Voting rights restoration in

Florida: Amendment 4 -

Analyzing electoral impact &

its barriers

By Alexander Klueber and Jeremy Grabiner (MPPs 2020)

submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Public Policy

Harvard Kennedy School of Government

Master in Public Policy

April 2020

Policy Analysis Exercise

Client: Marc Mauer | Executive Director of The Sentencing Project

Advisor: David C. King | Senior Lecturer in Public Policy. HKS

Advisor: Miles Rapoport | Senior Practice Fellow in American

Democracy. HKS

Seminar Leader: Thomas Patterson | Bradlee Professor of Government

and the Press. HKS

This PAE reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing

the views of the PAE's external client, nor those of Harvard University or any of their

faculty.

CONTENTS

I. Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................

II. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 1

III. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3

IV. Background ........................................................................................................................ 4

V. Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 6

A. Quantitative analysis on electoral impact of Amendment 4 ....................................... 6

a. Data sources ............................................................................................................... 6

b. Data manipulation ..................................................................................................... 8

c. Key assumptions ........................................................................................................ 9

B. Qualitative analysis on voting barriers and modulation strategies ............................ 9

VI. Findings ........................................................................................................................... 10

A. Electoral impact assessment ..................................................................................... 10

a. Quality of correctional data ..................................................................................... 10

b. Size of population eligible to vote after Amendment 4 and SB 7066 ....................... 11

c. Voter registration patterns ...................................................................................... 13

d. Estimation of electoral impact ................................................................................. 16

e. Spill-over effects ...................................................................................................... 23

B. Barriers to reaching the ballot box for the enfranchised .......................................... 24

a. Informational Barriers ............................................................................................. 26

b. Financial barriers ..................................................................................................... 28

c. Mobilizing barriers .................................................................................................. 28

VII. Recommendations ...........................................................................................................30

A. Informational Recommendations .............................................................................30

B. Financial Recommendations .................................................................................... 32

C. Mobilizing Recommendations .................................................................................. 34

D. Summary of recommendations ................................................................................. 35

VIII. Appendix .......................................................................................................................... 36

A. Appendix A – Data sources ....................................................................................... 36

B. Appendix B – Assumptions ....................................................................................... 39

C. Appendix C – Detailed predictions ........................................................................... 57

D. Appendix D – Code for reproduction ........................................................................ 65

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marc Mauer and The Sentencing Project for providing us with an opportunity to

explore this research question. Their guidance and expertise on this were extraordinary and

we are deeply grateful.

In addition, we thank our seminar leader, Thomas Patterson and our advisors, Miles Rapoport

and David King. We are grateful for their willingness to help us on every step of the way.

We want to thank Desmond Meade, Neil Volz, and the FRRC team for hosting us and providing

us with important information from the field. As well as Rep. Sean Shaw, Professor Kathryn

DePalo-Gould, Devon Crawford, and Bruce Riley for their input on the project.

Furthermore, we want to thank the Ash Center and the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and

Management for the funding they provided to conduct this research.

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The passage of Amendment 4 in Florida marked a monumental event for more than 1.4 million

Floridians who could regain their voting rights. However, our findings suggest that only 3.3%

or ~49.000 of them will turn out to cast their ballot in 2020 if all associated legislation stays

in place. We would expect it to rise to 146,000 or 13% in case SB 7066 is repealed.

This paper estimates the impact Amendment 4 and its associated legislation will have on

Florida’s 2020 general election. It uses these estimates to quantify and explore the barriers

that diminish turnout and puts forward recommendations to modulate them.

Our findings suggest no partisan impact by the Amendment and associated legislation on the

electoral map in 2020. Although most counties in our model become increasingly Democratic,

we predict no change in partisan control in any county or at the state level.

Our predictive model allows us to quantify the relevance of the barriers during the journey

from post-sentencing disenfranchisement to the ballot box on election day. Most notable is

the requirement to repay all Legal Financial Obligations (LFOs), as set forth by SB 7066. It

single-handedly disenfranchises more than 1 million citizens who could participate in our

2

democracy. Second to this is the barrier that enfranchised individuals will not exercise their

right to vote. We predict this to be the case for ~300,000 returning citizens, demonstrating

that uncertainty around the right to vote is depressing turnout.

For greater exploration, we reframed the barriers into three broader categories: Informational

Barriers, Financial Barriers, and Mobilizing Barriers. Informational Barriers center around

the lack of a centralized process to determine what an individual owes, difficulty in discovering

one’s eligibility, and lack of awareness of legal options afforded. Financial Barriers stem from

an individual’s inability to pay their LFOs. Mobilizing Barriers stem from apathy towards the

democratic process, lack of engagement with the population, and standard turnout issues.

For each of these categories of barriers, we then outlined recommendations that we hope will

help inform The Sentencing Project’s goals of returning rights to the disenfranchised in this

country.

Recommendations

• Centralized Informational Process

• Change Burden of Proof

• Change Registration Language

• Information Packet at Last Contact

Recommendations

• Repeal SB 7066

• Change Sentencing

• Increase Fundraising

• Partner with Counties

• Exempt 10+ years from LFO requirement

Recommendations

• Streamlined Engagement Strategy

• RC to RC outreach

• Spillover Community outreach

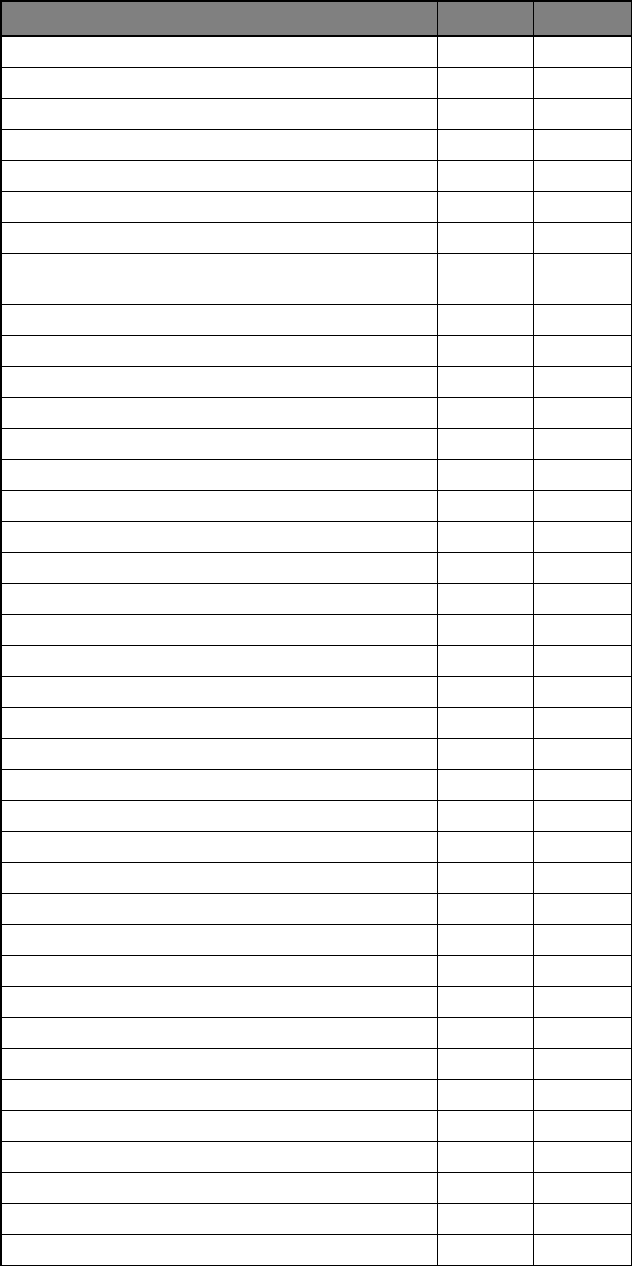

Post-

sentencing

disenfran-

chised voters

Qualified

offenses acc.

to literal

Amendment

Qualified

offenses acc.

to SB 7066

Qualified by

having

fulfilled all

LFOs

Turned out to

vote

(Medium)

Individuals in

Florida

1,487,847

1,454,156

1,435,033

362,614

48,680

Total share

100%

98%

96%

24%

3.3%

3

INTRODUCTION

In 2016 an estimated 6.1 million people were disenfranchised because of felony convictions.

1

This is almost 5 million more than in 1976.

2

The consequences of these policies go beyond the

prohibition to vote - they institutionalize racism, disempower communities and hinder

reintegration.

Through the close ties between felony disenfranchisement and the criminal justice system, the

racist nature of the latter manifests itself in the former. This is to say that a disproportionate

number of Black and Hispanic Americans being incarcerated results in a disproportionate

number being disenfranchised. In line with that, Black Americans over 18 are four times as

likely as the rest of the US population to lose their voting rights as 1 in 13 or ~ 2.2 million black

adults are disenfranchised.

3

Further, disenfranchisement is a painful mechanism of exclusion at the community and the

personal level and often contributes to political apathy for both the individual and the people

around them. Reversing disenfranchisement laws and engaging returning citizens is therefore

crucial to the inclusiveness of American democracy and individual reintegration.

On the back of these insights, states have started to move to less punitive disenfranchisement

legislation. The 2018 passage of Amendment 4 in Florida is the single largest attempt to

reverse these laws. We therefore seek to answer:

1. What is the projected electoral impact of Amendment 4 and associated legislation in

Florida’s 2020 general elections?

2. What barriers are diminishing its electoral impact and how can they be modulated?

From these a series of sub-questions arise. These include: how reliable is the data in our

sample from the Florida Department of Corrections? What is the size of the population eligible

to vote and how many of them are going to turn out on election day? Who is it that will turn

out to vote and how will that impact the governance of the state? What are the barriers

diminishing turnout and how significant are they? How do these barriers manifest themselves

in the journey from post-sentencing disenfranchisement to the ballot box on election day?

What actions can state legislatures and organizations like The Sentencing Project take to

modulate these barriers? What are the spillover effects in the rest of the community?

While we use Amendment 4 in Florida and the partisan nature of the 2020 general election as

the prism of our analysis, our concern is the persistence of disenfranchisement and the

wellbeing of the US democracy. By using a case of particular relevance at this moment in time,

we hope to elucidate systemic considerations of enfranchisement efforts while encouraging

more concern for the newly enfranchised.

1

Uggen, Christopher. 6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement,

2016. (The Sentencing Project, 2016), 3. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-

lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/.

2

Ibid.

3

Uggen, 6 million, 3.

4

BACKGROUND

By 2016, Florida accounted for 27% of the national disenfranchised population, with Black

Americans making up 21% of this (only 16% of general population).

4

Florida’s estimated 1.4

million post-sentencing disenfranchised voters were greater than the population of 11 states

and the District of Columbia, highlighting the consequential impact of Florida’s

disenfranchisement laws on our democracy.

5

At the end of the Civil War, the Florida state legislature began enacting laws that would prevent

freed Black men from participating in the democratic process while maintaining white

supremacy as the order of society. After initially refusing to adopt the 14

th

Amendment, Florida

was forced to draft a new constitution in 1868.

6

However, the new constitution maintained

means of excluding or minimizing the power of Black American citizens.

Under Article XIV Section 2, the constitution instituted its provision of felony

disenfranchisement by stating, “No person under guardianship noa compos mentis, or insane,

shall be qualified to vote at any election, nor shall any person convicted of felony be qualified

to vote at any election unless restored to civil rights.”

7

While the Florida constitution

underwent a variety of changes over the last century, the clause disenfranchising those with

felony convictions remained on the books until 2018 when Amendment 4 was passed through

a referendum.

After an extensive campaign by the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC) and partners,

voters in Florida passed Amendment 4 with 64% of the vote.

8

Amendment 4 stated that “any

disqualification from voting arising from a felony conviction shall terminate and voting rights

shall be restored upon completion of all terms of sentence including parole or probation”.

9

The

amendment however kept in place restrictions on those “convicted of murder and felony sex

offenses”.

10

The passage of the amendment restored voting rights to more than 1.4 million

Florida residents.

Yet the history of right marginalization repeated itself after the election, as the legislature and

newly elected Governor DeSantis introduced and passed SB 7066 which instituted an LFO

therefore significantly limiting the number of people included in the amendment.

The ACLU brought a lawsuit against the state in opposition to this modern poll tax. In a

statement Julie Ebenstein of the ACLU said, “Over a million Floridians were supposed to

reclaim their place in the democratic process, but some politicians clearly feel threatened by

greater voter participation. They cannot legally affix a price tag to someone's right to vote.”

11

Most recently the U.S. Court of Appeals for 11th Circuit in Atlanta ruled in favor of the 17

4

Ibid.

5

Data Access and Dissemination Systems. “American FactFinder - Results.” American FactFinder -

Results. October 5, 2010.

https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk#.

6

Wood, Erika. “Florida: An Outlier in Denying Voting Rights.” Brennan Center for Justice, 2016.

https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Florida_Voting_Rights_Outlier.pdf

7

Florida constitution Art XIV Section 2 retrieved from

https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/189095?id=23

8

Alejandro de la. Garza. “Florida Passes Amendment 4, Restoring Voting Rights for Felons.” Time.

Time. November 7, 2018. https://time.com/5447051/florida-amendment-4-felon-voting/.

9

Florida Constitution. Amendment 4. Article VI Section 4. Retrieved from

https://www.aclufl.org/en/voter-restoration-amendment-text

10

Ibid.

11

“Groups Sue to Block New Florida Law That Undermines Voting Rights Restoration.” 2019. ACLU of

Florida. July 17, 2019. https://www.aclufl.org/en/press-releases/groups-sue-block-new-florida-law-

undermines-voting-rights-restoration.

5

plaintiffs to be allowed to vote.

12

However, it is possible that this case may end up in the U.S

Supreme Court.

Courts can modify an individual’s sentences, eliminate or reduce their fines and convert fines

into community service. The implementation of this provision however has not been done

throughout the state. Only four counties, Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach and

Hillsborough have implemented processes to enact it.

13

Therefore, as the government and electoral officials navigate this implementation process,

thousands of residents will be left unable to decide who will represent them in the upcoming

Presidential election.

12

Periera, Ivan. “Federal Appeals Court Rules against Florida's Restriction on Former Felons from

Voting over Fines.” ABC News. ABC News Network, February 19, 2020.

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/federal-appeals-court-rules-floridas-restriction-felons-

voting/story?id=69073124.

13

Rivero, Daniel. “People Across Florida Are Getting Their Voting Rights Back. Few Republicans Could

Benefit.” WLRN, January 5, 2020. https://www.wlrn.org/post/people-across-florida-are-getting-

their-voting-rights-back-few-republicans-could-benefit#stream/0.

6

METHODOLOGY

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY

DATA SOURCES

To build a predictive model of the electoral impact Amendment 4 will have on the 2020 general

election in Florida, we analyzed more than 12.5 million individuals in Florida, combining

various sources. These included:

• Official Florida voter registration and unofficial voting history information by the

Florida Division of Elections (last updated: 03/20)

14

• Public records of OBIS offender data base in Florida by the Florida Department of

Corrections (last updated: 01/20)

• Historic Florida election results on county and precinct level by the MIT election lab

(last updated: 12/19)

• 2016 Actuarial Life Table by the Social Security Administration

15

• Statute table by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (last updated: 12/19)

16

• Statistics on imposed sanction by offense type in the 2019 Florida’s Criminal

Punishment Code: A Comparative Assessment by the Florida Department of

Corrections (last updated: 10/19)

17

Please refer to Appendix A for a detailed description of the sources, the data and the variables

included.

We encountered significant data limitations due to legal and financial restrictions. These

limitations may be split into two groups:

a) Not included in the sample but relating to individuals who are returning citizens and

who may be eligible to vote in Florida:

o Individuals convicted of a felony, but released from state probation /

community control without serving a custodial sentence

o Individuals who served their sentence outside the Florida state prison system

(e.g. federal prisons, county jails) and reside in Florida

o Future residence of inmates who are currently in prison, but will have served

their sentence in time to register for the general elections

o Outstanding LFOs (court-ordered fees, fines and restitutions) of individuals in

sample

o No modelling of potential recidivism among individuals in the sample

b) Limitations on returning citizens in other states (shortlisted based on demographic,

cultural and voting restrictions) to estimate expected turnout and community spill-

over effects: offender data and/or voter registration data inaccessible in Alabama,

Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia

14

“Voter Extract Disk File Layout.” Florida Department of State, October 18, 2018.

https://dos.myflorida.com/media/696057/voter-extract-file-layout.pdf.

15

“Social Security.” Actuarial Life Table. Accessed March 22, 2020.

https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html.

16

FDLE's Statute Table. Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Accessed December, 2019.

https://web.fdle.state.fl.us/statutes/about.jsf.

17

“Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code: A Comparative Assessment .” Florida Department of

Corrections, October 2019. http://www.dc.state.fl.us/pub/scoresheet/Criminal Punishment Code

2019.pdf.

7

To address the data restrictions under b) we decided to rely on assumptions from expert

interviews and literature. To address the data restrictions under a), we took the following

(imperfect) measures:

• Treat available data points as a sample of the overall post-sentencing disenfranchised

population (estimated to be at 1,487,847). When reduced to post-sentencing

disenfranchised voters (excl. individuals who will still be serving non-financial legal

obligations of their sentence at general election voter registration date, do not reside

in Florida, are fugitives, deported, likely dead, etc.), this sample includes 396,104

individuals.

18

To reflect the differences of offense types between the population

convicted of a felony who had to serve a custodial sentence and the population that

didn’t have to serve a custodial sentence, we adjust the scaling from our sample to the

population based on the data published by the Florida Department of Corrections on

the sanctions imposed by offense type.

19

o There is additional concern around the representativeness of the sample for the

overall population (an example is pointed out by the Crime and Justice

Institute (2019)): “One of the main principles of the CPC is neutrality with

respect to race, gender, and social and economic status. Despite this stated goal

of fairness, defendants with similar criminal conduct and criminal histories

experience vastly different outcomes.”

20

Therefore, we must expect the

population that is convicted of a felony, but released without serving a custodial

sentence to also differ from the one that is not released in terms of judicial

circuit, county, economic status, county of residence, race, etc.).

o Only the 2019 publication of Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code included the

sanctions imposed by offense type on a level granular enough to match it to the

offenses excluded under Amendment 4 and SB 7066. The split for that

particular year may deviate from the historic average.

• Approximate county of future residence for currently active prisoners as the county in

which most felonies have been committed (if an equal number of felonies have been

committed in multiple counties, we go by alphabetical order of counties)

o The proxy may be flawed, because individuals move, have committed felonies

in counties in which they don’t live, etc.

o Note: this limits the granularity of our analysis to the level of counties (no

longer possible to have analysis at level of individual elections)

• Estimate outstanding LFOs at county level based on racial and county metrics outlined

for 58 counties in Expert testimony by Daniel A. Smith in September 2019.

21

o This forces us to make a concerning oversimplification of individual

circumstances based on county affiliation and race

o Average unlikely representative for 9 outstanding counties, because of size and

enfranchisement efforts (Broward, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, Hillsborough

with systematic effort to reinstate enfranchisement by waiving/transferring

fees and fines in exchange for community service)

18

Uggen, Christopher. 6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement,

2016. (The Sentencing Project, 2016), 3. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-

lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/.

19

“Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code: A Comparative Assessment.” Florida Department of

Corrections, October 2019. http://www.dc.state.fl.us/pub/scoresheet/Criminal Punishment Code

2019.pdf.

20

Marguiles, Lisa, Sam Packard, and Len Engel. “An Analysis of Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code.”

Crime and Justice Institute, June 2019. https://www.crj.org/assets/2019/06/An-Analysis-of-Florida-

CPC-June-2019.pdf.

21

Dan A. Smith, on behalf of plaintiffs Consolidated Case No. 4:19-cv-300. August 2, 2019.

https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/gruver_v_barton_-

_expert_report_of_daniel_a._smith_ph.d.pdf

8

o Note: this limits the granularity of our analysis to the level of counties (no

longer possible to have analysis at level of individual elections)

In addition, there is a real concern around the validity of the addresses available for individuals

from the department of correction, as shall be demonstrated under “Quality of correctional

data”.

DATA MANIPULATION

Using the entire offender database (active, released, supervised), we selected the population

that would gain enfranchisement via Amendment 4 as postulated by SB 7066 by excluding:

a) Individuals that will not have served their non-financial sentence by Oct. 5 2020

(Florida general election registration date)

b) Individuals that are expected to be deceased

c) Individuals that have committed disqualifying offenses (murder or sexual offenses) at

any point in time (as defined literally by the Amendment and as specified in SB 7066)

d) Individuals that no longer reside in Florida

e) Individuals who are expected to have outstanding LFO’s by Oct. 5 2020

We then combined this data with the Florida voter registration data to determine which

enfranchised individuals have registered to vote. We did so by harmonizing naming

conventions and adapting the notation (lowercase, removing all punctuation) of a person’s

first name, last name, name suffix, date of birth, race code, and sex code in both databases and

concatenating them to match them across the data sets.

Using these inputs, we leveraged a series of assumptions (detailed in the next chapter) to

model at the county and state level the number of enfranchised voters, the number of expected

votes and the partisan allocation of these votes and then compared that to the margin of victory

in each county in the 2016 presidential elections.

Lastly, we translated this information into four tables and four maps, estimating the electoral

impact of Amendment 4 for the various counties in Florida and statewide elections:

• Potential electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020

• Scenario 1 – medium turnout: expected electoral significance of Amendment 4 with

and without SB 7066

• Scenario 2 – low turnout: expected electoral significance of Amendment 4 with and

without SB 7066

• Scenario 3 – high turnout: expected electoral significance of Amendment 4 with and

without SB 7066

9

KEY ASSUMPTIONS

ID

Variable

Assumptions

Source

a)

Population down-

scaling

According to sample with

corrections for felons with /

without custodial sentence

Table.1

b)

Mapping offense type

to sanction imposed

for felons

See Appendix B

Florida Department of

Corrections, Florida’s Criminal

Punishment Code: A Comparative

Assessment, October 2019.

c)

Disqualifying offenses

acc to literal

interpretation of

Amendment

See Appendix B

Dara Kam, Meaning of 'murder'

key in Florida felons' voting

rights, January 2019.

d)

Disqualifying offenses

acc to SB 7066

See Appendix B

Florida Senate Bill No. 7066.

e)

Legal Financial

Obligations

See Appendix B

Dan A. Smith, on behalf of

plaintiffs Consolidated Case

No.4:19-cv-300. September 17,

2019.

f)

Life expectancies

See Appendix B

Social Security Administration,

Actuarial Life Table 2018.

g)

Voter turnout

High: 35%

Medium (Expected): Black:

16%, Others: 12%

Low: 5%

See Appendix B

h)

Spill-over effect

1.72

Expert interviews

i)

Party predilection

pattern 1

Observations among 150,000

ex-felons for which governor

Crist restored voting rights in

2007 convicted of less serious

offenses

Marc Meredith and Michael

Morse, Why letting ex-felons vote

probably won’t swing Florida,

November 2018.

j)

Party predilection

pattern 2

Party affiliation of matched

registered enfranchised voters

Table.4

k)

Total population

estimate

1,487,847

Uggen, Christopher. 6 Million

Lost Voters: State-Level

Estimates

of Felony Disenfranchisement,

2016.

Please refer to Appendix B for a detailed description of the assumptions.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY

A portion of our qualitative work relied on interviews. These interviews were influential in

providing a landscape of the issues, comparative analysis to other states, and a means of

verifying certain legal aspects regarding felony disenfranchisement. Academics, advocates,

and elected officials were the three categories of individuals that we interviewed. Interviews

were conducted by phone as well as face-to-face and were recorded with the permission of the

interviewees. Interviews were conducted both in a semi-structured and unstructured format.

10

FINDINGS

ELECTORAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT

The analysis found interesting findings in five areas:

a. Quality of correctional data (used as a source by majority of researchers on this topic)

b. Size of population eligible to vote

c. Voter registration patterns

d. Estimation of electoral impact

e. Spill- over effects

QUALITY OF CORRECTIONAL DATA

A comparison of the addresses from registered enfranchised individuals in the Florida

Department of Correction OBIS Offender Database and the voter registration data, indicated

that their overlap is low. Of the 23,843 individuals that we could match across the data sets,

only 76% had a matching county, 38% a matching Zip Code and 12% a matching address. Of

these 23,843 individuals, 13,092 registered to vote after Amendment 4 was enacted. This is

55% of the matched individuals thus raising concerns on the reliability of the correctional data

that the majority of researchers in this space rely on.

11

SIZE OF POPULATION ELIGIBLE TO VOTE AFTER AMENDMENT 4 AND SB

7066

In the media and most academic research, the population to be enfranchised by Amendment

4 is estimated to stand at around 1.5 million. This number originates from an estimate by the

Sentencing Project on the number of post-sentencing disenfranchised individuals in Florida.

22

As detailed before, Amendment 4 outlines 3 limitations to the right to vote:

• Completion of all terms of the sentence including parole or probation

• Doesn’t apply to those convicted of murder

• Doesn’t apply to those convicted of sexual offenses

The almost 1.5 million does not yet consider the latter two. They may be interpreted literally

according to the text in Amendment 4 or more stringently as outlined in SB 7066. In the latter,

case murder includes only first-degree murder and sexual offenses include only rape and sex

offenses against children. In the broader interpretation according to SB 7066 murder also

includes second degree murder and homicide, and sexual offenses include anything that leads

to a listing on the sex offender list. (Please see Appendix B Disqualifying offenses acc to SB

7066 for details).

As Table.1 below indicates, a literal interpretation will exclude around 2% or ~32,000

individuals from political participation. This number rises by another ~20,000 individuals or

1.5% when broadening the extent of the interpretation along the lines of SB 7066. These

estimates result from classifying individuals based on the description in their adjudication

charge (see appendix A c) and d) for details).

However, the main point of contention is how to interpret “all terms of the sentence”. The

ballpark around how many individuals may regain their right to vote changes significantly

when LFOs are included. The share remaining of the sample drops from around 96% to just

24%. If applied as an estimate for the entire population, it disenfranchises more than 1 million

individuals. This estimate follows when we allocate the individuals in our sample to counties

based on their addresses (in voter registration files, in OBIS database or if neither was

available for current inmates approximated as described under “Data Sources”) and then apply

the county level assumptions for outstanding LFO’s and ability to repay (see Appendix B e) for

details).

An expected turnout rate of around 14% among this population (see medium scenario) would

then result in 48,680 additional votes, or about 3.3% of the people who originally had the

prospect of regaining their right to vote.

As we are working with a sample that covers around 27% of the entire estimated population,

there is significant uncertainty around these estimates.

22

Uggen, Christopher. 6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement,

2016. (The Sentencing Project, 2016), 3. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-

lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/.

12

Table 1: Barriers to electoral impact for enfranchised

Post-

sentencing

disenfran-

chised voters

Qualified

offenses acc.

to literal

Amendment

Qualified

offenses acc.

to SB 7066

Qualified by

having

fulfilled all

LFOs

Turned out to

vote

(Medium)

Individuals in

Florida

1,487,847

1,454,156

1,435,033

362,614

48,680

Total share

100%

98%

96%

24%

3.3%

Sample

individuals

396,104

363,210

350,136

59,602

Share of

sample

100%

92%

88%

15%

Non-sample

individuals

1,091,743

1,090,946

1,084,897

303,012

Share of non-

sample

100%

100%

99%

28%

13

VOTER REGISTRATION PATTERNS

Uncertainty around the right to vote is a significant depressor of voter turnout among the

enfranchised. The punishments for voting illegally is too severe to risk when an individual is

uncertain of their voter status.

The legal obscurity around the interpretation of Amendment 4 is a prime source of

uncertainty. This also expresses itself when we look at the voter registration patterns among

the 13,092 individuals that we matched as having registered since the Amendment was

enacted on a timeline together with the major legal decisions around the bill:

1. 2018-11-06: Amendment 4 passes

2. 2019-01-08: Amendment 4 takes effect

3. 2019-05-03: SB 7066 passes

4. 2019-07-01: SB7066 is signed into law

5. 2019-10-18: Federal District Court declares inclusion of FLOs in SB 7066 unconstitutional

and allows the 17 individuals plaintiffs with FLOs in the case to register

6. 2020-01-16: Florida Supreme Court declares SB 7066 and inclusion of FLOs constitutional

7. 2020-02-19: Eleventh Circuit Court declares inclusion of FLOs in SB 7066 unconstitutional

Graph 1: Timeline of matched enfranchised voter registrations

14

The graph shows a first smaller rise in registrations upon the passing of the Amendment (1).

This can be interpreted as an increased interest resulting from the public attention around the

Amendment by individuals convicted of less serious offenses that had regained their right to

vote in 2007 with Governor Crist’s executive order. There was an immediate spike in

registrations after the Amendment took effect in January 2019 (2) that decreased over the

ensuing months. However, as the public discussion around the Amendment escalated prior to

SB 7066 being enacted, the number of registrations increased again until then (4). The circuit

court’s decision to challenge the inclusion of LFOs in “serving a sentence” and extend

protection to individuals potentially enfranchised under Amendment 4 was followed by a

further increase in registration numbers (5). An overall upwards trend remained (with strong

fluctuations) until the Florida Supreme Court declared that LFO’s would be included in their

interpretation of “serving a sentence” in January 2020 (6), which resulted in a drop of

registrations. As the primary registration season began ramping up, so did the number of

registrations, which shows the correlation between voter registrations and legislation

uncertainty.

A comparison of characteristics among the individuals in our sample who registered and the

individuals in our sample who have not registered indicates a high proportion of African

American registrants. While only 44% of the sample population is African American, 60% of

the matched registrants are. The opposite is true for the White population (see Table.2), where

52% in the sample compare with 39% among the registered matched individuals. In terms of

gender the pattern of registrants roughly matches that of the overall sample (See Table.3). It

also stands out that there is a predilection for the Democratic party (55%) among the

enfranchised registered to vote of more than 2 to 1 compared to the Republican party (21%).

The block of no or other affiliations (24%) is significant (See Table.4).

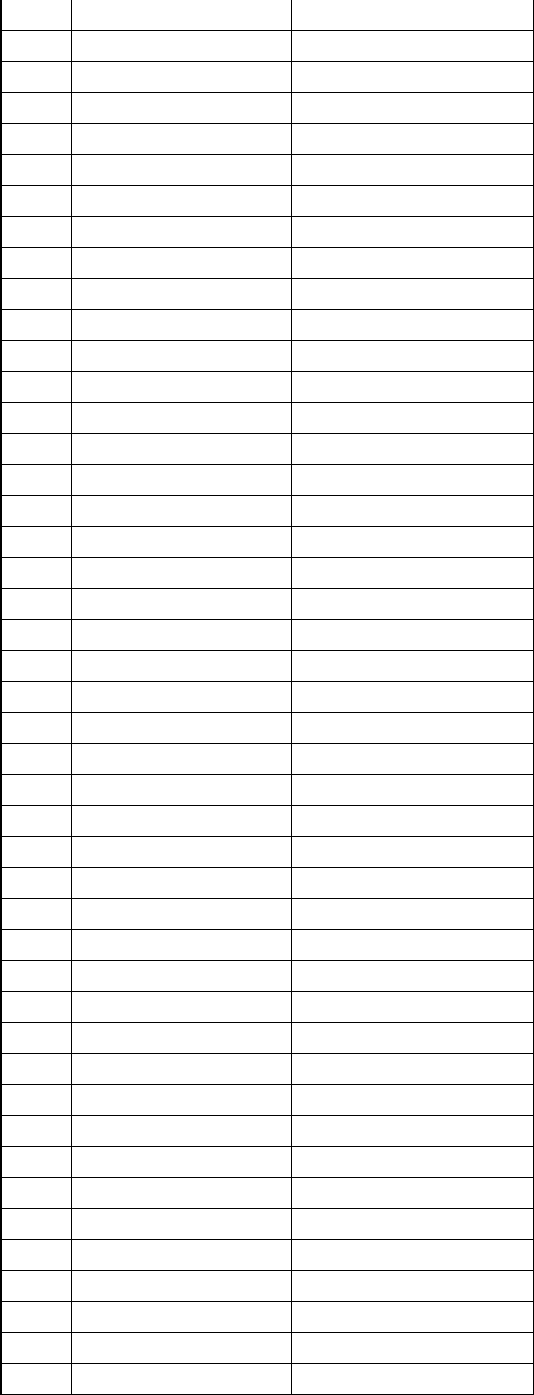

Table 2: Racial split of registered and total enfranchised population

Racial split b/w matched registered enfranchised voters and all enfranchised voters in

sample (March)

All enfranchised voters in

sample

Registered enfranchised voters

in sample

Race

Absolute

number

Share

Absolute

number

Share

White

170,764

52%

5,276

39%

Black

146,870

44%

8,145

60%

Hispanic

12,042

4%

216

2%

All others/unknown

872

0%

3

0%

AAPI

265

0%

6

0%

Asian or pacific islander

51

0%

2

0%

Total

330,864

100%

13,648

100%

Source: Florida Division of Elections, Florida Department of Corrections, own analysis.

15

Table 3: Gender split of registered and total enfranchised population

Gender split between registered enfranchised voters and all enfranchised voters in sample

(March)

All enfranchised voters in

sample

Registered enfranchised voters in sample

Sex

Absolute

number

Share

Absolute

number

Share

Male

279,632

85%

11,330

83%

Female

51,232

15%

2,318

17%

Total

330,864

100%

13,648

100%

Source: Florida Division of Elections, Florida Department of Corrections, own analysis.

Table 4: Party affiliation of registered enfranchised voters

Party affiliation for registered enfranchised voters in sample (March)

Party

Absolute

Share

DEM

7,522

55%

NPA

2,952

22%

REP

2,916

21%

IND

225

2%

LPF

20

0%

CPF

7

0%

REF

5

0%

PSL

1

0%

Total

13,648

100%

Source: Florida Division of Elections, Florida Department of Corrections, own analysis.

16

ESTIMATION OF ELECTORAL IMPACT

Potential impact

Amendment 4 has the potential to change the future of Florida’s electoral landscape.

Regardless of the restrictions outlined in SB 7066, we estimate that more than 360,000 new

votes could be cast. The newly enfranchised will be able to swing votes both on the state level

and in 5 of the 67 counties (all of which are controlled by the Republican party). This uses the

2016 Presidential elections as a baseline and works under the assumption that all other

variables (voter turnout, voting location, which party to vote for, etc.) would remain the same.

What could further strengthen the impact of the Amendment are the implications for the

communities that the enfranchised individuals are part of. Many of these tend to be

communities of low voting propensity. A Randomized Control Trial in the Orlando Mayoral

election suggests that the spill-over effects combined with an outreach effort could be as high

as 1.72 times the original vote.

23

When we consider this very optimistic spill-over effect, we

would be looking at almost 1,000,000 additional votes in Florida, enough to change the

outcome of the last 7 elections for president in Florida and flip 11 counties (2 of which

controlled by the Democratic party and 9 of which controlled by the Republican party) in

relation to their 2016 outcomes (See Table.5 for details).

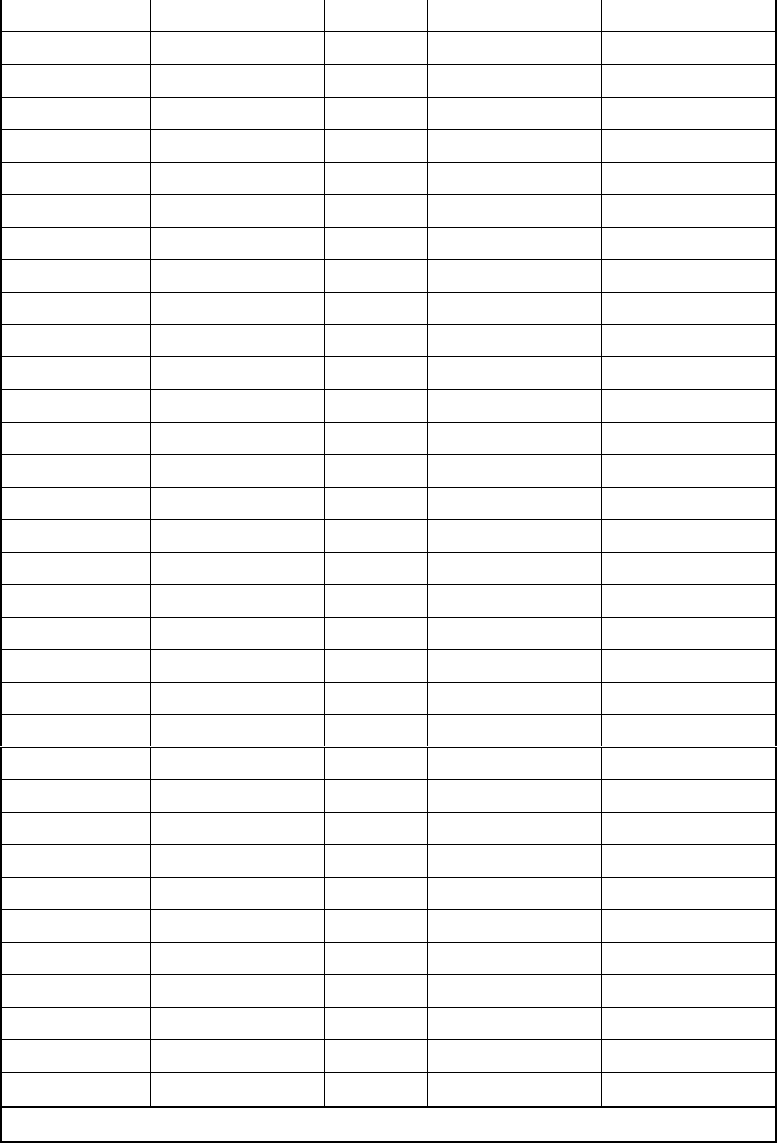

Table 5: The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020 – Potential

The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020

2016 results

2020 estimate

County

Incumbent

Victory

margin

Enfranchi-

sed voters

Enfranchised

& spillover

Potential to

swing

(enfranchised)

Potential to

swing

(enfranchised

& spillover)

Duval

Republican

5,968

16,348

44,467

Yes

Yes

Gadsden

Democratic

8,292

3,145

8,554

No

Yes

Hendry

Republican

1,580

803

2,184

No

Yes

Hillsborough

Democratic

41,026

28,753

78,208

No

Yes

Jefferson

Republican

389

785

2,135

Yes

Yes

Monroe

Republican

2,933

1,703

4,632

No

Yes

Pinellas

Republican

5,500

21,641

58,864

Yes

Yes

Polk

Republican

39,997

17,315

47,097

No

Yes

Seminole

Republican

3,529

8,329

22,655

Yes

Yes

St. Lucie

Republican

3,408

11,401

31,011

Yes

Yes

Wakulla

Republican

6,164

3,237

8,805

No

Yes

Statewide

Republican

112,911

362,611

986,305

Yes

Yes

Source: See assumptions and own analysis.

23

Desmond Meade and Neil Volz, January 2020.

17

We subsequently explore three scenarios of voter turnout among returning citizens, while we

keep all other assumptions stable. These assumptions are based on various papers and expert

interviews that suggest a turn out range between 5% and 35%. However, these papers fail to

consider the impact the presence of FRRC will have on voter turnout. Their statewide

organizing efforts to support the newly enfranchised population’s rights to vote is unique and

therefore not reflected in the academic papers drawing inferences from felon turnout in past

elections.

Graph 2: The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020 – Potential

18

Table 6: Overview of assumptions on turnout scenarios

Scenarios

Turnout

Sources

High

35%

1. RCT by FRRC

2. Christopher Uggen and Jeff Manza in Democratic Contraction?

Political Consequences of Felon Disenfranchisement in the US

Medium

Black: 16%

White: 12%

1. Meredith and Morse in Why letting ex-felons vote probably

won’t swing Florida

2. Traci Burch in Turnout and Party Registration among Criminal

Offenders in the 2008 General Election

Low

5%

Michael V. Haselswerdt in Con Job: An Estimate of Ex-Felon

Voter Turnout Using Document-Based Data

For each of these scenarios we are comparing two potential patterns of party affiliation. The

first is based on the voting pattern among the 150,000 returning citizens convicted of less

serious offenses that regained their right to vote in 2007 by executive clemency of Governor

Charlie Crist. 87% of black voters registered as Democrats while 40% of non-Black voters

registered as Republicans, 34% as Democrats and 26% with neither of the two parties. Just

16% of Black and 12% of nonblack returning citizens voted.

24

The second is based on the

pattern among the matched registrants (See Table.4 in f).

24

Meredith, Marc, and Michael Morse. “Why Letting Ex-Felons Vote Probably Won't Swing Florida.”

Vox. Vox, November 2, 2018. https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2018/11/2/18049510/felon-voting-

rights-amendment-4-florida.

19

Scenario: 1 – Medium Turnout: Expectation of Amendment 4 to swing the vote

In the medium scenario (the most likely), with a turnout between 12% and 16%, our

predictions show that no counties would change control. In this scenario just 3.3% or ~49,000

of the almost 1.5 million post-sentencing disenfranchised voters actually turn out to cast their

votes. The governance of the state would remain with the incumbent party. Looking at the

predictions on a county level according to party affiliation pattern 1 (modelling affiliation after

150,000 returning citizens enfranchised in 2007), the marginal vote would turn more

Republican in 2 counties, would remain stable in 5 counties and would become more

Democratic in the remaining 60 counties as well as at state level. The root of this can be traced

back to the higher registration rate among matched African American registrants. Graph 3

illustrates these predictions by visualizing the additional votes through the Amendment

(enfranchised & spillover as a % of the decisive margin in 2016).

It is noteworthy that state-wide elections are more prone to flip than most county level races.

Graph 3: The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020 - Medium

20

The electoral consequences of SB 7066 are highlighted by Table 7. The table depicts our

predictions without SB 7066 in place. We would expect ~195,000 returning citizens to vote

instead of 49,000, an increase of 146,000 votes. This would constitute ~13% of the post-

sentencing disenfranchised population in the state instead of 3.3%. In terms of partisan

politics this would translate into 5 counties flipping from Republican to Democratic control.

In addition, the statewide results would change from Republican to Democratic (Table 7).

Table 7: The electoral significance of SB 7066 in 2020 – Medium scenario

The electoral significance of SB 7066 in 2020

2016 results

2020 estimate

County

Incum-

bent

party

Victory

margin

Enfran-

chised

voters

Enfran-

chised &

spillover

Shift

in

votes

(pat. 1)

Advan-

tage

(pat. 1)

Partisan

swing

(pat. 1)

Shift

in

votes

(pat. 2)

Advan-

tage

(pat. 2)

Partisan

swing

(pat. 2)

Duval

Rep

5,968

9,222

25,084

10,486

Dem

Yes

8,429

Dem

Yes

Jefferson

Rep

389

439

1,194

530

Dem

Yes

397

Dem

Yes

Pinellas

Rep

5,500

11,565

31,457

7,964

Dem

Yes

10,619

Dem

Yes

Seminole

Rep

3,529

4,489

12,210

3,650

Dem

Yes

4,113

Dem

Yes

St. Lucie

Rep

3,408

5,977

16,257

2,921

Dem

No

5,508

Dem

Yes

Statewide

Rep

112,911

195,205

530,953

146,464

Dem

Yes

179,062

Dem

Yes

Source: See assumptions and own analysis.

21

Scenario: 2 – Low Turnout: Expectation of Amendment 4 to swing the vote

In the low scenario, with a turnout of just 5%, we would expect no county to change control

and the governance of the state to remain with the incumbent party. Employing party

affiliation pattern 1 (modelling affiliation after 150.000 returning citizens enfranchised in

2007), the vote would turn more Republican in 2 counties, would remain stable in 12 counties

and would become more Democratic in the remaining 53 counties as well as at state level. Of

the post-sentencing disenfranchised voters only ~1.45% would cast their votes.

If SB 7066 were repealed in this context, the number of enfranchised voters that cast their vote

would go up to ~5% or ~73,000. There would be no partisan impact on county or the state

level.

Graph 4: The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020 – Low

22

Scenario: 3 – High Turnout: Expectation of Amendment 4 to swing the vote

Even in a high scenario the expected voter turnout among the enfranchised population would

reach only 35%. With SB 7066 in place, two counties and the statewide elections might flip

from Republican to Democratic control. Depending on the party pattern employed (true only

for pattern 2) these predictions differ (Table 8). We would predict ~127,000 new voters to cast

their votes or 8.5% of the post-sentencing disenfranchised population in Florida. Looking at

the predictions on a county level according to party affiliation pattern 1 (modelling affiliation

after 150,000 returning citizens enfranchised in 2007), the marginal vote would turn more

Republican in 2 counties, would remain stable in 2 counties and would become more

Democratic in the remaining 63 counties as well as at state level.

Table 8: The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020 – High scenario

The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020

2016 results

2020 estimate

County

Incum-

bent

party

Victory

margin

Enfran-

chised

voters

Enfran-

chised &

spillover

Shift

in

votes

(pat. 1)

Advan-

tage

(pat. 1)

Partisan

swing

(pat. 1)

Shift

in

votes

(pat. 2)

Advan-

tage

(pat. 2)

Partisan

swing

(pat. 2)

Pinellas

Rep

5,500

7,574

20,601

3,988

Dem

No

6,952

Dem

Yes

St. Lucie

Rep

3,408

3,985

10,839

1,390

Dem

No

3,656

Dem

Yes

Statewide

Rep

112,911

126,841

345,003

74,617

Dem

No

116,483

Dem

Yes

Source: See assumptions and own analysis.

23

Graph 5: The electoral significance of Amendment 4 in 2020 - High

The electoral consequences of SB 7066 are highlighted by Table 9. The table depicts our

predictions without SB 7066 in place. We would expect ~509,000 returning citizens to vote

instead of ~127,000 an increase of ~382,000 votes. This would constitute ~34% of the post-

sentencing disenfranchised population in the state instead of 8.5%. In terms of partisan

politics, this would translate into 5 counties flipping from Republican to Democratic control.

In addition, the statewide results would change from Republican to Democratic (Table 9).

24

Table 9: The electoral significance of SB 7066 in 2020 – High scenario

The electoral significance of SB 7066 in 2020

2016 results

2020 estimate

County

Incum-

bent

party

Victory

margin

Enfran-

chised

voters

Enfran-

chised &

spillover

Shift

in

votes

(pat. 1)

Advan-

tage

(pat. 1)

Partisan

swing

(pat. 1)

Shift

in

votes

(pat. 2)

Advan-

tage

(pat. 2)

Partisan

swing

(pat. 2)

Duval

Rep

5,968

22,958

62,446

10,486

Dem

Yes

21,102

Dem

Yes

Jefferson

Rep

389

1098

2,987

530

Dem

Yes

995

Dem

Yes

Pinellas

Rep

5,500

30,375

82,620

7,964

Dem

Yes

27,872

Dem

Yes

Seminole

Rep

3,529

11,687

31,789

3,650

Dem

Yes

10,750

Dem

Yes

St. Lucie

Rep

3,408

15,981

43,468

2,921

Dem

Yes

14,666

Dem

Yes

Statewide

Rep

112,911

508,644

1,383,512

299,164

Dem

Yes

467,111

Dem

Yes

Source: See assumptions and own analysis.

See Appendix D for detailed predictions.

In conclusion, our analysis indicates that the impact of Amendment 4 on the electoral map of

2020 is significantly dampened if SB 7066 remains in place. If however it is repealed, we

expect the Amendment to swing the vote at the state level in the 2020 Presidential election.

25

SPILL-OVER EFFECTS

A key assumption in our modelling is the large spill-over effect that voter participation of

returning citizens will have on the people around them. The current literature suggests that

enfranchised individuals who live in communities with a high percentage of disenfranchised

individuals have a lower than state average voter turnout. This dampening effect was first

studied by Marc Mauer and Ryan King for the Sentencing Project. Their analysis focused on

specific districts in Georgia where Black Males had a 5% lower turnout rate compared to their

White Male counterparts.

25

Building on this research, Browers and Preuhs used a statistical

analysis to further demonstrate that the negative effect of felony disenfranchisement on the

political participation of non-felons was statistically significant in Black communities.

26

Anecdotally, Desmond Meade said this effect was common sense to him. “Back in the Civil

Rights Era, when dad went to vote he took his whole family. That civic engagement was part

of the conversation at the dinner table for the family… When you strip dad and mom the right

to vote then you’re not having those conversations.” This emphasizes the point that the impact

on felony disenfranchisement laws expands beyond those who are directly impacted

(returning citizens) but includes those in their families and communities and specifically has

an increased impact on those in Black communities.

Understanding the literature and contextual background to the dampening effects of felony

disenfranchisement laws on the broader community and electorate, we expected the opposite

to occur through Amendment 4. This is to say, that with the restoration of voting rights for a

specific population, that their family members and community will find themselves more

responsive to the democratic process than they previously were. Sean Shaw, former State Rep

and Democratic AG candidate in 2018, commenting on this effect:

“If people go through the effort of getting their rights restored then it certainly seems to me

that you’re going have that inverse kind of thing be true where people in that household are

now going to take voting that much more serious because they got someone who had it

stripped away and now have it restored… If an individual has jumped through the hoops to get

their rights restored they are going to be anything but apathetic [about voting] and that affects

the people around them.”

27

This underscores that the impact is not limited to returning citizens alone but includes family

and community level impact.

25

King, Ryan S., and Marc Mauer. 2004. The Vanishing Black Electorate: Felony Disenfranchisement

in Atlanta, Georgia. The Sentencing Project. Available at hhttp://www.sentencing- project.org

26

Bowers, M. and Preuhs, R.R. (2009), Collateral Consequences of a Collateral Penalty: The Negative

Effect of Felon Disenfranchisement Laws on the Political Participation of Nonfelons*. Social Science

Quarterly, 90: 722-743. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00640.x

27

Sean Shaw, in expert interview. February 2020

26

BARRIERS TO REACHING THE BALLOT BOX FOR THE ENFRANCHISED

Table 10: Barriers to electoral impact for enfranchised

Post-

sentencing

disenfran-

chised voters

Qualified

offenses acc.

to literal

Amendment

Qualified

offenses acc.

to SB 7066

Qualified by

having

fulfilled all

LFOs

Turned out to

vote

(Medium)

Individuals in

Florida

1,487,847

1,454,156

1,435,033

362,614

48,680

Total share

100%

98%

96%

24%

3.3%

Sample

individuals

396,104

363,210

350,136

59,602

Share of

sample

100%

92%

88%

15%

Non-sample

individuals

1,091,743

1,090,946

1,084,897

303,012

Share of non-

sample

100%

100%

99%

28%

Based on our estimate of the population eligible to vote after Amendment 4, SB 7066 and

expert interviews, we further detailed the barriers to the impact of Amendment 4. The

subsequent infographic illustrates the road for returning citizens to reclaim their vote, placing

the above in the larger context while extracting the barriers in more detail based on the

interviews.

We identified three cross-cutting barriers:

a. Informational barrier

b. Financial barrier

c. Mobilizing barrier

27

28

INFORMATIONAL BARRIERS

The informational barrier persists throughout the entire “road” to reach the ballot box. The

difficulty accessing relevant information or the ignorance on the options available are main

focal points that need to be addressed.

What is Owed

In the Financial Barrier section of the roadmap, we mention that LFOs are an automatic

indicator of whether an individual is eligible to have their voting rights restored. As such,

accessing how much is owed is an integral step in the realization of one’s rights being restored.

But, in the state of Florida there is no centralized method of accessing this information. Most

of the LFOs are owed to and collected by the county in which an individual was convicted.

Each county therefore has an account of what is owed to it, although county records are often

incomplete. While many returning citizens will be aware of their debt due to collection

solicitations, accessing that information in lieu of these solicitations are a significant barrier,

especially if it is spread out across multiple counties. This barrier is compounded for

individuals who completed the terms of their sentence prior to the digitization of this

information. Recovering the paper trail is particularly difficult in these cases.

As LFOs are often the responsibility of a county, if an individual no longer lives in that

particular county, was convicted in federal court, or convicted in a different state, contacting

the relevant officials to obtain a precise tabulation of what is owed can be difficult.

Eligibility

Beyond LFOs, there are two eligibility related barriers that currently exist in the process. The

first is based on what convictions are excluded from the restoration of voting rights under

Amendment 4. The text of the Amendment kept in restrictions for those convicted of murder

and felony sex offenses. However, as was referenced in the development of the predictive

model and shown in the appendices, there are a significant number of convictions that may

fall under each. The second is the uncertainty around the completion of the terms of one’s

sentence. The current laws lay out that the completion of prison, parole, probation, and most

recently fines and fees are required before the restoration of voting rights. Yet, an individual

may be concerned whether their court mandated substance abuse counseling is included in

that.

These two informational components stand as barriers for returning citizens due to their

limited access of information, especially in the absence of nonprofit advocates or legal aid. A

demonstration of how difficult this process can be is shown below.

An initial google search of “how do I get my voting rights restored in Florida” does not reveal

any up to date information on what the process is post Amendment 4 and SB7066. As such,

we expect someone to decide to go to the Secretary of State’s website as they are responsible

for elections in Florida.

On the Secretary of State website, finding information on if one is eligible to vote is not an

easy process. On the Elections page of the website, there is no clear tab or option targeted

towards returning citizens on information related to their voting rights. If one uses the

website’s search bar and searches for phrases such as “how do I get my voting rights restored?”

“voting restored” or “disenfranchised”, no hits are found. It is only when one searches the word

“felon” that a link for a voting FAQ which contains a paragraph for those seeking to have their

rights restored (below).

29

Clicking on the first link provided simply takes you to the home page of the Florida

Department of Corrections. There is no indication on the DOC website of how to see one’s

eligibility regarding voting rights. In fact, a search in the “offender search” tab, which requires

a name and DC number, reveals only a person’s specific convictions and the release date from

prison.

The next step would be to visit the county clerk’s website, which neither provides concrete

information on one’s status. This means that one must visit the county clerk’s office, that also

could be a barrier dependent on an individual’s ability to visit the office during business hours.

As was hopefully demonstrated in this brief example, the process of determining your

eligibility can be a discouraging and seemingly insurmountable process.

Options available

The last major subcategory of informational barriers deals with an individual’s awareness of

the specific legal options in restoring their rights. This is particularly relevant regarding the

options surrounding LFOs. As previously mentioned, an individual can petition the court to

have their fines and fees waived, reduced or converted into community service. While this

option is open to all returning citizens, only four counties (Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach

and Hillsborough) have instituted a process of grouping petitioners and processing the

requests simultaneously to expedite the process. Although these counties represent around

35% of Florida’s total population, those who do not live in these counties must wait indefinitely

for their case is heard. More importantly, knowledge of this legal option is not widespread,

especially for returning citizens who may live in rural or other areas not covered by advocacy

groups.

Uncertainty created

Each of these informational hurdles increases the uncertainty around voting right

restorations. While reclaiming your voting right is a significant step in restoring an individual’s

citizenship within society the returning citizen’s efforts to have her/his rights restored are

inhibited by this uncertainty. This is exacerbated by the fact that the benefit associated with

voting is outweighed by the punishment of voting illegally, that is the impact of a single vote

is generally small however, should an individual erroneously cast a vote the punishment is

30

third-degree felony carrying a maximum sentence of 5 years.

28

In 2018, a Texas woman who

believed her rights had been restored, voted in the election and was sentenced to 5 years in

prison.

29

This imbalance is compounded by placing the responsibility to know your right to

vote on the returning citizen. Election officials will not be able to confirm eligibility at the time

of registration. As such, the uncertainty surrounding the information of one’s status and the

outsized impact of being wrong may keep many from attempting to register to vote.

Additionally, the current legal battle that is ensuing around SB 7066 has served only to

increase the uncertainty around who is eligible or not. With every ruling and appeal, Floridians

are left unsure and confused on what the state of the legislation is. The impact of this

uncertainty can have a permanent effect on an individual and is what Bruce Riley of Voice of

the Experienced, in Louisiana, describes as the power of “word on the street”. “Word on the

street actually has power. If word on the street says you don’t have the right to vote it actually

doesn’t matter if you have the right to vote or not because you are going to listen to word on

the street.”

30

Once individuals are convinced that they are not eligible to vote, it is difficult to

change their minds. This barrier highlights that regardless of the outcome of the legal battle

surrounding SB 7066, we expect that the uncertainty created by the law will have a lasting

impact.

FINANCIAL BARRIERS

Perhaps the most intuitive barrier is the financial cost due to SB 7066. As previously

mentioned, we expect the enactment of this law to result in the disenfranchisement of ~70%

of the previously enfranchised individuals. This cohort holds billions of dollars in outstanding

fines and fees. For most returning citizens this financial burden is prohibitive.

31

This barrier is

binary in nature – you’re either disenfranchised because you have LFOs or you are not. This

can only be resolved by one’s ability to pay off their fines and fees or by having them reduced

or converted into community service by the courts.

It should be noted, irrespective of SB 7066, that Florida’s LFO system has been one of the most

punitive in the nation. The current system makes no exemptions for indigent individuals and

traps them in a vicious cycle of debt to the state. For an in-depth analysis of Florida’s LFO

system, we suggest referencing the Brennan Center’s publication on the topic.

32

MOBILIZING BARRIERS

Once an individual has determined their eligibility, there are still barriers that exist in getting

out the vote. They will manifest themselves at different stages throughout the process. The

three main subcategories identified were apathy, lack of engagement, and standard turnout

issues.

Apathy

28

s. 775.082

29

Romo, Vanessa, and Sasha Ingber. “Texas Woman Sentenced To 5 Years For Illegal Voting.” NPR.

NPR, March 31, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/03/31/598458914/texas-

woman-sentenced-to-5-years-for-illegal-voting.

30

Bruce Riley, in expert interview. March 2020

31

Sweeney, Dan. “South Florida Felons Owe a Billion Dollars in Fines - and That Will Affect Their Ability

to Vote.” sun, May 31, 2019. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/politics/fl-ne-felony-fines-broward-

palm-beach-20190531-5hxf7mveyree5cjhk4xr7b73v4-story.html.

32

Diller, Rebekah. “The Hidden Costs of Florida’s Criminal Justice Fees.” Brennan Center for Justice,

2010. https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Report_The Hidden-Costs-

Florida's-Criminal-Justice-Fees.pdf.

31

A significant barrier is apathy towards the political system. Many Americans believe that

participation in the democratic process does not have an impact on governance or are

uninterested in the governance because they perceive it as hostile towards them. However, for

many returning citizens the apathy is deeper than a simple distaste for politics. Desmond

Meade, founder of FRRC and a returning citizen himself, had an acute description of the

psychological factors at play.

“There is a level of belonging that is damaged when you take someone’s right to vote away and,

in my experience, its personal and professional. When a person can’t vote that is something

painful. Whether they want to vote or not, the fact that they’re told they can’t vote is a stark

reminder that you are not a part of our society. And that’s painful. Because the human instinct,

the natural human instinct, is to be a part of this group, to be a part of something and to be

told you’re that you’re not right is something painful. So we mask that, with an indifference

we find the way to dull or nullify the pain. What comes out of this is “I don’t give a damn about

voting don’t matter who gets in office, we’re still gonna be messed up, my vote don’t count.”

33

This barrier does not have a technical solution but requires significant engagement on an

individual level to be overcome.

Lack of Engagement

Lack of engagement efforts and the nature of these efforts hinder the turnout of returning

citizens. Many returning citizens are concentrated in districts with low voting propensity. This

often leads to reduced attention by electoral engagement efforts. Additionally, with returning

citizens as a new voting population, the engagement infrastructure is often not yet in place.

The efforts around this may increase as organizations and political parties recognize the

potential impact the population can have.

The method of engagement determines its success. It is important to recognize that the

restoration of voting rights is greater than the transactional nature of turning out to the polls

and voting for a specific candidate. In conversations with advocates that are working in this

area, there was an emphasis that the restoration of voting rights was about restoring an

individual’s dignity and their status as a first-class citizen.

This sentiment was echoed with individuals who worked with voter engagement of returning

citizens from Louisiana to Alabama. Restoration of citizens’ rights and one’s dignity must be

front and center to any strategy aimed at mobilizing and organizing returning citizens. Neil

Volz, FRRC board member, explained that for their mission “it is about returning citizens lives,

it’s about getting people plugged into the community, it’s about people educated on the

issues.”

34

Any engagement and organizing effort that isn’t centered around issues of dignity and

citizenship, will not be successful.

Standard Turnout Issues

The previously mentioned barriers were all specific to returning citizens, they however also

face the same barriers as the general population. This includes a lack of transportation, voter

suppression, long voting lines, lack of early voting, and myriad of other factors. Resolving

these issues will increase the impact of both returning citizens and the general population.

33

Desmond Meade, in expert interview, January 2020.

34

Neil Volz, in expert interview, January 2020.

32

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our research shows that Amendment 4 will have a positive impact on democratic participation

in Florida by returning citizens and their communities. Below are recommendations for the

Florida legislature, the Sentencing Project, and other advocates to push that even further. We

want to caveat that our position is that there should be no limitations on an individual’s right

to vote, however, we recognize that some changes must be done incrementally to be successful

politically. As such some recommendations may not be fully in line with that ethos on

disenfranchisement but are rather pragmatic solutions.

Our recommendations are categorized in line with the barriers. There is some overlap across

categories, demonstrating the interplay between them

INFORMATIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Create a centralized informational process

As was demonstrated previously, obtaining information on one’s eligibility can be a difficult

and complicated process. This informational barrier necessitates the creation of a streamlined

process that combines the requirements of the Secretary of State, the Department of

Corrections and county clerks. Providing clear and actionable steps for returning citizens to

have their voting rights restored will decrease the concerns that are associated with the current

system.

We recommend that the State of Florida develop a centralized system with which an individual

can input their name and DC number and immediately find out what is owed and if they are

eligible. With the state potentially being hesitant to invest in such a process, this is also an

opportunity for a third party, although administration through a non-governmental

organization has obvious draw backs. Nonetheless, the data Dan Smith’s team has collected is

a fantastic starting point although it is currently being treated as proprietary information.

It is important to emphasize that the creation of a database is addressing two issues – LFOs

and conviction eligibility. These two issues have inputs from very different sources. Gaining

access and combining these inputs comes with a degree of difficulty, that must be thoughtfully

managed.

Change the burden of proof

A significant barrier preventing individuals from registering to vote is that the burden of proof

for eligibility falls on the returning citizen as Florida does not maintain a system of

determining eligibility at the point of registration. This creates huge uncertainty that will

discourage returning citizens.

We recommend that the burden of proof should be changed from the returning citizen to the

state. Registration to vote may only be successfully completed should the individual legally

qualify, thus protecting the returning citizen from prosecution if it is later determined they

were not eligible. It would be the fault of the system not the individual.

Change language in registration process

When an individual decides to register to vote, whether online or with a physical form, they

are met with the following language:

33

“If I have been convicted of a felony, I affirm my voting rights have been restored pursuant to

s. 4 , Art. VI of the State Constitution upon the completion of all terms of my sentence,

including parole or probation.”

We recommend that the Secretary of State changes the language of the registration form from

“including parole or probation” to “including parole, probation, and the payment of fines and

fees.” This change is necessary for individuals who might not be aware of the details postulated

in SB 7066. It is possible for a returning citizen to be aware of the passage of Amendment 4

granting them their voting rights and when they go online to register see only the mention of

parole or probation. This would suggest to them that they are eligible, despite the possibility

that they still owe fines and fees. Changing the language is a simple way to ensure that

returning citizens are not registering despite being ineligible.

Provide information at last official contact with the system

Access to information has been shown to be a difficult process for many returning citizens.

Since some individuals might not be aware of the options available to them or the restrictions

they are under, it is important that this information is provided in an accessible method. We

recommend that returning citizens are provided an information packet regarding their voting

rights at their last official contact with the criminal justice system. Whether this is released

from prison or the last meeting with a parole or probation officer, an individual should be

provided with relevant information on how they can get their rights restored.

34

FINANCIAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Repeal SB 7066