K-12 EDUCATION

Characteristics of

School Shootings

Report to Congressional Requesters

June 2020

GAO-20-455

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-20-455, a report to

congressional requesters

June 2020

K-12 EDUCATION

Characteristics of School Shootings

What GAO Found

GAO found that shootings at K-12 schools most commonly resulted from

disputes or grievances, for example, between students or staff, or

between gangs, although the specific characteristics of school shootings

over the past 10 years varied widely, according to GAO’s analysis of the

Naval Postgraduate School’s K-12 School Shooting Database. (See

figure.) After disputes and grievances, accidental shootings were most

common, followed closely by school-targeted shootings, such as those in

Parkland, Florida and Santa Fe, Texas.

K-12 School Shootings by Kind, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

The shooter in about half of school shootings was a student or former student; in

the other half, the shooter had no relationship to the school, was a parent,

teacher, or staff, or his or her relationship to the school was unknown, according

to the data. When the shooting was accidental, a suicide, or school-targeted, the

shooter was more often a student or former student. However, when the shooting

was the result of a dispute or grievance, the shooter was someone other than a

student in the majority of cases. For about one-fifth of cases, the shooter’s

relationship to the school was not known. (See figure.)

View GAO-20-455. For more information,

contact

Jacqueline M. Nowicki at (617) 788-

0580

or nowicki[email protected].

Why GAO Did This Study

In addition to the potential loss of

life, school shootings can evoke

feelings of profound fear and anxiety

that disturb a community’s sense of

safety and security. Questions have

been raised about whether schools’

approaches to addressing student

behavior are a factor in school

shootings. These approaches

include discipline that removes the

offending students from the

classroom or school, and

preventative approaches meant to

change student behaviors before

problems arise.

GAO was asked to examine school

shootings, including the link between

discipline and shootings. This report

examines 1) the characteristics of

school shootings and affected

schools, and 2) what is known about

the link between discipline and

school shootings. To do so, GAO

analyzed data on school shootings

and school characteristics for school

years 2009-10 through 2018-19; and

conducted a literature review to

identify empirical research from

2009 to 2019 that examined

discipline approaches in school, and

the effects of these approaches on

outcomes of school gun violence,

school violence, or school safety.

GAO also interviewed selected

researchers to gather perspectives

about challenges and limitations in

conducting research on school

discipline and school shootings.

The characteristics of schools where shootings

occurred over the past 10 years also varied by

poverty level and racial composition. Urban,

poorer, and high minority schools had more

shootings overall, with more characterized as a

dispute or grievance. Suburban and rural,

wealthier, and low minority schools had more

suicides and school-targeted shootings, which

had the highest fatalities per incident. Overall,

more than half of the 166 fatalities were the

result of school-targeted shootings.

The location of the shootings more often took

place outside the school building than inside

the school building, but shootings inside were

more deadly, according to the data. Shootings

resulting from disputes occurred more often

outside school buildings, whereas accidents

and school-targeted shootings occurred more

often inside school buildings. (See figure.)

GAO found no empirical research in the last 10

years (2009-2019) that directly examined the

link between school discipline and school

shootings. According to literature GAO

examined and five study authors GAO

interviewed, various factors contribute to the

lack of research examining this particular link,

including that multiple and complex factors

affect an individual’s propensity toward

violence, making it difficult to isolate the effect

of any one factor, including school discipline.

K-12 School Shootings by Shooting Location and Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

Notes: The location of one of the 318 incidents was unknown, and therefore, excluded from this analysis. As a result, the total incidents in this analysis is

317. GAO combined three categories from the K-12 School Shooting Database into an “Outside the school building” category: outside on school

property, off school property, and on school bus.

K-12 School Shootings by Shooter, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

Notes: Percentages do not add to 100 percent, due to rounding. “Unknown,” as recorded in the K-

12 School Shooting Database, includes incidents in which the shooter was identified but the

shooter’s relationship to the school could not be determined. “Other” combines four categories from

the K-12 School Shooting Database: intimate relationship with victim, multiple shooters, students

from a rival school, and non-students using athletic facilities/attending game.

Page i GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Letter 1

Background 4

Characteristics of Shooting Incidents and Schools Varied 12

Empirical Research Does Not Directly Examine Link between

Discipline and School Shootings 26

Agency Comments 30

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 31

Appendix II Additional Data Tables and Figure 44

Appendix III Summary and Table of Studies Included in Literature Review 47

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 51

Tables

Table 1: Examples of Risk and Protective Factors That Influence

Youth Violence 5

Table 2: School Shootings and Fatalities/Casualties by Kind of

Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 15

Table 3: Shooter Relationship to School by Kind of Shooting,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 17

Table 4: Number of Shootings Inside and Outside the School

Building by Shooter’s Relationship to School, School

Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 19

Table 5: GAO Categories of School Shootings 34

Table 6: Regions in the U.S. by State 36

Table 7: GAO Consolidation of Time Period from the K-12 School

Shooting Database 36

Table 8: GAO Consolidation of Shooter Relationship to School

from the K-12 School Shooting Database 37

Table 9: GAO Consolidation of Location from the K-12 School

Shooting Database 37

Contents

Page ii GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Table 10: Locale Variables Used from the Common Core of Data

(CCD) 38

Table 11: Criteria Used to Screen Literature on the Role of

Approaches to Discipline in School Shootings 41

Table 12: School Shootings and Fatalities/Casualties by Shooting

Location, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 45

Table 13: Time of Day of School Shootings by Kind of Shooting,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 45

Table 14: Month of Shooting by Kind of Shooting, School Years

2009-10 through 2018-19 45

Table 15: Studies Meeting Inclusion Criteria for Literature Review 47

Figures

Figure 1: Nonexclusionary Approaches to Address to Student

Behavior 11

Figure 2: School Shootings by Kind of Shooting, School Years

2009-10 through 2018-19 14

Figure 3: School Shootings by Shooter’s Relationship to School,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 16

Figure 4: School Shootings by Shooting Location and Kind of

Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 18

Figure 5: School Shootings by School Level and Kind of Shooting,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 20

Figure 6: School Shootings by Free or Reduced Price Lunch

Eligibility and Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10

through 2018-19 22

Figure 7: School Shootings by Minority Enrollment and Kind of

Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 23

Figure 8: Map of K-12 School Shootings in the United States,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 24

Figure 9: School Shootings by Locale and Kind of Shooting,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 25

Figure 10: Number of School Shooting Incidents Over Time,

School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19 46

Page iii GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

June 9, 2020

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Chairman

Committee on Education and Labor

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jerrold Nadler

Chairman

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

According to a 2018 Pew Research Center Survey, a majority of

American teenagers—especially those who are not white or are from

lower income families—are worried about the possibility of a shooting

happening at their school.

1

Since the 1999 shooting at Columbine High

School, almost all K-12 public school districts have developed and

adopted procedures to follow in the event of a shooting, and most

currently conduct active shooter drills, as we reported in 2016.

2

In

addition to the loss of life often resulting from school shootings, a

shooting that occurs in school can profoundly disturb a community’s

sense of safety and security and may have lasting effects for students,

teachers, principals, and parents. As a result of their trauma, students can

experience fear, anxiety, worry, difficulty concentrating, angry outbursts,

and aggression.

3

Students who experience the trauma of a school

shooting might also perform poorly in school or attempt to harm

themselves.

4

Further, questions have been raised about whether schools’

approaches to addressing student behavior are a factor in school

shootings. These approaches include discipline that removes the

1

The survey of teens was conducted in March and April of 2018, shortly after the shooting

at a high school in Parkland, Florida, on February 14, 2018. Nikki Graff, A majority of U.S.

teens fear a shooting could happen at their school, and most parents share their concern

(Pew Research Center, Apr. 18, 2018).

2

GAO, Emergency Management: Improved Federal Coordination Could Better Assist K-

12 Schools Prepare for Emergencies, GAO-16-144 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2016).

3

K. Guarino and E. Chagnon, Trauma-sensitive schools training package. (Washington,

D.C.: National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, 2018).

4

K. Guarino and E. Chagnon.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

offending students from the classroom or school, and preventative

approaches meant to change student behaviors before problems arise.

You asked us to provide information on school shootings, including

information on whether the way students are disciplined in schools might

be a factor in school shootings. This report examines (1) the

characteristics of K-12 school shooting incidents and the characteristics

of affected schools, and (2) what is known about whether different

approaches to discipline in school play a role in school shootings.

For the first objective, we developed a definition of school shootings to

create a list of school shootings based on existing datasets, and matched

the list of shootings with Department of Education (Education) data on

school characteristics. Specifically:

• Because there is no uniform definition of a school shooting, we

developed a definition of school shootings for the purposes of our

analysis, by reviewing research on the topic of school shootings, and

by reviewing and comparing definitions used in various datasets, such

as the National Center for Education Statistics School Survey on

Crime and Safety and Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection. To

ensure we focused on instances where students or staff were at risk,

we defined a school shooting as “any time a gun is fired on school

grounds, on a bus, during a school event, during school hours, or right

before or after school.”

5

,

6

Appendix I provides more information on

how we developed our definition.

• Although the dataset we used captures school shooting incidents from

1970 to the present, we focused our analysis on the past 10 school

years (2009-10 through 2018-19) to reflect the types of shootings

occurring in today’s schools. To develop a list of shootings, we

applied our definition by comparing it to the description of each

shooting occurring within this 10-year period in the Naval

5

For our analysis, we included four incidents in which a gun was brandished due to the

severity of the incidents. For example, the shooter initially made threatening gestures with

a firearm, but was stopped prior to a shot being fired; for example, if the shooter was

tackled.

6

This definition includes instances in which the gun was fired onto school grounds or at a

school bus, even if the shooter was outside of school grounds or outside of the school bus

when they fired. In addition, this definition includes all times where school staff and

teachers, including support and custodial staff, were on school grounds in their official

capacity with the school (e.g. on duty, at school meeting).

Page 3 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Postgraduate School’s K-12 School Shooting Database

7

—the dataset

on which we primarily relied-—and the Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI) Active Shooter reports.

8

We primarily relied on the

K-12 School Shooting Database because we determined it to be the

most widely inclusive database of K-12 school shootings (i.e.,

compiling every instance a gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits

school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims,

time of day, or day of week), and therefore most appropriate for our

purpose. We included on our list, all shootings that met our criteria

regardless of the shooter’s intent (e.g., accidents and suicides). For

purposes of our report, we categorized shootings identified in the

FBI’s Active Shooter reports as “school-targeted.”

9

See appendix I for

details on the categories of school shootings we identified.

• To develop our unique dataset on characteristics of schools that

experienced school shootings, we used Education’s Common Core of

Data (CCD), which is the agency’s primary database on public

elementary and secondary education in the United States. We

matched and then merged the school characteristics from the CCD,

such as grade level and locale (urban, suburban, town, and rural),

with our list of school shootings.

• To assess the reliability of the data in the K-12 School Shooting

Database, we interviewed the researchers who developed and

7

The K-12 School Shooting Database was developed by the Naval Postgraduate

School’s Center for Homeland Defense and Security which conducts a wide range of

programs to develop policies, strategies, programs and organizational elements to

address terrorism, natural disasters and public safety threats. The programs are

developed in partnership with and sponsored by the National Preparedness Directorate at

the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The K-12 School Shooting

Database (https://www.chds.us/ssdb/) is an open-source database of information from

various sources including peer-reviewed studies, government reports, and media sources.

8

The FBI defines an active shooter as one or more individuals actively engaged in killing

or attempting to kill people in a populated area. The FBI compiles active shooter incidents

to assist law enforcement in preventing and responding to these incidents. For example,

see: Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) Center at Texas

State University and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice,

Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2018 (Washington, D.C.: 2018).

9

We define school-targeted incidents as shootings that were targeted generally toward

school staff or students on school premises, but that were generally indiscriminate in

terms of specific victims. These include incidents of hostage standoffs, indiscriminate

shootings targeting the school staff and personnel, and active shooter incidents as

categorized by the FBI. School-targeted shootings may also include incidents in which a

specific victim was targeted because of their relationship to the school (e.g., student,

principal, staff, school resource officer, etc.).

Page 4 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

maintain the K-12 School Shooting Database and compared that data

to other databases with similar data on school shootings. To assess

the reliability of the CCD data, we reviewed technical documentation

and interviewed officials from Education’s Institute of Education

Sciences. We found these data sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

To address the second objective, we conducted a literature review to

identify empirical research generally published in peer reviewed journals

or by government agencies over a 10-year period, from January 2009 to

June 2019 (see app. I for criteria used in screening studies). We included

studies that examined exclusionary approaches to discipline, like

suspension (both in and out of school), expulsion, and zero tolerance; as

well as nonexclusionary approaches such as those intended to prevent

behaviors that may lead to discipline.

10

These approaches include social

emotional learning and positive behavior supports, and interventions like

threat assessment. We searched for studies that examined the effects of

discipline approaches on outcomes of school gun violence, school

violence, and school safety.

11

We conducted this performance audit from May 2019 to June 2020 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Research suggests that a young person’s propensity to commit an act of

violence, like a school shooting, is influenced by the interplay of multiple

risk factors and protective factors.

12

These factors, according to the

10

A school may use exclusionary and nonexclusionary approaches in combination. In

addition, for the purposes of our literature review, “nonexclusionary” means approaches to

address student behavior that focus on preventing behaviors that lead to a punitive

disciplinary response. It does not include “time-out” or “detention”, or other forms of

discipline that may be used by teachers or schools.

11

Because existing research was limited, we included literature that examined the

outcome of violent behavior that was not always exclusive to school-based violent

behaviors.

12

C. David-Ferdon, et al, A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of

Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviors (Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury

Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

Background

Research on Youth

Violence

Page 5 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

research, can affect a young person’s development from early childhood

through young adulthood. Risk factors, like a prior history of exposure to

violence or abuse or to high levels of crime or gang activity, can increase

the likelihood of a person becoming a perpetrator of violence. Protective

factors, like stable connections to school, school personnel, and

nonviolent peers, decrease the likelihood of a person becoming a

perpetrator of violence. Risk factors and protective factors play a role on

many levels, such as the interpersonal and community levels. Table 1

summarizes several of the risk and protective factors identified by

research.

Table 1: Examples of Risk and Protective Factors That Influence Youth Violence

Risk Factors

Protective Factors

Individual

•

Impulsiveness

• Substance abuse

• Antisocial or aggressive beliefs and attitudes

• Weak school achievement, peer conflict, or

rejection

• Prior history of exposure to violence or abuse

• Unsupervised access to a firearm

• Depression, anxiety, chronic stress and

trauma

• Prior history of arrest

•

Development of healthy social, problem-solving, and

emotional regulation skills

• School readiness and academic achievement

Relationship

•

Association with peers engaging in violent or

delinquent behavior, including gang activity

• Parental conflict and violence

• Poor parental attachment and lack of

appropriate supervision

• Use of harsh or inconsistent discipline

•

Strong parent-child attachment

• Consistent, developmentally appropriate limits at home

• Stable connections to school and school personnel

• Feelings of connectedness to prosocial, nonviolent

peers

Community

•

Residential instability and crowded housing

• Density of alcohol-related businesses

• Poor economic growth or stability

• Concentrated poverty

• High levels of crime or gang activity

• High levels of unemployment

• High levels of drug use or sales

•

Residences and neighborhoods that are regularly

repaired and maintained, and are designed to increase

visibility and control access (parks, schools,

businesses)

• Policies related to the density of alcohol outlets and

sales

• Stable housing and household financial security

• Economic opportunities (e.g., employment)

• Access to services and social support

Source: GAO analysis of C. David-Ferdon, et al, A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviors (Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury

Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016); and C. David-Ferdon and T.R. Simon, Preventing Youth Violence: Opportunities for Action (Atlanta, GA: National Center for

Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). | GAO-20-455

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

identifying risk factors and protective factors–a public health approach to

Page 6 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

violence prevention—is an important step in understanding where to

focus prevention efforts.

13

Risk factors are cumulative, meaning the more

risk factors youth are exposed to, the greater likelihood they will develop

violent behaviors. It is important to note that not everyone exposed to risk

factors will develop violent behaviors.

14

The CDC’s resources on evidence-based youth violence prevention

efforts include strategies that help ameliorate risk factors and bolster

protective factors, such as strategies that enhance safe environments in

communities, strengthen communication and problem solving skills of

caregivers and parents, and educate students on violence in schools.

15

In

addition, according to a 2007 meta-analysis, school-based prevention

programs involving both psychological and social aspects of behavior,

generally had positive effects for reducing aggressive and disruptive

student behaviors in school settings, such as fighting with and intimidating

others.

16

These risk factors are often evident, for example, in the significant

amount of analyses that have been done on the characteristics of

attackers who have specifically targeted schools, like the shootings that

happened at Columbine, and at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School

in Parkland, Florida and Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, Texas in

2018. These shootings are particularly concerning because the shooter

often indiscriminately targets victims in the school, and because of the

high numbers of killed or wounded victims in a single incident. A 2019

joint report by Education and the Department of Justice (Justice) found

that these kinds of shootings often involved a single, male shooter, mostly

13

CDC. See:

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/publichealthapproach.html

(downloaded March 4, 2020).

14

C. David-Ferdon and T.R. Simon, Preventing Youth Violence: Opportunities for Action

(Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, 2014).

15

C. David-Ferdon and T.R. Simon.

16

S.J. Wilson and M.W. Lipsey, “School-Based Interventions for Aggressive and

Disruptive Behavior. Update of a Meta-analysis,” American Journal of Prevention

Medicine, vol. 33, no. 2S (2007).

Targeted Violence in

Schools

Page 7 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

between the ages of 12 and 18.

17

Further, in 2019, a U.S. Secret Service

study of targeted school violence using firearms or other weapons found

that most of these attackers were motivated by grievances with

classmates and some were motivated by grievances involving school

staff, romantic relationships, or other personal issues.

18

The Secret

Service reported that all of these attackers experienced social stressors

involving their relationships with peers and or romantic partners, nearly all

experienced negative home life factors, most were victims of bullying,

most had a history of disciplinary actions in school, and half had prior

contact with law enforcement. Even so, experts warn against any

attempts to profile shooters in school-targeted shootings because the vast

number of students who have the same or similar characteristics and life

and school experiences, do not commit school shootings. Experts warn

that trying to develop a detailed profile of a shooter who specifically

targets schools risks stigmatizing students who match the profile as well

as ruling out students who are deeply troubled but do not match the

profile.

For nearly two decades, state and federal commissions have studied and

made recommendations to schools and communities in the aftermath of

shootings. Following the shooting at Columbine, a state commission

made recommendations for schools about how to respond to a crisis,

communicate and plan for critical emergencies, and identify potential

shooters.

19

In response to the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary

School, the Sandy Hook commission recommended that the state of

Connecticut create a work group to help develop safe school design

standards that would guide renovations and expansions of existing

schools and the construction of new schools throughout the state.

20

17

L. Musu, et al., Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2018, NCES 2019-047/NCJ

252571 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of

Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department

of Justice, 2019).

18

The U.S. Secret Service analyzed 41 incidents of targeted violence at K-12 schools of

which 25 involved the use of firearms. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Secret

Service, National Threat Assessment Center, Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret

Service Analysis of Targeted School Violence (2019).

19

Report of Governor Bill Owens’ Columbine Review Commission, Colorado Governor’s

Columbine Review Commission, May 2001.

20

Final Report of the Sandy Hook Advisory Commission, Presented to Governor Dannel

P. Malloy, State of Connecticut (Mar. 6, 2015).

Federal and State

Response to School

Shootings

Page 8 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Also following the Sandy Hook shooting, the White House developed a

plan in 2013, called “Now is the Time”.

21

Among other things, the plan

included steps to encourage schools to hire more school resource officers

and school counselors, ensure every school has a comprehensive

emergency plan, and improve mental health services in schools. The plan

also directed federal agencies—Education, Justice, Department of

Homeland Security (DHS), and Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS)—to develop a set of model plans for communities on how

to plan for and recover from emergency situations. In 2013, these

agencies collaborated to produce comprehensive guidance on planning

for school emergencies, including shootings.

22

The guidance advises

schools on how to improve their psychological first aid resources,

information-sharing practices, and school climate, among other things. In

our 2016 report on school safety, we reported that, based on our

nationally generalizable survey of school districts, nearly all districts had

emergency operations plans.

23

Most recently, in 2018, the President formed the Federal Commission on

School Safety after the school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

24

The

Commission made several recommendations to the federal government

and state and local communities aimed at mitigating the effects of

violence and responding to and recovering from such acts. For example,

the Commission recommended that all appropriate state and local

agencies should continue to increase awareness of mental health issues

among students and improve and expand ways for students to seek

needed care. The Commission also recommended that the federal

government develop a clearinghouse to assess, identify, and share best

practices related to school security measures, technologies, and

21

The White House, Now is the Time: The President’s Plan to Protect our Children and

our Communities by Reducing Gun Violence (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 16, 2013).

22

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office

of Safe and Healthy Students, Guide for Developing High-Quality School Emergency

Operations Plans (Washington, D.C.: 2013).

23

GAO, Emergency Management: Improved Federal Coordination Could Better Assist K-

12 Schools Prepare for Emergencies, GAO-16-144 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2016).

24

Final Report of the Federal Commission on School Safety, Presented to the President

of the United States (Dec. 18, 2018).

Page 9 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

innovations.

25

It also made recommendations to specific federal agencies,

including that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration (SAMHSA) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) provide information to states on how they can fund

comprehensive school-based mental health care services. The

Commission also recommended that Education identify resources and

best practices to help schools improve school climate and learning

outcomes, and protect the rights of students with disabilities during the

disciplinary process while maintaining overall student safety. Finally, the

Commission also recommended rescinding the federal “Rethink School

Discipline” guidance, citing the Commission’s concerns with the legal

framework upon which the guidance was based, and its conclusion that

the guidance may have contributed to making schools less safe.

26

There are a range of ways school officials might respond to students

whose behavior in school is deemed unacceptable or inappropriate.

Suspension and expulsion, for example, have been long established as

traditional approaches to discipline used by schools to manage student

behavior. These approaches remove the offending students from the

classroom, and are therefore sometimes known as “exclusionary

discipline.” Schools that enforce “zero tolerance” policies require that

offending students be removed from the classroom regardless of any

mitigating factors or context, such as a student who was engaged in self-

defense. The philosophy of zero tolerance is that removing students who

engage in disruptive behavior in violation of the student code of conduct

will create a better learning environment by deterring other students from

25

In response to this recommendation, DHS, Education, Justice, and HHS created the

SchoolSafety.gov website to share actionable recommendations to help schools prevent,

protect, mitigate, respond to, and recover from emergency situations. See

https://www.schoolsafety.gov/.

26

On January 8, 2014, Education and Justice jointly issued a Dear Colleague Letter and

related guidance documents (collectively referred to in the Commission report as the

“Rethink School Discipline” guidance). The purpose of the Dear Colleague Letter was to

assist public K-12 schools in administering student discipline without discriminating on the

basis of race, color, or national origin. The Dear Colleague Letter stated that in their

enforcement of federal civil rights laws, the Departments would examine whether school

discipline policies resulted in an adverse impact on students of a particular race. It also

included recommendations for school districts, administrators, teachers, and staff that,

among other things, emphasized the use of “positive interventions over student removal.”

Education and Justice withdrew the Rethink School Discipline guidance on December 21,

2018.

Approaches to Addressing

Student Behavior in

School

Page 10 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

engaging in unacceptable or inappropriate behavior.

27

We have

previously reported that exclusionary discipline disproportionately affects

boys, black students, and students with disabilities.

28

A growing body of research has highlighted concerns associated with the

use of exclusionary discipline and, in particular, zero tolerance policies.

For example, as we have previously reported, research has shown that

students who are suspended from school lose important instructional

time, are less likely to graduate on time, and are more likely to repeat a

grade, drop out of school, and become involved in the juvenile justice

system.

29

Some experts, parents, and school staff have called on schools

to consider nonexclusionary approaches to addressing problematic

behavior. Some of these nonexclusionary approaches, such as social

emotional learning, are designed to change students’ mindsets and

behaviors before problem behaviors arise. Other approaches address the

concerning behavior but seek to avoid using exclusionary discipline. For

example, with a threat assessment approach, a multidisciplinary team

assesses the threat of violence and develops a plan to manage such risk.

With restorative practices, schools engage the student in relationship

building and rectifying the consequences of the problematic behavior.

Figure 1 describes several nonexclusionary approaches for addressing

student behavior. According to researchers, nonexclusionary approaches

do not eliminate the need for suspensions and expulsions, but may help

reduce reliance on them. These approaches may use systemic school-

wide practices, curriculum-based classroom lessons, and individual, as-

needed interventions and supports; further, they may be used in

combination with each other or with exclusionary approaches.

27

American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, Are Zero Tolerance

Policies Effective in the Schools? An Evidentiary Review and Recommendations (2008).

28

GAO, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students

with Disabilities, GAO-18-258 (Washington, D.C: Mar. 22, 2018).

29

GAO-18-258.

Page 11 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Figure 1: Nonexclusionary Approaches to Address to Student Behavior

A number of resources provide information on how to implement such

approaches, as well as for information on outcomes associated with the

use of such approaches. For example, Education’s What Works

Clearinghouse of evidence-based practices identifies programs for

managing student behavior. The privately and publicly funded

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

provides information on social and emotional learning implementation,

and research on outcomes.

30

Education also funds a technical assistance

center to provide support to states, school districts, and schools to build

their frameworks of positive behavior supports.

31

In addition, Education

funds the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments,

30

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. See: https://casel.org/

31

Funded by Education’s Office of Special Education Programs and Office of Elementary

and Secondary Education. The Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral

Interventions and Supports can be found at: www.pbis.org.

Page 12 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

which provides information on improving student supports and academic

enrichment, including resources on restorative and trauma-sensitive

practices.

32

Shootings in K-12 schools most commonly resulted from disputes or

grievances, such as between students or staff or between gangs,

according to our analysis of 10 years of data from the Naval Postgraduate

School’s K-12 School Shooting Database. The shooters were students or

former students in about half of the school shootings. More of the

shootings took place outside than inside the school building, though

shootings inside were more deadly. The frequency and type of shooting

varied across a range of characteristics, such as school grade level,

school demographic composition, poverty level, and location.

32

See The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments:

https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/

Characteristics of

Shooting Incidents

and Schools Varied

Page 13 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Various kinds of shootings occurred in K-12 schools, according to our

analysis of 318 incidents over the past 10 school years from the Naval

Postgraduate School’s K-12 School Shooting Database.

33

Shootings

arising from disputes or grievances, such as conflicts between students,

school staff, or gangs, were the most common kinds of shootings, making

up almost a third of school shootings (see fig. 2). Accidents, such as

unintentional discharges from guns, were the next most common kind of

shooting (16 percent). School-targeted shootings, such as the 2018

school shootings in Parkland, Florida and Santa Fe, Texas, made up

about 14 percent of school shootings. Suicides were the next most

common kind (11 percent).

34

33

Our analysis includes incidents in which a gun is fired on school grounds (regardless of

intent), on a school bus, or during a school event (such as a sporting practice or event,

school dance, school play); and during, immediately before, or immediately after school

hours or a school event. See appendix I for more details on our scope and methodology.

For our analysis, we also included four incidents in which a gun was brandished due to the

severity of the incidents. For example, when the shooter initially made threatening

gestures with a firearm, but was stopped prior to a shot being fired; for example, if the

shooter was tackled. Of the 318 incidents in our dataset, four are instances of a gun being

brandished and 314 of a gun being fired.

34

For 9 percent of the incidents in our dataset, information about the shooter or the

motive of the shooting was unknown.

Differences Exist in

Characteristics of School

Shootings, Shooters, and

School Location

Disputes, Such as Fights,

Were the Most Common Kind

of School Shooting

At-a-Glance: kinds of school shootings

Dispute/grievance – conflict or fight,

including gang-related violence on school

grounds

Accidental – accidental discharge of a gun

School-targeted – targeted generally toward

students or staff on school premises, but

generally indiscriminate in terms of specific

victims

Suicide/attempted suicide – suicide or

attempted suicide

Domestic – family members or romantic

partners are targeted

Unknown target/Intent – target or shooter’s

motivation is unknown

Targeted victim – specific victim is targeted,

but the relationship between shooter and

victim is unknown

Related to illegal activity – involves drug

sales, robbery, or other illegal activities (not

including gang-related violence)

Other – does not fit into any of the above

categories

See appendix I for full definitions.

Source: GAO analysis of incidents in the Naval Postgraduate

School’s K-12 School Shooting Database. | GAO-20-455

Page 14 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Figure 2: School Shootings by Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through

2018-19

a

Dispute/grievance-related: Shooting occurred in relation to a dispute or grievance between the victim

and the shooter (that was not domestic in nature), for example: as an escalation of an argument, in

retaliation for perceived bullying, in relation to gang-violence, or anger over a grade/disciplinary action

(including disputes between staff).

b

Other: Disparate incidents that did not clearly fit in one category, such as a shooting by a school

resource officer in response to a threat.

c

Related to illegal activity: Shooting related to an illegal offense, such as drug sales or possession,

robbery, or intentional property damage (not including gang-related violence).

d

School-targeted: Shootings that were targeted generally toward school staff or students on school

premises, but that were generally indiscriminate in terms of specific victims. These include incidents

of a hostage standoff, indiscriminate shootings targeting the school staff and personnel, and active

shooter incidents as categorized by the FBI. Such shootings may also include incidents where a

specific victim was targeted because of his or her relationship to the school (e.g. student, principal,

staff, SRO, etc.).

Page 15 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

While shootings related to disputes/grievances occurred most often,

school-targeted shootings resulted in far more individuals killed or

wounded per incident than any other type of shooting (see table 2).

Specifically, of the nearly 500 people killed or wounded in school

shootings over the past 10 years, over half of those killed and more than

one-third of those wounded were victims in school-targeted shootings.

Additionally, school-targeted shootings resulted in almost three times as

many individuals killed or wounded per incident than the average number

of individuals killed or wounded per incident overall.

Table 2: School Shootings and Fatalities/Casualties by Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

Total

incidents

Total killed

(includes

shooter)

Average

killed per

incident

Total

wounded

Average

wounded per

incident

Total

wounded

or killed

Average

wounded or

killed per

incident

All

318

166

0.52

330

1.04

496

1.56

School-targeted

46

89

1.93

122

2.65

211

4.59

Suicide/attempted

suicide

34

29

0.85

5

0.15

34

1.00

Domestic

22

16

0.73

13

0.59

29

1.32

Other

10

5

0.50

7

0.70

12

1.20

Related to illegal

activity

12

4

0.33

8

0.67

12

1.00

Targeted victim

15

4

0.27

16

1.07

20

1.33

Dispute/grievance-

related

99

17

0.17

101

1.02

118

1.19

Unknown target/intent

29

1

0.03

15

0.52

16

0.55

Accidental

51

1

0.02

43

0.84

44

0.86

Source: GAO analysis of the Naval Postgraduate School’s K-12 School Shooting Database for school years 2009-10 through 2018-19. | GAO-20-455

The shooter’s relationship to the school was unknown in almost 20

percent of all school shootings that have occurred over the past 10 years

(such as when an unidentified shooter walked onto school grounds and

Three examples of dispute/grievance-related

shootings:

A gang member waited outside the gates of a

high school homecoming football game and

opened fire when he saw rival gang members

leaving the field.

A teacher shot at the principal and assistant

principal when they told him that his contract

would not be renewed for the following year.

Two students were fighting in the hallway

when one pulled out a gun and shot the other.

Source: GAO analysis of incidents in the Naval Postgraduate

School’s K-12 School Shooting Database. | GAO-20-455

Students Committed Half of

School Shootings, While Those

Unknown, No Relationship to

the School, And Others

Committed the Other Half

Page 16 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

fired at a victim).

35

The shooters were students or former students in

about half of the school shootings during the same time period. The other

roughly 30 percent of shootings were committed by parents and relatives

(such as when a husband shot his wife as she was picking up her

children from school), teachers and staff, and people who had no

relationship with the school (such as a shooting during a basketball game

involving rival gang members who had no relationship with the school)

(see fig. 3).

Figure 3: School Shootings by Shooter’s Relationship to School, School Years

2009-10 through 2018-19

Note: Percentages do not add to 100, due to rounding.

a

“Unknown,” as recorded in the K-12 School Shooting Database, includes incidents in which the

shooter’s relationship to the school was not identifiable in the original source material used by the K-

35

“Unknown,” as recorded in the K-12 School Shooting Database, includes incidents in

which the shooter’s relationship to the school was not identifiable in the original source

material used by the K-12 School Shooting Database researchers. This may include

incidents in which the shooter’s name was identified but the shooter’s relationship to the

school could not be determined.

Page 17 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

12 School Shooting Database researchers. This may include incidents in which the shooter’s name

was identified but the shooter’s relationship to the school could not be determined.

b

We combined four categories from the K-12 School Shooting Database into an “Other” category:

intimate relationship with victim, multiple shooters, students from a rival school, and non-students

using athletic facilities/attending game.

Characteristics of shooters differed by the kind of shooting. For example,

students or former students were the shooters in the majority of school-

targeted shootings (over 80 percent). In contrast, parents or relatives of

someone in the school were the shooters in almost a third of the

shootings that involved some sort of domestic dispute (table 3).

Table 3: Shooter Relationship to School by Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

All

Student/

former

student

Unknown

a

No relation

Parent/

relative

Police officer/

school resource

officer

Teacher/

staff

Other

b

All

318

156

59

38

17

14

14

20

Accidental

51

33

1

2

5

5

5

0

Dispute/grievance-

related

99

37

22

19

4

0

4

13

Domestic

22

5

0

4

7

0

0

6

Related to illegal activity

12

1

5

2

0

3

1

0

School-targeted

46

37

2

5

0

0

1

1

Suicide/attempted

suicide

34

30

1

0

0

1

2

0

Targeted victim

15

4

9

2

0

0

0

0

Unknown target/intent

29

7

18

2

1

0

1

0

Other

10

2

1

2

0

5

0

0

Source: GAO analysis of the Naval Postgraduate School’s K-12 School Shooting Database for school years 2009-10 through 2018-19. | GAO-20-455

a

“Unknown,” as recorded in the K-12 School Shooting Database, includes incidents in which the

shooter’s relationship to the school was not identifiable in the original source material used by the K-

12 School Shooting Database researchers. This may include incidents in which the shooter’s name

was identified but the shooter’s relationship to the school could not be determined.

b

We combined four categories from the K-12 School Shooting Database into an “Other” category:

intimate relationship with victim, multiple shooters, students from a rival school, and non-students

using athletic facilities/attending game.

About 60 percent of school shootings occurred outside of the school

building, like in a parking lot or on a school bus; in some cases, bullets hit

school property when the shooter was not on school property (such as

when a stray bullet from a neighborhood shooting broke a window in a

school building). The remaining roughly 40 percent occurred inside the

school building, such as in a classroom, hallway, or bathroom (see fig. 4).

Over Half of School Shootings

Occurred Outside the School

Building, but Shootings Inside

the Building Were More Deadly

Page 18 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Figure 4: School Shootings by Shooting Location and Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

Notes: There is one incident where the location of the shooting was unknown. This incident was

excluded from our analysis of location. Therefore, the total number of incidents in this analysis totals

317.

We combined three categories from the K-12 School Shooting Database into an “Outside the school

building” category: outside on school property, off school property, and on school bus.

When shootings occurred outside the school building, about 70 percent of

the shooters were people other than students or former students, like

parents of students, people who had no relation to the school, or people

whose relationship to the school was unknown (see table 4). Further,

certain kinds of shootings occurred more often outside the school

building, such as those related to disputes/grievances, domestic disputes,

illegal activities, and those in which the target or intent was unknown. In

addition, of the shootings that occurred during school sporting events, like

Page 19 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

basketball games or football games, nearly all—93 percent—occurred

outside the school building.

36

Table 4: Number of Shootings Inside and Outside the School Building by Shooter’s Relationship to School, School Years

2009-10 through 2018-19

Location

All

Student/

former

student

Unknown

a

No relation

Parent/

relative

Police

officer/

school

resource

officer

Teacher/

staff

Other

b

All

318

156

59

38

17

14

14

20

Inside the school building

125

98

1

4

2

8

11

1

Outside the school building

c

192

58

58

34

15

5

3

19

Unknown

1

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

Source: GAO analysis of the Naval Postgraduate School’s K-12 School Shooting Database for school years 2009-10 through 2018-19. | GAO-20-455

a

“Unknown,” as recorded in the K-12 School Shooting Database, includes incidents in which the

shooter’s relationship to the school was not identifiable in the original source material used by the K-

12 School Shooting Database researchers. This may include incidents in which the shooter’s name

was identified but the shooter’s relationship to the school could not be determined.

b

We combined four categories from the K-12 School Shooting Database into an “Other” category:

intimate relationship with victim, multiple shooters, students from a rival school, and non-students

using athletic facilities/attending game.

c

We combined three categories from the K-12 School Shooting Database into an “Outside the school

building” category: outside on school property, off school property, and on school bus.

In contrast, when shootings occurred inside the school building, the

majority of the shooters—over three-quarters—were students or former

students (see table 4). Accidental and school-targeted shootings occurred

more often inside the school building than outside the school building,

and together these two kinds of shootings made up the majority of

shootings that occurred inside school buildings (see fig. 4). Shootings that

occurred inside the school building were on average three times deadlier

per incident than shootings that occurred outside the school building (see

app.II).

36

Thirteen percent of all school shootings occurred in relation to a sporting event.

Two examples of accidental shootings:

When an elementary school student sat down

for lunch in the cafeteria, a handgun fell out of

the student’s pocket and discharged, injuring

three other students.

A gun discharged in a teacher’s pocket inside

a classroom, injuring one student.

Source: GAO analysis of incidents in the Naval Postgraduate

School’s K-12 School Shooting Database. | GAO-20-455

Page 20 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Our analysis also showed that school shootings occurred across schools

with a range of different characteristics, but certain kinds of shootings

were more prevalent at certain types of schools.

37

High schools had the

most school shootings (about two-thirds of all shootings) over the past 10

years. In high schools, shootings related to disputes/grievances, school-

targeted shootings, and suicides were the most prevalent. In middle

schools, accidental shootings and shootings related to

disputes/grievances were the most prevalent. In elementary schools,

accidental shootings were the most prevalent (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: School Shootings by School Level and Kind of Shooting, School Years

2009-10 through 2018-19

37

We matched 297 of the 318 incidents to corresponding data on school characteristics

from the U.S. Department of Education’s Common Core of Data. The remaining 21

schools could not be matched due to either missing information or because they were

private schools, which are not included in the CCD.

Certain Kinds of Shootings

Were More Prevalent at

Certain Types of Schools

High Schools Had More School

Shootings

Overall, and

Elementary Schools Had More

Accidental Shootings

Page 21 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Notes: Percentages may not add to 100, due to rounding. At the time of this analysis, the Common

Core of Data (CCD) variables were available only through the 2017-2018 school year, and were not

available for the 2018-2019 school year. We matched school shootings from the 2018-2019 school

year to CCD variables for the 2017-2018 school year for this analysis.

Of the 318 school shootings in our analysis, 21 could not be matched to data from the CCD due to

missing information or because they were private schools, which are not included in the CCD. An

additional 5 incidents were missing school level data in the CCD and were therefore excluded from

this analysis. Therefore, the number of incidents in this analysis totals 292.

Further, although shootings occurred at all different times of day and

throughout the school year, nearly 40 percent of shootings occurred in the

morning and most frequently occurred in either January or September.

Also, certain kinds of shootings occurred more often during different times

of the day; for example, school-targeted shootings and suicides occurred

more often in the morning, whereas shootings related to

disputes/grievances occurred more often in the afternoon and evening

(see app. II).

As figure 6 shows, the number of shootings generally increased relative

to school poverty level.

38

,

39

Poorer schools—those in which 50 percent or

more of the students were eligible for free or reduced price lunch—had

the most, or nearly two-thirds of all shootings. The wealthiest schools—

those in which 25 percent or fewer of the students were eligible for free or

reduced priced lunch—had the fewest with just over one-tenth of all

shootings. Additionally, certain kinds of shootings increased with poverty,

like shootings related to disputes/grievances and shootings in which the

target or intent was unknown (see fig. 6). In contrast, certain kinds of

shootings were more prevalent in wealthier schools, like school-targeted

shootings and suicides.

38

For our poverty level analyses, we grouped schools into four categories based on the

percent of students enrolled who were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL),

according to the CCD data. The categories we used in our analysis are as follows: schools

with 0 to 24.9 percent of students eligible for FRPL (the wealthiest schools), schools with

25 to 49.9 percent of students eligible, schools with 50 to 74.9 percent of students eligible,

and schools with 75 to 100 percent of students eligible (the poorest schools).

39

The number of school shootings generally increased relative to poverty level, defined by

the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch (FRPL), but declined

slightly in the highest poverty category. Specifically, there were 94 shootings at schools

with between 50 percent and less than 75 percent students eligible for FRPL, and 91

shootings at schools with 75 percent or more students eligible for FRPL.

Poorer Schools Had More

School

Shootings Overall, but

Wealthier Schools Had More

School

-Targeted Shootings

and Suicides

Page 22 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

Figure 6: School Shootings by Free or Reduced Price Lunch Eligibility and Kind of

Shooting, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

Notes: Percentages may not add to 100, due to rounding. For our analysis, we grouped schools into

four categories based on the percent of students enrolled who were eligible for free or reduced-price

lunch (FRPL). The categories are as follows: schools with 0 to 24.9 percent of students eligible for

FRPL, schools with 25 to 49.9 percent of students eligible, schools with 50 to 74.9 percent of students

eligible, and schools with 75 to 100 percent of students eligible.

At the time of this analysis, the Common Core of Data (CCD) variables were available only through

the 2017-2018 school year, and were not available for the 2018-2019 school year. We matched

school shootings from the 2018-2019 school year to CCD variables for the 2017-2018 school year for

this analysis.

Of the 318 school shootings in our analysis, 21 could not be matched to data from the CCD due to

missing information or because they were private schools, which are not included in the CCD. An

additional 19 incidents were missing FRPL data in the CCD and were therefore excluded from this

analysis. Therefore, the number of incidents in this analysis totals 278.

Schools with the highest percentages of minority students had more

shootings overall and proportionally more shootings related to

disputes/grievances and shootings in which the target or intent was

unknown. On the other hand, schools with the lowest percentages of

minority students had fewer shootings overall, but proportionally more

school-targeted shootings (see fig. 7). Further, as shown in table 3, for

shootings related to disputes/grievances, which were most prevalent at

Page 23 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

high minority and poorer schools, the shooter was more often someone

other than a student or the shooter was unknown. In contrast, for school-

targeted shootings and suicides, which were most prevalent at low-

minority and wealthier schools, the shooter was more often a student or

former student.

Figure 7: School Shootings by Minority Enrollment and Kind of Shooting, School

Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

Notes: Percentages may not add to 100, due to rounding. For our analysis, we define minority

enrollment as the enrollment of all students who are not white.

At the time of this analysis, the Common Core of Data (CCD) variables were available only through

the 2017-2018 school year, and were not available for the 2018-2019 school year. We matched

school shootings from the 2018-2019 school year to CCD variables for the 2017-2018 school year for

this analysis.

Of the 318 school shootings in our analysis, 21 could not be matched to data from the CCD due to

missing information or because they were private schools, which are not included in the CCD. An

additional 7 incidents were missing minority enrollment data in the CCD and were therefore excluded

from this analysis. Therefore, the number of incidents in this analysis totals 290.

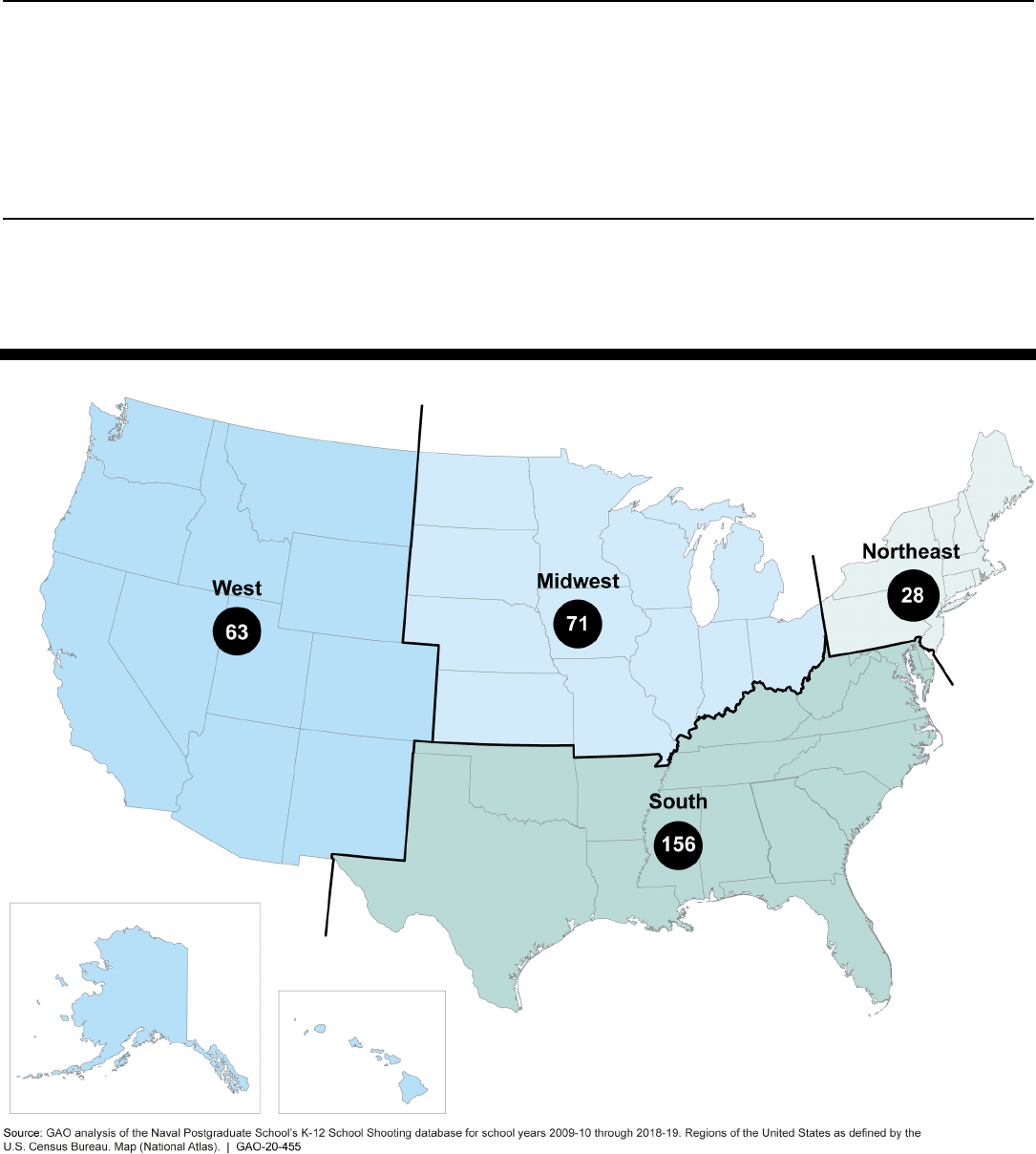

School shootings occurred all across the country in all but two states

(West Virginia and Wyoming). About half of school shootings in the past

10 years occurred in the South, according to our analysis, with the

School Shootings Occurred

Nationwide, but About Half

Were in the South

Page 24 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

greatest number of shootings in Florida (24), Texas (24), and Georgia

(23) (see fig. 8). See appendix II for data on shootings over time, which

shows an uptick in shootings in school years 2017-18 and 2018-19, as

compared to earlier in the 10-year period.

Figure 8: Map of K-12 School Shootings in the United States, School Years 2009-10 through 2018-19

School shootings also occurred across locations with varying population

densities, but almost half of all shootings occurred in urban schools (47

Page 25 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

percent).

40

However, while urban schools had more school shootings

overall, suburban and rural schools had the most school-targeted

shootings – the deadliest type of shooting. Specifically, 6 percent of

shootings in urban schools were school-targeted, while 22 percent of

shootings in suburban schools, and 29 percent of shootings in rural

schools were school-targeted (see fig. 9).

Figure 9: School Shootings by Locale and Kind of Shooting, School Years 2009-10

through 2018-19

Notes: Percentages may not add to 100, due to rounding. At the time of this analysis, the Common

Core of Data (CCD) variables were available only through the 2017-2018 school year, and were not

available for the 2018-2019 school year. We matched school shootings from the 2018-2019 school

year to CCD variables for the 2017-2018 school year for this analysis.

Of the 318 school shootings in our analysis, 21 could not be matched to data from the CCD due to

missing information or because they were private schools, which are not included in the CCD. An

additional 5 incidents were missing locale data in the CCD and were therefore excluded from this

analysis. Therefore, the number of incidents in this analysis totals 292.

40

We used information from the U.S. Department of Education’s Common Core of Data to

determine a school’s locale. Urban schools have a locale designation of “city,” suburban

schools have a locale designation of “suburb,” town schools have a locale designation of

“town,” and rural schools have a locale designation of “rural.”

Page 26 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

We found no empirical research in the last 10 years (2009-2019) that

directly examines the link between approaches to school discipline—

whether exclusionary (like suspensions and expulsions) or

nonexclusionary approaches—and school shootings specifically.

41

We

also reviewed 27 studies meeting our selection criteria that examined the

link between discipline approaches and broader concepts of violent

behavior and perceptions of school safety; however, none of these

studies examined shootings specifically in school (see appendix I for

detailed information on our overarching inclusion criteria we used to

select the studies). One of the 27 studies examined shootings in which

students of selected Chicago public schools were the victims, but were

not necessarily on school grounds. The study examined a

nonexclusionary approach to school discipline that used social media

monitoring to identify and intervene with high school students who were

engaging in potentially dangerous behaviors and offered them wrap-

around services such as school-based social emotional support.

42

The

study found that students who initially attended high schools that used the

41

Our literature review was designed to capture studies using empirical research methods

to examine the effects of approaches to school discipline—including exclusionary and

nonexclusionary—on school gun violence, school violence, and school safety. See

appendix I for details of our scoping parameters used for our literature review.

42

University of Chicago Crime Lab. Connect & Redirect to Respect: Final Report (January

2019). The study defined student shooting victimization as instances in which Chicago

Public School students were the physical victims of gunfire, both fatal and non-fatal. This

study was funded through an award by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice

Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, and was made publically available through the

Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. It was not

published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Empirical Research

Does Not Directly

Examine Link

between Discipline

and School Shootings

No Empirical Research

Directly Examines the Link

between Discipline and

School Shootings

Page 27 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

approach experienced fewer shooting incidents compared to students

who attended schools that did not use the approach.

43

There are characteristics of school shootings themselves that likely

contribute to the lack of research that specifically examines the link

between approaches to school discipline and school shootings, according

to literature we examined and study authors we interviewed. It is difficult

to isolate the effect of any one variable in a school shooting, such as the

role of school discipline, because multiple and complex factors affect an

individual’s propensity toward violence, shootings have many types of

shooters and many possible causes, and researchers have so few

comparable cases to study. More specifically:

• Violence has multiple causes: Research suggests there are many

complex factors that influence youth violence, like a prior history of

exposure to violence or abuse, antisocial or aggressive beliefs, peer

conflict or rejection, or parental conflict and violence.

• School shooters and school shootings vary considerably: We

found that, in the past 10 years, the shooters were students or former

students in about half of the incidents, and parents, teachers, or

others were the shooters in the other half. Further, the reason for the

shooting or kind of shooting varied from suicides and disputes to

school-targeted shootings and the factors that precipitate these

different kinds of shootings likely vary considerably.

• School shootings are rare events: Our analysis identified 318

school shootings that occurred over a 10-year period. In school year

2016-17, there were approximately 98,000 public K-12 schools in the

U.S. Such rarity, coupled with the above factors, makes it difficult to

design a study examining a direct causal relationship between a

discipline approach and its effects on school shootings.

With respect to the 27 studies we reviewed, drawing bottom-line

conclusions about the overall effectiveness of any given approach to

school discipline is difficult because these studies varied in terms of their

research methodologies, outcomes measured, populations studied, and

research objectives. However, these studies can help illustrate some of

the types of approaches currently being used. Among the approaches

43

The results from this study were marginally significant with p-values of 0.13 and 0.14 in

the second and third year respectively. The study used a partially randomized control

design.

Page 28 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

addressed in the studies we reviewed were social emotional learning,

threat assessment, and exclusionary discipline.

Some of the research on social emotional learning—which includes

teaching students how to manage emotions and solve problems—found

that using this approach reduces violent behaviors in students,

particularly elementary school students. For example, a study employing

random assignment of 20 elementary schools in Hawaii, found

significantly fewer reports of violent behavior for students in schools using

a social emotional learning program compared to students in schools that

did not.

44

However, other studies—particularly those that included middle

school aged youth and studies where measures of aggression included

both physical violence and non-violent behaviors—were less likely to

demonstrate positive effects. For example, a quasi-experimental study

found no significant effects on student-reported aggressive behaviors

among 6th-8th grade middle schools students in two rural counties in

North Carolina.

45

Two studies we reviewed involved threat assessment, in which a

multidisciplinary team assesses a threat of violence and develops a plan

to manage such risk. Both studies found evidence that this approach

resulted in fewer instances of violent behavior among students when

compared to schools using another form of threat assessment or no

threat assessment. One was a quasi-experimental retrospective study

across 280 urban, suburban, and rural high schools that found lower

levels of violent behavior (ranging from theft of personal property to being

physically attacked) among ninth graders in schools using the Virginia

Student Threat Assessment Guidelines compared to students in schools

using no form of threat assessment.

46

The other was a quasi-

experimental retrospective study of over 300 Virginia middle schools that

found lower levels of student violent behavior in the form of verbal or

44

Michael W. Beets, et al., “Use of Social and Character Development Program to

Prevent Substance Use, Violent Behaviors, and Sexual Activity Among Elementary-

School Students in Hawaii,” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 99, no. 8 (2009).

45

Shenyang Guo, et al., “A Longitudinal Evaluation of the Positive Action Program in a

Low-Income, Racially Diverse, Rural County: Effects on Self-Esteem, School Hassles,

Aggression, and Internalizing Symptoms,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44 (2015):

pp. 2337–2358.

46

Dewey Cornell, et al., “A Retrospective Study of School Safety Conditions in High

Schools Using the Virginia Threat Assessment Guidelines Versus Alternative

Approaches,” School Psychology Quarterly, vol. 24, no.2 (2009): pp.119-129.

Page 29 GAO-20-455 K-12 School Shootings

physical aggression, and higher feelings of safety among teachers at

middle schools using the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines

compared to schools with no threat assessment or another model of

threat assessment.

47

We also reviewed studies that examined how exclusionary approaches to

discipline—or changes in policies affecting use of these approaches—

may influence school violence and perceptions of safety more broadly.

These studies differed in approach and findings. For example, one

examined whether higher suspension rates and other factors are

associated with students’ perception of safety at school. In this study of

elementary and middle school students in a large Maryland school

district, schools with higher suspension rates were associated with

decreased perceptions of safety as reported by middle school students;

however, suspension rates were not significantly associated with

perceptions of safety for elementary schools students.

48

Another study

used a quasi-experimental method to examine whether a school district’s

limitations on out-of-school suspension reduced serious misconduct,

including acts of violence and weapon possession as well as non-violent

acts, among students. It compared these infractions in the Philadelphia

school district after it ended its zero tolerance policy, to nearly all other

school districts in Pennsylvania and found that serious incidents of

student misconduct, including violence, increased after the zero tolerance

policy was rolled back.

49

For more details on the studies we reviewed, see appendix III.

47