University of South Carolina University of South Carolina

Scholar Commons Scholar Commons

Theses and Dissertations

Spring 2023

“Everything Old Is New Again”: The Rise of Interpolation in Popular “Everything Old Is New Again”: The Rise of Interpolation in Popular

Music Music

Grayson M. Saylor

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd

Part of the Music Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Saylor, G. M.(2023).

“Everything Old Is New Again”: The Rise of Interpolation in Popular Music.

(Doctoral

dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/7300

This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in

Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

“EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN”: THE RISE OF INTERPOLATION IN POPULAR

MUSIC

by

Grayson M. Saylor

Bachelor of Music

Kennesaw State University, 2020

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Music in

Music History

School of Music

University of South Carolina

2023

Accepted by:

Kunio Hara, Co-Director of Thesis

Bruno Alcalde, Co-Director of Thesis

Birgitta Johnson, Reader

Julie Hubbert, Reader

Cheryl L. Addy, Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School

ii

© Copyright by Grayson Saylor, 2023

All Rights Reserved.

iii

ABSTRACT

With hip-hop becoming the number one genre in the United States, many artists

working outside of the hip-hop genre are trying to emulate the success of hip-hop artists

by incorporating compositional techniques of hip-hop into their own music. One of the

most common hip-hop techniques adopted by artists working in other genres is sampling.

However, with copyright rules and regulations becoming more strictly enforced, artists

are finding creative ways to emulate sampling styles, while trying to avoid copyright

concerns, including interpolation. Through the technique of interpolation, by

reperforming aspects of the original song, artists are able to quote and reference

previously recorded songs while avoiding some of the legal ramifications. This avoids

many issues of copyright while providing the original songwriter with credit and a

portion of the royalties. This trend has been increasing significantly since 2017 and many

publishing companies are taking an interest in this trend. Primary Wave is leading the

trend of buying artists’ catalogs and encouraging current artists to interpolate music from

their own song library, bringing in revenue to the publishing company in addition to the

artists. By focusing on songs from 2017 to 2023 of Billboard’s Year-End Hot 100, this

thesis will exam interpolation trends through the lenses of social media, copyright issues,

and economic gain for publishing companies.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract .............................................................................................................................. iii

List of Figures ......................................................................................................................v

Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................1

Description of the Problem ........................................................................................4

Statement of Purpose .................................................................................................5

Review of Related Literature ....................................................................................6

Methodology ............................................................................................................16

Limitations/delimitations .........................................................................................18

Conclusion ................................................................................................................18

Chapter 2: Case Studies ....................................................................................................20

“7 Rings” by Ariana Grande ...................................................................................25

“Kings and Queens” by Ava Max ...........................................................................32

“Good 4 U” by Olivia Rodrigo ................................................................................38

Chapter 3: Economic and Social Impacts ..........................................................................45

Publishing Companies ...........................................................................................45

The Impact of Social Media ...................................................................................48

Conclusion .............................................................................................................55

Bibliography ......................................................................................................................56

Appendix: Discography .....................................................................................................64

v

LIST OF FIGURES

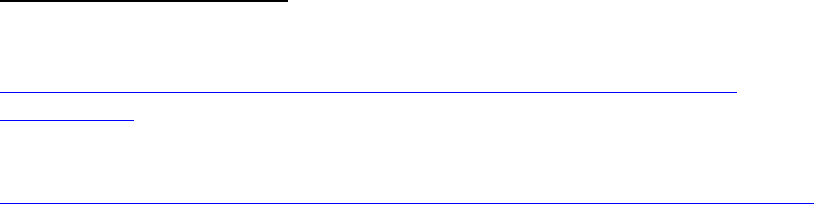

Figure 2.1 Diagram for the first half of “Kings and Queens,” “You Give Love a Bad

Name,” and “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man)” ...................................34

Figure 2.2 Diagram for the second half of “Kings and Queens,” “You Give Love a Bad

Name,” and “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man)” ...................................35

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Have you ever heard a song and thought to yourself, “I’ve heard this song

before,” but then realized it was just released and there was no possible way you had

heard it previously? Chances are your brain is not tricking you, but rather you have heard

this song before, or at least snippets of it, from a previously released song. This

phenomenon is called “interpolation.” Interpolation is the musical technique of taking a

previously recorded song and re-performing a portion of that track, whether it be the sung

melody, lyrics, part of an instrumental line, or particular production techniques, and

including it in the creation of a new song. Since 2017, many popular artists, such as

Ariana Grande, Taylor Swift, and Doja Cat, are increasingly incorporating interpolations

into their newly released songs. There are many reasons why this may be the case, but

two in particular are the rise in popularity of hip-hop and the increasing concerns for

copyright infringement. Sampling is a technique that is closely associated with hip-hop,

but including a sample into a song requires approval from the original artist, and some

sort of upfront payment from the artist wanting to use the sampling. This can bring about

issues when an artist does not give approval for their sample to be used, or if an artist

2

does not pay the fee needed to include the sample.

1

Many artists are choosing to avoid

this process entirely by including an interpolation instead of a sample.

Ethan Millman from Rolling Stone describes interpolation as a “cousin to

sampling” and defines its limits by borrowing “from a song’s written composition –

whether that’s lyrics, a melody, a riff, or a beat.”

2

While this definition can give a good

idea of what interpolation may be to readers who are more familiar with sampling, it is

historically inaccurate. Interpolations have existed far before sampling was established;

therefore, it is better to describe interpolation as a “parent” to sampling.

3

One of the

clearest examples of interpolation in recent popular music is Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings”

where the melody is interpolated from Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s “My

Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music, but with new lyrics over it. Other

interpolations, however, are harder to identify from first listen. The chorus of Doja Cat’s

“Kiss me More” may sound familiar because the melody is actually interpolated from

parts of the chorus of Oliva Newton-John’s “Physical.” Listeners may not pick this up the

first time they hear it, or the second time, or even the tenth time, but when paired side-by-

side, the influence is unmistakable. This creates a sort of subliminal nostalgia that

companies are capitalizing on to help make new songs become instant hits.

1

Amanda Sewell, “A Typology of Sampling in Hip-Hop” (Ph.D. diss., Indiana

University, Indiana, 2013), 196.

https://www.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/1427344595/abstract/CCE46814E6F6478

2PQ/1

2

Ethan Millman, “‘No Shelf Life Now’: The Big Business of Interpolating Old

Songs for New Hits,” Rolling Stone, September 7, 2021,

https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/features/olivia-rodrigo-doja-cat-interpolation-music-

1220580/.

3

J. Peter Burkholder, “Musical Borrowing or Curious Coincidence?: Testing the

Evidence,” The Journal of Musicology 35, no. 2 (2018): 223–66.

3

While the trend has greatly increased since 2017, this technique is nothing new, as

interpolation is older than sampling, and even older than contemporary pop music. The

tradition of interpolation falls into the larger category of musical borrowings. Musical

borrowings can be traced back to the early creation of music, with one of the earliest

instances of borrowing through the practice of troping in the 9

th

to 13

th

centuries.

4

Various other forms of borrowing evolved throughout the Renaissance and Baroque

periods, and instances of borrowing can be found in classical music such as Alban Berg

quoting Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde for his Lyric Suite, or Johannes Brahms

using Johan Sebastian Bach’s chaconne for solo violin “as one model for the chaconne

finale of his Symphony No. 4 in E Minor.”

5

Interpolation has been used by pre-2000s’ popular artists, with one of the clearest

early examples of interpolation in hip-hop being Afrika Bambaataa and Soul Sonic

Force’s “Planet Rock.” Inspired by Kraftwerk, “Planet Rock” interpolates elements of the

synthesizer from “Trans Euro Express.” While the melody and timbre are changed, the

interpolation is still clear, causing some people at the time of its release to believe that

this was sampled. Even before its use in popular music, interpolation dates as far back as

classical composers quoting other composers. What is new, however, is that critics and

fans are noticing the phenomenon on a much larger scale than before and increasing

conversations around the topic. Additionally, publishing companies are using information

4

J. Peter Burkholder, “Borrowing,” Grove Music Online, January 20, 2001.

https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.52918.

5

Burkholder, “Musical Borrowing or Curious Coincidence?” 236-237.

4

from fans to create and market new music featuring interpolation, with the intention of

predicting the creation of an immediate hit song.

Description of the Problem

Instances of interpolation in American popular music are increasing significantly,

and journalistic writings as well as fan interactions are noticing the phenomenon. Despite

the ubiquity of interpolation in the current popular music scene, academic research on the

topic is still under development. This lack of robust academic discourse on interpolation

specifically, and on what is influencing the increase of the use of interpolation in pop

music and public conversations about it, provides an opportunity for further research on

the subject. Much of the recent exploration of this topic is from music magazines such as

Spin and Billboard, in addition to social media websites, while much of older exploration

that discusses the topic either focuses more on concrete musical borrowings, such as

sampling, or talks more broadly about musical borrowings. Because of this, the language

when discussing interpolation is somewhat limited, therefore difficult to discuss without

musical examples.

Many authors have tried to define interpolation. Charlie Harding from Vulture

describes it as “a kind of reboot, incorporating musical ideas from another song by

rerecording and/or reimagining them.”

6

Gil Kaufman from Billboard defines it as

“making a new piece of music in which you don’t sample the original, but either sing or

6

Charlie Harding, “Invasion of the Vibe-Snatchers: Pop Music Is Regurgitating

Itself Faster Than Ever,” Vulture, September 15, 2022,

https://www.vulture.com/article/pop-music-regurgitations-switched-on-pop.html.

5

play a piece of it yourself with an acknowledgement of such.”

7

Matthew Newton from

Spin defines interpolation as “the practice of having a musician rerecord a sample to help

reduce costs.”

8

Billboard staff when discussing their top interpolations chooses to

describe interpolations as “sections of new songs that borrow melodic and sometimes

lyrical elements from older songs, without sampling their original recordings.”

9

While all

of these definitions do explain aspects of interpolation, there is not one standard

definition, thus showing a need to establish one. Additionally, the increase of

interpolation in recent years shows a trend that potentially may become a new norm in

the music industry, thus creating major importance on studying and understanding this

creative process.

10

Statement of Purpose

There are many reasons artists may be increasing their use of interpolation and

these reasons will be explained and explored throughout this thesis. Additionally, I will

analyze sampling and interpolation in contemporary popular music to show how trends

are increasing and determine terminology to describe different forms of interpolation. In

my research, I define interpolation as a type of musical borrowing, where a portion of one

or more elements of a previously composed song are extracted and reperformed, with or

without subtle alterations, by another artist in the creation of a new song. These elements

7

Gil Kaufman, “Experts Explain How to Decipher — And Then Prove —

Whether a Song Borrows By Accident or on Purpose,” Billboard, October 28, 2021,

https://www.billboard.com/pro/interpolations-experts-prove-court/.

8

Matthew Newton, “Is Sampling Dying?” SPIN, November 21, 2008,

https://www.spin.com/2008/11/sampling-dying/.

9

“The 50 Best Song Interpolations of the 21st Century: Staff Picks,” Billboard,

October 28, 2021, https://www.billboard.com/media/lists/best-interpolations-9651682/.

10

Charlie Harding, “Invasion of the Vibe-Snatchers.”

6

may be melody, texture, lyrics, production characteristics, or other aspects of the original

song. Additionally, for contemporary interpolations, the original songwriter receives

credit on the new creation. From the result of my research, I have identified three main

subcategories of interpolation: melodic, textual, and production interpolations. These

categories can be applied to examples found in pop music. The goals of this thesis are to

identify how fans and other artists are receiving these interpolations, and identify the role

of publishing companies within this phenomenon.

Review of Related Literature

The literature reviewed in the following section includes dissertations, magazine

articles, academic journal articles, edited volumes, and monographs all relating to

sampling and interpolation in hip-hop and popular music. This literature review is

divided into three main categories: interpolation in popular music, sampling and

terminology, and copyright and social media. Much of the reviewed literature comes

from sources that directly interact with the music industry such as trade publications, as

well as various forms of social media, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube,

and TikTok, where fans can voice their opinions and artists are able to respond.

Interpolation in Popular Music

Much of the current discussion on interpolation exists in trade publications and

fan-driven online communities including popular social media outlets and music centered

online communities. Each of these sources defines interpolation since it is a term that

may not be familiar to many people outside of the industry. In Rolling Stone’s article

“Why You’re Hearing More Borrowed Lyrics and Melodies on Pop Radio,” Elias Leight

7

describes interpolation as a “sort of borrowing, in which an artist employs a snippet of an

already-recorded song in the creation of something new.”

11

The article expresses that this

trend of interpolation is present in popular music, going beyond just the “unabashedly

nostalgic songs” and being included in other pop hits.

12

This article, published in 2018,

describes 2017 as having “major pop records based around interpolations” with previous

years not even coming close.

13

Each of the sources on interpolation are incredibly recent,

with this Rolling Stone article being the oldest. However, almost all of the articles seem

to describe 2017 as being the starting year of the mass trend of interpolating music.

According to the article “Rap Dominated Pop in 2017, and It’s Not Going Anywhere

Anytime Soon” from Vulture, 2017 was the year that hip-hop took over as the number

one music genre in the United States.

14

That same year pop artists, such as Ed Sheeran,

Taylor Swift, and The Chainsmokers, began to realize the popularity of hip-hop and

started emulating techniques used by hip-hop artists, such as sampling and interpolation,

to capitalize on their success.

15

Before 2017, interpolations could be found within

Billboard’s Year-End Hot 100, however most of the artists utilizing this technique were

known for hip-hop or rap genres. During 2017, not only was there an increase of hip-hop

artists with songs including interpolations in the Year-End Hot 100, but also artists

11

Elias Leight, “Why You’re Hearing More Borrowed Lyrics and Melodies on

Pop Radio,” Rolling Stone, July 5, 2018, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-

news/why-youre-hearing-more-borrowing-on-pop-radio-627837/.

12

Leight, “Why You’re Hearing More Borrowed Lyrics.”

13

Leight, “Why You’re Hearing More Borrowed Lyrics.”

14

Frank Guan, “Rap Dominated Pop in 2017, and It’s Not Going Anywhere

Anytime Soon,” Vulture, December 20, 2017, https://www.vulture.com/2017/12/the-

year-rap-overtook-pop.html.

15

Charlie Harding, “Interpolation Database Year End Hot 100 2010-2011 (2022

top 10)” Unpublished raw data, Accessed February 2023.

8

producing pop songs and hip-pop (hip-hop and pop fusion) were including a significant

increase of interpolations as well. This year also corresponds to the international launch

of TikTok, a social media platform that is currently making major waves in the music

industry.

Some industry experts have identified how music companies’ business strategies

contribute to the popularity of interpolation. Primary Wave, a music publishing company,

is leading the way of interpolation in popular music. According to Kristin Robinson for

Billboard, Primary Wave has actively encouraged artists “to use melodies, lyrics and

samples of the company’s catalog as a way to increase the value of Primary Wave’s

holdings while easing the tedious licensing process for the music makers at the same

time.”

16

In the same article, Robinson highlights Yung Gravy’s 2022 hit “Betty (Get

Money)” as doing just that by interpolating from Rick Astley’s 1987 hit “Never Gonna

Give You Up.” Primary Wave and Hipgnosis Songs Fund have gone on massive

spending sprees in the past two years “collecting publishing rights on legacy hits from

songwriters.”

17

In addition to companies buying songs for their catalog, artists have also

increased the use of sampling and interpolation from other catalogs. Sony Music

Publishing, one of the largest music and entertainment companies in the United States,

announced that in the past couple of years they have “received twice as many requests for

samples and interpolations from its catalog.”

18

16

Kristin Robinson, “How Primary Wave Proved Everything Old Is New Again

With Yung Gravy’s Radio Hit,” Billboard, September 15, 2022,

https://www.billboard.com/pro/primary-wave-yung-gravy-radio-hit-sample-strategy/.

17

Millman, “‘No Shelf Life Now.’”

18

Millman, “‘No Shelf Life Now.’”

9

This trend seems to have been picking up around the release of TikTok in the

United States, and it continues to follow TikTok’s popularity. The design of the TikTok

app encourages creators to collaborate with each other by participating in popular trends

or duetting another video. Additionally, TikTok has a large music catalog for creators to

use in their videos, which contributes to much of the younger American population

discovering new music through the app.

19

It seems to be a goal of producers to get a song

to be viral on TikTok as it brings more listeners to the song and increases traction to the

song on all platforms. Better yet, if a song includes an interpolation, it brings more

listeners to the original song as well. This is not unlike trends with streaming services

such as Netflix, where older TV shows are seeing a resurgence in popularity.

20

Sampling and Terminology

Interpolation fits into a similar category as sampling and musical borrowings. The

literature on sampling is significantly more comprehensive than interpolation. There are

several reasons why this would be the case, one being that sampling is often more easily

quantifiable than interpolation. Additionally, interpolation has undergone different

terminology throughout history which have received varying reactions of acceptance.

Much of the literature that I have reviewed on sampling describes the technique, gives

examples of it in music, and explains copyright cases. Literature, such as That’s the

19

“New Studies Quantify TikTok’s Growing Impact on Culture and Music,”

TikTok Newsroom, July 21, 2021, https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/new-studies-

quantify-tiktoks-growing-impact-on-culture-and-music.

20

Bill Keveney, “Exclusive: Nielsen Finds Nostalgia Fuels Interest in Classic TV

Comedies during Pandemic,” USA TODAY, April 2, 2021,

https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/tv/2021/03/19/nielsen-finds-covid-19-tv-

viewing-spikes-classic-sitcoms/4754533001/.

10

Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader by Murray Forman and Mark Anthony Neal, Rap

Music and Street Consciousness by Cheryl Keyes, and Hip Hop America by Nelson

George, go into the culture of hip-hop and varying aspects of DJ culture, which includes

techniques like sampling, scratching, and mixing.

Amanda Sewell’s “A Typology of Sampling in Hip-Hop” stands out among the

literature on sampling as it identifies one key issue: the lack of a unified terminology for

different types of samples.

21

Sewell provides new terminology for various types of

samples but does not touch much on interpolation. Sewell does mention interpolation

briefly in this dissertation, but only regarding one case study where the lyrics and melody

of the song are reperformed and slightly modified.

22

Instead of describing this example as

interpolation, she refers to it only as musical borrowing.

Sewell is not the only one who has attempted labeling different types of music.

Serge Lacasse coined the terms “allosonic” and “autosonic” quotation to describe musical

borrowing in his 2000 article “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular

Music” where he applies Gérard Genette’s theory of hypertextuality to recorded popular

music.

23

Lacasse specifically refers to “autosonic” being most commonly exemplified as

sampling, defining the term as “as a ‘sameness of sounding.’”

24

He compares “allosonic

quotation” to jazz musicians quoting other songs in improvisation, stating that the

material shared between the original source and the new source “consists of an abstract

21

Sewell, “A Typology of Sampling in Hip-Hop.”

22

Sewell, “A Typology of Sampling in Hip-Hop,” 62.

23

Serge Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular

Music,” The Musical Work: Reality or Invention? Liverpool: Liverpool University Press,

(2000): 35–58. https://doi.org/10.5949/liverpool/9780853238256.003.0003.

24

Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” 39.

11

structure.”

25

Although Lacasse does describe allosonic quotation, he avoids further

discussion by claiming that “it is not especially typical of recording techniques.”

26

The

choice to not dwell on the topic further indicates that mainstream musicians in the year

2000 were not focusing on interpolations.

27

The explanations Lacasse provides for both

allosonic and autosonic quotations are too vague as he does not give concrete definitions

to these concepts, but rather only explains them through examples. The last concept that

Lacasse discusses relating to allosonic is pastiche, which is defined by Genette as “the

imitation of a particular style applied to a brand new text.”

28

This could potentially

include production and stylistic elements of interpolation, but Lacasse describes pastiche

as having “no particular hypotext” meaning that it would not have one particular song

that it is emulating the style of, but rather a genre or band.

29

Lacasse also uses various

other literary terms to refer to other types of musical borrowings, however he does not

describe any more instances that relate to the allosonic category.

Christine Boone has also tried to tackle the concept of interpolation using the term

allosonic. In “Mashing: Toward a Typology of Recycled Music,” Boone describes an

example of interpolation but refers to it as “sound-alikes, or “allosonic quotations” and

even points out that interpolations “will often be called “samples,” even though they are

not technically “sampled” from another commercial recording.”

30

Boone highlights

25

Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” 38.

26

Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” 38.

27

Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” 38.

28

Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” 43.

29

Lacasse, “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music,” 43.

30

Christine Boone, “Mashing: Toward a Typology of Recycled Music,” Music

Theory Online 19, no. 3 (September 1, 2013),

https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.3/mto.13.19.3.boone.html.

12

sound-alikes and sampling as “two distinct production techniques for creating the same

basic musical effect,” focusing on the inclusion for “legal reasons and not always obvious

aesthetic reasons.”

31

Interpolation may have come out of the African-American musical tradition of

Signifyin’ as defined by Henry Louis Gates. According to Christopher Jenkins, Signifyin’

in the musical context can be understood as “a mode of indirect and/or coded

communication, intended to convey multiple meanings specific to various in-groups with

access to specialized information.”

32

By this definition, interpolation functions very

similarly to Signifyin’, in that interpolations are meant to be understood by certain

audiences to provide further meaning to the original text. While Gates mainly refers to

Signifyin’ from a literary standpoint, through written and spoken language, Signifyin’

can also be represented musically as “a way of demonstrating respect for . . . a musical

style, process, or practice” and “Signifyin(g) shows, among other things, either reverence

or irreverence towards previously stated musical statements and values.”

33

Jenkins gives

a concrete example of Signifin’ in music by saying, “an obvious form of signifyin(g) in

instrumental music, classical or otherwise, would be the quotation of reference material,

which could consist of older recordings but also spirituals or other folk songs.”

34

J. Peter

Burkholder further explains the connection of Signifyin’ to popular music:

Re-use, reworking and extension of existing music are basic elements of

West African musical practice and continued in black American music of the 19th

and 20th centuries. The concept of borrowing, developed in the study of European

31

Boone, “Mashing.”

32

Christopher Jenkins, “Signifyin(g) within African American Classical Music:

Linking Gates, Hip‐Hop, and Perkinson,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 77,

no. 4 (Fall 2019): 391–400.

33

Jenkins, “Signifyin(g) within African American Classical Music,” 398.

34

Jenkins, “Signifyin(g) within African American Classical Music,” 396.

13

written repertories, is less appropriate to these traditions than the concept of

sharing materials and traditions. This avoids implications of ownership,

singularity and originality, and acknowledges that there is often no distinct entity

from which to borrow. Recent scholarship has introduced the term ‘signifying’ for

the characteristic approach of black American musicians; the materials of music

are considered common property, and anyone who engages with those materials

in an expressive way is ‘signifying’ on them. As slaves were converted to

Christianity, they adapted work-songs to Christian texts and improvised new

songs on similar material to create a new tradition of spirituals (Epstein, 1977).

Blues and jazz involved improvisation and composition based on existing

harmonies, melodies and bass patterns, and similar practices continued into

popular music derived from black American traditions, including rhythm and

blues and rock and roll.

35

The main difference between Signifin’ and interpolation is that interpolations, at least for

the purposes of this thesis, are inherently tied to economics and the idea of ownership

since songwriting credits must be given to the original songwriter to avoid copyright

issues. This is in direct contradiction with Signifin’ which relies on the belief that the

materials of music are considered common property. Additionally, Signifin’ comes from

elements of West African musical practice and are attributed to Black American

musicians, whereas interpolation has been adopted by several different genres of music.

Burkholder uses three categories to determine musical borrowings: analytical

evidence, biographical and historical evidence, and the purpose of the borrowing.

36

Burkholder’s typology is incredibly useful for identifying musical quotation in classical

music, but it can also be applied to contemporary pop songs as well. This would be

particularly useful for musicologists working in a copyright lawsuit to determine if an

artist borrowed from a previous song without permission. However, when it comes to

identifying interpolations in popular music, there seems to be one key identifier: song

35

Burkholder, “Borrowing.”

36

Burkholder, “Musical Borrowing or Curious Coincidence?”

14

writing credits. In almost every case of interpolation, the songwriter of the original song

will also be credited in the new song. Although, if this information is inaccurate, or

unable to be found, Burkholder’s typology of evidence can be used to identify instances

of interpolation.

Copyright and Social Media

The literature I have reviewed that highlights copyright issues can be found in

both academic literature and music industry magazines and articles. This seems to be a

universal issue affecting artists. Since artists began sampling, they have had to deal with

the issue of copyright, and with music being so easily and quickly accessible to everyone

around the world, the number of copyright cases in music seems to be at an all-time high.

The music industry is changing vastly in the advent of dealing with copyright issues, and

interpolation seems to be one way to avoid these issues.

When artists sample from another song, they must clear their samples, often

paying thousands of dollars to the company that owns the copyright. If an artist is unable

to clear their samples, they can be sued and potentially fined for even more than if they

had cleared it first.

37

Additionally, with sampling comes the issue of having permission to

sample. If an artist does not have permission to use a sample, their song will either be

taken down, or it will be stopped from ever being released in the first place. CJ’s

“Whoopty,” for example, was taken down from YouTube when T-Series – the largest

music record label in India – found that CJ’s song contained an uncredited sample from

37

Joanna Demers, “Sound-Alikes, Law, and Style,” UMKC Law Review 83, no. 2

(Winter 2014): 307.

15

their catalog. According to an interview with VladTV, CJ had to pay $80,000 to get it

cleared to be put back on YouTube and other streaming services.

38

The popularity of this

song launched CJ from an independent SoundCloud artist to being signed to Warner

Records. Without the popularity of this song on social media, it is possible T-Series

would not have found the song to claim the copyright to it, avoiding this controversy

entirely.

With interpolation, however, an artist can avoid the issue of paying for permission

to use the original song. Instead, songwriters from the original song are included in the

credits for the new song, thus giving royalties to the original songwriter and the original

song publisher for the interpolation.

39

Using an interpolation is often cheaper for artists

than using a sample, because there are no upfront costs. Most songwriters will be credited

for an interpolation when a song is released, but fans on social media have taken to

calling out interpolations when they think they hear one, causing some artists to add

songwriting credits retroactively. Olivia Rodrigo is a great example of this.

In 2021, Olivia Rodrigo faced significant controversy on social media with the

release of her first studio album SOUR. Due to gaining a massive amount of fame from

her first single “Driver’s License,” she was bound to face some backlash. The

controversy first started when Courtney Love posted on Facebook claiming that Rodrigo

had copied Hole’s 1994 Live Through This album cover for her release of promotional

38

VladTV, “CJ: “Whoopty” Had an Uncleared Sample from Indian Movie, We

Had to Pay Them $80K (Part 3)” Facebook, April 3, 2022,

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=393572678880924.

39

Millman, “‘No Shelf Life Now.’”

16

photos for the Sour Prom Concert Film.

40

Love did not stop with her criticism though;

when fans on social media started noticing similarities between Rodrigo’s “Good 4 U”

and Paramore’s “Misery Business,” Love put her thoughts out on social media again

bashing Rodrigo and calling her “rude.”

41

The controversy did not end there, and

Rodrigo’s song “Deja Vu” also caused suspicion with fans for being similar to Taylor

Swift’s “Cruel Summer.” This backlash on social media caused Rodrigo’s team to

retroactively add songwriting credits to both Hayley Williams and Taylor Swift onto

SOUR in an effort to avoid any potential copyright lawsuits. This retroactive addition of

songwriting credits now allows the two songs to be considered as including

interpolations, when it might be debatable if these songs are reperforming part of a song,

or if they just fall into a “sound-alike” category for having similar production techniques,

similar timbre, and genre similarities.

Methodology

The methodology I will be using consists of a combination of quantitative and

qualitative research. For the quantitative portion of research, I used WhoSampled.com to

identify direct samples and interpolation in songs from Billboard’s year end Hot 100 for

40

Courtney Love, “Spot the difference! #twinning! @oliviarodrigo,” Facebook,

June 24, 2021,

https://www.facebook.com/courtneylove/posts/345959820223117?comment_id=3468230

63470126&reply_comment_id=346831413469291&__cft__[0]=AZW4v93VRC2IYkum

eqmzZj7Sm-8kfh_XkfBUesiI6S22-zDqp_mfXyCpxjAb7-

8caGN4LEmoGZ6dUBkCbkZi5ITrIkAGSApVLd4w5ls__tIvmvA9IhtmSNDQCO2uu4_

oNbqctfhHiOLyaVMtzfZ_BN07&__tn__=R]-R.

41

Ashley Iasimone, “Courtney Love Accuses Olivia Rodrigo of Copying Hole

Album Cover Concept for ‘Sour Prom’ Photos,” Billboard, June 28, 2021,

https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/courtney-love-olivia-rodrigo-album-cover-

sour-prom-9593423/.

17

the United States for the span of 2017-2022. WhoSampled.com is a user-generated site

that pinpoints samples from songs, highlights what song the sample is from, states where

the sample is being used in the song and from what portion of the original song it is taken

from. According to their website, WhoSampled.com allows music enthusiasts to identify

the “DNA” of songs and to better understand musical connections.

42

I have chosen to use

this website because it is highly comprehensive, with the website stating that is the

“world’s most comprehensive, detailed and accurate database of samples, cover songs

and remixes.”

43

While the website is very extensive, it does not specify beyond direct

sampling or interpolation (referred to as “replayed-samples” on the website) so I will

have to do my own further analysis to determine the specifics. Because

WhoSampled.com is a user-generated site with some inaccuracies, I also referred to

Charlie Harding’s Interpolation Database from 2010-2023. This is an unpublished

database used with permission that lists interpolations and samples from songs on

Billboard’s Year-End 100 charts. I have chosen to focus on the years 2017-2022 because

interpolation has become a more popular trend starting in 2017, and has a close

correlation with the launch of TikTok in 2018. Additionally, because of social media and

the pandemic, the ways people listen to music and the ways music are produced have

drastically changed. By analyzing these years, I have observed a few years prior to the

pandemic, during the pandemic, and coming out of the pandemic to really identify and

understand the changes happening.

42

Whosampled, “WhoSampled.com - About Us,” YouTube video, 1:26, Jan 10,

2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z9SgiN5g9mY.

43

“About Us,” WhoSampled.com, 2023, https://www.whosampled.com/about/.

18

The qualitative research is from analyzing current sources’ significance over

interpolation. This is mostly explored through my literature review, but also through the

case studies presented. Much of the literature comes from trade publications, which are

leading the conversations around interpolation in the music industry. Other sources in the

literature review include academic resources focusing on sampling and other musical

borrowings. Outside of these sources, I have analyzed various social media outlets to see

how fans are responding to interpolation, and through primary sources such as recorded

interviews with artists.

Limitations/Delimitations

Because of the nature of this study there are some limitations to address. I will

only analyze songs from Billboard’s Year-End Hot 100 from 2017-2022. I chose to limit

the years in order to create a manageable sample size, and I used Billboard because of its

reputability, consistency, and the inclusion of streaming listens as well as sales, radio

plays, etc. Additionally, I will mostly be focusing on artists that fall into the genre of pop

to see how artists from this genre are interpreting techniques that are usually associated

with hip-hop.

Conclusion

This thesis demonstrates how pop artists are using interpolation, how the industry

is interacting with interpolation, and how fans are responding to interpolation. Through

the case studies presented, this thesis identifies three main types of interpolation:

melodic, textual, and production. This document also addresses how commercialization

of music and the economic aspects behind it greatly impact interpolation. For the

19

purposes of this research, interpolation is inseparable from capitalization, as credits are

given to songwriters, or copyright is bought from music publishers, to act as a monetary

form of accountability. Social media is heavily intertwined as well, as fans are noticing

and reacting to interpolations, and in many cases influencing how interpolations are being

credited.

20

CHAPTER 2

CASE STUDIES

As discussed in the previous chapter, interpolation is the musical technique of

taking a previously recorded song and re-performing a portion of that track, whether it be

the sung melody, lyrics, part of an instrumental line, or stylistic production techniques,

and including it in the creation of a new song. While many authors who have written on

the phenomenon group all manifestations of interpolations together, for my research, I

have identified three main types of interpolation: melodic interpolation, textual

interpolation, and production interpolation. An interpolation is not limited to just one of

these categories, rather it can be any combination of multiple categories, although one

category may be more prominent than others.

Melodic interpolation is when part or all of a melody is taken from a previously

recorded song and reperformed, often with different lyrics, in the creation of a new song.

Melodic interpolations seem to be the most common, or at least the most easily

identifiable. While most melodic interpolations seem to be in the vocal line, they are not

limited to the vocal line. They can also be present in instrumental lines, such as lead

guitar, or other instrumental solos. As an example of melodic interpolation, the chorus of

Doja Cat’s “Kiss Me More” borrows the melody of the chorus to Olivia Newton-John’s

“Physical.” Both songs give credit to Olivia Newton-John’s songwriters Stephen Kipner

and Terry Shaddick.

21

Textual interpolations are where a significant portion of the text from a

prerecorded song is being incorporated into a newly created song. These interpolations

vary from covers because they interpolate a significant portion of the lyrics, but not all of

them, and new text is also incorporated. These seem to be the least common type of

interpolation in current top hits. However, text interpolation is one of the earlier forms of

interpolation, such as interpolated vocality and interpolated verbalism. These are two

techniques are used in African-American music, where vocalists add additional vocal

sounds or text to a song.

44

So while this is not as common in pop hits, this is one of the

earliest traceable forms of the term “interpolation” and is important to highlight as a type

of interpolation. One could argue that Brittany Spears and Elton John’s “Hold Me

Closer” is a text interpolation of Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” and “The One.” “Hold Me

Closer” contains both the melody and text of the chorus from “Tiny Dancer” and also

includes both the melody and text from two verses of “The One.” Potentially this song

could be considered a remix or mashup, but with the addition of Brittany Spears’ vocals

and a completely new instrumental background, it becomes an entirely new song.

What is more common in pop hits than text interpolations is quotation or allusion

to the text of another song. Alluding to another song through text incorporates borrowing

portions of lyrics in a way that the lyrics cannot be copyrighted. A good example of this

is Miley Cyrus’s 2023 single “Flowers” where she is alluding to Bruno Mars’s “When I

Was Your Man.” Many fans on social media have speculated that Miley was copying

Bruno Mars because of the similar lyrics, such as Bruno Mars’s lyrics, “I should have

44

Earl L. Stewart, African American Music: An Introduction (New York:

Schirmer Books, 1998): 6.

22

bought you flowers/ And held your hand” while Miley Cyrus’s lyrics are stating: “I can

buy myself flowers,” and “I can hold my own hand” along with several other lyrics that

are similar.

45

However, Bruno Mars’s lyrics occur one line after another, and with Miley

Cyrus, her lyrics are broken up in the chorus, with other lyrics in between them. There

are other similarities between lyrics, however the lyrics are never quoted directly, and

words like “flowers” and “hand” cannot not be copyrighted on their own. Because the

lyrics are not being directly taken from Bruno Mars’s song, “Flowers” does not contain

an interpolation, but rather functions as allusion to his song, in a type of trend known as a

response song.

46

Production interpolations are the most ambiguous and therefore the most difficult

to identify. A production interpolation may only emulate one production aspect of a

prerecorded song, or it may emulate multiple aspects. These aspects include but are not

limited to texture, instrumentation, style, and timbre. OneRepulic’s 2022 single “I Ain’t

Worried,” written for and featured in the 2022 movie Top Gun: Maverick, features a hook

that is entirely whistled. Although the melody is vastly different, the song’s association

with the alternative genre and the overall shape of the melodic line of the whistle can

cause some listeners to think of another song incorporating an iconic whistled hook:

“Young Folks” by Peter Bjorn and John. Although these two songs are very different, for

the case of “I Ain’t Worried” Paramount Productions decided to add songwriting credits

45

Bruno Mars, “When I Was Your Man,” Track 6 on Unorthodox Jukebox,

Atlantic Records, 2012, Spotify streaming audio, and Miley Cyrus, “Flowers,” Single,

Columbia Records, 2023, Spotify streaming audio.

46

Charlie Harding, Nate Sloan, and Reanna Cruz, “‘Flowers’ and the Art of the

Response Song,” Switched on Pop, Podcast audio, February 14, 2023,

https://switchedonpop.com/episodes/flowers-miley-cyrus-bruno-mars-response-song.

23

to Peter Bjorn and John as preventative measures in case any other listeners were also

reminded of “Young Folks.”

47

What this case is hinting at is something that is often

called a “sound-alike,” which is very ambiguously described as a song that sounds like

another song. Several factors can lead to songs becoming labeled as a sound-alike, such

as same harmonic progression, same key, same tempi, closely related timbre, closely

related texture, same style of genre, and same rhythmic aspects. For something to be

considered a production interpolation it usually has to contain multiple of these elements.

While one element present could lead to a production interpolation – like the whistled

hook – most of the time one element alone will not cause enough of a resemblance.

Harmonic progressions and rhythms themselves cannot be copyrighted, however these

aspects paired together or combined with other musical elements can be copyrighted,

such as in the case of The Chainsmokers’ “Closer.” The harmonic progression in

“Closer” is near identical to The Fray’s “Over My Head (Cable Car)” and both songs are

in the key of Ab. While The Chainsmokers have a much more synthesized and pop sound

than The Fray, the harmonic progression paired with the same prominent rhythm played

in the piano/synthesizer on both songs for these harmonic progressions necessitated the

need to credit both Joe King & Isaac Slade from The Fray as songwriters for “Closer.”

The Chainsmokers take this element a step further and incorporate it into their melody,

making the similarities even more clear. While identifying a production interpolation can

be difficult and up to interpretation, many artists that recognize their song as a potential

47

Chris Willman, “Ryan Tedder Whistled While He Worked: OneRepublic’s

Frontman on Crafting a ‘Top Gun’ Soundtrack Smash With ‘I Ain’t Worried,’” Variety,

November 30, 2022, https://variety.com/2022/music/news/ryan-tedder-onerepublic-i-aint-

worred-top-gun-maverick-hit-song-whistle-1235446172/.

24

sound-alike will give credits to the songwriter of the original song in order to prevent any

future copyright issues.

These three types of interpolations are not the only kinds present in contemporary

popular music, but these seem to be the most common. With all three of these types of

interpolations, songwriting credits are given for the original song’s songwriter, and the

original songwriter is then paid royalties for that song. While some songs may seem like

they fit into any of these categories of interpolations, for the purposes of my research, a

song only contains an interpolation if songwriting credits are given to the original

songwriter. For example, “Memories” by Maroon 5 does incorporate the melody from

Pachelbel’s Canon in D, but due to the original piece being available for public domain,

no songwriting credits are given to the composer. Thus, for the purposes of this thesis,

“Memories” is a great example of musical borrowing, but it is not a true interpolation.

The definition of interpolation throughout this document relies on economic and

copyright aspects, because of ambiguities that result from current copyright laws. While

copyright protects recorded music, the only clear way to prove these protections is from a

song’s composition, which is not physically available for most pop songs since this genre

comes from an oral tradition. Therefore, the credits are given to the songwriter for

composing the song, because there is no physical score to prove similarities or

dissimilarities between the two songs. The songwriting credit provides royalties to the

original songwriter, allowing them to be paid for their composition. If songs are

borrowing from public domain, no royalties need to go to another writer, thus putting

them into a different category of musical borrowing.

25

The songs I will be analyzing are all by artists that are traditionally known for

fitting into the pop genre. The reason for this is to understand how pop artists are

interpreting techniques more commonly used by hip-hop artists and how this is impacting

the popular music charts. While there is also value in analyzing hip-hop artists that are

incorporating interpolations, because of the association with hip-hop and sampling,

musical borrowing is generally more accepted in hip-hop genres, and is dealt with

differently than in other genres.

“7 Rings” by Ariana Grande

One of the clearest examples of melodic interpolation is Ariana Grande’s 2019 hit

“7 Rings” which landed at aptly enough at #7 for Billboard’s 2019 Year End Hot 100.

48

Each verse in Grande’s “7 Rings” interpolates portions of the melody from the verses of

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things” from the musical The Sound of Music

(1959). While Grande strays from the interpolated melody in the pre-choruses and

choruses going into a more hip-hop rap spoken-lyric rhythmic vocal style, each verse

includes the interpolation. Additionally, “7 Rings” mimics the minor key of “My Favorite

Things.” While the harmonic progression for “7 Rings” is simplified compared to “My

Favorite Things,” both follow a similar harmonic progression. “My Favorite Things”

mainly uses a chord progression of i-VI-iv-VII-III, hinting at the relative major key

toward the end of the progression with ii-V-I, while “7 Rings” simplifies this with the

progression to i-VI-iv-V, a minor version of the 50s’ Doo-Wop progression. The

progression in “My Favorite Things” likely reflects the positive mood that Maria’s

48

“Year End Charts: Hot 100 Songs 2019,” Billboard, Accessed February 2023,

https://www.billboard.com/charts/year-end/2019/hot-100-songs/.

26

character is put in from thinking about her favorite things, or the positive mood that she is

trying to reflect upon the children when they are scared of the thunderstorm. The

harmonic progression for “7 Rings” is similar, but only sticks to the Doo-Wop

progression in a minor key. It leaves out the last two chords hinting to the relative major

and instead uses the minor key throughout the entire song. Whether intentionally left out

by the songwriters or not, removing the hint toward the relative major leaves a different

impact on the listeners.

Many middle-class American audience members would be able to identify the

melodic interpolation in this song, as The Sound of Music is an incredibly popular film

and musical in the United States. “7 Rings” provides several cues to the original song in

addition to the borrowed melody. Some of the lyrics are similar to the original song, thus

cueing the listener into the context of “7 Rings.” For instance, if a listener did not pick up

on the melody from “My Favorite Things,” then they may be able to catch the reference

to the original song from Grande’s line “Buy myself all of my favorite things.”

49

This

should cue the listener to the reference from the original song, but if not, Grande also

makes a couple of other references in her lyrics such as “Rather be tied up with calls and

not strings” which is referencing the line “Brown paper packages tied up with strings”

from “My Favorite Things.”

50

These references provide an extra and further added meaning to the song. In this

instance, Grande is singing about money and other luxuries such as diamonds and

49

Ariana Grande, “7 Rings,” Track 10 on Thank U, Next, Republic Records,

2019, Spotify streaming audio.

50

Rodgers & Hammerstein, “My Favorite Things,” Performed by Julie Andrews,

Track 7 on The Sound of Music (Original Soundtrack Recording, RCA Victor, 1965,

Spotify streaming audio.

27

champagne rather than ephemeral and mundane pleasures such as observing raindrops on

roses. While Julie Andrews’s interpretation of Maria in the film adaptation of The Sound

of Music sings “My Favorite Things” to the children to comfort them during a storm, the

items in the song feel very humble and innocent, simple things just to comfort the

children. To her, the things listed in the song are “nice things” although they have no

monetary value. This goes along with her character in the movie, being more demure, as

further seen when she stops singing to the children when Captain Georg von Trapp walks

in, and he immediately is the one in charge of the situation.

51

In this adaptation, the man

acts as the provider while Maria is only in charge of caring for the children. In the

musical version of The Sound of Music, however, Maria sings this song in a very

different context. Mother Abbess and Maria bond over the song as it is a shared

childhood song for the both of them.

52

Mother Abbess realizes that Maria is not quite

ready to commit to the religious life of a nun, as she is comforting herself with music and

with materialistic things, things she should not be comforted by, and especially because

she has difficulty following rules about when she does not have permission to sing.

The context of “My Favorite Things” in the musical more closely relates to the

narrative context of Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings.” Both Maria and Ariana Grande are

singing about materialistic things, although Ariana Grande’s lyrics are much more

focused on contemporary materialism. The callback to “My Favorite Things” implies that

money and/or luxury goods are Grande’s favorite things, going so far as Grande even

51

The Sound of Music, directed by Robert Wise, (Twentieth Century Fox Home

Entertainment, 1965), 2 hrs. 54 min., DVD.

52

“The Sound of Music Stage Synopsis,” The Rodgers & Hammerstein

Organization, 2022, https://rodgersandhammerstein.com/the-sound-of-music-stage-

synopsis/.

28

implying that happiness can be bought, equating a pair of Louboutin heels to happiness.

53

In addition to the similarities in context to the musical version of Maria, Grande’s

persona of the song more closely aligns with Maria’s character in the musical. In the film

adaptation, Maria acts as more of a submissive character, while the musical version

shows her being a stronger and more independent woman. Grande captures this strong

independent persona as she is relying on herself to purchase the expensive goods that

bring her comfort, rather than relying on a man to provide for her. She captures an

incredibly independent character as she buys anything she wants immediately, and even

denounces needing a man tied to her side with the lyrics “Wearing a ring, but ain’t gon’

be no “Mrs.”/ Bought matching diamonds for six of my bitches.”

54

This shows Grande’s

independence and focus on supporting other women, rather than being tied to a man.

Grande has a widespread audience, with much of them being from younger generations,

so picking a well-known song to interpolate, like “My Favorite Things” ensures that her

audience will recognize the interpolation and understand the contextual connection.

Additionally, with the strong independent persona that Grande is capturing, it is ensuring

her audience that they can be strong independent women too.

Ariana Grande is known as a pop artist with R&B influences. However, Thank U,

Next, the album that “7 Rings” is from, strays a little from her traditional sound and is

noted to have a strong trap influence. This influence can be heard lyrically through

themes of flaunting wealth and musically especially through the hi-hat and drums in the

latter half of this song. Before Grande’s success with her solo career as a pop singer, she

53

Ariana Grande, “7 Rings.”

54

Ariana Grande, “7 Rings.”

29

was known for her singing and acting. Her appearance as Cat Valentine in the

Nickelodeon show Victorious propelled her into the spotlight, but her first experience

with acting and singing professionally was in the Broadway show 13 in 2008.

55

Grande

states that “7 Rings” was inspired by a personal experience of shopping with her friends

at Tiffany’s. Because of this personal account, it seems like Grande and her team of

songwriters may have also included some other of her personal experiences in the

creation of this song. With the influence of Tiffany’s and the reference of Breakfast at

Tiffany’s, it is possible that Grande is also capturing the independent persona of Holly

Golightly from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Holly, played by Audrey Hepburn, is an

independent woman who lives by herself and fancies nice things, such as Tiffany’s.

Holly, while reliant on men for her money, still makes decisions on her own, and always

makes choices that are in her best interest and help support her eccentric lifestyle. Grande

embodies this independent and materialistic personality in “7 Rings” and in both cases,

materialism is not seen as a bad thing, but rather as a way that the women are able to

support and provide for themselves. “7 Rings” addresses past constructions of female

agency and power through referencing both The Sound of Music and Breakfast at

Tiffany’s. Maria in The Sound of Music openly treasures things that are free, and Holly in

Breakfast at Tiffany’s relies on men to purchase her nice things, but Grande has the

power to buy luxuries for herself. Grande demonstrates a new construction of female

agency through economic empowerment.

55

“Ariana Grande,” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 22, 2022,

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ariana-Grande.

30

With her background in Broadway, it is unsurprising that Grande would be

familiar with the musical The Sound of Music. With the form of her song starting with the

interpolation from “My Favorite Things” and ending with a much more trap influence

style of music, it is almost as if Grande is expressing her life changing from her

beginnings in Broadway, to where she is currently, as a very successful R&B influenced

pop artist. However, not everyone has been supportive of Grande’s R&B and trap

influences. “7 Rings” has been speculated to also contain references to The Notorious

B.I.G.’s “Gimme the Loot” and Princess Nokia’s “Mine” with claims that Grande copied

both lyrics and flow from these two songs.

56

No credits have been given to either of the

artists, and many people have claimed that Grande has gotten away with “stealing” from

them.

This is not the first time that Grande has been accused of stealing or appropriating

from Black artists and Black culture. Grande has been accused several times of

Blackfishing, (when someone changes their appearance or personality to imitate and

appear as a Black person) due to darkening her skin significantly with tanner.

Additionally, Grande has borrowed traits of Black fashion such as her iconic slicked-back

high ponytail. Although this hairstyle is closely associated with Ariana Grande, it brought

her some critiques within “7 Rings” with her lyrics “you like my hair, gee thanks, just

bought it.”

57

Ariana Grande is praised for her high ponytail with long extensions, but

when Princess Nokia sings about her hair in “Mine” saying “it’s mine, I bought it”

56

Spencer Kornhaber, “How Ariana Grande Fell Off the Cultural-Appropriation

Tightrope,” The Atlantic, January 23, 2019,

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/01/ariana-grandes-7-rings-

really-cultural-appropriation/580978/.

57

Ariana Grande, “7 Rings.”

31

referring to the hairpieces of Black women, she points out in her song how Black women

are regularly ridiculed for this hairstyle instead of being praised like Ariana Grande.

58

Additionally, Grande has previously been accused of appropriating Japanese culture by

getting a tattoo for “7 Rings” that she believed said “7 Rings” in Japanese characters, but

was actually the name of a popular brand of grill.

59

This is not the only time she has

appropriated Asian culture, as she was also accused of Asianfishing from a since deleted

Instagram photoshoot where her skin appears lighter than her usual appearance, and her

makeup has been altered to make her features look more like a K-Pop star. Grande is just

one instance of a white artist appropriating from other cultures and not providing any

accountability for their actions, a trend that has been prevalent among white artists since

the beginnings of American popular music.

Despite these instances of controversy, “7 Rings” is still Grande’s most popular

song, and for the most part she remains positively in the public eye. “7 Rings” was

undoubtedly popular with Grande’s fans, gaining popularity as her second top song on

Spotify. Many fans commented on the official music video for “7 Rings” with praise as

their favorite song or a song they listen to on repeat. By including the interpolation from

“My Favorite Things,” “7 Rings” also rose to success with audiences outside of her

fanbase, from those that found familiarity with the melody. “7 Rings” was able to

introduce many of Grande’s fans to “My Favorite Things” and many fans of The Sound

58

Princess Nokia, “Mine,” Track 5 on 1992 Deluxe, Rough Trade Records, 2017,

Spotify streaming audio.

59

Spencer, “How Ariana Grande Fell Off the Cultural-Appropriation Tightrope.”

32

of Music may have been introduced to trap inspired music though “7 Rings,” perhaps

enjoying a new music genre they may have not listened to before.

“Kings and Queens” by Ava Max

“Kings and Queens” by Ava Max is a great example of a song that includes both a

melodic and production interpolation. Additionally, this song does not share a

songwriting credit with just one song, but rather it shares a songwriting credit with two

different songs. “Kings and Queens” by Ava Max, “You Give Love a Bad Name” by Bon

Jovi, and “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man)” by Bonnie Tyler all give

songwriting credits to Desmond Child, who wrote the iconic hook that can be heard in

each of these songs.

Not only does “Kings and Queens” share a hook with both of these songs, but it

also shares aspects of form and texture at several points. As one can see in Figure 2.1 and

2.2, each song follows a fairly typical verse-chorus form with the inclusion of a pre-

chorus and a bridge. While this form is not unusual for popular music during these time

periods, what is somewhat unusual and unique is that all three songs start with the chorus

before the first verse. Additionally, the production is very similar throughout the hook in

each song. As seen in Figure 2.1, “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man)” starts out

with a very densely textured choir singing the full hook/chorus with added reverb on the

voices. “You Give Love a Bad Name” begins with a chorus of voices by the band

members who only sing the first half of the hook rather than the entire chorus, also with

an intense added reverb. “Kings and Queens” starts out very similar to both of these

songs, with the full hook/chorus being sung by Ava Max’s voice layered rather than

33

including other singers, imitating that same reverb as the previous songs. This is a rather

unique instance included in each of these songs, whereas many other examples of

interpolation do not attempt to create such intense textural and timbral similarities in

addition to the inclusion of the interpolated melody. While these production techniques

alone do not necessarily state the need to list songwriting credits, they do contribute to

the overall similarity to the original pieces, so when paired with the melodic

interpolation, makes the interpolation even clearer.

34

Figure 2.1 A diagram for the first half of the songs “Kings and Queens,” “You Give Love a Bad Name,” and “If

You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man.)” This chart demonstrates the similarities in the three songs’ forms and

points out important timbral and textural changes to listen for during each section.

35

Figure 2.2 A diagram for the second half of the songs “Kings and Queens,” “You Give Love a Bad Name,” and

“If You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man.)” This chart demonstrates the similarities in the three songs’ forms

and points out important timbral and textural changes to listen for during each section.

36

The similarities of “Kings and Queens” to its predecessors does not stop there. As

seen in Figure 2.2, all three songs include an instrumental section either during or around

the bridge, with a focus on an instrumental solo. Bonnie Tyler’s song includes a

saxophone solo as a link right before the bridge, Bon Jovi includes a guitar solo during

the bridge, and Ava Max includes a Dance chorus before the bridge that also features a

guitar solo. Additionally, all three songs include an outro/terminal climax that is mostly

instrumental, which builds through to the end. Both Ava Max and Bon Jovi include some

backing vocal embellishments in the form of “ohs” while Bonnie Tyler includes an

improvised saxophone solo until the end. Both “You Give Love a Bad Name” and “If

You Were a Woman (And I Was a Man)” fade out before the song ends, while “Kings

and Queens” includes a conclusive final cadence in the electric guitar. Although these

three songs do not all end with a fade out, this is unsurprising as pop songs that fade out

were really popular between the 1950s’ to the mid-1980s’ but fell out of favor at the turn

of the century.

60

It would be rather unusual for a Top 40 song during the 2020s’ to

include a fade out, so the cold end is likely just due to the popular nature of such an

ending. The form of a song is not a copyrightable element as song forms have been

copied and followed since practically the beginning of music. We see this in the

commonality of classical forms such as sonata, concerto, and rondo forms. Verse/chorus

forms in pop music tend to be the most popular, but switching up the form does not

change the song that drastically. How closely these three songs follow a similar form just

60

William Weir, “The Fade-out in Pop Music: Why Don’t Modern Pop Songs

End by Slowly Reducing in Volume?,” Slate, September 14, 2014,

https://slate.com/culture/2014/09/the-fade-out-in-pop-music-why-dont-modern-pop-

songs-end-by-slowly-reducing-in-volume.html.

37

adds to the defense of a production interpolation, but alone would not constitute it as

such.

“Kings and Queens” includes other stylistic aspects of both the ‘80’s pop sound

from Bonnie Tyler’s song and the ‘80’s hair metal rock sound from Bon Jovi. The

inclusion of power chords in the synthesizer during the second half of the first chorus and

throughout the second and third choruses of “Kings and Queens” is very reminiscent of

the synths often used in ‘80’s pop music. While “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a

Man)” does not use the synth in the same way as “Kings and Queens,” the synth can be

heard playing the bassline throughout much of the song. “You Give Love a Bad Name”

does also include a synthesizer in parts of the song, however it does not play as

prominent of a role as in “Kings and Queens” or “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a

Man.)” “Kings and Queens” does seem to be at least somewhat emulating that nostalgic

‘80’s pop sound, a sound that has become increasingly popular around 2020. Not only

does this show the song is keeping up with trends at the time, but it also pays homage to

Bonnie Tyler’s song specifically more so than Bon Jovi’s with the emphasis on the

synthesizer over other instruments, the pop style over a rock sound, and the focus on

female vocals.

While the intention may not have been to pay greater homage to Bonnie Tyler

rather than Bon Jovi, Ava Max does say in an interview with Kelly Clarkson that this

song is about equality stating, “growing up I saw a lot of men in positions of power, and

38

not enough queens.”

61

This statement is present even now with the greater popularity

today of “You Give Love a Bad Name” over “If You Were a Woman (And I Was a

Man.)” Many comments on Ava Max’s official music video of “Kings and Queens” state

that she is “copying” or “stealing” from Bon Jovi, whereas much fewer comments say

anything about Bonnie Tyler. The choice of an ‘80s’ pop sound of “Kings and Queens”

rather than a ‘80’s rock sound very well could be to pay homage and bring more attention

to the “queen” Bonnie Tyler who has been overshadowed by Bon Jovi, at least with the

comparison of popularity of these two songs.

“Good 4 U” by Olivia Rodrigo

Olivia Rodrigo’s work is a very interesting case for interpolations. Several of her

songs are classified as having additional songwriting credits, thus implying interpolation,

though many instances of interpolations in her music are ambiguous and not obvious to

many listeners. In the previous chapter I discussed an instance of Olivia Rodrigo

retroactively adding songwriting credits to Hayley Williams and Josh Farro from the

band Paramore, on Rodrigo’s song “Good 4 U” due to the resemblances to Paramore’s

“Misery Business.” When analyzing these songs, the melodies are not the same. As

Adam Neely points out in his YouTube video “Did Olivia Rodrigo steal from Paramore?

(analysis)” the two songs share a melodic contour targeting “the same tones every four

bars in the chorus,” starting on scale degree 3, going to scale degree 2, and then ending

61

Salty, “Ava Max - Interview and “Kings & Queens” Performance with The

Kelly Clarkson Show,” YouTube video, 9:06, September 22, 2020,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ujMWu8Ucig.

39

on scale degree 1.

62

This does effectively make the listener focus on these target tones,

which can lead to the choruses sounding the same for some listeners, despite the rest of

the melodies differing.

While they follow a similar shape at times, the melodies are different enough that

it would not be considered an issue of copyright. Many fans may not have picked up on

this fact, since most of Rodrigo’s fanbase are not musicologists, but many of them have

noticed the comparable production techniques. Both songs emulate the punk-pop style,

with heavy reliance on a strong backbeat in the drums, distorted electric guitar at the

forefront, upbeat tempo, and prominence of a harsher voice. The overall textures both

contain comparable instrumentation, and the timbre of both songs are also similar. Both

songs do have some resemblance in the vocals, characterized by having impressive large

leaps to high notes in the second half of the songs. Additionally, both choruses have the

same harmonic progression: IV-I-V-vi, a rotation of the axis progression. Neely also

points out that both songs have a similar harmonic scheme, starting in the relative minor

during the verses and then progressing to the major during the choruses.

63

Despite these

harmonic coincidences, harmony alone cannot be copyrighted. Yet, due to production

techniques (such as similarities in texture, timbre, style, harmony, and syncopation)

paired with shared themes of relationship angst, fans can pick up on a similar “feel” or

“vibe” in both songs, thus resulting in the sound-alike quality of these songs.

62

Adam Neely, “Did Olivia Rodrigo Steal from Paramore? (Analysis,)” YouTube

video, 10:50, August 30, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qX7a2p5_JsM.

63

Neely, “Did Olivia Rodrigo Steal from Paramore?”

40

This is not the first instance of an artist being scrutinized for potential copyright

issues due to a production interpolation. When Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams

released the single “Blurred Lines” in 2013, the Marvin Gaye estate found it to sound

incredibly close to Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give it Up” and sued Thicke and Williams for

copyright infringement by not providing a songwriting credit to Marvin Gaye. Despite

“Blurred Lines” not borrowing any melodic or direct reperformed elements of “Got to

Give it Up,” the estate argued that it has the same “feel” and “sound.”

64

In regard to the

validity of the argument, copyright can be awarded to the composition of a piece, but

neither a harmony nor a “feel” can be copyrighted, however they can “contribute to the

copyrightability of a musical composition as a whole.”

65

The wording of copyright laws

with recorded music can be interpreted as ideas themselves cannot be copyrighted, but

expressions of ideas are.

66

Williams may have been inspired by “Got to Give it Up,” but