, J. (2017). Why do people watch others play video games?

An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 30, 1–12.

doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.019

Svenson, O. (1992). Differentiation and consolidation theory of human decision

making: A frame of reference for the study of pre- and post-decision processes. Acta

Psychol. 80, 143–168. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(92)90044-E

Svenson, O., and Edland, A. (1987). Change of preferences under time pressure:

Choices and judgements. Scand. J. Psychol. 28, 322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1987.

tb00769.x

Szymanski, D. M., and Hise, R. T. (2000). E-satisfaction: An initial examination.

J. Retail. 76, 309–322. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00035-X

Verhagen, T., Vonkeman, C., and van Dolen, W. (2016). Making online products

more tangible: The effect of product presentation formats on product evaluations.

Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 19, 460–464. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0520

Verhagen, T., Vonkeman, C., Feldberg, F., and Verhagen, P. (2014). Present it like it

is here: Creating local presence to improve online product experiences. Comput. Hum.

Behav. 39, 270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.036

Visinescu, L. L., Sidorova, A., Jones, M. C., and Prybutok, V. R. (2015). The influence of

website dimensionality on customer experiences, perceptions and behavioral intentions:

An exploration of 2D vs. 3D web design. Inform. Manag. 52, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2014.

10.005

Vonkeman, C., Verhagen, T., and van dolen, W. (2017). Role of local presence in online

impulse buying. Inf. Manag. 54, 1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2017.02.008

Wang, E. S. (2010). Internet usage purposes and gender differences in the effects of

perceived utilitarian and hedonic value. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 13, 179–183.

doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0200

Frontiers in Psychology 11 frontiersin.org

fpsyg-14-1124675 February 2, 2023 Time: 15:21 # 12

Zhang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1124675

Wongkitrungrueng, A., Dehouche, N., and Assarut, N. (2020). Live streaming

commerce from the sellers’ perspective: Implications for online relationship marketing.

J. Mark. Manag. 36, 488–518. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2020.1748895

Wu, J. N., Wang, F., Liu, L., and Shin, D. (2020). Effect of online product presentation

on the purchase intention of wearable devices: The role of mental imagery and

individualism- collectivism. Front. Psychol. 11:56. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00056

Wu, K., Vassileva, J., Zhao, Y., Noorian, Z., Waldner, W., and Adaji, I. (2016).

Complexity or simplicity? Designing product pictures for advertising in online

marketplaces. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 28, 17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.08.009

Yoo, J., and Kim, M. (2014). The effects of online product presentation on consumer

responses: A mental imagery perspective. J. Bus. Res. 67, 2464–2472. doi: 10.1016/j.

jbusres.2014.03.006

Yue, L. Q., Liu, Y. M., and Wei, X. H. (2017). Influence of online product presentation

on consumer’s trust in organic food: A mediated moderation model. Br. Food J. 119,

2724–2739. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-09-2016-0421

Zhang, M., and Merunka, D. (2015). The impact of territory of origin on product

authenticity perceptions. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logistics 27, 385–405. doi: 10.1108/APJML-

12-2014-0180

Zhang, N., and Li, J. (2022). Effect and mechanisms of state boredom on consumer’s

livestreaming addiction. Front. Psychol. 13:826121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.82

6121

Zhu, Y., and Zhang, J. (2021). Influence of time pressure on consumer’s online

impulsive purchase: Moderating effect of transaction utility and perceived risk. J. Bus.

Econ. 7, 55–66.

Frontiers in Psychology 12 frontiersin.org