Page 1

FIELD DIRECTIVE

USE OF SAMPLING METHODOLOGIES IN

RESEARCH CREDIT CASES

INTRODUCTION

This paper will address questions frequently asked by examiners regarding the

use of sampling techniques in examining reported or claimed research credits. This

LMSB Directive is not an official pronouncement of the law or the Service’s position and

cannot be used, cited or relied upon as such.

Statistical sampling is quite often used in research credit cases for greater audit

efficiency. In fact, statistical sampling should be considered in a research credit case

whenever an excessive amount of time and resources would be needed to adequately

examine all of the taxpayer's projects. See IRM 42(18)3.4.

When a sampling procedure is contemplated, the examination manager should

meet with the Computer Audit Specialist ("CAS") and design a sample that will result in a

practical number of projects to examine with the desired sampling error. If it is

impossible to design such a sample, then the examiner should consider the alternative

sampling approaches described in this paper. If these recommended approaches are

not practical in the context of the facts in a particular case, the examination team may

also consider the use of a judgment sample. While a judgment sample will often require

less examination work than a statistical sample, a judgment sample requires the written

consent of the taxpayer while a valid statistical sample does not. Accordingly, this paper

addresses the use of statistical sampling and judgment sampling techniques.

Although the courts have not specifically addressed the validity of the Service's

use of statistical sampling in research credit cases,

1

the methodology set forth in IRM

42(18) has been approved by an outside expert on statistical sampling. Thus, the

Service is confident that its sampling methodology set forth in the Internal Revenue

1

Although there is no case law addressing the validity of the Statistical Sampling

Examination Program, IRM 42(18)0, the Service's use of statistical sampling has been

upheld and relied upon by courts in other contexts. See Norfolk Southern Corp. v.

Commissioner, 104 T.C. 13 (1995); Catalano v. Commissioner, 81 T.C. 8 (1983).

Page 2

Manual is statistically sound and legally defensible. Counsel, as well as the Department

of Justice, will support examinations which follow the Internal Revenue Manual

guidelines and the techniques recommended in this paper.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT STATISTICAL SAMPLING

1. How should examiners respond to taxpayers who contend that statistical

sampling cannot be used in research credit cases?

Some taxpayers have argued that research-related projects are not the type of

"fungible" units that are suitable for statistical sampling. A professional statistician

retained by the Service, however, has considered this argument and concluded that

research projects are an appropriate sampling unit. Furthermore, as discussed in this

paper, statistical sampling can also be used on employees, contractors, and contracts.

Taxpayers who are opposed to statistical sampling may prefer to choose a

"representative" sample of projects, then have the Service agree to apply the results

from the audit of the sample projects to all of the qualified research expenses at issue.

While this approach should be considered by examiners, it may not be possible to agree

on a "representative" sample. Furthermore, it may not be possible to agree on how to

apply the results of the audit of the sample to all the projects at issue. For this reason, it

may be necessary to apply statistical sampling in cases where the parties cannot agree

on an appropriate judgment sample or sampling methodology.

2. When should statistical sampling be used in research credit cases?

(a) Statistical sampling should be considered when it is impractical to

fully examine the reported or claimed research credit.

The following should be considered in determining whether it would be

impractical to fully audit the research credit:

(1) What types of projects are involved? Are there many similar or related

projects, or are there a variety of unrelated projects?

(2) Are most projects large (in terms of dollars and number of years

involved) or is the population mainly comprised of smaller projects?

(3) How much documentation exists on each project?

(4) How long would it take to conduct interviews of key employees who worked

on the projects? Are most project managers and other key project

personnel still employed by the taxpayer?

Page 3

(5) How many estimated audit hours would it take to review all projects?

(6) How much audit time can be devoted to the research credit issues?

(7) How many other (non-research credit) issues are under audit?

(8) How large is the audit team?

(b) Statistical sampling can be used in examining:

(1) Whether the research projects undertaken by the taxpayer involved

"qualified research" under section 41(d). If the taxpayer adopts project

accounting, a sample of projects would be selected to determine if the

projects involved "qualified research." If the taxpayer adopts cost center

accounting, then a sample of employees would be selected and the

projects worked on by these employees would be evaluated to determine if

they involved "qualified research."

(2) Whether employee wages were paid for "qualified services" under section

41(b)(2)(B). A selected sample of employees would be examined

to determine if an accurate portion of the employees' wages were paid or

incurred for engaging in qualified research or for directly supporting or

supervising qualified research.

(3) Whether fees paid to contractors were "contract research expenses"

under section 41(b)(3). A selected sample of contractors would be

examined to determine if they engaged in "qualified research." Also, a

selected sample of contractor agreements would be examined to

determine if the contracts comply with the requirements of sections 1.41-

2(a)(3), 2(e) and 5(d) of the Regulations.

(c) Statistical sampling can only be used in cases involving a significant

number of research projects, employees, or contractors.

Generally, if a research credit case involves fewer than 50 sampling units (i.e.,

projects, employees, contractors and/or contracts), then traditional statistical sampling

approaches may not enhance audit efficiency. In these cases examiners may consider

one of the alternative means of reducing the scope of the audit that are discussed in this

paper.

In cases with greater than 50 sampling units, the exam team must consider

whether it has the resources to conduct a full review of all projects. If the total number of

Page 4

projects is too large to conduct a full review, then statistical sampling should be used in

examining the research credit issue.

(d) Statistical sampling is particularly useful in the typical case involving

a few large projects and many small projects.

In many research credit cases, a significant portion of the expenses are incurred

in a few large projects, with the remaining expenses allocated to many small projects. If

the agent only examines the large projects, then there is no legally sustainable basis for

adjusting the small projects. In this instance, the agent would have to allow the smaller

projects, even though there is a greater likelihood of finding a basis for disallowing small

projects. This is particularly true in internal use software cases, since taxpayers have

the burden of proving that they committed substantial resources to the software

development. Norwest v. Commissioner, 110 T.C. 454, 499 (1998), appeals pending

sub nom., Wells Fargo & Co. v. Commissioner (8th Cir. Nos. 99-3878, 99-3883, 99-

4071). Also, taxpayers usually have more documentation relating to their largest

projects, and probably have more employees available to provide information about

these projects. It is therefore particularly important to consider statistical sampling of the

smaller projects. In fact, sampling the smaller projects is the only way of ensuring a

legally sustainable basis for disallowance where the agent does not review these

projects in full.

3. Should the examination be limited to only the largest projects?

No. Where there are only a few large projects these projects should be examined

in full and not be included as part of the statistical sample. The statistical sampling

approach should be used to resolve all but the large projects. Taxpayers will often

propose, however, that the audit strategy simply involve reviewing a few large projects

(i.e., the top five). This approach is generally unacceptable because it would result in

allowing the expenses paid or incurred in the smaller projects. Alternatively, a taxpayer

may propose a review of the large projects, with the results projected to the population

of smaller projects. This approach would not, however, provide a statistically sound

result since the largest projects are generally more likely to meet the requirements for

qualified research, thus skewing the results in favor of allowing a larger credit than if the

agent reviewed the smaller projects.

Where a taxpayer has projects of varying sizes, the recommended approach is to

conduct a statistical sample using stratification. For example, a taxpayer's small projects

(e.g., projects with up to $500,000 in research expenses) may be grouped into the same

stratum, and if there are too many projects in this category to review in full, a sample of

projects from this group would be reviewed, with the results projected in a statistically

valid manner. The next question examines stratification in more detail.

Page 5

4. How should projects be stratified in a statistical sample of a research credit

case?

Where similar projects are divided into separate groups, this is referred to as

"stratification" and each group represents a "stratum." There are a number of ways to

stratify projects in a research credit case. For example, projects can be stratified based

on the dollar amount of claimed qualified research expenses (i.e., stratify into large,

medium, and small projects). Projects can also be stratified based on the type of

research project (i.e., in-house, vendor, maintenance, enhancement, internal-use, or

commercial software).

The following example illustrates how stratification has been traditionally used in

research credit cases. Assume the taxpayer's research credit claim involves 240

internal-use software projects. After consulting with a CAS, the examination team

considers breaking out the population of projects into the following cost categories:

Total Costs Number of Projects

Over $ 10,000,000 4

$1,000,000 - $3,000,000 25

$ 250,000 - $1,000,000 130

Under $250,000 81

TOTAL 240

The projects in the over-$10 million category are much larger than the rest of the

group, and since there are only 4 projects in this group, the agent should review all of

these projects. The results of this review would not be projected to the rest of the

projects.

Next, there are only 25 projects with costs ranging from $1,000,000 to

$3,000,000, so statistical sampling is not a viable option for this stratum. The examiner

will therefore need to examine these 25 projects.

The next stratum has 130 projects ranging from $250,000 to $1,000,000. This

group is large enough to sample, so the audit team could select 30 projects from this

group to sample. The results of this review would be projected to the population of 130

projects within this stratum.

The last stratum has 81 projects under $250,000. The examiner could also select

a sample of 30 projects from this group, the results of which would be projected to the

population of 81 projects in this stratum.

Based on this sampling approach, the examiner determines whether 240 projects

involved qualified research by examining 89 projects.

Page 6

5. What if the total number of projects is so large that even the statistical

sample results in too many projects to audit effectively?

In the example above, the agent may determine that given existing audit

resources, a complete review of 89 projects would be impractical. The taxpayer may

also object to a full review of 89 projects as an excessive and impractical audit. Thus,

the taxpayer may be willing to consider reasonable proposals to limit the scope of the

audit. Provided below are several ways to reduce the total number of projects selected

for a full review.

2

First, the examination team may want to consider re-stratifying the projects, since

modifying the number of strata or boundaries may reduce the number of sampled

projects to review. Stratification is used to reduce the variability between the reported

value of sample items. If the variability between sampling units in a stratum is reduced

the number of projects that are reviewed may also be reduced. Grouping sampling units

with similar characteristics may reduce variability.

During the planning stage, the examiner should discuss with the CAS the

maximum number of projects the team could likely review in full. With this information,

the CAS could formulate a sampling methodology to match the resources of the

examination team. The CAS is specially trained to determine the optimum sample size

and boundary ranges. In the above example, the CAS may consider modifying the

middle two strata so that there is one stratum of projects with ranges between $250,000

and $750,000 and another with ranges between $750,000 and $3,000,000. This

category would have 155 projects that may be resolved based on an examination of 30

projects, 15 in each stratum. This would serve to reduce the total number of projects to

review from 89 projects to 64 projects. Alternatively, reducing the number of reviewed

projects within each stratum also reduces the number of projects to review. However,

the result may cause an increase in sampling error.

3

Should the sampling error be

2

It is important to keep in mind the advice set forth in response to question 3, i.e.,

relating to cases where the majority of the expenses were incurred in a few large

projects. In these cases the large projects should be audited and excluded from the

sample.

3

Increasing strata size, eliminating strata, or reducing the number of reviewed

items per stratum may all result in a larger sampling error. However, based on the

policies set forth in the Internal Revenue Manual, the taxpayer would get the benefit of

the increased sampling error (sampling error as used by the IRS is the standard error

multiplied by a 95% 1 sided t factor.) See IRM 42(18)4.1. Thus, the audit team would

have to decide whether the decrease in the number of projects to review is worth the

Page 7

judged unacceptably large, the sampling plan should contain an option to increase the

sample size.

Although re-stratification may significantly reduce the number of projects

that need to be reviewed (from 89 to 64), there may still be too many projects for the

audit team to review. If this occurs, a second approach is to engage an outside expert in

the particular field of research at issue, and have the expert evaluate a smaller number

of projects within the sample. In this example, the examiner would request the

assistance of a software expert from the LMSB Division's MITRE Expert Program. The

MITRE expert would select a smaller number of projects from the sample of 64 which

the expert considers representative of the entire population of software development

projects. Experts are often able to select a very small number of projects as a

representative sample. For example, in Norwest, the parties selected 8 of the 67

internal use software projects at issue as a representative sample. In light of this

background, assume that the expert determines that 6 projects provide a representative

sample of the total population of 64 projects.

4

Next, the expert would review the 6 projects and prepare a written report. While

the expert is evaluating these projects, the audit team should be examining whether the

taxpayer's claimed costs on these 6 projects represent "qualified research expenses"

under section 41(b)(1). Specifically, were the taxpayer's in-house wages paid for

"qualified services" within the meaning of section 41(b)(2)(B)? Do the taxpayer's

claimed supplies qualify under section 41(b)(2)(C)? Do payments to contractors and

vendors meet the requirements for contract research under sections 41(b)(3) and 1.41-

2(e) of the Regulations?

Assume the expert determines that 2 of the 6 projects he evaluated involve

"qualified research." I.R.C. § 41(d). Also assume that the audit team determined that all

of the claimed expenses relating to the two qualifying projects are qualified research

expenses under section 41(b). The next step would be to propose a resolution of the

research credit issue based on the expert's findings. If the taxpayer accepts the

proposed resolution, then both the taxpayer and the Service have saved substantial time

and resources, since the issue was resolved based on a review of only 6 projects.

If the taxpayer does not accept the resolution based on the expert's initial

findings, the audit team would have to go forward and review the remaining 58 projects

in order for the sample to be statistically valid. Sufficient audit time should be allocated

increase in sampling error, which inures to the benefit of the taxpayer.

4

The selection of projects could be based on either a random or non-random

sample. The non-random sample could be selected either by the Service's expert, or by

the taxpayer. If the taxpayer chooses the sample, the Service's expert should determine

whether the selected projects are a fair representation of the projects as a whole.

Page 8

for this purpose in the event the taxpayer chooses not to accept the Service's proposal

for resolution.

However, where the taxpayer rejects the offer, the taxpayer may decide not to

submit any additional documentation after reading the expert's initial report, because the

taxpayer disagrees with the expert's evaluation and believes that further examination

would be fruitless. In this situation, the expert should review all documentation that the

Service has in its possession with respect to all 64 projects in the sample. If the

taxpayer refuses to submit additional documentation or allow additional interviews, then

the expert's report on the 64 projects would be based on information the taxpayer

submitted since the commencement of the audit.

5

In such circumstance, the expert may

disallow the remaining projects in the sample for lack of substantiation. This

disallowance would be legally sustainable and should be upheld by Appeals since the

audit team reviewed all 64 projects in the sample, and thus, the sample is statistically

sound.

A third approach is to enter into a written agreement with the taxpayer to have the

research credit issue resolved through an examination of an agreed representative

sample. This approach was adopted by the parties in Norwest. In this case, the parties

agreed that the Tax Court's determination of qualified research expenses in 8 sample

projects would determine the amount of qualified research expenses for all of the 67

projects at issue.

6

If the taxpayer wishes to enter a written agreement with the Service binding the

parties to a sampling approach, this agreement must be reviewed by Counsel to

determine whether the agreement is legally enforceable and binding on the parties. This

5

We recommend that you consult with your local Counsel's office to determine if it

is advisable to issue a summons to get information needed to determine if the taxpayer

engaged in qualified research. Counsel recommends the use of summons in

appropriate cases.

6

The 8 projects were not weighed with respect to their size, or any other factor. All

8 projects were accorded the same weight in applying the results to the remaining 59

projects. For more information about the agreement between the Service and the

taxpayer in Norwest, contact the Technical Advisor (Research Credit).

Page 9

approach provides a legally defensible determination only if the agreement between the

taxpayer and the Service is legally enforceable. See question 10 for further discussion

on statistical sampling agreements.

Another way of reducing the scope of the audit is to use the employee as the

sampling unit, rather than the project. As set forth in the next question, the examiner

may be able to resolve a large research credit case by considering only the projects

worked on by the employees who are in the sample population. This could result in the

resolution of a large research credit claim based on interviewing 30 company

employees. As discussed in the next section, this method is not limited to cases

involving taxpayers that adopt cost-center accounting. The employee could also be

effectively used as the sampling unit even where the taxpayer based its claim on project

accounting records.

Finally, in cases where the taxpayer's claim is based on research undertaken by

contractors, choosing the contract as the sampling unit may be an efficient way to audit

the claim. Using the contract as a sampling unit is discussed in detail in response to

question 7 below.

6. How can statistical sampling be used where the taxpayer accounts for its

qualified research expenditures under a cost center approach and, thus,

costs are not broken down by project?

Where the taxpayer's research credit claim is computed under the cost center or

departmental approach, the taxpayer usually cannot break down its costs on a project by

project basis. Instead, the taxpayer's qualified research expenses are usually based on

claiming a percentage of certain departments or cost centers. Under these

circumstances, the employee should be chosen as the sampling unit, instead of the

project. The following example shows how statistical sampling is used where the

employee is the sampling unit.

Assume the taxpayer utilized the cost center approach when it computed its

research credit for 1992,

7

and claims that 50 percent of the wages paid to Information

Technology (IT) department employees are qualified research expenses. This was

based on an estimate made by the head of the IT department. Although he cannot

identify specific employees who worked on specific projects, he nevertheless believes

that 50 percent is a fair estimate of the department as a whole. This means that

approximately 200 employees out of the total IT staff of 400 engaged in qualified

research. The taxpayer then determined the average salary of its IT staff and computed

its qualified research expenditures by multiplying the average salary by 200. Since the

7

A one year example is used here for simplicity. For multi-year allocation

techniques, see question 8 below.

Page 10

average salary was $50,000, the taxpayer claimed that it incurred $10,000,000 (200 x

$50K) in qualified research expenses.

Since the taxpayer cannot break down the $10,000,000 of IT department

expenses into the projects the employees worked on, the CAS would statistically sample

employees within the IT department during 1992. Thus, 30 IT employees are chosen at

random from the taxpayer's W-2 tapes.

8

8

By reviewing the taxpayer's W-2 tapes, the examiner is also verifying the

taxpayer's $10,000,000 figure. For example, if the W-2 tapes only add up to

$9,000,000, then the examiner should make this adjustment to the claimed qualified

research expenses.

Next, the examiner would request, at a minimum, the following documentation

through an IDR:

(1) What project(s) did each of these 30 employees work on in 1992?

(2) What was the employee's title and job description?

(3) What are the employee's credentials (education, training, etc)?

(4) What specific activities did this individual perform on each project (i.e.,

was the employee engaged in qualified research, or in direct

supervision or direct support of the research)?

(5) What did each project involve? (i.e., ask for all documentation about

the projects listed for this employee to determine whether the project

meets the requirements for qualified research).

Once this documentation is reviewed, the examiner can determine the total

number of projects these 30 employees worked on in 1992. The examiner will likely find

that many of the sampled employees worked on the same project or projects in 1992.

Assume the documentation indicates that these employees worked on a total of 50

separate projects in 1992.

Next, the audit team would have to make a determination as to whether it can

fully review 50 projects. If not, then the approaches suggested in question 4 above

should be considered. For example, the MITRE expert could prepare an initial report

Page 11

based on a review of a smaller number of projects from the list of 50. However, assume

for this question that the exam team intends to fully review all 50 projects.

The next step would be to interview each of the 30 sampled employees. This is

unnecessary if the documentation submitted by the taxpayer reveals whether the

projects involved qualified research, or whether the employees provided qualified

services. Each interview would try to uncover what each project involved and the work

performed by the employee on the project. For software cases, a MITRE expert could

be used in conducting these interviews.

The interviews with each employee should also explore whether the taxpayer's

estimate of the amount of qualified research expenses is reasonable. The cost center

approach is based on an estimate of expenses, so the interviews and requests for

documents should focus on the key assumption underlying this estimate, i.e., that 50%

of the employees in the department worked on qualified research.

Once the requested documentation is reviewed and the interviews are conducted,

the examiner will determine whether any of the 50 projects meet the tests for qualified

research. If a MITRE expert is used, the expert would prepare a written report on this

issue. Assume in this example that the MITRE expert found that 25 projects out of 50

qualify for the credit.

The examiner's next step is to determine what percentage of time these 30

employees spent on the 25 qualified projects. Specifically, the examiner must determine

whether these 30 employees were engaged in "qualified services" on any of the 25

qualifying projects in 1992. See I.R.C. § 41(b)(2).

Once these determinations are made with respect to each employee, the

examiner can calculate the percentage of allowable expenses. For example, assume

the examiner determined that the 30 employees expended anywhere from zero to 40

percent of their total wages in 1992 performing qualified services on the 25 qualifying

projects, with 10 percent as the average. Thus, the examiner would propose to allow 10

percent of the IT department's total wages (plus the sampling error) in 1992 as qualified

research expenditures, as opposed to the taxpayer's original estimate of 50 percent.

Thus, using the employee as the sampling unit, the examiner was able to

effectively audit a large research credit claim based on a review of the projects 30

employees worked on during 1992. In fact, in large research credit cases, the preferred

approach may be to use the employee as the sampling unit, even where the taxpayer

can break down its costs by project. An initial determination would have to be made by

the exam team, along with the CAS, as to which sampling unit (the employee or the

project) would achieve the best mix of audit efficiency and statistical accuracy.

Page 12

7. How can statistical sampling be used to determine whether fees paid to

contractors are contract research expenses under section 41(b)(3)?

Payments to contractors are qualified contract research expenses if the following

requirements are satisfied: (1) the payments were for engaging in qualified research, or

direct supervision or direct support of qualified research; (2) the payment was not

contingent upon the success of the research; and (3) the taxpayer retained a right to the

research results. Treas. Reg. § 1.41-2(e). Statistical sampling can be used to address

each of these questions, and is a particularly effective audit tool in large cases involving

hundreds of contracts. The following example illustrates how sampling can be used in

cases where the taxpayer is claiming that payments it made to contractors are contract

research expenses:

Assume the taxpayer's research credit claim is calculated on $50,000,000 of

qualified research expenses, and $40,000,000 of this amount is attributable to contract

research. The taxpayer has identified 300 contracts for which payments were made

during the period in question. The contract will serve as the sampling unit. The CAS

randomly selects 30 contracts that these contractors worked on during the period in

question. The audit team will review these 30 contracts, focusing on the legal

requirements listed above. Assume that the team develops this issue, evaluates the

work performed by the contractors and determines that the contractors in 20 out of the

30 contracts engaged in qualified research. Next, the team focuses on whether the

taxpayer had a right to the research results, and whether the payments made to the

contractor were contingent upon the success of the research. Treas. Reg. § 1.41-

2(e)(2); see Fairchild Industries, Inc. v. United States, 71 F.3d 868, 872 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

Assume that out of the 20 contracts which involved qualified research, only 15 met these

additional legal requirements for contract research.

The agent would then propose an adjustment based on the expenditures made

under the qualifying contracts relative to the total amount expended on all of the

contracts in the sample. For example, if $2,000,000 is expended under the 30 contracts

in the sample and it is determined that $1,000,000 was spent under the 15 qualifying

contracts, then the examiner would allow 50% ($1m/$2m) (plus the sampling error) of all

of the contract research expenditures. Thus, by using statistical sampling, the team

was able to arrive at an adjustment for a population of 300 contracts by a review of only

30.

9

9

As to the remaining $10,000,000 of in-house expenses in the example, the

examination team would have to review these expenses separately, perhaps using one

of the other stat sampling techniques discussed in this paper.

Page 13

Statistical sampling can also be used in cases where the contractor is claiming

the credit for research it performed for another entity. In this instance, the

taxpayer/contractor must prove that it engaged in "qualified research" and the research

was not "funded." Treas. Reg. § 1.41-5(d); Fairchild, 71 F.3d at 868 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

To test whether the research was funded, statistical sampling can be used to determine

whether, based on a sample of contracts, the contractor retained "substantial rights" in

the research, and whether the payments were "contingent upon success." Treas. Reg.

§ 1.41-5(d). Sampling would be particularly effective where the contractor has many

contracts with the same customer (e.g., a governmental entity), and/or the contracts are

fairly uniform and are governed by the same regulatory rules (e.g., Federal Acquisition

Regulations System).

8. How can statistical sampling be used where the research credit claim

involves more than one year?

Most research credit claims involve multiple years. However, it is not necessary

to do a separate sample for each year. Instead, the population will consist of all projects

for all years (i.e., combine all the years and treat as one claim). Then, a sample of

projects, employees or contracts (depending on the sampling unit chosen) will be

selected for review. Once the agent has reviewed the sample, the agent will arrive at an

overall adjustment (for example, allowing 40 percent of the claim). Then this adjustment

would be allocated over the multiple year period to arrive at an adjustment for each year.

There are a number of ways to make this allocation and one such method is

outlined in the appendix to this paper. The example in the appendix has been used by

the Service in several cases and is based on consultations with an outside expert on

statistical sampling. For specific guidance on this or any other allocation method,

contact your local CAS group.

9. Can the results of a statistical sample for one year be projected back or

forward to other years which were not part of the sample?

No. Taxpayer's often request that the exam team review a sample of projects

from a recent year, and project the results of their findings back to an earlier year.

Taxpayers favor this approach because they have ready access to documentation

relating to projects undertaken in recent years. The taxpayer may attempt to justify this

methodology by arguing that the projects in the recent years are similar to the projects in

earlier years thereby providing a representative sample for resolving the claims for the

earlier periods. The exam team should not accept this audit approach for several

reasons. First, the examiner cannot readily verify whether the taxpayer's recent projects

are in fact representative of the type of projects that took place in earlier years, since

documentation from the earlier years probably does not exist (which is why the taxpayer

wants to extrapolate). Second, there is no statistical basis for this type of extrapolation

because the older years were not part of the sample.

Page 14

In order to effectively audit earlier years (the base years for example), the exam

team should conduct a separate statistical sample of these years, rather than

extrapolate from the current years' findings.

10. How should examiners ensure that their sampling methodology will be

upheld by Appeals and Counsel?

Appeals and Counsel will support an exam team's statistical sample if the

sampling methodology is in accordance with sound statistical sampling principles, as set

forth in this paper and in the Internal Revenue Manual. Appeals and Counsel may not,

however, support an adjustment that disallows a taxpayer's non-reviewed smaller

projects because the examiner decided to spend the audit time reviewing only the

largest projects. In general, disallowed projects that were not reviewed would only be

upheld if the disallowance was based on a statistical sample or a legally valid agreement

with the taxpayer to apply the results of a limited audit to all of the credit at issue.

In addition, the examiner should attempt to secure the taxpayer's agreement on

the method in which the sampling results will be allocated over a multi-year period. In

fact, it is preferable to obtain a written agreement with the taxpayer on all aspects of the

statistical sample. Currently, the Service does not have a model statistical sampling

agreement. The legality and binding effect of any such agreement would have to be

determined by Counsel on a case-by-case basis. However, the agent may consider

using a closing agreement under section 7121 to bind the parties to the sampling

methodology. Specifically, an Accelerated Issue Resolution (AIR) agreement (a form of

closing agreement) could be utilized in agreeing in advance to the sampling

methodology. See Rev. Proc. 94-67.

Page 15

APPENDIX

Multi-Year Allocation Example

As discussed in question 7, the following is an example of how to allocate a

proposed adjustment over multiple years where the taxpayer's research credit claim

involves more than one year. Assume that the taxpayer claimed the credit for the three

year period from 1990 through 1992 and that the exam team divided the projects into 3

strata. The five basic steps followed in the example on the next page are:

(1) Within each stratum, find the total adjustment that is associated with each

of the 3 years. This produces 9 amounts.

(2) Multiply each of these 9 amounts by the ratio of its stratum size (number of

population projects in that stratum) to the sample size within that stratum.

Note for stratum 3 (the 100% stratum), this ratio is 1.

(3) Add together the 3 numbers corresponding to each year. This produces

three amounts; one for each year.

(4) Divide each of these 3 amounts (the year totals) by the grand total for the 3

years.

(5) Multiply each of the resulting ratios by the lower bound to obtain the

allocation of the total adjustment to each year.

This method makes the best use of the sampling data and results in a reasonable

allocation. For specific questions about this method, or other ways of making the

allocation, contact your local CAS group.

Page 16

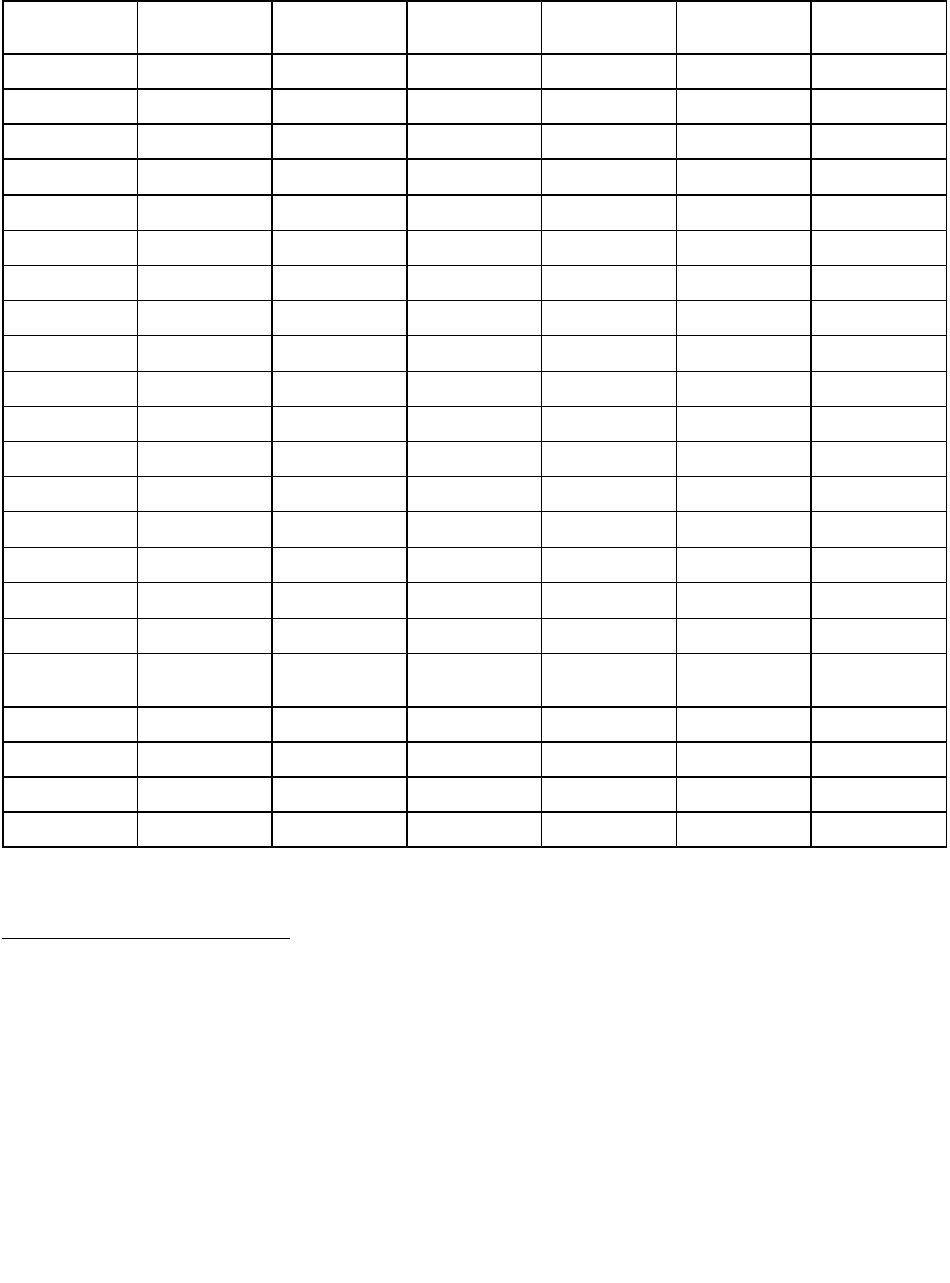

Stratum Year Adjustment (a) Stratum Size

(b)

Sample Size

(c)

Ratio (b/c) Result (a x d)

1 1990 10,000 600 30 20 200,000

2 1990 5,000 300 30 10 50,000

3 1990 100,000 50 50 1 100,000

Year 1 Total =

350,000

Stratum

1 1991 20,000 1,200 30 40 800,000

2 1991 10,000 600 30 20 200,000

3 1991 125,000 50 50 1 125,000

Year 2 Total =

1,125,000

Stratum

1 1992 50,000 900 30 30 1,500,000

2 1992 20,000 450 30 15 300,000

3 1992 225,000 50 50 1 225,000

Year 3 Total =

2,025,000

Grand Total =

3,500,000

Year Adjustment Ratio

1

Lower Bound

2

Allocation to

each year

1990 350,000 10%

3,000,000

= 300,000

1991 1,125,000 32.14% 3,000,000 = 964,200

1992 2,025,000 57.86% 3,000,000 = 1,735,800

Totals 3,500,000 100% 3,000,000

1

This ratio is the adjustment for each year divided by the total for all 3 years. For

example, the 10% ratio for 1990 was computed by dividing 350,000 by 3,500,000.

2

This "lower bound" is the point estimate minus the sampling error. The lower

bound figure is usually computed by using the IRS statistical sampling software.

Essentially, it's the total adjustment for all the years, which then must be allocated over

each year, as the example illustrates.