PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

Positive Emotions in Early Life and Longevity:

Findings from the Nun Study

Deborah D. Danner, David A. Snowdon, and Wallace V. Friesen

University of Kentucky

Handwritten autobiographies from 180 Catholic nuns, composed when participants were a mean age

of 22 years, were scored for emotional content and related to survival during ages 75 to 95. A strong

inverse association was found between positive emotional content in these writings and risk of mortality

in late life (p < .001). As the quartile ranking of positive emotion in early life increased, there was a

stepwise decrease in risk of mortality resulting in a 2.5-fold difference between the lowest and highest

quartiles. Positive emotional content in early-life autobiographies was strongly associated with longev-

ity 6 decades later. Underlying mechanisms of balanced emotional states are discussed.

Longevity may be related to a variety of factors including

heredity, gender, socioeconomic status, nutrition, social support,

medical care, and personality and behavioral characteristics (Rob-

ine,

Vaupel, Jeune, & Allard, 1997). These factors might operate

throughout life or at particular life stages. Recent findings from the

Nun Study, a longitudinal study of older Catholic sisters, indicated

that linguistic ability in early life is associated with survival in late

life (Snowdon, Greiner, Kemper, Nanayakkara, & Mortimer,

1999).

In that study, the idea density (proposition, information, and

content) of autobiographies written at a mean age of 22 years was

strongly related to survival and longevity 6 decades later. Because

Deborah D. Danner and David A. Snowdon, Department of Preventive

Medicine and Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, College of Medicine,

University of Kentucky; Wallace V. Friesen, Sanders-Brown Center on

Aging, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky.

David A. Snowdon is now at the Department of Neurology and the

Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, College of Medicine, University of

Kentucky.

The study was funded by National Institute on Aging Grants

R01AG09862, K04AG00553, and 5P50AG05144, and by a grant from the

Kleberg Foundation.

This study would not have been possible without the spirited support of

the members, leaders, and health care providers of the School Sisters of

Notre Dame religious congregation. Archivists at each of the main con-

vents were instrumental in the study. We also wish to recognize the help of

Lydia Greiner in the conception of the study and Mark Desrosiers for his

valuable scientific and programming assistance. Other staff members of the

Nun Study who provided invaluable assistance on this project include

Danice Creager, Gari-Anne Patzwald, Jeanne Ray, and Mary Roycraft.

More information on the Nun Study may be obtained at http://www.

nunstudy.org.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Deborah

D.

Danner, Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, University of Kentucky, 800

South Limestone, Lexington, Kentucky 40536-0230. Electronic mail may

be sent to [email protected].

the autobiographies appeared to contain emotional content that

might be associated with idea density (Snowdon et al., 1996), we

investigated the relationship between emotional content in these

early life writings and survival in late life.

A growing body of literature has shown positive and negative

emotion-related attitudes and states to be associated with physical

health, mental health, and longevity. For example, in a longitudinal

study of Harvard graduates, Peterson (Peterson, Seligman, & Vail-

lant, 1988) found the ways in which young men explained bad

events predicted health outcome decades later. Such studies appear

to be based on assumptions that emotion-based constructs reflect

patterns of coping with negative life events and stresses that can be

harmful or beneficial to health. The assumptions of the current

longitudinal investigation of emotions and longevity are very

similar and evolved from what is known about the underlying

relationships among emotion, temperament, and physiology that

might influence longevity. This study builds on the knowledge that

there are universal, patterned emotional responses that affect phys-

iology in ways that are potentially damaging or beneficial.

Over the past 30 years, emotion researchers have identified

basic emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust

(Ekman & Friesen, 1969). More recently, these basic emotions

have been associated with differentially patterned autonomic

nervous system (ANS) responses (Ekman, Levenson, & Friesen,

1983;

Levenson, Carstensen, Friesen, & Ekman, 1991; Levenson,

Ekman, & Friesen, 1990; Levenson, Ekman, Heider, & Friesen,

1992).

The functional characteristics of the associated patterns of

emotion and ANS activation (Levenson, in press) strongly suggest

the potential for a lifelong pattern of emotional arousal affecting

health and longevity. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown

that complex emotional states, such as anxiety, produce elements

of ANS patterns associated with specific negative emotions (Laza-

rus,

1991). These same elements of elevated galvanic skin re-

sponse, heart rate, and blood pressure are found in the patterned

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2001, Vol. 80, No. 5, 804-813

Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0022-35I4/01/$5.00 DO): 10.1037//0022-3514.80.5.804

804

POSITIVE EMOTIONS

IN

EARLY LIFE

805

ANS responses

to the

arousal

of

basic emotions

and

potentially

could affect health

and

longevity.

Laboratory research also

has

found that

the

suppression

of

emotional states

can

exacerbate

ANS

responses (Gross

&

Leven-

son, 1997).

A

lifelong pattern

of

suppressing

the

expression

of

emotion

has the

potential

for

adverse effects

on

essential body

systems. Although

no

ANS pattern has been found

to be

associated

with positive emotion that differentiates

it

from baseline (Leven-

son

et al.,

1990), studies have demonstrated

the

potential muting

effects

of

positive emotion

on the

bodily responses

to

negative

emotion (Fredrickson

&

Levenson, 1998). This healing effect

of

positive emotion

may

have

the

potential

to

reduce stress

on the

cardiovascular system even

in the

face

of

inevitable negative life

events.

In

other words, constructs such

as

optimism

and

positive

attitude

may

imply

the

following sequence: Events arousing

neg-

ative affect

are

approached with confidence that

the

future holds

something positive

and

better, thus internally generating

a

positive

emotional state that mutes

the

adverse effects

of the

prolonged

arousal

of a

negative emotion.

The basic research

of

Fredrickson, Gross,

and

Levenson cited

above

has

laid

the

groundwork

for the

study

of

how sustained

and

repetitious patterns

of

emotional arousal might relate

to

physical

health

and

survival

and,

more specifically,

how the

emotion

sys-

tem

is

intimately tied

to the ANS,

which activates cardiovascular

responses that could have cumulative adverse

or

salutary effects

on

health (Krantz

&

Manuck, 1984). What

is

needed

is an

explanation

for

why a

particular pattern

of

emotional

and ANS

responses

would

be

repeated with sufficient frequency

to

produce such

cumulative effects.

As

part

of

this explanation,

it is

necessary

to

examine

the

relationship among patterns

of

emotional responsive-

ness,

temperament,

and the

development

of

personality.

Temperament,

the

biologically based propensity

for

individuals

to respond

to

events

in

particular ways,

is

considered

by

some

theorists

to

contribute

to the

development

of

personality (Izard,

Libero, Putnam,

&

Haynes,

1993;

Malatesta

&

Wilson, 1988).

Moreover, temperament

is

proposed

to

reflect

the

degree

to

which

emotions

are

generally expressed,

as

well

as the

differing frequen-

cies with which specific emotions

or

patterns

of

emotions

are

displayed

or

suppressed (Izard

et al.,

1993). Early

and

continuing

styles

of

emotional expression

are

proposed

to

constitute some

characteristics

of

personality (Izard

et al., 1993;

Malatesta

&

Wilson, 1988). Supporting this line

of

reasoning, work

by

Headey

(Headey

&

Wearing,

1992)

suggests that individuals maintain

levels

of

positive

or

negative affect that

are

determined

by

their

personalities

and

that after emotional arousal

or

stress these levels

return

to

individual baselines (Diener, 2000). When

an

individual's

response pattern

is

frequent

or

sustained negative emotional

arousal with slow return

to a

tranquil baseline,

the

autonomic

response could prompt cardiovascular activity that accelerates

disease mechanisms such

as

atherosclerosis.

In

contrast,

a

pattern

of relatively infrequent negative emotional arousal

or one

that

rapidly returns

to a

calm baseline following negative arousal could

have beneficial effects

on

health.

Such

a

balance

of

emotional states, either

by

avoiding suppres-

sion

of the

expression

of

aroused emotion

or by

readily resolving

negative arousal,

is

compatible with Vaillant's proposal that

ma-

ture defenses work

to

promote

a

positive psychology that enhances

the ability

to

work, love,

and

play (Vaillant, 2000). Vaillant

provided evidence that earlier life manifestations

of

mature

ego

defenses that balance

and

attenuate multiple sources

of

conflict

predict enhanced physical

and

mental health

20

years later

and

suggests that mature

ego

defenses

may

reflect inborn traits.

If so,

Vaillant's proposition

may

offer

yet

another pathway

for how

potentially beneficial

or

harmful patterns

of

emotional responses

may

be

expressed

and

balanced

and may be

mediated through

patterns

of

problem solving throughout

a

lifetime, thereby influ-

encing longevity.

A pattern

of

emotional arousal

and

temperament

may be dis-

closed,

in

part,

by the

written expression

of

language. Research

by

Pennebaker

and his

colleagues

has

used written language

as a

means

of

understanding

how

emotion influences both physical

and

psychological health (Hughes, Uhlmann,

&

Pennebaker,

1994;

Pennebaker, 1993; Pennebaker

&

King, 1999).

The

early-life

au-

tobiographies

in our

study afford another opportunity

to

examine

emotional content

in

written language

and its

relationship

to

health.

If the use of

emotional content

in

these writings reflects

reactions

to

inevitable stressful life events, then these writings

may

reveal characteristic responses

to

intense

or

sustained arousal that

produces allostatic load—indicators

of

physiological response

to

stress (McEwen,

1998;

Singer

& Ryff, 1999;

Sterling

&

Eyer,

1988).

Furthermore,

if the use of

positive

and

negative emotional

content

in

writing reflects

a

general readiness

to

express emotion,

then these writings

may

indicate

a

pattern that avoids

the

adverse

effects

of

suppressing

the

expression

of

emotions.

On the

other

hand,

if the use of

positive emotional content

in

writing reflects

a

readiness

to

resolve negative arousal, then writings

may be

reveal-

ing

a

pattern of balance

in

emotional response indicating allostasis,

adaption

to

change while maintaining physiological systems

within

a

normal range (Singer

& Ryff, 1999;

Sterling

&

Eyer,

1988;

McEwen, 1998). Both

the

avoidance

of

suppression

and the

positive resolution

of

life's stresses could have beneficial effects

on health

and

longevity.

Seligman emphasizes that

an

insightful, positive attitude

in

dealing with life events,

an

optimistic explanatory style

in

contrast

to

a

pessimistic

one, can

lead

to

greater feelings

of

well-being

and

perhaps even

to

longer life (Seligman, 2000).

In

support,

a

recent

study found optimism,

as

measured

by a new

optimism-pessimism

scale

of the

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Swen-

son, Pearson,

&

Osborne, 1973),

was

associated with

a

lower risk

of death

in 839

Mayo Clinic patients observed over

a

30-year

period (Maruta, Colligan, Malinchoc,

&

Offord, 2000). However,

in another long-term study

of

more than

a

thousand bright Cali-

fornia school children, cheerfulness (i.e., parental judgments

of

optimism

and a

sense

of

humor)

had an

inverse relationship with

longevity during middle

and old age

(Friedman, 1999).

In the

latter

study,

the

cheerful participants also were found

to be

more likely

to engage

in

activities known

to be

risk factors

for

mortality.

On

the other hand,

in

another analysis

of

the California data, Peterson

and colleagues used

the

Content Analysis

of

Verbatim Explana-

tions technique (Peterson, Seligman, Yurko, Martin,

&

Friedman,

1998)

to

code questionnaires completed

by the

participants

in

early

adulthood

and

found evidence

of a

negative relationship between

pessimism

and

longevity.

The early-life autobiographies

and

mortality data available

for

participants

in the Nun

Study offer

a

unique opportunity

to

inves-

tigate

the

possible association

of

written emotional expression

to

longevity. Participants

in our

study

had the

same reproductive

and

marital histories,

had

similar social activities

and

support,

did not

806

DANNER, SNOWDON,

AND

FRIESEN

smoke

or

drink excessive amounts

of

alcohol,

had

similar occu-

pations

and

socioeconomic status,

and had

comparable access

to

medical care. Therefore, even though

it

may

be

difficult

to

gener-

alize from this unique population

of

Catholic sisters, many factors

that confound most studies

of

longevity have been minimized

or

eliminated.

Method

Study Population

The

Nun

Study

is a

longitudinal study

of

aging

and

Alzheimer's disease

(Snowdon, 1997; Snowdon

et

al.,

1996,

1999). Participants were members

of

the

School Sisters

of

Notre Dame religious congregation

who,

before

their retirement, lived

and

taught

in the

schools

of

cities

and

towns

in the

midwestern, eastern,

and

southern United States.

In

1991 through 1993,

all

American School Sisters

of

Notre Dame born before

1917

were asked

to

join

the Nun

Study.

Six

hundred seventy-eight women agreed

to

participate

in

all

phases

of

the study

and

gave informed written consent

to

allow access

to their archived

and

active records, participate

in

annual assessments

of

cognitive

and

physical function,

and

donate their brains

at

death.

At the

first annual exam,

the

678

participants were

75

to

102

years

old

(M

= 83).

A search

of

the

convents' archives revealed that

the

Mother Superior

of

the North American sisters,

who

resided

in

Milwaukee, Wisconsin,

had

sent

a

letter

on

September

22,

1930,

requesting that each sister write

an

autobiography.

A

mix

of

handwritten

and

typed autobiographies

for

many

of the 678 sisters

in

the

study

was

found

and

these autobiographies became

an invaluable research source. Criteria used

to

select autobiographies

for

intensive study were that

the

writers were born

and

raised

in the

United

States

and

thus

had the

opportunity

to

master

the

English language

and

that

the autobiographies were handwritten

and

therefore could

be

authenticated

as unaltered

by

clerical

staff.

We found that

the

number

of

available handwritten autobiographies

was

related

to the

convent

in

which

the

sister lived

and the

year

she

wrote

her

life story.

A

large number

of

autobiographies meeting criteria were found

for participants from

the

Milwaukee, Wisconsin,

and the

Baltimore, Mary-

land, convents

who

took their religious vows

and

formally joined

the

religious congregation during 1931

to

1943

(Snowdon

et

al.,

1999).

Of

the

678 sisters

in the Nun

Study,

218

took their vows

in

these

two

convents

during that time period

and

handwritten autobiographies were found

for

180 (83%)

of

these participants; that is,

101

participants from

the

Milwau-

kee,

Wisconsin, convent

and 79

from

the

Baltimore, Maryland, convent.

These

180

autobiographies were written some time between

the

ages

of

18

and 32 (M = 22)

depending

on the

age

at

which

the

sister joined

the

congregation.

At

the

time

of

writing

the

autobiographies, 82%

of

the sisters

had earned

a

high school diploma.

By the

beginning

of the

mortality

follow-up period

in

1991, 91%

had

earned

at

least

a

bachelors degree.

During

the

mortality follow-up period

of

November

13,

1991,

to

Septem-

ber

1,

2000,

the

participants ranged

in age

from

75 to 95

years

and 76

I

had

died (Milwaukee sample

=

43%, Baltimore sample

=

42%).

Autobiographies

Beginning

in

1930,

each sister

who

took

her

final vows

was

asked

to

write

a

short sketch

of

[her] life. This account should

not

contain more

than

two to

three hundred words

and

should

be

written

on a

single

sheet

of

paper

. . .

include place

of

birth, parentage, interesting

and

edifying events

of

childhood, schools attended, influences that

led to

the convent, religious life,

and

outstanding events.

Clearly,

the

instructions were

not

intended

to

influence

the

manner

in

which these life events were described

nor

were they intended

for

the

study

of emotional content, coping styles,

or

patterns

of

reasoning. Rather,

we

suspect that the autobiographies

may

have been used

in

part

by the

convent

leaders

to

gather information that might help

to

determine future educa-

tional

and

occupational paths,

as

well

as to

provide information useful

for

creating obituaries.

Despite uniformity

in the

events that were described,

the

manner

in

which

the

life facts were told

in the

autobiographies reflected individual

style

and

ranged from simply stating that these life events happened

and

when they occurred

to

elaborations

of the

simple facts that included

the

emotions experienced

by the

writer

or

others involved

in

the

life event.

The

following sentences, from

the

beginning

and

ending

of two

autobiogra-

phies,

demonstrate differences

in

emotional content:

Sister

1

(low positive emotion):

I

was born

on

September

26,

1909,

the

eldest

of

seven children, five girls

and two

boys

.... My

candidate

year

was

spent

in the

Motherhouse, teaching Chemistry

and

Second

Year Latin

at

Notre Dame Institute. With God's grace,

I

intend

to do

my best

for our

Order,

for

the

spread

of

religion

and for

my

personal

sanctification.

Sister

2

(high positive emotion):

God

started

my

life

off

well

by

bestowing upon

me a

grace

of

inestimable value...

. The

past year

which

I

have spent

as

a

candidate studying

at

Notre Dame College

has

been

a

very happy

one. Now I

look forward with eager

joy to

receiving

the

Holy Habit

of

Our Lady

and

to a

life

of

union with Love

Divine.

Coding the Autobiographies and Generating Scores

The coding system used

in

classifying

the

written autobiographies

was

designed specifically

for

this study (Danner, Friesen,

&

Snowdon, 2000).

All coding

and

review

of the

autobiographies were done without knowl-

edge

of

the health

or

functional status

of

the

study participants. Two coders

identified

all

words

in

thel80 autobiographies that reflected

an

emotional

experience

and

classified them

as

positive, negative,

or

neutral. Later,

a

third coder verified each coded word

for

accuracy

and

determined

the

specific type

of

emotional experience

or

state referenced

by

each word.

Coders were instructed

on the

distinctions between descriptions

of

possible elicitors

of

emotion (e.g., death

of a

family member),

the

emotion

that

was

experienced (e.g., sadness), subsequent behaviors (e.g., crying),

and attempts

to

control

the

overt expression

of the

emotion. They were

instructed

not to

code descriptions

of

possible elicitors,

but to

code only

words that

in

context described

the

emotion that

was

experienced

and

behaviors subsequent

to

emotional arousal. Further, they were instructed

not

to

code words such

as

good

and bad

that have positive

or

negative

connotations

or

might imply

an

emotional reaction

but do not

directly

describe

an

emotional experience.

The coders were provided with examples

of

words related

to the

expe-

rience

of the

positive emotions

of

accomplishment, amusement, content-

ment, gratitude, happiness, hope, interest, love,

and

relief;

the

negative

emotions

of

anger, contempt, disgust, disinterest, fear, sadness,

and

shame;

and

the

neutral emotion

of

surprise. The two coders,

one

with a background

in psychology

and the

other with training

in

education, then independently

read

the

autobiographies. They marked words that conveyed emotion

as

experienced

by the

writer

or

others

and

classified

the

valence

of the

emotional content

as

positive, negative,

or

neutral. When necessary

for

comprehension,

the

coders were instructed

to

identify

and

code phrases

rather than single words.

Two procedures were used

to

generate scores

for

the primary analysis

on

the basis

of

the

positive, negative,

and

neutral scoring.

The

first procedure

simply used

the raw

count

of

positive,

negative,

and

neutral emotion words

for each autobiography.

The

second procedure used these coded emotion

words

to

classify each sentence

as

containing

one or

more positive,

negative,

or

neutral words

or

as

containing

no

emotion words. The first

two

columns

of

Table

1

show

the

number

of

positive, negative,

and

neutral

emotional words

and

sentences

as

determined

by

each individual coder.

The table shows that

the two

coders identified very similar numbers

of

positive, negative,

and

neutral emotional words.

POSITIVE EMOTIONS

IN

EARLY LIFE

807

Table

1

Reliability

of

the Emotion Coding

as

Indicated

by the

Number

of

Emotion Words

and

Sentences

Scored

by

Two Coders

for

Autobiographies Written

in

Early Life

by 180 Participants

in the Nun

Study

Unit

of

analysis

and emotion

Words

Positive

Negative

Neutral

Sentences

Positive

Negative

Neutral

Coder

A

1,243

206

16

1,006

196

16

Count

Coder

B

1,242

192

17

1,017

179

17

Coders

A

and

B

a

.96

(.95,

.97)

.89

(.85,

.94)

.78 (.64, .93)

.97 (.96, .98)

.90

(.85,

.95)

.78 (.64, .93)

Correlation

of

counts

Final coding

and

Coder

A

.99 (.98, .99)

.97 (.94, .99)

.97 (.90,

1.00)

.99 (.98, .99)

.97 (.96, .99)

.97 (.90,

1.00)

each coder

a

Coder

B

.98 (.98, .99)

.94

(.91,

.97)

.82 (.69, .95)

.99 (.98, .99)

.94

(.91,

.97)

.82 (.69, .95)

Note.

For all

correlations,

p <

.0001.

a

95% confidence intervals appear

in

parentheses.

In

the

verification phase

of the

coding,

the

words scored

by the two

coders were extracted from

the

autobiographies

and a

nonredundant list

of

words

was

reviewed

by a

third person (Wallace

V.

Friesen)

for

accuracy.

This review

was

done without knowledge

of

whether

one or

both coders

had scored the word or how frequently the word was scored. Words that did

not meet

the

original criteria

for an

emotional experience were removed

from the list. The 1,598 words retained

in

the final scoring constituted

1.8%

of the total words

in the

autobiographies

and

95%

of

the words scored

by

one

or

both coders.

Of

these emotional words,

84%

were classified

as

positive, 14%

as

negative,

and 1% as

neutral.

As

described above

for the

single coders,

the

verified coding

of

emotion words was used

to

determine

the number

of

sentences with

one or

more positive, negative,

and

neutral

emotion words.

As

a

part

of the

verification process, each unique emotion word

was

classified

as

referring

to a

specific type

of

positive

or

negative emotions

(only one emotion, surprise,

was

scored

in the

neutral category). Initially,

the purpose

of the

categorization

was to aid in the

verification

of the

positive, negative, and neutral scoring

of

Coders

A

and B.

If a

word could

not

be

categorized,

its

validity

as an

emotion word

was

questionable.

We

carefully reviewed this categorization

of

the emotion words

and

disagree-

ments were discussed and arbitrated. The final list

of

subcategories and

the

number and percentage

of

sentences containing one

or

more words

in

each

category

is

presented

in

Table

2.

Intercoder Reliability

Two types

of

intercoder reliability were assessed:

the

overall agreement

in selecting

and

classifying the valence

of

emotional words

and the

degree

to which the coders' scoring and the verified scoring

of

the

autobiographies

were correlated. Kappa coefficients were used

to

assess overall agreement

between

the two

coders

on the

selection

and

classification

of

emotion

words. The coefficient values were .83 and .84, .85, and .79

for

all emotion,

positive, negative,

and

neutral words respectively, indicating

a

satisfactory

level

of

intercoder reliability both overall

and for the

individual types

of

emotion words. Additional analyses indicated that most differences

be-

tween

the two

coders were

due to one

coder identifying

a

word that

the

other failed to detect and that this occurred with similar frequencies

for

the

two coders. Examination

of

these disagreements indicated that

the

coder

who failed

to

code apparently simply

did not see the

word because

the

same word

was

identified

and

classified identically

by the

errant coder

in

different places

in

the autobiographies.

In

other words, had the errant coder

noticed

the

word when reading

the

autobiography,

it

almost certainly

would have been scored

in

agreement with

the

accurate coder.

In addition

to the

kappa coefficients

of

agreement, each coder's scoring

and

the

verified scoring were used

to

generate positive, negative,

and

neutral counts

for

both words

and

sentences

for

each autobiography.

Correlations were used

to

test the comparability

of

the three sets

of

coding.

The resulting correlations

are

shown

in the

three columns

on the

right

of

Table

I. It

can

be

seen here that the correlations between Coders

A and B

and verified counts

of

the numbers

of

emotional words and sentences were

very high, indicating that virtually identical results would have been

obtained

in

subsequent survival analysis had either Coder A's

or

Coder

B's

scoring been used

in

place

of the

final verified scores.

Linguistic Measures

Recent findings from studies

of

the same 180 autobiographies indicated

that linguistic ability

in

early life

was

associated with survival

in

late life

(Snowdon

et

al., 1999).

In

that study,

the

idea density (proposition, infor-

mation, and content)

of

these autobiographies was associated with survival

and longevity

6

decades later. Idea density

of

the early-life autobiographies

also

had a

strong inverse association with Alzheimer's disease (Snowdon

et al., 1996; Snowdon, Greiner,

&

Markesbery, 2000). Because idea-dense

sentences

of

the autobiographies were observed to contain emotional words

(Snowdon

et al.,

1996), idea density

and

grammatical complexity were

used

as

control variables

in one of the

analyses

in the

current study.

The

following

is a

brief description

of how

idea density

and

grammatical

complexity were measured.

Without

the

linguistic coders' knowledge

of

the

age or

cognitive func-

tion

of

each sister during late life, each autobiography

was

scored

for two

indicators

of

linguistic ability: idea density (Kintsch

&

Keenan,

1973;

Turner

&

Greene, 1977)

and

grammatical complexity (Cheung

&

Kemper,

1992).

Mean idea-density

and

grammatical-complexity scores were

com-

puted from

the

last

ten

sentences

of

each autobiography. Idea density

was

defined

as the

average number

of

ideas expressed

per ten

words. Ideas

corresponded

to

elementary propositions, typically

a

verb, adjective,

ad-

verb,

or

prepositional phrase. Complex propositions that stated

or

inferred

causal, temporal,

or

other relationships between ideas also were counted.

Grammatical complexity

was

computed using

the

Developmental Level

metric originally developed

by

Rosenberg

and

Abbeduto (Rosenberg

&

Abbeduto,

1987) and

modified

by

Cheung

and

Kemper (1992).

The De-

velopmental Level metric classifies sentences according

to

eight levels

of

808

DANNER, SNOWDON, AND FRIESEN

Table 2

Distribution of the Different Types of Emotion Sentences in the

Autobiographies Written in Early Life by 180 Participants

in the Nun Study

Type of emotion

Positive

Happiness

Interest

Love

Hope

Gratefulness

Contentment

Unspecified

Accomplishment

Relief

Amusement

Negative

Unspecified

Sadness

Afraid

Disinterest

Confused

Anxiety

Suffering

Shame

Hopelessness

Frustration

Disgust

Anger

Contempt

Neutral

Surprise

No.

Milwaukee

convent

109(6.10)

160(8.95)

36(2.01)

21 (1.17)

6 (0.34)

19(1.06)

11(0.62)

7 (0.39)

2(0.11)

0 (0.00)

19(1.06)

8 (0.45)

4 (0.22)

7 (0.39)

5 (0.28)

1 (0.06)

8 (0.45)

4 (0.22)

2(0.11)

1 (0.06)

1 (0.06)

0 (0.00)

0 (0.00)

3(0.17)

(and %) of sentences

Baltimore

convent

341 (12.51)

281 (10.31)

131 (4.81)

30(1.10)

41 (1.50)

21 (0.77)

14(0.51)

15(0.55)

4(0.15)

1 (0.04)

36(1.32)

46(1.69)

18(0.66)

13 (0.48)

13 (0.48)

16(0.59)

9 (0.33)

6 (0.22)

2 (0.07)

1 (0.04)

1 (0.04)

2 (0.07)

1 (0.04)

14(0.51)

Both

convents

450 (9.97)

441 (9.77)

167(3.70)

51(1.13)

47(1.04)

40 (0.89)

25 (0.55)

22 (0.49)

6(0.13)

1 (0.02)

55 (1.22)

54(1.20)

22 (0.49)

20 (0.44)

18(0.40)

17 (0.38)

17 (0.38)

10 (0.22)

4 (0.09)

2 (0.04)

2 (0.04)

2 (0.04)

1 (0.02)

17 (0.38)

Note. A small percentage of sentences contained more than one type of

emotion word. Nonspecific positive and negative emotion words were

classified as unspecified (e.g., words such as liked and filled with emotion).

These are words that definitely refer to an emotional experience but might

refer to several different basic or complex emotional states.

grammatical complexity, ranging from 0 (simple one-clause sentences) to 7

(complex sentences with multiple forms of embedding and subordination).

Data Analysis

The dependent variables in the analyses were simple measures of all-

cause mortality such as the percent who died by the end of an approxi-

mately 9-year follow-up period and the mortality rate (i.e., deaths per

person-years of observation) for that same period of time. The primary

multivariate method used to investigate mortality was Cox proportional

hazards regression (Allison, 1995). This regression yielded the relative risk

of death, which refers to the ratio of mortality rates (or, more exactly, to the

ratio of hazard functions). Age was adjusted in these analyses by using age

as the time scale for the regression (Allison, 1995). Educational level at the

time the autobiographies were written in early life was adjusted by includ-

ing it as an ordinal variable in the regression. Age- and education-adjusted

survival curves (the probability of a 75-year-old surviving to different

advanced ages) were created using the baseline feature of the Cox regres-

sion procedure in the SAS statistical program (Allison, 1995).

In the regression analyses, ordinal variables were used to characterize

the percentile ranking of each type of emotional expression; that is, the

number of positive emotional words. Binary variables were used in the

regression to characterize the quartile rankings of each type of emotional

expression. These percentile and quartile rankings of emotional-word us-

age were derived using the distribution within each of the two convents.

This was done to obtain comparable scales of emotional expression across

convents because the distribution of emotion-word usage differed between

convents (see Table 2). The primary analyses used three measures of

emotion word usage: (a) the percentile or quartile rankings derived from

the number of sentences containing one or more positive or negative

emotion words or no emotion words; (b) percentile and quartile ranks

derived from the simple counts of positive emotion words; and (c) percen-

tile and quartile ranks of a diversity score generated by counting the

number of different positive emotion categories (see Table 2) scored in

each autobiography.

Results

The current study included 180 participants from the Milwau-

kee,

Wisconsin, and Baltimore, Maryland, convents of the School

Sisters of Notre Dame. Handwritten autobiographies composed

when the sisters were a mean age of 22 years were scored for

positive, negative, and neutral emotional content. When these

autobiographies were written in early life, 82% of the participants

had earned a high school diploma. At the beginning of the Nun

Study in 1991, approximately 58 years later, 91% of them had

earned at least a bachelors degree. During the 9-year mortality

surveillance period, the 180 participants ranged in age from 75

to 95 years and 76 (42%) of them had died (Milwaukee sample =

43%,

Baltimore sample = 42%).

Compared with the Baltimore participants, the Milwaukee par-

ticipants had a lower mean number of positive emotion sentences

(Milwaukee = 3.2, Baltimore = 9.7; p < .001), negative emotion

sentences (Milwaukee = 0.6, Baltimore = 2.0; p < .001), and

nonemotion sentences (Milwaukee =

14.1,

Baltimore = 23.5;/? <

.001).

(Given the very low frequency of neutral emotions, shown

in Tables 1 and 2, their possible relationship to mortality was not

examined.) Although the exact reasons for the differences between

convents in written emotional expression is not known, the differ-

ences in lengths of the autobiographies could simply reflect more

time allowed for the Baltimore sisters to complete the task. Be-

cause of differences in the distribution of these measures between

convents, all analyses were based on percentile and quartile rank-

ings within each convent.

Four basic types of analyses were conducted and all were age

and education adjusted. The first examined the relationship be-

tween risk of mortality and the percentile ranking of the number of

positive emotion sentences, negative emotion sentences, and non-

emotion sentences in the autobiographies from early life. The

second examined the relationships between the risk of mortality

and the quartile ranking of the number of positive emotion sen-

tences, positive emotion words, and different types of positive

emotion words (i.e., categories). The third analysis examined the

age-adjusted survival curves (length of life) as a function of the

quartile rankings of positive-emotion sentences, positive-emotion

words, and different categories of positive emotion words. A

fourth analysis examined the relationships between positive emo-

tion usage and survival after controlling for linguistic ability

demonstrated in the early-life autobiographies, the level of educa-

tion attained at the time the autobiographies were written, and the

lifetime occupation of the participants.

The first Cox regression model we used to investigate mortality

used the percentile ranking of positive emotion sentences, negative

POSITIVE EMOTIONS IN EARLY LIFE

809

emotion sentences, or no emotion sentences and was adjusted for

age and education. The results of these analyses are presented in

Table 3 (Model I). Statistically significant inverse associations

were found between the percentile ranking of the number of

positive sentences in the early-life autobiographies and the risk of

mortality in late-life within each of the convents and in both

convents combined. For example, for every 1.0% increase in the

number of positive-emotion sentences there was a 1.4% decrease

in the mortality rate (i.e., the hazard function from the Cox

regression model). In contrast, there were no statistically signifi-

cant associations between the risk of mortality and the percentile

rankings of the number of negative emotion sentences or the

number of nonemotion sentences.

In another regression model that included age, education, and

the percentile rankings of all three types of sentences (Model II;

see Table 3), the strength of the associations with mortality were

statistically unchanged from those above (Model I). Overall, the

findings from these regressions suggest that positive and negative

content reflected different aspects of written emotional expression.

Because of these findings, the remaining analyses focused on

positive emotions.

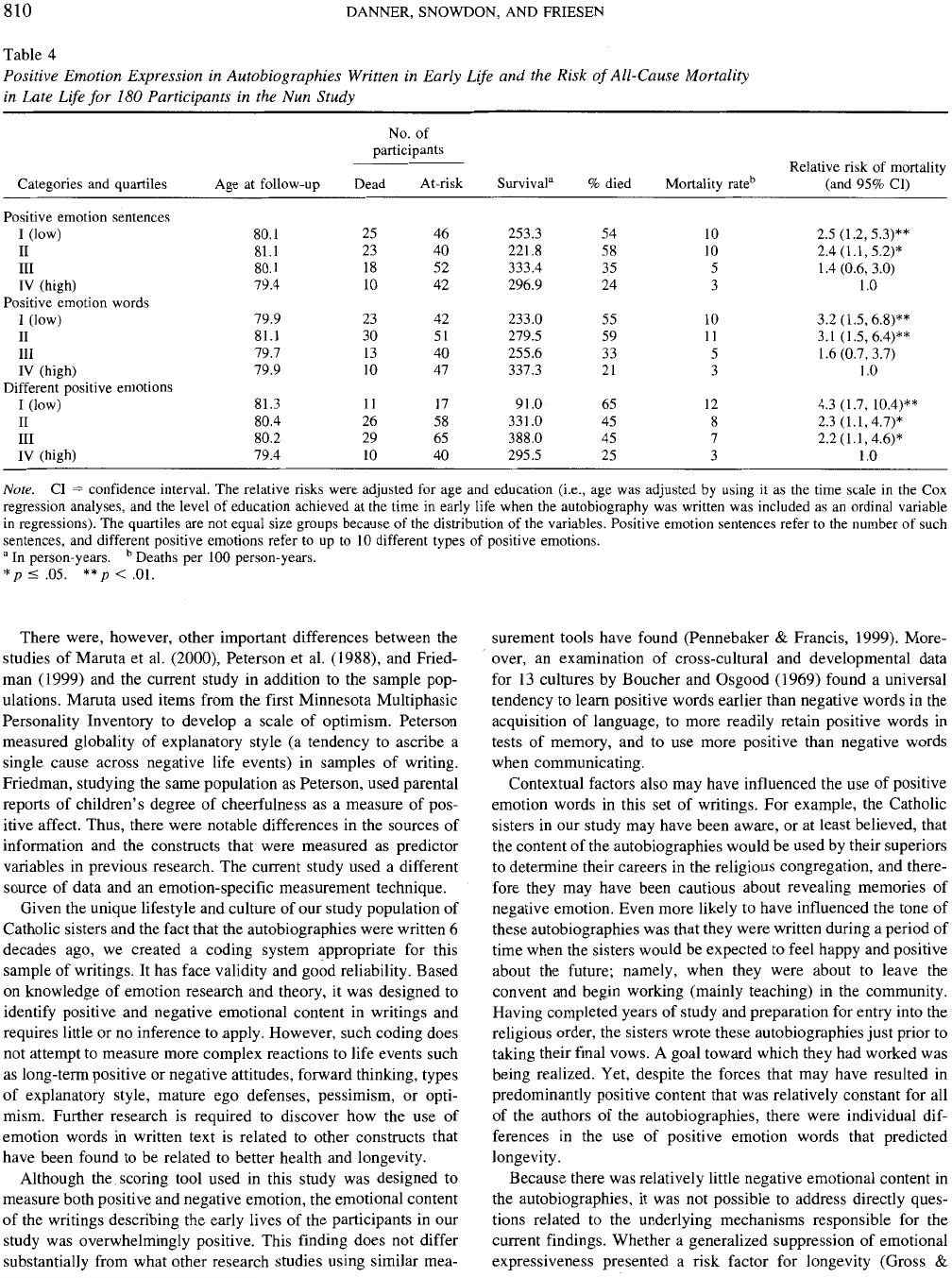

We further explored the association between positive emotion

content and survival using quartile rankings of positive emotion

sentences. Both the percent who had died and the mortality rate

had inverse associations with the quartile rankings of the number

of positive-emotion sentences (see Table 4). Findings from age-

and education-adjusted Cox regression analyses also indicated that

the relative risk of death increased in a stepwise fashion as the

quartile ranking of positive emotion sentences decreased, with

a 2.5-fold difference in mortality between the lowest and highest

quartiles of positive emotional expression. Two other methods of

characterizing positive-emotion content, the number of positive-

emotion words and the number of different positive emotions, also

had strong inverse associations with mortality (see Table 4).

Cox regression also was used to create age- and education-

adjusted survival curves, that is, probabilities of a 75-year-old

surviving to different advanced ages. Figure 1 shows a strong

association between the quartile rankings of the number of positive

emotion sentences and survival: The median age at death was 86.6

years for those in the lowest quartile for the number of positive

emotion sentences, 86.8 for the second quartile, 90.0 for the third

quartile, and 93.5 for those in the highest quartile, that is, a

difference of 6.9 years between the highest and lowest quartiles of

positive emotion sentences. Survival curves for the other two

measures of positive emotion content (not shown) indicated even

stronger associations with survival; in other words, the difference

in the median age at death between the highest and lowest quartiles

was 9.4 years for the number of positive emotion words and 10.7

years for the number of different positive emotions.

Other analyses indicated that there were no material changes in

the association between positive emotion content and survival after

controlling for measures of linguistic ability as demonstrated in the

autobiographies; that is, the 2.5-fold difference in risk of mortality

between the lowest and highest positive emotion sentence quartiles

in Table 4 was a 2.2-fold difference in risk when adjusted for idea

density. Furthermore, the relationship between positive-emotion

content and survival was still apparent after limiting the analyses

to 162 college-educated, lifetime teachers.

Discussion

This study found a very strong association between positive

emotional content in autobiographies written in early adulthood

and longevity 6 decades later. Such a finding is congruent with

other studies by investigators that have found relationships be-

tween longevity and emotion-related concepts. Features of the

current study differ from other studies that have investigated

relationships between emotion-relevant behaviors and longevity or

mortality and may account for the strength of the relationship

observed in the current study: the population sample and the

technique used to measure emotion.

Our findings are compatible with recent longitudinal studies that

suggest that optimism is associated with longer life (Maruta et al.,

2000;

Peterson et al., 1998), but incompatible with another study

indicating that cheerfulness measured in early life was not asso-

ciated with longer survival (Friedman, 1999). In the latter study,

the investigators reported that there were behaviors related to risk

and substance abuse in late-life activities of the more cheerful

participants that may account for their findings (Friedman, 1999).

These types of behaviors should be less of an issue in our study of

Catholic sisters given the relative homogeneity of their adult

lifestyles and environments.

Table 3

Percent Change in the All-Cause Mortality Rate Per Single Percentile Change

in the Ranking of the Number of Sentences

Model I

Sentence type Milwaukee convent Baltimore convent

Both convents

Model II, both

convents

Positive emotion -1.4 (-2.5,-0.2)* -1.4 (-2.7,-0.1)* -1.4 (-2.3,-0.6)*** -1.4 (-2.3,-0.5)**

Negative emotion -0.7 (-1.9, 0.6) -0.7 (-1.9, 0.6) -0.7 (-1.5, 0.2) -0.2 (-1.2, 0.8)

Noemotion 0.5 (-0.6, 1.6) -0.6 (-1.9,0.7) -0.1 (-0.9,0.7) 0.3 (-0.6, 1.2)

Note. 95% confidence intervals appear in parentheses. The mortality rate refers to the hazard function from

Cox regression. Both Models I and II were adjusted for age by using age as the time scale in the regression. The

level of education achieved at the time in early life when the autobiography was written was included as an

ordinal variable in both Model I and II regressions. Three regressions were used for Model I, that is, each

included only one sentence-type variable, as well as age and education. One regression was used in Model II,

that is, it included each of the three sentence-type variables, as well as age and education.

*p£.05.

**p<.01.

***/?<.

001.

810

DANNER, SNOWDON, AND FRIESEN

Table 4

Positive Emotion Expression in Autobiographies Written in Early Life and the Risk of All-Cause Mortality

in Late Life for 180 Participants in the Nun Study

Categories and quartiles

Positive emotion sentences

I (low)

II

III

IV (high)

Positive emotion words

I (low)

II

III

IV (high)

Different positive emotions

I (low)

II

III

IV (high)

Age at follow-up

80.1

81.1

80.1

79.4

79.9

81.1

79.7

79.9

81.3

80.4

80.2

79.4

No.

of

participants

Dead

25

23

18

10

23

30

13

10

11

26

29

10

At-risk

46

40

52

42

42

51

40

47

17

58

65

40

Survival"

253.3

221.8

333.4

296.9

233.0

279.5

255.6

337.3

91.0

331.0

388.0

295.5

% died

54

58

35

24

55

59

33

21

65

45

45

25

Mortality rate

b

10

10

5

3

10

11

5

3

12

8

7

3

Relative risk of mortality

(and 95% CI)

2.5(1.2,5.3)**

2.4(1.1,5.2)*

1.4(0.6,3.0)

1.0

3.2(1.5,6.8)**

3.1 (1.5,6.4)**

1.6(0.7,3.7)

1.0

4.3(1.7, 10.4)**

2.3(1.1,4.7)*

2.2(1.1,4.6)*

1.0

Note. CI = confidence interval. The relative risks were adjusted for age and education (i.e., age was adjusted by using it as the time scale in the Cox

regression analyses, and the level of education achieved at the time in early life when the autobiography was written was included as an ordinal variable

in regressions). The quartiles are not equal size groups because of the distribution of the variables. Positive emotion sentences refer to the number of such

sentences, and different positive emotions refer to up to 10 different types of positive emotions.

" In person-years.

b

Deaths per 100 person-years.

*/7<.05.

**/><.01.

There were, however, other important differences between the

studies of Maruta et al. (2000), Peterson et al. (1988), and Fried-

man (1999) and the current study in addition to the sample pop-

ulations. Maruta used items from the first Minnesota Multiphasic

Personality Inventory to develop a scale of optimism. Peterson

measured globality of explanatory style (a tendency to ascribe a

single cause across negative life events) in samples of writing.

Friedman, studying the same population as Peterson, used parental

reports of children's degree of cheerfulness as a measure of pos-

itive affect. Thus, there were notable differences in the sources of

information and the constructs that were measured as predictor

variables in previous research. The current study used a different

source of data and an emotion-specific measurement technique.

Given the unique lifestyle and culture of our study population of

Catholic sisters and the fact that the autobiographies were written 6

decades ago, we created a coding system appropriate for this

sample of writings. It has face validity and good reliability. Based

on knowledge of emotion research and theory, it was designed to

identify positive and negative emotional content in writings and

requires little or no inference to apply. However, such coding does

not attempt to measure more complex reactions to life events such

as long-term positive or negative attitudes, forward thinking, types

of explanatory style, mature ego defenses, pessimism, or opti-

mism. Further research is required to discover how the use of

emotion words in written text is related to other constructs that

have been found to be related to better health and longevity.

Although the scoring tool used in this study was designed to

measure both positive and negative emotion, the emotional content

of the writings describing the early lives of the participants in our

study was overwhelmingly positive. This finding does not differ

substantially from what other research studies using similar mea-

surement tools have found (Pennebaker & Francis, 1999). More-

over, an examination of cross-cultural and developmental data

for 13 cultures by Boucher and Osgood (1969) found a universal

tendency to learn positive words earlier than negative words in the

acquisition of language, to more readily retain positive words in

tests of memory, and to use more positive than negative words

when communicating.

Contextual factors also may have influenced the use of positive

emotion words in this set of writings. For example, the Catholic

sisters in our study may have been aware, or at least believed, that

the content of the autobiographies would be used by their superiors

to determine their careers in the religious congregation, and there-

fore they may have been cautious about revealing memories of

negative emotion. Even more likely to have influenced the tone of

these autobiographies was that they were written during a period of

time when the sisters would be expected to feel happy and positive

about the future; namely, when they were about to leave the

convent and begin working (mainly teaching) in the community.

Having completed years of study and preparation for entry into the

religious order, the sisters wrote these autobiographies just prior to

taking their final vows. A goal toward which they had worked was

being realized. Yet, despite the forces that may have resulted in

predominantly positive content that was relatively constant for all

of the authors of the autobiographies, there were individual dif-

ferences in the use of positive emotion words that predicted

longevity.

Because there was relatively little negative emotional content in

the autobiographies, it was not possible to address directly ques-

tions related to the underlying mechanisms responsible for the

current findings. Whether a generalized suppression of emotional

expressiveness presented a risk factor for longevity (Gross &

POSITIVE EMOTIONS IN EARLY LIFE

811

1.0

0.9

0.8

m

jrvii

0)

"5

ity

bil

n

rob

a.

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

75

Quartile 1

Quartile 2

Quartile 3

Quartile 4

80 85

Age

90

95

Figure

1.

Quartile rankings of the number of positive emotion sentences in autobiographies written in early life

and the probability of survival in late life for 180 participants in the Nun Study. (Note that the survival curves

for Quartiles 1 and 2 are virtually overlaid on each other.)

Levenson, 1997), or, conversely, whether those persons using

more positive emotion words were in fact more expressive of all

emotions and thereby reduced allostatic load by avoiding the

detrimental effects of suppression could not be tested. Although

negative life events were sometimes mentioned in the autobiogra-

phies,

the participants had not been instructed to include such

events or to elaborate on their resolution. The absence of negative

emotion words in relating negative incidents did not allow a direct

test of whether positive emotion might have been a factor in

muting the adverse effects of negative emotional arousal

(Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998). Finally, the relative absence of

negative emotional content limited the statistical power to detect

associations with mortality. However, the analysis that we could

perform indicated that in this context written negative emotional

content is not the opposite of positive emotional content but,

rather, is a reflection of something different. This finding that

positive emotion may be a different phenomenon from negative

emotion (depression) also was reported by Ostir and colleagues

(Ostir, Markides, Black, & Goodwin, 2000).

Our investigation raises questions about why the positive emo-

tional content in early-life writings might have such a powerful

relationship to longevity. Unfortunately we had no independent

measures of temperament, personality, or emotional tendencies for

participants, and we can only speculate that individual differences

in emotional content in the autobiographies reflect life-long pat-

terns of emotional response to life events.

A pattern of emotional expression that accentuates positive

affect undoubtedly has behavioral correlates that could enhance or

disrupt the positive effects on physiology and health. One behav-

ioral pathway is suggested by the study by Friedman (1999) in

which cheerful participants were more likely to engage in behav-

iors that are health risks such as excessive drinking and smoking.

Such a pathway would be expected to disrupt the potential phys-

iological benefits of a pervading pattern of positive emotional

responsiveness. In contrast, all participants in the current study had

lived a lifestyle in which such health-risk behaviors were improb-

able and therefore the physiological impact of a positive emotional

style was almost certainly enhanced. Because many alternative

paths that might be the consequence of a positive style were not a

part of this study, generalization of the current findings is limited.

Many of the limitations of our study also could be considered

strengths. As mentioned earlier, participants in our study were all

female, had the same reproductive and marital histories, had sim-

ilar social activities and support, did not smoke or drink excessive

amounts of alcohol, had virtually the same occupation and socio-

economic status, and had comparable access to medical care.

Furthermore, the 180 participants had successfully completed a

lifetime within their careers and living situations and many had

lived beyond average life expectancy for their generation by the

time they were enrolled in this study. Although it may be difficult

to generalize from this unique population of Catholic sisters, the

findings of the study should not be minimized. Despite factors in

these sisters' lives that are known to extend life and that might

have overwhelmed any contribution of the mechanisms underlying

our findings, the phenomenon represented by the use of positive

emotion words in early-life writings effectively added to longevity.

It could be argued that the results of this study may not apply to

a sample of participants less than 75 years of age. We are in the

process of searching the convent archives for the autobiographies

of sisters who died prior to the beginning of the study and in

812

DANNER, SNOWDON, AND FRIESEN

particular those who died before age 75. This information will

allow us to examine the possibility that what was found in this

study was the late stages of a relationship between the use of

positive emotion words and longevity that was evident years

earlier. Furthermore, increasing the sample size will increase the

statistical power of future analyses and allow the investigation of

relationships between survival and different types of positive emo-

tional words, such as interest, love, and hope. Finally, our contin-

ued follow-up of the population will allow us to determine whether

this association continues beyond age 95.

Finding such a strong association of written positive emotional

expression to longevity indicates a need for research that sheds

light on the underlying mechanisms and mediators responsible for

and associated with this relationship. Within the context of the Nun

Study, evidence that the expressive patterns observed in the early-

life autobiographies were stable over time would help substantiate

a relationship between emotional expression and temperament and

personality. In future research, we will study late-life writings and

spoken speech samples from the sisters for consistency of the

expressive patterns found in early life.

Archived records of medical history and career path will be

examined for evidence of social and health-related patterns asso-

ciated with what has been observed in the autobiographical writ-

ings and that might suggest pathways taken by participants differ-

ing in their use of positive emotional words that might have

contributed to their longevity or mortality. Considering the poten-

tial impact of positive expressiveness on relationships, we feel that

research is needed to examine possible differences in social and

professional behaviors that may have amplified the effects of a

positive style on longevity.

Given that there have been annual examinations of cognitive

and physical functioning, it will be possible to study relationships

between the emotional content of the early-life writings and late-

life capacities. Also, the results of neurological examinations will

allow study of relationships with neurological functioning and

related disease and disability. Finally, because there will be brain

autopsies on all participants, it will be possible to study relation-

ships between written emotional expressions and neuropathology

and brain structure. These future studies hold promise for identi-

fying underlying mechanisms and mediators that may account for

the findings of the current study.

References

Allison,

P. D.

(1995). Survival analysis using the SAS system:

A

practical

guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

Boucher,

J., &

Osgood,

C. E.

(1969).

The

Pollyanna Hypothesis. Journal

of Verbal Learning

and

Verbal Behavior,

8, 1-8.

Cheung,

H., &

Kemper,

S.

(1992). Competing complexity metrics

and

adults' production

of

complex sentences. Applied Psycholinguistics,

13,

53-76.

Danner, D. D., Friesen, W.

V.,

& Snowdon, D.

A.

(2000). Written emotion

expression code. Unpublished manuscript, University

of

Kentucky, Lex-

ington.

Diener,

E.

(2000). Subjective well-being:

The

science

of

happiness

and a

proposal

for a

national index. American Psychologist,

55,

34-43.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). The repertoire

of

nonverbal behavior:

Cite%OTO4,

CK\%\ns,,

\\4Age,,

ra\&

eoAmg. Semiotica,

],

49-9%.

Ekman, P., Levenson, R. W., & Friesen, W. V. (1983). Autonomic nervous

system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science,

221, 1208-

1210.

Fredrickson,

B. L., &

Levenson,

R. W.

(1998). Positive emotions speed

recovery from

the

cardiovascular sequelae

of

negative emotions.

Cog-

nition

and

Emotion,

12,

191-220.

Friedman,

H. S.

(1999). Personality

and

longevity: Paradoxes.

In J. -M.

Robine, B. Forette, C. Franceschi, & M. Allard (Eds.), The paradoxes of

longevity (pp. 115-122). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Gross,

J. J., &

Levenson,

R. W.

(1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects

of inhibiting negative

and

positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal

Psy-

chology, 106, 95-103.

Headey, B.,

&

Wearing,

A. J.

(1992). Understanding happiness:

A

theory

of subjective well-being. Melbourne, Australia: Longman Cheshire.

Hughes,

C. F.,

Uhlmann,

C, &

Pennebaker,

J. W.

(1994).

The

body's

response

to

processing emotional trauma: Linking verbal text with

autonomic activity. Journal

of

Personality,

62,

565-585.

Izard, C.

E.,

Libero,

D. Z.,

Putnam,

P., &

Haynes,

O. M.

(1993). Stability

of emotion experiences

and

their relations

to

traits

of

personality. Jour-

nal

of

Personality

and

Social Psychology,

64,

847-

860.

Kintsch, W.,

&

Keenan,

J.

(1973). Reading rate and retention

as a

function

of the number

of

propositions

in the

base structure

of

sentences.

Cog-

nitive Psychology,

5,

257-274.

Krantz, D.

S.,

& Manuck, S. B. (1984). Acute psychophysiologic reactivity

and risk

of

cardiovascular disease:

A

review

and

methodologic critique.

Psychological Bulletin,

96,

435-464.

Lazarus,

R. S.

(1991). Emotion

and

adaptation.

New

York: Oxford

Uni-

versity Press.

Levenson,

R. W. (in

press). Autonomic specificity

and

emotion.

In R. J.

Davidson,

K.

Scherer, & H.

H.

Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective

sciences.

New

York: Oxford University Press.

Levenson,

R. W.,

Carstensen,

L. L.,

Friesen,

W. V., &

Ekman,

P.

(1991).

Emotion, physiology, and expression

in old

age. Psychology and Aging,

6,

28-35.

Levenson,

R. W.,

Ekman,

P., &

Friesen,

W. V.

(1990). Voluntary facial

action generates emotion-specific autonomic nervous system activity.

Psychophysiology,

27,

363-384.

Levenson, R. W., Ekman, P., Heider, K., & Friesen, W. V. (1992). Emotion

and autonomic nervous system activity

in the

Minangkabau

of

West

Sumatra. Journal

of

Personality

and

Social Psychology,

62,

972-988.

Malatesta,

C. Z., &

Wilson,

A.

(1988). Emotion cognition interaction

in

personality development:

A

discrete emotions, functionalist analysis.

British Journal

of

Social Psychology,

27,

91-112.

Maruta,

T.,

Colligan,

R. C,

Malinchoc,

M., &

Offord,

K. P.

(2000).

Optimists

vs

pessimists: Survival rate among medical patients over

a

30-year period. Mayo Clinic Proceedings,

75,

140-143.

McEwen,

B. S.

(1998). Stress, adaptation,

and

disease: Allostasis

and

allostatic load. Annals

of the New

York Academy

of

Sciences,

840,

33-44.

Ostir,

G. V.,

Markides,

K. S.,

Black,

S. A., &

Goodwin,

J. S.

(2000).

Emotional well-being predicts subsequent functional independence

and

survival. Journal

of

the American Geriatrics Society,

48,

473-478.

Pennebaker,

J. W.

(1993). Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic

and

therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research

and

Therapy,

31, 539-

548.

Pennebaker,

J. W., &

Francis,

M. E.

(1999). Linguistic Inquiry

and

Word

Count (LIWC). Mahwah,

NJ: LEA

Software

and

Alternative Media/

Erlbaum.

Pennebaker,

J. W., &

King,

L. A.

(1999). Linguistic styles: Language

use

as

an

individual difference. Journal

of

Personality

and

Social Psychol-

ogy,

77,

1296-1312.

Peterson,

C,

Seligman,

M. E. P., &

Vaillant,

G. E.

(1988). Pessimistic

e*p\atiatorj sty\e

« a

risk factor

fox

pYi^sVcaX

fflness-.

A

ftnrty-fwe year

longitudinal study. Journal

of

Personality

and

Social Psychology,

55,

23-27.

Peterson,

C,

Seligman, M.

E.

P., Yurko, K. H., Martin, L.

R.,

& Friedman,

POSITIVE EMOTIONS IN EARLY LIFE

813

H. S. (1998). Catastrophizing and untimely death. Psychological Sci-

ence, 9, 127-130.

Robine, J. -M, Vaupel, J. W., Jeune, B., & Allard, M. (1997). Longevity:

To the limits and

beyond.

Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Rosenberg, S., & Abbeduto, L. (1987). Indicators of linguistic competence

in the peer group conversational behavior of mildly retarded adults.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 8, 19-32.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2000). Optimism, pessimism, and mortality. Mayo

Clinic Proceedings, 75, 133-134.

Singer, B., &

Ryff,

C. D. (1999). Hierarchies of life histories and associ-

ated health risks. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896,

96-115.

Snowdon, D. A. (1997). Aging and Alzheimer's disease: Lessons from the

Nun Study. Gerontologist, 37, 150-156.

Snowdon, D. A., Greiner, L. H., Kemper, S. J., Nanayakkara, N., &

Mortimer, J. A. (1999). Linguistic ability in early life and longevity:

Findings from the Nun Study. In J. -M. Robine, B. Forette, C. Franches-

chi,

& M. Allard (Eds.), The paradoxes of longevity (pp. 103-113).

Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Snowdon, D. A., Greiner, L. H., & Markesbery, W. R. (2000). Linguistic

ability in early life and the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease and

cerebrovascular disease: Findings from the Nun Study. Annals of the

New York Academy of

Sciences,

903, 34-38.

Snowdon, D. A., Kemper, S. J., Mortimer, J. A., Greiner, L. H., Wekstein,

D.

R., & Markesbery, W. R. (1996). Linguistic ability in early life and

cognitive function and Alzheimer's disease in late life: Findings from

the Nun Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 275,

528-532.

Sterling, P., & Eyer, J. (1988). Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain

arousal pathology. In S. Fisher & J. Reason (Eds.), Handbook of life

stress, cognition, and health (pp. 629-649). New York: Wiley.

Swenson, W. M., Pearson, J. S., & Osborne, D. (1973). An MMPI source

book:

Basic item, scale, and pattern data on 50,000 medical patients.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Turner, A., & Greene, E. (1977). The construction and use of a proposi-

tional text

base.

Boulder: Institute for the Study of Intellectual Behavior,

University of Colorado.