The History of the Police

The History of the Police

SECTION

1

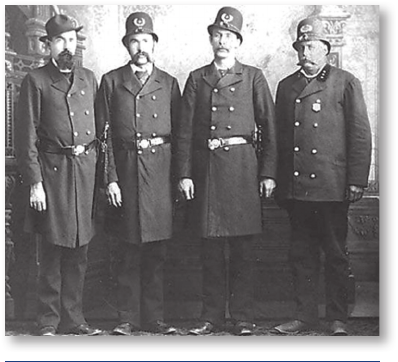

Native American police officers—1883

I

t is important to examine the history of policing in the United States in order to understand how it has

progressed and changed over time. Alterations to the purpose, duties, and structure of American police

agencies have allowed this profession to evolve from ineffective watch groups to police agencies that incor-

porate advanced technology and problem-solving strategies into their daily operations. This section provides

an overview of the history of American policing, beginning with a discussion of the English influence of Sir

Robert Peel and the London Metropolitan Police. Next, early law enforcement efforts in Colonial America are

discussed using a description of social and political issues relevant to the police at that time. And finally, this

section concludes with a look at early police reform efforts and the tension this created between the police and

citizens in their communities. This section is organized in a chronological manner, identifying some of the

most important historical events and people who contributed to the development of American policing.

y The Beginning of American Policing:

The English Influence

American policing has been heavily influenced by the English system throughout the course of history. In

the early stages of development in both England and Colonial America, citizens were responsible for law

• Examine the English roots of American policing.

• Understand evolution from watch groups to formalized police agencies.

• Look at the professionalization of the police through reform.

Section Highlights

2

Section 1 The History of the Police 3

enforcement in their communities.

1

The English referred to this as kin police in which people were respon-

sible for watching out for their relatives or kin.

2

In Colonial America, a watch system consisting of citizen

volunteers (usually men) was in place until the mid-19th century.

3

Citizens that were part of watch groups

provided social services, including lighting street lamps, running soup kitchens, recovering lost children,

capturing runaway animals, and a variety of other services; their involvement in crime control activities at

this time was minimal at best.

4

Policing in England and Colonial America was largely ineffective, as it was

based on a volunteer system and their method of patrol was both disorganized and sporadic.

5

Sometime later, the responsibility of enforcing laws shifted from individual citizen volunteers to groups

of men living within the community; this was referred to as the frankpledge system in England.

6

The

frankpledge system was a semistructured system in which groups of men were responsible for enforcing the

law. Men living within a community would form groups of 10 called tythings (or tithings); 10 tythings were

then grouped into hundreds, and then hundreds were grouped into shires (similar to counties).

7

A person

called the shire reeve (sheriff) was then chosen to be in charge of each shire.

8

The individual members of

tythings were responsible for capturing criminals and bringing them to court, while shire reeves were

responsible for providing a number of services, including the oversight of the activities conducted by the

tythings in their shire.

9

A similar system existed in America during this time in which constables, sheriffs, and citizen-based

watch groups were responsible for policing in the colonies. Sheriffs were responsible for catching criminals,

working with the courts, and collecting taxes; law enforcement was not a top priority for sheriffs, as they

could make more money by collecting taxes within the community.

10

Night watch groups in Colonial

America, as well as day watch groups that were added at a later time, were largely ineffective; instead of

controlling crime in their community, some members of the watch groups would sleep and/or socialize

while they were on duty.

11

These citizen-based watch groups were not equipped to deal with the increasing

social unrest and rioting that were beginning to occur in both England and Colonial America in the late

1700s through the early 1800s.

12

It was at this point in time that publicly funded police departments began

to emerge across both England and Colonial America.

Sir Robert Peel and the London Metropolitan Police

In 1829, Sir Robert Peel (Home Secretary of England) introduced the Bill for Improving the Police in and

Near the Metropolis (Metropolitan Police Act) to Parliament with the goal of creating a police force to

manage the social conflict resulting from rapid urbanization and industrialization taking place in the city

of London.

13

Peel’s efforts resulted in the creation of the London Metropolitan Police on September 29,

1829.

14

Historians and scholars alike identify the London Metropolitan Police as the first modern police

department.

15

Sir Robert Peel is often referred to as the father of modern policing, as he played an integral

role in the creation of this department, as well as several basic principles that would later guide the forma-

tion of police departments in the United States. Past and current police officers working in the London

Metropolitan Police Department are often referred to as bobbies or peelers as a way to honor the efforts of

Sir Robert Peel.

16

Peel believed that the function of the London Metropolitan Police should focus primarily on crime

prevention—that is, preventing crime from occurring instead of detecting it after it had occurred. To do

this, the police would have to work in a coordinated and centralized manner, provide coverage across large

designated beat areas, and also be available to the public both night and day.

17

It was also during this time

that preventive patrol first emerged as a way to potentially deter criminal activity. The idea was that citizens

4 PART I OVERVIEW OF THE POLICE IN THE UNITED STATES

would think twice about committing crimes if they noticed a strong police presence in their community.

This approach to policing would be vastly different from the early watch groups that patrolled the streets in

an unorganized and erratic manner.

18

Watch groups prior to the creation of the London Metropolitan Police

were not viewed as an effective or legitimate source of protection by the public.

19

It was important to Sir Robert Peel that the newly created London Metropolitan Police Department be

viewed as a legitimate organization in the eyes of the public, unlike the earlier watch groups.

20

To facilitate

this legitimation, Peel identified several principles that he believed would lead to credibility with citizens

including that the police must be under government control, have a military-like organizational structure,

and have a central headquarters that was located in an area that was easily accessible to the public.

21

He also

thought that the quality of men that were chosen to be police officers would further contribute to the orga-

nization’s legitimacy. For example, he believed that men who were even tempered and reserved and that

could employ the appropriate type of discipline to citizens would make the best police officers.

22

It was also

important to Peel that his men wear appropriate uniforms, display numbers (badge numbers) so that citi-

zens could easily identify them, not carry firearms, and receive appropriate training in order to be effective

at their work.

23

Many of these ideologies were also adopted by American police agencies during this time

period and remain in place in some contemporary police agencies across the United States. It is important

to note that recently, there has been some debate about whether Peel really espoused the previously men-

tioned ideologies or principles or if they are the result of various interpretations (or misinterpretations) of

the history of English policing.

24

y Policing in Colonial America

Similar to England, Colonial America experienced an increase in population in major cities during the

1700s.

25

Some of these cities began to see an influx of immigrant groups moving in from various countries

(including Germany, Ireland, Italy, and several Scandinavian countries), which directly contributed to the

rapid increase in population.

26

The growth in population also created an increase in social disorder and

unrest. The sources of social tension varied across different regions of Colonial America; however, the intro-

duction of new racial and ethnic groups was identified as a common source of discord.

27

Racial and ethnic

conflict was a problem across Colonial America, including both the northern and southern regions of the

country.

28

Since the watch groups could no longer cope with this change in the social climate, more formal-

ized means of policing began to take shape. Most of the historical literature describing the early develop-

ment of policing in Colonial America focuses specifically on the northern regions of the country while

neglecting events that took place in the southern region—specifically, the creation of slave patrols in the

South.

29

Slave patrols first emerged in South Carolina in the early 1700s, but historical documents also identify

the existence of slave patrols in most other parts of the southern region (refer to the Reichel article

included at the end of this section).

30

Samuel Walker identified slave patrols as the first publicly funded

police agencies in the American South.

31

Slave patrols (or “paddyrollers”) were created to manage the race-

based conflict occurring in the southern region of Colonial America; these patrols were created with the

specific intent of maintaining control over slave populations.

32

Interestingly, slave patrols would later

extend their responsibilities to include control over White indentured servants.

33

Salley Hadden identified

three principal duties placed on slave patrols in the South during this time, including searches of slave

lodges, keeping slaves off of roadways, and disassembling meetings organized by groups of slaves.

34

Slave

Section 1 The History of the Police 5

patrols were known for their high level of brutality and ruthlessness as they maintained control over the

slave population. The members of slave patrols were usually White males (occasionally a few women) from

every echelon in the social strata, ranging from very poor individuals to plantation owners that wanted to

ensure control over their slaves.

35

Slave patrols remained in place during the Civil War and were not completely disbanded after slavery

ended.

36

During early Reconstruction, several groups merged with what was formerly known as slave

patrols to maintain control over African American citizens. Groups such as the federal military, the state

militia, and the Ku Klux Klan took over the responsibilities of earlier slave patrols and were known to be

even more violent than their predecessors.

37

Over time, these groups began to resemble and operate similar

to some of the newly established police departments in the United States. In fact, David Barlow and Melissa

Barlow noted that “by 1837, the Charleston Police Department had 100 officers and the primary function

of this organization was slave patrol . . . these officers regulated the movements of slaves and free blacks,

checking documents, enforcing slave codes, guarding against slave revolts and catching runaway slaves.”

38

Scholars and historians assert that the transition from slave patrols to publicly funded police agencies was

seamless in the southern region of the United States.

39

While some regard slave patrol as the first formal attempt at policing in America, others identify

the unification of police departments in several major cities in the early to mid-1800s as the beginning

point in the development of modern policing in the United States.

40

For example, the New York City

Police Department was unified in 1845,

41

the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department in 1846,

42

the

Chicago Police Department in 1854,

43

and the Los Angeles Police Department in 1869,

44

to name a few.

These newly created police agencies adopted three distinct characteristics from their English counter-

parts: (1) limited police authority—the powers of the police are defined by law; (2) local control—local

governments bear the responsibility for providing police service; and (3) fragmented law enforcement

authority—several agencies within a defined area share the responsibility for providing police services,

which ultimately leads to problems with communication, cooperation, and control among these agen-

cies.

45

It is important to point out that these characteristics are still present in modern American police

agencies.

Other issues that caused debate within the newly created

American police departments at this time included whether

police officers should be armed and wear uniforms and to what

extent physical force should be used during interactions with

citizens.

46

Sir Robert Peel’s position on these matters was clear

when he formed the London Metropolitan Police Department.

He wanted his officers to wear distinguishable uniforms so that

citizens could easily identify them. He did not want his officers

armed, and he hired and trained his officers in a way that would

allow them to use the appropriate type of response and force

when interacting with citizens.

47

American police officers felt

that the uniforms would make them the target of mockery

(resulting in less legitimacy with citizens) and that the level of

violence occurring in the United States at that time warranted

them carrying firearms and using force whenever necessary.

48

Despite their objections, police officers in cities were required

to wear uniforms, and shortly after that, they were allowed to

Urban police officers, 1890

6 PART I OVERVIEW OF THE POLICE IN THE UNITED STATES

carry clubs and revolvers in the mid-1800s.

49

In contemporary American police agencies, the dispute con-

cerning uniforms and firearms has long been resolved; however, the use of force by the police is still an issue

that incites debate in police agencies today.

y Policing in the United States, 1800–1970

One way to understand the history of American policing beginning in the 19th century through the 21st

century is to dissect it into a series of eras. Depending on which resource you choose, the number and

names of those eras will slightly vary; however, there is a general agreement on the influential people and

important events that took place over the course of the history of American policing. The article written by

George Kelling and Mark Moore included at the end of this section provides three eras as the framework for

an interesting and thorough discussion of the history and progression of policing in the United States. The

remainder of this section will continue to identify important people and events that have shaped and influ-

enced policing up through 1970.

Politics and the Police in America

(1800s–1900s)

A distinct characteristic of policing in the United

States during the 1800s is the direct and powerful

involvement of politics. During this time, policing was

heavily entrenched in local politics. The relationship

between the police and local politicians was reciprocal

in nature: politicians hired and retained police officers

as a means to maintain their political power, and in

return for employment, police officers would help

politicians stay in office by encouraging citizens to

vote for them.

50

The relationship was so close between

politicians and the police that it was common practice

to change the entire personnel of the police depart-

ment when there were changes to the local political

administration.

51

Politicians were able to maintain their control

over police agencies, as they had a direct hand in

choosing the police chiefs that would run the agen-

cies. The appointment to the position of police chief

came with a price. By accepting the position, police

chiefs had little control over decision making that

would impact their employees and agencies.

52

Many police chiefs did not accept the strong political pres-

ence in their agencies, and as a result, the turnover rate for chiefs of police at this time was very high. For

example, “Cincinnati went through seven chiefs between 1878 and 1886; Buffalo (NY) tried eight between

1879 and 1894; Chicago saw nine come and go between 1879 and 1897; and Los Angeles changed heads

thirteen times between 1879 and 1889.”

53

Politics also heavily influenced the hiring and promotion of

patrol officers. In order to secure a position as a patrol officer in New York City, the going rate was $300,

Police officers were viewed as an extension of politicians—1916.

Section 1 The History of the Police 7

while officers in San Francisco were required to pay $400.

54

In regard to promoted positions, the going rate

in New York City for a sergeant’s position was $1,600, and it was $12,000 to $15,000 for a position as cap-

tain.

55

Upon being hired, policemen were also expected to contribute a portion of their salary to support

the dominant political party.

56

Political bosses had control over nearly every position within police agen-

cies during this era.

Due to the extreme political influence during this time, there were virtually no standards for hiring or

training police officers.

57

Essentially, politicians within each ward would hire men that would agree to help

them stay in office and not consider whether they were the most qualified people for the job. August Vollmer

bluntly described the lack of standards during this era:

Under the old system, police officials were appointed through political affiliations and because of

this they were frequently unintelligent and untrained, they were distributed through the area to be

policed according to a hit-or-miss system and without adequate means of communication; they

had little or no record keeping system; their investigation methods were obsolete, and they had no

conception of the preventive possibilities of the service.

58

Mark Haller described the lack of training another way:

New policemen heard a brief speech from a high-ranking officer, received a hickory club, a whistle,

and a key to the callbox, and were sent out on the street to work with an experienced officer. Not

only were the policemen untrained in law, but they operated within a criminal justice system that

generally placed little emphasis upon legal procedure.

59

Police services provided to citizens included a variety of tasks related to health, social welfare, and law

enforcement. Robert Fogelson described police duties during this time as “officers cleaning streets . . .

inspecting boilers . . . distributed supplies to the poor . . . accommodated the homeless . . . investigated veg-

etable markets . . . operated emergency vehicles and attempted to curb crime.”

60

All of these activities were

conducted under the guise that it would keep the citizens (or voters) happy, which in turn would help keep

the political ward boss in office. This was a way to ensure job security for police officers, as they would likely

lose their jobs if their ward boss was voted out of office. In other cities across the United States, police offi-

cers provided limited services to citizens. Police officers spent time in local saloons, bowling alleys, restau-

rants, barbershops, and other business establishments during their shifts. They would spend most of their

time eating, drinking, and socializing with business owners when they were supposed to be patrolling the

streets.

61

There was also limited supervision over patrol officers during this time. Accountability existed only to

the political leaders that had helped the officers acquire their jobs.

62

In an essay, August Vollmer described

the limited supervision over patrol officers during earlier times:

A patrol sergeant escorted him to his post, and at hourly intervals contacted him by means of

voice, baton, or whistle. The sergeant tapped his baton on the sidewalk, or blew a signal with his

whistle, and the patrolman was obliged to respond, thus indicating his position on the post.

63

Sometime in the mid- to late 1800s, call boxes containing telephone lines linked directly to police

headquarters were implemented to help facilitate better communication between patrol officers, police

8 PART I OVERVIEW OF THE POLICE IN THE UNITED STATES

supervisors, and central headquarters.

64

The lack of police supervi-

sion coupled with political control of patrol officers opened the door

for police misconduct and corruption.

65

Incidents of police corruption and misconduct were common

during this era of policing. Corrupt activities were often related to

politics, including the rigging of elections and persuading people to

vote a certain way, as well as misconduct stemming from abuse of

authority and misuse of force by officers.

66

Police officers would use

violence as an accepted practice when they believed that citizens

were acting in an unlawful manner. Policemen would physically

discipline juveniles, as they believed that it provided more of a

deterrent effect than arrest or incarceration. Violence would also be

applied to alleged perpetrators in order to extract information from

them or coerce confessions out of them (this was referred to as the

third degree). Violence was also believed to be justified in instances

in which officers felt that they were being disrespected by citizens.

It was acceptable to dole out “street justice” if citizens were noncom-

pliant to officers’ demands or requests. If citizens had a complaint

regarding the actions of police officers, they had very little recourse,

as police supervisors and local courts would usually side with

police officers.

One of the first groups appointed to examine complaints of

police corruption was the Lexow Commission.

67

After issuing 3,000

subpoenas and hearing testimony from 700 witnesses (which pro-

duced more than 10,000 pages of testimony), the report from the

Lexow investigation revealed four main conclusions:

68

First, the police did not act as “guardians of the public

peace” at the election polls; instead they acted as “agents of Tammany Hall.” Second, instead of suppressing

vice activities such as gambling and prostitution, officers allowed these activities to occur with the condition

that they receive a cut of the profits. Third, detectives only looked for stolen property if they would be given a

reward for doing so. And finally, there was evidence that the police often harassed law-abiding citizens and

individuals with less power in the community instead of providing police services to them. After the Lexow

investigation ended, several officers were fired and, in some cases, convicted of criminal offenses. Sometime

later, the courts reversed these decisions, allowing the officers to be rehired.

69

These actions by the courts

demonstrate the strength of political influence in American policing during this time period.

Policing Reform in the United States (1900s–1970s)

Political involvement in American policing was viewed as a problem by both the public and police reformers

in the mid- to late 19th century. Early attempts (in the 19th century) at police reform in the United States

were unsuccessful, as citizens tried to pressure police agencies to make changes.

70

Later on in the early 20th

century (with help from the Progressives), reform efforts began to take hold and made significant changes

to policing in the United States.

71

A goal of police reform included the removal of politics from American policing. This effort included

the creation of standards for recruiting and hiring police officers and administrators instead of allowing

Call boxes were the most common form of

communication used by police officers during the

political era.

Section 1 The History of the Police 9

politicians to appoint these individuals to help them carry out their political agendas. Another goal of police

reform during the early 1900s was to professionalize the police. This could be achieved by setting standards

for the quality of police officers hired, implementing better police training, and adopting various types of

technology to aid police officers in their daily operations (including motorized patrol and the use of two-

way radios).

72

The professionalization movement of the police in America resulted in police agencies

becoming centralized bureaucracies focused primarily on crime control.

73

The importance of the role of

“crime fighter” was highlighted in the Wickersham Commission report (1931), which examined rising

crime rates in the United States and the inability of the police to manage this problem. It was proposed in

this report that police officers could more effectively deal with rising crime by focusing their police duties

primarily on crime control instead of the social services that they had once provided in the political era.

74

In an article published in 1933, August Vollmer outlined some of the significant changes that he

believed had taken place in American policing from 1900 to 1930. The use of the civil service system in the

hiring and promotion of police officers was one way to help remove politics from policing and to set stan-

dards for police recruits. The implementation of effective police training programs was also an important

change during this time. The ability of police administrators to strategically distribute police force accord-

ing to the needs of each area or neighborhood was another change made to move toward a professional

model of policing. There was also an improved means of communication at this time, which included the

adoption of two-way radio systems. Many agencies also began to adopt more reliable record-keeping sys-

tems, improved methods for identifying criminals (including the use of fingerprinting systems), and more

advanced technologies used in criminal investigations (such as lie detectors and science-based crime labs).

Despite the heavy emphasis on crime control that began to emerge in the mid-1930s, some agencies began

to use crime-prevention techniques. And finally, this era saw the emergence of state highway police to aid in

the control of traffic, which had increased after the automobile was introduced in the United States.

75

Vollmer stated that all of these changes contributed to

the professionalization of the police in America.

O. W. Wilson was the protégé of August Vollmer.

His work essentially picked up where Vollmer’s left off

in the late 1930s. He started out as police chief in

Wichita, Kansas, and then moved on to establish the

School of Criminology at the University of California.

76

Wilson’s greatest contribution to American policing

lies within police administration. Specifically, his

vision involved the centralization of police agencies;

this includes both organizational structure and man-

agement of personnel.

77

Wilson is also credited with

creating a strategy for distributing patrol officers

within a community based on reported crimes and

calls for service. His book, Police Administration, pub-

lished in 1950, became the “bible of police manage-

ment” and ultimately defined how professional police

agencies would be managed for many decades that

followed.

78

It is clear that the work of Vollmer and Wilson

helped American policing advance beyond that of the

Radar “speed reader” in patrol car—1954

10 PART I OVERVIEW OF THE POLICE IN THE UNITED STATES

political era; however, Harlan Haun and Judson

Jeffries argue that police reforms of the 1950s

and 1960s neglected the relationship between the

police and the public.

79

The relationship deterio-

rated between the two groups because the citi-

zens called for police services that were mostly

noncriminal in nature, and the police responded

with a heavy emphasis on crime control.

80

The

distance between these two groups would

become even greater as the social climate began

to change in the United States.

The 1950s marked the beginning of a social

movement that would bring race relations to the

attention of all Americans. Several events involv-

ing African American citizens ignited a series of

civil rights marches and demonstrations across

the country in the mid-1950s. For example, in

December 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested after

she violated a segregation ordinance by refusing

to move to the back of the bus. Her arrest trig-

gered what is now referred to as the Montgomery

bus boycott.

81

African American citizens car-

pooled instead of using the city bus system to

protest segregation ordinances. Local police

began to ticket Black motorists at an increasing

pace to retaliate against the boycott. In one

instance, Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested for

driving 5 miles per hour over the posted speed

limit.

82

Arrests were made at any type of sit-in or

protest, whether they were peaceful or not.

Research focused on the precipitants and under-

lying conditions that contributed to race riots

during this time period identified police pres-

ence and police actions as the major conditions

that were present prior to most of the race riots in the 1950s and 1960s.

83

In addition, the President’s Com-

mission on Civil Disorder (also known as the Kerner Commission) reported that “almost invariably the

incident that ignites disorder arises from police action.”

84

Social disorder resulting from protests, marches, and rioting in the 1960s resulted in frequent

physical clashes between the police and the public. It was during this time that people across the United

States began to see photographs in newspapers and news reports on television that featured incidents of

violence between these two groups. The level of violence and force being used by police officers was

shocking to some citizens, as they had not been exposed to it through visual news media in the past. One

of the most recognized examples of this type of violence was the clash between police and protesters at

the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August of 1968.

85

Graphic photos of the police hitting,

Police officers focused on order maintenance during war protests—1969.

Police reform resulted in police officers shifting their focus to crime

control—1960.

Section 1 The History of the Police 11

pushing, and arresting protesters were featured on the national news and in many national printed pub-

lications. These types of incidents contributed to the public-relations problem experienced by American

police during the 1960s.

Any police reform efforts taking place in the 1960s were based heavily on a traditional model of polic-

ing. Traditional policing focuses on responding to calls for service and managing crimes in a reactive man-

ner.

86

This approach to policing focuses on serious crime as opposed to issues related to social disorder and

citizens’ quality of life. The traditional policing model places great importance on the number of arrests

police officers make or how fast officers can respond to citizens’ calls for service.

87

In addition, this policing

strategy does not involve a cooperative effort between the police and citizens. Richard Adams and his col-

leagues described it best when they stated that “traditional policing tends to stress the role of police officers

in controlling crime and views citizens’ role in the apprehension of criminals as minor players at best and

as part of the problem at worst.”

88

The use of traditional policing practices coupled with the social unrest

that was taking place during the 1960s contributed to the gulf that was widening between the police and

citizens.

SUMMARY

• American policing was influenced by Sir Robert Peel and the London Metropolitan Police.

• Policing in Colonial America consisted of voluntary watch groups formed by citizens; these groups were

unorganized and considered ineffective.

• Slaves patrols in the southern region of the United States were used to control slave populations and have been

identified by some scholars and historians as the first formal police agencies in this country.

• Politics played a major role in American policing in the 1800s. Political involvement was believed to be at the

core of police corruption present in the agencies at that time.

• Police reform was geared toward making the police more “professional.”

call box

frankpledge system

London Metropolitan Police

political era

reform era

Sir Robert Peel

slave patrols

third degree

tything

KEY TERMS

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Why is Sir Robert Peel important to the development of policing in the United States?

2. Describe some of the duties associated with the early watch groups in the United States in the mid-19th century.

12 PART I OVERVIEW OF THE POLICE IN THE UNITED STATES

3. Identify several principles espoused by Sir Robert Peel as he began to assemble the London Metropolitan

Police Department.

4. What was O. W. Wilson’s main contribution to American policing?

5. Explain how the traditional model of policing contributed to the deterioration of the relationship between

police and citizens in the United States during the 1960s.

WEB RESOURCES

• To learn more about Sir Robert Peel, go to http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/peel_sir_robert

.shtml.

• To learn about some important dates in the history of American law enforcement, go to http://www.nleomf

.org/facts/enforcement/impdates.html.

• To learn more about the history of police technology, go to http://www.police-technology.net/id59.html.

How to Read a Research Article 13

Y

ou will likely hear your instructor say, “According to the research . . . ” or “The research tells us . . . ”

several times during class when he or she is presenting material from this book. All of the informa-

tion contained in the authored sections of this text/reader is based on research. In addition, the

journal articles included at the end of every section feature studies conducted by researchers. You might be

asking yourself, “How do I read a journal article?” The following pages provide a brief description of the

information that is typically included in peer-reviewed journal articles. I also provide a set of questions that

you should be able to answer after you have finished reading a journal article. This information is intended

to help you navigate your way through the journal articles included at the end of each section in this book.

Most research articles that are published in peer-reviewed, academic journals will have the following

components: (1) introduction, (2) literature review, (3) methodology, (4) findings/results, and (5) discus-

sion/conclusion section. It is important to note that the components found within journal articles will vary.

Some journal articles may not contain all of the traditional components. In fact, some articles that outline

the tenets of a proposed theory will not have any of the main components. This type of article is purely

descriptive. The articles included at the end of the first section of this text/reader fall into the descriptive

category. There are some articles in which the components are not clearly identified by the traditional sub-

headings (as they may use alternative subheading titles) but are discussed within the text of the article. In

most cases, however, the five traditional components will be easy to identify if the author of the article has

included them.

y Introduction

Journal articles usually begin with an introduction section. The introduction identifies the purpose of the

study. The introduction usually provides a broader context for the research questions or hypotheses being

tested in the study. The reasons the study is important are also usually included in the introduction of a

journal article.

y Literature Review

Most journal articles provide an overview of the published literature related to the topic of the study. Some

authors prefer to combine the literature review with the introduction section. The purpose of the literature

review is to present studies that have already been conducted on the research topic featured in the journal

article. By reviewing the literature, authors can highlight how their research will contribute to the existing

body of research or explain how their study is unique when compared to previous studies.

y Methodology

The methodology section describes how the study was conducted. This section usually includes informa-

tion about who or what was studied, the research site(s), the type of data collected for the study, how long

How to Read a Research Article

14 PART I OVERVIEW OF THE POLICE IN THE UNITED STATES

the study lasted, and how the data were analyzed by the researcher(s). The reader will usually be able to

determine whether the study is quantitative, qualitative, or a combination of both after reading this section.

The information included in this section should include enough detail so that the reader can understand

exactly how the study was conducted. In addition, the high level of detail in this section allows other

researchers to replicate the study in other research sites if they choose to do so.

y Findings/Results

The findings/results section explains what the researcher found when he or she analyzed the data. Research

findings are expressed using numbers in a series of tables if the research is quantitative in nature. If the

study utilized qualitative data, the research findings will consist of descriptions of patterns and themes that

were discovered within the textual data. This section is important because the research findings tell the

reader about the outcome of the study.

y Discussion/Conclusion

The discussion/conclusion section usually provides a brief recap of the purpose of the study and a general

description of the main research findings. This part of the journal article explains why the research findings

are important or what policy implications result from the research findings. This is also the point in the

article at which the author points out the limitations of the study. And finally, this section usually contains

several suggestions for future research on the topic featured in the study.

Now that you have an understanding of the parts of a journal article, I will use the article written by

Weisheit, Wells, and Falcone in Section 3 of this text to demonstrate how you can apply the five components

we just discussed above.

y Community Policing in Small Town and Rural America

By Ralph A. Weisheit, L. Edward Wells, and David N. Falcone

1. What is the purpose of the study in this article?

The purpose of the study is mentioned at the end of the third paragraph of the paper—“This

article examines the idea of community policing by considering the fit between the police practices

in rural areas and the philosophy of community policing as an urban phenomenon.” The authors

also hypothesize that “. . . experiences in rural areas provide examples of successful community

policing” and that their comparison “raises questions about the simple applicability of these ideas

to urban settings.”

2. Do the authors present any literature that is directly or indirectly related to their study?

Yes. The authors begin with a section that discusses what community policing is so that the reader

is familiar with this topic. Next, under the subheading “Existing Evidence,” the authors state,

“Although there have been no studies that directly examine the extent to which rural policing

reflects many key elements of community policing, there are many scattered pieces of evidence with

which one can make this case.” In the paragraphs that follow, they present evidence from past stud-

ies that supports the idea that they hypothesized in the beginning of the paper.

How to Read a Research Article 15

3. How was the study conducted? Specifically, how do the authors describe their research

design/methodology and data analysis?

Under the subheading “The Study,” the authors describe the methodology/research design. They

mention that the article is based on interviews that were conducted as part of a larger research

project. Unstructured interviews were conducted with 46 rural sheriffs and 28 police chiefs in small

towns. Some of the interviews were conducted face to face, while others were conducted over the

telephone. The length of the interviews ranged from 20 minutes to 2 hours; the average interview

lasted 40 minutes. The authors describe some of the questions covered during the interviews. The

authors do not specifically explain how they analyzed the interview data; however, it appears as

though they looked for themes in the interview data and compared them to findings from previous

studies on community policing. This is a qualitative, exploratory study in which the authors are

laying the groundwork for future studies on this topic. It is exploratory because no other studies

have been conducted on this specific topic.

4. What are the main research findings?

After examining the interview data, the authors found several ways that rural policing mirrors com-

munity policing (the findings section begins under the heading “Observations”). First, they identify

“community connections” as one of the ways that rural policing mirrors community policing. They

describe how the two are similar and then provide quotes from the interview data to support this

finding. They also identify “general problem solving” and “effectiveness” as two other similarities

between rural policing and community policing. The authors then make a comparison between rural

and urban policing when they interviewed chiefs of police and sheriffs that previously worked in an

urban setting. The individuals with work experience in both settings reported a difference in the way

they policed in both settings (once again this is supported by quotes from the interview data).

5. What does the article include in the conclusion/discussion section?

Under the subheading “Discussion,” the authors provide a brief and general overview of the find-

ings. They also provide further evidence of similarities between rural policing and community

policing through the use of additional quotes. They conclude the article by stating that a more

extensive study on rural policing is needed in order to state conclusively that rural policing and

community policing are similar in operation and outcomes. The authors do not point out the limita-

tions of their study in the conclusion section; instead, they state that this is an exploratory study that

is only a portion of a larger study with a different focus.

As you work your way through this text/reader, you will notice how the journal articles included at the

end of each section vary in their organization and presentation of content. If you do not find all (or any) of

the five main components in some of the articles, keep in mind that the purpose of the article may not be

to present a research study. Several of the articles are descriptive in nature: they present ideas about various

topics in policing. Regardless of the format or presentation of information, the articles will provide valuable

information that will help you further understand policing in the United States.

16 SECTION 1 THE HISTORY OF THE POLICE

READING 1

In this article, Philip Reichel provides a comprehensive overview of slave patrols of the South. Slave patrols

consisted of mostly White citizens who monitored the activities of slaves. Reichel asserts that modern policing

has passed through various developmental stages that can be explained by typologies (i.e., informal, transi-

tional, and modern types of policing).

Southern Slave Patrols as a

Transitional Police Type

Philip L. Reichel

A

ccounts of the developmental history of Amer-

ican policing have tended to concentrate on

happenings in the urban North. While the lit-

erature is replete with accounts of the growth of law

enforcement in places like Boston (Lane, 1967; Savage,

1865), Chicago (Flinn, 1975), Detroit (Schneider, 1980)

and New York City (Richardson, 1970), there has been

minimal attention paid to police development outside

the North. It seems unlikely that other regions of the

country simply mimicked that development regardless

of their own peculiar social, economic, political, and

geographical aspects. In fact, Samuel Walker (1980) has

briefly noted that eighteenth and nineteenth century

Southern cities had developed elaborate police patrol

systems in an effort to control the slave population.

Walker even suggested these slave patrols were precur-

sors to the police (1980: 59). As a forerunner to the

police, it would seem that slave patrols should have

become a well researched example in our attempt to

better understand the development of American law

enforcement. However, the regionalism of many exist-

ing histories has meant that criminal justicians and

practitioners are often unaware of the existence of, and

the role played by, Southern slave patrols. This means

our knowledge of the history of policing is incomplete

and regionally biased. This article responds to that

problem by focusing attention on the development of

law enforcement in the Southern slave states (i.e., Ala-

bama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Car-

olina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia)

during the colonial and antebellum years. The particu-

lar question to be answered is: were Southern slave

patrols precursors to modern policing?

Answering the research question requires clarifi-

cation of the term precursor. The concept of a precur-

sor to police implies there are stages of development

preceding the point at which a modern police force is

achieved. Several authors have looked at specific

factors which influenced the development of police

organizations in particular cities. Fewer have tried to

make generalizations about police growth across the

society. The latter group, which includes Bacon (1939),

Lundman (1980) and Monkkonen (1981), draw on

case studies of certain cities to hypothesize a develop-

mental sequence explaining modernization of police

Author’s Note: Historian Gail Rowe and two anonymous American Journal of Police referees provided me with invaluable assistance and suggestions for which I

am most grateful. This is an extensively revised version of a paper presented at the 1985 Annual Meeting of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences.

READING 1 Southern Slave Patrols as a Transitional Police Type 17

in America. Lundman (1980), however, presents his

ideas with the help of a typology of police systems.

1

The advantage of a historical typology is that it allows

conceptualization of a developmental sequence and

can therefore be most helpful in determining whether

or not slave patrols can be viewed as a part of that

sequence.

y The Stages of Police

Development

Lundman (1980) has suggested three types or systems

of policing: informal, transitional, and modern. Infor-

mal policing is characterized by community members

sharing responsibility for maintaining order. Such a

system was typical of societies with little division of

labor and a great deal of homogeneity. There existed

among the people, a “collective conscience” which

allowed them willingly to participate in the identifica-

tion and apprehension of rule violators. As society

grew, people had wider-ranging jobs and interests.

Agreement as to what was right and wrong became less

complete and informal police systems became less

effective. Society’s response was the development of

transitional policing which served as a bridge between

the informal and modern types. In that capacity, the

transitional systems included aspects of the informal

networks but also anticipated modern policing in

terms of offices and procedures.

Identification of the point at which a police

department becomes modern has not been agreed

upon. Bacon, for example, cited six factors to be met:

1) city-wide jurisdiction; 2) twenty-four-hour respon-

sibility; 3) a single organization in charge of the

greater part of formal enforcement; 4) a paid person-

nel on a salary basis; 5) a personnel occupied solely

with police duties, and 6) general rather than specific

functions (1939: 6). At the other extreme is Monk-

konen’s (1981) suggestion that the decisive movement

to a modern police department occurs when the police

adopt a uniform. Lundman follows Bacon but identi-

fies only four distinctive characteristics of modern

policing (1980: 17). First, there are persons recognized

as having full-time police responsibilities. Also, there

is 2) continuity in office as well as 3) continuity in

procedure. Finally, for a system to be considered mod-

ern it must have 4) accountability to a central govern-

mental authority.

Those four characteristics incorporate most of

Bacon’s suggestions but ignore Monkkonen’s. Walker,

however, found the use of uniforms as a starting point

for modern policing to be “utter nonsense” (1982: 216),

since the development process was not the same in

every city and the new agencies varied so much in size

and strength.

2

Instead, Lundman’s characteristics seem

appropriately chosen for present needs to identify the

modern police type.

Existing histories of law enforcement provide

significant information about informal (e.g. consta-

bles, day and night watches) and modern (e.g. London,

New York City, Boston) types, but tend to ignore

examples of what Lundman might call transitional.

The implication is that modern policing was the result

of simple formalization of informal systems. This

article offers Southern slave patrols as an example of

policing which went beyond informal but was not yet

modern. Because few people are aware of them, the

patrols will be described before being linked to transi-

tional police types.

y A Description of

Southern Slave Patrols

A number of variables influence the development of

formal mechanisms of social control. Lundman’s review

of the literature (1980: 24) identified four important

factors: 1) an actual or perceived increase in crime; 2)

public riots; 3) public intoxication; and 4) a need

1

Lundman’s typology of police systems is not to be confused with other typologies (e.g., Wilson’s 1968 policing styles) which differentiate contemporary as

opposed to the historical types Lundman addresses.

2

Monkkonen’s reasons for using uniforms as the starting date can be found in his book (1981: 39–45, 53) and in an article (1982: 577).

18 SECTION 1 THE HISTORY OF THE POLICE

to control the “dangerous classes.” Bacon (1939) in a

comprehensive yet infrequently cited work, took a

somewhat different approach. He identified three

factors of social change influencing development of

modern police departments: 1) increased economic

specialization; 2) formation and increasing stratifica-

tion of classes; and 3) increase in population size. As a

result of these social changes Bacon argues there comes

“an increase in fraud, in public disorders, and in legis-

lation limiting personal freedom” which pre-existing

forms of maintaining order (e.g. family, church, neigh-

borhood) are unable to handle (1939: 782). Variations

in enforcement procedures then occur which are

“pointed at specific groups, economic specialists, and

certain times, places, and objects” until eventually there

is a “tendency for specialists to become unified and

organized” (Bacon, 1939: 782–783).

Given the scholarly works identifying such numer-

ous and intertwined variables affecting the develop-

ment of police agencies, it is potentially misleading to

concentrate on just one of those factors. However, his-

torical accounts of social control techniques in the

South seem to suggest that a concern with class strati-

fication (Lundman’s fourth factor and Bacon’s second)

played a primary role in the development of formal

systems of control in that region. Although the conflicts

presented by immigrants and the poor have been

shown to be important in the development of police in

London, New York, and Boston (Lundman, 1980: 29),

the conflicts presented by slaves have received very lit-

tle attention. Bacon compared slaves to Southern whites

and found the folkways and mores of the two castes

were so different that “continual and obvious force was

required if society were to be maintained” (1939: 772).

The continual and obvious force developed by the

South to control its version of the “dangerous classes”

was the slave patrol. Before discussing those patrols it is

necessary to understand why the slaves constituted a

threat.

3

Slaves as a Dangerous Class

The portrayal of slaves as docile, happy, and generally

content with their bondage has been successfully

challenged in recent decades. We can today express

amazement that slaveowners could have been unaware

of their slaves’ unhappiness, yet some whites were

continually surprised that slaves resisted their status.

Such an attitude was not found only among Southern

slaveowners. In a 1731 advertisement for a fugitive

slave, a New England master was dismayed that this

slave had run away “without the least provocation”

(quoted in Foner, 1975: 264). Whether provoked in the

eyes of slaveholders or not, slaves did resist their

bondage. That resistance generally took one of three

forms: running away, criminal acts and conspiracies

or revolts. Any of those actions constituted a danger

to whites.

The number of slaves who ran away is difficult to

determine (Foner, 1975: 264). However, it was certainly

one of the greatest problems of slave government (Pat-

erson, 1968: 20). Resistance by running away was easier

for younger, English-speaking, skilled slaves, but

records indicate slaves of all ages and abilities had

attempted escape in this manner (Foner, 1975: 260).

Criminal acts by slaves have also been linked to resis-

tance. Foner (1975: 265–268) notes instances of theft,

robbery, crop destruction, arson and poison as being

typical. Georgia legislation in 1770 which provided the

death penalty for slaves found guilty of even attempting

to poison whites was said to be necessary because “the

detestable crime of poisoning hath frequently been

committed by slaves.” A 1761 issue of the Charleston

Gazette complained “the Negroes have again begun the

hellish practice of poisoning” (both quoted in Foner,

1975: 267).

Possibly the most fear-invoking resistance how-

ever, were the slave conspiracies and revolts: Such

action occurred as early as 1657, but the largest slave

3

Some may find the explanation of slaves as a danger to be an exercise in the obvious, but Walker’s (1982) comments provide a guiding principle. He suggests

that “constructing a thesis around presumed existence of a dangerous class is…a sloppy bit of historical writing” unless we are told who composed the group,

where they stood in the social structure and in what respect they are a danger (Walker, 1982: 215). While the “who” (slaves) and “where” (at the very bottom)

questions have been addressed above and countless other places, the “what” question is less understood.

READING 1 Southern Slave Patrols as a Transitional Police Type 19

uprising in colonial America took place on September

9, 1739 near the Stono River several miles from Charles-

ton. Forty Negroes and twenty whites were killed and

the resulting uproar had important impact on slave

regulations. For example, South Carolina patrol legisla-

tion in 1740, noted:

Foreasmuch as many late horrible and bar-

barous massacres have been actually com-

mitted and many more designed, on the

white inhabitants of this Province, by negro

slaves, who are generally prone to such cruel

practices, which makes it highly necessary

that constant patrols should be established

(Cooper, 1938b: 568).

Neighboring Georgians were also concerned

with the actuality and potential for slave revolts. The

preamble of their 1757 law establishing and regulating

slave patrols argues:

it is absolutely necessary for the Security of

his Majesty’s Subjects in this Province, that

Patrols should be established under proper

Regulations in the settled parts thereof, for

the better keeping of Negroes and other Slaves

in Order and prevention of any Cabals, Insur-

rections or other Irregularities amongst them

(Candler, 1910: 225).

Each of the three areas of resistance aided in slaves

being perceived as a dangerous class. There was, how-

ever, another variable with overriding influence. Unlike

the other three factors, this aspect was less direct and

less visible. That latent variable was the number of

slaves in the total population of several colonies. While

Table 1 Colonial, Populations by Race, 1680 to 1780

a

Percentages

South Carolina

b

North Carolina

c

Virginia

d

Georgia

e

White Black White Black White Black White Black

1680 83 17 96 4 96 4 - -

1700 57 43

f

94 4 87 13 - -

1720 30 70 86 14 76 24 (1715) - -

1740 33 67 79 21 68 32 (1743) 80 20 (1750)

1760 36 64 (1763) 79 21 (1764) 50 50 (1763) 63 37

1780 58 42 (1785) 67 33 (1775) 52 43 70 30 (1776)

a

The sources used to gather these are many and varied. The resulting percentages should be viewed as estimates to indicate trends rather than indication of

exact distribution. Slave free blacks and in the early years, Indian slaves, are not included under “black.”

b

1680, 1700, 1720 and 1740 from Simmons (1976: 125); 1763 and 1785 from Greene and Harrington (1966: 172–176).

c

1680, 1700, 1720 and 1740 from Simmons (1976: 125); 1764 from Foner (1975: 208); 1775 from Green and Harrington (19666: 156–160).

d

1680, 1715, 1743, 1763 and 1780 from Greene and Harrington (1966: 134–143); 1700 from Wells (1975: 161).

e

Georgia was not settled until 1733 and although they were illegally imported in the mid-1740 slaves were not legally allowed until 1750 from Wells (1975: 170);

1760 from Foner (1975: 213); 1776 from Greene and Harrington (1968: 180–183).

f

Wood (1974: 143) believes black inhabitants exceeded white inhabitants in South Carolina around 1708.

20 SECTION 1 THE HISTORY OF THE POLICE

an interest in knowing the continuous whereabouts of

slaves was present throughout the colonies, slave con-

trol by formal means (e.g., specialized legislation and

forces) was more often found in those areas where

slaves approached, or in fact were, the numerical

majority. Table 1 provides population percentages for

some of the Southern colonies/states. When consider-

ing the sheer number of persons to be controlled it is

not surprising that whites often felt vulnerable.

The Organization and Operation of

Slave Patrols

4

Consistent with the earliest enforcement techniques

identified in English and American history, the first

means of controlling slaves was informal in nature. In

1686 a South Carolina statute said anyone could appre-

hend, chastise and send home any slave found off his/

her plantation without authorization. In 1690 such

action was made everyone’s duty or be fined forty shil-

lings (Henry, 1968: 31). Enforcement of slavery by the

average citizen was not to be taken lightly. A 1705 act in

Virginia made it legal “for any person or persons what-

soever, to kill or destroy such slaves (i.e. runaways)…

without accusation or impeachment of any crime for

the same” (quoted in Foner, 1975: 195). Eventually,

however, such informal means became inadequate. As

the social changes suggested by Bacon (1939) took

place and the fear of slaves as a dangerous class height-

ened, special enforcement officers developed and pro-

vided a transition to modern police with general

enforcement powers.

In their earliest stages, slave patrols were part of

the colonial militias. Royal charters empowered gover-

nors to defend colonies and that defense took the form

of a militia for coast and frontier defense (Osgood,

1957). All able-bodied males between 16 and 60 were to

be enrolled in the militia and had to provide their

own weapons and equipment (Osgood, 1957; Shy,

1980; Simmons, 1976). Although the militias were

regionally diverse and constantly changing (Shy, 1980),

Anderson’s (1984) comments about the Massachusetts

Bay Colony militia notes an important distinction that

was reflected in other colonies. At the beginning of the

18

th

century, Massachusetts’ militia was defined not so

much as an army but “as an all-purpose military infra-

structure” (Anderson, 1984: 27) from which volunteers

were drawn for the provincial armies. This concept of

the militia as a pool from which persons could be

drawn for special duties was the basis for colonial slave

patrols.

Militias were active at different levels throughout

the colonies. New York and South Carolina militias were

required to be particularly active. New York was men-

aced by the Dutch and French-Iroquois conflicts while

South Carolina had to be defended against the Indians,

Spanish, and pirates. By the middle of the Eighteenth

century the colonies were being less threatened by

external forces and attention was being turned to inter-

nal problems. As early as 1721 South Carolina began

shifting militia duty away from external defense to

internal security. In that year, the entire militia was

made available for the surveillance of slaves (Osgood,

1974). The early South Carolina militia law had enrolled

both Whites and Blacks, and in the Yamassee war of

1715 some four hundred Negroes helped six hundred

white men defeat the Indians (Shy, 1980). Eventually,

however, South Carolinians did not dare to arm Negroes.

With the majority of the population being black (see

Table 1) and the increasing danger of slave revolts, the

South Carolina militia essentially became a “local anti-

slave police force and (was) rarely permitted to partici-

pate in military operations outside its boundaries”

(Simmons, 1976: 127).

Despite their link to militia, slave patrols were a

separate entity. Each slave state had codes of laws for

the regulation of slavery. These slave codes authorized

and outlined the duties of the slave patrols. Some towns

had their own patrols, but they were more frequent in

the rural areas. The presence of constables and a more

equal distribution of whites and blacks made the need

for the town patrols less immediate. In the rural areas,

4

Information about slave patrols is found primarily in the writings of historians as they describe aspects of the slaves’ life in the South. Data for this article were

gathered from those secondary sources but also, for South Carolina and Georgia, from some primary accounts including colonial records, Eighteenth and

Nineteenth century statutes and writings by former slaves.

READING 1 Southern Slave Patrols as a Transitional Police Type 21

however, the slaves were more easily able to participate

in “dangerous” acts. It is not surprising that the slave

patrols came to be viewed as “rural police” (cf. Henry,

1968: 42). South Carolina Governor Bull described the

role of the patrols in 1740 by writing:

The interior quiet of the Province is provided

for the small Patrols, drawn every two months

from each company, who do duty by riding

along the roads and among the Negro Houses

in small districts in every Parish once a week,

or as occasion requires (quoted in Wood,

1974: 276 note 23).

Documentation of slave patrols is found for nearly

all the Southern colonies and states

5

but South Carolina

seems to have been the oldest, most elaborate, and best

documented. That is not surprising given the impor-

tance of the militia in South Carolina and the presence

of large numbers of Blacks. Georgia’s developed some-

what later and exemplifies patrols in the late 18th and

early 19th centuries. The history and development of

slave patrol legislation in South Carolina and Georgia

provides a historical review from colonial through

antebellum times.

In 1704 the colony of Carolina

6

presented what

appears to be the South’s first patrol act. The patrol was

linked to the militia yet separate from it since patrol

duty was an excuse from militia duty. Under this act,

militia captains were to select ten men from their com-

panies to form these special patrols. The captain was to

muster all the men under his command, and

with them ride from plantation to plantation,

and into any plantation, within the limits or

precincts, as the General shall think fitt and

take up all slaves which they shall meet with-

out their master’s plantation which have not a

permit or ticket from their masters, and the

same punish (Cooper, 1837: 255).

That initial act seemed particularly concerned with

runaway slaves, while an act in 1721 suggests an

increased concern with uprisings. The act ordered the

patrols to try to “prevent all caballings amongst negroes,

by dispersing of them when drumming or playing, and

to search all negro houses for arms or other offensive

weapons” (McCord, 1841: 640). In addition to that con-

cern the new act also responded to complaints that

militia duty was being shirked by the choicest men who

were doing patrol duty instead of militia duty (Bacon,

1939; Henry, 1968; McCord, 1841; Wood, 1974). As a

result, the separate patrols were merged with the colonial

militia and patrol duty was simply rotated among differ-

ent members of the militia. From 1721 to 1734 there

really were no specific slave patrols in South Carolina.

The duty of supervising slaves was simply a militia duty.

In 1734 the Provincial Assembly set up a regular

patrol once again separate from the militia (Cooper

1838a, p. 395). “Beat companies” of five men (Captain

and four regular militia men) received compensation

(captains $50 and privates $25 per year) for patrol duty

and exemption from other militia duty. There was one

patrol for each of 33 districts in the colony. Patrols

obeyed orders from and were appointed by district

commissioners and were given elaborate search and

seizure powers as well as the right to administer up to

twenty lashes (Cooper 1838a: 395–397).

7

Since provincial acts usually expired after three

years, South Carolina’s 1734 Act was revised in 1737

5

See Resc. (1976) for Alabama; O.W. Taylor (1958) for Arkansas; Flanders (1967) for Georgia; Coleman (1940) and McDougle (1970) for Kentucky; Bacon

(1939), J.G. Taylor (1963) and Williams (1972) for Louisiana; Sydnor (1933) for Mississippi; Trexler (1969) for Missouri; Johnson (1937) for North Carolina;

Patterson (1968) and Mooney (1971) for Tennessee; and Ballagh (1968) and Stewart (1976) for Virginia.

6

In 1712 the northern two-thirds of Carolina was divided into two parts (North Carolina and South Carolina) while the southern one third remained unsettled

until 1733 when Oglethorpe founded Georgia.

7

The right to administer a punishment to slaves was given to patrols in other colonies and states as well. Patrols in North Carolina could administer fifteen

lashes (Johnson, 1937: 516) as could those in Tennessee (Patterson, 1968: 39) and Mississippi (Sydnor, 1933: 78) while Georgia (Candler, 1910: 232) and

Arkansas (O.W. Taylor, 1958: 210) followed South Carolina in allowing twenty lashes.

22 SECTION 1 THE HISTORY OF THE POLICE

and again in 1740. Under the 1737 revision, the paid

recruits were replaced with volunteers who were

encouraged to enlist by being excused from militia and

other public duty for one year and were allowed to elect

their own captain (Cooper 1838b; 456–458). The num-

ber of men on patrol was increased from five to fifteen

and they were to make weekly rounds. Henry (1968: 33)

believed these changes were an attempt to dissuade

irresponsible persons who had been attracted to patrol

duty for the pay.

The 1740 revision seems to be the first legislation

specifically including women plantation owners as

answerable for patrol service (Cooper 1838b; 569–570).

The plantation owners (male or female) could, however,

procure any white person between 16 and 60 to ride

patrol for them. In addition, the 1740 act said patrol

duty was not to be required in townships where white

inhabitants were in far superior numbers to the Negroes

(Cooper 1838b; 571). Such an exemption certainly

highlights the role of patrols as being to control what

was perceived as a dangerous class.

At this point we turn to the Georgia slave patrols as

an example of one that developed after South Carolina

set a precedent. Georgia was settled late (1733) com-

pared to the other colonies and despite her proximity to

South Carolina she did not make immediate use of

slaves. In fact while slaves were illegally imported in the

mid 1740s, they were not legally allowed until 1750.

Within seven years Georgians felt a need for control of

the slaves. Her first patrol act (1757) provided for mili-

tia captains to pick up to seven patrollers from a list of

all plantation owners (women and men) and all male

white persons in the patrol district (Candler 1910:

225–235). The patrollers or their substitutes were to

ride patrol at least once every two weeks and examine

each plantation in their district at least once every

month. The patrols were to seek out potential run-

aways, weapons, ammunition, or stolen goods.

The 1757 Act was continued in 1760 (Candler

1910: 462) for a period of five years. The 1765 continu-

ation (Cobb 1851: 965) increased the number of patrollers

to a maximum of ten, but left the duties and structure

of the patrol as it was created in 1757. In the 1768

revision (Candler 1911: 75) the possession and use of

weapons by slaves was tightened and a fine was set for

selling alcohol to slaves. More interesting was the order

relevant to Savannah only which gave patrollers the

power to apprehend and take into custody (until the

next morning) any disorderly white person (Candler

1911: 81). Should such a person be in a “Tippling House

Tavern or Punch House” rather than on the streets the

patrol bad to call a lawful constable to their assistance

before they could enter the “bar.” Such power was

extended in 1778 when patrols were obliged to “take up

all white persons who cannot give a satisfactory account

of themselves and carry them before a Justice of the

Peace to be dealt with as is directed by the Vagrant Act”

(Candler, 1911: 119).

Minor changes occurred between 1778 and 1830

(e.g. females were exempted from patrol duty in 1824)

but the first major structural change did not take place

until 1830. In that year Georgia patrols finally began

moving away from a direct militia link when Justices of

the Peace were authorized and required to appoint and

organize patrols (Cobb, 1851: 1003). In 1854 Justices of

the Interior Courts were to annually appoint three

“patrol commissioners” for each militia district (Ruth-

erford, 1854: 101). Those commissioners were to make

up the patrol list and appoint one person at least 25

years old and of good moral character to be Captain.

The absence of significant changes in Georgia

patrol legislation over the years suggests the South

Carolina experiences had provided an experimental

stage for Georgia and possibly other slave states. Dif-

ferences certainly existed, but Foner’s general descrip-

tion of slave patrols seems accurate for the majority of

colonies and states; patrols had full power and author-

ity to enter any plantation and break open Negro

houses or other places when slaves were suspected of

keeping arms; to punish runaways or slaves found

outside of their masters’ plantations without a pass; to

whip any slave who should affront or abuse them in

the execution of their duties; and to apprehend and

take any slave suspected of stealing or other criminal

offense, and bring him to the nearest magistrate

(1975: 206).

READING 1 Southern Slave Patrols as a Transitional Police Type 23

The Slaves’ Response to the Patrols

The slave patrols were both feared and resented by the

slaves.

8

Some went so far as to suggest it was “the worse

thing yet about slavery” (quoted in Blassingame, 1977:

156). Former slave Lewis Clarke was most eloquent in

expressing his disgust:

(The patrols are) the offscouring of all things;

the refuse,…the ears and tails of slavery;…

the tooth and tongues of serpents. They are

the very fool’s cap of baboons,…the wallet

and satchel of polecats, the scum of stagnant

pools, the exuvial, the worn-out skins of slave-

holders. (T)hey are the meanest, and lowest,

and worst of all creation. Like starved wharf

rats, they are out nights, creeping into slave

cabins, to see if they have an old bone there;

they drive out husbands from their own beds,

and then take their places (Clarke, 1846: 114).

Despite the harshness and immediacy of punish-